6 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Hippies and Vietnam

An agricultural past became industrial, but then the industrial boom started to fade. Blacks, young people and immigrants were set adrift.

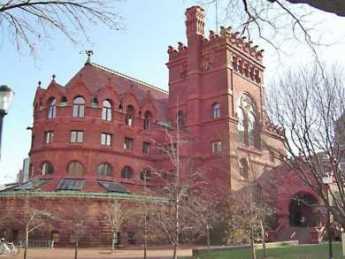

Historical Preservation

The 20% federal tax credit for historic preservation is said to have been the special pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. Much of the recent transformation of Philadelphia's downtown is attributed to this incentive.

A federal tax deduction is familiar enough; a federal tax credit is something else, it's tax-exempt federal money directly into your pocket. If you don't have any income, you can still get a federal check for a tax credit if it's a refundable tax credit. Some students of taxation are a little uncomfortable about refundable tax credits, because of the history that a great many people have become very wealthy from tax credits, building low-income housing projects. However, all federal subsidies merely seem good or bad, depending on your opinion of the social worth of what is subsidized.

In 1976 President Gerald Ford signed a tax provision which was the enthusiastic pet of Senator Lugar of Indiana. It created a federal subsidy for the rehabilitation of historic buildings, taking the form of a 20% refundable tax credit for project costs. To condense the rules to their essence, any building which is on the National Register of Historic Places is eligible for this tax credit, providing the project costs exceed the value of the building, and meet the approval of the National Park Service.

The Park Service probably secretly relishes its new power, but likely is uncomfortable with becoming a target of denunciation by real estate developers whose plans get rejected, with criticism of their taste by academics, and resentment by urban planners about the way these projects change the city. But it would only be a fair assessment that what has happened has stimulated a great deal of economic activity, has pleased most of the voters, and has given an air of thriving revival to a run-down urban center. It has also enriched some developers, and turned a commercial city center into a residential district.

Philadelphia has been a leader in urban rehabilitation, and it must have had some clever leadership to grasp the opportunity so early. But it also had a great many commercial buildings which had been built like fortresses around 1900, when the leadership of the Pennsylvania Railroad made the engineering of heavy duty structures almost a local religion. The essence of urban renewal is that the building has outlasted its original occupant. John Pitcairn was the shrewd investor who noticed that almost all corporations dissolved before they are 75 years old. Philadelphia's commercial structures were built to last a lot longer than that. Our problem is that we have more surviving structures than we have new commercial occupants to fill them. As long as that is true, urban residential conversions -- condos, as they say -- will be the future of Center City. With perhaps a small statue in some park, of Senator Lugar.

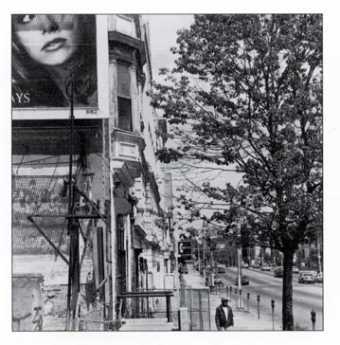

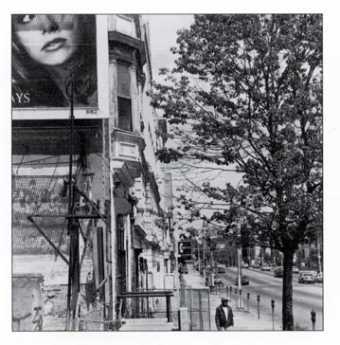

Highway Beautification

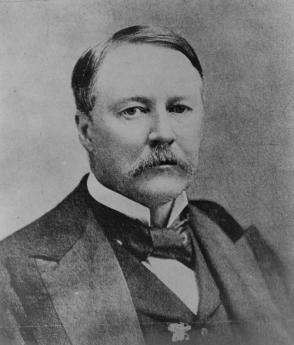

|

| Prince Grigory Potemkin |

Someone who has traveled in modern China -- and is at all observant -- knows that the extensive slums and trashy wastelands of the Inner Kingdom are systematically hidden from tourist's eyes by fences and plantings of tall trees. In a few years, the trees will grow a few feet taller and fully conceal what is behind them, but today modern tourist buses are high enough so you can see over the treetops if you look. When American tourists notice this, they are very smug.

The term Potemkin Village is a somewhat exaggerated term for the process Grigory Potemkin used to clean up the villages that his girlfriend Catherine the Great passed through on her visit to southern Russia and Crimea. He apparently did not construct whole fake villages as enemies claimed, but he was unnecessarily forceful,

|

| West Philadelphia, at one time. |

let us say, in his efforts to smarten things up. After taking a few rides on Philadelphia's suburban commuter trains, or a boat ride up to its rivers, the idea does cross most minds that we could use a Potemkin in charge of our Streets Department, or maybe a Communist Chinese on loan. We have miles, maybe even hundreds of miles, of overgrown weeds along our embankments, spiced with the discarded trash of historic duration. Since nobody wanted to live next to coal-burning locomotives, and most people even dislike the noisy though cleaner replacements, the houses along the railroad clearly deserve to be hidden. That's true in almost every town in the world (not Japan, not Switzerland) and it's deplorably true in our Philadelphia. Seaports and riverbanks are a mess everywhere, too, and we are certainly in style in that department as well. Why can't the Schuylkill look like the Seine, next to the cathedral of Notre Dame?

So the Chinese have combined the concept of cleaning up their public spaces, which we applaud, with the concept of hiding the economic truth, which we sneer at. Maybe we should give some thought to a spin campaign, the essence of which is a metropolitan crusade to pick up the trash, build some strategic fences, and plant a whole lot of tall evergreens along with the public ways. We've made a good start with Boathouse Row; why not extend it to Gray's Ferry, or even to Norristown? The idea is not a new one; Lady Bird Johnson made it her main goal in public life.

In 1965, Lyndon Johnson used his famous powers of legislative persuasion to give his wife what she wanted. The Highway Beautification Law of 1965 was passed by Congress on Lady Bird's birthday, with everyone in the gallery dressed in evening clothes. With the vote counted and enormous standing applause registered for fifteen minutes, the whole group traveled over to the White House for a signing of the law with nineteen pens. There followed the birthday party at the White House, to end all birthday parties. Highway billboards were a thing of the past.

That was forty or so years ago, and unfortunately, the billboard companies didn't like it at all. Through administrations both Democrat and Republican, the Department of Transportation has never issued regulations, so Highway Beautification was never implemented. It represents just one more unwritten aspect of the Constitution that James Madison and his friends didn't fully anticipate.

Harriton House

|

| Harriton House |

Three hundred years ago, in 1704, Roland Ellis acquired 700 acres of the Welsh Barony in what is commonly called Philadelphia Main Line and built a palatial house on it. He called his homestead Bryn Mawr, or great hill, after his ancestral home in Wales of the same name, thereby explaining why Bryn Mawr College and Bryn Mawr town have the name but are not notably situated on hills. The town of Bryn Mawr was once called Humphryville. But Bryn Mawr sounded nicer, even though there are plenty of Humphries still around to defend the older designation.

About fifty thousand acres were set aside by William Penn as the Welsh Barony, and there was the willingness to allow it to be self-governing, although that didn't much happens because the inhabitants saw no point in being self-governing. Nevertheless, the term isn't just an ethnic allusion, but has some historic meaning.

In any event, Ellis proved to be an unsuccessful manager of his estate, which rather soon passed into the hands of the Harrison family, who lived on it for about two hundred years until real estate development, and the taxes related thereunto, forced the creation of a complicated arrangement, with the township of Lower Merion owning the property and a non-profit group called the Harriton Association managing it. They have luckily obtained the services of a famous curator, Bruce Gill, who does research, writes papers, and organizes programs for visitors. The neighbors in the area, all living on land that formerly belonged to the Harrisons, are said to constitute the richest neighborhood in America. By building the original farmhouse rather far from the main road (Old Gulph) and remaining surrounded by neighbors who want to have privacy, Harriton House has fewer visitors than it deserves because it is so devilish hard to find.

There was a little local skirmishing during the Revolutionary War, but the main historical significance of the House was that Charles Thomson married a Harrison and lived there all throughout the period of the Revolution and the Articles of Confederation (1774-1789) as the Secretary of the Continental Congress. His little writing desk is, therefore, the most notable piece of furniture at Harriton House since every piece of official paper involved in the whole Revolutionary episode passed through it or over it. Modern organizations would do well to notice that Thomson was not given a vote and was expected to be totally unbiased about Congressional affairs. Even in those days, there must have been cautionary experience with secretaries who tinkered with the minutes for their own preferences. It certainly was entirely fitting that this last steward of the Articles of Confederation was designated to carry the news to George Washington at Mount Vernon, that he had been elected President of the new form of government. No doubt, Washington was pleased but unsurprised to learn of it.

While Harriton House is imposing on the exterior, and was the likely prototype of many characteristic Main Line stone mansions, the inside of the house is quite primitive. In those days it was cheap to build a big house but expensive to heat it. In 1704 surrounded by a continent of a forest, firewood may not have seemed a problem, but it quickly posed a transportation problem, and later houses tended to shrink in size. In any event, the interior of the house seems strangely bleak and bare, quite in keeping with the early Quaker principle of building a structure "without paint, or other adornments". Bruce Gill spent quite a lot of time and effort to determine that the random-width flooring had never received any shellac, varnish or wax. Those are beautiful floors, but the "finish" is just three hundred years of oxidized dirt.

The original Bryn Mawr, now called Harriton House, is well worth a visit. If you can find it; GPS is the modern solution.

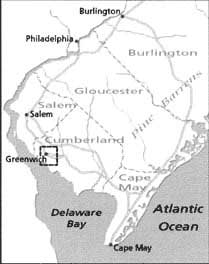

Greenwich, Where?

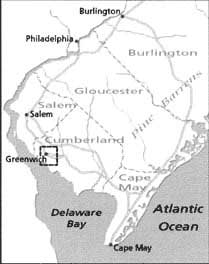

|

| Greenwich NJ |

If you sail north up the Delaware Bay, you would go past Rehoboth, Lewes, Dover, New Castle, Wilmington -- on the left, or Delaware side. On the right, or New Jersey side, it's a long way from Cape May to Salem, the first town of any consequence. That is, the Jersey side of the riverbank is still comparatively uninhabited. When the first settlers came along, with vast areas to choose among, it might have seemed attractive to settle on the Delaware side, because the peninsular nature of what is now called Delmarva (Del-Mar-Va) would provide land access to two large navigable bays, the Delaware, and the Chesapeake. To go all the way up the Delaware to what is now Pennsylvania would give trading access to a whole continent, so that eventually proved to be where immigration was headed. But as a matter of fact, the marshy Jersey shore seemed more attractive for settlement by the earlier settlers.

A settler has to think about starving the first year or two, because trees have to be cut down, and stumps pulled up before the land can even be plowed. After that, comes planting and growing, then finally harvesting. Trees, behind which Indians can hide, are a bad thing all around in the eyes of a settler. The flat swampy meadows of the Jersey bank were just exactly what the Dutch knew how to manage. Dam up the creeks and drain the ground, and you will soon have lots of lands ready for the plow, without any confounded trees. By the end of the seventeenth century, the English who had made the mistake of settling in rocky Connecticut finally saw what the Dutch were able to do, and came down to take it away from them.

|

| Greenwich scenery |

That's why there is a Salem, New Jersey, and also a Greenwich, New Jersey. Greenwich ( around here they pronounce it green-witch) had 870 residents at the last census. It is one of the cutest little colonial villages you are likely to encounter. The local historians refer to it as an unreconstructed Williamsburg, drawing prideful attention to the fact that these houses were really built in the colonial period, and are in no way imitation reconstructions. The isolated charm of this place is in large part due to being surrounded by a maze of wandering creeks, so visitors by land travel don't get there in time for lunch unless they take great care to follow a local road map. If you arrive by water, it's no problem; just navigate up the crooked and twisting Cohansey River.

Although pioneer settlement was much earlier, the oldest house still standing in that rather damp area was built in 1730. Things are pretty much the way they were before the American Revolution because the Calvinists who settled here were not prepared for the Jersey mosquito, which obviously is abundant in such a marshy area. With the mosquito comes relapsing (Vivax, malaria, black water (Falciparum) malaria, and Dengue Fever (graphically known locally as break-bone fever). As a matter of fact, encephalitis is also mosquito-borne. When you don't understand the insect carrier situation, survival in such an environment depends on local fables and lore, like going to the mountains for the summer after the planting season, and only returning at harvest time. That sounds to a New Englander newcomer like a superstitious cloak for lazy living, especially since masses of fish come up the river in teeming waves, looking for mosquitoes to eat. So, Greenwich is charming, but it never was thriving.

Working hard to find something to say about the town, it would appear that Paul Revere himself came riding into Greenwich in December 1774, urging the town to join their Boston relatives in the destruction of tea belonging to the British East India Company. Greenwich accordingly had a public tea burning on December 22. Since the more notorious Boston tea party took place on December 16, 1773, and the British Tea Act was passed in May, 1773, it is not exactly accurate to say the rebellion spread like wildfire. One has to suppose that the inflammatory tale told to the local farmers by Paul Revere was likely a little enhanced, since a careful recounting of the events in Boston suggests a number of ways the uproar might have been avoided if Samuel Adams and his friends had been less provocative. Or if Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been less flighty. Or for that matter, if Benjamin Franklin had restrained himself when he got hold of Hutchinson's letters at a critical moment when he was in London. In retrospect, the best model for behavior was provided by the Royal Navy; the whole Boston Tea Party was surrounded by armed British naval vessels, who did not lift a finger throughout the demonstration.

Anyway, little Greenwich had its minute of fame with a tea burning. Otherwise, it has had a very quiet existence for three centuries.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

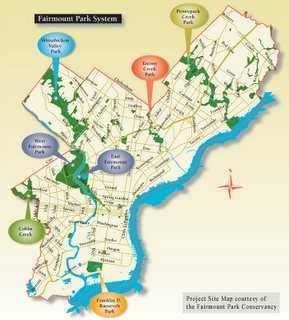

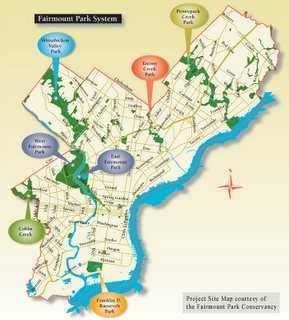

Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust

|

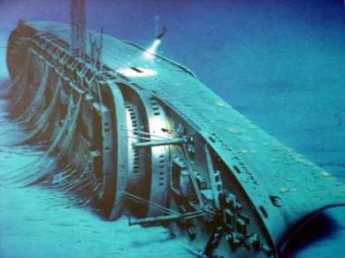

| Philadelphia's Fairmount Park |

New York's Central Park was created when it became clear there would be no park unless it was deliberately planned and its boundaries vigorously defended against real estate developers. Philadelphia's Fairmount Park, on the other hand, was to some degree a slum clearance project. The swift waters of the Wissahickon provide excellent power sources, provoking the construction of many mills. With steam power, they were abandoned, leaving desolate industrial hulks that blotted the landscape. Fairmount Park cleared out the remains of deserted mills, which had moved upriver to Manayunk, closer to a supply of coal. Fairmount Park was a creation of the Pennsylvania State Legislature, but the State never funded it. And it has thus always been somewhat larger than the City could afford.

In the early 1990s a beleaguered City government reached a public/private accord as a result of a commissioned study of the matter, which essentially urged that the city government should run the recreational programs in the parking area, and the private sector should be asked to do its best with land and historic building preservation. The William Penn Foundation, the Pew Charitable Trusts, and other philanthropic organizations banded together to form the Fairmount Park Historic Preservation Trust. Among its functions was to coordinate the many organizations which had been formed to preserve small areas of the park, as a result of the concerns of neighborhoods or descendants of former owners of historic homes. The Fairmount Park Trust finds itself in charge of over 400 houses, of which about 250 are genuine of historic value. They have to be preserved against vandalism and vagrants, mainly they have to be preserved against decay. Someone has to use them, and for that, someone has to spend money to fix them up and maintain them. If that is to happen, someone else has to set standards for preservation that balance the historic values with the need for some kind of present usage. Since few people would be willing to spend money and put up with uneconomical regulations if the building belongs to the park, the management of the Trust must manage and oversee very long-term leases. Obviously, the Trust must know what it is doing, have the wisdom to be innovative, and endure a fair amount of harangue by disappointed developers.

And it must supply some things which are hard to find, like advice and know-how about fixing up historic buildings of a certain age and history. The Trust has actually gone into the business of doing historic preservation for a fee, on its own property and elsewhere (Christ Church burial ground is an example). It thus generates some income to supplement philanthropic contributions. There is no requirement that prospective tenants must be non profit, only that the entity be of value to the neighborhood, and there are other signs that the Trust intends to be far-sighted and imaginative in the goal of making the Park something to be proud of, from the nearest to the farthest corner.

One idea suggested for further coordinated action might be to search for types of underbrush which would be repellent to deer who destroy the forest understory. Or, to search for particularly tasty "bait" shrubs which would draw the deer away from areas needing preservation. The combination of both ideas might lead to a natural balance, which would be unlikely to come about by the action of small local preservationists. Meanwhile, there are too many deer, and someone has to decide how and when to "cull the herd". That's how, in a small way, the trust got into the venison business.

So far, the Trust has preserved about 25 houses in the past ten years. That's a marvelous achievement, but it will take a century to complete the whole park unless momentum picks up. The Trust sort of needs an impresario of some kind or other to stir up public support.

Doylestown

|

| James Michener |

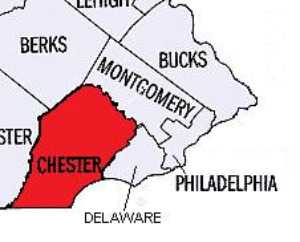

Caught between the expansion of two metropolitan areas, Bucks County is inevitably doomed to extinction as a culture. Chester County and Bucks are in similar situations, as the suburbia devours exurbia, in this case, the Quaker farm communities. So you better go have a look, while they still survive to some degree.

The political unit of the area has been the county, and the county seat is in Doylestown, population about 8000. Within a few decades, it seems safe to predict the county population will approach a million. The town has lots of pride in itself and is just as cute as any town could possibly be. New Castle, Delaware has been preserved with the same pride but is uniform of a single period of architecture; Doylestown is a carefully preserved jumble of styles and periods, sizes and shapes. Like Princeton, NJ, and Odessa, DE, it is so attractive it brings hordes of visitors, which in turn quickly strangle it with traffic and lack of available parking space. There is an attempt to rescue the town with a by-pass highway, and blessings on the attempt. But the problem for these exurban jewels is not that people want to go around them, the problem is they are the main destination.

|

| Mercer Museum |

Doylestown was created in 1745 when William Doyle built a tavern at the crossroads. The county seat brings the courthouse with eleven judges and who knows how many lawyers, and the hospital. Henry Chapman Mercer brought three astonishing buildings, his 44-room mansion on 70 acres in the center of town, his famous Mercer tile factory in his back yard, and his multi-story museum of tools and crafts. All three of Mercer's buildings are made of concrete, built by craftsmen and himself with essentially unlimited personal funds derived from fabric manufacture in New England. And then this last bastion of the crafts movement embraced the artist colony established by Redfield at New Hope, and both of them attracted all those rich Broadway stars and publishing moguls. Right in the center of town, the Mercer crafts museum sits across the street from the James A. Michener Art Museum, small but very tasteful, the museum home of the Pennsylvania Impressionist school of art. The essence of this style is a smooth careful background, overlaid with quick thick foreground brushwork, producing a strong three-dimensional effect.

Schoolchildren in buses delight in the dolls house aspects, tourists admire the very fine art, everybody likes the cute little jumble of well-preserved eclectic buildings. It's all in a setting of Quaker farmhouses for the time being, but the split-levels and the McMansions by the thousands are coming. Visitors throng to see, and the residents are proud of what they have. But, really, does everybody have to bring his car?

Christ Church and Elfreths Alley

|

| Elthreths Alley |

The north side of Dock Creek (now, Dock Street) was lower than Society Hillside and somewhat swampy. The tendency to flood caused the north side to have smaller and less permanent buildings, and so it became the Colonial waterfront area remaining more commercial, and in parts, shabby, even during the 19th Century. Still further to the north, this was not the case, but the waterfront and food market patch more or less marooned Christ Church, now the single most graceful and elegant Colonial building still standing. This formerly commercial area is now called Old City, with many loft apartments mixed among surviving warehouse outlets, and of course the ethnic restaurants characteristic of such gentrified areas.

|

| Christ Church |

Elfreth's Alley, running for one block east and west between Second and Front (1st) Streets. Some of the histories of this street is obscure, so some of it is probably synthetic because nothing particularly historic happened there to create detailed records. Elfreth's Alley claims to be the oldest street in America, a claim that can be substantiated back to 1702. The street is filled with little "workers houses", presenting a solid front of buildings on both sides of the cobblestoned street. Most of the houses could vaguely be called "father, son and holy ghost houses", looking as though they consisted of three rooms on top of each other, although in fact most of them are larger. A moment's consideration shows that the street consists of many double houses, with three doorways in front. Each house had a door to the interior, and most of them have a third door opening to a shared tunnel between the two houses, leading to the back yards. These tunnels were called "easements", a term that has migrated from its earlier usage. Although William Penn envisioned large single estates in his "Greene Country Towne", he sold considerable land to people who remained in England as absentee landlords, who soon found that many small houses produced more rent than one or two big ones. One of the houses on Elfreth's Alley acts as a museum, with tours; there is an active civic association, and once a year in June there is a street fair.

Because the land was swampy and the neighborhood congested, Christ Church soon outgrew its backyard burial ground, and burying important people under slabs in the walkways and corridors. Visitors who do not come from that sort of religious background are typically uncomfortable walking over such graves, a quite common arrangement in European cathedrals. But eventually, it was necessary to go several blocks westward to create a "new" burial ground. Most of the famous names from the Revolutionary era, like Benjamin Franklin and four other signers of the Declaration of Independence are found on the tombstones at Fifth and Arch, just across the street from the Free Quaker meeting house, and opposite the Philadelphia Mint. On the remaining corner of Fifth and Arch is the Constitution Center which will open July 4, 2003. It can already be seen that its architecture clashes with the rest of the historic area, but it is fervently hoped that its programs will redeem it.

REFERENCES

| Society Hill and Old City, Image of America: Robert Morris Skaler | Amazon |

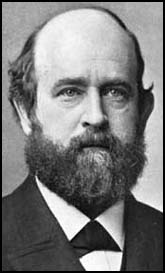

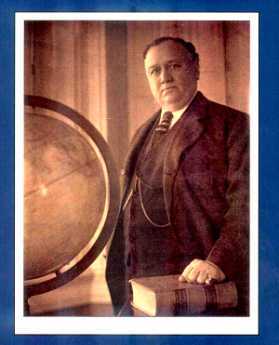

Henry George, Single Tax

|

| Henry George |

Philadelphia was the birthplace of Henry George at 413 South 10th Street between Pine and Lombard, in 1839. The house has been restored to its 1839 condition and serves as the Philadelphia extension of the Henry George School for Social Studies, where you can take a course or two on the economic theories of Henry George, especially the Single Tax. If you do so, you can join the rest of us in pondering whether Henry George was a genius or a nut; he certainly combined some elements of both.

|

| Henry George House |

Leo Tolstoy no less, felt there was a conspiracy to keep people from knowing about the theories of Henry George, saying, "People do not argue with the teaching of George, they simply do not know it." In 1879 Henry George published a book, "Progress and Poverty which made him so famous he became a candidate for Mayor of New York City. Although he lost the election, he outpolled the third candidate, Theodore Roosevelt. The underlying thesis of his book would probably not find much approval among contemporary economists, who would likely say he was fooled by a cyclic increase in the value of land as an asset class. What he said was there was a remorseless trend of land to increase in value, while the proportion of wealth represented by labor and capital steadily diminished. Nevertheless, it can still be argued that: proceeding from the wrong premise about the causes of poverty, he might have propounded an attractive cure -- the single tax. Henry George asserted that we should stop taxing buildings ("improvements") and place all municipal taxes on land.

There could be something to this. It is uncomfortably true that your taxes go up whenever you build a new building or substantially renovate an old one. The increased taxation of improvements is a disincentive to the building, renovating and improving a property. Placing taxes on the underlying land, by contrast, would create a positive incentive to build something and put the land to use. Evidence can in fact be produced that partial adoption of this principle has caused considerable prosperity in Pittsburgh, notwithstanding that city's recent flirtation with bankruptcy for unrelated reasons. Pittsburgh has shifted the proportion of real estate taxes from structures to underlying land, several times, and each time the change was followed by a demonstrable flurry of real estate development. Philadelphia had no similar flurries at those times, and it is said the contrast was caused by State Law which forbids such "discriminatory" taxation in first-class cities. Pennsylvania has only only one first-class city, Philadelphia, so you don't have to guess which city the Legislature had in mind.

Before we let ourselves get too embittered by dirty politics, we should take a look at Arden, Delaware, which is another nearby town to try the Henry George approach. Arden is a little country suburb of Wilmington which became a summer art colony, with theater groups, especially favoring Shakespeare. Arden, which is Shakespeare-speak (in As You Like It) for the Ardennes Forest in France, applied the Henry George rules to taxing the land not the summer houses of the area. So, go take a look there at the result. More and more houses crowded closer and closer together -- on the same land. There's plenty of open land over the next hill where Arden supporters could drive or even walk in ten minutes, so the Henry George system is quite effective all right. But the effect is not entirely what was intended. Leo Tolstoy is gone, so someone else must unravel this riddle.

Charles Peterson and Amity Buttons

|

| Charles Peterson |

Charles Peterson, the famous architectural historian and preservationist, died just before his 98th birthday on August 19, 2004. It is to him we largely owe the redevelopment of Society Hill, and the design of the Independence National Park, as well as a host of restorations from the Adams Mansion of Quincy, Massachusetts, to the early French settlements along the Mississippi. He conceived of many national historic preservation projects, the most notable of which is the Historic American Buildings Survey (HASB) of the Department of the Interior.

|

| The Adams Mansion |

While he was most notable for large visions and huge projects, he also had a keen appreciation for fastidious accuracy in small matters, of which the Amity Button would be a vivid example. In the surviving Colonial buildings of Philadelphia, it is common to find a plain ivory coat button nailed to the top of the newel post of the main staircase. There's one in Independence Hall, another in the grand staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and there is one in Charlie Peterson's own home, the one where he was the first Society Hill gentrification pioneer, a house originally built by Stephen Girard around 3rd and Spruce.

|

|

The Free Quaker Meeting House |

There is a strong tradition in Philadelphia that these strange buttons are Amity Buttons, nailed there by the Quaker builder at the moment when the new owner had fully settled his construction debt, symbolizing the amity between a willing buyer and a willing seller. Countless visitors to Society Hill have been shown these curious buttons, and it always seems to produce a warm glow of appreciation for the discovery. If you have one of these in your own house, you can be very proud.

Unfortunately, Charlie Peterson couldn't find any evidence for the truth of this fable, and you can be sure he subjected the matter to a totally dedicated search. You might think there would be some notations in the deeds, or in the correspondence of the day, or in the literature of the times. You would think that someone who repeats this tale would be able to relate where he got it, and that would lead to some letters in an attic, and that if you work hard enough, you will find it. But when the button matter came up, Mr. Peterson would suddenly become grim-lipped and sad, and repeat the mantra that there is no evidence to support the story. He even awarded prizes to architectural students for essays on newel posts, banisters, and stair rails, but no student essay ever turned up any authentication of the Amity Button story. Absence of evidence is of course not the same as evidence of absence, so it is remotely possible that the story will someday be vindicated.

Indeed, you have to believe there was something or other to start the story. Victor Failmetzger and his wife, who have a notable reputation for authenticating old house parts, relate that in Colonial Virginia it was common to have hollow newel posts on the stairway, and occasionally to find the deed to the house secreted in one of them. So the search goes on.

In fact, it always seemed likely that Charles Peterson very much wanted to believe the fable was true. But until some evidence turned up, he was going to go to his grave with the declaration that there existed no evidence for it.

Slum Creation and Urban Sprawl

|

| North Philly |

Slum creation, while occasionally deliberate, is most typically caused by an area's abandonment by previous owners, at lower prices, to bargain hunters. When a large employer moves or closes, the employees seek work elsewhere and sell their houses for what they can get. When the influx of new ethnic groups threatens to weaken real estate prices, panic may be created that waiting too long to sell may find the property worthless; nobody wants to be the last one out the door. During the 20th Century, the driving force in Philadelphia was the flight to the suburbs by people who found a better value in suburban schools, shops, and neighborhoods. All of these processes create slums, almost invariably with a net loss of value in the community. Take a look at those deteriorating mansions on North Broad Street, where the Civil War millionaires used to live. In today's terms, they were once worth several million dollars apiece, but in today's real estate market, they are next to worthless. Value disappeared. The community as a whole is poorer than it was. From the Mayor's point of view, the area has lost its tax base.

|

| New Construction |

Of all these forces, the flight to the suburbs is probably the least destructive to the region, particularly if it is reasonably slow. Out in the suburbs, value is being created as cornfields turn into suburbia, and that added value must be set against the reduced value of the abandoned slum areas. Viewed from the Mayors' perspectives, however, we have a zero sum. The city loses its tax base, the suburbs gain, and local politics soon degenerate into warfare between the suburbs and the city. Not a nice situation, and it cries out for a new civic design. The city politicians have dreamed for a century of city-suburb consolidation, but Philadelphia tried that in 1850. It didn't cure the problem, and it may have created new problems. In any event, suburban politicians live and die on their anti-city rhetoric, and everybody's behavior in the Legislature deserves no kinder description than -- savage.

|

| Orange Station |

Because this issue has been the underlying theme of the Pennsylvania Legislature for two centuries, it repeatedly surfaces in ways that are surprising unless you understand the mechanics of suburban sprawl well enough to see the connection. For example, nowadays a real issue is the three-car family.

During the 19th Century, multi-acre estates spread out along the Main Line of the Pennsylvania Railroad, with the coachman and horses taking plutocrats to the station. Smaller houses, for people who walked to the station, clustered nearby, but you didn't have to go very far from the station to find the gated estates. Suburban development spread out in linear and predictable fashion from the city, along the Main Line. The advent of the automobile freed commuters from the tyranny of railroad station orientation, and middle-class residents could flee the city to areas of the suburbs that were fairly far from the railroad and its stations. But not too far, because there was the problem of the lady of the house, who had to get to the stores. To free her up, the family had to have two cars in the garage. Suburban shopping malls helped her problem, somewhat, but the railroad station was still a magnet.

And then, the majority of married women became working wives, confronting the problem of kids getting to the confounded school. The highly questionable solution of giving the kids a collective car as soon as the oldest got a license, made the oldest kid proudly take the role the coachman used to have, and it caused a lot of teenage turmoil that need not be described here. The point to be stressed is that the three-car family sent home-building into cornfields that were not even close to the main road. Since land gets cheaper the further you get from the city, an economic incentive is created to enter uncongenial social environments, and adopt unexamined attitudes about the environment that are ultimately flatly contradictory.

When the kids leave home, the exurban pioneers no longer need the third car, and think about returning to city life. So far, however, they have been returning to Center City, not the residential neighborhoods they used to call home.

Urban Termites

Slums are occasionally created deliberately. The great difficulty in assembling a large parcel of land in the center of a city, to build a skyscraper, let's say, creates a financial incentive to make the existing occupants of an area believe they want to move. The general technique is to buy a property in the targeted area, then let it deteriorate in such a disgusting way that the neighbors can't wait to get out. That makes the price of neighboring properties go down, so you can buy them and repeat the process. You can even further the project of parcel-assembly by renting the property to stores that sell pornographic movies, or display girls, girls, girls, or play boom boom music. Neighbors complain vociferously about that, so it is necessary to bribe a few officials to get away with it. When you see a sex shop, look around for an official who has taken a bribe to look the other way. And behind that, you'll generally find a real estate developer who wants to put up a skyscraper; he isn't necessarily to be commended for clearing the eyesores with his new building, because maybe he encouraged the eyesores. It might perhaps be possible to describe this behavior as a cyclic part of creative destruction; garbage collection is a necessary function, and you could look at the buildings headed for demolition as merely architectural garbage that needs to be picked up by someone willing to do it. You could say that, but it is good advice to such scavengers that it might be wise to have your own home and central office located in some other city. In Charleston, South Carolina, they have an ingenious law which imposes severe penalties for the crime of demolishing a building by intentional neglect. And they probably have some tar and feathers left over from earlier reconstruction eras.

Somewhat disgusting behavior does have a justification when the intended purpose of the land -- a highway, a bridge, a skyscraper -- is greater than the value of the existing property, as a houses, a drugstore, or a historic landmark. If there is really no other place for the new structure to go, it's a tough decision, because there is a net increase in value after the process is completed. More often, however, there are a number of other places where new development could go, and the race is on to make one particular direction more attractive to a developer by making it far less attractive to everyone else. When the race to the bottom is won by somebody's slum, several other competing slums have been created. If you include them in the calculation, the net change in value may actually be negative.

City government often abets slum creation in two ways. By petty corruption of zoning, policing of vice-like activities, and slack enforcement of maintenance rules. And secondly, by failing to lower taxes when properties get less valuable. This phenomenon is paradoxically more likely to affect the splendid mansions than the little worker's houses because it is politically difficult to lower the assessment on a millionaire's mansion, just because the neighborhood turned less fashionable. The millionaire himself might pay those punitive taxes for his showplace, but the absent heirs -- just dump the place.

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

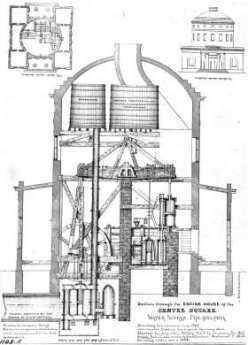

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Friends of Boyd

|

| Boyd Theatre |

Howard B. Haas a lawyer, and Shawn Evans an architect, are captains of a team trying to "save" the old Boyd Theatre at 1908 Chestnut Street. Since Clear Channel, the present owner has invested $13million in the property, and the preservationists agree that renovation of the movie palace to all its former glory would cost between $20million and $30million more, it's easy to understand why every other movie palace in central Philadelphia has been demolished. Furthermore, that area of town is having a resurgence of high-rise construction, so one use of the property must be balanced against others.

|

| Sam Eric |

The Boyd was built in 1928, just before the stock market crash, and closed in 2002. In fact, it changed its name to SamEric in its dying days, but the public remembers it as the Boyd, one of ten movie palaces in center city. The definition of a "palace" is arbitrary but is generally taken to be a theater with more than a thousand seats, normally with hyperbolic architecture to fit its hyperbolic advertising. Scholars of the matter say the earliest movie houses were constructed in Egyptian style, soon evolving into French Art Deco. Ornate, whatever it's called.

The palace concept developed in the era of silent films, with subtitles. Anyone who has experimented with home movies knows that the silent film sort of lacks something, particularly between reels and at times of breakdown in the projection. That's why brass bands played on the sidewalk outside, pipe organs played during intermissions, and all manner of vaudeville appeared on stage. Sound movies, or talkies, were immediately much more popular when they appeared in 1927, and had less need of the window dressing from other distractions which had grown into a moviehouse tradition which was slow to die.

The movie studios owned the films and soon built theaters to display them. The movie business was quite profitable from the start, so studios had the necessary finance to spread a network of very large theaters across the country quickly. The ability to concentrate hyped-up advertising with immediate display of the product in large captive theaters tended to drive the model of the "palace", which was able to sustain higher ticket prices than trickling a larger number of film copies to myriads of small "mom and pop" local theaters. In very short order, going downtown to see movies became at one time the largest reason for suburbanites to go to the center of town on public transportation, fitting in nicely with the concentration of huge department stores, also located there. Restaurants, bars, bowling alleys, and shops grew up to address the crowds. Furthermore, the economic depression of the 1930s slowed down what was to become a relentless automobile-flight to the suburbs. After the spread of free television at home in 1950, the downtown movie palaces were doomed. The legal profession helped, too. Small suburban theater operators eventually won an antitrust suit against what they described as monopoly power of studio-owned center city palaces, so a host of small sharks in the suburbs started to eat the whales downtown. Furthermore, the sound quality was easier to achieve in a smaller auditorium. To tell the truth, fire hazard was also lessened without the arc-lamps needed to project images across a long distance.

So, a new technology interacting with an old theatrical tradition quickly created the movie industry in its downtown movie palace form; more advancing technology quickly destroyed it, with a little help from economics and politics. Good luck to the friends of this historical epoch, who have a monumental task ahead to work up the public nostalgia and political strength required to overcome a huge economic obstacle of the "highest, best use of the land". In many ways, the most valuable contribution of this movie palace restoration movement is to dramatize in the public mind just how urban centers function. Department stores are gone, going in town to the movies is over. How else are you now going to get the couch potatoes to go downtown voluntarily, and often? Just imagine ten palaces simultaneously filling up with several thousand suburbanites apiece, seven nights a week. Without those additional drawbacks on ample display in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, please.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1190.htm

Venturi's Franklin Museum in Franklin Court

|

| Franklin Court Museum |

When Judge Edwin O. Lewis was seized with the idea of making a national monument out of Colonial Philadelphia, he wanted it big. Forty or so years later, it's big all right, but not big enough to encompass the whole of America's most historic square mile. Government ownership in the form of a cross now extends five blocks north from Washington Square to Franklin Square, and four blocks East from Sixth to Second Streets. Restoration and historic display have spread considerably beyond that cross, however, and the Park Service has created ingenious walkways within the working city in the neighborhood. If you thread your way through these walkways, you can stroll for miles within the world of William Penn and Benjamin Franklin. One such unexpected walkway is now called Franklin Court, which essentially cuts from Market to Chestnut Streets, within the block bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets. Hidden in the center is the reconstructed ghost of Franklin's quite large house, sitting in an interior courtyard bounded by a colonial post office, and a newspaper office once operated by Franklin's grandson. And, along the side of the walkway near Chestnut Street, is a fascinating museum of Franklin's personal life, built by no less than Frank Venturi, and operated by Park Rangers in the polished but low-key manner for which the U.S. Park Service is famous.

For some reason, this jewel of a museum has not received the high-powered publicity it deserves. It's off the main Park premises, as we mentioned, and some of the problem has to be attributed to Venturi. As you walk through, you don't expect a huge museum to be there, and it can look pretty inconspicuous as you walk past because it is mostly underground. Take my word for it, it's worth a visit. There are long descending ramps inside the doors, which can be pretty daunting if you are elderly and tired. But, also inconspicuous, there's an elevator if you look around for it. Venturi didn't seem to like windows very much, which is a problem for some people.

There's a movie theater inside there, playing a long list of fascinating documentaries. There's an ingenious automated display of statuettes which utilize spotlights and revolving stages to present Franklin in Parliament, resisting the Stamp Act, Franklin being his charming self before the French monarchs, and the frail dying Franklin getting the Constitutional Convention to approve the document. There are also a variety of ingenious inventions of Franklin's on display in the original, including bifocal glasses, the first storage battery, a simplified clock, several library devices, the Franklin stove, and so on. In some ways, the highlight is the Armonica.

The Armonica is the musical instrument invented by Franklin, for which both Beethoven and Mozart composed special music to exploit its haunting tone. If you ask the nice Park Ranger, she will be flattered to play you a tune on it.

Armonica, Momentarily Mesmerizing

|

| Ben Franklin's Glass Armonica |

Everyone knows Ben Franklin spent a lot of time holding a wine glass. Evidently, he noticed a musical note emerges if you run your finger around the open mouth of the drinking glass, and systematically studied how the tone can be varied by varying the level of liquid in the glass. The same variation in emitted tone relates to variations in the thickness of the glass. So, he set up a series of different sized glasses impaled on a horizontal broomstick, enough to cover three octaves, rotated the broomstick with a treadle like those used for spinning wheels -- and made music. The tone has a haunting penetration to it, which induced both Beethoven and Mozart to write special compositions for the harmonica, and the Eighteenth Century went wild with enthusiasm.

|

| Glass Armonica |

Unfortunately, a number of the young ladies who played the armonica went mad. We now recognize that since the finest crystal glass was used, with very high lead content, the mad ladies were suffering from lead poisoning after repeatedly wetting their fingers on their tongues. As a matter of fact, port wine at that time was stored in lead-lined casks, resulting in the same unfortunate consequences, which included stirring up attacks of gout. Franklin himself was a famous sufferer from gout, which was more likely related to the port wine than playing the harmonica, in his particular case.

Anyway, the reputation for inducing madness added to the spooky sort of sound the instrument made, attracting the attention of a montebank named Franz Anton Mesmer, who falsely claimed to be the father of hypnotism. Mesmer enhanced the society of his stage performances by hypnotizing subjects while an assistant played the harmonica, meanwhile relating all sorts of wild tales about animal magnetism. This was pretty sensational at the time until a young man in an audience suddenly died. It is now speculated that the victim probably had an epileptic seizure, but the news of this public fatal event pretty well finished Mesmer as an evangelist and the harmonica as a musical instrument.

|

| Franklin Court |

There's a replica of an armonica on display in the Franklin Court Museum around 3rd and Chestnut, which we are vigorously assured is not made with leaded crystal glass. The Park Rangers put on two daily performances by request, at noon, and 2:30 PM.

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

Pennsbury Manor

|

| Fairmount |

William Penn once had his pick of the best home sites in three states, because of course he more or less owned all three (states, that is). Aside from Philadelphia townhouses, he first picked Faire Mount, where the Philadelphia Art Museum now stands. For some reason, he gave up that idea and built Pennsbury, his country estate, across the river from what is now Trenton. It's in the crook of a sharp bend in the river but is rather puzzlingly surrounded by what most of us would call swamps. The estate has been elegantly restored and is visited by hosts of visitors, sometimes two thousand in a day. On other days it is deserted, so it's worth telephoning in advance to plan a trip.

|

| Gasified Garbage |

After World War II, a giant steel plant was placed nearby in Morrisville, thriving on shiploads of iron ore from Labrador, but now closed. Morrisville had a brief flurry of prosperity, now seemingly lost forever. However, as you drive through the area you can see huge recycling and waste disposal plants, and you can tell from the verdant soil heaps that the recycled waste is filling in the swamps. It doesn't take much imagination to foresee swamps turning into lakes surrounded by lawns, on top of which will be many exurban houses. How much of this will be planned communities and how much simply sold off to local developers, surely depends on the decisions of some remote corporate Board of Directors.

However, it's intriguing to imagine the dreams of best-case planners. Radiating from Pennsbury, there are two strips of charming waterfront extending for miles, north to Washingtons Crossing, and West to Bristol. If you arrange for a dozen lakes in the middle of this promontory, surround them with lawns nurtured by recycled waste, you could imagine a resort community, a new city, an upscale exurban paradise, or all three combined. It's sad to think that whether this happens here or on the comparable New Jersey side of the river depends on state taxes. Inevitably, that means that lobbying and corruption will rule the day and the pace of progress.

Meanwhile, take a trip from Washingtons Crossing to Bristol, by way of Pennsbury. It can be done in an hour, plus an extra hour or so to tour Penn's mansion if the school kids aren't there. Add a tour of Bristol to make it a morning, and some tours of the remaining riverbank mansions, to make a day of it.

Sacred Places at Risk

|

| Old St. Joe's |

When William Penn invited all religions to enjoy the freedom of Pennsylvania, he created a home for the first churches in America of many existing religions, and furthermore the founding mother churches for many new religions. Regardless of the local congregation, there is obviously a strong wish to preserve the oldest churches of the Presbyterian, Methodist, United Brethren, African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist, Mennonite, and many other denominations. While the founding church of Roman Catholicism was obviously not in Philadelphia, St. Josephs at 3rd and Willing was for many decades the only place in the American colonies where the Catholic Mass could be openly performed. The towering genius of William Penn lay in the combination of an almost saintly wish to spread religious toleration, combined with what must have been a sure recognition that the motive of Charles II in giving him the land, was to get rid of all those dissenters from England.

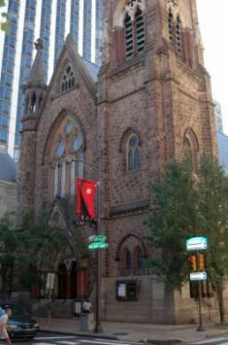

Philadelphia now has a thousand church structures within the city limits, and more than a thousand in the suburbs. However, many church buildings find themselves stranded by the migration of local ethnic groups to other locations, and a decision must be made whether to demolish a relic or sell it to a new population who have moved into the old neighborhood with a new religion. There is still greater discomfort with selling an old church to a commercial enterprise, but even that happens. The resulting bewilderment and dissension among the surviving parishioners is easy to imagine as they face these choices, or fail to face them, and it is readily imagined that the establishment in 1989 of Partners for Sacred Places filled a very important need.

|

| First Presbyterian Church |

The Executive Director, Robert Jaeger, recently described to the Right Angle Club how the Partners operate. First of all, the Constitutional separation of church and state makes it difficult to seek funding or even advice from the Federal government. Pennsylvania has been less hesitant than most states in this regard, but even here the issue of fund-raising is a central issue. One only has to look at the Aztec and Mayan religious sites in Mexico to grasp that there are circumstances when the parishioners of a religion may have completely died out, but their monuments justify state assistance. Private, nondenominational philanthropy seems the easiest route for a society to take, in avoiding the obvious political and legal entanglements of seeming to assist one denomination more than others.

And then there are architectural issues;, can the building be saved at a reasonable cost, is it truly a unique or outstanding piece of art, can a reconstruction go ahead in an incremental way, are the necessary stone or other materials any longer obtainable, do the workman skills exist? In addition to these issues which are commonly presented to a congregation, there are issues they probably have never considered. As congregants move from center-city to the suburbs, they become commuters to church, largely out of touch with the local community and its activities. A survey conducted by the Partners suggests that 81% of the activity which takes place in church buildings on weekdays is conducted by and for non-members of the church; if the two groups lose touch with each other, opportunities are missed, and eventually there may be unnecessary friction. On the other hand, those non-religious activities probably escape the legal prohibitions against government assistance, and may suit themselves as vehicles for indirect government support. The approach has so much promise that Partners for Sacred Places has devised a computer program on their website which provides a way for congregations to assess their assets, and their problems. In fact, the organization conducts extensive training programs for church preservation, and has been forced by the size of the demand to exclude churches that are clearly failing beyond reasonable hope of recovery by their church membership.

The Partnership was originally founded by consolidation of the New York and Philadelphia organizations, to make a stronger national effort. But now things are going the other way. New chapters are springing up in Texas and California. Partners for Sacred Places is obviously proving to be a good idea, effectively managed.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1269.htm

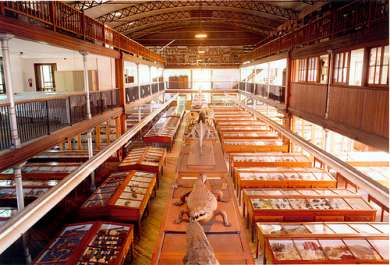

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Quilts, Patchwork Style

Although quilting can be found in the tombs of ancient Egypt, American farm women are correct that they invented an art form.

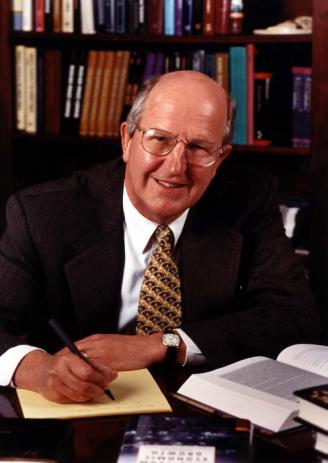

|

| Dr. Fisher |

In the days when transport was primitive, art forms were invented in many places at once, mostly responding to new materials and new technologies. It's irrelevant to the genius of creation, for archivists to pounce on evidence that an art form surfaced a decade or two earlier in one place than another. Creative art could easily have been -- and often was -- invented by five or six people in different regions, each with a just claim to inventing without copying. In the case of quilts, there is a semantic wrinkle, too. If you define quilting as the process of anchoring three layers of cloth together with stitches, then quilts have been found in ruins of ancient China and ancient Egypt. The underlying principle was that three layers of cloth were warmer and stronger than single sheets of cloth or animal skins, so quilting was used for shoes, pants, jackets, and underneath suits of armor. Mary Queen of Scots spent a lot of time in confinement, and examples still survive of tapestries she made with the quilting process. None of this is what American farm women mean when they say that "quilts" are an American invention, and a new art form.

|

| Quilt, Patchwork Style |

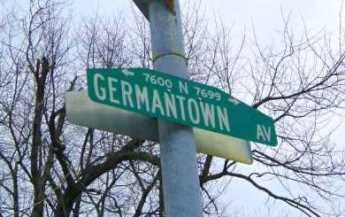

What they mean is patchwork-quilting of bedspreads or counterpanes. To make that specific kind of quilt, you pretty much have to wait for the industrial revolution to provide decorated cotton cloth, then for it to become cheap enough to be used as sacks for flour. That attracts frugal farm wives salvaging material for dresses and shirts, and later re-salvaging pieces of it for patches. Somewhere the idea caught on that decoration was needed for the tops of beds; if these ornaments were usable for extra warmth it was even better. And so, we got patchwork counterpane quilts, incorporating different colored patches into designs. They start appearing around 1750 but gained real popularity around 1830. Since no one was keeping records, it's hard to know if the common diamond design was an outgrowth of the Scotch-Irish street "diamond", or an outgrowth of the hex signs which are commonly believed to have originated in the monastery in Germantown. The path of westward migration would have carried such traditions to the rest of the country, so this analysis has some plausibility. However, the ideas are so simple it would surely be impossible to trace them. What is so unique about this folk art is that the design can be oriented around a piece of a favorite grandparent's shirt or dress, evoking that person's presence and personality in a manner largely incomprehensible to anyone except the immediate family. This intimate quality is easily lost, even in third and later generations of the family, although family traditions can be maintained in the designs and by hearsay.

There may be other traditions of folk art evoking a particular individual who is unrecognizable to outsiders. They might admire features of the design but have no way of knowing the personality of the person celebrated, or making associations with the piece of cloth. But this quilt art becomes established as a family heirloom as almost nothing else could be. Its sweetness is oblivious to the fashion police who contribute a rather aggressive undertone to so much of the art world. For example, in the period between the first World War and the Korean War, it was just about impossible to have a non-modernist painting accepted for a juried show. The same juries who enforced such competitive dictates seemed to forget they denounced the "conservative" academics who excluded impressionist painting a century earlier. During the modernist period, disk jockeys and band leaders likewise serially enforced the various fashions of jazz music; classical music was totally banished. Book reviewers, now a dwindling race, similarly laid down standards of obedience for authors and playwrights on behalf of a style now commonly praised as "liberal". Publishers and producers defied such dictates at their peril, and now must reorient to the coming new standard, called post-modernism.

By contrast, the isolated troubadours of home quilting artistry continue to create as they please, primarily speaking to their families and selling a few less treasured products -- to uncomprehending strangers.

Furniture for the Horse Country

|

| Douglas Mooberry |

Low-end furniture for America is now mostly made in China, and seldom made of wood. Truly American cabinet making tends to be high-end, and high priced. That tendency goes to some sort of extreme around Unionville in Chester County, where a 25-year old company named Kinloch Woodworking holds pride of place. The owner, D. Douglas Mooberry, picked the name Kinloch at random from a map of Scotland, but his selection of southern Chester County was not an accident. The influence of nearby Winterthur has infused that whole region with an interest in fine furniture craftsmanship, and museums like the Chester County Museum and others throughout the nearby Pennsylvania Dutch country provide an ample source of authentic pieces to serve as examples. There's one other factor at work. As Doug Mooberry quickly noticed, people with money usually have lots of it. There really is a market for $28,000 tall case clocks, $18,000 highboys, and $12,000 tables -- if you can convince people in Chester County you are really good.

Although this 12-person company repairs antique pieces, it does not make exact reproductions. It produces new pieces in the old style of the region, based on careful analysis and evaluation of museum pieces from earlier times. Kinloch once aspired to equal the quality of the early artisans, but now aspires to surpass them in quality of materials and workmanship. The more conventional stance of fine artists is to attempt to excel in today's current style, whatever that may be, probably "post-modern". Kinloch artists, however, choose to excel in the style of a long-past era, taking care not to claim the product is antique. Artisans grow up in cooperative clusters; there's a world-famous veneer company nearby and a pretty good hardware company, although the best craftsmen of furniture hardware are still found in England.

|

| Chippendale Table |

The characteristic style of Chester County furniture in the Eighteenth Century was a mixture of two neighboring cultures, Queen Anne, Chippendale, ball and claw Georgian style of Philadelphia; and the "line and berry" inlay style of the Pennsylvania Germans. If carefully executed, this hybrid style can be very pleasing, and you had better believe it requires painstaking craftsmanship. Others will have to explain the significance or symbolism of intersecting hemi-circles in the lines, and the inlaid wood hemispheres, the berries, at the end of the lines. But the technical difficulty of laying strips of 1/16 inch wood in curved grooves only a thousandth of an inch wider, or the matching of 3/8th-inch wood hemispheres into hemispheric holes gouged out of the main piece -- making the surfaces of the inlays perfectly smooth -- is immediately obvious to anyone who ever tried to whittle. Ultimately, however, true artistry lies in combining two unrelated styles without producing an aesthetic clash. By the way, you would be wise to wax such furniture once a year.