6 Volumes

BANKS REDEFINED

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Recent Convulsions in World Finance

Few people choose to study economics; most people don't want to. But world economics have got in such a state that lots more of us had better give it some thought.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

A New Era in Politics: Clinton, Obama, and Trump

New forms of communication made the party system largely obsolete.

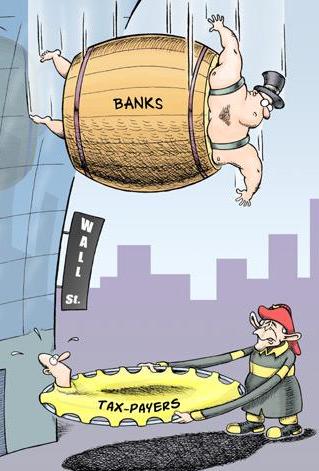

Banking Panic 2007-2009 (1)

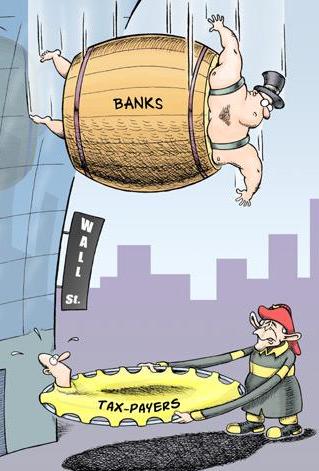

Mankind hasn't learned how to control sudden wealth, whether in families, third-world countries, or the richest nation in history. The world banking crisis of 2007 is the biggest example yet.

IN lifting a billion people from desperate poverty to moderate prosperity, economic globalization has been a premier good thing for the world. Globalization however made many financial stumbles in developing countries; in 2007 even America finally stumbled, badly. Few people now dispute three basic facts: huge new wealth was dumped on the globalized monetary system. Somehow this caused a housing bubble in America. And somehow this bubble toppled Wall Street. Two years after its sudden explosion, opinion about cause is divided into two main camps. One maintains a house of cards is certain to collapse; it's futile to play blame-game when it does. The other viewpoint is that responsible people know enough not to sneeze near a house of cards, so it matters who did sneeze. This article examines the two propositions, concludes that still a third theory is more likely, and propounds it. Fixing a mess this complex so it never happens again, is a project too large to succeed unless many people grasp what it was really all about. Even if they can't fix the problem, at least they can listen to the Greek physician Hippocrates: Don't make it worse.

Perhaps real estate stresses, banking stresses, and the stresses of emerging economies all relate to the same flaw in human character, the difficulty adjusting to sudden great wealth. The goal here, however, is not philosophical elegance, but to get out of an economic mess, at a minimum not worsening or repeating it. The world monetary order may well be at the root of the problem, but world monetary order can wait until more tangible things are fixed. So, in this article it comes last, except for this initial declaration: A wealthier world made America richer, too, and we shamefacedly admit we couldn't handle it.

Hovering in the background, moreover, the computer information revolution made everything move faster, surprises come sooner; problems quickly grew huge before being recognized. Over a hundred other national banking crises have erupted in the past thirty years of the computer era, mostly confined to small poor countries with scant experience. World history shows sudden new wealth, while welcome, violently disturbs the existing order. It is little different whether new wealth comes from gold rushes or striking oil, from inventions, or new forms of securities trading. Previous wealth and experience help steady the balance, but to think one is immune to the nouveau riche weakness only means one has not tasted large enough doses of it.

August, 2007: Sudden Financial Jolt

For the moment, the broadly unanticipated behavior of world bond markets remains a conundrum.

|

| Alan Greenspan, Feb.16, 2005 |

In early August, 2007 the stock market was sailing along nicely. A great many people were on vacation. September is traditionally the month for severe market reversals, but this year in early August there was not much sign of an impending jolt. The stock market's Dow Jones Industrial Average had reached an all-time peak over 14,000. Long term interest rates were abnormally low, it is true, but that anomaly had gone on uneventfully for years; anyway, even Alan Greenspan said he didn't understand it. Suddenly, the Dow Jones Industrial Average dropped 400 points in ten minutes, on heavy volume. It takes a big volume of sales to move the market that much, that quickly. Somebody knows something, but I don't know what it is, was the thought at ten thousand trading desks watching computer screens, worldwide. A quick check with networked friends showed that nobody else seemed to know what was stirring things up, either. In retrospect, we still don't know who did the first heavy selling, but it soon spread to hedge funds. Hedge funds have a lot of money, and vast banks of computers to do their selling. When the computers of heavy traders detect sudden selling volume, they are programmed to sell, too. Don't ask questions; somebody must know something, so get out, get out the door without a backward look. Not only was someone selling big, but probably selling short. The commentators on cable TV started jumping up and down, talking all at once.

|

| Graph: Prices of 10-yr Bonds |

About a day later, someone made a shrewd guess. The problem seemed to center on those low-interest rates for long-term bonds because those low rates were abruptly going higher. In the language of the market, the "spread" between short-term and long term rates was widening or at least returning to normal. Not knowing why the spread had narrowed, no one knew why it had stopped being narrow; but it was nevertheless a clue where the problem might be centered. About a month later, rising interest rates seemed even more central when clues to many other suggested culprits had proved false. The selling concentrated on blue-chip stocks, but there was nothing the matter with blue chips. They had been sold because other markets were frozen with fear; if someone needed cash, there was nothing else the market would buy. The "quants", the traders who programmed computers to react without thinking, had merely reacted in sports jargon, to a 'head fake' in the blue chips. Meanwhile, interest rates continued to spread apart; someone big was selling a lot of long-term bonds, and was really serious about it.

|

| Alan Greenspan |

Come to think of it, if long-term interest rates were returning to normal because someone was selling bonds, then, of course, they had been too low for years because someone else was buying too many bonds. Maybe the Middle East oil barons had a hand in it, but more likely it was the Chinese government, who were known to hold a trillion dollars of U.S. Treasury bonds. Some years ago, Chairman Alan Greenspan of the Federal Reserve worried out loud that by historical standards, public markets [in this case, the Chinese government] were agreeing to accept interest rates for long term debt that seemed much too low for the risks undertaken in loaning it. Worse still, the reasons were unclear. Greenspan called it -- a conundrum. Home mortgages are long term debt, and here's maybe another clue. For political reasons, tax laws had effectively made mortgages the cheapest way to borrow. For another, the reverse mortgage, or home equity loan innovation, transformed home mortgages into the equivalent of ATM machines. A great many young people who might have been better off renting a place to live were persuaded that owning a house was essential to improving 18% credit card interest into 6% mortgages, and tax-sheltered 6% at that. Hidden in this borrowing revolution was the unrecognized temptation to maintain far less owner investment in the house that had been true in the past. It became cheaper to borrow, riskier to loan. American homebuyers were subsidized to borrow, and for whatever reason, Chinese were inclined to lend.

If interest rates go up, the value of bonds with low coupons goes down. Plenty of non-Chinese owned bonds, mainly American banks, and insurance companies. If these bonds had been purchased as long-term investments, there was no sense in selling them, and it was merely annoying that stock market prices for bank and insurance stocks dropped to reflect this lessened value of their holdings. If the banks and insurance companies merely held the bonds to maturity as they had always planned to do, bond values would return to their original price. True, there were rumors that bonds related to California and Florida real estate were in an unsound bubble. But if every one of those bonds became worthless, which was unlikely, it would only amount to $100 billion in losses. That's, of course, a lot of money, but easily absorbed by a big economy. Many of those bonds were insured, and at least half of real estate value is usually recovered in mortgage foreclosure. A lot of people would be inconvenienced by markets frozen with fear, and panic selling of various sorts would make the markets volatile. But this was mainly a liquidity crisis, roughly equivalent to a man with a $20 bill who was temporarily unable to get a candy bar out of a dispensing machine.

Supported by such talk, the stock market went down moderately but steadily. After a year, it was down two thousand points, or perhaps 15%. We seemed likely to have a recession, but periodic recessions are a healthy way to correct irrational exuberance. Most Americans do not own Florida and California real estate, don't use the banks and insurance companies in those regions, and have a reserved opinion about those who do. Somehow, it was overlooked that the very first banks to collapse in this upheaval had been in Germany, France and England.

In retrospect, in 2011 we

What's a Collateralized Debt Obligation (CDO)?

|

| CDO |

Securitized debt obligation (SDO) might be a better term than a collateralized debt obligation (CDO), but it never caught on, so the unwary easily confuse CDO with CDS, an entirely different derivative called a credit default swap. There will be a lot to say about credit-default swaps in the present financial muddle, but for now, we focus on the process of securitization. A CDO accomplishes the transformation of debts into securities, usually by aggregating a large number of similar debts (mortgages, construction loans, college tuition loans, etc) into an issue of bonds or stocks. In so doing, it goes from banking to finance. A bank deals with depositors, and it also deals with borrowers; its function is that of an intermediary between the people who have spare cash and other people who need to borrow it. Finance is one step removed from banking; the people who lend and those who borrow are often dealing with different institutions, who deal with each other or through an exchange. When the securitization process is complete, the lenders and the borrowers only begin the process at each end and most of the transactions end up in the hands of investors far removed from the original loan.

Although with more middle-men there are more fees to middle-men, securitization in the financial market's deals in large volumes and ordinarily introduces some important cost efficiencies. Instead of the expensive process of many bank branches painfully assembling a myriad of deposits in order to assemble enough to lend out a mortgage, much larger lumps can be assembled in Wall Street capital markets with little more than a phone call. It is possible to borrow wholesale from Wall Street, avoiding the expensive situation of sometimes having more money to lend than requests for loans, while someone else has more loans than cash to lend. Furthermore, the expensive risk of "borrowing short and lending long", that eternal nightmare of banks, is blunted. And the source of funds available for lending can become national, or international, rather than limited by the savings of local community surrounding the bank. Surpluses can be matched to loan requirements, another efficiency.

Unfortunately, the resulting creative destruction of bank branches creates one major offsetting disadvantage. The days are mostly long gone when bank managers would drive around and check whether mortgaged houses were painted and roofs kept in repair, but banks still usually have a better idea of the reputation and appearance of their customers than anyone in faraway Wall Street would ever have. Some method of risk assessment would have to be devised to replace the bank's eye on the client. It was devised, it was clever, and it was cheap. Unfortunately, its adequacy for the job is now in question as the CDO market chokes up. If it manages to survive this present test, it will surely replace the expensive old system and traditional banks will have a pretty hard time competing with it. Indeed, if things work out, the present colossal mess will be shrugged off as a good idea temporarily overwhelmed by its own success.

And if things don't work out, we certainly have a problem. The outcome revolves around figuring out some way to measure the risks and segregate them remotely by computer, thus replacing the local bank manager, whose job is to avoid the risks by looking at them one by one. Since at this point in the story we know in advance it didn't work, the flaw in the securitization of mortgages lies right here.

Securitization

|

| Michael Millken |

It is not fanciful to link the credit crunch of 2007 with the savings and loan problems two decades earlier. Both bubbles were related to home mortgage financing, and the first bubble turned destructive by seeking money to keep itself going. If dammed-up surpluses of the Middle East and China could be made available to American mortgage lenders, there seemed to be ample demand for them. Furthermore, while Michael Millken is mostly known for his prison sentence, he had nevertheless made an important observation. Risky mortgages were generally overpriced. That is, the aggregate extra cost of subprime defaults was appreciably less than the aggregate extra interest being charged for them. If some way could be found to make the risk premium more appropriate to the actual risk, home mortgages would get permanently cheaper, and mortgaging profits would likely be gratifying. Mortgages needed a better system for establishing appropriate interest rates, and they needed more of that underemployed wealth of the Orient. Derivatives suggested themselves as a solution for both issues.

|

| Chairman Alan Greenspan |

The unaccustomed wealth of Asia and the Persian Gulf was put under heavy pressure to migrate to America by lack of local investment opportunities but was bottled up by rudimentary banking systems in the developing world. As ways were found to get around obstacles for exporting this money, the danger increased of "asset bubbles" inflating whatever they touched, for example, the dot.com stocks in 2001. The pressure indeed needed to be deflated, but carefully. Furthermore, certain accords reached in Basle around 1982 made it even easier for banks to issue loans, while the favored tax treatment of interest from residential real estate loans directed lending to home mortgages. Indeed, the calculated cost comparison between buying a home or renting it had once remained identical for fifty years but began to diverge in 1982. By 2007, it was significantly more expensive to buy than to rent, even though many analyses suggested a housing surplus existed, particularly in California and the Southwest. While the interest-rate premise was correct, the earlier campaign against "redlining" probably did encourage loans to people who could not afford the house, and there was momentum to this idea. But the most obvious stimulus to continued high-priced home purchasing, in the face of a growing over-supply, was the momentum of abundant cheap money. To mop up a growing housing surplus, initially low "teaser" interest rates were offered for ARMs, or adjustable rate mortgages which could abruptly adjust upward after a few years. A growing problem was being set up to go over a cliff. Chairman Alan Greenspan fretted at his seat on the Federal Reserve Board that it was difficult -- a conundrum -- why market interest rates for long term borrowing did not rise enough to put a stop to this. In retrospect, it seems likely the risk premium had long been too high and was now reaching for more appropriate levels. Derivatives were the main instrument for bringing rates down, and they did it with breathtaking speed, perhaps overshooting in the process. As is often the case with innovation, the risk of failure was overemphasized, while the dangers of success received little attention.

Credit derivatives can also be viewed as a form of insurance, protecting the lender if the borrower defaults. That doesn't sound like a bad thing. True, all insurance creates a "moral hazard" that encourages risky behavior by reducing its pain. No one, it is said, washes a rental car. But in a housing surplus, the insurance protection allows banks to take more chances in marginal situations, using up the surplus. Young folk is allowed to get started in life; the poor are allowed to enjoy the American dream. Unfortunately, some will abuse the privilege by buying speculative houses in a rising market, and "flip" them. Many will buy bigger houses than their income can support. Some, who should more wisely rent because their employment prospects are not secure, will be tempted to buy. All of these considerations are wrapped up in the interest rate the lender charges, so eventually, interest rates will rise to a level that anticipates -- discounts -- them. Interest rates did not rise. The old levels of risk "premium" did not reappear.

It seems now that increased demand stimulated by derivatives was not resisted by a shrinking supply of money, with a balance maintained by the adjustment in interest prices. Indeed, a good even brilliant idea was crippled by a series of responses to the puzzling environment. Banks learned to sell pretty much any mortgage as quickly as it was created; after that, the extra risks were none of their concern. It has been suggested that banks be required to retain a portion of any loan they originate but to do so would exhaust the bank's lending capacity during a bonanza of business. Standards for a bank's lending capacity are set by the Federal Reserve, as a multiple of their retained profits or reserves. Those capacity limits had been relaxed by the Basle accords, but only on condition, the banks restricted themselves to AAA-rated loans. This will turn out to be a critical point because it put unwarranted reliance on the opinion of the rating agencies, and in any event, led to "tranches".

|

| Federal Reserve Building |

Here's how things roughly went. Investment banks learned to buy up and combine great bunches of these mortgages into a bundle. The bundle was then sliced into tranches of lesser bundles, attempting to sort out the bundles by their credit rating. Elegant mathematical formulas were brought forward which did a fairly good job of sifting the potentially weak loans away from another bundle that was largely risk-free. Those better sub-bundles, thought to warrant a AAA rating, were then sold to institutions who were restricted to them by the Basle accords but paid a lower interest return than the mortgage pool they came from. That was already an uncomfortably low rate by historical standards, now made lower. However, in view of its superior quality with default risk removed, it could be bought with borrowed money, eventually creating an adequate but leveraged return after costs. The debt was thus piled on debt, and the process repeated with exaggeration on the next lower quality tranche, the AA paper. And so on down to the lowest grade, which was thought to contain all or almost all of the default risk in the whole mortgage pool. People who bought the lowest tranche were real risk takers, experts who knew what they were doing, receiving a premium interest return to do it. Because this process was thought to create a sophisticated assessment of the true risk in the bundle, it was thought it would justify lower rates for everybody, squeezing out the unnecessary cushion of comfort. It was a plausible idea, and if it worked, it would be a brilliant one. But it had a big unrecognized flaw. It assumed that essentially all of the defaults would occur at the bottom of the pile, or possibly at the next higher level. There would be no defaults in the AAA level until all of the lower tranches had been wiped out -- an almost inconceivable economic calamity.

Ingenuity was then carried to yet another level. Credit derivatives are a form of insurance against default, but there was a more traditional form already in existence. Several so-called monoline companies offer insurance against default, backed by the enormous strength of pooled resources of a number of the largest strongest financial institutions in the world. The rating agencies assess their strength as AAA, the highest quality. Now, it was reasoned, if a tranche of mortgages rated AA by the agencies were insured by an insurance company, itself rated AAA, then the effective risk to the investor was really only AAA, or negligible. Alchemy. The lead was turned into gold. Unfortunately, when the panic finally hit, monoline insurance stock which was considered rock-solid at $80 a share, was soon selling for $15. The flaw in all this was that the rating of the bond was based on the credit rating of the borrowers. No one had supposed that people who were quite able to pay their debts would walk away from them. When home prices fell only ten or so percent, many of them fell below the cost of the borrowed-up mortgage. Instead of feeling horror at defiling their credit reputation, many of these prosperous borrowers regarded foreclosure as simply a business decision. The protection of monoline default insurance was trivialized when one of the smartest investors in the world, Warren Buffett, announced he proposed to form a company to ensure municipal bonds, and only municipal bonds, against default. Since that might strip away what had become the only profitable portion of the monoline portfolio, the prospect of such crippled companies paying housing claims would be bleak. Pseudo AAA tranches were now clearly back to being AA, and even real AAA tranches were under a cloud. All of this was not anticipated.

There remain two other questionable developments in this colorful adventure: the role of the rating agencies, and off-the-books behavior by the regulated mortgage originators.

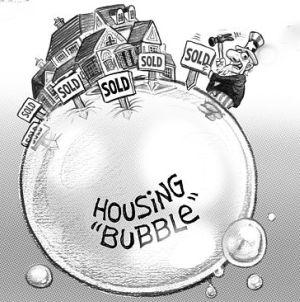

The Housing Bubble

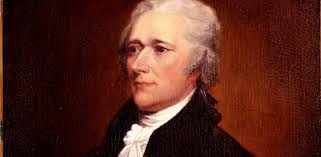

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Since ups and downs of the American economy have relentlessly followed each other since the time of Alexander Hamilton, it's unfair to blame the President who happened to be in office when each bump began; but we do it anyway. Two bubbles began during the presidency of George W. Bush, the dot-com surge then the collapse of 2001, and the housing bubble which rose from the ashes of that collapse, crashing in turn in the summer of 2007. Both episodes can be viewed as responses to the world money surplus which grew out of globalization, which itself can be viewed as growing out of the computer revolution which started around 1975. Maybe that's wrong, but it's common to believe it is right. The world economy is an over-inflated tire, so bubbles appeared at weak spots. When money fled the stock market of electronics stocks, it moved to American real estate, facing us with the choice of another bubble to follow this one unless the collapse of this bigger bubble deflates so badly we have to whimper through a depression for a couple of decades.

This grand preamble is intended to answer whether a housing surplus caused the bubble, or a money surplus did. Economists at the Federal Reserve, charged with examining such questions, are firm of the view that money surplus came first, causing too many houses to be built. The money surplus, in their view, grew out of the tendency of people (in this case, Chinese) to get prosperous before they learn how to spend their new wealth, so they save it. Without further debate, we will assume excessive savings in developing countries tended to swamp the world financial markets, and if it hadn't been this bubble it would have been some other. We went 18 years without a major recession and would have to go another two decades -- forty years, in all -- for things to work themselves out calmly. It's a pity, but that's the price of being too successful.

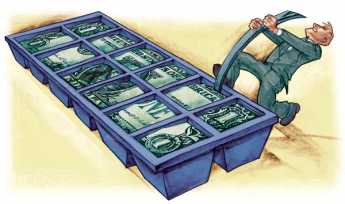

|

| Housing Bubble |

A briefer capsule of the housing bubble would describe how surplus funds in the banking system made it cheaper to lend out mortgage money, which soon led to surplus houses, which caused the prices of houses first to go up and then to go down, soon followed by the banking system, and maybe through banks to the rest of the economy. Stock speculation is easier to manage because houses take a very long time to disappear once you build them. Judging by the experience of the 1929 crash, it takes nearly twenty years for confidence to return after a bad crash, so perhaps the loss of confidence takes longer to recover than real estate prices. In fact, Europe looks as though it may take a century to recover its nerve, and by that time Europeans could be permanently in the dustbin of history. It can all be an unpleasant set of reflections.

Frozen Markets

Markets cannot clear without transparency.

|

| Vikram Pandit |

Lots of people, perhaps far too many, borrow money. Many fewer are involved in the institutional lending of money, although still quite a few; but only a handful of those few have much familiarity with the mechanics of bank panic. Meanwhile, terms of art get propelled through the news media, accepted as established fact by almost everyone but placed in a peculiar storage category. Almost everyone knew the markets froze up all over the world; almost no one could define what was meant by that.

It meant that it was suddenly impossible to buy or sell financial instruments which normally are bought and sold by the thousands every hour. Some things were more thoroughly refrigerated than others, suggesting they were possibly at the heart of the problem, and some things took longer to thaw than others. One's grandparents could relate times in the 1930s when local towns had to pay their policemen and school teachers with a script because they could not obtain currency. So frozen markets could become serious, not just a day off from school. Basketball games and election campaigns continued to dominate the news, but deep within the newspapers markets continued frigid for quite a while, ominous and mysterious ice caverns.

|

| Abby Hoffman |

Many factors contributed as causes, and perhaps the greatest causes have not even been identified a year later, but two phenomena seem to explain a lot. The first was widespread reluctance to accept current market prices as realistic because no one likes to believe money is forever lost. The validity of market-based prices carries the assumption that weight of opinion will push prices in one direction or the other; if prices go too far, opportunists will push them back. Markets don't set prices, they "discover" prices by finding the price which temporarily balances the opinions of the universe of buyers and sellers. If you were Zeus, you might chortle at how wrong they all were, but nevertheless, the consensus "discovers" the price that clears the market. What Zeus thinks has nothing to do with it. The process of orderly matching of bids can come briefly to a halt for any number of silly reasons; Abby Hoffman once paralyzed the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange by throwing dollar bills over the rail of the visitors' gallery, with a single hundred-dollar bill hidden among a lot of singles. Ramming an airplane into the building will do it longer, even for a while after the unexpected event is understood. But a lasting freeze-up is more likely to occur when the trading process unexpectedly drives all prices up or down, giving a signal that no longer is opinion equally divided, everybody is in total agreement that prices are going in a single direction, and no one, therefore, knows how high or low they are going to go. If everybody wants to sell, no one will buy.

Ordinarily, only a tiny sample of stocks or bonds are involved in daily trading, establishing a signal for what the rest --locked in banks or safe deposit vaults -- are worth. Most important are the inert securities "caught in a loan", being held as security for a loan on the presumption they are worth somewhat more than the loan. If the market abruptly decrees they are worth less than the loan, the bank will call for extra collateral, and failing that, will sell the collateral. When there are sudden runs in one direction or another, it becomes impossible to say what the collateral is worth; it's a good time to get out of the lending business if you can. Because no one dares buy, no one is able to sell; if you can't tell what the collateral is worth, no one will lend. That's pretty much what a frozen market looks like.

A variation of this concept arises when a banker refuses to sell because the emergency sale at a distressed price will "publish" a false price, which will then be applied to all of the rest of the bank's holdings, suggesting that those immense piles of securities in the vaults are really worthless. When distressed prices do surface, major banking concerns will refuse to acknowledge them as true prices. Because refusing to honor the "going price" is very disruptive, regulators force institutions to "mark to market" every day at the end of the day. If marking to market amounts to an admission of insolvency, that's unfortunate. A brokerage house forced into receivership because of obviously fallacious pricing can be even more bitter when it is recognized that commercial banks are not forced to mark to market, even with exactly the same securities. Banks are permitted to declare that securities are a long-term investment, marked on their books at the purchase price rather than the market price. Such maneuvering however gradually forces the bank out of the lending business at the same time that truly worthless paper is allowed to masquerade as sound securities. In the long run, it's bad for the economy, and in the long run, the bank goes out of business anyway, it just takes a few months longer. While this process is underway, the regulators will force weakened banks to issue more stock, thus diluting the value of the existing owners, a sort of punishment for improper management. Under the circumstances, a major incentive is created to avoid letting the world know how you stand. Transparency, as they say, suffers.

|

| Frozen Markets |

Repetitive Trading.In recent weeks, a professor at the Wharton School made a name for himself with theory with the power to become a law of the market place because of its power to explain some quirks. Repetitive trading in the financial marketplaces differs significantly from the market for used cars, say. If a single trade takes place for a high-priced item, the buyer and seller concentrate their efforts on getting that one price as favorable as they can; usually, the seller has superior information and more practice, so he sells for a profit margin over the real market price. Most customers hate this flea market. On the other hand, when two brokers make ten or twenty trades a day for months on end, they become valuable clients to each other. The value of sustaining the relationship is greater than the occasional opportunity to pull a fast one, so it becomes a fact of life that an imbalance in one direction will be compensated by a collusive imbalance in the other direction in some subsequent trade. Although an occasional customer may get a poor execution from his broker, the market as a whole is smoothed out and volatility is probably reduced. There's less stress and strain on the brokers in the middle of the trading profession, until one-day things go bang. Suddenly the value of the relationship seems quite minor compared with the potential for betting wrong in a congested market, that is, a stampede. So, such traders withdraw from the market as much as they can.

O'Neill's Parable Perhaps he oversimplified matters, but the 72nd Secretary of the Treasury of the United States certainly made a clear point about frozen markets. "Suppose," he said, "You imagine ten bottles of crystal-clear drinking water."

"Next, suppose someone suddenly announces the news that one of those bottles contains deadly poison. Nobody will buy a single one of those bottles, even though there is only a 10% chance that any one of them has poison. That's a frozen market."

What's a Derivative?

The intention of the next few sections is to sort out some of the confusing components of the credit crunch of 2007, in which novel financial instruments called derivatives played a central part. Before we get into that, let's try to answer the question just posed: why did the monetary authorities respond to a surplus of cheap credit by apparently making it worse, flooding the economy with still more cheap credit? The sudden return to normal interest levels, it would appear, posed a threat of recession so severe it seemed necessary to make inflation worse in order to combat the impending deflation. The Federal Reserve may, of course, be planning only a brief inflationary move, or a sharp inflationary move soon followed by a sharp deflationary reversal. Its purpose appears to be, to prevent an impending wave of mortgage foreclosures by holding interest rates down, disregarding the abnormally low long-term interest spreads which had recently seemed such a problem. Whatever it's tactical purposes, such bewildering reversals are a signal the Federal Reserve regards the present situation as dangerous. Some degree of inflation, possibly a large one, is going to be created but the Fed seems to think it has no choice. Before getting to that dilemma, let's sort out some of the ingredients of the credit crunch that seems to have triggered this mess.

A derivative is really pretty clever. It sorts out and monetizes any or all of the risks of a business. It frees up capital by putting a price on risks, just as insurance does, without requiring ownership of the whole company or industry. Flexibility is created, and in the case of real estate loans, surplus cash in one region can be redeployed in another region where the money is tight. Flexibility allows for an increased velocity of transactions, and increased velocity of turnover is equivalent to having more money to work with. It was not so long ago that mortgages were obtained from the local building and loan, and thus were constrained by the savings deposits of the local community. Far Eastern and Arab savings are now no longer held captive by primitive local banking systems.

There are worries about derivatives, however. For all their advantages, derivatives remain strange and mysterious, and thus, always a potential target for populist politicians. They are also a zero-sum game, which means that for everyone who makes money there must be someone else who loses exactly the same amount. That's, of course, true of debt in general; it's true of loans, and of bonds, but derivatives are new. Finally, derivatives were a quick success, which makes them dangerous competitors in the creative destruction game. It even makes them annoying to non-competitors, who get trampled by stampedes.

In the particular version of derivatives of concern in real estate, derivatives stripped away the risk that borrowers would default on their payments. That made mortgages available to more marginal borrowers, adding only a small cost for the insurance provided. It allowed more accurate, hence lower, pricing of mortgages by assessing the rate of default in a whole region rather than house by house. The theory was good and the savings to everyone were considerable. But success became a problem. No longer inhibited by a shortage of capital, mortgages and home ownership were greatly promoted. Unfortunately, the demand for mortgages in America had been artificially stimulated by implicit government protection against foreclosure, by government sponsored mortgage agencies with implicit government backup, and by the tax deductibility of mortgage interest which was denied to other forms of household borrowing. If a loan was needed, some way was sure to be devised to make it a mortgage loan.

What is an NRSRO?

Congress created the concept of a "Nationally Recognized Statistical Rating Organization" in 1976. As an aftermath of the Sarbanes Oxley movement, in 2005 credit derivatives were also required to be rated by the Credit Rating Agency Reform Act. A government stamp of approval was thus placed on a handful of rating agencies, and some argue it would be better to increase competition rather than constrain it by an approval process. Others are fearful of political influence. The rating agencies themselves have expressed concern that efforts to increase transparency will impair confidentiality, and point out the existing system has seemed to work well for a century.

|

| Atom Bomb |

Nevertheless, defaults and paralysis of the credit system did occur, made worse by over-reliance on NRSRO ratings . Very likely, increased experience with this new debt security market will lead to a more accurate correspondence between predicted default rates and actual ones. No doubt, bond underwriters will make greater effort to stratify risk within the tranches with their own resources, using the opinion of independent rating agencies more as a check. Meanwhile, there may be a need to modify prevailing approaches. When evaluating a simple bond issue for a municipality or a corporation, only the financial strength of that entity is important. With the tranching approach, however, it is possible that risk estimation within each individual tranche might be perfect, but somehow be undermined by misjudgment of risk premiums to be assigned to each tranche. When risk premiums are generally compressed, there may not be enough to go around to all of the tranches.

There are seven firms currently registered as NRSROs: * A.M. Best Company, Inc. * DBRS Ltd. * Fitch, Inc. * Japan Credit Rating Agency, Ltd. * Moody's Investors Service, Inc. * Rating and Investment Information, Inc. * Standard & Poor's Ratings Services

Debt Rating Agencies

Three years ago, a gathering of bank executives were asked if they had an understanding of derivatives; it became instantly clear they hadn't the foggiest. More recently than that, Robert Rubin no less, admitted he first heard the term, credit derivative, a year earlier. When such an innovation means thirty or more $trillions quickly, it creates opportunities for quick learners. Everybody else relies on experts. But even if you grasp the credit derivative idea quickly, its innate complexity defeats you. Thousands of loans are jumbled together, shaken, diced and sliced, sold, and reassembled in new packages. The choice was clear: a banker must either decide to stay clear of such mysteries no matter how profitable they seem or else rely on the opinion of triple-A rated agencies of long and honorable standing. A great many people decided to go with agency opinion, combined with a determination to sell these things as fast as they got them. The agencies did their best with an almost impossible task, and the sales volume soared.

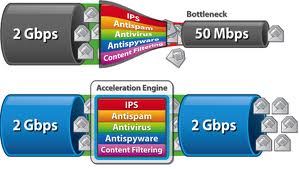

|

| bottleneck of computer |

In a computer age, such complexity can be quickly defined, traced from start to finish, evaluated in mass quantity, bringing final pricing decisions down to manageable form. But the bottleneck of computer programming limits the ability to address this rush job as quickly as its terms and direction are shifting. When computers catch up, much of this problem will come under control, without time-outs, new rules, or perplexing restraints. Meanwhile, the response emerged: keep as little inventory as you possibly can and meanwhile take a chance on the agency opinion. No doubt, other options were considered: play your cards close to your vest, position yourself to jump clear of trouble as soon as you hear of it. Billions, simply billions of dollars were to be made if you were quick and bold.

* * * * *

Naturally, this pretty crude approach becomes steadily safer as experience showed its strengths and flaws; in time it might even be replaced by an auction between counterparties, creating a market for price discovery. Or perhaps packaging firms would strengthen their own evaluations to a point where each firm's reputation could compete with the rating agencies in risk assessment. Nevertheless, the lack of feedback was crippling until computer programming caught up. Market participants demand reasonable correspondence between ratings and subsequent default rates. In the meantime, everyone flew by the seat of his pants. Unfortunately, in that meantime, everything blew up.

* * * * *

|

| Gaussian, or |

Mathematics contribute some insight into why it happened so soon. The Law of Averages forces a huge number of random opinions to assume a Gaussian, or "normal", distribution curve of rather narrow fluctuations. When opinions are constrained to a handful of rating agencies, however, volatility spread gets much wider, or "fractal". In the wry shorthand of market traders, a hundred-year probability then seems to occur every four or five years. Paradoxically, wide unexpected jolts are not caused by an increasing number of opinions, but the reverse. In investing circles it is said that the higher it goes, the more volatile it gets, and more likely to crash. "Chartist" observers notice this phenomenon in reverse; a period of declining volatility is known as a "pennant formation", often observed to precede a sudden reversal in market direction. Whether preceded by megaphones or pennants, when someone cries "Fire!" in a crowded theater, public opinions narrow down to only one -- get out the door.

What's a Mezzanine Loan?

It seems like kicks just keep getting harder to find...

|

| Paul Revere and the Raiders |

A French word for a balcony, mezzanine is derived from Italian and Latin. In architecture it describes an indoor balcony floor or elevator stop, using up spare space below the high ceiling but above the ground floor of a bank or department store. Evoking this familiar image, mezzanine has become a word to describe things which get shoe-horned into the vertical space between two other things, often as an afterthought.

In the mortgage world, the meaning you want to be careful about is a loan sandwiched between the owner's equity and the first mortgage, potentially leaving it unclear whether the "mezz" is equity or mortgage, but in fact often a warning the property buyer had to borrow to make his down payment. Persuasion efforts at the time of investor re-purchase of a mezzanine loan are apt to focus on the rich double-digit income which would result from everything going well with the loan, falling back on a cheap acquisition price for the real estate in case of a foreclosure. However, mezzanine loans are a comparatively new product, and the full range of consequences are not common knowledge. In the first place, the 2008 wave of foreclosures was not anticipated, so the risk of rich double-digit interest payments was badly underpriced. Even more important, the mezzanine loan seems somehow senior to the first mortgage, but that is meaningful only if the amount recovered from the foreclosure significantly covers the residual of the first mortgage. Even if the total acquisition cost after the foreclosure is a bargain, the big problem in 2009 has proven to be the freezing up of the financial system, with the effect that no one can be certain what the final house value will be, and consequently what the value of the mezzanine loan should be. The resulting bad name that mezzanine financing acquired in this uproar has further frozen the market with fear.

There are other definitions of a mezzanine loan in use, so the first message to investors is to make certain what meaning the term intends in a particular case. If the interest rate was underpriced, the principle of the loan was overpriced. The market will only clear when all parties reach an agreement about the degree of overpricing of the asset, the degree to which the foreclosure recovery fails to cover the first mortgage, and the risk premium needed to cover the uncertainties. Mortgage professionals will eventually puzzle all this out, but until then the existing mezzanine loans will be yet another major obstacle to the recovery of the impaired financial system.

It may or may not be helpful to understand another way of describing this puzzle. A mezzanine mortgage describes a second mortgage (by implication, a first mortgage must pre-exist), in which the security for the loan is not the structure being mortgaged, but the ownership shares of the structure held by those who pledge to repay the mezzanine mortgage. Thus, both the first mortgage and this second one can foreclose and receive nominal full value independently, rather than standing in sequence with each other to receive the same pledged asset. In this somewhat legalistic view, the mezzanine is not senior to the first mortgage, but independent of it, holding the owner's equity as security rather than the house. The legal process of foreclosure is facilitated, even though the recovery may not differ much.

In recent years, however, the term has also been used to describe a second round of tranches in a securitized pool of mortgages. This is the view that emerges from trying to price a layer in the middle by disregarding the bottom of the heap which is hopelessly lost, as well as the top of the heap which is safe and sound. After first slicing away the best grade of mortgages, the residual middle-grade bundle still contains differing levels of risk, and the top grade of a second sorting process can be skimmed off as enough better than the rest to qualify as value overlooked. When this salvaged subgroup is then insured by a ("monoline") insurance company which itself has a AAA rating, it can be claimed the salvaged bundle has effectively upgraded from, say, AA to AAA. Obviously, the validity of this financial alchemy depends on accurately down-grading the dross left behind. The most important misjudgment in this mezzanine process, however, was the unexpected undermining of market opinion about the insurance companies standing behind it. Many of them retained a AAA rating, while their stock lost 75% or more of its market value.

Language moves fast on Wall Street, particularly when a new concept needs to be packaged in a sales environment. Within a few months, mezzanine financing in common parlance quickly came to mean Alt-A. And Alt-A came to be defined as a mortgage or a package of mortgages in which the borrower was neither asked his income nor asked to prove it if the matter was challenged. That may not be exactly accurate when referring to any particular security, or package of securitized debt. But in common parlance, Alt-A was the term used when someone described mortgages where the lender knew very little about the borrower.

Having a general sense of the uncertainties, the general reader may perceive why this issue freezes up the market, and someday may be ornamental to explaining it all to one's grandchildren. But that's about all; most people become glassy-eyed, and start to run away.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

Inverted Yield Curve: The Depositors' Viewpoint

Much has been made of risks for giant creditors in the 2007 credit crunch. What about the little creditors, the depositors with their savings at stake?

|

An old friend, than over ninety years old, once growled that Paul Volcker, the esteemed even heroic Chairman of the Federal Reserve, was only interested in saving "the banks". It's certainly true that many members of that board are elected by banks in the different regions, but it isn't easy to see how the Chairman could help banks if he wanted to, or why he would want to. It takes only a moment of reflection to realize, however, that all banks would naturally want to charge the highest possible interest for their loans and pay the lowest possible interest to depositors. Essentially, everybody is their adversary.

Except the Federal Reserve, which needs its regulatory power over banks to control the amount of money in circulation, in order to stabilize the currency both at home and abroad. In another place, we discuss the remarkable ingenuity and the worrisome weaknesses of this arrangement, but for now, let it suffice that it's the arrangement we have.

The difference between the prevailing return on deposits and the return on loans is called the yield curve, because short term rates, which the Federal Reserve controls, normally slope upward toward higher long term rates, which the Federal Reserve does not control. Essentially, the Fed controls what depositors are paid, but has no direct control over what borrowers are charged. Depositors are savers, and it is widely agreed that Americans do not save enough. To some degree, that must be the fault of the Federal Reserve. And when market conditions force a decline in the rates charged borrowers, the Federal Reserve must allow the banks to squeeze the depositors' rate of return, or banks will go bust. That's all my old friend was trying to say when he criticized a national hero. Luckily for Volcker's reputational legacy, he needed to boost interest rates dramatically in order to stop inflation, and that put plenty of interest in the pockets of old folks with money in bank deposits, while unfortunately, it throttled borrowers unable to obtain loans except at very high prices. He stopped inflation in its tracks, but at the price of hurting business.

For over a year before the 2007 credit crunch, short-term rates (and depositors' interest return) were higher than long term rates (and borrowers' interest cost), an infrequent occurrence called an inverted yield curve. The difference between the Bernanke problem and the Volcker problem was that this time long rates were stuck at historically low levels, probably because of international situations. Depositors were protected and banks were made to suffer, although their reserves were invisibly eroding. One has to suspect the housing bubble was allowed to go on, to some degree to rescue the banks. With inflation starting to appear, interest rates needed to be raised, and with a national election approaching, deposit returns needed to rise to placate elderly savers. Furthermore, banks had a relatively new competitor for deposits, the money market funds.

The inverted yield curve put savers in a strange position. Normally, they had to balance in their minds the higher interest rates obtainable by investing in bonds, against the inflexibility of locking up the money for long periods. With an inverted curve, however, bonds looked like the dumbest possible investment when they paid less interest than money market funds. Bonds were thus under pressure to raise rates, but they didn't rise. Greenspan's conundrum still persisted, but the situation highlighted one of the unpleasant consequences of correcting it. If interest rates rise, the price of existing bonds must go down; somebody's going to lose money. That's what was soon going to happen, once the credit collapse got started. Bond prices might dip and return if you didn't actually sell, but if you urgently needed cash in the meantime, you had to call on your money market savings. The spreading of the problem from one asset class to another was likened to the spread of a contagion.

In a sense, that's isn't quite accurate, because the similarity of bank deposits and money market funds is to some extent an illusion. Money market funds are minibonds. These bundles share the characteristic with bonds that rising interest payments result in falling prices for the principal involved. To preserve the appearance of interest-bearing cash they have a par value of a dollar a share, and the interest they pay is really a dividend. To preserve the appearance further, when interest rates must rise, fund owners make strenuous efforts to avoid "breaking the buck", or lowering the principal value, even to the extent of investing their own money to support the price. Rising interest rates are hard on money market funds, and most funds are owned by banks. The banks are under pressure by other factors in the credit squeeze, so it would not be inconceivable that they would be forced to break the buck. Elderly savers would not like that development and in an election year could make their displeasure felt. A great many people might wish to shift their savings from money market funds back to bank deposits, which are largely insured. A commotion of this sort would bring more attention to a comparison of different funds, leading to the wide-spread discovery that the money market funds, which stock brokerage accounts employ as "sweep" funds for dividends and spare cash, have long paid substandard interest rates because of ignorance and inertia by the clients. And so, the contagion threatens to spread further.

Murky Crisis

One of the Wall Street's better maxims advises: Never let your competitors smell blood. Talking too much injures honorable firms because in business there is usually a vulnerable moment before opportunities can be consolidated, or miscalculations corrected. Innovation by trial and error is progress. Transparency, humbug.

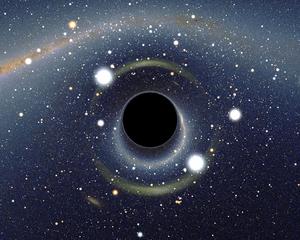

|

| Black Hole |

This prevailing wisdom can lead to mysteries where informed professionals puzzle through dramatic events, yet after six months remain unsure how bad things really are. When the subprime credit crisis began in August 2007, the average size and total number of outstanding mortgages was approximated, and from that it appeared impossible for overall losses to exceed $90 billion. Six months later, write-offs at least that large had been declared, but estimated future losses then ranged around $600 billion, give or take $300 billion. But wait, in a zero-sum game, winners must match losers so the economy as a whole should remain unchanged. Even if winners and losers are in different nations, the result would at worst be a weakening of one currency and strengthening of the other; after which world-wide wealth would remain unchanged. Real worldwide losses in a crash related to whether wealth is created or destroyed, not whether it has been transferred from one firm to another. As an aside, the supply-side viewpoint is that taxes effectively remove wealth from the private sector for protracted periods and therefore are equivalent to dropping into a black hole; but liberals mostly dispute this, so it is not discussed here.

One of the indisputable ways to expand or contract wealth is, unexpectedly, through a change in prevailing interest rates. When interest rates rise or fall, the value of debt or bonds goes in the opposite direction. So, when derivatives or other efficiencies lower interest rates, wealth is created. When realism, panic -- or fear of inflation -- cause interest rates to rise, wealth gets destroyed. What matters most to individuals is whether they own bonds during the time when interest rates are changing. No one necessarily gets any richer; in an inflation, bondholders lose money because money truly disappears.

So recently, spreads widened, or the risk premium returned to historic levels, or subprime mortgages got more expensive, or six other ways of saying the same thing: interest rates went up, value was destroyed. Anyone holding a certain kind of bond lost money, may not be able to pay his bills, so don't lend to him. Because the problem was large and worldwide, no one could be sure who was holding the bag, transactions stopped, the credit market "froze up". Some very prominent firms soon declared losses of $5-10 billion each, so anyone might be an unsafe counterparty. Even if time passed and other firms did not declare losses, general distrust persisted, for a complex reason having to do with mark-to-market.

A Wall Street broker is required to readjust his portfolio worth to market prices, every day. Active traders, trying to keep as little inventory as possible, constantly face the possibility of imbalances, temporary cash shortages, which would make them unable to pay bills even though they had spent nothing. Therefore, when interest rates go up, Wall Street investment firms lose a lot of money on the underlying bonds in their hands and must declare so publicly. Firms hate it because it could well trigger margin calls from their lenders. If no shares are traded, however, the price of the shares appears to retain the price of the last trade. That's what is often meant by markets "freezing up"; if no one registers a sale at a lower price, it can't be meaningfully "marked to market." Banks, by stark contrast, are allowed to play by different rules. When the value of their bonds or other securities goes down, the accounting rules permit them to declare the bonds are a long-term investment, where they do not need to be marked to market. Investment banks thus must declare huge losses when they haven't sold anything, while commercial banks may hold exactly the same portfolio and declare no loss at all. Whether this disparity is wise or unwise, is entirely beside the present point. The disparity confounds the general inability to say who is in trouble, thus whether the economy is in dire straits or just experiencing a state of confusion. At the least, it makes banks appear to be solid and solvent, while other investment institutions may appear to be in worse trouble. Aside from investors losing money by making wrong choices, there is a political risk in an election year that Congress or regulators could make wrong choices. A reckless young French trader happened to underline this risk, quite pointedly.

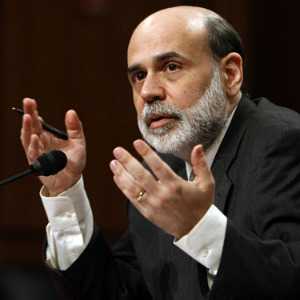

America was having a bank holiday on Martin Luther King's birthday, so American financial markets were closed but European markets were open. While American traders sat helplessly at home watching the news, European stock markets abruptly collapsed on heavy selling. Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke promptly dropped short-term interest rates by seventy-five basis points (0.75%) between meetings of his board, creating a panic situation the next morning. It seems in retrospect that he had not been informed that a rogue trader at a prominent French bank had obligated that bank for $75 billion of unauthorized positions, which bank authorities promptly liquidated at a $7 billion loss soon after they discovered it. The newsmedia concentrated on the racy story of a French scalawag, but there was a more important story. Because of bewildering financial convulsions whose full dimensions may not be known for another year, Ben Bernanke the financially best-informed person in the World got into a panic and made a choice he might not have made if he had the full facts. If that was the case, poor intergovernment communication unnecessarily gave us a dose of inflation to contend with. Or, perhaps Bernanke got a needed wake-up call that the economy risks getting tangled up for several years from banks trying to ride out their bond portfolios to maturity instead of making loans. Refusing to acknowledge losses is what gave Japan a recession which is now in its fifteenth year. Try this nightmare: if the American consumer quits buying imported goods, Japan then China could collapse with consequences beyond conjecture. It is impossible to imagine Congress restraining itself in such a mess, and nearly impossible to imagine their getting it right when they do act.

As if to illustrate the point, the Carlyle Capital collapse in March 2008 demonstrated how violently markets can now be roiled by even a small quirk in the banking system when huge volumes of money are propelled through it, by ultra-fast computers before the rest of the financial world wakes up. A prudent banker would normally make a loan for appreciably less than the value of the collateral. Depending on the historical volatility of the collateral, it might be reasonable to lend 80%. But Carlyle was an investment fund, selling shares to the public worth several hundred million dollars. Borrowing $20 billion from banks, especially Deutchebank, Carlyle bought mortgage-backed securities. Before things collapsed, Carlyle had bought $21 billion of real estate loans but had received only a twentieth of that in payments from investors. The market price of the secutities thus only had to fall by 3% before the whole structure became insolvent. In the conventional 80% collateral example, a 3% decline would still have left it with a 17% cushion. Extreme leverage of this new ultra-fast sort would probably never have been considered by the German bank if it related directly to mortgages without a complicated middle-man. Whether anyone at the German bank realized this transaction was substantially the same thing at 20 times the risk is presently unknown, but it seems doubtful. The fact that at a relatively quiet moment DB suddenly called back its loan suggests that someone at the bank finally did wake up and ordered an end to the arrangement. Congress can now pass a law forbidding such structures if it wishes, but that will be mere grandstanding. Future textbooks of banking practice will surely all riducule the absurdity of this transaction. The risk of it nearly vanishes however at the moment of widespread recognition for what it is. Far worse would be for Congress to pass pious laws which essentially say that nothing innovative must ever happen for the first time, or that banks must stop using high-speed computers.

We must not conclude this little history lesson without stressing its basic point. When huge amounts of money seemed to disappear from the system, the only explanation available was that interest rates had suddenly gone up, resulting in existing bond prices going down. If so, central banking chairmen could make money re-appear by forcing interest rates down and holding them down. Conceivably, some other explanation for the vanishing money might more precise. But even so, forcing interest rates down ought to make money re-appear. This very simple description of events has been characterized as a "revival of Keynes-ism" , although most of us were accustomed to other descriptions of what Keynes attempted in the depression of the '30s. Nevertheless, it accurately capsulizes what Ben Bernanke about did in this one.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

At Third and Chestnut Streets in Philadelphia there is a Japanese restaurant occupying the site where Alexander Hamilton once lived and devised the modern banking system. There's no historical marker, possibly because Hamilton's involvement in the Whiskey Rebellion and his political switch of the nation's capital from Philadelphia to the District of Columbia made his memory distasteful to local town fathers. It was at this place Hamilton devised the idea that what America needed most was a national debt -- national debt was a national treasure. Just about everyone was appalled, especially Thomas Jefferson and Albert Gallatin. George Washington didn't know about such things, but he trusted Hamilton and so we got a sovereign debt as a cornerstone of national finance because no one wanted to oppose Washington. Wrangling over this radical idea became a central issue in the next eight presidential elections. After that, we had a century of wrestling with substituting the Federal Reserve for precious metals as a way of controlling the money supply. In a more sophisticated form, our sovereign debt now forms the bedrock basis for the Federal Reserve's control of the banks and the monetary system. Just when things seemed settled, we confront something new and possibly just as revolutionary, the sovereign-wealth fund.

->If a country can have debt, it can have a surplus. Using that surplus to buy corporations was seen as nationalization, just a way- station on the road to socialism or communism. Somehow, what to do with national surpluses never became an issue, probably because it was easier to spend than to save. More recently, surplus funds have fallen to governments from oil or other natural resource discoveries, usually soon in the hands of a despot, combined with rudimentary banking systems that make it hard to invest locally. In 2008 these accumulations worldwide are estimated to exceed $3 trillion. Dubai has about $600 billion, and other countries like Singapore are not far behind. Traditionally, such funds end up in places like Switzerland where they more or less disappear from sight. While a few small countries have experimented with openly investing in stocks and bonds, the matter only surfaced as a real issue after the subprime mortgage mess of 2007. As a consequence of upheavals whose full nature is still obscure, financial giants like Citicorp, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley found themselves facing liquidation unless they could acquire billions of dollars by selling large blocks of their stock in a hurry. Thus the Americans, who would never contemplate their own government buying controlling shares of leading American corporations -- were jolted to see we had made foreign powers welcome to do so.

Furthermore, this might quickly get out of hand. The Chinese government, unashamedly communist, now holds 70% of American government bonds. Not only would a rapid bond liquidation be disruptive, but the purchase of corporations' controlling stock might be worse, The effective conversion of Wall Street into a street in Chinatown would have highly destabilizing consequences. Since holding vast quantities of bonds has created no problem, it would seem the main international difficulty lies in the voting power of common stock ownership. It might seem possible to prohibit sovereign foreign states from voting their proxies, although it is easy to imagine circumvention by straw-men. A more promising way to sterilize the voting power would be to forbid direct foreign nation ownership except through index funds. One questionable feature of this approach lies in the narrowing minority control which is created as index funds keep growing to a size that disenfranchises almost everybody except the management of corporations, or encourages predatory raids on a small sliver of outstanding listed stocks by promising future golden parachutes to CEOs and others who acquire stock by incentive options and then join in the raid.

Finally, it merits rumination about the growing vulnerability of banks, as agents of the Federal Reserve in its duty to stabilize the currency. The recent credit crunch delivered a setback to the securitization of debt, it is true, but nevertheless, the trend of several decades has been to weaken local banking. The eventual disappearance of banks is not inconceivable. Banks have consolidated into larger banking giants, but the recent troubles of Citicorp show that mega banking does not defend banks from securitization. We have to hope the Federal Reserve is considering responses to this threat to monetary management which are more productive than just a bunker mentality.

Credit Crunch Turning Point, at Eight Months?

Ever since financial markets got jittery in August 2007, pundits generally agreed that things would not settle down before the second half of 2008. That seems to have been a safe thing to predict, but not exactly the same as confidently predicting that things will change for the better in the summer of 2008. Things could, unfortunately, get a lot worse.

Let's try to predict how history will remember these puzzling times. So far, the problem has been an American home real estate matter; America built too many houses, particularly in Florida and the West Coast. Houses were built because they could be sold, so the source of the difficulty was cheap credit for mortgages, and that was, in turn, traceable to Arabian oil prices and Far Eastern industrial progress. But never mind the cause, the event was a domestic American home mortgage issue, with the rest of the world sort of looking on. Whenever America got its mortgages straightened out, the crisis would be over. The other way history may describe things is far more ominous. Prosperity for the Middle and Far Eastern countries generated more wealth than their primitive banking systems could manage, so they exported it in the form of world inflation. America was pioneering in some innovative credit and investment streamlining, which was not entirely rationalized when it suddenly got toppled by a tsunami of world credit excess. Wall Street and Washington were the actors in stage center, but the underlying problem was a world problem, taking years to correct, and requiring heroic efforts to save it. If it could be saved. Politicians and news media will emphasize any mistakes, but a solution will depend on whether or not we get some bold successes. The second quarter of 2008 will begin to show whether we need to keep cool or blow the bugle.

To some extent, it was necessary to wait the better part of a year to see how strong our beleaguered institutions would prove to be, how many of the dubious mortgages would actually default, how many of the innovative lending practices would have to be forbidden, or revised. For example, it unnerved many people that so many "subprime" mortgages defaulted in the first year after the house was bought, suggesting that the house purchase was wildly inappropriate. On examination, however, it turned out that overzealous lenders had skipped the normal practice of insisting that money be set aside in escrow for tax and insurance payments. When tax and insurance collectors demanded immediate payment, the borrowers just skipped payments on the mortgage. Lenders will probably avoid this trap in the future, but if not, legal prohibition is fairly simple because it is so obvious. However painful this small problem may prove to be, its correction will be soon forgotten.

|

| Paul Volcker |

The international issues are much more difficult. From August 2007 to April 2008, American interest rates went steadily down; by their standards, they went down a lot. Many hot money investors took this as a sign that America was going to pay off its debts by deliberately provoking inflation; European countries have done this for centuries, even including England under Sir Stafford Cripps. That's why the gnomes of Switzerland keep vaults full of gold, and the oil moguls of OPEC have learned to keep their oil in the ground. Indian women bought more gold bracelets to jangle around, and the Australian markets went through the roof. Two governors of the Federal Reserve, including Philadelphia's own, voted against lowering interest rates "at this time". Paul Volcker, who once smashed the economy in order to smash inflation, hasn't spoken out yet, but simply trotting him out to a banquet is sufficiently vocal testimony at this stage of matters. No one has yet mentioned the hyperinflation episode of the Weimar Republic, but that episode was so catastrophic no one has to mention it in Germany or Austria; everybody remembers. As a matter of fact, the Europeans are so concerned to show the euro is strong, it is actually excessively strong and will surely be moderated. Our strongest ally in this Kabuki dance has been China, but a few rash words about Taiwan would test that severely. Are we trying to inflate away our mortgage debts -- absolutely not. Will we be able to prevent a serious recession by "stimulating" the economy -- it remains to be seen.

And finally, will war, elections, blunders or general jitteriness force us all into a general rearrangement of the currency systems of the whole world, another Bretton Woods Conference let's say? No, of course not. But it wouldn't hurt to have the graduate students in Economics departments perform a few theoretical exercises, just for the practice of it.

Job Loss Map

Financial Meltdown Documentary

Philadelphia City Controller

|

| Alan Butkovitz |

The Right Angle club was pleased to hear the City Controller, Alan Butkovitz, give us an insider's view of the municipal finances, but was a little startled to hear how badly the national banking crisis has affected our city. While of course the city does a lot of things, its present finances can be summarized as mainly consisting of two things: the pension system and the management of police/fire/corrections.

Mayors of this city for several decades have been following the national pattern of government to transfer its deficits to the pension funds of the employees. That has the effect of shifting the cost of present operations into the far future and avoiding present confrontations by promising even more generous pension benefits in the future. Over time, the future gets closer and closer; to a large degree, it is right now. Pension funds are largely independent organizations, supposedly receiving current contributions to be invested for future distribution. That requires an assumption about how much investment growth will be achieved in the meantime, now set by the Philadelphia Board of Pensions at 9%. That's not impossible to achieve in some medium-term intervals. But it's optimistic, even inconceivable, for long-haul investing; over periods of thirty or more years, most experts say that 4% is about all anyone gets. More to the point, 9% is particularly unachievable right now, in the present crash of national financial markets. That's bad enough, but repeated shortfalls in contributions to the fund have left it funded at 53% of the calculated requirement to pay the pensions of the future, even using the unrealistic 9% return assumption. A few years ago, Mayor Rendell worried about the underfunding and brought it up to 70% with a billion-dollar bond issue. Unfortunately, the crash in the markets has brought it right back down to 53% again. So, it's fair to say the pension fund is a couple of billion dollars short, even if you accept a 9% income accumulation -- which you probably can't, but at least it brings the pension fund to 70% funding in forty years. Call it four billion dollars short, just to be conservative, since it is presently admitted to being two billion. That isn't Mayor Nutter's fault, but it's sure his problem; and if it gets worse, it will be seen as his fault.

The other expense item of note includes 42% of the budget in the police, fire and prisons systems (education is handled separately through the school board). If you fired all those people, or they quit, we wouldn't have a city, we would have a jungle. But the Controller describes all three as terribly mismanaged, with the local police stations in a deplorable state of disrepair and degradation, bathrooms you wouldn't think of using, and so on. The fire department has only a minor number of fires to fight, perhaps four or five hundred a year, but it includes the emergency rescue services which respond to a couple hundred thousand calls a year. The rescue people report to the firemen, and there is social friction between the two, working to the disadvantage of rescue. It costs about $500 to respond to a call, and it isn't entirely satisfactory to send a fire truck to help someone with a heart attack. The Controller had a number of horror stories about administrative mismanagement in this area. As far as prisons go, everybody knows prisons are bad places, and ours are no exception. Confrontation with the unions is definitely in the future for the Mayor, and the city is going to be in pretty bad shape if he doesn't win some arguments.

That's the expense side of the municipal budget; the revenue side is equally gloomy. The offhand comment was that real estate taxes could double without bringing the pension system under control for twenty years. If our taxes are significantly higher than neighboring cities, or even just the same as in cities with superior uniformed services, it will be hard to attract and hold business taxpayers, causing municipal finance to spiral downward. Along the course of this patter-song, it isn't exactly reassuring to learn that it now takes the City 21 days to process a check and that absenteeism in some departments runs to 20%. We've heard a lot of denunciation of Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg in New York, but their absenteeism runs 3% because investigators are sent to the house of an absentee, who is subject to court martial if he isn't home.

Somewhere in this nightmare lurks the hidden migration of the unionized workers. Starting with Mayor Rizzo or even earlier, the uniformed services were the main political support of the Democrat political machine. Quietly, they have moved out to the suburbs where the schools are better and the taxes are lower, and it is now said that 70% of union workers live (and vote) outside the city limits. The unions talk tough, bluffing through the uncertainty when their members can no longer provide the votes to be so fearsome. To some degree, their weakening political power is augmented by using their pension funds to provide construction loans for new commercial real estate. Some of that political clout is used up by the need to get zoning variances and tax abatements for the projects. A lot of these power shifts are hard to assess from the outside, but a trend is clear.

The controller didn't mention it, but the city is not only a pension investor in bonds but also an issue. Interest rates are about as low as they can get while the Federal funds rate is nearly zero, so there is only one direction they can go in the future -- sooner or later they will go up. By the iron law of bond financing, the value of the underlying principle will then go down. That could provide an opportunity to buy them back at lower prices, or it could break the city's financial back financing higher interest payments. However, for the pension fund side of things, exactly the opposite is true. Maybe Hizzoner can tap-dance around these dangers and opportunities, but most mayors would have trouble pronouncing the words.

It's part of the job description for the controller to be a pessimist. But the most you can make of this mournful dirge is to hope he is completely wrong.

Oriental Money

|

| Yuan |