2 Volumes

BANKS REDEFINED

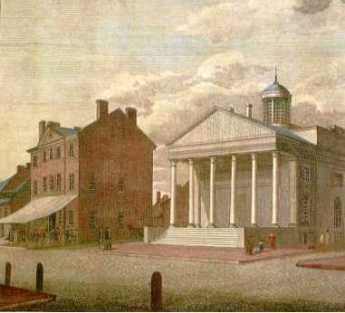

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Personal Finance

The rules of financial health are simple, but remarkably hard to follow. Be frugal in order to save, use your savings to buy the whole market not parts of it, if this system ain't broke, don't fix it. And don't underestimate your longevity.

It just frenzied Benjamin Franklin to meet young people who couldn't, wouldn't, didn't appreciate the power of compound interest. Money invested at 10% doubles every seven years. Everybody is born with the likelihood of twelve doublings. Two, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048, 4096. Your penny at birth could turn into forty dollars at your funeral, unless you never save a penny until time has gone past. If you delay saving until you are in your thirties, just chop off the four biggest right-hand numbers in the sequence; you will save $1.28. Not bad, but you missed the really big opportunities, and can never get them back. As a practical matter, your parents have to get you started as very small children.

Whenever you do grow up and get started, there are goblins hiding behind the trees. Taxes and inflation are provided by your government, maybe wars, too. Your schoolmate chums will offer you life insurance, professional investing advice, brokerage fees, pump and dump of one variety or another. But, but. If you just buy a broadly balanced world index fund and hold it like grim death, you'll probably do very well and you won't need to know what's wrong with every other thing you could have bought but didn't. That will put you ahead of 95% of the public without much effort; going for that last 5% is hard work, risky, and too complicated for people without special training. Getting rich slowly isn't good enough for some people, so in this series we will emit a short snarl about each of the other temptations you will likely experience. Saying negative things is disagreeable, but everyone must at least have some road signs about treacherous patches along the journey. In general, males in our society need to be told what to watch out for, females just want to know where to go.

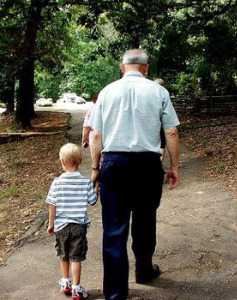

And finally, if you select a time to retire with enough to live on, you better be certain you are right about that. The miracles of modern American medicine have extended life expectancy by an extra three years every ten. That's thirteen years for the price of ten, except that the accumulated years are all piled up as retirement years. The whole baby boomer generation got caught by the wonderful experience of longevity, and it's a problem knowing how to finance their twenty-year vacation after they quit working. That may be a one-time event, but don't count on it. There is absolutely no way to get out of that situation, which can only be fully recognized at the end of your working life, except by staying at work several years longer than all your friends agree is fair.

So, you have to save and invest more than you really think you are ever going to need. Because if you don't save at least 50% more than everyone else you know, you may very well not have enough, and fairness won't mean a great deal. And that brings us to estate planning.

You'll hear people say they want to spend their last dime with their last breath, but it's pretty hard to recollect anyone who ever did that. You've got to save more than you think you need, hope to goodness it will let you scrape by, and then do some estate planning to cope with possible left-overs.

Investing for Children

|

| Many a Mickle Makes a Muckle |

There are three major expenses for an average American lifetime. Paying for college, buying a house, and providing for retirement. Unless there is a substantial inheritance, all three of these expenses must be provided for during the four decades from college graduation to retirement. Even in affluent families during prosperous times, that is almost too much burden to carry. Improved longevity leads to longer retirements, depleting family reserves which might have been transferred to grandchildren for their expensive educations. Even families which can afford it, find the legal climate unhelpful. Money given to a grandchild at birth has twenty years to grow, at least tripling before college entrance, but it proves remarkably difficult to take advantage of this opportunity.

It is obviously dangerous to allow children to choose how to spend their own money. They will not merely squander money on trinkets, there are automobiles, illegal drugs, and unwise marriages to consider. A law called the uniform gifts to minors act addresses this issue fairly well, placing assets in the hands of a custodian until the child is nineteen. That's the right idea, but nineteen is too young for many who go on to college, and it would be a blessing if the money in these custodial accounts could be frozen until college bills, if any, have been paid.

|

| Trust Funds |

A concept known as the Clifford Trust was created, allowing income from a sum of money to go to minor children (at their lower income tax rates) and then after a minimum of ten years the principal reverts to the donor. That was well intended, but it created a mountain of burdensome paperwork, legal and accounting fees. The Internal Revenue Service probably has very good reason to be suspicious of arrangements for children which primarily cloak tax evasions by their relatives. Nevertheless, the great majority of honest parents trying to pay for college are hounded and hassled in order to prevent a smaller number from cheating. Our lawmakers ought to be able to do better than this.

It was once possible to buy tax-free municipal bonds without coupons --so-called zero coupon bonds, or strips-- which could be put in a safe deposit box and forgotten until college admission time. Unfortunately, the law was changed to require yearly taxes on "virtual" income, and much ado was made of the concealment of personal property from the awareness of the infant owners.

|

| Until Death Do Us Part |

Trust funds are expensive to construct and maintain, and taxed at a fixed high tax bracket, often higher than the parents are paying. While college tuition bills are crushing, they are not large enough to make it economical to use ordinary trust funds to sustain them for a few years of concern. As the economy grows steadily more prosperous, more people will face these problems, and sympathy may grow to the point of congressional action. Unfortunately, the families who do not have college problems to finance are an envy obstacle in the eyes of elected officials, and the fairness argument is rehearsed.

Meanwhile, a single share of Berkshire Hathaway stock would pay for college, would probably triple in value from birth to graduation, generating no taxes in the meantime. The problem obviously is to afford that single share when the baby is born, but possibly a sort of mortgage could be devised. There should be more securities like Berkshire Hathaway; long life to its all-too-mortal master, Warren Buffett.

The Coming Baby Boomer Retirement Problem

In a few years, the baby boomers will retire and two things will happen. They will have to retire later in life, and the country will have to borrow money to pay for the rest.

|

In 2004, the Nobel Prize in economics was shared by Edward C. Prescott and Finn E. Kydland, for advancing the concept that business cycles are caused as much by what people expect to happen as by what actually does happen. By this reasoning, myriads of individual decisions are constantly made in the direction suggested by simple undeniable truths. What truths face us? Demographic facts related to how many people have already been born, and how fast they are dying, force everyone to acknowledge that both Social Security and Medicare are seriously underfunded. Consequently, it seems inescapable that the boomers must work longer and retire later. To whatever degree they don't, the country must go deeper into debt.

Prescott, writing in the December, 2006 Wall Street Journal, stated this truism slightly differently to reach the next step: the national debt must increase. Increasing the national debt raises interest rates, which is good for savers. At the moment, the main savers are American retirees and foreign governments. However, the bond market is and always has been a zero-sum game. What's good for American retirees is bad for American business. And mortgage-holders. And everyone else who is in debt. Higher interest rates, which are seemingly inevitable, encourage saving and discourage borrowing. Prescott seemingly welcomes those features, because he is remarkably cheerful about the inevitable coming demographic crunch.

There are at least two things about it which should be bothersome. The first is that the boomers will not be borrowing money from their own generation but from their children. Getting the chance to live longer than their parents, they seemingly want to retire at the same age or earlier, asking their children to pay for the unearned twenty-year vacation. Boomers simply must be shamed into later retirements. The American Gross Domestic Product has a long term growth rate of about 3% per year; 2% of that total comes from increased productivity, about 1% from population growth. Extending domestic working years has the same economic effect as, say, illegal immigration; it's good for the whole country to make this nativist substitution.

The other disturbing consequence of borrowing our way out of debt is the effect on banks. That's harder to explain, but the interest rates we have been describing are long-term rates, established by the world marketplace. Short-term rates are independently set by the Federal Reserve to control (or "target") inflation, and currently they are higher than market-set long term rates. Any sensible saver will therefore use moneymarket funds rather than buy bonds. That's mostly bad for banks because their profit largely derives from "borrowing short and lending long". The so-called inverted yield curve, then, is good for old folks and bad for banks. If the Treasury fails to issue enough long term bond debt, or the Federal Reserve fails to issue enough short-term debt, banks are in danger of going broke. To summarize the whole puzzle, the government clearly will become more deeply indebted, but it must preserve a proper balance between short-term and long-term borrowing. Otherwise, either a bank crisis or inflation will sink us.

As a guess, I would say that banks are the likeliest to fail. They are in precarious condition anyway because of wrenching changes in technology. And they are in the process of discrediting themselves by failing to pass along the currently soaring short-term rate bonanza to the public. Just compare your own money-market interest rate with the 5.25% which the Federal Reserve has dumped on the banking system, and see if your blood doesn't boil a little. If this pick-pocketing continues much longer, banks will be in a bad public relations position when they must come to the public with hat in hand.

So, there's only one defensible response to this demographic retirement problem. The baby boomers, having been handed several years of unexpected longevity, must spend a portion of it working longer.

Default Investing

Busy people with growing families have little time for investing but will find their retirement crippled if they neglect it

|

| Dr. Fisher |

Young people with busy careers and growing families have no time to learn the complex, constantly changing, and cut-throat world of active investment. What is described here is a formula for achieving lifetime growth of savings which is superior to what 90% of the population achieves. Its principles are simple: buy and hold will avoid transaction fees, and minimize taxes. Young people may not realize it, but taxes will eventually become their largest expense, and financial professionals value their services very generously indeed.

So, if you are going to buy, hold, and forget about it, you need to pick things whose value will persist for up to seventy years. That's not big stocks or little ones, familiar stocks or obscure ones. Only one stock, General Electric, remained listed on the Dow Jones Industrials for a century, while every other stock had its day and eventually either died or withered; that will probably also happen to GE. No, the investment which will last forever, never need to be sold, is the whole world economy. Because of computers, it is now simple to sell securities which represent a small piece of everything in the world. If one company eats another, well, you own them both. This approach will guarantee you an average success, half of the world will do better, half will do worse in good times and bad. But by minimizing fees and transaction costs, and minimizing taxes, you will do better than average. In fact, you will do better than 90% of people do, you will sleep better, never be bothered by telephone salesmen, never be cheated by people who never give a sucker an even break, never be in a panic about the stock market or the economy, and have more time for your business and family. True, you may have less to talk about at cocktail parties, but tortoise and snail is the motto.

Default investing is an important part of this. There's a lot of hesitation involved in accumulating cash savings and then stalling around choosing something permanent to invest in. That generates a lot of idle money, which creates a temptation for useless consumption, while the economy sails away from you, about one percent a month. Get the money into the world index fund, and then withdraw the cash you need for living expenses. Whether you realize it or not, you are creating a "bogey". That's slang for a benchmark. Go ahead, withdraw some money from the bogey and buy something better, but leave enough in the bogey to warn you that what you bought wasn't as good as leaving the money alone in the bogey. After a while, you will sell the loser and have learned a hard lesson. On the other hand, if you beat the bogey, that's just wonderful, but now you have the problem of when to sell this wonderful thing. Never, never, never sell it sooner than a year after you bought it because the extra taxes will kill you. When you do sell it, calculate your gain after taxes, and be sure to match up with the losers. If you are beating the bogey, you are likely to be in the top 5% of the investing world, and then maybe you are in the wrong business without any training for the new one you have chosen.

You are likely to hear talk about re-balancing. If you picked something which soared in value, your portfolio becomes unbalanced and you are taking some unexpected risks with having too much of a certain kind of thing. You will hear it said that you should re-balance by selling some of the good stuff and buying more of the "underweighted" sectors. For most people with busy lives and steady income, that is quite unnecessary. Do the rebalancing by buying more of the underweight sectors with your fresh savings derived from earning a livelihood. Instead of "re-balancing", you are urged to "maintain a balance", and the difference is whether or not you sell off some of your winners. It can be astonishing how far one of these innovators can go once it starts going. If you bought some schlock from a pump-and dump-broker, it's rather unlikely to keep rising for a year, so maybe you got a good one. But you should feel as I did when my seven-year-old daughter took her dime over to a restaurant's slot machine while we were touring through Nevada. "Please, God, make her lose."

Beginning Social Security Benefits

Some should start benefits before age 65, others should delay it for ten years or more

|

| Dr. Fisher |

BY mail or visit to the local Social Security office in your neighborhood, it is possible for anyone to determine how much you can expect to be paid in benefits, and at what age. In fact, it is a wise precaution to ask for this information every few years, just to be sure your payments are being credited properly, since hundreds of millions of payments are flowing into many millions of accounts, and you want to get things straight before years of problems accumulate. In the early years of the program, one of their biggest problems was that a great many people used the sample numbers on the illustration card instead of their actual "Social".

Assuming payments from your employers have been flowing properly, you currently have the option to retire at the age of 62 and start getting reduced benefits. You will get three extra years of payout, but you may need to pay income tax on some of it, and the payout will be less. More recently, the standard age to begin payments was raised to age 67, gradually phased in. And more recently than that, the payments became taxable for some people, with offsets for Medicare reducing it. Better check where you stand. My Pennsylvania Dutch uncle used to say it was bad arithmetic to take the money early. But my Scotch-Irish accountant advised everybody to take the money as soon as possible, because money in your pocket is real money, while future payments depend on your living long enough to get them, and just might depend on who was elected President. Who knows, you might get hit by a truck tomorrow. So, ultimately any decision about this matter is based on opinions which differ since the sanctity of contracts is fast becoming a quaint anachronism.

|

| Social Security Benefits |

However, the arithmetic is available, once you know a few facts. The longer you wait, the larger the monthly payments will become. However, you can count on about 3% inflation during the interval so the money might have less purchasing power. Some of the monthly payment will be free of income tax, some of it will be taxable at whatever your tax rate might be. If you spend the money, it's gone; but if you save it, it will grow at an after-tax rate which may or may not be greater than if you leave it with Social Security until you need it. The arithmetic isn't very hard, but if you look around on the Internet, somebody surely provides a fill-in-the-blanks tool which will calculate it for you.

If the arithmetic or your personal situation is such that you aren't going to spend your Social Security check as soon as you get it, here's what you do. Arrange for direct deposit into a world index fund, total market. Historically, that will grow at 8% compounded annually and will pay about 1.8% taxable dividend. Now, do the math again, and see if you are better off leaving it with those nice folks on Social Security Boulevard, in Baltimore, instead of those nice folks at Vanguard or Fidelity.

The whole theory behind this maneuvering is that many people have half-time jobs or dual incomes, or income from the sale of a house, which means that for a few years after they retire they have more income than they will have later in life. For them, there is a choice between the two methods of saving Social Security money for the time in life when they need it. Other people need every cent they can get, right now. If you are one of the lucky ones, try to be even a little luckier by using arithmetic and choosing between the options. If you are hit by a truck, it really won't matter what you do, so try to be an optimist.

Estate Planning Tool

It's complicated: a CRUT in a FF, administered by a DAF, and purchasing life insurance in an ILIT.

|

Life insurance escapes estate tax, but only when owned by an irrevocable life insurance trust. The amount of life insurance is limited by the money available for premiums in the family foundation, extended by virtual gifts (ie Crummey). One alternative exists to use a public charity instead of a family foundation, which increases the limits of the charitable remainder trust (CRUT) from 30% of annual gross adjusted income to 50%. However, control of the resultant charity passes to the public charity from the trustees of the family foundation. (In some families, that may not be important.) Generally speaking, the family foundation approaches shelters at most approximately a million dollars of the estate, while the public charity might shelter twice that. I am not clear whether the use of one precludes the other, or whether they can be added together. The basic point is that this estate tax shelter is mainly limited by the size of current income; whereas that income can be tailored by shifting assets to and from the non-income-producing property, there is created tension between income tax on extra income and estate tax consequences. Because of partisan political disputes, the size of future offsets is presently uncertain. The distinction between present asset value and future value must be remembered, but can be calculated if income and estate tax rates are guessed at. Finally, there is added inflation risk because insurance tends to convert equity value into a fixed-income asset. At its root, this complicated approach attempts to combine the tax exemptions of charity gifts with the tax exemptions of ILITs.

The complexity can be reduced somewhat by turning over the administration and investing of a family foundation -- to a donor-advised fund, as run by Fidelity and Vanguard, but also by the American Friends Service Committee, who may have originated the idea. The AFSC may be appealing to those donors who foresee waning future interest in charity within their own family, but who trust this institutional surrogate to turn charity decisions from donor-advised into donor's surrogate-directed, once family interest fades.

Reflections on Swensen

A. Techniques of rebalancing. Three directions to take this, occur to me.

1. Purchase 60/40 mutual funds and let them do the rebalancing. This would offhand seem the easiest way to do it, but what are the results? Do you think it would be practical to construct a 60/40 mutual fund by combining and rebalancing a world-wide index fund with a bond fund? Since bond funds are dubious, how about a mutual fund that contained the equity index fund and did its own bond juggling? How about a family of funds, mixing 50/50, 55/45, 60/40, 65/35, 70/30, 75/25. 80/20, as the investor chooses? Since this would probably amount to a pool that sold virtual shares, almost any combination seems feasible. But is it legal? At one time the fund of funds was illegal for whatever reason; possibly Vanguard has a right to object to such secondary use of its funds. By getting a fund together, there should be enough volume to consider real-time rebalancing. When you consider doing it for yourself, the fund approach seems increasingly attractive.

2. Establish two brokerage accounts at Vanguard, one for equities and one for bonds, each of which is linked to its own separate money market sweep fund. Monthly rebalancing should be possible from the monthly statement, with the money market of one account purchasing shares of the other asset class as needed for rebalancing. A refinement of this might be to purchase shares of the "wrong" account and hold them until the capital-gains period has expired, then transfer to the "correct" account. I presume that transfers between two money-market accounts would be fairly simple, avoiding the perplexities of buying shares with one account but depositing them in another. Adjusting the order to reinvest dividends or not reinvest seems like a nice refinement, lessening the need to sell things.

3. Doing the whole business in Quicken. If you are thinking of doing this for clients, you might want to avoid the hazards of actually doing the transactions, simply sending the client a set of suggested monthly instructions to give to his broker or transact electronically. This might seem attractive to people running trust funds, who already carry the fiduciary hazard.

B. Selecting or deselecting, those companies who regularly rebalance their own debt/equity ratios. One of the important insights I get from Swensen is that company treasurers are often rebalancing in the opposite direction from the investors. That is, issuing more stock as their price/earnings ratio gets ridiculously high, buying back their stock when the price gets cheap. Not all companies do this, and those who do probably reduce their volatility considerably. If this is a really major reason for investors to rebalance in the other direction, then there may be a considerably reduced value in rebalancing companies that are doing it for you, and enhanced value in rebalancing the rest.

1. Since you don't know the intentions of a company, and anyway they may change treasurers without your knowledge, there is a need to find some surrogate for this activity. That's particularly true of companies that may only do it in one direction, and thereby alter the balance between raising equity capital and borrowing. Does the p/e ratio seem adequate to you as a surrogate? If not, is there a practical alternative?

2. I've been told that small companies borrow from banks, large companies issue bonds. Is this of any practical value to an investor? Are they a distinct asset class? After all, you can change your debt/equity ratio by adjusting either component, or you can reduce your total external capital requirement by using internally generated funds. Does this issue get you anywhere in selecting asset classes?

3. Companies or asset classes with a lot of volatility apparently give Swensen an opportunity to rebalance profitably. Aside from that, it is better for a company to have low volatility or high? If all companies got religion and did their own rebalancing, would there be any value in investors continuing to do it? To put it another way, just where is the value added by rebalancing? What signs would you look for, to decide that rebalancing is no longer cost effective?

C. Life insurance to reduce taxation. The October 18, 2006, Wall Street Journal observes that the IRS has issued clarifying instructions about using life insurance to reduce taxation; it also goes on to say that lawyers will charge you $10-20,000 to read them to you. But, apparently, it's ok to do this if you follow the rules. Essentially, life insurance investments compound internally without taxation and also escape estate taxes if you donate ownership of the policy to your heirs.

1. In the case of a spousal trust, the estate taxes are already waived, so one complexity is reduced or eliminated. There is no need to transfer ownership of the policy.

2. So the issue reduces itself to avoiding dividend and capital gains taxation, short and long. I gather they have not thought of the requirement to distribute all income from a spousal trust, so there is a chance some agent would balk at the technicality.

3. So, except for this risk, it's a simple trade-off between the fees for insurance versus the taxes saved, and I strongly suspect the fees are worse, so the issue isn't worth considering at all. But of course I don't know what the fees are, so I don't know the threshold level where tax avoidance becomes an important asset. Even the health issue is semi-answered since you could escape a physical exam by selecting an annuity life insurance; more fees to overcome, of course.

D The same Wall Street Journal includes a quotation from unknown research that calculating the dollar value weighting of mutual funds versus fund results demonstrates that all reasons for not buying-and-holding combined show a 1.5% penalty for all strategies other than buy/hold.

1. Therefore, the 0.5% advantage of rebalancing over buy/hold is actually a 2.0% advantage over the penalty for deviating. That's a more substantial argument that has so far been made for rebalancing, but needs to be re-examined to be sure the penalty is not actually hidden in the 0.5% claim, since if so that would convert it into a 1% loser strategy.

2. For no visible reason, broker-handled funds average 0.5% lower return than direct-buy funds. May I suggest some hidden kick-back has surfaced?

3. Low-volatility stocks seem to produce an 0.8% advantage over high-volatility stocks and a shocking 2.8% difference on a dollar-weighted basis, suggesting volatility makes investors lose their nerve in addition to the innately inferior performance. Is it reasonable to give them a neutral weighting in a portfolio?

IRA ... Individual Retirement Accounts (3)

|

| TSR-80100 |

It wasn't Ronald Reagan on the phone, it was John McClaughry, Senior Policy Adviser. I'm not sure how important you are when you are a Senior Policy Adviser, but it rates you an office in the Executive Office Building that has fireplaces and sofas, conference tables, and -- off in one corner-- a desk. I knew at a glance that we were going to be friends, because his desk had a Radio Shack TRS-80 computer on it, too. Seeing that, emboldened me to stuff my temporary White House identification badge in my pocket, because a guy with a computer in 1980 was certainly a member of the brotherhood, and would get me out of trouble if the guards caught me taking souvenirs. I still have the badge.

John was and is a master networker; maybe that's the job description of a senior policy adviser, I wouldn't know. He knew everybody who had anything to do with health financing, in all the branches of government, including one I hadn't known about, the neighborhood Think Tanks. Everybody is forever passing out business cards to new acquaintances and sweeping them into the left-hand breast pocket in one continuous motion. In Japan, everybody passes out cards but makes a big bowing ceremony of receiving them; what then happens to them in Japan I don't know, but in Washington, they go into Rolodexes and everybody invites everybody to some gathering or other. One evening, I was the entertainment at such a gathering, and have usefully kept up with quite a few people who attended. It's a different atmosphere from some other functions, particularly in the State Department with the other party, where everyone pretends to be meeting you for the very first time when they really aren't.

A few days after our first meeting, John wrote me a short note. Senator Roth of Delaware was pushing something called IRA, or Individual Savings Accounts. Did I think the idea could be applied to health care financing? I suddenly felt as though someone had shoved a stick into my skull and was stirring it around. Of course, just perfect! Add that to a high-deductible or so-called catastrophic health care policy, and out would emerge individually owned health insurance policies, with the same tax shelter as Blue Cross gets, and the added kicker of earning compound interest while you are well, in anticipation of high costs when you are older. It gets rid of pay-as-you-go, it puts an end to "job-lock" and all sorts of other bad things. Perfect.

Because of the difference in our previous backgrounds, I was in a little better position than John was to see how many medical pieces would fall in place if you made this simple provision, which after all was only giving to self-employed people what salaried people had been getting for decades. Yes, it had a small cost, but no more than the amount self-employed people (like doctors) were being cheated out of. We were only asking for a level playing field.

John and I had our project, the Medical Savings Account, and although we kept in touch, we went our separate ways to sell it. John's field was the Republican Party, and mine was the medical profession. It might take a year or two, but the arguments were unassailable.

Retiring to the Workforce

Most Americans alive in 2020 will live to be ninety

|

| Dr. Fisher |

During the Twentieth century, average life expectancy for Americans at birth extended from a little less than age fifty, to a little less than age eighty -- roughly thirty years. Looking ahead to the next century, it's entirely reasonable to expect a cure for cancer and Alzheimer's disease to extend life expectancy to ninety-five. It's also reasonable to expect that somewhere along this path we will find such retirement expectations are more than the nation can afford. Everyone will have to go back to work.

Working ten years longer means ten years less time in retirement, and it also means ten years more time to accumulate sufficient savings for whatever time is left. Some people who are already working more than they want to, won't like that. There will be attempts to make retirement cheaper and to extract savings from novel sources, but further improvements in health care will wipe out all those efforts. The normal age for retirement will have to move to at least age seventy, probably seventy-five. If employers have problems with that, the solution will have to be second careers. So, let's shift our attention to people who are lucky enough to afford a thirty year vacation. They must go back to work, too.

A moment's reflection reveals that everyone must have a life goal of accumulating more money than is needed to live out his life. Once average life expectancy levels out to a stable point, ingenious life insurance design could bring us to the point of spending the last dime on the last day, providing we consider it worthwhile to spend the extra insurance administration cost. More likely, human psychology will always demand a little extra comfort from a little extra financial cushion, and there's a relationship with the age of retirement. The later you retire, the more likely it is you will have money to spare. For physical or mental reasons there will be people who can't work, but everyone else knows a simple solution to the problem of being able to retire: don't stop working until you can afford to quit. And by the way, the later you start saving, the longer before you can quit.

This vision of elderly America thus generates a need to create new jobs for people unable to retire, but the similarly growing number of elderly too infirm to work creates jobs for the advancing number of elderly who need a new career. Some variation of a voucher system will be needed to make this workable.

We have so far not worried much about the lucky, talented, or just miserly few who achieve life's normal goal of saving just a little more than they need; but that must change, they need to go back to work, too. Philanthropy, a very important part of American life, is struggling and needs their talent. It's likely that our business and economic success as a nation is responsible for diverting our energetic and imaginative talent toward the for-profit sector. The general attitude has been that if things are worthwhile, people will pay for them; businesses run not-for-profit can't really be worth much. That's very wrong, of course, but there's enough truth to it to require some changes.

Nonprofit organizations are often inefficient because efficiency is partly the consequence of seeking a profit. But the analysis must not stop with this hopeless truism; the manageable problem is to find new goals for efficiency which do not directly require profit-seeking. One approach would be for non-profits to create for-profit subsidiaries, later selling them off to enhance their endowment. The tax authorities would want to examine this approach to avoid harming competitive tax-paying entities, or sham arrangements in which the purported subsidiary dominates a nonprofit shell.

However, this and similar approaches merely continue the present mindset about the role of the donors and the volunteers. Nonprofit organizations tend to gravitate toward a professional staff with nominal trustee oversight, relegating the donors to the function of giving or getting donations. If philanthropy is to acquire a new drive toward efficiency to supplant the absent profit motive, the donors must be actively employed in the organization, noticing any waste or inefficiency, sharing the gossip, and appreciating the triumphs. To some degree, a form of this model is found in the auxiliaries of hospitals and museums, where staff administrators generally chafe in private about the class distinctions and disruptive ability to cut across management hierarchies. If this system is to work effectively, it needs to be studied for ways to be less threatening to the younger employees, and to get more useful work from the older ones.

Rentier Class

To hope to retire is to hope to be prosperous without working. Those who must work can grow sullen about it.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

Rentier income is passive income, such as interest on savings accounts. Lord Keynes gave the term a nasty rap by defining rentiers as "functionless investors". That suggested Keynes shared some sentiments about passive investing with Karl Marx, who seems to have invented the term; both authors apparently judged the rentier class by the standards of novels by Jane Austen and Edith Wharton, or perhaps movie stars depicted in the novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald. That is, not gainfully employed, mainly occupied with debaucheries and expensive luxuries. This envy-based image dies hard but may subside if rentier life becomes everyone's goal. Or it may turn vicious, if a majority of voters see themselves as Jacobins in the water with the sharks, looking hungrily at the lucky few in the lifeboat. Guillotine, anyone?

|

| Lord Keynes |

To a certain degree, these attitudes can be managed, as possibly illustrated by bankers. After all, bankers extend credit to financially secure borrowers at the lowest interest rates and refuse credit to the penniless clients who need it most. It is thus frustrating to discover that you can't have any borrowers unless you have some lenders, too. In the main therefore, the public remains tolerant of the differential cost of taking risks. However, the public is often intolerant of the true value of a banker's role: simultaneous exchanging of capital between those with a surplus, and those with a need. That's unforced barter; forced relief of need requires the use of political majorities, responding to political viewpoints. If votes were all that mattered, however, the growing proportion of the population in retiree status could afford to be more complacent than they are. So 30-35% of American GDP would now qualify as the spending of passive income, although the varying degrees of risk within such investment are hard to evaluate. The risk is sure to rise as more labor-intensive work gets globalized away. Observers notice a paradox: passive income seemingly increases as the labor to achieve it diminishes, quite the opposite of the 19th-century Communist idea of work as the source of all wealth. Rentiers are never far from the need to defend the value of non-work income, at the same time everyone seeks to avoid hard labor, except as recreation. Our inconsistency does need some fine-tuning.

|

| F Scott Fitzgerald |

In the future, one thing seems certain: a greater proportion of our population will be retired persons, living on pensions, rentier income from savings, and government handouts. As it becomes the universal expectation of everyone that thirty years of rentier life awaits in the retirement stage of life, there will be less chance for Keynes, Marx, and Fitzgerald to seem so congenial to the voting class. But take care; young people, particularly unemployed young people, are never far from asking, "And what have you done for us, lately?", as if fairness were something to be measured with a spoon.

|

| Karl Marx |

Curiously, one implication about rentier income has almost disappeared. Interest is paid by a debtor to a creditor; as Marx would have it, the poor workingman is paying the rich rentier. Dividend income represents the profit from a business to its owner or a farm to its farmer. But emotionally, that is hardly so. We have so sterilized the investment process that we seldom think of debtors and creditors but speak of "fixed income" and "fixed income investors". The income from ownership, or "equity", is now thought by economists to bear a definable relation to the "prevailing return from fixed income". To them, it's all the same thing. Future attitudes can be hard to predict, but although everyone seems destined to be both a creditor and debtor at the same time, the two are surely not the same thing.

It's also hard to predict Americans attitudes if passive income becomes say eighty percent of GDP. Or fifty percent of the population become rentiers. Eighty percent rentiers, if you exclude children. Americans worship work; even labor leaders cry out, "Jobs, jobs, jobs." Western Europeans, however, seem willing to sacrifice luxury in order to live without work as threadbare rentiers. Is that the product of brain-washing, or have they discovered some evil in work that Americans are unable to see? The ancient Romans once aspired to more luxury, fewer soldiers. Unsympathetic barbarian neighbors then wiped them out. Better do some thinking about this because the Law of Gravity will not save the situation, any more than history lends much comfort to it.

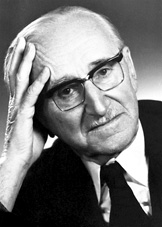

David F. Bradford, 1939-2005

|

| David Bradford |

We should take the word of his friend and colleague, Daniel Schaviro, that the core of David Bradford's professional career as an economist was his conviction that a very deep wrong existed when two people could earn exactly the same income over their lifetimes but the one who spent every cent immediately would pay less in taxes than the other who carefully saved for his retirement and heirs. Bradford was offended by this message our society was broadcasting.

Working for a time in the U.S. Treasury Department and later as a member of the President's Council of Economic Advisor's, he was able to explore the mechanical workings of tax law well enough to translate moral conviction into a workable proposal for political reform. In 1977 he published "Blueprints for Tax Reform", introducing these practical ideas at the highest level of academic rigor. The impact of his ideas in this paper extended through three presidencies, particularly the present one.

Bradford saw the tax injustice which penalized the Protestant ethic could be corrected in two ways. Either the tax code could shelter individual savings from taxes until they are spent (the IRA), or else convert the income tax into a consumption tax (like VAT). In either case, taxation would take place at the same time as consumption, rather than at the time of earning. Notice the person who saves money to spend later will suffer from both inflation and taxes on taxes on the inflation "gains". The political choice between the two proposed solutions was made by Senator William Roth (R, DE) who sponsored the Individual Retirement Account (IRA) and shepherded it through an intensely political Congress. His was a wise decision, since its voluntary nature made it attractive to politicians, while the French experience with a mandatory Value Added Tax (VAT) created political opportunities to favor certain industries, which politicians were quick to understand.

After twenty-five initially slow years, the eventual popularity of the IRA has now encouraged its extension to Social Security. That's what agitates domestic policy debate at the time of David Bradford's unfortunate death. The IRA model is also the basic concept underlying Health Savings Accounts (HRA), which struggled for many years but have reached their own period of growing acceptance. The Blueprints idea has thus dominated domestic politics for nearly three decades, while its originator remained largely unknown. Far from being a sign of weakness of the idea, it is a proof of the revolutionary nature of this simple concept that it initially provokes public resistance, but also inspires relentless tenacity among those who have taken up its challenge.

David Bradford returned to Princeton from his Washington experience, resting for decades at the quiet center of an Economics department that is not known for its quietude. After a most unfortunate fire at his home, he died of the burns in nearby Philadelphia, which hardly knew him.

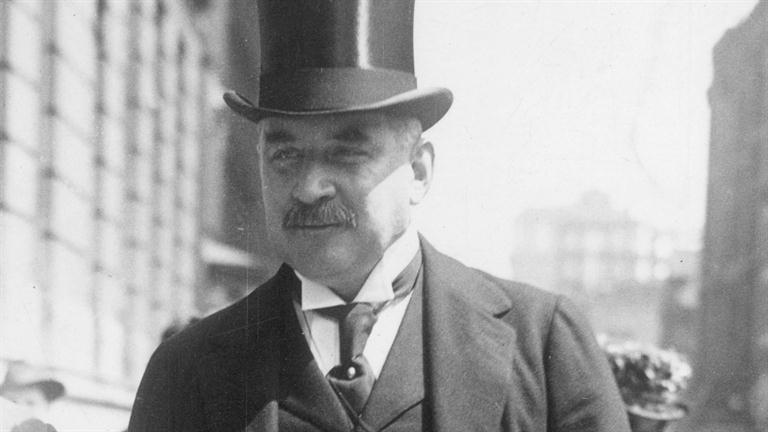

Donor Intent

At least three of the greatest treasures of Philadelphia are now used in ways that almost certainly flout the expressed wishes of the donor. Steven Girard's

|

| Alfred Barnes |

bequest for the enhancement of "poor, white, orphan boys" is now devoted mostly to black children, many of the girls, many of them non-poor by some definitions, and many of them orphans only in a limited sense. Alfred Barnes wanted his art treasures to be used for education, outside the city of Philadelphia which had offended him, and definitely not part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art which he disliked. They are now to be moved to Philadelphia's Parkway, close to and under the thumb of, the Philadelphia Museum of Art. John G. Johnson's immense art collection now resides within the Museum of Art in spite of the firm declaration by this eminent lawyer that it was to remain in his house, and definitely not to be used to promote some huge barn of a museum.

|

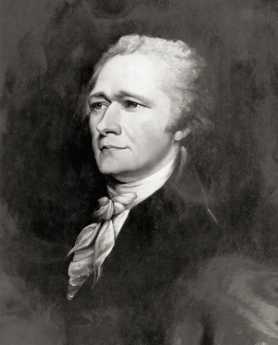

| William J Duane |

It's hard to imagine how any set of instructions could be devised to be more clear than these. Barnes employed a future Supreme Court Justice, Owen Roberts, to write his will. Girard similarly employed the preeminent counsel of his time, William J. Duane, to devise an extraordinarily detailed set of instructions. John G. Johnson was himself considered to be the most eminent lawyer in the city. In fact, he once received a fee of $50,000 for his opinion about a corporate financial plan, consisting of the single word "No" scrawled on its cover.

It would be interesting to know whether these famous cases are typical of the way wills are treated, either in this city or in the nation generally. Perhaps they are notorious mainly because they are so unusual. But perhaps they are indeed rather representative and stand as lurid examples of the general failure of the rule of law. Perhaps they reflect some deeper wisdom of the law, where Oliver Holmes intoned that the standard was not logic, but experience.

<Perhaps some guidance can be found in the decisions of Lewis van Dusen, Sr. who for several decades established the Orphans Court of Philadelphia as a model for the world to follow. Someone seems to have thought he set a good example. But was his reign an exception, or a glowing example of the triumph of society's wisdom over the crabbed grievances of dying millionaires in their dotage?

These remarks are made while the newspapers are filled with the story of a Texas billionaire who married a magazine model fifty years younger than himself. Some prominent local heiresses are known to have run off with their stable boys. Indeed, you don't need to read many tabloids to see a dozen examples of such behavior. Is it possible that some of them were acting up out of frustration at the probable betrayal by the courts of more reasoned instructions for their wealth?

Community Volunteers in Medicine

|

| Comm Volu In Medicine |

Mary Wirshup has a very different medical background from mine, but she's my kind of doctor. I couldn't help wishing, as she addressed our urban luncheon club, there could be thousands more like her, even while understanding more fully than she seems to, the reasons why doctors are driven from her behavior model. As we parted, it felt like saying a last goodbye to the Spartans marching to Thermopylae.

As 46,000 medically uninsured persons in Chester County get sickness and injuries, they know that a Federal Law prohibits a hospital accident room from refusing to see them, so ways are found to shunt patients to the CVIM free clinic, run by volunteers. This law is, in turn, a response to a government-created situation where a hospital which "accepts" patients must keep them. Any economics teacher can tell you that supply/demand issues are best addressed by price adjustment, so price controls in whatever guise lead to shortages. I must say I have little sympathy with the devious strategies which hospitals often employ to disguise their rejection of uninsured patients. At the same time, I know a lifeboat will sink if too many climbs aboard. Nevertheless, the semantic switch from lack of insurance to lack of care implies that only more insurance can surmount the barriers to care, which is absurd. For one thing, I know too many hospital administrators who are paid a million dollars a year, and one who is paid two million. And at least two health insurance executives are in the newspapers with a net worth over a billion -- yes, that's billion with a b. We have reached a point where reducing all physician income to zero would only reduce "healthcare" costs by 10%. As I look at Dr. Wirshup's modest clothing I can only surmise she plans to continue her modest living until she is 80 years old, after which her savings might see her out. Squeezing physician reimbursement is not intended to save significant money, nor intended to restore physician incomes to more equitable levels. It is intended to address the oversupply of physicians without confronting either the universities or the foreign trained lobby.

The elite tranche of medical schools do their part to relieve physician oversupply without reducing class size, through the encouragement of their students to go into research. I was well along at the National Institutes of Health before I finally decided I had not gone into medical school with that goal, and returned to teaching and patient care in a more satisfying model not too different from CVIM's obviously Pennsylvania Dutch spirit. The Amish at the far western end of Chester County reject the whole idea of insurance; their most characteristic statement is "Don't send me no bills." That attitude is rather a contrast with the shiny housing and automobiles in the Silicon Valley developments of Southern Chester County, or even with some rather bewildered Quaker farm families scattered over the rest of the county next to the horsey set. Chester County is America.

On Second Street in Society Hill, next to the park where William Penn's house stood and a few feet from Bookbinders, is the house of Dr. Thomas Bond. Bond conceived the idea of building the first hospital in America and with Franklin's publicity machine succeeded in getting it built, to care for the "sick poor". Dr. Bond started a second enduring tradition as well. When the Legislature expressed doubt that the institution was sustainable, he pledged to convince the local medical profession to serve the poor without charge. Some of the legislators who voted for the measure did so in the belief that charity care would never appear so the gesture would be without cost. The physicians did indeed come forward, in sufficient numbers to run many institutions for two hundred years. In 1965 health insurance made its national appearance and has regarded the benchmark low costs of charity care as a threat, ever since.

Immigration

|

| Gold |

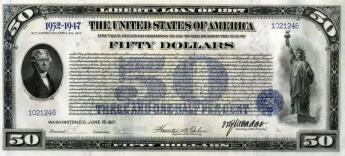

We're alluding indirectly to immigration as a general topic in this article because sooner or later every discussion of every aspect of immigration adds a claim of "fairness" to the balance. In this case, plain talk about fleecing peasants first requires the definition of an unfamiliar term. Seigniorage, also spelled seignorage, or seigneurage, originally only denoted a fee which governments charged for milling coins out of precious metal. Developing nations often didn't have the necessary technology, so they paid some other country to do it for them. That was fair enough, but soon "trimmers" would shave the side or surface of coins and gather up the dust for sale. That practice led to clever serration of the formerly flat edges, much simpler than weighing coins to detect cheats.

In time, improved printing techniques allowed governments to keep precious metal in vaults and issue paper currency, some of which inevitably got burned, shredded or lost. Since the issuing government could then keep the whole value of lost currency minus printing costs for itself, the term seigniorage evolved to include this more lucrative method for governments to cheat citizens, abusing their monopoly on the currency issue. There might seem to be some temptation for governments to print money on fragile paper, except it is overbalanced by the need to make it hard to counterfeit. Happily, this sort of seigniorage always seemed less offensive because everybody agrees that if you have money in your pocket, shame on you if you lose it. As transactions become more sophisticated, however, some innovative modern arrangements which loosely fit the definition of seigniorage become a new source of moral dismay. One facet of currency razzle dazzle concerns immigration, which is itself always a contentious matter.

|

| Spanish |

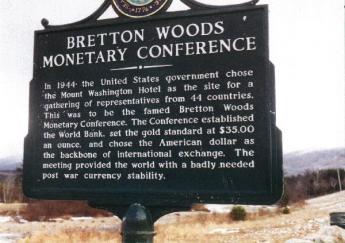

Right now, it is authoritatively estimated that the Social Security program has collected half a trillion dollars in Social Security and Medicare taxes, whose rightful owner is impossible to determine. Some of the beneficiaries may have died without claiming the money, so some of this topic might be classified as escheat, or abandoned by the owner. But very likely the bulk of this money, under modern circumstances, was withheld from illegal immigrants by their employers, either without their knowledge or using counterfeit social security numbers; and the fugitive status of the owners made them reluctant to claim it. Half a trillion is five hundred billion dollars.

This sort of discovery leads to some troublesome thoughts. If the immigrants are legal, or if now illegal may receive amnesty, they will be fully eligible for social security benefits. You might say they earned such benefits, but our tormented public pension system is in fact almost entirely funded by one generation funding its parents' generation. That borrowing between generations means paying for it later, so of course, it enjoys the politician spin-term of "pay as you go". An American of multi-generational descent has paid for his parents while he works and expects to have his own pension paid for by his children. An immigrant, never mind his citizenship, is paying the same taxes, but has no parents as beneficiaries. When the newcomer retires he may be a burden to his children like the rest of us, but his current payments go into the black hole of government deficits without paying for any parents. Here we have seigniorage on a much grander scale. The money presently diverted from the usual channels by this ingenious arrangement is calculated to be two trillion dollars, or four times as much as the paper money seigniorage, and many many times as much as the shaved-coins scam. Just for comparison, consider that America is estimated to have 900 billionaires. Their aggregate net worth is probably only slightly greater than the amount our government garners from illegal immigrants.

The matter really does seem to be important enough for us to learn how to spell seigniorage, and even reconsider whether to apply the term to its most popular current manifestation.

Africa Comes to the Schuylkill

A journalist, John Ghazvinian, recently toured the many countries of Africa, wrote a book about it and carried his message to the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia. Philadelphia does not think of itself as particularly involved in oil matters, or African ones. But the fact is the refineries on the Schuylkill down by the airport generate two-thirds of the gasoline now used on the East Coast, and right now it mostly comes from Nigeria. There was a time when the crude oil coming to Philadelphia came from Venezuela, but politics are a little unpleasant there at present, and anyway Venezuelan oil is heavy and full of acids. The refineries which specialize in that kind of heavy oil are on the Gulf Coast. Long before the Venezuelan era, the Philadelphia refineries were constructed to refine crude oil from upstate Pennsylvania. They were once the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad, because oil refining from Bradford County gave the Pennsy a return freight, whereas the competitive railroads running out of New York and Baltimore had to return from the West without cargo.

|

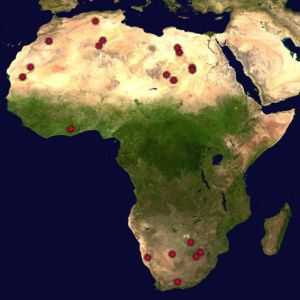

| African Map |

There are 54 countries on the continent of Africa, quite different from each other in character. One dominant characteristic of Africa is its lack of natural ports, and even the Mediterranean ports are cut off from the rest of the continent by the huge transcontinental stripe of Sahara desert. Major wars and famines, monstrous genocides, unspeakable cruelty, and poverty go on there without much notice by the rest of the world.

The largest country in Africa is Nigeria. Anyone with even minor dealings with Nigeria soon sees that corruption and dishonesty pass all Western imagination, and they have serious tribal warfare as well. The discovery of large deposits of oil in the region faced the international oil companies with a rather serious difficulty. For instance, Shell Oil has had over 200 employees kidnapped for ransom and is seriously contemplating abandoning its whole venture. At the moment, corruption is coped with by constructing oil wells a hundred miles out in the ocean.It's almost true that the huge tanker ships make from Philadelphia and return, without the crew talking to any natives of Africa.

We hear that genocide is in full bloom in the Sudan, and that poverty in that country similarly passes belief.

|

| Chad Poverty |

They have oil in the South of Sudan so we may hear more of it. Chad has poverty and oil, and civil war. They have a big Exxon facility, but there isn't a single gasoline station in Chad. At the moment, Angola has paused in its enormous civil war, which killed millions, and Chevron will surely encounter unrest before it is done. Gabon appears to be extremely prosperous, from oil money of course, but they are being ravaged by the Dutch Disease, of which more later.

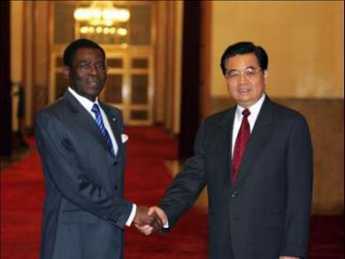

Apparently, Equatorial New Guinea sets some sort of record for wild behavior. It has lots of oil, and a strong Chinese influence. The current

|

| Mbasogo and Jintao |

President of Equatorial New Guinea got his job by shooting his uncle. But don't feel too sorry for the uncle, who used to have an annual Christmas morning celebration, consisting of herding his enemies into a football stadium, and shooting them for the edification and entertainment of the populace. After listening to Mr. Ghazvinian, it seems small wonder that so few American tourists, or journalists, or even missionaries, manage to complete extensive African excursions. As everyone notices, if you don't have journalists, there is never any news.

Let's turn to the Dutch disease,

|

| David Ricardo |

of which Africa currently displays many examples likely to torment economics students for decades after Africa eventually rivals Houston. Let's start with David Ricardo, who electified the Nineteenth Century world of economics with his principle of comparative advantage. Ricardo pointed to the obvious truth that always and everywhere a nation does best for itself by identifying its best economic feature and then sticking to it. If every country wakes up and does that, every country must then trade with its neighbors for other things it isn't so suited to make. Consequently, tariffs and trade barriers are a hindrance for everyone, in time impoverishing all nations in the cycle, whatever short-run advantages of tariffs may seem enticing.

|

| North Sea Gas |

So far as I know, Ricardo was quite right, but someone had better hurry up and reconcile his underlying premise of comparative advantage with the Dutch Disease. The Dutch disease was identified and named by an anonymous writer for the London Economist about thirty years ago. Noticing that the Netherlands experienced a marked worsening of its general economy after the discovery of North Sea gas deposits, the observer for the magazine concluded that sudden accumulation of wealth in the gas industry led to a rise in the value of the Dutch currency, soon making it impossible for non-gas industries to export, unable to compete at home with now-cheaper foreign imports. Naturally, investors rushed to invest in gas, sold their holdings in other industries, and Holland was propelled in the direction of a one-industry economy, quite at the mercy of fluctuating prices of gas. This was the Dutch Disease born, and Ricardo's principle of comparative advantage exposed to quite a severe challenge from which it has not completely recovered. This is important, so how about a simpler description: When gold is discovered, people drop tools to have a gold rush. Wealth lost from dropping tools is greater than wealth gained from the gold.

Fear of the Dutch disorder seems to be the reason why the Chinese are buying our Treasury Bonds, the Japanese engaging in the astonishing "carry trade," and the Arabs buying American private equity funds. The common strand through all these schemes is this: By sending their bonanza savings abroad, they "sterilize" them from their tendency to force their currency upwards. They are exporting inflation, but also endangering their own struggling non-bonanza industries, which are the main hope for diversifying their economies and getting rid of the Dutch effect. Somewhere during this balancing act, politicians get involved and make things worse. So they call in their generals and admirals, to explore solutions we prefer they were not in a position to explore. Simpler description: When you discover oil, inflation soon follows. And all too often, revolution follows that.

The 1787 the American Constitution unknowingly cured thirteen cases of the Dutch Disease, by imposing absolute freedom of interstate commerce. After eighty years, the benefits of this national union would persuade the North to bleed and die for it. Although the Confederacy thought they were fighting for their way of life, meaning slavery, even the Southerners today recognize they are better off in a Union. Unfortunately today, the European nations are still having a hard time believing the benefits of union could possibly outweigh their allegiances to language, religion, and the wartime sacrifices of their ancestors. They are very wrong, but we are wrong to sneer at them. Except for maybe Switzerland, it is difficult to name another instance in all of history where several independent states gave up local sovereignty for the benefits of a diversified economy with local pockets of comparative advantage. Let's restate it again: the Dutch disease is a result of sudden single-industry prosperity in a country too small to control it.

By the way, what eventually happened to the Dutch? It seems likely that absorption of little Holland into the European Common Market helped dilute the corrupting effect of gas prosperity. It suggests the possibility that Dutch can be reconciled with Ricardo through the common denominator of reduced national barriers to trade and currency-- reduced sovereignty in a milder form. But it's a hard slog. Maybe we could envision annexing Alberta to soften the commotion of oil tar, but it takes a lot of imagination to see the amalgamation of China and India, any time soon. There may thus be nations too big to merge, but nevertheless, it would probably be less destabilizing to merge with all of Canada than just with Alberta if you overlook the obvious fact that it is easier to persuade a small country than a big one. Just kidding for the sake of example, of course, since Canada shows no interest in the idea.

Meanwhile, take a look backward from the highway overpass the next time you travel to the Philadelphia Airport. There's a lot more going on in those refineries than just black liquid flowing into steel pipes.

Hayek Confronts Keynes

|

| The Four Horseman |

Catastrophes seem to have fashions. There was a time when the four horsemen of the apocholypse -- pestilence, war, famine, and death -- rounded up the main things to keep you awake with worry. Perhaps it is too soon to gloat, but pestilence and famine seem tamed, even ready to be "put down". War remains a serious cause for concern, but a case can be made that two economic disasters, inflation, and recession, have moved up to dominate our nightmares. Indeed, it is the Summer of Love in 1967 which seems to mark the watershed moment, when basic survival stopped being the main risk in life, supplanted by threats to existence that are largely self-inflicted. The first warning of this sea-change appeared in the fall of 1929 when it seemed to be deflation, unemployment and all the other havoc of economic recession that caused wars, famines, and pestilences. The 1929 crash did not send a fully readable message, however, because it was so one-sided. It took another 37 years for the world generally to appreciate there was an opposite side to it; inflation was just as bad as recession, and both problems were largely man-made. One person gets most of the blame for the distorted emphasis. John Maynard Keynes, later Lord Keynes, was the prophet who seemed to save the world with the doctrine that the deflation emergency was so dire that civilization could not afford to worry about the long-term drawbacks of deliberate inflation. He persuaded world leaders to inflate the currency before civilization disappeared. After all, in the long run, we are all dead.

|

| Roosevelt Stamps |

There's an irony that Franklin Roosevelt was a hobbyist who collected postage stamps because stamp collectors were about the only Americans who were dimly aware that Germany and Austria had hyper-inflation as the main curse. Austrian postage for billions of marks gradually filtered into our collections of odd foreign stamps, arousing mild international curiosity. But Friedrich August von Hayek was living in the midst of it, painfully aware of its pain and chaos. It became the central focus of the life of an aristocratic decorated war veteran who became a distinguished economist, eventually winning a Nobel Prize. What caused inflation? Why didn't it stop? Why was it so destructive? How can inflation be prevented? How could Maynard Keynes possibly urge the leaders of nations to inflate their currency deliberately?

As a scholar in the dismal days of world depression, Hayek had a hard time, living for long periods on the charity of a few philanthropists who recognized his talents. He is best known for his scorching analysis of collectivism, a craze which swept through academic and political leadership, particularly in Europe, and his persuasive views probably constitute the main intellectual force which ultimately ended the Cold War. It is seriously stated that personal animosity by Socialist-leaning academics materially injured his academic career, although it probably gave him more time, and motive, for serious writing. Inflation and political collectivism do not seem tightly connected, but it is easy to observe that command economies do inevitably clash with private property and market decisions. For the present, it seems useful to set aside Hayek's monumental political achievement of discrediting Communism and focus on his penetrating view of inflation.

|

| August von Hayek |

You can almost watch his mind at work. If you give long hard consideration to the topic of inflation, you have to conclude that there seems no reason for it to be a bad thing. It may take a little time, but the price of everything will eventually readjust to a new higher level, and relationships will go on undisturbed. At first glance,

You can almost watch his mind at work. If you give long hard consideration to the topic of inflation, you have to conclude that there seems no reason for it to be a bad thing. It may take a little time, but the price of everything will eventually readjust to a new higher level, and relationships will go on undisturbed. At first glance,

inflation is just a harmless numbers game. You can understand the power of inflation; everybody likes a little of it for his own personal benefit. If everybody enjoys a little of it in his own sphere, then the whole world is pushed to a higher numerical level.

After long consideration, Hayek came to see that the disruptions of inflation are caused by the uneven speed of penetration throughout an economy or nation. If the price of oil goes up, the price of transportation goes up, then the price of home heating. But those who take the train or who heat their homes with coal are not affected so soon. Mortgages carry a fixed interest rate for thirty years until the unwisdom of such agreements becomes clear, but it takes time. The process of inflation creates winners and losers, and disruption in the culture of payments. The speed of payment is itself a factor in the virtual size of the monetary pool. In the long run, we're all dead and it all settles out unless we set in motion a universal scramble to get out the door before others get there. Inflation is just as much evil as collectivism, and somehow the two are usually seen together. The Road to Serfdom sits on the shelf, right next to The Austrian Theory of the Trade Cycle, and Other Essays .

Health Maintenance Organizations (HMO)

|

| HMO |

It's an ancient wrangle whether a manufacturer should actually own its suppliers or the reverse; or instead whether it's healthier for industry components to stand at arm's length from each other. At issue is not only what is best, but what is fair. If industry mergers seem sufficiently unfair, it will be proposed they should be illegal. That's the main substance of a lot of antitrust argument. Unfortunately, what is valid in good times may be reversed in a downturn. A prosperous supplier of materials often acts as a "cash cow", saving a merged enterprise from bankruptcy. Unfortunately, within a different economic climate one badly failing supplier can bring down the whole merged enterprise. There's also organizational friction; a temporarily prosperous unit may get to thinking it should boss the less prosperous units around. At the very least, the cash cow resists the use of its cash reserves to help "losers". Several centuries of experience have thus left a minefield of old laws, traditions, and ingrained prejudice to undermine any broad standards for what is best. In no field is this truer than the Medical Industry.

Eighty years ago in Houston, the first Blue Cross health insurance company was started for a single group of school teachers to pay for service in a single hospital. That expanded to other subscribers and other hospitals, soon making it more workable for insurance, subscribers, and hospitals to stand at arm's length, allowing for a variety of local combinations. During World War II, combat in the Pacific led shipyards to be built on the West Coast, but westward migration of steelworkers was hampered by lack of local medical facilities for them and their families. Taking advantage of the loophole provided in the wartime wage and price controls, Kaiser Industries attracted medical personnel by building hospitals, paying salaries, and offering physicians ready-made medical practices. Because of various licensing laws, Kaiser's medical enterprise was divided into two corporations, Kaiser and Permanente, so a specialized corporation within the Kaiser-Permanente Foundation could accommodate the licensed practitioners. The salaried nature of the physician organization immediately caused trouble with local fee-for-service practitioners, who were thus excluded from a large population in their neighborhood when they could not readily adjust to varying mixtures of the two payment methods. Their reaction, led by an obstetrician in Stockton, California, was also to organize dual-corporation structures which were exclusively fee-for-service. Because Kaiser had a Foundation, they also called their organizations Foundations for Medical Care. Then, as now, it proved difficult to run a practice with two different reimbursement philosophies in the same waiting room; in time, friction between the two styles tended to increase as doctors who were more comfortable with each style tended to segregate themselves. Since offers of salaries are more immediately attractive to newly-trained physicians, they flocked to California to serve the steelworkers who were in need of doctors. Fee for service, on the other hand, allowed the gradual assembly of a more durable practice composed of patients who could test what they liked before making a permanent allegiance. Essentially, the transients went to Kaiser, more permanent settlers used fee-for-service.

Thus, it came about that several models for health care reform were tested in a few smallish towns of central California. These demonstration experiments may perhaps not meet everyone's standard for scientific purity, but at least they were public examples with the dumber features knocked away. They certainly provided a laboratory where ideas could develop about topics that otherwise were merely opinions and unsupported conjecture. The Foundations demonstrated that physician-dominated organizations could contain costs and maintain quality in a satisfactory way; there had previously been doubted about their ability to contain cost. The Kaiser organization showed that salaried practice performed acceptably as well, both to most staff physicians and to a majority of the patients; there had been doubt about the willingness of the public to limit choices to a panel of assigned physicians, mostly young and usually from elsewhere. Finally, the two systems seemed to be able to live together more or less peacefully; indeed, the California public seemed reassured that two systems apparently kept each other in check.

The first main difference rested on the system of quality control. The local Foundations developed review systems based on peer review and peer pressure; these worked remarkably well, particularly in constraining non-physician costs like pharmacy, tests, and hospitalizations. Cost and quality control in the Kaiser system was more rule-bound and quicker to apply discipline, kept within bounds however by the ability of both patients and staff to jump ship for the other system. Aside from professional peer review, the Kaiser system experimented with owning hospitals, laboratories, pharmacies. Here, the experience directly paralleled the experience of manufacturing industry with its suppliers; when reimbursement was generous suppliers generated welcome revenue. When reimbursement was constrained and substandard, ancillary service losses were unwelcome. Taken overall, the Houston experience was repeated, that ownership of such facilities was mostly a headache. Indeed, subsequent experience has shown the two systems usually co-exist nicely within independent ancillary facilities.

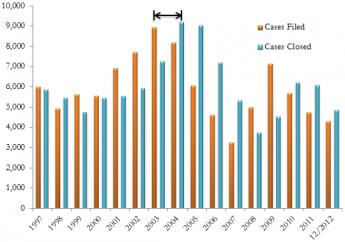

The Stockton, or Foundation for Medical Care, approach grew popular in the West. The variant which grew up in Utah was locally popular and attracted the attention of Senator Wallace Bennett. The Bennett Amendment to the Medicare Act then picked out the peer review system as the secret of success and set up a nationwide system of Professional Standards Review Organizations (PSRO) to conduct peer review of Medicare and Medicaid patients. The drawing of boundaries around these organizations was the most difficult part, and sometimes the boundaries were inept. Rural districts were adamant that the standards of big-city medical schools were not to be applied to their scattered resources, and urban areas saw themselves as ancient Rome surrounded by hostile tribes. Although these difficulties were foreseen, it is not always possible to draw a line that will separate the cultures, particularly where the outward migration of suburban housing was more rapid than the construction of suburban medical facilities, leaving the medical culture unstable. The PSRO system was quite successful in many areas but caused trouble in others that were not adequately addressed. The central concept of the review system was that the doctors who worked together could quite readily identify the outliers, and better than anyone else could judge whether the local situation was justified. True, some practitioner might try to abuse the system to the disadvantage of his competitor, so no adverse decision was final until there had been an opportunity for outside appeal. There might even be a few circumstances requiring a still higher appeal. The system was new and untried, but it produced eminently satisfactory results from the point of view of the Federal Government paying the bills. As former President of one of the largest PSROs in the country, I will assert that there was remarkably little friction or resistance in the medical community. My very good friend, the President of the New York City PSRO says much the same, and most people would say that if you can carry off a new system in New York without a lot of argument, it must work pretty smoothly. The Government wanted to eliminate unnecessary Medicare costs, particularly in hospitals, and it wanted to maintain peace with the medical profession. Hospital costs are obscured by the wide gap between posted charges and true underlying costs, compounded by disagreement about the proper assignment of overhead charges. Charges were not the assignment of the PSRO, utilization was. Days of hospitalization per thousand enrollees fell from roughly 1000 days per thousand to roughly 200 days per thousand, and that satisfies me at least that we were doing our job; physician peer review was doable.