0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

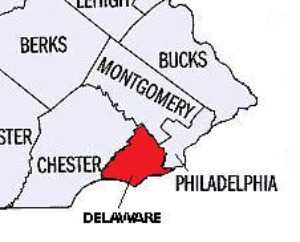

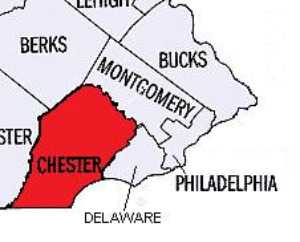

Delaware County, Pennsylvania

.

|

| Delaware County Map |

Corinthian Epistle

|

| Olympia |

Philadelphia had ups and downs as a maritime center. Right now, it's rather down, but what's bad for commercial shipping sort of encourages recreational boating. There was once a time when almost everyone in town had some connection with the sea, and there were a hundred sailing clubs, many of them quite rowdy. Out of this environment grew the Corinthian Movement of amateur sailors, sometimes stated as requiring the owner to sail his own boat. Wanamaker, Drexel, and similar names were once associated with the formation of sailing clubs that wanted to distance themselves from the characteristic rowdy behavior of professional sailors. Yachting thus acquired a snooty flavor. It also had to contend with the plain fact that people with enough money to own a big sailboat were often not agile enough to handle them. Corinth is not terribly far from Olympia in Greece, and it seems likely that qualification for entry into the Olympics was influential in the development of sailing club rules, which tend to emphasize the manner in which the sailor learned his skills. If you learned to sail as an amateur, you qualified, even if you were crewing on someone else's boat. Learning your skills in the Navy is also sort of an ambiguous situation, so membership in a Corinthian Yacht Club cleans up your Olympic credentials.

|

| Corinthian Yacht Club |

It thus happens there are quite a number of Corinthian Yacht Clubs in America, mostly unrelated to each other except competitively. Philadelphia has a Corinthian Yacht Club founded in 1892 out of the remnants of other clubs, and located in Essington on the grounds of former Governor Printz's estate. The food there is famously good, and sunset buffets at the head of Delaware Bay are quite memorable.

|

| J-Boat |

Unfortunately, there are only about fifteen J-boats moored there. Most of the members use some other harbor as their home port, and the blame is placed on the Philadelphia International Airport. The runway was extended out into the river, causing changes in the current to pile up silt outside the yacht club. The club has so far been unable to overcome the Governmental rules which prevent private dredging, so there is gridlock. One can also easily imagine a little class warfare with local politicians, who might not be enthusiastic about using taxpayer's money for the benefit of rich yacht owners, etc, etc.

A river full of lovely sailboats, or even an exciting river race, would greatly enhance the attractiveness of the city as a place to live. Just notice how residents and tourists flock to the riverbank to watch the Occasional visit of tall ships. To the extent that modified dredging and navigation rules would help the process, it certainly needs to be helped.

The Corinthos Disaster

|

| Oil Tanker on Fire |

Fire, huge fire. The Corinthos disaster of January 30, 1975, was the biggest fire in Philadelphia history, and one hopes the biggest forevermore. Its immensity has possibly lessened attention for some associated issues which are nevertheless quite important, too. Like the issue of punitive damages in a lawsuit, or the need to balance environmental damage with a national need for energy independence. And the changing ways that law firms charge their clients. We hope the relatives of the victims will not be offended if the tragedy is used to illustrate these other important issues.

On that cold winter day, two big tanker ships were tied up alongside the opposite banks of the Delaware River at Marcus Hook. The Corinthos was a 754-foot tanker with a capacity of 400,000 barrels of crude oil, tied up on the Pennsylvania side at the British Petroleum dock with perhaps 300,000 barrels still in its tanks at the time of the disaster. At the same time, the 660-foot tanker Edgar M. Queen

|

| Edgar M. Queeny |

with roughly 250,000 barrels of specialty chemicals in its hold, let go its moorings to the Monsanto Chemical dock directly across the river in New Jersey, intending to turn around and head upstream to discharge the rest of its cargo at the Mantua Creek Terminal near Paulsboro. Curiously, a tanker is more likely to explode when it is half empty because there is more opportunity for mixing oxygen with the combustible liquid sloshing around. A tug stood by to assist the turn, but the master of the Queeny felt there was ample room to make the turn under her own power. With no one paying particular attention to this routine maneuver, the Queeny seemed (to only casual observers) to head directly across the river, ramming straight into the side of the Corinthos. Actually, the Queeny had engaged in a number of backing and filling maneuvers, and the sailors aboard were appalled that it seemed to lack enough backing power to stop its headlong lunge at the Corinthos. There was an almost immediate explosion on the Corinthos, and luckily the Queeny broke free with only its bow badly damaged. Otherwise, the fire might have been twice as large as it proved to be with only the Corinthos burning. The explosion and fire killed twenty-five sailors and dockworkers, burned for days, devastated the neighborhood and occupied the efforts of three dozen fire companies. A graphic account of the fire and fire fighting was written by none other than Curt Weldon who was later to become Congressman from the district, but was then a volunteer fireman active in the Corinthos tragedy.

There were surprising water shortages in this fire on the river because the falling tides would take the water's edge too far away from the suction devices for the fire hoses on the shore. The tide would also rise above a gash in the side of the burning ship, floating water in and then oil up to the point where it would flow out of the ship onto the surface of the river. Oil floated two miles upstream from the burning ship and ignited a U.S. Navy destroyer which was tied up at that point. Observers in airplanes estimated the oil spill was eventually fifty miles long. All of these factors played a role in the decision whether to try to put the fire out at the dock or let it burn out; experts continue to argue which would have been better. There were always dangers the burning ship would break loose and float in unexpected directions, that the oil slick would ignite for its full length, and that storage tanks on shore would be ignited. The initial explosion had blown huge pieces of iron half a mile away, and the ground near the ship was littered with charred, dismembered pieces of flesh from the victims.

, Of course, there was a big lawsuit. When a ship is tied up at a dock it certainly feels aggrieved when another ship crosses a river and rams it. The time-honored principle of admiralty law holds that the owner of an offending ship is not liable for damages greater than the salvage value of its own hulk, which in this case might have been about $3 million. The underlying assumption is that the owner has no way of knowing what is going on thousands of miles away, no control over it, no power to respond in a useful way. Enter Richard Palmer, counsel for the Corinthos. Palmer was aware that the National Transportation Safety Board collects information about ship maintenance inspections in order to share useful information for the benefit of everyone. His inquiry revealed that the inspections of the Queeny for four years before the crash had repeatedly demonstrated that the stern engine had a damaged turbine, and was only able to drive the ship at 50% of its rated power. Why this turbine had not been repaired was now irrelevant; the owners of the ship did have relevant information and had failed to act in a timely safe fashion. The limitation of liability to the salvage value of the hulk now no longer applied if the negligence was judged relevant. The defendants, the owners of the Queeny, decided to settle. While the size of the settlement is a secret of the court, it is fair to guess that it approached the full value of the suit, which was $11 million. Mr. Palmer, by using his experience to surmise that maintenance records might be available at the Transportation Agency, and recognizing that the awareness of the owner might switch the basis for the compensation award from hulk value (of the defendant's ship) to the extent of the damage (to the plaintiff's ship), probably tripled the damage settlement.

Reflections on the extraordinary benefit to the client from a comparatively short period of work by the lawyer leads to a discussion about the proper basis for lawyers fees. Senior lawyers feel that the computer has revolutionized lawyer billing practices, and not for the better. Because it is now possible to produce itemized billing which summarizes conversations of less than a minute in duration, services for the settlement of estates can be many pages long, mostly for rather routine business. Matrimonial lawyers are entitled to charge for hours of listening to inconsequential recriminations; lawyers can bill for hours of time spent reading documents into a recording machine, or sitting wordlessly at depositions. Since the time expended can now be flawlessly measured and recorded on computers, there is little room for a client to remonstrate about their fairness. Discomfort about this system underlies much sympathy for billing for contingent fees, where the lawyer is gambling all of his expenses and effort against a generous proportion of the award if he wins the case, nothing at all if he loses. This latter system, customary in slip and fall cases and justified as permitting the poor client to have proper representation, undoubtedly promotes questionable class action suits and often leads to accepting personal liability suits which should be rejected for lack of merit. The thinking underlying personal injury firms is widely said to be: most insurance companies will settle for modest awards in cases without merit because the defense costs would be no less than that amount, and occasionally a personal liability case gets lucky and extracts a huge award.

Listen to one old-time lawyer describe how legal billing used to be. After the case was over, the lawyer and the client sat down to a discussion of what was involved in the legal work, and what it accomplished for the client. A winning case has more evident value than a losing one, provided the lawyer can effectively describe the professional skills that helped bring it about. The whole discussion is aimed at having both parties leave the discussion satisfied. To the extent that both parties actually are satisfied with the value of the services, the esteem and reputation of the legal profession are enhanced. And the lawyer is a happy and contented member of a grateful community. If he can occasionally claim a staggering fee for a brief but brilliant performance, as in the case of the explosive fire on the Corinthos -- well, more power to him.

It does not take much familiarity with oil refineries to make you realize that cargoes of crude oil are a very dangerous business. We are accustomed to hearing jeers at those who protest, "Not in my backyard", and we deplore those who would jeopardize our national security to protect a few fish and trees in the neighborhood of potential oil spills. Since we do have to import oil and we do therefore have to jeopardize a few selected neighborhoods to accomplish this vital service, the opponents are sadly destined to lose their protests. But that doesn't mean their concerns are trivial. The shipping and refining of oil are dangerous. We just have to live with it and be ready to pay for its associated costs.

Chester: To the Dark Tower

|

| William Penn |

Chester is the original word for Castle in old English, and accounts for towns called Manchester, Lancaster, Dorchester in the Midlands of England. Although much is made of his Welsh ancestry,William Penn grew up and lived in the neighborhood of Manchester. When he first landed in his new colony, he named the place Chester before deciding to move upriver to be above the mudflats and snags at the abrupt turn of the river where we now have an international airport. On several occasions, this protection from pirates and invaders made it possible to remain rich and prosperous without abandoning Quaker pacifist principles. As a further bit of history, the second public reading of the American constitution took place in the courthouse at Chester. During the industrial revolution, Chester became a mighty industrial town somewhat in advance of Philadelphia. The industry has, sadly, abandoned Chester.

Chester repeats the age-old tradition that slums are created when towns are abandoned, making cheap housing available. There's even a particular Chester twist to this principle: the old Sun Shipyards have been turned into a casino. Now, that will create poverty if anything will.

|

| Amtrak's Northeast Corridor |

Peter Barrow is a local real estate man who is determined to lead a revival of the old Chester, and certainly makes a good case for its future. Although much of the city was abandoned, the infrastructure remains. The roads, sewers, water supply, railroads, port facilities may be old but they are essentially intact, making revival much cheaper. Chester is still served by the R2 train from Philadelphia to Wilmington, and is on the main line of Amtak's Northeast Corridor. It's now near the airport, and near the electronics industry developing in Chester County along Route 202. Those things are economic drivers, and they are social ones, too. The old Chester urban Democratic machine and the rural Delaware County Republican machine can no longer afford to remain ossified in perpetual denunciation, in the face of new residents with new outlooks on things. So, there's agitation for reforms and both votes and discontent to propel it forward.

Given a magic wand, the one thing Mr. Barrow would change would be education. The public schools are undisciplined and unsafe, and mobilized by the teachers' unions to resist charter schools no matter what. Things have even gone to the point where Widener University is thinking about starting a charter high school, and the more graduates of charter schools the more momentum builds up for still more charter schools. Hidden in this struggle are two less defensible issues: parochial schools and vocational schools, pro, and con. The struggle over church schools goes back to the founding of our country in the sixteenth century and firmly resists any objectivity about whether parochial schools are better schools, or not. For them, that's not the point. The other tradition at play here is the historic opposition to vocational schools by trade unions. This one might be a little easier to work with since resistance to the development of more plumbers and carpenters was understandable enough during the industrial days of the city, but really is no longer relevant in an era when we now must import illegal immigrants to serve our needs in the mechanical trades.

Chester seems to have a chance to get its act together. Success or failure of this important the struggle could well depend on one or the other of the entrenched political machines, urban and suburban, seeing an opportunity -- and grabbing it.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1322.htm

Laran Bronze

|

| World War II Memorial |

Bronze is the term for alloys of copper, most often mixed with tin, aluminum or whatever in varying proportions. Although the Bronze Age was one of the earliest stages of civilization, most of us would still have a hard time even stating the proper mixture of metals we might need to manufacture some bronze object for some particular purpose. No doubt Alexander the Great and his friends just stumbled on a mixture suitable for swords, helmets, and shields, but nowadays we expect a little more precision than that. So, go visit the engineers and artisans who occupy a whole block of downtown Chester and discover where the engineers take over from the sculptors. For example, the bronzes of the World War II Memorial in Washington were fabricated here, eventually bringing the final bill for the Memorial to $197 million. Whatever Laran may be, it isn't cheap.

|

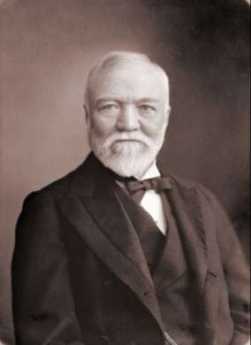

| Andrew Carnegie |

Because of the size and weight of monumental bronzes, there is a tendency for bronze fabricators to be chosen in the general neighborhood of the permanent site of the statue. Even so, most large pieces are cast in smaller pieces and welded together at the site. Because that leads to more external struts that have to be trimmed and smoothed out, and more welding, there is a constant struggle to improve the technology to eliminate chop-ups. However, the bigger the piece, the harder it is to support with internal steel struts, so there is a constant process of re-engineering which is considerably under-appreciated. Since Larry Welker the proprietor of this operation went to Carnegie-Mellon, it brings up an analogous situation in steel fabrication. Andy Carnegie is mostly remembered for giving away libraries and mistreating his employees, but in fact, his achievement was an engineering one. His steel mills were four times as productive and efficient as his nearest competitor (Krupp of Germany). That not only made him the richest man in the world, it also made it possible for America to defeat Germany in World War I, and eventually become the dominant superpower.

Since sculptors are in a position to designate the bronze fabricator of their work, it would be wise for the fabricator to be nice to sculptors. However, computers have stuck their nose in this business, as they have in most businesses. A sculptor ordinarily makes a small model whose image is scanned into a computer and then blown up to final size. From this, a positive mold is made, from that a negative mold, and from that, the final positive bronze shell is cast. But once you pass that image through a computer you open up the possibility of synthetic images made through the mechanisms that make animated movies; and maybe eliminate the need for the sculptor entirely. That prospect naturally displeases sculptors, as does the potential for counterfeiting and exporting jobs.

Just about everything about bronze sculpture revolves around its massive weight. That's why bronze statues are typically hollow but carried too far, the statue can't support its own weight and must have internal steel struts. The internal struts are mainly stainless steel, often encased in the plastic sheathing. The molds which make these eggshells are generally made of ceramic, which is melted sand. The process starts with wax coatings, often a quarter-inch thick dipped in fine sand, then a layer of coarse sand finally baked into ceramic. That's the negative mold; the positive mold from which it is made starts with wax, covered by latex, covered by plaster of Paris. Since a lot of steps don't come out perfectly, they have to be repeated. All in all, it becomes convincing that spending $197 million for a war memorial is entirely legitimate, because we haven't even described the costs for the artist at one end of the process, and the appalling transportation issues at the final step.

Although the WWII Memorial isn't even in Philadelphia, it's surely worth a trip to Washington to see what Philadelphia can do. While you are there, look for the "Easter Eggs". That's the term for humorous images hidden by the artist within the serious larger object. This too is a tradition going back to ancient times; in the case of the War Memorial, the artist hid images of at least one soldier "goofing off" in each freeze. Perhaps even that could be done by computer, but it's harder.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1291.htm

Swarthmore College

|

| Swarthmore College |

The Friends Association for Higher Education lists 17 American institutions as Quaker Colleges, Universities, or Study Centers. Four of these, Swarthmore, Haverford, Bryn Mawr and Pendle Hill, are located in the Philadelphia region. Until Haverford College recently adopted co-education, it was once possible to say Haverford was all-male, Bryn Mawr was all-female, and Swarthmore co-ed; Pendle Hill has no undergraduates. That greatly oversimplifies a very distinctive set of complexities, however. Since there is no official connection between the colleges and the church, it is a little hard even to explain the sense in which they are truly Quaker, which is by operating under a strong striving for consensus.

Swarthmore is commonly said to be the most Quaker of the three undergraduate colleges, but only 7% of its students are Quaker and only a quarter of its trustees. The most distinctive feature of the college is the so-called Honors Program, patterned after the tutorial system of Oxford and Cambridge, which was brought there in 1921 by a non-Quaker president who had experienced the system as a Rhodes Scholar. The establishment of this program was heavily supported by the General Education Board, which is to say the Rockefellers. As a reflection of the pressures of graduate schools, and possibly student preference for a greater variety of subject material, only about a third of the students elect to take the Honors Program. It is, however, the central core of the college.

The name of the college derives from Swarthmore, which was the English home of George Fox, the founder of Quakerism. Early Quakers were uncomfortable with the colleges and universities of their day, which had been founded to educate priests and ministers of various other religions, gradually enlarging their mission to include the children of upper-class families. The motto of Eton College embodies much that made Quakers wince: "Eton exists to exert a civilizing influence upon those who are destined to rule." Even the American variation of that there is scarcely an improvement since it would probably say something along the line of offering the opportunity to increase the student's future life income by 70%. It is easy to understand why Quakers wanted to have their own school system, protecting their children from attitudes and influences they disapproved of. Although the Civil War somewhat disorganized the early directions of Swarthmore, for fifty years it was a simple rural college, aimed at avoiding modern influences more than seeking a defined unique role. And then along came Frank Aydelotte.

Very likely, a major appeal underlying the Oxbridge seminar system to Aydelotte and the Quaker trustees was its modern evolution into a model for producing those unusually talented and incorruptible civil servants, who really run the British government under the nominal control of elected officials. Such ambitions necessarily imply a need to attract unusually bright students, and Aydelotte's method was to keep the student enrollment smaller than a well-financed faculty could attract. Unfortunately, as brighter non-Quaker applicants were attracted, more and more Quaker applicants had to be rejected. By 1953, the incoming new president, Courtney Smith, was prompted to make the rueful observation, "Franklin Roosevelt's record at Harvard, and Adlai Stevenson's at Princeton, and Dwight Eisenhower's at West Point, were scarcely, I am told, pace-setting." Almost every American college now faces something like the same conflicted feeling, since globalization implies that all Americans, not merely Quakers, might someday be excluded from their own colleges in order to make room for, say Orientals, who are brighter. Remaining small, however, Swarthmore does have the latitude to seek its own solutions, one of which has been to create the pre-eminent scholarly center for the study of Quakerism.

There are other quiet paradoxes atSwarthmore. From rural simplicity to suburban elegance, the physical transformation of the campus made possible by generous funding might distress only a Quaker. Indeed, Arthur Hoyt Scott of the class of 1895 donated 330 acres of ornamental garden in 1929, composed of beautiful ornamental plants, that no matter what their origin would thrive in the Delaware Valley. Not only is this garden a premier place to visit, but it is also one of the inspirations along with Longwood and Bartram's Gardens for landscaping of the entire Mid-Atlantic region.

And then there is the subsequent history of Frank Aydelotte. True, after he left Swarthmore he became a Quaker, himself. But he left to implement the educational ideas of Mr.Bamburger the department store magnate at the new Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. That is, at that unquestionably pre-eminent intellectual center whose main achievement so far has been the development of, the atom bomb.

REFERENCES

| Swarthmore College: An Informal History: Richard J. WaltonASIN: B0006ELCO8 | Amazon |

Tales of the Troop

|

| Dennis Boylan |

Dennis Boylan, the former commander of the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry, has been poking around in the archives up at the Armory, and was invited to tell the Right Angle Club about it. In all its history, there have only been 2500 members of the troop, but they have been a colorful lot, leaving lots of history in bits and pieces. The troop boasts that it has seen active duty in every armed conflict of America, and means to continue to fight as a unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard. However, we have lately had so many actions, the troop has had to split off units to be able to go to the Sinai Peninsula, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan and whatever is going to come next. An eighteen month tour of active duty takes a lot out of a citizen soldier's life, but no one is complaining, and there is no fall-off in volunteers.

Although most troopers are polite and taciturn, it is probably hard to remain unaffected by association with people like A.J. Drexel Biddle, a pioneer of the bayonet and hand-to-hand fighting, much sought after for training other units of the military. Or George C.Thomas, who was a golf course architect, but also a seaplane expert, responsible for the seaplane ramps next to the Corinthian Yacht Club along Delaware. Or Rodman Wannamaker, responsible for aeronautic development, also down in the marshes where the Schuylkill joins Delaware. Robert Glendinning, who was notable for other adventures, was also an early pioneer in airplanes. As a matter of fact, Henry Watt had himself flown from Society Hill to Wall Street in a seaplane, when he was President of the New York Stock Exchange.

It's hard to believe, but a former trooper named Eadweard Muybridge distinguished himself in the art world, as a result of a bet with Leland Stopford, that a horse at a gallop reaches a point where all four feet are simultaneously off the ground. The consequence was a famous set of rapid-sequence photographs which are quite famous at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. There are elephants, horses, people in various states of undress which remain as interesting artworks as well as scientific evidence that horses feet do indeed leave the ground. But in case anyone believes that Muybridge was some sort of sissy from the art world, there is the story that he caught his wife in an affair and shot the other man dead. As one might expect, the jury found him not guilty, on the grounds of justifiable homicide. With a name like Eadwaerd, it's probably necessary to demonstrate your manliness.

Robert Glendinning, class of 1888 at Penn, became Governor of the New York Stock Exchange, founded Chestnut Hill Hospital and the Philadelphia School for the Deaf. And Thomas Leiper makes a pretty good claim for starting the first railroad in America. It was only 2 miles long, in Swarthmore, and built because he was not permitted to extend his canal for the purpose of transporting stone from upstate quarries. The railroad developed into the Pennsylvania Railroad; Leiper's house, "Strathaven" is still an important Delaware County landmark.

|

| Tank in Philadelphia |

And then, there's the story of the salute to the QE2. When the liner made a tour up the Delaware, a search was made for cannons to provide a proper salute, and the call came to the Troop. Well, they had a tank, and they could fit a simulator on the tank's gun. So, the tank rumbled down Broad street to do its duty. South Philadelphia responded in character, too. Instead of stopping to admire the novelty of a moving tank, the drivers just honked their horns and drove around it.

Main Line Oligarchy

|

| John Gunther |

"In the Philadelphia suburbs, set in an autumnal landscape so ripe and misty that it might have been painted by Constable....lives an oligarchy more compact, more tightly and more complacently entrenched than any in the United States, with the possible exception of that along the North Shore of Long Island....The Main Line lives on the Main Line all year around...It is one of the few places in the country where it doesn't matter on what side of the tracks you are. These are very superior tracks.....What does the Main Line believe in most? Privilege."

John Gunther -- Inside U.S.A.

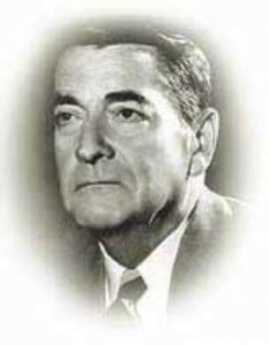

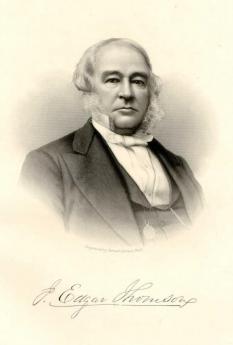

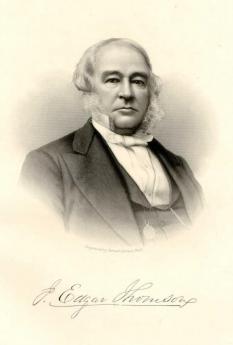

J. Edgar Thomson, Pres. PRR 1852-1874

|

| J Edgar Thomson |

The third president of the Pennsylvania RR converted a local Philadelphia line into a national railroad, the largest corporation in the world. Thomson, born in the Quaker country of Springfield, Delaware County, was the son of a chief engineer of the Delaware-Chesapeake Canal and had worked closely with his father. After an introduction to the rail business, he worked on four other railroads before joining the Pennsy at the age of 29. The State of Pennsylvania had by then constructed a series of unsuccessful canals along most of its important waterways during the Whig days of faith in government, but Thomson knew canals very well and recognized that their rights of way were best transformed into rail lines. By acquiring these unprofitable companies, he rapidly changed the PRR into a state-wide rail network, of which the famous Horseshoe Curve at Altoona was the most notable achievement. From there he moved to convert wood-burners into the coal-burning locomotives developed in Philadelphia and shifted from iron rails to steel ones. The probably unexpected effect was to convert all railroads in the nation into customers of steel and coal, Pennsylvania's main resources. Andrew Carnegie was so pleased he renamed his main steel company into the J. Edgar Thomson Works.

|

| Steam Engine on The Horseshoe Curve |

Thomson was quiet and conservative, never engaging in the high-jinks so characteristic of the rail barons of that day, leasing land rather than buying it whenever possible, expanding steadily but methodically, and never confusing revenue growth with profits. By 1870, Pennsylvania had expanded to a Jersey City terminus at New York harbor, and Chicago and St. Louis at the western ends. Within Pennsylvania, the line had expanded from 250 miles of track to over 6000. It was the largest corporation in the world. Underneath all this expansion was the Thomson system of decentralized management, essentially consisting of giving local control to division superintendents, but standardizing the corporation to superior approaches as they surfaced among the networked superintendents. His was a brilliant synthesis of the precision of an engineer combined with the cooperative sharing of a Quaker meeting. It was easy to describe but difficult to imitate, particularly by executives who boasted lifelong avoidance of the approaches of both the engineering profession and the cooperative diffident Quakers, in favor of swashbuckling, overborrowing, and muscle -- so popular at the time of the Gilded Age.

Thomson's fortune grew to seven or eight million dollars. While that was both comparatively modest by railroad standards and yet extremely affluent for the times, at his death, he had mostly given it to charity.

Delaware County Travel Suggestions

Tyler Arboretum

|

| Tyler Arboretum |

There are over thirty arboreta in the Philadelphia region, and one of the oldest and largest is located in Delaware County. The 650 acres of the Tyler Arboretum, adjoining 2500 acres of a state park, create a rather amazing wooded area quite close to heavily settled urban Philadelphia. The Arboretum is located on land directly deeded by William Penn, but it was privately held until 1940 and so is not as well known as several other arboreta of the region. The early Quakers, it may be recalled, often disapproved of music and "artwork", so their diversions tended to concentrate on various forms of natural science. The first director of the Tyler, Dr. John Wister, planted over 1500 azalea bushes as soon as he took office in the 1940s. They are now seventy or eighty years old, quite old and big enough to make an impressive display. Even flowering bushes seemed a little fancy to the original Quakers.

The interests of the earlier owners of the property were more focused on trees, especially conifers. The property contains several varieties of redwoods, including one impressive California redwood, said to be the largest east of the Mississippi. High above the ground, it splits into two main branches, the result of depredation by someone cutting the top off for a Christmas tree. So a large area near Painter Road is enclosed by a high iron fence, containing most of the conifer collection, and warding off the local white-tailed deer. Several colors of paint are to be seen high on many prominent trees, marking out several walking trails of varying levels of difficulty.

And then there are large plantings of milkweed, providing food for migrating butterflies; near a butterfly educational center. There are large wildflower patches and considerable recent flower plantings around the houses at the entrance. Because of the, well, Christmas tree problem, several houses on the property are still occupied.

The only serpentine barren in Delaware County is located on the property; we have described what that is all about in another essay. As you would imagine, there are great plant and flower auctions in the spring, conventions of butterfly and bird-watching groups at other times. The educational center is attracting large numbers of students of horticulture these days, and photographers. Flower gardens and photographers go together like Ike and Mike.

It's a great place for visitors, for members who are more involved, and for those with serious interests. With all that land to cover, some ardent walkers have enough ground to keep them regularly busy. Becoming a volunteer is a sign of serious interest, and that group is steadily growing. For a place that traces back to William Penn, it's slowly getting to be well known.

American Chestnut Trees

|

| American Chestnut tree |

RECENTLY, John Wenderoth of the Tyler Arboretum visited the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia, bringing an astounding account of the triumph, near-extinction, and revival of the American Chestnut tree. The Tyler Arboretum, and this man, in particular, is at the center of the movement to rescue the tree, although the modern Johnny Appleseeds of the movement seem to be a Central Pennsylvanian named Bob Leffel, and a geneticist named Charles Burnham. Together, they had the vision and drive to enlist a thousand volunteers to plant seedlings in Pennsylvania; and there are many other volunteer groups in other states within Appalachia. About 45,000 Chestnut hybrids have been planted, surrounded by wire fencing to protect the new trees until they grow too tall for deer to reach the leaves. Here's the story.

In 1904 it was estimated that a fourth of all trees in the Eastern United States were American Chestnuts. The tree typically grew to eighty feet before permanent branches took over, so the shading and tall pillars of tree trunks gave the forest a particular cathedral-like distinctiveness, much celebrated by such authors as James Fennimore Cooper. The wood of the American Chestnut tree is rot-resistant, so it was favored by carpenters, log-cabin builders, and furniture makers. It once was a major source of tannin, for leather tanning. The nuts were edible, but it has been a long time since they were available for much eating. The chestnuts you see roasted by sidewalk vendors are primarily Chinese Chestnuts, which actually come to us from South Korea. The Buckeye, or horse chestnut, produces a pretty and abundant nut but is too bitter for most tastes. For whatever reason, a fungus was first discovered to infect the chestnuts of the Bronx Zoo in 1905, attracting the attention of Teddy Roosevelt and his Progressive naturalist friends, but to little avail. The fungus (Cryptomeria parasitic) enters the tree through cracks in the bark, flourishes in the part of the tree which is above ground, leaving the roots undisturbed. Ordinarily, when this sort of thing happens, the roots send up shoots which keep the tree alive and flourishing. Unfortunately, the abundant deer of this area quickly nipped off the shoots as they appeared, and finally, the trees died. It took only a decade or so for this combination of natural enemies to wipe out the species, and today it is unusual to see lumber from this source. The forests of Chestnuts have been replaced by other trees, mostly oaks. The Chinese chestnut, however, proved to be resistant to the fungus, even though it does not grow to the same height.

|

| Chinese Chestnuts |

After many futile but well-meaning efforts to save the trees by foresters, friends of the American Chestnut tree turned to geneticists. The goal was to transfer the fungus resistance gene from the Chinese Chestnut to a few surviving American Chestnuts. It took six or seven generations of cross-breeding to do it (four generations of seedlings, then crossing the crosses, then weeding out the undesirable offspring), but eventually, the Tyler Arboretum was supplying truckloads of seedlings to the volunteers to plant in likely places. It's going to take many years for the seedlings to grow in sufficient numbers to make an impact on our forests, and eventually on our carpenters, but that effort is underway with gusto. If anyone wants to volunteer to join this effort, there appears to be room for plenty more people to help.

| Posted by: Chris Templin | May 26, 2013 12:20 PM |

11 Blogs

Corinthian Epistle

Corinth and Olympia are in Greece, both famous for amateurism in sports. A Corinthian yacht club is a type of yacht club, with no professional sailors. If you hired sailors for your yacht, and who didn't, you were supposed to keep it somewhere else.

Corinth and Olympia are in Greece, both famous for amateurism in sports. A Corinthian yacht club is a type of yacht club, with no professional sailors. If you hired sailors for your yacht, and who didn't, you were supposed to keep it somewhere else.

The Corinthos Disaster

We hope the 1975 Corinthos disaster proves to be the worst fire in Philadelphia history; it's hard to imagine a bigger one.

We hope the 1975 Corinthos disaster proves to be the worst fire in Philadelphia history; it's hard to imagine a bigger one.

Chester: To the Dark Tower

The ancient town of Chester struggles to revive..

The ancient town of Chester struggles to revive..

Laran Bronze

Occupying an entire block of industrial Chester, a little industry of mechanized artist-engineers make most of the big bronze statues in Eastern America.

Occupying an entire block of industrial Chester, a little industry of mechanized artist-engineers make most of the big bronze statues in Eastern America.

Swarthmore College

Tales of the Troop

Dennis Boylan is collecting stories from the archives of Philadelphia's First City Troop. Someday, it should result in a great book.

Dennis Boylan is collecting stories from the archives of Philadelphia's First City Troop. Someday, it should result in a great book.

Main Line Oligarchy

Apparently, the Main Line offended John Gunther.

Apparently, the Main Line offended John Gunther.

J. Edgar Thomson, Pres. PRR 1852-1874

J. Edgar Thompson was a quiet Quaker engineer who expanded the Pennsylvania Railroad over the old canal system, shifted from wood to coal, organized the personnel structure to meet modern needs, and converted PRR from a local to a national railroad.

J. Edgar Thompson was a quiet Quaker engineer who expanded the Pennsylvania Railroad over the old canal system, shifted from wood to coal, organized the personnel structure to meet modern needs, and converted PRR from a local to a national railroad.

Delaware County Travel Suggestions

Thomas R. Smith, a.k.a., William Penn is a local expert on Delaware County (and William Penn). He offers these tips on three historic places to visit in Delco.

Thomas R. Smith, a.k.a., William Penn is a local expert on Delaware County (and William Penn). He offers these tips on three historic places to visit in Delco.

Tyler Arboretum

A 650-acre Arboretum next to a 2500-acre state park makes for a lot of nature walks and bird watching, as well as a gazillion azaleas and tree specimens. The only serpentine barren in Delaware County is located there.

A 650-acre Arboretum next to a 2500-acre state park makes for a lot of nature walks and bird watching, as well as a gazillion azaleas and tree specimens. The only serpentine barren in Delaware County is located there.

American Chestnut Trees

Scarcely a century ago, American Chestnut trees were a quarter of all trees in America. Now, they are almost all gone, but a thousand volunteers are trying to rescue them.

Scarcely a century ago, American Chestnut trees were a quarter of all trees in America. Now, they are almost all gone, but a thousand volunteers are trying to rescue them.