Related Topics

Benjamin Franklin

A collection of Benjamin Franklin tidbits that relate Philadelphia's revolutionary prelate to his moving around the city, the colonies, and the world.

Right Angle Club 2017

Dick Palmer and Bill Dorsey died this year. We will miss them.

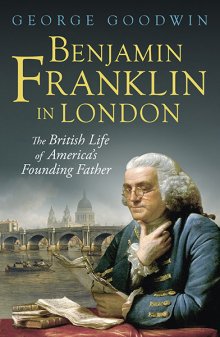

After London, Ben Franklin Revisited

|

| George Goodwin |

George Goodwin appears to have written the best book I ever read, in Benjamin Franklin in London, which that writer in residence of the Craven Street Franklin Museum. has just produced. At least I have never read a book which proceeded to explain so much I knew puzzled me. There have been hundreds of books about Benjamin Franklin, but all of them fall back on Franklin's Autobiography which while surely authoritative, often omits significant details. Goodwin, concentrating on the eighteen years Franklin spent abroad, had access to many unnoticed personal papers. It was also written while Franklin was in England, where many things did not appear to need an explanation to 18th Century Englishmen. And the autobiography was written for his son, who needed even less explanation. So it's a mistake to ascribe the autobiography's vagueness to deliberate deviousness, to say nothing of basing a whole theory of his personality on deviousness. Its hazy points now seem more attributable to his assuming his intended audience needed little explanation for what to us was seemingly left vague. And so as a first impression, Franklin himself emerges less deserving of his reputation for deceptiveness.

|

| Ben Franklin In London |

It occurred to me as I read it, that national opinions will change so quickly, that the transitional opinions of people like me will soon be swept aside. I am no scholar, but have read twenty or so excellent books about Benjamin Franklin, and adopted a number of fixed ideas which I will have to change. Therefore, Goodwin's achievement is in danger of becoming lost in a stampede of permanently revised views. Goodwin himself may be oblivious to his own achievement, which was probably gathered slowly after poring over heaps of primary documents and living in a London world which needed less explaining to a Londoner. Heaven knows I am no Keats, but my place in all this can possibly aspire to his goals in the poem On First Looking into Chapman's Homer.

|

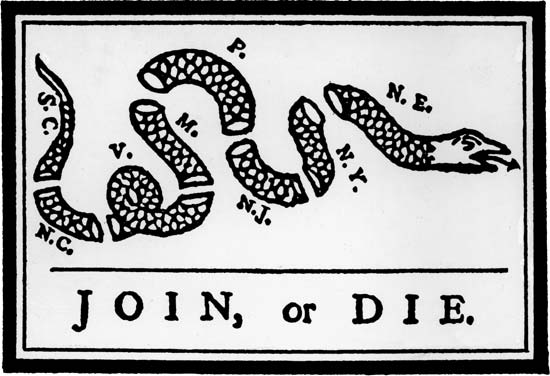

| Join or Die |

In the first place, Franklin appears to have been a staunch British subject, at least from the Albany Conference of 1754 to as late as 1774. His dream, formulated at Albany and expressed in many forms later, was that of a combined British-American empire, with its headquarters eventually to be located in America. For the largest part of his life, his attitude was not that America should be independent of Britain. It was the two nations should unite even more closely, America would inevitably grow larger, and the British Empire would become a British World. After King George III unleashed Wedderburn to excoriate Franklin before the crowned heads of Whitehall, it all changed, of course, but it did so after a personal dispute with the King about lightning rods, where Franklin never doubted he was the world-acknowledged authority. In essence, Franklin was the inventor of electricity, but King George in effect responded, "Who do you think you are, a King?" Those weren't the words they used, but that was the sense of it. Or, considering what was at stake, the nonsense of it. Franklin had been challenged to destroy the British empire if he was so smart, and that is exactly what he set about to do.

|

| King George III |

Without editorializing a word, Goodwin allows us to read a line Franklin wrote in 1773, that King George was "perhaps the only Chance America has for obtaining soon the Address she aims at."

Franklin was not without British allies. Lord Chatham, later Prime Minister, and Edmund Burke, author of "On Reconciliation With the Colonies" came very close to toppling the government over this issue. Even Lord Howe, Franklin's chess partner and brother of even-more-avid chess partner Lady Carolyn Howe, who was later designated to lead the British repression of the rebellion, is quoted as saying in 17XX, XXXXXXXX. Lord Howe's words are going to require some re-examination of his motives in the abandonment of Burgoyne against direct orders, and redirection of the fleet toward Philadelphia. Frankin's response, of course, was to use the victory to sign a treaty of alliance with France.

|

| William Pitt 1st Earl of Chatham |

In victorious America, of course, Franklin was celebrated for flying a kite in a rainstorm, something every schoolboy knows is too dangerous to try. It was during his time in England that Franklin performed a series of experiments which invented electricity which every physicist would agree would today win him a Nobel Prize. It made him a friend of Mozart and Beethoven, Joseph Priestley and five kings. Goodwin even restores the tarnished reputation of Peggy Stevenson.

But it isn't all for the better. Goodwin tells us Franklin didn't invent bifocals, some British optometrist did. So he raises a question, for those who are looking for it, about how many of the other American "firsts" for which he is famous, were ideas he picked up in his first trip to London in 17XX, and transported to an America eager to have what was the latest and trendiest. There are probably other innuendoes in this eminently readable but essentially scholarly work. But I missed them, and a hundred graduate students will have to put the record straight.

Originally published: Saturday, April 30, 2016; most-recently modified: Friday, September 20, 2019