Related Topics

Quakers: The Society of Friends

According to an old Quaker joke, the Holy Trinity consists of the fatherhood of God, the brotherhood of man, and the neighborhood of Philadelphia.

Academia in the Philadelphia Region

Higher education is a source of pride, progress, and aggravation.

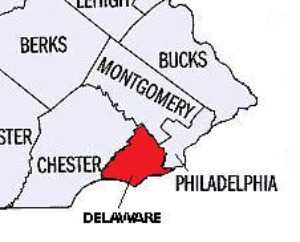

Touring Philadelphia's Western Regions

Philadelpia County had two hundred farms in 1950, but is now thickly settled in all directions. Western regions along the Schuylkill are still spread out somewhat; with many historic estates.

Swarthmore College

|

| Swarthmore College |

The Friends Association for Higher Education lists 17 American institutions as Quaker Colleges, Universities, or Study Centers. Four of these, Swarthmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr and Pendle Hill, are located in the Philadelphia region. Until Haverford College recently adopted co-education, it was once possible to say Haverford was all-male, Bryn Mawr was all-female, and Swarthmore co-ed; Pendle Hill has no undergraduates. That greatly oversimplifies a very distinctive set of complexities, however. Since there is no official connection between the colleges and the church, it is a little hard even to explain the sense in which they are truly Quaker, which is by operating under a strong striving for consensus.

Swarthmore is commonly said to be the most Quaker of the three undergraduate colleges, but only 7% of its students are Quaker and only a quarter of its trustees. The most distinctive feature of the college is the so-called Honors Program, patterned after the tutorial system of Oxford and Cambridge, which was brought there in 1921 by a non-Quaker president who had experienced the system as a Rhodes Scholar. The establishment of this program was heavily supported by the General Education Board, which is to say the Rockefellers. As a reflection of the pressures of graduate schools, and possibly student preference for a greater variety of subject material, only about a third of the students elect to take the Honors Program. It is, however, the central core of the college.

The name of the college derives from Swarthmore, which was the English home of George Fox, the founder of Quakerism. Early Quakers were uncomfortable with the colleges and universities of their day, which had been founded to educate priests and ministers of various other religions, gradually enlarging their mission to include the children of upper-class families. The motto of Eton College embodies much that made Quakers wince: "Eton exists to exert a civilizing influence upon those who are destined to rule." Even the American variation of that there is scarcely an improvement since it would probably say something along the line of offering the opportunity to increase the student's future life income by 70%. It is easy to understand why Quakers wanted to have their own school system, protecting their children from attitudes and influences they disapproved of. Although the Civil War somewhat disorganized the early directions of Swarthmore, for fifty years it was a simple rural college, aimed at avoiding modern influences more than seeking a defined unique role. And then along came Frank Aydelotte.

Very likely, a major appeal underlying the Oxbridge seminar system to Aydelotte and the Quaker trustees was its modern evolution into a model for producing those unusually talented and incorruptible civil servants, who really run the British government under the nominal control of elected officials. Such ambitions necessarily imply a need to attract unusually bright students, and Aydelotte's method was to keep the student enrollment smaller than a well-financed faculty could attract. Unfortunately, as brighter non-Quaker applicants were attracted, more and more Quaker applicants had to be rejected. By 1953, the incoming new president, Courtney Smith, was prompted to make the rueful observation, "Franklin Roosevelt's record at Harvard, and Adlai Stevenson's at Princeton, and Dwight Eisenhower's at West Point, were scarcely, I am told, pace-setting." Almost every American college now faces something like the same conflicted feeling, since globalization implies that all Americans, not merely Quakers, might someday be excluded from their own colleges in order to make room for, say Orientals, who are brighter. Remaining small, however, Swarthmore does have the latitude to seek its own solutions, one of which has been to create the pre-eminent scholarly center for the study of Quakerism.

There are other quiet paradoxes atSwarthmore. From rural simplicity to suburban elegance, the physical transformation of the campus made possible by generous funding might distress only a Quaker. Indeed, Arthur Hoyt Scott of the class of 1895 donated 330 acres of ornamental garden in 1929, composed of beautiful ornamental plants, that no matter what their origin would thrive in the Delaware Valley. Not only is this garden a premier place to visit, but it is also one of the inspirations along with Longwood and Bartram's Gardens for landscaping of the entire Mid-Atlantic region.

And then there is the subsequent history of Frank Aydelotte. True, after he left Swarthmore he became a Quaker, himself. But he left to implement the educational ideas of Mr.Bamburger the department store magnate at the new Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. That is, at that unquestionably pre-eminent intellectual center whose main achievement so far has been the development of, the atom bomb.

REFERENCES

| Swarthmore College: An Informal History: Richard J. WaltonASIN: B0006ELCO8 | Amazon |

Originally published: Wednesday, June 21, 2006; most-recently modified: Thursday, June 06, 2019