3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

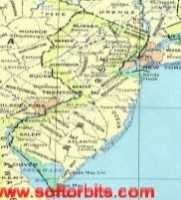

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Computers, Websites, and other Digital Gadgetry

What is novel today is old-hat tomorrow; but what is old-hat to someone today is still novel for someone else. These are our own thoughts about a variety of electronic novelties, for whoever finds them of interest.

West of Broad

A collection of articles about the area west of Broad Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

|

| West Broad Street Tour |

Larger Clubs

|

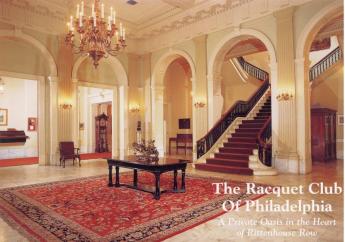

| The Racquet Club |

Philadelphia has dozens -- perhaps hundreds -- of clubs, societies, associations and organizations. Many owe their formation to the Sunday Blue Laws, which once made it illegal to obtain liquor on Sunday except on the premises of a private club. Some clubs were formed around the tradition that the stock exchanges (hence, the banks and brokerage houses) were open for business on Saturday mornings, leaving the financial community available for a long lunch, a drink afterward and a free afternoon in town. But primarily, Philadelphia already had a long tradition of fraternal and volunteer associations. Benjamin Franklin helped found a great many juntos, associations and volunteer groups for some civic purpose. Although he was not a Quaker, Franklin was in the Quaker tradition of forming voluntary committees and groups to get some particular job accomplished. In Quaker circles, aimless griping and complaining are not tolerated; if you have a "concern", you propose a solution which a committee can put into action, and you will probably be expected to be its chairman. The Quakers even had to devise a formula for "laying down" a committee when its purpose was completed, since, after a while, the original purpose of the club may disappear, but habit and good fellowship cause it to continue as a social club. A good example is a certain club which was originally founded for life-saving on the river, but now continues as an ice-skating club on the Main Line.

Anyway, clubs continue to be a center of Philadelphia life at the present time, often with founding traditions that are a little unclear to many of the members. It isn't as true as it was when the Sunday Blue laws were effective, or before the restaurant revolution overtook us, but to live in Philadelphia without being active in several clubs is to feel that nothing ever happens in this town, while your neighbors at the same time are so busy going to their clubs they never think to invite you. Or perhaps fear that since everyone goes to so many, you might feel pestered if they invited you to join.

|

| Union League of Philadelphia |

There does exist a different sort of club entirely, however. The big-city in-town social club was started as a place to stay when transportation to the suburbs was tiresome, and large clusters of people had townhouses near the business district. A place to stay when your wife is visiting her relatives. A place for the local bachelors to congregate. A place where the CEOs can congregate fraternally, avoiding the isolation at work that comes from being the boss. A place where lawyers can have a long lunch while they wait for the phone to ring with the big case they can retire on. A place to loaf, play pool, get a haircut, get your shoes shined, play a game of squash. Or get a drink and a decent meal in comfortable surroundings. Jeff McFadden, the director of the Union League, describes these clubs as "day camps for adults".

Such clubs have had a hard time in recent decades. The ten-story Manufacturers and Bankers Club is now an office building, the prestigious Rittenhouse Club is shuttered, along with the Commerce Club, the Locust Club, and a dozen others. The most prestigious of all, the Philadelphia Club is in a decrepit neighborhood next to Broad Street, which it hopes will soon revive and make wrenching decisions unnecessary for the club. The interior is as close to an English city club as you could find, with immensely valuable paintings and furniture, creaking stairs and quaint bathrooms. You're not likely to find more than five members at lunch these days, but the food is excellent, the service superb, and the posted waiting list for membership quite comfortably long. The posted names tend to be a list of the cream of society, but most of them live thirty miles away. It's no longer possible to stay there overnight.

|

| The Acorn Club |

The Acorn Club is for women, quite frequently women whose husbands are members of the Philadelphia Club. If ever there were some political move to force the two clubs to abandon the men-only and women-only rules, a merger of the two would allow them to continue exactly as before as a single club with two facilities. The Acorn Club is just up Locust Street from the Academy of Music, and that is surely no accident. The place is immaculate, elegant, quiet, extremely well managed.

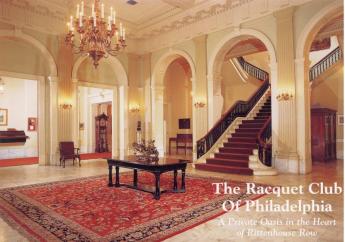

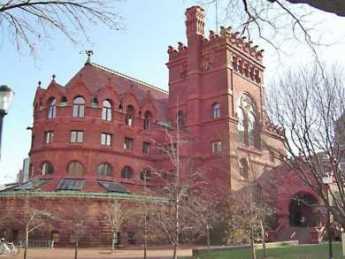

Around the corner on 16th Street is the architect Horace Trumbauer's turn-of-the-last-century Racquet Club. In some other city, it might be called the Athletic Club, which makes it more attractive to younger members than the other clubs, where billboards would be the extent of the exercise. Indoor swimming pools and gymnasia are extremely heavy and thus require expensive steel supports. This club not only has a pool, but it also has squash courts (both old-rule and new-rule), racquets courts (the thirty-foot walls are polished slate), and one of the five court tennis courts still in existence in the country. Court tennis is a strange game, of which it is said that "if you know the rules and own your own racquet, you are one of the top ten in the country". But the game originated in the Twelfth Century and was what people meant by "tennis" until 1878, when a game is known as "lawn tennis" was invented and took the world by storm. One of the other five court tennis courts is a few miles from the location of the hydrogen bomb factory on the Savannah River, eighty miles from Charleston. The DuPont Company put it there, and the location is no accident. > is having a hard time filling its space with members, but it would be so appallingly expensive to replace even a part of it, that superhuman efforts are justified to preserve it.

The Union League at Broad and Samson Streets, is the one outstanding exception to the decline of the center city men's club. When I joined it long ago, the strictest of rules prohibited women from any area except the women's dining room in the basement. I still remember the chairman of the admission committee, seated at the end of a long long table of gentlemen in the semi-darkness, intoning to me. "I'm going to ask you a question. And because I don't want any misunderstanding, I'm going to ask you twice. The question is, have you ever, even once, in any national, state or local election -- even once -- ever voted anything except straight Republican? Let me repeat, have you ever, even once. . . ?"

Well, the League lets in Democrats these days, and even quite a few women. But what has transformed the League from a declining relic into a thriving center of the Philadelphia social scene has been management. The League owns its own new parking garage across Samson Street from the side door, which is itself an innovation with a canopy. The dingy old members overnight rooms have been transformed into a four-star hotel, with concierge. The old steam rooms are now a modern exercise facility, and a dozen computers in the "business center" are always occupied. The menu has been upgraded, the service snappy instead of sleepy. The upstairs dining rooms usually have several hundred people for dinner when formerly they were deserted. Several times a year the League has an upscale dinner party for five hundred or so guests, that would be in a class with a reception for the King of England. Nobody any longer asks why they should be a member; they only ask whether they can afford it. Apparently, lots of people can, once they have a reason to.

|

| Cosmopolitan Club of Philadelphia |

Over in a nearby short narrow street (we hesitate to call it an alley) near the Racquet Club, is the Cosmopolitan Club, for women only, thank you. It's small, probably would have trouble accommodating more than a hundred at a time, but the food and service are great. The real reason for the existence of this club is the wish of professional and working women to have a place to gather and support each other's morale, listen to uplifting speeches, help along with the younger ones and that sort of thing. In some ways, the Cosmopolitan Club is the most typical of all Philadelphia clubs.

Northwest Rittenhouse Square

|

| {John Wanamaker's Mansion 2032 Walnut Street |

Market, Chestnut and Walnut Streets go right across the Schuylkill on bridges; that fact was once their glory, but now is the source of their problem. The first bridge to be built, at Market Street, was originally placed there in 1804. Placing your mansion on an important street makes you prominent, but if the street gets too busy, crowded and noisy you eventually wish you lived somewhere else. Air conditioning helps somewhat by allowing your windows to be closed all the time, but eventually, the increasing commercial value of the location gives you unwelcome neighbors. So right now the last few blocks of Chestnut and Walnut before you reach the river are pretty run down. Students from the Universities on the far side of the river make for street activity at night, but most of them head for the Eastern edge of Rittenhouse Square, where droves of them sit at sidewalk tables on a summer evening. Irreverent college kids refer to such a congregation as a meat market, but I'm only quoting them.

John Wanamaker had one of his many mansions just past the Square at 2032 Walnut, but it now is mostly an entrance to an apartment building towering above it. What now distinguishes this area most are the surviving churches.

|

| Unitarian Church |

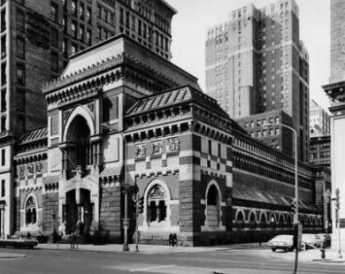

The Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut is one of Frank Furness' finest buildings and next to it is a renovated former Church of the New Jerusalem (Swedenborgian Church), now used for an advertising agency. Frank Furness won the Medal of Honor during the Civil War before he thought much about architecture. Swedenborg, for his part, founded what is known as a thinking man's religion, since Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) himself was a scientist of the first rank who might have won a Nobel Prize if there had been such a thing in his day. The Mother Church of this religion moved out to Bryn Athyn, abandoning the center city after what is reported to be a heated dispute. While the new cathedral is absolutely spectacular, the old one on Chestnut Street is still pretty fine, itself.

Across Chestnut Street is the Lutheran Church, which proves to be astonishingly large when you enter it, and it has great acoustical qualities related to the Moravian influences of the last century. Up at the NorthWest corner of Rittenhouse Square is Holy Trinity. Its minister, Phillips Brooks, wrote the words of the Christmas carol "O Little Town of Bethlehem", which are a poem of considerable merit and sophistication. Unfortunately, the need to adjust these words to music which children might single to the attachment of three different tunes of less than classic musical proportions, sometimes even less sonorous when sung simultaneously by adults who remember different tunes from their childhood. In view of the far from the peaceful scene of present-day Bethlehem, at least the message of the carol warrants recollection indeed. And, yes, the church is reddish brown in color, as most Episcopalian churches seem to be.

There once was a time when Anthony Drexel walked down Walnut Street to work every day. One can easily imagine him tipping his hat to passers-by, striding along in front of formerly elegant mansions which line the street but are now too big to maintain. This area was a place of show houses, of downtown places to hold parties during the social season, from thence fleeing to a second house in the suburbs, or in Maine, or in Europe, during the summer. The Great Depression of the 1930s forced most of these people to choose between their various residences, and because of the advent of the automobile, they mostly chose the other places, abandoning these. It was the end of the Gilded age.

For a tour of Rittenhouse Square, mentioned in this Reflection, visit Seven Tours Through Historic Philadelphia

Mrs. Meade's House

|

|

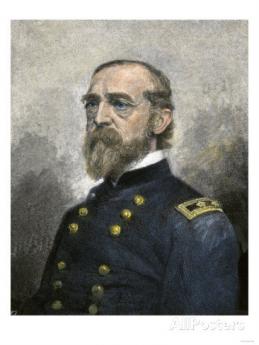

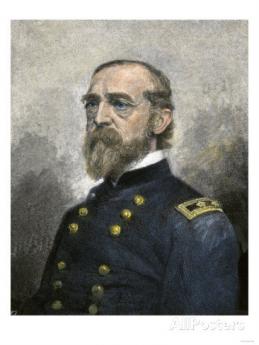

Union General George Gordon Meade |

General George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg, lived in quite an elegant house during the six years (1866-72) he was a Commissioner of Fairmount Park. The house (at 19th and Delancey) has "MEADE" carved over the stately entrance facing 19th Street, and while the neighborhood has run down somewhat, it was obviously once an imposing mansion. The house belonged to Mrs. Meade. From that, you might suppose that the General had married a rich woman, but that would be wrong.

When General Lee was advancing on Gettysburg, it was widely supposed that his goal was to conquer Philadelphia, the Arsenal of the North. The town was in a panic, built some forts on the Schuylkill to defend itself, and later lionized the hometown hero who had saved them. Mrs. Meade was living at the time in a modest little place, and the town fathers took up a collection to buy General Meade a proper house.

A delegation of officials traveled down to Virginia to present him with their gift of gratitude, but Meade would have none of it. He was only doing his duty, and could not consider for a moment accepting major gifts for his soldiering. No, he was very sorry, he had to decline.

So the delegation came home, all a fluster. Someone then had the idea of offering the house to Mrs. Meade. And when they visited her, she promptly said "Sure."

The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing

|

| Statue of Diana |

The brownstone house at 1710 Spruce Street is seemingly not remarkable, it's just an Edwardian house now converted to lawyers' offices on the first floor. But it's nevertheless a landmark, curiously linked to that 13-foot statue of Diana which dominates the top of the main interior staircase of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Many Philadelphia gossips believe the model for the statue was Evelyn Nesbit, who lived in the brownstone on Spruce Street. But she was born in 1884, whereas Augustus Saint-Gaudens created the statue for the 1892 Columbian Exhibition. Since Evelyn was only eight years old at that time, however, it must have been some other woman who took off her clothes to pose for the sculpture; for us, it doesn't matter who she was. The statue was moved to the top of Madison Square Garden when that structure was really still located on New York's Madison Square, but when the Garden was demolished in 1925 the Diana statue came to Philadelphia. Madison Square Garden itself has moved twice in the meantime and is mostly associated in the public mind with prize fights and political conventions. However, when the first Garden was built, it had theaters and roof-top restaurants, and its spectacular nature instantly made the architect, Stanford White, the most famous architect in New York, eventually maybe the most famous one in the world at the time.

|

| Thaw |

Meanwhile, two residents of Pittsburgh independently came to New York where the action is, the iron and coal millionaire Harry K. Thaw, and an impoverished teenager named Evelyn Nesbit. Evelyn was accompanied by her mother who, recognizing the girl's extraordinary beauty, set about to steer her to fame and fortune. At the age of thirteen she was posing for artists, and in time became the favorite model for Charles Dana Gibson. Gibson created the "Gibson Girl", an idealized role model for millions of women who dressed the way she did, wore their hair the way she did, and behaved in the proper Edwardian style they imagined she did, too. It was in Gibson's studio that she encountered Stanford White. Evelyn had another life, however, as a "Florodora Girl", and one of her many stage-door Johnnies was Harry K. Thaw, the millionaire. That was no saint, having a reputation for using a dog whip on his numerous lady friends, but it is uncertain whether he was completely aware that

|

| Evelyn Nesbit |

Evelyn was one of the principle entertainers in half a dozen hide-aways that Stanford White is said to have established for naughty parties to amuse New York's fast set. That was certainly aware that Stanford White had been Evelyn's boyfriend before Thaw married her, and the two men cordially hated each other. One evening, some provocation made Thaw walk over to White's table in the rooftop restaurant of Madison Square Garden, and shoot him dead -- in front of hundreds of people. It's a curious sidelight that Stanford White was carrying a train reservation to Philadelphia, to discuss plans for the domed structure of the Girard Bank building. The notoriety of the murder trial was the sensation of the decade, with the prosecutor remarking that White deserved what he got, and Thaw's mother offering Evelyn a million dollars if she would give testimony supporting a plea of insanity. Everyone seems agreed that the money was never paid, although the jury was sure as impressed as the newspaper reporters with Evelyn's refusal on the witness stand to testify against her husband, quite evidently a sign of loyalty. Anyway, the jury let him off, and a famous cartoon depicted Stanford White in the pose of the statue of Diana.

|

| Joan Collins as Evelyn Nesbit "The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing" |

Evelyn sort of dropped out of sight after the trial and the subsequent divorce, until TV interviews were conducted for the movie about the episode, \"The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing". By 1957, Evelyn was decidedly less of a beauty. Meanwhile, Harry K. Thaw had continued to live in the brownstone house in Philadelphia, where once he got sick and called a friend of mine to be his doctor, and eventually another famous professor to be a consultant. When the butler answered the door, the consultant told the butler to tell his employer that he must insist on cash in advance, an action that thoroughly embarrassed my friend in view of the famous wealth of the client. But the consultant had rightly assessed the situation since later Thaw's lawyer called up and told the family doctor he was sorry but his client was not going to pay his bill since the medicine was started by some botanical book to be a poison in excess quantity. In consternation, my friend called up the professor and asked what to do. "Chalk it up to experience," was the answer. "But what have I learned?" The consultant paused, and said, "Maybe you have learned to extend credit only to decent people."

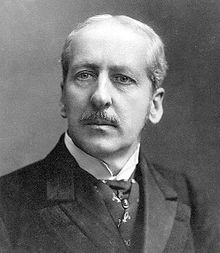

Widener, Stotesbury, and Trumbauer

Gerry McFadden devoted most of his short life to researching the history of Philadelphia clubs, but illness kept him from publishing much of it. Walton van Winkle has apparently taken up the role of club historian for the city, and much that survives to be known comes to us from them. For which we all ought to be grateful.

|

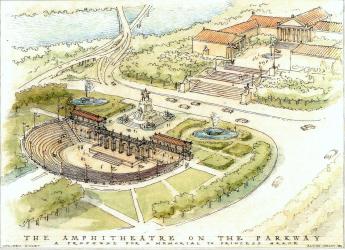

| Racquet Club |

The Racquet Club was once located at 9th and Walnut, just three blocks from the debtors prison at 6th and Walnut where the game of squash racquets is said to have originated. In 1906 it was decided to build a new club at 16th and Chancellor Streets; that did come to pass, largely because of three members. Henry Widener had taken a small inherited fortune and blown it up into a large personal fortune by monopolizing the trolley business in town. Edward T. Stotesbury, a much younger man, had ascended to the Presidency of Drexel and Company, in affiliation with J. P. Morgan. Both of these tycoons had built awesome mansions in the suburbs, one called Whitemarsh for where it was located, and the other called Lynnewood, on the grounds of what is now a huge apartment complex at the north end of Broad Street.Horace Trumbauer was the architect for both of these palaces, bringing together two men of considerably different age and personality. The conviction grew that Philadelphia needed a really first-class athletic club, and in 1906 it got built. Architect Trumbauer saw the whole design as related to the terrifying weight of the swimming pool full of water, and the indoor tennis courts, faced with thick slabs of slate. Builders who understand these things are impressed with the concept of a central tower to carry the internal weight of the building. The whole internal guts of the place are supported by steel girders of the type used to build bridges, ultimately resting on holes in the bedrock drilled 26 feet deep. If someone comes our way with an atom bomb, this is a good place to be a member.

The Racquet Club has one of the four or five Court Tennis areas in America, an interesting thing to look at, although the rules of the actual game are as baffling as those of cricket.

Another notable sight is the men's dressing room, wood-paneled and luxurious enough to be the scene of several movies. The shower heads, in particular, dump hot water on you like a Turkish Bath.

The Racquet club was always primarily for young men and tended to be a little raucous. It used to be said that almost anybody could be admitted -- you can take that for what it is probably worth -- but then the young members were carefully observed for their behavior, particularly in whom they married. If they seemed to be the right sort, they could then be invited into the Rittenhouse or the Philadelphia Club.

Market at Schuylkill

|

| Kelly Drive River Side |

Two columns of commercial high-rise office buildings are now advancing West on Market Street, although construction has halted for the moment because of economic recession. The last four or five blocks before you reach the Schuylkill are in a state of decay characteristic of real estate waiting for a developer.

|

| river view 30th street |

Because the land rises to a summit around 22nd Street and then slopes off to the river, Market Street at this point becomes the approach to a bridge, and the buildings have their front doors considerably above the ground. One apartment building and a furniture design building (there's a very good restaurant inside) take advantage of the view over the river, which can be quite spectacular at night. Outdoor lighting at sundown suddenly emphasizes the impressive classical architecture of 30th Street Station, and the Art Museum on its acropolis.

|

| Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

But down at the bottom of the buildings, well below street level on the bridge approaches, is a pretty intimidating scene right out of some novel by Charles Dickens, with cobblestones, dark alleys, deserted parking lots, and dim street lights. This is the area of the former terminal of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad . In its time, the Terminal building was an admired product of the imagination of Frank Furness(pronounce:"furnace"). It will be remembered that the Pennsylvania RR tracks run along the West bank, converting this lovely river into a depressing sight for several miles. The B&O was the first railroad in America, and for a while, the two railroads were booming competitors. Both railroads have of course gone through bankruptcies and mergers, their names are gone. It's even hard to say for sure who owns what is left of them.

|

| Reading railroad |

Just about every railroad in America (the European ones are government subsidized) has been through bankruptcy, so the whole railway industry had a century of the boom but now has an uncertain future. The B & O at first only headed westward to Ohio, but then turned North to try for New York-Washington dominance by coming up the Schuylkill on its East side, going through a tunnel under the Acropolis that now holds the Art Museum, and then turned East along Race Street to join the Reading Railroad at 12th Street. The Reading had a North-South spur called the Trenton Cut-Off which was to be the trunk line for the combined East Coast railroad. Eventually, the Pennsylvania Railroad won this battle by avoiding acquisitions and using leased rights of way. Although it eventually became the dominant railroad of the country, Pennsylvania only owned the property between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, leasing all the rest from about 70 partner lines; it proved a better business model than purchasing the trackage.

|

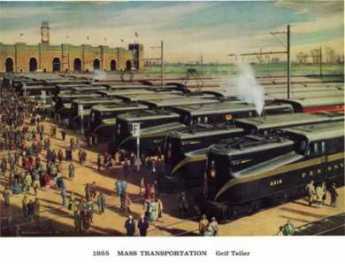

| Industrial Revolution |

This transportation frenzy had to reflect a major underlying economic upheaval. Two events propelled Philadelphia into the Lehigh and Delaware Rivers, and then the railroads brought it down along the Schuylkill, because the Lehigh River alternative was steep and rocky, filled with dangerous rapids.

The second economic event was the discovery of oil in upstate Pennsylvania. Almost all freight traffic on the great national railroads was going from East to West, so the trains returned East without much cargo. But the discovery of oil was soon followed by the construction of refineries in Philadelphia, creating the return traffic needed to put the Pennsylvania Railroad ahead of its competitors, especially the New York Central. Heavy rail traffic and smoking refineries create a wasteland around them, and that was the price Philadelphia paid for its boom.

For a tour of the area mentioned in this Reflection, visit Seven Tours Through Historic Philadelphia

The Swedenborgian Church

|

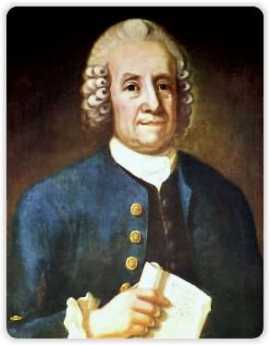

| Emanuel Swedenborg |

Among the many churches centered in Philadelphia, the Swedenborgian is probably the least typical and most difficult to understand. The church does not actively seek out a new membership, but it welcomes everyone, in the spirit of Emanuel Swedenborg's observation that "All people who live good lives, no matter what their religion, have a place in Heaven." Without attempting to define the teachings of Swedenborg (1699-1772), who was quite able to speak for himself, it can be approximated that Heaven plays a central role in this belief system, and predestination does not. Although the ceremonial features of this religion are very similar to the Episcopal Church, its main emphasis is on good works as a way of attaining the reward of Heaven. In some ways, that is an unexpected position for a noted scientist like Swedenborg to take, since generally scientists lean toward Calvinism, with the mechanistic view that if God is all-powerful, then human free will must be impossible.

|

| cross |

There are at least four divisions of the Swedenborgian religion, but the Bryn Athyn branch is most notable in the Philadelphia region. A very wealthy adherent of Swedenborg named John Pitcairn bought a large tract at Bryn Athyn and gathered the local church to live around a perfectly magnificent cathedral and church school. It is hard to think of any church in the Philadelphia region which approaches the magnificence of the Bryn Athyn cathedral. It has a special character that it was conceived and built during the crafts movement of the early twentieth century, with imported European workmen deliberately organized like medieval craft guilds. The central features of this workmanship reflect and then project the belief in personal individuality within the whole religion. No two windows, or doorknobs, or carvings are the same in the cathedral, reflecting the wish for each workman to devise his own unique creation and show the way of personal responsibility to the faithful. This cathedral is one of the things in the Philadelphia region most worth visiting, but to appreciate its quality you have to know what you are looking at.

Everybody in this church is unexpectedly hard to characterize. The Pitcairn Foundation was such a successful investor that it formed a mutual fund for others to share in its good fortune. Its central philosophy is to invest only in corporations which have been dominated by a single family, preferably the founding family, for at least fifteen years. There are about six hundred eligible corporations, and recent management scandals in the newspapers illustrate the Pitcairn's exactly knew the dangers of handing your assets over to a hired manager. This family-centered investing approach consistently yields better than the S & P 500, which in turn beats ninety percent of investment managers. You sort of get the idea you know where this family is coming from when you meet a courtly, meek, retiring but friendly person, who can say, "My mother is the only person I ever met who looked perfectly at home seated under a sixty-foot ceiling."

|

| Helen Keller |

Two other famous Swedenborgians illustrate the unusual individualism of this religion. Helen Keller, the deaf-blind girl who overcame her handicap by going to Radcliffe and becoming a successful author and lecturer, for one. The other would be Johnny Appleseed (1774-1845), whose real name was John Chapman. Grammar school legends would have this bearded, barefoot vegetarian adopting a life of poverty like St. Francis, but in fact, he was an extremely shrewd businessman who died rich. He developed the business plan that American settlers would be going West into what was then the Northwest Territory, and having a tough time getting enough to eat the first year or two. So, he anticipated the paths of frontier settlement, and went ahead among the Indian tribes, planting apple trees. When the settlers arrived in the region, he sold them young apple trees and showed them what to do with them. Apples grown from seed are not the tasty morsels we know today but tend to be rather shriveled and bitter. So Johnny showed them how you make cider, and if you let it sit around a while, hard cider. The settlers would use the pulpy squeezing for compost, and he would be back to collect the seeds from them so he could continue his business plan in the next county. In short, he showed them how to drink the apples. He also let the Indians pick the apples, so they liked him and spared him the common troubles of the frontier.

If you are going to boil apples, you need a pot, and Johnny often carried his like a hat. He wasn't a nut, at all, he was a showman. In his backpack, he was also carrying a Bible. And in his head, he carried a motto, "All religion has to do with life, and the life of religion is to do good."

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

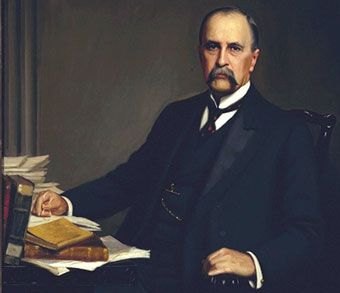

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Bullseye Sociology

Philadelphia is turning inside out. It used to be a commercial, financial and business center, surrounded by beautiful suburbs. It is now turning into a marvelous urban residential area, surrounded by a ring of commerce based on the ring of interstate highways. Commuters leaving the city in the morning outnumber the commuters coming in, and traffic jams are worse in the outer ring.

|

| Phila Skyline |

More precisely, the metropolitan area is a series of concentric rings. The bull's eye is Center City, with urban residences, culture, entertainment. Immediately surrounding the bullseye is a ring of decaying industrial slum. Surrounding that are the suburbs, and beyond them are the new malls and industrial parks. Further out is exurbia, where Philadelphia's "equestrian class" is mixed with what is left of the farmlands, rapidly being invaded by McMansions intended for employees of the commercial ring. Some people live their whole lives in just one ring.

Somewhere near Washington's old encampment at Valley Forge there is an invisible line. The people who live inside that line, live in Philadelphia. But just one house further out, on the other side of the invisible line, the orientation is toward central Pennsylvania. The people outside the ring mean "Pottstown" when they say they are going to town; if they say they are going to The City they mean "Reading". Going to Philadelphia is for them like going to Paris; they did it once.

There are other invisible lines. At the edge of the central city bullseye, there is gentrification; yuppie families are renovating the 19th Century mansions their grandparents abandoned for the suburbs, displacing working-class families who lived for a generation or two in decaying grandeur. The local bars are inhabited by one class, the neighboring restaurants are where the newcomers hang out. Beer in one, wine in the other, and sour looks when members of the wrong class blunder in. In London, you see the same thing, except it is usually a single building with two entrances.

There is another border region out further, where upwardly mobile minority groups are pushing out toward the suburbs. Curiously, working-class Philadelphia always tended to live in "neighborhoods", and their out-migration has more commonly leap-frogged to "Jersey", their places being increasingly taken by Asian immigrants.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (1)

|

| B. Franklin Parkway |

Philadelphia has straight streets and square blocks in all directions, by the hundreds. Just a few streets slant off at an oblique angle, and most of those, like Germantown Avenue, is following old Indian Trails. The one, cold-blooded, deliberate slant street is the Benjamin Franklin Parkway which essentially runs from City Hall to the acropolis holding the Art Museum aloft. Just whose idea it was is unclear, although the architect Horace Trumbauer gets most credit. The actual design was given to a Frenchman, Jacques Greber, presumably because it imitates the effect of the Champs d' Elysee in Paris -- a broad sweeping boulevard with lanes of trees along the side and in the medians. As things turned out, a simple idea was pretty hard to put into practice. First of all, plenty of people in Philadelphia don't like anything if it's French, and an even larger number don't like the idea of messing around with our nice traditional system of squares at taxpayer expense. The people who lived in the area were naturally upset to see the ends of blocks chopped off, destroying the corner property entirely and exposing the backyards of the neighbors to public view. At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the Pennsylvania Railroad's Chinese Wall cut off the center of town from "North of Market" , and the Parkway thus created a triangle of desolation that could only recover when the Swan Fountain appeared, named

|

| Swan fountain |

after the President of the Philadelphia Fountain Society. The sculpturing was done by Alexander Stirling Calder, the son of the sculptor (Alexander Milne Calder) of William Penn atop City Hall. The original design made the mistake of planting all the trees as red oaks, and so most of them died of the same disease at the same time, requiring replacement with mixed varieties of trees that would not be so susceptible to epidemics. People were reluctant to live in the isolated triangle of land to the South of the Parkway, and also in the strip of land North of the Parkway up the steep hill to Eastern State Penitentiary on Fairmount Avenue. Accordingly, the land was filled with public buildings, including the semi-prison for adolescents, the Central Detective Bureau, and so on. The deep cut for the railroad spur connecting the Baltimore and Ohio (along the Schuylkill) with the Reading Railroad running out of 12th and Market, didn't help encourage people to raise their children in the area, either. And that wasn't all. The Swan Fountain was designed in such a way that you couldn't get underneath it to change a light bulb, so a set of tunnels had to be dug underneath the fountain plaza as an afterthought. Planting the plaza with Paulownia trees was a stroke of genius. Although the blue blossoms are only spectacular for one week out of fifty-two, the massive limbs are always striking, even in the dead of winter.The Rodin Museum

came along, and although it is a little isolated, is a grand display in the same spirit as the boulevard itself, including the modernist sculpture of Alexander Calder. There is talk of creating a museum on the Parkway for the three generations of Calder's, and even agitation to bring the Barnes Museum in from Merion. With the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Franklin Institute and the Art Museum itself, the boulevard is still growing and evolving.

When traffic is heavy, people just want to get home as fast as possible, but most of the time the Parkway uplifts the soul, just as it was intended to. It's an outdoor thing, not an interior one, and there is something symbolic about the famous movie run of Rocky, pounding up the stairs to turn, holding up his victorious arms, to a breathtaking view of the city. But remember, although now closely associated with the Art Museum, he never went inside.

John Bartram's Garden

|

| Bartram Gardens |

It's worth a visit to Bartram's Gardens, if only for the astonishment of finding a very large farm and stone Quaker farmhouse within a few blocks of our largest medical center, a stone's throw from the biggest oil refinery on the upper East Coast. And located on the edge of a neighborhood that is, well, past its prime. The trees on the farm are centuries old, so walking around the grounds imparts the feeling of being hundreds of miles from civilization when in fact you are only a hundred yards away from streets that are very urban, indeed. When you turn in certain directions, an occasional skyscraper peeps over treetops, and down the meadows, at the farm's dock on the leafy-banked Schuylkill, you can see oil storage tanks across the river, just a long shot with a 2-iron away. Look upward, to see the upper half of shining towers of Center City.

The farm property as it now stands dates back to 1728, but the site marks the earliest beginnings of the city, nearly a hundred years earlier. The river curves around this hill then snake on down to Delaware through flatlands which were originally swamps ("wetlands", as they say). The hill is as far downriver into malaria territory as the Indians were willing to go, so the Dutch traders had to sail upriver and dock there in order to take thirty or forty thousand fur pelts back to Holland each year. One thing or another has been dumped on the swamps for three hundred years, and the oil companies found it a cheap place to buy enough land for their refineries, close to four or five railroads near Bartram's place, and with access to the high seas. Right now, most of the oil comes from Nigeria, emptying two or so supertankers a week. There has to be enough storage capacity to take care of delays caused by bad weather on the Atlantic, and there has to be access to railroads and highways to carry the finished product away. The rest of a refinery is just thousands of miles of metal pipes, gleaming in the sun.

Sun Oil is trying to be a good neighbor, turning more and more of the area over to nature preserve, as chemical engineers have learned how to work in a smaller space with fewer employees. The banks of the lower Schuylkill are now mostly grown to shrubs and trees, concealing from boat travelers the rather extensive dumps of old auto tires and similar refuse. It's a placid winding trip, increasingly coming to resemble what the Dutch traders once encountered. Especially in May, when the Palomino or Empress trees are in purple bloom. It seems the Chinese packed their porcelains in dried Palomino seed pods, and the discards have grown up to quite a nice display. Logan Square is filled with such trees, quite artfully pruned and maintained; just imagine several miles of the river lined with them, and you can see why the Tourist Bureau is excited about the potential. If you have been to San Antonio you know the potential of an urban river ride, which in this case might go all the way up to the Art Museum. Given enough public response, you can envision two or three-day barge rides from New Castle, Delaware to Pennsbury, with side trips up past Bartram's to the Waterworks. Right now, trips are comparatively limited by the tides, with a few trips a year down from Bartram's to the refineries, and a few more up to the river to the Art Museum. They use floating docks, and permanent docks will need to be built.

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

Originally, the crude oil came from upstate Pennsylvania, near Bradford, and was the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Baltimore and New York were also the beginnings of transcontinental railroads, but their freight cars came back empty. The upstate Pennsylvania oil gave the PRR a dominant edge by supplying cargo for two-way revenue.

When George Washington had to retreat from the Battle of Brandywine, the armies had to cross the wetlands, and the river, to get to Philadelphia. Washington got there first and burned the boats after his army got across. He knew, but the British probably did not fully realize, that the first place to ford the Schuylkill was at Norristown. When the British finally got that far, Washington was waiting for them, but a fall hurricane came along and soaked everybody's gunpowder before there could be much of a battle. Unfortunately, Mad Anthony Wayne was unprepared for a nighttime bayonet charge, and there was still quite a slaughter.

You can't wander around John Bartram's house and gardens without getting the impression of considerable wealth. Bartram was interested in botany, becoming the most eminent authority on plants of the Western hemisphere, a very close friend of Benjamin Franklin, and probably the main force behind the creation of the American Philosophical Society. But although Bartram was a hobbyist, he was a shrewd businessman, selling curiosity plants to Europeans, and commercially improved fruits and vegetables to local farmers. There are still some Bartrams around Philadelphia, with a strong Quaker air about them. Around 1850 the place was sold to a zillionaire railroad magnate named Eastwick, who fixed up the place in the high style he learned building the railroads of Russia for the Tsar. The mansion has been torn down, but the stone farmhouse, stone barn, stone sheds, stone outbuildings, stone everything -- endures, like many of the curiosity trees and bushes. Well worth a visit.

Psychiatry: Last Cow in Philadelphia

The present problem with PSYCHIATRY can be summarized as follows: At the suggestion of the American Hospital Association, Congress introduced the DRG system of paying for inpatients by diagnosis, rather than itemized services. It worked well except for psychiatry, where the diagnosis usually implies little relation to the later costs it generates, so an exception was made. The dual system of payment created loopholes which unfortunately overpaid psychiatric hospitals and were described as exploitation. Congress over-reacted in a way that was unsustainable, and essentially all of the psychiatric hospitals of the nation were forced to close. This is not a history for anyone to be proud of, and the lack of outcry is also a disappointment. However, after twenty years without reform, evidently, nothing is going to be done without an outcry.CONVENE BLUE RIBBON COMMISSION TO REPAIR PSYCHIATRIC INPATIENT CARE. The 1983 BRA switched hospital inpatient reimbursement to payment by diagnosis (DRG). Abuse of the psychiatric exclusion then led to "corrective" legislation which has essentially reduced American's psychiatric inpatient care to an underfunded national disappointment. The problem is not an easy one, so a commission should devise a workable methodology for psychiatric hospitals, relying neither on present approaches nor on DRG. But overpayment is a better outcome than no care at all. Homeless people sleeping in cardboard boxes on downtown steam grates are the consequence any visitor to the area can observe at night after the commuters go home. Psychiatric social workers readily recognize their daytime patients in the boxes.

* * * * *

|

| Daniel Blain, M.D. |

Daniel Blain, M.D. (1898-1981) was just about the most important psychiatrist in America. He was the Physician in Chief of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital at 49th and Market, the first and in many ways the most prestigious psychiatric hospital before it was closed. Before that, he was the first Medical Director of the American Psychiatric Association, itself the first (1844) medical society in America. His fame rested on organizing the disorganized psychiatry of the Veteran's Administration into a chain of advanced "Dean's Hospitals", a huge and very important achievement. Before that, he had achieved considerable fame as the man who took the dilapidated State Psychiatric Hospitals with a reputation as "snake pits" and made them a respectable part of the medical community. And before that, he had been born in China as the son of missionaries. As a matter of fact, even before that, he was a descendant of General Mercer of Revolutionary War fame.

Dan was an outstanding example of the peculiar fact that Psychiatry was dominated by social upper crust psychiatrists in Philadelphia for a very long time. In fact, Benjamin Rush of the 8th Street branch of the Pennsylvania Hospital is known in some circles as the "Father of Psychiatry", while in other circles he is known for signing the Declaration of Independence. That isn't true in other cities, and it definitely isn't true in New York City, where the psychoanalytic school of Sigmund Freud took that city by storm, and essentially drove every other school of psychiatric thought out of town, out of medical schools, out of psychiatric hospitals. The famous sixteen-year psychoanalysis of Woody Allen is an example of the extremes of that fad. Every profession has petty civil wars of that sort, best left undiscussed in public. But in the case of psychiatry, it was indirectly a material contributor to the present disappearance of inpatient psychiatry, and the related appearance of lots of homeless people on steam grates. Let me give a biased view of what is a massive human tragedy, which someone else can "rectify" if he chooses.

|

| APA |

It starts with a Budget Reconciliation Act of the 1980s, which brought us the DRG (Diagnosis-related) system of paying for hospitalized patients. The idea was that appendicitis resulted in essentially 7 days in the hospital, give or take a couple of days, and the bills for admission for appendectomy were for more or less the same amount. If you had fifty or a hundred cases a year in your hospital, the high bills balanced the low bills, and the overall hospital reimbursement was essentially the same without itemizing the bandages and whatnot. Congress bought this package, and after it got going, just about all hospital bills were reimbursed at one of three hundred prices, the cost to the government was the same, and there was a whole lot less bookkeeping and accounting cost. It was a success, except for a few cases where the costs did not closely line up with the diagnosis, and psychiatric hospitals were where they concentrated. So, psychiatric hospitals were excluded, and psychiatric bills skyrocketed. This experience has been carelessly cited as an example of the evils of payment by service ("fee for service"), when in fact the duration of psychiatric hospitalization is related to features of the condition, like danger of suicide, rather than the diagnosis itself. Psychiatric leadership at the time contained many in a subset of physicians who did not think much of inpatient psychiatry in the first place and even less of lobbying, and they underestimated the severity of the assault on the specialty. Apparently, no workable formula for pricing inpatient psychiatry has since been brought forward to be approved by a Congress which is more accustomed to getting its lobbying in the form of one-liners. And would you believe it, psychiatric inpatient care soon disappeared.

|

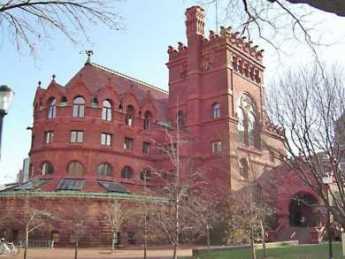

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

That's right, if someone in your family needs psychiatric hospitalization, I wouldn't know where to tell them to get it -- at any price. From considerably overpaying for psychiatry inpatients to paying scarcely anything for them, this little change of the regulations caused every psychiatric hospital I know of by name, to close. It helped balance some state budgets, but it also was a considerable factor in filling the steam grates of American cities with people who sleep on cardboard boxes. And what it illustrates is that this is what political society always seemed to do, before Dan Blain and a small group of upper-crust psychiatrists were temporarily able to shame them into something better. In fact, if there is any tattered remnant of good inpatient psychiatric care left in America today, it is in the Veterans Hospitals that Dan was able to straighten out.

Dan Blain will probably eventually be bypassed as a curiosity, like his wife. She was a Wister Logan Blain, descended from families who ruled Philadelphia a hundred years before even General Mercer came along. So the Blain couple lived on an enormous farm plot, centered at 20th and Olney right next to LaSalle University, which is built on their property. It also contains the Peale House, where Charles Willson Peale lived as the elected president of the rebel faction of the American Revolution. Peale didn't know what he was supposed to do, so he resigned and painted portraits of people. The Blains enjoyed keeping a cow on their land, the last cow in Philadelphia, and the LaSalle students enjoyed stealing the cow and leaving it on the top floor of a dormitory, for laughs. Meanwhile, the Blain couple had cocktail parties on their front porch for visiting dignitaries. They usually wore blue jeans, and Mrs. Blain, the absolute Queen of Philadelphia society, was occasionally observed to pour vodka into her glass of beer. That sort of background may well have been useful when psychiatry needed to be built up and humanized, but it became a liability when the rest of inpatient psychiatry failed to appreciate what was knocking on its door.

Beaux Revival

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux's mother died two weeks after she was born. Cecilia rejected many offers of marriage, was never brushed by scandal, devoted her life almost entirely to the pursuit of excellence as a portraitist of women and children. It does not take much of an amateur psychoanalyst to surmise she was dominated by fear of pregnancy, and possibly guilt about being the cause of her mother's death. But living in the Victorian era before Lister and Pasteur could finally make childbirth safe, her sort of life was not as unusual as it is today, except for her notable thirst for achievement. An aristocratic upbringing almost certainly contained a strong condemnation of boasting and self-promotion, with the result that she is sometimes referred to as a perfect model for the graduates of Bryn Mawr College, although she did not attend there. Placing its emphasis on success for women other than or in addition to marriage, the quiet determined graduates of that college make a goal of achievement, not fame. Beaux became the finest woman portraitist in America, possibly the finest portraitist anywhere, but it was a title she earned and deserved without theatrics or egotism. Lots of eligible men found this attractive, but she retreated for her own reasons in her own graceful way.

Monica Zimmerman lectures on this and other topics at the Academy of Fine Arts and recently talked at the Right Angle Club. We are grateful to her for pointing out the influence of John Singer Sargent in opening up for Beaux the borders of grand manner portraiture, enhancing the mood and intimacy by surrounding the subject with an environment, rather than the dark gloomy plain backgrounds that are so traditional. Parenthetically, there is a marvelous example of this school of portraiture hanging in the hall of presidential portraits at the Union League. Among the collection of gloomy dark backgrounds for the other presidents, the portrait of George Herbert Walker Bush shows him on the portico of the White House and allows his luminous likeableness to shine out among the severe and stately presidential peers. Photographic portraiture has to struggle to blot out distracting background; portrait photographers like Bachrach struggle to imitate what is more natural for backgrounds in painted portraits. Except for those of the school of Cecelia Beaux.

|

|

Beaux's two-year-old niece and favorite model, Ernesta Drinker (1892-1981) |

One other feature to be noticed about the Beaux exhibit is her outstanding ability to work with white. There are white gowns, white frilly dresses, white upholstery in a profusion seen rarely because it is so difficult to do.

Go see the next exhibit of her work at the Pennsylvania Academy. It's an event that will be talked about for a long time.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1374.htm

Geckos: Academy of Natural Sciences brings Mini Dinosaurs

|

| Gecko |

FRIENDS who spent time in Vietnam have a lasting memory of lizards stuck to the ceiling, catching flies with their tongues. Those animals are named geckos, one of the oldest and probably most varied families of reptiles, but confined to the Southern hemisphere. Fossils have been found containing geckos from fifty million years ago, so they were here before the big dinosaurs were wiped out, when the Yucatan was probably struck by an asteroid.

|

| Anthony Geneva |

There was a time when Africa, India, South America and Antarctica were united in one monstrously big continent, and the many varieties of gecko are scattered over the land masses which originally made that up. At least this is the way Anthony Geneva explains it to visitors to the Academy of Natural Sciences at 19th and Ben Franklin Parkway. There are no geckos to be found naturally in Philadelphia. Philadelphians hardly need reminding that the first dinosaur bones, ever, were discovered in Haddonfield NJ, and were soon taken to the Academy for permanent display. Ever since that time, the Academy's collection of dinosaurs has expanded, and are the things with the most impact on school-age visitors. The Academy is getting ready to celebrate its 200th anniversary in a few years, however, and contains much more than dinosaur bones, including extensive research facilities with world-famous scientists at work in them. In any event, the dinosaur image is a clear metaphor for the present display of little reptiles that look like dinosaurs, whatever the DNA trail may be. The main exhibition area is currently filled with dozens of glass display cases containing live geckos, and the little rascals are so good at camouflage that you have to hunt carefully for them before they suddenly seem to emerge from the shadows. There are white ones, black ones, bright green and bright orange ones, speckled in all sorts of weird patterns. They make sounds resembling bird songs, and the term gecko is a native word referring to such sounds. The Academy displays these gecko-noises for visitors who are invited to push twenty or so buttons. Geckos move, but suddenly, and probably for some predatory purpose. If you are really into geckos, you focus on their feet.

|

| Gecko |

The variety of toe and foot shape is almost infinite and seems more so if you have a magnifying lens. The foot pads terminate in different kinds of extremely fine hairs, and that's their big secret. Those hairs are so fine the molecules of the foot and the molecules of the wall or ceiling attract each other magnetically. Since no energy is expended in the adherence, the gecko can remain attached to a wall or ceiling indefinitely, even after the gecko dies. But, by raising the angle of contact to thirty degrees, the foot detaches, and the little rascals can scoot along very rapidly, upside down. At present, there is a great deal of commercial and maybe military interest in clarifying the secrets of this adhesion. To be industrially useful, the footpad size would have to scale up to much larger dimensions, but just imagine gluing together the vessel ruptures and aneurysms inside the brain as we now do in a cumbersome manner with chicken-wire stents, just one example that quickly occurs to a visitor. If these little fellows figured out how to make these reversible adhesives fifty million years ago, our scientists ought to be able to imitate them.

Drop around to visit the Academy. It's filled with amazing things like this.

Rara Avis

|

| The Academy of Natural Sciences |

School children grow up in Philadelphia with an image of the Academy of Natural Sciences as a place to visit dinosaurs. Indeed, it does have on display the first dinosaur skeleton ever to be discovered, as well as a number of others. However, only about a third of the building complex on Logan Circle is devoted to public museum displays. The rest is devoted to specimen storage, library and scientific work of the highest scientific eminence and value. In the scientific area, the most striking thing to a visitor is to notice how few windows there are. Scientists often spend their time looking through microscopes, so they don't care about windows. In a skyscraper business office that wouldn't be acceptable at all and the staff would all get the heeby-jeebies and quit. In the business world, the number of windows your office has is important, especially if they are corner offices, the best kind.

|

| Humming Birds |

In one small area of the museum is a set of ingenious metal cabinetry containing 200,000 bird specimens, including every one of the 10,000 known species of birds on earth. In fact, about a quarter of all the "type" specimens are found there with red tags on their feet. A type specimen is the first known and described specimen of that particular bird, ever. That's a round-about way of relating that this is where Ornithology, the study of birds, began. It also tells you that when bird skins are treated with arsenic salts, they last a very long time; a considerable number of the specimens in the cabinets were contributed by Audubon, himself. New bird skins are acquired at the rate of a thousand a year, related to the scientific studies which go on, studying bird diseases, genetic changes due to environmental changes, and pollution effects. The recent uproar about Avian influenza revolves around the tendency for bird diseases to undergo genetic changes themselves and become human diseases. A great many such bird diseases are maintained at the laboratory in case they are needed for a crash program of vaccine development. Environmentalists will be surprised to learn that the mercury content of bird feathers has actually declined in the past century.

|

| Guinea fowl |

With a good guide you quickly grasp the attraction of this topic of birds and birding. There are huge condors, with six-foot wingspreads; and one-inch hummingbirds. Birds of every shape and coloring, reaching some sort of extreme with the Bird of Paradise from New Guinea. Owls and eagles, ducks and chickadees. Hummingbirds defy the usual sort of nets; every single little hummingbird specimen was obtained by shooting it with a special little gun. If you see a hummingbird in your garden, just imagine what skill it takes to shoot one.

The ornithology department maintains an active program of loaning bird specimens to scientists all over the world, although this activity has recently been affected by computerization of the catalog of specimens, resulting in a massive global internet conversation among ornithologists, sort of like a Facebook of a very special sort. For all this activity going on, the collection area is an eerily silent place.

And that's just birds, crammed into an organized space of, well, maybe fifty by two hundred feet, eight feet tall, fifty shelves per typical cabinet. Right next to it is the insect collection, perhaps taking twice the cabinet space. Insects are a lot smaller than birds, so each shelf has more specimens. That sounds like an awful lot of Latin names to try to remember. And a certain amount of danger, too. Several scientists died of arsenic poisoning before the full hazard was appreciated and contained.

The University City

|

| University of Pennsylvania |

In 1920, the University of Pennsylvania graduated 34 students with B.A. degrees, and 134 with M.D. degrees. Today, the campus is a little self-contained city of 50,000 inhabitants. The transformation of the campus during that period is an outward expression of revolutionary expansion of the student body, involving demolitions, restorations, new construction. And the nearly constant shortage of parking space.

|

| David Hollenberg |

David Hollenberg, the University Architect, recently gave the Franklin Inn Club an interesting description of the University from the point of view of bricks and mortar. Since almost every building on the campus is undergoing or plans to undergo a major building project, he had a lot of material to cover. The disappearance of the railroad-based industrial area of West Philadelphia has been an economic problem for the city, but of course, this abundance of vacant land has created a major opportunity for the University of Pennsylvania. One reflection of this abundance is the opportunity to become the developer for much of the whole region around the campus, working with private developers who wish to be in the University area, and are therefore willing to coordinate their plans with those of the University. It's a remarkable opportunity. Since it comes at the time of a major economic downturn, one can only hope that the University does not impoverish itself taking advantage of this good luck.

|

| Jonathan E. Rhoads |

As the graduation statistics illustrate, not so long ago the University was largely a medical school, with appendages. There are rumors of considerable friction from time to time, between the President of the University and the Dean of the Medical School as to who was boss; it is easy to imagine the trustees swinging from one side to the other. The most notable Provost of the University in modern times was Jonathan Rhoads, who also happened to be Professor of Surgery. If you know Quakers, you know that disputes were seldom rancorous. And if you know Jonathan, you know he almost always won the disputes.

|

| Cira Center |

While today, the dominant change is caused by the Cira Center buildings and the acquisition of the former Post Office building, it is well to keep in mind that the new Cancer Center is a billion-dollar project. A great deal of the medical school expansion is centered on burgeoning research, particularly in molecular biology, largely financed by the National Institutes of Health. While the leaders of the NIH have long struggled with Congress to keep politics out of both the administration and the substance of research, it seems to old-timers that the politicians are slowly winning. Senator Specter's seniority on the Appropriations Committee may have had as much to do with the prosperity of West Philadelphia, as the quality of research, however eminent. We are about to find out, and if things go hard with us in favor of say Chicago, it could be a wrenching experience. Most of those research buildings cost more to heat, air-condition, insure and clean than the entire tuition base of the students; and they wouldn't be good for much if you tried to sell them.

The University is almost unique in being located on contiguous land, near existing public transportation, and occupying substantial old structures capable of renovation to new purposes. Mr. Hollenberg was asked whether it was cheaper to grow like this within a city, or whether it is cheaper to plant a totally new university in several open corn fields, as we often see happen. While this is a hard question to answer, and depends to some extent on the type of architect in charge, it is his view that big-city restoration is a considerably cheaper way to expand than building from scratch on open land, although if you are starting the institution itself from scratch, there isn't much choice but the cornfield.

And then, there is the ancient argument between academics and bricks and mortar. Development officers agree that it is easier to raise donations when you can name a building for the donor; grand visions for new frontiers of teaching are a much harder sell. So a question does hang over this expansion, however exciting, whether the endowment will keep up with the structures, once the excitement of physical expansion dies down. These are definitely things to worry about, but right now you seize the opportunities as they go past, leaving integration to your successors to figure out.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Manna

|

| MANNA |

On 23rd Street, right next to the home of the First City Troops, is another organization of quite a different character. This is MANNA, which stands for Metropolitan AIDS/HIV Neighborhood Nutrition Alliance. This group was founded in 1990 by members of the Presbyterian Church at 21st and Walnut but has become independent and non-sectarian. It has an annual budget of over $3 million, a hundred paid employees, and a thousand volunteers. They deliver meals to people who have been referred to them by physicians as suffering from AIDS, and agreed by the social workers on the staff, to be poor. Last year, they delivered 650,000 free meals and spent a lot of effort fund-raising to do so. About half of the funds come from the government, quite a bit from private foundations and individuals, and a lot from six annual fund-raising events. One of the six events is to sell pies at holidays, one is a Ballet Performance. There's a black-tie dinner, and so on. So the organization is a curious mixture of Show Biz and earnest volunteerism of the old Philadelphia spirit and style.

One might suppose from all this that Philadelphia is riddled with AIDS, and of course we do have a discouragingly large number of afflicted victims. However, there are a million people in the USA with HIV, and only 20,000 are found in Pennsylvania By contrast, New Jersey has 50,000 victims. And all of that is almost trivial compared with 40 million known victims worldwide with probably a lot more who are unrecognized as sick. The World Health Organization has found cities in Africa, Mombasa for instance, where 90% of the babies born in the hospital test positive. It is reasonable to suppose that Africa will be totally depopulated in a decade if matters continue unchanged.

So, in the meantime, until someone figures out something better to do, Philadelphia is responding to its problem in a traditional and typical way. The writer Susan Sontag has been saying that nothing short of a religious crusade for monogamy will save the undeveloped world, and maybe she's right. At least, people are thinking about the problem and trying to do something, however inadequate, to help.

Old Blockley (P.G.H.)

|

| Old Blockley |

For a long time, the Philadelphia General Hospital was the largest hospital in town, even growing briefly to seven thousand patients during the Civil War, but leveling off at about three thousand at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. At the end of World War II, it had shrunk to about 1500 beds, but it was Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 which finally did it in. By 1977 it was costing the City of Philadelphia about five million dollars a year beyond its revenues to run the place with only 300 patients, while the running expenses of the local private hospitals were actually less, per patient. Titles XVIII(Medicare) and XVIV(Medicaid) of the Social Security act constituted Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, and in effect they made every patient at PGH resemble a walking government check in the mind of hospital administrators. The local hospital association made the argument to the Mayor Rizzo that everybody would be better off if the hospital closed and those government checks were directed to the local voluntary institutions. After a few years, the federal government inevitably squeezed the generosity out of the bargain they would of course now like to abandon. But that's the way it goes. PGH is gone and it isn't coming back. The eighteen acres in Blockley Township, now West Philadelphia, were given to the University of Pennsylvania next door, and gigantic amounts of federal money were contributed to the building of skyscrapers replacements for the original PGH. Ironically, the two hundred children's beds now on the location are fewer in numbers than the three hundred adults once considered too uneconomically few to maintain, and the cost per day of hospitalization is roughly ten times the PGH cost which had been described as unsupportable. The rest of the real estate is built up with buildings involved in medical research, which is also an activity dedicated to working for its own extinction. Discovering a cheap cure for cancer would quickly create a need to fill the vacancies with something else. No one regrets this system of creative destruction, but everyone should regret the diminution of the spirit of local philanthropy which underlay it.

PGH was one of a dozen or so big-city charity hospitals, like Bellevue in New York, Charity in New Orleans, or Cook County Hospital in Chicago. Of these hospitals, PGH had surely been the best, and at the turn of the Twentieth Century a Mayor's commission issued a report about the place which began, "Philadelphia can surely be proud...." Having worked in Bellevue and having visited most of the rest, I can testify that was likely true. When PGH was finally torn down, the walls and floors had such substantial construction that changing the wiring and plumbing to some other purpose had become almost impossible. The PGH nurses were famous for running. Although the alcoholic and drug-addicted patients might be called the dregs of society, the alacrity of the student nurses in running them bedpans or answering other calls, was spectacular to watch. When a doctor came on the floor, they jumped to their feet and were usually ready with the patient's charts, unmasked. Unlike Bellevue, where the floors were creaky and wooden, the open wards at PGH were spacious, clean, well maintained and equipped. At Bellevue, the forty-bed wards were crowded with sixty or seventy patients, so close together you could almost roll from one end of the room to the other without touching the floor. I can remember seeing one seventeen-year-old Bellevue student nurse tending such award at night alone, the intern sharpening needles, and the medical resident developing electrocardiograms in the darkroom. None of this would have seemed acceptable at PGH.

|

| Dr. William Osler |

Old Blockley was the place where modern systems of medical education originated. Up until William Osler came to Philadelphia, medical education mostly consisted of attending eight hours of lectures a day. Osler had an electrifying personality and wandered among the sick at PGH with a train of students following him. He is much quoted, and once suggested his obituary ought to read, "Here lies the man who took the students into the wards." A somewhat more elegant statement of the value of the practical experience was included in his dedication speech at the Boston Library: "To treat patients without books is to sail an uncharted sea. To read books without seeing patients is never to go to sea at all. Osler was somewhat underappreciated during his time in Philadelphia and went on to found the medical school at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Nevertheless, the main reason he later left John Hopkins and went to Oxford was his dismay at the adoption of the "full-time" system, which is to say the faculty stopped having a private practice of their own to act as a gold standard for their research and teaching. When all is said and done, there are some areas of discomfort in the transition of students from observers to actors. The PGH system of learning surgery was commonly reduced to a slogan, "See one, do one, teach one,"; things have progressed to the point where it is probably right for the public to insist on greater supervision and control than the old almshouse provided.

The disappearance of old Blockley ended a controversy, or even something of a mystery, about which was the oldest hospital in America, PGH or the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce. There had been an infirmary in Old almshouse at Eleventh Street, and there is no doubt the almshouse was there first. PGH grew out of the almshouse. However, there were many comments at the time of the founding of the Pennsylvania Hospital that it was now the first; that's a strange thing to say when the almshouse was three blocks away. Social historians need to look into the mindset of colonial America, which seems to have included the distinction between the worthy poor and the unworthy poor. Somehow, the founding principal of the Pennsylvania Hospital was to get people back to work who were capable of productive work, possibly even paying for itself in that way. In their minds, apparently just giving solace and help to those who were down and out was not quite the same thing.

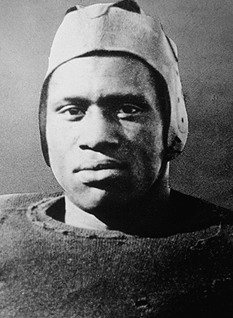

Paul Robeson 1898-1976

|

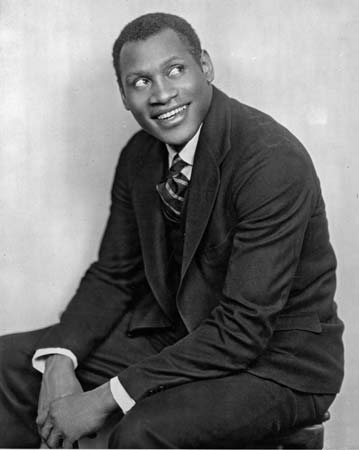

| Paul Robeson 1898-1976 |

Everyone with international fame and fortune seems to belong to another planet, but Paul Robeson belongs to the Philadelphia region as much as to any locality. He was born in Princeton, of a black minister who went to Lincoln University, and a mother of Quaker heritage. Not only an All-American football player, but he also won twelve varsity letters. He not only was accepted to Columbia Law School, but the only black person in the class became its Valedictorian. Later on, his amazing baritone voice made him the perfect person to sing "Old Man River" in the musical Showboat, and quite a different dimension emerged in his highly memorable portrayal of

|

| Paul Robeson as Othello |

Shakespeare's Othello. He was combative athlete, nobody's fool, and had a commanding stage presence. It was scarcely surprising that he resented the social slights he encountered in his upward mobility, or in a time when many people -- not just in show business -- were leaning leftward, that he frightened people with his praise of Communist Russia and seeming incitement of his race to rebellion.