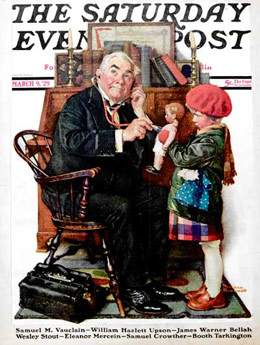

2 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Downtown

A discussion about downtown area in Philadelphia and connections from today with its historical past.

...

...

Friends of Boyd

|

| Boyd Theatre |

Howard B. Haas a lawyer, and Shawn Evans an architect, are captains of a team trying to "save" the old Boyd Theatre at 1908 Chestnut Street. Since Clear Channel, the present owner has invested $13million in the property, and the preservationists agree that renovation of the movie palace to all its former glory would cost between $20million and $30million more, it's easy to understand why every other movie palace in central Philadelphia has been demolished. Furthermore, that area of town is having a resurgence of high-rise construction, so one use of the property must be balanced against others.

|

| Sam Eric |

The Boyd was built in 1928, just before the stock market crash, and closed in 2002. In fact, it changed its name to SamEric in its dying days, but the public remembers it as the Boyd, one of ten movie palaces in center city. The definition of a "palace" is arbitrary but is generally taken to be a theater with more than a thousand seats, normally with hyperbolic architecture to fit its hyperbolic advertising. Scholars of the matter say the earliest movie houses were constructed in Egyptian style, soon evolving into French Art Deco. Ornate, whatever it's called.

The palace concept developed in the era of silent films, with subtitles. Anyone who has experimented with home movies knows that the silent film sort of lacks something, particularly between reels and at times of breakdown in the projection. That's why brass bands played on the sidewalk outside, pipe organs played during intermissions, and all manner of vaudeville appeared on stage. Sound movies, or talkies, were immediately much more popular when they appeared in 1927, and had less need of the window dressing from other distractions which had grown into a moviehouse tradition which was slow to die.

The movie studios owned the films and soon built theaters to display them. The movie business was quite profitable from the start, so studios had the necessary finance to spread a network of very large theaters across the country quickly. The ability to concentrate hyped-up advertising with immediate display of the product in large captive theaters tended to drive the model of the "palace", which was able to sustain higher ticket prices than trickling a larger number of film copies to myriads of small "mom and pop" local theaters. In very short order, going downtown to see movies became at one time the largest reason for suburbanites to go to the center of town on public transportation, fitting in nicely with the concentration of huge department stores, also located there. Restaurants, bars, bowling alleys, and shops grew up to address the crowds. Furthermore, the economic depression of the 1930s slowed down what was to become a relentless automobile-flight to the suburbs. After the spread of free television at home in 1950, the downtown movie palaces were doomed. The legal profession helped, too. Small suburban theater operators eventually won an antitrust suit against what they described as monopoly power of studio-owned center city palaces, so a host of small sharks in the suburbs started to eat the whales downtown. Furthermore, the sound quality was easier to achieve in a smaller auditorium. To tell the truth, fire hazard was also lessened without the arc-lamps needed to project images across a long distance.

So, a new technology interacting with an old theatrical tradition quickly created the movie industry in its downtown movie palace form; more advancing technology quickly destroyed it, with a little help from economics and politics. Good luck to the friends of this historical epoch, who have a monumental task ahead to work up the public nostalgia and political strength required to overcome a huge economic obstacle of the "highest, best use of the land". In many ways, the most valuable contribution of this movie palace restoration movement is to dramatize in the public mind just how urban centers function. Department stores are gone, going in town to the movies is over. How else are you now going to get the couch potatoes to go downtown voluntarily, and often? Just imagine ten palaces simultaneously filling up with several thousand suburbanites apiece, seven nights a week. Without those additional drawbacks on ample display in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, please.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1190.htm

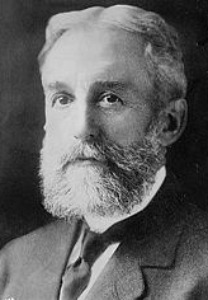

Andrew Hamilton (1676-1741)

|

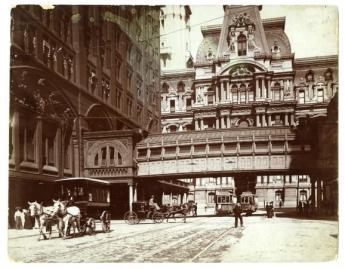

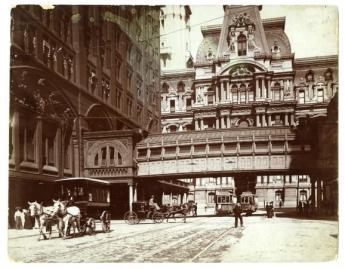

| Philadelphia City Hall |

An admirer of Philadelphia Reflections recently asked who is the most under-appreciated Philadelphian, and the quick answer would be William Penn. He's inadequately praised right at the present time, perhaps, but after all the whole State of Pennsylvania is named after him, along with countless universities and institutions, and his thirty-seven foot statue is on top of City Hall. The Pennsylvanian who seems most under-appreciated on a more or less permanent basis is Andrew Hamilton.

|

| Andrew Hamilton |

That is definitely not Alexander Hamilton, nearly a century younger and no relation. Andrew was born in Virginia but moved to Philadelphia in 1716, aged 30. He is frequently referred to as the finest lawyer of his era in America, holding numerous public offices. He was Speaker of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives in 1735, and 59 years old, when he took on the task of defending John Peter Zenger the New York publisher. For this successful case, he is mainly known today, but it is not true at all that he was then a young unknown lawyer trying to establish a reputation as, the lawyers say, a rainmaker. Rather, he took up the task of defending Zenger in another colony, without fee, because he felt there existed a threat to the entire judicial system and someone had to assert leadership about it. Zenger was in conflict with the Governor of New York, evidently a ruthless sort of person, and the Governor had disbarred Zenger's two defense lawyers for opposing him. Hamilton felt it was the duty of an eminent lawyer from another colony to come forward and see that justice was defended. It was surely not immodest of him to feel that even a wild and wooly governor would not dare disbar the famous chief legislative officer of Pennsylvania. There was probably still some personal risk, and even some risk to professional reputation, because Zenger seemed clearly guilty of breaking the libel laws as they were then understood.

t6

t6

|

| Trial |

Zenger had published articles describing the outrageous conduct of the Governor, and could not deny he had published them. In the common view, he had labeled the Governor. The judge refused to hear evidence that the published stories were true because the law stated that truth was not a defense. The only defense seemingly possible was that the stories somehow did not meet the definition of libel, and the judge suggested to Hamilton that he get on with arguing that particular escape-hatch. Hamilton, however, would have none of it.

|

| William Penn |

His first statement in defense was that he and his client readily admitted the published articles met the definition of libel, so he would save the prosecutor's time presenting witnesses on the point. He turned to the jury and urged them to nullify any law which prevented injured people from making a truthful complaint, as William Penn had established they had a right to do, nearly a century earlier. In a sense, both Penn and Hamilton were going back to the Magna Charta, where a jury was seen able to set a limit on what any king could do to an Englishman. The judge intervened that a jury may do what they were instructed to do. Yes, said Hamilton, and they may do otherwise. Although the jury had surely never heard of such legal fine points, they didn't like the idea of punishing a man for telling the truth, and firmly declared that Peter Zenger was therefore not guilty of anything, including libel, for doing so.

These principles were destined to become embedded in the United States Constitution fifty years later and were greeted with great praise and published applause by Benjamin Franklin, then the young publisher of the largest newspaper in Pennsylvania. Evidently, Franklin and Hamilton sought each other out, and in time Franklin became the protege and main political associate of Hamilton in the Pennsylvania Legislature.

The Zenger case established the fame of Philadelphia lawyers for all time, and Hamilton is honored by the Philadelphia bar association as their patron saint. No doubt he welcomed the praise of his colleagues, but he certainly did not need it. He had already risen to the top before this case, and it was for that reason he took it on, not as a duty to Zenger, but as a duty to the Law. Like so many people who achieve a little eminence, he had everything to lose and nothing to gain by taking risks. But unlike a common lot of prominent people, he felt a duty to do what he had to do.

Details of the rest of Andrew Hamilton's life are surprisingly sketchy, but property records establish that he was remarkable in a lot of other ways, too. He purchased the land on which Independence Hall is situated, and gave it to the public. He purchased five hundred acres in the wilderness and founded the City of Lancaster on it. And he purchased two hundred fifty acres, later expanded to six hundred, on the high bank of the Schuylkill where European settlement had been first begun by the Dutch, at Gray's Ferry. His son built Woodlands as a country estate, established Woodland Cemetery along Woodland Avenue, and built Hamilton Village as the place in West Philadelphia where the Drexels, Weightmans, Pauls and other wealthy families put their mansions. If you like, you can stroll down the center of the University of Pennsylvania campus, on Hamilton Walk.

|

| Penn Railroad |

Someday, the glory of all this will surely return. Meanwhile, the Pennsylvania Railroad and successors have made the Gray's Ferry area nearly uninhabitable. Woodland sits behind a thicket of untended bramble, hidden from the trains except for the briefest glimpse if you know to look. The Veteran's Administration Hospital sits on the edge of Woodland, blocking the view unless you know to use Google Earth to see it sitting there begging to be visited. The University has turned its back on Woodland, using it mostly as a backdoor driveway toward its numerous parking garages, fearful the world might notice how close it is to deplorable slums.

ut some day, we can confidently expect that vision will re-emerge, the Schuylkill waterfront should resemble the Seine through Paris, linking Woodland to Bartram's Gardens, and perhaps on to Fort Mifflin. When that day dawns, maybe more people will also remember who Andrew Hamilton was.

Venturi's Franklin Museum in Franklin Court

|

| Franklin Court Museum |

When Judge Edwin O. Lewis was seized with the idea of making a national monument out of Colonial Philadelphia, he wanted it big. Forty or so years later, it's big all right, but not big enough to encompass the whole of America's most historic square mile. Government ownership in the form of a cross now extends five blocks north from Washington Square to Franklin Square, and four blocks East from Sixth to Second Streets. Restoration and historic display have spread considerably beyond that cross, however, and the Park Service has created ingenious walkways within the working city in the neighborhood. If you thread your way through these walkways, you can stroll for miles within the world of William Penn and Benjamin Franklin. One such unexpected walkway is now called Franklin Court, which essentially cuts from Market to Chestnut Streets, within the block bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets. Hidden in the center is the reconstructed ghost of Franklin's quite large house, sitting in an interior courtyard bounded by a colonial post office, and a newspaper office once operated by Franklin's grandson. And, along the side of the walkway near Chestnut Street, is a fascinating museum of Franklin's personal life, built by no less than Frank Venturi, and operated by Park Rangers in the polished but low-key manner for which the U.S. Park Service is famous.

For some reason, this jewel of a museum has not received the high-powered publicity it deserves. It's off the main Park premises, as we mentioned, and some of the problem has to be attributed to Venturi. As you walk through, you don't expect a huge museum to be there, and it can look pretty inconspicuous as you walk past because it is mostly underground. Take my word for it, it's worth a visit. There are long descending ramps inside the doors, which can be pretty daunting if you are elderly and tired. But, also inconspicuous, there's an elevator if you look around for it. Venturi didn't seem to like windows very much, which is a problem for some people.

There's a movie theater inside there, playing a long list of fascinating documentaries. There's an ingenious automated display of statuettes which utilize spotlights and revolving stages to present Franklin in Parliament, resisting the Stamp Act, Franklin being his charming self before the French monarchs, and the frail dying Franklin getting the Constitutional Convention to approve the document. There are also a variety of ingenious inventions of Franklin's on display in the original, including bifocal glasses, the first storage battery, a simplified clock, several library devices, the Franklin stove, and so on. In some ways, the highlight is the Armonica.

The Armonica is the musical instrument invented by Franklin, for which both Beethoven and Mozart composed special music to exploit its haunting tone. If you ask the nice Park Ranger, she will be flattered to play you a tune on it.

Quaker Gray Turns Quaker Green

|

| American Friends Service Committee Logo |

Miriam Fisher Schaefer, at one time the Chief Financial Officer of the American Friends Service Committee, had to cope with the economics of renovating the business headquarters complex for various central Quaker organizations. They're housed in a red-brick building complex, naturally, located on North 15th Street right next to the Municipal Services Building of the Philadelphia City Hall complex. The original building within the complex is the Race Street Meetinghouse, funds for which were originally raised by Lucretia Mott. The Quakers needed to expand and renovate their offices, a nine million dollar project. Miriam, a CPA, calculated that the job could be made completely environment-friendly for an extra $3 million. The extra 25% construction cost explains why very few buildings are as energy-efficient as they easily could be. However, in the long run, a "green" building eventually proves to be considerably cheaper. Not only would a green Quaker headquarters be a highly visible "witness" to environmental improvement, but it would also pay for itself in reduced expenses after about eight years. That is, if friends of the environment would provide $3 million in after-tax contributions, they would provide a highly visible example to the world, and reduce the running expenses of the Quaker center by a quarter of a million a year, indefinitely. Effectively, this is a charitable donation with a permanent tax-free investment return of 12%, quite nicely within the Quaker tradition of doing well while doing good.

|

| Rockefeller Center |

Energy efficiency isn't one big thing, it is a lot of little things. If you dig a well deep enough, its water will have a temperature of 55 degrees, and only require heating up another 15 degrees to be comfortable in winter, or cooling down thirty degrees to be comfortable in the summer; that's described as a heat pump. Then, if you plant sedum, a hardy desert succulent plant, on the roof it will insulate the building, slow down rainwater runoff, and probably never have to be replaced. Rockefeller Center, you might be interested to learn, has a "green roof" of this sort, which has so far lasted seventy years without replacement. The Race Street Meetinghouse was built in 1854 and has so far had many roof replacements, each of which created a minor financial crisis when the need suddenly arose.

The ecology preservation movement is full of other great ideas for city buildings because buildings --through their heating, ventilating and air conditioning -- contribute more carbon pollution to the atmosphere than cars do. For another example, fifty percent of the contents of landfills originate in dumpsters taking construction trash away from building sites. What mainly stands in the way of more recycling of such trash is the extra expense of sorting out the ingredients. Catching rainwater runoff allows its reuse in toilets, eliminating the need to chlorinate it, meter it, and transport it from the rivers. And so forth; you can expect to hear about this sort of thing with great regularity now that the Quakers have got stirred up. You could save a lot of air conditioning cost by painting your roof white. At first, that would look funny. But do you suppose oddness would bother the Society of Friends for one instant? No, and you can expect them to make it popular, in time. People at first generally hate to look funny, but with the passage of time they grow to like looking intelligent.

A lot of people want to save the planet. So do the Quakers, but they have come to the view that the public is more easily persuaded to save money.

Broad Street North and South

Following the instructions of William Penn, all of Philadelphia's original numbered streets are laid out by the compass, due North and South. Without getting into a history of how the street names then got modified somewhat, Broad Street by the present system would be 14th Street. Center Square of the original five parks is placed at the intersection of Broad and Market Streets. After a period functioning as the city water-works, the intersection has been occupied by City Hall for over a century. Originally intended to be the tallest building in the world, the tower of City Hall still dominates the landscape in all four directions for a considerable distance. It also stands at the foot of the diagonal Benjamin Franklin Parkway, so City Hall stands like a Parisian intersection rather than the Scotch Irish Diamond it once was. Nevertheless, when you look down the long canyon of each intersecting street, the tower in the middle of the street dominates the view. Let's begin a tour of the whole extent of the longest street in Philadelphia, at the southernmost end of Broad Street, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

|

| Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey |

Although the guard will be happy to tell you it's a dumb regulation, you aren't allowed to take pictures of the Navy Yard, or visit without a pass, in spite of the fact the area of the yard is fast being converted into business properties. A great many of the warships that won our wars were built in this yard, and many rests in a sort of floating Navy graveyard, or mothball fleet, which is best seen from the elevated highway nearby, Interstate 95. The shipyards rest on the filled-in area around Hog Island, home of the hoagie sandwich. Just north of the Navy Yard are several sports stadiums and a great deal of parking space to service them. Much muttering is heard about the tax cost of this stadium farm, whose many-million-dollar facilities are only used for between eight and eighty home games apiece each year. The stadium-sprouting process began with Municipal Stadium which was built for the Dempsey Tunney prize fight, and held 110,000 spectators. In the time it housed the annual Army-Navy football game, but not much else, and has since been demolished. It certainly seemed to be the windiest, coldest place on earth, but that's just a child's recollection. At that time and for many years the area around the stadium was one huge garbage dump, and before that it was a huge swamp, the source of mosquitoes, malaria, typhoid and yellow fever. Fish like to eat mosquitoes, so filling in the South Philadelphia swamp badly injured the seafood industry of Delaware Bay, while admittedly ridding us of Yellow Fever epidemics. The swamp once extended as far as Gray's Ferry where the University of Pennsylvania now looms, with patches of quite rich farmland scattered in the swamp. Stephen Girard had a large farm just to the West of what is now South Broad Street where he cultivated vegetables necessary for the French cooking he favored.

|

| Mayor Richardson Dilworth |

As you drive north on Broad you begin to notice the quaint Philadelphia custom of parking your car in the center of the wide street. Mayor Dilworth once announced this had to stop, but the uproar from local residents forced even this ex-Marine officer to retreat. Down the side-streets a variation is seen; when the local resident drives off, he leaves trash cans in the street, indicating it is private property. Rumor has it that people who ignore the warning can get their windshields smashed with a brick. This area is as urbanized as you can get, but the spirit of the wild, wild West nevertheless prevails.

Acorn Club of Philadelphia

.JPG)

|

| Trish Brown |

Trish Brown visited the Right Angle Club recently, and told us about our club's feminine neighbor at 1519 Locust Street. She's the charming, witty new club manager of the Acorn Club, who often left this audience of men a little nonplussed about whether she was twitting us. For example, she told us that her club's policy about publicity. The policy states in one place that publicity is welcome, but in another place mention it must not mention the club's name.

.JPG)

|

| Acorn Club |

The Acorn is the oldest club for women in America, having been founded by Mrs. Thomas Biddle in 1889. The ladies of the neighborhood had taken to having walks together, and out of this association came the club, which soon found it needed a place to come in out of the rain. It started at 1642 Pine Street and was in five different locations until the present building was built in 1956. At one time it had 900 members, now has 700, of which 200 live more than 50 miles away. Unlike men's clubs, which are seeing a migration from lunch to dinner, the Acorn heavily favors lunch, usually on the days of local art, musical and literary events. It's one of two Platinum Clubs in Philadelphia, a quality designation for the top 200 (of 6000) national clubs. If you are interested in their cuisine, it may be sufficient to know that the top favorite dessert is creme brulee.

The club dining room seats 110, with 80 seats in other rooms, and has a staff of 11. There's definitely a dress code, but for women that's a little hard to define. Trish observes that it seems to lean toward pearls.

There's a cross-over alliance with the Philadelphia Club, where the husbands of many Acorn members belong. Both clubs are doing their best to adjust to changing times and customs, but Alfie Putnam once noticed a seemingly enduring feature. The flag, he said, is mostly at half-mast.

Frank Furness (2) Rittenhouse Square

|

| Frank Furness |

George Washington had two hundred slaves, Benjamin Chew had five hundred. It wasn't lack of wealth that restrained the size and opulence of their mansions, particularly the ones in the center of town. The lack of central heating forced even the richest of them to keep the windows small, the fireplaces drafty and numerous, the ceilings low. Small windows in a big room make it a dark cave, even with a lot of candles; a low ceiling in a big room is oppressive. Sweeping staircases are grand, but a lot of heat goes up that opening; sweeping staircases are for Natchez and Atlanta perhaps, but up north around here they aren't terribly practical. Building a stone house near a quarry has always been practical, but if there is insufficient local stone, you need railroads to transport the rocks.

|

| Early Victorian |

So to a certain extent, the advent of central heating, large plates of window glass, and transportation for heavy stone and girders amounted to emancipation from the cramped little houses of the Founding Fathers. Lead paint, now much scorned for its effect on premature babies, emancipated the color schemes of the Victorian house. Many of the war profiteers of the Civil War were indeed tasteless parvenu, but it is a narrow view of the Victorian middle class to assume that the overdone features of Victorian architecture can be mainly attributed to the personalities of the Robber Barons. This is not the first nor the only generation to believe that a big house is better than a small one. The architects were at work here, too. It was their job to learn about new building techniques and materials, and they were richly rewarded for showing the public what was newly possible. Frank Furness was as flamboyant as they come, a winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism, a man who wore a revolver in Victorian Philadelphia and took pot-shots at stuffed animal heads in his office. He affected the manners of a genius, and his later decline in public esteem was not so much disillusion with him as with the cost of heating (later air-conditioning), cleaning, and maintenance which soon exceeded provable utility. The simultaneous arrival of the 1929 financial crash and inexpensive automobile commuting to the suburbs stranded square miles of these overbuilt structures. It was the custom to build a big house on Locust, Spruce or Pine Streets, with a small servant's house on the back alley. During the Depression of the 1930s, there were many families who sold the big house and moved into the small one. Real estate values declined faster than property taxes and maintenance costs; incomes declined even faster.

|

| Delancey Street |

It thus comes about that large numbers of very large houses have been sold for very modest prices, and the urban pioneers have gentrified them. You can buy a lot of house for comparatively little if you are willing or able to restore the building. We thus come back to Frank Furness, who was the idolized architect of the Rittenhouse Square area, in addition to the massive banks and museums for which he is perhaps better known. Unfortunately, most of the Furness mansions on the square have been replaced by apartment buildings, but one outstanding example remains. It's sort of dwarfed by the neighboring high-rises, but it was originally the home of a railroad magnate, a few houses west of the Barclay Hotel, and it holds its own, defiantly. Inside, Furness made clever use of floor-to-ceiling mirrors to diffuse interior light and make the corridors seem wider. Although electric lighting made these windowless row houses bearable, modern lighting dispels what must have been originally a dark cave-like interior on several floors, held up by poured concrete floors. Furness liked to put in steel beams, heavy woodwork, and stonework, in the battleship school of architecture. If you were thinking of tearing down one of his buildings, you had to pause and consider the cost of demolition before you went ahead.

|

| Frank Furness Window |

There are several others of his buildings around the corner on the way to Delancey Street, one of them set back from the street with a garden in front. That's what you expect in the suburbs, but the land is too expensive in center city for very many of them; this is the last one Furness built before rising real estate costs drove even him back to the row-house concept. On Delancey Street, there is a house which he improved upon by adding an 18-inch bay window in front. The uproar it caused among the neighbors is still remembered.

|

| Doctor Home and Office |

A block away on the part of 19th Street facing down the street, Furness built another reddish brownstone house to glare back at the neighbors. The facings of the front suggest three-row houses, and it was indeed the home of a physician who had his offices on one side, entrance in the middle, and living room on the right. The resulting staircase in the middle is used to good effect by opening a balcony on the landing overlooking the parlor below. As befits the Furness style, the wall is thick, the wooden beams heavy. And, in a gesture to the lady of the house, the room adjoining the living parlor is a modern kitchen so the kids can play while mama cooks or guests can wander by as she gets dinner ready. Times have changed, the servants quarters once were plain and undecorated. The lady of the house never set foot in the kitchen so she could care less what it looked like.

|

| Frank Furness Home |

As a matter of fact, that's the remaining problem for these places, the rate-limiting factor as chemists say. Automatic washers, microwaves, electric sweepers, spray-on cleaning fluids and similar advances are the new industrial revolution which makes these hulking mansions almost practical. What's still lacking is the social structure of Upstairs and Downstairs, the servant community overseen by the lady of the house, who once was sort of the Mayor of a town. The lady of the house is now a partner in a big law firm, or similar. It simply is not wise to leave a big expensive place unattended by someone constantly supervising the domestic help. It is never entirely safe to leave the financial affairs of the household in the hands of someone who is not a central member of the owning family. Perhaps the father of the family can be brow-beaten into spending some quality time with the children once in a while.

|

| Structure of Upstairs and Downstairs |

Perhaps an accountant can for a fee be trusted with the finances; perhaps a butler can be found who will whack the staff when they get out of line. But the plain fact is these monster houses were built around the assumption that the lady of the house would run them, and the old style of manorial life cannot return unless the house is completely redesigned for it. Someday, perhaps a genius of the Frank Furness sort will make an appearance, change everything, and make everybody want to have it. But it is asking for something else when you insist on this happening in an old stone fortress that was designed to house a different style of life.

Frank Furness (1):PAFA

|

| Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts |

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art is notable for its place in Art history, for its faculty over the centuries, and for its influential student graduates. It is therefore not to slight the institution's remarkable place in the world of art if we pause to notice that the building itself, the place that houses all this, is itself an outstanding work of art. Whenever mention is made of Frank Furness, its colorful and influential architect, the first stop on the list is the building he built to house a school and display its glories. Perhaps the best way to illustrate the achievement is to compare it with the Barnes Museum, which also was built to house a school. It also has an outstanding permanent collection, perhaps a greater one than PAFA. But the Barnes building scarcely gets a mention and is about to be abandoned for a preferable location. The Furness building, however, is a massive pile of solid rock, immovable throughout massive changes in its neighborhood. To move that building out to the Parkway has never even been suggested. You can move if you like; we were here first.

The exhibition rooms are interesting, even clever, but the hand and mind of the architect are best seen in the school, the Academy. Seldom seen by the public, the entrance to the school is underneath the front staircase which sweeps the public visitors off to see the exhibition. Up to the stairs, admire the carved walls, the massive supports and the iron railings and out into rooms with scarlet and gold walls, and a blue ceiling with stars. When it leaves, the public sweeps back down the inside stairs and out the tunnel-like entrance, then down the outside stairs. Where was the school?

|

| PAFA Marker |

It's underneath the exhibition area, reached by a door under the stairs, unnoticed unless you ask for it. There you will find a darkened lecture hall and corridors lined with plaster casts for teaching purposes. But an artist's studio must have diffused northern light, and lots of it; the problem for the architect was to provide a huge slanted northern skylight over a basement. This trick was accomplished by pushing the walls of the first floor out to the street and installing a slanted skylight in the "ceiling" of the overhang. When the overall effect is that of a fortress meant to defend against a barbarian invader, built with massive walls and roof -- hiding a glass skylight is quite an achievement. Furness was a showman; it was not beyond him to place an architectural tour de force right in front of generations of students looking for something to portray.

We are told the building was five years in construction, designed and re-designed as it rose. The resulting effect is achieved by building around its interior as it evolves from bottom to top. Quite a difference from buildings laid out in advance, forcing the interior contents to conform to the initial design without regard to cramming down its contents. There is an overall design at work here; it's evocative of a Norman church with side extensions, but you have to look for that rather than having the architect thrust it in your face.

Philadelphia's Big Ben

|

| Worlds largest bell in St. Petersburg, Russia |

The largest bell in the world is reported to be in St. Petersburg, Russia, but the second largest is in Philadelphia. No, it isn't the Liberty Bell, which is cracked and dysfunctional, but smaller in any event. The bell sound is so penetrating it seems to come from everywhere, so it isn't surprising that many people believe it must be coming from the tower of City Hall. That's fairly close, but in fact, the bell is atop the former PNB building across the street between Chestnut and Market. When that so-and-so rings, you feel it in your bone marrow even if you are five blocks away. Because it's so big, its note has a very long period of decay, with the result that when it rings it rings very slowly and deliberately.

People who have been there reported the surprising news that there is a penthouse apartment right underneath the bell, which is so well insulated that you can hardly hear the bell toll. Underneath that, however, are suites of offices where the ringing of the bell vibrates enough to knock the fillings out of your teeth. The law department of the Philadelphia National Bank used to be right in the midst of those offices. It's reported that the lawyers in the place were busy at 11 AM every day, inviting somebody, anybody, to go out for lunch. Meet you at the restaurant or club at 11:45.

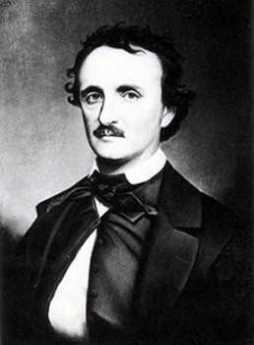

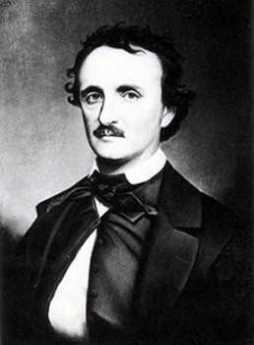

Edgar Allan Poe, 1809-1849

|

| Edger Allan Poe |

Between the Federalist period and the Civil War, Philadelphia quadrupled in population, mostly by Irish and black immigration responding to the urbanization induced by the Industrial Revolution. The social boundaries of this period were established by the U.S. Capital moving away to Washington, and at the other boundary, the constrained urban population was suddenly released to the suburbs by the City-County Consolidation of 1854. During that time, the Northern Liberties on the other side of Callowhillwere very close by, but nearly devoid of law and order. At least along the Delaware River, the scene was like Las Vegas as imagined by Charles Dickens. Within the increasingly congested boundaries of the city itself, tuberculosis, alcoholism, riots and religious revivalism are all mentioned prominently. While it was the time of Nicholas Biddle and the Bank, and the establishment of the Drexel empire, it was a gothic period quite adequately symbolized by Ethan Allan Poe, writing for Graham's Magazine. His father abandoned the family, his mother and later his wife died of tuberculosis, he was definitely an alcoholic and probably manic-depressive. He and Charles Brockton Brown invented the gothic novel, gothic poetry, the modern murder mystery. Poe only lived in Philadelphia for six years but lived in seven different locations, the most famous of which is now part of the National Park Service, even though it is located off Spring Garden Street. Yes, he was born in Boston but lived there only briefly, and yes, he died in Baltimore, by dropping dead in the street while traveling through. He was scarcely a prototypical Philadelphian, but he was certainly a symbol of his age.

|

| Grip the Raven |

There is a big stuffed Raven named Grip in the Free Library which belonged to Charles Dickens and is claimed to be the inspiration for Poe's Raven; it certainly has an ominous look, whatever its provenance. Poe offered his famous poem to Graham, who rejected it but gave him $15 as an act of charity. Another magazine paid him $9 to publish it. This poem was widely included in elementary school anthologies by the Philadelphia book publishing industry, and its simple repetitions with a scary atmosphere continue to be popular with children. The Murders in the Rue Morgue were the beginning of the modern murder mystery, and seem to have started Brockton Brown off on his establishment of the Philadelphia Gothic novel, echoing the whole dark and menacing Poe tradition. From the descriptions, Poe's alcohol problem was not so much related to the volume of consumption as to the violent manias which just a small quantity provoked in him. If your mother and your wife both died of tuberculosis, it's a fair bet you had it, too. At the age of 40, he was gone.

Re-Doing Dilworth Plaza

|

| Richard Maimon |

Richard Maimon recently visited the Right Angle Club to tell us all about the architectural plans afoot to consolidate the underground transportation network underneath City Hall, change the patterns of foot traffic, open up the views, and draw the visitors to the expanded convention center into the city itself. All of this is to be accomplished by paving over Dilworth Plaza and planting it with grass, along with an extensive fountain installation which can be used for winter ice skating. In the course of creating an entrance hub for Septa, the Broad Street and Market subways, walkways are rearranged and -- it is hoped -- the foot traffic around City Hall will shift around to make it a real city center. It's a very expensive dream because of all the overlapping transportation tunnels hidden under the largest and heaviest stone building in America, leading to a great deal of expensive construction work that doesn't show.

|

| interior view of concourse north_ |

Dilworth Plaza is currently almost completely deserted, so its conversion will not be much mourned. However, the mixture of contemporary transportation entrances with the neo-classical architectural style of City Hall will probably meet resistance, and there is concern that excessive foot traffic could convert a grassy park into a mud puddle, while a large open-air lake could become a public rest-room for the homeless if the designers aren't careful. To some extent, the public forces to be resisted in the design will be self-policing if the anticipated foot traffic is at the anticipated level, but overwhelmed if the project is too successful, or left to deteriorate if it fails to succeed. And it's all too expensive to do twice; the designers have to get it right the first time.

|

| Section Pavilions |

So, it all comes down to money. Construction costs are less during a recession, but raising money is easier during a booming economy. High hopes are raised for a Democratic governor to be able to persuade a Democratic president to divert stimulus money our way. High hopes are raised for a former Mayor's ability to divert state funds to our part of the state. In other words, it all depends on Governor Rendell, now that Senator Specter has navigated himself off the Appropriations Chairmanship. In our system of government, public works projects have to be placed somewhere, so the best system is to rotate the goodies in an informal way. This rotation, in turn, depends on a geographical rotation of the top political officers, since they can claim that it is "Philadelphia's turn". So, the grim reality is that only two Philadelphia mayors in history have become governors of the state, with the rather bitter result that Philadelphia has been neglected in the siting of the available public projects for a very long time. Digby Baltzell long preached that it was our own fault, for being too non-aggressive. But most of the rest of us, particularly those who have wrangled with the upstate legislature, blame the situation on narrow-minded opposition from those who have worked the gerrymandering game for a couple of centuries.

Christmas Reflections

My father in law, a prominent obstetrician in Binghamton, New York, regularly took his family to New York City sometime between Thanksgiving and Christmas. The three-day junket was described as a visit to do Christmas shopping. Another relative made similar trips from home in Tyler, Texas. Several of my patients made such visits to Philadelphia from their homes in West Virginia, stopping by to make a medical visit to me during the same trip. From the seasonal crowds in Penn Station and in the shops on Chestnut Street, it was clear that an annual visit to the big city was a common custom in the upper crust of small to medium-sized cities, for whom the more expensive shops of the bigger city provided big-ticket items bought infrequently, and the distinctive luxuries which made them stand out from the socially less-enlightened back home.

These shopping visits were not confined to purchasing, although that was the main focus. It was a time to go to the theater, orchestra and opera, maybe an occasional ballet and art exhibit. The choice of a large city might be related to returning to the University, or another period of professional training for a drop-in visit because these associations made it possible to observe the latest trends and innovations, a useful issue in the smaller towns. The ladies could observe the trends in fashions, and everyone would have a chance to dress up in the better hotels and restaurants. This recirculation between the small towns and the big one at the hub unified the region, establishing hierarchy rather widely. And it hardened traditions in the big city, since islanders tend to return to the same hotel, restaurants and social gathering spots even more than the local residents do; there isn't time in a brief visit to shop for new venues, unless the trip itself reveals that times and places have somehow changed in an important way.

|

| Wannamakers Pipe Organ |

That's all changed, today. The pipe organ at Wannamakers, the cluster of department stores around Eighth and Market, the theater district, Caldwell's and Bailey Banks and Biddle upscale jewelers, the fancy women's clothing shops on Walnut and Chestnut Streets, and the bespoke men's tailor shops -- have disappeared in a slew of retail despond. The excited crowds of upscale shoppers have dwindled, at least in the center city shopping area. Students of sociology point to the decline of the department store as a central commotion in the center of this phenomenon, blaming that in turn on the spread of national brand names by television and more electronic forms of advertising. The department store did your comparison shopping for you, putting its brand name on the product and placing its reputation behind the choice. If Wannamaker could determine that a Japanese radio was of high quality, it became Wanamaker's radio. Today, Samsung and Sony do their own advertising, sell their products through outlets in the suburban malls. Philadelphia residents enjoy as much retail choice and pricing as ever, they just shop in the malls located along the Interstate circumferential highway, just outside what used to be the outermost suburbs. So the volume of retail shopping among Philadelphians probably hasn't changed a great deal; it has merely shifted to the malls where there is parking for your car to transport goods which the department stores used to deliver. It is the annual visits from the subordinate small cities at moderate distance that has disappeared. Small cities now have their own shopping malls, carrying national brand name merchandise. Losing this source of business, the associated entertainment industry has declined to a point below sustainability for most of them -- in the center city hub. Along with the disappearance of this regional recirculation, small cities have lost their sense of affiliation with a bigger one. The small-town professional class which was the biggest participant in this annual migration is professionally more isolated but so are their clients. The upper crust of the small town now must constrain its horizon to the smaller town professionals, with their lesser claim to distinction. For a while, the disparity can be overcome by specialization, but ultimately the distinction of the big-city specialist rests on assembling a richer experience from wider drawing power. In Medicine at least, the insistence of Medicare on paying the same fee for the same service lessens the economic incentive for self-repair of the system.

|

| Wannamaker's Christmas Light Show |

Meanwhile, nature of Christmas itself is becoming standardized. Fewer people make their own Christmas presents, whether through knitting or baking. If the process of commercial gifts goes the full distance, eventually the joy of searching for exactly the right gift will seem more like paying your taxes. These things already cost too much, are worth too little, and neither the process of giving a gift nor the process of receiving a welcome gift will retain much joy. Or significance. What was until recently a Christian religious celebration has become diversified into a generic "Happy Holiday", presumably in order to avoid offense to other religious groups who themselves likely persist in their old traditions of ritual greeting. The assault on Christmas is however not primarily cultural, but commercial. The silent ostentation of elaborate outdoor lighting and the secular versions of Christmas carols endlessly replayed over loudspeakers in stores, probably have a more destructive effect on the community winter solstice ceremony than any competition for religious adherence.

The coming next step in the modification of the Christmas season is dimly visible in the assault of pocket telephones on the suburban shopping mall. After enjoying only a few years of victory over the center city department store, malls must now confront shoppers with portable telephones containing a camera and GPS geographical locator. Seeing something he likes, the shopper of the future can photograph its bar code in the shop display, and be immediately told of all the neighboring stores which sell the same product for a lower price. Electronics are thus about to turn Christmas shopping into an electronic auction, no doubt making it eventually easier to do the shopping from home.

What Christmastime means to me is a recollection of what it once was like at the nation's oldest hospital, and not so terribly long ago, at that. Before 1965, the Pennsylvania hospital had been staffed for centuries with unpaid student nurses, working under the direction of unpaid doctors in training, supervised by volunteer attending physicians. Of the five hundred beds, only forty were filled with paying patients and the rest were housed in long communal halls. On Christmas morning at 7 AM, the drowsy patients were astonished to be awakened by a procession of very pretty student nurses, led by Miss McClellan the grim-looking Directress of nursing, and followed by a handful of internet and residents, all singing Christmas carols and carrying lighted candles in the dark. Miss McClellan herself was never heard to utter a note, but the student nurses had been trained in four-part harmony, and the interne doctors were enthusiastic followers. The faces of the poor old indigents in the beds were filled with pure delight as we traipsed past, chanting of the travels of Orient kings, the pregnancy of virgins, and other miracles of the occasion.

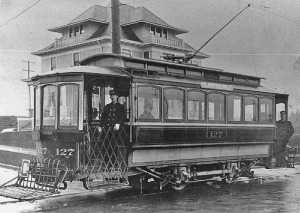

Urban Transportation

Stuart Taylor, who spent twenty years working for the Pennsylvania Railroad in the company of our member Bill Brady, recently gave the Right Angle Club his observations about urban transportation, which grew out of his second career as a consultant. As he describes the evolution from the horse-drawn omnibus carriage to the horse-drawn trolleycar, to the steam-driven trolley, to the electric trolley, to the underground subway, certain parallel historic movements occurred to at least one member of this audience.

|

| Horse-Drawn Trolley Car |

In the first place, mass transportation is only of value when cities grow to a large enough size to justify the expense. And the growth of cities in the 19th Century was propelled by the Industrial Revolution attracting mass immigration into urban centers. Whether the Industrial Revolution is over or not, is a topic which could be debated, but it was the gasoline engine which made buses and autos attractive, and the decaying slums made cities sufficiently unattractive to cause the flight to the suburbs in the 1920s and 1930s, heavily resumed after World War II in the 1950s. During the heyday of city growth, the evolution of mass transit seemed to be driven by technology, and that in turn attracted private ownership. When the gasoline engine and/or the decline of the Industrial Revolution made the Flight to the Suburbs possible, it made urban transportation unprofitable and hence unattractive to private business owners. Somewhere just before or after the 1929 Crash, the changing situation made it more attractive to live and/or work in the suburbs. A sign of this change in dynamics was the total disappearance of private ownership of public transportation and its supporting infrastructure, and replacement by public ownership and public tax subsidy. As local politics began to reflect this change, Urban politics somehow became dominated by Democrats, and Suburban politics became dominated by Republicans; so the enthusiasm for mass transit has waxed and waned as the political domination of federal subsidies has shifted between the parties. That's probably only an outward sign, however. The real issue is that urban transportation now has to be subsidized since its base has shrunk to the point where people like Widener and Elkins invest in other things. And do so from their homes in exurbia, where the neighbors could care less about subways, let alone pay taxes to subsidize them. And until the city gets control of its crime, public schools, and taxes, it's hard to see what will attract them back in town.

|

| Electric Trolley |

That's perhaps an overly censorious view, coming from a resident of the suburbs. A more economic view of things would be that the construction of underground subways now costs about a billion dollars a mile. Very few cities and no private entrepreneurs can justify costs of that magnitude since the potential ridership cannot afford the costs per ride which are implicit in that capital expenditure. Until the cities can manage to entice the suburbanites back into town, those people will solve their air pollution problems by avoiding the cities. Living to the windward seems much more plausible to them. China is just beginning this process, but they have the advantage of building the subways first, then the surrounding skyscrapers, and thus greatly reducing the costs of avoiding underground sewer systems, etc. If you could call it that, the Europeans had the advantage of massive war destruction, along with much more expensive farmland to inhibit suburbanization. None of this is an argument that we shouldn't build subways, or clean up the atmosphere. It's just a warning of the daunting construction costs and staunch political opposition to mass transit. Not to mention featherbedding, over-hiring, massive hidden benefits costs, and other features which seem to be inherent in union activity, at least of the historical variety.

A member of the Right Angle audience asked the speaker what he thought of the proposed Market Street light rail line. Insane, was the answer. No visible ridership. And that seemed to summarize the present debate.

Except that it really shouldn't frame the argument for Philadelphia. Philadelphia doesn't need a mass transit network, it already has a mass transit network. Much of it is growing obsolete, but the land costs and local opposition to change are greatly diminished when the network is already there. If any city can do it, Philadelphia can. The technology will surely evolve enough for our purposes if the money is there, and the money will be there if people return to using the city. What Philadelphia needs is a return of business headquarters and other sources of employment, bringing the ridership and the public demand along with it. And for that, what is essentially needed is for government to address our problems of uncontrolled crime, inferior public schools and maladministered taxes.

Mayors and Limos

|

| Mayor Richardson Dilworth |

A number of prominent figures participated in the downtown revival of Philadelphia after the Second World War, with a surprising amount of jealousy among them. Mayor Richardson Dilworth would have to be mentioned in any list of those leaders, but one who was more admired than loved. Aristocratic and flamboyant, he disdained the little hypocritical dissembling so characteristic of politicians. In fact, he didn't see himself as a politician at all, he was a leader.

Once Dilworth became convinced that Society Hill revival was not only desirable but feasible, he moved there. He purchased two houses next to the Athenaeum on Sixth Street, and in spite of the protest of preservationists that those two houses were particularly fine examples of Federalist style on Washington Square, he had them torn down. Furthermore, in spite of outcries that the house he was building in their place was merely a pseudo-colonial gesture, he constructed a very expensive but extremely comfortable modern house. Those of us who were familiar with the neighborhood were impressed with the courage he displayed in doing this, because the area was just a little dangerous, and almost no one else lived there. You could buy dozens of twenty-room houses in the neighborhood for less than $2000 apiece, and it seemed foolhardy to make such a large personal investment in what might become a stranded gesture. This was described as flaunting his personal wealth because it was not just a fine house, it was possibly going to be a big loss.

Dillworth got away with it. He was seen as courageous, and a leader. Others started moving into the area, mostly rehabilitating old mansions. By the time the house was eventually sold by his estate, his conspicuous consumption turned out to be a profitable investment. Smart.

Dilworth had some practical problems. It wouldn't have been smart politics to have a long black limousine pick him up in the poor neighborhood. The only people who do that are undertakers and the Mafia. On the other hand, the driver of a limousine often doubles as a bodyguard, and a bodyguard wouldn't be a bad idea. Those of us who drove down 6th Street every morning at 8:30 gradually noticed what Dilworth did to solve the problem.

|

| Frank Rizzo |

Every morning a Yellow Cab could be seen parked outside his door. It always had the same uniformed driver, and on closer inspection, the cab was the cleanest shiny late-model car, painted yellow. It was only six or seven steps from the door of the house to the door of the car, and he was off and gone in a moment.

Other mayors have had quite different styles.Frank Rizzo had his long black car and several like it parked on the sidewalk outside City Hall. His image was that of a poor boy from the neighborhoods who had made it to the top. No matter where he went, Rizzo was leading a parade.

|

| Ed Rendell |

Ed Rendell, on the other hand, was playing the role of America's Mayor. His driver would blow the horn, put on the headlights during the day, roar through town, making screeching u-turns right and left. Several times a day he would put on this act, going two blocks from City Hall Annex to the Convention Center, to address an audience of visitors.

Well, mayors and bank presidents are supposed to have limousine service. Anyone else would have to ask whether it was worth all the trouble if instead, you could just catch a cab. Those long cars are surprisingly uncomfortable to ride because the roof is so low you have to crawl on hands and knees to get in a seat. Finding a place to park one of those monsters, or even a wide enough opening next to the curb to let out the back-seat occupant, can be a problem in the center of a city. Even with portable cellular phones, there is a delay after you call for the car when you are ready to leave your appointment. Those who have tried it find that hiring a driver almost always confronts you with a demand to circumvent taxes by paying the driver in unrecorded cash. In South America, where bodyguards are really necessary, the great majority of them flee in terror at the first sign of the underworld. Limos are a pain.

At least in Philadelphia, you can get a fairly clean, fairly new cab with a fairly knowledgeable driver, by simply holding up your hand at any center city street corner. During business hours at least, you can hail a cab in three minutes. That doesn't just happen that way, and the mayor has something to do with it. Cities usually have a Medallion system of cab licensing, and existing cab companies don't want any medallions issued to competitors. In politics, such a situation helps campaign funds considerably. The result is a shortage of cabs, surly drivers, and high prices. Boston is such a town. On the other hand, if medallions are easy to obtain, as they are in Washington DC, the cabs become numerous enough but are shabby dilapidated old vehicles, driven by recent immigrants who don't know the street names. In Philadelphia, we take our good fortune for granted, but we do owe a debt to the city government for managing the supply and demand situation to the point where it mostly would be foolish to have your own car and driver. In this town, every man a king.

As a matter of fact, in Boston it got so bad that Ned Johnson, the richest man in town (he personally owns the Fidelity Mutual Fund Investment Family) got so enraged that he couldn't ever get a cab that he founded his own cab company. It's a very elegant one, although a little expensive. The Boston Coach Company supplies immaculate and impeccable service for a fee. At first, it was only available to Fidelity executives but now has spread out to anyone willing to pay for it, and flourishes in many cities, plus chartered airplanes if you don't like to wait in security lines at airports. You have to admire Johnson for his golden business touch, but in Philadelphia, we can just use cabs.

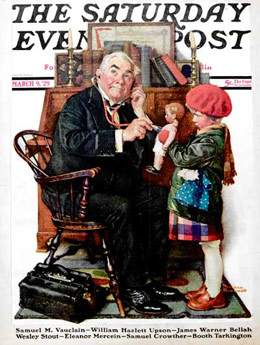

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

The Kimmel Center: Comments On The Economics of Music

|

| Kimmel Center |

In 2001, The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts opened to the public, at a cost somewhat to the North of $200 million, and an annual budget in excess of $80 million. Although the generosity of Sidney Kimmel and Raymond Perelman must be gratefully acknowledged, and the ambitious energy of Philadelphia's political and musical worlds must be admired, there is little question that the city strained its resources to the utmost to achieve the new center. The Philadelphia Orchestra must appear on anyone's list of the best symphony orchestras in the world. It's likely going to stay there, too, because the orchestra stands on a wide base of associated Musical schools, chamber music groups, and intensely loyal musical audiences. As they say in baseball, they have a deep bench.

Nevertheless, software piracy has just about eliminated an important source of income from the sale of recordings, seat prices are dauntingly high, other symphonies and other forms of entertainment have greatly improved in recent years. First-class musicians are not paid like sports stars, perhaps, but the top layer begin their careers with salaries in six figures, and top conductors commonly receive a million dollars a year, just like corporate executives. Between the high costs and the practical upper limit to what audiences will pay for a seat, about a third of the budget must be subsidized by some form of donation or fund-raising. It takes a lot of effort to raise thirty million a year.

For reasons not entirely clear, the Kimmel center

|

| Academy of Music |

is a free-standing corporate entity, whose main tenant (the Orchestra) owns a competitive music hall, the old Academy of Music. In other words, the capacity of Philadelphia's musical locations has been substantially increased. Increased, that is, beyond the metropolitan area's capacity to fill seats for classical music. A season's list of seventy-five productions may not fill the capacity, but the production schedule is limited by the fact that almost every production sustains a loss which must be made up by fund-raising.

Following Julius Caesar's

|

| Julius Caesar's |

motto that Fortune Favors the Brave, the leadership of the town has embarked on a daring musical exploit. The remarkable design team constructed the hall along highly innovative lines, based on movable wooden wall panels, controlled by computers. The hall itself becomes an instrument, slowly adapting and learning from each orchestral piece to produce an evolving product that no orchestra could produce without the hall to surround it. No one yet knows how far this idea can be taken, but it is possible to imagine four or five quite different versions of the same piece, each one recognizably distinct and with its own following.

And revolving stages, adaptable hall design, and computerized modeling make it possible to have performing arts, not merely classical symphonies. It remains to be seen whether the designers can achieve perfection in a number of different forms, not merely limiting the design to a specialized version for a single purpose. If that works, capacity can be increased by redefining capacity. Just imagine what a wedding you could hold there.

And just imagine how that worries the owners of the other six theaters in the neighborhood. In fact, just imagine how it worries the Philadelphia Orchestra to learn that there are plans to bring other visiting orchestras to town. Or how it worries other cities to hear that Philadelphia hopes to draw musical audiences from a long distance. There's going to be some creative destruction here, and some high adventure.

Following the Rules

Contrary to press accounts, I did not warn the President about anything and was very respectful of is Constitutional authority on the appointment of federal judges.

|

| Sen. Specter |

As the record shows, I have supported every one of President Bush's nominees in the Judiciary Committee and on the Senate floor. I have never and would never apply any litmus test on the abortion issue and, as the record shows, I have voted to confirm Chief Justice Rehnquist, Justice O'Connor, and Justice Kennedy and led the fight to confirm Justice Thomas. . . .

In the lame-duck season after the 2004 Presidential election that is, during that two-month interval between the November election and the January inauguration Senator Arlen Specter (R, PA) said something or other about upcoming Senatorial confirmations of Federal judges. As the probable next chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, but known to be in conflict with most of the Republican party on the subject of legalizing abortion, his influence would bear an important influence on the outcome. The Senate Republican leadership then said something or other which had the basic significance of, "You aren't going to be elected Chairman of the Judiciary Committee unless we know in advance where you are going with this matter." Regardless of the merits, and regardless of its eventual outcome, the episode illustrates a little-understood but crucial moment in the history of any Congress. The moment lasts about five minutes, and it only comes once, every two years.

|

| Sen. Arlen Specter, (R) PA |

You can't run a parliamentary body without rules. The first item of business, therefore, must be the adoption of rules. With rare exceptions, the traditional set of rules is proposed and adopted. All done. Don't bother us any more on this topic, because the rules just adopted ordinarily provide major obstacles to change once adopted. Since committee appointments are next on the agenda, and committee membership is vital to legislative effectiveness, and since committee appointments are in the hands of the majority party leadership, this is not the moment for a new legislator to be making trouble. And an old legislator wants to progress toward chairmanship of his prized committee.

Among things which the rules, adopted in a twinkling, provide for is whether committee chairmen are elected by the members of the committee, or selected by the leadership. For the most part, this issue is so sensitive, that traditional resolutions of it rely on seniority. Like the selection of a King by elevation of the first-born male offspring of the last one, the seniority system does not always choose the best candidate, but it avoids bloodshed and allows progress toward the business at hand. After all, when committees are evenly divided and hotly contested, the adversary environment will ensure that the chairmen can't get away with much. Conversely, in a committee heavily weighted toward one side of a controversial issue, that majority will surely get its way. Either way, it doesn't make as much difference who is chairman as it first seems; you might as well let seniority rule.

The rules of the House of Representatives allow the Rules Committee to limit debate on an issue to a time fixed in advance. Hidden in this rule is the power of the leadership to select who is going to speak, who is going to be excluded. When you elected your local congressman, you probably didn't anticipate he might not be allowed to speak on your favorite topic, but that's the way it works out. In the Senate, on the other hand, there is a rule of unlimited debate by any Senator on any topic, for whatever duration. Or almost. When some Senator has had all the blather he can stand on a topic, he is privileged to rise and say, "Mr. Speaker (vice-President), I move that we vote immediately on this and all pending matters." To which the person in the Chair will reply, "That motion is in order, but it requires an affirmative vote of 60 Senators to be adopted. All in favor, please signify by saying 'Aye.' " That's where filibusters come from, and it's all in the rules.

Rules adopted in the first few minutes of the opening session are very difficult to change once adopted. Creating situations the founding fathers never contemplated, perhaps, but also very hard to argue with under all the turbulent circumstances of a democracy. Or, perhaps, a Republic.

Two Hotheads May Have Destroyed an Empire

|

| King George III |

Combatants in a war often personalize the enemy in a single person. In 1776 the American colonists blamed it all on King George III. The British might have picked Sam Adams or Thomas Paine. Things are of course always vastly complicated in the affairs of great nations. Economics and national power are strong forces, like our culture, religion, and the accidents of geography and history. But when matters teeter on the edge of a cliff, insignificant pests can occasionally start an avalanche.

|

| Charles Townshend |

Consider first Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of England's exchequer in 1768. Townshend didn't particularly want the job, hoping instead for the Admiralty. None of the political power brokers particularly wanted to give him the job, but ultimately regarded it as the place he could do the least harm. He might have had no less an advisor than Adam Smith, who was the tutor of his son, but Smith's letters to him are so servile that it seems unlikely he would urge free trade to such a headstrong merchantilist employer. It is intriguing to speculate this strange association might have sharpened Smith's opinions in the Wealth of Nations which first appeared in 1776./p>

|

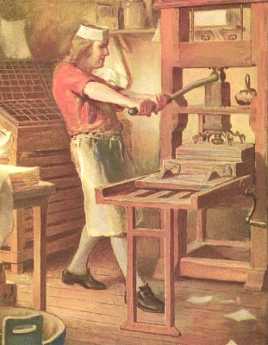

| William Bradford |

Townshend had been a problem all his life. His mother was brilliant, and notoriously promiscuous. He and his father exchanged 2000-word letters explaining to each other how the other was completely wrong. Charles was witty, eloquent and charming when he wanted to be, and he married an enormously wealthy woman. After that, his family had no hold on him, and they rarely spoke to each other. The same charm and arrogance can be perversely effective in politics, so other politicians often just had to put up with him. But as politicians do, they roasted him in their letters and private conversations. His political opponent, Edmund Burke, was perhaps a most gentle critic when he observed, "His actions... seem never to have been influenced by his most wonderful abilities." Opponents, of course, welcome deficiencies in their enemies, while exasperated political allies can be the most scathing about team members who injure the party with misbehavior. Adam Smith referred to his employer as someone "who passes for the cleverest fellow in England." Chase Price described him as "utterly unhinged". Horace Walpole: "nothing is luminous compared with Charles Townshend: he drops down dead in a fit, has a resurrection, thunders in the Capitol, confounds the Treasury bench, laughs at his own party, is laid up the next day, and overwhelms the Duchess [of Argyll, his mother-in-law] and the good women that go to nurse him!" The final assessment of his biographer Sir Lewis Namier was "...illustrations of Charles Townshend's character can be picked out anywhere during his adult life. He did not change or mellow; nor did he learn by experience; there was something ageless about him; never young, he remained immature to the end."

What matters for contemporary American readers is Townshend's 14-year grievance against American legislatures which seem to have originated when he discovered the New York Legislature in 1754 up to its old tricks of refusing to provide funds for Royal initiatives it did not like. At the time, he was in his first public office, the Board of Trade and Plantations, and had written some highly arrogant orders to New York, making many high-handed and disdainful public asides to his friends, including his wish to have the Assembly cut out of appropriations except for token approval of them. He was young, so his wiser party colleagues simply deflected him. But by 1767 he was Chancellor of the Exchequer, a brilliant speaker, and no doubt had collected many political chits to be cashed in. The Townshend Taxes were enacted, his underlying personal grievances were well known, the colonial assemblies could see it meant big trouble.

Although almost no one could match Townshend for bizarre behavior, in Philadelphia at Front and Market Streets, there was another difficult personality, named William Bradford. As a printer and newspaper publisher, Bradford must have been a person of some note in a town of thirty thousand, but it is difficult to find a portrayal of him, and notes about his personal life are comparatively skimpy. We do know that he was a member of a family of newspaper printers, including grandfather, uncle, and son, all of whom had experienced official prosecution for defiance of government. His grandfather, also named William Bradford, is said to have had Quaker affiliation, but it is not particularly prominent in accounts of him, while almost no mention of Quaker affiliation is made of the rest of the family. Grandfather William had a notable apprentice named John Peter Zenger, who was prosecuted for libel against the Royal Governor of New York, defended in a famous trial by the Philadelphia Lawyer Andrew Hamilton, who established the principle that the truth is not a libel. We can rather safely presume that the younger William Bradford had grown up in an environment of hostility to authority, aggravated but not necessarily caused by some rather plain persecutions by authority. It may even have been specific hostility to British authority, since in 1754 young Bradford began publication of a specifically anti-British paper, The Weekly Advertiser. It is interesting to note that its principle competitor was a pro-British paper printed by Ben Franklin. Somewhere along the line, Bradford became head of the Sons of Liberty, clearly marking him as strongly anti-British, probably well before the Townshend Acts.

Bradford established the London Coffee House at Front and Market Streets in Philadelphia. That might seem a strange sideline for a printer, until you reflect that the location was right beside the waterfront, especially the Arch Street warf. Newspapers in those days almost never had professional reporters, depending for their content on gossip from visiting ships. A coffee shop near the waterfront would be an excellent place to hear the maritime news of the world, and possibly hear it sooner than competitors. The London Coffee House provided a place for bargaining and trade; the Maritime Exchange got its start there. It may or may not be significant that a main activity of the Exchange was to buy and sell slaves. It is sure that the Navigation Acts and the Townshend taxes on various imports were a central topic of angry discussion in a waterfront Coffee House from 1768 to 1776. Thus it is possible that Bradford was caught up in the excited opinions of his customers, but plenty of evidence of anti-British sentiment exists in his background to suppose he nursed a long-standing prejudice against the British government. Our most authoritative account of the events appeared in the Pennsylvania Packet of January 3, 1774, but the beginnings of the story were better related in the Pennsylvania Mercury of October 1, 1791, shortly after Bradford's death.