4 Volumes

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Culture: The Flavors of Philadelphia Life

Philadelphia began as a religious colony, a utopia if you will. But all religions were welcome, so Quakerism mainly persists in its effects on others, both locally and in America, in Art, clubs, and the way of life.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Architecture in Philadelphia

Originating in a limitless forest, wooden structures became a "Red City" of brick after a few fires. Then a succession of gifted architects shaped the city as Greek Revival, then French. Modern architecture now responds as much to population sociology as artistic genius. Take a look at the current "green building" movement.

A new book is out that I recommend: Philadelphia Builds

Architects quickly tell you that spending extra money to make a building "green" is most popular with institutions, like hospitals, schools, and museums which expect to remain functionally unchanged for the next fifty years. It costs extra money to build a building which will last, and extra investment is needed to introduce all those good green things which will reduce the costs of maintenance. So you want to have confidence you will remain in the building longer than the 11 to 14 years it takes to pay off the initial cost. Anybody can see the sense of substituting fluorescent light bulbs for incandescent ones, because you will be money ahead in six months. But most of the rest of these green proposals encounter significant resistance from commercial tenants who are only somewhat confident they will be using a particular building five years from now. Even if wildly successful, a business will wish to move upscale, and if unsuccessful will close down. As far as housing is concerned, there is the same dream of moving upscale, balanced only by the possibility of moving away to a better job opportunity. We are no longer a farm community, or even a city of local professionals. Yes, it is possible that landlords of high-rise apartments may devise ways to pass long-term economies along to successive tenants. But this green thing isn't all that certain to work; the price of oil could drop enough to make green investment worthless. The logical place to start the experiment is with institutions, followed by professionals and cultural groups with a long tradition of local stability. In a word, Quaker churches.

Looking at it from the other direction, Philadelphia has a large number of very solid masonry houses which are under-occupied, hence cheap. Some of this traces back to the major fires of the Eighteenth Century, which resulted in zoning codes prohibiting wooden structures even at the Eastern edge of a limitless forest. Some of it reflects the sheet of bedrock, called Wissahicon Schist, which underlies the city from the old Naval Yard up to the point it breaks out on the surface in Chestnut Hill. New Jersey, over the river, is built on sand or at most blue marl clay, so it still favors frame houses. And the automobile tended to depopulate the grand old houses of Philadelphia, so big solid houses are available for restoration and renovation at half the price of building new houses which would probably be less substantial. There's also the remarkable fact that many old houses were built before central heating became popular, so they even survived without termite infestation in the swampy area between two rivers. So, circumstances made it attractive to renovate and make available a lot of big, cheap, very durable houses. That largely means nothing to prospective new industries, and there are the contrary factors of high crime and taxes, and poor public education. So, a process of social Darwinism takes over, encouraging the growth of a population which can ignore those factors while taking advantage of the long-term economies of durable permanent housing. The prospects for this transformation are slow and discouraging, and unfortunately will remain struggling until a population enthusiastic about our local advantages somehow achieves enough political influence to tip the balances. Low crime rate, low taxes, and good schools. Is there anyone opposed?

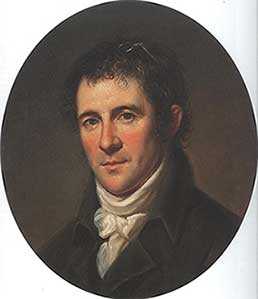

Recently, a sample of practicing Philadelphia architects were asked to name the handful of most influential architects in Philadelphia's past. The names repeatedly offered began with Smith, and then Latrobe, Strickland, Walter, Furness, Eyre, Howe, Giurgola, Kahn and Venturi. As you walk around Philadelphia, these were the sources of what makes the City look uniquely different, whether by building, or by influencing other architects to build in similar style. Let's look them over.

The Nation's Capitol

George Washington had been trained as a surveyor, created a rather handsome house in Mt. Vernon,

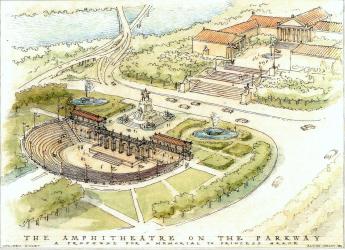

|

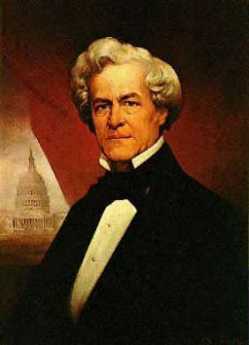

| Thomas Ustick Walter |

and had the new capital city, both located near his home and named after him. It is clear that ideas for the design of the new city and its major public buildings were brought to him for approval, and very likely adjusted themselves to his stated preferences. In the dedication ceremony, just about every political figure, dressed in Masonic costume, was lined up in two lines, which parted to allow Washington in full Masonic regalia to march majestically forward to lay the cornerstone with proper Masonic rites. Let there never be any doubt that it was his capital, in his capital.

|

| Charles Bulfinch |

The man who actually drew up the original design and oversaw the construction was Charles Bulfinch of Boston. The Bulfinch style was clearly evident by comparison with the rather bulbous dome which echoed the "Ether Dome" of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Both domes were made of wood, and the invading British army of the War of 1812 made short work of the Congressional dome. Most of the more detailed work of the building is attributed to Benjamin Latrobe in Philadelphia, and much of the classical style reflected the classical style favored by Jefferson, and much promoted by William Strickland, a Philadelphia trainee of Latrobe. The genius of total re-design along modern lines was the work of one of Strickland's Philadelphia trainees, Thomas Ustick Walter.

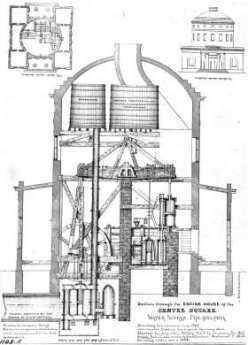

The capital

|

| The Capitol Building |

was too small, inadequately Roman Classic, and had an unacceptably burnable wooden dome, which was also too small. If the building was to be enlarged to its necessary size, the Bulfinch dome would be far too small, looking from afar like a Turkish pimple on a massive Roman auditorium. Walter proposed a technical solution: build the dome of cast iron. Transforming the North and South wings into mere galleries leading to much more massive Senate and House chambers, the whole building grew to usable size. All of this work nearly came to a stop in the Civil War, but Lincoln made the decision that the symbolism of continuing on was more usefully dramatic than the quibbles of distracting from the war effort. No doubt it was pointed out that all of that unfinished ironwork might rust uncontrollably if the war dragged on for several years.

|

| Philadelphia City Hall |

Walter liked to think big. He wore his long hair like a prophet in the wilderness and is reported to be somewhat difficult to get along with. His commission for Girard College was by far the most expensive architectural effort up to that time. Philadelphia City Hall, which he did not live to see completed, was intended to be the tallest building in the world. It would have been, too, expect delays due to political corruption allowed other buildings to get a few feet taller.

Friends of Boyd

|

| Boyd Theatre |

Howard B. Haas a lawyer, and Shawn Evans an architect, are captains of a team trying to "save" the old Boyd Theatre at 1908 Chestnut Street. Since Clear Channel, the present owner has invested $13million in the property, and the preservationists agree that renovation of the movie palace to all its former glory would cost between $20million and $30million more, it's easy to understand why every other movie palace in central Philadelphia has been demolished. Furthermore, that area of town is having a resurgence of high-rise construction, so one use of the property must be balanced against others.

|

| Sam Eric |

The Boyd was built in 1928, just before the stock market crash, and closed in 2002. In fact, it changed its name to SamEric in its dying days, but the public remembers it as the Boyd, one of ten movie palaces in center city. The definition of a "palace" is arbitrary but is generally taken to be a theater with more than a thousand seats, normally with hyperbolic architecture to fit its hyperbolic advertising. Scholars of the matter say the earliest movie houses were constructed in Egyptian style, soon evolving into French Art Deco. Ornate, whatever it's called.

The palace concept developed in the era of silent films, with subtitles. Anyone who has experimented with home movies knows that the silent film sort of lacks something, particularly between reels and at times of breakdown in the projection. That's why brass bands played on the sidewalk outside, pipe organs played during intermissions, and all manner of vaudeville appeared on stage. Sound movies, or talkies, were immediately much more popular when they appeared in 1927, and had less need of the window dressing from other distractions which had grown into a moviehouse tradition which was slow to die.

The movie studios owned the films and soon built theaters to display them. The movie business was quite profitable from the start, so studios had the necessary finance to spread a network of very large theaters across the country quickly. The ability to concentrate hyped-up advertising with immediate display of the product in large captive theaters tended to drive the model of the "palace", which was able to sustain higher ticket prices than trickling a larger number of film copies to myriads of small "mom and pop" local theaters. In very short order, going downtown to see movies became at one time the largest reason for suburbanites to go to the center of town on public transportation, fitting in nicely with the concentration of huge department stores, also located there. Restaurants, bars, bowling alleys, and shops grew up to address the crowds. Furthermore, the economic depression of the 1930s slowed down what was to become a relentless automobile-flight to the suburbs. After the spread of free television at home in 1950, the downtown movie palaces were doomed. The legal profession helped, too. Small suburban theater operators eventually won an antitrust suit against what they described as monopoly power of studio-owned center city palaces, so a host of small sharks in the suburbs started to eat the whales downtown. Furthermore, the sound quality was easier to achieve in a smaller auditorium. To tell the truth, fire hazard was also lessened without the arc-lamps needed to project images across a long distance.

So, a new technology interacting with an old theatrical tradition quickly created the movie industry in its downtown movie palace form; more advancing technology quickly destroyed it, with a little help from economics and politics. Good luck to the friends of this historical epoch, who have a monumental task ahead to work up the public nostalgia and political strength required to overcome a huge economic obstacle of the "highest, best use of the land". In many ways, the most valuable contribution of this movie palace restoration movement is to dramatize in the public mind just how urban centers function. Department stores are gone, going in town to the movies is over. How else are you now going to get the couch potatoes to go downtown voluntarily, and often? Just imagine ten palaces simultaneously filling up with several thousand suburbanites apiece, seven nights a week. Without those additional drawbacks on ample display in Atlantic City and Las Vegas, please.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1190.htm

Venturi's Franklin Museum in Franklin Court

|

| Franklin Court Museum |

When Judge Edwin O. Lewis was seized with the idea of making a national monument out of Colonial Philadelphia, he wanted it big. Forty or so years later, it's big all right, but not big enough to encompass the whole of America's most historic square mile. Government ownership in the form of a cross now extends five blocks north from Washington Square to Franklin Square, and four blocks East from Sixth to Second Streets. Restoration and historic display have spread considerably beyond that cross, however, and the Park Service has created ingenious walkways within the working city in the neighborhood. If you thread your way through these walkways, you can stroll for miles within the world of William Penn and Benjamin Franklin. One such unexpected walkway is now called Franklin Court, which essentially cuts from Market to Chestnut Streets, within the block bounded by 3rd and 4th Streets. Hidden in the center is the reconstructed ghost of Franklin's quite large house, sitting in an interior courtyard bounded by a colonial post office, and a newspaper office once operated by Franklin's grandson. And, along the side of the walkway near Chestnut Street, is a fascinating museum of Franklin's personal life, built by no less than Frank Venturi, and operated by Park Rangers in the polished but low-key manner for which the U.S. Park Service is famous.

For some reason, this jewel of a museum has not received the high-powered publicity it deserves. It's off the main Park premises, as we mentioned, and some of the problem has to be attributed to Venturi. As you walk through, you don't expect a huge museum to be there, and it can look pretty inconspicuous as you walk past because it is mostly underground. Take my word for it, it's worth a visit. There are long descending ramps inside the doors, which can be pretty daunting if you are elderly and tired. But, also inconspicuous, there's an elevator if you look around for it. Venturi didn't seem to like windows very much, which is a problem for some people.

There's a movie theater inside there, playing a long list of fascinating documentaries. There's an ingenious automated display of statuettes which utilize spotlights and revolving stages to present Franklin in Parliament, resisting the Stamp Act, Franklin being his charming self before the French monarchs, and the frail dying Franklin getting the Constitutional Convention to approve the document. There are also a variety of ingenious inventions of Franklin's on display in the original, including bifocal glasses, the first storage battery, a simplified clock, several library devices, the Franklin stove, and so on. In some ways, the highlight is the Armonica.

The Armonica is the musical instrument invented by Franklin, for which both Beethoven and Mozart composed special music to exploit its haunting tone. If you ask the nice Park Ranger, she will be flattered to play you a tune on it.

Quaker Gray Turns Quaker Green

|

| American Friends Service Committee Logo |

Miriam Fisher Schaefer, at one time the Chief Financial Officer of the American Friends Service Committee, had to cope with the economics of renovating the business headquarters complex for various central Quaker organizations. They're housed in a red-brick building complex, naturally, located on North 15th Street right next to the Municipal Services Building of the Philadelphia City Hall complex. The original building within the complex is the Race Street Meetinghouse, funds for which were originally raised by Lucretia Mott. The Quakers needed to expand and renovate their offices, a nine million dollar project. Miriam, a CPA, calculated that the job could be made completely environment-friendly for an extra $3 million. The extra 25% construction cost explains why very few buildings are as energy-efficient as they easily could be. However, in the long run, a "green" building eventually proves to be considerably cheaper. Not only would a green Quaker headquarters be a highly visible "witness" to environmental improvement, but it would also pay for itself in reduced expenses after about eight years. That is, if friends of the environment would provide $3 million in after-tax contributions, they would provide a highly visible example to the world, and reduce the running expenses of the Quaker center by a quarter of a million a year, indefinitely. Effectively, this is a charitable donation with a permanent tax-free investment return of 12%, quite nicely within the Quaker tradition of doing well while doing good.

|

| Rockefeller Center |

Energy efficiency isn't one big thing, it is a lot of little things. If you dig a well deep enough, its water will have a temperature of 55 degrees, and only require heating up another 15 degrees to be comfortable in winter, or cooling down thirty degrees to be comfortable in the summer; that's described as a heat pump. Then, if you plant sedum, a hardy desert succulent plant, on the roof it will insulate the building, slow down rainwater runoff, and probably never have to be replaced. Rockefeller Center, you might be interested to learn, has a "green roof" of this sort, which has so far lasted seventy years without replacement. The Race Street Meetinghouse was built in 1854 and has so far had many roof replacements, each of which created a minor financial crisis when the need suddenly arose.

The ecology preservation movement is full of other great ideas for city buildings because buildings --through their heating, ventilating and air conditioning -- contribute more carbon pollution to the atmosphere than cars do. For another example, fifty percent of the contents of landfills originate in dumpsters taking construction trash away from building sites. What mainly stands in the way of more recycling of such trash is the extra expense of sorting out the ingredients. Catching rainwater runoff allows its reuse in toilets, eliminating the need to chlorinate it, meter it, and transport it from the rivers. And so forth; you can expect to hear about this sort of thing with great regularity now that the Quakers have got stirred up. You could save a lot of air conditioning cost by painting your roof white. At first, that would look funny. But do you suppose oddness would bother the Society of Friends for one instant? No, and you can expect them to make it popular, in time. People at first generally hate to look funny, but with the passage of time they grow to like looking intelligent.

A lot of people want to save the planet. So do the Quakers, but they have come to the view that the public is more easily persuaded to save money.

Pennsbury Manor

|

| Fairmount |

William Penn once had his pick of the best home sites in three states, because of course he more or less owned all three (states, that is). Aside from Philadelphia townhouses, he first picked Faire Mount, where the Philadelphia Art Museum now stands. For some reason, he gave up that idea and built Pennsbury, his country estate, across the river from what is now Trenton. It's in the crook of a sharp bend in the river but is rather puzzlingly surrounded by what most of us would call swamps. The estate has been elegantly restored and is visited by hosts of visitors, sometimes two thousand in a day. On other days it is deserted, so it's worth telephoning in advance to plan a trip.

|

| Gasified Garbage |

After World War II, a giant steel plant was placed nearby in Morrisville, thriving on shiploads of iron ore from Labrador, but now closed. Morrisville had a brief flurry of prosperity, now seemingly lost forever. However, as you drive through the area you can see huge recycling and waste disposal plants, and you can tell from the verdant soil heaps that the recycled waste is filling in the swamps. It doesn't take much imagination to foresee swamps turning into lakes surrounded by lawns, on top of which will be many exurban houses. How much of this will be planned communities and how much simply sold off to local developers, surely depends on the decisions of some remote corporate Board of Directors.

However, it's intriguing to imagine the dreams of best-case planners. Radiating from Pennsbury, there are two strips of charming waterfront extending for miles, north to Washingtons Crossing, and West to Bristol. If you arrange for a dozen lakes in the middle of this promontory, surround them with lawns nurtured by recycled waste, you could imagine a resort community, a new city, an upscale exurban paradise, or all three combined. It's sad to think that whether this happens here or on the comparable New Jersey side of the river depends on state taxes. Inevitably, that means that lobbying and corruption will rule the day and the pace of progress.

Meanwhile, take a trip from Washingtons Crossing to Bristol, by way of Pennsbury. It can be done in an hour, plus an extra hour or so to tour Penn's mansion if the school kids aren't there. Add a tour of Bristol to make it a morning, and some tours of the remaining riverbank mansions, to make a day of it.

Wall Art in Philadelphia

|

| Seasons |

At last count, Mural Arts program of the city government of Philadelphia has sponsored and paid for 2700 large paintings on the walls of buildings around town, and several hundred more have appeared spontaneously. Comparatively few art museums have that many on display, so people are proud of the Philadelphia effort.

This program is now nearly thirty years old, beginning to emerge as a national treasure. Looking back, it is pleasing that it had humble, even deplorable, origins. As American cities lost their industrial focus, many homes in the neighborhood of former factories have been abandoned, getting torn down in random patterns. Industrial cities of the East Coast were tightly packed to save land costs and time commuting to work; the fashion of "row houses" evolved without any space between neighbors sharing a "party" wall. When a row house was torn down, there emerged a scabrous ghost, because the wallpapered interior walls were exposed and looked pretty hideous. It eventually became illegal to leave a scabrous building, leading to elaborate legal conventions about responsibility for the cost of covering exposed surfaces with concrete stucco. During the last half of the Twentieth Century, stucco was generally an improvement.

|

| Graffitti |

Meanwhile, during World War II it became clever for American military to inscribe "Kilroy was here" on unprotected public surfaces at home and abroad as a gesture of American triumphalism. Opinions differ about whether this started originally as an allusion to a certain line of 19th Century romance poetry, or whether there was in fact a John J. Kilroy, inspector of riveting in wartime shipyards, marking riveted materials with his name to enable piecework payment for shipyard tasks. Eventually, this Kilroy joke became a little tiresome, but soon was replaced by stylized decorations using cans of spray paint, until "graffiti" painting, in turn, became a public nuisance. It is true some graffiti artists were quite talented, but the associated vandalism of teenagers added a threatening quality to public defacement of property belonging to others. By implication, an area with graffiti was a home of lawlessness and that implication cast a negative shadow on the city economy. Public opinion demanded something effective be done to stop it.

|

| Frank Sintra |

Since graffiti vandalism has declined nationwide in the past twenty years, it is difficult to claim that one public initiative in Philadelphia cleaned it up. But it might be true. Then-Mayor Wilson Goode formed an antigraffiti Network, essentially a think tank for concerned citizens, floundering about for a solution to an appalling problem. Somehow the inspired idea arose that the graffiti artists might be channeled into better directions if given professional art lessons, and working materials. A West-Coast artist named Jane Golden was hired to supervise what has become a multimillion-dollar project, overseen by some sort of guiding hand pushing the whole city into becoming part of a gigantic art project. Guides tell visitors that there are fifty employees involved in publicity and legal work, organizing artists, fundraising, organizing teams of painters at all levels of competence, helping oversee the general appropriateness of what is happening. And at the head of this team is Jane, a tornado of energy.

|

| Frank Rizzo |

It costs forty to seventy thousand dollars to produce one of these works, and since they are exposed to the weather, they only last about fifteen years. There are several techniques for transforming a small artwork into a big outdoor copy, some of them tracing back to Michaelangelo. Most of the Philadelphia murals are produced by dividing the original small artwork into squares and transferring numbered squares to the wall, one inch to one foot. As you can see by reviewing some of the websites devoted to the topic, a piece of art which is quite appealing can sometimes change into a drab mess when its size is blown up to three-story height. The problems of lighting such work are quite different from the lighting of a gallery painting. The surface is seldom smooth, so the bumps and grooves of the underlying scabrous "canvas" can destroy, or sometimes dramatically enhance, a salon painting. If you get too close, you can't see all of it, and that may be a problem. It's probably not entirely predictable what will come out in the final product.

There are inevitably political problems as well. The best examples are the several paintings of former Mayor Frank Rizzo, who is a hero to the Italian neighborhoods where they stand, but provoke riotous feelings in near-by black districts. Luck alone has confined the antagonisms to graffiti on the murals, viewed by some groups as enhancements on what begins as graffiti. No wonder the committees assigned to approving locations can take a long time to come to a decision.

There's another problem, which seems to be embedded in the situation. In the central city skyscraper district, you don't have scabrous buildings. Nor can mural art be placed in the historic square mile. Just a few blocks in either direction from central city there are plenty of demolitions and scabrous walls, but, close to downtown, these are areas of gentrification and urban renewal. It doesn't make sense to spend fifty thousand dollars to paint a wall which will be demolished in two or three years. The net effect is that the city may have three thousand paintings all right, but only fifty at most are within a tourist ride of Independence Visitors Center. If half of these fifty are concerned with celebrating local heroes unfamiliar to tourists, there can be disappointment which would disappear if a selection of fifty outstanding products could be culled from three thousand -- and grouped together for exhibition.

A solution to these issues will surely emerge with time, but it will evolve, not be envisioned.

Unexpected Benefits of a Lurid Past

|

| Map of Barnegat Bay |

Centuries came and centuries went, while a Quaker shipyard went on about its business along the shore of Barnegat Bay. Next door there was a notable roadhouse after the second World War, rumored to have formerly been a secret speakeasy during the days of Prohibition. In time, the only occupant of the roadhouse was a wealthy widow, who mostly minded her own business and grew to be an affable neighbor to the Quakers next door. As rowdy days of Prohibition faded into the background of decades past, the old lady felt free to recall some of the less tawdry features of her past, to the Quakers who in turn felt free to chuckle about them. Ancient history, perhaps a little varnished and polished up. It was, however, a little disquieting to hear her say that the liquor for the speakeasy was often supplied by sailors from the Coast Guard, who routinely diverted 20% of the cargo of rum Runners they had captured, into commercial channels. Exciting times, those were.

|

| The Coast Guard out looking for Rum Runners |

One day when the widow was ninety-six years old, the lights of her house stayed on, without other signs of activity. The neighbor eventually walked over to the back door and looked through the window, where it could be seen that the old lady was lying on the floor, rather motionless. He might have called the police, or broken into the house, but there was another option.

He went down to the basement, entering a rather dusty but quite elaborate barroom. Following old directions, he walked to a closet and climbed up a stepladder leading into another closet on the floor above. Stepping out, he found the lady was still breathing, called her relatives, and watched her be taken off to a nursing home to end her days. No one seemed to ask very many questions.

Sacred Places at Risk

|

| Old St. Joe's |

When William Penn invited all religions to enjoy the freedom of Pennsylvania, he created a home for the first churches in America of many existing religions, and furthermore the founding mother churches for many new religions. Regardless of the local congregation, there is obviously a strong wish to preserve the oldest churches of the Presbyterian, Methodist, United Brethren, African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist, Mennonite, and many other denominations. While the founding church of Roman Catholicism was obviously not in Philadelphia, St. Josephs at 3rd and Willing was for many decades the only place in the American colonies where the Catholic Mass could be openly performed. The towering genius of William Penn lay in the combination of an almost saintly wish to spread religious toleration, combined with what must have been a sure recognition that the motive of Charles II in giving him the land, was to get rid of all those dissenters from England.

Philadelphia now has a thousand church structures within the city limits, and more than a thousand in the suburbs. However, many church buildings find themselves stranded by the migration of local ethnic groups to other locations, and a decision must be made whether to demolish a relic or sell it to a new population who have moved into the old neighborhood with a new religion. There is still greater discomfort with selling an old church to a commercial enterprise, but even that happens. The resulting bewilderment and dissension among the surviving parishioners is easy to imagine as they face these choices, or fail to face them, and it is readily imagined that the establishment in 1989 of Partners for Sacred Places filled a very important need.

|

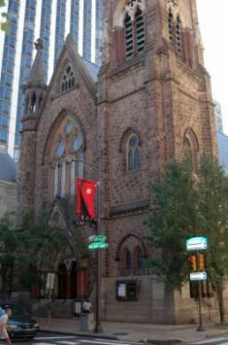

| First Presbyterian Church |

The Executive Director, Robert Jaeger, recently described to the Right Angle Club how the Partners operate. First of all, the Constitutional separation of church and state makes it difficult to seek funding or even advice from the Federal government. Pennsylvania has been less hesitant than most states in this regard, but even here the issue of fund-raising is a central issue. One only has to look at the Aztec and Mayan religious sites in Mexico to grasp that there are circumstances when the parishioners of a religion may have completely died out, but their monuments justify state assistance. Private, nondenominational philanthropy seems the easiest route for a society to take, in avoiding the obvious political and legal entanglements of seeming to assist one denomination more than others.

And then there are architectural issues;, can the building be saved at a reasonable cost, is it truly a unique or outstanding piece of art, can a reconstruction go ahead in an incremental way, are the necessary stone or other materials any longer obtainable, do the workman skills exist? In addition to these issues which are commonly presented to a congregation, there are issues they probably have never considered. As congregants move from center-city to the suburbs, they become commuters to church, largely out of touch with the local community and its activities. A survey conducted by the Partners suggests that 81% of the activity which takes place in church buildings on weekdays is conducted by and for non-members of the church; if the two groups lose touch with each other, opportunities are missed, and eventually there may be unnecessary friction. On the other hand, those non-religious activities probably escape the legal prohibitions against government assistance, and may suit themselves as vehicles for indirect government support. The approach has so much promise that Partners for Sacred Places has devised a computer program on their website which provides a way for congregations to assess their assets, and their problems. In fact, the organization conducts extensive training programs for church preservation, and has been forced by the size of the demand to exclude churches that are clearly failing beyond reasonable hope of recovery by their church membership.

The Partnership was originally founded by consolidation of the New York and Philadelphia organizations, to make a stronger national effort. But now things are going the other way. New chapters are springing up in Texas and California. Partners for Sacred Places is obviously proving to be a good idea, effectively managed.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1269.htm

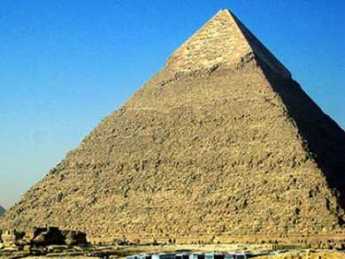

The University Museum: Frozen in Concrete

|

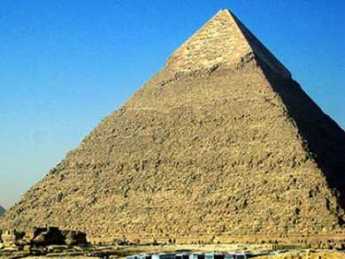

| King Tut |

Recently, a charming archeology scholar from the University of Pennsylvania, Leslie Ann Warden, entertained the Right Angle Club with the interesting history of King Tut. Interest in this subject is currently heightened by a traveling exhibit of the tomb relics currently on elegant display at the Franklin Institute. However, Philadelphia also has a permanent exhibition of Egyptian artefacts lodged in the University Museum. Since this museum is the second largest archaeology museum in the world, after the British Museum, that makes it the largest in America. An interesting sidelight is that Ms. Warden spoke in the grill room of the Racquet Club, which was the first effort by William Mercer to use "Mercer" tiles in a building. Mercer at that time was the curator of the University Museum. We learned from Ms. Warden that King Tutankhamen was unknown before his tomb was discovered, all records of this part of the Egyptian dynasty having been lost or deliberately obliterated by successors. Therefore, the discovery of these magnificent art objects started a massive expansion of scholarship about the entire Third Millenium.

|

| William Pepper |

The establishment of the University Museum around 1890 was apparently mostly due to the enthusiasm of William Pepper, then Provost of the University of Pennsylvania. What seems to have got Pepper going was an expedition to Iraq, the place where civilization began, in Mesopotamia. The relics brought back from this celebrated effort needed a home, and Pepper decided it had to be here. One famous philanthropist after another, often in the role of Chairman of the Board of Trustees, carried on the tradition after Pepper's premature death. Some of them have their names on buildings, some declined. To a notable degree, the feeling of special possession was exemplified by Alexander Stirling Calder, who turned the statues in the garden to face inward rather than out toward the street. Asked whether a mistake had been made, he is said to have replied that due to the Museum's withdrawn character, it was more appropriate for the world to face the Museum. No more icily accurate comment has ever been made about the University's relation to its city neighbors.

The real knock about the Museum is that too much has been crowded into too little real estate, and the fault lies with the automobile. After the University outgrew its space at 9th and Market around 1870, moving then to West Philadelphia, the architects and the donors originally envisioned a grand boulevard of culture stretching from the South Street bridge many blocks westward. The Museum, Franklin Field, Irvine Auditorium, The University Hospital were to be the start of an imposing array of culture. Unfortunately, that was a horse-drawn conception, soon to be overwhelmed by the worst traffic jam in the city. The Schuylkill Expressway was the final blow, setting huge auto-oriented structures in place where their easy removal became difficult to imagine. The 1929 stock crash, followed by confiscatory income and estate tax rates, merely emphasized the plain fact that restoring the grand vision was beyond the ordinary aspirations of even massive private wealth. Transforming the imposing plazas of the University Museum into parking garages was probably a result of excessive despair, but if you have ever tried to find a place to park in that region you can somewhat sympathize with the small-mindedness which prompted it. Bringing back this region is going to require immense vision and resources, neither of which is exactly thrusting itself forward at present. So, unfortunately, one of the central cultural jewels of the City is buried in the midst of an impenetrable thicket of concrete and speeding automobiles, too big to move, too small to burst its bonds.

It's well worth a lot of anybody's time, and many visits. If you can find a way to get there.

Beyond Most of Us

|

| Louis I. Kahn |

The Athenaeum is slowly migrating into a national historical museum of American architecture. In this spirit, it recently presented a lecture by Carter Wiseman of Yale on the subject of Louis I. Kahn to an overflow audience. Professor Wiseman drew his remarks from his recent book about Kahn, called Beyond Time and Style.

Many giants of Philadelphia architecture, like Strickland and Walter, are known to us for the memorable public buildings they designed, but Kahn and Venturi are known for their scientific contributions to the theory of architecture. Their reputations were consequently made among architectural scholars, and then passed on to the public in the form of praise that is a little hard for laymen to understand. For example, Wiseman begins his course on Kahn by telling the students they probably will not understand Kahn at the beginning of the course, but all will revere him by the end of it. The rest of us, of course, have not attended the lectures, and a reciprocal effect probably has something to do with Kahn going to his grave, deeply in debt. No doubt the additional fact that he had three families with three women simultaneously, somewhat strained his cash flow as well.

|

| Richards laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania |

Kahn encountered the architectural field toward the end of the period of Modernism, which he referred to as "machines to live in". Rather than overturn the whole idea of Modernism, he softened its harshness through ingenious use of interior lighting, and the use of rough rather than smooth shiny materials. His teaching was that closets, elevator shafts, corridors and the like were "servant" spaces, to be hidden and subordinated to "served" spaces, like reception areas. The overall effect was a deceptive simplicity, often regarded by the public as simple boxes when the underlying design was anything but simple. For some reason, the concepts of rough surfaces and subordinated spaces was particularly effective in India and Pakistan. It was least popular in his two famous American laboratory buildings, the Richards laboratory of the University of Pennsylvania, and the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Both of these laboratories were widely praised by architects, and resoundingly hated by the chemists who used them, because chemists are particularly fond of closets. He does have one group of particular enthusiasts among those who own and inhabit the tall glass office buildings which became so popular after the Seagram's tower on Park Avenue in New York. Washing all that glass is a problem and surfaces which don't look dirty so soon, gain advantage.

Professor Wiseman spared his audience the story of Kahn's death, presumably because it is so well known. He died in the washroom of Penn Station in New York, and his body lay unidentified in the morgue for three days. It is supposed that someone stole his wallet with identification papers, because there couldn't have been much else in it to steal.

Germantown Avenue, One End to the Other

|

| Germantown Map |

Chestnut Hill really is a big hill poking up in the middle of Philadelphia, and Germantown Avenue follows an old Indian trail from the Delaware River right up to that hill. The waterfront area of the city has been built and rebuilt to the point where it's now a little hard to say just where Germantown Avenue begins. From a map viewpoint, you might look for a four-way intersection of Frankford Avenue, Delaware Avenue, and Germantown Avenue, underneath the elevated interstate highway of I-95. The present state of demolition and rubble heaps suggests that a Casino might be built there sometime soon, politics and the Mafia permitting.

|

| Fair Hill Cemetery |

Although Germantown Avenue has wandered northwestward from this uncertain beginning for over 300 years, up to the rising slope of the town toward Broad Street, it is now rather difficult to make out anything but industrial slum along its path which could be called historic. There is hardly any structure standing which has a colonial shape, and no Flemish bond brickwork is seen in the tumble-down buildings. When with the relief you finally approach Temple University Medical Center at Broad Street, the Fair Hill cemetery does show some effort at preservation, and a sign says that Lucretia Mott is buried there. But that's about all you could photograph without provoking suspicious stares. Here's the first of four segments of Germantown Ave., and it's a pretty sorry sight.

|

| Chew Mansion |

Crossing Broad Street, the busy intersection suggests 19th Century prosperity in its past, and on the west side of Broad, you can start to see signs of historic houses, either in colonial brickwork or grey fieldstone. The road gets steeper as you go west past Mt. Airy, where it almost brings tears to the eyes to see brave remnants of another time. George Washington lived here for a while, and the Wisters, Allens, and Chews; Grumblethorp and Wyck. The huge stone pile of the Chew Mansion glares at the imposing Upsala mansion, where British and Americans lobbed artillery at each other during the Battle of Germantown. Benjamin Chew the Chief Justice built this house as a summer retreat, to get away from Yellow Fever and such, and started the first migration to the leafy suburbs. His main house was on 3rd Street in Society Hill, next to the Powels and where George Washington stayed. At the peak of the hill in Chestnut Hill, a suburb within the city. Germantown Avenue rather abruptly goes from the relics of Germantown to the charming elegance of Chestnut Hill, but during a recession, it frays a little even there. At the very top is the mansion of the Stroud family, now in the hands of non-profits; across the road in Chestnut Hill Hospital, once the domain of the Vaux family. Then down the hill to Whitemarsh, where the British once tried to make a surprise raid on Washington's army. As you cross the county line into Montgomery County, it's conventional to start calling the Avenue, Germantown Pike. Germantown Pike was in fact created in 1687 by the Provincial government as a cart road from Philadelphia to Plymouth Meeting. Farmers used to pay off their taxes by laboring on the dirt road, at 80 cents a day. Germantown Pike, Ridge Pike, Skippack Pike, Lancaster Pike, and others are a local reminder that Pennsylvania was always the center of turnpike popularity; that's how we thought roads should be paid for. The present governor (Rendell) hopes to sell off some better-paying turnpikes to the Arabs and Orientals, possibly imitating Rockefeller Center by buying them back and reselling them several times by outguessing the business cycle. Parenthetically, the Finance Director of another state at a cocktail party recently snarled that the purpose of privatizing state infrastructure was not to raise revenue, but to provide collateral for more state borrowing. He wasn't at a tea party, but he may soon find himself there.

From a modern perspective, the third segment of the Germantown road runs from Chestnut Hill to Plymouth Meeting, with lovely farmhouses getting swallowed up by intervening, possibly intrusive, exurbia. The township of Plymouth Meeting is a hundred years older than Montgomery County, having been built to be near a natural ford in the Schuylkill River. Norristown, a little downstream, is the first fordable point on the Schuylkill, with Pottstown making a third. Plymouth's colonial character survived a period of industrialization based on local iron and limestone, and has established several prominent schools for the surrounding area. But the construction of a substantial highway bridge attracted a large and busy shopping center. The shopping center looks as though it will eradicate the quaint historical atmosphere more effectively than industrialization ever could.

The fourth and final segment of Germantown Pike starts at the Schuylkill and goes over rolling countryside to its final destination at Perkiomenville, where it joins Ridge Pike at the edge of the Perkiomen Creek. That's an Indian name, originally Pahkehoma. Perkiomenville Tavern claims to be the oldest inn in America, although that honor is contested by another one along the Hudson River near Hyde Park. The WPA during the Great Depression constructed a large park along the Perkiomen Creek for several thousand acres of camping and fishing, so Perkiomenville has several large roadhouse restaurants and antique auctions for bored wives of the fishermen. In the V where Ridge Pike and Germantown Pike come together, a dozen or more colonial houses are tucked away in a town called Evansburg. This formerly Mennonite terminus of Germantown Pike obviously still has a lot of charm potential, and its local inhabitants are very proud of the place. But it's easy to zip past without noticing the area, which includes an 8-arch stone bridge, said shyly to be the oldest in the country. It's hard to know whether you wish more people would visit and appreciate; or whether you are happy that obscurity might permit it to survive another century or so.

|

| Chestnut Hill Hospital |

The name change of the Germantown road from Avenue to Pike is probably not precisely where the turnpike began, but it is now notable for some pretty imposing mansions, standing between the humble and even somewhat dangerous slums along Delaware, and the charmingly humble but well-preserved Mennonite villages, at the other end. It is arresting to consider the two ends, whose houses were built at the same time; only the Mennonites endure. Somewhere just beyond the Chestnut Hill mansions is an invisible line. West of that point, when you say you are going to town, you mean Pottstown. When you say you are going to the City, you mean Reading. And as for Philadelphia, well, you went there once or twice when you were young.

Trapped in a Casino

Everyone who reads a detective novel or sees a James Bond movie is familiar with secret passages and hidden protection devices that suddenly trap the unwary. You aren't supposed to know about these things, but in real life, lots of people have had to know the secret, because it takes builders, architects and workmen to create it. Ancient Chinese and Egyptian emperors may have buried workmen alive to preserve the secret of secret passages, but nowadays that sort of thing is discouraged.

|

| Gambling |

Since nowadays gambling casinos are bought and sold like a bottle of milk, some of the people who just have to be told the secrets of casinos are real estate appraisers; from one of them, the following tidbit derives. Casinos try not to have any windows, so the serious slot machine players won't notice the passage of time, and maybe gamble all night when so inclined. It is, therefore, no surprise the ceilings and walls are usually mirrored, to make these windowless caverns seem gay and cheerful. The casino operator doesn't want anyone to go home for any reason other than running out of money, and depends heavily on the wisdom of Adam Smith, who once said, "The more you gamble, the more certain you are to lose."

|

| Adam Smith |

Unfortunately, these palaces of pleasure attract a fair number of cheaters, who attempt to win by memorizing the cards that have been played and changing their bets with the changing odds of what remains unplayed in the deck ("card counters"). Others are more mechanically talented and drill holes into the works of slot machines with battery-driven portable drills, for later accomplices to insert metal rods into vital wheels and whatnot on the inside. And so on. So, the mirrors on the ceiling are one-way mirrors, with people observing what goes on below, and cameras recording every action of everybody. In this modern age, some casinos can bring up videos of what happened on a particular machine at a given time, several years ago. This elaborate recorded surveillance can be used to unravel the activities of visiting crooks, who quite often do their work over a period of some time, coming back to the same machine for another step in their fiendish schemes. Now, there's another consideration at play here. The casino operator does not want a commotion on the gambling floor when some crook is accosted, because that tends to divert dozens of gambling addicts from their incessant gambling in order to watch the excitement. This would definitely be a violation of Adam Smith's law of gambling, and hence would subtract from the value of stopping the crook who was caught. No good.

|

| Casino Video Surveillance |

So, the merry men up above on the other side of the mirrored ceiling will merely watch and record the activity of the miscreant below, apparently letting him get away with it. But sooner or later the crook has stolen enough or has to go the bathroom, or for some other reason leaves the casino floor. Bang, the door behind him closes and locks, and the door on the other side of the trap is also locked. Thus, without any fuss or muss (maybe) the crook is observed by witnesses, recorded on camera, and tucked away in a security chamber until such time as the security guards can arrive to advise him of the management's disapproval of his behavior. Just exactly what does happen when one of these people is caught is not something they need to tell a real estate appraiser, so, unfortunately, I have to leave it to your imagination.

Roebling

|

| John Roebling |

The common image of John A. Roebling comes across a little hazy about details, but seems to consist of going down with the Titanic at the age of 31, with being born in Prussia in 1837, with getting the "bends" while building the Brooklyn Bridge, and first sighting General Robert E. Lee's invading army from a balloon, then dragging a cannon up Little Round Top. The obvious inconsistencies in this image do not prove they are fictitious, they prove that Roebling was several people. Mostly this composite centers on Johann Augustus Roebling and his three sons, but spreads out to a large and highly talented family. Roebling achievements are not those of a bee, but of a beehive.

Johann was a younger child in a large Prussian family living a hundred miles south of Berlin. The region had been ruled under Napoleon for seven years, creating much of the centralized governance we now call "Prussian". Following centralized orders, its school had been designated to be an expert in science and engineering. Johann was particularly good at math and was singled out for intensive training in math and science, later sent to Berlin for advanced training in engineering. While there, he fell under the influence of the philosopher Hegel, who proclaimed that anyone could be anything he wanted to be, but opportunities were particularly good in America. Since Berlin went on to become the world center of electrical engineering, the world would probably have heard more of Johann Augustus Roebling even if he had remained at home; but he was going to do big things in the steel industry, so off he went to Pittsburgh. Things went rather well for him there, especially after he substituted wire rope for hemp rope in pulling canal boats over the Allegheny mountains. From that point on, John A. Roebling concentrated on perfecting and manufacturing wire cable, on which he held several key patents, and moved his business to the head of the Delaware Bay at Trenton, strategic in sales location between New York and Philadelphia.

|

| Wire Rope Factory |

Although his company would eventually build an open hearth steel mill, the Roebling enterprise always retained a central focus on steel cables made of steel wires bound together for flexibility and strength. The plant next door in Trenton, the Cooper, Hewitt Co., created the steel I-beam and thus was central in the construction of skyscrapers. Roebling supplied steel cable for elevators, without which skyscrapers would have been limited to six or eight stories. The wires within the cables start from what we can now visualize as the child's toy Slinkies (also a Roebling product, by the way). The trick to making such coils into cables was to find a way to straighten them out, which Roebling devised and patented, using a wheel arrangement to twist the wire as it unwound. Later, the wires were galvanized and compressed together. If the cables were used to carry electricity, it was necessary to cover the cable with rubber insulation as part of the manufacturing process. Eventually, over fifty different processes needed to be perfected and employed to create large quantities of non-brittle uniform cable product at low prices. Apparently, the central problem in manufacture was to smooth off burrs in the wire and meanwhile keep the assembly scrupulously clean. Roebling learned how to overcome all of the many problems in this deceptively simple-looking process, which eventually meant that the main problems remaining were in designing factories rather than designing cables. During the taming of the west, he produced barbed wire; during the rise of mass agriculture, he devised ways to use wire binders for sheaves of wheat. During the rise of electricity, he provided insulated wire and cable, first for the telegraph and then for the telephone. He even recognized the best business model; make huge profits during the first few years of a new product, then cut prices. By far the most famous product of the Roebling company was the suspension cable in suspension bridges.

Indeed, many people associate the Roebling name with bridge building, even though wire cable was and continued to be the central activity of the company. It was characteristic of the Roebling energy and engineering skill that he saw that if he wanted to sell cable, he had to show others how to use it, and he essentially took over the design and construction oversight of the twelve largest suspension bridges in the country. Unfortunately, his foot was crushed in a construction accident and when he died, the building of the Brooklyn Bridge had to be turned over to his son Washington Roebling. Washington, in turn, became badly crippled by caisson disease, the "bends", and hands-on oversight was conducted in large part by his wife, following meticulous instructions by her partially blinded husband.

|

| Brooklyn Bridge |

The work of building and designing factories for the company fell to Washington's brother Charles, and since the company was constantly changing focus in order to exploit new product lines, it was a prodigious task, always under time pressure. What's more, the main factories burned to the ground at least six different times, probably from arson in at least several cases. The Roeblings all worked like dogs for endless hours, well into old age. There was comparatively little ostentatious display of wealth, and when US Steel offered to buy them out, they declined an offer equivalent to one-fifth of the value of US Steel itself. That was during an economic downturn; Roebling was probably worth half of the value of US Steel. Andrew Carnegie might sell out, but not the Roeblings.

George Washington once reversed the Revolutionary War just up the street from the Roebling plant, and John Roebling's son was named after him. Roebling was a patriot and an active Republican. But there was enough Prussian in him to prefer German workmen and to hate unions. When the company grew large, he was forced to hire immigrants from what he called the Hapsburg Empire, although he never completely trusted them. Judging from his writing, he regarded unions as merely trying to take away control of the company without investing in it, certainly without earning it. Surviving numerous fires, recessions, and wartime demands for expansion without profit, it was plainly obvious that when times were tough and money had to be raised, there was no one except the owner to produce it. It is not difficult to imagine the hatred in the minds of union leaders, confronting a family that regarded lowered wages during the depression as normal and necessary. In the Roebling view, standing up to worker protests in such circumstances was simply a test of character, something an owner simply had to find the courage to do.

|

| Roebling Village 1930 |

When it became necessary to build a huge new plant at some distance downriver, the Roeblings had to contend with a shortage of labor in a region without houses. So they built a company town which they declined to name Roebling but the railroad named the stop Roebling anyway. Using engineering skill that had made Roebling the world leader, the homes were inexpensive but elegant for the time and even today. The company had to build stores, streets, schools, and everything else a town needed. The new headaches of this project took time and attention away from the central business of making steel cables, and Washington Roebling once wrote it was enough to drive you crazy.

So, guess what, the unions felt they had to take the lead in complaining and forcing the Roeblings to make changes. Guess what happened next; the Roeblings just sold it and walked away.

REFERENCES

| The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills That Shaped the American Economy, Hardy Green ASIN: B003XKN7MW | Amazon |

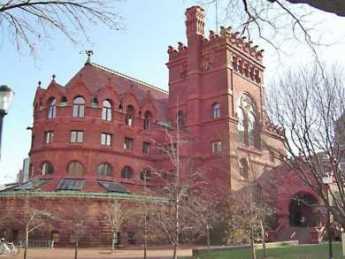

Frank Furness,(3) Rush's Lancer

|

| Frank Furness |

Lunch at the Franklin Inn Club was recently enlivened by David Wieck, who not only does the sort of thing you get an MBA degree for but is also a noted authority on the Civil War. His topic was the wartime exploits of Frank Furness, whose name is often mispronounced but whose thumbprints are all over the architecture of 19th Century Philadelphia. Take a look at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy, the Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania, and many other surviving structures of the 600 buildings his firm built in 40 years. One of them is the Unitarian Church at 22nd and Chestnut, where his grandfather had been the fire-brand abolitionist minister.

|

| PennsylvaniaAcademy of Fine Arts |

The Civil War seems to have transformed Frank Furness in a number of ways. He had been sort of in the shadow of his older brother Horace, a big man on the campus of Princeton, later the founder of the Shakspere Society, and the Variorum Shakespeare. Frank was quiet, and good at drawing. However, at age 22 he was socially eligible to join Rush's Lancers, the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry, which contained among other socialites the great-grandson of Robert Morris, and a member of the Biddle Family who put up the money to equip the troop with 7-shot repeating rifles. Cavalry units like this were a vital weapon in the Civil War because they needed young well-equipped expert horsemen with a strong sense of group loyalty. Rifles were considered too expensive for infantry, who were equipped with muskets that took several minutes to reload, and were unwieldy because they were only accurate if they were very long. When bands of daredevils on horseback suddenly attacked with seven-shot repeating rifles, they could be devastating against massed infantry. A flavor of their bravado emerges from their rescue of General Custer's men from a tight spot, later known in the annals of the troop as "Custer's first last stand."

|

| The Undine Barge Club Boathouse #13 of the Schuylkill Navy |

There are two famous stories of the exploits of Frank Furness, first as a second Lieutenant and later as a Captain at Cold Harbor two years later. In the first episode, a wounded Confederate soldier lay on the no man's land of forces only a hundred yards apart. His screams were so heart-rending that Furness ran out to him and put a handkerchief tourniquet around his bleeding thigh. Because the fallen man was a Confederate soldier, the Confederates held their fire and later cheered the Union cavalryman for his kindness. The wounded man called out "

|

| The Fisher Building of the University of Pennsylvania |

In the second episode, the cavalry had spread out too much, leaving some isolated parties trapped and out of ammunition. Furness lifted a hundred-pound box of ammunition to his head and ran through the gunfire with it to the trapped men. For this, he later received the Congressional Medal of Honor. Somehow all of the public attention he received in the war transformed Furness from a younger brother who was good at drawing into a dynamo of energy, much in the model of what law firms call a "rainmaker". He traveled to the Yellowstone area of Wyoming at least six times, bringing back various trophies. He was known to get people's attention by using his service revolver to take pot shots at a stuffed moose head in his office.

|

| First Unitarian Church 22nd Chestnut Philadelphia |

His final publicity venture was to advertise, forty years later, in Southern newspapers for the whereabouts of the Confederate soldier whose life he had saved. Eventually, a man named Hodge who had later been a sheriff in Virginia, stepped forward to renew his blessings and thanks. Hodge was brought to Philadelphia for a celebrated 6th Cavalry reunion, and a picture of the two former enemies was spread in the newspapers. It was a little embarrassing that Furness and Hodge found they had very little to say to each other for a five-day visit, but Hodge eventually proved able to be one-up in the situation. He outlived Furness by five years.

Although the style of Furness confections seemed and seems a little strange to everyone except Victorian Philadelphians, he did leave a major stamp on American architecture. His most noted student was Louis B. Sullivan, who put an entirely different sort of stamp on Chicago. And Sullivan's best-known student was Frank Lloyd Wright who created a modernist image of architecture for the West. The buildings of these three don't look at all alike, but their rainmaker personalities are all essentially the same.

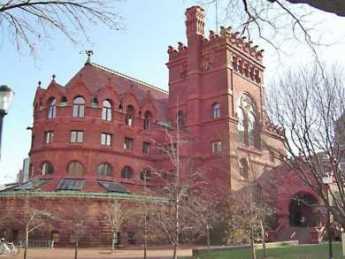

Frank Furness (1):PAFA

|

| Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts |

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art is notable for its place in Art history, for its faculty over the centuries, and for its influential student graduates. It is therefore not to slight the institution's remarkable place in the world of art if we pause to notice that the building itself, the place that houses all this, is itself an outstanding work of art. Whenever mention is made of Frank Furness, its colorful and influential architect, the first stop on the list is the building he built to house a school and display its glories. Perhaps the best way to illustrate the achievement is to compare it with the Barnes Museum, which also was built to house a school. It also has an outstanding permanent collection, perhaps a greater one than PAFA. But the Barnes building scarcely gets a mention and is about to be abandoned for a preferable location. The Furness building, however, is a massive pile of solid rock, immovable throughout massive changes in its neighborhood. To move that building out to the Parkway has never even been suggested. You can move if you like; we were here first.

The exhibition rooms are interesting, even clever, but the hand and mind of the architect are best seen in the school, the Academy. Seldom seen by the public, the entrance to the school is underneath the front staircase which sweeps the public visitors off to see the exhibition. Up to the stairs, admire the carved walls, the massive supports and the iron railings and out into rooms with scarlet and gold walls, and a blue ceiling with stars. When it leaves, the public sweeps back down the inside stairs and out the tunnel-like entrance, then down the outside stairs. Where was the school?

|

| PAFA Marker |

It's underneath the exhibition area, reached by a door under the stairs, unnoticed unless you ask for it. There you will find a darkened lecture hall and corridors lined with plaster casts for teaching purposes. But an artist's studio must have diffused northern light, and lots of it; the problem for the architect was to provide a huge slanted northern skylight over a basement. This trick was accomplished by pushing the walls of the first floor out to the street and installing a slanted skylight in the "ceiling" of the overhang. When the overall effect is that of a fortress meant to defend against a barbarian invader, built with massive walls and roof -- hiding a glass skylight is quite an achievement. Furness was a showman; it was not beyond him to place an architectural tour de force right in front of generations of students looking for something to portray.

We are told the building was five years in construction, designed and re-designed as it rose. The resulting effect is achieved by building around its interior as it evolves from bottom to top. Quite a difference from buildings laid out in advance, forcing the interior contents to conform to the initial design without regard to cramming down its contents. There is an overall design at work here; it's evocative of a Norman church with side extensions, but you have to look for that rather than having the architect thrust it in your face.

Frank Furness (2) Rittenhouse Square

|

| Frank Furness |

George Washington had two hundred slaves, Benjamin Chew had five hundred. It wasn't lack of wealth that restrained the size and opulence of their mansions, particularly the ones in the center of town. The lack of central heating forced even the richest of them to keep the windows small, the fireplaces drafty and numerous, the ceilings low. Small windows in a big room make it a dark cave, even with a lot of candles; a low ceiling in a big room is oppressive. Sweeping staircases are grand, but a lot of heat goes up that opening; sweeping staircases are for Natchez and Atlanta perhaps, but up north around here they aren't terribly practical. Building a stone house near a quarry has always been practical, but if there is insufficient local stone, you need railroads to transport the rocks.

|

| Early Victorian |

So to a certain extent, the advent of central heating, large plates of window glass, and transportation for heavy stone and girders amounted to emancipation from the cramped little houses of the Founding Fathers. Lead paint, now much scorned for its effect on premature babies, emancipated the color schemes of the Victorian house. Many of the war profiteers of the Civil War were indeed tasteless parvenu, but it is a narrow view of the Victorian middle class to assume that the overdone features of Victorian architecture can be mainly attributed to the personalities of the Robber Barons. This is not the first nor the only generation to believe that a big house is better than a small one. The architects were at work here, too. It was their job to learn about new building techniques and materials, and they were richly rewarded for showing the public what was newly possible. Frank Furness was as flamboyant as they come, a winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor for heroism, a man who wore a revolver in Victorian Philadelphia and took pot-shots at stuffed animal heads in his office. He affected the manners of a genius, and his later decline in public esteem was not so much disillusion with him as with the cost of heating (later air-conditioning), cleaning, and maintenance which soon exceeded provable utility. The simultaneous arrival of the 1929 financial crash and inexpensive automobile commuting to the suburbs stranded square miles of these overbuilt structures. It was the custom to build a big house on Locust, Spruce or Pine Streets, with a small servant's house on the back alley. During the Depression of the 1930s, there were many families who sold the big house and moved into the small one. Real estate values declined faster than property taxes and maintenance costs; incomes declined even faster.

|

| Delancey Street |

It thus comes about that large numbers of very large houses have been sold for very modest prices, and the urban pioneers have gentrified them. You can buy a lot of house for comparatively little if you are willing or able to restore the building. We thus come back to Frank Furness, who was the idolized architect of the Rittenhouse Square area, in addition to the massive banks and museums for which he is perhaps better known. Unfortunately, most of the Furness mansions on the square have been replaced by apartment buildings, but one outstanding example remains. It's sort of dwarfed by the neighboring high-rises, but it was originally the home of a railroad magnate, a few houses west of the Barclay Hotel, and it holds its own, defiantly. Inside, Furness made clever use of floor-to-ceiling mirrors to diffuse interior light and make the corridors seem wider. Although electric lighting made these windowless row houses bearable, modern lighting dispels what must have been originally a dark cave-like interior on several floors, held up by poured concrete floors. Furness liked to put in steel beams, heavy woodwork, and stonework, in the battleship school of architecture. If you were thinking of tearing down one of his buildings, you had to pause and consider the cost of demolition before you went ahead.

|

| Frank Furness Window |

There are several others of his buildings around the corner on the way to Delancey Street, one of them set back from the street with a garden in front. That's what you expect in the suburbs, but the land is too expensive in center city for very many of them; this is the last one Furness built before rising real estate costs drove even him back to the row-house concept. On Delancey Street, there is a house which he improved upon by adding an 18-inch bay window in front. The uproar it caused among the neighbors is still remembered.

|

| Doctor Home and Office |

A block away on the part of 19th Street facing down the street, Furness built another reddish brownstone house to glare back at the neighbors. The facings of the front suggest three-row houses, and it was indeed the home of a physician who had his offices on one side, entrance in the middle, and living room on the right. The resulting staircase in the middle is used to good effect by opening a balcony on the landing overlooking the parlor below. As befits the Furness style, the wall is thick, the wooden beams heavy. And, in a gesture to the lady of the house, the room adjoining the living parlor is a modern kitchen so the kids can play while mama cooks or guests can wander by as she gets dinner ready. Times have changed, the servants quarters once were plain and undecorated. The lady of the house never set foot in the kitchen so she could care less what it looked like.

|

| Frank Furness Home |

As a matter of fact, that's the remaining problem for these places, the rate-limiting factor as chemists say. Automatic washers, microwaves, electric sweepers, spray-on cleaning fluids and similar advances are the new industrial revolution which makes these hulking mansions almost practical. What's still lacking is the social structure of Upstairs and Downstairs, the servant community overseen by the lady of the house, who once was sort of the Mayor of a town. The lady of the house is now a partner in a big law firm, or similar. It simply is not wise to leave a big expensive place unattended by someone constantly supervising the domestic help. It is never entirely safe to leave the financial affairs of the household in the hands of someone who is not a central member of the owning family. Perhaps the father of the family can be brow-beaten into spending some quality time with the children once in a while.

|

| Structure of Upstairs and Downstairs |

Perhaps an accountant can for a fee be trusted with the finances; perhaps a butler can be found who will whack the staff when they get out of line. But the plain fact is these monster houses were built around the assumption that the lady of the house would run them, and the old style of manorial life cannot return unless the house is completely redesigned for it. Someday, perhaps a genius of the Frank Furness sort will make an appearance, change everything, and make everybody want to have it. But it is asking for something else when you insist on this happening in an old stone fortress that was designed to house a different style of life.

Hospital Elevators

|

| Modern, High-Speed Elevator |

Elevators are a problem for any architect in any building, because they are expensive in a number of ways. If the building is no more than four stories high, it can manage to have hydraulic elevators, quite sturdy and comparatively inexpensive, but agonizingly slow. Taller buildings need high-speed electric versions, but the elevator itself is not the most expensive part. More important is that every elevator bores a hole in every floor, more elevators bore more holes, and the usable floor space on each floor is reduced. Further, the mechanical stress is mostly on the doors on each floor, which open and close hundreds of times each day, rather than the lifting engine of the cab. Elevators which seem to be breaking down continually, are mostly in need of new doors. In building a hospital, the architect confers closely with the administrator until the place is built and then the architect leaves. The administrator may leave soon afterward, too, because the hospital personnel who use the new building soon discover that when pennies were pinched, the result was fewer elevators. There's no right answer to this problem; nobody is ever satisfied.

|

| Waiting for the Elevator |

The surgeons long ago learned to cope with the problem by beginning their day before everyone else arrives. If the elevator comes immediately after being summoned and skips all intervening floors to the surgeon's destination, it can save at least a half hour of his time to make rounds at 5 AM. Multiply that imposed delay on hundreds or thousands of hospital employees, and it is possible to conjecture that hospital employees generally only work a 7-hour day, and spend the 8th hour waiting for the elevator. Whatever the actual calculation, it is a cost seldom actually calculated into the equation of constraining the installation of elevators because of cost considerations. Unwelcome crowding is a social cost, too. Bereaved relatives coming down in the elevator must meet students of various disciplines going up the elevator holding coffee cups and chattering. And all ranks and conditions must crowd into the unyielding back of the elevator when the door opens to confront a hospital bed with an afflicted patient aboard, surrounded by a team of attendants in pajamas, holding up bottles and tubes. Attempts are usually made to assign separate elevators for patients and/or equipment, but the attendants soon find out about elevators that save time, flocking to them in spite of signs, threats, administrative letters of admonishment, and dreary staff meetings. It is easy to identify new staff; they are the people who take elevators down. Everyone else learns to go to the top floor and walk down the stairwells. Outta my way!

|

| Harry Gold |

So, hospital elevators evoke recollections. Mine include the many times I rode up beside a sullen teenager named Harry Gold, who was going to the chemistry department of the old Philadelphia General Hospital. If we ever exchanged a word I don't remember it, so I have to regret that I missed out on striking up an acquaintance with a real, convicted Soviet spy, the one who passed hydrogen bomb secrets to those Rosenbergs who went to the electric chair protesting their innocence. Something to tell my grandchildren I guess.

On another occasion, Dr. John Y. Templeton was standing impatiently for an elevator at Jefferson Hospital. John was a brilliant surgeon from Virginia, one of the inventors of the heart-lung machine, and also one of the quickest, most irreverent wits in Medicine. The door of the elevator opened, to reveal a completely crowded crowd of assorted folk, with a Doctor Zimskind standing in the front. Templeton's southern accent boomed out, "Going down?" "Going dow-un?" Lost in thought, Zimskind had trouble finding his voice and simply poked his index finger skyward two or three times. To which, Templeton shouted out, "The same to you, Dr. Zimskind. But are you going dow-un?"