1 Volumes

Revolution in New Jersey

Early, brief but significant.

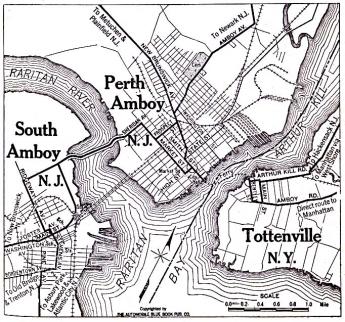

British Headquarters: Perth Amboy, New Jersey, in its 1776 Heyday (B 608)

Not many now think of the town of Perth Amboy as part of Philadelphia's history or culture, but it certainly was so in colonial times. Sadly, the town has since declined to a condition of a quiet middle-class suburb. There are quite a few Spanish-language signs around and some decaying factories. The little house of the Proprietors on the town square and the remains of the Governor's mansion overlooking the ocean are about all that remain of the early Quaker era.

|

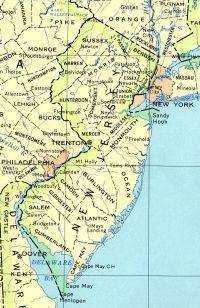

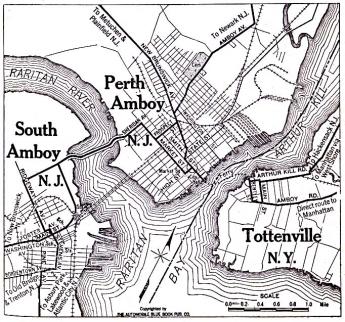

| NJ MAP |

To understand the strategic importance of Perth Amboy to Colonial America, remember that James, Duke of York (eventually to become King James the Second) thought of New Jersey as the land between them North (Hudson) River, and the South (Delaware) River. This region has a narrow pinched waist in the middle. It's easy to see why the land-speculating Seventeenth Century regarded the bridging strip across the New Jersey "narrows" as a likely future site of important political and commercial development. The two large and dissimilar land masses which adjoin this strip -- sandy South Jersey, and mountainous North Jersey -- was sparsely inhabited and largely ignored in colonial times. The British in 1776 developed the quite sensible plan that subduing this fertile New Jersey strip would simultaneously enable the conquest of both New York and Philadelphia at the two ends of it. It was a clever plan; it might have subjugated three colonies at once.

|

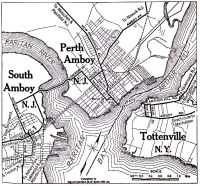

| PERTH AMBOY MAP |

Perth Amboy is a composite name, adding a local Indian word to a Scottish one because East Jersey had been intended for Scottish Quakers. Like Pittsburgh at the conjunction of three rivers, Perth Amboy's geographical importance was that it dominated the mouth of Raritan Bay (Raritan River, extended) as it emptied into New York Bay just inside Sandy Hook. Two of the three "rivers" of the three-way fork are really just channels around Staten Island. Viewed from the sea, Perth Amboy sits on a bluff, commanding that junction. Amboy became the original ocean port in the area, although it was soon overtaken by New Brunswick further inland when increasing commerce required safer harbors. Perth Amboy was the capital of East Jersey, and then the first capital of all New Jersey after East and West were joined in 1704 by Queen Anne. The Royal Governor's mansion stood here, as well as grand houses of Proprietors and Judges overlooking the banks of the bay. The main reason for the Nineteenth-century decline of the state capital region was the narrowness of the New Jersey waist at that point; its main geographical advantage became a curse. Canals, railroads and astounding highway growth simply crowded the Amboy promontory into an unsupportable state of isolation. The same thing can be said of Bristol, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware, but local civic pride has somehow not risen to the challenge to the same degree.

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

Jersey

|

| Map of New Jersey |

Once you notice the oddity of salt water in the lower reaches of the Delaware and Hudson rivers, it gets easier to understand the current theory that southern New Jersey was once an island. Like Long Island, it was separated from the mainland by a sound, but in the Jersey case the sound silted up from Trenton to New Brunswick, creating a new peninsula of "West" Jersey by uniting the island with the mainland. The colony was named after the island of Jersey off the coast of England, a gesture for Sir George Carteret, who was given the American area out of gratitude for once sheltering the exiled royal brothers Charles II and James from Cromwell, in that other Jersey. Cape May was probably a second distinct island later joined to the larger one by the transformation of the silted ocean into the bogs of the Maurice River. Cape May started as a whaling community, populated by Quakers from New York and New England, who always maintained a social distance from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. The long Atlantic beaches of New Jersey now repeat the main geological process, with successive generations of barrier islands first heaved up by the ocean and then packed against the mainland, filling up the brackish bay. The cycle of forming and packing successive barrier islands takes about three hundred years before a new one starts. In a larger sense, the process consists of the former mountains of Pennsylvania crumbling into the ocean and then responding to wave action.

It's no mystery, therefore, why southern New Jersey is flat, broken up by turgid meandering streams which casually empty in either direction. The head of Timber Creek, which flows into Delaware, is only eight miles from the head of the Mullica River, flowing toward the ocean. During the Revolutionary War, the British found it too dangerous to sail up these winding creeks, since at any moment they might make a sharp turn and be facing a battery of cannon on the shore. An arrangement quickly grew up that buccaneers would build ships in the center of heavy oak forests and sail them out to Barnegat Bay, thence out one of the inlets of the barrier islands into the blue water. The financiers of Philadelphia, many of them with names now in the Social Register, would come from the rear, sailing up the Delaware River creeks, and walking the last mile or two to privateer headquarters on the Atlantic-flowing creeks. Auctions were conducted, in which the ships were examined, the captain interviewed, and the crew observed in target practice. If you bought a small share you would be rich when the ship returned; and if it never returned, well, you had to invest in a different one. New Jersey is indignant of the opinion that these privateers were mainly responsible for winning the Revolution, but given little credit for it. Many more British sailors were lost to the privateers than soldiers were lost to Washington's troops and the economic loss to Great Britain of the ships and cargoes eventually became serious. Since much of the profit from privateering was recycled into the American war effort by Robert Morris, the British found themselves facing an enemy much more formidable than just the ragged frozen troops at Valley Forge on the Schuylkill. Meanwhile, William Bingham was conducting a similar privateering operation in partnership with Morris but based on the island of Martinique, but that's another story.

In later centuries, the traditions and geography of the Jersey Pine Barrens suited themselves to smuggling and bootlegging during the era of alcohol Prohibition, and even after Repeal, high taxes on liquor kept bootlegging profitable. As late as the 1950s, there were divisions of FBI men prowling the woods of South Jersey, on the lookout for trucks carrying bags of cane sugar, or coils of copper tubing. After housing developments started to invade the forests, the hardball politics of South Jersey reflected a Mafia culture thought more characteristic of South Philadelphia. Near Vineland and Atlantic City, it isn't just a culture, it has the accent, because it also has some of the ancestry.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey, A Historical Account of Place names in the United States: Richard P. McCormick: ISBN-13: 978-0813506623 | Amazon |

Easy Ride: Perth Amboy to Trenton

The Revolutionary War had been raging for a year in New England before the Declaration of Independence, a point that never ceased to bother John Adams whenever Thomas Jefferson or his devotees took credit for starting the Revolution with a piece of paper nailed to a lamp post a year after Lexington and Concord. This interval nevertheless allowed for the organization of the Continental Army, and Washington's maturing military background by the summer of '76. It also allows the time for the surprisingly immediate landing of Sir William Howe's army on Staten Island at the end of June 1776. A month or so after that, his brother Admiral Howe landed more troops. By September 1776, not all of the signers had yet put their names to the Declaration of Independence, but there were about 40,000 British troops parading around the essentially uninhabited Staten Island in New York harbor, in plain sight of the inhabitants of New Jersey's capital in Perth Amboy, and scarcely a hundred miles from Philadelphia. Massachusetts and other New England Patriots have a point when they claim the Declaration of Independence marked the end of the first year of rebellion against British rule, while the other colonies prefer to say July 4, 1776, was the beginning of the war for independence. It was an irrevocable gesture of unified defiance, a copy of which was sent to the personal attention of George III.

The British shrewdly selected New York harbor as the center of their operation, since their Navy was thereby in position to shift quickly in the protected waters of Long Island Sound from New Jersey to Rhode Island, or up and down the Hudson as far as Albany, meanwhile dominating the considerable expanse of Long Island, not to mention Manhattan. It was only eighty miles travel across the narrow waist of New Jersey to the top of Delaware Bay at Trenton, potentially also leading to control of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, land-locked Washington was faced with crossing numerous rivers to defend hundreds of miles of shoreline, moving foot soldiers to defensive positions. He tried to defend New York, it is true, but the battles on Brooklyn Heights, Harlem, Fort Washington and Fort Lee were essentially unwinnable, and the best he could really do with the situation was escape with an undestroyed army. Being farther from the reach of the British Navy, Philadelphia was more defensible than New York, and besides, it was now the capital of the rebellion.

|

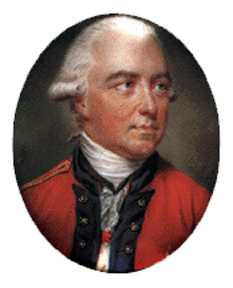

| Cornwallis |

By the fall of 1776 Howe had consolidated his hold on New York, and Washington was reduced to scattering small clusters of troops around the places Howe might likely invade. Those clusters were reassuring to their neighbors and easy to provision locally, but equally easy for the British to overwhelm. Washington was a better general than it seemed; these several bands of about 500 militia were expected to remain in readiness to be summoned as soon as the main British force committed itself to a major objective. In early December, the British started landing in New Jersey and marched toward New Brunswick. Washington thought that meant he was going to head for Trenton, and then down Delaware to Philadelphia. There was not much to stop him except skirmishers and Minute Men, but it was unsafe for Washington to move his troops from the New York region until the intentions of the swifter British were really clear. By that time it might be too late to stop an advance, but it couldn't be helped. Washington was inventing guerrilla warfare, patterned after his observations of the style of Indian fighting, and his observations during the French and Indian War, of the weaknesses of the British style.

Since the Raritan Strip along which Howe and Cornwallis eventually chose to advance, was prosperous and Tory, things went pretty well for the British. After two weeks march, they arrived in Trenton around December 20. In this triumph, the British failed to appreciate the significance of several things, however. Washington was hurriedly summoning six little colonial armies of five hundred to a thousand men each, to join him now that the intentions of the enemy were clear. Furthermore, the Whigs or rebels of New Jersey were aroused in the Pine Barrens of the South and the hills of the North; New Jersey was not nearly as Tory as it seemed during the initial march past the big houses along the Raritan. And, finally, the British and Hessian mercenary soldiers had indeed ravaged the countryside almost as much as the spinsters of the Whig patriot cause shouted out they had. Many neutrals were converted to rebels. The Quaker farmers were particularly upset by the activities of the camp followers, who pillaged curtains and other things not normally attractive to marauding soldiers. And the sharpshooters, both loyalist, and rebel were close enough to their own homes to dispose of another booty. It was a cakewalk down to Trenton, but it was not going to be the same coming back.

|

| Washington |

Washington was getting ready to defend the Capital in Philadelphia, and the wide Delaware river was the best place to do it. When Howe and Cornwallis reached Trenton, they found no boats available on the New Jersey side for miles up and down the river, artillery was planted in strategic places on the Pennsylvania side, ice was beginning to form on the river, it was cold, the December days were short. To them, Washington posed no particular military problem with his naked ragamuffins. Howe had some lady friends in New York, while Cornwallis was planning to spend a month in London before the spring military season. So the British generals made an overconfident miscalculation, and posted their troops in winter quarters, strung out in outposts from Perth Amboy to Trenton and down to Bordentown. A thousand Hessians were quartered in Trenton. By December 20th, it looked like a peaceful but boring Winter lay ahead.

REFERENCES

| Stories of New Jersey: Frank R. Stockton: ISBN-13: 978-0813503691 | Amazon |

Disorderly Retreat: From Trenton Back to Perth Amboy

|

| George Washington on a Horse |

A week later, they got a bad jolt; Washington declined to play by their winter rules. At the Battle of Trenton, Washington was 44 years old, six feet four inches tall or more, a horseman and athlete of outstanding skill, and as the husband of the richest woman in Virginia, accustomed to housing, feeding, transporting and getting cooperation from two hundred slaves. All of those qualities may have been of some use in the battle. But after the Battle of Trenton, Washington also emerged as a remarkably bold and creative General. In the Battle of Trenton ca-----------------999999 seen the elements of audacity, timing and courage that were notable in Stonewall Jackson, George Patton -- Virginians, both -- the Normandy Invasion, and the Inchon Landing. He forged, if he did not create, the American military tradition of inspired risk-taking. And he did it with a collection of starving amateurs, up against the best Army in the world at the time. Probably without realizing it, his coming victory at Trenton also gave Benjamin Franklin in Paris a major enticement for the French King to support the American cause. Washington produced a significant achievement, but just to make sure, Franklin exaggerated it just as much as he could.

On December 21, Washington thought Howe was immediately going to sweep on through Trenton to Philadelphia. In a day or two, he saw that wasn't the plan, organized the famous re-crossing of Delaware in bad weather, and caught and captured a thousand Hessians with a three-pronged attack which cut off their retreat and made resistance useless. The main military feature of this attack was not Christmas drunkenness among the Hessians, but the fact that General Knox had somehow transported eighteen cannon to the occasion. Nowadays, the event is marked by a reenactment on Christmas Morning, although it took place on December 26, 1776. The timing did not have to do with religious observance, it had to do with hangovers. To the great disappointment of his troops, he made them abandon the great stores of booze in Trenton because a second detachment of Hessians was in nearby Bordentown, and meanwhile, he retreated back to the Pennsylvania side of the river. As might be imagined, Howe's Cornwallis promptly came charging down from New Brunswick to exact bitter vengeance. Instead of trying to rescue their comrades in Princeton, the Bordentown Hessians took off for New Brunswick. Defiantly, Washington taunted his enemies by again recrossing Delaware to the New Jersey side, put up fortifications, just waited for them to make something of it.

Well, that's the way it was meant to seem. On the night of January 2, the two armies were facing each other with about five thousand men on both sides, but with the British much better trained and equipped. The Americans had the advantage of not being exhausted by a fifty mile forced march, except for about a thousand who had been deployed forward to skirmish and delay the British advance with sniping from the bushes. The Americans made a great deal of noise and lit many bonfires behind their fortifications. But when they advanced the next morning, the British found out where the Americans really were -- by hearing distant cannon fire coming from Princeton, ten miles back toward the north.

Washington had slipped five thousand men wide around the enemy flank during the night and had taken a parallel country road to Princeton where he defeated a rear guard of British at the Battle of Princeton. An infuriated Cornwallis wheeled his army around in pursuit, and the race was on for the supplies left undefended in New Brunswick. Washington might have been able to get there first, except his men were too exhausted, and he was afraid to risk his long-run strategy, which was to avoid head-on collisions with the main British Army.

So Washington went into winter quarters in Morristown still further to the north, and thousands of British soldiers were thus bottled up in winter quarters in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick, where scurvy, lack of firewood and smallpox gave them a few months to consider their miscalculations. But the most important action of all was getting the news to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, to tell the French king of the victory. Franklin even dressed it up a little.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey in the American Revolution: Barbara J. Mitnick: ISBN-13: 978-0813540955 | Amazon |

Using the Delaware River as a Weapon

|

| George Washington on a Horse |

After the Battle of Trenton, Washington emerged as a remarkably bold and creative General. In this battle of maneuver can be seen the elements of audacity, timing and courage that were notable in Stonewall Jackson, George Patton -- Virginians, both -- the Normandy Invasion, and the Inchon Landing. He forged, if he did not create, the American military tradition of inspired risk-taking. And he did it with a collection of starving amateurs, up against the best Army in the world at the time. Probably without realizing it, his coming victory at Trenton also gave Benjamin Franklin in Paris a major enticement to the French King to support the American cause. Washington produced a significant achievement, but just to make sure, Franklin exaggerated it just as much as he could.

On December 21, Washington thought Howe was immediately going to sweep on through Trenton to Philadelphia. In a day or two, he saw that wasn't the plan, organized the famous re-crossing of Delaware in horrible weather, and caught and captured a thousand Hessians with a three-pronged attack which cut off their retreat and made resistance useless. Nowadays, the event is marked by a reenactment on Christmas Morning, although it took place on December 26, 1776. The timing did not have to do with religious observance, it had to do with hangovers. To the great disappointment of his troops, he made them abandon the great stores of booze in Trenton because a second detachment of Hessians was in nearby Bordentown, and retreated back to the Pennsylvania side of the river. As you might imagine, Howe's Cornwallis promptly came charging down from New Brunswick to exact bitter vengeance. Instead of trying to rescue their comrades in Princeton, the Bordentown Hessians took off for New Brunswick. Defiantly, Washington taunted his enemies by again recrossing Delaware to the New Jersey side, putting up fortifications, just waiting for them to make something of it.

Well, that's the way it was meant to seem. On the night of January 2, the two armies were facing each other with about five thousand men on both sides, but with the British much better trained and equipped. The Americans had the advantage of not being exhausted by a fifty mile forced march, except for about a thousand who had been deployed forward to skirmish and delay the British advance with sniping from the bushes. The Americans made a great deal of noise and had many bonfires behind their fortifications. But when they advanced the next morning, the British found out where the Americans really were by hearing distant cannon fire coming from Princeton, ten miles away.

Washington had slipped five thousand men wide around the enemy flank during the night and had taken a parallel country road to Princeton where a major detachment of British was then defeated at the Battle of Princeton. An infuriated Cornwallis wheeled his army around in pursuit, and the race was on for the supplies left undefended in New Brunswick. Washington might have been able to get there first, except his men were too exhausted, and he was afraid to risk his long-run strategy, which was to avoid head-on collisions with the main British Army.

So Washington went into winter quarters in nearby Morristown, and thousands of British soldiers were thus bottled up in winter quarters in Perth Amboy and New Brunswick, where scurvy, lack of firewood and smallpox gave them a few months to consider their miscalculations. But the most important action of all was getting the news to Benjamin Franklin in Paris, to tell the French king of the victory. Franklin even dressed it up a little.

.

Howe's Choice: To Philadelphia, or Saratoga?

|

| General Howe |

Nations at war traditionally vilify the leader of the enemy, and so Sir William Howe has usually been portrayed as a lazy, illegitimate uncle of the King, a womanizer lacking in military savvy, and a former parliamentary member of the minority party supporting peace with the colonies. But to go on this way is quite unfair to Washington, who outfoxed and out-generaled a tough and very clever soldier who was by no means a pushover, and who fought hard to win.

|

| Winter 1777 |

In retrospect, it can be seen that Howe's army was crammed into winter quarters on the Perth Amboy-New Brunswick bluff across the river from Staten Island in the winter of 1777, following the defeat at Trenton. Washington's troops were meanwhile in a fairly impregnable position around Morristown. If Howe went back along the Raritan toward Trenton and Philadelphia, he could expect to be butchered by snipers behind trees. If he embarked on his ships, he would be vulnerable during the two days of so required to break camp and load the ships. Washington's problem was actually just as bad. He had no way of knowing whether he had to defend against an encircling movement at Morristown, against a renewed invasion toward Trenton and Philadelphia, or against a quick movement at sea by the battleships. If Howe embarked, he might be going to Albany to rescue Burgoyne, or to Fort Lee to encircle Morristown, or to Philadelphia, or even to Charlestown. Anyone of these choices would mean that Washington would have to hurry overland to catch him.

It now seems clear that Howe had decided it was safe to abandon Burgoyne. He might have tried to capture Philadelphia and get back to Albany by September, but evidently, this seemed too ambitious and fraught with unexpected accidents, as events later proved to be true. Clear and unambiguous orders by Lord Germain in London were mislaid and never reached him. By implication, he was being told to use his best judgment. So he decided on a double option. He would send sorties out in all directions to keep Washington guessing and to entice him to come down from his mountain fastness into a pitched battle with British regulars. Failing that, he would get on his ships and take Philadelphia. Furthermore, Howe never told another soul what his plans were, except by sending a spy with misleading plans sewed into his coat, intending for him to be captured by the rebels. Washington, however, essentially refused to budge.

Finally, Howe ordered an embarkation onto his ships, and actually loaded a contingent of Hessians on board. Although Washington was mistrustful of a trick, his officers persuaded him to attack the "vulnerable" British while they were loading onto the transports. As soon as Howe heard of Washington's movement he immediately issued orders to turn the whole army around and trap Washington. He thought he now had his chance to catch and destroy the Continental army.

As things turned out, it didn't work and Washington escaped with most of his troops. Fearful of another such trap, he then held back perhaps too long and helplessly watched the ships load, weigh anchor, and sail out to sea. Where were they going? Not another person on the British (or Loyalist) side knew the answer, and the ships were far out to sea, invisible before they turned in whatever direction they were going. Was it North, or South?

A week later, word came to Washington that the fleet had been sighted off the mouth of Delaware. It was time to move South, in a big hurry, on foot. Howe was going to go to Norfolk, but it wasn't even certain whether he was coming back up the Chesapeake, or going still further South to Charleston. It remained conceivable that he would wait for Washington to move his troops South, then double back to New York and Albany to Join Burgoyne.

As we now know, Howe did turn up the Chesapeake to land in the rear of Philadelphia. And then Washington also guessed right and lined up his troops at Chadds Ford of the Brandywine Creek. Both of them were shrewd and very quick. Howe had won a major victory with superior resources. But as we shall see, Washington wasn't through with him.

REFERENCES

| The Uncertain Revolution: Washington and the Continental Army at Morristown: John T. Cunningham: ISBN-13: 978-1593220280 | Amazon |

Christmas, 1776, Behind the Scenes at Trenton

|

| Washington Crossing Delaware |

Cornwallis and the British regulars came thundering down the narrow waist of New Jersey from New Brunswick to Trenton, just before Christmas, 1776. Washington's troops retreated before them, fleeing to the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. The British then fortified the Hessians in Trenton and went back into their own winter quarters nearer New York. Plenty of time seemed available to finish off Washington in the Spring, and then leisurely conquer the enemy's capital in Philadelphia. The Continental Congress thought so, too, and moved its capital to Baltimore. Only three members of the Congress, Robert Morris, George Clymer, and George Walton (of Georgia), remained in Philadelphia to run the government; Morris was essentially in charge, in the role of financier whatever that meant. With Congress seeking refuge, Morris was for practical purposes, acting President of the United States. Washington swept up all of the boats on Delaware, set up camp on the Pennsylvania side, and begged Morris to get him some money to reward re-enlistments by January 1. Others saw the end of the year as Christmas time; Washington saw it as the end of the year when enlistments expired. He quite plainly stated that it was all over for the Continental Army unless he could get some hard currency, silver preferred, to show the troops that the rebellion could survive another year. About ten dollars per soldier would probably do it, but then there was also a need for hard money to buy food and supplies for the starving troops.

|

| General Charles Cornwallis |

Just how Morris managed to find the money is unclear, or how much of it was his own. But he did manage, with the lucky arrival of a gunpowder smuggling ship from France, and eighteen cannon somehow supplied by General Knox. The Colonials rallied to re-cross Delaware, surprise the Hessians, outmaneuver Cornwallis as he once more thundered back down the New Jersey waist, now intent to wreak vengeance. The military essence of it all reached a climactic moment when Washington used fake bonfires to trick the British while he sneaked around them. Captain Sam Morris and Philadelphia's First City Troop managed the bonfire deception. When cannon fire in Princeton announced the trick, the British raced back to their ships at Staten Island to protect their supplies before Washington who now had a head start, could get to the ships, leaving the British to starve in the woods. Both sides were exhausted by the chase, and although he had won this race, Washington had to retreat to winter quarters in Morristown, New Jersey (named after a former New Jersey Governor.) Meanwhile, with Congress taking refuge in Baltimore, Philadelphia was nearly deserted except for some Quakers who felt they had no quarrel with the British. And Robert Morris, who continued to run his smuggling operation with Beaumarchais the famous playwright on the French end of it. Tradition has it that some Quaker gardens were dug up to find enough silver to reward reenlistments, and if so it is unclear how much was freely contributed and how much was just plain stolen; indeed, how much of it might have been Morris' own money. By the next fall, Washington was able to fight the largest battle of the war at the Brandywine Creek, so Morris must have been very active smuggling guns and gunpowder to resupply the Colonials during that intervening winter and spring.

During periods of the lull in infantry warfare, other warfare including privateering at sea, blockades, and the diplomatic intrigue in Paris, were unmerciful. If Washington's army had been wiped out, the Revolution would have ended. But other misadventures might have ended it as well. The colonists were demoralized, and their dismay was summarized by a letter from Morris to Silas Deane, a line of which was the bitter observation that "Sorry I am to say it, many of those who were foremost in noise, shrink coward-like from the danger.".

A few days before that fateful Christmas, Ben Franklin had arrived in Paris to take over our diplomatic mission with the French. When the news of Washington's victory reached him, the new American arrival was being acclaimed as the world-famous scientist and witty author and was thus in a position to make the most of it with the French court. He may be forgiven for exaggerating Washington's exploits a little. The Trenton victory was rough and ragged, but it would serve. Washington, Franklin, and Morris. The three Americans who mainly won the Revolutionary War for us now took the stage, front and center.

Those Troublesome Lees of Virginia

|

| Richard Henry Lee |

SOMETHING useful can, of course, be learned from a man's friends, but descriptions given by his enemies are usually briefer. The Lee family of Westmoreland County Virginia were bitter enemies of Robert Morris the Financier of the Revolution, and they surely said some unfair things about him. Morris paid as little attention to the Lees as possible, but for generations, the Lees had been neighbors of the Washingtons, and so could not be completely brushed aside. Furthermore, they were close to the center of Thomas Jefferson's anti-Federalist party. So insights into the Lee family probably illuminate the main disputes before, during, and after the Revolution. They even illuminate the mixed character of George Washington, who was sometimes unusual by Virginia standards. Nevertheless, the Lees had the same quality of heedless idealism to be found in Samuel Adams of Massachusetts and Patrick Henry of Virginia which goes beyond the ability of two-feet-on-the-ground revolutionaries like Robert Morris and Benjamin Franklin to understand, or even abide; this conflict runs throughout the history of the American founding. It seemed to baffle even those who switched positions, like James Madison going in a leftish direction, and Thomas Paine, going toward the right. So, although reckless idealism cannot be an inborn character, it must quickly acquire very deep roots.

.jpg)

|

| Arthur Lee |

Arthur Lee and his brothers William and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, were passionate rebels of the Patrick Henry ("Give me liberty or give me death") sort, intermittently reviving lifelong attacks on Robert Morris. Highborn Tidewater aristocrats, they were ancestors of Virginia's revered General Robert E. Lee. Arthur had even attended Eton College and later studied medicine in England. The Lee brothers started attacking Robert Morris well before his famous abstention from the critical 1776 vote on independence. It's much too easy to shrug the Lees off as landed aristocrats who disdained self-made men, or as passionate Jacobins who hated self-made rich people, or maybe just narrow-minded nuts. Out of their often inaccurate attacks emerges an outline of what a lot of other people thought about Robert Morris. Many of these polar mind-sets outline the main divisions of political strife in America right up to the present. For present purposes, let's try to understand why Morris might risk his substantial fortune in underground smuggling before the war, and then dedicate his huge energies to winning the war -- while at the same time, not only refuse to agree to the Declaration of Independence (he did finally sign it in August 1776), but speak out in public opposition to independence. What explains Morris' apparent double-talk?

<The explanation I choose to accept is that Robert Morris' real feelings were too sophisticated for this particular crisis, reaching clearer expression in his later activities promoting the Articles of Confederation and its revision the United States Constitution. A man given to terse one-liners, Morris said in December 1775 that he joined his fellow Americans in striving for "Constitutional Liberty" but could not join them in promoting independence.

Morris was never explicit about what would achieve Liberty without Independence; perhaps something like the independent Irish parliament which English Whigs then supported, or the Scottish local parliament which exists today, was in his mind. Both of them link a single King to a commonwealth. At the time, no one was interested in the political philosophy of a shipping merchant.

But today we are in a position to see no member nation of the British Commonwealth has a written constitution; written constitutions are a comparatively recent innovation and not necessarily an essential one. The American Constitution today continues to argue about original intent and living documents, so it is still possible to prefer the wisdom of a benign King to written constitutions. The British goal seems to be to infuse overarching principles of government so deeply into citizen minds that such principles overwhelm any written commandments, however vague all that may sound to outsiders who prefer to niggle over documents. Not in America, of course, because an immigrant nation like ours cannot grow cultural roots sufficiently deep in a few generations, and must have written rules. Great Britain's recent difficulties with immigrants from the Commonwealth may well reassert the limits of unwritten constitutions; constant questioning of the written American constitution by more recent immigrant groups may become a part of the British life, too.

The Articles of Confederation were written by the eminent lawyer John Dickinson, said to be the man closest to sharing Robert Morris' political philosophy. However, for five years the Articles were unratified, and Morris began to believe this lack of ratification was the reason the states were so resistant to taxation. So Dickinson gets credit for writing the Articles, but Morris must be seen as their father. Believing the lack of federal taxation was the main difficulty, and blaming the unratified Articles as the reason for it, our businessman man-of-action pushed them through. Unfortunately, with the Articles it didn't work because the taxation problem still remained, so Morris turned his immense energies toward replacing the Articles with something which would work. It does not twist American history a great deal to believe that Robert Morris, Jr. was one of the main driving forces behind both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution of the United States. He was neither a lawyer nor a political scientist and therefore was quite indifferent to who got credit for the documents. As Ronald Reagan was to discover two centuries later, that's one of the best ways to get anything done.

Morris could read; he knew the Articles didn't endorse Federal taxation. But he was apparently convinced an unwritten constitution always contains the latitude to do what simply has to be done; anything else amounts to shooting yourself in the foot. After the Battle of Trenton, when Morris became President of the United States for three months in everything except name, he still blamed his troubles on the inability to levy taxes, which in turn was due to failure of the states to ratify those Articles. So sensible a man as John Dickinson would never assume overly strict interpretation was intended; obviously, a state must confiscate private property when otherwise it cannot survive. After five years of state inaction, Morris abruptly pushed the Articles through to ratification. But he was wrong, it didn't help. When he finally grasped that the explicit limitations on taxation were intentional, intended to override any implicit power in the Articles whatever, he promptly threw his weight behind John Jay, George Washington, and James Madison to support a new Constitutional Convention setting it right, especially the national government's ability to levy taxes. Since Washington had by then become his best friend, who actually lived next door in Morris' Market Street house for years, there is not much paper trail of this interaction between these old friends. Once he got his tax mandate at the Convention, however, Morris had hardly anything further to say. His frenetic later activity immediately after the Constitution was enacted can almost surely be attributed to lifelong habits of a negotiator, avoiding mention of anything which might distract from his main goal, in this case of ratifying the Congressional right to levy federal taxes, but not abandoning subordinate goals for a moment. What the Lees hated about Morris, therefore, cannot be easily explained, but certainly, one feature of it was his ability to hold his cards face-down. The Lees didn't hold their cards, they flourished them. In their eyes, no gentleman would do anything else.

The incidents of June 1776 place the Lees in a more favorable light if they are seen as urging instinctive decisions by popular mandate, essentially favoring an unwritten British Constitutional arrangement. The Lees believed the place of a gentleman was at the head of a troop, daring the rest to follow their lead. The British had blockaded Boston, passed the Prohibitory Acts, fought naval battles in the Delaware River in May of that year. A huge British fleet had landed in New York harbor, and the agitated colonists were about to declare war. At the very moment of crisis, that rich Philadelphia merchant had refused to vote for independence. The Virginia tobacco planters were dancing a war dance in a city known for its pacifist Quakers, while their neighbor George Washington was conducting an actual war with the British. It was then revealed that Robert Morris had been participating in a gunpowder smuggling operation known as the Secret Committee, and Morris had made considerable profits from it. While many of his friends defended Morris, it was pretty easy to go wild with indignation about trusting him to sit on a secret espionage committee, unwatched. The very least that could be done was to appoint Arthur Lee, already a member of the Continental Congress, to that Secret Committee to sound the alarm if anything looked funny. The ironic fact seems to be that Morris and the Lees were passionately committed to the same unwritten approach to government, primarily based on trust in personal character, otherwise defined as fidelity to an unwritten tribal code. If you are the right sort of person, you will be with us; if you are not with us, you must not be the right sort of person. Unfortunately, a nation of immigrants may not survive if it adopts too many such notions.

The Lees had expressed disruptive views of Morris in the past, but they were exactly the sort of clan likely to confront scoundrels whenever facts called for it, and sometimes even when they didn't. The underlying conflicts, fiercely advocating both a strong centralized government and a loose decentralized one but not defining either, continue to run through American politics until the present. Whether Morris ever acknowledged it or not, he ended up on the side of defined contracts, as opposed to a Code of Honor. But he spent his life as a man of his word because in business your word is your bond; if you are any good, you won't need to cheat. If our Tower of Compromises is to endure, its limits of such agreement must be few, but they must somehow be strictly understood.

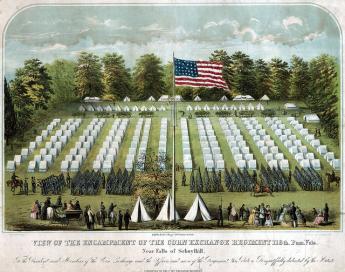

Encampment At East Falls

The urban intersection at Queen Lane and Fox Avenue in East Falls is a busy one, and except for a few stately residences, it easily escapes notice by commuters. However, the landscape forms a bowl atop a steep hill, fairly near the Schuylkill River. George Washington had evidently picked it out as a strong military position near the Capital at Philadelphia, either to defend the city or from which to attack it, as circumstances might dictate.

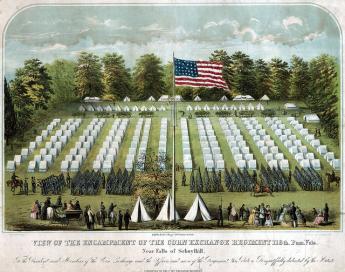

|

| Encampment at East Falls |

Washington's plans and thought processes are not precisely recorded, but when Lord Howe had sailed south from the Staten Island- New Brunswick area, he ordered his troops to head for an East Falls encampment at the southern edge of Germantown. Crossing the Delaware River at Coryell's Ferry (New Hope), the troops marched inland a few miles and then down the Old York Road to this encampment. Their stay at the beginning of August 1777 was quite brief because Washington changed his mind. When it took Howe's fleet longer than expected to appear in the Chesapeake, Washington became uneasy that Howe might be conducting a feint designed to draw the Continental troops south, and after cruising around the coast, might still return to attack down the undefended New Jersey corridor from Perth Amboy to Trenton. That proved wrong, but in Washington's defense, it must be said it was a plan that had actually been considered by the British. Anyway, Washington ordered his troops to pull out of the East Falls encampment and march back up Old York Road to Coryell's Crossing, which would be a more central place to keep his options open for the time when Howe's true intentions became clear. Washington and his headquarters staff went on ahead of the main body of troops, setting up headquarters at John Moland's House a little beyond Hatboro and a few miles west of Newtown, Buck's County. The Hatboro area was a pocket of Scotch-Irish settlement, without any local Tory sentiment, thus preferable to the rest of largely Quaker Buck's County.

To jump ahead chronologically, the East Falls encampment site must have seemed agreeable to the Continental Army, because a few weeks later it would be sought out as the main refuge and regrouping area, following the defeat at the Battle of Brandywine. The American troops were to withdraw from the Brandywine Creek when Washington realized he had been out-flanked, and head for Chester. Quickly recognizing that Chester was vulnerable, they headed for East Falls. Not only was Washington preparing to defend Philadelphia at that point, but was using the Schuylkill River as a defense barrier. As he had earlier done at the Battle of Trenton, he ordered all boats removed from the riverbanks, and artillery placed at any likely fording places, all the way up the Schuylkill to Norristown. Having accomplished that, this extraordinary guerrilla fighter then moved his troops from Germantown up the river to defend the fords. Meanwhile, Congress decided to move to the town of York on the Susquehanna, just in case.

Defeat and Disaster: Philadelphia Falls to the Enemy

|

| Howe |

Helen of Troy had launched a thousand ships. Lord Howe only launched four hundred and thirty, but they were bigger. It is estimated a thousand oak trees were cut down to build just one man o' war. To repeat what happened next, this flotilla was parked in lower New York harbor while forty thousand redcoats conquered Brooklyn Heights, Manhattan, Washington Heights, Perth Amboy, New Brunswick, Princeton, Trenton -- and then Washington promptly made fools of Howe and Cornwallis, at Trenton, Princeton, New Brunswick. Howe, and Cornwallis, in particular, were raging mad. The first year of the two-year siege of Philadelphia was over, and at half-time, the British team was popped up.

|

| Lord George Germaine |

The grand plan laid out in London by Lord Germaine was for Howe to capture New York, and maybe Philadelphia if it would be useful, while Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne took an army from Canada along that giant cleft in the earth which starts at the St. Lawrence River, down Lake Champlain, then down the Hudson from Albany to New York. The Hudson is very wide, and the British Navy would have no trouble sailing upriver to Albany, landing an army to meet Burgoyne coming south, with the effect of cutting New England off from the rest of the Colonies. Burgoyne got his orders in London shortly after Howe's January disaster in Trenton arrived in Quebec in May and started on his campaign June 20. Nothing dilatory about him. Howe, however, had six months to get to Albany before that, and several months more before Burgoyne would get to Saratoga, tromping through the woods and black flies. From Staten Island, it might have taken Howe ten days to sail to Albany in plenty of time.

|

| Chesapeake Bay |

Instead of that, Howe solitary and without advice, decided to take Philadelphia. Although the British never dwelt much on the fine points, the actual rebellion was only taking place in New England at the time the fleet set sail. It was the arrival of the fleet which triggered the Declaration of Independence, not the other way around. Lord Howe therefore probably felt some justification in revising the agreed plans and orders under which he set sail. As has been described already, the initial foray to Trenton ended embarrassingly. So, the capture of the enemy capital would now help people forget Princeton, and it would be sweet to whip Washington.

Unfortunately, they wasted a lot of time doing it. Finding Delaware too well fortified, and almost as snaggy as Henry Hudson had found it more than a century earlier, he sailed all the way to Norfolk, came up the Chesapeake and landed at the head of Elk, and marched for Philadelphia. The Brandywine Valley has deep sharp cliffs off to the right, so Cornwallis was sent off to the left as a flanker past Dilworthtown while Howe attacked Washington head on at Chadd's Ford. It was to be the largest battle of the whole Revolutionary War. When Washington found himself facing encirclement, he had to order a withdrawal. To skip a few events now memorable to the Main Line suburbs, Philadelphia was essentially then occupied without a further fight, with the British set up their defenses at Germantown, seven miles from the center of town. Three weeks later, Washington attacked Germantown in a three-pronged assault that mainly failed because two of his formations attacked each other in the fog. That was October 4, 1777. The news soon reached them that Burgoyne had surrendered the other British army --starving in the woods -- at Saratoga, New York on October 17. Howe had in effect abandoned Burgoyne in order to take Philadelphia, but it was probably as much a result of getting drawn into a tangle, as a single decision to disregard the grand plan.

In retrospect, it was quite a bad choice. All the world -- and the King of France in particular -- could see that Washington had beaten Howe at Trenton and then Gates and Benedict Arnold had soon beaten Burgoyne at Saratoga. General Gates, of course, was in charge at Saratoga, but Arnold was the flamboyant hero. Adding to his earlier exploits in Quebec and later providing the captured cannon of Ticonderoga for General Knox to drag over the mountains to Boston, thereby allowing Washington to drive the British fleet to safer distances, Arnold now essentially won two more battles at Saratoga. The first was to defeat Leger, who had been sent down Lake Ontario to come back up the Mohawk Valley to Albany. Then, turning his troops through the woods, Arnold joined Gates at Saratoga and defiantly led the charge that smashed the British line, when Gates would have been satisfied with containment. Arnold, like Alexander Hamilton, was a flamboyant man after Washington's heart.

Meanwhile, Howe settled down to enjoy winter at Philadelphia. His court jester and chief entertainer were Major Andre, who took wicked pleasure in using Ben Franklin's Market Street home as his own. There was additional satisfaction in knowing that Washington was freezing at Valley Forge.

Privateering, War Supplies, and Inflation

|

| The Battle of Trenton |

Embattled soldiers have always picked up the weapons of the fallen enemy. In the Revolutionary War, however, other sources of supply were so limited, and the number of captured enemy ships so large, that privateering was an unusually large source of supplies for Washington's army. At the Battle of Trenton, Washington was only able to attack the Hessians because of a single lucky supply ship arriving in Philadelphia. The famous cannons captured at Ticonderoga and dragged to the rescue of Boston were mounted on the overlooking bluff and frightened the British warships away from the harbor. But the cannons were Washington's bluff indeed; he lacked gunpowder to fire them.

|

| William Bingham |

During 1777 however, William Bingham's captured prizes from the Caribbean and privateers commissioned and built in the New Jersey pine barrens, inflicted serious harm on British shipping. During one year it was estimated that 800 British ships were captured; one British spy reported he counted over 80 prizes in the harbor of Martinique on one day. Of course, these battles consumed gunpowder, lost ships with all hands, and sometimes had very little gunpowder on board, to begin with. Nevertheless, the huge volume of captured shipping, in a day when most ships carried some guns, led to this activity becoming a major source of war supplies to the pitifully underarmed Patriots.

From a different viewpoint, the system of sharing the booty with the crew of the victorious privateer led to sudden enrichment of the woodsmen and farm boys who sailed on the Predator fleet. This presented serious competition for recruiting the Continental Army and spread pockets of general inflation when the exuberant sailors reached home port. Ultimately, all of these commotions caused serious problems for Robert Morris and others who were responsible for recruiting and paying soldiers, as well as keeping the economy running. Naturally, the merchants and farmers would prefer to sell to the navy, tattered though it might have been, rather than to the army which would as likely commandeer what they needed, as pay for it.

Battle of Monmouth

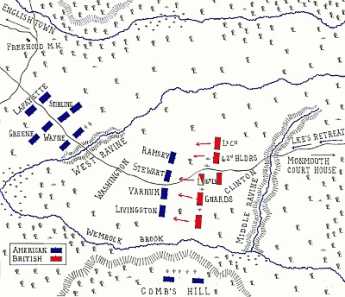

|

| Battle of Monmouth |

A moving army tends to get strung out on roads through unfamiliar territory, and when boarding ships leaves a steadily diminishing rear guard to protect the fleet. Thus, General Clinton's retreating British army presented an opportunity for Washington to harass them, take advantage of unexpected delays, and to be wherever they were going. So Washington ordered the Continental Army out of Valley Forge, to pursue the retreating British as they moved over the Delaware River to Camden, joining the King's Highway at Haddonfield, heading for Sandy Hook and the waiting ships of the British Navy. As both armies approached Monmouth Court House, Washington caught up with Clinton and ordered his deputy, General Charles Lee, to attack with an advance force that would hold the British in place until Washington's main force could catch up. Both armies had about 13,000 soldiers in strength, but only 9,000 of Clinton's men were engaged because of their strung-out deployment.

|

| Battle of Monmouth Map |

Washington's battle plan was therefore vindicated, and the next showed his characteristic ability to use terrain to his advantage. The New Jersey countryside breaks up into hills as it approaches New York harbor, and its valleys between hills tend to contain creeks at the bottom. Therefore, the retreating British were forced into narrowing valleys which exposed them to flanking maneuvers but reduced the room for Washington to be outflanked. Lee failed to take such effective advantage of the terrain and made only half-hearted attacks on the British. When Washington and the main body of troops caught up with him, Lee was promptly relieved of command and later court-marshaled. In his place, Washington sent Nathaniel Greene around the enemy's southern flank, setting up four artillery pieces on a high hill, protected from British attack by a flooded creek. He was thus able to "enfilade" the British line, aiming cannonballs at the near end where they would bounce up the British line if they fell short, or land in the far end of the British line when they overshot. The cannons now look fairly small and puny, but with a well-trained crew of a dozen artillerymen, each one could get off five to ten shots a minute. With four pieces of artillery, they could drop twenty to forty shots a minute onto the confused and compressed formation of enemy troops. The battle went on all day, the longest battle of the Revolution.

Under the cover of darkness, Clinton withdrew his troops toward Sandy Hook, leaving six hundred casualties on the ground, two-thirds of the British. The British could claim they achieved their objective of reaching the ships, but with greater casualties, and forced to withdraw in the face of discovering a much better-disciplined American army than they had ever faced. They acquired a new respect for Washington, who demonstrated boldness and outstanding tactics, with professionalism quite equal to their own.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey in the American Revolution: Barbara J. Mitnick: ISBN-13: 978-0813540955 | Amazon |

Day One: Camden to Cape May

Settlements for three centuries have clustered along both sides of the Delaware Bay, like beads on two parallel strings.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

The Capital of southern New Jersey alternated between Salem and Burlington, and the King's Highway ran between them atop a clay ridge all of fifty feet above sea level. Colonial villages are strung along Kings Highway about ten miles apart, just like villages in the Midwest and for the same reason. That's about the distance a farmer's wagon could travel to market and return in one day. Travel by boat modified that somewhat. One unexpected feature: the marl clay ridge was eventually found to contain the first known dinosaur bones, still proudly on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences. We'll defer until Day Two describing the interesting origins of the coastal route on the Delaware side of the bay below the big river bend at Salem. In New Jersey the counterpart is the Del-Sea Drive, now rapidly fragmenting in response to school crossings and traffic. Although almost everything of interest is along these three roads, for this tour we propose taking President Eisenhower's interstate highway system, with side-trips as needed.

The retreating British Army ferried out of Philadelphia in 1778, went from Camden to Haddonfield and turned north on King's Highway. For this tour, we turn south from Haddonfield, pausing for a glance back at Camden. Poor Camden scarcely exists anymore, but the battleship New Jersey is parked there, the waterfront view is awesome, and Walt Whitman's home is open to tourists. Once the home of shipbuilding, Campbell's Soup, RCA/Victor, and the terminus of railroads at the ferries to Philadelphia, the town was first threatened by isolation by the Pennsylvania Railroad going down the other side of the river in 1839, but ultimately made economically redundant by the construction of the Ben Franklin Bridge in 1926. An interesting sociological study called Camden After the Fall relates how one futile effort after another to restore Camden after 1950 led only to riots and chaos; it's difficult to suggest anything which has not already been tried and abandoned. The present unstated but relentless approach is to tear the obsolete buildings down as they deteriorate, leaving vacant land which will eventually coalesce and become attractive to developers. Toll houses could be found along the turnpike to Haddonfield until 1960, but the automobile made Camden obsolete. What's left begins with the suburbs five miles away.

|

| New Jersey Line |

Haddonfield was a plain little Quaker town with undiscovered dinosaurs buried underneath it until the Revolution when the fugitive New Jersey legislature met in the Indian King Tavern and created the State of New Jersey. Because the Pennsylvania/New Jersey fortifications of the Delaware River at Fort Mifflin/Red Bank blocked the British fleet, Hessians were sent to attack New Jersey's Fort Mercer from the rear, staying overnight in Haddonfield. One young Quaker, a famous runner, ran ten miles to alert the defenders of Fort Mercer, who then defeated the Hessian attackers the next day by pretending not to notice the Hessians until they suddenly turned around and ambushed them. Later on, after the British occupied Philadelphia, General "Mad Anthony" Wayne rounded up cattle in Salem County and drove them to Trenton, then over to Valley Forge to relieve Washington's starving troops. The British responded to this with a famous massacre in Salem County by cavalry under Col. John Simcoe. So off we go to National Park, originally called Red Bank because of the reddish color of the clay riverbank at that point on the river, to see Fort Mercer. From here we travel to Salem, seeing its sadly dilapidated Colonial buildings, and the oak tree which was already famous among the Indians for its huge size in 1683. Along King's Highway, we pass through Mickleton, Mullica Hill, and Woodstown, three cute little Quaker villages waiting to be overwhelmed as suburbs.

From here we go to Greenwich, named for Connecticut settlers, where Paul Revere stirred up a tea-burning party in sympathy with the Boston event, on his way to promote even greater agitation in Philadelphia. Greenwich is sometimes referred to as a second Williamsburg, but what's here is original, not reconstructed. In passing, this tour takes us past Hancock's Bridge where Simcoe massacred those farmers who sold cattle to Anthony Wayne. That's biased local history speaking; in fact, Tory-Rebel reprisals were very bitter on both sides. Until ten years ago, this blood-stained site stood alone in the lonely moors, but unfortunately, it's pretty much built up and harder to find in the new suburbs than it was in the reeds.

From Greenwich we go on to Cape May, with a brief detour to Bivalve. The point about this stop is the perfectly gigantic pile of oyster shells left over from the days as a center of oyster harvesting. Notice the roads; they're paved with oyster shells. Oysters eat algae, sewage fertilizes algae. Overfishing the oysters caused rotting algae and bacterial overgrowth in the river. The result was depletion of the dissolved oxygen, dead areas for fish, murky water instead of a clear stream. It's an opportunity for oyster farming, but the vast piles of shells at Bivalve are a warning of how far we have to go before we restore the river.

Cape May was the first Atlantic Ocean beach resort, reached from Philadelphia and Tidewater Virginia by boat long before roads were usable. We are told Cape May was originally a separate barrier island, joined to the rest of South Jersey only later. It was once a whaling port, and the Quakers of the region were more related to Nantucket than to Philadelphia. Whale-watching is popular here, but dolphin sightings are more reliably frequent. As you would expect, this cute little place has many fine restaurants and hotels. The hotels are so authentic that strangers share common bathrooms the way they always used to do, so bed and breakfast places can be preferable for snootier tourists. Those whose great-grandparents once stayed in places like the Chalfonte, however, find it important to rough it in traditional summer places. The ocean currents "tumble" the small stones in the beach so beach-walkers can amuse themselves looking for "Cape May Diamonds". Unfortunately, even the locals often have never heard of them, so you are probably on your own. From here, we take the forty-minute ferry ride to Lewes, Delaware.

Cape Henlopen, on the Delaware side of the entrance to the bay, is south but appreciably to the east of Cape May. That means that a line directly west from Cape May points well inside the mouth of the bay, to Slaughter Beach, or Mispillion Point on the Delaware side. The ocean salt water turns to fresh river water at about this level, making for remarkably good fishing at certain times of the year. Furthermore, horseshoe crabs come ashore here on both sides of the bay to lay eggs. Birds who took off from South America months earlier swoop out of the skies to eat the crab eggs on the appointed day. Hawks pause in the woods to fly together in flocks over the bay, based on their own signals. Mispillion Lighthouse is the greatest place on the Atlantic flyway for bird-watching, crab-watching, fishing and nature loving. But you have to know when to go there and remember the best local hotels do get filled up at those times.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

| Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City: Howard Gillette Jr.: ISBN-13: 978-0812219685 | Amazon |

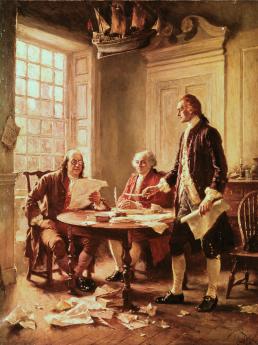

Unalienable Rights Before 1776

|

| Magna Carta |

In 1976, the bicentennial birthday celebration of the Declaration of Independence contained two major exhibits of its conceptual origins. Mr. H. Ross Perot of Texas loaned his copy of the 1215 Magna Carta, and the Proprietors of West Jersey loaned their 1677 original of William Penn's Concessions and Agreements to the colonists of New Jersey. The purpose of the exhibit was to emphasize the historical origins of the concepts within the Declaration, but even the language of the Concessions is remarkably similar, quite evidently lifted by Jefferson when he was writing. On one point, Penn had the better of Jefferson; he correctly wrote about inalienable rights, while somehow Jefferson gave us unalienable ones.

|

| William Penn |

The matter came up recently at a Socrates meeting of the Right Angle Club, where at least one member felt there was no such thing as a natural right, while others wavered. In discussing the rights which the Creator, William Penn and/or Thomas Jefferson may have given us, the various contexts must be held in mind. At the time of declaring our intention to sever relations with Britain's King, there was no Constitution to refer to as a source, and it was impolitic to assert the rights had been given by English kings, like King John. Therefore, the language cleverly short-cuts around the divine right of kings to make a direct connection between the Creator and the colonists. William Penn on the other hand, was a real estate promoter, offering enticements and assurances to prospective colonists who were naturally fearful of risking their lives in sailboats, only to face the possible tyranny of a vassal king who might be even worse than the anointed one. Not only did Penn renounce any suggestion of a Royal role for himself, but went to considerable length describing the legally binding concessions and agreements he was offering. The right of trial by jury, for example, became a right to be punished only by a jury of twelve of one's neighbors. He wasn't talking to lawyers, he was making important distinctions very clear to laymen. These were not rights given by a Divinity who could be trusted, nor something which grew out of Mother Nature. They were the personal promises of William Penn, in personal legal jeopardy of the English courts if he reneged on them. He even had a ready answer for those who discovered the religious language in legal documents -- the Quaker belief that, occasional appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, There is That of God, in every man.

|

| H. Ross Perot |

As a small sidelight of the Concessions document, it had long been housed in the little brick hut on Main Street in Burlington NJ, where the Proprietors of West Jersey keep their treasures. The obscurity of these papers was probably their best protection, but the risk of displaying them in Philadelphia at the centennial brought out the need to ensure them, hence to appraise their value. The figure of four million dollars was kicked around. Ross Perot might have felt comfortable with this sort of expense as the natural cost of being a rare book collector, but it seemed highly unnatural to Quakers. Sometime afterward, the Surveyor General, William Taylor, was awakened by a call from Burlington neighbors that someone was trying to break in the roof to steal contents of the Proprietorship building. The burglars were unaware that underneath the shingles, the roof was actually made of concrete a foot thick. So the perps were frustrated in their aims, but Bill Taylor was greatly troubled by the implications, actually unable to sleep at night worrying about what was in his custody. So, in time the State of New Jersey constructed a suitable archives building, and the valuable documents were transferred up to Trenton. Time will tell what the Soprano State does with such a valuable possession, but at least the Quakers can now sleep at night.

Perth Amboy to Trenton (2)

|

| Declaration of Independence |

The Revolutionary War had been raging for a year in New England before the Declaration of Independence, a point that never ceased to bother John Adams whenever Thomas Jefferson or his devotees took credit for "starting" the Revolution -- a year after the Battle of Lexington and Concord -- with a piece of paper nailed to a lamp post. To be fair, this interval of a year allowed for the organization of the Continental Army, and Washington's growing military maturity by the summer of '76. But it also explains the landing of Sir William Howe's army on Staten Island at the end of June 1776. A month or so later, his brother Admiral Howe landed some more troops. By September 1776, not all of the signers had yet put their names to the Declaration of Independence, but there were about 40,000 British troops parading around the essentially uninhabited Staten Island in New York harbor, in plain sight of the inhabitants of New Jersey's capital in Perth Amboy, scarcely a mile away.

The British were quite shrewd in selecting New York harbor as the center of their operation, since their Navy was able to move quickly from New Jersey to Rhode Island, up and down the Hudson as far as Albany, and around the considerable expanse of Long Island, not to mention Manhattan. Meanwhile, Washington was faced with crossing numerous rivers to defend hundreds of miles of shoreline, and moving foot soldiers to the necessary position. He tried to defend New York, it is true, but the battles on Brooklyn Heights, Harlem, Fort Washington, and Fort Lee were essentially unwinnable, and the best he could do with the situation was escape with an undestroyed army.

By the fall of 1776 Howe had consolidated his hold on New York, and Washington was reduced to scattering clusters of troops around the places Howe might next choose to invade at any time. In early December, he started landing in New Jersey and marched toward New Brunswick. Washington thought that meant he was going to head for Trenton, and then down Delaware to Philadelphia. There was not much to stop him except skirmishers and Minute Men, but it was not safe for Washington to move his troops from the New York region until the intentions of the British were really clear, by which time it would probably be too late to stop the advance.

Since the Raritan Strip along which Howe and Cornwallis were advancing, was prosperous and Tory, things went pretty well for the British. After two weeks march, they finally arrived in Trenton around December 20. In this triumph, they failed to appreciate the significance of several things, however. Washington was hurriedly summoning about six little colonial armies of five hundred to a thousand men each, to join him now that the intentions of the enemy were clear. Furthermore, the Whigs or rebels of New Jersey were aroused in the Pine Barrens of the South and the hills of the North; New Jersey was not as Tory as it seemed during the initial march down along the Raritan. And, finally, the British and Hessian mercenary soldiers had ravaged the countryside almost as much as the spinmeisters of the Whig patriot cause shouted out they had. The Quaker farmers were particularly upset by the activities of the camp followers, who pillaged curtains and other things not normally attractive to marauding soldiers. And the sharpshooters, loyalist, and rebel were close enough to their own homes to dispose of another booty. It was a cakewalk from New Brunswick down to Trenton, but it was not going to be the same coming back.

Washington got ready to defend the Capitol in Philadelphia, and the wide Delaware river was the best place to do it. When Howe and Cornwallis reached Trenton, they found no boats available for miles up and down the New Jersey side of the river, artillery was planted in strategic places on the Pennsylvania side, ice was beginning to form on the river, it was cold and the December days were short. To the British commanders, Washington posed no particular military problem with his naked ragamuffins. Howe had some lady friends in New York, while Cornwallis was planning to spend a month in London before the spring military season. So the British generals made an overconfident miscalculation, and posted their troops in winter quarters, strung out in outposts from Perth Amboy to Trenton and down to Bordentown. A thousand Hessians were quartered in Trenton. By December 20th, it looked like a peaceful but boring Winter.

REFERENCES

| The Pine Barrens: John McPhee: ISBN-13: 978-0374514426 | Amazon |

New Jersey: A Keg Tapped at Both Ends (2)

The New Jersey legislature first fought for Independence, then about debts, then railroads and corporations, and now -- about debt, again.

|

The New Jersey legislature ratified the Declaration of Independence in the Indian King Tavern of Haddonfield, then moved to Princeton and ever since has been in Trenton. The Statehouse in Trenton is the second oldest in the nation, after the one in Annapolis, although it has grown like a snail with the original building nestled inside many additions. In one sense it is totally unique; it's the only state capitol in the nation where you can look out a window and see another state. It's right on the water's edge of Delaware, a hundred yards from those Hessian barracks that Washington surprised in 1777.

|

| Rivals, North and South |

In its early years the legislature concerned itself with raising troops during the Revolution. After that, it spent a great deal of time settling debts to pay for the Revolution. From that arose the traditional rivalry, even hostility, between the northern and southern halves of the state. To some degree, this reflects the two original provinces of East Jersey (Scottish Quakers) and West Jersey (English Quakers), but the Quaker character persisted much longer in West Jersey. The northern half, with many Dutch settlers spilling over from New York and Congregationalists from Connecticut, evolved into mainly a population of debtors; debtors enjoy inflation because it cheapens the cost of their repayments. The southern half of New Jersey, persistently Quaker in the settlement, was where creditors lived; creditors want to recover the value of the money they risked, so they hate inflation. The Mason Dixon line, extended, would cross southern New Jersey. However, it was the northern half of the state which favored the Confederacy during the Civil War, whereas the Quakers in the south were strongly opposed to slavery. Later on, irritation over permitting Atlantic City gambling was one of the various issues which eventually prompted South Jersey to try to secede from the northern spendthrifts; the secession proposition was actually on the ballot in the late Twentieth Century. Up until 1966 the Republicans always dominated the Senate, but that was because each of the 21 counties had one senator, and you can't gerrymander county lines. Then, it was deviously proposed that the state should be re-divided into 40 numerically equal Senatorial districts (i.e. instead of counties); the Senate has had a Democratic senatorial majority more or less ever since, in spite of numerous Republican majorities in state-wide elections. The legislative districts in the Assembly are reapportioned every ten years to respond to the new census; it is close to the facts that the subsequent gerrymandering of that decennial reapportionment effectively forecloses the politics (and predicts the agenda outcome) within the Assembly for each subsequent decade. In recent years, state Congressional delegations have all become increasingly polarized as a result of partisan gerrymandering. New Jersey leads the way in this unfortunate process: the Assembly and the Congressional delegation are polarized in what has become a national pattern, but in addition, its state Senate is permanently gerrymandered by substituting "districts" for "counties", and redrawing the boundaries in the state constitution.

|

| The Amboy and Camden Railroad |

Over time, the early legislature devoted most of its time to chartering corporations, because there were no universal corporation laws and each new corporation required a separate legislative charter. During the early Industrial Revolution, a great many new businesses sought the authority to limit investor liability. Each corporation had its own enabling act and hence its own deal, its own set of rules and conditions open to limiting amendments by competitors or favorable restatement at the urging of lobbyists. Along came the first railway in America, Stevens's conception of the Amboy and Camden Railroad. The New Jersey legislature, no doubt persuaded by private inducements, not only gave the Amboy and Camden permission to use eminent domain to acquire its right of way, but also conferred a perpetual tax exemption, and perpetual railroad monopoly. For the next fifty years, the legislature then concerned itself with hardly anything except railroad matters. As Willie Sutton said about banks, that was where the money was.