Related Topics

Investing, Philadelphia Style

Land ownership once was the only practical form of savings, until banking matured in the mid-19th century. Philadelphia took an early lead in what is now called investment and still defines a certain style of it.

Quakers: All Alike, All Different

Quaker doctrines emerge from the stories they tell about each other.

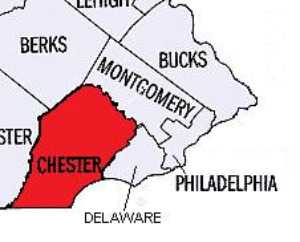

Chester County, Pennsylvania

Chester was an original county of Pennsylvania, one of the largest until Dauphin, Lancaster and Delaware counties were split off. Because the boundaries mainly did not follow rivers or other natural dividers, translating verbal boundaries into actual lines was highly contentious.

Chester was an original county of Pennsylvania, one of the largest until Dauphin, Lancaster and Delaware counties were split off. Because the boundaries mainly did not follow rivers or other natural dividers, translating verbal boundaries into actual lines was highly contentious.

Philadelphia People

New topic 2017-02-06 20:33:59 description

John Bogle, A Prophet In Our Valley

|

| John C Bogle |

Those who never met a living legend would have found in John C. Bogle a good place to begin, 80-plus years old, lively and very charming. The Vanguard Investment Company, which he founded, provides him a little think tank office, out of which have come several books and many articles (somebody else is running the company, now.) The drift of most of what he writes and most of his testimony to Congress, or at awards ceremonies, is that mutual funds charge too much. When the press decides to feature him, the spectacular theme is emphasized that in 1996 this current squash and tennis player was just about dead, and had a transplant of someone else's heart to keep him going. A populist graduate of Pre-Vietnam Princeton, and also the embodiment of a medical miracle, now, those things are newsworthy.

Future students of finance, however, will regard those things as minor footnotes. Bogle's real achievement was the invention of the index fund. Indexing had two purposes and probably stumbled onto a third. It combined diversification, low administrative costs, and outstanding investment performance in a single security. There will be foot-dragging in the boutiques and bucket shops, but this invention is well on its way to converting investment management from an inefficient luxury of the rich into an affordable efficient commodity for everybody. You will know that a fundamental has been established on the day when the U.S. Government starts buying index funds, or at least when it permits them to help finance Medicare or Social Security. Such invested funds of a government qualify for the term Sovereign-wealth funds; in fact, since major problems can be imagined if governments start to vote common shares, Heaven helps us if they don't stick to index funds. The investment community already knows that something basic has arrived, by their own standards. The original index fund will soon have a trillion dollars invested in it. Just do the math on what you would be paid if you realized a fifth of one percent, year after year, on managing a trillion. And then reflect on the impact on transactional costs generally, when many eminent firms still charge five times that much. To make barrels of money and still be a hero for making your product remarkably cheap -- now, there's a Philadelphia dream.

A technical explanation. Five hundred stocks as one lump are cheaper to buy and sell as a "program trade", and perform more smoothly, than any of them individually, because the ups balance out the downs. Transaction costs are less, because there is hardly any switching among the 500 stocks by the committee in charge, and therefore few taxes to pay. Fine, but what might not be easily anticipated is that the lumped investment performs better, unmanaged than the vast majority of funds managed by experts. Large funds, at least, are forced to buy the

stocks of large corporations. Large corporations are inherently subject to immense scrutiny and publicity, so there remains little advantage to being on the inside or acting quickly on general economic news. What everybody knows, in Wall Street parlance, isn't worth knowing. Index funds made up of small companies, or foreign companies, may possibly not work out as well as those limited to large domestic companies. For a while, it was thought index funds would out-perform when everything in the marketplace was going up, but underperform when most things were going down in a bear market. Not so, they seem to work better any way you look at them. They are the standard for performance, not just a measure of the averages. These things are here to stay.

Well, maybe. Reservations remain, although they don't have much to do with investment choices. It may take decades to happen, but it's hard to escape the uneasy feeling that some manager, someday, will figure out a way to divert a hundredth of a percent, or so, into his own pocket. A hundredth of a percent of a trillion dollars is quite a temptation. Perhaps an even more serious concern is that voting control of the corporations in the portfolio inevitably gets diluted by widespread index investing. Management supervision by stockholders is potentially lessened. Whether this will lead to management abuses, a temptation for minority stockholder intrusions, or to the government over-regulation, taking any of these directions would likely create a new power balance in the economy.

Meanwhile, John Bogle, who died on January 16, 2019, is on his way to financier sainthood. He's certainly in a class with Anthony Drexel and Nicholas Biddle, already. And other icons are under review.

Originally published: Thursday, August 15, 2002; most-recently modified: Thursday, July 25, 2019

| Posted by: George Fisher | Jul 26, 2007 1:29 PM |

Newsweek

Washington Rolls Back Investor Protections

July 16, 2007 issue - Remember the "ownership society" that the administration swore to promote and protect? Remember the admiration lavished on the so-called shareholding class? You probably thought that meant you, because you invest in the stock market and own mutual funds. You would be wrong.

Even with the corporate frauds of the '90s barely out of the headlines and 21st-century frauds taking over (rampant insider trading; backdated stock options for executives), your government is rolling back some investor-protection rules. It's also urging the courts to side with corporate captains against their trusting shareholders. Key people in Congress, mindful of campaign contributions, stand on the captains' side.

I have three cases in point.

Block the SOX: The Sarbanes-Oxley law, SOX for short, passed in the wake of the WorldCom and Enron accounting frauds. Its critical Section 404 orders senior managers to test the effectiveness of their companies' financial controls, with oversight by independent auditors. You probably thought that was already part of a manager's job, but as it turns out, only the better companies cared. The rest have been whining about SOX ever since it passed.

The scrutiny forced by 404 has uncovered thousands of cases of bad financial reporting. A record 1,538 companies had to restate their earnings last year. Not surprisingly, their stocks lost a median of 6 percent in market value, reports the consulting firm Glass Lewis, compared with a gain of 15.7 percent in the Russell 3000 Index. But once they improve their financial tools, their businesses should improve as well.

This idea cuts no ice with a blinkered cadre of overpaid CEOs who get sore when restatements reduce earnings (and their option awards). They're sobbing that 404 costs too much. So, to wipe away their tears, the Securities and Exchange Commission plans to reduce the amount of testing required—creating "404 lite." (It's probably churlish to add that good accounting costs pennies compared with the size of CEO bonuses, but then CEOs never think they cost too much.)

Without question, SOX had a bad launch, says James Cox, a securities-law professor at Duke University. It cost more than expected and confused auditors and companies alike. But costs are falling and the benefits to investors are becoming clear. "The old, pre-404 system of preventing misleading statements failed," says Barbara Roper, head of investor protection for the Consumer Federation of America; 404 lite "turns back the clock."

A loftier argument claims that SOX is driving financial business away from the United States. Yet for new public offerings, foreign firms have increased their listings since SOX was passed. New York is indeed losing some ground to London, but for other reasons. Its new trading systems are faster than ours, its investment bankers charge half as much (are you listening, Goldman Sachs?) and it lets more crummy companies sell shares to the public. That's business we don't want.

Too many legislators oppose investors, too. Last month the House passed an amendment delaying 404 reporting for smaller companies—the very ones most likely to issue false financial statements. "That's a terrible precedent," says former SEC chairman Arthur Levitt. "It politicizes financial accounting and greatly increases the risk to investors."

Bash the class: When shareholders think they've been had, they bring a class-action suit. In the past, some suits overreached, leading Congress, in 1995, to pass a law making it harder to get into court. One big question remains: what do shareholders now have to prove before they can sue? In a Supreme Court case known as Tellabs, the SEC filed a fierce brief, essentially asking the court to kick out as many claims as possible. Last month the court rejected that view and adopted milder rules. Suing still isn't easy, despite those who say we're drowning in "frivolous" shareholder claims. The number of new lawsuits plunged to a record low of 110 last year, according to Cornerstone Research.

Free the team: Here's something you probably didn't know. Under a 1994 Supreme Court decision, shareholders cannot sue any corporate advisers—lawyers, accountants, investment banks—that "aid and abet" a fraud. A federal court recently stopped a lawsuit against Merrill Lynch, Deutsche Bank and Barclays, among others, for their alleged role in Enron's collapse.

Next term the court will hear a similar case known as StoneRidge. Details don't matter; here's the gist: Did third parties "merely" aid and abet in a communications company's fraudulent transactions, in which case they go free? Or were they primary players and hence liable? The SEC planned to enter the case on the investors' side, but both the White House and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson (himself an investment banker) said no.

If the court lets third-party players walk, "it gives underwriters, auditors and attorneys a license to kill," says Lynn Turner, a former chief accountant for the SEC. "They'd create a safe harbor for fraud." In a decade, we could see Enron redux.

| Posted by: George 4th | Jul 25, 2007 3:18 PM |

Here's an idea: 1975 was a watershed year in the financial industry and for none of the reasons usually given.

1975, of course, was the year of May Day when fixed commissions were no longer mandated by law (can you imagine legally-mandated theft?). Not that you'd notice if you were a client of Merrill Lynch or Janney Montgomery Scott.

How the ending of fixed commissions mattered was that it allowed Charles Schwab and Joe Ricketts to begin the discount brokerage industry, which has morphed into the Internet brokerage industry.

This has liberated the self-reliant investor from the teeth and talons of the ever-avaricious and wholly unprincipled broker.

Schwab essentially failed in is mission, and gave in to profit pressures, giving us such astonishing things as the purchase of US Trust, an institution devoted solely to the extraction of fees from its "high net worth" clients.

Joe Ricketts, however, has remained true to his ideals. Whether you choose to trade with AmeriTrade or Vanguard or Fidelity or Scottrade is a personal choice; but it was Joe who has given you that choice.

Bogle, also arose in the fateful year of 1975, to give the world the product it so desperately needed: a low-fee professionally-managed index fund. A product type that may soon be eclipsed by the ETF (if they aren't completely polluted by the major financial institutions first), but here again, it was a titan of the year 1975 that gave us our choices.

And our lives are richer for it.

(By the way, the origianl Merrill, of Merrill Lynch, was a principled customer's man; it was your friend Don Regan who turned MLPFS into a dumping ground for the likes of Henry Blogett.

There's another story for you to write about ... I'm sure both Merrill and Regan visited Philadelphia at one time or another.)

| Posted by: George Fisher 4th | Jun 2, 2006 7:43 PM |