3 Volumes

Philadelphia Medicine

Several hundred essays on the history and peculiarities of Medicine in Philadelphia, where most of it started.

Health Reform: A Century of Health Care Reform

Although Bismarck started a national health plan, American attempts to reform healthcare began with the Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive era. Obamacare is just the latest episode.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Medical Economics

Some Philadelphia physicians are contributors to current national debates on the financing of medical care.

The Hospital That Ate Chicago (1)

|

| George Ross Fisher M.D III |

One evening in 1979 my visiting son, puzzled by health financing, asked me to explain. A decade of asking myself the same question led to the prompt reply that there seemed to be two central problems, both of them man-made. It's axiomatic in our family that man-made problems can have man-made solutions.

I believed you adequately understood health care financing if you understood the price reduction which hospitals give to subscribers of Blue Cross but not to subscribers of their competitors, and if you also understood the income tax dodge which the Federal government gives to salaried, but not to self-employed people who buy health insurance.

He asked how in the world these two subsidies were defended, and I told him. He then asked how these monopoly-inducing subsidies related to other weird quirks of health finance, and I told him that, too. He listened quietly for thirty minutes, and then exclaimed, "Wow. That's really the Hospital that Ate Chicago!"

So he went to bed, while I stayed up and wrote a short fancy for the New England Journal of Medicine, called, "The Hospital That Ate Chicago". Next morning I polished it a little and sent it off to the editor. Within a few days, it was accepted. Six weeks later it was in print.

The Nation's Future Health Profile

As the nation's health steadily improves, it's going to cause some problems of a social nature.

|

The most astoundingly good news about health is frightening, precisely because it is so astoundingly good. The average life expectancy of Americans has increased by three years during the last decade. That's right, we got thirteen years for the price of ten. Most of that improvement has come from taking daily aspirin tablets, or from taking the anti-cholesterol "statin" drugs, with a resulting decrease in the death rate from heart attacks and strokes by roughly 30%. It seems possible to hope for another three-year extension of lifespan in the next decade; when statin drugs lose their patent protection they will become a lot cheaper, and many more people will take them regularly. It seems churlish to emphasize the negatives of such a miracle, but unfortunately, it's questionable if our political and financial mechanisms can readjust to such an unprecedented commotion.

It could get much worse. The improvements in cancer treatment have lately been much slower and more expensive. If someone invented a treatment for malignancy which proved to be safe and cheap, we could get another five years, followed by still another five years as the patents run out and doctors get the hang of using it. Everybody could then reasonably expect to live to be ninety. What the Social Security and Medicare budgets would look like under those circumstances, must simply boggle the mind. If people mostly lived to be ninety, comparatively few of them would have much serious illness before they were sixty-five. The vast bulk of medical expense, for practical purposes almost all of it except obstetrics and psychiatry, would become Medicare expense. People would of course eventually die of something, and all of those terminal care costs would be Medicare costs. The government would, of course, begin to see what is happening and attempt to change the political arrangements for financing it, but that would be resisted bitterly, and it would be slow. What would not be slow would be the decision by employers that there is no sense in accepting financial responsibility for health costs which no longer have much impact on working people. Right now, health insurance amounts to forcing employees under the age of forty to subsidize the costs of other employees between the ages of forty to sixty-five. If that curve shifts to the point where everybody under sixty-five is essentially subsidizing people on Medicare, well, say goodbye to employer-based health insurance. Not later, right now. At the end of whatever calendar year, employers all wake up together and start a stampede out the door.

The first issue, of course, is not how to shift around the costs of medical care, but how to pay for staying alive. We can raise the age for beginning Social Security benefits, but that doesn't create money, it just shifts retirement cost from the government to the individual. What matters is that people must keep working longer, earning at least enough to support themselves; and that implies greater competition with younger people for available work. It may mean greater resistance to immigration, particularly illegal immigration, and a greater appreciation for frugal living. But shifts of twenty or thirty percent in the workforce within a decade probably cannot be accomplished, any more than they could be accomplished in Africa after the elimination of epidemic diarrhea and other tropical diseases. Genocide as an avocation does not seem very appealing, either. One suspects something similar happened to India with British colonial rule, better water and drains, and all that. And one has to speculate that something like that is being concealed in China, for all its vaunted growth in Gross Domestic Product. Selectively killing all girl babies at birth, and all boy babies after the first one seems more drastic than we would accept. But we must eventually do something, with the first step being a general appreciation of the problem. Overpopulation may or may not be the problem; the problem is too many healthy people past the traditional age of employment.

Somewhere in the writings of Aristotle is the maxim that all culture comes out of the wealthy classes because only the wealthy have time for it. Aristotle is obviously now out of date on that topic, because we can easily foresee a population of healthy old folks with time on their hands. Our cultural institutions seem painfully slow to recognize, not just their new customer base, but the potential creative base. Surely, Grandma Moses is not the only artistic self-promoter in her age group. And surely, adolescent love affairs are not the only topic capable of attracting a mass audience. Improved cataract extractions, better hearing aides, and outstanding dentistry will surely make it possible to foresee more grown-up tastes in music, the visual arts, and culinary skills. Once these old folks stop predicting their own impending deaths and face a twenty-five-year future on the golf course, a flowering transformation of the arts is safely predictable.

But that's not enough. Most people were not born with the talent to carry a musical tune or draw a straight line, and many of those who do have some talent feel the arts are trivial. For most people, the way to fill up a quarter of a century is to go back to work. I didn't say it was easy. There is just no feasible alternative.

Abortion

The official position of the Pennsylvania Medical Society on the topic of abortion is, we have no position on abortion. I ought to know because I was the author of this position, proposed at a moment when the PA Medical House of Delegates was obviously going nowhere. After two hours of angry debate, we had to stop before we split into two warring medical societies. The Pennsylvania delegation to the AMA was then obliged to hold the same no-position on a national level. As I recall, our position was likewise greeted by the AMA House of Delegates with great relief, and word quickly circulated in the corridors that Pennsylvania had a position everyone could endorse for the good of the organization. For several years, this no-position position was widely referred to whenever the topic threatened to arise. It almost invariably stopped the discussion in its tracks, as it was intended to do. In going back over the minutes, it would appear the AMA never actually voted to adopt a no-position motion, a discovery that surprised but did not change the basic determination to let the rest of the nation settle this. We were going to stay out of it.

|

| Roe vs. Wade |

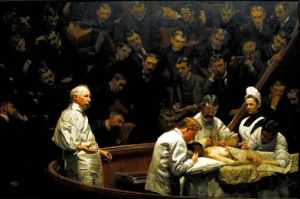

Because, one hundred forty years earlier, we started it. If you actually read Justice Blackmun's opinion for the majority in Roe v. Wade, as very few agitated proponents seem to have done, the original medical origin is clearly laid out. Blackmun had been a lawyer for the Mayo Clinic before his appointment to the Supreme Court, acquiring unusual medical resources and experiences for a lawyer. Now prepare for a logical leap, to the The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins masterpiece painting of Philadelphia's pre-eminent surgeon in a black frock coat, holding a dripping crimson scalpel in his bare hand, encapsulates the original situation. Note carefully that anesthesia is being given to the patient, but the surgeon is not wearing a cap, mask, gown, or rubber gloves.

|

| Gross Clinic |

In 1850 medical science had progressed into a forty-year time window when anesthesia made abortions painless, but Pasteur had still not identified bacteria, and Lister had not devised a way to cope with them. Abortions, common in ancient Greece but forbidden by Hippocrates, suddenly were widely demanded by 19th Century women in a situation when their judgment was vulnerable. Abortions were easy to do, all right, but women died like flies from the resulting infections, and the American Medical Association was distraught about it. The Oath of Hippocrates was brought forward to emphasize its prohibition of abortion, and the performance was made unethical for a member of the Association, sufficient cause to warrant expulsion. When that proved inadequate, the delegates agreed to go to their local state legislatures and seek legislation prohibiting the performance of abortion by anyone, member or non-member of the Association. These laws were quickly passed, and it was the Texas version which was overturned by Roe v. Wade as an unconstitutional denial of privacy. Roe was a pseudonym for the patient, and Wade was then Attorney General of Texas, the officer charged with enforcing Texas law. By 1900 abortions became both easy and safe for the mother, and by 1911 the AMA had reversed its position. The scientific surgical situation is well illustrated by a later famous painting about Philadelphia surgery by Thomas Eakins, the Agnew Clinic, in which the surgical team is portrayed in its modern costume of sterile gowns and rubber gloves. But it didn't matter since by that time various churches had hardened their doctrines. Religious leaders and their constituent politicians simply no longer cared what the medical profession thought about it. For at least the following century, ideological combatants were plainly only interested in whether physician opinion might advance one side or the other of their argument with useful official statements. Our real position, if anyone cares, is that we started out seeking protection for the safety of the mother, but the issue got twisted by others into disputes about the welfare of the unborn fetus.

|

| Agnew Clinic |

Since this is the case, there plainly may be a reason for state legislatures to reconsider the state laws they passed in the 19th Century, during that forty-year window of time when the scientific facts were in transition. But when a leap is made by the appointed referees of the federal government to overturn state laws, even about a basically medical issue, there has to be some legal reason to intervene; a medical reason somehow doesn't count. Justice Blackmun's discovery of an unnoticed right to "privacy" in the Constitution, where the word does not appear, is just too hard for us non-lawyers to deal with. Suppose we leave the fine points of the Bill of Rights to those constitutional lawyers. What's at stake here, among other things, of course, is whether the Federal Courts are justified in overturning well-intentioned state laws which had served well for at least fifty years -- simply out of impatience with the sluggishness and political timidness of state legislatures to revise obsolete laws. That's unbalancing the Constitution for a comparatively minor cause. Even major cause is something we have agreed to adjust in other ways, by amendment, not judicial opinion. And that's my opinion, having comparatively little to do with abortion.

Why Are Hospital Prices So High?

|

| Aspirin |

Cost analysts maintain it really does cost ten dollars to write a simple business letter, so maybe it's no surprise when hospitals charge ten dollars to administer an aspirin tablet.

But there's also another form of hospital overcharging. Mark-ups of prices of several hundred percents over audited costs are routine in hospital bills. These are not hidden cross-subsidies, either; they emerge on the yearly audit as multi-million dollar "losses", neatly balanced by "contractual allowances". Translated, these are discounts to insurance companies.

Why do hospitals raise prices, then turn around and discount them? Why do they overcharge, then call it a loss when they write it off?

It's an important question, because it results in confronting patients without insurance with much larger bills than the effective price to insured ones; patients who can't afford to pay are charged more than those who can.

The old-time system of hospital wards to care for people who couldn't pay have been replaced by collection departments and hospitals are very aggressive in pursuing the very people who can least afford to pay, and who are grossly overcharged in the first place.

Health savings accounts with high deductibles were conceived as a way for people to self insure but they have been thwarted by hospital overcharges. Since HSA deductibles are guaranteed, hospitals perpetuate their present largest source of loss -- unpaid deductibles. So why do hospitals continue to post abusively-high prices for patients without large-insurance-company coverage?

Until hospital officials come forward with a coherent defense of their practices, outsiders can only guess at motives. Start with the old legal approach of "Cui bono?" (Who might have a motive?) and divide the answers into those with a motive and those with the means. The line-up will then consist of hospitals, insurance companies, limited-license practitioners, and the state government. Limited licensees, acupuncturists and the like, surely must hate high-deductible health insurance because their fees mainly fall below the two or three thousand annual deductibles. Old-line health insurance companies also have plenty of motive to keep out competitors, fearing antitrust action if they get too obvious. That leaves the state government.

States have ample power over hospitals. Substantial annual payments are negotiated with hospitals for Medicaid services, charity care, and educational grants and subsidies. Tax exemptions are repeatedly challenged and re-negotiated, and overall non-profit corporations are entirely creations of the state legislature. So, unless it is a violation of federal law, the state government has the means to compel hospitals to do anything. Power, yes, but where is the incentive for states to wish for exorbitant hospital prices? Or confer monopoly status on certain insurance vendors by according them sweetheart discounts?

All current plans for "reforming" health care involve providing government-paid insurance to those without. Will the result be to permanently institutionalize the artificially-high public prices to be paid in full by the government? If so, you can well understand why hospitals support these "reforms".

So hospitals are no better than stores that mark up their prices and then loudly proclaim that they will give you a discount. 200% mark-up, 10% off; terrific.

Specialized Surgeons

|

| Regina E. Herzlinger |

Local attitudes always somewhat persist among migrants from home. What's distinctive about the Philadelphia diaspora is how unconscious most of them are about still carrying the hometown mark. Philadelphia leaves a prominent birthmark, but it's sort of back between your shoulder blades and you forget it's there. What occasions this observation is a Christmas call from a prominent California surgeon who was once my roommate, back in the days when residents were actually resident in the hospital. More than fifty years ago Bill Doane also served as best man at my wedding. Our conversation turned to clots in the lung, and he related a story. He had once fixed a hernia for a 22-year old girl in the days when it was customary to keep hernia cases in bed for a while. Getting out of bed for the first time, she coughed and turned blue, suddenly on the edge of death. Taken back to the operating room, her chest was opened, and Bill removed a clot which was essentially a cast of the blood vessels of one entire lung. As surgeons like to say, she then did very well.

One doctor can tell such a story to another doctor in four sentences, while lay people who overhear it miss the whole point. The fact is, not one surgeon in ten thousand today could carry this off. Nowadays we train thoracic surgeons to open the lungs; they never repair hernias. Conversely, we train hernia surgeons to fix a dozen hernias daily through a little telescope; they never open a patient's chest. So it is hard to imagine many contemporary surgeons who could recognize this disastrous complication of hernia repair, then fix it themselves in time to rescue the patient. Although this disheartening decline into repetitive super specialties has been forty years in the making, it has been recently popularized with the general public by Regina E. Herzlinger, a Harvard business professor. Writing books and speaking to businessmen groups, she has popularized the proposal to outsource the general hospital into what she calls "focused factories." She rightly characterizes the medical profession as reluctant. She's a nice person, and undoubtedly sincerely believes focused factories will save money, improve quality. But we must not let this idea take hold.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

Specialty hospitals have actually been given more than a fair trial. About a hundred years ago, the landscape was peppered with casualty hospitals, receiving hospitals, stomach hospitals, skin and cancer hospitals, lying-in hospitals, contagious disease hospitals, and a dozen other medical specialty boutiques. With a few notable exceptions, they all failed for the same reason. Sooner or later they found they could not adequately service their specialty without the backup of a full hospital service. Children's hospitals do thrive, but they have patients who are generally of the wrong physical size to fit adult hospital facilities and equipment. There are plenty of things to regret about general hospitals' design, but the inescapable fact is they all must have a very wide range of services to perform any mission, no matter how discrete. It would be still better if the doctors had an equally wide range of skills in their own heads, but the avalanche of innovation and lawsuits has forced sub-specialization, compartmentalizing, and narrowness of viewpoint. Circumstances have forced the profession to hunker down, but that trend must be resisted, not celebrated.

The instant and successful repair of pulmonary embolism make a dramatic illustration, but the reasons for broad medical training are more extensive than that. In the first place, it is much cheaper to use the generalist office than to bounce people to a gastroenterologist for heartburn, a psychiatrist for anxiety, and a dermatologist for pimples. The American employer community is desperate for a way to reduce its burden of employee health costs, and flocks back to their nurturing business schools for advice. They would do better to seek repeal of the tax dodges which tempted them into their present muddle, of course. But in any event, they must be persuaded to recall the disaster of managed care and at least, avoid meddling in hospital design.

That's the cost issue, where specialization surely raises costs. Constant repetition of the same procedure seems superior to first-time fumbling, although it is questionable how long it takes a well-trained surgeon to pick up a new procedure and do it well. But for this system to work, the referring physicians need to be more skillful, not less, in choosing a good one to refer to. There's just nothing like the experience of working for a few weeks in the specialty as a rotating intern, to tell you what to look for and what to avoid. If every doctor in a hospital is making a dozen internal referrals a day, the cumulative effect on the quality of the whole institution is dramatic -- when they have had sufficient past involvement in the specialties to which they now only refer patients. Some specialists will become popular and rich; others will sulk around unnoticed for a while, then go elsewhere. This process, of course, occurs everywhere; what's institutionally distinct is the culture underlying the standards for preferences.

We'll talk later about the Doane brothers of Bucks County, who were judged to be too handsome to hang. Right now, the point of this story can be summarized by the old Pennsylvania Hospital adage, that you must first be a good doctor before you can be a good specialist. Not only was the Pennsylvania Hospital the first in the nation. For sixty years it was the only hospital in the nation, and for decades after that, it was the only hospital in Pennsylvania. In medical history circles, it is said that the history of American medicine, is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

Medicare/Health Savings Accounts Legislation

New Health Insurance Reform Proposals

"SUPPLY SIDE" HEALTH INSURANCE REFORM a) reduced small-claims insurance costs b) reduced "moral hazard" overutilization costs c) compounded internal investment of reserves d) utilization of the now-wasted labor potential of young retirees It does not aim directly at the goal of reducing the number of uninsured, except on the principle that if something becomes cheaper, more people can afford it.

|

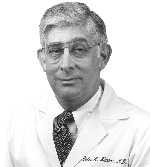

| Dr. Fisher |

1. HIGH DEDUCTIBLE. The annual deductible of health insurance should be high, in the range of $ 3000 per year. The main reason for a high deductible is to make health insurance premiums cheaper, especially for currently uninsured people. But high deductibles serve other important purposes. 80% of costs concentrate in the most expensive 20% of illness episodes, but these "big ticket" expenses generate far less than 80% of administrative costs. The cost of healthcare to society can be markedly reduced (at least 30%) by eliminating small-claims administrative costs, as well as the disproportionate "moral hazard" costs of minor illnesses. "Moral hazard" includes wasteful utilization of services and insensitivity to price, both deriving from interposing insurance "third parties" rather than paying the providers directly. Note: the advantages of deductibles are not present in "co-pay" features, which in fact increase administrative costs, particularly when a second, or coinsurance, a policy is employed to cover them.

2. COVER DEDUCTIBLE PORTION WITH MEDICAL SAVINGS ACCOUNT. Because high-deductible insurance may give poor people a financial barrier to access, the 2003 Law encourages linking high-deductible policies to a tax-sheltered Medical Savings Account, renamed Health Savings Accounts. Thus, although medical bills (up to the deductible threshold) require cash, reimbursement reserves are supplied by the individual's Account.

These reserves also create new and unexpected value, including portability between jobs, a more level playing field for tax preferences, a longer horizon for health coverage than traditional one-year policies, and neutrality of employers to individual employee health preferences. Although conventional health insurance could be paid for by credit or debit cards, it has somehow never been conventional to use them. Medical Savings Accounts, by contrast, commonly use credit cards, because they simplify record-keeping for the deductible.

What is the source of the money in Medical Savings Accounts? High-deductible premiums are roughly a third of conventional health insurance, depending on the individual's age. The remaining two-thirds go into the tax-deductible savings account. Current law permits additional contributions (out of pocket, but tax-exempt), scaled to the individual's age. If the account is mostly untouched by a healthy person for two years, it becomes increasingly difficult to exhaust it later because of a) its internal income generation, and b) the top limit on expenditures created by the insurance policy. For low-income individuals, funding might be publicly supported.

3. NOTICE THE TWO DIFFERING PROVIDER PAYMENT-METHODOLOGIES. The level of $3000 annual deductible was chosen as within the current band of outpatient-inpatient price separation and requires an inflation adjustment clause to keep it there. One of the chief advantages is to permit two different reimbursement approaches to co-exist, one for outpatients and one for inpatients, without mandating either one.

A high deductible is intended to save cost, preserve individual choices, and to restore consumer negotiating power: consumers gain control to negotiate prices for better service. They can readily observe what is happening, and can readily move to another provider.

However, for incapacitated patients within an inpatient complex, such advantages become unrealistic. Their bundled services (psychiatry may be an exception) should be priced by diagnosis. Although the present DRG (Diagnosis Related Group) system badly needs revision, its introduction by Medicare in 1983 proved so superior to item reimbursement and cost reimbursement, that almost all health insurers employ it.

Moral hazard, which is much lessened for services within the deductible, reappears when the deductible is satisfied, especially when the decision is made to enter the hospital. A financial incentive exists for patients to prefer more expensive but fully insured inpatient care. 1) Accordingly, it would be wise to allow the deductible threshold to rise when excess funds appear in the Medical Savings Account; since that would lower the insurance premium further, the individual has some incentive to agree to it. 2) The patients who select more economical care should share the savings they create. Therefore, policymakers (and providers) should reconsider their instinct to limit the benefits of health insurance strictly to health expenditures. 3) To this end, Medical Savings Accounts should be unified with some or all federal, and federal qualified, tax-preference funds, including possibly Social Security itself. 4) In order to sharpen the focus of most concern to the matters where moral hazard is greatest, a series of insurance carve-outs should be added. These carve-outs would focus on issues where other concerns are greater than the moral hazard feature, for example, obstetrics and terminal care, or where the moral hazard is significantly different, as in-home care and durable medical equipment.

In all efforts to structure incentives away from moral hazard concerns, it should be remembered that draconian countermeasures have already been tested and failed. If individuals desire care-managers to work on their behalf, they should be charged for that unbundled service out of their Medical Savings Accounts, shifting the risk it will lower their medical costs, and the profit if it does, to themselves. Rationing has been firmly rejected by the public, as well as deliberate limitation of medical facilities in order to ration by shortages. All of these approaches are bad politics. Finally, it should be noted that the preference for insured inpatient services has historically been addressed by expanding the limits of insurance to include outpatient care and home care. This might be good politics, but it is not good arithmetic since it has been one of the main sources of healthcare inflation in recent years.

4. LIFETIME COSTS RATHER THAN ANNUAL COSTS. BEGIN WITH TERMINAL CARE. Medical costs are rapidly concentrating in two places: the first year of life and the last year of life. Because of the technology cost to achieve that transition, it makes take several decades for it to become obvious. Meanwhile, the design of health insurance should begin the process, incrementally, of moving to lifetime health insurance instead of annual insurance. Eventually, it can be expected that the cost of living too long will be equal to the cost of dying too soon, but cost predictions are presently difficult. We could rather easily begin the process -- by carving out the cost of terminal care, insuring it separately from the rest of Medicare, and demonstrating to the public the remarkable power of COMPOUND INTEREST ON INTERNAL INSURANCE RESERVES. For example, it has been loosely stated that two thousand dollars invested at birth, compounded tax-free, would roughly pay for an average lifetime's medical expenses.

Carving out terminal care could be accomplished without the public much noticing it, by the following means. Medical care would continue to be paid for by conventional methods, but all costs which fall in the last year of life would be designated "terminal care" and retrospectively reimbursed to the insurance entity which paid them. Since substantial proportions of Medicare funds are now being paid out during the last year of someone's life, the reduction of Medicare's pay-as-you-go "premium" would be considerable. Accordingly, a comparable amount could be set aside from Social Security payroll taxes, invested at compound interest, and eventually made available to pay the individual's terminal care. Transition costs, future cost projections, interest rate risks, and methodology of investment are set aside in this discussion since this project would have to develop some actual experience before a final design is possible.

5. CARVE-OUTS. By limiting health insurance premiums to the current year, the uncertainty of future medical cost inflation is addressed. However, this insurance advantage is confounded by treating all medical costs as if they were random events, including any costs which can be deferred into a different premium year, and other costs (like birth and death) which lack the individual potential for occurring randomly in multiple years. To the degree that such medical costs can be teased out of their mixture with more random risks, opportunities for patients, providers, and insurers to game the system are reduced.

A carve-out system for terminal care has been mentioned, as well as a carve-out of managed care management costs. The latter might be paid for outside of the Medical Savings Account, just as investment advice is often paid for outside an IRA, in order to preserve tax-exempt funds. (The same may be true for preventive care costs). If managed-care management advice actually saved money, fee-based advice might be a prudent option to adopt. It seems very likely that prescription drug costs will be handled as a carve-out. Psychiatry has long proved unsuitable for payment by diagnosis; failure to confess to this has almost destroyed inpatient psychiatry, and there is some urgency to carve out and significantly revise psychiatric care reimbursement. The same applies to home care, durable medical equipment, and probably other areas of healthcare. No reimbursement system can be carried to the present extreme of "one size fits all, let's extend it to other things."

A carve-out of the COST OF OBSTETRICS AND POSTNATAL CARE sounds radical but could be mostly transparent, as well. It is more likely to provoke political resistance, however, since it represents a reversal of parents paying for children, to individuals paying their own birth costs. One birth cost per person paid for by health insurance in the usual way and repaid to that health insurance like a mortgage or a tax on the Medical Savings Account. Just as is true of a mortgage prepayment, the individual would have various options for early, average, or late repayments, reflecting the accumulated funds in his account.

PREVENTIVE, OPTIONAL, COSMETIC AND OTHER ELECTIVE MEDICAL COSTS should also be carved out, for the reason that present rules excluding them from coverage are unworkable. (Preventive care has already been carved out of Health Savings Accounts by excluding them from the deductible; it might be wise to demand proof of effectiveness before making this sweepingly inclusive). It would be equally unworkable to insure them all. It seems better to create carve-out insurance for these costs, provided with funding that does not affect traditional healthcare premiums. Such a system would provide a funding mechanism which must be paid for, rather than the present system of futilely insisting that these costs are illegitimate when in fact they are not. The main argument against using insurance to pay for preventive care is that there is no risk, everyone ought to have it. So the insurance just adds unnecessary costs. When Medical Savings Accounts become more widely adopted, this issue may disappear.

6. CCRC Retirement communities should be encouraged to become the center of health care delivery in their regions, by removing regulatory or tax obstacles, particularly the IRS opposition to accumulating healthcare volunteer activity credits against later healthcare needs of their own. Tax and regulatory obstacles to the use of vacant infirmary and outpatient facilities, community physician and laboratory/x-ray facilities, and pharmacy/durable equipment providers should be removed. Since this trend conflicts with locally established providers, mechanisms should at least be developed to match these transitions to the migrations of elderly populations in any particular region. * * *

IN SUMMARY, this whole scheme can be described as "SUPPLY SIDE" HEALTH INSURANCE REFORM. It generates new funds for healthcare by a) reduced small-claims insurance costs b) reduced "moral hazard" overutilization costs c) compounded internal investment of reserves and d) utilization of the now-wasted labor potential of young retirees. It does not aim directly at the goal of reducing the number of uninsured, except on the principle that if something becomes cheaper, more people can afford it.

Or, A Few Bad Apples?

|

| Surgeons |

Plaintiff lawyers and physicians do occasionally meet socially. A common way to skirt the awkwardness is to nod agreement that the malpractice problem is caused by a few bad apples in both professions. As competitors, physicians can be censorious; doctors who have never been sued find it easy to accept that those who do get sued must be substandard. This contention has been examined many times, and it is pretty firmly established that doctors who are sued are at least as competent as those who are not. While it's undeniable that sociopaths can creep into any profession, this truism has led to few reform proposals of any great promise. It's not true that every doctor gets sued at least once, but in some specialties like obstetrics a majority are sued, and those specialties soon develop shortages. Certain cities and states have a greatly increased incidence of a suit. Put that together, and you can safely predict impending shortages of particular specialties within certain zip codes. It would be a simple matter to examine the quality of particular medical specialists in those zip codes, and then for fairness examine the local legal climates. The outcome of such a study is rather easily predictable.

To assess the matter in a less confrontational way, look at insurance premiums for malpractice coverage. Doctors with a single case in their history can usually obtain insurance at standard rates, but premiums go up considerably after a history of two or more claims. Shopping the market through a broker will usually not discover an insurance company which will yield on this point. All states permit higher premiums for applicants with a history of multiple claims. Since insurance companies keep careful statistics and analyze them constantly, it seems likely they do have proof that one predictor of future claims is a history of having prior claims. There are other predictors, not necessarily marks of criticism: practicing in certain states or cities is risky. Working in certain surgical specialties is a risk. The bigger a doctor's practice, the more opportunity for claims to arise. Mix all this together, correct one factor against another with computers, and you seem to find a small proportion of cases concentrated in an unlucky few physicians. No further tweaking of the data will specify any characteristics of the suit-prone group. Since that leaves you with the conclusion that the only way to identify the suit-prone is to wait for three or four suits, the matter must be approached with resignation. Fortunately, the contribution of these people to the problem, while undeniable, is small.

In desperation, some even suggest an approach once adopted by Napoleon. He said he didn't like unlucky generals and fired them summarily. The managers and coaches of sports teams are similarly treated, and somehow we accept the injustice of it. But regardless of the merits of such pragmatism in win-lose team encounters, it misses a central point in negligence suits.

The patient, counseled by his lawyer, makes the decision to sue. Studies of many hospitalizations reveal the cases brought to the law are not materially different from many other cases that do not result in a lawsuit. The cases brought to court seem chosen by anger, mendacity, or just bad luck. Their grievance may or may not be justified, but it is not a degree of justification which distinguishes them from 90% of similar cases. Many studies of suit-prone physicians have been made, but it's uncomfortable to conduct studies of suit-prone patients. Who can doubt that identifiable suit-prone patients would discover they had difficulty finding a doctor? In summary of this point, the published levels of malpractice premiums are reasonably good measures of multiple suits. Since some regions have vastly higher premiums than others, it remains to be demonstrated whether those areas somehow have a vastly increased number of suit-provocative doctors. Or whether the variability is more fairly described as a local legal one.

Philadelphia in 1976: Legionaire's Disease

|

| The Yellow Fever |

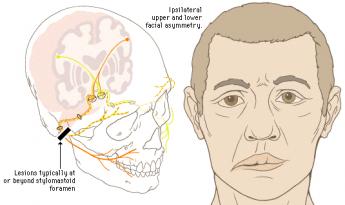

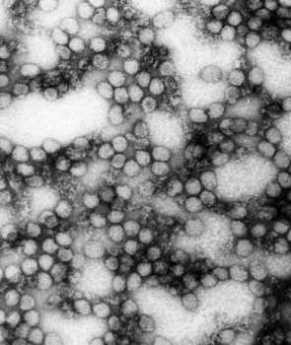

No other city in America is remembered for an epidemic; Philadelphia is remembered for two of them. The Yellow Fever epidemic, for one, that finished any Philadelphia's hopes for a re-run as the nation's capital. And Legionnaire's Disease, that ruined the 1976 bicentennial celebration. One is a virus disease spread by mosquitoes, the other a bacterial disease spread by water-cooled air conditioners. Neither epidemic was the worst in the world of its kind, neither disease is particularly characteristic of Philadelphia. Both of them particularly affected groups of people who were guests of the city at the time; French refugees from Haiti and attendees at an American Legion convention.

In 1976, dozens of conventions and national celebrations were scheduled to take place in Philadelphia as part of a hoped-for repeat of the hugely successful centennial of a century earlier. Suddenly, an epidemic of respiratory disease of unknown cause struck 231 people within a short time, and 34 of them died. Every known antibiotic was tried, mostly unsuccessfully, although erythromycin seemed to help somewhat. The victims were predominantly male, members of the American Legion of a certain age, somewhat inclined to drink excessively, and staying in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, one of the last of the grand hotels. Within weeks, it was identified that a new bacterium was evidently the source of the disease, and it was named Legionella pneumophila. Pneumophila means "love of the lungs" just as Philadelphia means "city of brotherly love", but still that foreign name seemed to imply that someone was trying to hang it on us. Eventually, the epidemic went away, but so did all of those out-of-town visitors. The bicentennial was an entertainment flop and a financial disaster.

Since that time, we have learned a little. A blood test was devised, which detected signs of previous Legionella infection. One-third of the residents of Australia who were systematically tested were found to have evidence of previous Legionella infection. A far worse epidemic apparently occurred in the Netherlands, at the flower exhibition. Lots of smaller outbreaks in other cities were eventually recognized and reported. It becomes clear that Legionnaire's disease has been around for a very long time, but because the bacteria are "fastidious", growing poorly on the usual culture media, had been unrecognized. And, although the bacteria were fastidious, they were found in great abundance in the water-cooled air conditioning pipes of the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. Even though the air conditioning was promptly replaced, everybody avoided the hotel and it went bankrupt. When it reopened, 560 rooms had shrunk to 170, and it still struggled. Although there is little question that lots of other water-cooled air conditioning systems were quietly ripped out and replaced, all over the world, the image remains that it was the Bellevue, not its type of plumbing, that was a haunted house. There is even a website devoted to its hauntedness.

Please Don't Lose Any Sleep Over This

|

| Dr. Charles Czeisler |

The Institute for Experimental Psychiatry Research Foundation meets alternatively in Boston and Philadelphia, in recognition of its rather complicated historical relationship with Harvard and Penn. The Spring 2005 trustees meeting was held in Boston, with Dr. Charles Czeisler of the Brigham and Women's Hospital making a presentation of his work with sleepy resident physicians. Sleep is now a central focus of the work of the Institute, particularly the effect of lack of sleep on performance. Resident physicians are a group with lots of experience with sleep loss, so much that such experiences as residents are central imprinting in the lifelong brotherhood of the profession. The public tends to regard the torment of protracted craving for sleep as some kind of dangerous hazing inflicted on professional newcomers by sophomoric seniors. Every once in a while, someone gets hurt by these games. That seems to be a general public reaction. For the most part, by contrast, members of the profession who have themselves undergone the experience turn away silently from such unfeeling remarks. As the old contraceptive joke about the Pope has it, if you don't play the game, don't make the rules.

In the first place, it is wrong to suggest that resident physicians are somehow helpless victims of authority, abused slaves of somebody's profit motive, or warped masochists enduring the process in order to inflict it on someone else. Perhaps the example of my classmate Seibert is useful. As a freshman medical student, Seibert was so overwhelmed by the volume of facts he was expected to learn, that he decided to give up sleep entirely. Seibert, by the way, was no moron; he was an honors graduate of a very selective Ivy League university. And he actually did stop sleeping for more than two weeks until he collapsed and had to be stopped. This was his own choice, gamely adopted in spite of general ridicule. And to show that overachieving is not limited to physicians, there was my oriental patient, the daughter of the President of her country. She related that as a graduate student she did not go to bed for three years; during all that time, she sat at her desk, slapping her face to keep awake. What we are talking about here is a self-selected group of committed and dedicated people, perhaps overly shamed by the specter of failure.

The work of our Institute has helped document and understand the injurious effect of sleep loss on performance; no one can go very long without sleep before responses and vigilance begin to deteriorate. A great many vehicle accidents are caused by drowsy drivers; it is a concern that pilots of airplanes on long-distance flights are to some provable degree less competent to land the plane. Therefore, it is not completely surprising to find that interns on protracted duty do make 20% more errors in medication orders, and nearly 50% more diagnostic errors. It is jarring to discover a measurable increase in the number of intern auto accidents, particularly when driving home from work. Maybe we ought to pass a law about it.

Commiseration is one thing; proposals to interfere are quite another. For one thing, the time-honored protection against the harm of this problem is redundancy. The complex, fast-paced and dangerous environment of a hospital, like that of an airline cockpit, has very little tolerance for lack of vigilance. Our solution has been to do everything three times, with overlapping responsibilities and repeated opportunity for catching errors before they get through to the patient. Although the malpractice lawyer seeks to pin the whole blame on some person, particularly one who is covered by insurance, the reaction of doctors to adverse events is to presume that at least three people must have cooperated in letting it slip through. At night and on weekends, the reduced staff tends to weaken the defensive network. But by every assessment, the greatest threat to our protective screen of redundancy is cost control. Any manager of managed care can find duplication and overlap in ten minutes of searching for it in a hospital; redundancy is a big factor in the high cost of running a hospital. The law of decreasing returns will dictate that it becomes very expensive to eliminate the last one percent of errors. To state it in reverse: it is very tempting to save a bundle of money in a competitive world, by accepting only a small increase in the errors. Since it is a matter of opinion, physicians are grimly determined that it shall be physicians who strike that balance. Those who press for more punitive treatment of physicians in the matter of errors should reflect that it surely will convince physicians to flee the risk of responsibility for the decision of where to strike the balance.

If you bend metal repeatedly it will crack; if you stretch a rope too hard it will snap. These unfortunate events are not called errors, and it is improper to search for blame in them. The medical profession is aghast that the public does not seem to appreciate that average life expectancy has increased by thirty years in the past century. That's not ancient history; life expectancy has increased by three years in the past ten. A system that produces a result like that is entitled to a certain amount of tolerance for its errors if we must call them errors. In other environments, that's known as pushing the envelope. Anyone who thinks it's fun to stand on your feet for thirty-six consecutive hours -- hasn't tried it.

Surgeons are perhaps somewhat more conscious of the need to train young professionals to drive themselves beyond ordinary endurance. After all, if an operation is unexpectedly prolonged, the surgeon can't just quit, he must finish. Neurosurgeons, with their fourteen-hour procedures, are particularly vehement on the topic. But it is true of every physician, too. When the telephone rings in the middle of the night, will this young fellow haul himself out of bed, or will he tell the patient to take an aspirin and call again in the morning? Increasingly, we hear complaints from patients that other doctors didn't even take the trouble to examine them; the implication that we are somehow not like that is very flattering. Part of the training is forbearance, too. At three in the morning, it is very easy to feel sorry for yourself and to reflect that an administrator with four times your income is home in his nice warm bed. The fact is, that if the person who is up and on his feet doesn't do the job, no one will.

|

| Cadwalader |

Some incomprehension from bystanders must simply be endured with patience. Beyond that, it could be futile to seek a complete understanding. Quite recently, I was explaining to a young lady in a tailored suit who Thomas Cadwalader was. His portrait, beneath which we were standing, hangs in the great hall of the Pennsylvania Hospital. Although he died in 1789, Dr. Cadwalader is still famous for his remarkable, unfailing courtesy. A sailor in a tavern on Eighth Street once waved a gun and announced to the crowd he was going out the swinging doors to shoot the first man he met. The first man happened to be Dr. Cadwalader, who tipped his hat and said, "Good morning, sir." So, the sailor shot the second man he met.

The young lady in the tailored suit brightened up. "The moral of that story, " she said, "Is always wear a hat."

Medical Generation Gap

|

| Miriam Schaefer |

To understand the dynamics of the following medical anecdote, the reader should understand the thrust of Miriam's First Rule of Management. Miriam is my oldest daughter, with long experience managing many firms, large and small. Her rule is that when an employee starts misbehaving for no good reason, eliminate the position. Invariably, well almost invariably, an employee who starts acting out doesn't have enough work to do. If you are managing a large organization, you should also consider firing the supervisor of that person, on the grounds the supervisor should have noticed there was not enough work for the employee to do and was probably covering up.

My anecdote concerns a session at the 2006 annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, ostensibly devoted to the conflict between generations of doctors. It didn't take long before the meeting turned into an uproar about the new work rules which prohibit a resident physician from working more than 80 hours a week. That's supposed to protect patients against mistakes of sleepy doctors, although some suspect it is mainly an outgrowth of a gap between what they do and what they expected to do. From the time they entered high school, future doctors have been taught to expect workaholic employment conditions, and while more normal people haven't been taught that message, that's irrelevant. The situation is aggravated by the increased admission of women to the profession, who for their part have been taught to expect a breathless race between finishing their work and getting home to relieve the babysitter. Perhaps in time the newly invented specialty of "hospitalists" will get established and accepted, along with accident room work as another harrowing occupation which abruptly ends its day by the clock rather than the backlogs. At the moment the pioneers must overcome the suspicion, only partly fair, that Miriam's First Rule applies to them.

If not, that Rule clearly does apply to the youngsters who now must go home to spend quality time with their families, because they are not allowed to exceed the new work rules. At the ACP meeting, a dozen of us Civil War veterans were treated to an appalling amount of teenage mumbo jumbo apparently emanating from unsuspected warfare between Generation X and the Baby Boomers, their supervisors, mentors, and colleagues. All of us Civil War veterans held the private opinion that Baby Boomers were a little self-indulgent, but in the eyes of Gen Xers the boomers are workaholic fanatics, incapable of relaxing even for a moment in order to enjoy the life of the good, the true and the beautiful.

As we passed out of the room at the end of the session, one of the silent gentlemen with white hair came over to me. We didn't know each other, but we recognized the signs of a silently shared opinion. The old doctor leaned over to me and muttered, "They offer nothing, but they want everything." I smiled, and we parted. I guess I might have told him about Miriam's First Rule, but it would have taken too much explaining.

Medical Tort Reform (1)

The U.S. House of Representatives will soon consider a medical malpractice reform (limiting awards for pain and suffering to $250.000) which it adopted seven times in the last ten years. Following almost certain House passage, the proposal will then confront the Senate,

|

| cartoon malpractice |

where it has failed seven times. The politics of the two chambers are not chief concerns of this paper, which strongly advocates passage. The paper contends that unwise incentives for patients to bring suit are important causes of present difficulty, and reducing such incentives offers a comparatively simple opportunity to bring the complex issue to quick stability. Stability is essential before more sweeping changes can be examined. The collection of data in certain areas would reduce the scope for vituperation and ideology, another important step toward a solution. Full recognition must eventually be given to the intertwined complexity of industrial product liability, the McCarran Ferguson Act, hospital and corporate governance in general, the tort system, pass-through of Medicare and Medicaid overhead reimbursement to malpractice premiums, even universal health insurance. Some small step must begin such an interlocked rearrangement, and a cap on pain and suffering has the major advantage of being successfully tested by twenty-five years of experience in California and Indiana.

This paper makes no claim of identifying all the root causes or predicting all the calamitous consequences of inaction. Advocating passage of national laws to reduce plaintiff incentive to sue, it chiefly focuses on the chief arguments historically made against the present proposal, offers some comparatively novel insights in favor, and makes suggestions for collecting data to reduce the latitude for disagreement.

Congress will again take up malpractice tort reform (MICRA) in 2005. perhaps successfully. The 2004 outcome was close. Since the Republicans subsequently made electoral gains in both House and Senate, the leadership is considered likely to re-introduce the same bill and try to hammer it through. The bill's medical essence is to limit awards for "pain and suffering" to $250,000, contrasting strongly with recent escalating awards which have sometimes reached $100 million. Newcomers to the issue may be surprised that so much emphasis gets placed on this point, but thirty years of wrangling experiences in state legislatures have produced this reform alone with proven effectiveness. In the course and semi-jocular language of politics, "nothing helps the malpractice problem unless it involves on

The Blue Cross Discount (6)

|

| Blue Cross Blue Shield |

Since I've alluded to the two basic problems in health financing today, perhaps I need to explain them. What's known in hospital circles as the Blue Cross discount refers to the wide disparity between what the hospital will accept from an insurance company and what they will demand in payment from someone who has no insurance. It's often double the price. It's a tragedy that forty million Americans don't have health insurance, all right, because it costs them twice as much. It's a punishment for the terrible crime of not buying insurance, to call a spade a spade.

That sounds like a pretty easy problem to fix, doesn't it? Stop overcharging them, and half of the problem of the uninsured would go away.

Furthermore, most of the people who do have health insurance are effectively able to buy it at seventy cents on the dollar, because they don't pay income tax on the money that goes for "health benefits" which is to say health insurance premiums.

Taken together, most people thus pay seventy cents for health care which will cost uninsured people two dollars. Most people would suppose that we ought to give a break to some poor devil who can't afford insurance, but in fact, we skin him alive financially. It's impossible to name any other necessity of life that's treated this way, and it's hard to think of any other problem that would be so easy to solve -- just charge everybody the same amount. If you are really bighearted, charge poor people just a little less,

Now, I refuse to get drawn into a history of the origin of these egregious situations. It has to do with price controls during World War II and the fact that investment capital for the health system was impossible to raise during the depression of the 1930s. But it doesn't matter in the slightest how this came about. What matters is how to make it go away.

Health Care Rationing, American Style

|

| Hayek |

The 2006 annual scientific meeting of the American College of Physicians used six or eight auditoriums simultaneously over a three-day period, to accommodate the gratifying number of new advances in medical science. I wandered into one session devoted to pulmonary embolism because it affects a close member of my family. But every citizen ought to ponder the non-scientific message of this session. Indeed, the anti-scientific message.

It turns out that 1% of the relatives of patients with pulmonary embolism will test positive for inheriting a gene that promotes this often fatal disease. But the speaker, invited as a national authority to speak for the College, cautioned the audience that it would be wrong to test the relatives of their patients with pulmonary embolism for the possibility of running a significant risk of this disease themselves. Why so? We have a pretty good way of preventing this often-fatal disease, by giving blood-thinners, and blood thinners are getting better all the time. So, naturally, there were questions from the audience of doctors. Why in the world wouldn't you test people for this preventable condition?

With obvious discomfort, the speaker did a little tap-dancing in his answers; but here is the substance of it. There is a risk of complications from the therapy, of about 5% a year so you must choose carefully among those who have a positive test. If the individual tests positive but is not treated, he may develop an embolism and sue you for not having treated him. Even if he doesn't develop the condition, he will probably be stigmatized for life and find that health insurance is overpriced or unobtainable. If you treat everybody, you will cause problems more often than the disorder would. So, don't test. If you don't know about the problem, you can't get into trouble for acting in an ambiguous situation.

Personally, I doubt that. If the person has an embolism, a keen lawyer can ask if any relatives ever had the same thing, and if so, the other doctor can be sued for not testing the relatives, hence not discovering, and not preventing the present sad, sad, situation. I'd like to think the rest of the medical profession will join me in disregarding this preposterous advice, testing these families to identify the people who are at risk, and then treating them with the best method then available.

But, you know, in the present climate of managed care and lawsuits, I'm not so sure that's what will happen. Meanwhile, my own children are all going to be urged to go get themselves tested, whether the test is covered by insurance or not.

Health Savings Accounts

The legislation removes the hampering restrictions of the 1995 Law. What follows is a brief outline of the main features of the HSA/MSA clause in the 2003 law,

|

| U.S. Capital |

as published by the main authorizing committee, the House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. From this point forward, more specifics of the program will probably be written by the Executive Branch and published in the Federal Register. The Ways and Means Committee will continue to exercise oversight authority, however, in conjunction with the Senate Finance Committee. As a consequence, statutory modifications of the program are likely to appear in future annual budget reconciliation acts, or else in any new Medicare amendments. The legislative route map becomes more understandable when it is recalled that Medicare itself is considered to be an amendment (Title XVIII) of the Social Security Act.

Committee on Ways and Means

Medicare Prescription Drugs, Improvement And Modernization Act of 2003

Health Savings Accounts (HSA's)

Lifetime savings for Health Care

Working under the age of 65 can accumulate tax-free savings for lifetime health can needs if they have qualified health plans.

A qualified health plan has a minimum deductible of $1,000 with $5,000 cap on out-of-pocket expenses for self-only policies. These amounts are doubled for family policies.

Preventive care services are not subject to the deductible.

Individuals can make pre-tax contributions of up to 100% of the health plan deductibles. The maximum annual contributions are $2,600 for individuals with self-only policies and $5,150 for families (indexed annually for inflation).

Pre-tax contributions can be made by individuals, their employers, and family members.

Individuals age 55-65 can make additional pre-tax "catch up" contributions of up to $1,000 annually (phased in).

Tax-free distributions are allowed for health care needs covered by the insurance policy. Tax-free distributions can also be made for the continuation coverage required by Federal law (i.e., COBRA), health insurance for the unemployed, and long-term care insurance.

The individual owns the account. The savings follow the individual from job to job and into retirement.

HSA savings can be drawn down to pay for retiree health care once an individuals reach Medicare eligibility age.

Catch-up contributions during peak savings years allow individuals to build a nest egg to pay for retiree health needs. Catch-up contributions allow a married couple to save an additional $2,000 annually (once fully phased in if both spouses are at least 55.

Tax-free distributions can be used to pay for retiree health insurance (with no minimum deductible requirements), Medicare expenses, prescriptions drugs, and long-term care services, among other retiree health care expenses.

Upon death, HSA ownership may be transferred to the spouse on a tax-free basis.

Contain rising medical costs- HSA's will encourage individuals to buy health plans that better suit their needs so that insurance kicks in only when it is truly needed. Moreover, individuals will make cost-conscious decisions if they are spending their own money rather than someone else's.

Tax-free asset accumulation- Contributions are pre-tax, earnings are tax-free, and distributions are tax-free if used to pay for qualified, medical expenses.

Portability- Assets belong to the individual; they can be carried from job to job and into retirement.

Benefits for Medicare beneficiaries- HSA's can be used during retirement to pay for retiree health care, Medicare expenses, and prescription drugs. HSA's will provide the most benefits to seniors who are unlikely to have employer-provided health care during retirement. During their peak saving years, individuals can make pre-tax catch-up contributions.

Chairman Bill Thomas Committee on Ways and Means 11/19/2003 12:56 PM

Financing a Research University

|

| Harvard |

Fifty years ago, only three American universities, Harvard, Yale and Princeton, were considered world-class. The benchmarks for them were Oxford and Cambridge Universities; both British universities had long history and great prestige. Making allowance for wartime disruption, it was also considered pretty classy to study at the Sorbonne, or Humboldt University in Berlin. Sweden, Vienna, Rome were right up there in prestige.

|

| Oxford |

By 2004, a London magazine was offering its view there were thirty American Universities better than anything in the European Community, in particular, Oxford and Cambridge. We'll pass over the Economist's anguished analysis of what's wrong in old Europe, and focus here on what American universities are doing right. They certainly do seem to be doing something right, but nevertheless, it's still possible to be uneasy about where they are going.

|

| Cambridge |

For example, the top three all have more than ten billion dollars apiece in their endowment funds, and thus each perpetually generates roughly half a billion annually in disposable income from passive sources. You can accomplish a lot of worthwhile academic things with that much money. Operating revenue like student tuition, fees, research grants, and royalties should support normal running expenses, so endowment income is available for new frontiers of learning, research, and social endeavor. These well-run institutions unquestionably do accomplish many innovative and important advances, to the point where it is simply trivial to point out a few areas of waste or misjudgment. Multiplying their annual discretionary funds by thirty offers an overwhelming force for good in the nation, and in the world.

|

| British |

The other twenty-seven premier research universities may not all have ten billion dollars apiece, but they have the Avis or we-try-harder motivation that may make up for it. The nation really does appreciate its worth. Applications for admission outnumber available places twenty to one, would be even greater if more people thought they had a chance to get in. Outstanding professors are in scant supply, commanding higher and higher salaries. In fact, a patient of mine who is a trust and estate lawyer tells me he gets a little uneasy about the growing number of university professors he sees with million dollar estates. A calm view would be that the nation recognizes the value of superior education, and is forcing the pace for a greater supply of it. Unless our economy experiences a disastrous decline, it is reasonable to expect a hundred universities to migrate up the quality chain in the next generation; most of those eligible for it are grimly determined to see it happen. China can make all the widgets it pleases, but that won't make them catch up with this champion competitor. The French can maybe make better wine, but unless they pep up their schools, they're going to have no shot at glory.

Whew. That's intentionally laying it on thick because American academic triumphalism has a darker side to give one pause. In the first place, the arrogance of it shows. Even the European aristocrats, formerly world experts in flaunted put-downs, are irritated; and red America is really sore at blue America. Sprinkling a few research universities into Arkansas and Idaho might relieve regional divisiveness somewhat, but lasting social peace can only derive from starting in the third grade of, say, North Philadelphia, Kensington, and Norristown. In economic downturns, the country would have big trouble financing universal, bottom up, academic excellence. The tragedy is that money isn't the main problem in the science classes of the thirty research universities we already have; an alarming number of those seats are filled with foreign-born students, not even to mention the honors students.

Secondly, the system is already under strain. The families of students are hard pressed by tuitions of fifty thousand dollars a year, and increasingly ready to complain about the inability, of classes of three hundred taught by non-tenured teachers, to justify to them such breath-taking fees. They may not understand educational financing, but they can count, and then multiply two numbers together. Faculty rewards favor research, not teaching, and teaching is what the students think they are paying for, their parents think they are sacrificing for. If what they are truly paying for are just credentials, they worry that affirmative action will cheapen the credentials. One clear sign of unease is the tendency of children from wealthy families to walk about the campus in torn overalls. This may be more than just a fad, it may be a sign they hope to hide from the university's system of redistributive taxation. Some people pay those high tuitions, but mostly tuitions are discounted for the eager family's ability to pay. Wearing blue jeans won't help, the universities demand to see the family's audited tax returns. In my presence, a university president remarked that the system was designed to extract the last dime from every student. The whole middle class is being asked to give until it hurts, for the unspoken goal of elevating a hundred more research universities to world class. Very few question the premise that unmatchable universities are the key to American world eminence. Quite a few, however, have anxiety that it may not work out for each individual. It may only be a lottery with slightly better odds.

Now, let's get to the research part of the research university. In the past ten years, American universities have collectively received six or seven billion in commercial patent royalties; the aggregate now runs appreciably more than a billion dollars a year and it's growing.

The normal arrangement is to give 20% of royalty income to the professor whose name is on the patent. Since most research is performed by large teams, it is possible to imagine considerable inequity and academic bad feeling in this system. In other walks of life, striving for a bigger share of two hundred million a year would cause differences of opinion about fairness. Here and there, you read articles by participants in this system who are concerned over the message it is sending to the students about personal values. Universities that began with a mission to educate the clergy are now seemingly overpraising the big payoffs.

Many business analysts feel that a successful corporation needs to spend 10% of its revenues on research and development. Behind that is a realization that prices and profit margins are largest for new inventions, steadily declining as the new invention attracts competition and eventually becomes a mere commodity. The scientific term entropy is a perfect description of the way world economies seemingly work, like clocks gradually winding down. So businessmen get rid of old products and look for new ones, and the universities are the source of most new ideas and products. Put every last cent into R & D for new products, while the developing countries grind out widgets. If we eventually graduate hundreds of thousands of Americans from unmatchably excellent research universities, the outcome will take care of itself. Even flying airplanes into our tall buildings can't make much difference in this academic arms race. It's essentially how Ronald Reagan defeated the Soviet Union, and it's discouragingly difficult to argue it is totally wrong.

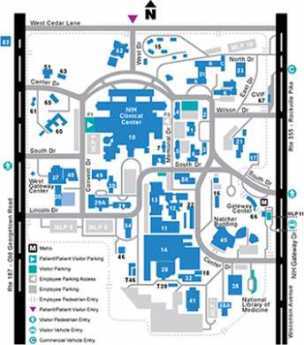

However, you can imagine ways that it might all fall apart. The source of at least half the capital now pouring into the research universities comes from the federal government, particularly the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation and the Department of Defense. It only takes fifty-one votes in the U.S. Senate to change that suddenly, for reasons of national defense, to defend the value of the dollar, to combat inflation, or lots of other reasons. Even now, universities often face annual crises at the end of a funding cycle, when projects have been awarded, people hired, but funding is delayed for uncertain periods of time because of distant political wrangles within the budget process.

That's known as a cash flow problem, and even it is trivial compared with what would happen if federal research funding were delayed a full year. Just look at any university and see all the big tall buildings. They have largely been built to house research activity, and the university would have big difficulty selling them if they were empty. They've usually been paid for with mortgages, and it costs a lot of money to heat, air condition, clean and repair them. Just cut off the cash flow long enough, and you will see how risky it was to get into the research arms race.

Flexner Report, Revisited

|

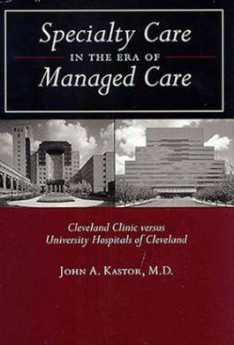

| Specialty Care In The Era Of Managed Care |

Book Review

Specialty Care In The Era Of Managed Care

Cleveland Clinic

versus

University Hospitals of Cleveland

John A. Kastor, M.D.

0-8018-8174-9

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Abraham Flexner's 1910 Report practically canonized the notion that medical schools must be owned by universities. Forty years later, Dwight Eisenhower firmly disagreed. Asked why ever would he give up the pleasant life of Columbia University president to get into the nastiness of national politics, he replied, "The White House doesn't run a medical school." During the same era, Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Senator Robert Taft, political enemies but personal friends, were riding to New Haven together to a Yale trustee meeting. The two agreed it was unfair for 40% of university budget to be spent on 1% of the student body, and decided Yale should get rid of its medical school. Their subsequent motion failed by only one vote at the meeting. And as a final Flexner footnote, Princeton University which shrewdly never owned a medical school, is now nonetheless in the news over the central underlying discordance -- managing huge sums which, either by contract or donor restriction, are inflexibly assigned to a single department, thus substituting the donor's priorities for those of the University president. Medical school ownership of teaching hospitals raises the same issue except in reverse. It is politically impossible to treat an affiliate as a cash cow without learning the harsh reality of the Golden Rule: the affiliate with the gold will promptly remake the rules.

Understanding these issues but seldom emphasizing them, John A. Kastor has done us all a great favor by studying and publishing the unseemly disorders which result, in many cities and institutions. His particular focus in this book is on Cleveland, where all that matters medically is the prospering Cleveland Clinic and its struggling rival, Case Western Reserve. The book is mainly focused on a particular question: under managed care, should teaching hospitals adopt the Cleveland Clinic's style and organization, in order to prosper as they do? In the end, he cannot quite bring himself to recommend it. Essentially, the Clinic is run by doctors, for doctors. The clinic pays salaries, but (so far) bills fee-for-service. The over-reimbursed procedural specialties such as surgery subsidize the under-reimbursed cognitive specialties (prompting East Coast colleagues to sneer at "organized fee-splitting".) Cleveland's Clinic, like all group practices, must devise strategies to a)induce acquiescence to the subsidy of internists by surgeons, b)discourage physicians from starting competitive practices in the neighborhood or c)turning their salaried incentive into an instant 40-hour week. Not everyone will submit to what is between the lines, most notably at the Clinic's Florida satellite. But since the alternative is to hire non-physicians with concealed animosities to doctors to run hospitals and medical schools, all physicians who actually treat patients must give the physician-run group practice model some thought based on experience with its alternative.

We all have an unfortunate tendency to assume that weakness of character is the main cause of the executive misbehavior so widely observable in all corporate environments. In the medical world, a much more powerful force is generated by shifting quirks of reimbursement. Once the pecking order is established between hospital and school, medical school and university, it gets violently upended by the underdog suddenly getting riches from the Senate Finance Committee, then upended again by Ways and Means a few years later. Or bureaucrats in Rockville, in Baltimore, or the Executive Office Building. Eisenhower was wrong, the White House does run medical schools and hospitals when they would very likely be better run by physicians. In fact, Flexner's offhand interposition of the University into this dogfight seems a little quaint. Just to mention the indirect residency reimbursement program, the institutional research overhead allowance, the old cost-plus reimbursement of hospitals, the institutional patent revisions, is to start a list which can get to be quite long. In most of these cases, an institutional component which needed to be subsidized in the past has now become prosperous and is asked to return the subsidy. The chief executive is then caught between duty to his institution, the threat of investigation if funds shifting is suspected, and his own sense of fairness. That these upheavals are so frequently pacified without serious harm to the patients, is a credit too seldom given.

Dr. Kastor's writing is somewhat hampered by a need to footnote, document and defend everything he says. Nevertheless, the book will be read by physicians like a novel with a great many villains. It's encouraged reading. One hopes that the next book in the Kastor series will examine the Florida satellite clinics of the Cleveland Clinic and of the Mayo Clinic, one making money and the other losing money. Maybe some basic issues of an effective medical organization can be resolved by making different comparisons.

But don't expect permanent axioms to emerge; Medicare Risk contracts are coming. Under capitated systems, administrative incentives are slanted to discourage expense, especially expensive surgical procedures. Perhaps group practices will soon face a need to have their internists subsidize their surgeons, reversing the traditional arrangement. The threat to collegiality, so evident in this book, is destined to continue.

Friends Lifecare at Home

Over thirty Quaker retirement villages scatter through America, more than twenty in the suburbs of Philadelphia -- "under the care of the Yearly Meeting", as their expression has it. But for some people, community living seems unattractive. It does not speak to their condition.

For one thing, it may not be affordable.

|

| Friends Lifecare |