6 Volumes

Philadelphia Medicine

Several hundred essays on the history and peculiarities of Medicine in Philadelphia, where most of it started.

Sociology: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The early Philadelphia had many faces, its people were varied and interesting; its history turbulent and of lasting importance.

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Health: Philadelphia

New volume 2014-08-04 22:18:40 description

Pre-Revolutionary Ben Franklin

Poor Richard was able to retire at the age of 42, and spent the rest of his life as a rich man, dying at the age of 82 with an eye-popping estate.

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

Philadelphia Medicine

The first hospital, the first medical school, the first medical society, and abundant Civil War casualties, all combined to establish the most important medical center in the country. It's still the second largest industry in the city.

Nation's First Hospital, 1751-2016

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

As commonly stated in medical history circles, the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital is the history of American medicine. The beautiful old original building, with additions attached, still stands where it did in 1755, a great credit to Samuel Rhoads the builder and designer of it. The colonial building on Pine Street stopped housing 150 patients around 1980, supposedly at the demand of the Fire Marshall, although its perpetual fire insurance policy still owes the hospital several thousand dollars a year as an unspent premium dividend. There may have been one small fire during two centuries of use, but its true fire hazard would be difficult to assert. It was just out of date. The original patient areas consisted of long open wards, with forty or so beds lined up behind fluted columns, in four sections on two floors. The pharmacy was on the first floor, the lunatics in the basement, and the operating rooms on the third floor under a domed skylight. It was entirely serviceable in 1948 when I arrived as an intern doctor. Individual privacy was limited to what a curtain between the beds would provide, but on the other hand, it was possible for one nurse to stand at the end of the award and recognize any distress among forty patients immediately. In this trade-off between delicacy and utility, the utility was certain to be preferred by the Quaker founders. Visitors were essentially excluded, and if a patient recovered enough to be unnaturally curious about neighboring patients, well, he had probably recovered enough to go home.

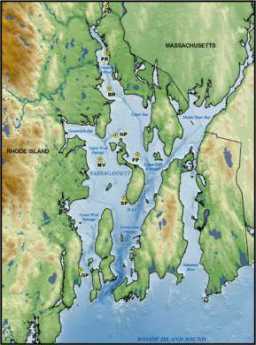

Located between two large rivers, South Philadelphia up to ten blocks away was essentially a swamp until the Civil War. So, there were seasonal epidemics of malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and poliomyelitis at the hospital until the early twentieth century. Philadelphia was a port city, so sailors brought in cases of venereal disease, scurvy, even an occasional case of anthrax or leprosy. During the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, tuberculosis, rheumatic fever, and diphtheria were part of clinical practice. But underlying the ebb and flow of environmental effects, there was a steady population of illness which did not change a great deal from 1776 to 1948. These patients were all poor, because the rules in Benjamin Franklin's handwriting restricted service to the "sick poor, and only if there is room, for those who can pay." In 1948 there was a poor box for those who might feel grateful, but no credit manager or official payment office. The matter had been considered, but the cost of collection was considered greater than the likely revenue. When Mr. Daniel Gill was offered the position as the hospital's first credit manager, it was suggested that he be given a tenth of what he collected. To his lifelong regret, Dan Gill regretted that he refused an offer that he had felt he could not afford to accept.

So, the wards were filled with victims of the diseases of poverty, punctuated by occasional epidemics of whatever was prevalent. And a second constant feature of the patients was their medical condition forced them to be housed in bed. For centuries, physicians dreaded the news that a new patient was being admitted with "dead legs".

Franklin Crown Soap

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

It's easy to make soap, but hard to make good soap. You just boil animal fat with wood ashes, and you get soft soap. Softsoap was sold by the barrel in the Colonies. Hard soap is made by adding salt to the mix, allowing it to be sold by the bar. The trick to all this is to know how long to boil it, how much ash of what kind, and how much salt. If you get it wrong it will be too soft or too hard, and if you have too much lye from the ashes, it will burn your skin when you wash with it. Most people made their own soap in the colonies, so they often got it wrong, because they didn't exactly know what they were doing. What they were doing was called Saponification, after the old Roman hill of Sapo. The legend is that burnt animal sacrifices in the Temple at the top of the hill would wash down and help the washerwomen in the river below get their clothes clean. The point of all this is that Josiah Franklin, the father of Benjamin and sixteen other children, was a candle maker and a soap boiler. Somehow he got the recipe right, particularly the part about adding salt, and made famously fine bars of soap with a crown stamped on them -- Crown soap. The formula was a strict family secret, the source of family discord when one sister let it out.

The point which needs reflection is that nobody in Franklin's family ever heard of potassium hydroxide, saponification, triglycerides or fatty acids. The process of achieving fame throughout the colonies -- for making a product everyone could make haphazardly -- must have involved a careful series of experiments with different fats, tallows and lards, with different amounts of ashes of various trees, and different amounts of salt. When you got it right it worked consistently, but it would have been necessary to make many experiments to get it right. To avoid repeating the same mistakes, it would be necessary to keep careful records. In other words, little Benjamin must have observed a great many examples of experimental chemistry which made him a chemist fit to talk with Lavoisier and Priestly on equal terms, even though he quit school after the second grade. His childhood was one long demonstration of a motto of Claude Bernard: "Experiment first, a theory later."

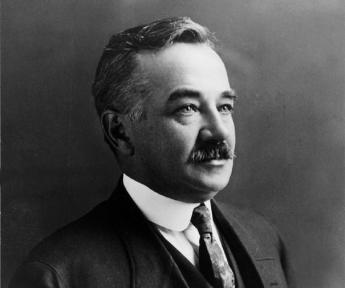

Pembertons

|

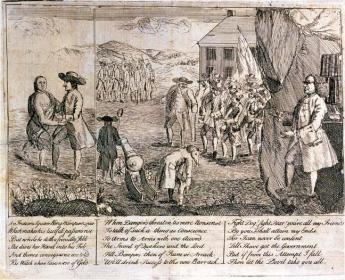

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

A Toast to Doctor Franklin

|

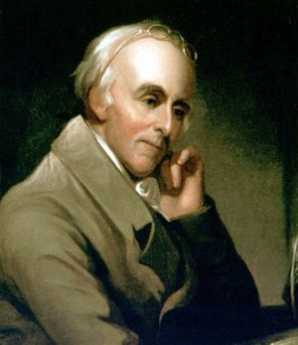

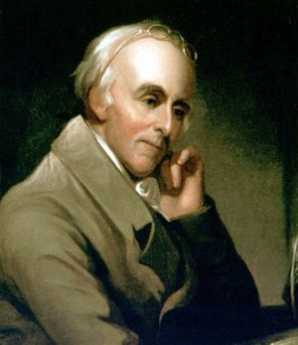

| Benjamin Franklin |

Benjamin Franklin's formal education ended with the second grade, but he must now be acknowledged as one of the most erudite men of his age. He liked to be called Doctor Franklin, although he had no medical training. He was given an honorary degree of Master of Arts by Harvard and Yale, and honorary doctorates by St.Andrew and Oxford. It is unfortunate that in our day, an honorary degree has degraded to something colleges give to wealthy alumni, or visiting politicians, or some celebrity who will fill the seats at an otherwise boring commencement ceremony. In Franklin's day, an honorary degree was awarded for significant achievements. It was far more prestigious than an earned degree, which merely signified adequate preparation for potential later achievement.

And then, there is another subtlety of academic jostling. Physicians generally want to be addressed as Doctor, as a way of emphasizing that theirs is the older of the two learned professions. A good many PhDs respond by rejecting the title, as a way of sniffing they have no need to be impostors. In England, moreover, surgeons deliberately renounce the title, for reasons they will have to explain themselves. Franklin turned this credential foolishness on its head. Having gone no further than the second grade, he invented bifocal glasses. He invented the rubber catheter. He founded the first hospital in the country, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and he donated the books for it to create the first medical library in the country. Until the Civil war, that particular library was the largest medical library in America. Franklin wrote extensively about gout, the causes of lead poisoning and the origins of the common cold. By inventing bar soap, it could be claimed he saved more lives from the infectious disease than antibiotics have. It would be hard to find anyone with either an M.D. degree or a Ph.D. degree, then or now, who displayed such impressive scientific medical credentials, without earning -- any credentials at all.

July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

According to the records of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the following 48 persons were patients in the hospital on July 4, 1776:

| Richard Brinkinshire (Admitted 11/15/1775) | John Ridgeway (Admitted 12/26/1775) |

| James Chartier (Admitted 1/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/6/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) |

| Mary Yell (Admitted 2/7/1776l) | John Beckworth (Admitted 2/7/1776) |

| Bart. McCarty (Admitted 2/10/1776) | John King (Admitted 2/10/1776) |

| Robert Alden (Admitted 2/17/1776) | William Patterson (Admitted 3/6/1776) |

| Elizabeth Hanna (Admitted 3/9/1776) | John McMahon (Admitted 3/13/1776) |

| Mary Burgess (Admitted 3/23/1776) | Mary Anderson (Admitted 4/10/1776) |

| John Hatfield (Admitted 4/15/1776) | Eliza Haighn (Admitted 4/17/1776) |

| Charles Whitford (Admitted 4/24/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| Susanna Carrington (Admitted 5/8/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| William Johnson (Admitted 5/13/1776) | Lazarus Chesterfield (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| Mary Spieckel (Admitted 5/22/1776l) | William Edwards (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 5/23/1776, Lunatic) | Jane White (Admitted 5/25/1776) |

| Charles McGillop (Admitted 5/29/1776) | ---Fitzgerald (Admitted 6/1/1776) |

| Michael Rowe (Admitted 6/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 6/6/1776) |

| John Hughes (Admitted 6/12/1776) | Joseph Smith (Admitted 6/15/1776) |

| Esther Munro Lunda (Admitted 6/15/1776) | Mathew Coope (Admitted 6/19/1776) |

| Anne Patterson (Admitted 6/19/1776) | Thomas Savoury (Admitted 6/20/1776) |

| Rebecca Winter (Admitted 6/26/1776) | Elizabeth Manning (Admitted 6/26/1776) |

| Negro (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Elex. Scanvay (Admitted 6/24/1776) |

| Fanny Stewart (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Peter Barber (Admitted 6/29/1776) |

| Catherine Campbell (Admitted 6/29/1776) | Ann McGlauklin (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

| Elizabeth Lindsay (Admitted 7/3/1776) | Ann Jones (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

The records indicate the following diseases were the reason for admission of those patients. Although in Colonial times there was no medical delicacy to avoid offending readers, present privacy standards require that we strip the diagnoses from the name of the patient and list them independently. There is some overlap, sometimes making it difficult to judge which disorder caused the admission.

- Sore, poisoned or ulcerated legs: 16 cases

- Lunacy, mind or head disorders: 10 cases

- Syphilis: 7 cases

- Fever and Rheumatic fever: 7 cases

- Dropsy: 5 cases

- Gunshot: 4 cases

- Diabetes: 1

- Blindness with clear pupil: 1

- Spitting blood: 1 case

- Dislocated arm: 1 case

- Inflammation of face: 1 case

- Scurvy: 1 case

- broken arm: 1 case

The following physicians were elected at the Managers Meeting dated 5/13/1776:

- Dr. Thomas Bond

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Dr. John Redman

- Dr. William Shippen

- Dr. Adam Kuhn

- Dr. John Morgan

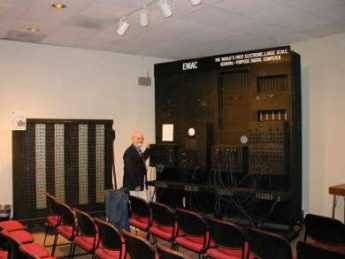

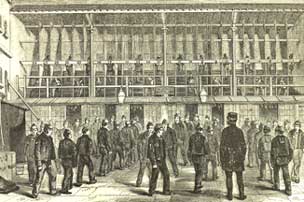

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

|

| South East Prospect of Pennsylvania Hospital |

There is a painting of the region around 8th and Spruce Streets in the 1750s, depicting a pasture, with cows, and three or four buildings between 8th and 13th Streets. When the Pennsylvania Hospital moved there in 1755 from its temporary location in a house located a block from Independence Hall, there were complaints that it was now located so far out in the woods that it was difficult and dangerous to go there. Still another description of the area is evoked by the provision which the Penn family placed in the deed of gift of the land, strictly forbidding the use of the land as a tannery. Tanneries have always been notorious for giving off noxious odors, so most people wanted them to be somewhere else, anywhere else. In any event, the main activity of Penn's "green country town" at that time was concentrated closer to the Delaware River, and the nation's first hospital was definitely placed in the outskirts. Two blocks further West the almshouse was already in place, but not much else. We are told that Benjamin Franklin had flown his Famous Kite at 9th and Chestnut, using a barn there to store his materials. It might be recalled that the population of Philadelphia, although the second largest English-speaking city in the world, was only about twenty-five thousand inhabitants at the time of the Revolution, and in 1751 was even smaller.

In any event, the first and oldest hospital in America was built on 8th Street between Spruce and Pine, and the Eighteenth Century buildings on Pine Street still present a breathtaking view at any season, but particularly in May when the azaleas are in bloom, and fragrance from the flowering magnolias fills the evening atmosphere for blocks around. Although some people today mistake the Pennsylvania Hospital for a state hospital, it was founded in the reign of George II, decades before there was such a thing as the State of Pennsylvania. The Cornerstone was laid by Benjamin Franklin, with full Masonic rites. Most doctors regard a hospital as a mere workshop, but the affection with which many Pennsylvania physicians regarded their special hospital is indicated by the number who have requested that their ashes be buried in the garden.

For two hundred years, beginning with the first American resident physician Jacob Ehrenzeller, the interns and residents were paid no salary, so they had to live on the grounds. An Internet was just that, interned within the four walls for at least two years. Because the resident physicians had no money, they stayed in the hospital at night and on weekends, playing cards and swapping stories. The hospital was home for them, as it was for the student nurses, likewise unpaid but more strictly confined and supervised. This penury seemed acceptable because the patients were mostly charity ward patients, otherwise unable to pay for their own care. Ehrenzeller finished his medical apprenticeship and went to practice for many decades in the farm country of Chester County, but gradually upper-class Philadelphia moved from 4th Street westward to and beyond the hospital, and two of the richest men in American history, Morris and Biddle, had houses within a block of the hospital, although Morris never lived in his house, having more pressing matters in debtor's prison. Therefore, later resident physicians at the hospital had the potential of setting up a private practice in the area and becoming society doctors as well as academically prominent ones. Being a charity hospital in a rich neighborhood created the potential for volunteer work by the town aristocrats and large bequests for charity. The British housed their wounded in the hospital during the Revolutionary War and shot deserters against the red brick wall of the small cemetery to the north. A century later, there were a couple of dozen rooms for private patients in the hospital for the convenience of the doctors and the neighbors, but everyone else was a charity patient. And a century after that, the hospital still did not have an accounting department to collect bills and tended to regard people who asked for a bill as a nuisance. Benjamin Franklin is regarded as the Founder of the hospital, and his autobiography famously describes how he fast-talked the legislature into matching the donations of the public, not mentioning to them that he had already collected enough promises to see the project through. This seems in character; Franklin's biographer Edmond Morgan summed up that, "Franklin doesn't tell us everything, but what he does tell us, is straight." The idea for the hospital was that of Dr. Thomas Bond, whose house is now a bed and breakfast on Second Street, but it was characteristic of Franklin to be the secretary of the first board of managers of the hospital. In Quaker tradition, the clerk of a meeting is the person who really runs the show. It thus comes about that the minutes of the founding board were recorded in Franklin's own handwriting, among them the purpose of the institution, which is to care for the Sick Poor, and if there is room, for Those Who can pay. This tradition and this method of operation continued until the advent in 1965 of Medicare when charity care was displaced by concepts which the nation had decided were better. The Pennsylvania Hospital was not only the first hospital but for many decades it was the only hospital in America. Its traditions, sometimes quaint and sometimes glorious, cast a long shadow on American medicine.

REFERENCES

| America's First Hospital: The Pennsylvania Hospital 1751-1841 William Henry Williams Ph.D. ISBN-10: 0910702020 | Amazon |

Pennsylvania Prison Society

|

| Duke of York |

William Penn, who spent considerable time in British prisons, established a penal code for his new colony which largely swept away the draconian punishments established by the code of the Duke of York. Until as late as 1780, jails were mainly confinement hotels for debtors, prisoners awaiting trial, and witnesses. For actual punishment, the methods were execution and flogging. Penn's Code for Pennsylvania restricted execution to the crime of murder, and flogging to sexual offenses; everything else was punished by fines and imprisonment. Hidden in this code, of course, was the need to invent and construct prisons to service the imprisonment. It would take over a century to address this need, and Philadelphia still has not completely caught up with the need for more prison cells. Without a prison system, the Penn code was impractical, and the colonial penal code retrogressed toward floggings, pillories, and hangings after Penn's death.

|

| Dr. Benjamin Rush |

In colonial Philadelphia, the main prison was on Walnut Street, with sixteen cells. A neighboring Quaker, Richard Wistar, started a soup kitchen in his own home, taking the soup over to prisoners. By 1773, he had established the Pennsylvania Society for Assisting Distressed Prisoners, which was unfortunately disbanded by the occupying British Army in 1777. In 1783, Dr. Benjamin Rush with the assistance of Benjamin Franklin, Bishop White, and the Vaux family, founded the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons, which after a century changed its name to the Pennsylvania Prison Society. The Prison Society believes it is the oldest continuous non-profit society in America.

|

| Eastern State Penitentiary |

The Prison Society has had several major changes in direction. The original concept was to substitute public labor for imprisonment, a less costly arrangement than imprisonment while avoiding a return to floggings and dismemberment. However, the degrading sight of prisoners in chain gangs caused a public outcry, and the approach was abandoned. In the spirit of the French and American revolutions, loss of liberty was seen as the greatest punishment conceivable. Added to this was the Quaker concept of inspiring remorse through silent meditation, and the eventual outcome was the construction of the Eastern State Penitentiary on what was then called Cherry Hill. In 1823, it was ominous that Eastern State Penitentiary was the largest structure in America. Although the concept was widely admired and imitated, the prolix Charles Dickens took a violent dislike to the idea of never talking to anyone, and led a reversion away from penitentiaries back to simple prisons. In the days before Alzheimers and schizophrenia were well characterized, the spectacle of massive recidivism was added to the rumor that protracted solitude led to insanity.

|

| Catherine Wise |

From Catherine Wise the Communications Director of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, the Right Angle Club recently learned that the current evolution of the American penal system has led to a steady state, but a troubled one. There are 2.2 million inmates in American prisons today, more than any other nation including Russia and China. Of these, 75,000 are confined in Pennsylvania, 9,000 in Philadelphia. Recidivism is 67%, the cost is $31,000 per year per inmate, the majority of inmates have been involved with illicit drugs, a growing number are infected with HIV and Hepatitis C, mental illness runs around 20%. The cost of incarceration is growing faster than the cost of either education or healthcare for the community. Prison overcrowding is extremely serious, the programs for managing parole and integration back into society are weak and underfunded. Eighty percent of the inmates are non-white, most prisons are located in remote regions too far for easy visiting, medical care in prison would not seem at all acceptable in general society. The Prison Society has no difficulty finding projects which are urgently needed. Just for an example, take the peculiar prison statistics; it really seems improbable that only 9,000 of the 75,000 Pennsylvania prisoners are in Philadelphia. Then reflect, NIMBY, that no one wants a prison or its visitors near his home, except areas of rural poverty welcome the employment a prison brings. Reflect for a moment that "jails" are paid for by local county taxes and contain prisoners with less than two years to serve. "Prisons" are paid for with state taxes, and contain those sentenced to longer than two years. Finally, add the fact that nonvoting Philadelphia prisoners in rural prisons are counted by the census as residents of the rural area for the purpose of distributing legislative and congressional seats. The rural politicians love the system, the urban neighbors love to be rid of the prison environment, but the prisoner families can't visit the prisoner. Who cares? Who even notices?

During the first World War, Quaker interest in prison matters was greatly stimulated by the imprisonment of many Quaker conscientious objectors to the wartime draft; since that time prison conditions have again become a central interest of the religion. It's hard to prove but is confidently asserted, that violence and mistreatment of prisoners are appreciably less in Pennsylvania than the rest of the country, California for example. In any event, The Pennsylvania Prison Society is a particularly effective advocate for humane treatment because of credibility achieved over two centuries, with newspaper editors on its board, and sympathetic affiliations with the legislative judicial committees. It knows what it is talking about, as a result of over 5000 annual prison visitations, and it has served the prison administrative corps by performing volunteer work, accepting contracts for parole projects, arranging bus trips for prisoner families to remote prisons, and working for improved funding for prisons. At the moment, there are six highly imaginative bills before the Pennsylvania Legislature, devised and researched by this outside organization with credibility, and political clout. Although the Society takes an occasional contract for a project, it is itself entirely funded by outside contributions, and because of occasional adversarial situations, asks for no funds from the state. Even the contract funds have been questioned, and are only accepted when the working relationships fostered are more useful for the prisoner clients than any co-option which might result.

One final word about medical care in prison. It's not as good as medical care for non-prisoners, and unfortunately it probably never can be. The remote rural location of prisons makes it difficult to obtain physicians and nurses, regardless of wage levels. It's dangerous to be around prisoners, as any guard will tell you, and it's more dangerous to be in control of narcotics amidst a population of addicted convicts. Malingering is nearly universal, both to obtain desired drugs and to spend "easy time" in the infirmary. Many prison escapes are engineered around the necessarily weakened security of the medical system. The prison budgeting system has all the rigidity and weaknesses of any governmental medical system, and in this case, it's run far out of sight of the public. Even the bureaucrats in charge are victimized by other bureaucrats. The average duration of incarceration in Pennsylvania is longer than in most other states; the prisons have to keep mental patients because the mental hospitals have all been closed. Fifty years ago, when there was no place to put a non-criminal with tuberculosis, he was put in jail. The parole system is underfunded, there is not nearly enough community support to absorb ex-con. Behind all this is a shortage of prison facilities. The legislature has got itself into a position that if it moved more prisoners into the outside, more prisoners would just fill the vacancies, costs would go up, and things wouldn't look much better. Only after the backlogs have been absorbed, would there be much visible effect.

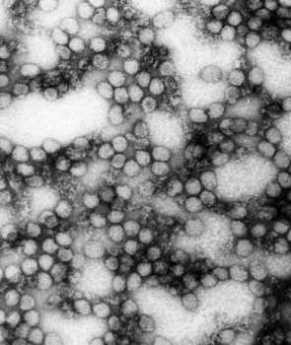

Germantown Nurses the Yellow Fever, 1793

|

| Yellow Fever, Phila |

The French Revolution continued from 1789 to 1799 and created the opportunity for a second revolution in the New World which a second overstretched European country would lose. The slaves of Haiti just about exterminated the white settlers, except for the few who escaped, taking Yellow Fever and Dengue with them. Both diseases are mosquito-borne, so they flare up in the summer and die down in the winter, although the Philadelphians who welcomed the exiles didn't know that. Yellow Fever in Philadelphia was bad in 1793, came back annually for three more years, and flared up once again in 1798. It could be easily observed to be more frequent in the lowlands, absent in the hills. Seasonal, it reached a peak in October, disappeared after the first frost. In the early fall, people died a horrible yellow death, jaundiced and bilious.

|

| Dr. Rush |

The Yellow Fever epidemic had a profound effect on many things. It was one of the major reasons the nation's capital did not remain in Philadelphia. It made the reputation of Dr. Benjamin Rush who announced a highly unfortunate treatment -- bleeding the victims -- thus provoking numerous anti-scientific medical doctrines based on the relative superiority of doing nothing at all. In Latin, Galen had capsulized the doctrine of Hippocrates in the "Epidemics" as premium non-nocere ("At least do no harm.") It took a full century for American scientific medicine to recover from this blow to its reputation. Whatever criticism Rush may deserve for his Yellow Fever blunder, it definitely is not true that he was a scientific lemon. Medical students are regularly surprised to learn that he is the physician who first identified and described the tropical disease of Dengue, or "break-bone fever", which was a somewhat less noticed feature among the Haiti exiles in Philadelphia. In still other scientific circles, Benjamin Rush is often referred to as the "Father of American Psychiatry". He was one of the founders of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest medical society in North America. Medical colleagues who today scoff at the yellow fever episode seem to forget that Rush stayed behind to tend the sick during a devastating epidemic, while many of his more cautious colleagues fled for their lives. An unhesitating signer of the Declaration of Independence, whatever Rush did, he did courageously. Non-academic physicians have sarcastically referred to this episode ever since, as proving that "some people" think it is "better to publish than to perish".

One very good non-medical thing the Yellow Fever epidemic accomplished was to put an abrupt end to the torch-light parades of window-breaking rioters agitating, with Jefferson's approval, for an American version of the guillotine and the terror. Federalists like John Adams and William Bingham never forgave Jefferson or his admirers for this, so the class warfare movement might likely have got much worse if everyone had not suddenly dropped tools, and headed for the hilly safety of Germantown.

The President of the new republic, George Washington, was in Mt. Vernon in the summer of 1793, wondering what to do about the Yellow Fever epidemic, and particularly uncertain what the Constitution empowered him to do. He finally decided to rent rooms in Germantown and called a cabinet meeting there. His first rooms were rented from Frederick Herman, a pastor of the Reformed Church and teacher at the Union School, although he later moved to 5442 Germantown Ave, the home of Col. Franks. Jefferson chose to room at the King of Prussia Tavern.

During this time, Germantown was the seat of the nation's government. As was fervently hoped for, the cases of yellow fever stopped appearing in late October, and eventually, it seemed safe to convene Congress in Philadelphia as originally scheduled, on December 2.

Although Germantown was badly shaken by the experience, it was a heady experience to be the nation's capital. Meanwhile, a great many rich, powerful and important people had come to see what a nice place it was. Germantown then entered the second period of growth and flourishing. Walking around Germantown today is like wandering through the ruins of the Roman forum, silently tolerant of visitors who would have never dared approach it in its heyday.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Rush: A Discourse delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Thomas A. Horrocks ASIN: B0006FCBXS | Amazon |

| Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793: J.H. Powell ISBN-13: 978-1436715881 | Amazon |

| Germantown and the Germans: An Exhibition from the Collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia: Edwin, II Wolf ISBN-13: 978-0914076728 | Amazon |

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

College of Physicians of Philadelphia

|

| College of Physicians of Philadelphia |

The College of Physicians of Philadelphia is the oldest medical organization in America, or even the Western Hemisphere, having been founded in 1787, the year of the Constitutional Convention. The CPP, located on 22nd Street near Market, is not to be confused with the American College of Physicians (a much more recent organization, formed in 1923 and located at Fifth and Arch Streets). The term "Physician" was then much more specific, and Philip Syng Physick, now known as the father of American Surgery was not considered eligible for membership because he was a surgeon, not a physician.

The general idea of the founding of the College seems to have been to focus on the physicians who had attended medical school (usually in Edinburgh), as distinguished from the general run of a physician at the time, who had merely served an apprenticeship. The first medical school, at the University of Pennsylvania (then at Ninth and Walnut Streets, but now at 36th and Spruce) caused the College of Physicians to turn away from pedagogy to the direction of setting standards and providing a forum for the "better sort" of the profession to be self-governing. At one point, there was even a real possibility that the College of Physicians of Philadelphia would become the credentialing agency for the whole country, but licensing took the direction of state boards during the Nineteenth Century. Every book and journal must have a Library of Congress number. The Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia has a Library of Congress number, all right. Number one. Jonathan Rhoads, the giant of 20th Century surgery and the only person to be president of the College twice, once remarked that being first may not be terribly important in the greater scheme of things, but -- it's awfully hard to imitate.

The College was a very strong guiding force in the development of a system of medical ethics for the profession. A curious false turn was taken in the direction of Lambda Chi, a secret society of physicians for the purpose of invisibly policing medical conduct, but the College soon recognized this was the wrong direction to take, and eventually, it assumed the lead in forming the American Medical Association in 1848. The portrait of Chapman, the first President of the AMA, hangs above the mantle in the fellows' reception room, the original minutes and rolls of the delegates are found in the library. Half a dozen presidents of the College were also presidents of the AMA, but for some curious reason the College never became the local branch of the AMA, reserving that for the State and Pennsylvania County Medical Societies.

Every year a number of the most distinguished physicians in the world address the College, and an annual lecture by a Nobel Prize winner has been established. The College had the largest medical library in the country until recently, and it is still one of the largest. The present building is a Carnegie Library, in a sense. Andrew Carnegie was a patient of S. Weir Mitchell at the time Mitchell was president of the College and donated a large sum for a new building. The present elegant marble and the walnut-paneled structure was built in 1905, fairly recent by Philadelphia standards but nevertheless a national landmark.

With all this dignity, history and tradition, it likely comes as a surprise to learn that the College building has sixty thousand paid visitors each year. The source of this popularity is a combination of medical exhibits for the public, and the Mutter Museum. In the late Nineteenth Century Thomas Dent Mutter gave his large personal collection of anatomical specimens to the College for a museum in the style of the medieval European medical schools, where the students could learn from specimens on display because anatomical dissection was discouraged if not forbidden, and Kodachrome slides had not been invented. Mutter's collection is a combination of believe-it-or-not "freaks", anthropological studies of human variations, and a museum of medical history. The former curator, Gretchen Worden, has produced an illustrated book of the exhibits which quickly sold out and must be reprinted, and a yearly illustrated calendar which is quite popular. The doctors are a little bemused by the popularity of this material with the public, but tolerant.

Among the odd features of this collection is the brain of Sir William Osler, the giant of modern medical education. Osler belonged to a club of people who had such a high opinion of their own genius they pledged to donate their brains after death to the collection of specimens, in the hope that eventually science would be able to determine the anatomical source of their talents. Most people today are a little staggered at the arrogance of such an idea, so widely at variance with the concept that all men are created equal. Albert Einstein is another acknowledged genius whose brain is still floating in a pickle jar, waiting for its unique properties to be discerned. Presumably, time will eventually tell whether even the greatest intellects suffer from unconquerable hubris, or whether the envious rest of us must adapt to the consensus of political correctness, just to avoid facing the reality of our own inferiority.

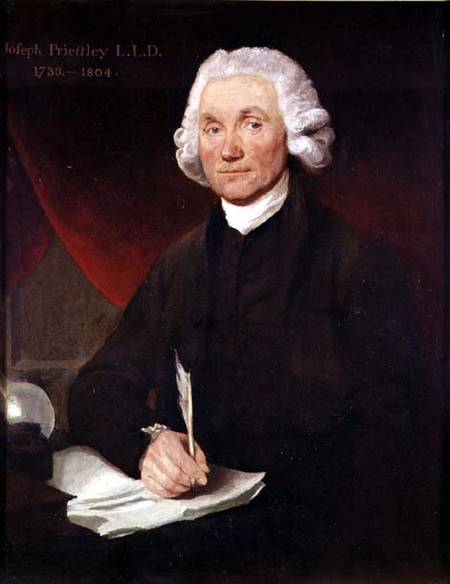

Joseph Priestley, Shaker and Mover

|

| Priestley |

Joseph Priestley, sometimes also spelled Priestly, is surely one of the more undeservedly neglected men of history. He has been called, with justice, the Father of the Science of Chemistry. He might also be called with equal justice, the father of the First Unitarian Church . The First Unitarian Church of Philadelphia, at 21st and Walnut, is the first and oldest Unitarian church and was indeed started at the urging of Priestley, whose principal residence was in Northumberland PA, at the confluence of the West and North Branches of the Susquehanna. Priestly wrote a scholarly work on the teachings of Jesus, which so captivated Thomas Jefferson that Jefferson wrote him the outline of another book that needed writing. Apparently, Priestley didn't have time, so in 1803 Jefferson wrote it himself, in the four languages he was fluent in, English, French, Latin, and Greek. Although those were simpler times, there have been few if any others who have told a President of the United States that he was just too busy to respond to a presidential request, particularly when the President could then find he had time to do it himself.

Priestley's theological teachings were based on scientific reasoning. They were highly controversial views, to say the least. He rejected the concept of a Trinity (he was a Calvinist minister, mind you), the divinity of Christ, and the immortality of the soul. Essentially, he rejected the concept of an immortal soul on the reasoning that perceptions and thought were functions of material structures in the human brain (Edmund O. Wilson's idea of Consilience is largely similar), and therefore will not outlive the cerebral tissue which produced them. In 1791, mobs burned his house in Birmingham, England, his patronage was revoked, and he hastily emigrated to Philadelphia. It isn't hard to see why these ideas were particularly unpopular with the Anglican church, which is probably the main reason England made him into a non-person, and his scientific ideas were denigrated as the product of other people.

That's too bad because he really was a scientist of immense importance. As a young man, he encountered Benjamin Franklin in England and was certainly a man after Franklin's heart. He noticed funny things about gases that rose from swamps and over mercury salts, and Franklin encouraged him to systematize and analyze his observations into theory. Although he called it anti-phlogiston, he had discovered oxygen. And then hydrogen, and nitrous oxide, and sulfur dioxide, and hydrochloric acid. Priestley really was the first organized and coherent scientific chemist, the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, Lavoisier, and Priestley became scientific friends, and enthusiastically exchanged ideas and observations, eventually leading to Lavoisier's fundamental principle: Matter is neither created nor destroyed, it only changes its form. In the end, it made no difference; Priestly had offended some pretty large religions, and nothing he did in chemistry was going to get much attention. Perceiving the value of the land at the confluence of rivers, he made his home for the last ten years of his life in Northumberland, Pennsylvania, now three hours drive Northwest, somehow managing to maintain an active scientific, political and theological influence worldwide. Visiting this rather sumptuous estate in a little river town is well worth a tourist visit. He died in 1804, just after his friend and kindred-religionist Thomas Jefferson became President of the United States.

Priestley's life can be summarized in one of his own most quoted remarks. "In completing one discovery we never fail to get an imperfect knowledge of others of which we could have no idea before so that we cannot solve one doubt without creating several new ones."

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

Abortion

The official position of the Pennsylvania Medical Society on the topic of abortion is, we have no position on abortion. I ought to know because I was the author of this position, proposed at a moment when the PA Medical House of Delegates was obviously going nowhere. After two hours of angry debate, we had to stop before we split into two warring medical societies. The Pennsylvania delegation to the AMA was then obliged to hold the same no-position on a national level. As I recall, our position was likewise greeted by the AMA House of Delegates with great relief, and word quickly circulated in the corridors that Pennsylvania had a position everyone could endorse for the good of the organization. For several years, this no-position position was widely referred to whenever the topic threatened to arise. It almost invariably stopped the discussion in its tracks, as it was intended to do. In going back over the minutes, it would appear the AMA never actually voted to adopt a no-position motion, a discovery that surprised but did not change the basic determination to let the rest of the nation settle this. We were going to stay out of it.

|

| Roe vs. Wade |

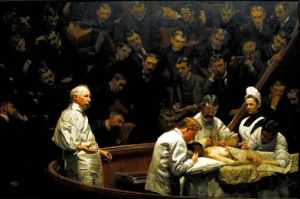

Because, one hundred forty years earlier, we started it. If you actually read Justice Blackmun's opinion for the majority in Roe v. Wade, as very few agitated proponents seem to have done, the original medical origin is clearly laid out. Blackmun had been a lawyer for the Mayo Clinic before his appointment to the Supreme Court, acquiring unusual medical resources and experiences for a lawyer. Now prepare for a logical leap, to the The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins masterpiece painting of Philadelphia's pre-eminent surgeon in a black frock coat, holding a dripping crimson scalpel in his bare hand, encapsulates the original situation. Note carefully that anesthesia is being given to the patient, but the surgeon is not wearing a cap, mask, gown, or rubber gloves.

|

| Gross Clinic |

In 1850 medical science had progressed into a forty-year time window when anesthesia made abortions painless, but Pasteur had still not identified bacteria, and Lister had not devised a way to cope with them. Abortions, common in ancient Greece but forbidden by Hippocrates, suddenly were widely demanded by 19th Century women in a situation when their judgment was vulnerable. Abortions were easy to do, all right, but women died like flies from the resulting infections, and the American Medical Association was distraught about it. The Oath of Hippocrates was brought forward to emphasize its prohibition of abortion, and the performance was made unethical for a member of the Association, sufficient cause to warrant expulsion. When that proved inadequate, the delegates agreed to go to their local state legislatures and seek legislation prohibiting the performance of abortion by anyone, member or non-member of the Association. These laws were quickly passed, and it was the Texas version which was overturned by Roe v. Wade as an unconstitutional denial of privacy. Roe was a pseudonym for the patient, and Wade was then Attorney General of Texas, the officer charged with enforcing Texas law. By 1900 abortions became both easy and safe for the mother, and by 1911 the AMA had reversed its position. The scientific surgical situation is well illustrated by a later famous painting about Philadelphia surgery by Thomas Eakins, the Agnew Clinic, in which the surgical team is portrayed in its modern costume of sterile gowns and rubber gloves. But it didn't matter since by that time various churches had hardened their doctrines. Religious leaders and their constituent politicians simply no longer cared what the medical profession thought about it. For at least the following century, ideological combatants were plainly only interested in whether physician opinion might advance one side or the other of their argument with useful official statements. Our real position, if anyone cares, is that we started out seeking protection for the safety of the mother, but the issue got twisted by others into disputes about the welfare of the unborn fetus.

|

| Agnew Clinic |

Since this is the case, there plainly may be a reason for state legislatures to reconsider the state laws they passed in the 19th Century, during that forty-year window of time when the scientific facts were in transition. But when a leap is made by the appointed referees of the federal government to overturn state laws, even about a basically medical issue, there has to be some legal reason to intervene; a medical reason somehow doesn't count. Justice Blackmun's discovery of an unnoticed right to "privacy" in the Constitution, where the word does not appear, is just too hard for us non-lawyers to deal with. Suppose we leave the fine points of the Bill of Rights to those constitutional lawyers. What's at stake here, among other things, of course, is whether the Federal Courts are justified in overturning well-intentioned state laws which had served well for at least fifty years -- simply out of impatience with the sluggishness and political timidness of state legislatures to revise obsolete laws. That's unbalancing the Constitution for a comparatively minor cause. Even major cause is something we have agreed to adjust in other ways, by amendment, not judicial opinion. And that's my opinion, having comparatively little to do with abortion.

Old Blockley (P.G.H.)

|

| Old Blockley |

For a long time, the Philadelphia General Hospital was the largest hospital in town, even growing briefly to seven thousand patients during the Civil War, but leveling off at about three thousand at the beginning of the Twentieth Century. At the end of World War II, it had shrunk to about 1500 beds, but it was Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 which finally did it in. By 1977 it was costing the City of Philadelphia about five million dollars a year beyond its revenues to run the place with only 300 patients, while the running expenses of the local private hospitals were actually less, per patient. Titles XVIII(Medicare) and XVIV(Medicaid) of the Social Security act constituted Lyndon Johnson's Great Society, and in effect they made every patient at PGH resemble a walking government check in the mind of hospital administrators. The local hospital association made the argument to the Mayor Rizzo that everybody would be better off if the hospital closed and those government checks were directed to the local voluntary institutions. After a few years, the federal government inevitably squeezed the generosity out of the bargain they would of course now like to abandon. But that's the way it goes. PGH is gone and it isn't coming back. The eighteen acres in Blockley Township, now West Philadelphia, were given to the University of Pennsylvania next door, and gigantic amounts of federal money were contributed to the building of skyscrapers replacements for the original PGH. Ironically, the two hundred children's beds now on the location are fewer in numbers than the three hundred adults once considered too uneconomically few to maintain, and the cost per day of hospitalization is roughly ten times the PGH cost which had been described as unsupportable. The rest of the real estate is built up with buildings involved in medical research, which is also an activity dedicated to working for its own extinction. Discovering a cheap cure for cancer would quickly create a need to fill the vacancies with something else. No one regrets this system of creative destruction, but everyone should regret the diminution of the spirit of local philanthropy which underlay it.

PGH was one of a dozen or so big-city charity hospitals, like Bellevue in New York, Charity in New Orleans, or Cook County Hospital in Chicago. Of these hospitals, PGH had surely been the best, and at the turn of the Twentieth Century a Mayor's commission issued a report about the place which began, "Philadelphia can surely be proud...." Having worked in Bellevue and having visited most of the rest, I can testify that was likely true. When PGH was finally torn down, the walls and floors had such substantial construction that changing the wiring and plumbing to some other purpose had become almost impossible. The PGH nurses were famous for running. Although the alcoholic and drug-addicted patients might be called the dregs of society, the alacrity of the student nurses in running them bedpans or answering other calls, was spectacular to watch. When a doctor came on the floor, they jumped to their feet and were usually ready with the patient's charts, unmasked. Unlike Bellevue, where the floors were creaky and wooden, the open wards at PGH were spacious, clean, well maintained and equipped. At Bellevue, the forty-bed wards were crowded with sixty or seventy patients, so close together you could almost roll from one end of the room to the other without touching the floor. I can remember seeing one seventeen-year-old Bellevue student nurse tending such award at night alone, the intern sharpening needles, and the medical resident developing electrocardiograms in the darkroom. None of this would have seemed acceptable at PGH.

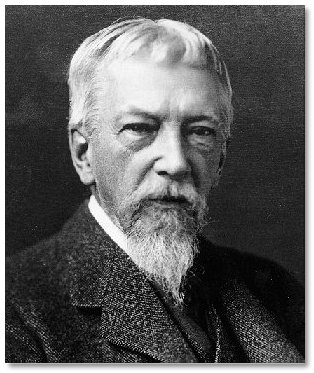

|

| Dr. William Osler |

Old Blockley was the place where modern systems of medical education originated. Up until William Osler came to Philadelphia, medical education mostly consisted of attending eight hours of lectures a day. Osler had an electrifying personality and wandered among the sick at PGH with a train of students following him. He is much quoted, and once suggested his obituary ought to read, "Here lies the man who took the students into the wards." A somewhat more elegant statement of the value of the practical experience was included in his dedication speech at the Boston Library: "To treat patients without books is to sail an uncharted sea. To read books without seeing patients is never to go to sea at all. Osler was somewhat underappreciated during his time in Philadelphia and went on to found the medical school at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore. Nevertheless, the main reason he later left John Hopkins and went to Oxford was his dismay at the adoption of the "full-time" system, which is to say the faculty stopped having a private practice of their own to act as a gold standard for their research and teaching. When all is said and done, there are some areas of discomfort in the transition of students from observers to actors. The PGH system of learning surgery was commonly reduced to a slogan, "See one, do one, teach one,"; things have progressed to the point where it is probably right for the public to insist on greater supervision and control than the old almshouse provided.

The disappearance of old Blockley ended a controversy, or even something of a mystery, about which was the oldest hospital in America, PGH or the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce. There had been an infirmary in Old almshouse at Eleventh Street, and there is no doubt the almshouse was there first. PGH grew out of the almshouse. However, there were many comments at the time of the founding of the Pennsylvania Hospital that it was now the first; that's a strange thing to say when the almshouse was three blocks away. Social historians need to look into the mindset of colonial America, which seems to have included the distinction between the worthy poor and the unworthy poor. Somehow, the founding principal of the Pennsylvania Hospital was to get people back to work who were capable of productive work, possibly even paying for itself in that way. In their minds, apparently just giving solace and help to those who were down and out was not quite the same thing.

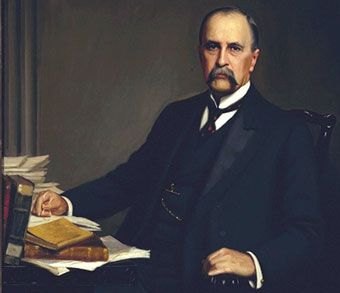

A Toast To Silas Weir Mitchell, MD

|

| Silas Weir Mitchell |

Silas Weir Mitchell lived to be an old man during the Nineteenth Century when it was unusual to get very old. He was an important part of both the Philadelphia medical scene and the literary one. He became known as the Father of American Neurology as a published studies of nerve injuries caused by the Civil War. He published about 150 scientific papers, including famous investigations of the neurological effects of rattlesnake venom. His most famous medical treatment was the "rest cure" for hysteria, while his most enduring scientific discovery was the phenomenon of causalgia. He despised Freud, and psychonanalysis. No doubt the feeling was mutual, but the passage of time has tended to favor Mitchell more than Freud. The central role of sex is the essence of Freud's viewpoint, while Mitchell is summarized in the remark that, "those who do not know sick women, do not know women."Struggling medical students can take heart from the well-documented fact that Mitchell applied to the Pennsylvania Hospital for an internship, and was rejected. Upset by the experience, he toured Europe for a year and applied again. He was again rejected. He later applied for the faculty at Jefferson and was rejected, but his reaction to that was one of rage and vengeance. Just what these two episodes out of Philadelphia medical politics really mean, remains to be clarified by Mitchell's biographers.

|

| Franklin Inn |

Mitchell's second career was literary, publishing 12 novels and 5 books of poetry. He is honored as the founder of the Franklin Inn Club, for century home to every important literary figure in Philadelphia. It is striking that he selected Benjamin Franklin as the guiding star of the Inn since Franklin similarly was eminent in both science and culture, and an ornament to conversation and society. In a pacifist Quaker City, both men approved of combat, and his novel about Hugh Wynne stresses that his hero was a "Free Quaker, meaning one who fought in the Revolution. Because of his strong Republican views, he was never made a professor at the local medical school.

|

| College of Physicians |

Mitchell's patient Andrew Carnegie donated the funds to build a new building for the College of Physicians when Mitchell was its President. When Mitchell was president of the Franklin Inn, Carnegie wrote him, asking for suggestions about donating a small sum, say five or ten million, and asking where it should go. That was the Inn's big chance, all right, but somehow it failed the test. Mitchell suggested that the money be given to raise the salaries of college professors, thus perhaps suggesting that this veteran of many academic revolts did eventually soften his views.

Eakins and Doctors

|

| The Gross Clinic |

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture.

Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition.

S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work.

In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

|

| Operating Amphitheater |

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing.

That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies.

The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer.

Emperor's Doctor

|

| Kitamura |

As told by one of his fellow interns who is now a very old man, Kitamura was one of the best interns the Pennsylvania Hospital ever had; diligent, dependable, intelligent and infinitely polite. He married one of the hospital's nurses, and they tended to keep to themselves, especially in 1941, as war clouds began to gather. About two months before Pearl Harbor, both of them mysteriously disappeared. Kimura's wife later wrote one of her friends that they were in Japan. After the war, it was learned that she had been placed in a concentration camp as an enemy alien, and when released, had divorced him.

Still later, it was learned that Kimura had a distinguished medical career in Japan. He kept up a minimal sort of correspondence with his old intern pals, inviting them to visit if they were ever in Japan.

In 1985 one of them did so, going to the largest hospital in Tokyo to inquire. Great silence ensued; unfortunately, the revered and distinguished physician had recently died. You knew, of course, that he was the Emperor's personal physician.

Discipline for the Disciple

|

I.S.Ravdin was President Eisenhower's surgeon; Chick Koop was President Reagan's Surgeon General. Both of them were overshadowed by Jonathan Rhoads. Even in a physical sense, this was true. Rhoads was a foot taller than almost anyone. Big bones, too.

During the Second World War, Ravdin led almost every doctor in the University of Pennsylvania off to some military hospital unit or other, and in fact, the 900-bed hospital in Philadelphia was left with only two surgeons, Koop and Rhoads, ineligible for military service because of previous tuberculosis. Koop was a first-year resident in training, so for practical purposes, Rhoads was the only surgeon. Even after eliminating purely elective or optional surgery, the workload was staggering, and the number of operations was prodigious.

Rhoads devised a system. The young trainee, Koop, would do the time-consuming work of opening the belly wall and Rhoads would then do the internal surgery, following which Koop would close the wound while Rhoads was operating on another patient. As Koop told the story at Rhoads' 90th birthday celebration, one day a patient was to have his gall bladder removed. Rhoads told him to open the wound, first, the skin, then the fascial layer, then the peritoneum, while he was finishing up with another patient in another room. At that point, Rhoads felt he would be able to come in and remove the gall bladder. Most gall blabbers are firmly attached to the nearby liver, and must be shaved loose before it is possible to put a clamp around the base to remove them.

On this day, two things were different. Rhoads was delayed in the other room because of some complication, and Koop was just standing around waiting. The other thing that was different was that this particular gall bladder was not attached to the liver at all, but was just flopping around in the belly. When Rhoads continued to be delayed, Koop just went ahead and clipped off the gall bladder; more time elapsed. So he carefully sewed up the peritoneal layer, then the fascial layer, then the skin, stitch by stitch. He was standing there pretty pleased with himself when the doors finally banged open and Rhoads came charging into the operating room.

Koop offered some explanation in a faltering way, but Rhoads did not say a word. A large elbow on a huge arm silently but forcefully brushed Koop off to one side in a single movement. Rhoads then took out each stitch in the skin, then the stitches in the fascia, then the stitches in the peritoneum. He peered into the cavity, inspected the former bed of the gall bladder. Finding things in good order, he then resutured the peritoneum, then the fascia, then the skin. Without a word, he then strode from the room, leaving the future Surgeon General never to forget the lesson he had been taught.

Goat Head Merchant

|

| Bellvue Hospital |

In 1948, one of the Internet physicians at Bellevue Hospital contracted tuberculosis. The senior medical students at Columbia were asked to volunteer to take his place, and for a month I did so. Since I knew I was soon going to Philadelphia to the Internet at the Pennsylvania Hospital, my interest was particularly taken by an old Bowery bum who was talking about untaxed liquor. In New York at that time, it was common for Skid Row denizens to drink the wood alcohol in Sterno, called "squeeze" because it could be extracted from the waxy contents of a Sterno can by wrapping it in cheesecloth or a handkerchief and squeezing out the juice. Another favorite was "Smoke", which was typically a mixture of automobile radiator fluid and other sundry handy ingredients. My new best friend at Bellevue was just recovering from the effects of such recreation, and was in a mood of "never again". He observed that "When I get out of the Bell View, I'm going to get on a bus and go down to Philly. They've got a drink there called Goat Head, and, man, is it ever smooth."

The Chief Resident of the Pennsylvania Hospital was happy to tell me what Goat Head was. It was bootleg liquor, made in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey. Bags of cane sugar were fermented and distilled through coils of copper tubing, obtained from old hot-water heaters. The smooth stuff that so intrigued the bums of Bellevue was what was otherwise known as "White Lightning". It was then sold in the alleys near South Street by "Goat Head Merchants", who carried a suitcase full of small bottles, sold for about 25 cents a bottle. They say that during the Depression, Goat Head was sold out of an open bucket, at 10 cents a dipperful. One of the Goat Head Merchants used the Accident Room of the hospital as his family doctor, let us call him Walter Apple.

One day, Walter had a heart attack and was brought in on a stretcher, in considerable pain. I had just completed an electrocardiogram on him, when the pain disappeared. A few weeks later, he had completely recovered and was going home. Every time I came anywhere near him, he announced to everyone in the vicinity that I was the best doctor in the world, having cured his heart attack by giving him the "wire treatment".

As he gathered up his belongings to go home, he apologized that he was not going to be able to pay his bill. He had once known Dillinger and all those other big shots wore a diamond stick-pin and drove a Duesenberg car. But now he was broke.

But grateful, too. So, if ever there came a time when I encountered someone unpleasant, who needed "pushing' around" -- just you call on Walter Apple, and Walter would be glad to pay off his debt.

Lin

Lindley B. Reagan, M.D.

July 16, 1918 -- September 10, 1995

|

| Lindley B. Reagan, M.D |

The first and oldest hospital in America, the Pennsylvania Hospital at 8th and Spruce Streets, always had a strong Quaker flavor but a unique medical tradition as well. Since it was the only American hospital for decades, later becoming the home hospital of the first medical school in the country, it impressed its ideals and traditions on the whole of American medicine. However, it imposed so many difficult demands on its trainees that a century or more of an evolving profession simply moved away from copying it. It was, in 1960, the last hospital in the country to begin paying its resident physicians anything at all, one of the last privately controlled American hospital to adopt a billing and accounting department, and one of the last if not the last to regard a handful of private beds as merely a convenience for the patients of the staff physicians. In 1970 its method of maintaining inventory was to notice that the supplies on the shelf were running low, and ordering some more. It was founded in Benjamin Franklin's words, for the "sick poor, and if there is room, for those who can pay," and could only survive into the late 20th Century through private donations and the freely contributed services of the doctors, student nurses and administration. No amount of money could induce people to work as hard as they worked. You might say this was the only aspect of Medieval monasteries which Philadelphia Quakers thought worthy of imitating.

Somewhere in this set of ideas was the treasured concept of a rotating internship, preferably two years long, prior to entering specialty training through a residency. In 19th Century Vienna, it was a matter of rule that an intern was just that, physically confined within the walls for the term of service, and a resident was just that, someone who lived on the campus. The Pennsylvania Hospital had no such rule, but since it paid the doctors nothing for five or six years of eighty-hour weeks, their poverty forced them to satisfy the Viennese rules by default. Entertainment was bridge or poker in the intern quarters, conversational chit-chat was a description of bizarre cases or peculiar patients, a weekend "off-call" was a good time to catch up on correspondence. There were student nurses around, of course, but the matron was a pretty no-nonsense chaperon. Every class of interns contained one or two millionaires by inheritance, but peer pressure made them nearly indistinguishable in the daily routines. Aristocrats' main value to the resident physician community was their access to the ruling families in the city, and hence to the governance of the hospital, in case governance should occasionally abuse the vulnerability of the trainees.

I find in retirement that most of my colleagues are now willing to tell stories of the "old days" which they were unwilling to tell at the time. Over several glasses of the finest single-malt in a walnut-paneled club, one such story recently surfaced. It concerned Lin.

Lin was a member of an old Quaker family, surprising everybody during the Second World War by volunteering as a junior physician in the Navy. He was assigned to a marine regiment in the Pacific Theater and went through some of the most murderous fightings on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. Our grapevine reported that the enlisted Marines in his outfit absolutely worshipped him, and I easily believe there was a lot of quiet heroism behind that gossip. He told me he had decided to become an internist while in the Pacific, but somehow only a surgical residency was available when the War was over, so he took it. He was probably the best internist on the staff, and it showed in his conduct of surgery, where it sometimes matters more what you decide to cut than what you cut. He always looked exhausted, but never hesitated to drive himself another hour when the situation demanded it. One day, he had to excuse himself from an operation, an almost unheard-of event, and testing his own urine, found it loaded with sugar. So, the soft-spoken Quaker internist who was primarily doing surgery had to add the burden of insulin injections to his load. If he ever complained about that or any other thing, no one could remember hearing it.

At about the third glass of single malt, the story came out. My old friend, like the rest of us, had to spend a year as a surgical intern during the two-year rotating internship; he hated surgery and didn't mind telling the world. At the moment in question, he was the assistant at some neck surgery, with Lin performing the actual surgery. He was told to take a long pair of scissors and cut off the excess strands of sutures after Lin tied the knots; that was known as trimming the ligatures. They were working deep in the crevices of the patient's neck. Lin held up the loose ends of the knot and ordered, "Cut". My friend inserted the long scissors into the hole and snipped -- accidentally cutting right through the jugular vein.

As would be expected, a fountain of blood came up out of the hole, and Lin stopped it by putting his thumb on the cut ends of the vein. "Well," said Lin, "I guess we'll have to fix that." And did.

With tears in his eyes, my octogenarian friend cried out to the startled clubroom. "God bless you. God bless you, Lin."