Related Topics

Historical Preservation

The 20% federal tax credit for historic preservation is said to have been the special pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. Much of the recent transformation of Philadelphia's downtown is attributed to this incentive.

Volunteerism

The characteristic American behavior called volunteerism got its start with Benjamin Franklin's Junto, and has been a source of comment by foreign visitors ever since. It's still a very active force.

Touring Philadelphia's Western Regions

Philadelpia County had two hundred farms in 1950, but is now thickly settled in all directions. Western regions along the Schuylkill are still spread out somewhat; with many historic estates.

The Main Line

Like all cities, Philadelphia is filling in and choking up with subdivisions and development, in all directions from the center. The last place to fill up is the Welsh Barony, a tip of which can be said to extend all the way in town to the Art Museum.

Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust

|

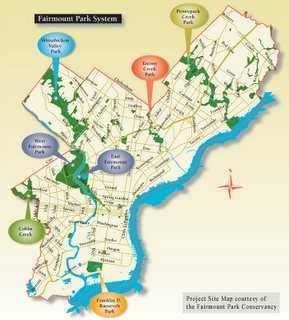

| Philadelphia's Fairmount Park |

New York's Central Park was created when it became clear there would be no park unless it was deliberately planned and its boundaries vigorously defended against real estate developers. Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, on the other hand, was to some degree a slum clearance project. The swift waters of the Wissahickon provide excellent power sources, provoking the construction of many mills. With steam power, they were abandoned, leaving desolate industrial hulks that blotted the landscape. Fairmount Park cleared out the remains of deserted mills, which had moved upriver to Manayunk, closer to a supply of coal. Fairmount Park was a creation of the Pennsylvania State Legislature, but the State never funded it. And it has thus always been somewhat larger than the City could afford.

In the early 1990s a beleaguered City government reached a public/private accord as a result of a commissioned study of the matter, which essentially urged that the city government should run the recreational programs in the parking area, and the private sector should be asked to do its best with land and historic building preservation. The William Penn Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and other philanthropic organizations banded together to form the Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust. Among its functions was to coordinate the many organizations which had been formed to preserve small areas of the park, as a result of the concerns of neighborhoods or descendants of former owners of historic homes. The Fairmount Park Trust finds itself in charge of over 400 houses, of which about 250 are genuine of historic value. They have to be preserved against vandalism and vagrants, mainly they have to be preserved against decay. Someone has to use them, and for that, someone has to spend money to fix them up and maintain them. If that is to happen, someone else has to set standards for preservation that balance the historic values with the need for some kind of present usage. Since few people would be willing to spend money and put up with uneconomical regulations if the building belongs to the park, the management of the Trust must manage and oversee very long-term leases. Obviously, the Trust must know what it is doing, have the wisdom to be innovative, and endure a fair amount of harangue by disappointed developers.

And it must supply some things which are hard to find, like advice and know-how about fixing up historic buildings of a certain age and history. The Trust has actually gone into the business of doing historic preservation for a fee, on its own property and elsewhere (Christ Church burial ground is an example). It thus generates some income to supplement philanthropic contributions. There is no requirement that prospective tenants must be non profit, only that the entity be of value to the neighborhood, and there are other signs that the Trust intends to be far-sighted and imaginative in the goal of making the Park something to be proud of, from the nearest to the farthest corner.

One idea suggested for further coordinated action might be to search for types of underbrush which would be repellent to deer who destroy the forest understory. Or, to search for particularly tasty "bait" shrubs which would draw the deer away from areas needing preservation. The combination of both ideas might lead to a natural balance, which would be unlikely to come about by the action of small local preservationists. Meanwhile, there are too many deer, and someone has to decide how and when to "cull the herd". That's how, in a small way, the trust got into the venison business.

So far, the Trust has preserved about 25 houses in the past ten years. That's a marvelous achievement, but it will take a century to complete the whole park unless momentum picks up. The Trust sort of needs an impresario of some kind or other to stir up public support.

Originally published: Monday, June 26, 2006; most-recently modified: Thursday, May 16, 2019