2 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

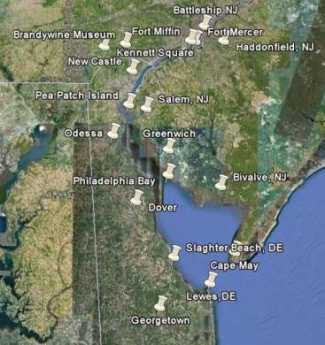

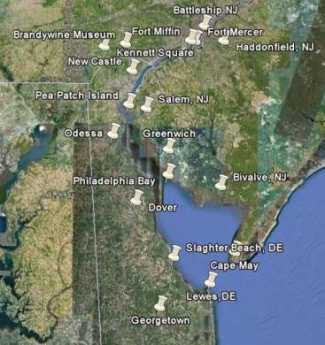

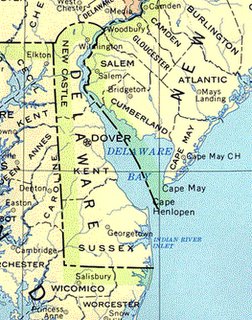

Land Tour Around Delaware Bay

Start in Philadelphia, take two days to tour around Delaware Bay. Down the New Jersey side to Cape May, ferry over to Lewes, tour up to Dover and New Castle, visit Winterthur, Longwood Gardens, Brandywine Battlefield and art museum, then back to Philadelphia. Try it!

Start in Philadelphia, take two days to tour around Delaware Bay. Down the New Jersey side to Cape May, ferry over to Lewes, tour up to Dover and New Castle, visit Winterthur, Longwood Gardens, Brandywine Battlefield and art museum, then back to Philadelphia. Try it!

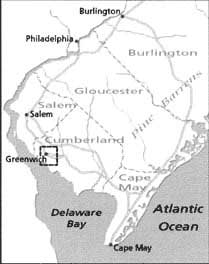

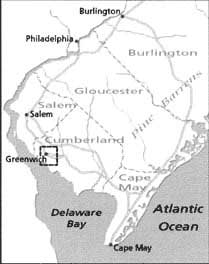

Benjamin Franklin, naturally, was the first to notice that the Delaware River wasn't a normal or at least ordinary river. In fact, coming downstream you might say the Delaware River ends at Trenton, emptying into what was once clearly a bay separating Pennsylvania from that barrier island we now call southern New Jersey. At Trenton, the bay filled in and attached the sandy island to the mountainous coast in a strip running north from Trenton to New Brunswick. South Jersey is a sandy peninsula if you wish, divided from a second more southerly sandy peninsula that we call the state of Delaware, or the Delmarva Peninsula.

From the viewpoint of migrating Europeans, the dominant issue was trees. The land north of Salem was an oak forest, very suitable for ship building. But bad for farming, because you first had to cut down those trees and pull up their stumps before you could plant anything. For at least the first year after settling, you had to subsist on what you could hunt or fish. If you couldn't farm, you might likely starve to death. Our ancestors, I'm sorry to say, hated trees and mostly continued to hate them until at least 1900. Flat marshy land around an inlet, estuary, or river delta was much to be preferred. The Dutch, who had mastered this salt marsh environment around the mouth of the Rhine, were enthusiastic early settlers of Delaware Bay, and the Swedes who were pretty good fishermen were also attracted. Both learned in time there was a big problem; swamps breed mosquitoes, and mosquitoes carry malaria, yellow fever, dengue, etc. But curiously that led to wholesale abandonment of some pretty cute Colonial villages in original condition, which are today still worth an informed visit before termites and Wal-Mart get to them.

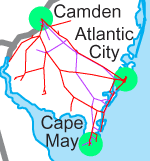

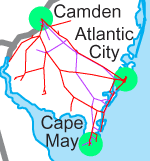

Day One: Camden to Cape May

Settlements for three centuries have clustered along both sides of the Delaware Bay, like beads on two parallel strings.

|

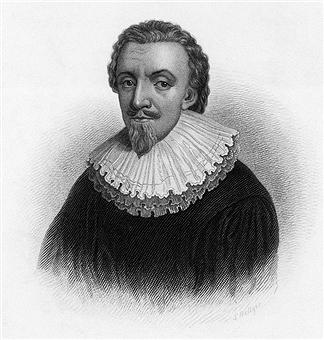

| Dr. Fisher |

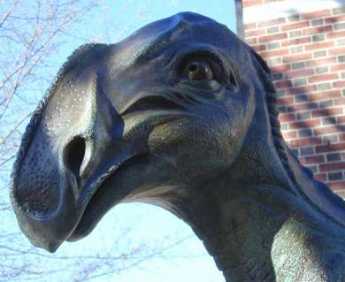

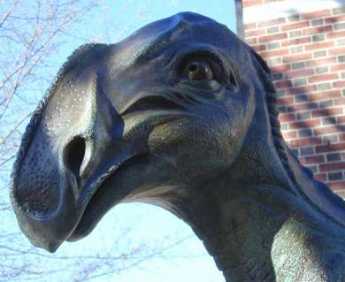

The Capital of southern New Jersey alternated between Salem and Burlington, and the King's Highway ran between them atop a clay ridge all of fifty feet above sea level. Colonial villages are strung along Kings Highway about ten miles apart, just like villages in the Midwest and for the same reason. That's about the distance a farmer's wagon could travel to market and return in one day. Travel by boat modified that somewhat. One unexpected feature: the marl clay ridge was eventually found to contain the first known dinosaur bones, still proudly on display at the Academy of Natural Sciences. We'll defer until Day Two describing the interesting origins of the coastal route on the Delaware side of the bay below the big river bend at Salem. In New Jersey the counterpart is the Del-Sea Drive, now rapidly fragmenting in response to school crossings and traffic. Although almost everything of interest is along these three roads, for this tour we propose taking President Eisenhower's interstate highway system, with side-trips as needed.

The retreating British Army ferried out of Philadelphia in 1778, went from Camden to Haddonfield and turned north on King's Highway. For this tour, we turn south from Haddonfield, pausing for a glance back at Camden. Poor Camden scarcely exists anymore, but the battleship New Jersey is parked there, the waterfront view is awesome, and Walt Whitman's home is open to tourists. Once the home of shipbuilding, Campbell's Soup, RCA/Victor, and the terminus of railroads at the ferries to Philadelphia, the town was first threatened by isolation by the Pennsylvania Railroad going down the other side of the river in 1839, but ultimately made economically redundant by the construction of the Ben Franklin Bridge in 1926. An interesting sociological study called Camden After the Fall relates how one futile effort after another to restore Camden after 1950 led only to riots and chaos; it's difficult to suggest anything which has not already been tried and abandoned. The present unstated but relentless approach is to tear the obsolete buildings down as they deteriorate, leaving vacant land which will eventually coalesce and become attractive to developers. Toll houses could be found along the turnpike to Haddonfield until 1960, but the automobile made Camden obsolete. What's left begins with the suburbs five miles away.

|

| New Jersey Line |

Haddonfield was a plain little Quaker town with undiscovered dinosaurs buried underneath it until the Revolution when the fugitive New Jersey legislature met in the Indian King Tavern and created the State of New Jersey. Because the Pennsylvania/New Jersey fortifications of the Delaware River at Fort Mifflin/Red Bank blocked the British fleet, Hessians were sent to attack New Jersey's Fort Mercer from the rear, staying overnight in Haddonfield. One young Quaker, a famous runner, ran ten miles to alert the defenders of Fort Mercer, who then defeated the Hessian attackers the next day by pretending not to notice the Hessians until they suddenly turned around and ambushed them. Later on, after the British occupied Philadelphia, General "Mad Anthony" Wayne rounded up cattle in Salem County and drove them to Trenton, then over to Valley Forge to relieve Washington's starving troops. The British responded to this with a famous massacre in Salem County by cavalry under Col. John Simcoe. So off we go to National Park, originally called Red Bank because of the reddish color of the clay riverbank at that point on the river, to see Fort Mercer. From here we travel to Salem, seeing its sadly dilapidated Colonial buildings, and the oak tree which was already famous among the Indians for its huge size in 1683. Along King's Highway, we pass through Mickleton, Mullica Hill, and Woodstown, three cute little Quaker villages waiting to be overwhelmed as suburbs.

From here we go to Greenwich, named for Connecticut settlers, where Paul Revere stirred up a tea-burning party in sympathy with the Boston event, on his way to promote even greater agitation in Philadelphia. Greenwich is sometimes referred to as a second Williamsburg, but what's here is original, not reconstructed. In passing, this tour takes us past Hancock's Bridge where Simcoe massacred those farmers who sold cattle to Anthony Wayne. That's biased local history speaking; in fact, Tory-Rebel reprisals were very bitter on both sides. Until ten years ago, this blood-stained site stood alone in the lonely moors, but unfortunately, it's pretty much built up and harder to find in the new suburbs than it was in the reeds.

From Greenwich we go on to Cape May, with a brief detour to Bivalve. The point about this stop is the perfectly gigantic pile of oyster shells left over from the days as a center of oyster harvesting. Notice the roads; they're paved with oyster shells. Oysters eat algae, sewage fertilizes algae. Overfishing the oysters caused rotting algae and bacterial overgrowth in the river. The result was depletion of the dissolved oxygen, dead areas for fish, murky water instead of a clear stream. It's an opportunity for oyster farming, but the vast piles of shells at Bivalve are a warning of how far we have to go before we restore the river.

Cape May was the first Atlantic Ocean beach resort, reached from Philadelphia and Tidewater Virginia by boat long before roads were usable. We are told Cape May was originally a separate barrier island, joined to the rest of South Jersey only later. It was once a whaling port, and the Quakers of the region were more related to Nantucket than to Philadelphia. Whale-watching is popular here, but dolphin sightings are more reliably frequent. As you would expect, this cute little place has many fine restaurants and hotels. The hotels are so authentic that strangers share common bathrooms the way they always used to do, so bed and breakfast places can be preferable for snootier tourists. Those whose great-grandparents once stayed in places like the Chalfonte, however, find it important to rough it in traditional summer places. The ocean currents "tumble" the small stones in the beach so beach-walkers can amuse themselves looking for "Cape May Diamonds". Unfortunately, even the locals often have never heard of them, so you are probably on your own. From here, we take the forty-minute ferry ride to Lewes, Delaware.

Cape Henlopen, on the Delaware side of the entrance to the bay, is south but appreciably to the east of Cape May. That means that a line directly west from Cape May points well inside the mouth of the bay, to Slaughter Beach, or Mispillion Point on the Delaware side. The ocean salt water turns to fresh river water at about this level, making for remarkably good fishing at certain times of the year. Furthermore, horseshoe crabs come ashore here on both sides of the bay to lay eggs. Birds who took off from South America months earlier swoop out of the skies to eat the crab eggs on the appointed day. Hawks pause in the woods to fly together in flocks over the bay, based on their own signals. Mispillion Lighthouse is the greatest place on the Atlantic flyway for bird-watching, crab-watching, fishing and nature loving. But you have to know when to go there and remember the best local hotels do get filled up at those times.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

| Camden After the Fall: Decline and Renewal in a Post-Industrial City: Howard Gillette Jr.: ISBN-13: 978-0812219685 | Amazon |

Day Two: Rehoboth to Kennett Square

So, if you want a glimpse of Delaware as it once was before the migrations, get in your car quick and take the tour.  |

Once you step off the Cape May-Lewes Ferry in Delaware, you can still find an occasional old soul who remembers when "the road" was built. The road they mean is the highway that finally connected Southern Delaware to Wilmington. Before 1925, travel between the two ends of that little state was by railroad, or by boat, mostly the Wilson Line. It is natural to suspect the railroad and the boat line might have lobbied against road building, and they certainly had an economic incentive. But there were social factors, too. Although it is a tiny state, Delaware has long been a collection of independent tribes. New Castle County is of course very Ivy League; the Wilmington area claims to have more PhDs than any other American county. Southern Delaware was a slave region, forcing the state to be in favor of the Union, but also in favor of slavery -- a border state. Furthermore, pirate lairs seem to have created a mixed race along the shore calling themselves "Moors"; intermarriage with Indians and/or Portuguese pirates has been speculated as a source of swarthiness. Along the Atlantic coast, it is claimed that pure Elizabethan English is still spoken. Furthermore, the maritime orientation of Lewes created more social affinity to Cape May and Philadelphia than to New Castle and Wilmington. Eastern shore Maryland was even closer. Finally, in 1923, Coleman DuPont gave up on persuasion, built a 98-mile highway from one end of his state to the other at a cost of $50,000 a mile, and just gave it to the state. The legislature at first wouldn't take it, thinking it was clever to let the rich DuPont fellow pay for its upkeep. However, the sight of a DuPont cavalry of highway patrolmen raised even more discomfort, so the legislature reconsidered, accepted the gift.

The legislature was right, in a perverse sort of way, because Wilmington folk promptly poured down to the beaches in the summer, to the duck blinds in the fall, retirees built houses where living was cheaper, southern Delaware children wanted to go North to college, the blonde girls of Swedish or Dutch ancestry went north to become someone's secretary, maybe marry him. The railroad and the boat line went bankrupt, segregation was declared unconstitutional, everybody got television and a pickup. Eventually, someone in the Chamber of Commerce got the idea of jiggering tax laws to encourage out-of-state retail, then banking, then credit cards. The transformation of Delaware into a tax haven brought welcome socio-economic competition to the monolithic Dupont Company, abating the benign hereditary aristocracy that had grown out of it. So, if you want a glimpse of Delaware as it once was before the migrations, get in your car quickly and take the tour. There have even been rumors that the Cape May ferry may close.

|

| Lewes Ferry |

Lewes was once a little seaport, but mostly a home for river pilots. There is a canal across the base of Cape Henlopen peninsula, and the pilots' imposing houses line the canal. But vacationers and sportsmen are now building waterfront houses as fast as they can, so old Lewes is getting lost. Rehoboth down the road has ocean beaches and higher land, so it offers suburban living at the beach, year-round. We don't plan to visit nearby Georgetown on this tour, but it's only ten miles away and presents an interesting legal anachronism in the Court of Chancery, for lawyers and historians to admire.

To take the Delaware turnpike from Lewes to Wilmington is quicker, but history is to be found by winding along Route 9, through the moors, marshes, and farmland. The Wesley Chapel is a place where John Wesley really preached in his tour to extend Anglicanism, and unintentionally to found the Methodist Church. The Bombay wildlife sanctuary is an interesting place to see migrating birds, although the birds may enjoy mosquitoes more than you do. You will be astonished to learn there were once so many peach trees in this area that Delaware was nicknamed the Peach State. Just outside Dover is the Air Force base, which somehow specializes in mortuary affairs during shooting wars. But there are real warplanes there, too, as became very evident during the Cuban Missle crisis. The sky seemed filled with huge eight-engine bombers, just circling around, waiting for orders to go lay an egg or two. The Air Force Base is a peculiarly international community to be living in rural Delaware; a pilot making regular trips to Guam had no difficulty keeping monthly appointments with me for a while.

|

| bomber |

If you watch for directions just south of the airbase, you can travel out in the farm country to the Delaware estate of John Dickinson. As a young man, Dickinson fought a bitter battle in the Pennsylvania Assembly against Benjamin Franklin's efforts to remove the Penn Family from control, and although he lost the King's decision, winning that decision caused Franklin to be essentially banished to England for years as a consequence. Much later, Dickinson swung the critical vote toward Independence by abstaining from voting on the point at the Continental Congress, but wouldn't sign the Declaration. Nevertheless, he volunteered to fight as a private when the British invaded. He started and ended life as a Quaker but was the richest man in the state in between times, was Governor of Pennsylvania and Delaware at the same time, freed his slaves but kept secret the discovery that it actually made his farms more profitable to hire farm workers. A truly remarkable person, living in what you will see were rather plain circumstances.

|

| Winterthur |

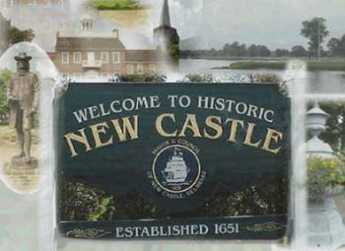

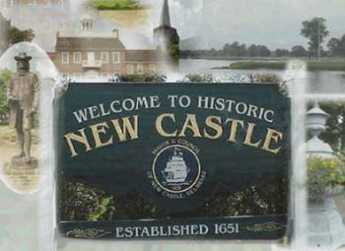

Dover itself is worth a quick trip to the colonial heart of it unless you become engulfed in traffic to the race track. Then a quick visit to the Blackbird pirate sanctuary of the pirate Blackbeard, and on to Odessa and New Castle, which are both real jewels. You can scarcely miss Odessa, which is at the narrowest neck in the Delmarva Peninsula, an isthmus that necessarily must eventually choke up with highways; Odessa has a Christmas festival worth a trip just for it. New Castle is far more uniform in appearance because it burned shortly after the Revolution and was rebuilt in pure Federalist style, then froze in time when the capital moved to Dover.

Then, skirt around Wilmington to the chateau country and try to decide between visiting Winterthur, Longwood Gardens, the Brandywine (Wyeth) Museum, the Brandywine Battlefield, and the mushroom area around Kennett Square. Generally speaking, Winterthur is at the top of the list.

If you left enough time, you may want to circle back through the Main Line suburbs, or through Swarthmore, to Chestnut Hill and Germantown, then down to center city Philadelphia. However, you may be tired, and just want to buzz back from Kennett Square by way of I-95.

Delaware Bay Before the White Man Came

Captain John Smith of Virginia, sometime friend of Pocahontas, wrote a letter to Captain Henry Hudson that he understood there was a big gap in the continent to the North of the Virginia Capes, and maybe this was the Northwest Passage to China. Hudson set out to look for it.

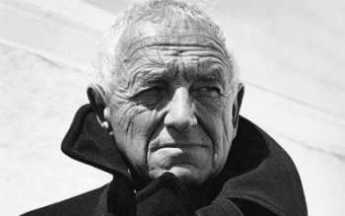

|

| Hudson |

Smith's misjudgment now seems like a credible story if you take the ferry from Lewes, Delaware to Cape May, New Jersey. You are out of sight of land for half an hour on that trip, and it's a hundred miles of blue salt water to Philadelphia if you decided to go in that direction. In fact, the bay widens out to double the width or more, just inside the capes, and you can see how an explorer in a little sailboat might believe there was clear sailing to the Indies if you went that way. But as a matter of fact, Hudson encountered so much "shoal" that he ran aground repeatedly trying to sail into the bay, and soon gave up. He encountered a swamp, not an ocean passage. The Hudson River, and later Hudson's Bay, seemed like better bets.

What Hudson had encountered was one of the largest gaps in the chain of Atlantic barrier islands, formed by the crumbling of the Allegheny Mountains into the sea, and then washed up as beach islands by the ocean currents. At various points, the low flat sandy islands became re-attached to the mainland as the intervening bay silted up, and that's why the islands of New Jersey and Delaware seem like part of the mainland. And that's what would have happened to the whole Delaware Bay if it hadn't been ditched and dredged, and wave action diverted with jetties. The swamp was a great place to breed insects, so fish were abundant, and that brought birds in vast numbers. Two stories illustrate.

|

| Horseshoe Crabs |

Once a year, a zillion ugly Horseshoe Crabs crawl out of the sea onto the Lewes beaches, and lay a million zillion eggs in the sand. Almost to the moment, a swarm of South American birds swoops out of the skies to eat the eggs. Those birds started flying months earlier from thousands of miles away, but their timing with regard to Delaware crab eggs is perfect, so this evolutionary semi-miracle must have been going on for many centuries.

|

| Cape May |

Now, coming from the other direction, every hour each fall it is possible to see a hawk or two flies south to Cape May, then sort of disappearing in the woods. And then, at some unknown signal, tens of thousands of hawks rise from the bushes and travel together on the thirty-mile passage over the bay and then go on South. Cape May has lots of migratory birds and bird watchers, and it also has Cape May "diamonds", which are funny little stones washed up at the tip of Cape May Point.

In the spring, vast schools of successive species of fish migrate up the Delaware Bay to spawn in the reeds along the shoreline, but as each school encounters the point where the salt water turns fresh, they stop dead. They mill around at this point for several weeks adjusting to the change of water and then go on about their business. While they are there, it is possible for amateurs to catch amazing amounts of fish, if you know the best time, and if you know where the salinity changes. Since heavy or light rainfall can shift the salinity barrier fifty miles, you have to own your own boat if you want to enjoy this phenomenon, since the rental boats are all spoken for months in advance. Fishermen don't like to tell you about such things; patients of mine who literally owed me their lives have refused to say where I might find the fish this year.

Over on the New Jersey side of the bay, oysters like to grow, although something has just about wiped them out in recent decades. There is a town called Bivalve, which is worth a visit just to see the towering piles of oyster shells left over from last century. For miles around, the roads are actually paved with ground-up oyster shells. Up north around Salem, the shad used to run by the millions until the warm water emerging from the Salem (nuclear) power plant attracted them into the intake pipes and action was taken to abate the nuisance. The Salem Country Cub is one of the few places where planked shad can be obtained in season. The system is to split the fish open and nail it to a board, which is then placed in the big open fireplace to cook, and sizzle, and smell just wonderful good. On the other hand, if you want to buy shad in season (March-May) and cook it at home, the place to get it is in Bridgeton.

At the far northern end, at Trenton, the real Delaware River flows into the bay. The area has long since been dredged, but at one time the "falls" at Trenton were notable. Even today, if you travel upriver almost to Lambertville, you will see the river drop over several small ledges. Actually, rapids would probably be a better descriptive term, since Delaware picks up quite a strong current coming down from the Lehigh Valley. In seasons of heavy rainfall, the falls can be completely "drowned".

And down at Philadelphia where we live, the Schuylkill joined Delaware, forming the largest swamp of all at the river junction, a place once famous for its enormous swarms of swans. The Dutch discovered a high point of land at what is now called Gray's Ferry and made it into a trading place for beaver skins from the local Indians. There seems no reason to doubt the report that they took away thirty thousand beaver skins a year from this trading post, now the University of Pennsylvania.

An English sailing vessel was once blown to the East side of Delaware at what would now be Walnut Street in Philadelphia, and it was recorded in the ship's log that it was scraped by overhanging tree limbs. The high ground at that point seemed like a favorable place to situate a city because the water was deep enough for ocean vessels. They had stumbled on one of the relatively few places in the whole bay that was both defensible and navigable, where the game was abundant, and fishing was good. The rest is history.

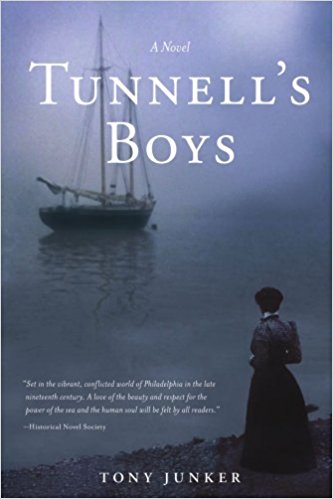

Tony Junker: Tunnell's Boys

|

| Henry Hudson |

When you take the ferry across the mouth of Delaware Bay from Lewes to Cape May, you are out of sight of land for half an hour. But the Army Corps of Engineers have thoroughly dredged it out. By contrast, when Henry Hudson first discovered the river while searching for a Northwest passage to the Indies, it was so full of snags and shoals that he just gave up and sailed on to what is now New York harbor. So, for centuries the river pilots were an essential part of ocean commerce to Philadelphia. As you might well imagine, the earliest pilots were members of local Indian tribes. Eventually, a proud colony of professional pilots grew up at Lewes, Delaware. Since radio communication is a comparatively recent development in this ancient trade, they had to devise ways for an incoming ship to select a pilot, and establish rules to be enforced by the Port Wardens about how to go about it.

|

In the mid-Eighteenth Century, the system was to hang a black ball from the Cape Henlopen lighthouse whenever a ship was sighted. Little companies of ten or fifteen pilots would then jump into very fast schooners designed for the purpose, and race to be first out to the ladder hanging from the incoming ship's side. The rule was, the first to arrive and present his certificate got the job. Tony Junker, an actively practicing Philadelphia architect has immersed himself in tales and adventures among the pilots, and Tunnell's Boys is an exciting new novel about this dangerous, wet and uncomfortable, profession.

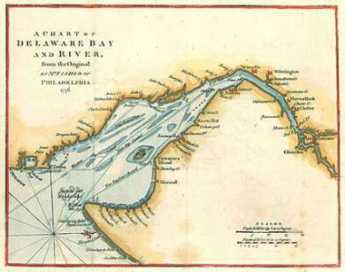

The Philadelphia Bay (1)

It's about sixty miles from Salem, New Jersey where the river takes an abrupt turn to the right, to Trenton, where the river takes an equally abrupt turn to the left. This is the area that could be called the Philadelphia Bay, a protected extension of Delaware Bay. Benjamin Franklin, who sailed down this bay on his many trips to Europe, noticed that it was not exactly a river, because the salt water seemed to invade it, whereas most big rivers have fresh water pushing out to sea. The true Delaware River comes down from the north and empties into Philadelphia Bay at Trenton. We now know that barrier islands begin out at sea every three hundred years or so, gradually move toward the shoreline, and pack themselves against the mainland about three hundred years later. Depending on circumstances, there are usually several sand reefs in various stages of development. Southern New Jersey is made up of a number of barrier islands packed together as they moved toward the mainland of Pennsylvania. The barrier islands actually have packed solid against the Pennsylvania coast, from Trenton to New Brunswick, closing off the ancient northern inlet to the bay. Barnegat Bay is a more recent variant of the same process, running parallel to the more ancient Philadelphia Bay. Since its northern inlet is almost closed at Barnegat Inlet, this seems to be a regular phenomenon of Atlantic barrier island development. Lower Delaware Bay, from Salem to Cape May, appears to have a different history, probably a volcanic split.

|

||

| Joshua Fisher's 1778 Map of Delaware Bay |

In the days of sail, Philadelphia Bay was the main artery of internal commerce. When the Delaware-Chesapeake canal was dug in 1829, it extended the inland waterway from Trenton to Norfolk VA. The earliest commerce took advantage of the tide and the bends in the "river" which was actually just the remnant of ocean between mainland Pennsylvania and the former barrier island of New Jersey. It had tides, but not much in the way of waves. Flatboats filled with Garden State produce would be carried up and across the river by the incoming tide, and down and across the river by the outgoing tide. When ships, particularly steamships, came along, this was the way to carry goods of all sorts up and down the Bay. At Odessa, it's only five miles between the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, so even prior to the old Delaware-Chesapeake Canal sailing commerce was natural from Trenton to Norfolk, Virginia, and all points in between. The next step was building canals, up to the Raritan to New York Bay, and even up the "Main Line" west to Pittsburgh and beyond. The war of 1812 blocked off ocean shipping, and then another canal carried anthracite to Philadelphia, emptying at Bristol, briefly enriching Bristol, but then leaving it reduced to its present vestigial state when the tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad cut it off. After canals came railroad tracks, usually following the path of the canals, making smoke and noise, constructing a dangerous, impenetrable barrier between the land and the water beside it. Superhighways do the same thing, replacing soot with gasoline fumes. There's a river out there somewhere, but you can't get to it. It now takes a twenty story high rise to give you a river view; even that is best seen on Sunday when lessened traffic reduces gasoline haze.

It's really hard to imagine that main attractions to living on the river once included not merely the view and the transportation, but also wonderful fishing and hunting among the bullrushes. Down around the Delaware Chesapeake Canal, Blackbeard the Pirate used to hide his ship and merry men in the shallow marshes among the mud islands. There's a reminder of it as you speed along the elevated multi-lane highway, or maybe it's just another reminder of political correctness. If you know the way well enough to take your eye away from the traffic pattern, off to the right is a directional sign pointing to the little cove where pirates used to convene. It says, "Blackbird".

Jersey

|

| Map of New Jersey |

Once you notice the oddity of salt water in the lower reaches of the Delaware and Hudson rivers, it gets easier to understand the current theory that southern New Jersey was once an island. Like Long Island, it was separated from the mainland by a sound, but in the Jersey case the sound silted up from Trenton to New Brunswick, creating a new peninsula of "West" Jersey by uniting the island with the mainland. The colony was named after the island of Jersey off the coast of England, a gesture for Sir George Carteret, who was given the American area out of gratitude for once sheltering the exiled royal brothers Charles II and James from Cromwell, in that other Jersey. Cape May was probably a second distinct island later joined to the larger one by the transformation of the silted ocean into the bogs of the Maurice River. Cape May started as a whaling community, populated by Quakers from New York and New England, who always maintained a social distance from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. The long Atlantic beaches of New Jersey now repeat the main geological process, with successive generations of barrier islands first heaved up by the ocean and then packed against the mainland, filling up the brackish bay. The cycle of forming and packing successive barrier islands takes about three hundred years before a new one starts. In a larger sense, the process consists of the former mountains of Pennsylvania crumbling into the ocean and then responding to wave action.

It's no mystery, therefore, why southern New Jersey is flat, broken up by turgid meandering streams which casually empty in either direction. The head of Timber Creek, which flows into Delaware, is only eight miles from the head of the Mullica River, flowing toward the ocean. During the Revolutionary War, the British found it too dangerous to sail up these winding creeks, since at any moment they might make a sharp turn and be facing a battery of cannon on the shore. An arrangement quickly grew up that buccaneers would build ships in the center of heavy oak forests and sail them out to Barnegat Bay, thence out one of the inlets of the barrier islands into the blue water. The financiers of Philadelphia, many of them with names now in the Social Register, would come from the rear, sailing up the Delaware River creeks, and walking the last mile or two to privateer headquarters on the Atlantic-flowing creeks. Auctions were conducted, in which the ships were examined, the captain interviewed, and the crew observed in target practice. If you bought a small share you would be rich when the ship returned; and if it never returned, well, you had to invest in a different one. New Jersey is indignant of the opinion that these privateers were mainly responsible for winning the Revolution, but given little credit for it. Many more British sailors were lost to the privateers than soldiers were lost to Washington's troops and the economic loss to Great Britain of the ships and cargoes eventually became serious. Since much of the profit from privateering was recycled into the American war effort by Robert Morris, the British found themselves facing an enemy much more formidable than just the ragged frozen troops at Valley Forge on the Schuylkill. Meanwhile, William Bingham was conducting a similar privateering operation in partnership with Morris but based on the island of Martinique, but that's another story.

In later centuries, the traditions and geography of the Jersey Pine Barrens suited themselves to smuggling and bootlegging during the era of alcohol Prohibition, and even after Repeal, high taxes on liquor kept bootlegging profitable. As late as the 1950s, there were divisions of FBI men prowling the woods of South Jersey, on the lookout for trucks carrying bags of cane sugar, or coils of copper tubing. After housing developments started to invade the forests, the hardball politics of South Jersey reflected a Mafia culture thought more characteristic of South Philadelphia. Near Vineland and Atlantic City, it isn't just a culture, it has the accent, because it also has some of the ancestry.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey, A Historical Account of Place names in the United States: Richard P. McCormick: ISBN-13: 978-0813506623 | Amazon |

Remember This Date: May 18

Delaware Bay is teeming with successive migrations of seafood. May 18 is a pivotal day, give or take a few days.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

A group of Texas and California friends were recently led on a two-day tour around lower Delaware Bay, down the New Jersey side to Cape May, ferry ride to Lewes on the Delaware side of the bay, and then home. The timing of this adventure had more to do with azalea and dogwood season than wildlife, but the date chosen was very fortunate: May 18.

It just happens that May 18 is the last day of the shad season. That's dictated by Mother Nature of course, but it also has a lot to do with Dill's Seafood in Bridgeton. For almost a century, this wholesale seafood store has dominated the shad business in the region. At one time, they shipped six thousand pounds of shad daily in season, although in recent years the business has dropped to five hundred pounds a day. Even today that's a lot of fish, supplying boned shad and roe to every restaurant with shad pretensions for a hundred miles around. They do have a restaurant attached, with pitchers of cold beer on the table, and enthusiasts in great numbers.

The source of this monopoly is a very large family of Italian sisters, who have developed the skill of de-boning shad in about thirty seconds. Shad are just about inedible with the bones intact, and most amateurs make a mess of the matter if they try to de-bone the fish themselves. As the supply has dwindled, few people develop the skill needed to compete with these ladies, and the seafood industry has just surrendered the field to them. Although shad have been successfully transplanted to Oregon, the fish is native to the Atlantic Coast, and my Western visitors had never heard of them. What's really special is to fry or bake the half-pound roe sacs, with bacon of course. Shad roe with bacon and beer, now there's really something to talk about. Shad start to "come in" in January, and the last day of the season, the very last day, is May 18.

We then took a forty-minute ferry ride from Cape May to Lewes Delaware, thirty minutes out of sight of land. The reports in the taprooms of Lewes were that no one had yet seen any horseshoe crabs, it was apparently too early for them. But we had passed the point of no return, so we went on to Slaughter Beach. The origin of the name of this beach is obscure as far as local residents are concerned, although it is fun to remember that these were pirate coves in the Sixteenth Century. Captain Kidd, no less. It is also the place where salt water generally turns fresh, depending on the season and the rainfall, a matter of great importance to migrating fish who tend to hang up here in great abundance.

Well, May 19 turned out to be the first day of the season for horseshoe crabs, so our luck was doubly fulfilled. These terribly ugly brown rascals are about the size of a dinner plate, with a long pointed tail, and they come tumbling in on the surf upside down and sideways. Thousands of them are coming, but on the first day, there was a pair of them every six feet or so. This is the famous limulus, which is really more closely related to scorpions than crabs. The tail doesn't seem to have poison, but it is razor-sharp as my younger son discovered when he picked one up by the tail to throw him (?her?) back into the ocean. He got a deep bloody gash for his reward.

The Limulus isn't edible, but it has its uses. It has four eyes, each attached to a single large nerve fiber, making it very useful for ophthalmology and neurology experiments. Its blood is blue since it uses copper instead of iron in its hemoglobin. That hasn't been put to any use, but the blood has a peculiar ability to clot when it comes in contact with bacterial toxins and has proved very useful for identifying toxic bacteria.

As far as amateurs are concerned, the horseshoe crabs attract a mob of seagulls, but we are assured that these are very special birds who take off from South America months earlier. They are said to arrive almost precisely when the crabs do and love to eat the eggs. One female crab produces twenty to fifty thousand eggs. As you approach the line of feasting birds, the near ones take off but the others remain, so the edge of the flock recedes as fast as you approach it. The vacated beach is peppered with the backs of the half-buried crabs, quite touchingly paired off, two by two. Inevitably, the question is raised how a male tells which one is a female. And inevitably the reply is, "That's his problem."

Where Do Shad Go, When They Aren't Around Here?

|

| BAY OF FUNDY |

Some day, we're going to clean up our rivers, and then maybe the shad will come back. Since every female shad produces a couple hundred thousand eggs a season, when the shad come back, there could be a lot of them. We now know some things George Washington didn't know about shad. For example, they all go to the Bay of Fundy, once a year. All of them, whether they spawn in North Carolina, the Delaware, or the Connecticut River.

By tagging them, it was learned that shad swim at a depth of several hundred feet, apparently seeking a certain amount of darkness, which is in turn related to the growth of algae and plankton, their favorite food. So, when the surviving shad go back down a spawning river to the ocean, they head North in a huge counter-clockwise ocean rotation, adjusting their depth to the degree of darkness. Just about the time summering Philadelphians start packing for Bar Harbor, the shad also reach the Bay of Fundy, which is muddy and dark. Fundy is famous for its unusually high tides, so the turbulent water achieves the shad's desired degree of murkiness at about thirty feet instead of the normally deeper waters of the cyclic migration in the open ocean. People who know about these things say that just about every shad on the East Coast passes through the Bay of Fundy in late spring. In the fall, the fish turn around and start to go South again, maybe following the sun, maybe seeking a desired temperature, or both. Somehow or other, this pattern of migration helps them escape predator sharks and seals, as judged by that wholesome entertainment, the examination of stomach contents. Look out for sharks and seals in the open ocean, but striped bass are the big enemies of fingerlings in the spawning rivers. The Hudson River curiously has lots of striped bass lurking among the abandoned piers, and so does the Chesapeake. The Delaware also has a few stripers around the mouth of the Rancocas Creek; go ahead and fish 'em out.

All of this brings us to a suggestion for our tourist bureau. Shad don't eat much when they are on a spawning run, but they will strike at a lure. That is, you don't use worms, you do fly-casting. If we ever got anything approaching the old shad runs in the Spring, you could expect thousands and thousands of eager fly-casters to flock to the Delaware, filling up our marinas, hotels, restaurants, and cabarets. You wouldn't need to advertise a river teeming with eight-pound action-eager fish; the news would spread like magic. The best proof of this claim can be found on the only river on the East Coast which continues to have a classic shad run. The existence of this river was told to me as a sworn secret, but the invitation to try it was given with the assurance that "every single cast results in a strike".

And here's the zinger. Except for that one secret stream, the Delaware is the only major river on the East Coast that doesn't have a dam between the ocean and the spawning grounds. Once these fish have picked a river, they keep coming back to it, forsaking all others. The situation positively cries out for Federal assistance, and the lure-casting fishermen of America demand no less. Presidential elections have been won and lost on less important issues than this one. But just one dedicated congressman could do it, particularly if he sits on the Committee on Fisheries. Bring back our shad and get rewarded with lifetime incumbency that even Gerrymandering can't dislodge.

Founding Fish

|

| Potomac |

In 2002, John McPhee brought out a perfectly splendid book about fish and fishing history in this region, with particular emphasis on shad. He makes the whole topic remarkably interesting, but you have to be a little wistful about the way he demolished a splendid story of fish in Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War. The book is called The Founding Fish.

As everyone knows, George Washington and the Continental Army were starving and freezing at Valley Forge, a few miles up the Schuylkill, while Major Andre and the other British officers were cavorting downtown with the Tory ladies, grr. The story has long been told that things got to a desperate state at Valley Forge when, lo, the annual shad run was several weeks early and mountains of fish came roaring up the river to the excited shouts of the starving patriots and rescued the raggedy starving Continental Army. It would make a wonderful scene in a movie.

McPhee tells us that George Washington was in fact a shady merchant, having caught and pickled many barrels of shad coming up the Potomac River. The annual shad excitement was no news to him, and it seems quite possible he selected the campsite at Valley Forge with this spring event in mind. Shad was no news to the British, either; there are records of their trying to block off the Schuylkill with nets to prevent the fish from getting upriver to Valley Forge.

Unfortunately, a careful search of letters and records fails to record any shad run earlier than April that year. The rescue of song and story does not appear in contemporary documents. What's more, some unnecessarily diligent scholars have sifted through the garbage heaps of the encampment area, and have only found pig and sheep bones, no shad bones.

Those graduate students undoubtedly deserve to be awarded degrees for their work, especially the digging in garbage part. But nevertheless, it all does seem a pity to ruin a good story that way.

Georgetown Oyster Eat: Separate but Equal

|

| Oyster Knife |

It's a source of some regret never to have attended the Georgetown Oyster Eat. It occurs in the middle of February when the days are dark and short, and the weather is uncertain for driving.

Local citizens of Sussex County, Delaware, report no one alive remembers when or how the custom began. In the nature of such things, a certain amount of historical inaccuracy is thus to be expected. It certainly did start out as an all-male event, taking place in the firehouse. One inflexible requirement is that a participant must bring his own oyster knife, which is a very heavy chunk of iron with a short blade attached, sort of like a screwdriver. The ones I have seen are all one piece of iron, suggesting they have been hammered out in a blacksmith shop. The flattened-out blade serves as an eating utensil, as well as a wedge to pry open the oyster shell. The oysters are eaten raw and whole, often with some sort of condiment, like horseradish sauce. Some eaters favor a whole lot of ground pepper, and various other ancient remedies are said to make an appearance. The main beverage is beer, lots of beer.

Beyond that, not much is known or divulged to the public, although a party attended by nearly a thousand tipsy people can't keep very many secrets. Before the party, the windows of the firehouse are covered with brown wrapping paper, sealed with tape. Kegs of oysters and kegs of beer are rolled into the firehouse before other things get rolling, and a lot of loud noises and laughter emerge almost all night. The sponsors claim to bring a thousand bushels of oysters to each party, although it is hard to imagine very many people eating their quota of a bushel apiece. The per-person beer consumption is a statistic kept confidential. The ladies of the neighborhood report numerous husbands eventually returning home, with their glasses broken, and suspicious red bruises on their faces. Aside from that, nobody knows nothing'.

About ten or fifteen years ago, feminism reached the Delmarva Peninsula, and the ladies started their own brawl. Renting the Grange Hall and brown-papering the windows, they make a lot of noise come out all night. Because of some sort of oyster virus, oysters are not nearly so plentiful any more. There's a more elaborate accusation that excessive fertilizer on the farm fields runs off and stimulates a bloom of algae, which depletes the oxygen of the river and kills a lot more than oysters. Anyway, the oysters are in short supply. If the local firehouse custom dies out, it won't be from lack of enthusiasm, however.

Georgetown Returns Day

|

| Georgetown |

Early in November, two days after each election, Georgetown Delaware puts on a festival called Returns Day. About two hundred years ago, there was a law that all ballots had to be cast in person at the courthouse in the county seat (Lewes, at that time), and it took two days to count the votes. Everyone, candidates included, would hang around at the courthouse to learn who had won. After a few elections, except in wartime when the ceremony was temporarily skipped, the popular tradition has continued even though of course the election results are known much earlier. Although the function of revealing election results has yielded to the news media, the ceremony has assumed importance for its own sake. Unless it rains pretty hard, the parade lasts three hours, with ten or twelve marching bands, and local amateurs struggling with bagpipes. The candidates, winner, and loser, ride gamely around the square in horse-drawn carriages. You can imagine what would happen to the political future of any candidate who declined to participate in what is now a mandatory public entertainment.

|

| U.S. Senator from Delaware |

Two features of this festival are especially notable. There is a hatchet-throwing contest, trying to get the flying hatchet to catch one corner in a post. It's not an easy thing to do. And then there is hatchet-burying, which is said to date back to the Nanticoke Indians. The traditional hatchet is brought from Lewes, as is the sand. This is all said to be the origin of the folk-saying about burying the hatchet, and it's really very heart-warming to believe the election is only an election, and the competition is over. It's probably not entirely true, of course, but it symbolizes what the public wants to believe is true. And what the public is telling politicians -- had soon better become true, again.

Delaware's Court of Chancery

|

| Chancery |

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble.

Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries.

Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

|

| George Read |

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy.

Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision.

But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Chancery's jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law. It sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law.  |

| A. H. Manchester Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 (1980) |

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude:

"The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue."

That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril.

John Dickinson, Quaker Hamlet

|

| John Dickinson |

John Dickinson (1732-1808) would probably be better known if his abilities were less complex and numerous. It would have been particularly helpful if he had consistently remained on only one side of the important issues of his day. Born in a Quaker family and buried in a Quaker graveyard, he was for years a notable Episcopalian and soldier. He outwitted John Penn, the Pennsylvania Proprietor who was trying to keep Pennsylvania from sending representatives to the Continental Congress, by having the Pennsylvania representatives hold a meeting in the same small room of Carpenters Hall at the same time as the Congress. But he ultimately refused to sign the Declaration of Independence. Although he was the main author of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution which replaced it would not have been ratified without his idea of a bicameral Congress. Although he was Governor of Pennsylvania, he was also Governor of Delaware, has been the central figure in the separation of the two states. In fact, for fifteen years he was a member of the Legislature of both states. Dickinson seems in retrospect to have been on every side of every argument, but he was immensely respected in his time.

Two events seem to have been central in the organization of his life. The first was his education as a lawyer. At that time and for a century afterward, lawyers were trained by apprenticeship. Dickinson, however, studied in London at the Inns of Court for four years and was by far the most distinguished lawyer in North America for the rest of his life. Furthermore, he absorbed the principles of the Magna Carta and the approaches of Francis Bacon so thoroughly that he never quite got over his pride in his English heritage. Throughout his leadership of the colonial rebellion, he acted as a better Englishman than the English themselves. His demand was for American representation in the British Parliament, not independence from England. It would not be hard to imagine Dickinson standing before a firing squad, gritting the words of St. Paul, Civis Romani Sum.

His other pivotal experience was the Battle of Brandywine. Dickinson had been the organizer or chairman of the two main Pennsylvania military organizations, the Pennsylvania Committee of Safety and Defense, and the so-called Associators (today's 111th Infantry, the first battalion of troops in Philadelphia). Both of these particular names were a characteristic gesture to conciliating pacifist Quaker feelings. Nevertheless, when Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration, he did temporarily become so unpopular he resigned his military commands. A few months later, when General Howe landed at Elkton at the narrow neck of the Delmarva peninsula, Dickinson enlisted as a common soldier to defend the southern perimeter of the defense line Washington had hastily thrown up to defend Philadelphia. Shortly afterward, Dickinson's friend and neighbor Caesar Rodney made him a Brigadier General in charge of the garrison around Elizabeth New Jersey, but the Battle of Brandywine taught an important lesson. Little states like Delaware and Maryland could not possibly defend themselves witho

A Pennsylvania Farmer in Delaware

|

| John Dickinson |

It is difficult to have a coherent view of the mind of John Dickinson. Seriously offended by the Townshend Acts, he rightly perceived them to be the work of a few malignant personalities in British high places who would mostly soon be replaced. Later on, he refused to be troubled by the inconsequential Tea Act, which he appraised as a face-saving gesture of reconciliation, but more recent historical information demonstrates was more likely aimed at avoiding an unrelated vote of no-confidence in Parliament. Unfortunately, Dickinson was too remote from these events and additionally could not comprehend reckless hotheads among his own neighbors. Reckless hotheads in turn seldom comprehend the measured meekness of Quakers. In any event, although Dickinson played a major role in the Declaration of Independence, he refused to sign it when the time came, evidently sensing an opportunity to separate the three lower counties from Pennsylvania and its Proprietors. A few months later when the British actually invaded the new State of Delaware on the way to capturing Philadelphia by way of Chesapeake Bay, Dickinson enlisted as a common soldier and fought at the Battle of Brandywine. Obviously, he was seriously conflicted.

|

| John Dickinson's Farmhouse |

Dickinson had become internationally famous for twelve letters he had meant to publish anonymously. The Letters From a Pennsylvania Farmer were written about 1768 out of resistance to the Townshend Acts. Because the three counties which were to become the State of Delaware were then still part of Pennsylvania, many school children have become understandably confused about the actual location of the man who became governor of both states, simultaneously.

The causes of the separation of the two colonies are still a little vague. Delaware schoolchildren are taught the two states separated, but often report they didn't retain much information about why it happened. The Dutch and Swedes who originally settled southern Delaware were not sympathetic with Quaker rule, which could be seen as a reaction to their living here for generations as Dutchmen before William Penn arrived, but then saw the colony sold out from under them. As a further conjecture, there might have been friction with the Quakers over slavery, similar to the hostility of other Dutch settlers in northern New Jersey when William Penn purchased that area. This pro-slavery attitude resurfaced in both areas during the Civil War. One alternative theory which has considerable currency in Delaware is local dissension about Quaker pacifism during the Revolutionary War. On a recent visit to Dickinson's home outside Dover, a school teacher was overheard to instruct his flock that the Dutch Delawarians wanted to fight the British King, but the Quakers wouldn't give them guns. "We value peace above our own safety," was the unsatisfying response they received from the Pennsylvania Assembly. But that line of reasoning bumps up against Dickinson's role in local affairs, his ambiguity over the Declaration, and his vacillation in warfare. One would suppose the simultaneous Governor of both states would play a major role in the separation of the two.

|

| over Air Force Base |

Dickinson's plantation, quite elaborately restored and displayed, is tucked behind the Dover Air Force Base. Perhaps all that aircraft noise will discourage sub-development in the area of Dickinson's plantation and the rural atmosphere may persist for years. At the time of the Cuban missile crisis, your correspondent happened to be driving past, observing the sky filled with bombers, just circling and circling until the diplomats settled matters. Since eight-engine bombers are seldom seen around Dover, it has always been my presumption that they came from elsewhere to be refueled at Dover; but that's just a presumption. One of the pilots later told me he was carrying nuclear "eggs" and was completely prepared to take a long trip to deliver them.

To get back to Dickinson's wavering about the Declaration, maybe there was a good reason to waver. Joseph J. Ellis (in His Excellency, George Washington) relates that after the devastating British defeat at the Battle of Saratoga, Lord North made an offer to settle the war on American terms. In a proposal patterned after the concepts of the separatists in Ireland, America could have its own parliament as long as it maintained trade relationships with England. As an opening offer, that comes pretty close to what the colonists had been demanding. Governor Morris was active in disdaining this offer, although it is unclear whether he was acting alone or as the agent of others. The offer came too late to be accepted, but it might have shortened the war by six years, and we might now have a picture of the Queen on our postage stamps.

REFERENCES

| His Excellency: George Washington: Joseph J. Ellis: ISBN-13: 978-1400032532 | Amazon |

| Letters From A Farmer In Pennsylvania To The Inhabitants Of The British Colonies (1903): John Dickinson: ISBN-13: 978-1163969533 | Amazon |

Delaware Declares Independence ... From Pennsylvania

|

| Delaware Map |

To bewilder your friends from the State of Delaware, just ask them when and why Delaware broke off from Pennsylvania; chances are they haven't the foggiest answer. But they will recognize it is a legitimate question. Everyone does know that Delaware was once owned by William Penn and was part of Pennsylvania. It was generally referred to as the three Lower Counties. But what happened then doesn't seem to be taught very effectively in the Delaware schools, and not much is written about it.

Not much is written because not much happened. No revolutions, bombings, hangings or even acrimonious debate; just think how much Serbia, Russia, China, Sudan and a lot of other countries have to learn about self-determination, from Delaware.

The history of Delaware up to 1674 was of Dutch, Swedish and even some Finnish settlement and arguments; doesn't count. The Duke of York (later James II) owned it and seems brief to have toyed with combining it with New York; that's how Delaware happens once to have been called the South River, and the Hudson the North River. But William Penn acquired it in 1682, mostly with the motive of having unchallenged access to the ocean from Pennsylvania. Apparently, the people who lived away from the river felt more kinship with Maryland, and expressed unwillingness to be linked with some religious experiment in Philadelphia, especially if they had to travel there to settle their affairs. There is not much Catholicism in Delaware at present, but that seems to have been part of the uneasiness in 1701. So Penn granted them quasi-autonomy and their own separate assembly, which resulted in a peaceful enough arrangement until the American Revolution. Penn got all he wanted, which was to sell off the land and maintain a clear river passage, and by the time of the Revolution, his descendants had lost all control of things. The control of Pennsylvania over its three lower counties had never been terribly firm, and during the eight-year Revolutionary chaos, it sort of drifted away. When its votes were needed for the Declaration of Independence and later for the Constitution, it was expedient to recognize Delaware's claims.

That's perhaps all there is to this vague story of statehood building, except for one nagging doubt. Delaware was a plantation state and a slave state. It's sided with the North during the Civil War, but it remained a slave state. It voted against Lincoln's Emancipation overtures, and refused to ratify the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments until 1901. Until the Lewes-Cape May ferries got busy with Garden State Parkway traffic, lower Delaware's population was almost exclusively either African-American or many-generation English descendants. The hospitals had white-only and black-only restrooms until the Second World War. Nothing better illustrates that the Civil War was primarily fought to defend the Union, rather than to eliminate slavery, than the tangled local history of the border states, of which Delaware was definitely one.

And so, you have to wonder. Is it possible that the residents of the Lower Counties in 1776, especially in the southern portion where John Dickinson had a plantation, could recognize that the Quakers of Pennsylvania were relentlessly moving in a direction which surely would eventually conflict with the slave system? Maybe, looking ahead, the chaos of Revolutionary times provided a plausible moment to make a clean separation. These are awkward questions to ask, perhaps best passed by, in silence.

Pirate Lair

|

| Jolly Roger Flag |

Delaware takes a ninety-degree turn right at about the place where the Salem nuclear cooling towers are visible on the Jersey shore, and great quantities of silt have piled up in the river there, making marshes and swamps. There is a rumor that Captain Kidd tied up among these marshy islands, and much better evidence that Blackbeard the Pirate used the Delaware marshes as a hideout. Since a high-speed highway, with limited access, now rushes visitors to the slot machines of Dover and the beaches of Lewes, no one much notices that this area hasn't changed much from what it probably looked like three hundred years ago.

But if you take the old road, Delaware Route 9, you wander through the backcountry and are only likely to meet duck hunters. At one point, with a lake to one side and the river on the other, a watchtower has been erected for bird watchers and the like. It's very beautiful there, and quiet.

So one day I drove up, parked my car at the base of the tower, and climbed a hundred steps to the top. Blackbeard was not in evidence, but it was easy to see how he might feel pretty secluded in the coves and behind the trees. There were lots and lots of birds, interesting enough but mostly unidentifiable by me. Like most big-city lovers of the environment, I mostly classify birds as little brown jobs (LBJ) and big black buggers (BBB). And then a car drove up, with some chattering teenagers.

|

| Copperhead |

From a hundred feet up, it was hard to tell what they were saying, and it probably didn't matter much. Until suddenly one of the girls screeched out, "Oh look! There's a big snake under that man's car! "

One of the boys in the car shouted out, "That's a copperhead snake! I've never seen one so big!"

And so, they roared off into the distance, leaving the marshy paradise to me and the snake. What do I do now?

I waited, hoping the snake would go away. But it started to get dark, and now it was even more unattractive to chase around with snakes. So, creeping to the bottom of the stairs, I made a dash for the car door, jumped in, and slammed it tight.

As I drove away, I could not see any snake on the ground under the place where I had parked. To this day, I don't know if there really was a snake there or not.

Odessa, Delaware

Delaware is a pretty small state to be divided into two civilizations, and in fact, it seems safe to predict that division will soon become meaningless. New Castle County and Wilmington are up north in DuPont country, with more Ph.D.'s than anywhere else in America, chateaux in the suburbs, plenty of Porsche's and other elements of the finer life. The other two counties, "South of the Canal," are rural, marshy, or beach front. Wal-Mart country. Aside from a distinct difference in the weather patterns, all of this is destined to change, and soon. A limited-access toll road, probably mostly intended to carry people to the slot machines of Dover Downs, makes it breezily simple to go from one end of the state to the other in an hour. A ferry from Cape May to Cape Henlopen makes sailing across the mouth of the bay a shorter simpler way to go from the urban areas of New York to and from Washington, Norfolk and points South. And changes in the tax laws make Delaware a great place to avoid sales taxes, estate taxes, business taxes, usury laws and lots of other things. That brings in businesses, and they, in turn, will bring in a swarm of home builders. It looks very likely Delaware will go the way of Luxembourg, urbanized from border to border.

|

|

The Corbit-Sharp House Built in 1774 Located in Odessa, Delaware. |

Little Odessa (population 280) sits right at the pivotal point in this transformation. Here is the very narrowest point of the peninsula between Delaware and the Chesapeake bays. In the Seventeenth Century, there was only a five-mile portage from the head of one creek to the head of the other; the town there was called Cantwell's Bridge. Just why the two Delaware-Chesapeake canals were built a few miles further North is an engineering question, but they tended to shelter Cantwell's Bridge from Northern influences. The neck was so narrow, however, that the road couldn't avoid the town, and for a century it was a pleasure to find a little Colonial town, a little Williamsburg so to speak, popping up among the fields of clover bordering a drive to Dover. A few miles to the West, a very fine boy's boarding school adds to the tone of the place, and it's only a short 9-mile commute to the University of Delaware. The finest 18th Century country house, the Corbit-Sharp House sets the tone for the area, and Christmas season in Odessa is quite memorable. Rodney Sharp was the son of the local school teacher who acquired financial substance, private jet airplanes and all that, on the other side of the canal, and then restored his old home the Corbit house into the Corbit Mansion, bringing the whole farm village up to an elegant level. A visit to Odessa at Christmas, touring the open houses and visiting the festivities, is well worth the trip.

You have to hold your breath to see what is going to happen to real estate in the area. The toll road sweeps around the edge of Odessa, and now the people going to the slot machines and the beaches can hardly see it as they race past. But that's mostly weekend traffic, and during the week all of those cornfields are quickly turning into easy commuter villages, full of McMansions. They are going to fill up the schools, demand better ones, demand traffic signals to protect the kiddies, demand retail outlets for all those upscale stores with catalogers, demand to be noticed. Eventually, all those three-car families will choke up the toll-road, and it will become a great big congested parking lot at rush hour. Sad.

One final comment about the origin of Odessa. It's named after the city in Russia because both of them were wheat exporting cities at one time, although it is doubtful if they were ever comparable in the steamy nightlife. However, the one in Delaware is actually the older of the two. Cantwell's Bridge, Delaware was founded in 1731. For reasons unclear, its name was changed to Odessa in 1845, perhaps in the mistaken idea that the Russian city was where Odysseus once landed. That's what many Russians claim, but the place they have in mind was really in Bulgaria. The place the Russians call Odessa was founded by Catherine the Great in 1794, some sixty years after Cantwell began collecting toll at his bridge in Delaware. When the Bulgarian mistake was pointed out to Catherine the Great, she wouldn't change the name; she sort of liked it that way.

Pea Patch Island

|

| Fort Delaware |

There's a tradition that a boatload of peas ran aground on the mudflats of Delaware Bay near Salem in the Sixteenth Century, turning the flats into a patch of peas. In any event, the island is known to have been growing in size for centuries, and now is home to about 12,000 families of Herons. The number of mosquito families has not been accurately counted as yet, but they are even more numerous. The island doubled in size when the Army Corps of Engineers built the present Fort Delaware on it in 1847-59.

The War of 1812, which included the burning of Washington DC and bombardment of Baltimore, propelled America into a frenzy of coastal defense, and the first fortification of Pea Patch Island took place in 1813. A plan was adopted by Congress in 1816 to build 200 coastal forts, and about forty of them were actually completed by the time of the Civil War. These forts all had a similar appearance; the most notable example of the style was at Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina, which was nearly complete by the time of its famous bombardment. In fact, it was first hastily occupied by Northern defenders arriving just in time to be evicted. In essence, these forts were huge walls of bricks with a concrete outer shell, holding a couple dozen very large cannons and a parade ground.

The new river defenses of Philadelphia were to be provided by three forts, Fort DuPont at the mouth of the old Delaware-Chesapeake canal, Fort Delaware on the island, and Fort Mott on the New Jersey side. You can now take a ferry ride to all three, between April and September; it's a pleasant afternoon excursion. Not so many years ago, you had to go into an ominous little taproom in Delaware City and ask in a loud voice if someone wanted to take you to Pea Patch in a fishing boat. The scene was reminiscent of old movies about derelicts hanging out in Key West, complete with George Raft and Ernest Hemingway, but now the National Park Service has given it the characteristic NPS spruce-up, with pamphlets and restrooms.

The place never had any serious military activity except when it was used to house Confederate prisoners after the Battle of Gettysburg. Over 12,000 prisoners were brought there, and there were about 3000 deaths among them. Historians have compared the treatment of Confederate prisoners with the treatment of Union prisoners at Andersonville, Georgia, and it would be hard to say which place was worse. There are certain diseases of poor sanitation, like typhoid, cholera, amoebic and bacillary dysentery, and hepatitis, which decimate all concentration camps at all times. And adding to them the mosquito-borne diseases of both Delaware and Georgia at the time, you don't really need to assert prisoner mistreatment to account for the morbidity and mortality. Undoubtedly there was some of that.

Elizabethan Accents in Philadelphia

|

| William Shakespeare |

The following is nearly verbatim recounting of a conversation which took place in Philadelphia, between two Philadelphians, in the year 2006, Elizabeth II reigning. The scene is the dressing room for the basement exercise area of a private club. There are about forty stalls for members to hang up their clothes before going into the gym. Although clothes are usually seen hanging in no more than three or four stalls, on this particular day there was only one empty stall, at the far end of the long corridor.

FIRST STRANGER: Well, we certainly have a lot of athletes in the club, today.

SECOND STRANGER: You're very generous with that description of our members.

FIRST STRANGER: Perhaps I ought to call them athlete-wannabees.

SECOND STRANGER: Yes, that's apt.

(Exeunt)

Shakespeare would have expressed it a little better, but anyone can recognize in this little exchange, the elements of those short interlude scenes in Shakespearean plays. The bit players create brief background while the stagehands shift scenery between major acts. Nobody actually has an Elizabethan accent these days, but in Quaker and Upper-Crust Philadelphia circles, the Elizabethan manner of speaking pops out at odd moments, as a coded way of asking strangers, "Are you a native Philadelphian? You sort of look like one." If the stranger doesn't seem to grasp the idea, well, let it pass.

|

| Elizabeth I |

In the more remote sections of the Delmarva peninsula, it is claimed the natives often do speak in a pure Elizabethan accent. Somehow I am dubious of that, having listened for it over sixty years of travel in those regions. Rural Delaware talks with a softened version of a Southern accent, even softer than you hear in Tidewater Virginia. It's hard to believe that Marlowe and Shakespeare talked like that. But go into a roadside coffee shop and listen to the truck drivers joshing the waitress; it's not an accent but an Elizabethan manner of address that's recognizable. They self-consciously stop talking that way when obvious strangers come into the shop.

Because of Dr. Samuel Johnson's dictionary, Shakespearean adjectives pepper English speech in all regions of the world. Johnson was a theater critic in his early days, so when he needed familiar quotations to illustrate the words in his dictionary, he drew heavily from Shakespeare. William Shakespeare's tendency to invent likely vocabulary was thus enshrined by Johnson's dictionary as

New Castle, Delaware