Related Topics

Pearls on a String:Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

Pearls on a String: Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts.

HSAs are the string. Retirement saving, Privatizing Medicare, and Shifting Childhood Costs-- are the Pearls. Other Pearls to follow.

Hospitals and their Future

New topic 2019-03-21 19:29:46 description

The Two New Revenue Sources for HRSAs: Investments and Compound Interest

Two "new" revenue sources, which we need to discuss, are really quite old. But widespread use of third parties to pay medical bills diminished consumers' attention to their value. Patients become like Queen Victoria, indifferent to what it costs to run a household, even forgetting how to do it. We fit some details into the discussion of Health and Retirement Savings Accounts, but they are capsulized here for descriptive convenience, in an era when personal management has largely moved from junior high schools to the curriculum of graduate business schools. In the process, we have forgotten a timeless message: never let an agent manage your checkbook for you.

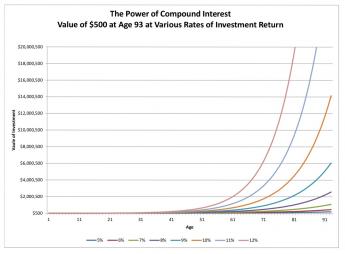

1. Compound Interest. Aristotle complained it gets more expensive to repay debts, the longer you take to pay them off. That's the debtor's viewpoint, of course. The creditor's view of it is, the longer the better. But restated as a neutral mathematical comment, an essential feature of compound interest is that both principal and effective interest, rise over time. To repeat: income rates (and/or borrowing costs) from a debt, increase with duration. About half the capital of every major corporation consists of debt, so even owning common stock has some of the quality of being a debtor. Furthermore, this effect is seen sooner, with quite small rises in nominal interest rates. A graph of sample interest rates demonstrates this simple truth with greater clarity:

|

As a result of centuries of haggling and experimentation, most modern loans charge interest rates of 5-15%. That's an enormous swing, but only for long-term investing. It makes little difference whether this range of rates reflects the supply of money in the economy, or the vigor of the economy, or something else macroeconomic. So long as rates remain steady, or even if they are changing at a slow steady rate, borrowers and lenders can reach an agreement and negotiate a long-term loan. If there is uncertainty about rates in general, they may rise precipitously, so all borrowers know to keep loans as short as possible, and creditors quickly raise rates when they must cover longer time periods.

The moral is, as you become older you tend to become a creditor, so adjust your mentality from borrowing short to lending long. For centuries, nobody thought much about this invisible equilibrium, because life expectancy was stable at the Biblical threescore and ten -- and in fact only twoscore. But suddenly around 1900, life expectancy at birth began to rise, and starting in 1950 it entered a steep climb from forty-seven to eighty-four years. Thirty-year loans remained the extreme, however, because the proportion of those who would chisel you doesn't seem to change much. Stagecoach robberies went away, but inflation took their place. Underneath it all, governments prefer to expand the currency supply rather than raise interest rates, printing repayments rather than repaying them. Interest rates are, as they say, volatile. Within limits, they are also malleable.

Nevertheless, the expansion of longevity created a new opportunity. The long-term investment was more profitable for everybody. The upturn in interest rates was relatively negligible for the first forty years of compound interest, but progressively quite handsome after that. In practical terms, buy-and-hold became a better strategy. The difference of a tenth of a percent means little in a ten-year loan, but it can create a stupendous profit in a ninety-year loan. One suspects the interest rate on a bank loan has more to do with the debtor's working life (the period available for confident repayment) than his life on earth. In this book, we concentrate on the creditor, whose lifespan should not affect interest rates as much as it affects his opportunity to enjoy money, so long as he has some of it. But a long life without money at the end of it is a fearsome prospect, indeed.

2. Equity Index Investing. The stock of only one company (General Electric) was a member of the Dow-Jones Industrial Average a century ago. By definition, the DJII always contains thirty leading stocks; others have been replaced many times. It takes a long time to become a household name, and by the time an investor has heard the name, it is often ready to decline. Active investing, meaning sell one to buy another, was once quite necessary for success. Unless fading leaders are replaced by new leaders, however, the average would fall behind, But it is easy to see the average has moved steadily upward, so it must be actively managed by someone.

If you are careful to avoid the spongers and the fly-by-nights, the investment world is rapidly changing, mostly for the better. To some extent, this reflects a flight from the bond market which governments deal with, but most investors now think total market index funds are safer. When the Federal Reserve forces banks to buy its bonds through "Quantitative Easing", the supply of bonds goes up and so the price goes down. "Passive" investing is certainly easier for the small investor to deal with, and investors are responding.

Later we will try to take advantage of one obvious flaw in such investing. If a single investment represents thousands of companies, investor control is diluted to meaninglessness. The only effective control over management then resides in the shares which are not held by funds; and even there, more and more corporate control rests with insiders and managers. The effect of such a trend is not merely that manager salaries are inflated, but the corporation becomes less responsive to the consumer public. Its legitimate business plan is to make a profit, but to make a short-term profit at the expense of long-term profits is not so defensible. Because of the corporate shield, many corporations borrow too much, risk too much, and collapse too often, but their managers often walk away with riches. If Health and Retirement Savings Accounts really get popular (at last count, they only had thirty billion dollars invested), its counterweight of stock ownership should help restrain consumer prices. Nevertheless, experience seems to show that competition between companies has been a more effective guardian of public interest, than stockholder control of individual competitors.

HSAs collect money when it is not needed, spend it decades later when it is badly needed, and invest the money during the interval, tax-free. The longer the interval, the more it earns. And with careful application of the principles of compound interest and index investing, the earnings are considerably magnified. If your Christmas Savings Fund earns more money, it reduces the effective cost of what you buy. But if you are careless, investment fees and inflation will ruin everything. So that, in sum, is another message.

Originally published: Thursday, July 14, 2016; most-recently modified: Monday, June 03, 2019