|

|

City Hall

|

The central keel of the city, Market Street, must be considered in three quite different sections, East and West of City Hall, and West of the Schuylkill River. The street was once called High Street, and the name was slow to change. It will be enough, for now, to consider only the oldest section of fourteen blocks from City Hall to the Delaware River, which is almost a lesson in archeology. Start at Victorian City Hall and face East to Penn's landing on the Delaware.

William Penn had laid out the city plan like a cross, with Market and Broad Streets intersecting at the green central park which now holds the massive building with his statue on top of the tower. The market was originally called High Street. It's doubtful that Penn intended his statue to be there, since the early Quakers were so scornful of vainglorious display that they prohibited the naming of streets after persons, declined to have their portraits painted, and the strictest ones would not even consent to their names on their tombstones. The cult of personality in dictatorships like the Soviet Union, Maoist China, and Baptist Iraq more recently illustrate the sort of thing they probably had in mind, and it wasn't just a quaint idea to discourage the portraits of leaders in public places.

For a tour of the area mentioned in this Reflection, visit Seven Tours Through Historic Philadelphia

|

|

The Reading Terminal Market

|

We are about to look at a remarkable

a fourteen-block stretch of street, with several unifying historical

themes, but there is one notable feature which stands by itself. The PSFS

building is now the site of a luxury hotel, but it once

housed the Philadelphia

Savings Fund Society, the oldest savings bank in the country,

having been founded in 1816. Setting aside the place of this

the institution in American finance, and passing quickly by the deplorable

end of it with swashbuckling corsairs in three-piece suits, 1929

the building itself remains so remarkable that the hotel still displays the

PSFS sign on its top. The imagination of the architects was so advanced

that a building constructed seventy-five years ago looks as though it

might have been completed yesterday. The Smithsonian Institution

conducts annual five-day tours of Chicago to look at a skyscraper

architecture, but hardly anything on that tour compares with the PSFS

building. From time to time, someone digs up old newspaper clippings

from the 1930s to show how the PSFS was ridiculed for its odd-looking

the building, but anyhow this is certainly one example of how the Avante

the guard got it right.

At the far Eastern end of Market Street, right in the middle of the

street once stood a head house, which in this case was called the

market terminal building

. In those days, street markets were mostly a line

of sheds and carts down the middle of a wide street, but usually there

was a substantial masonry building at the head of the market, where

money was counted and more easily guarded. An example of a restored

ahead house can today be found at Second and Pine, although that market

("Newmarket") was less for groceries than for upscale shops. The market

on Market Street started at the river and worked West with the

advancing city limits, making it understandable that buildings which

lined that broad avenue gradually converted to shops, and then stores.

The grandest of the department stores on Market Street was, of course, John Wanamaker's,

all the way to City Hall, built on the site of Pennsylvania

Railroad's freight terminal (the passenger terminal was on the West

side of City Hall). In the late Nineteenth Century, the Pennsylvania

Railroad and the Reading Railroads terminated at this point, so

rail traffic flowing east merged with ocean and river traffic flowing

west. Well into the Twentieth Century, a dozen major department stores

and hundreds of specialty stores lined the street, with trolley cars,

buses, and subway traffic taking over for horse-drawn drainage. The

the pinnacle of this process was the corner of Eighth and Market, where

four department stores stood, one on each corner, and underneath them

three subway systems intersected. The Reading terminal market is

Philadelphia's last remnant of this almost medieval shopping concept,

although the Italian street markets of South Philadelphia display a

more authentic chaos. Street markets, followed by shops, overwhelmed by

department stores showed a regular succession up Market Street, and

when commerce disappeared, it all turned into a wide avenue from City

Hall to River, leaving few colonial traces.

The history of Market Street is the history of the Reading Terminal

Market. Farmers and local artisans thronged to sell their wares in

sheds put up in the middle of the wide street, traditionally called

"shambles" after the similar areas in York, England. Gradually, elegant

stores were built on the street, and upscale competitors began to be

uncomfortable with the mess and disorder of the shambles down the

center of the street. By 1859 the power structure had changed, and the

upscale merchants on the sidewalks got a law passed, forbidding

shambles. After the expected uproar, the farmers and other shambles

merchants got organized, and built a Farmers Market on the North side

of 12th and Market Relative peace and commercial

tranquility then prevailed until the Reading Railroad employed power

politics and the right of eminent domain to displace the Farmer's

Marketplace with a downtown railroad terminal that was an architectural

marvel for its time, with the farmers displaced to the rear in the

Reading Terminal Market, opening in 1893. Bassett's, the ice cream

maker, is the only merchant continuously in business there since it

opened, but several other vendors are nearly as old. The farmers market

persisted in that form for a century until the City built a convention

center next door. As a result, the quaint old farmers market became a

tourist attraction, with over 90,000 visitors a week. That's fine if

you are selling sandwiches and souvenirs, but it crowds out meat and

produces and thereby creates a problem. If the tourist attraction gets

too popular, it drives out everything which made it a tourist

attraction; so rules had to be made and enforced, limiting the number

of restaurants, but encouraging Pennsylvania Dutch farmers. Competition

and innovation are the lifeblood of commercial real estate, but they

are always noisy processes. The history of the street is the history of

clamor and jostling, eventually dying out to the point where everyone

is regretful and nostalgic for a revival of clamor.

|

|

Nancy Gilboy

|

The President of IVC, Nancy Gilboy, tells us it stands for International Visitors Council, now approaching its 50th anniversary. As you might suppose, it is located at 1515 Arch Street, near the old visitors center. Philadelphia has a new visitors center on 5th Street, of course, and perhaps it takes time to move or maybe moving isn't in the cards. We had another Visitors center on 3rd Street that came and went, so proximity between Center and Council perhaps isn't as important as rental costs, or leases, or other issues.

|

|

Philadelphia Art Museum

|

The Council has a modest budget, but a great idea. Anyone who has traveled much knows that you tend to follow the travel agent's set agenda for a town, you see a lot of churches and museums, but you can almost never get tickets for the local entertainment events, and you almost never meet any local people except taxi drivers and bellhops. That's even more true of young travelers, who don't have either the money or the experience to anticipate the issue, or enough local friends to guide them around the obstacles (This exhibit closed on Mondays, that event is all sold out, this event was spectacular, you should have been there yesterday, sorry we didn't know you were coming we have a wedding to go to, etc.). On guided tours, it is remarkable how few things seem to happen after 4 PM.

So, fifty years ago, some imaginative Philadelphia leaders got the idea that a lot of Philadelphia residents would enjoy taking some foreign tourists under their wing, maybe have somebody to know when they, in turn, make a reciprocal visit, maybe boast about our town a little. Furthermore, by getting involved with the US State Department, young visitors can be identified as potential future leaders in their country. If the guess is a good one, and the experience favorable, Philadelphia might prosper from the publicity and from the later return visits, now in the triumph of success. That was the founding spirit of the Philadelphia International Visitors Council.

So that's how it came about that Margaret Thatcher, <

Tony Blair, the current President of Poland, and the head of the Russian Space Program were once visitors in Philadelphia homes. People who like to do this sort of thing tend to like each other, so the monthly receptions (First Wednesday at the Warwick) are interesting Philadelphia social occasions in their own right. Success begets success, and the CCP (originally Business for Russia) has affiliated itself, along with the Philadelphia Sister Cities Program, the Consular Corps Association, The Philadelphia Trade Association, and probably others.

Look at it from the visitors' viewpoint. New York has larger colonies of foreign nationals than Philadelphia does, but New York is an expensive place to visit. Washington has dozens and dozens of embassies, but a visitor soon learns the last thing an embassy staff wants to see, is a citizen from home. So those places aren't really a typically American place to visit. Indiana is plenty American, but there isn't much to see there. So Philadelphia has many attractions, lots of history, it's as thoroughly American as a city can be, and all it needs is someone to open up and show it to you. Cleverly organized, the IVC has undoubtedly put the Philadelphia stamp on many foreign visitors, without their exactly recognizing they are being told This is America. If the State Department is shrewd in its assessment process, Philadelphia will in time be held in high esteem by the leaders of a lot of foreign nations.

In the spirit of announcing that Philadelphia is where you can find America, my own little daughter astonished me at a dinner party by telling the assembly the following story:" William Penn was nice to the Indians, so it was safe to land in Philadelphia. Pretty soon, so many people landed here they had to move West to settle down. And, folks, that's why the people to the North of us talk funny, and the people to the South of us talk funny -- but everybody else in America talks like Philadelphia!"

The Last Will and Testament of

William Shakspere

"During the winter of 1616, Shakespeare summoned his lawyer Francis Collins, who a decade earlier had drawn up the indentures for the Stratford tithes transaction, to execute his last will and testament. Apparently, this event took place in January, for when Collins was called upon to revise the document some weeks later, he (or his clerk) inadvertently wrote January instead of March, copying the word from the earlier draft. Revisions were necessitated by the marriage of [his daughter], Judith... The lawyer came on 25 March. A new first page was required, and numerous substitutions and additions in the second and third pages, although it is impossible to say how many changes were made in March and how many currently came in January. Collins never got round to having a fair copy of the will made, probably because of haste occasioned by the seriousness of the testator's condition, though this attorney had a way of allowing much-corrected draft wills to stand" (@ Schoenbaum 242-6).

Words which were lined-out in the original but which are still legible are indicated by [brackets]. Words which were added interlinearly are indicated by italic text. The word "Item" is given in the bold text to aid reading and is not so written in the document.

From the first line of Shakspere's will

In the name of God Amen I William Shakespeare, of Stratford upon Avon in the country of Warr., gent., in perfect health and memory, God be praised, do make and ordain this my last will and testament in manner and form following, that is to say, first, I commend my soul into the hands of God my Creator, hoping and assuredly believing, through the only merits, of Jesus Christ my Saviour, to be made partaker of life everlasting, and my body to the earth whereof it is made. Item, I give and bequeath unto my [son and] daughter Judith one hundred and fifty pounds of lawful English money, to be paid unto her in the manner and form following, that is to say, one hundred pounds in discharge of her marriage portion within one year after my decease, with consideration after the rate of two shillings in the pound for so long time as the same shall be unpaid unto her after my decease, and the fifty pounds residue thereof upon her surrendering of, or giving of such sufficient security as the overseers of this my will shall like of, to surrender or grant all her estate and right that shall descend or come unto her after my decease, or that she now hath, of, in, or to, one copyhold tenement, with appurtenances, lying and being in Stratford upon Avon aforesaid in the said country of Warr., being parcel or holder of the manor of Rowington, unto my daughter Susanna Hall and her heirs forever. Item, I give and bequeath unto my saied daughter Judith one hundred and fyftie poundes more, if shee or anie issue of her bodie by lyvinge att thend of three yeares next ensueing the daie of the date of this my will, during which tyme my executours are to paie her consideracion from my deceas according to the rate aforesaied; and if she dyes within the said term without issue of her body, then my will us, and I doe give and bequeath one hundred poundes thereof to my niece Elizabeth Hall, and the fifty poundes to be set fourth by my executours during the life of my sister Johane Harte, and the use and profit thereof coming shall be paid to my said sister Jone, and after her decease the saied l.li.12 shall remain amongst the children of my said sister, equally to be divided amongst them; but if my said daughter Judith be living at the end of the said three years, or any use of her body, then my will is, and so I devise and bequeath the said hundred and fifty poundes to be set our by my executors and overseers for the best benefit of her and her issue, and the stock not to be paid unto her so long as she shall be married and covert baron [by my executours and overseers]; but my will is, that she shall have the consideracion yearly paied unto her during her life, and, after her decease the said stock and consideracion to be paid to her children, if she has any, and if not, to her executours or assignes, she living the said term after my decease. Provided that if such husband as she shall at the end of the said three years be married unto, or at any after, do sufficiently assure unto her and tissue of her body lands answerable to the portion by this my will given unto her, and to be adjudged so by my executors and overseers, then my will is, that the said cl.li.13 shall be paid to such husband as shall make such assurance, to his own use. Item, I give and bequeath unto my said sister Jone xx.li. and all my wearing apparel, to be paid and delivered within one year after my decease; and I doe will and devise unto her the house with appurtenances in Stratford, wherein she dwelleth, for her natural life, under the yearly rent of xij.d. Item, I give and bequeath

Shakspere's 1st signature

unto her three sonnes, William Harte, ---- Hart, and Michaell Harte, five pounds apiece, to be paid within one year after my decease [to be sett out for her within one year after my decease by my executors, with advice and direction of my overseers, for her best profit, until her marriage, and then the same with the increase thereof to be paid unto her]. Item, I give and bequeath unto [her] the said Elizabeth Hall, all my plate, except my broad silver and gilt bole, that I now have at the date of this my will. Item, I give and bequeath unto the poor of Stratford aforesaid ten pounds; to Mr. Thomas Combe my sword; to Thomas Russell esquire five pounds; and to Frauncis Collins, of the borough of War. in the county of Warr. gentleman, thirteen pounds, six shillings, and eight pence, to be paid within one year after my decease. Item, I give and bequeath to [Mr. Richard Tyler thelder] Hamlett Sadler xxvj.8. viij.d. to buy him a ring; to William Raynoldes gent., xxvj.8. viij.d. to buy him a ring; to my dogs on William Walker xx8. in gold; to Anthony Nashe gent. xxvj.8. viij.d. [in gold]; and to my fellows John Hemynges, Richard Burbage, and Henry Cundell, xxvj.8. viij.d. a piece to buy them rings, Item, I give, will, bequeath, and devise, unto my daughter Susanna Hall, for better enabling of her to perform this my will, and towards the performance thereof, all that capital messuage or tenement with appurtenances, in Stratford aforesaid, called the New Place, wherein I now dwell, and two messuages or tenements with appurtenances, situate, lying, and being in Henley street, within the borough of Stratford aforesaid; and all my barns, stables, orchards, gardens, lands, tenements, and hereditaments, whatsoever, situated, lying, and being, or to be had, received, perceived, or taken, within the towns, hamlets, villages, fields, and grounds, of Stratford upon Avon, Old Stratford, Bishopton, and Welcome, or in any of them in the said counties of Warr. And also all that messuage or tenemente with appurtenaunces, wherein one John Robinson dwelleth, situate, lying and being, in the Balckfriers in London, nere the Wardrobe; and all my other lands, tenementes, and hereditamentes whatsoever, To have and to hold all and singuler the said premisses, with their appurtenaunces, unto the said Susanna Hall, for and during the term of her natural life, and after her decease, to the first son of her body lawfully issueing, and to the heires males of the body of the said first son lawfully issueing; and for defalt of such issue, to the second son of her body, lawfully issueing, and to the heires males of the body of the said second son lawfully issueing; and for default of such heires, to the third son of the body of the saied Susanna lawfullie yssueing, and of the heires males of the bodie of the said third son lawfully issueing; and for defalt of such issue, the same to be and remaine to the fourth [son], ffyfth, sixte, and seaventh sonnes of her bodie lawfullie issueing, one after another, and to the heires

Shakspere's 2nd signature

males of the bodies of the said fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh sonnes lawfully issuing, in such manner as it is before limited to be and remain to the first, second, and third sons of her body, and to their heirs males; and for default of such issue, the said premises to be and remain to my said niece Hall, and the heir males of her body lawfully issuing; and for default of such issue, to my daughter Judith, and the heirs males of her body lawfully issuing; and for default of such issue, to the right heirs of me the said William Shakespeare forever. Item, I give unto my wife my second best bed with the furniture, Item, I give and bequeath to my said daughter Judith my broad silver gilt bole. All the rest of my goods, chattels, leases, plate, jewels, and household stuff whatsoever, after my debts and legacies paid, and my funeral expenses discharged, I give, devise, and bequeath to my son in law, John Hall gent., and my daughter Susanna, his wife, whom I ordain and make executors of this my last will and testament. And I do entreat and appoint the said Thomas Russell Esquire and Frauncis Collins gent. to be overseers hereof, and do revoke all former wills, and publish this to be my last will and testament. In witness whereof I have hereunto put my [seale] hand, the date and year first above written.

Witnes to the publishing

hereof Fra: Collyns

Julius Shawe

John Robinson

Hamnet Sadler

Robert Whattcott

Shakspere's final signature, 'By me ...'

|

|

Father Divine House

|

While prosperous people, on deciding to enter a retirement community, are often heard to say they are tired of managing a big house, it can also be noticed that people who get the foreign travel bug usually drift around to see the palaces, castles, and estates of kings and emperors. The king's bathroom plumbing is a stop on most tours. Places like Buckingham Palace, the Vatican, the Temples of Karnak, Fortresses of Mogul Conquerors of India, or similar places in Cambodia, are all vast looming piles of stone dedicated to the memory of departed leaders who Had it All. That's probably all you need know, to understand that Americans who have it all tend to build huge show places, too. A great many do discover the castles to become just too much bother. Safe protection and privacy are somewhat separate issues, reasons given for putting up with a big place past the time the thrill has worn off. Perhaps such jaded feelings appear at the end of the wealth cycle. Nevertheless with enough affluence, if you had unlimited money and inclination, where around Philadelphia would you put a dream palace, one built for a modern Maharajah? Answer: close to Conshohocken.

|

|

The Philadelphia Country Club

|

The Schuylkill takes a sharp bend at Conshohocken because it flows around a big cliff on the west side of the river. It was there the White Steel Company built the first wire suspension bridge in the world, as distinguished from cable (twisted wire) suspension bridges invented by Roebling at Trenton. The bridge was swept away by a flood, the steel mill replaced by the Alan J. Wood Steel Company. Alan Wood prospered mightily, and built his mansion ("Woodmont") on 75 acres on the top of the big rock on the west side of the Schuylkill, in such a way he could watch the smoke rising from his factory down below at the foot of the cliff. The Philadelphia Country Club is across the road from Alan Wood's mansion, with fairways clinging to the cliffs, a Gun Club for trap shooters who want to aim away from houses and toward mountainsides, and a cliff-top road leading straight for Gladwyne between dozens of mansions with five-acre lots. Down the hill, however, rocky projections force the road to funnel into a winding crooked road which ends up near the filling stations of Conshohocken, passing ancient farm structures on the way. Railroads and expressways tend to fill the valley, the old White bridge is gone, and two distinct cultures are within a few hundred oblivious yards of each other. To the west stretches the Main Line, now filled with houses almost as large as the mansion, but air-conditioned and filled with other modern amenities. Seventy acres of a lawn is nice, but it's a lot of grass to cut.

The Alan Wood Steel Company had a hard time in 1929, recovered somewhat after World War II, and then declined to the point where Lukens and Phoenix Steel took over. And then Indians from India took over the lot, forming part of the largest steel complex in the world, now headquartered abroad. In 1952, one of Father Divine's religious followers named John Devoute gave Father the Wood mansion; which then became the new headquarters of his religious sect. He died in 1965 but Mother Divine still lives there in stately and tasteful semi-seclusion. The grounds of the estate are beautifully tended by various of the twenty-five attendants of Mother. Father's mausoleum is near the house.

|

|

Father and Mother Divine

|

The house itself is patterned after Biltmore in Asheville, NC, although perhaps only a quarter as large. Just inside its portecachier, the oak-paneled living room has a ceiling 45 feet high, and many oriental rugs. There is a music room, off to the side of which is Father's former office, bearing a strong resemblance to the Oval Office in the White House in Washington. As planned, the living room window looks down the valley to the site of the old steel mills, although when the trees are leafed out it may be difficult to see. The dining table probably seats forty people, although the paneled dining room was fitted with electronics and used to broadcast sermons to religious adherents across the country. In the living room are testimonies to the many who seemed to rise from the dead, or who had their blinded sight restored, or who were crippled but enabled to walk. The attendants take visitors on tours, but Mother Divine likes to meet them, coming down the sweeping staircase without noticeably showing her age. The greeting of "Peace" replaces the usual "hello" and "goodbye".

At one time, the Religion housed a large number of single women in several hotels, and the invested proceeds of their work as domestics still supports the Religion. The religion frowned on gambling, drinking, smoking, and sex. However, celibacy inevitably leads to a decline of numbers, particularly evident since the death of the founder.

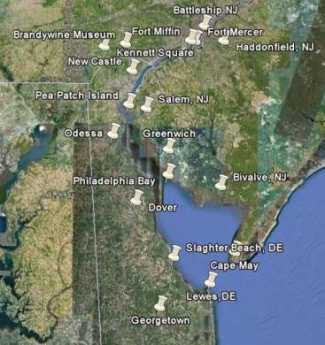

Originally the "lower counties" of Pennsylvania, and thus one of three Quaker colonies founded by William Penn, Delaware has developed its own set of traditions and history.

Originally the "lower counties" of Pennsylvania, and thus one of three Quaker colonies founded by William Penn, Delaware has developed its own set of traditions and history. Start in Philadelphia, take two days to tour around Delaware Bay. Down the New Jersey side to Cape May, ferry over to Lewes, tour up to Dover and New Castle, visit Winterthur, Longwood Gardens, Brandywine Battlefield and art museum, then back to Philadelphia. Try it!

Start in Philadelphia, take two days to tour around Delaware Bay. Down the New Jersey side to Cape May, ferry over to Lewes, tour up to Dover and New Castle, visit Winterthur, Longwood Gardens, Brandywine Battlefield and art museum, then back to Philadelphia. Try it! Millions of eye patients have been asked to read the passage from Franklin's autobiography, "I walked up Market Street, etc." which is commonly printed on eye-test cards. Here's your chance to do it.

Millions of eye patients have been asked to read the passage from Franklin's autobiography, "I walked up Market Street, etc." which is commonly printed on eye-test cards. Here's your chance to do it. In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions.

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions. Grievances provoking the American Revolutionary War left many Philadelphians unprovoked. Loyalists often fled to Canada, especially Kingston, Ontario. Decades later the flow of dissidents reversed, Canadian anti-royalists taking refuge south of the border.

Grievances provoking the American Revolutionary War left many Philadelphians unprovoked. Loyalists often fled to Canada, especially Kingston, Ontario. Decades later the flow of dissidents reversed, Canadian anti-royalists taking refuge south of the border.