3 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

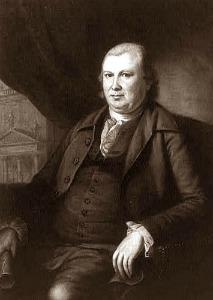

Robert Morris' United States

Robert Morris of Philadelphia created many of the best features of the United States. His face might be carved on Mount Rushmore if he hadn't created one really bad feature, as well.

Robert Morris: The Dark Side

The richest man in America suddenly was locked in debtor's prison, $12 million in debt. While in prison, he reduced that to $3 million, and got released under a new bankruptcy law he helped devise.

A Change of Era

A maxim of the book-editor trade is "Deviate from chronology at your peril." Two events may have little to do with each other, but it always remains possible to show the earlier event had somehow affected the later one. An editor may know little about a topic, but he knows that much.

|

| Dean Donald Kagan |

In 2011, I was privileged to be a tuition-paying student at one of Yale's Directed Studies Courses. An invention of former Dean Donald Kagan, the DS courses take an important era in history and apply three conventional faculty disciplines to it at once: Philosophy, History, and Literature. For the undergraduates, courses range in chronology from Ancient Greek to the Enlightenment; so far, the alumni just get the Greeks. Judging only from the course in Ancient Greek, the unspoken thesis soon emerged that a major era experiences permanent changes in history, philosophy, and literature, but the connection between the three is often loose, requiring some pondering to make the connections firm. Aeschylus does have a connection with Plato, and Aristotle with Thucydides but it remains unclear why the connection exists. Furthermore, you can lump these things or split them; Ancient Greece fits naturally with the Roman Empire, but it can also stand alone. Therefore, although the Yale faculty tends to lump the American Revolution with The Enlightenment, a consideration of the life and times of Robert Morris, Jr. fits naturally with both the Enlightenment and the American Era, because the American part of the Enlightenment bifurcates abruptly when Morris stood in debate with William Findlay in the Pennsylvania State House in 1798 -- and lost.

|

| Robert Morris |

Morris was the richest man in America or close to it, the unofficial President of the United States in its darkest hours, the most brilliant non-academic innovator in Western Finance, the leader of American high society, the only man beside Roger Sherman to sign the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. Morris did not realize it but he was within a few months of going to jail for three years, then spending his final five years in secluded disgrace. Robert Morris was not accustomed to closing arguments, but he lost this one, concerning the wisdom of renewing the charter of the Bank of North America, the first real bank of the country. He lost an argument he should have won easily. In retrospect, the new modern American Era was beginning, and he was apparently on the wrong side of it. Politically, that is. Speaking purely of banking and finance, he was a century ahead of his time.

|

| Ancient Greek Gods |

It seemed to me and my alumni classmates that the idea of examining a historical period like the ancient Greek one in the light of three different academic disciplines, gradually assumed considerable merit. The philosophy department examined beliefs which underlay action, and the history department described what those actions turned out to mean inhuman affairs. But the literature department came far closer than either of the other two, to imparting to a reader just what it was like to be an ancient Greek. Professor Kagan seems to have a really good idea here, although it must be resource-expensive to develop, academically. Three departments of Academia have to come to some sort of agreement about the whole synthesis, an agreement which surely must not have been present at the start. It must be a process highly similar to a medical school teaching about a disease, with coordinated input from pathologists, surgeons, and internists. A nice idea, but terribly labor-intensive of labor of the highest quality. Book editors would say it is safer to stick with chronology as an organizing principle if you plan to do a lot of organizing. Nevertheless, I must express my gratitude to Yale for allowing me to be a spectator at an experiment conducted by masters of the thinking trade. Its results must be judged by standards other than the usual ones.

Robert Morris Has a Mid-Life Crisis

|

| Robert Morris |

The feudal system once consisted of Kings awarding aristocrats a title of nobility attached to a region of inhabited land, usually as a reward for military assistance. Because of this link between their wealth and their land, almost no aristocrats migrated to America, so almost no American can now claim hereditary noble descent. What developed instead was the gentry. Regardless of the often unclear sources of their wealth, it was presumed to have arisen from some ancestor's merit, and could only be inherited if it could be made to renew itself. The vast expanses of America cheapened the value of undeveloped land, so the gentry could seldom support a gentry lifestyle without additional employment of some sort. Their children went to college, an experience originally developed for training ministers, who were expected to be the nation's leaders in balance with the tradesmen, who made no secret of their own self-serving. The expectation of community leadership for the gentry outlasted its original attachment to religion, so the non-religious gentry moved about with an air of superiority which others envied but increasingly resented. The novels of Jane Austen are filled with depictions of this sort of person during a period when they were actually rapidly disappearing. The primitive financial system and the enduring mythology of the aristocracy struggled to guide the income sources of this gentry into tracts of resalable land, where they lived off dividends, profits, and rents. Rentiers. Not quite tradesmen, but not genuine aristocrats, either.

Unfortunately, the huge abundance of land in the New World soon cheapened its value to a point where it could not support a lifestyle of entitlement along with contempt for mere tradesmen. This is the explanation often offered for the virtual disappearance of the lifestyle of the Gentleman by the time of the Civil War. The situation was rescued by the invention of corporations; a single man or family no longer could supply all the capital needed to exploit the available commercial opportunities, so corporate ownership was shared with others. Ownership of shares in corporations provided a new stream of income and a new storehouse of wealth, and it also freed the gentleman from ties to a big estate of land. The Jane Austen variety of gentleman thus virtually disappeared but remained as a mythical model for the highest aspirations in the early 19th Century. Robert Morris, orphaned and illegitimate, wanted very much to be an immensely rich gentleman even though that was becoming a contradiction of terms. And although he had virtually been in charge of the whole nation during the Revolution, he wanted very much to be looked to as a leader, then defined as some variant of a theologian. Much of this ambivalence was due to his never going to college, the same guilt which haunted George Washington. Neither of them had sufficient college-educated relatives to appreciate how little college has to do with it. A great deal probably did have to do with historical animosities between Eastern and Western Pennsylvania, between Quakers and Presbyterians, between memories of lingering hatreds among Irish tribes along Ireland's northern border. And yes, between anthracite and bituminous coal. Mountains seem to foster wild behavior, and there are a lot of mountains in Central Pennsylvania.

|

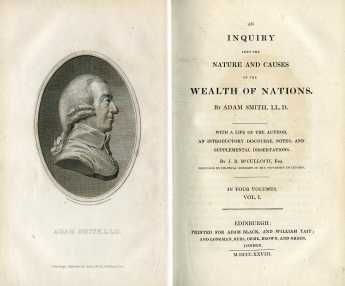

| Adam Smith: Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations |

The outcome of these commotions, as well as others unrecognized, was highlighted by the constant difficulties Robert Morris had in the Pennsylvania legislature, contrasted with his comparative ease in both the local Philadelphia political scene and the national one. Only at the state level did it seem that everyone was against him. Particularly so were Findlay and Smilie, western Pennsylvanians who hated him for his self-made wealth but refused to acknowledge the abilities it must surely represent. Like the Lees of Virginia, they asserted the burden of proof was on him, to prove he had not stolen his wealth. After all, all tradesmen were petty cheaters, so a very rich tradesman must be a big cheater. And even setting that aside, he had an odor of sanctity, an air of superiority, which they could not abide. There was even a centrality to this matter resting on Adam Smith, who published The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Smith argued that good things grew out of vigorous competition, and definitely not from altruism. Although Morris was sufficiently taken with Smith's arguments to give copies to his friends, he would not surrender the point that wealth was not necessarily proof of merit, just because merit sometimes led to wealth. Findlay freely admitted he was opposed to the re-charter of the Bank of North America in order to promote the self-interest of western farmers. What flabbergasted Morris was to hear his motives vilified for favoring the re-charter when he owned shares of the bank. Nowadays, everyone would feel astounded if a corporate executive did not vigorously defend his company; but in those days he stood shame-faced to admit he could not possibly be a gentleman and do such a thing. He, therefore, decided to prove his honor by taking an astonishing step. One of the richest men in America sold out his business to prove to these wizened backwoodsmen that he was truly acting like a gentleman. It would be hard today to find anyone who would not describe his action as that of a damned fool.

How Could an Honest Man Go Bankrupt?

|

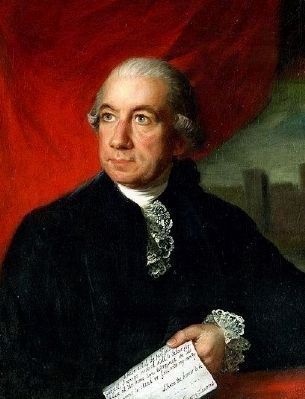

| E. James Ferguson |

James Ferguson was a Twentieth-century historian who spent most of his life compiling and editing the papers of Robert Morris covering the four years (1781-1784) he was in charge of American finances. Although Ferguson was strictly impartial or even somewhat censorious, he made the statement that he had never discovered any instance of Robert Morris engaging in self-dealing or dishonesty in handling government affairs. Likewise, Arthur Lee, who certainly qualifies as Morris's worst enemy, was in charge of a Congressional investigation of the accusations of Morris as corrupt which finally led to the conclusion that no dishonesty had been found. If any corruption is found in the future, it must thus be found in some remote corner of a mountain of careful bookkeeping by a man who was mostly too rich to bother with the immense task of covering his tracks with double books. And Morris really was very rich. One contemporary scholar, a historian for the Independence Hall Park Service, estimates that until things began to crumble, Morris was as rich in present value as Bill Gates. A quick check of that assertion would start with his unpaid debts of $12 million at the time he went to debtors prison, and then adjustment for intervening inflation. The snarling assumption that no man could get to be that rich -- honestly -- is the as yet unsupported belief underlying any smug satisfaction, then and now, with his legal downfall.

|

| British Navy |

This amounts to astonishing denial. Although many billions of dollars have been amassed by many contemporary financiers of only single facets of investment banking, persisting suspicion implies it was justified to imprison a man who invented maritime insurance, central banking, commercial credit, the substitution of credit for paper currency, the organization of a privateer navy which fought the British Navy to a standstill, financed the Revolutionary War and the importation of almost all its munitions in spite of the sinking of 150 of his own ships. Morris effectively ran the Revolutionary government while he did these things-- not only an astonishing series of accomplishments in four years but seemingly quite enough achievement to attain wealth. Instead, one hears especially in Virginia, the implacable conviction that no one could possibly do all that, honestly.

Or alternatively, the thesis might be advanced that only passionate idealism would drive a man of such talents to such exertions, gently alluding to his seemingly disgraceful refusal to sign Jefferson's Declaration of Independence at the vital moment, which is accepted as sure proof of duplicity. Somehow this offense cannot be expunged by his rescuing the finances of the War when the whole Continental Congress was lost in the blind alley of inflation and price controls, on the edge of letting Washington lose the battle of Trenton for lack of gunpowder. Or largely by his own efforts getting the Articles of Confederation ratified after five years. Or, discovering their vital weaknesses, setting about to rectify them in a new constitution, and driving it through the ratification by Pennsylvania. The system of checks and balances then mysteriously emerged, without clear identification of whose idea it was. It certainly sounds like Hume and Adam Smith. They weren't present at the Constitutional Convention. But Morris was, with a lifetime of matching willing buyers with willing sellers, in mutually advantageous binding agreements.

The Silas Deane Affair

..

Morris Upended by a Nobody

THE Revolutionary War ended militarily with the Battle of Yorktown in 1781, and diplomatically with the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The careers of Washington and Franklin appeared to be complete, while the economic and financial career of Robert Morris seemed likely to stretch for decades into the future. But as matters actually turned out for these three fast friends, it was Washington who was propelled into a new political career, Franklin soon died, and Morris got himself into a career-ending mess. The financial complexity and economic power of the United States did grow massively in the next several decades, but unfortunately, Robert Morris was soon unable to exert any leadership. At the end of Washington's eight years as President, the power of the Federalists, and particularly the three men most central to it, was coming to a close. John Adams had a tempestuous single term, and then Federalism was all over.

|

| Robert Morris |

The end of the Eighteenth century marked the end of The Enlightenment and the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, accompanied by many national revolutions, not just the American one. This was a major turning point for world history. The momentum of these upheavals still continues, but it is clear that the Industrial Revolution of which the Morris banking revolution was an essential part swept the world far faster than the social and political revolution, in which he also played a pivotal role. In the banking and industrial revolution, it is universally agreed that Morris was almost always right. In the social and political world, it is conversely agreed he was quite wrong. Essentially, Morris assumed that a small minority, an aristocracy of some sort, would rule any country. Within weeks of the ratification of the new Constitution, or even somewhat in anticipation of it, America made it clear that replacing an aristocracy of inheritance with an aristocracy of merit would not satisfy the need. Morris, born illegitimate and soon an orphan, was obviously in favor of promotion based on merit. John Adams defined leadership even more narrowly; he said a gentleman was a man who went to college, and he probably meant Harvard. Nobody extended the leadership class to include Indians and slaves, but the backwoodsmen of Appalachia made it clear that power and leadership at least included them. Thomas Jefferson was the visible leader of this expansion of the franchise, but changed his mind several times. James Madison switched sides; Thomas Paine switched in the opposite direction. The leaders of Shay's Rebellion and the Whiskey Rebellion lacked coherence and consistency on this point; instead of agitating for a refined goal, they mostly seemed to be running around looking for a leader. William Findlay, on the other hand, knew what he wanted. The issue might be defined as follows: it was obvious that hereditary aristocracy was too small and too inflexible to suffice, but it was also obvious that every man a king was too inclusive. An expanded leadership class was needed, but its boundaries were indistinct and contentious. But to return to Findlay, who at least had a clear idea of what he wanted.

|

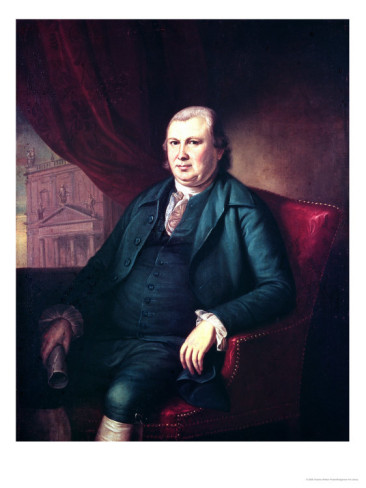

| William Findlay |

William Findlay was a member representing Western Pennsylvania in the State Legislature, in 1785. It would be difficult to claim any notable accomplishment in his life; he was largely uneducated. The new leadership class must, therefore, include both the uneducated and the mediocre. The Legislature at that time met in the State House, Independence Hall, in Philadelphia, where no doubt the unconventional dress and manners of backwoodsmen did not pass without audible comment. Findlay made his own political goals quite explicit; he was for paper money to facilitate land speculation which could make him rich. Wealth was a goal, but it did not confer distinction. The rights of the Indians, the rights of the descendants of William Penn, the rights of the educated class and the preservation of property were all just obstacles in the way of an ambitious man who had carefully studied the rules. Everybody's vote was as good as everybody else's, and if you shrewdly controlled a majority of them, you could do as you please. If this meat-ax approach had any rational justification, it lay in the essential selfishness of every single member of the Legislature, working as hard as he could to further his own interest. If someone controlled a majority of such votes, then the majority of the public were declaring in favor of the outcome. Those who believed in good government and the public interest were saps; the refinements of education mostly just created hypocritical liars. There was a strain of Calvinism in all this and a very large dose of Adam Smith's hidden hand of the marketplace. If you were rich, it was proof that God loved you, if you were poor, God must not think much of you, or He wouldn't have made you poor. Findlay had the votes and meant to become rich; if his opponents didn't have the votes, they could expect soon to be poor. In this particular case, the vote coming up was a motion to renew the charter of the Bank of North America. Findlay wanted it to die.

|

| America's first bank, the Bank of Pennsylvania |

It came down to a personal debate between Findlay, and Robert Morris. Morris had conceived and created America's first bank, the Bank of Pennsylvania. Today it would be called a bond fund, with Morris and a few of his friends put up their own money to act as leverage for loans to run the Revolutionary War. After a short time, it occurred to Morris that the money in a bank could be expanded by accepting interest-bearing public deposits and making small loans at a higher interest rate, which is the way most banks operate today. Accordingly, a new bank called the Bank of North America was chartered to serve this function, which greatly assisted in winning the Revolutionary War. There was no banking act or general law of corporations; each corporation had its individual charter, specifying what it could do and how it would be supervised. When the charter came up for renewal, Findlay saw his chance to kill it. Morris, of course, defended it, pointing out the great value to the nation of promoting commerce and maintaining a stable currency. The reply was immediate. Morris had his own money invested in the bank and only wanted to profit from it at the public expense. His protests about the good of commerce and the public interest in stable money were simply cloaking for this rich man's greed to make more money. Findlay made no secret of his interest in reverting to state-authorized paper money, which could then be used by the well-connected to buy vast lands in Ohio for speculation. There were enough other legislators present who could see welcome advantages, and by a small majority the charter was defeated.

|

| John Hancock |

At this point, Morris made a staggering mistake. After all, he was a simple man of no great background, largely uneducated but fortified by his ascent in society from waterfront apprentice to the highest of social positions, a friend of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin, acclaimed as a financial genius, the man who saved the Revolution, very likely the richest man in America. For many years, he had harbored not the slightest doubt of his personal genius, his absolute honesty, and total dedication to the welfare of his country. To have this reputation and accomplishment sneered at by a worthless backwoodsman, a man who would stoop to using the votes of other backwoodsmen to accomplish self-enrichment, was intolerable. Morris announced and actually did sell out his entire business interest as a merchant, at a moment when he fully understood the new nation was about to enjoy an unprecedented post-war boom. So much for his self-interest. It helps to understand that John Hancock and Henry Laurens had done the same thing in Boston and Charleston, against what we now see as a strange aristocratic tradition of prejudice against bankers and businessmen. In even the few shreds of aristocracy now surviving in Britain and Europe, the tradition persists that a true aristocrat is so independently wealthy that no self-interested temptations can attract him away from purest attention to the public good. The original source of this wealth was the King, who conferred high favor on those who served the nation well. A curious exception was made for wealth in the form of land, the only dependable store of tangible wealth, and transactions in land. Wealth was something which came from God and the King in return for public service. Land ownership was its tangible storage and transfer medium. Otherwise, grubbing around with trade and manufacture was beneath the dignity of a true gentleman.

|

| Henry Laurens |

We now know what was coming. Wealth was soon to be the reward of skill and merit, recognized by fellow citizens in the marketplace, by consensus. Findlay and his friends wholly accepted this conclusion, unfortunately skipping the merit part of it for several decades. In their view, you were entitled to the money if you had the votes. As the nation gradually recognized that rewards must be durable, and once granted were yours to have and to hold, the new nation gradually came to see the need for durable ownership of property. Unless or until the owner places it out at risk in the marketplace, legislative votes may not affect its ownership. Our system ever since has rested on the three pillars of meritorious effort, assessment of value by the free market, and respect for pre-existing property. That's quite a change from the Divine Right of Kings, and therefore quite enough material to keep two political parties agitated for a couple of centuries. And quite enough change to bewilder even so brilliant a victim as Robert Morris.

The Revolution is Over, Every Man for Himself

|

| Charles Dickens |

A DOZEN episodes from American revolutionary times might be called pivotal, but a single debate in the Pennsylvania Legislature seems to have begun our political parties in their present form. Two debaters, their topic, and its consequences all rise to dramatic, even operatic, heights. In another place, we intend to explore the clashing philosophies of the Eighteenth century, with Hegel and Hume at the apex, but two quotations from Adam Smith are more intelligible. Charles Dickens nearly ran away with the topic in his novel A Tale of Two Cities, but Charles Brockton Brown and Hugh Henry Brackenridge were local authors, Pennsylvanians present at the scene. John Adams and Thomas Jefferson debated for decades about which of them was the main protagonist. But all of that is the background for one operatic scene at Independence Hall, where the real David and Goliath were William Findlay and Robert Morris.

|

| Robert Morris |

Robert Morris, it must be remembered, was probably the richest man in America, a signer of the Articles of Confederation, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution. He was one of three men, including Ben Franklin and George Washington, about whom it could be said: the Revolution could not have been won without them. Morris essentially invented American banking, founded the first bank, the Pennsylvania Bank, invented investment banking, corporate conglomerates, American maritime insurance, and dozens of financial innovations. His merchant house probably had 150 ships sunk by the enemy. George Washington lived in his house for years. Today, he is mostly remembered for going bankrupt at the end of a busy life.

|

| William Findlay |

William Findlay, on the other hand, was a Scotch-Irish frontiersman with a flamboyant white hat, elected by others like him from the Pittsburgh area to promote inflation through state-issued debt paper, so as to finance land speculation in the West. He had no education to speak of, no accomplishments to mention. He made no secret of his self-interest in land speculation, and therefore no secret of his opposition to rechartering the Bank of North America, which Morris had founded for the purpose of restraining inflation and speculation. Findlay wanted the bank to disappear, get out of his way, and he boldly denounced Morris for his self-interest in promoting a bank where he owned stock. He utterly denied that Morris had any motive other than the profit he would make for the bank, so in his opinion, they were equal in self-interest. Let's vote.

Prior to that time, Findlay had politically defeated Hugh Brackenridge, using the two strong arguments that Brackenridge had gone to Princeton, and written poetry; how could such a person possibly represent the hard-boiled self-interest of frontier constituents?

|

| Hugh Brackenridge |

Morris was positively apoplectic at this sneering at everything he stood for. As for the country's lack of trust in a man who had risked everything to save it, well, what has he done for us, lately? America had lately thrown off the King, but what it had really discarded was aristocracy. Every man was as good as every other man, and each had one vote. Under aristocratic ideals, a man was born, married and educated in a leadership class, expected to be utterly disinterested in his votes and actions, scrupulous to avoid any involvement in trade and commerce, where temptations of self-interest were abundant. Washington never accepted any salary for his years of service and even agonized for months when he was awarded stock in a canal company, wanting neither to seem ungrateful nor to make private profit. John Hancock, who came pretty close to having as much wealth as Morris, gave up his business when he was made Governor of Massachusetts. Benjamin Franklin was only accepted into public life when he retired from the printing business, to live the life of a gentleman. That's how it was, everywhere; every nation had a king and depended on rich aristocrats to supply the leadership for war and public life. But, now, America had become a republic where every man was equal. Morris and the Federalists he represented wanted to turn the clock back to an era that would never return.

Goaded too far, Morris impulsively resigned his business interests, to prove he had the nation's interest at heart in opposing inflation. It didn't help. Findlay won the vote, and the Bank of North America was closed. America was ashamed of how it behaved after the Revolution, but not ashamed enough to change.

REFERENCES

| Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution: Robert Morris: Charles Rappleye: ISBN-10: 1416570926 | Amazon |

Two-Party Ideologies

|

| Together |

Although they try to be subtle about it, the American political parties reverse their positions fairly often on issues. Indeed, there are several times when parties reversed positions with symmetry, each taking what was formerly the other party's position. For example, the Republican Party stood in defense of protective tariffs throughout the last half of the 19th century, while in the 21st century Democrats now take the pro-tariff position, and it is Republicans who hate it. If you look for the ideological center of the parties, it is not to be found in tariffs. Nor in taxes; the Federalists, effectively predecessors of the present Republican Party largely based their whole party on rewriting the Constitution to enable the Federal government to levy taxes. But more recently it might be fair to observe they allowed George Bush (41) to lose his 1992 presidential re-election campaign because he abandoned the "No new taxes" pledge. Twenty years later, the Tea Party is still on the warpath about holding taxes down. The difference between this Tea Party and the original (Boston)one is that now the Tea Party is in the hands of rock-ribbed conservatives instead of rowdy rebels.

On the question of how many parties to have, there is fairly uniform agreement that two is best. Third parties, or splinter parties, do appear from time to time but in retrospect can mostly be viewed as steps in repositioning one or both major parties. Our system of nomination depends on the utterly pragmatic question, "Can he win?", and cheerfully dumps some candidate the leadership really likes best if he seemingly can't win. The stability of our seemingly haphazard system emerges from two eventual choices, each chosen because shrewd analysts think they have the best chance with the public. The Constitution's authors hoped there would never be any political parties, but it is arguable that the remarkable stability of our government depends on them. More ideological leadership in other countries has led to many more political parties, each held by a tighter leash. The result has surprisingly been much less stability, because each splinter party is led by someone who imagines himself a Spartan at Thermopylae, determined to and usually successful at, dying for his cause. To those less cerebral about politics, one final pragmatic argument is offered: In our two-party system, the deals are made before the election, and the public is asked to choose between two best-effort products. In a multi-party system, the deals are made after the election, often requiring several efforts to get a workable coalition. And, having already voted, the public has surrendered its control over the composition of the deal.

R. Morris, Land Speculator

|

| Robert Morris |

In many recent years, someone becomes a millionaire through real estate speculation; it can be done. However, no one supposes it is easy to do, or free of risk. It would be foolhardy for anyone who knew nothing about real estate speculation to step forward, buy huge tracts of land, and expect to multiply his wealth in a year or two. That is, however, essentially what Robert Morris, Jr. did in 1785. Like his friend Benjamin Franklin, Morris was acutely sensitive to the prevailing notion that public leadership was only fitting for gentlemen, and a gentleman did not, could not, must not, engage in trade. The world was then in transition between an era when a gentleman was one of the few educated people around, a man who had attended college as John Adams described it, and who was able to live in upper-class style as a result of inheriting well or marrying well. The time was soon to arrive when public service was equivalent to improving the national economics through invention or organization, but a decade or two earlier, public service was military or diplomatic. Morris got caught in the transition.

Suddenly caught in a society he did not understand, Morris renounced his achievements as a merchant, considerable but tainted with society's disdain for scrambling for personal advantage; and as the expression goes, cashed out. Aristocrats were still understood to own vast tracts of land, however, and somehow an estate was not tarred with a commercial brush. An opportunity opened up quite soon to acquire the land along the Genessee River in upstate New York, with Morris turning it over quickly to new migrant settlers at such a profit that it was rumored he was once again the richest man in America. However, the land was cheaper and more abundant in America than in Europe, subject to violent fluctuations as immigration flourished and declined along with the economics and wars of Europe. The supply of land in the new continent was nearly inexhaustible, while the supply of immigrants was highly variable. Without a safe place to park idle money temporarily, Morris plunged on, buying land with money made on other lands, not yet paid for. Many of his customers were just as innocent as he was, but others were savvier and more ruthless. That was peculiarly true of the Scotch-Irish, who having been evicted first from Scotland and then from Northern Ireland, were among the first American immigrants to recognize real estate as a simple commodity, to be traded unsentimentally.

Robert Morris, Land Speculator

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

IN 1782, Robert Morris the Superintendent of Finance of the United States, produced a paper called "On Public Credit", which was the model for Alexander Hamilton's more famous paper with the same name. His interest in the topic almost surely grew out of the idea of selling America's abundant land to finance the Revolutionary War. It was obviously a tempting idea, but a fairly unworkable one under wartime conditions, particularly since the great abundance of American land depressed its price for long-term speculators, compared with European land. A price of fifteen or twenty cents an acre required huge parcels of land to justify the problems associated with deriving a profit from it as an intermediary, and created a myriad of other problems dealing with the end user; in 1782 it just wouldn't work.

|

| Henry George |

By 1792 it was perhaps workable because the boundaries of the nation were more clear, but generated the problems of a rolling frontier, associated with steep and volatile differentials of price and safety. If the end user was an impoverished immigrant, the seller was necessarily tangled in protracted periods of refinancing. The issues of slave territory and free territory close by generated local peculiarities of land use and optimum parcel size. Those who gave close attention to the complexities of the novel situation could see the close relationship between the credit of the nation, and the value of its land mass, the ultimate definition of what the nation really was. Thus in time, the single tax idea of Henry George would be an idea that kept coming up for discussion, long before Henry George popularized the concept of placing all taxes on immobile land. The nation was the land it owned, and the land couldn't move. So Morris and Alexander Hamilton wrestled with devising ways to base the credit of the nation on its land wealth, without the complexities of doing so directly. In 1782 such ideas were only dreams, but by 1792 a clever person might work out ways to manage it.

|

| Robert Morris |

As the opportunities of suddenly having undisputed ownership of most of a continent began to clarify, Morris was rearranging his own life. He had accomplished most of his vision of what the nation should be like and had resolved his internal conflicts about the meaning of being a patrician in a democracy, by selling off his business. No matter how strange it may seem to us that being a shipping merchant was disrespectable, while real estate speculation was an acceptable gentleman's occupation, that was apparently how he saw it. His many associations put him in contact with many opportunities, and soon he acquired the parcel of land in upstate New York abandoned by the exterminated Iroquois. Generally called the Genesee territory, the combination of smallpox and General Sullivan's famous march had greatly reduced the tangled arguments about the title to the land, and the sales went very well, netting him roughly $350,000 unadjusted for inflation. If Morris had quit the business right then and there, he had a fair chance of living the rest of his life among the richest men in America.

Lest the impression persist that Morris got into financial difficulty entirely by real estate speculation, a letter he wrote to Gouverneur in 1790 celebrating the Genesee agreement exulted, "This bargain will not only be the means of extricating me from all the embarrassments in which I have become involved, but also the means of making your Fortune and mine."

In 1794 the Asylum Co. was founded by U.S. Senator Robert Morris and John Nicholson, Pennsylvania Comptroller General, to develop and sell lands in northeastern Pennsylvania. Although it was rumored that Marie Antoinette was to be housed in the 1600 acres on the North branch of the Susquehanna River near the present Towanda, she had actually already been executed in late 1793. In 1795 Nicholson succeeded to Morris' interest, and three years later Morris was put in debtor' prison. In 1802, Napoleon invited all French emigrants to come home, and only a few stayed behind in Azilium. The Asylum Co. soon dissolved.

REFERENCES

| Robert Morris: Financier of the American Revolution: Charles Rappleye: ISBN-10: 1416570926 | Amazon |

Richard Henry Lee: A Pennsylvania Viewpoint

|

| Patrick Henry |

Although Colonial Massachusetts was combative and outspoken in its demands for liberty, somehow, pacifist Quaker Pennsylvania still got along with Bostonians reasonably well. It was Virginia that was always in Pennsylvania's face, proud, loud and defiant. Patrick Henry was certainly one of Virginia's leaders, but most of the time it was the residents of Westmoreland County VA who wrangled with Pennsylvania, people with names like Washington and Lee. Some of this animosity had to do with competition for access to the Ohio territory through Pittsburgh, some of it was a strong difference in attitude toward the Indians, whom the Quakers sought to treat as equals. Eventually, there was a division over slavery. Arthur Lee had attended Eton College no less and was often the agent who acted out the repeated efforts to stir Pennsylvania from its torpor about rebellion against England. But very likely it was his brother Richard Henry Lee who schemed the most.

|

| Richard Henry Lee |

Richard Henry Lee was the author of the Westmoreland County Resolution of 1765, which essentially proclaimed to the neighbors that anyone who cooperated with the Stamp Act was going to be sorry about it. It was the same Richard Henry Lee who introduced the Virginia Resolution of June 1776, declaring that:

Americans are and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

Hotheads of Virginia and Massachusetts formed a political group at the Continental Congress, usually referred to as the Eastern Party. The leadership of a Moderate Party was less clearly defined, but Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, and Robert Morris probably qualified. It was almost pre-destined that Morris and Franklin would have trouble with the Lee brothers, especially when Arthur was the spokesman and Richard Henry the ringleader. Like cats and dogs, they seemed to have been some sort of genetic antagonism; topics under dispute tended to vary. No doubt, Robert Morris' enormous wealth and the ease with which he accumulated, even more, irritated the Virginia gentry whose tobacco farms were starting to exhaust their topsoil. For his part, Morris was not likely to be deferential, merely to their ancestry. Morris did sign the Declaration of Independence a month late, but under the circumstances, he could no longer vote for it; Richard Henry Lee had written the Virginia Resolution which glorified the very crux of it. A Secret Committee was soon formed to obtain arms and gunpowder, including Morris and Franklin; Richard Henry Lee saw to it that his brother Arthur was added. When Arthur was sent to watch out for Morris' agent Silas Deane in Paris, Arthur got sent along to stand guard, stirring up endless trouble with Foreign Minister Vergennes. When the Lees finally caught on to the system of sending American products to France on ships that would return with gunpowder, they wanted Franklin removed, Robert Morris' brother Thomas removed, and another Lee brother William added to the group in charge of exchanging goods with the Frenchman Beaumarchais, who was a particular Lee favorite. When Beaumarchais indicated a strong preference for tobacco as the product most in demand in France, it must have set off bells in Richard Henry Lee's head. The Lee home region of Westmoreland County in Virginia dominated the tobacco trade. But Robert Morris was himself a second generation tobacco trader; the Lees had little new to teach him about tobacco. Time and again, Morris defeated the Lee brothers in some such petty quarrels. Gradually, the Lees lost credibility, particularly after scholars began to discover evidence that when the Stamp Act was enacted, Richard Henry Lee had applied for the job of a local agent, and had been rejected.

The Lees were not always in the wrong. Thomas Morris was indeed a hopeless alcoholic and an extreme embarrassment to Robert. But a more fraternal relationship might have led to Lee helping Morris ease Thomas out while concealing his indiscretions; he could have made a friend of Robert Morris for life. Morris was certainly willing to play this game; he praised Arthur Lee in public for his assistance in monitoring the secret committee, a description which at this distance is simply hilarious. John Adams in Paris might be forgiven for taking Puritanical offense at Ben Franklin's exuberant Parisian high life. It is likely the Virginia Cavaliers looked at dalliance through the same lens as the Adams family, disliking Franklin and Morris for having a jolly time, and worse still being acclaimed for it.

Real Estate Bubble Traps Robert Morris

|

| Treaty of Paris |

When the Treaty of Paris finally ended the eight-year American Revolutionary War, it was approximately true that the ownership of the whole North American continent changed hands. The activities of the war had to be wound down, old debts settled, and the new Industrial Revolution had to be addressed. Deflation was certain as wartime activities were eliminated, but inflation also loomed as a result of new peacetime activities. A whole new government had to be started, a whole new set of rules created. In retrospect, things worked out pretty well, but at the time it seemed like unmanageable catastrophes on all sides. Apparently, Robert Morris decided that the greatest opportunity existed in land speculation, so he concentrated in it as he was winding down many other activities.

His first major land speculation was in a million acres in the Genesee country. He soon tripled the value of this investment; if he had simply retired at that point, he might have retired as one of the richest men in the country. Some personality flaw drove him onward, however, and he soon had acquired four million acres of upstate New York property on which he approximately broke even. He next acquired large tracts of central Pennsylvania along the whole Susquehanna River, offering the Azilium venture to French investors and Northumberland to Joseph Priestley and the Unitarians. Both of these utopian ventures were largely abandoned by the settlers, because of the French reign of terror, and the disaffection of Priestley's English followers. Because he hoped to keep the new National Capital on the Delaware River while struggling with western Pennsylvania interests who wanted to move it to Harrisburg, he invested in thousands of acres of Pennsylvania land around Morrisville, across the river from Trenton. Needless to say, the capital was not moved to Trenton, so after two centuries the land is still sparsely settled.

|

| Morris Folly |

Finally, when sales were sluggish, six million acres from Virginia to Georgia were combined into a gigantic real estate trust in order to make the speculation more appealing to smaller investors in large numbers, which accounts for Talleyrand himself buying 100.000 acres, as well as drawing the participation of John Bull, himself. But by 1797 the world began to know that the real estate bubble was in danger, and many related ventures started to fail. In a complicated set of circumstances, it is hard to know which failure was more important than the others, but the general opinion emerges that Morris' main speculative failure was centered on land speculation. It must be mentioned, however, that in 1793 Philadelphia experienced one of several Yellow Fever epidemics, the French, as well as the English, were seizing American vessels and crews, the Whisky Rebellion took place in western Pennsylvania, and that Morris in what must either have been a public relations stunt or else a moment of temporary madness, began construction of a new home for himself in Philadelphia. Located on an entire block between Chestnut and Walnut at 7th Street, it was to be the most ornate private residence in America, with two levels below ground and two above, decorated with imported marble and endless extravagant fixtures. By itself, this house widely known as "Morris' Folly" could not have bankrupted him, but it may well have stripped him of ready cash when short term debts were more pressing than long ones, starting a cascade of forced distress sales at low prices. Furthermore, as though there needed to be a furthermore, tobacco had been the preferred return cargo in the transatlantic munitions trade. Tobacco does not spoil, so when prices were low, Morris often held it off the market to await higher prices. He thus was engaged in wide-spread zero-sum trading, where either you or your counterparty is likely to be cleaned out. That can make for a large accumulation of enemies, quite willing to destroy credit even further with accusations of unfair dealing. The Lee family was certainly in a position to fan the flames of such commercial antagonisms, both among creditors and in Congress. When all is said and done, to ascribe the bankruptcy of Robert Morris to land speculation is not perfectly accurate, but close enough. Particularly if credence is given to his own reflection that, had he quit after the Genesee transaction he could have lived the rest of his life as the richest man in America, land speculation seems a better psychological explanation for his behavior than many other complicated maneuvers, now too obscure to be worth explaining.

|

| David Hartley |

Debtors prison now seems like a barbaric and cruel treatment of unpaid debts, but at least in Morris's case, it may not have seemed the worst of it. His entire inventory of personal effects on entering debtors prison on February 16, 1798, included three writing desks, an old Windsor setee, and eight old Windsor chairs, six chests stuffed with papers, a mirror, a trunk of clothes, and a bed. However, he had many visitors, including Gouverneur Morris and George Washington. His debts were twelve million dollars, which he reduced while in prison to three million, so this world-class workaholic was probably relatively happy to concentrate on business affairs. His wife Mary undoubtedly suffered far worse humiliation in her small house on 12th Street while he was confined than he did, busy with his bookkeeping. Although she saw a few friends, she essentially withdrew from society until August 21, 1801, when he was released. Morris himself probably experienced his worst suffering from 1793 to the time he finally surrendered to the sheriff in 1798, a period of five years of uncertainty, gloom, dashed hope and offensive behavior by his 90 creditors. There must have been times when he truly believed he might survive the struggle, and other times when he had to keep up a brave front when he knew in his heart he could never make it. Nevertheless, scraping together nine million dollars while behind bars would be a remarkable achievement today, and certainly an amazing one for 1800. America had no bankruptcy laws at the time, and he managed to persuade Congress to create them for the many victims of the severe financial panic. Even for the vindictive, the provision in the law that release from debtors prison was conditional on a favorable petition from his creditors, made it unlikely that he could persuade 90 creditors to do it. But he did so and walked out a free man. Or rather, he walked out a dejected and humiliated has-been, a zombie creeping the streets. Perhaps that was the worst.

His will.

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Last Will and Testment of Robert Morris, Jr.

|

| Robert Morris |

This will of Robert Morris of Philadelphia, dated June 13, 1804, is found in Volume E, p. 170 of the Hardin County, KY will books. It was presented by William Fairleigh to Samuel Haycraft, Clerk of the Hardin County, KY Court, in his office on March 23, 1849.

In the name of God Amen, I Robert Morris of the City of Philadelphia formerly a merchant & c. do now make and declare this present writing to contain and to be my last will and testament hereby revoking all wills by me made and declared of precedent dates.

Imprimis I give my Gold watch by my son Robert, it was my Fathers and left to me at his death and hath been carefully kept and valued by me ever since.

ITEM I give my gold-headed cane to my son Thomas. The head was given to me by the late John Hancock Esq when President of Congress and the cane was the gift of James Wilson Esq whilst a member of Congress.

ITEM I give to my son Henry, my copying press and the paper which was sent to me a present from Sir Robt Herries of London.

ITEM I give my daughter Hetty (now Mrs. Marshall) my silver vase a punch cup which I imported from London many years ago, and have since purchased again.

ITEM I give to my Daughter Maria (now Mrs. Nixon) my silver (?) Boiler which I also imported from London many years ago and which I have lately repurchased.

ITEM I give to be Friend Gouverneur Morris Esq my telescope espying glass being the same that I bought of a French refugee from Cape Francois then at Trenton and which I since purchased of Mr. Hall officer at the Bankrupt Office.

ITEM I give and bequeath all the other property which I now possess and may hereafter be acquired whether real or personal or all that shall or may belong to me at the time of my death to my dearly beloved wife Mary Morris for her use and comfort during her life and to be disposed of as she pleases at or before her deceased when no doubt she will make such distribution of the same amongst our children as she may then think most proper. Here I have to Regret my [? at] having lost a very large fortune acquired by honest industry which I had long hoped and expected to enjoy with my family during my own life and then to distribute it amongst those of theirs that should outlive me. Fate has determined otherwise and we must submit to the decree which I have done with patience and fortitude.

Lastly--I do hereby nominate and appoint my said dearly beloved wife Mary Morris the Sole Executrix of this my last will and testament made and declared as such on this thirteenth day of June 1804.

Robt Morris (Seal)

Declared and acknowledged by Robert Morris as his last will and testament to and in our presence this sixteenth day of June AD 1804 H. Keugan and Gaucet(?) Cottringer

Philadelphia May 21, 1806 There personally appeared Henry Keugan and [?] Cottringer the witnesses of the foregoing will and on oath did depose and say that they saw & heard Robert Morris the testator sign, seal, publish and declare the same as and for his last will and testament and that at the doing thereof he was of sound mind, memory and understanding to the best of their knowledge and belief.

J. Waupole Dep Regr

The [?] sworn May 29, 1806

City and County of Philadelphia I certify the foregoing writing to be a true copy of the last will and testament of Robert Morris decd. as also of the probate thereof as the same remains on file in the Registers Office and recorded in Will Book No. 1, page 4980. (or 4981) Witness my hand and seal of office this seventeenth day of February AD 1849. A. Brown, Register

Pennsylvania Philadelphia County SS

I Edward King Esq President of the First Judicial District of Pennsylvania and Presiding Judge of the Court of Common Pleas Orphans Court, and Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for the County of Philadelphia do certify that A. Brown by whom the annexed Record, Certificate and Attestation were made and given, and who in his own proper handwriting hath hereunto subscribed his name and affixed his official Seal was at the time of so doing and now is, Register for the Probate of Wills, and granting letters of Administration, in and for the City and County of Philadelphia in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, duly commissioned and qualified to all whose acts as such, full faith and credit are and ought to be given as well in courts of Judicature as [?] and that the said Record, Certificate and Attestation are in due form and made by the proper officer.

In Testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand the Twenty-first day of February eighteen hundred and forty-nine. Edward King, Presd. Judge

State of Kentucky Hardin County Sct

I Samuel Haycraft Clerk of the County Court for the county aforesaid, do certify that on this day the Foregoing Copy of the Will of Robert Morris deceased duly authenticated, was produced to me in my office by William Fairleigh Esquire and at his Request I have duly recorded the same in the will book in my office this 23. day of March 1849. Saml Haycraft Clk

Those Troublesome Lees of Virginia

|

| Richard Henry Lee |

SOMETHING useful can, of course, be learned from a man's friends, but descriptions given by his enemies are usually briefer. The Lee family of Westmoreland County Virginia were bitter enemies of Robert Morris the Financier of the Revolution, and they surely said some unfair things about him. Morris paid as little attention to the Lees as possible, but for generations, the Lees had been neighbors of the Washingtons, and so could not be completely brushed aside. Furthermore, they were close to the center of Thomas Jefferson's anti-Federalist party. So insights into the Lee family probably illuminate the main disputes before, during, and after the Revolution. They even illuminate the mixed character of George Washington, who was sometimes unusual by Virginia standards. Nevertheless, the Lees had the same quality of heedless idealism to be found in Samuel Adams of Massachusetts and Patrick Henry of Virginia which goes beyond the ability of two-feet-on-the-ground revolutionaries like Robert Morris and Benjamin Franklin to understand, or even abide; this conflict runs throughout the history of the American founding. It seemed to baffle even those who switched positions, like James Madison going in a leftish direction, and Thomas Paine, going toward the right. So, although reckless idealism cannot be an inborn character, it must quickly acquire very deep roots.

.jpg)

|

| Arthur Lee |

Arthur Lee and his brothers William and Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, were passionate rebels of the Patrick Henry ("Give me liberty or give me death") sort, intermittently reviving lifelong attacks on Robert Morris. Highborn Tidewater aristocrats, they were ancestors of Virginia's revered General Robert E. Lee. Arthur had even attended Eton College and later studied medicine in England. The Lee brothers started attacking Robert Morris well before his famous abstention from the critical 1776 vote on independence. It's much too easy to shrug the Lees off as landed aristocrats who disdained self-made men, or as passionate Jacobins who hated self-made rich people, or maybe just narrow-minded nuts. Out of their often inaccurate attacks emerges an outline of what a lot of other people thought about Robert Morris. Many of these polar mind-sets outline the main divisions of political strife in America right up to the present. For present purposes, let's try to understand why Morris might risk his substantial fortune in underground smuggling before the war, and then dedicate his huge energies to winning the war -- while at the same time, not only refuse to agree to the Declaration of Independence (he did finally sign it in August 1776), but speak out in public opposition to independence. What explains Morris' apparent double-talk?

<The explanation I choose to accept is that Robert Morris' real feelings were too sophisticated for this particular crisis, reaching clearer expression in his later activities promoting the Articles of Confederation and its revision the United States Constitution. A man given to terse one-liners, Morris said in December 1775 that he joined his fellow Americans in striving for "Constitutional Liberty" but could not join them in promoting independence.

Morris was never explicit about what would achieve Liberty without Independence; perhaps something like the independent Irish parliament which English Whigs then supported, or the Scottish local parliament which exists today, was in his mind. Both of them link a single King to a commonwealth. At the time, no one was interested in the political philosophy of a shipping merchant.

But today we are in a position to see no member nation of the British Commonwealth has a written constitution; written constitutions are a comparatively recent innovation and not necessarily an essential one. The American Constitution today continues to argue about original intent and living documents, so it is still possible to prefer the wisdom of a benign King to written constitutions. The British goal seems to be to infuse overarching principles of government so deeply into citizen minds that such principles overwhelm any written commandments, however vague all that may sound to outsiders who prefer to niggle over documents. Not in America, of course, because an immigrant nation like ours cannot grow cultural roots sufficiently deep in a few generations, and must have written rules. Great Britain's recent difficulties with immigrants from the Commonwealth may well reassert the limits of unwritten constitutions; constant questioning of the written American constitution by more recent immigrant groups may become a part of the British life, too.

The Articles of Confederation were written by the eminent lawyer John Dickinson, said to be the man closest to sharing Robert Morris' political philosophy. However, for five years the Articles were unratified, and Morris began to believe this lack of ratification was the reason the states were so resistant to taxation. So Dickinson gets credit for writing the Articles, but Morris must be seen as their father. Believing the lack of federal taxation was the main difficulty, and blaming the unratified Articles as the reason for it, our businessman man-of-action pushed them through. Unfortunately, with the Articles it didn't work because the taxation problem still remained, so Morris turned his immense energies toward replacing the Articles with something which would work. It does not twist American history a great deal to believe that Robert Morris, Jr. was one of the main driving forces behind both the Articles of Confederation and the Constitution of the United States. He was neither a lawyer nor a political scientist and therefore was quite indifferent to who got credit for the documents. As Ronald Reagan was to discover two centuries later, that's one of the best ways to get anything done.

Morris could read; he knew the Articles didn't endorse Federal taxation. But he was apparently convinced an unwritten constitution always contains the latitude to do what simply has to be done; anything else amounts to shooting yourself in the foot. After the Battle of Trenton, when Morris became President of the United States for three months in everything except name, he still blamed his troubles on the inability to levy taxes, which in turn was due to failure of the states to ratify those Articles. So sensible a man as John Dickinson would never assume overly strict interpretation was intended; obviously, a state must confiscate private property when otherwise it cannot survive. After five years of state inaction, Morris abruptly pushed the Articles through to ratification. But he was wrong, it didn't help. When he finally grasped that the explicit limitations on taxation were intentional, intended to override any implicit power in the Articles whatever, he promptly threw his weight behind John Jay, George Washington, and James Madison to support a new Constitutional Convention setting it right, especially the national government's ability to levy taxes. Since Washington had by then become his best friend, who actually lived next door in Morris' Market Street house for years, there is not much paper trail of this interaction between these old friends. Once he got his tax mandate at the Convention, however, Morris had hardly anything further to say. His frenetic later activity immediately after the Constitution was enacted can almost surely be attributed to lifelong habits of a negotiator, avoiding mention of anything which might distract from his main goal, in this case of ratifying the Congressional right to levy federal taxes, but not abandoning subordinate goals for a moment. What the Lees hated about Morris, therefore, cannot be easily explained, but certainly, one feature of it was his ability to hold his cards face-down. The Lees didn't hold their cards, they flourished them. In their eyes, no gentleman would do anything else.

The incidents of June 1776 place the Lees in a more favorable light if they are seen as urging instinctive decisions by popular mandate, essentially favoring an unwritten British Constitutional arrangement. The Lees believed the place of a gentleman was at the head of a troop, daring the rest to follow their lead. The British had blockaded Boston, passed the Prohibitory Acts, fought naval battles in the Delaware River in May of that year. A huge British fleet had landed in New York harbor, and the agitated colonists were about to declare war. At the very moment of crisis, that rich Philadelphia merchant had refused to vote for independence. The Virginia tobacco planters were dancing a war dance in a city known for its pacifist Quakers, while their neighbor George Washington was conducting an actual war with the British. It was then revealed that Robert Morris had been participating in a gunpowder smuggling operation known as the Secret Committee, and Morris had made considerable profits from it. While many of his friends defended Morris, it was pretty easy to go wild with indignation about trusting him to sit on a secret espionage committee, unwatched. The very least that could be done was to appoint Arthur Lee, already a member of the Continental Congress, to that Secret Committee to sound the alarm if anything looked funny. The ironic fact seems to be that Morris and the Lees were passionately committed to the same unwritten approach to government, primarily based on trust in personal character, otherwise defined as fidelity to an unwritten tribal code. If you are the right sort of person, you will be with us; if you are not with us, you must not be the right sort of person. Unfortunately, a nation of immigrants may not survive if it adopts too many such notions.

The Lees had expressed disruptive views of Morris in the past, but they were exactly the sort of clan likely to confront scoundrels whenever facts called for it, and sometimes even when they didn't. The underlying conflicts, fiercely advocating both a strong centralized government and a loose decentralized one but not defining either, continue to run through American politics until the present. Whether Morris ever acknowledged it or not, he ended up on the side of defined contracts, as opposed to a Code of Honor. But he spent his life as a man of his word because in business your word is your bond; if you are any good, you won't need to cheat. If our Tower of Compromises is to endure, its limits of such agreement must be few, but they must somehow be strictly understood.

Robert Morris and the Lee Brothers

* * *

Morris was a monarchist, announcing he liked the king and did not want to change him. The Lees, one surmises, though they might make pretty good kings, themselves.

But we get far ahead of the story. The immediate mystery is Morris' behavior in July, 1776.

|

| Robert Morris |

The dominant feeling during 1775 had been that Americans needed to prepare for war while doing everything possible to avert it. If England prevented both the manufacture and importation of gunpowder in the colonies, there was no way to be prepared for war except to smuggle gunpowder. Not to smuggle it would leave the colonies weak, almost inviting abuse from London. In several elections, before then Morris had been the nominee of both the radicals and the conservatives. The radicals could see he was an energetic, efficient and close-mouthed international shipowner; when a Secret Committee was proposed, he obviously would be an effective member of it. But he was loudly opposed to war with England and was formidable in a debate. The conservatives might have felt he would keep the hotheads on the committee from wandering from or expanding its narrow charge. He explained his dual position as seeking "Constitutional Liberty" rather than independence, but that was shrugged off as just so much blather. It would be twelve years before people did understand what he wanted, and that he was entirely serious about it. That the Lee brothers didn't ever understand, didn't bother Morris at all. That the Lee brothers couldn't comprehend his unwillingness to charge headlong into battle, unarmed and unprepared, was equally mysterious to Morris. The Lee brothers would well have understood Napoleon's remark that victory was 10% based on surprise. But what Napoleon is thought to have said was that victory was 90% based on supplies.

|

| Arthur Lee |

The later appointment of Arthur Lee to the Secret Committee can be similarly explained as a counterbalance to Morris. There were no Southerners on the initial committee, so a hothead like Arthur Lee could be counted on to resist the influence of conservative merchants and perhaps Arthur, outnumbered, was even urged to overplay his hand. From the moment he was appointed, he was demanding that Benjamin Franklin be removed from the committee. Not only does this help us understand his disruptive behavior when he later joined Franklin at the Paris negotiations, but such misjudgment of Franklin's patriotism illustrates how extreme Lee's suspicions really were. Since the original motion for independence had been introduced in Congress as the Virginia Resolution by his brother Richard Henry Lee, we sense this family was perpetually anxious to slay dragons. And finally, we can sense the likelihood that Robert Morris and Arthur Lee probably provoked each other.

|

| Richard Henery Lee |

To tolerate for the moment the rather extreme Lee brothers, it must be said there was every reason to suppose Morris hoped to enrich himself from gun running. But that is an entirely different accusation with a different defense. The ambivalent behavior of Morris and Dickinson at the Congress is admittedly puzzling, but in the end, defensible and honorable. The accusation of graft and self-dealing was plausible for uncomprehending people but seems legitimate today only because American standards of leadership ethics have gravitated toward the Virginia viewpoint. That viewpoint can be summarized by George Washington refusing to accept a cent for his years of public service. Very few politicians will today tell you this is a practical position, but nevertheless, many Americans wish it could be. Lacking any insight into what Morris was talking about with "Constitutional Liberty", the Lees were perhaps understandably driven to invent plausible explanations. These seldom proved to be fair. Morris certainly had the sympathy of the commercial world at the time for what was to them quite normal behavior. However, the rural population, especially Cavalier Tidewater Virginians, will probably never yield the point.

Morris repeatedly advised his partners he was serving his nation, while of course engaging in private profit. Even using present standards about self-dealing, it must be admitted the need for secrecy at the time necessitated hiding the smuggling within legitimate businesses. Nowadays we throw people out of a public office on suspicion of enriching themselves and throw them into jail on clear proof of it. There is also a curious feature of extreme mindsets, which seems to justify making false accusations. The underlying theory is that behind every great fortune is a great crime, so you might as well hang him for it without further proof. Morris would have been astonished at the thought of taking such risks without hope of restitution: "Do you want me to smuggle this stuff or don't you?" might well have been his answer.

And then there were those two aristocratic Frenchmen, Penet and Pliage, appearing in Providence RI in a boat loaded with gunpowder, looking for George Washington to sell it to. Everyone at the time assumed they were just adventurers, out for the money. After the passage of two centuries, it may be within bounds to ask the French to look into their records to see if maybe P&P were sent here to stir up a little trouble? There proves to be quite a literature about them, linked to that glamorous Renaissance Man, Beaumarchais.

Pennsylvania's First Industrial Revolution

|

| David Thomas |

We tend to think of 1776 as the beginning of American history, but in fact, the region around Easton was settled a hundred-forty years before 1776, and the forests were pretty well lumbered out. The backwoods lumbermen around the junction of the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers were about to move further west when Washington crossed Delaware and fought the battle of Trenton. This region nevertheless had three essential ingredients for becoming the "Arsenal of the Revolution": It was close to the war zone but protected by mountains, it had a network of rivers, and it had coal. The hard coal of Anthracite had the problem it was slow to catch fire, and iron making in the region didn't really get started big-time until a Welsh iron maker named David Thomas discovered that anthracite for iron making would work if the air blast was pre-heated before introducing it into a "blast" furnace. A local iron maker traveled to England to license the patent from Thomas, whereupon Thomas' wife persuaded her husband to move to Pennsylvania. Blast furnaces only got started into production by 1840, but by 1870 there were 55 furnaces along the Lehigh Canal. For thirty years this was America's greatest iron-producing region. In fact, Bethlehem Steel only closed its last plant in 1995.

|

| Canal Boat |

When iron-making got started, the local industrial revolution really took off, but the more fundamental step was to dig canals to transport the coal to other regions. Canals were the dominant form of transportation for only thirty years until railroads took over, and the entire Northeast of the nation was laced with canals. Curiously, the South had relatively few canals, so their industrialization was too late for canals, and too early for railroads, to help much in the Civil War. The Erie Canal was the big winner, but Pennsylvania had many networks of canals in competition, leading to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, whereas the Erie Canal was more headed toward the Great Lakes and Chicago. Eventually, J.P. Morgan put an end to this race by financing the Pennsylvania Railroad and moving the steel industry to Pittsburgh, where bituminous coal was the fuel of choice. This industrial rivalry was at the heart of the enduring rivalry of Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, as well as the commercial rivalry between New York and Philadelphia. It was more or less the end of the flourishing economy of the "Reach" including Easton, Bethlehem, and Allentown. A reach is a geographic unit sort of bigger than a county, in local parlance. But you might as well include the city of Reading, which concentrated more on railroads and commerce with the Dutch Country. Out of danger from the British Fleet on the ocean, but close enough for war, the "reach" was more or less the forerunner of the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Vietnam in several later wars. The Lehigh Canal stretched from Easton to Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe), the so-called Switzerland of Pennsylvania, only a mile or two West of the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

|

| Blue Mountain |

The Allegheny Mountains stretch across the State of Pennsylvania, and the most easterly of these mountains is locally called "Blue" mountain because of its hazy appearance from the East when seen across a lush and prosperous coastal plain. It represents the farthest extent of the several glaciers in the region, and the two sides of it present quite a sociological contrast. The Pennsylvania Dutch found themselves on the richest farming land in the world, whereas the inhabitants of the other side of the mountain had to subsist on pebbles. The mountain levels down at the Delaware River, so the Dutch farmers and the late immigrants from Central Europe mixed, in the time and region of industrial prosperity. Gradually, the miners and the steelworkers began to drift away, but the Pennsylvania Germans tended to remain where they had been before all the fuss. So the Kutztown Fair is full of Seven Sweets and Seven Sours, the farmhouses are large and ample, and mostly remain the way they were, too. You have little trouble finding a twang of Pennsylvania Dutch accents. But Bucks County in Pennsylvania was cut in half by the glacier, and north of the borderline, you can see lots of pickup trucks with gun racks behind the driver. Everything is amicable, you understand, but for some reason, the tax revenues of the two halves of the County are forbidden to be transferred, even within the same county. Better that way.

|

| Lehigh Marker |

The Lehigh River runs along the North side of Blue Mountain, and trickles down to join the Delaware at the town of Easton. There were only 11 houses in the town in 1776, and now you can see several miles of formerly elegant early Nineteenth century townhouses. At the point where the two rivers join, a lovely little park has been built to celebrate the high point of Colonial canal-making. Hugh Moore, the founder of the Dixie Cup Company is responsible for this historic memory, well worth a trip to see. If you have called ahead for reservations, you can have a genuine canal boat ride, pulled by two genuine mules. When you hear that the boat captain and his family used to live on the boat (Poppa steered, Momma, cooked, and the children tended the mules), it seems small and cramped. But when you climb aboard, you find it holds a hundred people for dinner with plates in their laps. The food is partly Polish, partly Hungarian and partly other things Central European. And the captain plays guitar and fiddle, singing old songs he mostly composed himself. Surprisingly, no Stephen Foster, who held forth about four hundred miles to the West, until he drank himself to death at Bellevue Hospital in New York. Foster was a member of a rival tribe of canal boaters, the ones who traveled down to Pittsburgh via the Erie Canal. Along the Reach, you hear about three canals, the Lehigh, Delaware, and Morris. The first two are obvious enough since they and the railroads which subsequently followed ran along the banks of two rivers joined. The Morris was Robert Morris, at one time the richest man in America, who bought Morrisville across from Trenton on the speculation he could persuade his friends to put the Nation's Capital there. It didn't work out, so he bought and went broke with the District of Columbia. Anyway, the Morris canal went on to New York harbor, where it prospered mightily shipping iron to New York, and iron for the rolling mills of Boston. The Morris Canal went over the Delaware River on a bridge that carried an aqueduct, over to Philipsburg; and then across the wasp waist of New Jersey.

| Posted by: jerry | Dec 26, 2012 9:49 PM |

| Posted by: Andralyn | Apr 22, 2011 6:59 PM |

15 Blogs

A Change of Era

Few historical eras burst upon the world with the suddenness of the American one. It took place in Independence Hall, all right, but even more decisively in 1798 than 1776.

Few historical eras burst upon the world with the suddenness of the American one. It took place in Independence Hall, all right, but even more decisively in 1798 than 1776.

Robert Morris Has a Mid-Life Crisis

Robert Morris baffled everybody by abruptly abandoning his merchant career at the peak of his power. It remains a puzzling action, but somehow it displays American society's confusion as the Industrial Revolution confronted the last of the Enlightenment.

Robert Morris baffled everybody by abruptly abandoning his merchant career at the peak of his power. It remains a puzzling action, but somehow it displays American society's confusion as the Industrial Revolution confronted the last of the Enlightenment.

How Could an Honest Man Go Bankrupt?

By the standards of his day, and for the most part by present-day standards, Robert Morris was a completely honest man.