3 Volumes

Tourist Walk in Olde Philadelphia

You've seen the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall.

Come now on a tour of the city the Founding Brothers lived in, a smaller city than today which they knew intimately. Their Colonial Philadelphia can be seen in a day's walk through the center of town.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Sixth and Walnut

over to Broad and Sansom

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions.

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area still remains dominated by medical institutions.

As you emerge from the Curtis Building, it's worth a half-block detour to 7th and Samson to glance at Jeweler's Row, a curious concentration of diamond merchants who have clustered there since before the Civil War. However for this leg of the tour, turn about to Washington Square, now a quiet manicured residential square but once the site of the Walnut Street prison, the location of the first balloon ascension, the potters field of colonial days, and the home of the unknown soldier of the Revolutionary War. There are accounts of people catching abundant fish in a brook once running through the square, well into the Nineteenth Century. Because of the brook, there were tanneries in the region; tanneries always smell bad. Accordingly, the deed from the Penn family for the Pennsylvania Hospital nearby is revocable if anyone ever decides to build another tannery on its grounds.

On Sixth Street, a few feet south of Walnut, is the splendid brownstone Italianate structure of the Athenaeum, established just after the Revolution as a private lending library, and continuing so today. It's well worth a brief visit to grasp why Lafayette joined it, and so many other members have contributed Nineteenth Century, mostly French, sculpture and paintings. Next door is the former home of then-Mayor Richardson Dilworth. It looks vaguely Georgian in style, but was actually built forty years ago as Dilworth's personal statement that Society Hill needed to be revived as a fine place to live. Although Charles Peterson is credited with the idea of starting Society Hill by restoring Stephen Girard's house at Third and Spruce, Peterson bought it for $1800 and eventually sold it for millions. By contrast, Dilworth spent millions for his house, and it later sold for much less. Although they served the same cause, the two men of entirely different social class were rather reserved with each other.

Cross the grassy Washington Square, turning left on Seventh Street. Until 1980, this area was the home of publishing, mainly medical publishing, but now publishing's loft buildings have been converted to condominium apartments. The penthouses on the top of these buildings are invisible from the street, but are truly spectacular.

Spruce Street itself is a sort of architectural museum, with houses on the Delaware dating to 1700, getting progressively more recent as you go West. At the level of Seventh Street, the houses date from around 1810, eventually reaching Broad Street around 1890. Midway up the block of Spruce Street from 7th to 8th on the North Side (the South Side is nothing but facade, covering hospital buildings) is the house --really two houses run together -- of Nicholas Biddle. He had more backyard than most houses in the suburbs now do, even once keeping a baby elephant there. The house was made famous for dinner parties conspiring against Andrew Jackson, and later its social glamour was described admiringly by that gossip diarist of the time, Sydney George Fisher.

At Eighth and Spruce, one half of a city block is occupied by the most modern of hospitals, now tending 440 patients after the manner of a medical Swiss watch. The remaining half of the block is a museum of American Medical History, polished and manicured by professional museumologists. There are, however, many people still alive who remember when it containing 160 desperately sick poor people, tended to by unpaid nursing students and resident physicians. It is frequently said that the history of American Medicine is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital .

At Ninth and Spruce, Joseph Bonaparte the Emperor's brother once lived, subsisting on a steamer trunk of gold coins he brought along. Continuing north to Locust Street, Thomas Jefferson University begins, and stretches for several blocks in all directions. Before turning west, however, glance down to the southwest corner of 8th and Locust, the original Musical Fund Hall. The music moved west to Broad Street, but the Musical Fund Building was long the largest auditorium in town, housing entertainments and graduations. Abe Lincoln was nominated for his second term, there. Turning about to view Jefferson, it is easy to believe it is now the largest employer in Center City, and furthermore owns most of the major hospitals in the Pennsylvania suburbs.

Now proceed west on Walnut (although if hungry you might instead wish to take a short detour to the Reading Terminal Farmers' Market), going past the little alley between 12th and 13th Streets called Camac Street, a street of little clubs the most notable of which is the Franklin Inn. Note that Camac Street is paved with wooden blocks, to deaden the clip-clop of horses' hooves. At the corner of 13th and Walnut is the Philadelphia Club, the oldest and toniest men's club in town with a membership limited to 300. As you reach Broad Street, you can see the brownstone gingerbread of the Union League, now by far the largest and most successful club in town.

Further north on Broad Street looms City Hall, designed to be the tallest building in the world but superceded by the Eiffel Tower made of tinker toys while the Philadelphians struggled to build with solid stone. Short of the Maginot Line, it is hard to imagine any building more solid than this one. No expense was spared, and it is really worth a tour. That little statue of William Penn on top is 37 feet tall. Just across the street to the north of it is the Masonic Temple, an equally spectacular series of architectural flourishes. If you visit (the public is quite welcome), you will never forget seeing this place. The Masonic Temple is not an imitation of City Hall; it was built there first.

So that's the end of our one-day historic walking tour of historic central Philadelphia. No doubt you are tired and want to go home. We've left you right by Suburban Station (17th and Arch) if you are going to the suburbs. If you are going to New Jersey, take the high speed line at Broad and Locust (there's an entrance down stairs on the two eastern corners).

Working Girls Get the Faints

|

| Curtis Building |

Curtis Publishing Company once covered a full city block of Philadelphia, from Sixth to Seventh Streets, Walnut to Chestnut. The northern half of this complex was the Public Ledger Building, once housing a failed diversification move into newspaper publishing and later rented out as commercial office space after the newspaper died. On the top floor of the Ledger Building was the Down Town Club, quite a palatial meeting place for the whole publishing industry which stretched for blocks around. Both Curtis-owned buildings have the same architectural design and together make a massive looming presence next to Independence Hall on one street and Washington Square on the other. To build from Walnut to Chestnut means shutting off Sansom Street in the middle, and that permits the jewelry trade to nestle in a cul de sac on the West side of the publishing complex.

So Curtis was once a little city within a city, and most of the rest of the town only saw its facade and the crowds of people coming and going through the entrances. To a neighborhood doctor on an emergency call, however, it was almost exclusively inhabited by young women. Kitty Foyles, you might say. I certainly formed that impression after having a medical office two blocks away, getting occasional calls.

|

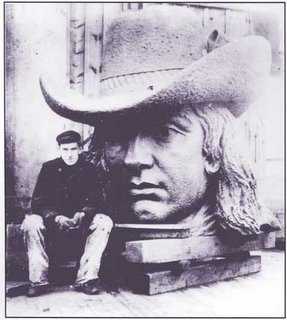

| Christopher Morely |

So far as I can remember, Curtis had only one medical problem, repeated over and over. An anguished call would come that someone at Curtis was unconscious, come immediately, take the elevator to the third or fourth or fifth floor. At the elevator, the doctor would be met by a somewhat older woman, obviously the den mother of the working girls. Into the ladies room, we would go, where a young woman was usually sitting on a couch looking sheepish, although occasionally she was still passed out. The key finding was a very slow pulse. She had fainted, she was better, and now what. It was Curtis policy to send the fainters home after the faint, and I never could see any particular objection to that.

For me, there were never any men to be seen, at Curtis. Surely there must have been dozens of writers and editors and advertising people, but somehow they would vanish when one of these fainting things happened. Curtis was nothing but women when I was there, mostly watching me like a beach full of seagulls, watching a fisherman.

Mayors and Limos

A number of prominent figures participated in the downtown revival of Philadelphia after the Second World War, with a surprising amount of jealousy among them. Mayor Richardson Dilworth would have to be mentioned in any list of those leaders, but one who was more admired than loved. Aristocratic and flamboyant, he disdained the little hypocritical dissembling so characteristic of politicians. In fact, he didn't see himself as a politician at all, he was a leader. Once Dilworth became convinced that Society Hill revival was not only desirable but feasible, he moved there. He purchased two houses next to the Athenaeum on Sixth Street, and in spite of the protest of preservationists that those two houses were particularly fine examples of Federalist style on Washington Square, he had them torn down. Furthermore, in spite of outcries that the house he was building in their place was merely a pseudo-colonial gesture, he constructed a very expensive but extremely comfortable modern house. Those of us who were familiar with the neighborhood were impressed with the courage he displayed in doing this, because the area was just a little dangerous, and almost no one else lived there. You could buy dozens of twenty-room houses in the neighborhood for less than $2000 apiece, and it seemed foolhardy to make such a large personal investment in what might become a stranded gesture. This was described as flaunting his personal wealth because it was not just a fine house, it was possibly going to be a big loss. Dillworth got away with it. He was seen as courageous, and a leader. Others started moving into the area, mostly rehabilitating old mansions. By the time the house was eventually sold by his estate, his conspicuous consumption turned out to be a profitable investment. Smart. Dilworth had some practical problems. It wouldn't have been smart politics to have a long black limousine pick him up in the poor neighborhood. The only people who do that are undertakers and the Mafia. On the other hand, the driver of a limousine often doubles as a bodyguard, and a bodyguard wouldn't be a bad idea. Those of us who drove down 6th Street every morning at 8:30 gradually noticed what Dilworth did to solve the problem.

Every morning a Yellow Cab could be seen parked outside his door. It always had the same uniformed driver, and on closer inspection, the cab was the cleanest shiny late-model car, painted yellow. It was only six or seven steps from the door of the house to the door of the car, and he was off and gone in a moment. Other mayors have had quite different styles.Frank Rizzo had his long black car and several like it parked on the sidewalk outside City Hall. His image was that of a poor boy from the neighborhoods who had made it to the top. No matter where he went, Rizzo was leading a parade.

Ed Rendell, on the other hand, was playing the role of America's Mayor. His driver would blow the horn, put on the headlights during the day, roar through town, making screeching u-turns right and left. Several times a day he would put on this act, going two blocks from City Hall Annex to the Convention Center, to address an audience of visitors. Well, mayors and bank presidents are supposed to have limousine service. Anyone else would have to ask whether it was worth all the trouble if instead, you could just catch a cab. Those long cars are surprisingly uncomfortable to ride because the roof is so low you have to crawl on hands and knees to get in a seat. Finding a place to park one of those monsters, or even a wide enough opening next to the curb to let out the back-seat occupant, can be a problem in the center of a city. Even with portable cellular phones, there is a delay after you call for the car when you are ready to leave your appointment. Those who have tried it find that hiring a driver almost always confronts you with a demand to circumvent taxes by paying the driver in unrecorded cash. In South America, where bodyguards are really necessary, the great majority of them flee in terror at the first sign of the underworld. Limos are a pain. At least in Philadelphia, you can get a fairly clean, fairly new cab with a fairly knowledgeable driver, by simply holding up your hand at any center city street corner. During business hours at least, you can hail a cab in three minutes. That doesn't just happen that way, and the mayor has something to do with it. Cities usually have a Medallion system of cab licensing, and existing cab companies don't want any medallions issued to competitors. In politics, such a situation helps campaign funds considerably. The result is a shortage of cabs, surly drivers, and high prices. Boston is such a town. On the other hand, if medallions are easy to obtain, as they are in Washington DC, the cabs become numerous enough but are shabby dilapidated old vehicles, driven by recent immigrants who don't know the street names. In Philadelphia, we take our good fortune for granted, but we do owe a debt to the city government for managing the supply and demand situation to the point where it mostly would be foolish to have your own car and driver. In this town, every man a king. As a matter of fact, in Boston it got so bad that Ned Johnson, the richest man in town (he personally owns the Fidelity Mutual Fund Investment Family) got so enraged that he couldn't ever get a cab that he founded his own cab company. It's a very elegant one, although a little expensive. The Boston Coach Company supplies immaculate and impeccable service for a fee. At first, it was only available to Fidelity executives but now has spread out to anyone willing to pay for it, and flourishes in many cities, plus chartered airplanes if you don't like to wait in security lines at airports. You have to admire Johnson for his golden business touch, but in Philadelphia, we can just use cabs. Washington Square

Although he spent a lot of time in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, Henry James wrote about Washington Square in New York. It was Christopher Morley who wrote about Washington Square in Philadelphia. The best short essay about Philadelphia's Square is found in this link. The subject of Washington Square includes an interesting variety of topics, including the Walnut Street Prison, famous balloon rides, the Athenaeum, Penn Mutual Life Insurance, Curtis Publishing Company, N. W. Ayer, Harry Batten, Lea and Febiger, Lippincott Publishing, Saunders, Orange Street, the St. James Apartment House, Richardson Dilworth, the Farm Journal the old PSFS building, and the Maxfield Parrish mosaic. REFERENCES

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

There is a painting of the region around 8th and Spruce Streets in the 1750s, depicting a pasture, with cows, and three or four buildings between 8th and 13th Streets. When the Pennsylvania Hospital moved there in 1755 from its temporary location in a house located a block from Independence Hall, there were complaints that it was now located so far out in the woods that it was difficult and dangerous to go there. Still another description of the area is evoked by the provision which the Penn family placed in the deed of gift of the land, strictly forbidding the use of the land as a tannery. Tanneries have always been notorious for giving off noxious odors, so most people wanted them to be somewhere else, anywhere else. In any event, the main activity of Penn's "green country town" at that time was concentrated closer to the Delaware River, and the nation's first hospital was definitely placed in the outskirts. Two blocks further West the almshouse was already in place, but not much else. We are told that Benjamin Franklin had flown his Famous Kite at 9th and Chestnut, using a barn there to store his materials. It might be recalled that the population of Philadelphia, although the second largest English-speaking city in the world, was only about twenty-five thousand inhabitants at the time of the Revolution, and in 1751 was even smaller. In any event, the first and oldest hospital in America was built on 8th Street between Spruce and Pine, and the Eighteenth Century buildings on Pine Street still present a breathtaking view at any season, but particularly in May when the azaleas are in bloom, and fragrance from the flowering magnolias fills the evening atmosphere for blocks around. Although some people today mistake the Pennsylvania Hospital for a state hospital, it was founded in the reign of George II, decades before there was such a thing as the State of Pennsylvania. The Cornerstone was laid by Benjamin Franklin, with full Masonic rites. Most doctors regard a hospital as a mere workshop, but the affection with which many Pennsylvania physicians regarded their special hospital is indicated by the number who have requested that their ashes be buried in the garden. For two hundred years, beginning with the first American resident physician Jacob Ehrenzeller, the interns and residents were paid no salary, so they had to live on the grounds. An Internet was just that, interned within the four walls for at least two years. Because the resident physicians had no money, they stayed in the hospital at night and on weekends, playing cards and swapping stories. The hospital was home for them, as it was for the student nurses, likewise unpaid but more strictly confined and supervised. This penury seemed acceptable because the patients were mostly charity ward patients, otherwise unable to pay for their own care. Ehrenzeller finished his medical apprenticeship and went to practice for many decades in the farm country of Chester County, but gradually upper-class Philadelphia moved from 4th Street westward to and beyond the hospital, and two of the richest men in American history, Morris and Biddle, had houses within a block of the hospital, although Morris never lived in his house, having more pressing matters in debtor's prison. Therefore, later resident physicians at the hospital had the potential of setting up a private practice in the area and becoming society doctors as well as academically prominent ones. Being a charity hospital in a rich neighborhood created the potential for volunteer work by the town aristocrats and large bequests for charity. The British housed their wounded in the hospital during the Revolutionary War and shot deserters against the red brick wall of the small cemetery to the north. A century later, there were a couple of dozen rooms for private patients in the hospital for the convenience of the doctors and the neighbors, but everyone else was a charity patient. And a century after that, the hospital still did not have an accounting department to collect bills and tended to regard people who asked for a bill as a nuisance. Benjamin Franklin is regarded as the Founder of the hospital, and his autobiography famously describes how he fast-talked the legislature into matching the donations of the public, not mentioning to them that he had already collected enough promises to see the project through. This seems in character; Franklin's biographer Edmond Morgan summed up that, "Franklin doesn't tell us everything, but what he does tell us, is straight." The idea for the hospital was that of Dr. Thomas Bond, whose house is now a bed and breakfast on Second Street, but it was characteristic of Franklin to be the secretary of the first board of managers of the hospital. In Quaker tradition, the clerk of a meeting is the person who really runs the show. It thus comes about that the minutes of the founding board were recorded in Franklin's own handwriting, among them the purpose of the institution, which is to care for the Sick Poor, and if there is room, for Those Who can pay. This tradition and this method of operation continued until the advent in 1965 of Medicare when charity care was displaced by concepts which the nation had decided were better. The Pennsylvania Hospital was not only the first hospital but for many decades it was the only hospital in America. Its traditions, sometimes quaint and sometimes glorious, cast a long shadow on American medicine. REFERENCES

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed. I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting. "Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left. Musical Fund Hall

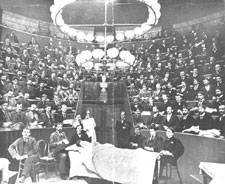

At the corner of 808 Locust stands a condominium building with a colorful history. It was originally the First Presbyterian Church, and then in 1820 the famous architect William Strickland converted it into the largest musical auditorium in the City. For several years, a group of music lovers had been meeting to discuss the problem of aging and retired musicians, most of them impoverished. The idea arose of giving several benefit performances each year to raise money for retired musicians, and the idea was enlarged to create a Musical Fund Society to put on regular concert series. Since it was by far the largest public auditorium, it also served for graduations, speeches, conventions.

It thus came about that in 1856 the Republican Party held its first national convention there, nominating for President John C. Fremont, the famous explorer of the West. The Republicans had two main components, the advocates of the abolition of slavery, and the residual of the Whig Party, which had come apart. The Whigs were mainly concerned with using government effort to promote the economy, building canals and roads, and similar ideas for public benefit. Abraham Lincoln had been a fervent Whig.

As a musical society, the Musical Fund was quite instrumental in persuading this Quaker City that music could be used for purposes other than religious incantations and frivolous entertainments. And it was useful in bringing the new instruments and musical concepts from Europe to the New World. Louis Madeira has written an interesting history of the early musical significance of the Musical Fund. When the Academy of Music opened in 1856, the old hall on Locust Street became a relic of the past. It had assets, however, and the organization continues to function as a granting agency for musical production and development in the Philadelphia area, even though it is itself no longer in the business of musical production. And then the third strain of history in this old place is the development of Musical Unions. This is natural enough, in view of the original purpose of helping indigent musicians. But unfortunately, several competing unions appeared, most of them on Locust Street and the dissention was bitter and continuing. In 1871 Philadelphia was the scene of the creation of the National Musical Association, and although the local 77 became a part of the national movement, it was stormy. Competitive musical unions had a history of calling the police to shut down speakeasies run as private clubs by their competitors. During the Depression of the 1930's there were many accusations of Communist infiltration, and counter accusations that Joseph Petrillo, the national president, was a Nazi. An underlying theme among musicians was that foreign immigrants were willing to work for less than the standard wage, and hence many of the coercive features of the union were aimed at forcing immigrant musicians to become members and to refuse to work for substandard pay. Some idea of the bitterness in the situation can be gained from the strike against the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1956. Ten years later, only one member of the union in ten was employed. REFERENCES

Eakins and Doctors

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture. Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition. S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work. In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing. That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies. The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer. Larger Clubs

Philadelphia has dozens -- perhaps hundreds -- of clubs, societies, associations and organizations. Many owe their formation to the Sunday Blue Laws, which once made it illegal to obtain liquor on Sunday except on the premises of a private club. Some clubs were formed around the tradition that the stock exchanges (hence, the banks and brokerage houses) were open for business on Saturday mornings, leaving the financial community available for a long lunch, a drink afterward and a free afternoon in town. But primarily, Philadelphia already had a long tradition of fraternal and volunteer associations. Benjamin Franklin helped found a great many juntos, associations and volunteer groups for some civic purpose. Although he was not a Quaker, Franklin was in the Quaker tradition of forming voluntary committees and groups to get some particular job accomplished. In Quaker circles, aimless griping and complaining are not tolerated; if you have a "concern", you propose a solution which a committee can put into action, and you will probably be expected to be its chairman. The Quakers even had to devise a formula for "laying down" a committee when its purpose was completed, since, after a while, the original purpose of the club may disappear, but habit and good fellowship cause it to continue as a social club. A good example is a certain club which was originally founded for life-saving on the river, but now continues as an ice-skating club on the Main Line. Anyway, clubs continue to be a center of Philadelphia life at the present time, often with founding traditions that are a little unclear to many of the members. It isn't as true as it was when the Sunday Blue laws were effective, or before the restaurant revolution overtook us, but to live in Philadelphia without being active in several clubs is to feel that nothing ever happens in this town, while your neighbors at the same time are so busy going to their clubs they never think to invite you. Or perhaps fear that since everyone goes to so many, you might feel pestered if they invited you to join.

There does exist a different sort of club entirely, however. The big-city in-town social club was started as a place to stay when transportation to the suburbs was tiresome, and large clusters of people had townhouses near the business district. A place to stay when your wife is visiting her relatives. A place for the local bachelors to congregate. A place where the CEOs can congregate fraternally, avoiding the isolation at work that comes from being the boss. A place where lawyers can have a long lunch while they wait for the phone to ring with the big case they can retire on. A place to loaf, play pool, get a haircut, get your shoes shined, play a game of squash. Or get a drink and a decent meal in comfortable surroundings. Jeff McFadden, the director of the Union League, describes these clubs as "day camps for adults". Such clubs have had a hard time in recent decades. The ten-story Manufacturers and Bankers Club is now an office building, the prestigious Rittenhouse Club is shuttered, along with the Commerce Club, the Locust Club, and a dozen others. The most prestigious of all, the Philadelphia Club is in a decrepit neighborhood next to Broad Street, which it hopes will soon revive and make wrenching decisions unnecessary for the club. The interior is as close to an English city club as you could find, with immensely valuable paintings and furniture, creaking stairs and quaint bathrooms. You're not likely to find more than five members at lunch these days, but the food is excellent, the service superb, and the posted waiting list for membership quite comfortably long. The posted names tend to be a list of the cream of society, but most of them live thirty miles away. It's no longer possible to stay there overnight.

The Acorn Club is for women, quite frequently women whose husbands are members of the Philadelphia Club. If ever there were some political move to force the two clubs to abandon the men-only and women-only rules, a merger of the two would allow them to continue exactly as before as a single club with two facilities. The Acorn Club is just up Locust Street from the Academy of Music, and that is surely no accident. The place is immaculate, elegant, quiet, extremely well managed. Around the corner on 16th Street is the architect Horace Trumbauer's turn-of-the-last-century Racquet Club. In some other city, it might be called the Athletic Club, which makes it more attractive to younger members than the other clubs, where billboards would be the extent of the exercise. Indoor swimming pools and gymnasia are extremely heavy and thus require expensive steel supports. This club not only has a pool, but it also has squash courts (both old-rule and new-rule), racquets courts (the thirty-foot walls are polished slate), and one of the five court tennis courts still in existence in the country. Court tennis is a strange game, of which it is said that "if you know the rules and own your own racquet, you are one of the top ten in the country". But the game originated in the Twelfth Century and was what people meant by "tennis" until 1878, when a game is known as "lawn tennis" was invented and took the world by storm. One of the other five court tennis courts is a few miles from the location of the hydrogen bomb factory on the Savannah River, eighty miles from Charleston. The DuPont Company put it there, and the location is no accident. > is having a hard time filling its space with members, but it would be so appallingly expensive to replace even a part of it, that superhuman efforts are justified to preserve it. The Union League at Broad and Samson Streets, is the one outstanding exception to the decline of the center city men's club. When I joined it long ago, the strictest of rules prohibited women from any area except the women's dining room in the basement. I still remember the chairman of the admission committee, seated at the end of a long long table of gentlemen in the semi-darkness, intoning to me. "I'm going to ask you a question. And because I don't want any misunderstanding, I'm going to ask you twice. The question is, have you ever, even once, in any national, state or local election -- even once -- ever voted anything except straight Republican? Let me repeat, have you ever, even once. . . ?" Well, the League lets in Democrats these days, and even quite a few women. But what has transformed the League from a declining relic into a thriving center of the Philadelphia social scene has been management. The League owns its own new parking garage across Samson Street from the side door, which is itself an innovation with a canopy. The dingy old members overnight rooms have been transformed into a four-star hotel, with concierge. The old steam rooms are now a modern exercise facility, and a dozen computers in the "business center" are always occupied. The menu has been upgraded, the service snappy instead of sleepy. The upstairs dining rooms usually have several hundred people for dinner when formerly they were deserted. Several times a year the League has an upscale dinner party for five hundred or so guests, that would be in a class with a reception for the King of England. Nobody any longer asks why they should be a member; they only ask whether they can afford it. Apparently, lots of people can, once they have a reason to.

Over in a nearby short narrow street (we hesitate to call it an alley) near the Racquet Club, is the Cosmopolitan Club, for women only, thank you. It's small, probably would have trouble accommodating more than a hundred at a time, but the food and service are great. The real reason for the existence of this club is the wish of professional and working women to have a place to gather and support each other's morale, listen to uplifting speeches, help along with the younger ones and that sort of thing. In some ways, the Cosmopolitan Club is the most typical of all Philadelphia clubs. Henry George, Single Tax

Philadelphia was the birthplace of Henry George at 413 South 10th Street between Pine and Lombard, in 1839. The house has been restored to its 1839 condition and serves as the Philadelphia extension of the Henry George School for Social Studies, where you can take a course or two on the economic theories of Henry George, especially the Single Tax. If you do so, you can join the rest of us in pondering whether Henry George was a genius or a nut; he certainly combined some elements of both.

Leo Tolstoy no less, felt there was a conspiracy to keep people from knowing about the theories of Henry George, saying, "People do not argue with the teaching of George, they simply do not know it." In 1879 Henry George published a book, "Progress and Poverty which made him so famous he became a candidate for Mayor of New York City. Although he lost the election, he outpolled the third candidate, Theodore Roosevelt. The underlying thesis of his book would probably not find much approval among contemporary economists, who would likely say he was fooled by a cyclic increase in the value of land as an asset class. What he said was there was a remorseless trend of land to increase in value, while the proportion of wealth represented by labor and capital steadily diminished. Nevertheless, it can still be argued that: proceeding from the wrong premise about the causes of poverty, he might have propounded an attractive cure -- the single tax. Henry George asserted that we should stop taxing buildings ("improvements") and place all municipal taxes on land. There could be something to this. It is uncomfortably true that your taxes go up whenever you build a new building or substantially renovate an old one. The increased taxation of improvements is a disincentive to the building, renovating and improving a property. Placing taxes on the underlying land, by contrast, would create a positive incentive to build something and put the land to use. Evidence can in fact be produced that partial adoption of this principle has caused considerable prosperity in Pittsburgh, notwithstanding that city's recent flirtation with bankruptcy for unrelated reasons. Pittsburgh has shifted the proportion of real estate taxes from structures to underlying land, several times, and each time the change was followed by a demonstrable flurry of real estate development. Philadelphia had no similar flurries at those times, and it is said the contrast was caused by State Law which forbids such "discriminatory" taxation in first-class cities. Pennsylvania has only only one first-class city, Philadelphia, so you don't have to guess which city the Legislature had in mind. Before we let ourselves get too embittered by dirty politics, we should take a look at Arden, Delaware, which is another nearby town to try the Henry George approach. Arden is a little country suburb of Wilmington which became a summer art colony, with theater groups, especially favoring Shakespeare. Arden, which is Shakespeare-speak (in As You Like It) for the Ardennes Forest in France, applied the Henry George rules to taxing the land not the summer houses of the area. So, go take a look there at the result. More and more houses crowded closer and closer together -- on the same land. There's plenty of open land over the next hill where Arden supporters could drive or even walk in ten minutes, so the Henry George system is quite effective all right. But the effect is not entirely what was intended. Leo Tolstoy is gone, so someone else must unravel this riddle. The Kimmel Center: Comments On The Economics of Music

In 2001, The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts opened to the public, at a cost somewhat to the North of $200 million, and an annual budget in excess of $80 million. Although the generosity of Sidney Kimmel and Raymond Perelman must be gratefully acknowledged, and the ambitious energy of Philadelphia's political and musical worlds must be admired, there is little question that the city strained its resources to the utmost to achieve the new center. The Philadelphia Orchestra must appear on anyone's list of the best symphony orchestras in the world. It's likely going to stay there, too, because the orchestra stands on a wide base of associated Musical schools, chamber music groups, and intensely loyal musical audiences. As they say in baseball, they have a deep bench. Nevertheless, software piracy has just about eliminated an important source of income from the sale of recordings, seat prices are dauntingly high, other symphonies and other forms of entertainment have greatly improved in recent years. First-class musicians are not paid like sports stars, perhaps, but the top layer begin their careers with salaries in six figures, and top conductors commonly receive a million dollars a year, just like corporate executives. Between the high costs and the practical upper limit to what audiences will pay for a seat, about a third of the budget must be subsidized by some form of donation or fund-raising. It takes a lot of effort to raise thirty million a year. For reasons not entirely clear, the Kimmel center

is a free-standing corporate entity, whose main tenant (the Orchestra) owns a competitive music hall, the old Academy of Music. In other words, the capacity of Philadelphia's musical locations has been substantially increased. Increased, that is, beyond the metropolitan area's capacity to fill seats for classical music. A season's list of seventy-five productions may not fill the capacity, but the production schedule is limited by the fact that almost every production sustains a loss which must be made up by fund-raising. Following Julius Caesar's

motto that Fortune Favors the Brave, the leadership of the town has embarked on a daring musical exploit. The remarkable design team constructed the hall along highly innovative lines, based on movable wooden wall panels, controlled by computers. The hall itself becomes an instrument, slowly adapting and learning from each orchestral piece to produce an evolving product that no orchestra could produce without the hall to surround it. No one yet knows how far this idea can be taken, but it is possible to imagine four or five quite different versions of the same piece, each one recognizably distinct and with its own following. And revolving stages, adaptable hall design, and computerized modeling make it possible to have performing arts, not merely classical symphonies. It remains to be seen whether the designers can achieve perfection in a number of different forms, not merely limiting the design to a specialized version for a single purpose. If that works, capacity can be increased by redefining capacity. Just imagine what a wedding you could hold there. And just imagine how that worries the owners of the other six theaters in the neighborhood. In fact, just imagine how it worries the Philadelphia Orchestra to learn that there are plans to bring other visiting orchestras to town. Or how it worries other cities to hear that Philadelphia hopes to draw musical audiences from a long distance. There's going to be some creative destruction here, and some high adventure. Rail Station at Broad and WashingtonWashington Avenue was called Prime Street before the Civil War and was an important trans-shipment center for the whole country. Rail traffic, coming down from New York and New England, came through New Jersey on the Camden and (Perth)Amboy RR, disembarked, and ferried over Delaware to the foot of Prime Street/Washington Avenue. Passengers then took horse-drawn cabs up Prime Street to Broad, or else they walked. At that point, travelers bound for further South would enter the imposing Rail terminus of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore RR, to re-embark. Philadelphia hotel operators hoped they would stay overnight; Philadelphia merchants hoped they would just transact their business locally, then go back home. Taking nine hours from New York, it was an inefficient transportation method by today's standards, but the Prime Street interruption served local economic purposes, which Chicago keeps in mind, even today. Sketch map showing the area between Philadelphia and Baltimoreindicating drainage, cities and towns, roads, and railroads. Consolidated February 5, 1838. |

The interruption also worked the other way, inducing Southerners to go no further North with their business, thus strongly contributing to pro-Southern sympathies before the Civil War. Philadelphia was indeed the most northern of the Southern cities until the 1856 Republican convention (at Musical Fund Hall) started to remind other Philadelphians that the anti-slavery Quakers perhaps had a point. Even so, pro-Southern feeling in Philadelphia was wide-spread, even in the early months of the war.

|

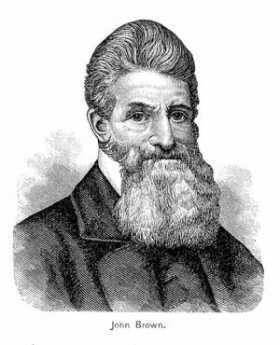

| John Brown |

For example, in 1859 John Brown's body was brought forth on the PWB railroad, precipitating a pro-Southern riot at the Broad and Prime Station. There was a second riot the following year.

During the Civil War itself, the PWB railroad was a major military transport, carrying military supplies and troops to the battles, and bringing the many wounded troops back home for treatment. Quite a large military hospital was built across Broad Street from the rail station. All in all, the corner of Broad and Prime was a major center of the war, and may well have been one of General Lee's objectives when he launched the invasion that got stopped at Gettysburg.

|

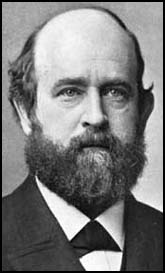

| B& O Railroad |

After the Civil War was over, attention was finally paid to the need for better North-South rail transport along the Eastern Seaboard. Up to that time, European investment had pushed American railroading in an East-West direction. The Baltimore and Ohio were aimed at the Mid-West, while the New York railroads aimed at Chicago and beyond. Local politics in the seaboard cities tended to keep the competitors from linking and thus potentially capturing trade between the manufacturing North and agrarian South.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore was the key link in the series of mergers which created the dominant Pennsylvania Railroad. Bringing northern traffic in through North Philadelphia to the new 30th Street Station,

|

| 30th Station |

and then linking it to the stub of the P, W, BRR, the way was being paved for Ascella Express trains to shoot from Boston to Washington, perhaps eventually to Florida. The side-track from West Philadelphia to Broad and Washington was allowed to wither, and of course, the whole Camden and Amboy RR became scarcely more than a trolley line All that was left as a challenge to the Pennsy was to get past B and O obstructionism in Baltimore. This last step was finally accomplished with the discovery of some legal loopholes related to an existing right of way for a local commuter line in Baltimore, where permission for a branch line was broadly interpreted, and a surprise tunnel dug to link it up to the other parts of the Pennsy. Amtrak passengers nowadays usually move through the Baltimore tunnel systems without noticing them, but occasionally a train breaks down inside the tunnels. Then, they prove to be rather dark and damp as the passengers with their laptops are transferred to another train.

Philadelphia in 1976: Legionaire's Disease

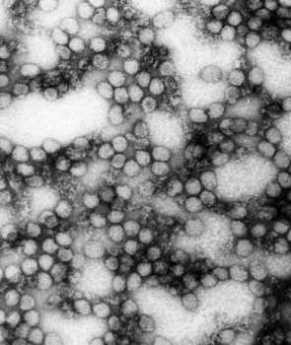

|

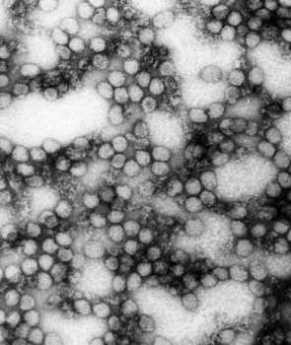

| The Yellow Fever |

No other city in America is remembered for an epidemic; Philadelphia is remembered for two of them. The Yellow Fever epidemic, for one, that finished any Philadelphia's hopes for a re-run as the nation's capital. And Legionnaire's Disease, that ruined the 1976 bicentennial celebration. One is a virus disease spread by mosquitoes, the other a bacterial disease spread by water-cooled air conditioners. Neither epidemic was the worst in the world of its kind, neither disease is particularly characteristic of Philadelphia. Both of them particularly affected groups of people who were guests of the city at the time; French refugees from Haiti and attendees at an American Legion convention.

In 1976, dozens of conventions and national celebrations were scheduled to take place in Philadelphia as part of a hoped-for repeat of the hugely successful centennial of a century earlier. Suddenly, an epidemic of respiratory disease of unknown cause struck 231 people within a short time, and 34 of them died. Every known antibiotic was tried, mostly unsuccessfully, although erythromycin seemed to help somewhat. The victims were predominantly male, members of the American Legion of a certain age, somewhat inclined to drink excessively, and staying in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, one of the last of the grand hotels. Within weeks, it was identified that a new bacterium was evidently the source of the disease, and it was named Legionella pneumophila. Pneumophila means "love of the lungs" just as Philadelphia means "city of brotherly love", but still that foreign name seemed to imply that someone was trying to hang it on us. Eventually, the epidemic went away, but so did all of those out-of-town visitors. The bicentennial was an entertainment flop and a financial disaster.

Since that time, we have learned a little. A blood test was devised, which detected signs of previous Legionella infection. One-third of the residents of Australia who were systematically tested were found to have evidence of previous Legionella infection. A far worse epidemic apparently occurred in the Netherlands, at the flower exhibition. Lots of smaller outbreaks in other cities were eventually recognized and reported. It becomes clear that Legionnaire's disease has been around for a very long time, but because the bacteria are "fastidious", growing poorly on the usual culture media, had been unrecognized. And, although the bacteria were fastidious, they were found in great abundance in the water-cooled air conditioning pipes of the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. Even though the air conditioning was promptly replaced, everybody avoided the hotel and it went bankrupt. When it reopened, 560 rooms had shrunk to 170, and it still struggled. Although there is little question that lots of other water-cooled air conditioning systems were quietly ripped out and replaced, all over the world, the image remains that it was the Bellevue, not its type of plumbing, that was a haunted house. There is even a website devoted to its hauntedness.

The Center of Town

|

| city hall |

It took two hundred years for the inhabited part of the city to reach the square which William Penn had envisioned for the center of his green country town, and by the time it did, the area around City Hall had come to resemble the town planning concepts ordinarily associated with the Scotch-Irish immigrants.

It sort of goes like this: the Scotch-Irish had been kicked out of Scotland and they were soon kicked out of Ireland, so they were far less emotionally attached to their local soil than other European groups. So they were probably the first group to regard real estate as a commodity rather than a repository of wealth, or a religious shrine, as other groups often do. It soon became evident to them that the best real estate was usually found at the crossroads, and the more important the intersecting roads, the more valuable that real estate was going to be someday. Accordingly, early Scotch-Irish settlers roamed around their new country, looking for likely crossroads, and buying up the local property for speculation.

The pattern of the diamond appeared, with a town square placed at the crossroads, traffic diverted around the square, and commercial real estate established around the rim of the square which usually had a flagpole placed in the middle of the central park. New England had city centers and town commons, but the two were usually not the same thing. The diamond pattern is very characteristic of rural Pennsylvania, and up and down the Appalachian valleys where the Scotch Irish had spread. It is the pattern of Philadelphia City Hall Square, no matter whose idea it was originally. Let's face it. City Hall is at a crossroad of the two main traffic arteries, Broad and Market Streets, wide and straight, stretching for miles in each direction.

Billy Penn's Hat

|

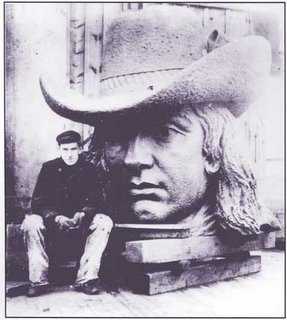

| Billy Penn's hat |

Philadelphia City Hall was intended to be the tallest building in the world, so there was no reason to suppose anything in Philadelphia would be taller. Gradually, taller buildings in other cities were built, but there grew up a gentleman's agreement that no skyscraper would be built in Philadelphia that was taller than William Penn's hat atop his statue on the tower of City Hall. Planning in the city was organized around this premise, which affects subways and other transportation issues in the city center. Because of assassination fears, a similar tradition in Washington DC was enacted into law, and it must be admitted that the flat skyline of that city looks a little dumb and boring. But Philadelphia neglected to pass a law, and so at the end of the Twentieth Century first one and then half a dozen skyscrapers were built that were twice the height of City Hall, immediately destroying the organizing visual center of the city. Pity.

But there are more serious issues involved. Aesthetics aside, who cares if someone bankrupts himself building an inappropriately tall building, with excessive elevator costs, problems with reinforced foundations, shortage of parking space, and the like? And the answer to that is the new tall building will bankrupt the older office buildings, not itself. Using offers of low, low rents to fill the new building, tenants will be drained from other spaces, and other areas of the city will deteriorate unless there happens to be a general shortage of office space in the region. Carried to an extreme, all of the center city business might be envisioned to reside in one thousand-story building, and the rest of the region would be a desert.

The obvious response would be that no landlord wants to have competition, and new construction is the way a city renews itself, creatively destroying the old to make room for the new. You must not allow the vested landlords to capture the political process with agitation if not bribes. Push things too far in that direction, and you will find that political corruption has destroyed the fabric of the town more effectively than a couple of skyscrapers ever could. Market East has been devastated, it is true. But that's the price of conducting the commerce of the region on the basis of market economics instead of through bureaucracy which masks corrupt politics with high-flown language. Paris is beautiful, but France has 12% unemployment which is closer to 16% if you remember the 30-hour week, the nine-week vacations, and retirement age in the fifties.

And yet, there is certainly a point to be made here. The height limit on new construction must bear some relationship to the regional need for new office space, and not merely rely on beggar-my-neighbor. We're currently hearing about two new projected skyscrapers, one beside 30th Street Station, and the other at 17th and Market/Chestnut. The decision to go or no-go will rest with whether the developers can find "lead" tenants. The corporate officers of these large enterprises are the ones who must be expected to give careful consideration to the best interest of the community because right now they are the ones who control matters. If they neglect their responsibilities, the pressure to pass more zoning laws will prove hard to resist.

Philadelphia's Big Ben

|

| Worlds largest bell in St. Petersburg, Russia |

The largest bell in the world is reported to be in St. Petersburg, Russia, but the second largest is in Philadelphia. No, it isn't the Liberty Bell, which is cracked and dysfunctional, but smaller in any event. The bell sound is so penetrating it seems to come from everywhere, so it isn't surprising that many people believe it must be coming from the tower of City Hall. That's fairly close, but in fact, the bell is atop the former PNB building across the street between Chestnut and Market. When that so-and-so rings, you feel it in your bone marrow even if you are five blocks away. Because it's so big, its note has a very long period of decay, with the result that when it rings it rings very slowly and deliberately.

People who have been there reported the surprising news that there is a penthouse apartment right underneath the bell, which is so well insulated that you can hardly hear the bell toll. Underneath that, however, are suites of offices where the ringing of the bell vibrates enough to knock the fillings out of your teeth. The law department of the Philadelphia National Bank used to be right in the midst of those offices. It's reported that the lawyers in the place were busy at 11 AM every day, inviting somebody, anybody, to go out for lunch. Meet you at the restaurant or club at 11:45.

HSP: Philadelphia's Attic

|

| Historical Society of Pennsylvania |

There was a time when the mission of the HSP (Historical Society of Pennsylvania) was clearly and proudly centered on the history of Philadelphia's old families. There generally comes a time in every family when its accumulation of stuff requires facing the fact that many possessions are too valuable to sell and too bulky to store. HSP in time became a place where families contributed these objects of memory and value, at least keeping them out of the hands of antique dealers when dusting and ensuring them became a burden. When many families entered into such a joint venture, the shared goals and experiences created a tradition over time which was reassuring to the donors. The famous lawyer Howard Lewis came to the board of HSP at a time when it was facing up to some of its own problems.

|

| Boies Penrose |

The then Board Chairman Boises Penrose came to the young lawyer one day and told him it was time he joined the board. Well, why? Because your grandfather was once Chairman of the Board; no other explanation was offered. Howard Lewis recounts that it was his introduction to a Philadelphia fact: some board appointments are hereditary. He dutifully joined.

It became apparent that HSP was a museum of immensely interesting artifacts, including decorations used at the Machianza of 1778, a copy of the handwritten originals of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and ten thousand other curious of great interest. It was a place to visit one's family relics, it was a great place to hold a party. It had a three million dollar endowment in 1969. But it had a big problem: essentially no one visited the museum. It isn't hard to imagine the anguish waiting for anyone who stirred up the hornet's nest by pointing out the obvious problem. You can't fire hereditary directors, so hereditary directors don't budge in an argument. You can make hired staff into scapegoats and fire them; that doesn't accomplish much, although it is commonly tried. The Genealogy Society is a natural partner of Philadelphia's attic, but although the two partners were intimately mixed, natural partners who can't be fired add to the scene.

Things went on. Boies Penrose held board meetings which lasted precisely forty-five minutes. He had a train to Devon to catch at 5:15, so meetings ended at 4:45 PM, precisely. Even when a speaker was in mid-sentence, the gavel banged down at 4:45. Eventually this impasse was broken by reaching an agreement with the Atwater Kent Museum to the effect that historical three-dimensional objects would go to the Atwater Kent, freeing up 40% more library space for the two-dimensional papers, maps, and documents which were to become the main focus of the new HSP. More separation between HSP and the Genealogy Society was effected. Much of this was made possible by the extraordinary investment ability of Ralph Kynette, who had run the endowment up to $18 million, in spite of maintaining a spending rule of 9%. There are not many non-profit organizations which can match such a performance.

The reorganized HSP floundered a bit, and then it had the good fortune to enter into a merger with the Balch Institute. The Balch also had a store of valuable papers, but its main mission was educational. The addition of this educational effort to the more static museum and library functions has allowed the recruitment of ambitious staff, and a considerable redirection from Olde Philadelphia to the city as it now is.

In the course of the many reexaminations which all this reorganization stirred up, some familiar issues in non-profit administration had to be faced. The American Museum Association is firm in its principles that no asset in the archives of a museum may ever be sold, except to purchase some other asset which comes closer to the museum's stated mission. The underlying sense of this rule is plain: it would be unfortunate for paid staff to sell artwork for the purpose of sustaining or raising their own salaries. Unfortunately, in a great many instances, collection value has grown more rapidly than the size of the endowment to preserve the collection. That's about the size of the problem at the Barnes Museum, where collections worth many billions cannot be touched to raise money to protect and display them. It is confidently asserted that the Barnes has many objects in its basement which could easily correct its endowment imbalance, but the AMA rule prevents it. The Barnes must now be moved to a new county to overcome this impasse. It all seems like an awkward way to solve one problem by creating another, but the lawyer in Howard Lewis takes it in quite an unexpected direction.

It is his view that locking the museums of the nation in this position creates a constantly shrinking market in the artwork; when a museum acquires a piece of art it forces it to enter a one-way tunnel, never to reappear on the market. A constantly shrinking market of salable art raises prices, and it does so in a way that resembles a violation of the Clayton Antitrust Act, the beneficiaries of which are the art dealers, art collectors and artists of the world. Add to this injury to competition, the tax benefits of creating or holding a constantly appreciating market; and it really is an uncomfortable thing to consider in depth. The American Museum Association ought give serious consideration to finding alternative routes to its legitimate goals. One of the other probably unintentional results of this rule are that the donation of a valuable piece of art to a museum is very likely to lead to its instant sale for cash. The reasoning here is that the donation has not yet been "taken into the collection", and thus it can be sold without violating the Museum Association rule. People who wear wigs while sitting on a bench may consider this a valid interpretation, but when you set about trying to fashion a better museum rule, this rebuttal seems highly contrived.

If we should someday set about to re-examine what we are doing in the legal thicket of museums, we might consider how the principles of non-profit accounting for museums might be fundamentally modified. Since a non-profit is thought to generate no profits, its financial health cannot be measured by the size of its profits. Consequently, it is traditional to account for the finances of a non-profit by measuring whether its assets have grown or declined. However, conducting an annual appraisal of all the artwork in a museum that never sells anything is a monumental expense without any other purpose than to satisfy the accounting rule. Consequently, I'll tell you a little secret. Absolutely everyone ignores the issue, and the annual audits are totally uninformative if not misleading. Who's going to hang the bell on this cat?

Effingham Buckley Morris

|

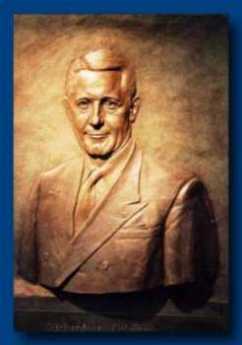

| Effingham Buckley Morris |

The vibrant chatter of schoolchildren is familiar at the Academy of Natural Sciences; its museum is a standard stop for local school trips and family outings. Effingham Buckley Morris, the president of the Academy from 1928 until his death in 1937, is largely to thank for the museum's youthful spirit. A giant of the Philadelphia banking community, Morris used his success in business as well as his connections to other local institutions to advance the Academy's outreach. In 1936, after conducting a comprehensive survey of the Academy's work, Morris and his associates announced the Educational Development Program. One goal was to create a specific Education Department, dedicated to educating children from local private and public schools. As Morris put it on the day of the Program's public unveiling, "We want a museum where ideas are on display rather than things." The Academy has certainly succeeded over the years in fulfilling Morris' ambitions.

Morris had quite a knack for inspiring people and institutions to think big and move in new directions. He was often quoted as having a unique ability to "enlist the loyal co-operation of his colleagues," garnering followers and supporters wherever he went.

A member of the well-known Quaker "Morris" family of Philadelphia, Effingham Buckley came from a long tradition of civic engagement. Effingham was born in the old Morris mansion on Eighth Street, the son of Israel Wistar Morris and Annis Morris Buckley. During his boyhood, he attended the Classical Academy of Dr. John W. Faires and then enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania for undergrad. It was at Penn that he began his long and illustrious career as a "leader," founding the College Boat Club and becoming one of the first presidents of the University Athletic Association. His popularity and vibrant spirit only grew as he established himself as an adult in the Philadelphia community. Although Digby Baltzell was later to immortalize a tradition of disdain for the diffidence and lack of distinction of Quaker-dominated Philadelphia, he certainly seems to have overlooked Effy Morris.

|

| Old Morris Mansion |

After receiving his graduate degree in Law from Penn, Morris worked exclusively in that field for several years. During this period of American expansion and economic growth, Morris was heavily involved in the booming railroad business throughout Pennsylvania, helping to settle deals during its various organizational forms. Because of its many mergers and acquisitions, a successful railroad mainly embodies a successful lawyer. During the long period when railroads were at the heart of the Philadelphia economy, a majority of railroad presidents were lawyers.

Perhaps the crowning achievement of Morris' career, however, was his wildly successful Presidency at the Girard Trust Company. One of his first moves as President was to set the company's important presence in stone through the construction of the Pantheon-esque Girard Trust Company building on Chestnut and Broad streets. Attached to this building, and now home to the Ritz Carlton hotel is a tall, impressive skyscraper that is also part of Morris' legacy. This white skyscraper had many critics during the days of its construction in 1888, but it was to become the first "office" building of its kind. Although the Witherspoon building at 13th and Chestnut makes the same sort of claim, the two Girard structures across the street still dominate the heart of the city today.

|

| Girard Trust Building |

During his career, Morris managed to become involved with a host of financial institutions in Philadelphia; he was the director of the Philadelphia National Bank, the Fourth Street National Bank, the Commercial Trust Company and a manager of the Philadelphia Saving Fund Society. He also became the trustee of large estates, including those of Anthony J. Drexel, and William Bingham.

Aside from his financial involvement in Philadelphia society, Morris was also an active member in its cultural societies. The Colonial Society of American, the Historical Society, and the Union League are just a few clubs of which Effingham Morris was a member. Morris also became a dedicated patron of the sciences, joining the board of the Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology and in 1928, donating to the Institute 150 acres of historic Pennsylvania land in Bucks County for the study of biology.

|

| New Ritz Carleton Hotel |

Effingham became a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1896. He was later elected Chairman of the Finance Committee in 1905, then to the Board in 1925 where he was then elected president in 1928. Effingham approached his presidency with caution and modesty, aware of his limited knowledge in the scientific field and often enlisting the advice of his so-called "alter-ego," and the Academy's future president, Charles M. B. Cadwalader. Morris used his unique skills and local connections to help the Academy grow in new directions and expand its educational capacities.

Morris remained active until his death in 1937 and was, in no doubt, a dominant force in the development of Philadelphia and the improvement of its institutions. His portrait in the Academy's Library serves as a reminder of the Institution's deep and historical connections to the Philadelphia non-scientific community.

17 Blogs

Working Girls Get the Faints

A publishing house employs myriads of young women. They faint a lot.

A publishing house employs myriads of young women. They faint a lot.

Mayors and Limos

Mayors sometimes want to be noticed riding around, and sometimes want to be invisible. They have been both.

Mayors sometimes want to be noticed riding around, and sometimes want to be invisible. They have been both.

Washington Square

All five of William Penn's city squares have proud and colorful histories . Washington Square, however, tops them all. It's had prisons, fish ponds, cemeteries, mansions, and skyscrapers.

All five of William Penn's city squares have proud and colorful histories . Washington Square, however, tops them all. It's had prisons, fish ponds, cemeteries, mansions, and skyscrapers.

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

The history of American medicine is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

The history of American medicine is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Sometimes it's hard for others to understand what makes Quakers tick.

Musical Fund Hall

Eakins and Doctors

Philadelphia's art world joined its medical world in reacting fiercely to Jefferson Medical College's sale of the best painting by the best artist of Philadelphia's Nineteenth century.

Philadelphia's art world joined its medical world in reacting fiercely to Jefferson Medical College's sale of the best painting by the best artist of Philadelphia's Nineteenth century.

Larger Clubs

No longer exclusively all-male (or, occasionally, all-female), the downtown club is changing its role but remains a social center of considerable importance.

No longer exclusively all-male (or, occasionally, all-female), the downtown club is changing its role but remains a social center of considerable importance.

Henry George, Single Tax

The Henry George idea of a single tax still lives on in a school run in his old house on Eleventh Street.

The Henry George idea of a single tax still lives on in a school run in his old house on Eleventh Street.

The Kimmel Center: Comments On The Economics of Music

Philadelphia needs more than one concert hall, but two of them may be more music than we can manage.

Philadelphia needs more than one concert hall, but two of them may be more music than we can manage.

Rail Station at Broad and Washington

Philadelphia in 1976: Legionaire's Disease

Philadelphia's ambitious Bicentennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence was ruined by an epidemic of a new disease that seemed to focus on tourists.

Philadelphia's ambitious Bicentennial celebration of the Declaration of Independence was ruined by an epidemic of a new disease that seemed to focus on tourists.

The Center of Town

The designs of the city squares, that of City Hall, in particular, follow the "diamond" pattern characteristic of the Scotch Irish, who were keen real estate speculators.

The designs of the city squares, that of City Hall, in particular, follow the "diamond" pattern characteristic of the Scotch Irish, who were keen real estate speculators.

Billy Penn's Hat

There was a gentleman's agreement not to build higher than the top of City Hall, but business is business.

There was a gentleman's agreement not to build higher than the top of City Hall, but business is business.

Philadelphia's Big Ben

The second largest bell in the world tolls at noon in Philadelphia. You can't overlook the sound, but many people don't know where it comes from.

HSP: Philadelphia's Attic

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania started out in 1824 as a repository of family treasures. Several mergers and changes of direction have given it a new mission.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania started out in 1824 as a repository of family treasures. Several mergers and changes of direction have given it a new mission.

Effingham Buckley Morris

Effingham Buckley Morris may not have thought of himself as a scientist but his love for Natural History brought the Academy of Natural Sciences much closer to the public and established the institution as an important component of Philadelphia. His banking career was a notable one.

Effingham Buckley Morris may not have thought of himself as a scientist but his love for Natural History brought the Academy of Natural Sciences much closer to the public and established the institution as an important component of Philadelphia. His banking career was a notable one.