Related Topics

Outlaws: Crime in Philadelphia

Even the criminals, the courts and the prisons of this town have a Philadelphia distinctiveness. The underworld has its own version of history.

Philadelphia Medicine

The first hospital, the first medical school, the first medical society, and abundant Civil War casualties, all combined to establish the most important medical center in the country. It's still the second largest industry in the city.

Medical Economics

Some Philadelphia physicians are contributors to current national debates on the financing of medical care.

Reminiscences

"The past is never dead. It's not even past." -- William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

Illicit Drugs are Eliminated in Philadelphia

It seems fair to say that America is nearly desperate to find a successful way to eliminate the illegal narcotic trade. We've had a war on drugs, which seems to have three components, all failures. We have an occupying army in Afghanistan where most heroin comes from. We've sprayed weed killers on Bolivia, Colombia, Mexico, and found various other ways to assist local narcotic agents in their efforts to break up the planting of cocaine in Latin America. We've got high-speed patrol boats and helicopter patrols around southern Florida. Spies of all sorts have been hired to infiltrate the distribution channels. We've spent other tons of money educating school children that experiments with chemical recreation are risky, immoral, dumb, whatever. Sly, naughty allusions to drugs with cute code names have been pretty well driven off the television, night club acts, and even glitzy cocktail parties in the advertising business. Ronald Reagan had a simple solution --"Lock 'em up" which led to the passage of national law, leap-frogging the trials of drug offenses ahead of all other criminal offenses. The consequence was that prisons filled up and overcrowded conditions became a scandal. It may cost more to send someone to jail than to send them to Harvard, but the situation seemed to require us to ignore the cost, get them off the street, bring this problem to an end. If any of this work, or if all of it collectively worked, it didn't work very well. This is a very big problem that seems to defy solution.

So, one of the desperate ideas put forward has been to decriminalize drugs. That is, stop making their sale and use illegal. Abundant drugs would become cheap, cheap prices would eliminate the drug dealers' profit, and lack of supply of pushers would cause the supply to dry up. That is, no one would bring the heroin from Afghanistan, or the cocaine from Bolivia -- because there was so much of it around that the profit disappeared. Wait a minute. Did you just say that no one would import expensive narcotic because we would already have so much cheap narcotic? Somehow, it isn't persuasive that decriminalizing drugs would eliminate addiction. So, what other methods can claim proven success?

|

| Conan Doyle |

Let's try Philadelphia's system, by which I mean Philadelphia from 1940 to 1960. I graduated from medical school in 1948, filled with instruction about how to recognize the signs of drug addiction, how to detoxify, what precautions you ought to take to keep the student nurses from stealing the ward morphine supply, how carefully you had to monitor the pharmacy and anesthesia departments. Our older instructors were full of anecdotes about how clever the addicts were in fooling the doctor, how they themselves had been tricked or almost tricked, medical friends they knew who got hooked. Bad business, and it's important that every new innocent doctor is warned about how prevalent and how deceptive it was. Just read detective novels by Conan Doyle, who was a physician, addict, or De Quincey confessing to being an opium eater, or Coleridge writing Kubla Khan while in a drug stupor.

|

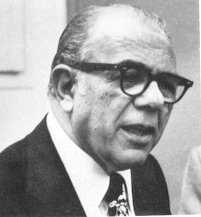

| Angelo Bruno |

So, my teaching and mentoring prepared me to believe that narcotic addiction was rampant before 1940. But when I came to Philadelphia I absolutely never encountered any of it, or at least until about 1970 when the Beatles and the Flower Children of California made it a deliciously tempting adventure. And I spent most mornings during that period doing teaching and charity work at Philadelphia General Hospital for thousands of indigents. If drug addiction had been anywhere in the city, it seems to me it would have been at PGH. We had thousands of cases of alcoholism, of tuberculosis, of syphilis in all its forms, suicides, homicides, bullet wounds, a prison ward full of manacled prisoners. But no drugs, nossir. It was a nice situation, and after a little while, you stop wondering about dogs that don't bark, and drug addicts that don't come in the accident room door. But a couple of decades later, when we had lines of heroin addicts waiting for their treatment, it all came back to us that we had experienced a remarkable absence of what was now quite common again. It had apparently been prevalent, it disappeared for twenty years, and then it came back. It now seems quite evident that we were enjoying a two-decade drug holiday, but what isn't so clear is what caused it. Whatever could have caused this remarkable temporary disappearance of illicit drugs?

Well, I don't know; and when you say that, you invite everybody to make some wild conjecture. So let me make my own well-ruminated guess, first. It seems worth investigating whether Angelo Bruno, the head of the mob, did it. It is a widely-held belief that Bruno hated the narcotics trade, and issued orders that there was to be none of it in his territory. It's quite possible that this was a purely business decision since there was plenty of money to be made from bootlegging and loan-sharking, whereas the narcotics business got you a lot of unwelcome heat from the police that would interfere with your profitability. By that reasoning, perhaps the war on drugs did have a beneficial effect, but it operated indirectly on the mob boss. Who was in a position to know what was going on in his territory, who was responsible, and what methods might be effective in discouraging the trade. But that explanation assumes the worst possible motives on Bruno's part.

Let's at least consider the possibility that Bruno had a large streak of decency in him, and really didn't like the narcotics racket even if it cost his organization money to get rid of it. And got his head blown off when greedier folk decided to eliminate this obstacle to their prosperity.

So, by that analysis, you have the Philadelphia System for a drug-free city. A system of proven effectiveness, when every other proposal has failed. Just pass the word that nobody will bother you in your loan-sharking and bootlegging, just so the distribution of illegal drugs stops completely. How you accomplish this is up to you.

Originally published: Thursday, January 11, 2007; most-recently modified: Tuesday, May 21, 2019