5 Volumes

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Religion

New volume 2012-07-04 13:22:31 description

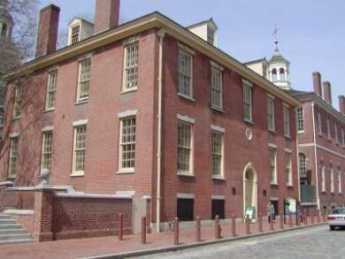

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

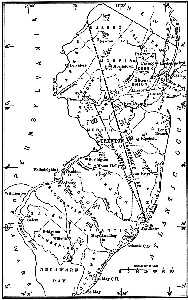

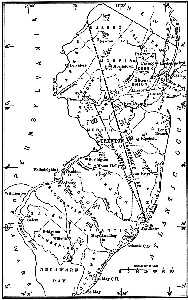

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Quakers: All Alike, All Different

Quaker doctrines emerge from the stories they tell about each other.

Most groups of Quakers look like other nondescript people. Flambouyant behavior is neither encouraged nor very common. And yet, Quaker discussions are often salted with anecdotes about members who once behaved in notable or highly individualistic ways. Sometimes, the adjective would be "outrageous". A few such stories follow.

The likely dynamic is that these epics stake out the implied borders of approved behavior. The religion has no fixed dogma; behavior no prescribed form. Prescribed behavior was once very notable, and without rejecting, Quakers are in retreat from it. To some extent it is necessary for such a group to assemble its pantheon, or its epic poem.

Quakers can give even those ancient ceremonial forms a unique twist of their own. Extremely reluctant to offend by criticising others, the group uses historic examples to praise, other history to deplore, still other stories as building blocks in a debate by indirection. As Samuel Johnson said, allusions are useful to "adorn a tale".

Rufus Jones, Quaker

|

| Rufus Jones |

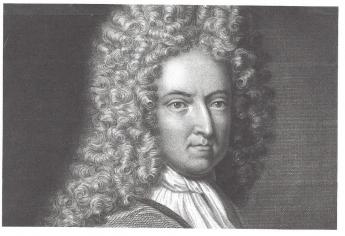

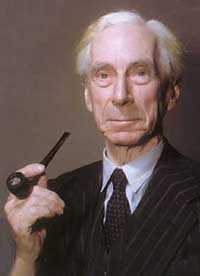

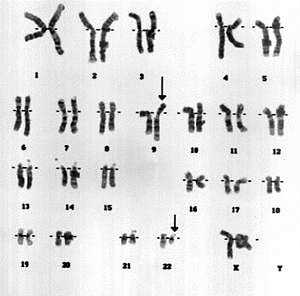

Rufus Jones (1863-1948) dominated the Quaker religion for two generations, causing a transformation which deserves to rank with that of George Fox, William Penn and Elias Hicks. A few elderly Quakers still remember him in person, mostly as an old gentleman who tended to lean back while he spoke, usually hooking his thumbs in the sides of his vest. He was a prodigious writer, having once made a promise to himself that he would read a new book every week, and write a new book, every year. He kept that up for thirty years.

|

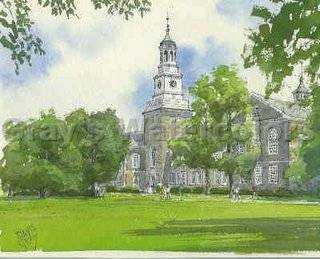

| Haverford College |

As a matter of fact, that understates his output. His published works were collected by Clarence Tobias at Haverford College, and run to 168 volumes, plus 8 boxes of pamphlets and articles. His family also donated his personal papers to the College, and they require 75 linear feet of shelf space.

His stated occupation would have been Professor at Haverford College, where his personal influence on the undergraduates was as profound as their influence was to be on the rest of the world. He is regarded as one of the founders of the American Friends Service Committee and the single greatest influence in reuniting the two divisions of Quakerism, although some of the formalities were not completed until after his death.

One other index of his remarkable energy was that he crossed the oceans more than two hundred times during his lifetime.

Perhaps the arrival of mass communication has made it possible to have equal impact with less effort. But Rufus Jones stands for the principle in life, that it never hurts to work just a little harder. If high school students are thinking of applying for admission to Haverford, they better understand what is going to be expected of them.

The Quaker Who Would Be King

|

| James A. Michener |

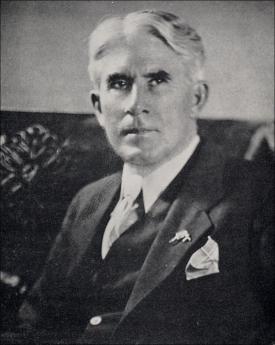

James Michener seemed headed for a recognizably Quaker life until show business rearranged his moorings. He was raised as a foundling by Mabel Michener of Doylestown, Pennsylvania, under circumstances that were very plain and poor. Many of his biographers have referred to his boyhood poverty as a defining influence, but they seem to have very little familiarity with Quakers. When the time came, this obviously very bright lad was offered a full scholarship to Swarthmore College, graduated summa cum laude, went on to teach at the George School and Hill Schools after fellowships at the British Museum. And then World War II came along, where he was almost but not exactly a conscientious objector; he enlisted in the Navy with the understanding he would not fight.

While in the Pacific, he had unusual opportunities to see the War from different angles, and wrote little short stories about it. Putting them together, he came back after the War with Tales of the South Pacific. Much of the emphasis was on racial relationships, the Naval Nurse who married a French planter, the upper-class Lieutenant (shades of the Hill School) who had a hopeless affair with a local native girl that was engineered by her ambitious mother, as central characters. Michener himself married a Japanese American, Mari Yoriko Sabusawa, whose family had been interned during the War. There are distinctly Quaker themes running through this story.

And then his book won a Pulitzer Prize, Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein made it into a Broadway musical hit, then a movie emerged. The simple Quaker life was then struck by the Tsunami of Broadway, Hollywood, show biz and enormous unexpected wealth. Just to imagine this simple Bucks County schoolteacher in the same room with Josh Logan the play doctor is to see the immovable object being tested by the irresistible force. Michener retreated into an impregnable fortress of work. He produced forty books, traveled incessantly, ran for Congress unsuccessfully, and was a member of many national commissions on a remarkably diverse range of topics. Although he lived his life in a simple Doylestown tract house, he gave away more than $100 million to various charities and educational institutions.

In his 91st year, he was on chronic renal dialysis. He finally told the doctors to turn it off.

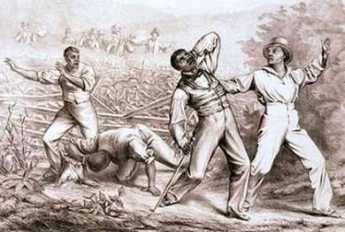

Slaveowning Quaker Steps Up To The Plate

|

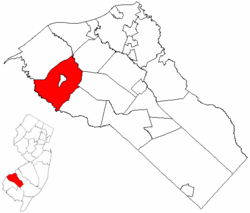

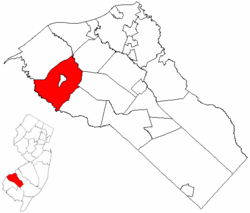

| County of Gloucester |

I, Joseph Nicholson of the Township of Woolwich and County of Gloucester, do hereby set free from bondage my Negro Tenor, aged about twenty-two years, and do, for myself, my Executors and Administrators, release unto the said Tenor, all my Right, and all claim whatsoever as to her person or to any Estate that may acquire, hereby declaring the said Tenor, absolutely free, without any interruption from me, or any person claiming under me.

In Witness whereof I have hereunto set my Hand and Seal this twenty-seventh day of the Twelfth Month, in the Year of our Lord One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy-nine. 1779.

. . . Joseph Nicholson (Seal)

. . Sealed and Delivered in the presence of Joseph Allen

Differences of Quaker Opinion

A reader of Philadelphia Reflections feels that a balanced appraisal of the slavery issue should include mention of the Quakers who were determined in their opposition to abolition. After all, it took eighty years for the original concern of the Germantown meeting to be fully adopted by the Philadelphia Yearly meeting as a formal minute under the prodding of John Woolman. Since the minute gives permission for particularly concerned Friends to go speak with slave-holding Quakers, it is clear that even some Philadelphia Quakers held slaves and were reluctant to release them.

| ||

| Abraham Redwood 1709-1788 |

Newport, Rhode Island, was an even more awkward case. In colonial times, and even today to some degree, individual Yearly meetings were cordial, but under no formal obligation to respond to each other's decisions. The English seaport of Bristol had developed a sugar trade with the West Indies, and a number of Bristol Quakers moved to Newport. Acquiring very large sugar plantations in the Indies, they shipped molasses to rum distilleries in Newport or else directly back to Bristol where a candy industry had been established. The next step was the shipment of rum and/or trading trinkets to Africa, to be exchanged for slaves, who were taken to the Caribbean and exchanged for a cargo of molasses. Molasses then went to Newport, in a triangular trade pattern which admittedly avoided bringing slave cargo to Rhode Island, but whose principal purpose was taking advantage of the prevailing Atlantic trade winds while maintaining a full cargo over the whole distance. The largest partnership in this trade belonged to four Newport Quakers, one of whom was Abraham Redwood.

Redwood owned 230 slaves in Antigua and was among the richest men in America at the time. It is rather troubling to learn that the average "turnover" of slaves on Antigua was seven years, and that slave rebellions were fairly common. Redwood donated five hundred pounds to the Newport Philosophical Society for the purchase of 1300 books, thereby establishing the Redwood Library in 1747, one of the oldest in the country, although the Library Company of Philadelphia was established in 1731. By almost any standard, Redwood was nevertheless a "weighty" Quaker. When he resolutely refused to sell his slaves, he was "read out" of the meeting.

Details of the discussions which were conducted are no longer readily available, but it is obvious that collision of these two equally stubborn viewpoints was particularly awkward when it led to the banishment of the main employer of the town, and its most important local benefactor. Furthermore, those who worked harmlessly in the rum industry in Newport, or the candy industry in England, were called upon to reflect deeply on the unfortunate slave dealings in which they were, perhaps unknowingly, implicated.

Somehow all of this was accomplished without a total rupture, because thirteen years later Abraham Redwood donated another five hundred pounds to the Quaker Meeting, for the establishment of a school.

Edward Hicks: Peaceable Kingdoms

|

| Peaceable Kingdoms |

Edward Hicks (1780-1849), the most important folk artist of American art, was born and lived all his life in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. About a hundred of his paintings survive, 62 of which are versions of "The Peaceable Kingdom". Recently, his Peaceable Kingdoms have been selling for more than $4 million apiece, and the other works at more than a million. As is so often the case, he was born in poverty and spent his life in poverty, so the financial benefits have all gone to middle-men.

Hicks had to overcome an additional handicap. Quakers disapproved of painting things up just for show, and they strongly disapproved of the vanity underlying the act of having a portrait painted of yourself. In fact, the early Quakers would not even permit their names to be placed on their tombstones.

Hicks was apprenticed into the wagon business and showed a talent for painting them. From that, entirely self-taught, he migrated into the business of painting business signs in an age of limited literacy. The Blue Anchor Tavern, the King of Prussia Inn, the Crossed Keys Tavern and the signs of various tradesmen were an essential part of conducting business. It is easy to see these tradesmen signs in the easel paintings of Hicks' later career, which reduce themselves to rearrangements of such individual sign paintings to make a coherent canvas.

If you have seen one "Peaceable Kingdom" you haven't seen them all, but you only need to see one to be able to recognize the others at sight. They generally form a group of wild animals and an occasional child in the right foreground, with a grouping of Quakers and Indians in the left background, taken from Benjamin West's famous portrayal of Penn signing the treaty of peace with the Delaware Indians. The scene is taken from Chapter 11 of Isaiah, in which the lion lies down with the lamb.

Hicks was not a successful farmer, and he had to overcome Quaker resistance even to sell religious paintings with a Quaker moral. No doubt the resistance was strengthened by the fact that his cousin Elias Hicks had split the Quaker church into two (Conservatives and Hicksites) in 1827, and Edward was himself a strong itinerant preacher. Although the plain message of the Peaceable Kingdom is reconciliation between the two branches of Quakerism, he probably encountered a fair amount of coolness among the Conservative opposition.

Hicks was neither an educated nor a sophisticated man. It is forgivable that he made such a strong Old Testament statement when he and his cousin represented a dissenting sect that was gravely doubtful about the wisdom of allowing your life to be ruled by biblical verses.

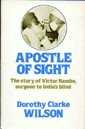

Victor Rambo, Indian Eye Surgeon

|

| Apostle of Sight |

There have been at least twelve documented generations of the Rambo family in Philadelphia. Historical justification can be found for the idea that this was the first family to settle within what are now the city limits. Victor Clough Rambo MD was an unpaid intern at the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1927; you will find his nameplate on the wall.

Victor early made up his mind that he was going to go where he could do the most good. Considerable thought led him to learn how to extract cataracts, and go to India to extract as many as he could. from time to time, he would return to America to visit family, and to give some speeches to raise money for his project.

The builders of our enormously costly hospital castles might give some thought to the fact that Victor did most of his surgery in tents. His system was to send out teams to the next two villages, whenever he was, with the news, "Bring in your blind people, the eye doctor is coming." When he then arrived, he set about operating on cataracts from dawn to dusk, in a country where the supply of cataracts was essentially unlimited. There was no time to operate on the comparatively minor visual disturbances so commonly treated in America today; he had to concentrate on people who were really blind, and in both eyes.

He wrote a book about his experiences, and perhaps there you could find data to calculate the number of people who were restored to a useful existence by his efforts. Surely, it was thousands. He just kept going at it, and when he died he was a very old man.

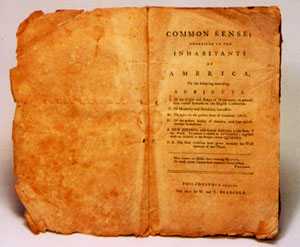

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

|

| Thomas Paine |

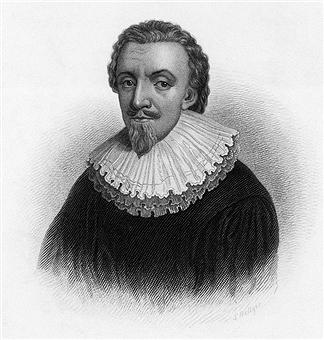

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was born of Quaker parents, which makes him a "birthright" Quaker. Children born into Quaker families are accustomed to the subtleties of speech and behavior of that religious sect, ultimately growing up to be the main nucleus of tradition. Knowing what they are getting into, however, they are more likely to rebel against it than others who, coming to the religion by choice rather than by birthright, are commonly described as "Convinced Friends."

These stereotypes may or may not explain some of Tom Paine's paradoxes. He certainly was not a pacifist, a quietest, or a plain person. He was an important historical figure; Walter A. McDougall, the famous University of Pennsylvania historian, feels the American colonists might have sputtered and complained about Royal rule for decades, except for Paine. The American Revolution happened when it happened because Tom Paine stirred up a storm.

|

| Common Sense |

According to the traditional way of telling his story, Tom Paine was a ne'er do well failure in London. He ran into Benjamin Franklin, who advised him to emigrate to America in 1775, and within a year his pamphlet called ""Common Sense"" had sold 150,000 copies (some even claim 500,000), galvanizing the public and the Continental Congress into action on July 4, 1776. George Washington read Paine's writings to his troops on the eve of the Battle of Trenton. After that, Paine got mixed up with the French Revolution, and apparently became a severe alcoholic, proclaiming atheism all the way. Although Thomas Jefferson remained friendly to the end, Benjamin Franklin essentially told him to go leave him alone, and Washington would cross the street to avoid him. According to the usual line, Tom Paine was a big-mouthed rabble-rouser and a drunk, who traveled the world looking to stir up revolutions.

However, that cannot possibly be a fair recounting of the whole story. Thomas Alva Edison, whose opinion certainly counts for something, regarded Tom Paine as one of the greatest American inventors, creating the first steel bridge, the first hollow candle, and the principle of central drought in heating. Paine early became a close friend of the Hicks family, the central figures in modern Quakerism; it seems a little unclear how much Tom Paine was reflecting the views of Elias Hicks, and how much Hick site Quakerism can be said to have originated in the thinking of Thomas Paine. Paine was very far from being an atheist. In fact, both he and Hicks believed so fervently in the universality of God that both of them scorned the rituals, paraphernalia, and transparent superstitions of -- religion.

Furthermore, Paine was able to reach the rationalists of The Enlightenment with arguments which cut to the heart of Royalist loyalties. America was too big and too remote to be ruled by a king, particularly one who abused his privileges behind a claim of divine right. William the Conqueror, for example, never denied he was a usurper. One way or another, every king must earn his throne. So, as for feudalism and hereditary aristocracy, what was King George doing with all those German mercenaries? After two centuries of democracy, most Americans are too far from feudalism to appreciate the legitimacy of military meritocracy. Whatever King George was up to, he didn't stand for empowerment of the best and the brightest Englishmen, who in fact might well be opposed to him. If you wanted to get to Virginia aristocrats, Boston sea captains, and Kentucky backwoodsmen, that was exactly the line to take in Common Sense.

Unfortunately, Citizen Tom Paine was a freethinker and couldn't be quiet about it in his later books. He didn't like the way the Old Testament Hebrews hungered for a king. He didn't like the way the New Testament sprinkled miracles on top of unassailable moral principles, and he particularly didn't like the claim that God got an unmarried girl pregnant. He antagonized almost every established religion by proclaiming that no one should make a living from religion. He wrote a book called Age of Reason proclaiming all these freethinking ideas, which struck Ben Franklin as such a stupid thing to do that he would not discuss it, beyond saying that even if he should succeed in convincing people to abandon religion, just imagine how much worse they would probably behave without it. George Washington, who hadn't a trace of intellectualism about him, more accurately portrayed the typical American revulsion at anyone who was so unprincipled as to say such unorthodox things in public. Jefferson distanced himself for political reasons rather than intellectual ones. Franklin thought Paine was a fool. Washington and the rest of the country thought he was a viper.

It would have to be conceded -- by anyone -- that Tom Paine was self-destructive, even sassing Robespierre while in a French prison. How is it such a loose cannon could get the American public off dead center and make the Continental Congress grasp the nettle of revolution, in less than a year? Let's go back to how he came to America in the first place. Franklin sent him.

Then he promptly got a job as editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, which Franklin had owned for thirty years. And then, in an era when the largest city in America had a population of twenty-five thousand, and the printing presses of the day were able to turn out three or four pages a minute, he sold 150,000 copies of the fifty-page "Common Sense." Who but Franklin, in private partnerships with sixty printers, could have possibly authorized, financed, and printed 150,000 copies of a colonial pamphlet? In order to find that much printing capacity in colonial America, a great deal of other printing had to lose its place in the queue.

Even today, a best-seller is defined as a book that sells 50,000 copies, and it generally takes three years to get it done. In the Eighteenth Century, for an unknown alcoholic to get off the boat and find a publisher for a best seller in a few weeks is hard even to imagine. Unless he had important help.

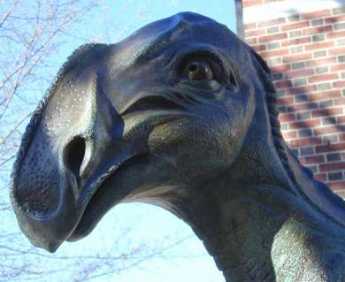

The Origins of Haddonfield

|

| Haddonfield's Dragon |

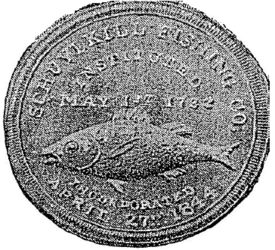

Haddonfield, New Jersey is named after Elizabeth Haddon, a teenaged Quaker girl who came alone to the proprietorship of West Jersey in 1701 to look after some land which her father had bought from William Penn. Geographically, the land was on what later came to be called the Cooper River, and it must have been a scary place among the woods and Indians for a single girl to set up housekeeping. It was related in the "Tales of a Wayside Inn" that Elizabeth proposed to another young Quaker named John Estaugh. Because no children resulted, she sent to her sister in Ireland to send one of her kids, a girl who proved unsatisfactory. So the kid was sent back, and Ebenezer Hopkins was sent in her place. Thus we have Hopkins pond, and lots of Hopkins in the neighborhood ever since. Eventually, the first dinosaur skeleton was discovered in the blue clay around Hopkins Pond, and now can be seen in the American Museum of Natural History, so you know for sure that Haddonfield is an old place. Eventually, the Kings Highway was built from Philadelphia to New York (actually Salem to Burlington at first) and it crosses the Cooper Creek near the old firehouse in Haddonfield, which claims to house the oldest volunteer fire company in America, but not without some argument about what was first, what is continuous, and therefore what is oldest. Haddonfield is, in short, where the Kings Highway crosses the Cooper, about seven miles east of City Hall in Philadelphia. The presence of the Delaware River in between makes a powerful difference since at exactly the same distance to the west of City Hall, is the crowded shopping and transportation hub at 69th and Market Street. Fifty years ago, Haddonfield was a little country town surrounded by pastures, and seventy years ago the streets were mostly unpaved. The isolation of Haddonfield was created by the river and was ended by the building of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1926. If you go way back to the Revolutionary War, the river created a military barrier, and many famous patriots like Marquis de Lafayette, Dolley Madison, Anthony Wayne and others met in comparative safety from the British in the Indian King Tavern. In a famous escapade, "Mad" Anthony Wayne drove some cattle from South Jersey around Haddonfield to the falls (rapids) at Trenton, and then over the back roads to Washington's encampment at Valley Forge. In retaliation, the British under Col John Simcoe rode into nearby Salem County and massacred the farmers at Hancock's Bridge who had provided the cattle. At another time, the Hessians were dispatched through Haddonfield to come upon the Delaware River fortifications at Red Bluff from the rear. Unfortunately for them, they encamped in Haddonfield overnight, and a runner took off through the woods to warn the rebels at Red Bank to turn their cannons around to ambush the attackers from the rear, who were therefore repulsed with great losses. These stories are told with great relish, but my mother in law found out some background truths. Seeking to join the Daughters of the Revolution in Haddonfield, she was privately told that the really preferable ladies' the club was the Colonial Dames. Quaker Haddonfield, you see, had been mostly Tory.

|

||

| Alfred Driscoll |

A local boy named Alfred Driscoll became Governor of New Jersey, but before he did that he was mayor of Haddonfield. He had gone to Princeton and wanted to know why Haddonfield couldn't look like Princeton. All it seemed to take was a few zoning ordinances, and today it might fairly be claimed that Haddonfield is at least as charming and beautiful as Princeton, maybe nicer. At the very least, it has less auto traffic. Al Driscoll went on to be CEO of a Fortune 500 pharmaceutical corporation, and everyone agrees he was the world's nicest guy. The other necessary component of beautiful colonial Haddonfield was a fierce old lady who was married to a lawyer. Any infraction of Al's zoning ordinances was met with an instant attack, legal, verbal, and physical. A street-side hot dog vendor set up his cart on Kings Highway at one time, and the lady came out and kicked it over. If you didn't think she meant business, there was always her lawyer husband to explain things to you. She probably carried things a little too far, and one resident was driven to the point of painting his whole house a brilliant lavender, just to demonstrate the concept of freedom. Now that she and her husband are gone, the town continues to be authentic and pretty, probably because dozens of other citizens stand quietly ready to employ some of her techniques if the need arises.

The Empire Visits Haddonfield, Briefly

|

| The Holy Roman Empire |

When William Penn extended an invitation to all religions to come to a place of religious freedom, he really meant it. All religions were welcomed and tolerated, but the English government was deathly fearful of French Catholics in Canada, and Spanish Catholics in Florida. The Stuart kings were Catholic, sort of, but the important issue was protecting colonial real estate more than protecting doctrinal purity. When they picked up immigrants at European ports, the ships had to make a stop in England, and any Catholics aboard were removed.

So one very large and important cultural group never had much influence in America, particularly in Philadelphia. The Holy Roman Empire, that large loyally powerful European Catholic group in central Europe and southern Germany, just never got here in any great number. Americans eventually came to hear there was an important culture of some sort centered in Vienna, full of fat jolly folks who danced waltzes, but these apparitions were seldom seen in person and were never much thought about. The steel mills of western Pennsylvania drew in large numbers of Hungarians, and they told of Vienna's rival capital in Budapest, but that rivalry was apparently like Penn and Cornell or maybe Harvard and Yale, and what difference. Occasional visitors from those regions would grow strangely hostile upon encountering this indifference to what seemed pretty important back home. But one must remember to be more polite when around guests, that's all.

It took the Second World War and its attendant cultural struggles to bring a real wave of immigrants to America from Vienna. And these people were neither poor nor uneducated. They quickly moved into the classical music world and assumed roles that were not only important but culturally more advanced than we were accustomed to. They entered the universities and quickly rose to the academic peaks. Many of them could out-sing, out-dance, out-conversationalize any little group of provincial folk who happened to encounter them. Their names began to appear in the social pages, marrying debutantes. To a large degree, this singular immigration movement came to an end when the Cold War did. And that's rather a pity; we could really use more people like that.

|

| Marie Therese, Austrian Queen of Louis XIV |

One unusual exile from that movement lived for a long time next to the Haddonfield Quaker Meeting, or at least just down a little wooded lane to the rear. The occupant of that house was John Waite, a Quaker who really looked like a Quaker.

Pennyslvania's Boundary: David Rittenhouse, Hero, Lord Baltimore, Villain

|

| David Rittenhouse |

In the Twenty-first Century, when we know how every American creek and river run, we can see it might have been simple to establish a boundary between the new royal grant to William Penn, and an earlier grant to Lord Baltimore by the then-reigning king's father, Charles I. Essentially: Penn got the Delaware Bay and a lot of wilderness to the west of it. George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had long held the top half of the Chesapeake Bay and a strip of wilderness to the west of that. Two bays, with two hazy strips of wilderness attached.

|

| George Calvert, Lord Baltimore |

At what is now Odessa, Delaware, those two bays are only five miles apart; compromise should have settled the issue quickly. Two English gentlemen could have sat down over a pipe and a brew, working something out. However, the English nation was then changing kings, beheading them over matters of religion. A Roman Catholic, Lord Baltimore probably thought an opportunity might emerge from the turmoil if he stalled until matters went his way, since next in line of succession was James, Duke of York, who was a Catholic. But matters fall into the hands of the lawyers when principals of an argument are unable to speak. As we noted elsewhere, in the legal system of the day the last word from the last king was what counted in law courts, accepting any uncertainty about future latest words from future latest kings in order to maintain immediate peace. To lawyers of the time, all this talk about justice, fairness, and geometry was idleness when the nation needed order and stability. So the Calvert family lawyers over the course of eighty years, introduced one specious proposition after another that turned other lawyers purple with rage. Penn's lawyer, Benjamin Chew, beat them at this game, and his mansions in Delaware and Germantown attest to the value attached to this achievement. In other circumstances, posturing might have led to war, as it did in similar disputes with Connecticut. Penn probably knew better, but it takes two to compromise.

|

| Mason-Dixon Line |

It must be admitted that honest confusion was possible. Sometimes, a line of latitude was a line in the sense Euclid intended: all length and no width. At other times, lawyers and kings were talking about "parallels" as if they were strips, roughly sixty miles wide. If a sixty-mile strip was intended, it was important for a grant to specify whether it extended to the southern edge of the strip, or to the northern edge. But in fact, the state of science in the Seventeenth Century contained uncertainty about both where the strips were, and how wide. And if the grant's language didn't even make it clear whether the parties were talking about strips or width-less lines, eighty years could be a comparatively short time for a court to decide the case. To be fair to Lord Baltimore, many people at the time didn't think these matters were capable of fair solution, so the traditional way of dealing with land disputes was either by force or by craftiness.

|

| David Rittenhouse Birth Place |

In William Penn the folks from Maryland were, unfortunately, dealing with a friend of the King, who had one of the most brilliant mathematicians in Western civilization as his adviser. David Rittenhouse may have been born in that little farmhouse you can still visit on the Wissahickon Creek, and made his living as a clockmaker, but his native talents in mathematics, astronomy surveying, and instrument construction were so deep and so varied that later biographers are reduced to describing him merely as a "scientist" and letting it go at that. If you want to sample his talents, spend an hour or two learning what a vernier is, and then see if you could apply that insight, as he did, to a compass. So, as it turned out, Rittenhouse was able to describe a twelve-mile circle around New Castle, Delaware, construct a tangent that divides the Delmarva's Peninsula in half, and match it up with an east-west line we now call the Mason Dixon Line. When they finally got around to laying these lines on the ground, Mason and Dixon cut a twenty-four-foot swath through the forest, using astronomical adjustments every night, and laying carved marker stones every fifth of a mile for hundreds of miles. The variation from the line devised by Rittenhouse was at most a fifth of a mile off the mark; the intersection with the north-south line between Maryland and Delaware was less successful. The survey by Mason and Dixon was not quite completed to the Ohio line because the Indians, curious at first, eventually became wild with suspicion at such behavior, particularly the part about going out and aiming cannons at the sky every night. It seems likely that George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, had no more confidence in this madness than the Indians did.

So, the next time you take the train from Philadelphia to Washington DC, reflect that strict reading of the words in the land grants did admit the possibility that your whole trip could either have been within the State of Maryland, or else in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, depending on whether lawyers, or scientists, had triumphed in this dispute. Since the Mason Dixon Line later divided not merely two states, but two violently opposed cultures, Rittenhouse must stand out in the history of one of those people who were so smart that most people couldn't understand how smart he was.

Marian B. Sanders, Quaker Activist, 87

|

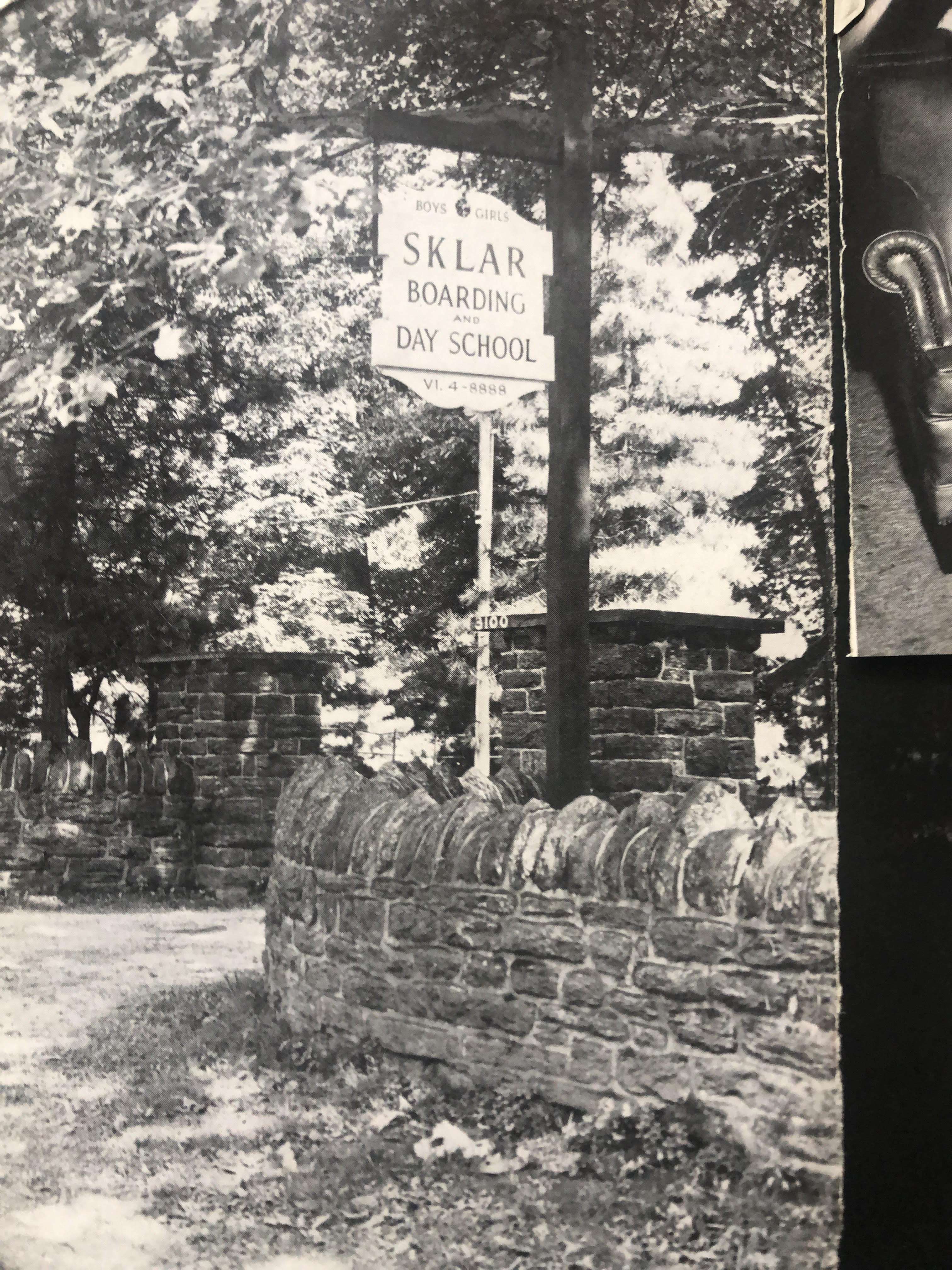

| Pre K Group |

Marian Binford Sanders, 87, of Mount Airy, a former principal of Lansdowne Friends School who devoted her life to Quaker service, died following gallbladder surgery April 23 at Chestnut Hill Hospital

Mrs. Sanders headed Lansdowne Friends from 1975 to 1981. During that time, her husband, Edwin, was a director of Pendle Hill, a Quaker study center in Wallingford, where the couple lived and where she taught courses. In the early 1980s, the couple lived at Cambridge Friends Meeting in Massachusetts, where they ministered and supervised the facilities.

|

| Chestnut Hill |

After retiring to Chestnut Hill in 1985, according to her son, David, Mrs. Sanders lectured on the poet William Blake at Pendle Hill, taught adult literacy, and cared for her husband, who had Alzheimer's disease, until his death in 1995.

She was dedicated to the concept of world citizenship, her son said and opened her home to students and travelers from around the world. In 1997, she received an award from Earlham college in Indiana honoring her and her late husband for the "55 years of the shared struggle for human justice, for an end to war ... and for broad service in the Society of Friends."

Mrs. Sanders grew up in Dayton, Ohio, and Butler, Pa. She earned a bachelor's degree from Earlham College and, in 1939, the year she married, a master's degree in English literature from Pennsylvania State University.

In 1940, her husband, a Quaker pacifist, was sentenced to federal prison for a year for refusing to register for the draft. After he was paroled, the couple taught at Pacific Ackworth Friends School in Temple City, Calif., which they helped found. For more than a year in the 1960s, they trained teachers in Kenya. Later, Mrs. Sanders taught English literature in Russia as an exchange teacher with the American Friends Service Committee.

In addition to her son, David, she is survived by sons Michael, Richard, John, Robert, and Erin; a daughter, Beth Sanders-Blevins; eight grandchildren; and four great-grandchildren.

A memorial service will be at 3 P.M. June 26 at Pendle Hill 338 Plush Mill Rd., Wallingford.

Memorial donations may be made to Lansdowne Friends School, 110 N. Lansdowne Ave. Lansdowne, Pa. 19050.

-Philadelphia Inquirer, May 15, 2004

John Bartram's Garden

|

| Bartram Gardens |

It's worth a visit to Bartram's Gardens, if only for the astonishment of finding a very large farm and stone Quaker farmhouse within a few blocks of our largest medical center, a stone's throw from the biggest oil refinery on the upper East Coast. And located on the edge of a neighborhood that is, well, past its prime. The trees on the farm are centuries old, so walking around the grounds imparts the feeling of being hundreds of miles from civilization when in fact you are only a hundred yards away from streets that are very urban, indeed. When you turn in certain directions, an occasional skyscraper peeps over treetops, and down the meadows, at the farm's dock on the leafy-banked Schuylkill, you can see oil storage tanks across the river, just a long shot with a 2-iron away. Look upward, to see the upper half of shining towers of Center City.

The farm property as it now stands dates back to 1728, but the site marks the earliest beginnings of the city, nearly a hundred years earlier. The river curves around this hill then snake on down to Delaware through flatlands which were originally swamps ("wetlands", as they say). The hill is as far downriver into malaria territory as the Indians were willing to go, so the Dutch traders had to sail upriver and dock there in order to take thirty or forty thousand fur pelts back to Holland each year. One thing or another has been dumped on the swamps for three hundred years, and the oil companies found it a cheap place to buy enough land for their refineries, close to four or five railroads near Bartram's place, and with access to the high seas. Right now, most of the oil comes from Nigeria, emptying two or so supertankers a week. There has to be enough storage capacity to take care of delays caused by bad weather on the Atlantic, and there has to be access to railroads and highways to carry the finished product away. The rest of a refinery is just thousands of miles of metal pipes, gleaming in the sun.

Sun Oil is trying to be a good neighbor, turning more and more of the area over to nature preserve, as chemical engineers have learned how to work in a smaller space with fewer employees. The banks of the lower Schuylkill are now mostly grown to shrubs and trees, concealing from boat travelers the rather extensive dumps of old auto tires and similar refuse. It's a placid winding trip, increasingly coming to resemble what the Dutch traders once encountered. Especially in May, when the Palomino or Empress trees are in purple bloom. It seems the Chinese packed their porcelains in dried Palomino seed pods, and the discards have grown up to quite a nice display. Logan Square is filled with such trees, quite artfully pruned and maintained; just imagine several miles of the river lined with them, and you can see why the Tourist Bureau is excited about the potential. If you have been to San Antonio you know the potential of an urban river ride, which in this case might go all the way up to the Art Museum. Given enough public response, you can envision two or three-day barge rides from New Castle, Delaware to Pennsbury, with side trips up past Bartram's to the Waterworks. Right now, trips are comparatively limited by the tides, with a few trips a year down from Bartram's to the refineries, and a few more up to the river to the Art Museum. They use floating docks, and permanent docks will need to be built.

|

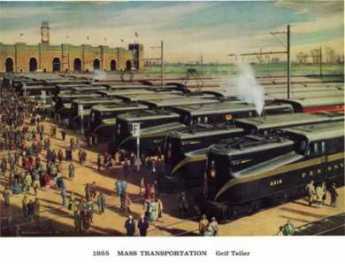

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

Originally, the crude oil came from upstate Pennsylvania, near Bradford, and was the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Baltimore and New York were also the beginnings of transcontinental railroads, but their freight cars came back empty. The upstate Pennsylvania oil gave the PRR a dominant edge by supplying cargo for two-way revenue.

When George Washington had to retreat from the Battle of Brandywine, the armies had to cross the wetlands, and the river, to get to Philadelphia. Washington got there first and burned the boats after his army got across. He knew, but the British probably did not fully realize, that the first place to ford the Schuylkill was at Norristown. When the British finally got that far, Washington was waiting for them, but a fall hurricane came along and soaked everybody's gunpowder before there could be much of a battle. Unfortunately, Mad Anthony Wayne was unprepared for a nighttime bayonet charge, and there was still quite a slaughter.

You can't wander around John Bartram's house and gardens without getting the impression of considerable wealth. Bartram was interested in botany, becoming the most eminent authority on plants of the Western hemisphere, a very close friend of Benjamin Franklin, and probably the main force behind the creation of the American Philosophical Society. But although Bartram was a hobbyist, he was a shrewd businessman, selling curiosity plants to Europeans, and commercially improved fruits and vegetables to local farmers. There are still some Bartrams around Philadelphia, with a strong Quaker air about them. Around 1850 the place was sold to a zillionaire railroad magnate named Eastwick, who fixed up the place in the high style he learned building the railroads of Russia for the Tsar. The mansion has been torn down, but the stone farmhouse, stone barn, stone sheds, stone outbuildings, stone everything -- endures, like many of the curiosity trees and bushes. Well worth a visit.

Slavery: If This be done well, What is done evil?

|

| Francis Daniel Pastorius |

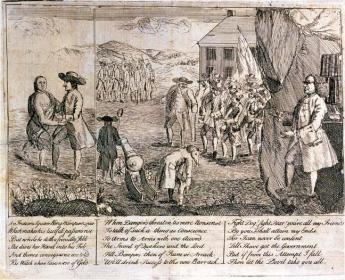

The Declaration of the German Friends of Germantown, Against Slavery, in 1688.

These are the reasons why we are against the traffic of men's body, as followeth:

Is there any that would be done or handled in this manner? viz.: to be sold or made a slave for all the time of his life? How fearful and faint-hearted are many at sea, when they see a stranger vessel, being afraid it should be a Turk, and they should be taken, and sold for slaves in Turkey. Now, what is this better done, than Turks do? Yea, rather it is worse for them, which say they are Christians; for we hear that the most part of such negers is brought hither against their will and consent and that many of them are stolen. Now though they are black, we cannot conceive there is more liberty to have them, slaves, as [than] it is to have other white ones. There is a saying , that we shall do to all men like as we will be done [to] ourselves; making no difference of what generation, descent, or color they are. And those who steal or rob men, and those who purchase them, are they not all alike? Here is liberty of conscience, which is right and reasonable; here ought to be likewise liberty of the body, except evil-doers, which is another case. But to bring men hither, or to rob, [steal] and sell them against their will, we stand against. In Europe, there are many oppressed for conscience sake; and here there are those oppressed which are of black color. And we who know others, separating wives from their husbands, and giving them to others: and some sell the children of these poor creatures to other men. Ah! do consider well this thing, you who do it, if you would be done in this manner--and if it is done according to Christianity! You surpass Holland and Germany in this thing. This makes an ill report in all those countries of Europe when they hear of [it,] that the Quakers do here handler men as they handle there the cattle. And for that reason, some have no mind or inclination to come hither. And who shall maintain this your cause, or plead for it? Truly, we cannot do so, except you shall inform us better hereof, viz,: That Christians have liberty to practice these things, Pray, what thing in the world can be done worse, towards us, than if men should rob or steal us away, and sell us for slaves to strange countries; separating husbands from their wives and children. Being now this is not done in the manner we would be done at, [by]; therefore, we contradict [oppose], and are against this traffic of men's body. And we who profess that it is not lawful to steal, must, likewise, avoid purchasing such things as are stolen, but rather help to stop this robbing and stealing, if possible. And such men ought to be delivered out of the hands of the robbers, and set free as in Europe. Then is Pennsylvania to have a good report, instead, it hath now a bad one, for this sake, in other countries. Especially whereas the Europeans are desirous to know in what manner the Quakers do rule in their province; and most of them do look upon us with an envious eye. But if this is done well, what shall we say is done evil?

If once these slaves ( which they say are so wicked and stubborn men,) should join themselves--fight for their freedom, and handle their masters and mistresses, as they did handle them before; will these masters and mistresses take the sword at hand and war against these poor slaves, like, as we are able to believe, some will not refuse to do? Or, have these poor negers not as much right to fight for their freedom, as you have to keep them slaves?

Now consider well this thing, if it is good or bad. And in case you find it to be good to handle these blacks in that manner, we desire and require you hereby lovingly, that may inform us herein, which at this time never was done, viz., that Christians have such a liberty to do so. To this end, we shall be satisfied on this point, and satisfy likewise our good friends and acquaintances in our native country, to whom it is a terror, or fearful thing, that men should be handled so in Pennsylvania.

This is from our meeting at Germantown, held ye 18th of the 2nd month, 1668, to be delivered to the monthly meeting at Richard Worrell's.

Garret Henderich

Derick op de Graeff

Francis Daniel Pastorius

Abram op de Graeff.***

At our Monthly meeting, at Dublin, ye 30th 2d mo., 1688, we have inspected ye matter, above mentioned, and considered of it, we find it so weighty that we think it not expedient for us to meddle with it here, but do rather commit it to ye consideration of ye quarterly meeting; ye tenor of it is related to ye truth.On behalf of ye monthly meeting,

Jo. Hart.

***

This above mentioned was read in our quarterly meeting, at Philadelphia, the 4th of ye 4th mo., '88, and was from thence recommended to the yearly meeting, and the above said Derick, and the other two mentioned therein, to present the same to ye above said meetings, it is a thing of too great a weight for this meeting to determine.Signed by order of ye meeting.

Anthony Morris

Inazo Nitobe, Quaker Samurai

|

| Inazo Nitobe |

The story of Inazo Nitobe (1862-1933) comes in two forms, one from the Philadelphia Quaker community, and the other from his home, in Japan. One day in Philadelphia, a well-known ninety-year-old Quaker gentleman, rumpled black suit, very soft voice -- and all -- happened to remark that his Aunt had married a Samurai. A real one? Topknot, kimono, long curved sword, and all? Yup. Uh-huh.

That would have been Inazo Nitobe, who met and married Moriko, nee Elizabeth Elkinton, while in college in Philadelphia. He became a Quaker, and when the couple returned to Japan, the Emperor then found himself confronted with a warrior nobleman who was a pacifist. You can next perceive the hand of his Quaker wife in the deferential diplomatic suggestion that there were vacancies for Japan at the League of Nations and the Peace Palace in the Hague. Perhaps, well perhaps, there could be service to his Emperor as well as his new religion in such an appointment for her new husband. Good thinking, let it be done. As far as Philadelphia is concerned, Ambassador Nitobe next appeared when Japan was invading Manchuria. The Emperor had sent Nitobe on a tour of America to explain things. At the meetinghouse then on Twelfth Street, Nitobe adopted the line that Japan was only bringing peace and order to a chaotic barbarian situation, actually saving many lives and restoring quiet. After a minute of silence, Rufus Jones rose from his seat on the "facing bench": He was having none of it. And that was that for Nitobe in Philadelphia.

The other side of this story quickly appears if you go to Japan and ask some acquaintances if they happen to have heard the name Inazo Nitobe. That turns out to be equivalent to asking some random American if he has ever heard of Abraham Lincoln. To begin with, Nitobe's picture appears on the 5000 Yen ($50) bills in everybody's pocket. He was the founder of the University of Tokyo, admission to which now is an automatic ticket to Japanese success. He wrote a number of books that are now required reading for any educated Japanese. A number of museums, hospitals, and gardens are named after him; one of them outside Vancouver, at the University of British Columbia.

Nitobe's father, Jujiro Nitobe, had been the best friend of the last Shogun, deposed by the return of the Emperor to effective control after Perry opened up Japan to Western ideas. The Shogun was beheaded, of course, and the tradition was that the victim could ask his best friend to do the job because he would do it swiftly. Jujiro was unable to bring himself to the task, refused, and his family was accordingly reduced to poverty. Subsequently, the Samurai were disbanded by the newly empowered Emperor, given a pension, and told to look for peaceful work. Inazo Nitobe was in law school when the Emperor's emissary came and said that Japan did not need culture, it had plenty of culture. The law students would please go to engineering school, where they could help Japan westernize.

Nitobe later wrote a perfectly charming memoir, called Reminiscences of Childhood in the Early days of Modern Japan , which dramatizes in just a few pages just how wide the cultural gap was. For example, Nitobe's father brought home a spoon one day, and this curious memento of how Westerners eat was placed in a position of high honor. One day, a neighbor ordered a suit of western clothes, and hobbled around it, saying he did not understand how Westerners are able to walk in such clothes. He had the pants on backward.

One of Nitobe's greatest achievements was to struggle with his appointment as Governor of Formosa (Taiwan). Japan acquired this primitive island in 1895, and Nitobe got the uncomfortable role of colonist in Japan's first experience with colonization. He sincerely believed it was possible for Japan to bring the benefits of Westernization to another Asian backwater, but just as the British found in their colonies, there was precious little gratitude for it. Although he was undoubtedly acting dutifully on the Emperor's orders when he later came to Twelfth Street Meeting, he surely knew -- perhaps even better than Rufus Jones -- that there was something to be said on both sides, no matter how conflicted you had to be if you were in a position of responsibility. This most revered man in his whole nation almost surely saw he had been a complete failure in Philadelphia.

Henry Cadbury Dresses Up for the King

|

| Henry Cadbury |

There are a few old Quaker Clothes in the attics of their descendants, and on suitable occasions, an old broad-brimmed hat or two will appear at a Quaker gathering, for amusement. Quakers gave up the old style of "plain dress" when it became generally agreed that such eccentric dress was not plain at all but rather drew attention to itself. On the other hand, there is a distinctly unfashionable quality to almost everything Quakers do wear. When silk and nylon stockings were fashionable for women, Quaker women often wore black stockings. When it became the style for women to sport black stockings, Quaker women usually wore flesh-colored nylons. Among men, thin metal-trimmed spectacles displayed the same counter-fashionable tendency. Nowadays, these little quirks are often public signals among strangers, a way of wig-wagging "I notice you are a Quaker, so am I." And of course, unfashionable clothes are cheaper, and that's always a good thing.

And so it happened in 1947 that the Quakers were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, with information passed along that white tie and tails were the expected form of dress at the ceremony. Henry Cadbury was selected to receive the award on behalf of the American Friends Service Committee, and you can be sure Henry Cadbury didn't own a set of tails. Henry was also very certain he wasn't going to go out and buy a set, just for a single wearing.

The AFSC collects used clothing, to distribute to the poor. Henry inquired whether there might be a set of white tie and tails to be found in the used-clothing bin, and luckily there was. It had been collected on behalf of the Budapest Symphony Orchestra when that impoverished but distinguished group of musicians was invited to give a concert in London. One of the monkey suits more, or less, fit Henry.

So, after investing in dry cleaning and pressing, Henry packed it up and went off to Oslo, to meet the King.

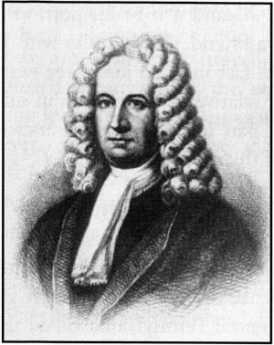

Germantown Before 1730

|

| Rev. Wilhelm Rittenhausen |

The flood of German immigrants into Philadelphia after 1730 soon made Germantown, into a German town, indeed. From 1683 to 1730, however, Germantown had been settled by Dutch and Swiss Mennonites, attracted by the many similarities between themselves and the Quakers of England. They spoke German dialects to preserve their separateness from the English-speaking majority but belonged to distinctive cultures which were in fact more than a little anti-German. This curiosity becomes easier to understand in the context of the mountainous Swiss burned at the stake by their Bavarian neighbors, Rhinelanders who sheltered them from various warring neighbors, and Dutchmen at the mouth of the Rhine, all adherents of Menno Simon the Dutch Anabaptist, but harboring many differences of viewpoint about the tribes which surrounded them.

Anabaptism is the doctrine that a child is too young to understand religion, and must be re-baptized later when his testimony will be more binding. In retrospect, it seems strange that such a view could provoke such antagonism. These earlier refugees were often townspeople of the artisan and business class, rapidly establishing Germantown as the intellectual capital of Germans throughout America. This eminence was promoted further through the establishment by the Rittenhouse family (Rittinghuysen, Rittenhausen) of the first paper mill in America. Rittenhousetown is a little collection of houses still readily seen on the north side of the Wissahickon Creek, with Wissahickon Avenue nestled behind it. The road which now runs along the Wissahickon is so narrow and windy, and the traffic goes at such dangerous pace, that many people who travel it daily have never paid adequate attention to the Rittenhousetown museum area. It's well worth a visit, although the entrance is hard to find (try going west on Wissahickon Avenue then turning around, a little beyond the entrance).

Even today, printing businesses usually locate near their source of paper to reduce transportation costs. North Carolina is the present pulp paper source, several decades ago it was Michigan. In the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries, paper came from Germantown, so the printing and publishing industry centered here, too. When Pastorius was describing the new German settlement to prospective immigrants, he said, "Es ist nur Wald" -- it's just a forest. A forest near a source of abundant water. Some of the surly remarks of Benjamin Franklin about German immigrants may have grown out of his competition with Christoper Sower (Saur), the largest printer in America, and located of course in Germantown.

Francis Daniel Pastorius was sort of a local European flack for William Penn. He assembled in the Rhineland town of Krefeld a group of Dutch Quaker investors called the Frankford Company. When the time came for the group to emigrate, however, Pastorius alone actually crossed the ocean; so he was obliged to return the 16,000 acres of Germantown, Roxborough and Chestnut Hill he had been ceded. Another group, half Dutch and half Swiss, came from Krisheim (Cresheim) to a 6000-acre land grant in the high ground between the Schuylkill and the Delaware. The time was 1683. The heavily Swiss origins of these original settlers give an additional flavor to the term "Pennsylvania Dutch".

Where the Wissahickon crosses Germantown Avenue, a group of Rosicrucian hermits created a settlement, one of considerable musical and literary attainment. The leader was John Kelpius, and upon his death the group broke up, many going further west to the cloister at Ephrata. From 1683 to 1730 Germantown was small wooden houses and muddy roads, but there was nevertheless to be found the center of Germanic intellectual and religious ferment. Several protestant denominations have their founding mother church on Germantown Avenue, Sower spread bibles and prayer books up and down the Appalachians, and even the hermits put a defining Germantown stamp on the sects which were to arrive after 1730. The hermits apparently invented the hex signs, which were carried westward by a later, more agrarian, German peasant immigration, passing through on the way to the deep topsoil of Lancaster County.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

Contemporary Germantown

The Strittmatter Award is the most prestigious honor given by the Philadelphia County Medical Society and is named after a famous and revered physician who was President of the society in the 1920s. There is usually a dinner given before the award ceremony, where all of the prior recipients of the award show up to welcome to this year's new honoree.

|

| Bockus |

This is the reason that Henry Bockus and Jonathan Rhoads were sitting at the same table, some time around 1975. Bockus had written a famous multi-volume textbook of gastroenterology which had an unusually long run because it was published before World War II and had no competition during the War or for several years afterward; to a generation of physicians, his name was almost synonymous with gastroenterology. In addition, he was a gifted speaker, quite capable of keeping an audience on the edge of their chairs, even though after the speech it might be difficult to recall just what he had said. On this particular evening, the silver-haired oracle might have been just a wee bit tipsy.

Jonathan Rhoads had likewise written a textbook, about Surgery, and had similarly been president of dozens of national and international surgical societies. He devised a technique of feeding patients intravenously which has been the standard for many decades, and in his spare time had been a member of the Philadelphia School Board, a dominant trustee of Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, and the provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Not the medical school, the whole university, and is said to have been one of the best provosts of the University of Pennsylvania ever had. When he was President of the American Philosophical Society, he engineered its endowment from three million to ten times that amount. For all these accomplishments, he was a man of few words, unusual courtesy -- and a huge appetite in keeping with his rather huge farmboy physical stature. On the evening in question, he was busy shoveling food.

"Hey, Rhoads, wherrseriland?". Jonathan's eyes rose to the questioner, but he kept his head bowed over his plate.

"HeyRhoads, Westland?" The surgeon put down his fork and asked, "What are you talking about?"

"Well," said Bockus, "Every famous surgeon I know, has a house on an island, somewhere. Where's your island?

"Germantown," replied Rhoads, and returned attention to his dinner.

John Bogle, A Prophet In Our Valley

|

| John C Bogle |

Those who never met a living legend would have found in John C. Bogle a good place to begin, 80-plus years old, lively and very charming. The Vanguard Investment Company, which he founded, provides him a little think tank office, out of which have come several books and many articles (somebody else is running the company, now.) The drift of most of what he writes and most of his testimony to Congress, or at awards ceremonies, is that mutual funds charge too much. When the press decides to feature him, the spectacular theme is emphasized that in 1996 this current squash and tennis player was just about dead, and had a transplant of someone else's heart to keep him going. A populist graduate of Pre-Vietnam Princeton, and also the embodiment of a medical miracle, now, those things are newsworthy.

Future students of finance, however, will regard those things as minor footnotes. Bogle's real achievement was the invention of the index fund. Indexing had two purposes and probably stumbled onto a third. It combined diversification, low administrative costs, and outstanding investment performance in a single security. There will be foot-dragging in the boutiques and bucket shops, but this invention is well on its way to converting investment management from an inefficient luxury of the rich into an affordable efficient commodity for everybody. You will know that a fundamental has been established on the day when the U.S. Government starts buying index funds, or at least when it permits them to help finance Medicare or Social Security. Such invested funds of a government qualify for the term Sovereign-wealth funds; in fact, since major problems can be imagined if governments start to vote common shares, Heaven helps us if they don't stick to index funds. The investment community already knows that something basic has arrived, by their own standards. The original index fund will soon have a trillion dollars invested in it. Just do the math on what you would be paid if you realized a fifth of one percent, year after year, on managing a trillion. And then reflect on the impact on transactional costs generally, when many eminent firms still charge five times that much. To make barrels of money and still be a hero for making your product remarkably cheap -- now, there's a Philadelphia dream.

A technical explanation. Five hundred stocks as one lump are cheaper to buy and sell as a "program trade", and perform more smoothly, than any of them individually, because the ups balance out the downs. Transaction costs are less, because there is hardly any switching among the 500 stocks by the committee in charge, and therefore few taxes to pay. Fine, but what might not be easily anticipated is that the lumped investment performs better, unmanaged than the vast majority of funds managed by experts. Large funds, at least, are forced to buy the

stocks of large corporations. Large corporations are inherently subject to immense scrutiny and publicity, so there remains little advantage to being on the inside or acting quickly on general economic news. What everybody knows, in Wall Street parlance, isn't worth knowing. Index funds made up of small companies, or foreign companies, may possibly not work out as well as those limited to large domestic companies. For a while, it was thought index funds would out-perform when everything in the marketplace was going up, but underperform when most things were going down in a bear market. Not so, they seem to work better any way you look at them. They are the standard for performance, not just a measure of the averages. These things are here to stay.

Well, maybe. Reservations remain, although they don't have much to do with investment choices. It may take decades to happen, but it's hard to escape the uneasy feeling that some manager, someday, will figure out a way to divert a hundredth of a percent, or so, into his own pocket. A hundredth of a percent of a trillion dollars is quite a temptation. Perhaps an even more serious concern is that voting control of the corporations in the portfolio inevitably gets diluted by widespread index investing. Management supervision by stockholders is potentially lessened. Whether this will lead to management abuses, a temptation for minority stockholder intrusions, or to the government over-regulation, taking any of these directions would likely create a new power balance in the economy.

Meanwhile, John Bogle, who died on January 16, 2019, is on his way to financier sainthood. He's certainly in a class with Anthony Drexel and Nicholas Biddle, already. And other icons are under review.

Lin

Lindley B. Reagan, M.D.

July 16, 1918 -- September 10, 1995

|

| Lindley B. Reagan, M.D |

The first and oldest hospital in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce Streets, always had a strong Quaker flavor but a unique medical tradition as well. Since it was the only American hospital for decades, later becoming the home hospital of the first medical school in the country, it impressed its ideals and traditions on the whole of American medicine. However, it imposed so many difficult demands on its trainees that a century or more of an evolving profession simply moved away from copying it. It was, in 1960, the last hospital in the country to begin paying its resident physicians anything at all, one of the last privately controlled American hospital to adopt a billing and accounting department, and one of the last if not the last to regard a handful of private beds as merely a convenience for the patients of the staff physicians. In 1970 its method of maintaining inventory was to notice that the supplies on the shelf were running low, and ordering some more. It was founded in Benjamin Franklin's words, for the "sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay," and could only survive into the late 20th Century through private donations and the freely contributed services of the doctors, student nurses and administration. No amount of money could induce people to work as hard as they worked. You might say this was the only aspect of Medieval monasteries which Philadelphia Quakers thought worthy of imitating.

Somewhere in this set of ideas was the treasured concept of a rotating internship, preferably two years long, prior to entering specialty training through a residency. In 19th Century Vienna, it was a matter of rule that an intern was just that, physically confined within the walls for the term of service, and a resident was just that, someone who lived on the campus. The Pennsylvania Hospital had no such rule, but since it paid the doctors nothing for five or six years of eighty-hour weeks, their poverty forced them to satisfy the Viennese rules by default. Entertainment was bridge or poker in the intern quarters, conversational chit-chat was a description of bizarre cases or peculiar patients, a weekend "off-call" was a good time to catch up on correspondence. There were student nurses around, of course, but the matron was a pretty no-nonsense chaperon. Every class of interns contained one or two millionaires by inheritance, but peer pressure made them nearly indistinguishable in the daily routines. Aristocrats' main value to the resident physician community was their access to the ruling families in the city, and hence to the governance of the hospital, in case governance should occasionally abuse the vulnerability of the trainees.

I find in retirement that most of my colleagues are now willing to tell stories of the "old days" which they were unwilling to tell at the time. Over several glasses of the finest single-malt in a walnut-paneled club, one such story recently surfaced. It concerned Lin.

Lin was a member of an old Quaker family, surprising everybody during the Second World War by volunteering as a junior physician in the Navy. He was assigned to a marine regiment in the Pacific Theater and went through some of the most murderous fightings on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. Our grapevine reported that the enlisted Marines in his outfit absolutely worshipped him, and I easily believe there was a lot of quiet heroism behind that gossip. He told me he had decided to become an internist while in the Pacific, but somehow only a surgical residency was available when the War was over, so he took it. He was probably the best internist on the staff, and it showed in his conduct of surgery, where it sometimes matters more what you decide to cut than what you cut. He always looked exhausted, but never hesitated to drive himself another hour when the situation demanded it. One day, he had to excuse himself from an operation, an almost unheard-of event, and testing his own urine, found it loaded with sugar. So, the soft-spoken Quaker internist who was primarily doing surgery had to add the burden of insulin injections to his load. If he ever complained about that or any other thing, no one could remember hearing it.

At about the third glass of single malt, the story came out. My old friend, like the rest of us, had to spend a year as a surgical intern during the two-year rotating internship; he hated surgery and didn't mind telling the world. At the moment in question, he was the assistant at some neck surgery, with Lin performing the actual surgery. He was told to take a long pair of scissors and cut off the excess strands of sutures after Lin tied the knots; that was known as trimming the ligatures. They were working deep in the crevices of the patient's neck. Lin held up the loose ends of the knot and ordered, "Cut". My friend inserted the long scissors into the hole and snipped -- accidentally cutting right through the jugular vein.

As would be expected, a fountain of blood came up out of the hole, and Lin stopped it by putting his thumb on the cut ends of the vein. "Well," said Lin, "I guess we'll have to fix that." And did.

With tears in his eyes, my octogenarian friend cried out to the startled clubroom. "God bless you. God bless you, Lin."

Perhaps the point isn't clear to those who didn't go through the process, so let's be more explicit. Both my friend and I worshipped Lin, as a person, a teacher, and a surgeon. He was the perfect agent for his patients, without the tiniest trace of conflict of interest, income-maximizing or whatnot. He was as technically skillful as it is useful to be, but he was the thinking man's surgeon as well as the utterly faithful servant of the best interests of the humblest patient. He was, in the opinion of his closest professional associates, the best surgeon in the world. In need of surgery ourselves, all of us would have flown the Atlantic to have him operate on us. For reasons of his own, he was to spend the forty years of his professional life in a small country town with a small hospital, scarcely a famous surgeon but a beloved one to his community. Over the past sixty years, I have had a number of opportunities to know many surgeons who would be in contention for the title of the best surgeon in the world. Some have written books, some have struggled successfully upward through vicious competition, some of them would be called "Rainmakers" if the research world followed the pattern of lawyers and architects. One or two have won Nobel Prizes for surgical innovations, but that's different from being the best surgeon around. The best surgeon in the world was Lin, faithfully plying his trade in a little town that could not possibly know how lucky they were.

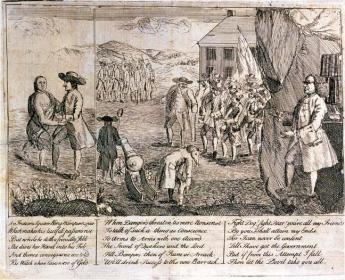

Pembertons

|

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

Logan, Franklin, Library

|

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |

Jim Greene is the librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia, and one of the leading authorities on James Logan, the Penn Proprietors' chief agent in the Colony. Since Logan and Ben Franklin were the main forces in starting the oldest library in America, knowing all about Logan almost comes with the job of Librarian. We are greatly indebted to a speech the other night, given by Greene at the Franklin Inn, a hundred yards away from the Library.

|

| James Logan |