2 Volumes

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

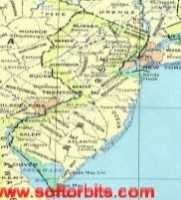

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Particular Sights to See:Center City

Taxi drivers tell tourists that Center City is a "shining city on a hill". During the Industrial Era, the city almost urbanized out to the county line, and then retreated. Right now, the urban center is surrounded by a semi-deserted ring of former factories.

West Fairmount Park

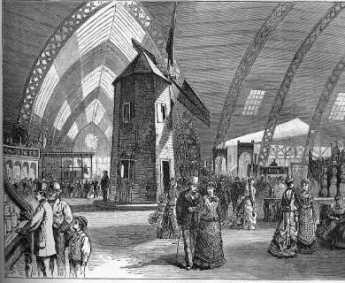

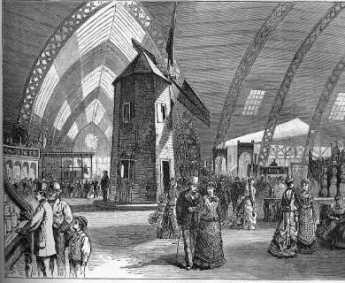

Fairmount Park is considerably larger on the west bank of the Schuylkill than on the east, and the points of interest are somewhat more diluted by woods and pasture. Partly, that is a consequence of being the site of the 1876 Centennial Exhibition , and partly that urban growth had not encroached so much into the farmland at the time the park was created. On the west bank at the time of the Revolution, there were still 300-400 acre farms, whereas the east bank farms had been cut up into gentleman's

|

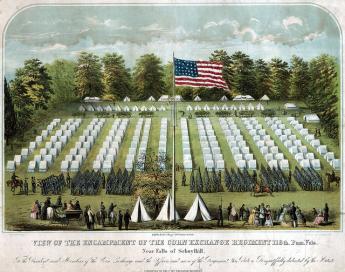

| Centennial Exhibition |

estates. The Schuylkill takes two 90-degree turns within the Park limits, leaving a point of high land on either side of the river. On the east side, the East Park reservoir is at the apex, and on the west side, the dominant point is Belmont Mansion. For a while, there was a restaurant at Belmont, but at the moment it's a pity but little advantage is taken of a very scenic view. Two judges once lived in the mansion, William Peters, and his nephew Richard Peters. William was a Tory and had to flee to England. Richard made a better guess and as a rebel, therefore could live on in scenic splendor.

For orientation, the West Park mansions extend in an arc from The Solitude in the south to Chamonix in the north. For the moment limiting our list to houses present when the Park was created, there is Sweetbrier, The Pig-Eye Cottage, Belmont, Ridgeland, Greenland, and the Lilacs. The last three houses belonged to three well-known Philadelphia families, Garrett, J.B. Lippincott, and Walnut, who established themselves in 19th Century commerce rather than 18th Century politics. Sweetbrier was one of those centers of French Philadelphia, when Samuel Breck continued his father's close relationship developed as the fiscal representative of French Forces in America, entertaining LaFayette and other such friends of the new Republic. The Pig-eye cottage is used by the Park administration, and closely resembles the Caleb Pusey house, but otherwise has no remarkable history. Solitude, on the other hand, really was the retreat for John, then Richard, then Granville. John Penn entertained George Washington here while he was presiding over the Constitutional Convention.

|

| fair |

Fairmount Park is notable for some buildings which are unfortunately no longer there, and some other buildings that were transplanted there. The East Park is a historical monument, while the West Park is more a house museum. Governor Mifflin's house is gone from the Falls area, Powelton is gone, and Lansdowne the estate where the Proprietor John Penn was seized by rebel soldiers. His family was later paid less than a penny an acre for the 21 million acres of Pennsylvania land they clearly owned. Sedgley is also gone, and all of these places have a place in history. On the other hand, it is well to remember that all of the industrial slums along the river were cleared away to be replaced by the charm of Boat House Row.

|

| Exhibition |

It keeps being repeated that Fairmount Park is the largest urban park in America, but the fact is it is bigger than the city can afford to maintain, just as a monument to the colonial style of life. It was a grand place to have a World's Fair in 1876, and Memorial Hall remains, along with the Japanese pavilion, a truly priceless reproduction of Japan under the Shogun. Fairmount Park has the first Zoo in America, still a place of note in zoological circles, and many ballparks, summer music halls, and other modern recreational attractions. It contains Cedar Grove, a splendid Quaker homestead in Welsh style, transported from its original location in Frankford. The Letitia Street House was too fine an example of 17th Century urban architecture to lose, so it was moved to the Park from Letitia Street, approximately 2nd and Market Streets. William Penn lived for a while on Letitia Street, named after his daughter, but it is not entirely clear who lived in this particular little house. There doesn't seem to be anything you can do about people calling it the William Penn House.

Fairmount Park is the largest urban park. It doesn't have roley coasters, but we don't miss them, and it doesn't have Mickey Mouse, at least so far. There is absolutely nothing like it anywhere. Anyway even if there were, Philadelphians wouldn't notice.

Fair Mount

|

| THE FAIRE MOUNT |

Although the Art Museum now dominates the end of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, the earlier focus of the acropolis once called Fair Mount is just down the hill behind it, in the old Grecian complex of the Philadelphia waterworks. When the Schuylkill was dammed at that point, the effect was to calm the rapids, drown the falls at Midvale Avenue upstream, and turn this portion of the river into a placid fresh-water lake. Fairmont Park was then created upstream in an effort (originally stimulated by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia) to reduce pollution of Philadelphia's water supply going into the pumps at the Waterworks, by replacing, with parkland, the wards, and industrial slums at the terminus of the canal bringing anthracite from upstate. The result was the creation of an ideal place for public boating and skating.

The transformation of this area can be seen in retrospect as an impressive civic response to economic upheaval. The War of 1812 (by cutting off ocean access to bituminous via the Chesapeake) had first forced Philadelphia to use anthracite hard coal, and the discovery of anthracite's superiority in making steel caused a continuing reliance on it and the canals

|

| Philadelphia's Water Works |

that brought it here. By 1850, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad made the canals obsolete and created this splendid opportunity for urban renewal. The waterfalls had created a natural boundary between industry oriented to upstate coal and other industry oriented to oil and commerce coming up Delaware. It is a great pity that the lower section of the Schuylkill, once so famously beautiful, has never stimulated the same vision and imagination in response to the eventual decline of the industrialization which defaced it.

To return to Boathouse Row, a large azalea garden starts the Park, and then the East River Driver winds along the attractively landscaped riverbank. Just beyond the azalea garden, the first of ten Victorian-style boathouses starts the home of the Schuylkill Navy, an association of rowing clubs which are now a century and a half in residence there. When the Schuylkill auto expressway was created on the other side of the river, someone had the bright idea of decorating the rowing houses with lights along their edges in the manner used for Christmas decorations in South Philadelphia, especially on Smedley and Colorado Streets. Ever since the entrance to Philadelphia from the West has become one of its most arresting beauties.

|

| BOATHOUSE ROW |

Add a few cherry blossom trees in the spring, and you have quite a memorable centerpiece. Rowing sometimes called crewing, or sculling, is a central focus of Philadelphia society, and is curiously not something in which the city can claim to be first or the oldest. As you might expect, "regatta" is a word invented in Venice five hundred years ago, there are records of rowing races as far back as 400 BC, and New York -- ye Gods! -- had the first American boating club. The Philadelphia Schuylkill Navy was formed as an association of rowing clubs in 1858, and the oldest member, the Bachelor's Barge, was only formed in 1856. The development was largely spontaneous and is said to have been briskly stimulated by a beer garden nearby, run by a former Philadelphia sheriff. About the same time, the British became crazy about the sport, having the Henley Races as the most famous regatta in the world, and both the Australians and the Bostonians occasionally have the largest, most expensive, most widely advertised regattas. Foo. Philadelphia has the Schuylkill Navy, and it is central to our existence.

There are a couple of things which are unique about rowing. In the first place, it is hard to think of a way to cheat. You can hire engineers to redesign the shape and size of your boat, but engineering really doesn't make a lot of difference once the basic development of oarlocks and movable seats was perfected. A good boat can cost as much as $30,000, but that is large because all boats approach the limit of speed. If you have heavier or stronger oarsmen, it doesn't make that much difference. What matters is coordination, and in the longer boats, teamwork. Pull up with your shoulders, push with your legs, don't start with your buttocks, the art of rowing involves your whole body. The greatest champion of all time, Edward "Ned" Hanlan,

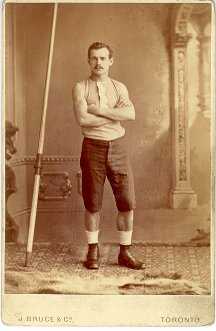

|

| EDWARD HANLAN |

only weighed 155 pounds. Not only was he world champion from 1876 to 1884, he was undefeated in any race during the last four years. True, he was born in Toronto, and eventually he was thrown out of polite Philadelphia racing for deliberately ramming another boat, but those are private Philadelphia comments, not something you want to talk too much about. The whole secret of rowing is to manage the fact that the boat travels farther between strokes than while the oars are in the water; if you row too fast, you actually slow the boat. There are two other Philadelphia names associated with the Schuylkill Navy. One is Thomas Eakins, the great American painter, one of whose most famous pictures is that of Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (on the Schuylkill). The other name is Kelly.

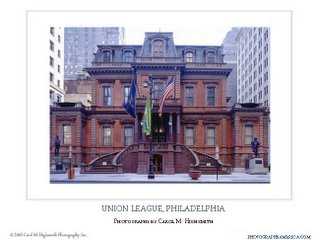

John B. Kelly of Philadelphia won two Olympic gold medals in 1920 and did it within one hour. He won a Third Olympic gold medal in 1924. But when he tried to race in the Henley Regatta, he was declared ineligible to row, because he had worked with his hands (summer work as a bricklayer), and thus could not really be called a gentleman. Anyone who has ever heard Irishmen talk about Englishmen can imagine the reaction this caused in the Kelly family. The resentment took the form of pushing his son, Jack, into racing, and in 1947 John B. Kelly, Jr. won the Diamond Sculls at Henley. Meanwhile, the father vindicated himself in other ways. The firm of Kelly for Brickwork was an enormous financial success, right up there next to Matthew H. McCloskey and John McShain, the political builders of the Pentagon and numerous other government buildings. John B. Kelly unsuccessfully ran for Mayor of Philadelphia in 1935 during the 75-year period when Philadelphia Mayors were always Republicans, but for decades was in the much more powerful position of head of the local Democratic party. The Republicans at that time would meet for lunch at the Union League, and so John Kelly reserved a lunch table at the Bellevue Hotel, next door, where he could be seen holding court every day.

|

| John B Kelly |

The result was not entirely favorable for the Bellevue; more than one wedding reception was rescheduled to some other hotel in order to avoid the Democrat taint. But you always knew where you could find Kelly at lunch, and it was fun to watch the various minions come forward to the table, almost as if they were in chains, to pay homage which involved provoking loud laughter from the great man with a salacious joke. The rowing clubs are mostly big barns with old boats high up on the walls, and silver cups and wooden memorial plaques lower down. They have lockers and showers, but no dining rooms, except at catered in the evening for parties. For a century, no women came there, but now almost half of the rowers are female. Membership is not difficult to obtain, although you have to be good to get on the club teams, and the dues are not expensive. If you show promise, you are expected to spend most of your waking hours working at it. Jack Kelly was famous for rowing three hours every morning, going to lunch, and then coming back for a couple of hours of more rowing. That doesn't leave much time in your life for anything else, so the friendships developed among active club members are very strong, just like the horsemen over at the City Troop. They sort of life in the past a little, with many anecdotes about a skull that broke apart and sank in the midst of a race, or a race that was lost because of too much recreation the night before. The lingo has to do with the fine points. A race can be between "eights" or "fours", or doubles, or singles. It can have a coxswain, or not, and be coxed or unboxed. When a pair of rowers have two oars apiece, it is the normal arrangement. A much more difficult boat to control has two rowers, with one oar apiece. Like Hercules or Achilles, stories are told of Hanlan, great Hanlan, who sometimes would win a one-mile race by eleven lengths. Or who would get so far ahead of his competitors that he would lie down in the boat and wait for another boat to catch up -- and then race ahead to beat him. This sort of person can be a little hard to take, and it is privately muttered that Hanlan was sent off to Australia, where people do that sort of thing more commonly.

Widener, Stotesbury, and Trumbauer

Gerry McFadden devoted most of his short life to researching the history of Philadelphia clubs, but illness kept him from publishing much of it. Walton van Winkle has apparently taken up the role of club historian for the city, and much that survives to be known comes to us from them. For which we all ought to be grateful.

|

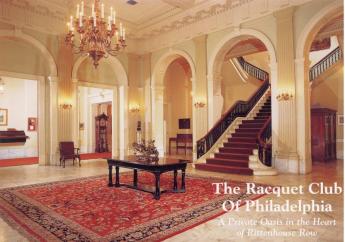

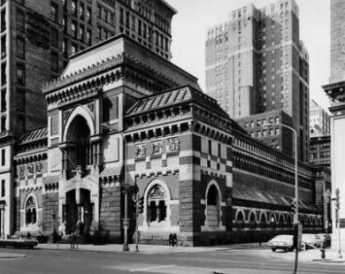

| Racquet Club |

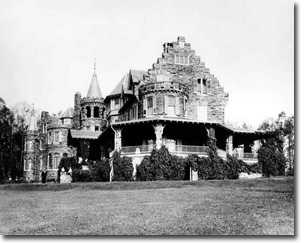

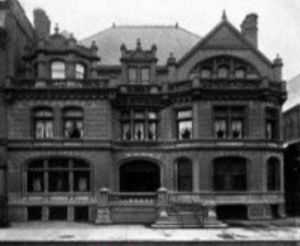

The Racquet Club was once located at 9th and Walnut, just three blocks from the debtors prison at 6th and Walnut where the game of squash racquets is said to have originated. In 1906 it was decided to build a new club at 16th and Chancellor Streets; that did come to pass, largely because of three members. Henry Widener had taken a small inherited fortune and blown it up into a large personal fortune by monopolizing the trolley business in town. Edward T. Stotesbury, a much younger man, had ascended to the Presidency of Drexel and Company, in affiliation with J. P. Morgan. Both of these tycoons had built awesome mansions in the suburbs, one called Whitemarsh for where it was located, and the other called Lynnewood, on the grounds of what is now a huge apartment complex at the north end of Broad Street.Horace Trumbauer was the architect for both of these palaces, bringing together two men of considerably different age and personality. The conviction grew that Philadelphia needed a really first-class athletic club, and in 1906 it got built. Architect Trumbauer saw the whole design as related to the terrifying weight of the swimming pool full of water, and the indoor tennis courts, faced with thick slabs of slate. Builders who understand these things are impressed with the concept of a central tower to carry the internal weight of the building. The whole internal guts of the place are supported by steel girders of the type used to build bridges, ultimately resting on holes in the bedrock drilled 26 feet deep. If someone comes our way with an atom bomb, this is a good place to be a member.

The Racquet Club has one of the four or five Court Tennis areas in America, an interesting thing to look at, although the rules of the actual game are as baffling as those of cricket.

Another notable sight is the men's dressing room, wood-paneled and luxurious enough to be the scene of several movies. The shower heads, in particular, dump hot water on you like a Turkish Bath.

The Racquet club was always primarily for young men and tended to be a little raucous. It used to be said that almost anybody could be admitted -- you can take that for what it is probably worth -- but then the young members were carefully observed for their behavior, particularly in whom they married. If they seemed to be the right sort, they could then be invited into the Rittenhouse or the Philadelphia Club.

Market Street, East (2)

|

| The Reading Terminal Market |

We are about to look at a remarkable a fourteen-block stretch of street, with several unifying historical themes, but there is one notable feature which stands by itself. The PSFS building is now the site of a luxury hotel, but it once housed the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society, the oldest savings bank in the country, having been founded in 1816. Setting aside the place of this the institution in American finance, and passing quickly by the deplorable end of it with swashbuckling corsairs in three-piece suits, 1929 the building itself remains so remarkable that the hotel still displays the PSFS sign on its top. The imagination of the architects was so advanced that a building constructed seventy-five years ago looks as though it might have been completed yesterday. The Smithsonian Institution conducts annual five-day tours of Chicago to look at a skyscraper architecture, but hardly anything on that tour compares with the PSFS building. From time to time, someone digs up old newspaper clippings from the 1930s to show how the PSFS was ridiculed for its odd-looking the building, but anyhow this is certainly one example of how the Avante the guard got it right.

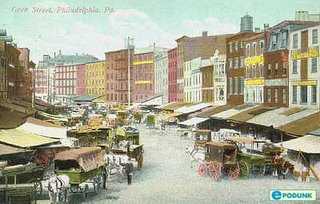

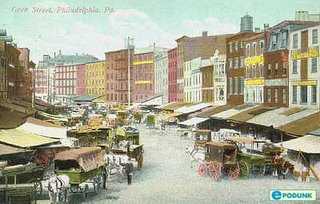

At the far Eastern end of Market Street, right in the middle of the street once stood a head house, which in this case was called the market terminal building

. In those days, street markets were mostly a line of sheds and carts down the middle of a wide street, but usually there was a substantial masonry building at the head of the market, where money was counted and more easily guarded. An example of a restored ahead house can today be found at Second and Pine, although that market ("Newmarket") was less for groceries than for upscale shops. The market on Market Street started at the river and worked West with the advancing city limits, making it understandable that buildings which lined that broad avenue gradually converted to shops, and then stores. The grandest of the department stores on Market Street was, of course, John Wanamaker's, all the way to City Hall, built on the site of Pennsylvania Railroad's freight terminal (the passenger terminal was on the West side of City Hall). In the late Nineteenth Century, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Reading Railroads terminated at this point, so rail traffic flowing east merged with ocean and river traffic flowing west. Well into the Twentieth Century, a dozen major department stores and hundreds of specialty stores lined the street, with trolley cars, buses, and subway traffic taking over for horse-drawn drainage. The the pinnacle of this process was the corner of Eighth and Market, where four department stores stood, one on each corner, and underneath them three subway systems intersected. The Reading terminal market is Philadelphia's last remnant of this almost medieval shopping concept, although the Italian street markets of South Philadelphia display a more authentic chaos. Street markets, followed by shops, overwhelmed by department stores showed a regular succession up Market Street, and when commerce disappeared, it all turned into a wide avenue from City Hall to River, leaving few colonial traces.

The history of Market Street is the history of the Reading Terminal Market. Farmers and local artisans thronged to sell their wares in sheds put up in the middle of the wide street, traditionally called "shambles" after the similar areas in York, England. Gradually, elegant stores were built on the street, and upscale competitors began to be uncomfortable with the mess and disorder of the shambles down the center of the street. By 1859 the power structure had changed, and the upscale merchants on the sidewalks got a law passed, forbidding shambles. After the expected uproar, the farmers and other shambles merchants got organized, and built a Farmers Market on the North side of 12th and Market Relative peace and commercial tranquility then prevailed until the Reading Railroad employed power politics and the right of eminent domain to displace the Farmer's Marketplace with a downtown railroad terminal that was an architectural marvel for its time, with the farmers displaced to the rear in the Reading Terminal Market, opening in 1893. Bassett's, the ice cream maker, is the only merchant continuously in business there since it opened, but several other vendors are nearly as old. The farmers market persisted in that form for a century until the City built a convention center next door. As a result, the quaint old farmers market became a tourist attraction, with over 90,000 visitors a week. That's fine if you are selling sandwiches and souvenirs, but it crowds out meat and produces and thereby creates a problem. If the tourist attraction gets too popular, it drives out everything which made it a tourist attraction; so rules had to be made and enforced, limiting the number of restaurants, but encouraging Pennsylvania Dutch farmers. Competition and innovation are the lifeblood of commercial real estate, but they are always noisy processes. The history of the street is the history of clamor and jostling, eventually dying out to the point where everyone is regretful and nostalgic for a revival of clamor.

Market Street, East (3)

|

| James Madison |

But wait. At Ninth and Market Philadelphia had once built the White House or at least a mansion for the President of the United States. Secret deals between James Madison and Alexander Hamilton had agreed to move the nation's capital city to Virginia in return for nationalizing the states' Revolutionary War debts, although the circumstance which made it acceptable to the public had been the Yellow Fever epidemic. After that happened, no amount of logic or log-rolling was going to keep the government in this city. Philadelphia vainly built a very elaborate mansion for the President, but President Washington never occupied it, and it was converted to housing the University of Pennsylvania. That University eventually tore it down and replaced it with two somewhat more suitable buildings, meanwhile using the Walnut Street Theater and the Musical Fund Hall, at Ninth and Walnut and Ninth and Locust Streets respectively, for commencement exercises and the like. No one can be completely certain, but it is felt by many that 9th and Market was the general area where Benjamin Franklin had flown his famous kite. This definitely later was the site of Leary's second-hand bookstall, which had the remarkable history that it was once run by a former Philadelphia mayor. Ninth and Market Street is now the site of a Post Office on one corner and a vacant lot on the other. But let the imagination wander a little, and see Ben Franklin, The White House, the University of Pennsylvania, and a former mayor tending a bookstall.

There is a restoration of the house, the very house, where Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence at the corner of 7th and Market. Although hidden among the hulks of former department stores, some idea of the former elegance of the area is given by the description of stir raised by that rich young Virginian arriving in Philadelphia for the Continental Congress with his fancy carriage, team of horses, and several footmen. All of that colonial splendor has just about vanished in a sea of Victorian commercial architecture, which has in turn become merely a quaint relic. Over the front door of what was Lit's Department Store is still to be seen the mystifying motto, "Hats trimmed free of charge.", and today almost no one knows what that meant. At Sixth and Market, however, look out. The National Park Service brings colonial history crashing across Market Street, with tourists, a vista of Independence Hall, and lots of federal money. Dare we mention pork barrels? The whole subject of Independence National Park is so huge we must return to it several times, but just glance as you go through from City Hall to Penn's Landing.

Notice in particular the corner of Sixth and Market, where the real White House really stood. Robert Morris once had a mansion there, which Benedict Arnold occupied for a while after he was in charge of recovering Philadelphia from the British occupation, and subsequently both Washington and then John Adams lived there, as Presidents. Unfortunately, a fire took it away around 1830, and the remains were covered with trashy commercial buildings for decades, until the Park Service built a big public restroom there, now torn down. The current public furor about this site is truly remarkable, and the ample amounts of federal money our Senator has been able to obtain from the Appropriations committee on which he sits is probably a big factor in attracting interest. The main focus of dispute has to do with the fact that President Washington brought eight black slaves with him, and although he hastened to replace them with white indentured servants whose civil rights were probably no greater than slaves, the black slaves undoubtedly had to have lived somewhere. A search is on for the real, the true, the authentic slave quarters, as a suitable place for a public monument to their service to the country. The Park Service has a long reputation for defending scholarly standards, and its reluctance to accept archaeologically evidence of the slave quarters has brought down on their heads the furious response of the black community and the politicians seeking their favor. None of these latter groups can see any sense to quibbles about the precise location of Washington's outbuildings, just put up the monument, but for a while, it looked as though the scholars were determined to go down with their flags flying.

Several blocks further East, Market street comes to the brow of what was a cliff overlooking the Delaware, where the earliest settlers lived in temporary caves while they built houses. At the corner of Front and Market, from 1702 to 1883, stood the London Coffee House; during the Continental Congress, it was a place of high intrigue. The trolley lines once made a loop at the bottom of the hill at the river. Prior to that time, horse trolleys had to stop at the top of the hill at Front Street because the hill was too steep for them. At the lower level on the waterfront, there was a terminus for the ferry from New Jersey, bringing commuters, shoppers and farm produce from the Garden State. In time, a subway was built down Market Street, taking a sharp turn at the brow of the hill and heading off toward Frankford and the far northeastern parts of the city. The conjunction of the trolleys, the subway, and the ferries brought throngs of shoppers, mixing with other crowds emerging from three subways at 8th Street, still others from two train stations at 13th Street, and trolleys or buses at every one of the fourteen cross streets. This fourteen block strip was surely a great place to sell dry goods. But today, with the ferry terminal gone and the trolleys vanished, it is mainly a question whether the foot of the hill at the Delaware River is destined to become a museum or an amusement park.

Free Quaker Meetinghouse

|

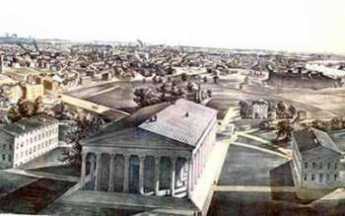

| Independence Hall |

Until this year, there was a Beautiful Mall stretching north from the State House (Independence Hall) to the approaches of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Concealing an enormous parking garage underneath it, the surface looked like a several-block lawn lined with flowering trees in the spring, framing the beautiful Eighteenth Century building (just as the mall in Washington leads up to the Washington Monument.)

Stretching from Independence Hall east to the Delaware River is another mall filled with historical buildings like Carpenters Hall , the First Bank(Girard's) and Second Bank (Biddle's), the Old and the New Custom houses, the American Philosophical Society, and others. The eastern mall was the property of the State of Pennsylvania when it was created, but it soon seemed more economical to the frugal rural legislature to turn it over to the federally funded National Park Service, joining the mall stretching northward. Well, somebody got another ton of federal money appropriated, and now we are filling the north mall with buildings which largely hide Independence Hall from the passersby. With just a few more Congressional earmarks, the imposing beauty of the mall will be submerged, but it hasn't quite reached that point yet. There is a perfectly enormous New Visitors Center, containing a couple of auditoriums and a big bookstore. Mostly the concept seems to be to provide a place to get out of the rain if you are an out of town visitor, provide public bathrooms, and a place to get a hot dog. At least the visitors center is red brick, and arched, with white woodwork. At the far northern end is an overwhelming stark granite block of a building, which will open July 4, 2003. It is a Constitution Center, claimed to be an interactive museum, and we shall see what we shall see. The looming monolith overwhelms and blocks the view to Independence Hall, and it better be good, when the insides get finished.

|

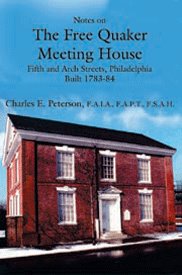

| Free Quaker Meeting |

If Independence Hall, which after all is a block long, is overwhelmed by the new constructions, the Free Quaker Meeting is totally hidden. This perfectly charming Eighteenths Century Quaker meetinghouse is just across Fifth Street from Benjamin Franklin's Grave, and just across Arch Street from the Constitution thing, completely in its shadow. Charles E. Peterson designed the restoration of the building, which had been added to and detracted from, over the years, but you can be sure its interior is now both beautiful and authentic. Before you go in, notice the inscription on the plaque under the northern eaves:

By General Subscription for the FREE QUAKERS. Erected in the Year of OUR LORD 1783 and of the EMPIRE 8.

The Quakers who built this building seem to have thought they were part of a new empire, but that implies an emperor, and of course, one was never created. Three years after the dedication of this building the Constitutional Convention met in the same Independence Hall, and our national form of government was somewhat strengthened from the Articles of Confederation also written here. Benjamin Franklin had a hand in both documents, but the first one was mainly composed by John Dickinson, and the second one by James Madison. If you go into the Free Quaker building, it seems to be a single large room with an interior balcony, and a couple of small staircases in the back leading down to what would presumably be restrooms. As a matter of fact, the Park Service extended the basement to include kitchen and dining room, and several offices for themselves which are a surprise if you are allowed to go down to see them.

|

| History of Free Quakers |

Charlie Peterson wrote a book about the restoration, but the main book about the spiritual history of this group was written by Charles Wetherill. Quakers, as everyone ought to know, are pacifists. The American Revolution put a number of them in a quandary because they agreed that Great Britain was injuring their rights by denying them a representative in the Parliament which ruled them but resorting to violence was another matter entirely. Eventually, a group did break away from the main Quaker church to fight for independence. They were prompt "readout of the meeting", the equivalent of being excommunicated, not allowed to worship in the regular meeting houses they had helped finance or to be buried in the church graveyards. Samuel Wetherill was one of the leaders of this group, just as his descendants are the most active today in the surviving historical society. Samuel created quite a furor, demanding to use the Orthodox meeting house and burial grounds. He was, in his own view, just as much a Quaker as the others since no doctrine is absolutely fixed in that religion, and was freely entitled to speak his mind to persuade others of the rightness of his sincere positions. The main body of Quakers would have none of it, and the Free Quakers were firmly expelled, forced to hold a public subscription and build their own meeting house. Wetherill of course personally knew every one of the members who expelled him, and there may be some truth to his loud, pointed and unchallenged contention that the true division was not between pacifists and fighters, but between Tories and advocates of Independence. Whatever the truth of these accusations, it does seem in retrospect that the split was fairly divided between wealthy established merchants, and small shopkeepers and artisans. Quite a few now-famous names appear on the rolls of the Free Quakers, like Timothy Matlack the actual Scribe of the Declaration of Independence document, Biddles, Lippincott, John Bartram,Crispins, Kembles, Trippes, and Wetherills. When the meeting had dwindled down in 1830 to two lone parishioners, one was a Wetherill, and the other was Betsy Ross, herself.

A comment is submitted by a reader:

I think your description of the Free Quakers oversimplifies their origins. It is true that Samuel Wetherill was disowned by Friends for his military activities. However, other Free Quaker leaders were bounced -- often years before the Revolution -- for other reasons. Timothy Matlack, for not paying his debts. Betsy Ross, for an improper marriage. Christopher Marshall, for counterfeiting. I haven't traced everyone listed as a member in the (1907?) Stackhouse history of the Free Quakers. But I did search in Quaker records for perhaps a dozen and found no records that people with those names had ever been Quakers. I think it would be more accurate to say of the Free Quakers that the Revolution drew together people of many different types and that when some of those people had things in common -- such as Quaker background -- they united around those things. (Posted by Mark E. Dixon )

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (2)

|

| Art Museum |

There are a number of residential relics along the Parkway, but in general the idea seems to have been to put governmental buildings there, in a sort of French-like celebration of governmental glory. There is the Youth Study Center, the Department of Education administration building, the Boy Scouts of America, the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, and of course the tower of City Hall at one end and the Parthenon-like Art Museum at the other. But this is Philadelphia, and certain small touches of the town are tucked among the European grandee design.

For example, WFLN (now WWFM) the original FM classical music station, had its studio tucked in a little building just behind the Cathedral. Ralph Collier would interview authors and city visitors there during the lunch hour, in a studio that was little more than a closet, while someone else changed records in a room downstairs. Somebody from New York once said that Ralph didn't seem to know how good he really was, which is a way New Yorkers like to talk. Ralph was, the just about the only interviewer who had actually read your book before the interview. In 1997, WFLN was sold for forty million dollars, which ought to impress even a New Yorker.

Logan Circle is bigger than it looks, primarily because the windows are set 100 feet high. This came about after the anti-catholic riots of the Civil War era, which made it advisable to put stained glass higher than most people can throw rocks. There is usually a cardinal in residence at this cathedral, and Cardinal Bevilacqua the much-respected lawyer-cardinal is now just retiring in favor of an incoming occupant from St. Louis. Cardinal Krol was famous in the past for his opposition to Pope John's Vatican Constitution, which he refused to allow to be translated into English. Before that, was Cardinal Dougherty, who is remembered for being considerably overweight. Cardinals are addressed as Your Eminence, and Cardinal Dougherty was (very privately) referred to as You're Immense. He was perhaps most famous for the Legion of Decency , an effort to make motion pictures more socially acceptable. The story is told of a 12-year-old girl who stood up and told the Cardinal that she didn't agree with him, she liked movies. The next day, her father, the most powerful Catholic banker in Philadelphia, had to go to the Cardinal and humble himself to make amends.

|

| Amelia Earhart |

Franklin Institute was originally on 7th Street, where the Atwater Kent Museum of Philadelphia History is now located. Much of the money to build it came from a $5000 bequest from Franklin himself, which was intended to demonstrate the power of compound interest over a period of time. It is part science museum, part memorial to Philadelphia's most famous citizen. It has a Planetarium, locomotive, a passenger airplane, Amelia Earhart's plane, a huge replica of a human heart, and thousands of working demonstrations of electrical phenomena. Ben Franklin's huge statue sits in a grand marble rotunda, where socialites occasionally hold receptions and weddings. But between the two extremes is the most interesting combination of museum and memorial -- a series of demonstrations of Franklin's most important scientific discoveries, utilizing the same instruments he used. Just a little effort at understanding these exhibits will convince any educated adult that Franklin was truly a genius.

Almost next door to the Franklin Institute is its more venerable neighbor, the Academy of Natural Sciences. The Academy is an offshoot of the American Philosophical Society, itself (originally founded by Franklin) and has a distinguished history of discovery and research of its own making, not merely a display of the work of others. Most school children will recognize the famous display of dinosaurs, including the First Dinosaur ever unearthed intact (in Haddonfield).

|

| Art Museum |

The Art Museum was intended to inspire awe, and it does. The builders ran out of money before the decorative friezes could be completed, but that even enhances its resemblance to the Parthenon, where the friezes were blown off in various wars. It's a little hard to know how to respond to the criticism that the building overwhelms its contents. Perhaps it is true that the creaking floorboards in Madrid's Prado Museum show off the treasures on its walls, but there is also little doubt that Spain (or Boston) would replace the floors if it could afford to. Although the City of Philadelphia has a little trouble finding the money to maintain and guard the Museum, the masonry is ultra-solid, it's very big, and will endure for ages to come. The collections slowly grow, benefaction by benefaction. The traveling exhibits are clearly the center of Philadelphia culture. And there, at the top of the stairs without any clothes on, is Diana of fame and fable. Her perfectly straight back is the true essence of the famously beautiful Philadelphia woman, like Fannie Kemble, Rebecca Gratz, Evelyn Nesbitt,Cornelia Otis Skinner, Grace Kelly, and Katherine Hepburn.

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

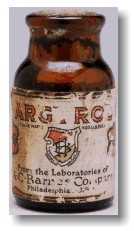

| A bottle of Argyrol |

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |

Since the Foundation is currently strapped for ready cash, Judge Stanley Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court is now being urged to allow the Foundation to break Barnes' will in some way or other. Move the museum to downtown Philadelphia where it can attract more paying visitors. Sell some of that land. Sell some of those paintings in the cellar. Fire some of those employees. But all of these suggestions are short-term solutions, which may injure the long term. Everybody has an idea of what Barnes the rich eccentric would have done if he were alive to do it, but I suspect he would have rejected the whole lot. Barnes the shrewd investor would have taken the most expensive painting off the wall, and sold it to the highest bidder. Buy low, sell high, and the niceties of non-profit professionals are damned. Barnes wasn't in love with one single painting, or one particular school of painterly interpretation, he was in love with Art.

Investment theory has improved in the past fifty years; there have even been some Nobel prizes awarded for new insights. But it still isn't possible to put an investment portfolio on autopilot for perpetuity. Every museum, university, and the foundation has the same problem, with the result that the landscape is littered with the bones of perpetual organizations destroyed by following a fixed formula. With the singular success that Barnes displayed, it isn't surprising that he went a little too far with instructing his successor trustees in what to invest in. Never sell the paintings or the real estate, avoid the common stock, were ideas that worked brilliantly, and may even work most of the time. But sooner or later, the institution will be endangered by following them too literally. Somebody has to have some flexibility. But there is something else that is inevitable, too. Sooner or later, whether it takes fifty years or five hundred years, sooner or later someone will be given the responsibility and the necessary flexibility -- but will try to run off with the boodle, for himself. The balance between necessary prudence and necessary flexibility is impossible to maintain forever, and the Judge will surely have a hard time deciding what Barnes would have decided.

American Philosophical Society

|

|

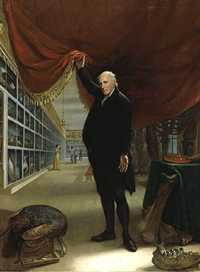

Charles Wilson Peale (1741-1827)

The Artist in His Museum 1822, Oil on canvas (The Joseph Harrison Jr. Collection) Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. |

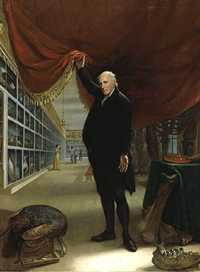

all of the red brick buildings on Independence Square look as though they were part of Independence Hall, but there is one exception. The building facing Fifth Street is Philosophical Hall, one of the four buildings of the American Philosophical Society. Right now, Philosophical Hall is used as a museum. It could be called the first museum in America, but not the oldest, because it had interruptions and different proprietorships. Charles Wilson Peale started his museum of curiosities there and then moved it to the second floor of Independence Hall, where he painted the famous portrait of himself holding up the curtain. In recent years, Philosophical Hall has again become a museum, holding treasures and curiosities belonging to the Philosophical Society itself. The docent is pleased to alternate between calling it America's new oldest museum, and America's oldest new museum. And, yes, the newell post has an Amity Button.

|

|

American Philosophical Society |

Patents were established by the Constitution when it was a piece of parchment lying on a table fifty feet away from here, and the early patent office required the submission of a working model of every application for patent. After a while, that got to be a lot of working models lying around, and many of the more interesting ones are on display in the museum. Like the model of Fitch's first steamboat or the gadget Jefferson used, to make simultaneous copies of documents he was writing. That's right near the Gilbert Stuart copy of Washington's portrait, and von Neumann's first algorithm to be stored in his stored program machine, or computer, and Neil Armstrong's speech on the moon, concerning one step for mankind and all. It's a splendid museum, full of the real stuff, in a handsome Georgian building with sparkling immaculate marble staircases.

|

|

John Fitch received a US Patent for the Steamboat August 26, 1791 |

In the Eighteenth Century, Natural Philosophy was what we now call science. That's why PhDs get a degree of Doctor of Philosophy when they study chemistry and physics. The idea for forming a scientific society in America apparently originated with John Bartram. As so often happens, the originator couldn't quite get it established and had to call on Ben Franklin that impression of publicity, to get it off the ground. To be fair about it, Franklin was probably the more distinguished scientist of the two. To be even more fair about it, the organization struggled a bit until Thomas Jefferson (that's the one who was President of the United States) gave it a real publicity shove. During the depths of the 1930s depression, one of the members left it several million dollars with the stipulation that the investments should focus on common stock. Since buying stock in 1935 was widely regarded as about the stupidest thing an investor could do, this little episode reinforced a strong impression that membership in the APS is given to people who are very smart, not merely famous. The four buildings, the many fellowships, and the big endowment were largely made possible by this contraries investment decision.

There are eight hundred members, of whom 93 have won Nobel Prizes. Over the years, two hundred members have been awarded Nobel Prizes, but you must remember that the organization existed for 150 years before there was such a prize. Several U.S. Supreme Court justices are members and lots and lots of people who are famous. The docent comments that they look pretty much like everyone else. There's a rumor that Bill Gates turned down the offer of membership, so now we will just see. He's young enough to have several decades' opportunity to reconsider an offer, although the APS might just be old enough to lack interest in any second chances.

Charles Dickens Doesn't Like Our Nice Penitentiary

In 1842, Philadelphia's Eastern Penitentiary was innovative and unique. It was an important tourist stop, especially for foreign visitors, and Charles Dickens naturally had to pay it a visit when he toured America in 1842. He didn't like it, and he said so, as follows :

In the outskirts, stands a great prison, called the Eastern Penitentiary: conducted on a plan peculiar to the state of Pennsylvania. The system here is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong.

In its intention, I am well convinced that it is kind, humane, and meant for reformation; but I am persuaded that those who devised this system of Prison Discipline, and those benevolent gentlemen who carry it into execution, do not know what it is that they are doing. I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers; and in guessing at it myself, and in reasoning from what I have seen written upon their faces, and what to my certain knowledge they feel within, I am only the more convinced that there is a depth of terrible endurance in it which none but the sufferers themselves can fathom, and which no man has a right to inflict upon his fellow-creature. I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body: and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay. I hesitated once, debating with myself, whether, if I had the power of saying 'Yes' or 'No,' I would allow it to be tried in certain cases, where the terms of imprisonment were short; but now, I solemnly declare, that with no rewards or honours could I walk a happy man beneath the open sky by day, or lie me down upon my bed at night, with the consciousness that one human creature, for any length of time, no matter what, lay suffering this unknown punishment in his silent cell, and I the cause, or I consenting to it in the least degree.

I was accompanied to this prison by two gentlemen officially connected with its management, and passed the day in going from cell to cell, and talking with the inmates. Every facility was afforded me, that the utmost courtesy could suggest. Nothing was concealed or hidden from my view, and every piece of information that I sought, was openly and frankly given. The perfect order of the building cannot be praised too highly, and of the excellent motives of all who are immediately concerned in the administration of the system, there can be no kind of question.

Between the body of the prison and the outer wall, there is a spacious garden. Entering it, by a wicket in the massive gate, we pursued the path before us to its other termination and passed into a large chamber, from which seven long passages radiate. On either side of each, is a long, long row of low cell doors, with a certain number over every one. Above, a gallery of cells like those below, except that they have no narrow yard attached (as those in the ground tier have), and are somewhat smaller. The possession of two of these, is supposed to compensate for the absence of so much air and exercise as can be had in the dull strip attached to each of the others, in an hour's time every day; and therefore every prisoner in this upper story has two cells, adjoining and communicating with, each other.

Standing at the central point, and looking down these dreary passages, the dull repose, and quiet that prevails is awful. Occasionally, there is a drowsy sound from some lone weaver's shuttle, or shoemaker's last, but it is stifled by the thick walls and heavy dungeon-door, and only serves to make the general stillness more profound. Over the head and face of every prisoner who comes into this melancholy house, a black hood is drawn; and in this dark shroud, an emblem of the curtain dropped between him and the living world, he is led to the cell from which he never again comes forth, until his whole term of imprisonment has expired. He never hears of wife and children; home or friends; the life or death of any single creature. He sees the prison-officers, but with that exception, he never looks upon a human countenance or hears a human voice. He is a man buried alive; to be dug out in the slow round of years, and in the meantime dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair.

His name, and crime, and term of suffering are unknown, even to the officer who delivers him his daily food. There is a number over his cell-door, and in a book of which the governor of the prison has one copy, and the moral instructor another: this is the index of his history. Beyond these pages the prison has no record of his existence: and though he lives to be in the same cell ten weary years, he has no means of knowing, down to the very last hour, in which part of the building it is situated; what kind of men there are about him; whether in the long winter nights there are living people near, or he is in some lonely corner of the great jail, with walls, and passages, and iron doors between him and the nearest sharer in its solitary horrors.

Every cell has double doors: the outer one of sturdy oak, the other of grated iron, wherein there is a trap through which his food is handed. He has a Bible, and a slate and pencil, and, under certain restrictions, has sometimes other books, provided for the purpose, and pen and ink and paper. His razor, plate, and can, and basin, hang upon the wall or shine upon the little shelf. Freshwater is laid on in every cell, and he can draw it at his pleasure. During the day, his bedstead turns up against the wall and leaves more space for him to work in. His loom, or bench, or wheel, is there; and there he labors, sleeps and wakes, and counts the seasons as they change, and grows old.

The first man I saw, was seated at his loom, at work. He had been there six years and was to remain, I think, three more. He had been convicted as a receiver of stolen goods, but even after his long imprisonment, denied his guilt, and said he had been hardly dealt by. It was his second offense.

He stopped his work when we went in, took off his spectacles, and answered freely to everything that was said to him, but always with a strange kind of pause first, and in a low, thoughtful voice. He wore a paper hat of his own making and was pleased to have it noticed and commanded. He had very ingeniously manufactured a sort of Dutch clock from some disregarded odds and ends, and his vinegar-bottle served for the pendulum. Seeing me interested in this contrivance, he looked up at it with a great deal of pride, and said that he had been thinking of improving it and that he hoped the hammer and a little piece of broken glass beside it 'would play music before long.' He had extracted some colors from the yarn with which he worked, and painted a few poor figures on the wall. One, of a female, over the door, he called 'The Lady of the Lake.'

He smiled as I looked at these contrivances to while away the time; but when I looked from them to him, I saw that his lip trembled, and could have counted the beating of his heart. I forget how it came about, but some allusion was made to his having a wife. He shook his head at the word, turned aside, and covered his face with his hands.

' But you are resigned now!' said one of the gentlemen after a short pause, during which he had resumed his former manner. He answered with a sigh that seemed quite reckless in its hopelessness, 'Oh yes, oh yes! I am resigned to it.' 'And are a better man, you think?' 'Well, I hope so: I'm sure I hope I may be.' 'And time goes pretty quickly?' 'Time is very long gentlemen, within these four walls!'

He gazed about him - Heaven only knows how wearily! - as he said these words; and in the act of doing so, fell into a strange stare as if he had forgotten something. A moment afterward he sighed heavily, put on his spectacles, and went about his work again.

In another cell, there was a German, sentenced to five years' imprisonment for larceny, two of which had just expired. With colors procured in the same manner, he had painted every inch of the walls and ceiling quite beautifully. He had laid out the few feet of ground, behind, with exquisite neatness, and had made a little bed in the center, that looked, by-the-bye, like a grave. The taste and ingenuity he had displayed in everything were most extraordinary; and yet a more dejected, heart-broken, wretched creature, it would be difficult to imagine. I never saw such a picture of forlorn affliction and distress of mind. My heart bled for him; and when the tears ran down his cheeks, and he took one of the visitors aside, to ask, with his trembling hands nervously clutching at his coat to detain him, whether there was no hope of his dismal sentence being commuted, the spectacle was really too painful to witness. I never saw or heard of any kind of misery that impressed me more than the wretchedness of this man.

In a third cell, was a tall, strong black, a burglar, working at his proper trade of making screws and the like. His time was nearly out. He was not only a very dexterous thief, but was notorious for his boldness and hardihood, and for the number of his previous convictions. He entertained us with a long account of his achievements, which he narrated with such infinite relish, that he actually seemed to lick his lips as he told us racy anecdotes of stolen plate, and of old ladies whom he had watched as they sat at windows in silver spectacles (he had plainly had an eye to their metal even from the other side of the street) and had afterward robbed. This fellow, upon the slightest encouragement, would have mingled with his professional recollections the most detestable cant; but I am very much mistaken if he could have surpassed the unmitigated hypocrisy with which he declared that he blessed the day on which he came into that prison and that he never would commit another robbery as long as he lived.

There was one man who was allowed, as an indulgence, to keep rabbits. His room having rather a close smell in consequence, they called to him at the door to come out into the passage. He complied of course and stood to shake his haggard face in the unwonted sunlight of the great window, looking as wan and unearthly as if he had been summoned from the grave. He had a white rabbit in his breast; and when the little creature, getting down upon the ground, stole back into the cell, and he, being dismissed, crept timidly after it, I thought it would have been very hard to say in what respect the man was the nobler animal of the two.

There was an English thief, who had been there but a few days out of seven years: a villainous, low-browed, thin-lipped fellow, with a white face; who had as yet no relish for visitors, and who, but for the additional penalty, would have gladly stabbed me with his shoemaker's knife. There was another German who had entered the jail but yesterday, and who started from his bed when we looked in, and pleaded, in his broken English, very hard for work. There was a poet, who after doing two days' work in every four-and-twenty hours, one for himself and one for the prison, wrote verses about ships (he was by trade a mariner), and 'the maddening wine-cup,' and his friends at home. There were very many of them. Some reddened at the sight of visitors, and some turned very pale. Some two or three had prisoner nurses with them, for they were very sick; and one, a fat old negro whose leg had been taken off within the jail, had for his attendant a classical scholar and an accomplished surgeon, himself a prisoner likewise. Sitting upon the stairs, engaged in some slight work, was a pretty colored boy. 'Is there no refuge for young criminals in Philadelphia, then?' said I. 'Yes, but only for white children.' Noble aristocracy in crime.

There was a sailor who had been there upwards of eleven years, and who in a few months' time would be free. Eleven years of solitary confinement!

' I am very glad to hear your time is nearly out.' What does he say? Nothing. Why does he stare at his hands, and pick the flesh upon his fingers, and raise his eyes for an instant, every now and then, to those bare walls which have seen his head turn grey? It is a way he has sometimes.

Does he never look men in the face, and does he always pluck at those hands of his, as though he were bent on parting skin and bone? It is his humor: nothing more.

It is his humor too, to say that he does not look forward to going out; that he is not glad the time is drawing near; that he did look forward to it once, but that was very long ago; that he has lost all care for everything. It is his humor to be a helpless, crushed, and broken man. And, Heaven be his witness that he has his humor thoroughly gratified!

There were three young women in adjoining cells, all convicted at the same time of a conspiracy to rob their prosecutor. In the silence and solitude of their lives, they had grown to be quite beautiful. Their looks were very sad and might have moved the sternest visitor to tears, but not to that kind of sorrow which the contemplation of the men awakens. One was a young girl; not twenty, as I recollect; whose snow-white room was hung with the work of some former prisoner, and upon whose downcast face the sun in all its splendor shone down through the high chink in the wall, where one narrow strip of bright blue sky was visible. She was very penitent and quiet; had come to be resigned, she said (and I believe her); and had a mind at peace. 'In a word, you are happy here?' said one of my companions. She struggled - she did struggle very hard - to answer, Yes; but raising her eyes, and meeting that glimpse of freedom overhead, she burst into tears, and said, 'She tried to be; she uttered no complaint, but it was natural that she should sometimes long to go out of that one cell: she could not help THAT,' she sobbed, poor thing!

I went from cell to cell that day; and every face I saw, or word I heard, or incident I noted, is present to my mind in all its painfulness. But let me pass them by, for one, more pleasant, a glance of a prison on the same plan which I afterward saw at Pittsburgh.

When I had gone over that, in the same manner, I asked the governor if he had any person in his charge who was shortly going out. He had one, he said, whose time was up the next day; but he had only been a prisoner two years.

Two years! I looked back through two years of my own life - out of jail, prosperous, happy, surrounded by blessings, comforts, good fortune - and thought how wide a gap it was, and how long those two years passed in solitary captivity would have been. I have the face of this man, who was going to be released the next day, before me now. It is almost more memorable in its happiness than the other faces in their misery. How easy and how natural it was for him to say that the system was a good one; and that the time went 'pretty quick - considering;' and that when a man once felt that he had offended the law, and must satisfy it, 'he got along, somehow:' and so forth!

'What did he call you back to say to you, in that strange flutter?' I asked of my conductor when he had locked the door and joined me in the passage.

'Oh! That he was afraid the soles of his boots were not fit for walking, as they were a good deal worn when he came in; and that he would thank me very much to have them mended, ready.'

Those boots had been taken off his feet, and put away with the rest of his clothes, two years before!

I took that opportunity of inquiring how they conducted themselves immediately before going out; adding that I presumed they trembled very much.

'Well, it's not so much a trembling,' was the answer - 'though they do quiver - as a complete derangement of the nervous system. They can't sign their names to the book; sometimes can't even hold the pen; look about 'em without appearing to know why, or where they are; and sometimes get up and sit down again, twenty times in a minute. This is when they're in the office, where they are taken with the hood on, as they were brought in. When they get outside the gate, they stop, and look first one way and then the other; not knowing which to take. Sometimes they stagger as if they were drunk, and sometimes are forced to lean against the fence, they're so bad:- but they clear off in course of time.'

As I walked among these solitary cells, and looked at the faces of the men within them, I tried to picture to myself the thoughts and feelings natural to their condition. I imagined the hood just taken off, and the scene of their captivity disclosed to them in all its dismal monotony.

At first, the man is stunned. His confinement is a hideous vision, and his old life a reality. He throws himself upon his bed and lies there abandoned to despair. By degrees, the insupportable solitude and barrenness of the place rouse him from this stupor, and when the trap in his grated door is opened, he humbly begs and prays for work. 'Give me some work to do, or I shall go raving mad!'

He has it; and by fits and starts applies himself to labour; but every now and then there comes upon him a burning sense of the years that must be wasted in that stone coffin, and an agony so piercing in the recollection of those who are hidden from his view and knowledge, that he starts from his seat and striding up and down the narrow room with both hands clasped on his uplifted head, hears spirits tempting him to beat his brains out on the wall.

Again he falls upon his bed, and lies there, moaning. Suddenly he starts up, wondering whether any other man is near; whether there is another cell like that on either side of him: and listens keenly.

There is no sound, but other prisoners may be near for all that. He remembers to have heard once, when he little thought of coming here himself, that the cells were so constructed that the prisoners could not hear each other, though the officers could hear them.

Where is the nearest man - upon the right, or on the left? or is there one in both directions? Where is he sitting now - with his face to the light? or is he walking to and fro? How is he dressed? Has he been here long? Is he much worn away? Is he very white and specter-like? Does HE think of his neighbor too?

Scarcely venturing to breathe, and listening while he thinks, he conjures up a figure with his back towards him and imagines it moving about in this next cell. He has no idea of the face, but he is certain of the dark form of a stooping man. In the cell upon the other side, he puts another figure, whose face is hidden from him also. Day after day, and often when he wakes up in the middle of the night, he thinks of these two men until he is almost distracted. He never changes them. There they are always as he first imagined them - an old man on the right; a younger man upon the left - whose hidden features torture him to death, and have a mystery that makes him tremble.

The weary days pass on with solemn pace, like mourners at a funeral; and slowly he begins to feel that the white walls of the cell have something dreadful in them: that their color is horrible: that their smooth surface chills his blood: that there is one hateful corner which torments him. Every morning when he wakes, he hides his head beneath the coverlet and shudders to see the ghastly ceiling looking down upon him. The blessed light of day itself peeps in, an ugly phantom face, through the unchangeable crevice which is his prison window.

By slow but sure degrees, the terrors of that hateful corner swell until they beset him at all times; invade his rest, make his dreams hideous, and his nights dreadful. At first, he took a strange dislike to it; feeling as though it gave birth in his brain to something of corresponding shape, which ought not to be there, and racked his head with pains. Then he began to fear it, then to dream of it, and of men whispering its name and pointing to it. Then he could not bear to look at it, nor yet to turn his back upon it. Now, it is every night the lurking-place of a ghost: a shadow:- a silent something, horrible to see, but whether bird, or beast, or muffled human shape, he cannot tell.

When he is in his cell by day, he fears the little yard without. When he is in the yard, he dreads to re-enter the cell. When night comes, there stands the phantom in the corner. If he has the courage to stand in its place, and drive it out (he had once: being desperate), it broods upon his bed. In the twilight, and always at the same hour, a voice calls to him by name; as the darkness thickens, his Loom begins to live; and even that, his comfort, is a hideous figure, watching him till daybreak.

Again, by slow degrees, these horrible fancies depart from him one by one: returning sometimes, unexpectedly, but at longer intervals, and in less alarming shapes. He has talked upon religious matters with the gentleman who visits him, and has read his Bible, and has written a prayer upon his slate, and hung it up as a kind of protection, and an assurance of Heavenly companionship. He dreams now, sometimes, of his children or his wife, but is sure that they are dead, or have deserted him. He is easily moved to tears; is gentle, submissive, and broken-spirited. Occasionally, the old agony comes back: a very little thing will revive it; even a familiar sound, or the scent of summer flowers in the air; but it does not last long, now: for the world without, has come to be the vision, and this solitary life, the sad reality.

If his term of imprisonment be short - I mean comparatively, for short it cannot be - the last half year is almost worse than all; for then he thinks the prison will take fire and he be burnt in the ruins, or that he is doomed to die within the walls, or that he will be detained on some false charge and sentenced for another term: or that something, no matter what, must happen to prevent his going at large. And this is natural and impossible to be reasoned against, because, after his long separation from human life, and his great suffering, any event will appear to him more probable in the contemplation, than the being restored to liberty and his fellow-creatures.

If his period of confinement has been very long, the prospect of release bewilders and confuses him. His broken heart may flutter for a moment, when he thinks of the world outside, and what it might have been to him in all those lonely years, but that is all. The cell-door has been closed too long on all its hopes and cares. Better to have hanged him in the beginning than bring him to this pass, and send him forth to mingle with his kind, who are his kind no more.

On the haggard face of every man among these prisoners, the same expression sat. I know not what to liken it to. It had something of that strained attention which we see upon the faces of the blind and deaf, mingled with a kind of horror, as though they had all been secretly terrified. In every little chamber that I entered, and at every grate through which I looked, I seemed to see the same appalling countenance. It lives in my memory, with the fascination of a remarkable picture. Parade before my eyes, a hundred men, with one among the newly released from this solitary suffering, and I would point him out.

The faces of the women, as I have said, it humanizes and refines. Whether this is because of their better nature, which is elicited in solitude, or because of their being gentler creatures, of greater patience and longer suffering, I do not know; but so it is. That the punishment is nevertheless, to my thinking, fully as cruel and as wrong in their case, as in that of the men, I need scarcely add.

My firm conviction is that, independent of the mental anguish it occasions - an anguish so acute and so tremendous, that all images of it must fall far short of the reality - it wears the mind into a morbid state, which renders it unfit for the rough contact and busy action of the world. It is my fixed opinion that those who have undergone this punishment MUST pass into society again morally unhealthy and diseased. There are many instances on record, of men who have chosen, or have been condemned, to lives of perfect solitude, but I scarcely remember one, even among sages of strong and vigorous intellect, where its effect has not become apparent, in some disordered train of thought, or some gloomy hallucination. What monstrous phantoms, bred of despondency and doubt, and born and reared in solitude, have stalked upon the earth, making creation ugly, and darkening the face of Heaven!

Suicides are rare among these prisoners: are almost, indeed, unknown. But no argument in favor of the system can reasonably be deduced from this circumstance, although it is very often urged. All men who have made diseases of the mind their study, know perfectly well that such extreme depression and despair as will change the whole character, and beat down all its powers of elasticity and self-resistance, may be at work within a man, and yet stop short of self-destruction. This is a common case.

That it makes the senses dull, and by degrees impairs the bodily faculties, I am quite sure. I remarked to those who were with me in this very establishment at Philadelphia, that the criminals who had been there long, were deaf. They, who were in the habit of seeing these men constantly, were perfectly amazed at the idea, which they regarded as groundless and fanciful. And yet the very first prisoner to whom they appealed - one of their own selection confirmed my impression (which was unknown to him) instantly, and said, with a genuine air it was impossible to doubt, that he couldn't think how it happened, but he WAS growing very dull of hearing.

That it is a singularly unequal punishment, and affects the worst man least, there is no doubt. In its superior efficiency as a means of reformation, compared with that other code of regulations which allows the prisoners to work in a company without communicating together, I have not the smallest faith. All the instances of reformation that were mentioned to me were of a kind that might have been - and I have no doubt whatever, in my own mind, would have been - equally well brought about by the Silent System. With regard to such men as the negro burglar and the English thief, even the most enthusiastic have scarcely any hope of their conversion.

It seems to me that the objection that nothing wholesome or good has ever had its growth in such unnatural solitude, and that even a dog or any of the more intelligent among beasts, would pine, and mope, and rust away, beneath its influence, would be in itself a sufficient argument against this system. But when we recollect, in addition, how very cruel and severe it is, and that a solitary life is always liable to peculiar and distinct objections of a most deplorable nature, which have arisen here, and call to mind, moreover, that the choice is not between this system and a bad or ill-considered one, but between it and another which has worked well, and is, in its whole design and practice, excellent; there is surely more than sufficient reason for abandoning a mode of punishment attended by so little hope or promise, and fraught, beyond dispute, with such a host of evils.

As a relief to its contemplation, I will close this chapter with a curious story arising out of the same theme, which was related to me, on the occasion of this visit, by some of the gentlemen concerned.

At one of the periodical meetings of the inspectors of this prison, a working man of Philadelphia presented himself before the Board, and earnestly requested to be placed in solitary confinement. On being asked what motive could possibly prompt him to make this strange demand, he answered that he had an irresistible propensity to get drunk; that he was constantly indulging it, to his great misery and ruin; that he had no power of resistance; that he wished to be put beyond the reach of temptation; and that he could think of no better way than this. It was pointed out to him, in reply, that the prison was for criminals who had been tried and sentenced by the law, and could not be made available for any such fanciful purposes; he was exhorted to abstain from intoxicating drinks, as he surely might if he would; and received other very good advice, with which he retired, exceedingly dissatisfied with the result of his application.

He came again, and again, and again, and was so very earnest and importunate, that at last they took counsel together, and said, 'He will certainly qualify himself for admission if we reject him any more. Let us shut him up. He will soon be glad to go away, and then we shall get rid of him.' So they made him sign a statement which would prevent his ever sustaining an action for false imprisonment, to the effect that his incarceration was voluntary, and of his own seeking; they requested him to take notice that the officer in attendance had orders to release him at any hour of the day or night, when he might knock upon his door for that purpose; but desired him to understand, that once going out, he would not be admitted any more. These conditions agreed upon, and he still remaining in the same mind, he was conducted to the prison, and shut up in one of the cells.

In this cell, the man, who had not the firmness to leave a glass of liquor standing untasted on a table before him - in this cell, in solitary confinement, and working every day at his trade of shoemaking, this man remained nearly two years. His health beginning to fail at the expiration of that time, the surgeon recommended that he should work occasionally in the garden; and as he liked the notion very much, he went about this new occupation with great cheerfulness.