3 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Tourist Walk in Olde Philadelphia

Colonial Philadelphia can be seen in a hard day's walk, if you stick to the center of town.

Philadelphians are a trifle irked that most visitors to the city don't even stay overnight, reflecting the unspoken belief that everything worth seeing is clustered around the Liberty Bell. That's like saying you have seen London if you see Big Ben on Westminster, or that the Empire State Building is all there is to New York. Grr.

On the other hand, you haven't seen anything at all unless you do see Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and the old Eighteenth Century buildings in Society Hill. We've here put together a walking tour of the Olde Towne, intending to show the most notable attractions in the shortest possible route. It will take all day, and your feet will be sore by the time you are done. But at least you will have seen -- and possibly photographed -- the real essence of the place the founding fathers saw, in one day's brisk walk.

If you are from out of town, you will have to park the car and ransom it at the end of the day. The new Constitution Center has a convenient underground garage with an entrance on Race Street between 6th and 5th. That's near a cluster of outdoor parking lots which may or may not be cheaper. If you are a local person, this tour assumes you came by public transportation and will go home the same way. For example, come in from New Jersey by PATCO the high-speed line to 8th and Market Streets, then walk to the Visitor's Center on the Northeast corner of 6th and Market. Or else come in from the suburbs by SEPTA the suburban rail line network, and get off at 11th and Market Streets. Or by the Frankford elevated from North Philadelphia to 8th and Market, or from West Philadelphia by the same line coming to the same stop. If it's raining or you don't mind a little nuisance of an extra transfer, there is a stop on the Frankford/Market Street line at 5th/6th and Market right in front of the visitor's center.

Regardless of how you get there, start at the Visitor's Center at 6th and Market, across Market Street from the restored house where George Washington lived when he was President. The Visitor Center has a gift shop, lunch room, toilets, and a few meeting rooms; mostly, it is a place for visitors to stay out of the rain, but there are several brief video shows with the sort of meticulous accuracy you expect from the National Park Service. As you go by the corner of 6th and Arch, notice the place where John and Ethel and all those other Barrymores used to live.

I'm afraid there is an entrance fee to the Constitution Center at Sixth and Arch, and photography is limited to the hall of statues of signers. That's worth a fee if you are a serious photographer, otherwise perhaps not. The hourly show in the rotunda is a little overdramatic but it gets you started on the 1787 events which took place two blocks South of here. If you are really serious about chronological history, the important events of the nation's founding began at Carpenters' Hall at 3rd and Chestnut Streets, in 1775, migrating to Independence Hall at 6th and Chestnut in 1776. Our tour is less chronological, but saves you steps if you want to see it all in one visit. If you want accuracy, ask a Park Service employee; the tourist vendors of carriage rides, etc. are less uniformly dependable.

Overnight in Philadelphia: Tourism Suggestions

|

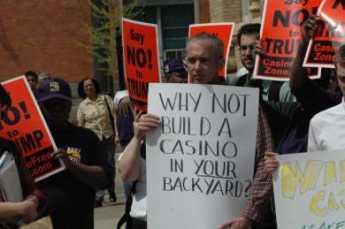

| NO CASINOS |

Tax-hungry Pennsylvania government has voted to allow two gambling casinos to be built on the Delaware River, near the historic district. A lot of angry people declare that must never happen, and it surely will not happen much before 2012. For the time being, and we hope longer than that, the oldest and most historic part of Philadelphia will exist as a quiet little nook fifteen blocks from the business center, with quite a choice of very pleasant, moderately priced hotels and bed-and-breakfasts. In the midst of this, at 2nd and Walnut, is a very large parking facility, with even more parking space available within a couple of blocks. For reference, let's call the site of William Penn's own home the epicenter of all this. It's now called the Welcome Park at South 2nd Street. The ship which brought Governor Penn to his land holdings was called the Welcome. Anyone who can prove descent from those who were on the ship is eligible to be a member of the Welcome Society.

|

| Welcome Park |

Welcome Park is across 2nd Street from a restoration of City Tavern, which only serves meals (in authentic period dress) but at one time was the place where the delegates to the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention stayed overnight. And of course, did lots of negotiation at night over a cold beer. It's also next to the famous Old Original Bookbinder's restaurant which unfortunately is out of business we hope temporarily because of ill-timed overexpansion by the former owner. It's a very large restaurant which used to be able to obtain four-pound lobsters and bake them for tourists. If legalized gambling does make an appearance, the winners are likely to frequent this spot, unless the new owner continues the former tradition of hiring the only truly surly waiters in our otherwise friendly town.

|

| Dr. Thomas Bond House |

A hundred feet away is a quiet upscale Sheraton, much favored by Society Hill residents. Over a footbridge is a Hyatt, next to the marina on the river, and favored as a hangout by the younger sports in the area. There are at least three charming bed-and-breakfasts along the block, of which the favorite is a 12-room hotel directly facing on Welcome Park. It is the former home of Dr. Thomas Bond, who founded the Pennsylvania Hospital with Ben Franklin's help. Not only did Dr. Bond found the Nation's first hospital, but he also started the tradition among American physicians of not charging for their services to the poor. Without that sort of leadership, the hospitals could never have survived their early years.

|

| Seaport Museum |

So, here is where to begin your tour if you are from out of town. A big garage to store your car, right next to several choices of quiet but moderately priced hotels, and a couple of dozen restaurants. This is a great place to branch out to the historic district, or Society Hill, or the seaport museums and marinas. And maybe some gambling casinos, although it is hard to imagine much tolerance between that group and the history lovers.

By the way, Philadelphia hotels are like hotels everywhere else in one respect. If you forget to make a reservation in advance, just breezing in looking for a room for tonight, you must expect to find the price is nearly doubled.

Sixth and Arch to Second and Arch

When the large meeting house at Fourth and Arch was built, many Quakers moved their houses to the area. At that time, "North of Market" implied the Quaker region of town.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

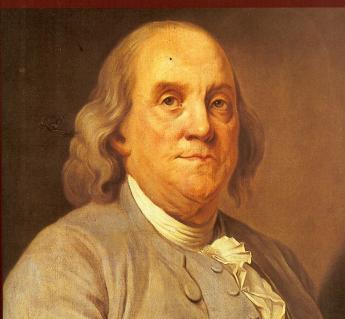

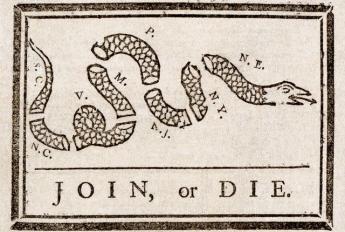

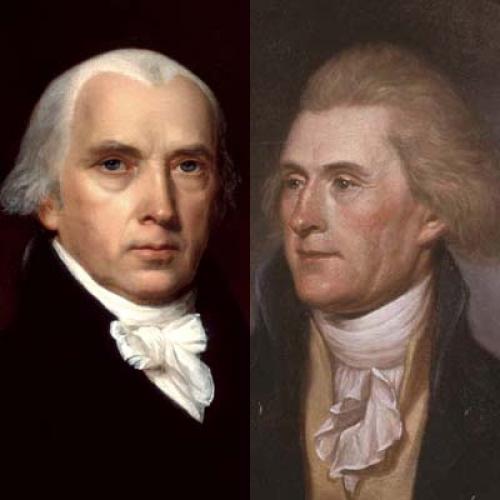

During a recent speech, Senator Arlen Specter let it slip that he had a lot to do with obtaining federal financing to establish the new Constitution Center on the north end of Independence Mall. Probably even more important, he intimated that his wife, Joan Specter, did a lot of domestic agitating to see that it happened. The earmarks were his, the fingerprints were hers. Some have worried that the Supreme Court might be uneasy about a center telling the world what the Constitution is because the Justices see Constitutional interpretation as their unique function. The point that is sensitive is the emphasis on the words "We, the People", which could be seen as urging easy modification of the document by shouting demands or repetition of certitudes without passing due process in order to be considered. The second floor of this enormous new building is devoted to some very skillful exhibits relating to the history and significance of certain features of Constitutional history. The many auditoriums are the site of public lectures and programs, and there is a very interesting set of life-sized bronze figures of every member of the original Constitutional Convention. A striking feature of the display is to show how short and inconsequential Hamilton and Madison seemed to be in person, while Ben Franklin and Gouverneur Morris appear imposing and formidable in the flesh. These things matter in politics.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

Cross Arch Street to the Free Quaker Meeting House, and if you have called the Park Service in advance, perhaps you can visit, noting how visually dramatic design of drastic simplicity can be. Just across Fifth Street is Ben Franklin's gravesite, in Christ Church cemetery, extended to this location when the gravesites became full around the church itself.

|

| Ben Franklin Bridge |

Going down Arch Street from Fifth to Fourth, you can visit the orthodox pacifist Meeting House, it's interior largely unpainted and grimly plain -- quite different from the effect of pristine simplicity of the Free Quakers. If you go inside the meetinghouse, a quiet and unprepossessing Quaker will be more than happy to give you a magnificently short and simple explanation of what Quakerism is all about. In passing down Arch Street, glance at the warehouses on the left, covering the site of what was once a major factory for shoes and uniforms for Union soldiers in the Civil War. Behind the buildings on the North side of the street, as the ground slopes sharply toward the river, you can sense the rough, tough waterfront of the Eighteenth Century. Charles Dickens might have felt entirely at home in the Nineteenth Century. Looking three blocks further North on Fifth Street, you can see St. George's Church, the oldest Methodist Church in the world, its view unfortunately obscured by the approaches to Ben Franklin Bridge.

|

| Elfreth's Alley |

Continue down Arch Street, past the building once said to have been the house of Betsy Ross, turning a half-block to the left on Second Street to the head of Elfreth's Alley. For full effect, continue down the alley to the end, but you will eventually have to retrace your steps because of rearrangements of the streets. Going down Elfreth's Alley, observe how tiny the Colonial buildings are. That's a reminder that placing taxes disproportionately on land will result in small residential plots, even though a whole continent of vacant land stretches to the Pacific. At one time, you might have walked south on Front Street, to Market, and then right to Second and Market. However, the embankment of the Interstate highway blocks you so you have to retrace your steps to Second Street. At the corner of Second and Market, however, do not neglect to look back toward the Southwest corner of Front and Market. The original building has unfortunately been demolished, but here was the site of the London Coffeehouse, where it could be fairly argued the American Revolution began. The owner, John Bradford, first learned of the Tea Act from a sailor at the Arch Street Wharf and fiercely resolved to stir up trouble about it. In retrospect, the Revolution might have seemed justified, but the Tea Act itself was intended by the British to be conciliatory, actually lowering the price of tea.

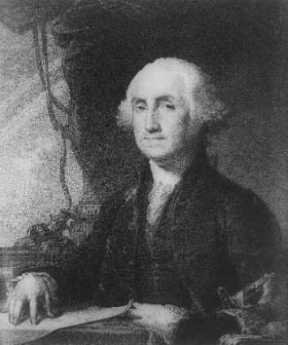

Now, go to the corner of 2nd and Market, where Christ Church displays Colonial architecture at its most breath-taking. If your feet hurt, you could rest by sitting in the pew once reserved for George Washington.

At this point, you have a choice. You can go South on Second Street to the restaurant and hotel area at the foot of Society Hill, eventually going on to a tour of either the elegant mansions to your right or the waterfront marinas and museums, on your left. Or instead, at Second and Market, you can turn West on Market, crossing at 3rd and Market to go through the archway to Ben Franklin's house and museum, eventually to the financial district and the State House. All of these are good choices, and if you are really smart you will do all of them.

Second and Market to Sixth and Walnut

Millions of eye patients have been asked to read the passage from Franklin's autobiography, "I walked up Market Street, etc.", which is universally printed on eye-test cards. Here's your chance to do it.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

Emerge from Christ Church onto Market Street, crossing to the Southside. Between Third and Fourth Streets (318 Market), there is a row of Eighteenth-Century Houses, commissioned by Benjamin Franklin, with a central archway leading to the interior of the block where he placed his own house. The restorationists have cleverly displayed the skeleton of the rafters of the house. When the British occupied Philadelphia in 1788, Major Andre (later to become Benedict Arnold's spy-handler) insolently took Franklin's own house as his headquarters (General Howe took Robert Morris's much more splendid house further up Market Street between Fifth and Sixth.) John Andre was court jester for the British officers. He was a poet, playwright, wit, and dashing life of every party. Washington was in tears when he ordered his hanging.

Continue on and out the South end of Franklin Court, onto Chestnut Street, after you have visited the Museum of Ben Franklin, aimed at children but containing examples of his many inventions, a theater with interesting short presentations, and a fascinating sound and light show of Franklin's great moments. The somewhat unexpected underground building is a product of the famous architect, Frank Venturi. At the corner of 3rd and Chestnut (where a restaurant now stands) once stood the house of Alexander Hamilton, and a few houses further North on 3rd Street remains the dilapidated remnant of the business of Anthony Drexel, the mentor and later senior partner to J.P. Morgan. Turning about and looking south, you can see the reason for this concentration of financiers. Just south of Chestnut is the First Bank of the United States (the fascinating Museum of Old House Parts is on the second floor), while the two blocks of Chestnut Street -- Third to Fifth Streets -- are filled with the massive stone piles of other banks of Philadelphia, culminating in that Parthenon-appearing Second Bank, Nicholas Biddle's bank. In the forty years before Andrew Jackson and Martin van Buren interfered, it wasn't Wall Street that mattered, it was Chestnut Street.

Proceed westward on Chestnut Street, and pass the converted bank now used by the Chemical Heritage Foundation, followed by another bank used by the American Philosophical Society as an auditorium. On the other side of the street, an alley leads southward to Carpenters Hall, where the First Continental Congress held deliberations. At that time, it was the largest private building in the Colonies.

Continuing to Fifth and Chestnut, you may wish to take a detour south to around Sixth and Pine to see the mansions of Society Hill, particularly the Powell House and the Physick House. Intermingled with the red brick Georgian style are examples of classical style reflecting French influence. Our present tour, however, points you to the red brick building just to the south of Independence Hall on Fifth Street. It looks like part of the State House complex but is actually the home of the American Philosophical Society, now housing its fascinating museum (seen only by appointment). After that, by all means, stand in line and take the National Parks tour of Independence Hall, which is one of the best displays in the whole Park Service. After that, the tour of the Liberty Bell on the north side of Chestnut is just a trifle tame, but a mandatory visit.

|

| The Curtis Building |

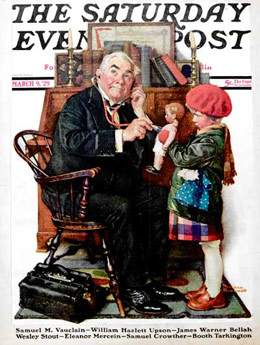

Do not neglect to cross Sixth Street to the Curtis Building, where a few steps inside is the astonishing mosaic constructed by Louis Comfort Tiffany out of Tiffany glass, based on the artistry of Philadelphian Maxfield Parrish. Look around the lobby, which is pretty ornate, but it once held printing presses for the Saturday Evening Post.

Emerge from the Curtis Building on the Seventh Street side. Take a look at the Atwater Kent Museum of the City of Philadelphia, then notice the Jeweler's Row on Samson Street. The house where Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence is at the corner of 7th and Market; it's a reproduction, however. This would bring you back to the subways and high-speed line where the tour began. Instead, the full tour goes back to the Curtis Building and heads south.

Sixth and Walnut to Broad and Samson

In 1751, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce was 'way out in the country. Now it is in the center of a city, but the area remains dominated by medical institutions.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

As you emerge from the Curtis Building, it is worth a half-block detour to 7th and Samson to glance at Jeweler's Row, a curious concentration of diamond merchants who have clustered there since before the Civil War. However for this leg of the tour, turn about to Washington Square, now a quiet manicured residential square but once the site of the Walnut Street prison, the location of the first balloon ascension, the potters field of colonial days, and the home of the unknown soldier of the Revolutionary War. There are accounts of people catching abundant fish in a brook once running through the square, well into the Nineteenth Century. Because of the brook, there were tanneries in the region; tanneries always smell bad. Accordingly, the deed from the Penn family for the Pennsylvania Hospital nearby is revocable if anyone ever decides to build another tannery on its grounds.

|

| Athenaeum of Philadelphia |

On Sixth Street, a few feet south of Walnut, is the splendid brownstone Italianate structure of the Athenaeum, established just after the Revolution as a private lending library, and continuing to today. It's well worth a brief visit to grasp why Lafayette joined it, and so many other members have contributed Nineteenth Century, mostly French, sculpture and paintings. Next door is the former home of then-Mayor Richardson Dilworth. It looks vaguely Georgian in style but was actually built forty years ago as Dilworth's personal statement that Society Hill needed to be revived as a fine place to live. Although Charles Peterson is credited with the idea of starting Society Hill by restoring Stephen Girard's house at Third and Spruce, Peterson bought it for $1800 and eventually sold it for millions. By contrast, Dilworth spent millions for his house, and it later sold for much less. Although they served the same cause, the two men of entirely different social class were always rather reserved with each other.

Cross the grassy Washington Square, turning left on Seventh Street. Until 1980, this area was the home of publishing, mainly medical publishing, but now publishing's loft buildings have been converted to condominium apartments. The penthouses on the top of these buildings are invisible from the street, but are truly spectacular.

Spruce Street itself is a sort of architectural museum, with houses on the Delaware dating to 1700, getting progressively more recent as you go West. At the level of Seventh Street, the houses date from around 1810, eventually reaching Broad Street around 1890. Midway up the block of Spruce Street from 7th to 8th on the North Side (the South Side is nothing but a facade, covering hospital buildings) is the house --really two houses run together -- of Nicholas Biddle. He had more backyard than most houses in the suburbs now do, even once keeping a baby elephant there. The house was made famous for dinner parties conspiring against Andrew Jackson, and later its social glamour was described admiringly by that gossip diarist of the time, Sydney George Fisher.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

At Eighth and Spruce, one half of a city block is occupied by the most modern of hospitals, now tending 440 patients after the manner of a medical Swiss watch. The remaining half of the block is a museum of American Medical History, polished and manicured by professional museologists. There are, however, many people still alive who remember when it containing 160 desperately sick poor people, tended to by unpaid nursing students and resident physicians. It is frequently said that the history of American Medicine is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital .

At Ninth and Spruce, Joseph Bonaparte the Emperor's brother once lived, subsisting on a steamer trunk of gold coins he brought along. Continuing north to Locust Street, Thomas Jefferson University begins and stretches for several blocks in all directions. Before turning west, however, glance down to the southwest corner of 8th and Locust, the original Musical Fund Hall. The music moved west to Broad Street, but the Musical Fund Building was long the largest auditorium in town, housing entertainments, and graduations. Abe Lincoln was nominated for his second term, there. Turning about to view Jefferson, it is easy to believe it is now the largest employer in Center City, and furthermore owns most of the major hospitals in the Pennsylvania suburbs.

Now proceed west on Walnut (although if hungry you might instead wish to take a short detour to the Reading Terminal Farmers' Market), going past the little alley between 12th and 13th Streets called Camac Street, a street of little clubs the most notable of which is the Franklin Inn. Note that Camac Street is paved with wooden blocks, to deaden the clip-clop of horses' hooves. At the corner of 13th and Walnut is the Philadelphia Club, the oldest and toniest men's club in town with a membership limited to 300. As you reach Broad Street, you can see the brownstone gingerbread of the Union League, now by far the largest and most successful club in town.

|

| Philadelphia City Hall |

Further north on Broad Street looms City Hall, designed to be the tallest building in the world but superseded by the Eiffel Tower made of tinker toys while the Philadelphians struggled to build with solid stone. Short of the Maginot Line, it is hard to imagine any building more solid than this one. No expense was spared, and it is really worth a tour. That little statue of William Penn on top is 37 feet tall. Just across the street to the north of it is the Masonic Temple, an equally spectacular series of architectural flourishes. If you visit (the public is quite welcome), you will never forget seeing this place. The Masonic Temple is not an imitation of City Hall; it was built there first.

So that's the end of our one-day historic walking tour of historic central Philadelphia. No doubt you are tired and want to go home. We've left you right by Suburban Station (17th and Arch) if you are going to the suburbs. If you are going to New Jersey, take the high-speed line at Broad and Locust (there's an entrance downstairs on the two eastern corners).

Billy Penn's Hat

|

| Billy Penn's hat |

Philadelphia City Hall was intended to be the tallest building in the world, so there was no reason to suppose anything in Philadelphia would be taller. Gradually, taller buildings in other cities were built, but there grew up a gentleman's agreement that no skyscraper would be built in Philadelphia that was taller than William Penn's hat atop his statue on the tower of City Hall. Planning in the city was organized around this premise, which affects subways and other transportation issues in the city center. Because of assassination fears, a similar tradition in Washington DC was enacted into law, and it must be admitted that the flat skyline of that city looks a little dumb and boring. But Philadelphia neglected to pass a law, and so at the end of the Twentieth Century first one and then half a dozen skyscrapers were built that were twice the height of City Hall, immediately destroying the organizing visual center of the city. Pity.

But there are more serious issues involved. Aesthetics aside, who cares if someone bankrupts himself building an inappropriately tall building, with excessive elevator costs, problems with reinforced foundations, shortage of parking space, and the like? And the answer to that is the new tall building will bankrupt the older office buildings, not itself. Using offers of low, low rents to fill the new building, tenants will be drained from other spaces, and other areas of the city will deteriorate unless there happens to be a general shortage of office space in the region. Carried to an extreme, all of the center city business might be envisioned to reside in one thousand-story building, and the rest of the region would be a desert.

The obvious response would be that no landlord wants to have competition, and new construction is the way a city renews itself, creatively destroying the old to make room for the new. You must not allow the vested landlords to capture the political process with agitation if not bribes. Push things too far in that direction, and you will find that political corruption has destroyed the fabric of the town more effectively than a couple of skyscrapers ever could. Market East has been devastated, it is true. But that's the price of conducting the commerce of the region on the basis of market economics instead of through bureaucracy which masks corrupt politics with high-flown language. Paris is beautiful, but France has 12% unemployment which is closer to 16% if you remember the 30-hour week, the nine-week vacations, and retirement age in the fifties.

And yet, there is certainly a point to be made here. The height limit on new construction must bear some relationship to the regional need for new office space, and not merely rely on beggar-my-neighbor. We're currently hearing about two new projected skyscrapers, one beside 30th Street Station, and the other at 17th and Market/Chestnut. The decision to go or no-go will rest with whether the developers can find "lead" tenants. The corporate officers of these large enterprises are the ones who must be expected to give careful consideration to the best interest of the community because right now they are the ones who control matters. If they neglect their responsibilities, the pressure to pass more zoning laws will prove hard to resist.

Mayors and Limos

|

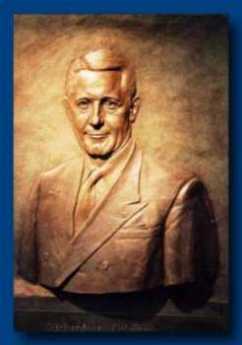

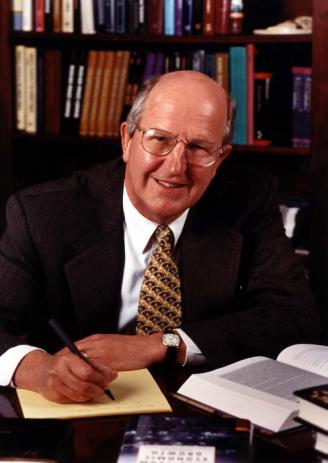

| Mayor Richardson Dilworth |

A number of prominent figures participated in the downtown revival of Philadelphia after the Second World War, with a surprising amount of jealousy among them. Mayor Richardson Dilworth would have to be mentioned in any list of those leaders, but one who was more admired than loved. Aristocratic and flamboyant, he disdained the little hypocritical dissembling so characteristic of politicians. In fact, he didn't see himself as a politician at all, he was a leader.

Once Dilworth became convinced that Society Hill revival was not only desirable but feasible, he moved there. He purchased two houses next to the Athenaeum on Sixth Street, and in spite of the protest of preservationists that those two houses were particularly fine examples of Federalist style on Washington Square, he had them torn down. Furthermore, in spite of outcries that the house he was building in their place was merely a pseudo-colonial gesture, he constructed a very expensive but extremely comfortable modern house. Those of us who were familiar with the neighborhood were impressed with the courage he displayed in doing this, because the area was just a little dangerous, and almost no one else lived there. You could buy dozens of twenty-room houses in the neighborhood for less than $2000 apiece, and it seemed foolhardy to make such a large personal investment in what might become a stranded gesture. This was described as flaunting his personal wealth because it was not just a fine house, it was possibly going to be a big loss.

Dillworth got away with it. He was seen as courageous, and a leader. Others started moving into the area, mostly rehabilitating old mansions. By the time the house was eventually sold by his estate, his conspicuous consumption turned out to be a profitable investment. Smart.

Dilworth had some practical problems. It wouldn't have been smart politics to have a long black limousine pick him up in the poor neighborhood. The only people who do that are undertakers and the Mafia. On the other hand, the driver of a limousine often doubles as a bodyguard, and a bodyguard wouldn't be a bad idea. Those of us who drove down 6th Street every morning at 8:30 gradually noticed what Dilworth did to solve the problem.

|

| Frank Rizzo |

Every morning a Yellow Cab could be seen parked outside his door. It always had the same uniformed driver, and on closer inspection, the cab was the cleanest shiny late-model car, painted yellow. It was only six or seven steps from the door of the house to the door of the car, and he was off and gone in a moment.

Other mayors have had quite different styles.Frank Rizzo had his long black car and several like it parked on the sidewalk outside City Hall. His image was that of a poor boy from the neighborhoods who had made it to the top. No matter where he went, Rizzo was leading a parade.

|

| Ed Rendell |

Ed Rendell, on the other hand, was playing the role of America's Mayor. His driver would blow the horn, put on the headlights during the day, roar through town, making screeching u-turns right and left. Several times a day he would put on this act, going two blocks from City Hall Annex to the Convention Center, to address an audience of visitors.

Well, mayors and bank presidents are supposed to have limousine service. Anyone else would have to ask whether it was worth all the trouble if instead, you could just catch a cab. Those long cars are surprisingly uncomfortable to ride because the roof is so low you have to crawl on hands and knees to get in a seat. Finding a place to park one of those monsters, or even a wide enough opening next to the curb to let out the back-seat occupant, can be a problem in the center of a city. Even with portable cellular phones, there is a delay after you call for the car when you are ready to leave your appointment. Those who have tried it find that hiring a driver almost always confronts you with a demand to circumvent taxes by paying the driver in unrecorded cash. In South America, where bodyguards are really necessary, the great majority of them flee in terror at the first sign of the underworld. Limos are a pain.

At least in Philadelphia, you can get a fairly clean, fairly new cab with a fairly knowledgeable driver, by simply holding up your hand at any center city street corner. During business hours at least, you can hail a cab in three minutes. That doesn't just happen that way, and the mayor has something to do with it. Cities usually have a Medallion system of cab licensing, and existing cab companies don't want any medallions issued to competitors. In politics, such a situation helps campaign funds considerably. The result is a shortage of cabs, surly drivers, and high prices. Boston is such a town. On the other hand, if medallions are easy to obtain, as they are in Washington DC, the cabs become numerous enough but are shabby dilapidated old vehicles, driven by recent immigrants who don't know the street names. In Philadelphia, we take our good fortune for granted, but we do owe a debt to the city government for managing the supply and demand situation to the point where it mostly would be foolish to have your own car and driver. In this town, every man a king.

As a matter of fact, in Boston it got so bad that Ned Johnson, the richest man in town (he personally owns the Fidelity Mutual Fund Investment Family) got so enraged that he couldn't ever get a cab that he founded his own cab company. It's a very elegant one, although a little expensive. The Boston Coach Company supplies immaculate and impeccable service for a fee. At first, it was only available to Fidelity executives but now has spread out to anyone willing to pay for it, and flourishes in many cities, plus chartered airplanes if you don't like to wait in security lines at airports. You have to admire Johnson for his golden business touch, but in Philadelphia, we can just use cabs.

The Center of Town

|

| city hall |

It took two hundred years for the inhabited part of the city to reach the square which William Penn had envisioned for the center of his green country town, and by the time it did, the area around City Hall had come to resemble the town planning concepts ordinarily associated with the Scotch-Irish immigrants.

It sort of goes like this: the Scotch-Irish had been kicked out of Scotland and they were soon kicked out of Ireland, so they were far less emotionally attached to their local soil than other European groups. So they were probably the first group to regard real estate as a commodity rather than a repository of wealth, or a religious shrine, as other groups often do. It soon became evident to them that the best real estate was usually found at the crossroads, and the more important the intersecting roads, the more valuable that real estate was going to be someday. Accordingly, early Scotch-Irish settlers roamed around their new country, looking for likely crossroads, and buying up the local property for speculation.

The pattern of the diamond appeared, with a town square placed at the crossroads, traffic diverted around the square, and commercial real estate established around the rim of the square which usually had a flagpole placed in the middle of the central park. New England had city centers and town commons, but the two were usually not the same thing. The diamond pattern is very characteristic of rural Pennsylvania, and up and down the Appalachian valleys where the Scotch Irish had spread. It is the pattern of Philadelphia City Hall Square, no matter whose idea it was originally. Let's face it. City Hall is at a crossroad of the two main traffic arteries, Broad and Market Streets, wide and straight, stretching for miles in each direction.

North of Market

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

In their 1956 book "Philadelphia Scapple", Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Mrs. Henry Cadwalader give an interesting description of the evolution of the term "North of Market". In the early days of the city, almost all of the town was South of Market Street. In fact, an early 18th Century visitor once wrote that he always brought a fowling piece when he visited Philadelphia because the duck hunting was so good at the pond located at what is now 5th and Market.

When the Quaker meeting house was built at 4th and Arch Streets, many of the more important Quaker families thought it was important to build their houses nearby. In that way, Arch Street developed the reputation of being a Quaker Street. So the original meaning of the North of Market term was the Quaker ghetto. Quaker families continued to spread West along Arch Street or nearby, and this accounts for the location of the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry and related local activities. When the Free Quaker were evicted from the meeting at 4th and Arch because of their activities during the Revolution, they built their own meeting at -- 5th and Arch.

|

| Chinese wall |

During the Civil War, a number of people made fortunes that socially upscale people over in the Rittenhouse Square area considered disreputable, so elaborate but ostracized mansions marched due North up Broad Street, where they can still be observed as stranded whales in the slums, leaders without followers. The show houses of manufacturers of shoddy war goods soon gave the meaning of parvenu to the term North of Market.

And then, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran an elevated brick structure from 30th Street to City Hall Plaza, the so-called Chinese Wall. For nearly a century this ugly looming structure on Pennsylvania Boulevard, now John Kennedy Boulevard, with its smoky engines above, and dark dripping tunnels at street level, sliced the town in half and made it very unattractive to build or to live, North of Market. The Spring Garden area had some pretty large and expensive houses, but it was cut off by the railroad trestle and has only recently started to revive. It helped a lot to tear down the Chinese Wall, but that was fifty years ago, and the area has taken a long time to recover from the earlier diversion of social flow to the South of it. And, psychologically, North of Market will take even longer to recover from the implication of -- industrial slum.

|

| center |

Meanwhile, of course, Oriental immigration settled along Arch Street at 9th to 12th Streets, and we now have our Chinatown there, complete with street signs in oriental lettering. In effect, we have a real Chinese Wall, a social one. Just what will happen to this group is unclear, since it is readily observable that they like to cluster together, unlike the East Indian immigrants, who head for the suburbs as fast as they can. Since the Chinese colony is physically blocked on all sides by the Vine Street Expressway, the Convention Center, and the Ben Franklin Bridge, it is hard to know where they will flow if the group gets much larger. The depressed Vine Street crosstown expressway makes a definitive border for downtown, and the contrast between the two sides of this expressway is striking. On one side is Camelot, and on the other side, almost nothing is being built. The future of North of Market, at the moment, is a little unclear.

Venturi's Franklin Museum in Franklin Court

|

| Franklin Court Museum |

When Judge Edwin O. Lewis was seized with the idea of making a national monument out of Colonial Philadelphia, he wanted it big. Forty or so years later, it's big all right, but not big enough to encompass the whole of America's most historic square mile. Government ownership in the form of a cross now extends five blocks north from Washington Square to Franklin Square, and four blocks East from Sixth to Second Streets. Restoration and historic display have spread considerably beyond that cross, however, and the Park Service has created ingenious walkways within the working city in the neighborhood. If you thread your way through these walkways, you can stroll for miles within the world of William Penn and Benjamin Franklin. One such unexpected walkway is now called Franklin Court, which essentially cuts from Market to Chestnut Streets, within the block bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets. Hidden in the center is the reconstructed ghost of Franklin's quite large house, sitting in an interior courtyard bounded by a colonial post office, and a newspaper office once operated by Franklin's grandson. And, along the side of the walkway near Chestnut Street, is a fascinating museum of Franklin's personal life, built by no less than Frank Venturi, and operated by Park Rangers in the polished but low-key manner for which the U.S. Park Service is famous.

For some reason, this jewel of a museum has not received the high-powered publicity it deserves. It's off the main Park premises, as we mentioned, and some of the problem has to be attributed to Venturi. As you walk through, you don't expect a huge museum to be there, and it can look pretty inconspicuous as you walk past because it is mostly underground. Take my word for it, it's worth a visit. There are long descending ramps inside the doors, which can be pretty daunting if you are elderly and tired. But, also inconspicuous, there's an elevator if you look around for it. Venturi didn't seem to like windows very much, which is a problem for some people.

There's a movie theater inside there, playing a long list of fascinating documentaries. There's an ingenious automated display of statuettes which utilize spotlights and revolving stages to present Franklin in Parliament, resisting the Stamp Act, Franklin being his charming self before the French monarchs, and the frail dying Franklin getting the Constitutional Convention to approve the document. There are also a variety of ingenious inventions of Franklin's on display in the original, including bifocal glasses, the first storage battery, a simplified clock, several library devices, the Franklin stove, and so on. In some ways, the highlight is the Armonica.

The Armonica is the musical instrument invented by Franklin, for which both Beethoven and Mozart composed special music to exploit its haunting tone. If you ask the nice Park Ranger, she will be flattered to play you a tune on it.

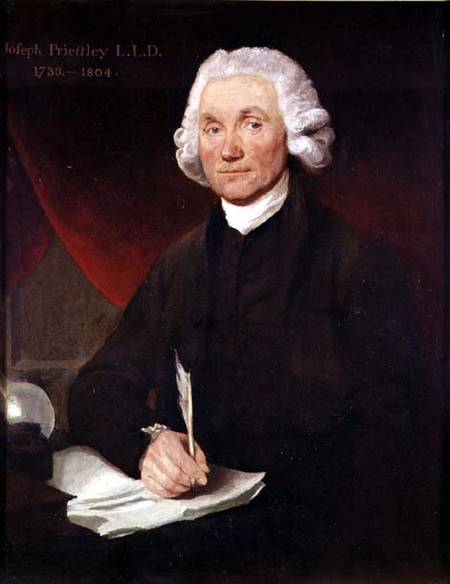

Franklin Declares Independence a Year Early

Joseph Priestly became a close friend of Benjamin Franklin almost as soon as they met. Priestly was an Anglican clergyman who broke loose and formed the Unitarian Church, and meanwhile, his scientific discoveries also entitle him to be called the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, of course, was the discoverer of electricity; it would be hard to be sure which of the two was more brilliant. In July, 1775, Franklin wrote the following letter to Priestly, which makes a trenchant case that the American colonies should, and would, break away from England. Since some legal authorities, following Lincoln's lead, maintain that Jefferson's manifesto "informs" the United States Constitution, it might be well to begin referring to this letter as an even clearer statement of the mindset of America's founding leaders.

|

| General Thomas Gage |

" Dear Friend (wrote Franklin),

"The Congress met at a time when all minds were so exasperated by the perfidy of General Gage, and his attack on the country people (i.e. Of Lexington and Concord), that propositions of attempting an accommodation were not much relished; and it has been with difficulty that we have carried another humble petition to the crown, to give Britain one more chance, one opportunity more of recovering the friendship of the colonies; which however I think she has not sense enough to embrace, and so I conclude she has lost them forever.

"She has begun to burn our seaport towns; secure, I suppose, that we shall never be able to return the outrage in kind. She may doubtless destroy them all; but if she wishes to recover our commerce, are these the probable means? She must certainly be distracted; for no tradesman out of Bedlam ever thought of increasing the number of his customers by knocking them on the head; or of enabling them to pay their debts by burning their houses.

"If she wishes to have us subjects and that we should submit to her as our compound sovereign, she is now giving us such miserable specimens of her government, that we shall ever detest and avoid it, as a complication of robbery, murder, famine, fire, and pestilence.

"You will have heard before this reaches you, of the treacherous conduct to the remaining people in Boston, in detaining their goods, after stipulating to let them go out with their effects; on pretence that merchants goods were not effects; -- the defeat of a great body of his troops by the country people at Lexington; some other small advantages gained in skirmishes with their troops; and the action at Bunker's-hill, in which they were twice repulsed, and the third time gained a dear victory. Enough has happened, one would think, to convince your ministers that the Americans will fight and that this is a harder nut to crack than they imagined.

"We have not yet applied to any foreign power for assistance; nor offered our commerce for their friendship. Perhaps we never may: Yet it is natural to think of it if we are pressed.

"We have now an army on our establishment which still holds yours besieged.

"My time was never more fully employed. In the morning at 6, I am at the committee of safety, appointed by the assembly to put the province in a state of defense; which committee holds till near 9, when I am at the Congress, and that sits till after 4 in the afternoon. Both these bodies proceed with the greatest unanimity, and their meetings are well attended. It will scarce be credited in Britain that men can be as diligent with us from zeal for the public good, as with you for thousands per annum. -- Such is the difference between uncorrupted new states and corrupted old ones.

"Great frugality and great industry now become fashionable here: Gentlemen who used to entertain with two or three courses, pride themselves now in treating with simple beef and pudding. By these means, and the stoppage of our consumptive trade with Britain, we shall be better able to pay our voluntary taxes for the support of our troops. Our savings in the article of trade amount to near five million sterling per annum.

"I shall communicate your letter to Mr. Winthrop, but the camp is at Cambridge, and he has as little leisure for philosophy as myself. * * * Believe me ever, with sincere esteem, my dear friend, Yours most affectionately."

[Philadelphia, 7th July, 1775.]

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Armonica, Momentarily Mesmerizing

|

| Ben Franklin's Glass Armonica |

Everyone knows Ben Franklin spent a lot of time holding a wine glass. Evidently, he noticed a musical note emerges if you run your finger around the open mouth of the drinking glass, and systematically studied how the tone can be varied by varying the level of liquid in the glass. The same variation in emitted tone relates to variations in the thickness of the glass. So, he set up a series of different sized glasses impaled on a horizontal broomstick, enough to cover three octaves, rotated the broomstick with a treadle like those used for spinning wheels -- and made music. The tone has a haunting penetration to it, which induced both Beethoven and Mozart to write special compositions for the harmonica, and the Eighteenth Century went wild with enthusiasm.

|

| Glass Armonica |

Unfortunately, a number of the young ladies who played the armonica went mad. We now recognize that since the finest crystal glass was used, with very high lead content, the mad ladies were suffering from lead poisoning after repeatedly wetting their fingers on their tongues. As a matter of fact, port wine at that time was stored in lead-lined casks, resulting in the same unfortunate consequences, which included stirring up attacks of gout. Franklin himself was a famous sufferer from gout, which was more likely related to the port wine than playing the harmonica, in his particular case.

Anyway, the reputation for inducing madness added to the spooky sort of sound the instrument made, attracting the attention of a montebank named Franz Anton Mesmer, who falsely claimed to be the father of hypnotism. Mesmer enhanced the society of his stage performances by hypnotizing subjects while an assistant played the harmonica, meanwhile relating all sorts of wild tales about animal magnetism. This was pretty sensational at the time until a young man in an audience suddenly died. It is now speculated that the victim probably had an epileptic seizure, but the news of this public fatal event pretty well finished Mesmer as an evangelist and the harmonica as a musical instrument.

|

| Franklin Court |

There's a replica of an armonica on display in the Franklin Court Museum around 3rd and Chestnut, which we are vigorously assured is not made with leaded crystal glass. The Park Rangers put on two daily performances by request, at noon, and 2:30 PM.

Jewelers Row

|

| Jewelers Row |

Since 1851 Jewelers have clustered on Samson Street mostly between 7th and 8th Streets, and for a block or two in all directions. Sixty years before that, the area had been the site of the most elaborate mansion in America, commissioned by Robert Morris, the Financier of the American Revolution, and built by Charles L'Enfant, the architect of the District of Columbia. About 150 jewelry and jewelry-related businesses are now located in this district, and their outward appearance suggests progressively improving prosperity for them. Some of this reflects the fear of impending inflation (national budget deficits and all that), or a possible decline in the value of the dollar, which amounts to the same thing. During inflationary times, the value of commodities increases; gold and diamonds are the ultimate commodities. In fact, it is widely believed that the price of gold has little to do with jewelry or commodities, and is mainly dependent on the prevailing level of distrust of paper money. For their part, diamonds additionally suit themselves to be hidden in the heel of your shoe if things get tough enough.

|

| Jeweler Shops |

However, J. E. Caldwell's just moved out of the center of the city, and Bailey, Banks and Biddle were sold to people from Texas or somewhere. So the jewelry trade is not universally prosperous, just Samson Street, the Jewelers' Row. Why in the world would 150 little jeweler shops want to cluster together, where people mostly can't tell one from the other, and the products look pretty much alike to anybody who isn't in love and looking for an engagement ring? You would think a competitor next door on either side, and another competitor upstairs, and still others across the street would be something a shrewd merchant would flee, not seek out. Come to think of it, the same thing is true of Antique Row, or the fabric cluster, or a dozen similar clusters in New York City. In New York, it is possible to see a dozen shops next to each other, every one of them selling trombones.

|

| Professor Michael Porter |

Michael Porter of the Harvard Business School has offered an explanation of the economics of a business cluster as an "Innovation cluster". He feels clustering is one of the important ways businesses hold down costs and improve productivity, by innovating rather than merely stressing efficiency. If efficiency and productivity sound like the same thing, it may help to know that efficiency is only a part of productivity, with profitability to the owner of the firm only increasing if the quality of the product steadily improves, which holds up retail prices. Let's put the idea in another way: the innovative, latest and greatest, of any product, commands the highest mark up among similar objects. If you position yourself as producing the latest and greatest, you are going to get a continuously higher markup. In an era of declining prices, the higher markup may express itself as simply maintaining the old prices, so anyway being a part of an innovation cluster assures you of the highest profit available, if you must be in that business. Clusters provide vigorous price competition, all right, and that automatically assures that true prices levels (i.e. after a little bargaining) are likely to be trustworthy measures of value, even in a shabby little hole-in-the-wall. Making jewelry is not rocket science, but there's enough to it that it helps to be located in an area with an abundant supply of skilled and experienced employees. Philadelphia's diamond cluster is the oldest, and still the second largest, jewelry district in the country.

|

| Extra Policing |

Having a lot of portable but largely unidentifiable merchandise concentrated in a few blocks creates a special need for police protection. These shops all have safes, and probably most of them have handguns, but there is a great deal of street traffic among shops, carrying valuable gems in their hip pockets. The City provides extra policing out of recognition of the risk, and the local merchants contribute to hiring extra private detectives to lounge around. When basement flooding at the local electric power substation recently caused a blackout, a lot of extra police were immediately dispatched to Jewelers' Row, just in case somebody got the idea that looting might be attractive. And then it is said, just rumored, that some of the merchants who have plenty of goods loaned to their neighbors on consignment employ private protection of an unlicensed sort, in case they have a problem getting their goods back.

It must be pretty boring to sit all day every day in a little shop that makes one or two sales a week, except at special holidays. One jeweler I know has a portable computer under the counter and spends a lot of time day-trading, which is buying stocks in the morning and selling them in the afternoon. Although competition in the district goes well beyond vigorous, there is an active fraternity of jewelers in the area, steering customers to each other when they don't have a requested item themselves, eating lunch at one of the local bistros, exchanging gossip of the trade, carefully observing the traffic up and down the sidewalks. And then, if there is no traffic they can always have their wives, daughters or neighbors sit on a high stool in front of the counter. Trying on jewelry.

Curtis and the Book Trade

|

| The Saturday Evening Post |

Few seem to have commented much on the connection between the death of the Saturday Evening Post and the subsequent decline of the book publishing business. The Curtis Publishing Company published books, of course, but that's only a small part of the matter. The general-interest magazines, the Post in particular, were places where authors built their reputations, often long before they had started writing their books.

The Post would run eight or more long articles each week, and at least two serials. From the parochial point of view of the weekly magazine, a serial was a teaser, getting the reader interested and eagerly looking forward to the next installment and the next after that. Another way of looking at it, however, was as one very long piece, larger than a magazine article, but not as big as a book. Sometimes, an eight- or ten piece serial was longer than a small book. This was a wonderful incubator for new authors, and for advance publicity for established authors planning a forthcoming book on the same topic. The big magazines paid pretty well for articles, so writing for the Post was a good way for an author to support himself during the long famines between big books.

|

| Cyrus H.K. Curtis |

The general interest magazine wasn't designed for the purpose of supporting the book publishing industry, but it definitely evolved that way. With the disappearance, of not just the Post but of all general interest weekly magazines, the dynamics are now a lot clearer. A new author of a book today has a terribly difficult time establishing a name and a following. The striking thing is that the advent of the home computer has caused an enormous outpouring of new, excellent, manuscripts which cannot find a publisher because it's so hard to get a first-book author established. In 2006, over two hundred thousand new books were published, and many obscure titles were actually quite good books. With shorter print runs as the market gets splintered, the cost per book has skyrocket Dutch and German companies, plus a vast number of small self-publishing enterprises. Much of this sad phenomenon has been blamed on TV, or the Internet, or the school systems. You just can't get people to read and write, these days it is said, but don't believe it. There are dozens of books languishing today that would have competed very effectively with Hemingway and Dreiser and Aldous Huxley. What's much harder is to get a readership assembled for a new author without spending a king's ransom on hype and publicity; if you are going to invest that much money, the business imperative is to invest it on trash, because trash really will sell if you hype it enough. High-class literature is supposed to sell itself.

Every new author is shocked to discover that it takes a full year for his manuscript to wend its way into the bookstores if you can find a bookstore. It doesn't take that long to edit and design a book. It takes that much time to arrange the publicity, and pace its appearance for the book fairs, for the Christmas season, and the reviewers. You can give a free book to a reviewer who truly means to read it, but he may not read it for months. Most book distributors and sellers will not accept a book until they see what the reviewers say. It takes a long time, it costs a lot of money, and it often is unsuccessful. It's all pretty pathetic, compared with sending a chapter to the Saturday Evening Post, getting paid to put your author in front of ten million readers.

Carpenters Hall

|

| Carpenters Hall |

The birthplace of our nation is both smaller than you would expect and larger. The fire marshall now says no more than 83 people may rent it for a sit-down affair, or 103 for a stand-up gathering. However, the internal partitions have been removed from what was once a center-hall building with a meeting room on either side; it now is a large open room in the form of a Greek cross. At the time of the revolution, Benjamin Franklin's Library Company occupied the second floor, so the First Continental Congress had to find a way to do its work in the side rooms of the first floor, to the side of the center hall. There were 53 delegates, and presumably some staff and visitors.

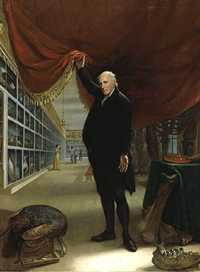

That sounds rather crowded, but it was nevertheless the largest rentable public space in the city. John Adams arrived early for the convention, conniving with several other early arrivals at the City Tavern. Adams made the following notation in his diary: Monday. At ten the delegates all met at the City Tavern and walked to the Carpenters' Hall, where they took a view of the room, and of the chamber where is an excellent library; there is also a long entry where gentlemen may walk, and a convenient chamber opposite to the library. The general cry was, that this was a good room, and the question was put, whether we were satisfied with this room? and it passed in the affirmative." Alternative places to meet would have been in churches, which presented awkwardness, or in the State House (Independence Hall) which was then under the control of Tories.

|

| Continental Congress |

France and the rebellious colonies was a complicated one, with intrigue and mistrust at every turn. One interesting episode had to do with Franklin's library on the second floor. The French ministry had sent over a spy, to size up the colonists before the French risked too much on them. So, the spy was led up to the library and allowed to overhear some bellicose conversations going on downstairs -- thoroughly stage-managed for the benefit of the "hidden" French visitor.

The Carpenters Company was a guild of what we would now call builders and architects, and architects continue to use it. The first floor usually displays a few Windsor chairs dating to the Continental Congress, covered with a rich black patina that really lets you know what a patina was. Upstairs, the staff quarters are now, well, a little on the elegant side so you can't visit. The guild was formed in 1724, and fifty years later had just completed its building, in time for its historic role in 1774.

|

| Elfreth's Alley |

With the whole continent available for building, it is still not entirely clear why Colonial Philadelphia crowded itself into half a square mile, with crowded little row houses on crowded little alleys. But that's the way it was, now visible in the location of Carpenters' Hall down a little cobbled alley, in the center of a block. Elfreth's Alley gives you the same feeling, and perhaps Camac, Mole, and Latimer Streets. Carpenters' is a lovely little place, with lots of interesting features, but the main interest lies in what took place there. For that, you have to read a few books.

Washington Square

|

| Washington Square |

Although he spent a lot of time in Rittenhouse Square in Philadelphia, Henry James wrote about Washington Square in New York. It was Christopher Morley who wrote about Washington Square in Philadelphia. The best short essay about Philadelphia's Square is found in this link.

The subject of Washington Square includes an interesting variety of topics, including the Walnut Street Prison, famous balloon rides, the Athenaeum, Penn Mutual Life Insurance, Curtis Publishing Company, N. W. Ayer, Harry Batten, Lea and Febiger, Lippincott Publishing, Saunders, Orange Street, the St. James Apartment House, Richardson Dilworth, the Farm Journal the old PSFS building, and the Maxfield Parrish mosaic.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Washington Square: Images of America, Bill Double, ISBN-10: 0738565504 | Amazon |

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

|

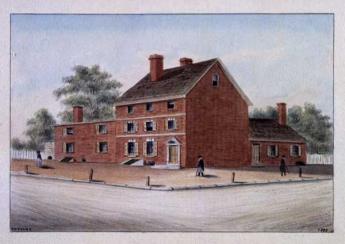

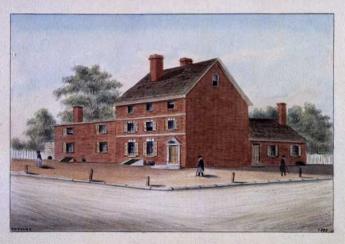

| South East Prospect of Pennsylvania Hospital |

There is a painting of the region around 8th and Spruce Streets in the 1750s, depicting a pasture, with cows, and three or four buildings between 8th and 13th Streets. When the Pennsylvania Hospital moved there in 1755 from its temporary location in a house located a block from Independence Hall, there were complaints that it was now located so far out in the woods that it was difficult and dangerous to go there. Still another description of the area is evoked by the provision which the Penn family placed in the deed of gift of the land, strictly forbidding the use of the land as a tannery. Tanneries have always been notorious for giving off noxious odors, so most people wanted them to be somewhere else, anywhere else. In any event, the main activity of Penn's "green country town" at that time was concentrated closer to the Delaware River, and the nation's first hospital was definitely placed in the outskirts. Two blocks further West the almshouse was already in place, but not much else. We are told that Benjamin Franklin had flown his Famous Kite at 9th and Chestnut, using a barn there to store his materials. It might be recalled that the population of Philadelphia, although the second largest English-speaking city in the world, was only about twenty-five thousand inhabitants at the time of the Revolution, and in 1751 was even smaller.

In any event, the first and oldest hospital in America was built on 8th Street between Spruce and Pine, and the Eighteenth Century buildings on Pine Street still present a breathtaking view at any season, but particularly in May when the azaleas are in bloom, and fragrance from the flowering magnolias fills the evening atmosphere for blocks around. Although some people today mistake the Pennsylvania Hospital for a state hospital, it was founded in the reign of George II, decades before there was such a thing as the State of Pennsylvania. The Cornerstone was laid by Benjamin Franklin, with full Masonic rites. Most doctors regard a hospital as a mere workshop, but the affection with which many Pennsylvania physicians regarded their special hospital is indicated by the number who have requested that their ashes be buried in the garden.

For two hundred years, beginning with the first American resident physician Jacob Ehrenzeller, the interns and residents were paid no salary, so they had to live on the grounds. An Internet was just that, interned within the four walls for at least two years. Because the resident physicians had no money, they stayed in the hospital at night and on weekends, playing cards and swapping stories. The hospital was home for them, as it was for the student nurses, likewise unpaid but more strictly confined and supervised. This penury seemed acceptable because the patients were mostly charity ward patients, otherwise unable to pay for their own care. Ehrenzeller finished his medical apprenticeship and went to practice for many decades in the farm country of Chester County, but gradually upper-class Philadelphia moved from 4th Street westward to and beyond the hospital, and two of the richest men in American history, Morris and Biddle, had houses within a block of the hospital, although Morris never lived in his house, having more pressing matters in debtor's prison. Therefore, later resident physicians at the hospital had the potential of setting up a private practice in the area and becoming society doctors as well as academically prominent ones. Being a charity hospital in a rich neighborhood created the potential for volunteer work by the town aristocrats and large bequests for charity. The British housed their wounded in the hospital during the Revolutionary War and shot deserters against the red brick wall of the small cemetery to the north. A century later, there were a couple of dozen rooms for private patients in the hospital for the convenience of the doctors and the neighbors, but everyone else was a charity patient. And a century after that, the hospital still did not have an accounting department to collect bills and tended to regard people who asked for a bill as a nuisance. Benjamin Franklin is regarded as the Founder of the hospital, and his autobiography famously describes how he fast-talked the legislature into matching the donations of the public, not mentioning to them that he had already collected enough promises to see the project through. This seems in character; Franklin's biographer Edmond Morgan summed up that, "Franklin doesn't tell us everything, but what he does tell us, is straight." The idea for the hospital was that of Dr. Thomas Bond, whose house is now a bed and breakfast on Second Street, but it was characteristic of Franklin to be the secretary of the first board of managers of the hospital. In Quaker tradition, the clerk of a meeting is the person who really runs the show. It thus comes about that the minutes of the founding board were recorded in Franklin's own handwriting, among them the purpose of the institution, which is to care for the Sick Poor, and if there is room, for Those Who can pay. This tradition and this method of operation continued until the advent in 1965 of Medicare when charity care was displaced by concepts which the nation had decided were better. The Pennsylvania Hospital was not only the first hospital but for many decades it was the only hospital in America. Its traditions, sometimes quaint and sometimes glorious, cast a long shadow on American medicine.

REFERENCES

| America's First Hospital: The Pennsylvania Hospital 1751-1841 William Henry Williams Ph.D. ISBN-10: 0910702020 | Amazon |

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Philadelphia in 1976: Legionaire's Disease

|

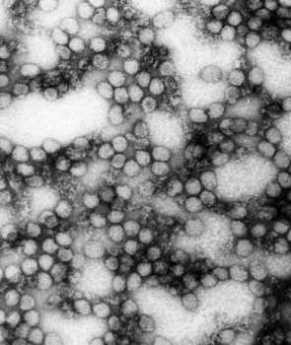

| The Yellow Fever |

No other city in America is remembered for an epidemic; Philadelphia is remembered for two of them. The Yellow Fever epidemic, for one, that finished any Philadelphia's hopes for a re-run as the nation's capital. And Legionnaire's Disease, that ruined the 1976 bicentennial celebration. One is a virus disease spread by mosquitoes, the other a bacterial disease spread by water-cooled air conditioners. Neither epidemic was the worst in the world of its kind, neither disease is particularly characteristic of Philadelphia. Both of them particularly affected groups of people who were guests of the city at the time; French refugees from Haiti and attendees at an American Legion convention.

In 1976, dozens of conventions and national celebrations were scheduled to take place in Philadelphia as part of a hoped-for repeat of the hugely successful centennial of a century earlier. Suddenly, an epidemic of respiratory disease of unknown cause struck 231 people within a short time, and 34 of them died. Every known antibiotic was tried, mostly unsuccessfully, although erythromycin seemed to help somewhat. The victims were predominantly male, members of the American Legion of a certain age, somewhat inclined to drink excessively, and staying in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, one of the last of the grand hotels. Within weeks, it was identified that a new bacterium was evidently the source of the disease, and it was named Legionella pneumophila. Pneumophila means "love of the lungs" just as Philadelphia means "city of brotherly love", but still that foreign name seemed to imply that someone was trying to hang it on us. Eventually, the epidemic went away, but so did all of those out-of-town visitors. The bicentennial was an entertainment flop and a financial disaster.

Since that time, we have learned a little. A blood test was devised, which detected signs of previous Legionella infection. One-third of the residents of Australia who were systematically tested were found to have evidence of previous Legionella infection. A far worse epidemic apparently occurred in the Netherlands, at the flower exhibition. Lots of smaller outbreaks in other cities were eventually recognized and reported. It becomes clear that Legionnaire's disease has been around for a very long time, but because the bacteria are "fastidious", growing poorly on the usual culture media, had been unrecognized. And, although the bacteria were fastidious, they were found in great abundance in the water-cooled air conditioning pipes of the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. Even though the air conditioning was promptly replaced, everybody avoided the hotel and it went bankrupt. When it reopened, 560 rooms had shrunk to 170, and it still struggled. Although there is little question that lots of other water-cooled air conditioning systems were quietly ripped out and replaced, all over the world, the image remains that it was the Bellevue, not its type of plumbing, that was a haunted house. There is even a website devoted to its hauntedness.

At Times, Charles Dickens Was a Little Immature

|

| Eastern State Penitentiary Aerial View |

Every once in a while, Philadelphia needs to be reminded of its Quaker origins, and the surprising number of people who will suddenly make an appearance to defend Quaker ideas. It would appear that Philadelphia needs to be reminded that Quakers see a value, even a joy, in silence. The present entrepreneurs in charge of Eastern State Penitentiary, presently a Hallowe'en showplace, are to be congratulated for rehabilitating a neighborhood formerly in decay. If you are looking for a collection of exotic restaurants after visiting the neighborhood art museums, this is the place to go. But I do wish somebody would put an end to the myth that silence and solitary confinement can drive you crazy because I don't believe they will.

Every Quaker family has to handle the problem that children don't naturally like to sit still. The first few times Quaker children are brought to meet, the kids have to be shushed, given books to read, and eventually be led out early to sit in the First-Day (Sunday school) classrooms, while their parents go back to the meeting room to sit in silence. Some kids get the message quicker than others, and the ones who keep misbehaving in meeting eventually have to face general disapproval as "spoiled" until they either quiet down or get sent to boarding school. So Quakers are familiar with the problem, learn how to deal with it, and tend to regard resistance to silence as a sign of immaturity.

|

| Charles Dickens |

Charles Dickens was once a newspaper reporter in Philadelphia and wrote many ecstatic articles about the city. However, he was paid by the word, and prospered mightily from some unnecessarily long articles directed to the folks back in England. One of them was a description of Eastern Penitentiary, built on the principle of the rehabilitation of criminal behavior by long periods of solitude, remote from distracting criminal influences in the community at large. The idea, which may well have originated with Dr. Benjamin Rush, later called the father of American Psychiatry, was widely imitated. There soon were over three hundred prisons throughout the world, dedicated to the idea and imitating the architecture. Whether he believed it or not, Dickens wrote a long, long, diatribe against the concept of solitude as rehabilitating, in which he imagined himself in the position of the poor prisoner, and declaring it would drive him crazy. Without much argument, Charles Dickens was responsible for the shift in public attitudes which eventually led the Board of Prisons to decide to tear it down. This was not exactly evidence-based psychiatric reasoning since a great many crazy people get sent to prison anyway. It isn't surprising that lots of crazy people were found in Eastern Penitentiary, but it isn't exactly proven that solitary confinement made them into lunatics. In fact, it isn't being based on evidence to claim that either the outcome of recidivism or the outcome of improved behavior is influenced by any form of incarceration, with or without corporal punishment, with or without capital punishment. It is definitely proven that incarceration is as expensive as psychiatric treatment, but that isn't saying a great deal. You can definitely cause temporary insanity with prolonged sleep deprivation, but you would suppose that solitary confinement would increase the amount of sleep, not reduce it.