1 Volumes

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Philadelphia People

New topic 2017-02-06 20:33:59 description

John Bogle, A Prophet In Our Valley

|

| John C Bogle |

Those who never met a living legend would have found in John C. Bogle a good place to begin, 80-plus years old, lively and very charming. The Vanguard Investment Company, which he founded, provides him a little think tank office, out of which have come several books and many articles (somebody else is running the company, now.) The drift of most of what he writes and most of his testimony to Congress, or at awards ceremonies, is that mutual funds charge too much. When the press decides to feature him, the spectacular theme is emphasized that in 1996 this current squash and tennis player was just about dead, and had a transplant of someone else's heart to keep him going. A populist graduate of Pre-Vietnam Princeton, and also the embodiment of a medical miracle, now, those things are newsworthy.

Future students of finance, however, will regard those things as minor footnotes. Bogle's real achievement was the invention of the index fund. Indexing had two purposes and probably stumbled onto a third. It combined diversification, low administrative costs, and outstanding investment performance in a single security. There will be foot-dragging in the boutiques and bucket shops, but this invention is well on its way to converting investment management from an inefficient luxury of the rich into an affordable efficient commodity for everybody. You will know that a fundamental has been established on the day when the U.S. Government starts buying index funds, or at least when it permits them to help finance Medicare or Social Security. Such invested funds of a government qualify for the term Sovereign-wealth funds; in fact, since major problems can be imagined if governments start to vote common shares, Heaven helps us if they don't stick to index funds. The investment community already knows that something basic has arrived, by their own standards. The original index fund will soon have a trillion dollars invested in it. Just do the math on what you would be paid if you realized a fifth of one percent, year after year, on managing a trillion. And then reflect on the impact on transactional costs generally, when many eminent firms still charge five times that much. To make barrels of money and still be a hero for making your product remarkably cheap -- now, there's a Philadelphia dream.

A technical explanation. Five hundred stocks as one lump are cheaper to buy and sell as a "program trade", and perform more smoothly, than any of them individually, because the ups balance out the downs. Transaction costs are less, because there is hardly any switching among the 500 stocks by the committee in charge, and therefore few taxes to pay. Fine, but what might not be easily anticipated is that the lumped investment performs better, unmanaged than the vast majority of funds managed by experts. Large funds, at least, are forced to buy the

stocks of large corporations. Large corporations are inherently subject to immense scrutiny and publicity, so there remains little advantage to being on the inside or acting quickly on general economic news. What everybody knows, in Wall Street parlance, isn't worth knowing. Index funds made up of small companies, or foreign companies, may possibly not work out as well as those limited to large domestic companies. For a while, it was thought index funds would out-perform when everything in the marketplace was going up, but underperform when most things were going down in a bear market. Not so, they seem to work better any way you look at them. They are the standard for performance, not just a measure of the averages. These things are here to stay.

Well, maybe. Reservations remain, although they don't have much to do with investment choices. It may take decades to happen, but it's hard to escape the uneasy feeling that some manager, someday, will figure out a way to divert a hundredth of a percent, or so, into his own pocket. A hundredth of a percent of a trillion dollars is quite a temptation. Perhaps an even more serious concern is that voting control of the corporations in the portfolio inevitably gets diluted by widespread index investing. Management supervision by stockholders is potentially lessened. Whether this will lead to management abuses, a temptation for minority stockholder intrusions, or to the government over-regulation, taking any of these directions would likely create a new power balance in the economy.

Meanwhile, John Bogle, who died on January 16, 2019, is on his way to financier sainthood. He's certainly in a class with Anthony Drexel and Nicholas Biddle, already. And other icons are under review.

A Toast to Doctor Franklin

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Benjamin Franklin's formal education ended with the second grade, but he must now be acknowledged as one of the most erudite men of his age. He liked to be called Doctor Franklin, although he had no medical training. He was given an honorary degree of Master of Arts by Harvard and Yale, and honorary doctorates by St.Andrew and Oxford. It is unfortunate that in our day, an honorary degree has degraded to something colleges give to wealthy alumni, or visiting politicians, or some celebrity who will fill the seats at an otherwise boring commencement ceremony. In Franklin's day, an honorary degree was awarded for significant achievements. It was far more prestigious than an earned degree, which merely signified adequate preparation for potential later achievement.

And then, there is another subtlety of academic jostling. Physicians generally want to be addressed as Doctor, as a way of emphasizing that theirs is the older of the two learned professions. A good many PhDs respond by rejecting the title, as a way of sniffing they have no need to be impostors. In England, moreover, surgeons deliberately renounce the title, for reasons they will have to explain themselves. Franklin turned this credential foolishness on its head. Having gone no further than the second grade, he invented bifocal glasses. He invented the rubber catheter. He founded the first hospital in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and he donated the books for it to create the first medical library in the country. Until the Civil war, that particular library was the largest medical library in America. Franklin wrote extensively about gout, the causes of lead poisoning and the origins of the common cold. By inventing bar soap, it could be claimed he saved more lives from the infectious disease than antibiotics have. It would be hard to find anyone with either an M.D. degree or a Ph.D. degree, then or now, who displayed such impressive scientific medical credentials, without earning -- any credentials at all.

Franklin: Upstart Hero of King George's War (1747)

In 1747, Benjamin Franklin had a life-transforming experience, acting quite unlike his character before, or later. At that time, Old Europe was engaged in some distant tribal skirmishing which has come to be known as King George's War. King George II, that is, under whose rule Franklin in 1751 inscribed on the cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital that Pennsylvania was flourishing, "for he sought the happiness of his people."

|

|

The cornerstone of the Pennsylvania Hospital inscribed by Franklin. |

Those distant commotions suddenly developed a harsh reality for the little pacifist sanctuaries on the Delaware River, when French and Spanish privateers suddenly raided and destroyed settlements on Delaware Bay. The Quaker Assemblies and their absentee Proprietor merely dithered and huddled in the face of what impended as a totally unexpected threat of annihilation of the pacifist colonies. It probably only seemed natural for the owner of the largest newspaper in the colony to publish a pamphlet called "Plain Truth," urging the inhabitants to rally to their own defense, and pressure their government to lead them. The Quaker leaders were in fact unable to readjust a lifetime of pacifist belief in a few days of an emergency, and the English Proprietor, then Thomas Penn, was far too remote to take active charge of matters. So, Franklin gave speeches, also an unfamiliar role for him, and finally brought out a detailed proposal for the creation of a Pennsylvania Militia. Ten thousand volunteers promptly signed up, elected Franklin as their Colonel; but he declined, and served as a common soldier.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in 1767. |

Against naval attack, the Militia needed cannon, which did not exist in the colony. So Franklin organized a lottery, raised three thousand pounds, and tried to buy cannon from Governor Clinton of New York. New York declined to sell, and so Franklin led a delegation to New York to negotiate. The negotiations largely consisted of getting Governor Clinton drunk and convivial, but they were successful, the artillery was shipped off to Philadelphia. Although they were undoubtedly grateful to Franklin for saving the day, this entirely extra-legal recruitment of an army badly rattled the Quakers and their Proprietor, since it demonstrated the ineffectiveness of their governance at a time of obvious crisis, and might ultimately have led to their overthrow. Franklin's heroic behavior seemed so threatening to Thomas Penn that he described him as "a dangerous man," acting like "the Tribune of the People."

When the underlying commotion in Old Europe subsided, the threat to the colonies disappeared, so the Militia disbanded in a year. Franklin seemed to be just as uncomfortable with his unaccustomed role as the governing leaders were, and he hardly ever mentioned it again. However, this is the sort of reflex leadership which makes political careers, and it surely influenced his decision to retire from business in 1748, run for election to the Assembly, and live like a gentleman. Seven years later, during the French and Indian War, he had become the chosen leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly, had much longer to think through what he was doing, and had learned how to organize a war. By that time, as the saying goes, he knew who he was. He was a man whose silent memories could flashback to that time when a bald fat printer stepped out of the crowd, saying "Follow me," and ten thousand men with muskets did so.

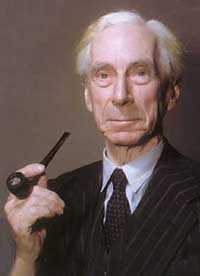

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Marty Feldstein Forecasts the Future

|

| Martin Feldstein |

With increasing frequency, the op-ed pages of the Wall Street Journal are opened to important people or important ideas. On April 28, 2006,Professor Martin Feldstein of Harvard wrote an article which purports to show how it is possible to have the American currency fixed for Americans but float for foreigners. After reading it twice, I conclude he is saying something rather different, and softening some startling announcements with circumlocution. It is my view that he says the following:

Inflation is not a worry; targeting 2% inflation with adjustments in short-term interest rates will take care of it.

International trade deficits need not be a worry, either, if only the Treasury Department (Could he mean nice old John Snow?) would allow the dollar to float on the international market. Not pure floating, of course, because it is a dirty world out there. The necessary dirty floating might hurt at first, especially American global businesses, but the sooner the boil is lanced, the better we will be. American exports of capital goods, consumer goods, and industrial supplies will especially benefit. Those who worry that trade deficits will weaken the dollar have got it backward a weaker dollar will correct the trade deficit. Yes, some people will be hurt by this.

In particular, high-wage countries like Europe, Canada, and Japan will be hurt, possibly severely hurt.

You will be able to tell that this plan has been set in motion when you see an international conference called among low-wage countries. The main purpose will be to reassure them that the U.S. Treasury won't punish them for strengthening their currency.

You will be able to tell this proposal has been rejected, probably for political reasons, if nothing soon happens to soften housing prices. And the word soon is emphasized. Because if they don't soften, they will break.

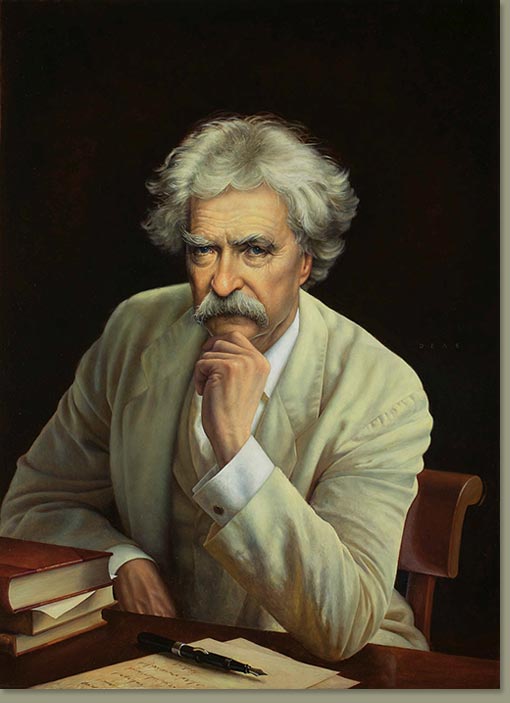

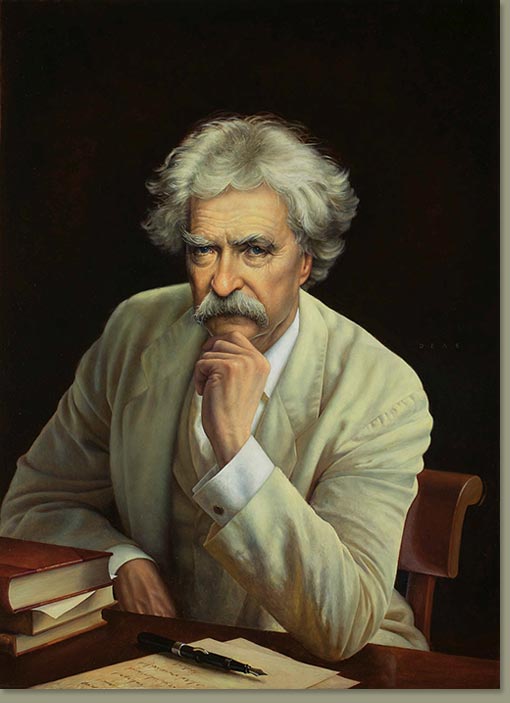

Mark Twain Observes 1890 Pennsylvania Politics

|

| Mark Twain |

Mark Twain's Notebook, Aug. 1890-June 1891:

" Wm.Penn achieved the deathless gratitude of the savage by merely dealing in a straightforward way with them--well, kind of a square way, anyhow--more rectangular than the savage was used to, at any rate. He bought the whole state of Pa from them and paid for it like a man. Paid $40 worth of glass beads and a couple of second-hand blankets. Bought the whole State for that. Why you can't buy its legislature for twice the money now."

Mary Cassatt

|

|

The most famous Philadelphia Cassat shows a mother driving an open carriage with small daughter beside her, and her brother on the back seat. |

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is variously proclaimed as the greatest woman artist ever, and America's greatest impressionist painter of either sex. She is thus, from a Philadelphia perspective, the greatest Philadelphia woman artist. Mary was, in truth, born in Pittsburgh spent most of her artistic career in Paris, and relatively few of her numerous pictures are to be found in Philadelphia. But she spent four years training at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, her family moved to Philadelphia, and what is most important of all, her brother Alexander was president of the Pennsylvania Railroad at a time when such a position was nearly the same as being King.

|

|

Alexander Cassatt President of the Pennsylvania Railroad |

Almost all of her many paintings used members of her family as models, and almost invariably the paintings portray women or young girls. If there is a male in the picture (and there are a few), you have to recheck the label to be sure it is a Cassatt. This bias raises questions about her private life, which she would certainly have regarded as no one's business. She was the long-term competitor of a slightly less famous Philadelphian Paris artistic exile, Cecili a Beaux, and she was very active in the suffragette movement. On the other hand, she had a forty-year relationship with Degas, with whom she was professionally very close, as well as personally.

Mary Cassatt was a classmate at the Pennsylvania Academy of Thomas Eakins, but they did not get along. The master anatomist and the greatest woman impressionist were certainly hampered by professional disagreement; apparently they both took it personally.

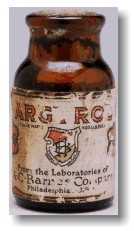

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

A private investor has the general goal of accumulating enough wealth so, come what may, there will be a little left when he dies. If he has dependents or heirs, he needs somewhat more. Either way, he is not planning for perpetuity or thinking in astronomical time periods. Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) had to switch his investment goals, in the 1920s, from investing for a comfortable retirement to investing for a perpetual art foundation. Perpetual.

|

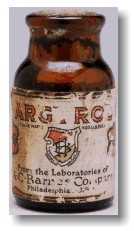

| A bottle of Argyrol |

Having graduated from medical school (University of Pennsylvania) in 1902, and then writing a doctoral thesis in chemistry and pharmacology at the Universities of Berlin and Heidelberg, Barnes invented a patent medicine that quickly made him rich. Argyrol was a mildly effective silver-containing antiseptic with the unfortunate tendency to turn its users permanently slate-gray. The advent of antibiotics has since made Argyrol almost sound like quackery, but it was effective enough at the time to require factories in America, Europe, and Australia, and Barnes became immensely rich with it. The American Medical Association strongly disapproves of physicians who patent remedies, so Barnes was never held in high regard by his colleagues; but it could well be argued that he had as much training as a chemist as a physician, and spent his entire professional life as a chemist, manufacturer, and investor.

|

| The Barnes Gallery |

Barnes was eccentric, all right, but on Wall Street, the saying goes, "What everyone knows, isn't worth knowing." Guided by that principle, in 1929 he sold his company at the very peak of market euphoria, getting out of common stocks at the top of the market. It is small wonder that he soon instructed his Foundation to invest its endowment entirely in bonds. During the 1930s, commodities were extremely cheap because no one had any money. Barnes, of course, had a potful of money and bought hundreds, even thousands, of artworks very cheaply. He also bought 137 acres of Chester County, PA, real estate, and a 12-acre arboretum in Merion Township on the Main Line. Although he is famous for acquiring hundreds of French Impressionist paintings with the advice of Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo, he also bought great quantities of Greek and Roman classical art, African art, and the art of the Pennsylvania German community. He picked up a notable collection of metallic art objects. Most of these "losers" are down in the basement because he had so many Renoirs, Matisse, and Picasso (some of them may be worth $200 million apiece) that the upstairs galleries were pretty well stuffed with them. Viewed from the perspective of an investor with a goal of perpetuity, of course, the things in the basement just happen to be temporarily out of fashion, just like those bonds in the portfolio.

|

| A view inside the Barnes gallery |

Since the Foundation is currently strapped for ready cash, Judge Stanley Ott of the Montgomery County Orphans Court is now being urged to allow the Foundation to break Barnes' will in some way or other. Move the museum to downtown Philadelphia where it can attract more paying visitors. Sell some of that land. Sell some of those paintings in the cellar. Fire some of those employees. But all of these suggestions are short-term solutions, which may injure the long term. Everybody has an idea of what Barnes the rich eccentric would have done if he were alive to do it, but I suspect he would have rejected the whole lot. Barnes the shrewd investor would have taken the most expensive painting off the wall, and sold it to the highest bidder. Buy low, sell high, and the niceties of non-profit professionals are damned. Barnes wasn't in love with one single painting, or one particular school of painterly interpretation, he was in love with Art.

Investment theory has improved in the past fifty years; there have even been some Nobel prizes awarded for new insights. But it still isn't possible to put an investment portfolio on autopilot for perpetuity. Every museum, university, and the foundation has the same problem, with the result that the landscape is littered with the bones of perpetual organizations destroyed by following a fixed formula. With the singular success that Barnes displayed, it isn't surprising that he went a little too far with instructing his successor trustees in what to invest in. Never sell the paintings or the real estate, avoid the common stock, were ideas that worked brilliantly, and may even work most of the time. But sooner or later, the institution will be endangered by following them too literally. Somebody has to have some flexibility. But there is something else that is inevitable, too. Sooner or later, whether it takes fifty years or five hundred years, sooner or later someone will be given the responsibility and the necessary flexibility -- but will try to run off with the boodle, for himself. The balance between necessary prudence and necessary flexibility is impossible to maintain forever, and the Judge will surely have a hard time deciding what Barnes would have decided.

Margaret of Anjou (1)

|

| Margaret of Anjou |

Margaret of Anjou (1430-1482) died and was buried two centuries before William Penn arrived on the Delaware River. She'd been Queen of England as the wife of Henry VI from 1445-1471, and a central figure in the so-called War of the Roses. Not a name plausibly associated with Philadelphia.

|

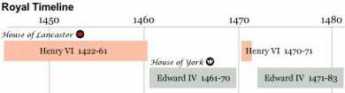

| Henry VI |

Until, of course, you understand that the Shakespeare Society of Philadelphia, world's oldest continuously meeting Shakespeare club, is making her a current focus of attention. It was the idea of Robert Thomas Fallon, the vice-dean of the society, that Margaret of Anjou appears in four Shakespeare plays. The three histories of >Henry VI and Richard III all get relatively little present attention, but perhaps parts could be extracted and fused into one great play about Margaret. Think of that, a new Shakespeare play after all these centuries.

|

| English-occupied France at the time of Henry VI |

Disconcertingly, when you examine what the new play would be all about, there's more material than you can handle. Margaret starts out as the most beautiful girl in France and ends up as a scolding, vicious old hag; is that the story, or is it really two plays? The Duke of Suffolk had it in his power to make this starlet into Queen of England if she perhaps cared to visit his casting couch. Her answer was she had to ask her father, and if you believe that, you will believe anything. With the right stage directions you might imply she was a remarkably dutiful victim unless the stage directions strongly implied: OK, buddy, you've got a deal.

That's just the beginning, almost the preliminary. You can go on to portray her quite another way, as the ambitious mother of the Prince of Wales, about to lose his title to the throne because his cuckolded father was a useless coward. She wasn't going to let that happen, no matter who got stabbed to prevent it.

Or, Margaret the Survivor, losing battles with the York faction, then like Saint Joan rallying the hesitant Lancastrians to lose yet another battle and get killed some more. Then fleeing over the channel, to see if the King of France couldn't be sweet-talked into supporting her cause. Thanks, pal; and then she lost his army, too. As we say in South Philadelphia, that dame is Big Trouble.

The Shakespeare (be sure you spell it right) Society meets regularly in a cobble-stoned alley near the Philadelphia theater district. The tables don't have carved initials on them, like Mory's, but they don't have tablecloths, either. They admit a new member every few years when someone dies, and they take their Elizabethan literature pretty seriously. The Variorum Shakespeare was created by this group. It was founded by Horace Howard Furness, the brother of Frank Furness the architect. That name is pronounced a little funny, too, which if you are from Philadelphia I don't need to instruct you about.

|

| the battles and kings associated with the War of the Roses |

Laboring under the burden of this intellectual heritage, the society has to consider some broader implications of the story of Margaret of Anjou. The deconstructionists who have recently achieved university tenure tend to challenge most of the settled views on Shakespeare, but in this matter, we start with a fresh slate. Doesn't the chaotic period of the War of the Roses stand between two strong Kings, Henry V of Agincourt, and Henry VIII? Wouldn't Shakespeare, that stalwart defender of anointed majesty, have approved the moral that any strong king is better for the nation than any weak one? Maybe that's a theme that should run through our new Shakespearean play. Maybe our play ought to start with Henry V on a high step behind a stage screen, giving his speech to rally the English longbows (We happy few, we band of brothers); and end with Henry VIII, always ready to rise above principle.

Or perhaps the play might make English-French relationships be the core, from William the Conqueror through five centuries, until the English finally do discard the Continent, and Britannia rules the waves. It's a little hard to imagine Shakespeare, the ultra-English patriot, as an apologist for a united Europe, but perhaps it could be managed.

If that seems too partisan, perhaps Philadelphia could find a peaceful theme. What, after all, was accomplished by the War of the Roses? Does anyone really care who got promoted from earl to Duke, or whose great-grandfather had which great grand nephew? One is reminded that the two branches of Philadelphia Quakerdom, the Hicksites and the Orthodox, for a century scolded each other bitterly over doctrinal matters of little present concern. And then Rufus Jones brought them together for annual luncheons, giving a white rose to members of one faction as they entered the door, and a red rose to members of the other. The rules of the luncheon were always the same: nobody could sit next to a person wearing the same color of rose.

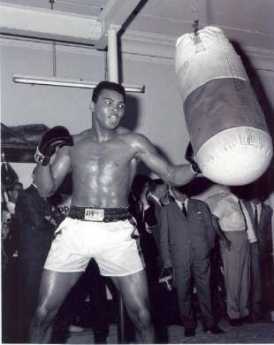

Mohammed Ali, Cassius Clay

|

| Mohamed Ali |

He doesn't live there any more, but for a long time Mohamed Ali the Prizefighter lived in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Although a celebrity, he made little local news in Philadelphia; comparatively few Philadelphia's even knew he was here. One day, my ten-year-old son came in the house with a check endorsed by Ali for a hundred dollars or so. It had apparently flown out the window of a passing car, and my son was very excited to have the autograph of such a famous person. There was an ethical question here, since the check was apparently worth something to its owner, and should be returned. My suggestion was followed to mail the check back with a note suggesting that perhaps the Great Man would be willing to send his autograph as a reward. The check was accepted, but the letter was never answered, no autograph was forthcoming.

Since that time I remained a little irked that Mohamed Ali would be ungrateful for the favor, unwilling to take a little trouble to help me teach my children the right thing to do. That small, perhaps unwarranted, irritation was balanced by reports from a respected friend of mine who was his doctor. My friend always referred to him as "Champ" and never failed to praise him as a person. Perhaps the check incident had been some sort of accident, something I should overlook.

There were those news reports, of course, of his refusal to accept the draft, his public conversion to Muslim faith and adopting a frankly Muslim name at a time when the perception was that black Muslim had the significance of a prison cult, both anti-American and anti-Western Society, perhaps even racist. Surrounded by news media as he was, he became a symbol of resistance to the Vietnam War and American foreign policy. It was hard to know what to think of him, but on balance it was unfavorable, even when he was reported to be incapacitated by crippling Parkinson's disease.

|

| sports |

And then recently, The Constitution Center held a forum on the relationship between sports and the media. The point was repeatedly made that a sports career is brief, that financial success in it depends heavily on fast and early publicity. All publicity is good publicity, so outsiders who seek to publicize a political agenda can often put their words into the mouths of eager kids who are being privately urged to grab publicity of any sort, anyway they can. You tell me what to say; I'll say it. Make me sound clever and serious; I'll agree to your words.

It thus happened that a reporter who had been covering Mohamed Ali for 25 years and knew him well was able to say he was certain the Champ had never had a political thought in his life. Having been pressured by others into making political noises for celebrity purposes, and perhaps under some intimidation by acquaintances, he finally rebelled against the whole scene. Respect for a man I had never met finally welled up in me when I thus saw his famous quotation to the press in a new context: " I don't have to be -- what you want me to be."

The Hogan Schism

These issues of controlling authority (ultimately quite parallel to the contrast between a monarchy and a republic) came to a head around 1820, when a charismatic Irish priest named William Hogan came to Philadelphia, and soon became the clear favorite of the trustees of the local church. There had previously been difficulty getting anyone to accept the contentious job of Bishop, but when Henry Conwell took the job, he soon decided that Hogan had to go. The trustees nevertheless supported Hogan, and it became necessary to appeal to Horace Binney,

|

| Horace Binney |

a non-catholic, to negotiate a solution. (Binney's son later became a founder of the Union League, and like his father was much respected for many civic accomplishments.) The outcome, unfavorable to Hogan, encouraged the Church to become much more forceful in exerting Vatican control over provincial churches, especially American ones.

So matters turned out one way for the Methodist-Episcopals and the opposite way for the Catholics. Each group now expresses satisfaction with the enduring effect on their system. However, it is clear that both top-down and bottom-up convictions are very unyielding, and are not confined to either religion or politics. Both philosophies are in fact seemingly resoundingly justified by occasional experiences, and therefore strongly persist to this day. Along the same lines, the election of bishops by the priesthood, and selection of the priests by the lay deacons are the central differences between the Church of England and the American Episcopalian Church. The evolved solution among the American Episcopalians has been the latitude to seek a "flying bishop" from somewhere else when the local bishop differs significantly from the viewpoints of some local parish. This has been a source of vigorous debate even recently, and even in the Philadelphia area.

While there is no need to stir up these dangerous embers, anyone who seeks to understand the issues which led to the American colonies going to war for independence from England, must understand this matter. Many historians would agree that the American Revolution was provoked by George III attempting to strengthen the monarchy at a moment in history when the colonists were seeking more local autonomy. All colonial institutions tended to reflect this central disagreement about autonomy in governance, but it is conceivable that the religious influenced the political more than the reverse. Tensions about authority were of course greatly magnified by the other notoriously strong religious dissensions of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century.

A Toast To J. William White, MD

JWilliam White left a legacy to the Franklin Inn, the income from which was to pay for an annual dinner, with all the trimmings. Good as its word, the Inn holds the J. William White dinner every year on Benjamin Franklin's birthday, although inflation and fluctuations of the stock market require it to make a modest charge for attendance. White also created the J. William White Professorship in Surgery at the University of Pennsylvania, a chair which was once occupied by Jonathan Rhoads.

|

| William J White MD |

These trust-fund memorials do little to convey the wild and glamorous image of Bill White. White was a member of the First City Troop and fought the last known honest-to-goodness duel on Philadelphia's field of honor (in the accidental "wedge" of disputed land between Delaware and Pennsylvania). The right and wrong of the argument about wearing the City Troop uniform are in dispute, but the details boiled down to White at the critical moment raising his gun to the sky and firing at the stars. That it was not a meaningless gesture was then brought out by his opponent ( a fellow Trooper named Adams) taking slow and deadly aim -- but missing him.

White was an academic in the sense that he was the first, unpaid, Professor of Physical Culture at the University of Pennsylvania. Active in the Mask and Wig Club, he was a chief surgeon at Philadelphia General Hospital, chief surgeon to the Philadelphia Police, and chief surgeon to the Pennsylvania Rail Road. He is the surgeon actually operating in Thomas Eakins' Agnew Clinic, while Agnew himself stands as the "rainmaker", to use a term from legal circles. He was Chairman of the Fairmount Park Commission, and numerous other positions where political contact was more important than surgical skill. When World War I came along, he was off to France with the University of Pennsylvania Hospital Unit, writing two books with Theodore Roosevelt. Although his friendship with Henry James suggests greater literary talent, he was supportive of Adams' transfer of citizenship in protest of America's staying out of World War I; but nonetheless, Roosevelt published more than thirty books. What emerges from the history of Bill White is flamboyance and lots and lots of unfettered energy. He might feel a little out of place at one of his endowed dinners today, but he was probably always a little out of place in any company -- and didn't care a whit.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

That Damned Cowboy

|

| Teddy Roosevelt |

Republican Presidential Convention of 1900 was held across the street from what is now Children's Hospital at 34th and Spruce Streets. Although the re-nomination of an incumbent President (McKinley) is always a boring, foregone conclusion, the Vice-Presidential nomination, in this case, was a hilarious circus. Boss Platt of New York hated Governor Teddy Roosevelt,and wanted him out of Albany. So he persuaded Boss Matthew Quay of Pennsylvania to engineer Roosevelt's nomination as Vice President, which Quay did by threatening to deprive the Southern states of half their seats at the next convention, then relenting when they agreed to vote for Roosevelt. This was highly displeasing to Boss Mark Hanna of Ohio, the National Chairman, who didn't like Roosevelt and hated even worse to be beaten on any issue. It looked like Roosevelt was going to win, except for one thing. Roosevelt didn't want the job, which is a notorious political dead end. In the event, after much scheming and rumoring, Roosevelt was the unanimous choice of the convention, except for one vote. He voted against himself.

The Convention presented two other ironies. The first was that everybody had it all wrong. McKinley was assassinated, and Roosevelt became President. Everyone involved would surely have voted the other way if it had been known what would happen.

The other irony was contained in a large electric sign on Broad Street during the convention. Two thousand light bulbs, quite a novelty for the time, displayed in large letters: THE PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER. MORE REPUBLICAN READERS THAN ANY PAPER IN THE COUNTRY.

The Battle of Germantown: Oct. 3, 1777

After its brief commotion from the unwelcome French and Indian War, Germantown settled down to a 22-year period of colonial inter-war prosperity and quite vigorous growth. Most of the surviving hundred historical houses of the area date from this period, and it might even be contended that the starting of the Union School had been a beneficial stimulus.

|

| Cliveden |

Two decades passed. What we now call the American Revolution started rumbling in far-off Lexington and Concord, soon moved to New York and New Jersey. General William Howe, the illegitimate uncle of King George III, then decided to occupy the largest city in the colonies, tried to get his brother's Navy up Delaware but hesitated to persist in a naval attack on the chain barrier blocking the river. He considered but abandoned trying to outflank the New Jersey fort at Red Bank, the land-based artillery at Fort Muffling, and heaven knows what else along the twisting shaggy Delaware river. Giving up on that approach, Howe sent the navy down to Norfolk and back up the Chesapeake, landing the troops at the head of the Elk River. Washington was outflanked at the Battle of the Brandywine Creek trying to head him off, although he suffered far fewer casualties than the British. A rainstorm, presumably a fall hurricane, disrupted his planned counterattack near Paoli. So Howe invested Philadelphia, organizing his main defensive position in the center of Germantown. His headquarters were in Stenton and Morris House, General James Agnew was at Grumblethorpe The Center of British defense was at set up at Market Square where Germantown Avenue crosses Schoolhouse Lane. With Washington retreating to Valley Forge, that should take care of that. Raggedy rebels were unlikely to attack a prepared hilltop position with a river on either side, defended by a large number of British regulars.

|

| George Washington |

Washington did not look at things that way, at all. Cut off from their fleet, the British situation would be precarious until Delaware could be re-opened. He had watched General Braddock conduct with bravado an arrogant suicide mission in the woods near Ft. Duquesne, and also knew the British always based as much strategy as possible on their navy. Washington's plan was to attack frontally down the Skippack Pike with the troops under his direct command, while Armstrong would come down Ridge Avenue and up from the side. General Greene would attack along Limekiln Road, while General Smallwood and Foreman would come down Old York Road. In the foggy morning of October 3, the main body of American troops reached Benjamin Chew's massive stone house, now occupied by determined British troops, and General Knox decided this was too strong a pocket to leave behind in his rear. Precious time was lost with an artillery bombardment, and unfortunately, the flanking troops down the lateral roads were late or did not arrive at all. The forward movement stopped, then the British counter-attacked. Washington was therefore forced to retreat, but he did so in good order. The battle was over, the British had won again.

But maybe not. Washington hadn't routed the British Army or forced them to leave Philadelphia. They did leave the following year, however, and there was meanwhile no great desertion from the Colonial cause. Washington's troops suffered terrible privation and discouragement at Valley Forge, but the crowned heads of Europe didn't know that. For reasons of their own, the French and German monarchs were pondering whether the American rebellion was worth supporting, or whether it would soon collapse in a round of public hangings. From their perspective, the Americans didn't have to win, in fact, it might be useful if they didn't. But if they were spirited and determined, led by a man who was courageous and resolute, their damage to the British interests might be worth what it would cost to support them. The Battle of Germantown can thus be reasonably argued to have been an advancement of colonial goals, even if it could not be called a victory. However, when the news of Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga soon reached them, the European enemies of England decided the colonists would be useful allies.

In Germantown itself, the process of turning a military defeat into a strategic victory soon began, with severe alienation of the German inhabitants against the destructive experiences of British military occupation. After a winter of near starvation, Germantown would never again see itself as the capital city of a large German hinterland. It was on its way to becoming part of the city of Philadelphia.

The Heirs of William Penn

|

| William Penn |

Freedom of religion includes the right to join some other religion than the one your father founded; William Penn's descendants had every right to become members of the Anglican church. It may even have been a wise move for them, in view of their need to maintain good relations with the British Monarch. But religious conversion cost the Penn family the automatic political allegiance of the Quakers dominating their colony. Not much has come down to us showing the Pennsylvania Quakers bitterly resenting their desertion, but it would be remarkable if at least some ardent Quakers did not feel that way. It certainly confuses history students, when they read that the Quakers of Pennsylvania were often rebellious about the rule of the Penn family.

|

| Delaware |

Such resentments probably accelerated but do not completely explain the growing restlessness between the tenants and the landlords. The terms of the Charter gave the Penns ownership of the land from the Delaware River to five degrees west of the river -- providing they could maintain order there. King Charles was happy to be freed of the expense of policing this wilderness, and to be paid for it, to be freed of obligation to Admiral Penn who greatly assisted his return to the throne, and to have a place to be rid of a large number of English Dissenters. The Penns were, in effect, vassal kings of a subkingdom larger than England itself. However, they behaved in what would now be considered an entirely businesslike arrangement. They bought their land, fair and square, purchased it a second or even third time from the local Indians, and refused to permit settlement until the Indians were satisfied. They skillfully negotiated border disputes with their neighbors without resorting to armed force, while employing great skill in the English Court on behalf of the settlers on their land. They provided benign oversight of the influx of huge numbers of settlers from various regions and nations, wisely and shrewdly managing a host of petty problems with the demonstration that peace led to prosperity, and that reasonableness could cope with ignorance and violence. When revolution changed the government and all the rules, they coped with the difficulties as well as anyone in history had done, and better than most. In retrospect, most of the violent criticism they engendered at the time, seems pretty unfair.

|

| John Penn |

They wanted to sell off their land as fast as they could at a fair price. They did not seek power, and in fact surrendered the right to govern the colony to the purchasers of the first five million acres, in return for being allowed to become private citizens selling off the remaining twenty-five million. Ultimately in 1789, they were forced to accept the sacrifice price of fifteen cents an acre. Aside from a few serious mistakes at the Council of Albany by a rather young John Penn, they treated the settlers honorably and did not deserve the treatment or the epithets they received in return. The main accusation made against them was that they were only interested in selling their land. Their main defense was they were only interested in selling their land.

As time has passed, their reputation has repaired itself, and they bask in the universal gratitude which is directed to their grandfather and father, William Penn. Statues and nameplates abound. Nobody who attacked them at the time appears to have been really serious about it, except one. Except for Benjamin Franklin, who turned from being their close friend to being their bitter enemy. Franklin tried to destroy the Penns, traveled to England to do it, and after twenty years seemed just as bitter as ever. Something really bad happened between them in 1754, and neither the Penns nor Franklin has been open about what it was.

Sullivan's March

|

| Sullivan |

George Washington had plenty of other problems to contend with in 1778, but an Indian uprising led by Loyalists was too much. He singled out General John Sullivan, a celebrated Indian fighter from New Hampshire, gave him four thousand troops, and told him to eliminate this Indian threat to the Continental Army's rear, remove the safe haven for Loyalists, and assist the new Indian allies which LaFayette had befriended in the Albany area before the battle of Saratoga.

From long experience, Sullivan knew what to do, and did it without remorse. Ignoring skirmishes and ambushed sentries, he marched his troops from the scene of the massacre straight into the heart of Iroquois homeland, destroying every source of food or Indian settlement he could find. He was not interested in winning battles, he was determined to starve the Indians into extinction, once and for all. After these two slaughters, a white one in the Wyoming Valley (the Connecticut squatters in Wilkes-Barre), and now a red one in upstate New York, the entire frontier north of Pennsylvania has left a scene of devastation. Not much was heard of Indian fighting on this frontier for the rest of the Revolutionary War. Indeed, only the novels of James Fennimore Cooper make much subsequent mention of the Iroquois in American history.

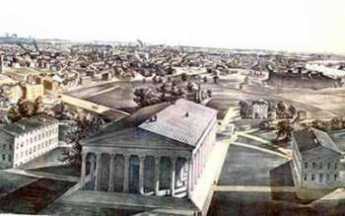

Stephen Girard and Religion

|

| Girard College |

In 1950, an elderly retired gentleman named Witherbee paid me a visit when I was temporarily covering practice for a doctor in Woodbury, New Jersey, in locum tenens, as we say. His medical problem was easily tended, and we chatted.

He told me that he had attended Harvard Divinity School many years before, and one day was about to graduate as an ordained minister. His family and many other proud families were gathered on folding chairs on the lawn in Cambridge to watch the graduation ceremonies. The graduates were called up one by one, in alphabetic order.

Since Witherbee is at the end of the alphabet, he had a lot of time to think over the significance of what the members of his class were doing. In time, thinking over the personal defects of each classmate who preceded him, he became overwhelmed with a personal question. "How can I tell others how to behave, when I don't know how to behave, myself?"

And so, when his turn came, his name was called out, and he rose in his seat. "I decline to graduate."

The consternation of his family can be imagined, along with the stir in the audience, the astonished face of the Dean, and his own confusion about the uproar he had just caused. But although the die was cast, and the action a final one, it had a surprising outcome. The next day, he received a telegram from the Girard College in Philadelphia, inviting him to be considered for the position of Director of Religious Studies. It seems that Stephen Girard had provided in his will that no ordained minister might set foot within the walls of Girard College, and yet they felt they needed someone to oversee the religious study. Witherbee was perfect: he had the credentials, but he did not have the ordination curse.

And so he happily remained in that capacity for the rest of his employed life.

REFERENCES

| Girard College It's Semi Centennial of Girard College: George P. Rupp ASIN: B000TNER1G | Amazon |

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

A fair lady's image depends, Bernard Shaw told us, not on how she acts, but on how she is treated. The case in point is a beautiful Main Line heiress in The Philadelphia Story, who can choose any man she wants. What she cannot do, is escape grief for a wrong choice.

When Broadway and Hollywood paint your image, not believing your own press releases takes strength. Toward the end of the Great Depression around 1938, show business turned full and nasty attention to Philadelphia high society. Earlier, while author Christopher Morley was at Haverford College, Katharine Hepburn at Bryn Mawr College, and Grace Kelly at school on Schoolhouse Lane, Hollywood had picked up just enough authentic detail to be dangerous. Kitty Foyle and The Philadelphia Story are two fairly accurate snapshots of a complex society, but one cannot be fully understood without the other. Indeed, the real-life trivialities of Howard Hughes, Katharine Hepburn, Grace Kelly, and Ginger Rogers sharpen the outlines of the graceful gentlefolk they attempted to portray.

In 1938, Hepburn was a smash hit on Broadway with Philip Barry's Philadelphia Story, which essentially tells of the agonized turmoil of a Main Line princess, facing a three-way choice between a charming but worthless blue-blood, a self-made dullard, and a poor but noble New York magazine writer. (Just guess who the author was rooting for.) In real life, of course, Ms. Hepburn chose to spend four years with movie producer Howard Hughes the dare-devil Texan with a hundred starlets in his bedroom. Most of her competitors wanted a movie contract and/or a diamond bracelet, but Katy wanted the movie rights for Philadelphia Story, which Howard readily bought for her. Although other actresses played the role, she made herself into the image of a Philadelphia heiress, thereby nudging that Main Line image toward her own. At the time the image did not include much mention of Howard Hughes or actor Spencer Tracy, another long-time companion.

|

| Ginger Rogers |

Meanwhile, Ginger Rogers, who was also engaged to Howard Hughes at one point, was making a great name for herself as the star of Christopher Morley's Kitty Foyle. Morley's Haverford experience taught him somewhat more respect for the Philadelphia Gentleman than Barry ever had, while his experience at the Curtis Publishing Company also made him appreciate the smart and plain-spoken Philadelphia girls from working-class districts. Highborn Philadelphia women are only sketchily imagined by Morley, except they somehow fail to appeal to his manly fictional cricket-player from the Main Line.

As matters turned out, Katy lost to Kitty. Although Hepburn was surely the more talented actress, eventually winning five Academy Awards, Ginger Rogers walked away with the 1940 Oscar for her interpretation of a working-class Philadelphia lady. Either way it turned out, of course, Howard Hughes was bound to be a happy fellow.

|

| Grace Kelly |

And yes, in 1956 Grace Kelly was the star of High Society, a renamed version of the Philadelphia Story for which, remember, Katherine Hepburn still controlled the rights. The film was a mediocre performance, just a little short of embarrassing. But however inexact all three of these portrayals may have been, there is little doubt that Philadelphia society moved a bit in their direction, involuntarily living up to an image created by three observers who seemed to their own observers to retain hostility traceable to their own undefined turmoils.

Philip Barry stacks the deck somewhat, portraying the leading lady as movie audiences during the Depression were likely to fantasize, indulging a luxury only a rich girl would supposedly be careless about. She rejects the colorless rich suitor out of hand. But while her remaining choice between a charming magazine writer and a charming playboy is made to seem a closer call, it really never makes our Philadelphia Cleopatra hesitate very long. In the single editorial comment, the play's author permits himself, is tucked the snarl, "She's a lifelong spinster, no matter how many times married." That's New York talking. Bitter, bitter.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Gentlemen: The Making of a National Upper Class: E. Digby Baltzell ISBN-13: 978-0887387890 | Amazon |

Philadelphia in 1658

|

| Annals of Philadelphia |

Of all the settlers prior to Penn, I feel most interested to notice the name of Jurian Hartsfield, because he took up all of Campington, 350 acres, as early as March 1676, nearly six years before Penn's colony came. He settled under a patent from Governor Andros. What a pioneer, to push on to such a frontier post! But how melancholy to think, that a man, possessing the freehold of what is now cut up into thousands of Northern Liberty lots, should have left no fame, nor any wealth, to any posterity of his name. But the chief pioneer must have been Warner, who, as early as the year 1658, had the hardihood to locate and settle the place, now Warner's Willow Grove, on the north side of the Lancaster Road, two miles from the city bridge. What an isolated existence in the midst of savage beasts and men must such a family have then experienced! What a difference between the relative comforts and household conveniences of that day and this! Yea, what changes did he witness, even in the long interval of a quarter of a century before the arrival of Penn's colony! To such a place let the antiquary now go to contemplate the localities so peculiarly unique!"

--John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania in the Olden Time

Philadelphia: Charles Dickens Gives an 1842 Viewpoint

|

| Charles Dickens |

In 1842, Charles Dickens wrote a short summary of Philadelphia for the readers back home in London-

My stay in Philadelphia was very short, but what I saw of its society, I greatly liked. Treating of its general characteristics, I should be disposed to say that it is more provincial than Boston or New York and that there is a float in the fair city, an assumption of taste and criticism, savoring rather of those genteel discussions upon the same themes, in connection with Shakespeare and the Musical Glasses, of which we read in the Vicar of Wakefield.

20 Blogs

John Bogle, A Prophet In Our Valley

John Bogle invented the index fund. Lower cost, better performance.

John Bogle invented the index fund. Lower cost, better performance.

A Toast to Doctor Franklin

The Franklin Inn annually toasts three doctors. Even though Ben never went past second grade, his medical contributions are the most illustrious of the three. One of the most remarkable men who ever lived.

The Franklin Inn annually toasts three doctors. Even though Ben never went past second grade, his medical contributions are the most illustrious of the three. One of the most remarkable men who ever lived.

Franklin: Upstart Hero of King George's War (1747)

'King George's War' was two wars prior to the Revolution. Ben Franklin raised an army when the Quaker proprietors' wouldn't. The experience maybe gave him ideas.

'King George's War' was two wars prior to the Revolution. Ben Franklin raised an army when the Quaker proprietors' wouldn't. The experience maybe gave him ideas.

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

How one of Britain's most notorious philosophers wandered into the city of brotherly love and vaulted out of destitution to wealth.

How one of Britain's most notorious philosophers wandered into the city of brotherly love and vaulted out of destitution to wealth.

Marty Feldstein Forecasts the Future

Reading between the lines, Martin Feldstein announces his view that the Treasury must allow the dollar to weaken. Soon.

Reading between the lines, Martin Feldstein announces his view that the Treasury must allow the dollar to weaken. Soon.

Mark Twain Observes 1890 Pennsylvania Politics

Our politicians were a joke, even a century ago.

Our politicians were a joke, even a century ago.

Mary Cassatt

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is variously proclaimed as the greatest woman artist ever, and America's greatest impressionist painter of either sex. She is thus, from a Philadelphia perspective, the greatest Philadelphia woman artist.

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (1844-1926) is variously proclaimed as the greatest woman artist ever, and America's greatest impressionist painter of either sex. She is thus, from a Philadelphia perspective, the greatest Philadelphia woman artist.

Albert C. Barnes, M.D.

Impressionist paintings grew more valuable, faster than the patron's endowment for their maintenance.

Impressionist paintings grew more valuable, faster than the patron's endowment for their maintenance.

Margaret of Anjou (1)

The Shakespeare Society of Philadelphia is constructing a new play about Margaret of Anjou, out of parts of four plays in which William Shakespeare has her appear.

The Shakespeare Society of Philadelphia is constructing a new play about Margaret of Anjou, out of parts of four plays in which William Shakespeare has her appear.

Mohammed Ali, Cassius Clay

The greatest prizefighter of all time. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.

The greatest prizefighter of all time. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.

The Hogan Schism

What happens when the parish likes the local priest better than the Bishop, and the Bishop is stupid enough to make an issue of it?

What happens when the parish likes the local priest better than the Bishop, and the Bishop is stupid enough to make an issue of it?

A Toast To J. William White, MD

Franklin Inn holds the J. William White dinner every year on Benjamin Franklin's birthday. A surgeon, author, politician, athlete, cavalryman, and duelist, Bill was a real Philadelphia gentleman.

Franklin Inn holds the J. William White dinner every year on Benjamin Franklin's birthday. A surgeon, author, politician, athlete, cavalryman, and duelist, Bill was a real Philadelphia gentleman.

That Damned Cowboy

and The political bosses wanted to get Teddy Roosevelt out of the Governor's chair in Albany. As things turned out, they made him President of the United States.

and The political bosses wanted to get Teddy Roosevelt out of the Governor's chair in Albany. As things turned out, they made him President of the United States.

The Battle of Germantown: Oct. 3, 1777

The Heirs of William Penn

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

Sullivan's March

With Washington beleaguered at Valley Forge, an Indian massacre of the nearby Wyoming Valley was a serious threat from the rear. General Sullivan was sent to exterminate the Iroquois, and proved utterly ruthless.

With Washington beleaguered at Valley Forge, an Indian massacre of the nearby Wyoming Valley was a serious threat from the rear. General Sullivan was sent to exterminate the Iroquois, and proved utterly ruthless.

Stephen Girard and Religion

The great philanthropist was, to say the least, anti-clerical. A real-life story tells how far this was carried.

The great philanthropist was, to say the least, anti-clerical. A real-life story tells how far this was carried.

Show Biz Image: Hepburn, Rogers, Kelly

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Hollywood presented a cartoon of the upper class during the Depression. World War II was soon to sober us up.

Philadelphia in 1658

The Annalist John Watson reflects on the earliest scenes in Philadelphia.

The Annalist John Watson reflects on the earliest scenes in Philadelphia.

Philadelphia: Charles Dickens Gives an 1842 Viewpoint

Dickens liked Philadelphia a lot, but he was still a little patronizing.

Dickens liked Philadelphia a lot, but he was still a little patronizing.