1 Volumes

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Hospitals and their Future

New topic 2019-03-21 19:29:46 description

Philadelpia Hospitals, Past and Future

It was sixty years before Philadelphia had a second hospital, so the way things were done at the Pennsylvania Hospital tended to set patterns. The central pattern was: charity for poor folks, during a period when prosperous people were treated in their homes. Since Franklin was the secretary of the Board of Managers, it is in his own handwriting that we see "Founded for the sick poor and, if there is room, for those who can pay." In 1900, two-thirds of all hospital beds in Philadelphia were still ward beds for the poor. In 1948 when I was a two-year unpaid intern there, a posted sign said the accident room charge was fifty cents, but in fact, it was only collected if the patient happened to have insurance. The student nurses ran the place unpaid, and the main exceptions were the two paid administrators, the Steward, and his secretary. Philadelphia was settled for religious freedom, enjoyed many new religions, and consequently had a long era of Methodist, Episcopal, Presbyterian, two Jewish hospitals and the hospitals belonging to three Catholic Orders.

With the advent of the Civil War, PGH (Philadelphia General) grew to seven thousand beds, all of them free, when it was discovered more soldiers were dying from diseases than from wounds. Surgeons and obstetricians built specialty hospitals for their patients, mostly small ones, like Babies Hospital, Preston Retreat, Contagious Disease (mostly polio), Casualty, and a host of tuberculosis and psychiatry hospitals, Eye Hospitals, HEENT Hospitals, Children's Hosptial, and a number of small paying hospitals. The Civil War and the invention of anesthesia created a need for small hospitals for people who could pay, like Skin and Cancer.often in the shadow of larger charity hospitals for those who couldn't' pay. The first question any audience asks with bewilderment is about the cause of so many current hospital mergers. Part of the answer is we once had too many hospitals, and the rest of the answer was that the Flexner Report created a surplus of government money, intended to support research, and similarly stimulated by the creation of Blue Cross in the 1920s. Flexner favored research money, and the Universities grabbed it. The insurance mechanism was the best available means to save money when you were well, in order to spend it later when you were sick, but insurance muffed the chance. They chose one-year term insurance, mostly because short-term business was paying the bill. When money was no object, money was wasted.

The quickest example of honey attracting flies was observed shortly after 1965, when Philadelphia teaching hospitals (there were 104 of them at the time) went to Mayor Rizzo, suggesting PGH should be closed, ostensibly in order to facilitate the flow of federal funds to private hospitals. Thus they would help teaching hospitals absorb the abundant flow of government charity while eliminating the $11 annual cost of PGH to the City. That transformation from mostly charitable to largely private hospital care took from 1977 to 2010, to the private amusement of those who had been present at the meeting. At the end of this transformation, their positions had reversed; the teaching hospitals now bemoaned the shocking disappearance of the city's medical charity through PGH, casting such people back onto the teaching hospitals. Vannevar Bush probably had a hand in this, as the pretext was that only teaching hospitals did research. Meanwhile, they lobbied strenuously to retain monopoly control of federal research money, at the expense of charity beds within the teaching hospitals. In other words, we had a reasonably satisfactory system of charity care until charity patients demanded equal facilities from public money. Lyndon Johnson gloried in his achievements, but the fact is they opened the door to the unsupportable expense. The nursing profession was utterly flummoxed to be given degrees in return for the disappearance of their profession. If the combatants had stopped long enough to ask, there simply was not enough money to do what politics was demanding. The nursing school was always the heart of the hospital; the doctors were too busy tending to patients. And charts which they mostly falsified to save wasted time. Adding to the confusion was the effect of shifting nurse training costs, from the hospitals (diploma) to university responsibility (bachelorette degrees) and the adverse effect on nurse quality was noticeable. Doctors no longer married nurses, for example, they married lawyers and similar pre-professionals. The greatest effect, aside from higher cost, was to remove the loudest objectors from the scene, at just about the wrong time. The universities were clamoring to transform the nursing profession into administrators, in order to satisfy a seemingly insatiable demand stirred up by muddling the medical record-keeping system with the task of creating huge records which no one has time to read. The public regards medical matters as too obscure to understand and so does not appreciate how much cost has been created by switching everything non-essential around. It seemed obvious to them that non-essentials were poorly done. But not being medically trained, they weren't able to tell what was non-essential. Improving legibility and interphysician communication was nice, but it wasn't the main business of a hospital. Physicians learned to practice good medicine in tents and scarcely saw any difference.

Lawyers have learned something, too. They learned that antitrust violation is not signaled by per se violations or even vertical integration. It is signaled by mergers. Senator Specter may have kept Robert Bork from the Supreme Court. But the Law is slowly catching up with mergers, and Bork's books are still in print.

The future of hospitals does not lie in buildings. Doctors' practices are easily moved to retirement villages where the old folks are. Patients are there a long time, and equipment is easily moved there to be with them. It would save a lot of money because diseases are disappearing. Something like five diseases now represents something like 80% of the cost, but all that money spent on hospital buildings has already been spent, so it will take too long to get there peacefully. For all I know, five new diseases will replace five old ones, but the trend is downward. Costs keep going up. Doesn't that tell you something? What's going to happen to all that real estate after we cure cancer?

Specialized Surgeons

|

| Regina E. Herzlinger |

Local attitudes always somewhat persist among migrants from home. What's distinctive about the Philadelphia diaspora is how unconscious most of them are about still carrying the hometown mark. Philadelphia leaves a prominent birthmark, but it's sort of back between your shoulder blades and you forget it's there. What occasions this observation is a Christmas call from a prominent California surgeon who was once my roommate, back in the days when residents were actually resident in the hospital. More than fifty years ago Bill Doane also served as best man at my wedding. Our conversation turned to clots in the lung, and he related a story. He had once fixed a hernia for a 22-year old girl in the days when it was customary to keep hernia cases in bed for a while. Getting out of bed for the first time, she coughed and turned blue, suddenly on the edge of death. Taken back to the operating room, her chest was opened, and Bill removed a clot which was essentially a cast of the blood vessels of one entire lung. As surgeons like to say, she then did very well.

One doctor can tell such a story to another doctor in four sentences, while lay people who overhear it miss the whole point. The fact is, not one surgeon in ten thousand today could carry this off. Nowadays we train thoracic surgeons to open the lungs; they never repair hernias. Conversely, we train hernia surgeons to fix a dozen hernias daily through a little telescope; they never open a patient's chest. So it is hard to imagine many contemporary surgeons who could recognize this disastrous complication of hernia repair, then fix it themselves in time to rescue the patient. Although this disheartening decline into repetitive super specialties has been forty years in the making, it has been recently popularized with the general public by Regina E. Herzlinger, a Harvard business professor. Writing books and speaking to businessmen groups, she has popularized the proposal to outsource the general hospital into what she calls "focused factories." She rightly characterizes the medical profession as reluctant. She's a nice person, and undoubtedly sincerely believes focused factories will save money, improve quality. But we must not let this idea take hold.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

Specialty hospitals have actually been given more than a fair trial. About a hundred years ago, the landscape was peppered with casualty hospitals, receiving hospitals, stomach hospitals, skin and cancer hospitals, lying-in hospitals, contagious disease hospitals, and a dozen other medical specialty boutiques. With a few notable exceptions, they all failed for the same reason. Sooner or later they found they could not adequately service their specialty without the backup of a full hospital service. Children's hospitals do thrive, but they have patients who are generally of the wrong physical size to fit adult hospital facilities and equipment. There are plenty of things to regret about general hospitals' design, but the inescapable fact is they all must have a very wide range of services to perform any mission, no matter how discrete. It would be still better if the doctors had an equally wide range of skills in their own heads, but the avalanche of innovation and lawsuits has forced sub-specialization, compartmentalizing, and narrowness of viewpoint. Circumstances have forced the profession to hunker down, but that trend must be resisted, not celebrated.

The instant and successful repair of pulmonary embolism make a dramatic illustration, but the reasons for broad medical training are more extensive than that. In the first place, it is much cheaper to use the generalist office than to bounce people to a gastroenterologist for heartburn, a psychiatrist for anxiety, and a dermatologist for pimples. The American employer community is desperate for a way to reduce its burden of employee health costs, and flocks back to their nurturing business schools for advice. They would do better to seek repeal of the tax dodges which tempted them into their present muddle, of course. But in any event, they must be persuaded to recall the disaster of managed care and at least, avoid meddling in hospital design.

That's the cost issue, where specialization surely raises costs. Constant repetition of the same procedure seems superior to first-time fumbling, although it is questionable how long it takes a well-trained surgeon to pick up a new procedure and do it well. But for this system to work, the referring physicians need to be more skillful, not less, in choosing a good one to refer to. There's just nothing like the experience of working for a few weeks in the specialty as a rotating intern, to tell you what to look for and what to avoid. If every doctor in a hospital is making a dozen internal referrals a day, the cumulative effect on the quality of the whole institution is dramatic -- when they have had sufficient past involvement in the specialties to which they now only refer patients. Some specialists will become popular and rich; others will sulk around unnoticed for a while, then go elsewhere. This process, of course, occurs everywhere; what's institutionally distinct is the culture underlying the standards for preferences.

We'll talk later about the Doane brothers of Bucks County, who were judged to be too handsome to hang. Right now, the point of this story can be summarized by the old Pennsylvania Hospital adage, that you must first be a good doctor before you can be a good specialist. Not only was the Pennsylvania Hospital the first in the nation. For sixty years it was the only hospital in the nation, and for decades after that, it was the only hospital in Pennsylvania. In medical history circles, it is said that the history of American medicine, is the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital.

Don't You Touch My Medicare!

We have heard Medicare described by Senators as the "third rail of politics" -- just touch it, and you're dead. Unfortunately for clever phrases, the costs of the last decade of employment are shifting to a point we may foresee major health costs for working people getting heedlessly dumped onto Medicare as a desperation measure. Meanwhile, Medicare grows more expensive and national indebtedness grows worse. That's what single-payer enthusiasts demand, but even politicians on the campaign trail acknowledge that something must be sacrificed in the name of affordability. A growing gap in coverage for divorced women and early retirees already exists between the end of employer coverage and the beginning of Medicare, because no one has figured out either how to cover the increasing longevity, or how to assign the gap cost to multiple former employers. So, we might well pass through a phase where Medicare costs are rising, employer costs are declining, while the political parties merely blame each other for failing to cover the growing gap of uninsured which lies between dual coverages for elderly healthcare and simple retirement. Life insurance companies may suggest themselves merging Medicare with retirement insurance, but former employers reply "catch us if you can." Politicians describe "affordability," but that's what it amounts to.

If we could shift the cost of employee medical cost elsewhere, we might have an unbeatable wall against foreign goods, but there are perplexing limits, even to success. As we found at the Bretton Woods Conference, if we have all the money, foreigners can't buy anything. To be useful, a solution to the American hospital payment problem must be gradual, and it must be adjustable. Plenty of desperate foreigners stand ready to cut your throat if it isn't. So medical costs and retirement costs simply must be reduced as a painful but inevitable price to pay.

After we solve that issue -- wonder of wonders -- scientists will start to pick off the diseases of old age. We are already given to understand that the NIH has ordered a priority to grants for curing the most expensive ten diseases. That somewhat conflicts with the goals of scientists, who tend to concentrate their attention on the easiest diseases to cure. But money is money, and so we find that eighty percent of health care costs are caused by eight or ten diseases. With over thirty billion dollars flowing into research annually, relatively soon one or two of those dread diseases will disappear from concern, longevity will increase somewhat, and we hope some less expensive disease will finish off the temporarily lucky survivors. No doubt, we could use a few billion to pay off debts to the Chinese for our previous deficits. But the time will surely come when buccaneers will wish to spend the surplus generated in this manner, on something else more trendy than elderly health care.

Unless we have the foresight to anticipate this collision of interests, an unfortunate precedent might have been set. Leaders of the elderly and their concerns should anticipate this battle, and be better prepared to meet it. The best way to meet it is with a completed plan in operation to shift Medicare gains from research to retirement funding as they appear. The problem of funding Medicare (which is 50% subsidized by foreign bond sales to an insupportable degree) would then take the form of changing the name of Medicare to Retirement Care, because most of the money then goes to that purpose, a fairly meaningless and thus easier political problem to manage, because it will take a generation or two to happen.

By the way, Medicare represents the largest expense in the healthcare budget, so liquidating it gracefully will generate the largest source of new funding for the lifelong scheme. We now turn to the problem of funding the early years of life, which seems destined to be the hardest problem to address. In fact, it is so difficult there are essentially no competitive plans of any substance so a workable proposal might have surprisingly clear sailing.

Academia Gets Its Share of Blame

In 1910, Abraham Flexner produced a book-long report on reforming medical education, under the sponsorship of the American Medical Association and the funding of the Carnegie Institution. The report was a product of the progressive era of reform which ended the Gilded Age, and can fairly be described as the handbook of a revolution in American medicine. The book had an impact on closing 106 of the 160 medical schools in the United States and Canada. To Flexner that was a disappointment; he thought only 31 were worth saving. To be a good doctor, in his opinion, required between six and eight years of scientific training. The quality of student, as well as the quality of schools, was important, justifying a vast shrinkage of the student body. He liked research and unleashed an avalanche of medical research which subsequently transformed medical care in a hundred ways.

Having said all that, it must be acknowledged, Abe Flexner had been educated in Germany, and his efforts mainly crystallized the transfer of German academic medicine to America, and from here onward to the world. What's being acknowledged is that for a time, German Medicine was far ahead of us, in an environment where we aspired to be the leaders.

Flexner was a charismatic figure, supported by American Medical Association reports from its Council of Medical Education, the wealth of the Carnegie Institution, and the enormous resources of the Rockefeller Foundation. American academic medicine pointed to the example of the Johns Hopkins Medical School, formed before the ferment of pre-World War I, and now being given prominence by Teddy Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson and the rest of the muckraking era who aspired to replace the Gilded Age with something better. America was aching to take charge of something, had great gobs of philanthropic money at its disposal, and the wind in its sails. Abraham Flexner was a towering figure, all right, but he was not a physician, an academic, or a scientist. He was more the agent of revolution than its originator, ending up as the patron saint of several political factions, individually fighting academic wars with each other. He was, in short, a rain-maker.

Abe Flexner, the Rainmaker

|

| German Model for Medical Schools |

Abe Flexner and his book aimed to reduce the number of medical schools from 160 to 31, demanding the survivors look like German schools. This was not so strange; like Japan and China today competing with America, Flexner wanted to compete with Germany more than he wanted to worship it. The students of his dreams were required to be college graduates, the curriculum was to be four years along with two years of science followed by two years of hands-on learning. If the school could afford it, the professors would be on a full-time salary, free of any need to practice in order to make a living. On this last point, many begs to differ, arguing you have to get on a boat to learn how to sail one. There were many echoes of the ferment to come, in the upheavals of the 1960s, and the Humboldt's University of Berlin was the source of quite a few, in both cases.

Immediately there arose a town-and-gown competition. The gown group had the point they could afford the time to do some research. The town group had the point you couldn't teach doctors if you weren't one, yourself. The distinction is probably best understood by comparing medical students with law students. Both were originally taught by practitioners; schools were late arrivals. Many lawyers have remarked that a law school graduate now knows almost nothing about the practice of law until he joins a firm which teaches it to him. A medical student (post-Flexner) can do a pretty good job with most medical problems, the day he graduates. The practicing physicians have retreated into specialty training; a doctor has trouble becoming a specialist if he didn't have the right residency. The rest of the awe-inspiring march of medical progress in the Twentieth century, is the consequence of pouring unbelievable amounts of money into the system, thereby attracting a glittering array of talented medical students. Some of the talents are unbelievable. My own medical school, as an example, has a symphony orchestra made up of students in their spare time, performing on a truly professional level for their own amusement. In a sense, all of this was due to Flexner. In another sense, Flexner himself had little to do with originating it.

Now, forget the yellow journalism, or muckraking, quality of what I am about to relate. A book was recently published relating that a particular medical school was able to support its operations without touching a penny of medical student tuition for ten consecutive years. Instead, the tuition money was transferred to the University's undergraduate schools, and the medical school subsisted on research and other funds. The undergraduates continue to protest about rich doctors, while the medical students complain about going a hundred thousand into debt -- to pay their tuition. But forget that part. The most undesirable situation it reflects is that for ten years, the school was totally able to exclude any parent and student influence in an area that unfortunately has a growing power over events, the school's finances. If the students, families, and alumni of a university have no power to influence its decisions, who do have such power?

Two Central Mistakes In The Design of Health Insurance.

Concentrate on two flaws in healthcare. If uncorrected, no scoring -- dynamic or otherwise -- will conceal collective failure to address health costs seriously. Other problems should stand aside while these two are considered.

The first is pay-as-you-go. Its name misleads, because the younger generation, enjoying good health, pays its parent's high health costs toward the end of life, passing their own to their children. Medicare's first generation thus was given a free ride, so my mother who died at the age of 103, represents a whole generation who paid essentially nothing for thirty years of expenses. This example of debt being passed along for fifty years, got bigger with time throughout 18% of Gross Domestic Product, even with low-interest rates. We must liquidate that debt, invest the idle savings until needed for healthcare, and eliminate the annual 50% Medicare deficit to creditors. Quite a task.

An important result would be the incentive to save, replacing the incentive to spend. HSAs demonstrate net savings in health- the cost of at least 20% because, in a Health Savings Account, young people of each generation earn interest while they save for their own subsequent health costs, instead of spending immediately for anonymous demographic groups of strangers. At this point, another unexpected bonus appeared:

Some people have the luck not to get very sick, thus able to accumulate tax-exempt money in the account until they turn 66. Since everyone gets Medicare eventually, current law turns HSA accumulations into largely unnoticed tax-exempt retirement funds. (It's mandatory, whereas I would prefer an option.)

A second blunder reached the surface. Medicare provided better medical care, but made longevity increase, laying bare it had added thirty years of retirement cost. Sickness cost is episodic, but retirements are continuous. Consequently, additional retirement costs can become several times as costly as the sickness costs they replace. Talk about sweeping something under a rug.

It will not be easy to produce packages of proposals to cover the transition to a less costly funding system. But no health funding scheme other than Health Savings Accounts provides even the flimsiest scaffold for addressing this issue. Social Security has such a mission but is hopelessly underfunded. So the second of two big problems facing us, is: we failed to anticipate success.There is a third big elephant in this room to be wiped out with a paragraph of legislation. Scratch any regulation and you find a lobbyist underneath it. Half the population enjoys a tax deduction denied the other half, and that other half is restless. Unless big corporations yield to the demand for equality, there will be continued agitation. No doubt lobbyists promise to address this issue under tax reform and perhaps plan to reserve their concessions for later trade-offs. But one half of the public owes such a large debt to that other half, little quid pro quo is justified. Permitting HSA to pay the premiums for required high-deductible insurance could accomplish it in a handful of sentences.--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The fourth big issue offers hope, instead of despair. Medicare coverage for young unemployable persons ("disabled") was effectively broadened to over 90 %, by unemployed effectively changed to unemployable. Higher costs were thus added to basic costs for 9 million of the 46 million regular Medicare recipients, rather than remaining lumped with the 30 million uninsured unemployables (requiring specialized programs.) These higher costs of average Medicare per employable person, have been overlooked by most commentators, making ordinary Medicare seem costlier than it really is. It's bad, all right, but not quite as bad as it seems. Documenting that fact, as well as shifting the medical income tax inequity to the tax bill, leaves only two new issues to address: pay-as-you-go, and retirement funding. That's quite enough for a first round.

Hospital Cost-Shifting Between Payer Classes

Diagnosis Based Payment: A Warning

I was sitting in the Congressional hearing room when it happened. A proposal from the hospital association was made to Congress in 1983 that instead of paying hospitals for each step of treatment, they should be paid by the diagnosis, and Congress soon agreed to the idea for Medicare. This system was to be limited to helpless inpatients. The idea had some good features: if a patient had to be fed with a spoon, he had little interest in the cost of his treatments. Under these circumstances, market mechanisms would never restrain the cost of hospitalized patients. If they were anesthetized, it was even truer.

DRG: An Object Lesson for Control Freaks With Little Interest in What They Are Controlling.

|

So in this way, by arranging the assignment of costs to codes, Medicare and the hospital coding clerks took over the job of pricing. No doctor understood what in the world they were doing. And by steps familiar to accountants, the DRG was enlarged back to a thousand codes and internally arranged to come out paying the hospital a 2% profit margin for inpatients. Since we were running a 3% inflation at the time, the effective push was on-- to move in-patients to the out-patient area. No matter how many tests, no matter how long the patient stayed, the DRG came out to produce a 2% profit margin. The cost the insurance had to pay was lessened, the costs the hospital actually incurred, became the hospital's problem. Meanwhile, interest rates were low, so new outpatient buildings seemed cheap. Pretty soon, hospitals were paying doctors above-market prices to fill the outpatient area. There's more to say, but the idea is clear. Once you find a rationing tool, the accountants are in charge, the doctors are out, and eventually would be really out. And the beauty part of it was, no one understood what was happening, or who did it. Except you will find a lot of empty out-patient buildings when the music stops.

Health Savings Accounts: Synopsis

Ben Franklin felt medical care would pay for itself by putting sick people back to work. Not quite.

1. It works for some people, sometimes. That's the old system, which now needs a few tweaks.

2. To work for a whole nation, it needs more money -- a magnification system, which implies fewer options to choose between.

1. For individuals, it can be lifetime, which would be shunned by unsuitable clients.. There should be no age or other limits, so everyone can have one, at all times if he is able. If it has been unused (for medical payment) for a full year, it should still continue to generate income, but the premium for catastrophic insurance should be waived for the following year as an incentive to save it. It may accept additional deposits, however. This seems to be the administratively simplest way to keep it functioning as an investment while temporarily managing duplicate insurances (from employers or marriage difficulties, etc.)

HSA is the only health insurance where fund surplus becomes retirement income at age 65. That should remain an option until death, changing into a 21-year post-mortem trust fund which is permitted to use fund balances for medical debts and purposes, untaxed, with final surplus taxable in an estate as if an IRA). It probably should not accept additional deposits, however. (This option replaces the present mandatory exchange for an IRA upon acquiring Medicare coverage, and the mandatory Catastrophic feature should be dropped when Medicare coverage begins.)

The catastrophic system needs statements and limits about its regulation, fees, state coordination, what to do about abnormally low returns (using domestic total market indexes as a benchmark). It ought to address state vs. federal issues in a general way.

2. To serve the whole nation, rather than just the individually suitable subscriber, it needs a uniformly longer time horizon , more augmentation of income by compounding, more attention to security and long-term income, and more benefits to compensate for fewer options. In fact, it may need a consultation about passive investing of index funds. To preserve funds for long periods of time, audited escrows are absolutely required for protection against the imperfect agency. Starting small, this system could grow to enormous size. Because of longer time frames, the fund may need to allow flexibility for other investment strategies which at the moment are discouraged. I suggest the total stock market index as an audit benchmark with adequate penalties for failure to match it. The smaller investor needs rules, the bigger ones may not. If it has a good income return, it may require less attention to its format. Events will determine whether this is mostly a campaign document or a long-term strategy and whether it must be implemented in steps. Both Medicare and ACA took on too much all at once and stumbled. I suggest reforming Medicare first, children later, working people piecemeal.

The post-mortem trust fund needs to be checked out with estate lawyers. the last years of life reinsurance as an alternative. My sense is the trust fund is politically easier for the elderly to understand, but the elderly may want to plan ahead and so would prefer an insurance approach. Those who are fearful of outliving their income may have a preference. Lawyers have mixed incentives about closing estates early.

I don't see why due diligence hasn't appeared for every change of party, for all programs. Insurance salesmen may prefer to lock you into one program or another, and flexibility is not always in their interest.

Changing the legal responsibility for children's costs will be generally resisted, but the parents are young and fearful.

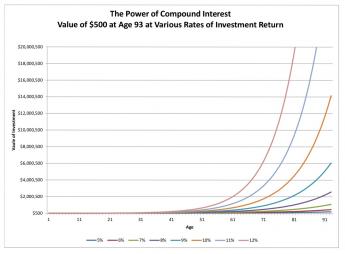

The elderly have most of the health costs, while working people have most of the revenue. The trick is to transfer the funds without so much resistance. There must be some sort of trade-off for employers to let go of their loophole. It took the Civil War to weaken states rights in the Constitution, and World War II to give employers their tax loophole. Making the public understand compound interest may require another 2007 crash. But as long as we have 3% inflation, it's about our only hope. Under no circumstances allow the government to own common stock. or socialists to control corporations.

I know the weaknesses of subsidized research. Somehow, subsides never get called or counted, as costs.

The Effect of Tax Law on Health Costs: The IRA for Health

The Effect of Tax Law on Health Costs

The IRA for Health

Section I

Chapter Three

Introduction

If the preceding chapters have done nothing else, I hope they have at least acquainted the reader with the fact that the current federal deficit is currently made worse by seventy billion dollars through the tax exemption of health insurance premiums, the largest American tax loophole ever recorded. Further, this tax exemption is inequitably distributed and is a source of societal friction which could express itself in unpredictable ways. And therefore the politics of dealing with it must be very carefully handled. This chapter is a serious description of a proposal for dealing with the issue. I believe it contains nothing which would injure a component of society, and it would not increase the federal defeat. It would slowly remove health costs from employer budgets, and it would ultimately nudge them considerably.

The idea of a Health IRA had its beginning at a dinner for the White House policy staff which I was invited to address in 1980, and the Provocateur was John Mc Claughry, then Senior Policy advisor in the Reagan administration. It must be remembered that the IRA (Individual Retirement Account) law had not yet been passed, but John must have heard about it, and suggested an extension to health costs. Since Mc Claughry’s main intent was in agriculture, he never did much with the health idea. But I was electrified by the idea and took it back to the American Medical Association. Curiously a relatively similar idea was independently brought to the AMA by Dr. Michael Smith of Thibodaux, Louisiana (he called it The CHIP program) the AMA took quite a while to digest the idea but it was eventually adopted by the AMA House of Delegates as an official AMA policy proposal. Somewhat later, but entirely independently Peter Ferrara of the Cato Institute and John Goodman of the Institute of Policy and Research came on the idea and pushed it forward as a replacement for the Medical program. My own views are more expansive. I believe that all health insurance should be eligible for the IRA approach. with a voluntary conversion provision any time after age 65..

Funded Insurance.

Having rattled the cage about tax deductibility in the previous two chapters, it is necessary to make another digression before discussing the Health IRA. It relates to the second flaw in the tax laws affecting health insurance. Employer- paid health insurance premiums are tax deductible, but it is forbidden to carry the benefit forward beyond the year in which it is earned. There were probably good uses for this limitation which are obscure to me, but the essential fact is this limitation made it impossible to build up cash value within a health insurance policy the way you normally build up a cash value within a whole life insurance policy, except by HSAs. Using the reasoning of life insurance, all health insurance is term insurance. Using the reasoning of social legislation, health insurance is a pay as you go scheme. Any way you look at it, health insurance is by law hampered in using the massive power of compound infected to reduce its ultimate cost. Here is the appeal of IRA for Health in the eyes of Peter Ferrara and John Goodman: forty years of compounding where it could greatly reduce the cost of Medicare when the individual reaches age 65, and the existence of the funded reserve would make the insurance promise a lot more secure. Alternatively, just allow everyone to have two policies, one for the current expense, and one for saving for the future.

Portability.

I like that thought, too but for me, an equally important need is to build up a reserve within the policy so the individual could experience periods of unemployment without losing his health insurance. To lose your insurance when you lose your job crippled the Clinton Health Plan, and preventing a pre-existing condition limitation crippled the finances of the insurance companies because the average time between job turnovers was 3.5 years Obama plan, almost all chronic disorders were excluded unless the Obama administration was willing to raise premiums. Some hidden hand was unable to concede the point, and Obamacare costs spiraled out of control. Either the insurance must transform from term insurance to permanent insurance, or else cost would be insupportable. Apparently, those speaking on behalf of employers were unable to concede either point, so the situation just drifted and got more expensive. I have repeatedly seen patients who became sick while they were unemployed. And then became they had developed a “preexisting illness†they became uninsurable even if they got a job. Or they couldn’t get a job because employers recognized they were expensive to hire. To me, the linking of health insurance to employment was a concept which needed re-thinking if individual tragedies were to be avoided. Somehow, it was easier to characterize such opinions as insensitive, than to do anything to repair the underlying problem.

Furthermore, part of my job is to listen to people’s troubles. Many times I have heard patients complain they hated their jobs but were afraid to quit for fear they would become unemployable during the change-over. For practical purposes, health insurance under the employer-based system is not portable between jobs. It has not already collapsed because so many diseases of younger people have been cured, adding thirty years to life expectancy. If the new employer provides group health insurance, it is on his own terms and those terms may be unfavorable to the individual. I have just once in sixty years of practice, encountered an employer who changed the benefits of his group policy and was thus able to terminate the ongoing payments to the dependent of one employee. Employer casual group health insurance is a reasonably good system. But as the health of the nation improved it developed lots of flaws which might have been corrected. They weren't, because the health part was never the main concern of enough employers, so they permitted the health companies to resort to short term patching.

To me, it is a flaw that the employer sets the terms of the policy. It seems much better if a way can be found for the employee to own his own policy, raise, lower or change the benefits as he is willing to pay for them and carry his policy with him as he chooses his own employment circumstances. The employer is mainly interested in the cost of the employee benefit, so let him restrict his interest to how much he is willing and able -- to pay.

Reducing Unnecessary Care with Health Savings Accounts

B

Other Voices: Rethink Lifetime Health Finance

(Revised)

Medical finance is an inter-generational funds transfer. Sickness costs migrate later, workers age 18-64, get less sick. Retirement seemingly replaces sickness, but -- so far -- merely displaces it later, without added revenue. One-eighth of lifetime medical cost now transfers between generations by payroll taxes, another quarter must be borrowed. Nine million disabled-under-65 are paid revenue originally intended for the elderly. The rest is roughly balanced, or was before the Affordable Care Act raised alarm about government's indifference.

Since 1965, Medicare collects 2.9% payroll deductions, immediately spent for their parents as "pay-as-you-go ", gathering no income. Lifelong debt concentrates into Medicare debt, as healthcare migrates toward the elderly. Politicians, terrified to touch "the third rail" of Medicare, respond at the wrong end of life. Thirty years are added to longevity, while healthcare debt evolves into retirement costs. And then, the money runs out. Statistics are rough, but retirement deficits equal Medicare's laundered debts getting worse as healthcare improves. Talk about conflicted incentives.

A solution: view one eighth of revenue as accumulated over 42 years, whereas a quarter of costs could be more than recovered by compounding the same idle money over 104 years. Try it free on the Internet. This achievable result comes from 1) extending age limits of Health Savings accounts down to birth and up to a trust Fund's perpetuity, defined in common law as a lifetime plus 21 years, while using an unfunded HSA to unify unspent compounded income for his own retirement, not for demographic groups of strangers. 2) Investing the payroll tax at no less than total market index funds, assuming a 3-7% lifetime return. 3) applying grandpa's surplus $4000 to grandchild's underfunded $4000 shortfall. (Please read that twice).

The compounding period is extended upward by post-mortem Trust Funds escrowed for Medicare-related costs only, extinguished when transition debt ends. It is extended downward 21 years by grandparents transferring approximately $4000 to one grandchild or equivalent, as HSA to HSA. Trust funds finance the transition deficits. This has the advantage of terminating Health Savings Accounts around age 18 when medical costs are lowest. Add the additional possibility of transferring the mother's obstetrical costs to the child, thus reducing premium costs for the 18-45 year age group as well. Much of this magic lies in the superiority of compounded rates over inflation rates. Long-term solvency appears likely, and borrowing is ended.

George Ross Fisher MD 3 Haddon Avenue South Haddonfield, NJ, 08033

Cell 215-280-6625 office 856-427-6135 Email: grfisheriii@gmail.com

The Two New Revenue Sources for HRSAs: Investments and Compound Interest

Two "new" revenue sources, which we need to discuss, are really quite old. But widespread use of third parties to pay medical bills diminished consumers' attention to their value. Patients become like Queen Victoria, indifferent to what it costs to run a household, even forgetting how to do it. We fit some details into the discussion of Health and Retirement Savings Accounts, but they are capsulized here for descriptive convenience, in an era when personal management has largely moved from junior high schools to the curriculum of graduate business schools. In the process, we have forgotten a timeless message: never let an agent manage your checkbook for you.

1. Compound Interest. Aristotle complained it gets more expensive to repay debts, the longer you take to pay them off. That's the debtor's viewpoint, of course. The creditor's view of it is, the longer the better. But restated as a neutral mathematical comment, an essential feature of compound interest is that both principal and effective interest, rise over time. To repeat: income rates (and/or borrowing costs) from a debt, increase with duration. About half the capital of every major corporation consists of debt, so even owning common stock has some of the quality of being a debtor. Furthermore, this effect is seen sooner, with quite small rises in nominal interest rates. A graph of sample interest rates demonstrates this simple truth with greater clarity:

|

As a result of centuries of haggling and experimentation, most modern loans charge interest rates of 5-15%. That's an enormous swing, but only for long-term investing. It makes little difference whether this range of rates reflects the supply of money in the economy, or the vigor of the economy, or something else macroeconomic. So long as rates remain steady, or even if they are changing at a slow steady rate, borrowers and lenders can reach an agreement and negotiate a long-term loan. If there is uncertainty about rates in general, they may rise precipitously, so all borrowers know to keep loans as short as possible, and creditors quickly raise rates when they must cover longer time periods.

The moral is, as you become older you tend to become a creditor, so adjust your mentality from borrowing short to lending long. For centuries, nobody thought much about this invisible equilibrium, because life expectancy was stable at the Biblical threescore and ten -- and in fact only twoscore. But suddenly around 1900, life expectancy at birth began to rise, and starting in 1950 it entered a steep climb from forty-seven to eighty-four years. Thirty-year loans remained the extreme, however, because the proportion of those who would chisel you doesn't seem to change much. Stagecoach robberies went away, but inflation took their place. Underneath it all, governments prefer to expand the currency supply rather than raise interest rates, printing repayments rather than repaying them. Interest rates are, as they say, volatile. Within limits, they are also malleable.

Nevertheless, the expansion of longevity created a new opportunity. The long-term investment was more profitable for everybody. The upturn in interest rates was relatively negligible for the first forty years of compound interest, but progressively quite handsome after that. In practical terms, buy-and-hold became a better strategy. The difference of a tenth of a percent means little in a ten-year loan, but it can create a stupendous profit in a ninety-year loan. One suspects the interest rate on a bank loan has more to do with the debtor's working life (the period available for confident repayment) than his life on earth. In this book, we concentrate on the creditor, whose lifespan should not affect interest rates as much as it affects his opportunity to enjoy money, so long as he has some of it. But a long life without money at the end of it is a fearsome prospect, indeed.

2. Equity Index Investing. The stock of only one company (General Electric) was a member of the Dow-Jones Industrial Average a century ago. By definition, the DJII always contains thirty leading stocks; others have been replaced many times. It takes a long time to become a household name, and by the time an investor has heard the name, it is often ready to decline. Active investing, meaning sell one to buy another, was once quite necessary for success. Unless fading leaders are replaced by new leaders, however, the average would fall behind, But it is easy to see the average has moved steadily upward, so it must be actively managed by someone.

If you are careful to avoid the spongers and the fly-by-nights, the investment world is rapidly changing, mostly for the better. To some extent, this reflects a flight from the bond market which governments deal with, but most investors now think total market index funds are safer. When the Federal Reserve forces banks to buy its bonds through "Quantitative Easing", the supply of bonds goes up and so the price goes down. "Passive" investing is certainly easier for the small investor to deal with, and investors are responding.

Later we will try to take advantage of one obvious flaw in such investing. If a single investment represents thousands of companies, investor control is diluted to meaninglessness. The only effective control over management then resides in the shares which are not held by funds; and even there, more and more corporate control rests with insiders and managers. The effect of such a trend is not merely that manager salaries are inflated, but the corporation becomes less responsive to the consumer public. Its legitimate business plan is to make a profit, but to make a short-term profit at the expense of long-term profits is not so defensible. Because of the corporate shield, many corporations borrow too much, risk too much, and collapse too often, but their managers often walk away with riches. If Health and Retirement Savings Accounts really get popular (at last count, they only had thirty billion dollars invested), its counterweight of stock ownership should help restrain consumer prices. Nevertheless, experience seems to show that competition between companies has been a more effective guardian of public interest, than stockholder control of individual competitors.

HSAs collect money when it is not needed, spend it decades later when it is badly needed, and invest the money during the interval, tax-free. The longer the interval, the more it earns. And with careful application of the principles of compound interest and index investing, the earnings are considerably magnified. If your Christmas Savings Fund earns more money, it reduces the effective cost of what you buy. But if you are careless, investment fees and inflation will ruin everything. So that, in sum, is another message.

Stretching Out Your Retirement Savings

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Benjamin Franklin was able to retire from the printing business at the age of 42. His partners bought him out in eighteen yearly installments. In the Eighteenth century, it was unusual to live past the age of 60, so Ben felt pretty well fixed. Unfortunately for this planning, he lived to be 82, so when he did reach the age of 60 he was forced to look around for postmasterships and other ways to survive, for what proved to be 22 more years.

This is the other side of a coin; on one side is written, "Protect your family in case you die young". On the opposite side is written, "Be careful not to outlive your savings", relying on the old Quaker maxim that the best way to have enough--is to have a little too much. For centuries, life insurance was sold to people who mainly feared the first, commonest, possibility, but never completely addressed the opposite contingency, which was growing steadily commoner. Annuity insurance ordinarily is sold for a fixed number of years, so insurance commissioners ordinarily require what is most probable. Unfortunately, this response shifts the risk of guessing wrong onto the subscribers' shoulders. Since science has unexpectedly lengthened average life expectancy (by thirty years since 1900, or by five years in the last ten), experience rather like Ben Franklin's has become a commonplace, but rather poor business judgment. The business remains solvent only as long as the decision to drop the policy is later than the life expectancy.

|

| Retirement Saving Debt |

There may exist insurance policies to address this issue, but few companies offer it. We will briefly describe this sort of policy, in case it becomes more widely available, but it is primarily described here to illustrate the issues to consider. If you can get it for a reasonable price, or if you can get it at all, the outline of the policy would be to set a premium and promise to pay 6% for the rest of your life. Underneath the promise is the reality of paying 6% for eighteen years as a non-taxable return of principal. Following that, you don't need to get a postmastership, you are paid a taxable 6% until you die. Presumably, the insurance company has actuaries to help with the math, so the company makes money if you live less than your life expectancy, and loses money if you live longer. If life expectancy suddenly extends much longer (let's imagine a cure for cancer appears), the insurance company is going to go broke. That's why insurance commissioners are uncomfortable with the concept, even though it is obvious how desirable it might be. So that's why annuity insurance typically states a fixed number of guaranteed years and expects the subscriber to shoulder outlier risk.

Any insurance has an administrative cost, so everyone must consider some non-insurance solution to the whole problem. Therefore, we propose you re-examine the old saw about "never dip into principal". If you don't have enough money, you can't do very much except depending on the government, your family, or your fairy godmother to help you out, although it must be obvious that all Americans would be wise to consider retiring five or ten years later than they hoped. Very likely, the government is going to have a difficult time sustaining even the present tax exemption of retirement funds, medical insurance, and social security. Those are called entitlements, but if the government eventually can't afford them, it won't matter what you call them. If entitlements keep getting extended, we can expect our nation to resemble the ancient Chinese and Indian nations -- able to build palaces in their golden era, but eventually crumbling into a gigantic slum in centuries afterward. So please, if you are able to do it, try to keep gainfully employed for a few extra years. If you do it (and some people can't) you may be able to realize the American Dream.

|

| Inheritance Tax |

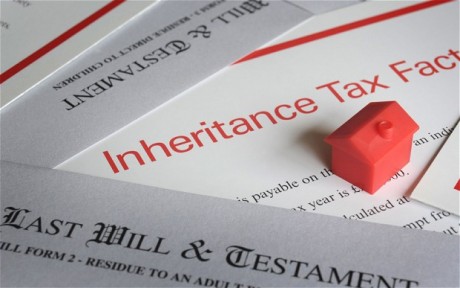

The traditional American dream was to accumulate enough money to live off the income from it indefinitely, never touching principal, and then exposing the principal to destructive estate taxes after you finally die. Unless you are unusually wealthy, there isn't much left for the next generation after estate and inheritance taxes and expenses. It's a little inefficient to accumulate more than you actually need, but the government gravitates toward the least painful methods of collecting taxes. By confiscating this safety surplus, however, it declares that "Every ship (generation) must sail on its own bottom." And therefore it must acknowledge responsibility for what inheritances ordinarily pay for, like charity and good works. But there remains a quirk to this.

If Ben Franklin's partners had arranged to invest the money until he needed it, they could at least have afforded to finance two or three extra years. After inflation and expenses have eaten away at your retirement income, your principal may not generate enough income to last forever, but it is still big enough to pay for several years of retirement, which may in fact be longer than you are destined to live. Remember two things: 1) a principal sum, big enough to support you indefinitely, must be roughly eighteen times your yearly expenses. If it is only big enough to support you for fifteen years, it will seem too small until you realize you are probably actually going to live, say, five years. And 2) as far as leaving an inheritance to your children is concerned, there is a realistic probability that the government will consume most of the estate before it ever gets to the kids. These fundamental truths are presently obscured by the Federal Reserve artificially forcing interest rates to less than 1%. But if you can just hold out for a few years, it seems entirely likely that interest rates will return to 6% (meaning your principal will once again produce eighteen equal installments). But such a return of interest rates to normal levels will force the government to pay a comparable amount as interest on its bond debts (meaning it will get hungrier to escalate your estate taxes.) This isn't nearly as satisfactory a solution to the life expectancy quandary as retiring five years later than you once expected to, but you can't say we didn't warn you.

And as for what happened to Ben Franklin, you can read his will. He died a very rich man as a result of shrewd investments, later in his life. Ben left eight or nine houses, several thousand acres in several states, a gold-handled cane, and a portrait of the King of France surrounded by hundreds of diamonds. But it would not seem wise for the rest of us to count on accumulating that much new wealth, after attaining the age of sixty. The way things are going, once you attain your life expectancy, everyone should have some non-insurance plan for supporting himself for two or three extra years.

Paying for the Healthcare of Children

It has been said by others that eventually healthcare will shrink down to paying for the first year of life, and the last one. Right up to that final moment, medical payments must somehow evolve in two opposite directions. We might just as well imagine two complimentary payment systems immediately because the two persisting methodologies could eventually conflict unless planned for. Paying in advance is fundamentally cheaper than paying after the service is rendered because there is no potential for default in payment.

The two methods even result in different aggregate prices; in one case you pay to borrow, while in the other you get paid to loan the money. Dual systems are a fair amount of trouble; remember how long it took gasoline filling stations to adjust to credit cards versus cash. When gas prices eventually got high enough, they just charged everybody a single price, again. This isn't just lower middle-class stubbornness. Dual payment systems slow you down, and profit is generated from repeated rapid transactions. The buyer wants the goods and the seller wants the money. The profit comes from doing exchanges as fast and often as you can manage them.

In a well designed lifetime scheme, with balances successively transferred from one pidgeon-hole to another, it becomes possible to maintain a positive balance for years at a time (thereby reducing final prices, because the income from compound interest keeps rising toward its far end). That was a discovery of the ancient Greeks, but sometimes Benjamin Franklin seems like the only person to have noticed.

The last year of life is more expensive, But the first year of life may cause more financial pain.

|

However, In real-life health costs, there is one intractable exception. Because obstetrics can be costly, particularly the high costs of prematurity and congenital abnormalities, the first year of life averages $10,500, or 3% of present total health costs. It, therefore, results in pricing which many young parents cannot afford, in spite of insurance overcharges to catch up later. And thereby a multi-year stretch of interest income is jumbled up, often lost entirely. It gets worse: childhood costs from birth to age 21 average 8% of lifetime healthcare. Please notice: Single-year term insurance premiums always rise to a much higher level than a lifetime, or whole-life, premium costs, because of internal float compounds in whole-life. Modern medicine has also resulted in rising lifetime costs, with only this obstetrical exception. Someone surely would have figured this out, except excessive taxation of corporations created a motive not to notice the effect on tax exempted expenditures.

This problem obviously could be approached by borrowing or subsidizing. Someone might even envision a complicated process of transferring obstetrical costs to the grandparents for thirty-five years, then transferring the costs back to the parent generation. Since we are describing a cradle-to-grave scheme, it seems much better to imagine a single person's costs eventually becoming unified. Grandparents do in fact share continuous protoplasm with grandchildren, but before that was recognized, the courts had decided a new life begins when a baby's ears reach the sunlight. Stare decisis beats biology, almost every time. A society which already has a high divorce rate and plenty of other family upheavals probably feel better suited to the principle of "Every ship on its own bottom." -- except for this financing issue. For childless couples and parentless children, some kind of pooling is possibly more appealing, and the complexities of modern life may eventually lead that way.

|

In the meantime, lawyers, who see a great deal of human weakness, are probably better suited to suggest a methodology for transferring average birth costs between generations, and back, although a voluntary process seems more flexible. It would seem grandparents are often most likely to be in a position to leave a few thousand dollars to grandchildren in their wills, and age thirty-five to forty seems the time when competing costs are at a lifetime low, making that the best time to pay it back.

Some grandparents are destitute, however, and some parents are basketball stars. There are surely generalizations with many exceptions. The process is happily simplified by a birth rate of 2.1 children per couple, which is also 1:1 at the grandparent/grandchild level and our Society has an unspoken wish to increase the birth rate if it could afford it. For legal default purposes, matrilineal rather than patrilineal descent may be more workable. But -- if every grandparent willed an appropriate amount to some grandchild's account, it would work out (with a small balancing pool), creating a small incentive for the intermediate generation to have more children.

The answer to this dilemma probably lies in revising the estate-resolution process, making HSA-to-HSA transfers largely automatic within families, devising a common law of special exceptions and adjustments, and creating a pooling system for special cases which defy simple-minded equity. A large proportion of grandparents have an indisputable defined obligation, and a large proportion of grandchildren have an indisputable entitlement. The difficult problems reside in the exceptions and require a Court of Equity to decide them. We leave it to others to fill in the details because there could be many ways to accomplish this, and some people have strong preferences. The basics of this situation are the grandparents with surplus funds are likely to die later, but they are still likely to die, close to the age when newborns are appearing on the scene.

When you get down to it, the problem isn't hard if you want to solve it. By arranging lifetime deposits in advance, a large number of grandparents could die with an HSA surplus of appropriate size. A large number of children will be born without a standard-issue family and need the money. After the standard-issue cases have been automatically settled, these outliers can be referred to a Court of Equity charged with doing their best. After a few years of this, the results can be referred back to a Committee of Congress to revise the rules.

A basic fact stands out: most newborn children create a healthcare deficit averaging 8% of $350,000, or $29,000, by the time they reach age 21. Most young parents have difficulty funding so much, and so all lifetime schemes face failure unless something unconventional is done to help it. A dozen more or less legitimate objections can be imagined, but seem worth sacrificing to make lifetime healthcare supportable. The main alternative is to pour enormous sums into the government pool, and then redistribute them. I am uneasy about letting the government get deeply mixed into something so personal. So, speaking as a great-grandfather myself, about all that leaves as a potential source of funds, is grandpa, and even grandpas sometimes have an aversion to long hair and rock music.

Last Four Years of Life Reinsurance

Half of lifetime medical expenses are reimbursed by Medicare. And half of Medicare represents the cost of the last four years of someone's life.

Having got middle-men off our chest, we return to a search for other ways to introduce greater efficiency into the medical financing system. That might be accomplished by reducing medical prices or eliminating medical problems with the research. Rationing, however, never seems to work without distorting resource allocation, and medical research is best left in the hands of the scientists. Here, we offer a third method, which is to increase the revenue by modifying its structure, while minimizing changes to the medical system it pays for. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) research budget is already $33 billion a year, and somehow that seems like enough. Right now, our mission is seeing what might be done with the payment system to fit its purpose.

Up until recently, paying for medical care has been treated as just part of paying for anything else, but it has some special features. For example, because of a welter of scientific advances, it is possible to imagine a future when nothing except the first and last years of life will contain any substantial medical costs unless they are self-inflicted to some degree. The American public seems consistently adverse to subsidizing self-inflicted conditions, which it views as a disguised form of suicide. Since homeless, addicted males seldom have children because females avoid them, non-cohabitation of the Lizistrata sort is a hidden way of punishing them for failing to support their families. With exceptions of this sort, medical care is an expensive need which will gradually become less essential. Except the system should be arranged to accommodate unexpected changes because change itself is confidently expected to occur.

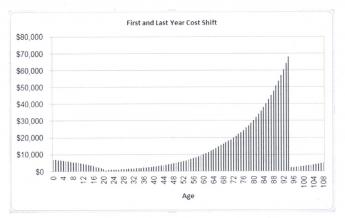

What's Reinsurance for the Last Years of Life All About? Ends of life concepts were designed to take advantage of the permanently J-shaped curve of medical costs to increase with age. They divide revenue into two investment classes maturing at different rates. The longer the period of compounding, the more we should want to save it for heavier expenses. (And the less we should be interested in spending a valuable resource on age groups with little to fear.)

Start by cutting escrowed Medicare costs into two subaccounts, differing in content and thus in timing. Overall, while all curves of lifetime health expenses are J-shaped, skewing progressively toward old age, containing roughly half of the expenses in Medicare, and half of that (one-fourth of total costs) concentrates in the last four years of life. (Later on, we will apply the principle to cover the increased cost of being born, addressing that initial upswing of the J.) There are six or eight variations, but our version has Subaccount A starting at age 25, the least expensive health year for the typical person, but also the time when Medicare withholding tax begins its forty-year climb. Our Subaccount B, by contrast, begins at birth with a major obstetrical expense, but currently must abandon this opportunity to achieve maximum compounded interest because of a newborn's lack of income. (The age group from 25 to 65 is temporarily abandoned to the Affordable Care Act until the nation decides whether to continue ACA, change its scope, or abandon it.) What follows is a description of financing everything except the Affordable Care Act, while temporarily accepting the implausible assumption ACA will seem revenue-neutral, until after the public gains full access to its books. The big data approach should speed up this examination.

Therefore leaving out ACA, and examining only what is left, Subaccount A buys out Medicare voluntarily, paying for retirement (which usually begins at the same time) with what is left over, in return for the hope of retirement income. Subaccount B pays for the last four years of life, thus removing half of Medicare cost from part A, as well as funding one grandchild equivalent until he or she reaches age 25. In effect, Account B pays for childhood, later materially helps buy out Medicare by re-insuring the last four years of life and eventually becomes the basis for First and Last Years Insurance as a pre-paid substitute for pay-as-you-go Medicare. It may take a long time to get there, but that's the goal. Meanwhile, it effectively cuts the cost of Medicare into two equal parts and thus makes it more digestible for a buy-out. (By applying different revenue sources, its timing is different in the two pieces.) During the long transition period, the payments for Medicare are divided between the two funds to satisfy obligations, one of them is extinguished, the other continuing to fund retirement costs until the death of the subscriber. It amounts to shifting the costs and revenue around, taking advantage of longer compounding for heavier costs. Ultimately, it raises questions of how far the public is willing to go with all that, including donations to another generation, and being educated it's a sensible thing to do. By accomplishing many things at once, it acquires what mathematicians call elegance, but the public may regard it as too complicated unless it is accomplished in steps.

If, during the transition phase, there still remains a deficit, consideration might be given to establishing postmortem trust funds as a fall-back to continue the interest compounding until its debts are paid, and/or conceivably pre-birth trust funds anticipating childhood costs (see below). At the moment, mandatory conversion into an IRA would be subject to tax. However, we hope Congress can be persuaded to defer the taxes until the date of death. In this way, unpaid taxes could be utilized to extend retirement benefits until they are needed, and taxes can be discontinued if they aren't needed. Meanwhile, savings continue to gather investment income. During the transition, there might be several revenue/cost mismatches which require expediency and/or bond issues, and there is no reason to see it as shameful.The substance of the following table is that the investment of $250 at birth would result in $21,714 cash for retirement at 65, plus the present value of $28,000 in Medicare premiums, plus an uncertain value for the improved structure. But this improved structure assumes no interest is gained on the premiums, and in fact, they would probably be discounted to present value. So, it seems better to sacrifice the structure for improvement in cash flow. That would be summarized as follows:

The last four years of life are not the same as the last four years of Medicare. It is only possible to establish which four years are someone's last ones after the date of death is known. The proposal here is to set one half aside as a special fund for the last four years of life because old-age health and retirement funds will generally not be needed for decades, but costs will eventually be heavy. When costs can finally be known, the Last Years fund reimburses Medicare. Some funds must be constantly consumed for medical care, and they should utilize funds which are soon to expire, and not be escrowed. Escrowed funds are usually set aside for distant medical costs, and like Odysseus bound to the mast, keep him from yielding to the temptation to use them prematurely. Meanwhile, a third, non-escrowed, subaccount is free to manage current expenses, and need not be dealt with further in this section. Medicare doesn't know when you are going to die any better than you do, so it reimburses every cost at the time it is incurred, spending revenue about as fast as it is received. Account A was designed for future healthcare costs in all but the last four years, a burden considerably lightened by removing those last four years and letting the revenue grow. The switch isn't exactly insurance, it is re-insurance. The beneficiary is then dead, and even his relatives would scarcely notice this transfer has taken place, except by auditing receipts.

When costs can finally be known, the Last Years fund reimburses Medicare.

As a matter of fact, Medicare needn't reimburse the particular costs for specific last-four-years clients, since there are only two parties directly involved, both of the insurance companies. By maintaining aggregate books, Medicare merely needs to determine the average cost for all its dying patients, to emerge with equal aggregate reimbursements for everyone who dies. Whether this bookkeeping short-cut can actually be utilized, however, depends on whether variations in regional cost are too substantial for local politics to tolerate. Even then, statewide averages might serve. This detail is an accounting efficiency which the two parties could sort out with Congress.

|

Everybody is born, everybody dies, and nobody does either thing twice.

|

Eventually, the taxpayer under present law might pay long term capital gains tax of 25% on withdrawals from tax-free accounts; revising such tax laws is under discussion. The present value of such revenue is difficult to estimate, but it would likely be offset by the reduction of interest rates paid on the indebtedness, which is also hard to predict. And all of this would be offset by a long term rise in the stock market, also subject to capital gains tax. Since a rise in bond, rates seems almost certain at present, and thus a long-term rise in stock market averages is likely, it seems reasonable to suppose the government would make a huge profit on an expanded Health Savings Account. Only a major prolonged recession or a war would reverse this judgment, and even that would see bond revenue mitigating the stock market loss. The private purchase of huge amounts of stock would certainly raise stock prices and might put any qualms of the IRS to rest. It is true, stock market exuberance can lead to a bubble which collapses, but this observation never seems to restrain a bull market.

To review the matter, splitting Medicare payment into two escrowed subaccounts and one non-escrowed one, has simple purposes related to transitioning between systems, and really isn't that hard to understand.

1) Technically, it allows longer-term funding to avail itself of compound interest for longer periods, largely by devoting more attention to the matter and ignoring the original assignment of the funds.

2) Secondly, a transfer of $18,000 out of a million-dollar retirement fund would not meet with nearly the same resistance as it would from a fund scraping the barrel to survive. We take this intergenerational transfer up in a later section, but here it should suffice to summarize, this transfer would solve a number of problems which hitherto have been treated as issues one simply has to endure.

2) Part of a spectacular revenue enhancement comes from adding twenty years of compounding a rather large sum ($1650 annually for 20 more years) onto the end of a long period (40 years) of compounding a smaller contribution, of $825 a year. Reversing the sequence (Medicare premiums first, payroll withholding subsequently) would generate even more revenue, and advancing Medicare premiums to childbirth-to age 25, would generate the most. Furthermore, any one of these sequences follows the design of original Health Savings accounts by ultimately depositing left-over funds into the individual's retirement account, as a sort of reward for being frugal. Acquiring revenue for other insurance components, what had previously been a unique feature of HSAs for retirement, it discourages early diversion of these funds to unrelated government activities (aircraft carriers, etc.), recurring anxiety of beneficiaries. Perhaps more to the point, it gives the client a tangible reason to be frugal, at an age when such ideas are not entirely natural.

3) The proportions of the public who have already consumed, or paid for, parts of Medicare will vary with their demographics, largely related to the year they happen to have been born. But a rising proportion of cost in one compartment means a decline in the other half. Because revenue often has unexpected connections to cost, this will always be a rough proportion, but it ought to help placate the sense of helpless public disenfranchisement which attends all major transitions.

4) And finally, this new configuration approximates the way things are probably going to go anyway, with ever-increasing concentrations of medical cost pushed toward the end of life. Not everybody dies at Medicare expense right now, but the universal trend is for people to die later, eventually making it approach 100%. Further, as we describe later, it provides a framework for first year-of-life coverage as well. That is to say, the trend is for health insurance to narrow down to the beginning and end of life, as science gradually eliminates the disease. One day in the far future it might be said, nothing else is left of major health costs. Everybody is born, everybody dies, and nobody does either thing twice. Insurance as we currently think of it will slowly become a thing of the past, replaced by what is more frankly a pre-payment methodology on a much grander scale. And eventually, the public will see it happening, which eases political resistance considerably

(1) Medicine at the Two Ends of Life: First year of Life, and Last Years of Life.

Benjamin Franklin founded the Ivy League's University of Pennsylvania, but he was surely no academic. He was a practical man, looking for practical results, and some of the fiercest battles he fought concerned the direction and purposes of his University, especially the nature of its mission. At a time when most Ivy League Universities were mostly divinity schools, he would not Pennsylvania tolerate it that way for his own, and to this day the University of Pennsylvania has no divinity school, although it does have something very close. If there had been such a thing in his day as a Nobel Prize, he would have won it for his achievements in electricity. In the centuries-long journey from divinity school to occupational credentials, Franklin's position and the general academic position have drawn marginally closer together. The first academic course in science was only taught around the time of the Civil War. The term "philosophy" would now be used as a word for "science", and a Doctorate of Nuclear Physics would puzzle most physics majors, even though they aspire to achieve that Ph.D. degree. The American Philosophical Society is quite definitely a scientific society, and most definitely was founded by Benjamin Franklin. These were not idle arguments in the Age of Reason.

To speak more practically, a great bulk of scientific achievement consists of experiments to reduce complexity, and ultimately to reduce costs. No doubt there are scientific discoveries of new fields, and probably the greatest prestige attaches to those who uncover some totally original feature. But the surprising bulk of the effort is devoted to simplifying and reducing costs. If a scientist employed by a big company should discover some cheaper way to do something more simple, he will be rewarded, and it may well make his career. If he discovers how to solve a mathematical equation in significantly fewer steps, his accomplishment is described as "elegant". That's the nature of science, to accomplish a goal, no matter how complicated. To make it profitable, you cut out a lot of the fumbling and get right down to the nub of a solution, with fewer steps, and cheaper materials. If you are unsatisfied with this generalization, just compare some random salaries of chemical engineers, with theoretical chemists.