3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Germanic Religious Sects

Refugees from a dissolving Catholic empire fled to America.

Touring Philadelphia's Western Regions

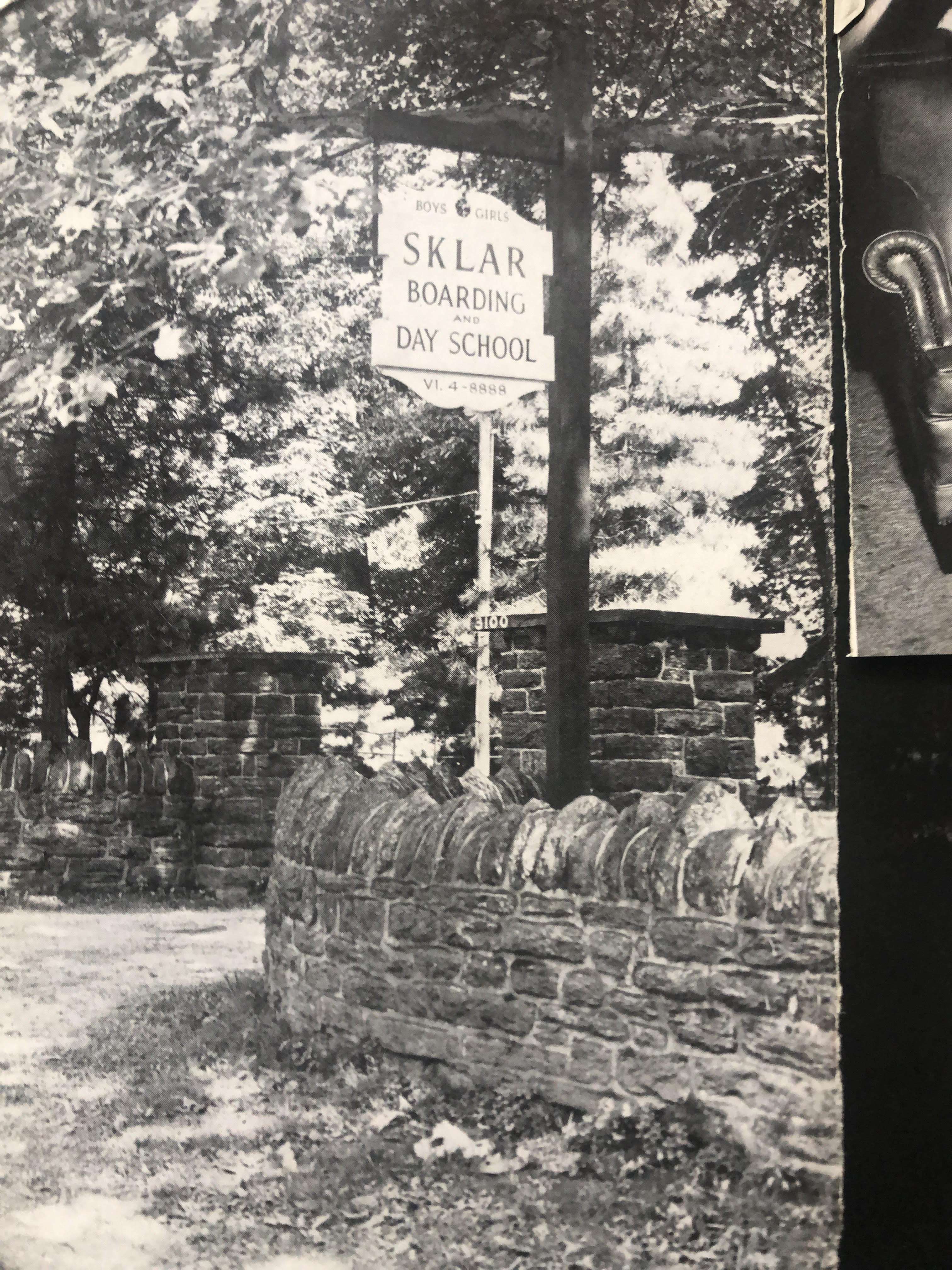

Philadelpia County had two hundred farms in 1950, but is now thickly settled in all directions. Western regions along the Schuylkill are still spread out somewhat; with many historic estates.

Short Tour of Philadelphia's West Country

Philadelphia County had two hundred farms in 1950 but is now thickly settled in all directions. Western regions along the Schuylkill are still spread out somewhat; with many historic estates.

|

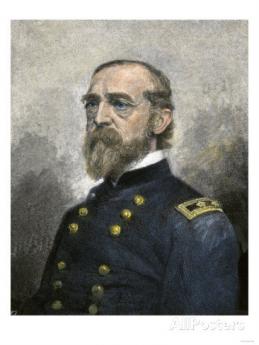

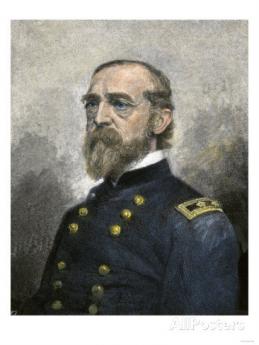

| Dr. Fisher |

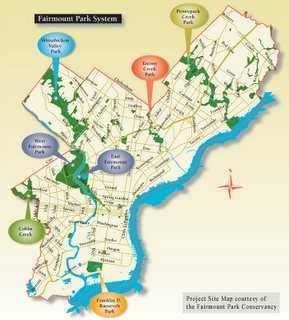

The Art Museum sits on an acropolis called Faire Mount, where William Penn planned to put his home. Fairmount Park, and hence the countryside, begins here and extends on both sides of the Schuylkill. It was once the industrialized terminus of barge traffic, but was restored to parkland as a water purification project in the Nineteenth Century after agitation by the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. The area was briefly a vast Civil War encampment, then the site of the 1876 Centennial, remnants of which remain. Its inner loop including the historic houses in the park is interesting enough to make a tour of its own; on this trip we just skirt the area.

|

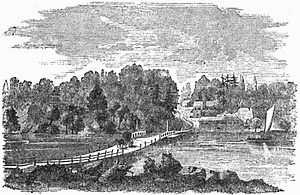

| Fairmount Park |

To begin the outer more general tour, go west over any one of the several Schuylkill bridges, turn right on 33rd Street in the general Drexel University/University of Pennsylvania area, observing many ancient mansions of a once-elegant place to live. Go past the Zoo, then up Belmont Avenue through the Centennial Grounds to City Line Avenue. Our first destination is Harriton, the original house in the Welsh Barony, called Bryn Mawr when it was built. Be sure to use a good map to find this large but hidden estate. It was the home of the first Secretary of the Continental Congress and its architecture set the style for the whole Main Line.

From here we carefully follow a map to the Barnes Museum in Merion. After acrimonious debates and clearly against Dr. Barnes' wishes, the vast collection of French Impressionist art is being moved to a new home on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Before it goes, you still have a chance to see the original concept in its intended setting.

From here we take a circuitous route to Germantown to see America's first suburb, with the Chew Mansion that cost Washington the battle of Germantown, Grumblethorpe, Stenton, and Schoolhouse Lane. A side trip to Temple University to see some portraiture if there is time, then down the Wissahickon Creek past Rittenhouse Town, eventually down Kelly Drive past the Schuylkill Navy, and over to the Art Museum (or alternatively the Water Works) for a nice lunch.

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

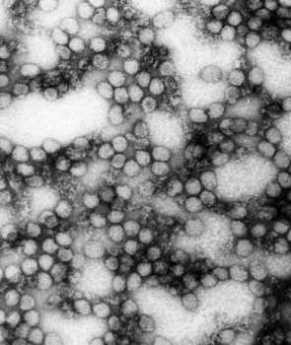

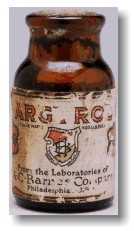

| A bottle of Argyrol |

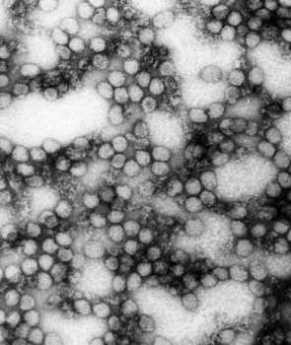

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |

Since the Foundation is currently strapped for ready cash, Judge Stanley Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court is now being urged to allow the Foundation to break Barnes' will in some way or other. Move the museum to downtown Philadelphia where it can attract more paying visitors. Sell some of that land. Sell some of those paintings in the cellar. Fire some of those employees. But all of these suggestions are short-term solutions, which may injure the long term. Everybody has an idea of what Barnes the rich eccentric would have done if he were alive to do it, but I suspect he would have rejected the whole lot. Barnes the shrewd investor would have taken the most expensive painting off the wall, and sold it to the highest bidder. Buy low, sell high, and the niceties of non-profit professionals are damned. Barnes wasn't in love with one single painting, or one particular school of painterly interpretation, he was in love with Art.

Investment theory has improved in the past fifty years; there have even been some Nobel prizes awarded for new insights. But it still isn't possible to put an investment portfolio on autopilot for perpetuity. Every museum, university, and the foundation has the same problem, with the result that the landscape is littered with the bones of perpetual organizations destroyed by following a fixed formula. With the singular success that Barnes displayed, it isn't surprising that he went a little too far with instructing his successor trustees in what to invest in. Never sell the paintings or the real estate, avoid the common stock, were ideas that worked brilliantly, and may even work most of the time. But sooner or later, the institution will be endangered by following them too literally. Somebody has to have some flexibility. But there is something else that is inevitable, too. Sooner or later, whether it takes fifty years or five hundred years, sooner or later someone will be given the responsibility and the necessary flexibility -- but will try to run off with the boodle, for himself. The balance between necessary prudence and necessary flexibility is impossible to maintain forever, and the Judge will surely have a hard time deciding what Barnes would have decided.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (2)

|

| Art Museum |

There are a number of residential relics along the Parkway, but in general the idea seems to have been to put governmental buildings there, in a sort of French-like celebration of governmental glory. There is the Youth Study Center, the Department of Education administration building, the Boy Scouts of America, the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, and of course the tower of City Hall at one end and the Parthenon-like Art Museum at the other. But this is Philadelphia, and certain small touches of the town are tucked among the European grandee design.

For example, WFLN (now WWFM) the original FM classical music station, had its studio tucked in a little building just behind the Cathedral. Ralph Collier would interview authors and city visitors there during the lunch hour, in a studio that was little more than a closet, while someone else changed records in a room downstairs. Somebody from New York once said that Ralph didn't seem to know how good he really was, which is a way New Yorkers like to talk. Ralph was, the just about the only interviewer who had actually read your book before the interview. In 1997, WFLN was sold for forty million dollars, which ought to impress even a New Yorker.

Logan Circle is bigger than it looks, primarily because the windows are set 100 feet high. This came about after the anti-catholic riots of the Civil War era, which made it advisable to put stained glass higher than most people can throw rocks. There is usually a cardinal in residence at this cathedral, and Cardinal Bevilacqua the much-respected lawyer-cardinal is now just retiring in favor of an incoming occupant from St. Louis. Cardinal Krol was famous in the past for his opposition to Pope John's Vatican Constitution, which he refused to allow to be translated into English. Before that, was Cardinal Dougherty, who is remembered for being considerably overweight. Cardinals are addressed as Your Eminence, and Cardinal Dougherty was (very privately) referred to as You're Immense. He was perhaps most famous for the Legion of Decency , an effort to make motion pictures more socially acceptable. The story is told of a 12-year-old girl who stood up and told the Cardinal that she didn't agree with him, she liked movies. The next day, her father, the most powerful Catholic banker in Philadelphia, had to go to the Cardinal and humble himself to make amends.

|

| Amelia Earhart |

Franklin Institute was originally on 7th Street, where the Atwater Kent Museum of Philadelphia History is now located. Much of the money to build it came from a $5000 bequest from Franklin himself, which was intended to demonstrate the power of compound interest over a period of time. It is part science museum, part memorial to Philadelphia's most famous citizen. It has a Planetarium, locomotive, a passenger airplane, Amelia Earhart's plane, a huge replica of a human heart, and thousands of working demonstrations of electrical phenomena. Ben Franklin's huge statue sits in a grand marble rotunda, where socialites occasionally hold receptions and weddings. But between the two extremes is the most interesting combination of museum and memorial -- a series of demonstrations of Franklin's most important scientific discoveries, utilizing the same instruments he used. Just a little effort at understanding these exhibits will convince any educated adult that Franklin was truly a genius.

Almost next door to the Franklin Institute is its more venerable neighbor, the Academy of Natural Sciences. The Academy is an offshoot of the American Philosophical Society, itself (originally founded by Franklin) and has a distinguished history of discovery and research of its own making, not merely a display of the work of others. Most school children will recognize the famous display of dinosaurs, including the First Dinosaur ever unearthed intact (in Haddonfield).

|

| Art Museum |

The Art Museum was intended to inspire awe, and it does. The builders ran out of money before the decorative friezes could be completed, but that even enhances its resemblance to the Parthenon, where the friezes were blown off in various wars. It's a little hard to know how to respond to the criticism that the building overwhelms its contents. Perhaps it is true that the creaking floorboards in Madrid's Prado Museum show off the treasures on its walls, but there is also little doubt that Spain (or Boston) would replace the floors if it could afford to. Although the City of Philadelphia has a little trouble finding the money to maintain and guard the Museum, the masonry is ultra-solid, it's very big, and will endure for ages to come. The collections slowly grow, benefaction by benefaction. The traveling exhibits are clearly the center of Philadelphia culture. And there, at the top of the stairs without any clothes on, is Diana of fame and fable. Her perfectly straight back is the true essence of the famously beautiful Philadelphia woman, like Fannie Kemble, Rebecca Gratz, Evelyn Nesbitt,Cornelia Otis Skinner, Grace Kelly, and Katherine Hepburn.

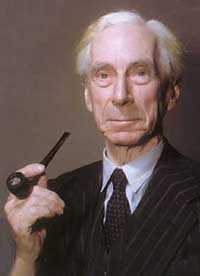

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

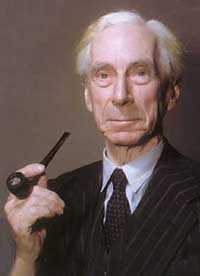

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Contemporary Germantown

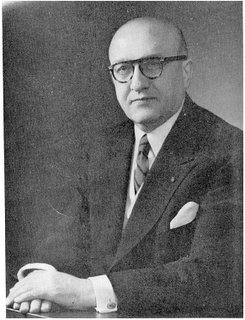

The Strittmatter Award is the most prestigious honor given by the Philadelphia County Medical Society and is named after a famous and revered physician who was President of the society in the 1920s. There is usually a dinner given before the award ceremony, where all of the prior recipients of the award show up to welcome to this year's new honoree.

|

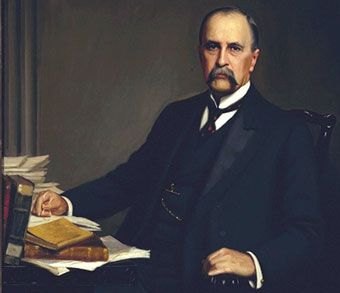

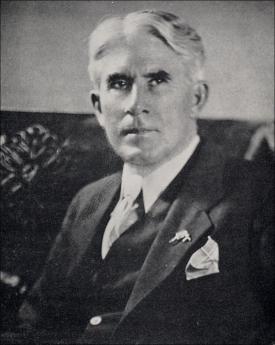

| Bockus |

This is the reason that Henry Bockus and Jonathan Rhoads were sitting at the same table, some time around 1975. Bockus had written a famous multi-volume textbook of gastroenterology which had an unusually long run because it was published before World War II and had no competition during the War or for several years afterward; to a generation of physicians, his name was almost synonymous with gastroenterology. In addition, he was a gifted speaker, quite capable of keeping an audience on the edge of their chairs, even though after the speech it might be difficult to recall just what he had said. On this particular evening, the silver-haired oracle might have been just a wee bit tipsy.

Jonathan Rhoads had likewise written a textbook, about Surgery, and had similarly been president of dozens of national and international surgical societies. He devised a technique of feeding patients intravenously which has been the standard for many decades, and in his spare time had been a member of the Philadelphia School Board, a dominant trustee of Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, and the provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Not the medical school, the whole university, and is said to have been one of the best provosts of the University of Pennsylvania ever had. When he was President of the American Philosophical Society, he engineered its endowment from three million to ten times that amount. For all these accomplishments, he was a man of few words, unusual courtesy -- and a huge appetite in keeping with his rather huge farmboy physical stature. On the evening in question, he was busy shoveling food.

"Hey, Rhoads, wherrseriland?". Jonathan's eyes rose to the questioner, but he kept his head bowed over his plate.

"HeyRhoads, Westland?" The surgeon put down his fork and asked, "What are you talking about?"

"Well," said Bockus, "Every famous surgeon I know, has a house on an island, somewhere. Where's your island?

"Germantown," replied Rhoads, and returned attention to his dinner.

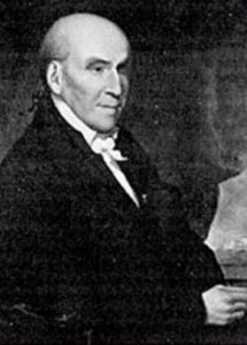

Donor Intent

At least three of the greatest treasures of Philadelphia are now used in ways that almost certainly flout the expressed wishes of the donor. Steven Girard's

|

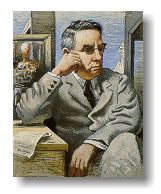

| Alfred Barnes |

bequest for the enhancement of "poor, white, orphan boys" is now devoted mostly to black children, many of the girls, many of them non-poor by some definitions, and many of them orphans only in a limited sense. Alfred Barnes wanted his art treasures to be used for education, outside the city of Philadelphia which had offended him, and definitely not part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art which he disliked. They are now to be moved to Philadelphia's Parkway, close to and under the thumb of, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. John G. Johnson's immense art collection now resides within the Museum of Art in spite of the firm declaration by this eminent lawyer that it was to remain in his house, and definitely not to be used to promote some huge barn of a museum.

|

| William J Duane |

It's hard to imagine how any set of instructions could be devised to be more clear than these. Barnes employed a future Supreme Court Justice, Owen Roberts, to write his will. Girard similarly employed the preeminent counsel of his time, William J. Duane, to devise an extraordinarily detailed set of instructions. John G. Johnson was himself considered to be the most eminent lawyer in the city. In fact, he once received a fee of $50,000 for his opinion about a corporate financial plan, consisting of the single word "No" scrawled on its cover.

It would be interesting to know whether these famous cases are typical of the way wills are treated, either in this city or in the nation generally. Perhaps they are notorious mainly because they are so unusual. But perhaps they are indeed rather representative and stand as lurid examples of the general failure of the rule of law. Perhaps they reflect some deeper wisdom of the law, where Oliver Holmes intoned that the standard was not logic, but experience.

<Perhaps some guidance can be found in the decisions of Lewis van Dusen, Sr. who for several decades established the Orphans Court of Philadelphia as a model for the world to follow. Someone seems to have thought he set a good example. But was his reign an exception, or a glowing example of the triumph of society's wisdom over the crabbed grievances of dying millionaires in their dotage?

These remarks are made while the newspapers are filled with the story of a Texas billionaire who married a magazine model fifty years younger than himself. Some prominent local heiresses are known to have run off with their stable boys. Indeed, you don't need to read many tabloids to see a dozen examples of such behavior. Is it possible that some of them were acting up out of frustration at the probable betrayal by the courts of more reasoned instructions for their wealth?

East Falls

|

| Kelly drive |

The views along the charming, curving, leafy East River Drive from the Art Museum to the (former) Falls of the Schuylkill are dominated by rowing and the rowing clubs, so it isn't surprising that Philadelphia's most famous oarsman, John B. Kelly, used to live in East Falls, the residential area just at the end of the rowing area. I was once sent to see him by a mutual acquaintance when we were considering buying a house in his neighborhood. "East Falls," he said, will remain a nice place as long as I am alive but not longer than that." He might have added the names of Connie Mack(Cornelius McGillicuddy) the fifty-year owner and manager of the Philadelphia Athletics who lived on Schoolhouse Lane, and Harry Robinhold, who lived on Warden Drive and was the only real estate agent who ever seemed to have properties available in the area. But the friendly warning that Kelly was intoning seemed quite plausible, and we didn't buy the house.

|

| Roosevelt Blvd. |

There seems to be no question that Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner were married in Philadelphia in November 1951 and that Jimmy Duffy did the catering. It's only hearsay, strongly asserted, that the wedding took place in a big white house at the corner of School House Lane and Henry Avenue. That would, I believe, be the house where Connie Mack the baseball team owner and manager, lived. Just what connection these movie stars had with Connie, or with Grace Kelly who lived a block away, is undocumented but strongly suggested.

|

| Arlen Specter |

Decades later, however, East Falls continues to be a curious little cluster of three thousand houses, very close to the center of town but leafy and suburban, surrounded by other neighborhoods which underwent serious urban decay long ago. The Wissahickon Valley on one side,Roosevelt Expressway on a second, and the Schuylkill River on a third give it physical isolation, and the brow of the hill is held apart from West Germantown by a couple of large schools and college campuses. Even the strip of small commercial businesses along East River Drive serves to discourage random wanderers. But that's just as true further East along the comparable strip near the Delaware, where it doesn't have the same result.

More likely, the fact that so many judges and politicians live there (the list includes Mayor Governor Rendell and Senator Specter) guarantees police protection of a high order, and probably also makes inconvenient government construction, or regulation, highly unlikely. The local school is good, the local private schools are even better. If you are ever seeking to improve local residential amenities (and real estate values), you ought to study what it is that enhances East Falls, and quietly act on your discoveries.

East Park Jingle

T he Paoli Local makes so many stops from 69th Street to Paoli, and those suburban stops look so much alike, that a dozing passenger can suddenly realize that he doesn't know whether he's gone past his intended stop or not. The conductor may shout out the station, but is it before, or after? To help with this problem, some wag composed a little jingle --"69 Old Maids Never Wed And Have Babies", which helps remember 69th street, Overbrook, Merion, Narberth, Wynnewood, Ardmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr. There's more to the jingle for further stops, but it gets a little raunchy. And anyway, Bryn Mawr students get off at The College, so further stations are safely ignored.

|

| Fairmount Park |

In view of the success of the Main Line jingle, it is tempting to compose small doggerel to assist remembering the forty or so points of interest in Fairmount Park. The old Park Trolley line stopped running in 1946, so we must look further for a logical modern sequence. Marion W. Rivinus has provided an ideal model in her charming little book "Lights Along the Schuylkill", now unfortunately out of print. The charming book contains a succession of sketches and comments about the houses and history of Fairmount Park. The book kindly begins and ends with a map of the park, the locations all numbered, in a sequence which is a perfectly acceptable guide to a complete tour by today's roads. There are a dozen acceptable ways you might wander around the Park, but to see everything would take a week and so for anyone to follow Mrs. Rivinus' tour precisely is improbable anyway. Nevertheless, her numbered sequence, without ever saying so, is the suggested itinerary of someone who knows and loves the park better than anyone. Since several members of her family were members of the original Park Commission, she comes by it all by inheritance, She's very small, and very sprightly, quickly dominates any group who are visiting one of the Park Houses for a party, and has lots and lots to say. She surely will not be offended to have it generalized that her age is North of 80; if she wants to adjust that statistic further, you will have to ask her. Philadelphia really needs to have her book republished.

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

So, begin at the Art Museum with the portion of the park which is on the East side of the Schuylkill. The jingle we offer begins "An Eager Walker Brings Hot Chocolate" (Art Museum, Eakins Oval, Water Works, Boat House Row, Lemon Hill, Cliffs) for the visible and famous anchor of the Park, the culmination of the rather grand promenade of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Notice first the general lay of the land.

|

| City Hall |

The motorist driving West from City Hall starts to weave through traffic and then starts to careen around curves of the East River Drive, now called Kelly Drive. Absorbed in the intricacies of urban driving, the motorist often fails to look up to the right and notice that he is really driving past the end of an elevated plateau. The cliff end rises sharply enough that the modern commuter often does not realize how short a distance to the right it is to quite another world. The river makes two right-angle turns, with a large lake or reservoir along the top of the first point. The East Park Reservoir covers about twenty-five square blocks of land, with colonial-era houses along the river rim, and the very dense urban area stretching off on the other side of the reservoir. The western edge of the forty-five acres of Girard College comes pretty closes to the edge of the park. If you drive from the edge of the cliff overlooking the Schuylkill, around the reservoir, and then down the side wall of Girard College, it is quite a shock to go from 18th Century mansions, woods, and pastures suddenly into what cannot honestly be called anything but a slum. A huge teeming slum, that seems to stretch on, forever. But back at Laurel Hill on the western edge, you walk a few steps from the road to the front door; if you walk straight through to the back porch, it is only fifteen steps from a spectacular view of the wooded river valley, and the edge of a very steep cliff. Although the Randolph family lived here and gave it the current name, Laurel Hill was the country seat of the Rawle family, which also graces the name of the oldest law firm in the country.

The southern end of this central north-south ridge of Philadelphia is now called Lemon Hill. It was the site of William Penn's intended manor house, until he later relocated to Pennsbury, up near Trenton. In time 300 acres of the area became -- by way of Tench Francis -- the country home of Robert Morris, probably the richest man in America and masterful financier of the Revolution. There is little question The Hill became the most glamorous social center in America, with George Washington staying overnight many times, and Martha Washington becoming a firm fast friend of Robert Morris' wife Molly White Morris, sister of William White, first Episcopal Bishop in America. It's true there were real lemon trees on The Hills, also true the estate was sold at sheriff's sale when Morris got thrown into debtor's prison for three years. The cause of his financial collapse was not the Revolutionary War, but overzealous speculation in real estate in the District of Columbia when it was decided (against his loud objections) to move the Nation's capital to the swamps of the Potomac. Morris was a great patriot for his country and his city, but he was also a bold and reckless speculator. Eventually, it caught up with him. Since the loss of the Capital was the greatest defeat Philadelphia ever experienced, it could easily be supposed the judges of his bankruptcy were unsympathetic with his attempt to profit from the deal.

There is only a thin shelf of land, scarcely wide enough for the East River Drive, at the foot of the cliff from the Water Works to the Wissahickon Creek, so most of the interesting houses are up at the top of the ridge. It is all a driver can do to stay on the twisting road and notice Boat House Row, with skulls on the river, without looking up to the right to see what's interesting. Many of the houses, like Woodford of William Coleman (Ben Franklin's lawyer). Laurel Hill of Francis Rawle, Mount Pleasant that was almost sold to Benedict Arnold, the Thompson family's federalist mansion called Rockford, and Charles Thompson's Somerton, later acquired by Judge William Lewis and now called Strawberry Mansion, were homes of prominent leaders of the American Revolution. Other houses in the neighborhood belonged to Tories. The Franks of Woodford almost became Arnold's neighbors while David Franks was smuggling letters to Major Andre, Joseph Galloway was Provost Marshall of Philadelphia during the British occupation, so his home, Ormiston, was confiscated when he left town along with General Howe. Two houses were moved to the premises, sort of destroying the dream of the preservationists to have it just the way it once was. Although Hatfield House was built in 1760, it was originally on Hunting Park Avenue and moved, stone by stone, to Fairmount Park in 1930 at the expense of the Hatfield family. And finally, Grant's Cabin. It's really pretty interesting to see the two-room cabin where General and Mrs. Grant lived for five months, overlooking the James River while Grant was concluding his campaign that led to surrender at Appomattox, issuing orders to Sherman and Sheridan, and receiving the visits of Lincoln, Meade and the Confederate Commissioners suing for peace. It's highly interesting to have Grant's headquarters displayed in our park, but, well, it seems a little out of place if you know what place you are visiting.

Let's extend our little doggerel. It begins with "An Eager Walker Brings Hot Chocolate;" and goes on "Most real Olympic runners won't stop." That's Mount Pleasant, Rockland, Ormiston, Randolph, Woodford, and Strawberry Mansion.

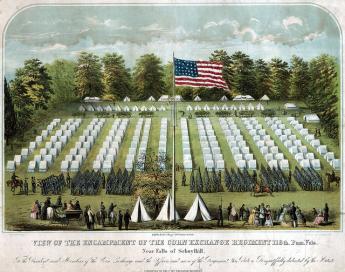

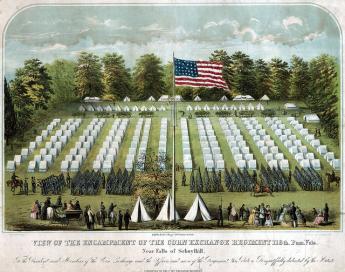

Encampment At East Falls

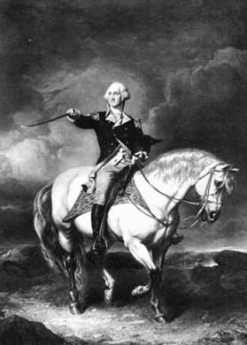

The urban intersection at Queen Lane and Fox Avenue in East Falls is a busy one, and except for a few stately residences, it easily escapes notice by commuters. However, the landscape forms a bowl atop a steep hill, fairly near the Schuylkill River. George Washington had evidently picked it out as a strong military position near the Capital at Philadelphia, either to defend the city or from which to attack it, as circumstances might dictate.

|

| Encampment at East Falls |

Washington's plans and thought processes are not precisely recorded, but when Lord Howe had sailed south from the Staten Island- New Brunswick area, he ordered his troops to head for an East Falls encampment at the southern edge of Germantown. Crossing the Delaware River at Coryell's Ferry (New Hope), the troops marched inland a few miles and then down the Old York Road to this encampment. Their stay at the beginning of August 1777 was quite brief because Washington changed his mind. When it took Howe's fleet longer than expected to appear in the Chesapeake, Washington became uneasy that Howe might be conducting a feint designed to draw the Continental troops south, and after cruising around the coast, might still return to attack down the undefended New Jersey corridor from Perth Amboy to Trenton. That proved wrong, but in Washington's defense, it must be said it was a plan that had actually been considered by the British. Anyway, Washington ordered his troops to pull out of the East Falls encampment and march back up Old York Road to Coryell's Crossing, which would be a more central place to keep his options open for the time when Howe's true intentions became clear. Washington and his headquarters staff went on ahead of the main body of troops, setting up headquarters at John Moland's House a little beyond Hatboro and a few miles west of Newtown, Buck's County. The Hatboro area was a pocket of Scotch-Irish settlement, without any local Tory sentiment, thus preferable to the rest of largely Quaker Buck's County.

To jump ahead chronologically, the East Falls encampment site must have seemed agreeable to the Continental Army, because a few weeks later it would be sought out as the main refuge and regrouping area, following the defeat at the Battle of Brandywine. The American troops were to withdraw from the Brandywine Creek when Washington realized he had been out-flanked, and head for Chester. Quickly recognizing that Chester was vulnerable, they headed for East Falls. Not only was Washington preparing to defend Philadelphia at that point, but was using the Schuylkill River as a defense barrier. As he had earlier done at the Battle of Trenton, he ordered all boats removed from the riverbanks, and artillery placed at any likely fording places, all the way up the Schuylkill to Norristown. Having accomplished that, this extraordinary guerrilla fighter then moved his troops from Germantown up the river to defend the fords. Meanwhile, Congress decided to move to the town of York on the Susquehanna, just in case.

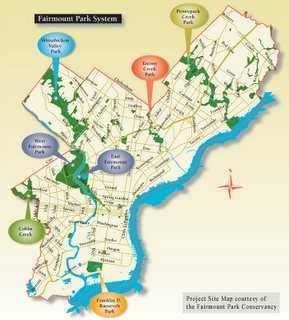

Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust

|

| Philadelphia's Fairmount Park |

New York's Central Park was created when it became clear there would be no park unless it was deliberately planned and its boundaries vigorously defended against real estate developers. Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, on the other hand, was to some degree a slum clearance project. The swift waters of the Wissahickon provide excellent power sources, provoking the construction of many mills. With steam power, they were abandoned, leaving desolate industrial hulks that blotted the landscape. Fairmount Park cleared out the remains of deserted mills, which had moved upriver to Manayunk, closer to a supply of coal. Fairmount Park was a creation of the Pennsylvania State Legislature, but the State never funded it. And it has thus always been somewhat larger than the City could afford.

In the early 1990s a beleaguered City government reached a public/private accord as a result of a commissioned study of the matter, which essentially urged that the city government should run the recreational programs in the parking area, and the private sector should be asked to do its best with land and historic building preservation. The William Penn Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and other philanthropic organizations banded together to form the Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust. Among its functions was to coordinate the many organizations which had been formed to preserve small areas of the park, as a result of the concerns of neighborhoods or descendants of former owners of historic homes. The Fairmount Park Trust finds itself in charge of over 400 houses, of which about 250 are genuine of historic value. They have to be preserved against vandalism and vagrants, mainly they have to be preserved against decay. Someone has to use them, and for that, someone has to spend money to fix them up and maintain them. If that is to happen, someone else has to set standards for preservation that balance the historic values with the need for some kind of present usage. Since few people would be willing to spend money and put up with uneconomical regulations if the building belongs to the park, the management of the Trust must manage and oversee very long-term leases. Obviously, the Trust must know what it is doing, have the wisdom to be innovative, and endure a fair amount of harangue by disappointed developers.

And it must supply some things which are hard to find, like advice and know-how about fixing up historic buildings of a certain age and history. The Trust has actually gone into the business of doing historic preservation for a fee, on its own property and elsewhere (Christ Church burial ground is an example). It thus generates some income to supplement philanthropic contributions. There is no requirement that prospective tenants must be non profit, only that the entity be of value to the neighborhood, and there are other signs that the Trust intends to be far-sighted and imaginative in the goal of making the Park something to be proud of, from the nearest to the farthest corner.

One idea suggested for further coordinated action might be to search for types of underbrush which would be repellent to deer who destroy the forest understory. Or, to search for particularly tasty "bait" shrubs which would draw the deer away from areas needing preservation. The combination of both ideas might lead to a natural balance, which would be unlikely to come about by the action of small local preservationists. Meanwhile, there are too many deer, and someone has to decide how and when to "cull the herd". That's how, in a small way, the trust got into the venison business.

So far, the Trust has preserved about 25 houses in the past ten years. That's a marvelous achievement, but it will take a century to complete the whole park unless momentum picks up. The Trust sort of needs an impresario of some kind or other to stir up public support.

Germantown After 1730

|

| German Quaker Home |

The early settlers of Germantown were Dutch or German-speaking Quakers. They were proud of the craftsman class but, unfortunately, that made them rather poor subsistence farmers. With a whole continent stretching beyond them, professional farmers would not likely choose to settle on a stony hilltop, two hours away from Philadelphia. Germantown's future lay in religious congregation, in papermaking, textile manufacture, publishing, printing and newspapers. Plenty of stones were lying around, so stone houses soon replaced the early wooden ones. Since Philadelphia in 1776 had only twenty or so thousand inhabitants, and only thirty wheeled vehicles other than wagons, it was not too difficult for Germantown to imagine it might eventually eclipse that nearby seaport full of Englishmen. Two wars and two epidemics brought those Germantown dreams to an end, but in a sense, those calamities were stimulants to the town, as well.

In 1730 real German peasants began to arrive in large numbers from the Palatinate section of the Rhine Valley. They arrived as survivors of a horrendous ocean sailing experience, packed in such density that it was not unusual to find dead bodies in the hold, of passengers that had only been supposed to have wandered into a different part of the ship. Quite often, they paid for their passage by selling themselves into what amounted to limited-time slavery, and a customary pattern was for parents to sell an adolescent child into slavery for eight or ten years in order to pay for the voyage of the family. They were uneducated, even ignorant, and often were proponents of small new religious sects. All of that made them seem to be a primitive tribe in the eyes of the earlier settlers. But they were professional farmers, and good at it. They knew, and a quick tour of Lancaster County today confirms their belief, that if you had a reasonable amount of very good land, you could live a life that approached that of the craftsmen in comfort, and usually far exceeded them in personal assets. They have therefore taken a long time to rise from farm to sophistication, while the already sophisticated craftsmen in Germantown wasted no time in abandoning farming. The peasant newcomers arrived in Philadelphia, made their way to nearby Germantown, learned a little about the new country and the refinements of their Protestant culture -- and then pressed on to the great fertile valley to the West, where the way had been paved by those twenty-five German families who had landed on the Hudson River several decades earlier and come down the Susquehanna via Cooperstown. Only a minority of the after-1730 Germans stayed on permanently in that steadily growing little German metropolis on a hill, and none of the very earliest German pioneers further west had even landed in Philadelphia.

During this period, this Athens of German America also invented the Suburb. The pioneer of this concept was Benjamin Chew, the Chief Justice, who built a magnificent stone mansion on Germantown Avenue, which was to become the main fortress of the Battle of Germantown in the Revolutionary War. Present-day visitors are still impressed with the immensity and sturdy mass of this home. Grumblethorpe, Stenton and a score of other country homes were placed there. Germantown in 1750 still wasn't a very big town, but it was plenty comfortable, quiet, safe, intellectual and affluent. Its first disruption came from the French and Indian War.

Germantown and the French and Indian War

|

| The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army |

Allegheny Mountains from which to trade with, and possibly convert the Indians, the French had a rather elegant strategy for controlling the center of the continent. It involved urging their Indian allies to attack and harass the English-speaking settlements along the frontier, admittedly a nasty business. The survivors of General Braddock's defeated army at what is now Pittsburgh reported hearing screams for several days as the prisoners were burned at the stake. Rape, scalping and kidnapping children were standard practice, intended to intimidate the enemy. The combative Scotch-Irish settlers beyond the Susquehanna, which was then the frontier, were never terribly congenial with the pacifism of the Eastern Quaker-dominated legislature. The plain fact is, they rather liked to fight dirty, and gouging of eyes was almost their ultimate goal in any mortal dispute. They had an unattractive habit of inflicting what they called the "fishhook", involving thrusting fingers down an enemy's throat and tearing out his tonsils. As might be imagined, the English Quakers in Philadelphia and the German Quakers in Germantown were instinctively hesitant to take the side of every such white man in every dispute with any redone. For their part, the Scotch-Irish frontiersmen were infuriated at what they believed was an unwillingness of the sappy English Quaker-dominated legislature to come to their defense. Meanwhile, the French pushed Eastward across Pennsylvania, almost coming to the edge of Lancaster County before being repulsed and ultimately defeated by the British.

In December 1763, once the French and Iroquois were safely out of range, a group of settlers from Paxtang Township in Dauphin County attacked the peaceable local Conestoga Indian tribe and totally exterminated them. Fourteen Indian survivors took refuge in the Lancaster jail, but the Paxtang Boys searched them out and killed them, too. Then, they marched to Philadelphia to demand greater protection -- for the settlers. Benjamin Franklin was one of the leaders who came to meet them and promised that he would persuade the legislature to give frontiersmen greater representation, and would pay a bounty on Indian scalps.

Very little is usually mentioned about Franklin's personal role in provoking some of this warfare, especially the massacre of Braddock's troops. The Rosenbach Museum today contains an interesting record of his activities at the Conference of Albany. Isaac Norris wrote a daily diary on the unprinted side of his copy of Poor Richard's Almanac while accompanying Franklin and John Penn to the Albany meeting. He records that Franklin persuaded the Iroquois to sell all of western Pennsylvania to the Penn proprietors for a pittance. The Delaware tribe, who really owned the land, were infuriated and went on the warpath on the side of the French at Fort Duquesne. There may thus have been some justice in 1789 when the Penns were obliged to sell 21 million acres to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for a penny an acre.

Subsequently, Franklin became active in raising troops and serving as a soldier. He argued that thirteen divided colonies could not easily maintain a coordinated defense against the unified French strategy, and called upon the colonial meeting in Albany to propose a united confederation. The Albany Convention agreed with Franklin, but not a single suspicious colony ratified the plan, and Franklin was disgusted with them. Out of all this, Franklin emerged strongly anti-French, strongly pro-British, and not a little skeptical of colonial self-rule. Too little has been written about the agonizing self-doubt he must have experienced when all of these viewpoints had to be reversed in 1775, during the nine months between his public humiliation at Whitehall, and his sailing off to meet the Continental Congress. Furthermore, as leader of a political party in the Pennsylvania Legislature, he also became vexed by the tendency of the German Pennsylvanians to vote in harmony with the Philadelphia Quakers, and against the interest of the Scotch-Irish who were eventually the principal supporters of the Revolutionary War. It must here be noticed that Franklin's main competitor in the printing and publishing business was the Sower family in Germantown. Franklin persuaded a number of leading English non-Quakers that the Germans were a coarse and brutish lot, ignorant and illiterate. If they could be sent to English-speaking schools, perhaps they could gradually be won over to a different form of politics.

Since the Germans of Germantown was supremely proud of their intellectual attainments, they were infuriated by Franklin's school proposal. Their response was almost a classic episode of Quaker passive-aggressive warfare. They organized the Union School, just off Market Square. It was eventually to become Germantown Academy. Its instruction and curriculum were so outstanding as to justify the claim that it was the finest school in America at the time. Later on, George Washington would send his adopted son (Parke Custis) to school there. In 1958 the Academy moved to Fort Washington, but needless to say, the offensive idea of forcing the local "ignorant" Germans to go to a proper English school was rapidly shelved. This whole episode and the concept of "steely meekness" which it reflects might be mirrored in the Japanese response, two centuries later, to our nuclear attack. Without the slightest indication of reproach, the Japanese wordlessly achieved the reconstruction of Hiroshima as now the most beautiful city in the modern world.

Germantown Before 1730

|

| Rev. Wilhelm Rittenhausen |

The flood of German immigrants into Philadelphia after 1730 soon made Germantown, into a German town, indeed. From 1683 to 1730, however, Germantown had been settled by Dutch and Swiss Mennonites, attracted by the many similarities between themselves and the Quakers of England. They spoke German dialects to preserve their separateness from the English-speaking majority but belonged to distinctive cultures which were in fact more than a little anti-German. This curiosity becomes easier to understand in the context of the mountainous Swiss burned at the stake by their Bavarian neighbors, Rhinelanders who sheltered them from various warring neighbors, and Dutchmen at the mouth of the Rhine, all adherents of Menno Simon the Dutch Anabaptist, but harboring many differences of viewpoint about the tribes which surrounded them.

Anabaptism is the doctrine that a child is too young to understand religion, and must be re-baptized later when his testimony will be more binding. In retrospect, it seems strange that such a view could provoke such antagonism. These earlier refugees were often townspeople of the artisan and business class, rapidly establishing Germantown as the intellectual capital of Germans throughout America. This eminence was promoted further through the establishment by the Rittenhouse family (Rittinghuysen, Rittenhausen) of the first paper mill in America. Rittenhousetown is a little collection of houses still readily seen on the north side of the Wissahickon Creek, with Wissahickon Avenue nestled behind it. The road which now runs along the Wissahickon is so narrow and windy, and the traffic goes at such dangerous pace, that many people who travel it daily have never paid adequate attention to the Rittenhousetown museum area. It's well worth a visit, although the entrance is hard to find (try going west on Wissahickon Avenue then turning around, a little beyond the entrance).

Even today, printing businesses usually locate near their source of paper to reduce transportation costs. North Carolina is the present pulp paper source, several decades ago it was Michigan. In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, paper came from Germantown, so the printing and publishing industry centered here, too. When Pastorius was describing the new German settlement to prospective immigrants, he said, "Es ist nur Wald" -- it's just a forest. A forest near a source of abundant water. Some of the surly remarks of Benjamin Franklin about German immigrants may have grown out of his competition with Christoper Sower (Saur), the largest printer in America, and located of course in Germantown.

Francis Daniel Pastorius was sort of a local European flack for William Penn. He assembled in the Rhineland town of Krefeld a group of Dutch Quaker investors called the Frankford Company. When the time came for the group to emigrate, however, Pastorius alone actually crossed the ocean; so he was obliged to return the 16,000 acres of Germantown, Roxborough and Chestnut Hill he had been ceded. Another group, half Dutch and half Swiss, came from Krisheim (Cresheim) to a 6000-acre land grant in the high ground between the Schuylkill and the Delaware. The time was 1683. The heavily Swiss origins of these original settlers give an additional flavor to the term "Pennsylvania Dutch".

Where the Wissahickon crosses Germantown Avenue, a group of Rosicrucian hermits created a settlement, one of considerable musical and literary attainment. The leader was John Kelpius, and upon his death the group broke up, many going further west to the cloister at Ephrata. From 1683 to 1730 Germantown was small wooden houses and muddy roads, but there was nevertheless to be found the center of Germanic intellectual and religious ferment. Several protestant denominations have their founding mother church on Germantown Avenue, Sower spread bibles and prayer books up and down the Appalachians, and even the hermits put a defining Germantown stamp on the sects which were to arrive after 1730. The hermits apparently invented the hex signs, which were carried westward by a later, more agrarian, German peasant immigration, passing through on the way to the deep topsoil of Lancaster County.

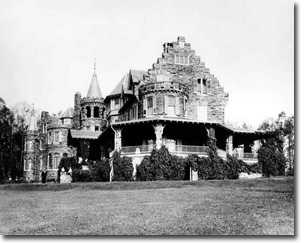

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

Kenneth Gordon, MD, Hero of Valley Forge

|

| Valley Forge |

There's no statue of Ken Gordon at Valley Forge National Park, although it would be appropriate. No building is named after him; it's probable he isn't even eligible to be buried there. But there would be no park to visit at Valley Forge without his strenuous exertions.

One day, Ken's seventh-grade daughter came home from school with the news that the father of one of her classmates said that Valley Forge Park was going to be turned into a high-rise development. That's known as hearsay, and lots of things you hear in seventh grade are best ignored. But this happened to be substantially true. At that time, the Park was owned by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and Governor Shapp was finding the upkeep on the Park was an expense he needed to reduce. The historic area had two components, the headquarters area, and the encampment area. One part would become high-rise development and the other would become a Veteran's Administration cemetery. Although any form of rezoning has the familiar sound of politics to it, Dr. Gordon (a child psychiatrist) had the impression that Sharp was mostly interested in reducing state expenses, and had no particular objection to some better use of the historic area. At any rate, when Gordon went to see him, he said that he would agree to a historic park if Gordon could raise the money somehow. The Federal Government seemed a likely place to start.

Well, the sympathetic civil servants at the National Park Service told him how it was going to be. You get the consent of the local Congressman (Dick Schulze) and it will happen. If you don't get his consent, it won't happen. It seemed a simple thing to visit that Congressman, persuade him of the value of the idea, and it would be all done; who could refuse? After the manner of politicians, Schulze never did refuse, but somehow never got around to agreeing, either. It takes a little time to learn the political game, but after a reasonable time, the National Park employees told Gordon he was licked. Too bad, give up.

He didn't give up, he went to see his Senators, at that time Scott and Clark. They instantly thought it was a splendid idea, and instead of going pleasantly limp, they sent Citizen Gordon over to see Senator Johnson of Louisiana, the chairman of a relevant committee. Johnson also thought it was a great idea, and called out, "Get me a bill writer!" A bill writer is usually a government lawyer, tasked with listening to some citizen's idea and translating it into that strange language of laws -- section 8(34), sub-chapter X is hereby changed to, et cetera. Bill writers have to be pretty good at it, or otherwise, they will misunderstand the intent of the original idea, modified by the personal spin of the committee chairman, the comments of the authorizing committee, and later bargains struck in the House-Senate conference committee. Having negotiated all those hurdles, a bill has to be written in such a prescribed manner that it won't be found to have multiple loopholes when it later reaches the courts in a dispute. A good deal of the time of our courts is taken up with making sense of some careless wording by bill writers. That's what is known as the "Intent of Congress", an ingredient that may or may not survive the whole process.

|

| Dick Schulze |

Ken Gordon had to go through this process, including testimony at hearings, for three separate congressional committees. To get everybody's attention, he organized several hundred supporters to write letters and get petitions signed by several thousand voters. These supporters, in turn, influenced the media and started a lot of what is known as buzz. All of this is an awful lot of work, but there is one thing about this case that can make us all proud. Not once did a politician suggest a campaign contribution was essential in this matter.

In time, ownership of the Park did in fact migrate from the Commonwealth to the U.S. Department of the Interior, hence to the National Parks Service. Everyone agrees it has been well managed, and increasing droves of visitors come here every year. It is now clearly a national treasure. Unfortunately, the encampment area got away and has been commercially developed, although not nearly as high-rise as originally contemplated. Along the way, many discouraging words were spoken about the futility of fighting against such odds. The outcome, however, is the embodiment of two slogans, the first by Ronald Reagan. "It's amazing what can be accomplished, if you don't care who gets the credit for it." The other slogan is older, and Quaker. All you need, to accomplish anything, is leadership. And leadership -- is one person.

One day Ken Gordon, the very busy doctor, was asked how much of his time was taken by this effort. His answer was, ten hours a week, every week for five years.

La Fayette, We Are Here

|

| Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette |

It will be recalled that La Fayette was 19 years old at Valley Forge, spoke no English, had no previous military experience. He nevertheless demanded, and got, a commission as Major General on the prudent condition that he have no troops under his command, at least for a while. Washington had been strongly reminded by various people that this young Frenchman was one of the richest men in France, a personal friend of the Queen, and thus critical to the project of enlisting French assistance in the war. Under the circumstances, it was shrewd to send him on the project of enlisting Indian allies among the Iroquois, since many tribes, particularly the Oneida, spoke French and held their former allies in the French and Indian War in great esteem. The chief of the Oneida Wolf clan (Honyere Tiwahenekarogwen) was visiting General Philip Schuyler in Albany at about the time LaFayette showed up on his mission to get some help for Valley Forge. General Horatio Gates was busy at the time rallying a colonist army to defend against the British under Burgoyne, coming down from Quebec, eventually to collide at the Battle of Saratoga.

Earlier in the war, Honyere's Oneida tribe had tangled with their fellow Iroquois under the leadership of Joseph Brandt (the Dartmouth graduate who was both biblical scholar and commander of several frontier massacres); the Oneida had many new scores to settle with the English-speaking Iroquois tribes. Honyere made the not unreasonable request that before his warriors went off to war, his new American allies would please build a fortification to protect his women and children from Brandt's Mohawks. LaFayette readily put up the money for this project, quickly becoming the Great French Father of the Oneidas. After some scouting and patrolling for Gates, Honyere and about fifty of his braves followed LaFayette to Valley Forge, where they soon made a nuisance of themselves to the Great White Father George Washington. Finally, word of the official French alliance with the colonists reached London, Howe was replaced by Clinton, and the British began to withdraw from their isolated position at Philadelphia.

It was thus that the jubilant rebels at Valley Forge learned that the fortunes of war had turned in their favor, and the French alliance was the source of it. With the British making preparation to abandon Philadelphia, it seemed a safe thing for Washington to give LaFayette command of two thousand troops, including the fifty Oneida Indians, and post them to Barren Hill (now LaFayette Hill), along Ridge Pike near Plymouth Meeting. Washington gave the strictest orders that they were to take no chances with anything, and particularly were to remain mobile, moving camp every day. This was not exactly what the richest man in France was anticipating, and wouldn't make a very saucy story to tell Marie Antoinette about. So, he promptly set about fortifying Barren Hill. Local Tory spies quickly spread this news to General Clinton, who promptly led eight thousand redcoats up the Ridge Pike to capture the bloody Frog. Clinton's plan was good; a detachment went around LaFayette in the woods and came back down Ridge Pike from the other direction, driving the Americans down the Pike into the open arms of the main body of British troops, coming up Ridge Pike. From this point onward, two entirely different stories have been told.

The more widely-held account has LaFayette climbing the steeple of the local church and noticing that there was an escape path, leading down the hill to the Schuylkill River at Matson's Ford. The Indian scouts were sent forward to hold off the British while the troops made their escape. Clinton sent a cavalry charge of Dragoons forward, yelling and waving their sabers, generally making a terrifying spectacle. The Indian scouts, as was their custom, were lying in the brush shoulder to shoulder, and at command by Honyere rose from the ground to let out a resounding chorus of war whoops. The Indians had never seen a cavalry charge, the Dragoons had never heard a war whoop, so both sides fled the battlefield without doing much damage. Meanwhile, LaFayette and his troops escaped to safety on the far side of the Schuylkill.

Other accounts of this episode relate that when Washington heard of it he remarked sourly that either they were pretty lucky, or else the enemy was pretty sluggish. In any event, a few soldiers were killed on both sides, the Americans crossing the River were described as "kegs bobbing on the pond", and it does seem the British army mostly just watched them do it. In the confusion, of course, everyone involved was fearful of being surrounded by unseen troops, and the British may well have worried the whole thing was a trap.

The saddest postscript to the Battle of Barren Hill is the fate of the Indians. After the war was over in 1783, the colonists busied themselves with taking over Indian land. Honyere pitifully petitioned the New York legislature for some consideration of his tribe's wartime service. They ignored him.

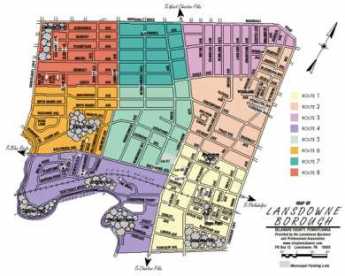

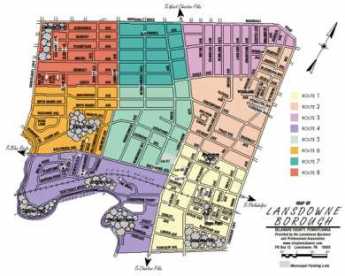

Lansdowne

|

| Lansdowne Map |

The Granville, or Lansdowne, the family had so many members important in English history, that the Lansdowne name adorns countless schools, boroughs, colleges, museums and other monuments around the former British empire. It would require undue effort to sort out just why each memorial is named after just which member of the family. In the Philadelphia region, Lansdowne is the name of a small borough in Delaware County,

|

| Lansdale |

often annoyingly confused with Lansdale, a small borough in Montgomery County. However, it really seems more appropriate to focus reverence on the Lansdowne mansion, which from 1773 to 1795 was the home in now Fairmount Park of the last colonial Governor. That would have been John Penn, who was one of several Penns who still shared the Proprietorship until 1789, and who shared in the miserly payment which the Legislature of the new Commonwealth made as compensation for expropriating twenty-five million acres of their property. The French Revolution was going on at that time, so there were probably some patriots who would scoff that John Penn was lucky not to be guillotined.

The Penn family could see the Revolution coming, and like everyone else was uncertain who would win. Real decision-making for the Proprietorship rested with Thomas Penn in London, a close friend of the King and his ministers. The strategy employed in this difficult situation was to surrender the right to govern the colony conferred by its original charter and to become mere real estate owners with John their local representative pledging local allegiance. That might have worked for a while, until General Howe's troops captured Philadelphia. Soldiers were dispatched to Lansdowne to tell John Penn he was under detention, to reduce his potential utility to the occupying army.

|

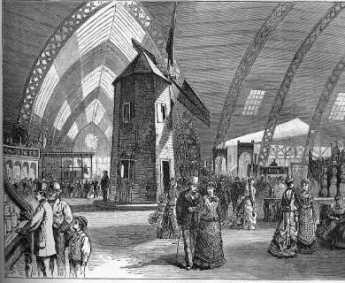

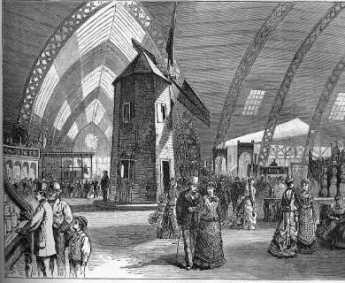

| Horticultural Hall |

As matters eventually worked out, some of the Penn descendants remained fairly wealthy after the Revolution, especially those whose wives had inherited substantial assets from other sources. But some were severely impoverished. The stately Georgian mansion burned down in 1854, and the site was then occupied by the Horticultural Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Perhaps because of misplaced patriotic fervor, it is now difficult to find a picture of Lansdowne.

The elegance of the place, on 140 acres, is suggested by the fact that William Bingham the richest man in America at the time, apparently acquired it from James Greenleaf the partner of Robert Morris, and the nephew by marriage of John Penn, who acquired it from Penn's estate but probably had to give it up in the financial disasters of Morris and his firm. Lansdowne was still a grand manner when it was briefly acquired by Joseph Bonaparte, the former King of Spain. In view of the fact that Bingham had provided President Jefferson with the gold to finance the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte, and earlier had practically forced the Congress to call off an impending war with France, there was likely a connection here.

And to some extent, the ill-treatment which John Penn received from the Pennsylvania legislature (roughly fifteen cents an acre) in the Divestment Act of 1779 can possibly be traced to the unrelenting hatred by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania's icon. History does not tell us what made these two former friends fall out in 1754, sufficient to make Franklin willing to spend years in London trying to get the colony away from the Penns. The feeling was surely mutual. When John Penn was offered the patronship of the American Philosophical Society, he declined, just because Franklin was its president. In retrospect, that sounds unwise.

Potts

Rebecca Potts used to say there were three towns in Pennsylvania named after her family -- Pottstown, Pottsville,

|

| Pottsville biennial |

and Chambersburg. Becky never designed to explain whether Chambersburg was just a joke or whether her very extensive family really had connections in Chambersburg. It's possible either way; there were certainly Potts inValley Forge where Washington's Headquarters, which everyone visits, had been home to Isaac Potts, the third generation of Dutchmen named Potts to live there. Isaac ran a grist mill, the others mostly were ironmasters. The family seat in Pottstown was named Pottsgrove, still open for visitors. Holland Dutch they may have been, but Pottsgrove architecture is definitely of the Welsh style.

|

| Pottsville Coal |

Pottsville, much further up in the anthracite region, became notable through the novels of John O'Hara, a native son. For a whole generation, just about everybody in Pottsville was uneasy that O'Hara would confirm just who certain characters in his moderately raunchy novels represented in real life. Pottsville's main business for a century was extracting coal for the Girard Estate, which had its coal-mining headquarters in the town, based on Stephen Girard's shrewd purchase of nearly all of Schuylkill County.

The broad sweeping view from the interstate highway going north from Valley Forge makes it easy to see how Pottstown was created by the upheaval of a mountain ridge, which split open to let the Schuylkill River wind through. Pottstown is a water gap. The huge cooling towers of The Limerick nuclear power plant dominate one side of the river cliff and can be seen for miles. The cliff on the other side of the river, behind which hides the town of Pottstown, used to shelter the Wright aircraft factory, much of which was underground. That gave it a railroad (The Reading RR) and ready access to the river, plus privacy from the land side. Down to the right a mile is the Pottstown Hospital, on the edge of town, quite near the campus of the famous Hill School, fierce competitors of the Lawrenceville School in sports. Just about everything in this area is on top of some kind of hill.

Just back of the hospital, seemingly on the grounds of it, rises a peculiar steel tower, which the local workmen report is a sending station for cellular telephones. However, one of the doctors of the hospital relates a somewhat different history. He says he was once called on a medical emergency, told to ring the elevator at the little house beside the steel antenna, and travel down, down, into secret depths. He found himself in the headquarters of the Northeastern Air Defense Command, which was certainly hidden in an ideal place if the story has any truth to it. Unfortunately, that story-teller was a famous cocktail-party raconteur whose wild tales were never to be taken completely seriously. For many years, the hospital on a cliff was surrounded by corn fields, and it is certainly true you could look out the windows at a sea of corn, never suspecting you were very close to a railroad and a river, quite possibly right over an underground aircraft factory. Someday it may be possible to find out the truth of these tales of the Dutch country.

During the American Revolution, the British blockaded the coast and landed troops on the main coastal highways. The Americans responded in a quite natural way by building an inland north-south forest trail, sort of on the order of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Pottstown was one natural stop on this trail, which tended to intersect with many roads coming up along the banks of the coastal rivers. In one very famous episode, wagon loads of Philadelphia Quakers were arrested and taken up the Schuylkill to Pottstown, then south to internment at Winchester, Virginia. They weren't exactly Tories, but they certainly were not sympathetic to revolutions. One of the most famous of these semi-prisoners was Israel Pemberton, one of the leaders of the Quaker colony. He later reported he was treated well, but onlookers in Pottstown described him as being thoroughly abused.

Pottstown had a century of prosperity during the industrial age, then declined and decayed. In recent years. The interstate highway has brought a migration of exurbanites whose taste in architecture tends toward McMansions. Let's hope they can acquire a dose of local history, starting a new historical revival of a town with great potential, considerable past glory, and a wonderful natural setting.

Radioactive River Bend

|

| Gold Cert |

A mile or two south of Pottstown, the Schuylkill River encounters a rocky ridge several hundred feet high and makes a bend around it. The first Treasurer of the United States, Michael Hillegas, built a colonial mansion on the point of the bend, and it has been lovingly restored and preserved by a noted Philadelphia surgeon and his wife. Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury under the Constitution, has his picture on the modern version of a ten-dollar bill. So it is appropriate that Hillegas, the first Treasurer under the Articles of Confederation, had his picture on many versions of a ten-dollar gold note, back in the days when the American dollar was as good as gold. River Bend Farm is not only colonial, charming and maintained in mint condition, but it is also tucked away between the bend in the river and the high ridge to one side, giving it seclusion and privacy.

A high ridge near a river is unfortunately also an ideal place to build a nuclear power plant, and that's where the Limerick plant now looms up, glowing at night, occasionally making faint humming noises. There's a limited-access highway from Philadelphia to Reading which swoops up the valley, and the two high cooling towers of Limerick dominate the landscape for twenty miles. Because of the river bend, you aim straight for those towers for a long time before you swerve off, and the view is much like that from the bomber cockpit of the final scene in the movie "Dr. Strangelove". It gets your attention harmlessly, but it's hard to ignore. In spite of all sorts of official reassurance, everybody knows about Three-Mile Island, and Chernobyl, but few people emphasize there has never been a single injury from an American nuclear plant.