3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Montgomery and Bucks Counties

The Philadelphia metropolitan region has five Pennsylvania counties, four New Jersey counties, one northern county in the state of Delaware. Here are the four Pennsylvania suburban ones.

The Philadelphia metropolitan region.

The Philadelphia metropolitan region.

A Woman's Work

|

| Feminism |

Whatever the gains and losses of the Industrial Revolution, reproductive need endures. Feminists who proclaim the advice to their sisters, "Have a baby; just don't have two." ignore some pretty simple arithmetic about population growth. What's perhaps worse, they fail to notice conflict with the goal of marrying rich. Rich men can afford a lot of things, but most of them can't afford a working wife. There's a fantasy in soap opera about meeting a fabulously rich man, one who owns motorboats and horses. How glamorous to be swept up by such a paragon; after all, every American hope to get rich.

|

| Big House |

, In fact, it takes training to run a big house, organize big parties, cope with artisans and servants, facilitate the complicated diplomacy of business and political affairs. A rich man expects his wife to run a big establishment, facilitate a complicated social life with those horses, sailboats and extensive travel. And she better maintains her personal glamor, too, because there are lots of younger women who toy with the idea of grabbing him in a weak moment. So even a fun time at the dress shops and hairdressers is obligatory. A man in an exalted position can't afford to have a wife who is employed in some dumb profession; the money she earns is a nuisance.

|

| Finishing School |

So that brings us to colleges and Quakers. A handful of elite women's colleges once tried to accommodate the finishing school with career preparation for blue-stocking women. The student could choose which path to follow but until recently finishing school was predominant, and comparatively few chose to be spinsters. Bryn Mawr College quickly grew to be the most prestigious college in the Philadelphia area, since both the finishing school and the bluestocking career had the needs of the upper class in mind. Quakers don't admit to an upper class but look at their colleges. Haverford was for Quaker males, Bryn Mawr for Quaker women, and Swarthmore for Quakers who fancied co-education. It was a nice arrangement, with Quaker students almost always in the minority, the rest either upper-class (read Katherine Hepburn) or brilliant scholarship students. Bryn Mawr was a little sniffy about the farm-boys at Haverford and the engineering nerds at Swarthmore. Much of that was an adolescent pose, but it created quite a rearrangement when Haverford went co-ed.

|

| Haverford College |

Almost overnight, women college applicants declared a preference for going to Haverford if there was a choice. Within a few years, Haverford students became 57% female, and Bryn Mawr suffered a decline in average aptitude scores. Why ever would girls prefer Haverford to Bryn Mawr? Indeed, if Haverford was headed in the direction of an all-female student body, Bryn Mawr would seem to be the better woman's college to pick. Somewhere buried in this adolescent stampede is probably some television-inspired confusion between the life of a suburban housewife and the life of a rich man's wife, but there certainly is a big difference in attitude about two-career families. On the other hand, there are lots more opportunities for the upper middle class than the lower upper class, both in the number of available mates and in the fall-back opportunity to try to make it as a career woman. Rich men are no longer invariably upper class, nudged by their chums to be wary of career girls. Anyway, college freshmen are pretty malleable; Haverford is a little safer bet if you aren't entirely sure of yourself.

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

The Barnes Foundation: Comments on the Economics of Art (2)

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes' legacy included Jerome's Epistle to Paulinus from the Gutenberg Bible education centered on a notable collection of illustrative artworks, housed in a museum of his own general design for the purpose. He left a multi-million dollar endowment to support his rather detailed and, in the opinion of many, somewhat eccentric intentions. It was his money, however, so his word was final. The institution was fairly mature, having previously been in operation under his direct control for twenty-five years.

Since the Foundation trustees are now before the Orphans Court pleading for permission to modify Dr. Barnes' instructions in order to avoid financial collapse, skepticism is inevitable. Obviously, the successor trustees must explain their expenses. But quite a plausible case can be made that the true cause of this disaster is inherent in the huge windfall growth in value of the paintings. In short, growth in value of the fine art may have outstripped the growth of the resources set aside for maintenance.

|

| Johann Gutenberg, creator of mass produced books, died in poverty |

Let's make a benchmark of the Gutenberg Bible, where incomplete copies are currently selling for $100,000 a page and complete copies are estimated to be worth $100 million apiece. Dealers maintain the Gutenberg is increasing in value at 20% a year, but growth seems closer to 9% a year if you go back to 1951. What's really relevant here is the growth in cost to ensure, protect, dehumidify, display and make it available to scholars, if not the public. It seems safe to guess these maintenance costs have grown more rapidly than the investment growth of the endowment, which is surely closer to 4% than 20%. The imbalance is even greater if you remember that some investment income is spent every year, while the worth of the fine art just grows and grows. Regardless of the true numbers, if the cost of maintaining the art does grow even slightly faster than the endowment, the dilemma the Barnes is now facing will eventually face any museum. New sources of revenue, either from the government or from public admissions, eventually becomes necessary if the priceless art remains on display. It is displaying these things that cost money; burying them under an Aztec mound or a German salt mine shelters them from the problem. In the case of Alfred Barnes, it is not completely certain that he wanted them displayed.

There is also the issue of quirky fluctuations in the market for fine art. The 22 known perfect copies of Gutenberg, Bibles have been around for almost five hundred years, and it is safe to say their value is enduring. The 180 paintings by Renoir now owned by the Barnes may prove to be Gutenberg Bibles or they may prove to be a passing fad, but it is pretty hard to believe that one of them will always be worth two Gutenbergs. Since there is a pretty fair chance that we are currently seeing a value bubble in French Impressionist painting, it is questionably prudent to shipwreck the whole Barnes Foundation, the School, or Albert C. Barnes basic intent, by resisting the sale of even one of the more overpriced examples in the collection at the top of the market.

That's one side of it. Another consideration is that Barnes himself did considerable merger negotiation with other museums, and may have been unexpectedly killed in an auto accident before he turned over all his cards in that particular poker game. It's asking a lot of the poor judge to overturn the clear and largely unmistakable language of Barnes will in favor of theories about what Barnes was really really thinking when he wrote it. If the judge is feeling adventurous, it's probably more satisfying to all parties if he sets forth a new legal doctrine, reflecting the inevitable disparity between the cost of displaying fine art to the public, and providing a perpetual endowment to do so.

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

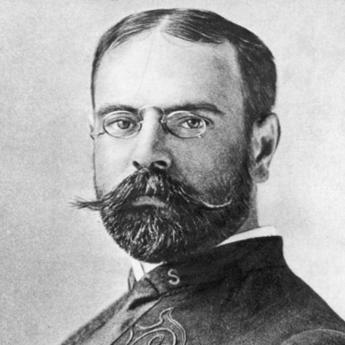

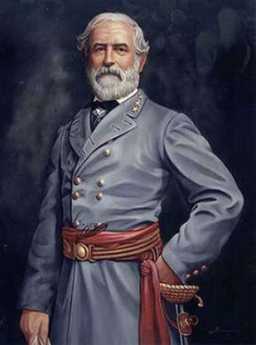

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

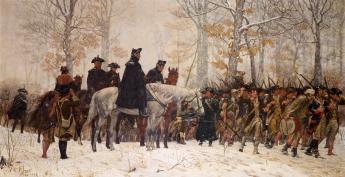

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

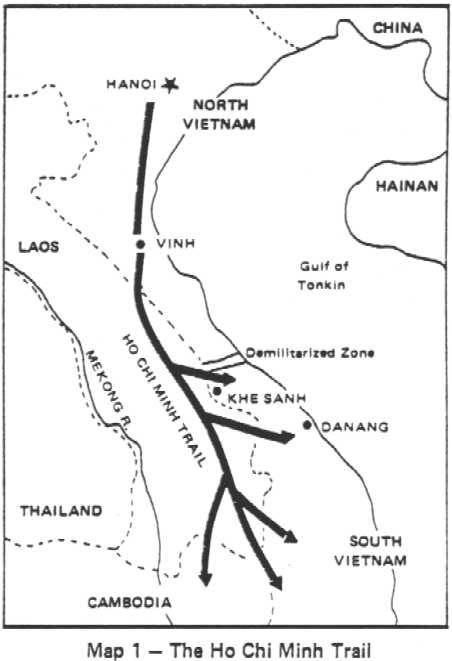

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

Main Line School Night

|

| Radnor |

There's a lot to learn from the Main Line School Night, and it isn't all taught in the classroom. The basic idea is life-long learning, going to school because it's fun. The idea started five or six decades ago in the Radnor, PA high school, that a lot of educated people wanted to become still more educated in topics of their own selection. No tests, please, and forget about academic credits; most of the students already have an excess of them. Forget about improving your income with advanced degrees; since this is Main Line Philadelphia, quite a few of the students already have all the income they could ever want. As related by the very low-key president of MLSN, David Hastings, the idea was an almost instant success. There were 1200 students enrolled for the second semester. They outgrew the original high school, and now teach courses in seven schools among 40 locations, to 14,000 students a year. There are 400 teachers in any given year, and the tuition charged is aimed at breaking even on the overhead. The academic world is inclined to say the courses lack rigor, by which is partly meant that if the students don't like the course, they walk out. Volleyball, yoga, and nutrition certainly do have a California sound, but computers, foreign languages, and science can be as difficult as you want to make them. If you get serious about contract bridge, you soon learn that isn't a simple child's game. Courses in wine tasting are given in the local senior citizens' retirement communities, but mostly not to the residents. It's not welcome to give that sort of course in a high school. To some extent, this continuing education is an exclusive social occasion, but then so is a course in diplomatic history at Princeton. Mr. Hastings tells of a group of sixteen ladies in a bridge course who have been coming for years, and have learned to close the course rolls by all sending in their checks on the day of registration. This is, after all, the Main Line where exclusionary techniques once learned are hard to forget. There are clouds on the horizon. In the past three years, enrollment has leveled off and declined a little. Almost no major corporation continues to be successful for more than seventy-five years, and many of the people running Main Line School Night are drawn from the Executive Service Corps. In retrospect, for example, the owners and editors of the Saturday Evening Post should have sold out and closed down, as soon as they learned the first million television sets had been sold. Perhaps the decline of enrollment of Main Line School Night reflects the advent of the Internet, or the cell phone, or some other new technological competitor. Or maybe the venture just got too big and successful to maintain its original format; perhaps it's outgrowing its blood supply. But anyway, they have 14,000 students and can be proud to be in a resting phase, when the rest of the city, or state, or country, hasn't even tried to get started on such a project.

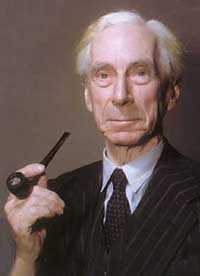

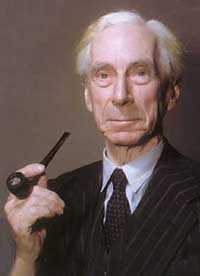

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Mind Your Manners

|

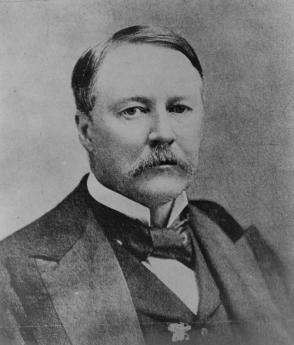

| Hoeffel |

In 1948 I was an intern at the old Pennsylvania Hospital, assigned for a while to the accident room. One of the accident-room duties of an intern is to sew up cuts and lacerations that arrive unexpectedly, but some lacerations can be out of your pay-grade and you have to call for help. On the evening in question, the victim had been so thoroughly slashed up that I had to call the chief surgical resident, Dr. Joseph Hoeffel. Hoeffel was big, tall, loud and self-assured, and swept majestically into the accident room with a little fellow trailing him. This follower seemed less than four feet tall but very quick and shifty. He didn't walk so much as he scuttled. Hoeffel bellowed, "Get out here!" and the gnome vanished.

While Joe was examining the laceration problem, the little fellow slipped through a different door to see what was going on. Most of us had the impression this guy might well be the one who inflicted the cuts, but in any event, he didn't belong where he was. "I told you to get out of here, and stay out," bellowed our surgeon. Again the scuttler scuttled away, while Hoeffel put on a sterile gown, sterile rubber gloves, mask, cap, and the whole ceremonial costume. He prepared to do his work, stamping out disease among the sick and injured, when a fist started at the floor. The little guy had slipped into the operating area once more, and soon the fist on the floor quickly flew in a wide arc, ending up on Hoeffel's jaw.

Hoeffel tumbled head over heels across the room, ending up in a corner. I don't think he was knocked out, but he was certainly dazed. The nurses called the police, who made a tumult of their own arriving to do battle. But the little fellow was gone, never to be seen again.

Fifty years later, I had occasion to preside over a meeting of the Right Angle Club, where

Hoeffel's son, the former congressman and current deputy member of the Pennsylvania Governor's cabinet, was the featured speaker. He looked remarkably like his father. I had to wonder if his father's lesson in diplomacy had made any notable effect on his progeny.

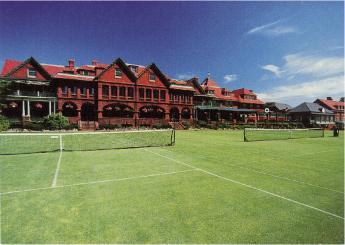

Lawn Tennis at the Cricket Club

|

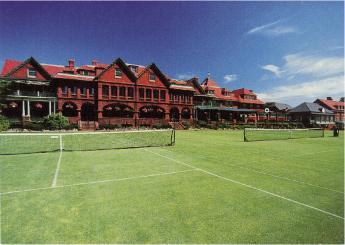

| Merion Cricket Club |

Lawn tennis isn't terribly ancient, having originated in England around 1880 as a variation of badminton which was brought back from India during the days of the British Empire. As the name suggests, it was originally played exclusively on grass courts, which proved hard to maintain. It was supplanted for a while by clay courts, and more recently by hard and artificial surfaces. Lawn tennis on lawns has largely become a game for the rich because of the cost and difficulty of maintaining a playable surface in hot weather.

If you wander into the Merion Cricket Club you'll find lawn tennis in the grand style, viewed from luncheon tables under a roofed porch. The long relatively narrow porch is right up against the grass courts, but it's also sort of a Peacock alley where well-groomed young ladies show their stuff, and everybody at the tables wishes to seem to know everyone else. There are times when the athletic entertainment becomes cricket out there on the field beyond the porch, but a larger proportion of the lunchers turn their backs on the field during that season than when exciting tennis championships are reaching the finals.

|

| "Lawn" Tennis |

In addition to being more expensive to maintain the courts, tennis on the grass is a different game from tennis on a hard surface, like clay or asphalt. The ball tends to skid when it hits the grass, so it is more effective to volley it before it hits or before it takes much of a bounce. The bounce tends to be more nearly straight up, while on harder surfaces the ball bounces at a low angle. Either way, the consequence is a tendency for a faster game on grass. The players run harder to get the ball at the bounce, and the advantage goes to those who serve hard and return the ball hard -- and fast.

|

| Cary Grant and Kathryn Hepburn |

The rather special nature of the game adds to the up-scale atmosphere. And makes it just as attractive for the Kitty Foyles at the tables, as for the Kathryn Hepburns, both of whom have their own attractions for the Cary Grants. The parking lot is also a good place to form an opinion about the latest in high-priced autos.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1494.htm

Potts

Rebecca Potts used to say there were three towns in Pennsylvania named after her family -- Pottstown, Pottsville,

|

| Pottsville biennial |

and Chambersburg. Becky never designed to explain whether Chambersburg was just a joke or whether her very extensive family really had connections in Chambersburg. It's possible either way; there were certainly Potts inValley Forge where Washington's Headquarters, which everyone visits, had been home to Isaac Potts, the third generation of Dutchmen named Potts to live there. Isaac ran a grist mill, the others mostly were ironmasters. The family seat in Pottstown was named Pottsgrove, still open for visitors. Holland Dutch they may have been, but Pottsgrove architecture is definitely of the Welsh style.

|

| Pottsville Coal |

Pottsville, much further up in the anthracite region, became notable through the novels of John O'Hara, a native son. For a whole generation, just about everybody in Pottsville was uneasy that O'Hara would confirm just who certain characters in his moderately raunchy novels represented in real life. Pottsville's main business for a century was extracting coal for the Girard Estate, which had its coal-mining headquarters in the town, based on Stephen Girard's shrewd purchase of nearly all of Schuylkill County.

The broad sweeping view from the interstate highway going north from Valley Forge makes it easy to see how Pottstown was created by the upheaval of a mountain ridge, which split open to let the Schuylkill River wind through. Pottstown is a water gap. The huge cooling towers of The Limerick nuclear power plant dominate one side of the river cliff and can be seen for miles. The cliff on the other side of the river, behind which hides the town of Pottstown, used to shelter the Wright aircraft factory, much of which was underground. That gave it a railroad (The Reading RR) and ready access to the river, plus privacy from the land side. Down to the right a mile is the Pottstown Hospital, on the edge of town, quite near the campus of the famous Hill School, fierce competitors of the Lawrenceville School in sports. Just about everything in this area is on top of some kind of hill.

Just back of the hospital, seemingly on the grounds of it, rises a peculiar steel tower, which the local workmen report is a sending station for cellular telephones. However, one of the doctors of the hospital relates a somewhat different history. He says he was once called on a medical emergency, told to ring the elevator at the little house beside the steel antenna, and travel down, down, into secret depths. He found himself in the headquarters of the Northeastern Air Defense Command, which was certainly hidden in an ideal place if the story has any truth to it. Unfortunately, that story-teller was a famous cocktail-party raconteur whose wild tales were never to be taken completely seriously. For many years, the hospital on a cliff was surrounded by corn fields, and it is certainly true you could look out the windows at a sea of corn, never suspecting you were very close to a railroad and a river, quite possibly right over an underground aircraft factory. Someday it may be possible to find out the truth of these tales of the Dutch country.

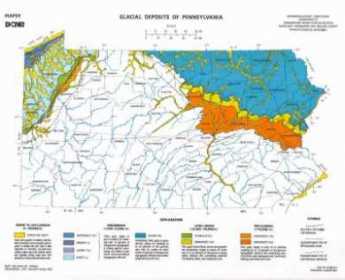

During the American Revolution, the British blockaded the coast and landed troops on the main coastal highways. The Americans responded in a quite natural way by building an inland north-south forest trail, sort of on the order of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Pottstown was one natural stop on this trail, which tended to intersect with many roads coming up along the banks of the coastal rivers. In one very famous episode, wagon loads of Philadelphia Quakers were arrested and taken up the Schuylkill to Pottstown, then south to internment at Winchester, Virginia. They weren't exactly Tories, but they certainly were not sympathetic to revolutions. One of the most famous of these semi-prisoners was Israel Pemberton, one of the leaders of the Quaker colony. He later reported he was treated well, but onlookers in Pottstown described him as being thoroughly abused.

Pottstown had a century of prosperity during the industrial age, then declined and decayed. In recent years. The interstate highway has brought a migration of exurbanites whose taste in architecture tends toward McMansions. Let's hope they can acquire a dose of local history, starting a new historical revival of a town with great potential, considerable past glory, and a wonderful natural setting.

Radioactive River Bend

|

| Gold Cert |

A mile or two south of Pottstown, the Schuylkill River encounters a rocky ridge several hundred feet high and makes a bend around it. The first Treasurer of the United States, Michael Hillegas, built a colonial mansion on the point of the bend, and it has been lovingly restored and preserved by a noted Philadelphia surgeon and his wife. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under the Constitution, has his picture on the modern version of a ten-dollar bill. So it is appropriate that Hillegas, the first Treasurer under the Articles of Confederation, had his picture on many versions of a ten-dollar gold note, back in the days when the American dollar was as good as gold. River Bend Farm is not only colonial, charming and maintained in mint condition, but it is also tucked away between the bend in the river and the high ridge to one side, giving it seclusion and privacy.

A high ridge near a river is unfortunately also an ideal place to build a nuclear power plant, and that's where the Limerick plant now looms up, glowing at night, occasionally making faint humming noises. There's a limited-access highway from Philadelphia to Reading which swoops up the valley, and the two high cooling towers of Limerick dominate the landscape for twenty miles. Because of the river bend, you aim straight for those towers for a long time before you swerve off, and the view is much like that from the bomber cockpit of the final scene in the movie "Dr. Strangelove". It gets your attention harmlessly, but it's hard to ignore. In spite of all sorts of official reassurance, everybody knows about Three-Mile Island, and Chernobyl, but few people emphasize there has never been a single injury from an American nuclear plant.

So, in 1981, everybody was ready to go into orbit when a worker named Watrus showed up for work at the nuclear plant and set off all manner of clanging alarms from radioactivity detectors. Panic and pandemonium for weeks, until a remarkable phenomenon was discovered. Watrus wasn't radioactive from the nuclear plant at all, but from having his work clothes laundered in his own basement. It slowly developed that radon gas seeps through the ground in many places in the United States, particularly over rocky ground. The gas then rises into the basement of houses and gets trapped. The more tightly the storm windows are applied and the more carefully sealed the seams of the house, the harder it is for the radon to escape. The Pennsylvania Dutchmen who live around Limerick are a little skeptical of this story and are not inclined to live any closer to the power plant that they have to. They are just as much in favor of oil self-sufficiency as anyone else, but still, no one likes being close to it.

The big winners from all this confusion are the people with radiation detectors, who go around the country testing people's basements for radon, for a fee. But unless you are willing to go live on the Sahara Desert, it isn't easy to see where you are going to go to avoid radon.

Lansdowne

|

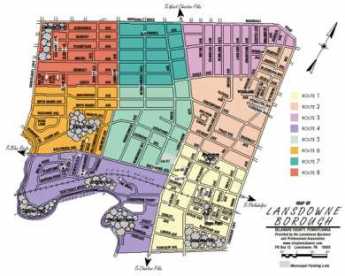

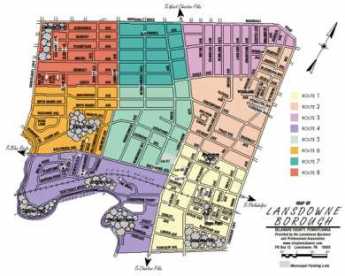

| Lansdowne Map |

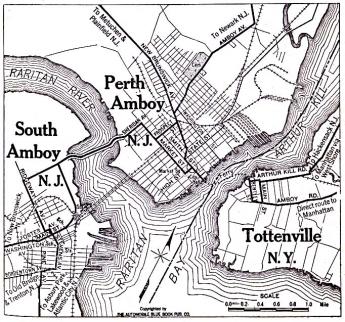

The Granville, or Lansdowne, the family had so many members important in English history, that the Lansdowne name adorns countless schools, boroughs, colleges, museums and other monuments around the former British empire. It would require undue effort to sort out just why each memorial is named after just which member of the family. In the Philadelphia region, Lansdowne is the name of a small borough in Delaware County,

|

| Lansdale |

often annoyingly confused with Lansdale, a small borough in Montgomery County. However, it really seems more appropriate to focus reverence on the Lansdowne mansion, which from 1773 to 1795 was the home in now Fairmount Park of the last colonial Governor. That would have been John Penn, who was one of several Penns who still shared the Proprietorship until 1789, and who shared in the miserly payment which the Legislature of the new Commonwealth made as compensation for expropriating twenty-five million acres of their property. The French Revolution was going on at that time, so there were probably some patriots who would scoff that John Penn was lucky not to be guillotined.

The Penn family could see the Revolution coming, and like everyone else was uncertain who would win. Real decision-making for the Proprietorship rested with Thomas Penn in London, a close friend of the King and his ministers. The strategy employed in this difficult situation was to surrender the right to govern the colony conferred by its original charter and to become mere real estate owners with John their local representative pledging local allegiance. That might have worked for a while, until General Howe's troops captured Philadelphia. Soldiers were dispatched to Lansdowne to tell John Penn he was under detention, to reduce his potential utility to the occupying army.

|

| Horticultural Hall |

As matters eventually worked out, some of the Penn descendants remained fairly wealthy after the Revolution, especially those whose wives had inherited substantial assets from other sources. But some were severely impoverished. The stately Georgian mansion burned down in 1854, and the site was then occupied by the Horticultural Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Perhaps because of misplaced patriotic fervor, it is now difficult to find a picture of Lansdowne.

The elegance of the place, on 140 acres, is suggested by the fact that William Bingham the richest man in America at the time, apparently acquired it from James Greenleaf the partner of Robert Morris, and the nephew by marriage of John Penn, who acquired it from Penn's estate but probably had to give it up in the financial disasters of Morris and his firm. Lansdowne was still a grand manner when it was briefly acquired by Joseph Bonaparte, the former King of Spain. In view of the fact that Bingham had provided President Jefferson with the gold to finance the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte, and earlier had practically forced the Congress to call off an impending war with France, there was likely a connection here.

And to some extent, the ill-treatment which John Penn received from the Pennsylvania legislature (roughly fifteen cents an acre) in the Divestment Act of 1779 can possibly be traced to the unrelenting hatred by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania's icon. History does not tell us what made these two former friends fall out in 1754, sufficient to make Franklin willing to spend years in London trying to get the colony away from the Penns. The feeling was surely mutual. When John Penn was offered the patronship of the American Philosophical Society, he declined, just because Franklin was its president. In retrospect, that sounds unwise.

Laundered Money

|

| Judge Edwin O. Lewis |

Judge Edwin O. Lewis finally got his way, the Pennsylvania State Government acquired four blocks of Chestnut Street stretching to the East of Independence Hall, and the Federal Government acquired four blocks stretching to the North. Judge Lewis was determined that a real revival of historic Philadelphia required the clearance of a lot of lands. Those who heard him describe it will remember the emphasis, "It must be BIG if it is to serve its purpose."

The open land is rapidly filling in but for a time the movers and shaker of this town had to scratch a little to find something to put there. That's fundamentally why the historic district has a Mint, a Federal Reserve, a Court Houses, a Jail, and a big Federal Building to house various local offices of the landlord, the federal government. It's where you go to visit your congressman, or to renew your passport, or to argue with the Internal Revenue Service. If you have certain kinds of business, there's an office for the FBI and the U.S. Secret Service. The mission of the Secret Service is a little hard to explain with logic.

The Secret Service is a federal police organization, charged with protecting the President of the United States, and enforcing the laws against counterfeiting money. In unguarded moments, the Secret Service officers will tell you they only have one function: to guard three-dollar bills. The President only comes to town from time to time, but the mandate extends to the President's family, and to the extended family of official candidates for election to that office. So, there is usually always a certain amount of activity relating to running behind limousines with one hand on the fender, or poking around rooftops near the speaker's platform at Independence Hall, or talking apparently to a blank wall, using the microphones hidden in their ear canals. The rest of the time is taken up with counterfeiters, but even then the excitement is only occasional, depending on business.

A few years ago, the buzz around the office was that some very good, even exceptionally good, fake hundred dollar bills were in circulation in our neighborhood. The official stance of The Service is that all counterfeits are of very poor quality, easily detected and no threat to the conduct of trade. Unfortunately, some counterfeits are of very good quality, not easily detected, and when that happens, The Service is made to feel a strong sense of urgency by its employers. These particular hundred dollar fakes were of very good quality.

One evening, a call came in. Don't ask me who I am, don't ask me why I am calling. But I can tell you that a very large bag of hundred dollar wallpaper has just been tossed over the side of the Burlington Bristol Bridge, near the Southside on the Jersey end. Goodbye.

Very soon indeed, boats, divers, searchlights, ropes, and hooks discovered that it was true. A pillowcase stuffed with hundred dollar wallpaper of the highest quality was pulled out of the river. By the time the swag was located and spread out for inspection, it was clear that several million dollars were represented, but they were soaked through and through. Most of the jubilant crew were sent home at midnight, and two officers were detailed to count the money and turn it in by 7 AM. The strict rule about these things is that all of the money confiscated in a "raid" was to be counted to the last penny before it could be turned over to the day shift and the last officers could go home to bed. After an hour or so, it was clear that counting millions of dollars of soggy wet sticky paper was just not possible by the deadline. So, partly exhilarated by the successful treasure hunt, and partly exhausted by lack of sleep, the counters began to struggle with their problem. One of them had the idea: there was an all-night laundromat in Pennsauken. Why not put the bills in the automatic drier, so they could be more easily handled and counted? Away we go.

|

| Burlington Bristol Bridge |

At four in the morning, there aren't very many people in a public laundromat, but there was one. A little old lady was doing her wash in the first machine by the door. It was a long narrow place, and the two officers took their bag of soggy paper past the old lady, and down to the very last drying machine on the end. Stuffed the bills into the machine, slammed the door, and turned it on. Most people don't know what happens when you put counterfeit money in a drier, but what happens is they swell up and sort of explode with a terribly loud noise. The machine becomes unbalanced, and the vibration makes even more noise. The little old lady came to the back of the laundromat to see what was going on.

As soon as she got close, she could see hundred dollar bills plastered against the window, and that was all she stopped to see. She headed for the pay telephone near the front of the door. The secret Servicemen followed quickly with waving of hands and earnest explanations, but within minutes there were sirens and flashing lights on the roof of the Pennsauken Police car. Out came wallets and badges, everyone shouting at once, and then everything calmed down as the bewildered local cop was made to understand the huge social distance between a municipal night patrolman and Officers of the U.S. Secret Service. Now, he quickly became a participant in the great adventure and was delegated the job of finding something to do with armloads of (newly dried) counterfeit hundred dollar bills. He had an idea: the local supermarket was also open all night, and they carried plastic garbage bags for sale. Just the thing. But who was going to pay the supermarket for the bags? Immediately, everyone was thinking the same thing.

Fortunately for law and order, the one who first suggested the the obvious idea of passing one the counterfeits was the little old lady. At that, everyone came to his senses. Wouldn't do at all, quite unthinkable. The local cop was sent off for the bags, relying on his ability to persuade the supermarket clerk. And, yes, they did get the money all counted by 7 A.M.

Life On The River (3)

|

| Darth Mouth Castle |

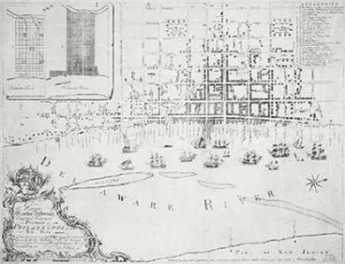

All over Europe the scene is repeated: a market town and seaport at the mouth of a river, with many miles of riverbank castles in the hinterland. The seaports had to be fortified against pirates, the hinterland against marauding brigands. But the two flows of commerce consisted of baronies upriver feeding the seaport, while secondarily their seaports carried on trade with nearby river-organized economies. From time to time, someone like Julius Caesar, Napoleon, Bismarck or Hitler would try to unify the various river economies, usually unsuccessfully. In fact, the same pattern was seen along the Pacific Coast of South America, until the Incas figured out how to go along the mountain ridge in the far interior, and then come down the rivers from the sparsely populated areas to the maritime settlements at the mouth of the river, whose defenses were planned for enemies from the sea. Philadelphia followed the commercial pattern, but without fortresses and castles.

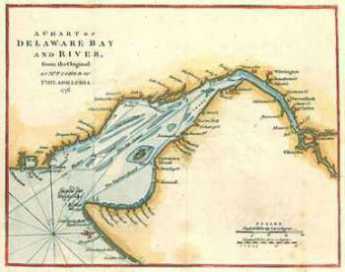

Because of the vagaries of King Charles II, and underneath that, because of marshes and their mosquito-borne diseases, the Delaware Bay was settled fairly late in colonial times -- and almost entirely by Quakers. The Dutch were interested in fur trading rather than settlement, the Dutch were anyway too few, their sovereign too indifferent, and William Penn took care of the Indians. So the English settlers had no one to fight except other Englishmen, once the French stab at Inca-like strategy was put down in 1753. After 1783, or perhaps 1812, the world finally left us alone. The Delaware Bay and River are essentially free of fortresses, Philadelphia has no castles. The peaceful sixty miles of upper Delaware Bay became lined with big farmhouses, or big Federalist and Victorian mansions. For a century, from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War, and even for a time after that, the history of this peaceful pond reads like a novel by Jane Austen.

As a playground for menfolk, it would be hard to improve on Victorian Delaware Bay. The river was full of fish, notably shad. In the fall, the migrating ducks and geese made for marvelous hunting. In the countryside behind the riverfront, houses were found all the sports having to do with horses; fox hunting, racing, horses shows. The kids could putter around in small sailboats, the adult sailors could sail a yacht to Europe if they wanted to. After John Fitch invented the Steamboat, it was possible to take a daily commute to the best male game of all -- trading, investing and gambling in the financial and commercial center of Philadelphia.

|

| Shad |

Marion Willis Rivinus and Katherine Hansel Biddle wrote a little book in 1973 called Lights Along the Delaware which tells the river story from the female point of view. The woman of the house was sort of the mayor of a little city, organizing the staff, supervising the garden, educating the children, planning the household, and organizing the dinners and social events. Educated and trained to the role, she knew what to do and enjoyed doing it. Jane Austen wrote the handbook. And while the menfolk were essential members of the cast of characters, women were the managing directors. The men were off with their horses, or sailboats, or fishing rods, or their faraway big-deal mergers and acquisitions. True, it was not a notably intellectual community, there was no Edith Wharton, Abigail Adams or Emily Dickinson. You might find some of that in Germantown, perhaps. The professions, law, and medicine, lured the more studious male members away from Society, but the international diplomatic circle was seen as the ideal career for any truly graceful graduates of this environment.

|

| Riverbank Railroad |

As the riverbank was gradually destroyed by railroads and expressways, only a few mansions like Andalusia remain in good repair. Curiously, what endures best are the clubs. The fishing club variously called the Fish House, the Castle, the Colony in Schuylkill, or the Schuylkill Fishing Company of the State in Schuylkill, has moved as many times as the name has changed. Started in 1732, it is the oldest continuously existing men's club in the world. It moved to the Delaware River from the Schuylkill when the Fairmount dam was built, and to its present location at Devon, the estate of William B. Chamberlain in 1937. New members do the cooking, cleaning, and serving, older members tell stories. When the river pollution is finally controlled, they may go back to catching the fish as well as cooking them. There's the Philadelphia Gun Club, which before 1877 was the Public Holiday Shooting Club of Riverton NJ. And then there's the Gloucester (NJ) Fox Hunt, which during the Revolution turned into First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry. After escorting George Washington to the battles of Boston Harbor, The Troop has been an active fighting unit of the National Guard (most recently in Bosnia) as well as a devoted center of male horsemanship between wars. The Farmer's Club, the Agricultural Society, and the Horticultural Society all reflect the rural interests that once predominated just behind the riverfront estates, still thriving aloof after 150 years of suburbia, exurbia and urban revival.

|

| Philadelphia Gun Club |

Although the riverfront industrial slums which destroyed the Philadelphia branch of Jane Austen's gracious living subculture are themselves declining and seem about to go away, it would take a real visionary to imagine how the Grand Life on the River will ever return. The banks of Delaware are much lower than the bank of the Hudson, for example. They make a great place to put high-speed rail lines and even higher speed interstate highways. The patrons of Hyde Park, West Point, and Poughkeepsie are much higher up a cliff and can overlook the river without much noticing an occasional whoosh. The mansions along Delaware have to look right at the tracks. Except for a few places like Bristol which have become isolated on the river side of the tracks and highway, it's not easy to see how you would get from here to there, or when.

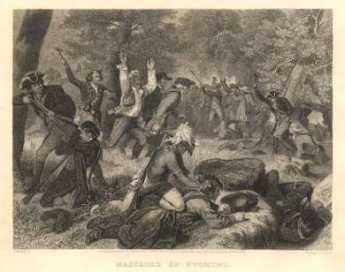

Litchfield County, Extended (1771-1775)

|

| Wilkes-Barre |

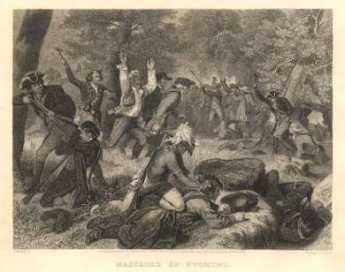

FOR four years, the Connecticut settlers considered the apparently peaceful Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania to be part of Litchfield County, Connecticut, and its main little town was called Westmoreland (now Wilkes-Barre, although it still has a Westmoreland Club). However, the high-living, non-Quaker sons of William Penn were ill content to let matters remain that way. Their response was to sell large tracts of land in the area, on condition the purchasers would do whatever fighting was needed to conquer and hold it. The main purchasers were Scotch-Irish from Lancaster County, and the main speculators were prominent Philadelphians with names like Francis, Tilghman, Shippen, Allen, Morris, and Biddle. This speculative land sale was to be the source of trouble for decades because it conflicted with titles to the same land issued by the Susquehanna Company.

The predictable trouble surfaced in 1775, with the Second Pennamite War. Under the command of a man named >Plunkett, 700 Pennsylvania soldiers marched to liberate Wyoming and were soundly defeated by the Connecticut soldiery under the command of Zebulon Butler. There might have been further fighting in this expanded war, except for the other eleven colonies applying great pressure on these two colonies fighting each other with potential jeopardy to the united rebellion against British rule. While the Penn family were definitely royalist in their sympathies, their colonial property put them in an awkward position with their Scotch-Irish allies, who were, in all colonies, the main leaders in the revolution. The effect was to isolate the Connecticut invaders, even though they were the victors in the fighting.

Slum Creation and Urban Sprawl

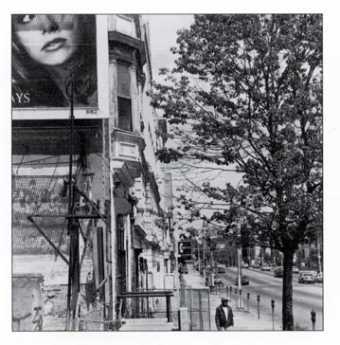

|

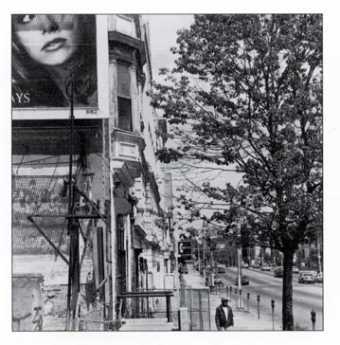

| North Philly |

Slum creation, while occasionally deliberate, is most typically caused by an area's abandonment by previous owners, at lower prices, to bargain hunters. When a large employer moves or closes, the employees seek work elsewhere and sell their houses for what they can get. When the influx of new ethnic groups threatens to weaken real estate prices, panic may be created that waiting too long to sell may find the property worthless; nobody wants to be the last one out the door. During the 20th Century, the driving force in Philadelphia was the flight to the suburbs by people who found a better value in suburban schools, shops, and neighborhoods. All of these processes create slums, almost invariably with a net loss of value in the community. Take a look at those deteriorating mansions on North Broad Street, where the Civil War millionaires used to live. In today's terms, they were once worth several million dollars apiece, but in today's real estate market, they are next to worthless. Value disappeared. The community as a whole is poorer than it was. From the Mayor's point of view, the area has lost its tax base.

|

| New Construction |

Of all these forces, the flight to the suburbs is probably the least destructive to the region, particularly if it is reasonably slow. Out in the suburbs, value is being created as cornfields turn into suburbia, and that added value must be set against the reduced value of the abandoned slum areas. Viewed from the Mayors' perspectives, however, we have a zero sum. The city loses its tax base, the suburbs gain, and local politics soon degenerate into warfare between the suburbs and the city. Not a nice situation, and it cries out for a new civic design. The city politicians have dreamed for a century of city-suburb consolidation, but Philadelphia tried that in 1850. It didn't cure the problem, and it may have created new problems. In any event, suburban politicians live and die on their anti-city rhetoric, and everybody's behavior in the Legislature deserves no kinder description than -- savage.

|

| Orange Station |

Because this issue has been the underlying theme of the Pennsylvania Legislature for two centuries, it repeatedly surfaces in ways that are surprising unless you understand the mechanics of suburban sprawl well enough to see the connection. For example, nowadays a real issue is the three-car family.

During the 19th Century, multi-acre estates spread out along the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad, with the coachman and horses taking plutocrats to the station. Smaller houses, for people who walked to the station, clustered nearby, but you didn't have to go very far from the station to find the gated estates. Suburban development spread out in linear and predictable fashion from the city, along the Main Line. The advent of the automobile freed commuters from the tyranny of railroad station orientation, and middle-class residents could flee the city to areas of the suburbs that were fairly far from the railroad and its stations. But not too far, because there was the problem of the lady of the house, who had to get to the stores. To free her up, the family had to have two cars in the garage. Suburban shopping malls helped her problem, somewhat, but the railroad station was still a magnet.

And then, the majority of married women became working wives, confronting the problem of kids getting to the confounded school. The highly questionable solution of giving the kids a collective car as soon as the oldest got a license, made the oldest kid proudly take the role the coachman used to have, and it caused a lot of teenage turmoil that need not be described here. The point to be stressed is that the three-car family sent home-building into cornfields that were not even close to the main road. Since land gets cheaper the further you get from the city, an economic incentive is created to enter uncongenial social environments, and adopt unexamined attitudes about the environment that are ultimately flatly contradictory.

When the kids leave home, the exurban pioneers no longer need the third car, and think about returning to city life. So far, however, they have been returning to Center City, not the residential neighborhoods they used to call home.

Founding Fish

|

| Potomac |

In 2002, John McPhee brought out a perfectly splendid book about fish and fishing history in this region, with particular emphasis on shad. He makes the whole topic remarkably interesting, but you have to be a little wistful about the way he demolished a splendid story of fish in Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War. The book is called The Founding Fish.

As everyone knows, George Washington and the Continental Army were starving and freezing at Valley Forge, a few miles up the Schuylkill, while Major Andre and the other British officers were cavorting downtown with the Tory ladies, grr. The story has long been told that things got to a desperate state at Valley Forge when, lo, the annual shad run was several weeks early and mountains of fish came roaring up the river to the excited shouts of the starving patriots and rescued the raggedy starving Continental Army. It would make a wonderful scene in a movie.

McPhee tells us that George Washington was in fact a shady merchant, having caught and pickled many barrels of shad coming up the Potomac River. The annual shad excitement was no news to him, and it seems quite possible he selected the campsite at Valley Forge with this spring event in mind. Shad was no news to the British, either; there are records of their trying to block off the Schuylkill with nets to prevent the fish from getting upriver to Valley Forge.

Unfortunately, a careful search of letters and records fails to record any shad run earlier than April that year. The rescue of song and story does not appear in contemporary documents. What's more, some unnecessarily diligent scholars have sifted through the garbage heaps of the encampment area, and have only found pig and sheep bones, no shad bones.

Those graduate students undoubtedly deserve to be awarded degrees for their work, especially the digging in garbage part. But nevertheless, it all does seem a pity to ruin a good story that way.

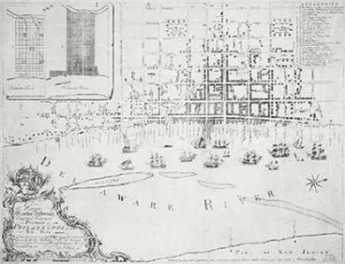

A Few Rooms of Your Own

|

| William Penn |

If William Penn could revisit Philadelphia today, he would surely feel disappointed that the Greene Country Towne still hasn't materialized. Even a century after Penn's real visits, Philadelphia at the time of the Revolutionary War still nestled East of Fifth Street. There have been many conjectures about this, perhaps fear of Indian attack, perhaps lack of firewood, desire to be near the port, perhaps a number of things. Let's examine whether it's just the nature of a successful city to organize itself the way it does.

Ancient Athens, for example, was a nice warm place without much rain, which possibly accounts for the miserable little hovels where people lived, contrasting with the magnificent Acropolis, Parthenon, Stoa and other public buildings. It has been speculated that the architecture created the social system, not the other way around; the same contrast between big stone temples and little wooden huts is also seen in the Mayan cities of Yucatan. Hong Kong certainly isn't poor, but it's built like that. Japan cannot claim that lack of land forces the citizens to live in tiny apartments. It's hard to say whether the lowly social state of Japanese women accounts for the contrast between where they live and where their husbands spend most of their time because it's just as easy to believe the proposed cause is really an effect.

The more you look around the world, the more you wonder if it isn't the American suburb that's out of step with the world. When they can afford it, hardly any of the world seems to want to live in the suburbs; their homes are seldom their castles. There's New York City, of course. New Yorkers seem to like living in high-rises.

An architect friend makes short work of construction economics as a driving feature. According to him, it is unduly expensive to live in a high-rise. Just a pointless ego trip. The cost per square foot of usable floor space just keeps going up as the building gets taller, requiring more elevator shafts, more elaborate HVAC. That's heating, ventilating and air conditioning. Everything has to be built with a derrick, the traffic congestion at the base is horrific, high winds can break the window glass. The list rapidly grows convincing. Why does anyone pay all that extra money to live high in the sky? Not my idea of something to do, says Cole Porter.

Notice there is a major difference between sleeping in the suburbs as they do in Japan, and sleeping in apartments right near the center of town, as they do in Budapest, Berlin, Prague, and Vienna. The Orientals are staying close to work for longer hours, while the Central Europeans are staying close to the cafes and theaters to which they flock the moment work is over. Just what to think of the Spanish siesta system isn't clear, but it seems to have the main effect of bringing people back into the center of the town at night. You can't live very far away from work if you have to commute twice a day.

The Lord only knows where everybody in New York is going every Friday night, with return traffic jams in the other direction on Sunday night. The weekly exodus suggests they don't really luxuriate in their penthouses or flock to their entertainment district on weekends; apparently, a cabin in the woods is beckoning. As, by contrast, the empty nesters in the suburbs eventually look around for retirement villages to live, repeating the endless complaint about the nuisance of maintaining a big house and garden. Pennsbury looks like a comfortable place to live, but even William Penn seems to have tired of it. One really does have to wonder whether a heart's desire in architecture all too frequently leads to heart's discontent in lifestyle. Philadelphia appears to be trying a new approach; the suburbs are moving back downtown.

We'll eventually see if it changes our character and lifestyle so somebody can write sociology books about it.

Merging Cities With Their Suburbs

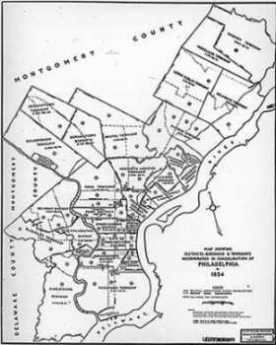

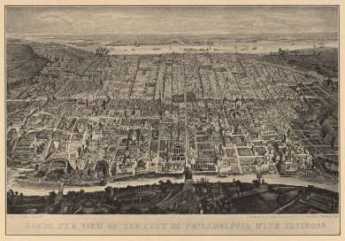

|

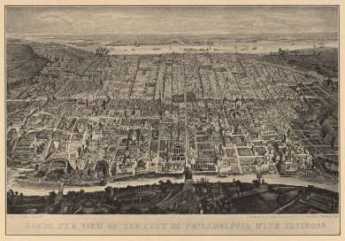

| Philadelphia 1854 |

When the City of Philadelphia turned into the County of Philadelphia (or vice versa) in 1854, the area had about 150,000 residents in 1850 but 500,000 in 1860. It qualified as one of the largest cities in America at the time, but what we today call middle-sized cities are about that same size. As a generalization, when a thriving American city approaches a size of about half a million, the business community often gets the idea that the city should expand its limits by annexing the neighboring districts. And, as a further generalization, the metropolitan newspapers are simply ecstatic about the idea of expanding their market reach, while the working classes of both the city and the region it proposes to swallow, are violently opposed. Since the business community typically feels that expansion would be good for business, labor unions are subdued. Leadership of the conservative middle-class rebellion is therefore generally led by the police and volunteer firemen, who are the most organized groups within the combative working class in a metropolitan region. Many citizens of all classes are of course quite indifferent about the matter. As history has turned out, only one such proposal in five will be successfully adopted, but it is almost unheard-of for a successful amalgamation to be reversed once it happens. In recent years, this general pattern has been followed in Indianapolis, Lexington, Jacksonville, Nashville, Baton Rouge, and Louisville. In countless other cities, the effort has been defeated by the voters.

It requires thriving prosperity for the business community to become politically dominant in a city, so the political context of these circuses amounts to a contest between the business "elite", often augmented by "carpet baggers from out of town" threatening comfortable lives within settled neighborhoods by merging them with culturally discordant residents in suburbs or countryside. On a political level, professional urban politicians favor expansion, because increasing the electorate generally makes it more expensive for an outsider to raise the funds to defeat them in an election. Exceptions to this rule occur when the two merging regions have different political parties in control, or when working-class city districts are so opposed that urban politicians fear to anger them. A symptom of this conflict for control of a city machine can be observed in the seemingly unrelated issue of a city charter with a "strong mayor" design. Cities with a strong city council generate greater ability to defeat the machine and are hence more reluctant to see mergers with suburbs. Nevertheless, the attraction which the business community can offer to the politicians is a larger tax base, although in the surrounding suburbs the dynamic is exactly the opposite. In the suburbs, it is the local businesses and professions who feel threatened, and who attempt to agitate the suburban politicians to protect their tax collections.

Although campaign rhetoric in these battles tends to exaggerate or distort the probable economic changes, academic studies find that the actual effect of city expansion is generally of modest subsequent growth, with modest increases in taxes. These effects seem comparatively weak since a metropolitan region is unlikely to produce a successful merger unless the economy is already growing fast enough to generate expansionism, and that vigor is likely to persist after the merger. These political uproars talk a great deal about economics, but in fact, the issue is primarily political. One commentator calls them "chess games pretending to be circuses", and the real force at work is usually an elaborate variation of gerrymandering. Urban minorities who usually vote Democrat can be swallowed up by suburban majorities who usually vote Republican. Or else a thwarted inner-city business community hopes to replace the urban machine with a more favorable suburban set of attitudes. There is seldom a uniform political gradient as the city border is approached from either side, so the chess game takes these patchwork population variants into detailed consideration. It is often argued that crossing a political boundary is unworkable, but since the thriving city of Atlanta is located in two different counties, that must not be a dispositive argument.

In their most elemental form, these expansion efforts have to do with political boundaries. It is therefore not surprising that the people most concerned are politicians. The battle cry is often to create a city without suburbs; failure to act leads to suburbs without a city. In fact, the underlying agendas are much more prosaic.

Country Auction Modernized

Only a decade ago, the Quakertown exit of the Pennsylvania Turnpike made possible a quick trip from the city to the country, letting you off in the cornfields between Sumneytown and Lansdale. Today, the rush hour traffic is as bad as anywhere else, even on the four-lane express highway known as Forty Foot Road. A comfortable two-lane highway would be about forty feet wide, so presumably, the name denotes what was once a modern miracle of a two-lane highway, in this case until quite recently. It's all built up for miles, but almost all the commercial buildings are new. Exurban sprawl has positively lurched across the landscape, making prosperous people rich, and poor people prosperous. It won't be long before the housing subdivisions demand traffic signals to protect the school children, speed limits to reduce the collisions by teenagers, and other things destined to bring high-speed travel to a crawl, all day long. When that happens, it won't be called farm country anymore.

|

| Alderfer Auction Company |