2 Volumes

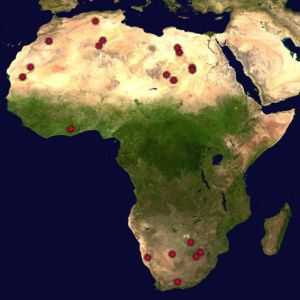

BANKS REDEFINED

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Investing, Philadelphia Style

Land ownership once was the only practical form of savings, until banking matured in the mid-19th century. Philadelphia took an early lead in what is now called investment and still defines a certain style of it.

Quaker Investment Committee

|

| Jonathan Rhoads |

Charitable institutions and other non-profit organizations occasionally assemble an endowment and thus develop a need for an oversight committee to hire (and occasionally fire) an investment manager, to monitor the fund's management, and to assess the manager's fees. The meetings of the oversight committee could, therefore, be pretty brief, related to two numbers. How had the endowment portfolio performed, compared with some acknowledged benchmark? To these two numbers might be added a brief summary of the investment management fees, compared with the usual benchmarks (40 basis points, or .4%, would be a common standard). However, an agenda so mercilessly sparse seems an inadequate reason to convene a group of worthies for an hour, and quite commonly the committee will chat about investments in general, hoping to pick up some personal pointers. A good tip or two makes the whole effort seem worthwhile.

On one such occasion in 1987, the famous Quaker surgeon Jonathan Rhoads, Sr was chairman of the committee. The manager of the endowment was a handsome fellow whose picture had occupied a full page of the New York Times financial pages just a day or two before this particular meeting. The picture had been truly spectacular, the tailoring was remarkable, and he surely had perfect teeth. As this gentleman entered the room, the committee gathered around, slapping his back and congratulating him on his fame with great jollity. Little did the group know that within thirty days, the stock market would have its most severe drop in almost twenty years. Unnoticed at first by the merry-makers, Jonathan Rhoads had sat down at the head of a perfectly empty long mahogany table, and was intoning to the empty seats, "We will now begin by reading the minutes of the last meeting of this committee". Visibly shaken, the group immediately broke up and took their seats.

Rhoads went on. We were now to hear the report of our portfolio by our manager. Proudly, it was noted that in February we had bought XYZ for 20, and in July we had sold it for 44. And in March we had bought ABCs for 60, and it now stands at 100. When he had concluded, the chairman said, "That's fine. That's just fine. But what bothers me is that point of confusion." Why, what confusion, Dr. Rhoads?

"The confusion between investment genius, and just being in a bull market." Later the same month, the stock market suddenly dropped 22% in one day, thus guaranteeing that no one in the room would ever forget the episode.

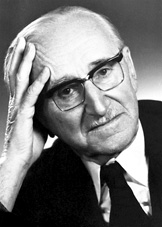

John Bogle, A Prophet In Our Valley

|

| John C Bogle |

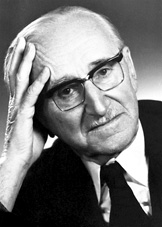

Those who never met a living legend would have found in John C. Bogle a good place to begin, 80-plus years old, lively and very charming. The Vanguard Investment Company, which he founded, provides him a little think tank office, out of which have come several books and many articles (somebody else is running the company, now.) The drift of most of what he writes and most of his testimony to Congress, or at awards ceremonies, is that mutual funds charge too much. When the press decides to feature him, the spectacular theme is emphasized that in 1996 this current squash and tennis player was just about dead, and had a transplant of someone else's heart to keep him going. A populist graduate of Pre-Vietnam Princeton, and also the embodiment of a medical miracle, now, those things are newsworthy.

Future students of finance, however, will regard those things as minor footnotes. Bogle's real achievement was the invention of the index fund. Indexing had two purposes and probably stumbled onto a third. It combined diversification, low administrative costs, and outstanding investment performance in a single security. There will be foot-dragging in the boutiques and bucket shops, but this invention is well on its way to converting investment management from an inefficient luxury of the rich into an affordable efficient commodity for everybody. You will know that a fundamental has been established on the day when the U.S. Government starts buying index funds, or at least when it permits them to help finance Medicare or Social Security. Such invested funds of a government qualify for the term Sovereign-wealth funds; in fact, since major problems can be imagined if governments start to vote common shares, Heaven helps us if they don't stick to index funds. The investment community already knows that something basic has arrived, by their own standards. The original index fund will soon have a trillion dollars invested in it. Just do the math on what you would be paid if you realized a fifth of one percent, year after year, on managing a trillion. And then reflect on the impact on transactional costs generally, when many eminent firms still charge five times that much. To make barrels of money and still be a hero for making your product remarkably cheap -- now, there's a Philadelphia dream.

A technical explanation. Five hundred stocks as one lump are cheaper to buy and sell as a "program trade", and perform more smoothly, than any of them individually, because the ups balance out the downs. Transaction costs are less, because there is hardly any switching among the 500 stocks by the committee in charge, and therefore few taxes to pay. Fine, but what might not be easily anticipated is that the lumped investment performs better, unmanaged than the vast majority of funds managed by experts. Large funds, at least, are forced to buy the

stocks of large corporations. Large corporations are inherently subject to immense scrutiny and publicity, so there remains little advantage to being on the inside or acting quickly on general economic news. What everybody knows, in Wall Street parlance, isn't worth knowing. Index funds made up of small companies, or foreign companies, may possibly not work out as well as those limited to large domestic companies. For a while, it was thought index funds would out-perform when everything in the marketplace was going up, but underperform when most things were going down in a bear market. Not so, they seem to work better any way you look at them. They are the standard for performance, not just a measure of the averages. These things are here to stay.

Well, maybe. Reservations remain, although they don't have much to do with investment choices. It may take decades to happen, but it's hard to escape the uneasy feeling that some manager, someday, will figure out a way to divert a hundredth of a percent, or so, into his own pocket. A hundredth of a percent of a trillion dollars is quite a temptation. Perhaps an even more serious concern is that voting control of the corporations in the portfolio inevitably gets diluted by widespread index investing. Management supervision by stockholders is potentially lessened. Whether this will lead to management abuses, a temptation for minority stockholder intrusions, or to the government over-regulation, taking any of these directions would likely create a new power balance in the economy.

Meanwhile, John Bogle, who died on January 16, 2019, is on his way to financier sainthood. He's certainly in a class with Anthony Drexel and Nicholas Biddle, already. And other icons are under review.

Health Savings Accounts

The legislation removes the hampering restrictions of the 1995 Law. What follows is a brief outline of the main features of the HSA/MSA clause in the 2003 law,

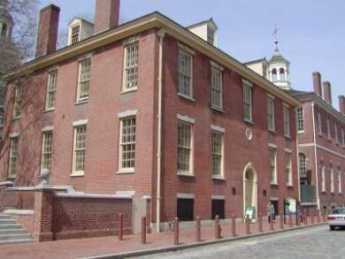

|

| U.S. Capital |

as published by the main authorizing committee, the House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. From this point forward, more specifics of the program will probably be written by the Executive Branch and published in the Federal Register. The Ways and Means Committee will continue to exercise oversight authority, however, in conjunction with the Senate Finance Committee. As a consequence, statutory modifications of the program are likely to appear in future annual budget reconciliation acts, or else in any new Medicare amendments. The legislative route map becomes more understandable when it is recalled that Medicare itself is considered to be an amendment (Title XVIII) of the Social Security Act.

Committee on Ways and Means

Medicare Prescription Drugs, Improvement And Modernization Act of 2003

Health Savings Accounts (HSA's)

Lifetime savings for Health Care

Working under the age of 65 can accumulate tax-free savings for lifetime health can needs if they have qualified health plans.

A qualified health plan has a minimum deductible of $1,000 with $5,000 cap on out-of-pocket expenses for self-only policies. These amounts are doubled for family policies.

Preventive care services are not subject to the deductible.

Individuals can make pre-tax contributions of up to 100% of the health plan deductibles. The maximum annual contributions are $2,600 for individuals with self-only policies and $5,150 for families (indexed annually for inflation).

Pre-tax contributions can be made by individuals, their employers, and family members.

Individuals age 55-65 can make additional pre-tax "catch up" contributions of up to $1,000 annually (phased in).

Tax-free distributions are allowed for health care needs covered by the insurance policy. Tax-free distributions can also be made for the continuation coverage required by Federal law (i.e., COBRA), health insurance for the unemployed, and long-term care insurance.

The individual owns the account. The savings follow the individual from job to job and into retirement.

HSA savings can be drawn down to pay for retiree health care once an individuals reach Medicare eligibility age.

Catch-up contributions during peak savings years allow individuals to build a nest egg to pay for retiree health needs. Catch-up contributions allow a married couple to save an additional $2,000 annually (once fully phased in if both spouses are at least 55.

Tax-free distributions can be used to pay for retiree health insurance (with no minimum deductible requirements), Medicare expenses, prescriptions drugs, and long-term care services, among other retiree health care expenses.

Upon death, HSA ownership may be transferred to the spouse on a tax-free basis.

Contain rising medical costs- HSA's will encourage individuals to buy health plans that better suit their needs so that insurance kicks in only when it is truly needed. Moreover, individuals will make cost-conscious decisions if they are spending their own money rather than someone else's.

Tax-free asset accumulation- Contributions are pre-tax, earnings are tax-free, and distributions are tax-free if used to pay for qualified, medical expenses.

Portability- Assets belong to the individual; they can be carried from job to job and into retirement.

Benefits for Medicare beneficiaries- HSA's can be used during retirement to pay for retiree health care, Medicare expenses, and prescription drugs. HSA's will provide the most benefits to seniors who are unlikely to have employer-provided health care during retirement. During their peak saving years, individuals can make pre-tax catch-up contributions.

Chairman Bill Thomas Committee on Ways and Means 11/19/2003 12:56 PM

Investment Strategies

The Latin phrase Quis custodies custodies warns that it's pretty hard to find anyone you can completely trust. Investing for your retirement, you must be careful to avoid transaction fees to pay your agents, and taxes to pay your government to watch your agents, who in turn watch the companies they invest in.

|

| The Pitcairn Financial Group |

Gradually, the world is coming to accept John Bogle's idea of a market index fund as the best most people can do. Investing in the whole market, it doesn't do much trading, whether buying or selling. Therefore, it has minimum costs, minimum taxes. As a by-product, it has maximum diversification, hence maximum safety. Low costs and high safety don't automatically give the best performance, except that somehow they do. The Index Fund idea just relentlessly outperforms the vast majority of investment advisers, in both up-markets and down-markets. Investment advisers just hate index funds, bad-mouthing them constantly. But if you buy anything else, you had better have a very good reason to do so.

Well, it's just possible that a second Philadelphia-born idea can do it. The Pitcairn Foundation was created for his family by John Pitcairn, one of the world's all-time champion investors. About fifteen years ago, the Johnny Appleseed spirit caused the Foundation to open up its investment approach to non-family members; they created a public mutual fund company based on the collective ideas and experiences of the Foundation. John Pitcairn bought the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, nurtured it to success as PPG Industries, and then eventually sold it, based on the observation that almost no firms, family owned or otherwise, survive more than seventy-five years. Companies should be bought with the intention to sell them, even though they are managed expertly throughout their existence.

The Pitcairn Foundation observed that (although the managers wouldn't always admit it) continuing dominance by the founding family almost always proved beneficial for the running of the company by hired expert managers. Nepotism was often a bad thing in the managers, but a very useful thing in governance. But if you go too far with this idea, you may get into the stifling arrogance of family control in European and Oriental firms. Founding family control keeps the managers from over-paying themselves or worse still, under-working themselves. But if you allow the inevitable minority of worthless family members to pilfer the company, you get the same thing at a different level of control, where it is just harder to fire them.

After a great deal of intense scholarly work, it was observed that there are about six hundred major American corporations where the founding family maintains control. About a quarter of them have no outside directors other than the family, and the performance of these companies is about 15% worse than the market (i.e. the index). In the remaining group, family members only constituted about half of the outside directors.

Now, that group of companies regularly perform 15% better than the index. Guess which one you ought to buy as an investor.

So, now we have the Constellation Pitcairn Family Heritage Fund, open to the public as a no-load mutual fund. Its portfolio consists of fifty-five of those six hundred families dominated companies (with a market capitalization of at least $200 million each), selected by the Pitcairn Financial Company, entirely owned by the Pitcairn family. As long as it continues to outperform the index by 150 basis points, you can be fairly confident that the principle of family domination will endure, up and down the line. But not exclusively; it must be mixed with professional management. The family owns the fund manager, which is run by professionals, who watch the governance of the portfolio components, which are run by professional managers, overseen by founding family members on the corporate board -- themselves overseen by an equal number of non-family independent board members. It's like a Calder mobile, which by the way, is still another Philadelphia idea.

If you are looking to get rich fast, this isn't much of an idea. But since the Family Heritage Fund has consistently outperformed the index by 1.5%, it looks as though the advantage of selecting better corporate governance in the portfolio distinctly outweighs the disadvantage of reduced diversification.

Economics of La Cosa Nostra

|

| Angelo Bruno |

During all of the reign of Angelo Bruno, it was a common street opinion that The Organization tried to stay away from drugs, prostitution and shooting anybody except other mobsters. Some of that attitude is found in the scene of the movie The Godfather where a neophyte going to his first killing is instructed to "Watch out for those goddam innocent bystanders". It was okay to bribe the police, not okay to annoy them. Counterfeiting and kidnapping were big no-no's, even though counterfeiting was a core activity for the ancestral Mafia in Western Sicily during the Nineteenth century.

|

| Al Capone |

According to Robert Simone's book, the Philadelphia mob was mainly enriched by loan sharking. There are a lot of people who suddenly need cash desperately and can't get it quickly from banks. Simone himself was a compulsive gambler and frequently was in urgent need of money, either to throw it away or pay it back. Other people get caught in some illegal activity and suddenly need bail money to stay out of prison or up-front money for a lawyer. Or whatever. The Philadelphia mob had a reputation for being able to loan amounts of fifty or a hundred thousand dollars in response to a phone call, with home delivery of the money in fifteen minutes. For this, they would charge interest in the range of three percent a week, well above the usury limit, but probably not greatly out of proportion to the risk of loss. The police have little interest in transactions between willing parties, at least until the borrower fails to pay it back. Even at that point, it becomes a question of whether kneecaps will actually get broken, or baseball bats actually come in contact with skulls. Probably not very often, because the threat seems a credible one.

To run such a business requires large amounts of cash, hidden in safes or bricked up in walls. From this comes theft or attempted theft, with violent defense measures that often don't concern the police, much, unless those aforementioned bystanders get injured. Sometimes couriers get tempted to make unscheduled detours, but the police are fairly tolerant of informal restitution efforts. All in all, it's a nice clean illegal business.

An interesting sidelight is income tax evasion. It's entirely possible that The Organization would be willing to pay taxes if it could be done without filling out all those forms. Restaurants, bars, and market stalls can be run as a way to launder money and yet pay tax on it. But boys will be boys, and no doubt the IRS has, or had, some legitimate concerns. For years I felt the government was over-reaching when it jailed Al Capone for income tax evasion, after being unable, however, convinced it may have been, to convict him of overtly illegal activities. That's one side of it. But if you envision these organizations with millions of dollars in cash hidden away, it's easy to imagine them extending invisible credit to their associates for services rendered but not yet paid out and, of course, untaxed. Calling for such money on demand is not much different from having it in a bank. If appreciable amounts of that circumvention go on, the Internal Revenue Service really might have a grievance. Its image would be improved by demonstrating it is pursuing a named crime rather than a pretext to jail someone it doesn't like. Legislation could surely be devised which more carefully specified such illegalities. It might then be possible to bring an end to the appearance of putting people in jail for merely enjoying an ornate lifestyle. People who, almost by definition, cannot be proven to have committed a crime.

John Head, His Book of Account, 1718-1753

|

| American Philosophical Society |

Jay Robert Stiefel of of the Friends Advisory Board to the Library of the American Philosophical Society entertained the Right Angle Club at lunch recently, and among other things managed a brilliant demonstration of what real scholarship can accomplish. It's hard to imagine why the Vaux family, who lived on the grounds of what is now the Chestnut Hill Hospital and occasionally rode in Bentleys to the local train station, would keep a book of receipts of their cabinet maker ancestor for nearly three hundred years. But they did, and it's even harder to see why Jay Stiefel would devote long hours to puzzling over the receipts and payments for cabinets and clock cases of a 1720 joiner. Somehow he recognized that the shop activities of a wilderness village of 5000 residents encoded an important story of the Industrial Revolution, the economic difficulties of colonies, and the foundations of modern commerce. Just as the Rosetta stone told a story for thousands of years that no one troubled to read, John Head's account book told another one that sat unnoticed on that library shelf for six generations.

|

| Colonial Money |

The first story is an obvious one. Money in colonial days was mainly an entry in everybody's account book; today it is mainly an entry in computers. In the intervening three centuries, coins and currency made an appearance, flourished for a while as the tangible symbol of money, and then declined. Although Great Britain did not totally prohibit paper money in the colonies until 1775, in John Head's day, from 1718 to 1754, paper money was scarce and coins hard to come by. Because it was so easy to counterfeit paper money on the crude printing presses of the day, paper money was always questionable. Meanwhile, the balance of trade was so heavily in the direction of the colonies that the balance of payments was toward England. What few coins there were, quickly disappeared back to England, while local colonial commerce nearly strangled. The Quakers of Philadelphia all maintained careful books of account, and when it seemed a transaction was completed, the individual account books of buyer and seller were "squared". The credit default swap "crisis" of 2008 could be said to be a sharp reminder that we have returned to bookkeeping entries, but have badly neglected the Quaker process of squaring accounts. As the general public slowly acquires computer power of its own, it is slowly recognizing how far the banks, telephone companies, and department stores have wandered from routine mutual account reconciliation.

|

| John Head's Account Book |

From John Head's careful notations we learn it was routine for payment to be stretched out for months, but no interest was charged for late payment and no discounts were offered for ready money. It would be another century before it became routinely apparent that interest was the rent charged for money and the risk of intervening inflation, before final payment. In this way, artisans learned to be bankers.

And artisans learned to be merchants, too. In the little village of Philadelphia, chairs became part of the monetary system. In bartering cabinets for the money, John Head did not make chairs in his shop at 3rd and Mulberry (Arch Street) but would take them in partial payment for a cabinet, and then sell the chairs for the money. Many artisans made single components but nearly everyone was forced into bartering general furniture. Nobody was paid a salary. Indentured servants, apprenticeships trading labor for training, and even slavery benignly conducted, can be partially seen as efforts to construct an industrial society without payrolls. Everybody was in daily commerce with everybody else. Out of this constant trading came the efficiency step for which Quakers are famous: one price, no haggling.

One other thing jumps out at the modern reader from this book of account. No taxes. When taxes came, we had a revolution.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1517.htm

David F. Bradford, 1939-2005

|

| David Bradford |

We should take the word of his friend and colleague, Daniel Schaviro, that the core of David Bradford's professional career as an economist was his conviction that a very deep wrong existed when two people could earn exactly the same income over their lifetimes but the one who spent every cent immediately would pay less in taxes than the other who carefully saved for his retirement and heirs. Bradford was offended by this message our society was broadcasting.

Working for a time in the U.S. Treasury Department and later as a member of the President's Council of Economic Advisor's, he was able to explore the mechanical workings of tax law well enough to translate moral conviction into a workable proposal for political reform. In 1977 he published "Blueprints for Tax Reform", introducing these practical ideas at the highest level of academic rigor. The impact of his ideas in this paper extended through three presidencies, particularly the present one.

Bradford saw the tax injustice which penalized the Protestant ethic could be corrected in two ways. Either the tax code could shelter individual savings from taxes until they are spent (the IRA), or else convert the income tax into a consumption tax (like VAT). In either case, taxation would take place at the same time as consumption, rather than at the time of earning. Notice the person who saves money to spend later will suffer from both inflation and taxes on taxes on the inflation "gains". The political choice between the two proposed solutions was made by Senator William Roth (R, DE) who sponsored the Individual Retirement Account (IRA) and shepherded it through an intensely political Congress. His was a wise decision, since its voluntary nature made it attractive to politicians, while the French experience with a mandatory Value Added Tax (VAT) created political opportunities to favor certain industries, which politicians were quick to understand.

After twenty-five initially slow years, the eventual popularity of the IRA has now encouraged its extension to Social Security. That's what agitates domestic policy debate at the time of David Bradford's unfortunate death. The IRA model is also the basic concept underlying Health Savings Accounts (HRA), which struggled for many years but have reached their own period of growing acceptance. The Blueprints idea has thus dominated domestic politics for nearly three decades, while its originator remained largely unknown. Far from being a sign of weakness of the idea, it is a proof of the revolutionary nature of this simple concept that it initially provokes public resistance, but also inspires relentless tenacity among those who have taken up its challenge.

David Bradford returned to Princeton from his Washington experience, resting for decades at the quiet center of an Economics department that is not known for its quietude. After a most unfortunate fire at his home, he died of the burns in nearby Philadelphia, which hardly knew him.

The Minnesota Investment Standard

|

| Wall Street |

The performance of mutual investment funds is commonly compared with the stock market as a whole, or some surrogate index of it. The uncomfortable thing is that successful funds grow, and when they get big enough, they just have to resemble the market as a whole. Subtract some fees and expenses, and they are the market. If there is no substantial difference between a managed fund and an unmanaged one, job security for investment managers comes into serious question. You would expect to hear a lot of gallows humor about a situation like that, but in fact, it is largely treated as too painful to mention. Except perhaps, by Quakers.

One highly successful veteran of multiple famous Wall Street boar dooms is not a Quaker, but having spent twelve years in Quaker schools certainly talks like one. His brand of humor has brought many weighty meetings to a halt, and in this case, he has developed what he calls "The Minnesota Investment Standard." The allusion is to the little town that Garrison Keillor made famously, where all of the women are beautiful, and all the children are above average.

"In this remarkable case, however, all the mutual funds seem to perform below average."

Mutual Fund Governance

|

| Mutual Funds |

Unfortunately, mutual funds' main advisory revenue often or even usually comes from selling the fund they work for to corporate pension systems. Although the money belongs to the employees, the choice of fund is usually left to the employer. The revenue of that fund, and hence the revenue of that fund's management adviser firm, is based on the volume of assets; the bigger the fund, the more they all are paid. For the most part, corporation managements can readily change the mutual funds which handle employee pension savings. Consequently, If word gets around that some fund manager often votes the proxies against corporate management in proxy fights, there's ample opportunity for retaliation. So, effective reform of both corporate governance and mutual fund performance seemingly must either exclude corporate management from the selection of employee pension advisers or else from the right to vote the proxies. However, that's too simple. The unspoken bargain is "If you don't criticize our performance (and reimbursement), we won't criticize yours."

A Single International Currency?

|

| It's Only Paper |

The Economist, printed in London, refers to the United States in its October 17, 2011 edition as the "World's largest currency union", but goes on to state it only became a true currency union in the Presidency of Franklin Roosevelt. That's sort of the case, even though most people suppose Alexander Hamilton unified American monetary affairs with the Compromise of 1790 which among other things traded the nation's capital away from Philadelphia. No, Hamilton only unified the Revolutionary War debts, which to be sure, at that time were the main debts of the new nation. In time, the country and the economy grew in size until our currency was no longer unified because the individual states and banks were legally free to issue their own money. Nicholas Biddle of the Second National Bank had an irritating habit of buying up the circulating currency of a weak bank and presenting it as a bagful to the teller's window. If the bank was really overextended, it then went bankrupt, and other marginal currency-issuers could observe a bitter stress test about printing unreserved paper money. According to The Economist, the main stabilizer was not a migration of money, but the migration of workers. Unemployed people by the many thousand would move to a state or territory with a labor shortage, a solution made practical by the extremely low cost of real estate. In Europe, a far more practical adjustment remains the moving of funds from one state to another, although there is today enough migration across the Mediterranean to demonstrate how disruptive it is to mix extremes of unwelcome language, religion, and culture. In comparing the American and European experiences we thus have two quite different systems to compare, although distinctive conditions often bring out the main issues. The problem of maintaining a common currency union, for example, is hard enough, while the Europeans have the similar but not identical problem of devising a stable one from a large number of different ones.

After three hundred years of fumbling America has perhaps muddled through to a currency union that works. Resting on the fact that most Americans are either debtors or creditors and the rest mostly don't care, the quantity and value of American dollars since 1913 have been negotiated between banking and the U.S. Treasury with the Federal Reserve as umpire. During that last century we have endured two major depressions and a dozen recessions, abandoned the gold standard and fought a number of wars; but the American currency union has never given serious signs of weakness. It would appear that the main problems with currency unions appear at the beginning, in putting them together. After the transition, things appear to get easier. Bank profits are improved by higher interest rates, while all governments, perpetually in debt, want lower ones. Ultimately, of course, the real tension is between the creditors and debtors, but banks and Treasury seem adequate surrogates. Most creditors place trust in the incentives of banks to prevail, debtors trust government; both sides should have learned trickiness in endless negotiations is futile. What was once a battlefield, is now mostly peaceful; these people actually respect each other. Many people may occasionally dislike an outcome, but all acknowledge the tension produces legitimate compromise.

|

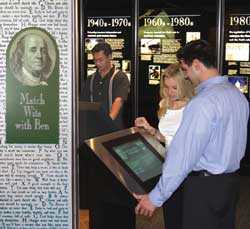

| Match Wits with Ben Franklin |

Aside from some "don't ask, don't tell" mystery that somehow compels assent by regions of the country who feel betrayed by agreements their representatives have made, negotiating postures are pretty simple and clear. It is safely assumed the government wants to inflate; all governments have done so for thousands of years. Therefore, the basic Federal Reserve policy of targeting interest rates to restrain inflation is probably a concession to banks. Banks would mostly want the highest rate that does not cause a recession. Debtors do not mind lower rates leading to just a little inflation, hoping to pay off their debts later with cheaper money. Government, acting as an agent for debtors, additionally knows that rampant inflation loses elections and occasionally, as in inter-war Germany and Austria, destroys the middle class. So, with everyone else resisting inflation, debtors must be satisfied with 2% annual inflation. That's arbitrary, reflecting its origin in the haggling process. Inflation-targeting plus two percent; that's the system.

If only there weren't all those other countries in the world. If they inflate or deflate, we could just float our currency exchange rate to maintain international trade; that isn't so bad, although frequent readjustment of prices is a costly nuisance. But if some country freezes its currency at an unrealistic price, speculators will move money around to take advantage. Enter Gresham's Law (commonly expressed as "Bad money drives out the Good".) Gresham's original phrasing is actually apter: "When two currencies of unequal value circulate together, the good currency quickly disappears." So, when truant governments cheat on currency values, well-behaved countries find their own currency getting hoarded. Potentially, that leads to currency shortages, as happened to Argentina when Brazil devalued in 1999. So, countries running an honest currency nevertheless feel pressure to print more; Brazil "exported its inflation" to Argentina. Plenty of wars have been started for less provocation. When something causes that extra money to come out of hiding, there will be spreading inflation, notwithstanding attempts to isolate foreign inflation by the central banks of more responsible nations. Furthermore, runaway inflation can unsettle governments, as it did in the Argentina example, going from one extreme to the opposite. There is thus wide-spread sympathy for currency unions, even though locally independent currencies can sometimes better adjust to local commotions, typically by devaluing the currency and then rejoining the currency union at a more realistic price. The Federal Reserve in our case would be forced to raise interest rates sky high, promptly triggering housing and stock market crashes. So the point returns; if our Federal Reserve system works so well, why can't everybody does the same thing on an international level. In fact, what's the matter with having one big world currency?

Maybe, some say, we could have a World Reserve Bank, issuing a common international currency. What we now have in place is U.S. money serving as a Reserve Currency for the world. The force behind this system is again Gresham's Law, that since we have the strongest currency in the world when it circulates in other countries in the company of weaker local currencies, it quickly "disappears". That is, it is hoarded out of sight until nothing but local money remains visible. Under these circumstances, only the United States with the world's Reserve currency is able to print money without creating inflation. Unfortunately, that implies that if it should ever weaken, it will quickly reappear and flood the host country with inflation, whereupon the host government will ship it all back to enjoy your own inflation, thank you. Thus, being the reserve currency for the whole world allows you to have some inflation and ship it abroad, but if it ever comes back home, there could be a painful disruption. The last time this happened was when the British Pound surrendered the reserve role to the American dollar. It was a bad time for the British economy.

The question periodically arises whether it might be better to use a "basket" of currencies as the reserve against temporary monetary shortages, with the United States trading away some of its free ride on inflation in return for reducing the risk of someday getting it all back at once.

Using a basket of everybody's money as a pool of international reserves might smooth out the tidal waves, but it probably would not create the same stability from tempests we enjoy with the Federal Reserve. If you regard a country's money supply as one big short-term bond, then a basket of currencies is a basket of bonds, issued by a world full of debtors. In that situation, pressure for worldwide inflation is inevitable. In a world with nationalized banks and/or subsidized banking systems, it is hard to imagine any international banking voice without a strong political component. Mandatory contributions of gold bullion might be considered, but it is hard to think of an adequate substitute for the flexibility of adversary tension between permanent creditors and permanent debtors. The situation is not permanently hopeless however, just remote. The enduring risk is that some nations always have more to lose from a collapse of trade than others. Continuing improvement in world economic conditions may one day make a unified world currency feasible. As St. Augustine famously said, "Make me chaste, but not yet."

REFERENCES

| Runaway America: Benjamin Franklin, Slavery, and the American Revolution, David Waldstreicher ISBN-13: 978-0809083152 | Amazon |

Delaware's Court of Chancery

|

| Chancery |

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble.

Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries.

Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

|

| George Read |

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy.

Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision.

But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Chancery's jurisdiction was complementary to that of the courts of common law. It sought to do justice in cases for which there was no adequate remedy at common law.  |

| A. H. Manchester Modern Legal History of England and Wales, 1750-1950 (1980) |

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude:

"The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue."

That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril.

Finances of the Girard Estate

|

| Stephen Girard |

Stephen Girard died on December 26, 1831. It required 7 years for executors to settle the estate of this richest man in America, valued at $7 million, of which $5.25 million was to establish a school for poor white orphan boys. Two million dollars of that was set aside in the will for the construction of his new school. Considerable criticism was raised about the fact that the various administrators of his estate did not admit a single student for the first sixteen years, during which time extensive trustee tours of Europe were conducted to study suitable models and publish books about them. At the end of that time of preparation, the two million dollars were just about all gone. It turns out that Girard could actually afford this luxurious approach. In 1886 the estate would rise in value to $11 million, in 1914 it was worth $30 million. In 1926 it was worth $73 million. This appreciation was in spite of educating more than 10,000 boys, and also purchasing and repaving (with Belgian blocks) both Delaware Avenue and Water Street, from Vine to South Street as a public service to which more than $2 million was devoted. In 1935 Cheesman Herrick wrote a history of Girard College, in which is found the following, rather delicate, history of the long-term financial management by the Board: "The Board of Directors of City Trusts is a creation of the State of Pennsylvania. At the outset in the administration of the Girard will, the city authorities looked to the state Legislature for an empowering act to proceed with the organization of Girard College. The same authority [then] set aside the control of the City councils and put the Girard Estates and Girard College under a new Board which became a part of the machinery of the city government. Probably no more successful administration of public trusts has ever been known than that by the Board of Directors of City Trusts. Time has known the wisdom of Stephen Girard in leaving the administration of his estate as he did. "Colonel Alexander K. McClure, who knew Philadelphia well and who was relentless in his inquiry as to the discharge of trusts by public officials, paid the Board of Directors of City Trusts a deserved compliment in saying that no shadow of doubt or suspicion had ever fallen upon the doing of that body. It may be added further that probably no other government agency or private business enjoys a higher reputation for integrity and efficiency in the conduct of its affairs that does this Board. That this record is good is owing primarily to the standard set by those who have served under the Board in various business and administrative positions.

"When the record of the Board is taken into consideration, and the magnitude of the work which it has to supervise is regarded, one can readily see that service on this Board is a signal distinction. The list of the Board has been a sort of honor roll of Philadelphia's foremost citizens. That the standard in this Board has been so high and that members of the Board have served so faithfully, have been due in no small part to its members' having seen beyond the millions of Stephen Girard, and numerous other funds which they have handled, to the great good which these various trusts are accomplishing. With the interest of the beneficiaries always in mind the Board has conscientiously sought to make the Girard Estate, and the other foundations under its supervision, serve the community to the greatest possible extent. The idea of service has been the touchstone making the Board of Directors of the City of Trusts a great Board." Starting with Nicholas Biddle, the Board of the institution was certainly composed of men who had distinguished themselves in business and finance. However, a great deal of credit must be given to Stephen Girard, himself. A year before he died, he bought roughly 18,000 acres of Schuylkill County after the discovery of coal outcroppings on the property. In subsequent years over a hundred million dollars of anthracite coal were extracted by the mining agents of the Girard Estate, based in Pottsville, PA. The clean-burning properties of this form of coal were promoted with the image of "Phoebe Snow", and were the basis for much of the industrialization of the region. Coal came down the Schuylkill River on canal barges with a terminus opposite the present boathouses, hence the Lighthouse adorning Sedgwick, the most northern boathouse. Later, it was carried on the Reading Railroad, which at one time was the largest railroad in the nation. The Girard heirs felt this went far beyond Girard's contemplated income from the estate, and went to court to obtain for themselves what they considered a more appropriate share of it. Their argument boiled down to saying Girard College had so much money it didn't know what to do with it and was returning income to principal. It was their contention that if Girard could have predicted both the revenue and the expenses of the school, he would have left the school less money, and given more to his numerous heirs. The managers of the estate, who felt their own acumen was largely responsible for the windfall, made a sophisticated and ultimately successful rebuttal. Instead of relying on the contrast between the incredibly good performance of the Board of City Trusts, compared with the earlier looting of the estate by City Council, their lawyer

|

| Horace Binney |

(Horace Binney) relied on and largely invented some important legal reasoning. Coal in the ground was a dwindling asset, and speed of its dwindling was under the control of the owners. The managers of Girard's estate had shrewdly transformed the coal into a more conventional source of income by taking proceeds at the best available price, regardless of the needs of the school. With it, they put up office buildings and department stores in the center of Philadelphia on the land around 12th and Market, first intended to be the site of the orphan school. Also, the six hundred acres of Girard's farm in South Philadelphia were converted to rental houses. In time, the income from the coal-bearing properties was transferred to center-city rentals -- all within the bounds of real estate which Girard had purchased before his death. The trustees had enhanced the value of Girard's properties by shifting assets amongst them, a result that greatly benefited the entire city and region, and rendered the entire concept of annual income -- irrelevant. The legalisms of this dispute are very clever, but in truth, the Girard's heirs probably never had a chance in court against the political and business establishment of the whole state, united in the firm belief they were doing a remarkably benevolent thing for orphans. It is breath-taking to reflect that Girard College's anthracite did become the economic pump for the entire Philadelphia industrial region from Pottsville to Trenton, for nearly a century. And equally breathtaking to reflect that, about a century later, anthracite mining just about ceased entirely. Although there was shrewd later management of the assets, the fact is the coal was discovered, purchased and bound up in irrevocable covenants by a single man in 1829, who was therefore dead during every day of this activity, except during the first year when the plan was organized. If he wanted to do this for orphans, it is scarcely possible even to suggest a reason why he shouldn't.

REFERENCES

| Girard College It's Semi Centennial of Girard College: George P. Rupp ASIN: B000TNER1G | Amazon |

IRA ... Individual Retirement Accounts (3)

|

| TSR-80100 |

It wasn't Ronald Reagan on the phone, it was John McClaughry, Senior Policy Adviser. I'm not sure how important you are when you are a Senior Policy Adviser, but it rates you an office in the Executive Office Building that has fireplaces and sofas, conference tables, and -- off in one corner-- a desk. I knew at a glance that we were going to be friends, because his desk had a Radio Shack TRS-80 computer on it, too. Seeing that, emboldened me to stuff my temporary White House identification badge in my pocket, because a guy with a computer in 1980 was certainly a member of the brotherhood, and would get me out of trouble if the guards caught me taking souvenirs. I still have the badge.

John was and is a master networker; maybe that's the job description of a senior policy adviser, I wouldn't know. He knew everybody who had anything to do with health financing, in all the branches of government, including one I hadn't known about, the neighborhood Think Tanks. Everybody is forever passing out business cards to new acquaintances and sweeping them into the left-hand breast pocket in one continuous motion. In Japan, everybody passes out cards but makes a big bowing ceremony of receiving them; what then happens to them in Japan I don't know, but in Washington, they go into Rolodexes and everybody invites everybody to some gathering or other. One evening, I was the entertainment at such a gathering, and have usefully kept up with quite a few people who attended. It's a different atmosphere from some other functions, particularly in the State Department with the other party, where everyone pretends to be meeting you for the very first time when they really aren't.

A few days after our first meeting, John wrote me a short note. Senator Roth of Delaware was pushing something called IRA, or Individual Savings Accounts. Did I think the idea could be applied to health care financing? I suddenly felt as though someone had shoved a stick into my skull and was stirring it around. Of course, just perfect! Add that to a high-deductible or so-called catastrophic health care policy, and out would emerge individually owned health insurance policies, with the same tax shelter as Blue Cross gets, and the added kicker of earning compound interest while you are well, in anticipation of high costs when you are older. It gets rid of pay-as-you-go, it puts an end to "job-lock" and all sorts of other bad things. Perfect.

Because of the difference in our previous backgrounds, I was in a little better position than John was to see how many medical pieces would fall in place if you made this simple provision, which after all was only giving to self-employed people what salaried people had been getting for decades. Yes, it had a small cost, but no more than the amount self-employed people (like doctors) were being cheated out of. We were only asking for a level playing field.

John and I had our project, the Medical Savings Account, and although we kept in touch, we went our separate ways to sell it. John's field was the Republican Party, and mine was the medical profession. It might take a year or two, but the arguments were unassailable.

Opposition to Privatized Social Security

|

| The Brookings Institution |

The counter-attack on personal accounts was instantaneous, vociferous, and distorted. It alleged what was clearly not true ("taking our social security away from us"), and failed to bother about more plausible threats (entitlements like Medicare seem likelier targets of fiscal stringency). There is no history of similar agitation about IRAs. or other tax-sheltered savings incentives of the same model and no claims have been made that such programs have caused problems. This uproar seems to emanate principally from AFL/CIO headquarters in Washington, where Mr. Sweeney seems to be the leader. Labor Unions are spending considerable money and effort to stifle this proposal before it can develop momentum. The Brookings Institution contains people like Henry Aron and Reischauer, who surely understand the true issues involved, but have apparently retreated into silence. What is there about this relatively tame proposal, not particularly useful nor particularly harmful, which threatens the interests of organized Labor?

|

| Teamsters |

With no plausible incentives in sight, we resort to speculation about motives. Either Labor suspects President Bush of devious plans, or has devious plans of its own. The most obvious motive a Republican President might have, and one which is more or less acknowledged, is to "starve the beast", or force reductions in government spending by tax-cutting deficits. However, privatized retirement accounts would not seem to be a very plausible move in that direction.

More likely, Labor has its own interests in the benefits and retirement area that seem threatened by privatized accounts. The notorious retirement fund of the Teamsters is only one example of the long-standing involvement of unions in member benefits. Aside from funds directly controlled by unions, their involvement in Blue Cross boards and negotiations, and their influence on state employee retirement funds has been highly treasured. Workers Compensation is another example of heavy union influence in non-paycheck member compensation. Indeed, it is roughly the case that unions control the employees, while the stockholders control the management. There is imperfect agency in both cases, but until recently it has not been conceivable that unions would dominate corporate directors. But with progressive dispersal of stockholder shareholding and recombination of those voting rights into mutual and pension funds, even the House of Morgan can be seen to appeal to pension fund managers for control of the company. We've turned over a flat stone in corporate governance, and what is crawling out is the source of some concern.

To some extent, the same issue is raised in the Human Resources departments of corporations, constantly exercising delegated control over employees, and constantly in contact with insurance and pension executives of various ranks. Management controls or thinks it controls, two-thirds of employee income, but HR controls the remaining third, spending most of it on insurance plans of one sort or another. At the board level, mutual funds generally lean toward management whenever pension funds raise stockholder rights issues. But index funds and government savings plans could easily induce some subtle changes in sympathies.

It's speculative, of course. But is it possible this is the real battleground, with partial privatization of social security only an opening skirmish?

Put Corporate Raiders to Some Good Use?

|

| Henry G. Manne |

Henry G. Manne just made an interesting proposal for re-setting the balance of power between corporate executives and their bosses, the stockholders. It appeared on the Opinion page of the Sept. 27, 2005 Wall Street Journal. In essence, Mr. Manne, a resident of Naples, Florida and Dean Emeritus of the George Mason University School of Law, suggests we forget about giving stockholders and independent corporate directors more oversight power. Instead, make things easier for corporate raiders, who will be glad to terrify rambunctious executives with a credible threat of having raiders for bosses. It's an interesting thought.

Whoever puts headlines on articles submitted to the

|

| hedge fund |

Journal called this one The Follies of Regulation. We can presume the headline writer prefers corporate raiders to Sarbanes-Oxley, or to the 1968 Williams Act, or a variety of state (read, Delaware) takeover laws, or the Investment Act of 1940, or potential regulatory curbs for Hedge Funds. Although he seemingly agrees with that, Mr. Manne's case is somewhat weakened by having a political spin applied. Regulation isn't the solution, regulation is the problem.

The case is stronger than that, because the main origin of the so-called "Agency Cost" problem appears to lie in the relentless growth in size of international corporations,

to a point where shareholder power is necessarily diluted too thin to be effective. If you exclude founders of corporations and maybe a few families of founders, the dilution of stockholder power has long been an inevitable feature of the dilution of stockholder ownership. If you want their money you must meet their terms, which are overwhelmingly tilted toward passive investing. It's going to get even worse; John Bogle at Vanguard has convinced just about everyone that index investing is the most cost-effective way to invest in equities.

And since the underlying issue is the servant betraying his master (read, Agency Cost), it does not help much for stockholders to ally themselves with new agents.

|

| grease sale |

That would include the managers of Hedge Funds (read, Private Equity), or New York Attorneys General, state employee union presidents, mutual fund managers -- or revolving-door employees of regulatory agencies. There's a rumor around that investment bankers were the ones who first suggested bribing the managers of acquired companies to grease the sale. Where agents of any kind are concerned, particularly elected representatives, you dare not turn your head to spit.

The interesting thing about Mr. Manne's proposal is that his suggestion of trusting the corporate raiders might just work. You can trust them to work hard and play hard, and be utterly remorseless about the poor beleaguered corporate executives, those home town boys who have worked so hard on your behalf. Or who "live like monks, and give all the company's wealth to worthy causes."

Let's hear more specifics about how to do this, and expose them to the anguished howls of those they might injure. The hubub alone would do some good.

Retiring to the Workforce

Most Americans alive in 2020 will live to be ninety

|

| Dr. Fisher |

During the Twentieth century, average life expectancy for Americans at birth extended from a little less than age fifty, to a little less than age eighty -- roughly thirty years. Looking ahead to the next century, it's entirely reasonable to expect a cure for cancer and Alzheimer's disease to extend life expectancy to ninety-five. It's also reasonable to expect that somewhere along this path we will find such retirement expectations are more than the nation can afford. Everyone will have to go back to work.

Working ten years longer means ten years less time in retirement, and it also means ten years more time to accumulate sufficient savings for whatever time is left. Some people who are already working more than they want to, won't like that. There will be attempts to make retirement cheaper and to extract savings from novel sources, but further improvements in health care will wipe out all those efforts. The normal age for retirement will have to move to at least age seventy, probably seventy-five. If employers have problems with that, the solution will have to be second careers. So, let's shift our attention to people who are lucky enough to afford a thirty year vacation. They must go back to work, too.

A moment's reflection reveals that everyone must have a life goal of accumulating more money than is needed to live out his life. Once average life expectancy levels out to a stable point, ingenious life insurance design could bring us to the point of spending the last dime on the last day, providing we consider it worthwhile to spend the extra insurance administration cost. More likely, human psychology will always demand a little extra comfort from a little extra financial cushion, and there's a relationship with the age of retirement. The later you retire, the more likely it is you will have money to spare. For physical or mental reasons there will be people who can't work, but everyone else knows a simple solution to the problem of being able to retire: don't stop working until you can afford to quit. And by the way, the later you start saving, the longer before you can quit.

This vision of elderly America thus generates a need to create new jobs for people unable to retire, but the similarly growing number of elderly too infirm to work creates jobs for the advancing number of elderly who need a new career. Some variation of a voucher system will be needed to make this workable.

We have so far not worried much about the lucky, talented, or just miserly few who achieve life's normal goal of saving just a little more than they need; but that must change, they need to go back to work, too. Philanthropy, a very important part of American life, is struggling and needs their talent. It's likely that our business and economic success as a nation is responsible for diverting our energetic and imaginative talent toward the for-profit sector. The general attitude has been that if things are worthwhile, people will pay for them; businesses run not-for-profit can't really be worth much. That's very wrong, of course, but there's enough truth to it to require some changes.

Nonprofit organizations are often inefficient because efficiency is partly the consequence of seeking a profit. But the analysis must not stop with this hopeless truism; the manageable problem is to find new goals for efficiency which do not directly require profit-seeking. One approach would be for non-profits to create for-profit subsidiaries, later selling them off to enhance their endowment. The tax authorities would want to examine this approach to avoid harming competitive tax-paying entities, or sham arrangements in which the purported subsidiary dominates a nonprofit shell.

However, this and similar approaches merely continue the present mindset about the role of the donors and the volunteers. Nonprofit organizations tend to gravitate toward a professional staff with nominal trustee oversight, relegating the donors to the function of giving or getting donations. If philanthropy is to acquire a new drive toward efficiency to supplant the absent profit motive, the donors must be actively employed in the organization, noticing any waste or inefficiency, sharing the gossip, and appreciating the triumphs. To some degree, a form of this model is found in the auxiliaries of hospitals and museums, where staff administrators generally chafe in private about the class distinctions and disruptive ability to cut across management hierarchies. If this system is to work effectively, it needs to be studied for ways to be less threatening to the younger employees, and to get more useful work from the older ones.

Who Watches the Watchmen?

The Latin phrase Quis custodies custodies warns that it's pretty hard to find hired agents you can completely trust. Investing for your retirement, you must be careful to avoid excessive transaction fees to pay your agents and minimize taxes to pay your government to watch your agents, who in turn watch the companies they invest in. Those companies are managed by hired experts, who are selected and overseen by a board of directors. The agents hired by the investors are charged with overseeing this process.

Gradually, the world is coming to accept John Bogle's idea of a market index fund as the best most people can do. Index funds don't even try to tell a good one from a bad one; they just buy them all in proportion to their size (successful companies grow, unsuccessful companies shrivel). Investing in the whole market,an index fund doesn't do much trading, seldom buying or selling. Therefore, it has minimum costs, minimum taxes. As a by-product, it has maximum diversification, hence maximum safety. Low costs and high safety don't automatically give the best performance, except that somehow they do. The Index Fund idea just relentlessly outperforms the vast majority of investment advisers, in both up-markets and down-markets. Investment advisers just hate index funds, bad-mouthing them constantly. But if you buy anything else, you had better have a very good reason to do so. The performance of an index is called beta; outperforming the index is called alpha. The sad truth is that most experts have a negativee alpha.

Well, it's just possible that a second Philadelphia-born idea can do the seemingly impossible task of showing a small but consistently positive alpha. The Pitcairn Foundation was created for his family by John Pitcairn, one of the world's all-time champion investors. About fifteen years ago, the Johnny Appleseed spirit caused the Foundation to open up its investment approach to non-family members; they created a public mutual fund company based on the collective ideas and experiences of the Foundation. John Pitcairn bought the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, nurtured it to success as PPG Industries, and then eventually sold it, based on the observation that almost no firms, family owned or otherwise, survive more than seventy-five years. Companies should be bought with the intention to sell them, even though they are managed expertly throughout their existence.

The Pitcairn Foundation observed that continuing dominance by a founding family almost always proved beneficial for the running of the company by hired expert managers. Notice that, while nepotism was often a bad thing in the managers, it could be a useful thing in governance. If you go too far with this idea, of course, you may get into the stifling arrogance of family control in European and Oriental firms. Founding family control keeps the managers from over-paying themselves or worse still, under-working themselves. But outside investors better watch these founding families; if you allow the inevitable minority of worthless family members to pilfer the company, you get the same thing at a different level of control, where it is even harder to fire them. There's a good idea here, but it needs a little extra.

After a great deal of intense scholarly work, it was observed that there are about six hundred major American corporations available for public participation where the founding family maintains control. Even this select group comes in two types. About a quarter of them have no "outside" directors other than the family, and the performance of these companies is about 15% worse than the index, suggesting the dominance of playboy directors. In the remaining group, family members only constituted about half of the outside directors. Now, that group of companies regularly perform 15% better than the index. Guess which type you ought to buy as an investor.

So, now we have the Constellation Pitcairn Family Heritage Fund, open to the public as a no-load mutual fund. Its portfolio consists of fifty-five of those six hundred families dominated companies (with a market capitalization of at least $200 million each), selected by the Pitcairn Financial company, entirely owned by the Pitcairn family. As long as it continues to outperform the index by 150 basis points, you can be fairly confident that the principle of family domination will endure, up and down the line. But not exclusively; somewhere it must be mixed with professional management. The family owns the fund manager, which is run by professionals, who watch the governance of the portfolio components, which are run by professional managers, overseen by founding family members on the corporate board -- themselves overseen by an equal number of non-family independent board members. It's like a Calder mobile, which by the way, is still another Philadelphia idea.

If you are looking to get rich fast, this isn't much of an idea. But since the Family Heritage Fund has consistently outperformed the index by 1.5%, it looks as though the advantage of selecting better corporate governance in the portfolio distinctly outweighs the disadvantage of reduced diversification. Maybe that's all it proves, but most of us poor saps don't even know that much.

Will Tax Cuts Invert the Yield Curve?

For those who just came in, let's explain a normal yield curve, and then an inverted one. In plain English, average interest on short-term bonds is normally smaller than average interest on long-term bonds, so a line drawn between them slopes upwardly. This reflects the reality that the risk of something going wrong is less in a short time than during a long one, so an up-trending yield curve is what emerges when everyone leaves interest rates alone. However the Federal Reserve has for a century adjusted short-term rates according to its view of whether banks should do more or less lending, whether inflation should be encouraged or discouraged, or whether the banking industry needs more or less profitability; sometimes these goals conflict, and sometimes the Fed is merely trying to maintain a stable spread when long term interest rates shift in response to market forces. In average circumstances the marketplace alone controls long term borrowing costs by supply and demand; long term rates are whatever they happen to be. However, Chairman Bernanke has introduced what he calls "Quantitative easing", which is to intervene directly in long term pricing by purchasing and selling long-term bonds. Therefore, the slope of the yield curve can reflect many motives; it's hard to deduce motive from changes in the slope of the yield curve alone. Indeed, suppose it doesn't have much to do with economic forecasting at all. Suppose it just reflects tax cuts.

After all, when federal taxes are reduced, rates can eventually approach the point where bond interest is essentially tax-exempt. Paying more interest, long-term rates are thus normally affected more than short ones by the change. However, a preponderance of U.S. Treasury bonds is now purchased by foreigners who are indifferent to our tax rates. It's clear, however, that cutting taxes will lower bond market interest rates in the general direction of tax-exempts. Although tax reduction is capable of inverting the yield curve, it may no longer do so, and the Federal Reserve may be relieved of lowering short term rates to maintain balance.

If there is anything to this idea, the yield curve might have inverted without a tax cut. That's because a majority of U. S. Government bonds are lately being purchased by Asian governments. The Chinese government doesn't pay U.S. taxes, so to them, all American bonds are tax-exempt. Federal bonds are a little safer than municipal government bonds, so they should command a little lower interest rate, and may eventually depress the yield curve still further.

By this line of reasoning, an inverted yield curve is no longer a reliable portent of trouble, because it no longer primarily reflects American owners of the bonds dumping them. It has some important consequences, however. If interest rates are lower, retired people, insurance companies and pension annuities will be financially worse off. Borrowers, however, will be better off, and within limits, the economy will be favorably stimulated. One can be uneasy about the overall effect on the real estate and insurance markets, and on the temptation to governments to borrow more than they can repay. As different segments of the population are affected differently, the main outcome might well be a political one.

There are, from this example, lots of mixed consequences to be expected from a general readjustment (?reform?) of tax rates. But it shouldn't be a mystery that tax consequences affect yields, yield curves, and politics. That effect may not even be a conundrum.

Marty Feldstein Forecasts the Future

|

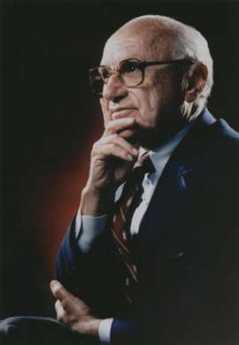

| Martin Feldstein |

With increasing frequency, the op-ed pages of the Wall Street Journal are opened to important people or important ideas. On April 28, 2006,Professor Martin Feldstein of Harvard wrote an article which purports to show how it is possible to have the American currency fixed for Americans but float for foreigners. After reading it twice, I conclude he is saying something rather different, and softening some startling announcements with circumlocution. It is my view that he says the following:

Inflation is not a worry; targeting 2% inflation with adjustments in short-term interest rates will take care of it.

International trade deficits need not be a worry, either, if only the Treasury Department (Could he mean nice old John Snow?) would allow the dollar to float on the international market. Not pure floating, of course, because it is a dirty world out there. The necessary dirty floating might hurt at first, especially American global businesses, but the sooner the boil is lanced, the better we will be. American exports of capital goods, consumer goods, and industrial supplies will especially benefit. Those who worry that trade deficits will weaken the dollar have got it backward a weaker dollar will correct the trade deficit. Yes, some people will be hurt by this.

In particular, high-wage countries like Europe, Canada, and Japan will be hurt, possibly severely hurt.

You will be able to tell that this plan has been set in motion when you see an international conference called among low-wage countries. The main purpose will be to reassure them that the U.S. Treasury won't punish them for strengthening their currency.

You will be able to tell this proposal has been rejected, probably for political reasons, if nothing soon happens to soften housing prices. And the word soon is emphasized. Because if they don't soften, they will break.

Medicare/Health Savings Accounts Legislation

Rise and Fall of Life Insurance

|

| Hammurabi Code |