3 Volumes

Surmounting Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

Health Savings Accounts: Steps To Lifetime Health Insurance

From 1981 to the Present.

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

Pearls on a String:Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

Pearls on a String: Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts. HSAs are the string. Retirement saving, Privatizing Medicare, and Shifting Childhood Costs-- are the Pearls. Other Pearls to follow.

This book has attempted to devise a goal and a way to reach it with stretched-out pre-payment in the hands of the patient. But the longer a change is drawn out, the more chance of misjudgment and what you seek most to avoid -- the pain of sudden collapse. The implicit cost has grown so large it could require a century to absorb it. And so the central question emerges as to how much shorter for safety the transition really needs to be. If we crash along the way, it is proof we waited too long. So what we might attempt needs to be better understood. We have developed a system of intimidating our leaders, to the point they are afraid to do the right thing. So the public demands even more vigorous creative destruction. This is your last chance, is what they seem willing to threaten.

My answer is it is impossible to answer in advance how long the transition should be, before we take the final leap. It is only possible to estimate, by experience, how much steady progress toward the goal is possible. It is only possible to know what rate of progress toward the goal, for what sustainable spurts of time, is enough to satisfy the public, that their leaders even approximately know where they are going.

------------------------

Front Stuff: Pearls on a String: Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

...Also by the same author:

The Hospital That Ate Chicago, Saunders Press, 1980

Health Savings Accounts: Planning for Prosperity, Ross & Perry, Inc. 2015

Surmounting Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Account. 2016

Pearls on a String: Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts (This Volume), 2016

---------------------------------

Ross & Perry Book Publishers

3 South Haddon Avenue

Haddonfield, New Jersey 08033

856-427-6135

----------------------------------

Pearls on a String: Further Extending Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts Copyright:

ISBN #: (978-1-932080-56-8)

-----------------------------------

Acknowledgements

For advice and support about the thrust of this much-revised book, I owe new debts to the many people who read the first versions and commented. The first book was written as ideas developed in my mind, and rather in a hurry. The second revision was written so later thoughts could be introduced earlier in the argument. This one was written and rewritten to rise above the twin possibilities that either, the Affordable Care Act would be completely repealed, or it would essentially survive forever. I still don't know its future, whether it is too big to fail, or too big to survive. Either way, I think it failed to reform some things which should be reformed. The best way to defend that position is to propose an alternative which is much simpler, but more radical.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Foldback, Front Cover

This book outlines the hidden advantages of Health Savings Accounts, which the author had a hand in creating in 1981, along with John McClaughry of Vermont when John was Senior Policy Advisor in the Reagan White House. HSAs had more advantages than we realized. By turning them into retirement funds at the end, not a word was changed but they created a new incentive to save, by adding a new reason to save. By simplifying reimbursement, they exposed the ineffectiveness of third-party policing and saved money to be multiplied by investment. They were a vehicle for subsidies to the poor, a Christmas savings fund for the frugal, and interstate mobility for the rich.

Finally, the idea dawned that such simplicity provided an avenue for a gradual transition to new programs, as well as an escape hatch if they failed. Beads on a string, as it were, with a common retirement fund at the end, as a universal incentive for savings in each program added. It might take fifty years to implement every step proposed. But then, it took fifty years to get into this situation.

--------------------------------------------------------

Foldback, Back Cover

|

| George Ross Fisher III M.D. |

George Ross Fisher, MD, the author of this book, graduated from the Lawrenceville School in 1942, from Yale University in 1945, and from Columbia University, College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1948. After postgraduate training at Pennsylvania Hospital, Thomas Jefferson University, and the National Institutes of Health, he spent 60 years practicing medicine in Philadelphia and consulting in New Jersey and Delaware. During that time, he spent 25 years as a delegate to the American Medical Association, and as a trustee of a number of medical organizations.

Following retirement, he formed a publishing company, Ross and Perry, Inc, which has published several hundred books, mostly reprints. He is personally the author of eleven books about Philadelphia history, from William Penn to Grace Kelly. He is the author of the following three books about medical economics:

The Hospital That Ate Chicago; Health Savings Accounts: Planning for Prosperity; Surmounting Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts and (the current volume.)

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Dedication Page

To Senator Bill Roth of Delaware, who demonstrated the road between private and public sectors, need not be a one-way street.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

Book cover back page, possibly in conjunction with above box and introduction, please discuss:

Health savings account

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about medical savings accounts in the United States. For international uses, see medical savings account. Health care in the United States

______________________________________________________

A health savings account (HSA) is tax-advantaged medical savings account available to taxpayers in the United States who are enrolled in a high-deductible health plan (HDHP).[1][2] The funds contributed to an account are not subject to federal income tax at the time of deposit. Unlike a flexible spending account (FSA), HSA funds roll over and accumulate year to year if they are not spent. HSAs are owned by the individual, which differentiates them from company-owned Health Reimbursement Arrangements (HRA) that are an alternate tax-deductible source of funds paired with either HDHPs or standard health plans.

HSA funds may currently be used to pay for qualified medical expenses at any time without federal tax liability or penalty. Beginning in early 2011 over-the-counter medications cannot be paid with an HSA without a doctor's prescription.[3] Withdrawals for non-medical expenses are treated very similarly to those in an individual retirement account (IRA) in that they may provide tax advantages if taken after retirement age, and they incur penalties if taken earlier. The accounts are a component of consumer-driven health care.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Prologue: The Approaching Battle

Overview. To be brief about it, spending for healthcare now crowds toward the end of life, mostly after age 65, while the money to pay for it is generated well before 65. Disregarding the complicated history of how we got here, in effect, we borrow from an interest-free account at Medicare to pay Medicare for Medicare, without earning interest on the money idled in the meantime, sometimes for as long as forty years. Potentially, the two age groups could unify their finances and get more or less dual savings. That's the dream advanced by the single-payer advocates, but on examination, the cost, politics, and complexities of actually unifying entire delivery systems would soon overwhelm total- merger enthusiasts. Unfortunately, the revenue has fallen too far behind the costs to make this completely possible. It is nevertheless contended here, only the financial transfers need to be unified, using Health Savings Accounts as a transfer vehicle, and allowing compound interest to extend beyond the boundaries of insurance programs. Such simplification, while not easy, would achieve most of the savings of unifying whole insurance programs, particularly the incentive to keep what you don't use, for your retirement. Among other things, it would solve most of the Constitutional problems, and avoids most of the delivery system obstacles. Indeed, a financial network is about all we could manage, but it is adequate for the need. Because of its towering cost components, even integrating the financial transfers might take longer than we anticipate.

But massive numbers are only part of the health financing problem. At the beginning of life, medical expenses concentrate forward, toward the very first day, leaving absolutely no way for the child's own income to pre-pay his expenses. No matter how it is rearranged, someone must give children some money. Indeed, this second issue seems so unsolvable, everyone has stopped trying to notice it. It only makes people uncomfortable to suggest that adding children to a new HSA system might add twenty-some years to the compound interest in Health Savings Accounts if they only had some money. They don't, so be quiet.

But on the contrary, if someone always gives children the money for their healthcare, why not acknowledge it? Frank acknowledgment seems pre-destined if you aspire to serve lifetime financing. You require two systems, roughly the opposite of each other. One delivery system faces toward the beginning and the other faces toward the end of life. (Even this conception finds the working class in the middle, largely funded by employers who change frequently and have other concerns foremost in their minds.) If the realities of life will never change, then it is the payment system which must adjust, with the finances of each system facing in opposite ways. The reader is therefore urged to toy with the eventual outline of a circular system, far down the line. For now, existing programs would alter their interface to accommodate a new funds flow, while changing their program as little as possible. There's still a big gap left unfilled: Those working people aged 25-65 who largely support the whole system, unfortunately already have so many constraints on their financing it is not feasible even to discuss their needs until the politics subside a little. Connecting, yes; unifying, only as much as you can. Therefore, this book passes over single payer as fundamentally over-reaching and concentrates on lower-hanging fruit.

Essentially, it is proposed: The Health Savings Account to expand to be a unifying financial bridge between programs, one account per individual lifetime, serving many disparate programs. Designed to be implemented in phased-in pieces, it continues to aspire to minimize changes in the delivery system itself. The reader will probably be surprised at how simple some dilemmas are likely to become, once it is conceded the individual patient ought to decide what others now decide for him.

Extended retirement costs are a predictable outcome cost of Medicare.

|

HSA becomes HRSA, Then Emerges as the String that Threads the Pearls

The book before you is not a list of dooms and glooms, it turns into a proposal. A proposal to preserve a functioning society by regarding child, parent, and grandparent as different stages of the same person's life, with united interest in the same goal. The same goal, even for a newborn, is a comfortable retirement. While it speaks exclusively to paying for healthcare, the same principles apply to any useful but expensive commodity. That is, as much as possible, individuals subsidizing themselves at different ages rather than members of three different classes of strangers. We build upon the idea of a Health Savings Account, one account per person throughout one lifetime, as a financial way to emphasize the underlying social point. If you spend too much too early, you won't have much left for later. That sounds far less obvious when it appears within separate compartments, with separate sources of funding. Separate sources have their own budgets coming first in their minds. They compete with each other for the same money, if they can.

This unification proposal -- Pearls on a String -- is voluntary, you don't have to do it, or even part of it, but in some ways, that's another advantage. True, there is no escaping the use of insurance for unexpected catastrophes, but really, only an insurance salesman would argue for unlimited insurance for everyone, all the time. Only someone who knows very little about insurance would believe insurance is a way of printing money for the customer. Compulsory also means uniform, government-issue. Voluntary, by contrast, isn't a one-size-fits-all commitment and doesn't dump 340 million subscribers onto inadequately tested systems, all at once.

Whether voluntary or mandatory, however, some facts are just part of life. Almost completely, the working generation must subsidize its older and younger generations, but it would do it better with a focus on the same individual at different ages, instead of by whole categories of strangers. For a final twist, we unexpectedly propose to empower solutions by leveraging a new problem we scarcely noticed we had (prolonged longevity and retirement). It isn't a trick; in retrospect, everything looks as though it might have been predicted.

Three New Potentials. Curiously, the Health Savings Account had to be tested before it could be fully understood even by its originators. A bit of history may help explain the delay. The basic concept of Health Savings Accounts was developed in 1981 by John McClaughry and me, while John was Senior Policy Advisor in the Reagan White House. Derived from the IRA concept developed by Senator Bill Roth of Delaware, it started as a Christmas Savings Account, to save up for the approaching deductible of (high-deductible) Catastrophic health insurance -- which was to be linked to it. So from its beginning, there were two linked features: (1) high-deductible health insurance, and (2) a medical variant of an Individual Retirement Account (IRA). For those unfamiliar with insurance jargon, a high "front-end" deductible policy connotes the insurance company only ensures that part of a medical bill which is greater than the stated deductible amount.The second implication of this third zinger in the system took even longer to sink in because nobody wanted to believe it. It suggested our path might never lead us out of the financial hole we were in. Not eventually, but never. The situation was this: As improved health care spread among the elderly, the elderly lived longer. Gradually and grudgingly, it was acknowledged extended longevity was a hidden cost of Medicare, unanticipated perhaps, but universal. Its pain first started to hurt beyond the insurance boundary, accounting for the delay in recognition of the link. There was Social Security, of course, left in the dust of thirty years of longevity added since 1900. Increased longevity was first discovered as destroying the attractiveness of defined-benefit retirements. But as it became acknowledged that good health and longer longevity were two manifestations of the same effort, the doubled cost began to be seen as insupportable. What's worse, the future cost of retirement is even harder to specify that the future cost of health care, because everyone has his own definition of a "decent" retirement. Underfunded retirement is an even stronger incentive to watch your pennies than a specified one because there is absolutely no one, not even that demonized one percent of rich folks, who can be certain there will be enough money left at the end, to last out his lifetime. Wasn't that combined incentive enough to get everybody's attention?Since this automatically means the higher the deductible, the lower the annual insurance premium; high deductible policies are the cheapest you can buy. When the Affordable Care Act was passed, all health insurance was required to have a "high" deductible, so the HSA idea then seemed moot. But a high deductible by itself isn't enough. Without the savings account attached to it, the client can't easily separate risk protection from pre-payment, or for that matter inpatient costs from outpatient ones. Ideally, the level of the chosen deductible is the result of tension between a high level to please the insurance company, and a low level to attract the customer. Call it luck or call it planning, a high deductible separates inpatient from outpatient, market prices versus fixed ones, optional costs from unavoidable ones, prevention from treatment, and risk protection from pre-payment. Out of these segregations, remarkable things can be achieved. The one danger is that the deductible might fail to change with circumstances. The divisions are set by the market balance between customer and provider and are rough ones. If either side succeeds in freezing the deductible, its underlying significance could disappear.

After experience in action, a totally new realization dawned that -- once the two parts became semi-independent -- the real deductible just becomes the unpaid portion of it. The unpaid portion of the deductible is now situated in the account, ultimately becoming zero -- but now the insurance premium no longer rises as the remaining deductible declines. Not at first but eventually, the HSA emerges looking like "first-dollar coverage" for the same low price as high-deductible insurance. The truth is, you have two insurance policies, one owned by the insurance company, and the deductible, which is self-insured, owned by yourself.

The higher the deductible, the lower the yearly insurance premium.

You can be as frivolous or as frugal as you please, within the self-insured deductible. The insurance could care less which it is. A great many people have no medical expenses for a whole year, so they get to keep all of it. Someone else could spend it all. Another way of saying this is, saving for the deductible has shifted into the customer's own hands without shifting any extra burden onto an insurance company. A mandatory expense now transforms into part of his disposable income. Frivolous (ie small) expenses are self-insured; necessary ones (ie expensive ones) are insurance-insured. It wasn't exactly the deductible that saved money, it was the new-found ability to exclude non-essential expenses if you chose to.

A second realization emerges from the tendency of non-insurance HSA managers to use debit cards for medical reimbursement, instead of insurance claims forms. (This freedom may well be a consequence of concentrating frivolous expenses into the deductible.) Although in the absence of strict scrutiny there might well be more temptation to cheat, a debit-card system depends on the client to howl if he suspects his money is being mis-spent. Otherwise, it will be lost. (When you spend a third party's money, there's less concern than in spending your own.) A decline of policing cost might even be said to expose a lack of overall effectiveness of the third-party approach to policing of claims. Since it is obviously more costly to police than not to police, that particular hidden cost of using third parties only emerges after it gets eliminated. (This same reasoning applies to a diagnosis-based payment for helpless hospital inpatients, a related issue which is now segregated into the insurance compartment of HSAs, but crippled by the crudeness of its DRG coding system.)

The foregoing describes two potentials, broader coverage, and less administrative cost, but an even more gratifying development might be a decline in elective claims, despite the reduced cost-containment effort. This is harder to prove, but highly likely. At first, this likely saving seemed attributable to the ("adverse") selection of unusually frugal applicants. But over time, a more likely incentive emerged: added provisions of the HSA act permitted any surplus remaining at age 65 to be turned into an Individual Retirement Account. That is, an incentive was created to save health money for retirement, by substituting personal responsibility for insurance company vigilance. All in all, it would not be a bad outcome. So far as I know, it is the only form of health insurance which has this feature, which every one of them ought to use, by means of attaching their "bead" to the "string". All other health insurance returns a surplus to lowering the costs for others; that only works if you never change companies, and even then, the temptation of management to skim it is undeniable.

In the existing environment, third-party reimbursement of healthcare now stands in the road of everybody's retirement, by being disjointed. That's not to suggest unifying whole programs, an overwhelming task, but merely to unify their transfers and their retirement termination, as well as the age and employment limitations of individual pieces. So long as left-overs ultimately belong to the individual, and the separate pieces are all available for compound interest along the way, the affiliations can be quite loose. On the other hand, if further program integration seems cost-effective, nothing stands in its way.The Driving Force. For the purposes of this book, the power of that unfunded retirement incentive was the HSA's most important new insight. Almost anybody could tell at a glance the high cost of Medicare was what stopped "single payer" in its tracks, what paralyzed Congress on healthcare, and defied solutions from any other direction. Medicare was the "third rail" of politics -- touch it and you're dead. But with a retirement entitlement looming behind it almost making Medicare costs seem laughable, it was a new ball game. Once retirement begins, retirement savings get steadily depleted, whereas serious health costs are usually episodic. Both begin at the same time.

HSAs are the only health insurance with the incentive to save for retirement whatever you don't spend for healthcare.

Six conclusions emerge:

1. The Health Savings Account, as is, is quite adequate (if funded, of course) to cover healthcare costs in replacement of existing health insurance. It's surely cheaper, although possibly not as much as the 30% reported in early trials. There are several reasons why that should always remain the case, although it does require more management by the customer. It is entirely suitable for intermittent use as employers and government programs change.

2. The HSA already contains the mechanism of the customer funding up to its present $3400 yearly limit, with annual cost of living adjustments but excluding the cost of the attached health insurance, gathering investment income for decades, and turning it over at age 65 as an IRA retirement fund. In honor of this feature, it is proposed to rename HSA to HRSA (Health, and Retirement, Savings Account.) As such, it would supplement any other retirement source but could stand alone. Its main flaw is easily corrected; the law limits coverage to employed people. No children, no supplements after age 65, but that would be simple to fix. There is a political risk in allowing the annual deposit limits to be at the mercy of changing political administrations.

3. New means of investment, such as passive investment of total market index funds, seem as safe as most investments now offered. Cheaper ways to increase effective returns should be explored, particularly in dividing returns between HSA management and their customers. I suggest published "fee-only" arrangements would give the public a chance to shop around. Later on, ways might be explored to balance voting power in health companies against the medical prices reflected in the price of their stock. Demonstration projects might be in order. Present owners of HSAs will probably be shocked to hear the total market has averaged 11% returns during the Obama eight years; how many HSAs paid customers more than 3%?

4. With minor legal adjustments, the HSA could serve as the investment conduit for: surplus generated by Medicare, a proposed Childhood Transfer System, an end of life reinsurance system (to be described), and any other health program which changes its proposals to transfer surpluses to retirement, as an incentive to become a frugal shopper. For the time being, however, it is intended to remain entirely independent of the Affordable Care Act until politics clarify.

5. The ultimate goal is to construct a lifetime framework for HSAa, to serve as a financial vehicle for connecting all health plans around a common investment and retirement framework. It might easily include such things as bounties for below-average health expenditures and rewards for superior performance of other sorts.

6. The longer-term goal is to re-arrange pieces of this network to increase investment returns, starting with Medicare (see below), Last Four Years of Life Reinsurance and First Twenty-five Years Gift Transfers, with the rest of life added, accordion-style. These terms should become clearer after later discussion.

Medicare's financing problems might even become a symbol the problem was not just a lobbying benefit to be defended blindly by its current beneficiaries. Increased retirement cost was, in short, an overlooked cost of health care all along, and anyone who stood in the way of coordinating things has misjudged the ultimate necessities. Standing closest to retirement, Medicare is in fact the very first program you must change. But you better do it very carefully. And by the way, you better do it pretty soon.

The Grand Plan for HRSA Networks, Very Briefly

So, we discover Health Savings Accounts are not snake-oil, a quick-fix solution to every healthcare problem ever complained about. No good idea is improved by such exaggeration. What is offered here is a long-term plan for greatly reducing the cost of healthcare, conceivably cutting it in half. It has some features which would show quick results, and we must devise a transition plan which puts them first. But it might take fifty years to achieve it all, and much can happen to upset plans in fifty years. The plan of this book is to suggest what should be done, in more or less the order of when to do it. But first to sketch in -- very briefly -- the final goals for doing any of it.

What Have You Done for Me, Lately? What I propose is a healthcare network of existing systems, linked together one by one with the retirement and investment incentives of Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts. The short term value of the network is to create a unified transfer system to the more distant goals, providing some time to reach them. The HSA will be tempted to wander from its mission but should remain as simple as possible -- a gussied-up transfer vehicle for healthcare funds. Most of the elements are in place for this, although some enabling amendments might be suggested. Meanwhile, the option must persist for using HRSAs by themselves as total lifetime coverage, since transitional changes may leave some people without suitable alternatives. But repairing existing programs rather than replacing them--Medicare, in particular--usually offers the advantage of shortening the transition time. The long transition period is certainly what people will find hardest to accept.

With the framework in place, the institutions attached to it should be gradually coaxed into externalizing their surpluses (dividends or their equivalent) instead of re-investing them, allowing surplus to flow between low-cost and high-cost eras of consumers' lives within the network, ultimately ending up as individual retirement financing in the private sector. That last part may be hard for people working in the public sector to accept because it removes the government as the insurer of last resort for pensions. But for reasons too obscure to describe here, that was never possible as long as Congress controlled the extension of the national debt. And that, in turn, was driven by the conviction the private sector was a superior creator of wealth, not an unlimited source of taxes. Ultimately, our model is the goose that laid golden eggs.

An easy early step would be to create following-year bonuses for low expenditures within the "pearls" on this string. Much will depend on intervening national politics, and it is intended to avoid including ACA or employer-based insurance until the direction clarifies. Meanwhile, everyone might have the option of adopting an HRSA fully, plus Medicare, plus the childhood transfer mechanism. The ultimate unified vehicle would be an accordion-structured First and Last Years of Life Reinsurance (see below), although if several variants emerge, that would be fine.

The final step, integrating the ACA and present employer-based systems is left entirely out of the project for the first few years. But driving it onward, posing the threat of retirement destitution if you don't, would be the availability of retirement financing from every penny you legitimately save from healthcare, from the day of birth to the day of death. Since no one wants to die, and very few enjoy living in poverty, restraining this vast incentive must rest with its health beneficiaries, since everyone is its ultimate beneficiary. When scientists finally do cure the worst diseases cheaply, the retirement folks may be permitted to start to win the healthcare vs. retirement pension competition.

Special projects and program outliers, such as prison inmates, mentally and physically disabled, and illegal immigrants, are left for us to find solutions more tailored to their needs, and here are not dealt with further. This proposal deals with the great majority of Americans who are not in poverty, not handicapped, and not poorly treated. Surely they should have a voice in such a vital topic, which from their perspective could be considerably cheaper, and rather easily improved over present uncertainties. Along the way, if they themselves could devise something beyond golf, bridge, gardening, and travel to occupy thirty years, it would be an enhancement to the community. Arguments can be made for regulating immigration, but not ones for providing servants for a rentier society.

We begin integration with the big gorilla, Medicare. In the first place, the program is bleeding money. The first step in saving money should be to stop losing so much of it, and that definitely won't be easy as long as serious illness keeps migrating into the Medicare age group. Furthermore, it contains the most expensive item of all, terminal care. The transfer of terminal care out of Medicare by the Last Four Years of Life transfer, should facilitate this decision. Other programs may get financially healthier if we do nothing. If we do nothing about Medicare, it probably will only get into deeper trouble.

At the moment, our best dream is the scientists will find something as cheap as aspirin, which will cure something as expensive as cancer. A century ago and roughly simultaneously, scientists discovered cures for pernicious anemia and type I diabetes, both fatal conditions. Pernicious anemia has virtually disappeared with occasional injections of a vitamin, while diabetes has grown to be about as expensive as anything, despite lifesaving injections of insulin. Unless you want to gamble on similar mixed outcomes in the future, read on.

The Segments of Lifetime Healthcare:

Medicare Including Retirement Pearl #1

The Affordable Care Act was announced as mandating health insurance for everyone, but about thirty million people were specifically excluded. The healthcare problems of seven million prison inmates, eight million unemployable, and eleven million illegal immigrants were too specialized to be included in a program which hoped to be one-size fits all. Quite properly, such special outliers would be better handled by special programs designed for their special needs.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is now central to Administration attention, and Medicare may be deemed too hot to handle in an election campaign. Nevertheless, we elected here to discuss Medicare but not the ACA. Retirement, childhood, and how to unify complete the list--pretty much all that's left surrounding, but excluding the ACA, election or no election. That emphasizes what had been evaded or neglected, and avoids direct confrontation with the ACA, preparing for the day when that big gorilla is either confirmed or abandoned. It's obviously too expensive, and it remains to be seen whether it can be fixed, or must be abandoned. In our alternative scheme, all of the lifetime healthcare would be financially connected to a single lifetime Health Savings Account, one account per person, but the delivery systems would remain semi-autonomous. ACA could surely live in peace with the HRSAs, and could even peacefully adopt the HSA approach. That would save money, but the questions left are whether it would save enough to be worth the trouble, and whether politics will allow it. Like the European Union, it's surely easier to describe than to accomplish.

Retirement as a Medical Issue. The news is precarious for retirement funding. We begin with the far end of life, where most health cost and all retirement cost concentrates. While retirement is parallel in time to Medicare, we begin to recognize increased longevity as an outcome of better health. If one is to help pay for the other, they must, in the Medicare case, draw their funds from the same pool. That's Medicare, which most people don't want to change, but is the first thing which must change. Because unchanged it costs too much to leave anything for retirement.

Although the Industrial Revolution brought many lifestyle improvements in the past two centuries, it also brought turmoil. The idea of leisure time may once have been a reward for the upper 1%, but actually, most of the population never dreamed of any leisure time. The novels of the "Lost Generation" after the first World War often revolved around the discovery of unfamiliar leisure pursuits by members of social classes newly learning about such things. The moral, then and now, seems to be that leisure is no bed of roses.

We must assign a reasonable definition to a "decent" retirement, provide for a marginal one, and leave the rest to our own sources of wealth.

|

Medicare As a Financial Issue. Medicare is about half paid-for, half borrowed, but it's really totally under water. According to Mrs. Sibelius, about half of Medicare expenditures are supported by the general fund or general taxation. The general fund is in deficit, however, providing some fairness to the description of Medicare as a fund borrowed from the Chinese, although China and Japan combined only purchase 13% of ten-year Treasury bonds. In the event of Medicare default, the main creditor victims will be U.S. citizens. The purchasers may change, but the deficit looks to be permanent. Until deficits are paid off, it will remain true that Medicare provides a dollar of care for fifty cents. That sounds wonderful until it suddenly sounds terrible. Medicare is bleeding money. If you want to know how brutal our government can get, read the section later on, about the Diagnosis Related Groups.First and Last Years of Life Re-Insurance By far the best proposal for refinancing Medicare, however, is to anticipate the way science is going to re-design costs. In the long, long, run, there should be very little medical cost left, except for the first and last years of life. We have no idea how long it will take, but that's the direction things are almost sure to be going.An accountant might say, Medicare's cash revenue is roughly divided between premiums paid by the beneficiaries, and pre-paid as a payroll tax of 3% on workers not yet old enough for benefits. (About half of this wage tax comes directly from the employee, another half from the employer. We skip over the technicalities that some parts of the program are tied to one fund, other parts to another, and also some are subject to higher income tax). About a quarter of Medicare is paid in advance on a "pay-as-you-go" basis, which is to say some people pay current costs of other people -- they are definitely not saved in anticipation of the contributors becoming beneficiaries, as the term "Trust Fund" implies.

About half of the Medicare deficit is paid as you go, about another half is borrowed; only a quarter of the budget is current revenue from the beneficiary age group.

A second quarter is indeed paid and spent by current beneficiaries as Medicare premiums. That is, about half of the deficit is paying as you go, another half is borrowed from foreigners; only half of the deficit is matched by current revenue from the beneficiary age group. Nevertheless, the payers of pay-as-you-go are about thirty years younger than the spenders of it. If we put the youngsters' cash to work for thirty years, what interest rate would it take to grow one dollar into three? The answer is about five to seven percent. For quicker understanding, a few unfamiliar tools are needed:

So, phase in a restructuring of funding for both children and elderly first, and then add in the rest of a lifespan, step by step. That way, you first fund an obligation you are always sure to have. Be sure to do it in such a way that maximizes the investment income at compound interest. This might be a project under construction for decades, but its first step would be to begin funding for the Last Four Years of Life, which happens to be an early proposal in refinancing Medicare. Since the reader may be unprepared for the topic, it is considered in a free-standing way, in the next section.

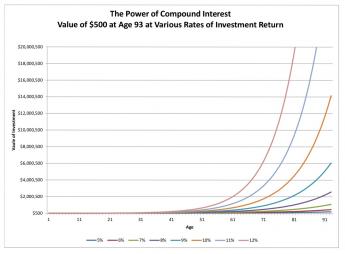

Pay at the time, or pre-pay in advance?> At first, it might seem frugal to have people pay for what they spend; let them pay for what it costs, when you know who ran up the cost. But in the case of birth and death, it's going to be 100%, and the amount of it is a lottery. By far the more important issue is the compound interest you earn by paying in advance. Using the rule of thumb that money at 7% will double in ten years, a life expectancy of 90 should double 9 times from birth to death. That is, a dollar at birth is worth $512 at death.

What's more, 50% of Medicare is reported to be spent in the last four years of someone's life. That's likely to represent terminal care, but it doesn't matter. If you prepay those four years, the rest of Medicare has its cost cut in half. In those two simple statements is found the nut of paying for half of Medicare for $100 -- ninety years from now. It's up to actuaries and accountants to find the "sweet spot", of the most revenue enhancement for the shortest time of investment.

Medicare Including Retirement, Pearl # 2

Invest the Withholding Tax and Pre-pay Medicare? Borrowing to pay for Medicare, except temporarily, has very little to be said for it. On the other hand, the choice between pre-paying for it and paying at the time of service is a closer argument. Pre-payment can sometimes be arranged to reduce the price out of recognition of the interest foregone, but usually, the seller gets the better of such a deal. In this section, we propose to arrange the payment stream to give the buyer the interest, but Medicare finances are so strained, it doesn't make a heavy impact. About a quarter of Medicare cost is paid from premiums from current beneficiaries. If that were collected in advance over a period of forty years like the payroll deduction, the combined interest payments would considerably reduce the eventual total cost. Unfortunately, young people are now so suspicious the money will be diverted to other purposes, it is a political question whether they would permit the withholding to be increased in amount. Furthermore, the other half of Medicare is essentially borrowed, so interest payments each way would about cancel each other without affecting the principal cost.They would, however, probably be sufficient to keep the debt from continuing to rise at 7% a year, and that's a major advance. The withholding tax and the Medicare premiums would remain the same, the benefits would be unchanged. So what's in it for the average voter? Most accountants would say it was still a desirable change toward a more stable system, but many politicians would say it runs a risk without any political benefit at the next election. Everybody is correct; it isn't enough but it is something. It solves a definable portion of the problem, of bringing future deficit increases to a stand-still. Things are so bad I'm afraid that's all you can buy for $3.5 billion a year. We must find some way to supplement it, but it's a start. We have five other suggestions:

Devise Some Way to Escrow Long-term Funding. New revenue ordinarily arrives as cash and is invested in short-term loans until it is decided what to do with it. With thirty-day loans, or even overnight loans, you just have to wait for a little, in order to restore cash status. But money market funds show us what can potentially happen. If customers get into a sudden panic, they want their money back immediately. If it's already invested in thirty-year mortgages, the money market fund may go bankrupt unless someone "bails them out". Which is to say, loans them more money to supply some cash -- even though they have ample funds frozen in long term investments. The creditors have their own creditors to consider. If no one will help out, the creditors may shut them down and you get the beginning of a liquidity crash.But all of the foregoing is small-time, based on the mistaken notion the system is basically sound. Let's look, without pretense, for seriously larger amounts of money:Because of this remote but very real possibility, the longer the loan, the higher its interest rate, because the liquidity risk gets extended. That's bad if you are a borrower, but please if you are a lender. Therefore, if the Medicare wage-tax receipts flowed into a frozen single-purpose investment account, creditors would be more assured money would be unrequested before the stated time, and its rate of return could rise with this new attractiveness. Just how much extra income would be provided is a little uncertain, because very few loans are currently for longer than thirty years. However, about forty-five years are potentially available between age 21 and 65, and educated guesses could be made. A one-or-two percent rise in income might change many calculations, not just this one alone.

Find Ways to Extend the Years at Compound Interest. Since retirement is conventional at age 65, a fund for retirement will immediately start to dwindle until the date of death. But many people continue to work or have other retirement funding sources. If they do not need the surplus immediately, they should be permitted to leave it in the escrow fund, to prolong its term. This could be either fixed-term extensions or demand deposits, at the election of the depositor, and its election would make these funds preferable to retain, compared with Social Security, for example.

The open-endedness of retirement is always going to be a problem. If we speak in averages, they suggest half of the population will be dead, mid-way to the average. Any unexpended surplus after their deaths will be a source of contention, and there will be a struggle for it between heirs and longer-term survivors. If the compounding of unused income could continue longer, for even five years after death, the extra revenue would be considerable.

Continue to Earn Interest after the Death of the Depositor, as in a Trust Fund Long ago, perpetuity was defined as one lifetime, plus 21 years. Adding another two decades would add two more doublings, and still not run afoul of inheritance traditions. In effect, it would increase the multiplier from 512 to one -- to 2048 to one, increasing the number of newborns who could afford $100, considerably, by making it only $25.

Because of the de minimus initial deposits, it would be a small matter to devote a small portion of the deposit to a backward-funding for childbirth costs. My Libertarian friends would be shocked to hear the proposal, but this small diversion would settle a myriad of cases before the Matrimonial courts about paternity, divorce, single parenthood, and even same-sex marriage. Indeed, the financial incentive might be so great it would affect behavior, and need to be debated on that level separately.

Contingency Fund. Any projection a century in advance risks making gross mistakes in its planning. No matter how confident the predicting party may seem, it is only prudent to have a contingency fund, when the multiplier of compound interest is so great. For example, most people can expect to be of Medicare age when they die, but not everyone will do so. But mostly a contingency will need to cover the considerable risk of simple miscalculation, without creating a temptation to divert it. The size of the contribution is scarcely a handicap. That is, a contingency fund of $2000 can be envisioned from the gift of $1 to a newborn. Since you know with absolute certainty that every newborn will die someday, a contingency fund of a million dollars per person is possible with a grant of $500 to everyone born in poverty, so long as:

you don't spend any of it for 111 years, providing you can get an average 7% return, and providing the government doesn't devise other uses for your money in the meantime.

Incidentally, increasing public resistance to inflation is one of the hidden virtues of this proposal. Most people would laugh at such a long-term projection. For a single individual, yes, for an extended family, not so much. The trick is to get started with small amounts, which don't attract much attention until they demonstrate some power.

Instead of fanciful extrapolations, it is possible to say almost every working person could summon up $200 per child, and the government could summon up $200 for those who can't. This is what is needed to provide supplements which would accomplish reasonable goals for lifetime healthcare, plus a somewhat more modest description of a comfortable retirement supplement to Social Security. And for those who are unable to support themselves for handicap reasons, the government might summon up the cost for indigents. In the long run, that would be a bargain investment. Since every child has two parents, it leaves a 100% cushion for under-estimates when we extend this idea to children. The problem is not arithmetic, it is public acceptance of the whole idea of individual long-term contingency funds, plus a way to store such a fund for centuries at a time, protecting it from pilfering by its custodians.

First and Last Years of Life Re-Insurance By far the best proposal for refinancing Medicare, however, is to anticipate the way science is going to re-design costs. In the long, long, run, there will be very little medical cost left, except for the first and last years of life. We have no idea how long it will take, but that's the direction it is going.

So, phase in a restructuring of funding for both children and elderly first, and then add in the rest of a lifespan, step by step. The rest of the lifespan will eventually shrink as a cost center, while the beginning and end would not. Be sure to do all this in such a way that maximizes investment income at compound interest. This might be a project under construction for decades, but its first step would be to begin funding for the Last Four Years of Life, which happens to be an early step in the proposal for refinancing Medicare. Since the reader may be unprepared for the topic, it is considered in a free-standing way, in the next section.

Pearl #3: Medicare Supplement, Only 20 Percent of a Pearl on the String

Now that we have described Health Savings Accounts as the string linking a string of pearls, we must have a second look at one of the pearls, because in a sense it is two of them. Medicare, it may be recalled, only pays for 80% of it's patient's liability, while the other 20% is the patient responsibility. That is, Medicare has a 20% co-payment, which amounts to a 20% reduction in benefits. Most people who can afford it will purchase a secondary insurance policy from Blue Cross or a commercial insurer, to cover this 20% liability, thus restoring the 20% of benefits at their own expense. Those who cannot afford such policies will often apply to state Medicaid, to become what is known in the trade as a "dual eligible". Those who are not eligible for Medicaid will often just take a chance on their personal resources, often becoming a source of the hospital's or doctors' bad debts. It is thus a curious feature that much of a hospital's bad debts come from the lower middle class.

Co-pay has a long history and a bad reputation. Most textbooks will classify it as a form of patient participation in his costs, and a restrainer of abusive claims. But it long ago developed the practical role of adjusting premium cost to available budget during group negotiations. If you don't get sick, you will have no co-pay obligations, but if you do get sick, it extinguishes 20% of the cost. So, although Medicare co-pay secondary insurance responds to the 20% co-pay feature of Medicare, in company negotiations for group policies for younger employees, it can be 30% or 27% or some other number, because the negotiators discovered that doing so reduced the cost of the insurance by 30% or 27% or whatever. It greatly facilitated middle-of-the night negotiations for the limits of coverage, with calculations on the back of an envelope, and probably had little relationship to restraining medical overuse. Quite obviously, it created the need for secondary insurance, with a double dose of administrative costs and profits. So an expensive and largely futile feature has persisted for seventy or more years, deeply embedded in Medicare for fifty. Usually the carrier for the secondary insurance is the administrator for the 80% which the government pays, but nevertheless, two confusing reports ("explanation of benefits") for two different insurances come trickling into the patient separately, two or three months after one treatment took place. But it does save the government 20% of its cost, so it persists. You will notice this 80/20 formula makes no effort to define or assign the extra insurance company costs and profits, which are negotiated privately. If utilization is affected little by co-pays, costs are nevertheless directly escalated by using two insurances to pay for a single medical encounter. Three insurances, if you include Major Medical policies.

In the case of Medicare, there is another quirk. As mentioned earlier, about 50% of the government's share of the cost, is borrowed. Insurance companies often borrow money, too, but usually not attached to a specific policy. While there may be hidden arrangements between Medicare and its secondary carriers, on the surface it would appear the secondary carrier's 20%, actually represents 33% of Medicare's cash flow. If that's the case, nothing short of a bull in the China shop will dislodge the preposterous dual-insurance system. Furthermore, it seems likely this cash leverage is playing an important hidden role in the ACA negotiations with large group employers. Eventually, this leverage is what might threaten ACA with disruption, but that particular issue gets us off the topic of Medicare, though the issues sound similar.

Having earlier reviewed the finances of the 80% of Medicare, and found that financing it is rather precarious, let's look at the more modest goal of financing the 20% co-payment insurance with the available resources. That's a more modest goal, and a more achievable one, one which would at least remove a large source of public confusion and dissatisfaction. It might, for example, explain why it takes weeks or months for a computerized "explanation of benefits" to appear at the patient's home after he has long since forgotten the charges it matches.

* * * The main purpose of eliminating the Medicare co-pay feature is to eliminate the extra cost of a second insurance administration. Once you grasp the unlikelihood that a copayment would affect utilization if you only feel its impact after you go home from the hospital, you see the argument that it does not affect inpatient behavior. Outpatient costs might be another matter, although even that has not been demonstrated, and the alternate use of debit cards by Health Savings Accounts seems to point in the other direction (see page ). The conclusion would have to be that you have two choices: reduce the duplication of insurance companies, or reduce the duplication of policies. Just exactly which approach would save the most money requires greater access to the data and more expert analysis. Superficially, it seems likely the outpatient use is greater among younger people, resulting in a greater saving after compound interest is applied. A change of this magnitude requires more investigation than nonprofessional outsiders are likely to provide.

Nevertheless, eliminating the copay in some manner would provide a leveraged advantage. The extraction of the cost of the last four years of life would cut Medicare direct costs by 50%, and the elimination of copay would reduce it further. This is an example of the sort of leveraged cost reduction we have in mind. Migration of the center of medical care, from the hospital to the suburban retirement village would be another.

If we were commercial insurance investors dealing with a failing health insurance partner, no additional money infusions would seem sensible until Medicare stopped losing so much money. Because we are talking about a government program however, we must resort to the stance that a new program does not have to accept old debts, only new ones that it had a hand in creating. Therefore, this proposal does not include the repayment of old debts, regarding them as the government's problem to resolve. In many ways, Medicare was a noble achievement, but even the richest country in the world cannot afford to run a 50% deficit indefinitely, in an entitlement program grown so large. Undertaking to correct its mistakes does not imply assuming its debts. Furthermore looking forward, a looming retirement funding crisis, or at least equal size, threatens to replace it as the largest consequence of its heedlessness. Was this lengthening of longevity by thirty years a bad thing? Of course not. The bad thing was to let finances get into their present state before addressing them. The bad thing was to kick the can down the road, for fifty years. Because so few people seem to understand them, let's next review a quick summary of Medicare finances.

The Basic Funding Structure of Medicare. Approximately one-quarter of Medicare is paid for by its premiums, often derived from reduced Social Security payments, (a circular solution, if you regard prolonged longevity as a hidden cost of Medicare). Another quarter of Medicare is paid for by a 3% payroll withholding tax on younger, working people. (Unfortunately, this money is immediately spent, in a process quaintly known as "pay as you go"). And finally, half of Medicare expense ($260 billion annually) isn't paid for at all, it's just debt, initially laundered into general taxation and then floated away by bond issues.This completes our proposal for refinancing Medicare. The first step is to eliminate the supplemental copayment burden by substituting pre-payment for the 20% revenue, and meanwhile letting small front-end investments grow to appreciable size for the remaining 80%. Until we see what must be done to integrate the ACA with the rest of healthcare, it's likely to use up our political capital with the public, just to make that start. Secondly and later, it reduces itself to stabilizing cost increases by first investing the float created by the J-shaped cost curve, combined with cutting forward-financing loose from the debts of the past. Even a program allowed to concentrate on its 50% forward shortfall, must employ some novel approaches to produce annually $250-300 billion in either cost cuts or new revenue. We suggest compound interest is entirely capable of achieving it mathematically by making a total stock market investment starting at birth and continuing to death, or even 21 years after death. All that is necessary to do it on paper is to invest sufficient money at first. Unfortunately, there is an invisible limit to how much the populace is willing to tolerate as an investment, even on such bargain-basement terms, which I postulate to be about $500 per newborn child. Will that suffices for a 65-year investment? Possibly. Will a hundred-year investment cover it? Almost certainly. Do we as a nation have the patience for a hundred-year investment or the degree of honesty in our agents to leave such huge amounts un-pilfered for a century? That's far less certain.Suggested Solutions:

1. Extract Income From the Float. To attack the problem we would probably need to do many complicated things, but the first step might be pretty simple. We once contemplated a transfer-entrant into this revised program be required to sign an authorization to redirect payments for Medicare cost on his behalf to his own Health Savings Account. (Incidentally, it might also include an accounting of copayments and subsidies.) From the beneficiary's point of view, nothing changes except the postal address of his payments, which becomes his Health Savings Account. If he is between the age of 25 and 65, his withholding tax is so directed; if he is already on Medicare, it is his Medicare premiums. That's a payment stream which stretches sixty years, overall. Depending on his present age, first it is one, and eventually, it is the other. That wasn't so hard, was it?

The money now starts to earn investment income, which is new money for the program, with the surplus eventually going through the Health (and Retirement) Savings Account into retirement funds. One way of looking at this rearrangement is to say the beneficiary has been given the money to pay his bills but relieved of the obligation to pay old debts. He has also been given extra latitude to invest the income and use the profit to fund his retirement. What does the government get out of it? It potentially gets an abatement to annual increases in debt, plus the hope the retirement incentive will restrain cost escalation. If you wish, you could say the principal value to the government is creating the incentive at the end of this and other programs which join the string of pearls. Meanwhile, both parties can pray that science will reduce future medical costs, not raise them. But however it turns out, this solution, unfortunately, does turn out to be too small to make a significant change in the management of Medicare's debt, so we go on to other approaches. However, it raises an interesting point for a brief digression:

Using the shorthand that Health Savings Accounts ought to produce at least a 7% return, and money at 7% doubles in ten years, a quick look at pre-financing present Medicare payments overall is a little disappointing. In the Secretary's report, Mrs. Sibelius tells us annual Medicare expenses are about $560 billion, and cash revenue aims to be half that, or $280 billion. If the cash revenue only resided in the individuals' HSAs, it might add 7% revenue or 19.6 billion per year. That sounds like a worth-while amount, and it could be approximated it would apply to each yearly age cohort for 65 years (45 years of wage withholding, followed by 20 years of Medicare premiums). Since the system has been in place for many years, it has reached a steady state, net of demographic and economic variations. So an age cohort would collect a lifetime average of 65 x 19.6, or $1,274 billion, or 1274 divided by 500 million individual recipients or $2548 per lifetime. It certainly sounds as if the maneuver would be worthwhile because the government would be no worse off, and the subscriber would have $2548 more in his HSA.Additional Proposals to Supplement Medicare Income. Since Medicare is so underfunded by its revenue, the hope of extracting additional income above 7% is pretty dim. Therefore, the hope of significant cost abatement must come from three other proposals, all of which require the investment of fresh funding. That is, they are investments, not miracles:But Michigan Blue Cross has estimated the average person spends $350,000 per lifetime for health, half of which is covered by Medicare; and so 25% of that is Medicare revenue. Even by the roughest sort of estimation, this proposed re-direction of revenue would save less than 1% of the cost of Medicare, because revenue is such a small part of the cost. To put it another way, this approach might be an important funding device if indebtedness were not such a large part of Medicare's budget. We have not calculated the effect of compounding, which might theoretically reach several times its original size as stated revenue. On the other hand, neither have we recognized the annual increase in Medicare spending, which its trustees report to be 5.7% per year. Both 7% and 5.7% are fragile projections of the future, one of Medicare spending and the other of the stock market. As long as annual increases in cost are so close to investment revenue from cash revenue, any hope of substantial investment revenue is at the mercy of minor yearly volatility. and cannot be relied on. The best to be reasonably hoped for this proposal is to stop the growth of Medicare deficits. It should be done, nonetheless, but there is no great political advantage to be gained from emerging with the problem apparently unchanged.

The second weakness of this approach is a variation in proportionality between revenue and expenses among various government programs. Last year, the Social Security budget was $888 billion, while the total Medicare budget was $618. A quick glance at my secretary's pay stub reveals she has five times as much withheld for Social Security as for Medicare. The approach of investing the withholdings until the day they are spent is a good one. But if widely applied, would have drastically unexpected consequences unless other things are changed.

2. The Second J-Shaped Curve, Within Medicare. All healthcare costs with the exception of premature birth, genetic disorders and the like, are migrating to older age groups. One of the main sources of disruption is the migration of costly illness from working people to people on Medicare.

But even within Medicare, costs are also migrating into later life. Half of Medicare costs are paid on behalf of the last four years of someone's life. Since Medicare extends about twenty years after retirement, half of the total Medicare cost would vanish from its annual budget as a result of placing this burden somewhere else. This might be called the Last Four Years of Life Reinsurance, a component of the First and Last Years of Life reconstruction of healthcare finance, to be described later. The consequence is partly funding forward toward death, partly funding backward toward childbirth, and so reducing the transition time. The present system, it may be recalled, always funds forward toward death, and buries childhood in "family" plans. That's the background.

But death is the end of the line; costs can't get pushed any later, although curiously, revenue just might be. Therefore, the unique features for transitioning Medicare to some other system reside not only in the universality but also the finality of the cost of terminal care. This entity has a soft lower border, but we know that half of Medicare costs are concentrated in the last four years of life, creating a simple surrogate, although not a pure one. Paying this version of terminal cost separately allows the remaining cost of Medicare to be cut in half, by spreading it over the remaining sixteen years. Transition time is also halted. Moreover, smaller pieces are considerably easier to fit into a transition scheme, so the ultimate product fits the cost curve more comfortably. By the way, the last years of life are not the same as the last years of Medicare, and can only be calculated in retrospect, after the death of the individual.. This is the reality which allows one insurance to be paid out as costs are incurred, and a second, a re-insurance, to repay the first one after the facts are in. Funding the re-insurance from birth allows compound interest to pay for most of the magic in a forward direction. And making obstetrics/pediatrics into a gift from a parent to child, allows it to fund backward. Now, we are beginning to approach the way Nature makes us pay our bills.

3. Contingency Fund. But wherever is this money, half the cost of Medicare, to come from? Terminal care is predictable the day you are born, so you might as well fund it when it is cheap. A separate fund could be imagined, but for simplicity, we lump terminal care financing into a general contingency fund. So we next propose to complete the Medicare revenue issue by adding a contingency fund, essentially substituting a subsidy of $1 at birth for a deficit sixty times as large at age 65, and depending on compound interest to make up the difference. (It may well require about $100 up front, but less if we extended its duration by two or three decades.) How fast it would actually grow in the intervening 65 years would become evident before then, and appropriate adjustments made, but the person or agency to make the decision should be specified with care. The sixty to one estimate comes from 7% doubling principal every ten years, 2,4,8, 16, 32, 64 doublings in sixty years. How much to begin with is actually the last calculation, adjusted to balance the books as experience gathers to improve the estimate, and adjustment applied to its duration.

4. Extended Contingency Fund. The contingency fund ending when Medicare begins might anyway generate a 64 to one magnification of the initial deposit. However, it could extend to 250-to-one if its boundary were the day of average death (now 84) or 1000 to one if it added 21 years to the date of death and ended where the common law now says perpetuity begins (one lifetime plus 21 years). Innovations of this sort make many people squirm, but the underfinancing of Medicare in the past leaves little opportunity for conventionality in the future. All of this magic is a function of the mathematics of compound interest; objections to it are sociological, not mathematical. With leverage of 1000 to one, it is difficult to imagine an inability to pay the front-end $100, when $100,000 is so far in excess of what actually seems needed.

Sweeping proposals of this sort, however, do tend to dump their problems at the far end, so the ultimate goal is best stated to be funding part of the individual system backward to childbirth, partly forward to death, and still having a contingency fund for safety. That is, the system as a whole may be volatile and require internal borrowing, but each individual HRSA ends up with balanced books. By implication rather than calculation, in ninety or so years, you get rid of the Medicare debt. That's approximately how long it took to create it, too. The system does not "cover" retirement, except perhaps for bare-bones Social Security. It merely closes the individual books after death as described in other sections. Last-Year Coverage is also designed to save money, and thus eventually to generate some funds for retirement, but not likely at first. First and Last Year re-insurance is intended to resemble an accordion, quickly going to the first 25 years of life and the last 4 years of life, then slowly adding other years in the middle. Somewhere along the line, it might even shrink somewhat. At the moment, it appears terminal illness usually lasts four years, a process which might be thought of as "breaking the cocoon of health". Half of Medicare expenditure occurs in the last four years of life, leaving quite a surplus when the other sixteen years of cost are redistributed. In any event, the "accordion" effect is available for use in the transitions.

How Would This Combined Approach Make Medicare Solvent? Medicare has become so over-extended that conventional approaches are soon exhausted. Like any other proposal that might work, this one relies on approaches which are usually best avoided. First of all, it depends on such long time periods that unexpected events would be the rule, not the exception. Many Congresses of many political parties would have to understand it and leave it unharmed for a century. Secondly, such huge amounts of money are involved that tampering, embezzling and fraud are not merely possible, but inevitable. These two problems would confront any reformer. From these two obstacles emerges the third one. Individual Health Accounts would have less risk than gigantic single payers because some people will be stupid, reckless and venal. If you make up your mind in advance that you will rescue everyone who doesn't succeed, the whole system will be no better than a single gigantic reinsurer overseen by either an idiot or a crook. The opportunities for illegal gains will exceed the opportunities for honest managers. Therefore, smaller is better than bigger, simpler is better than complicated, and success is never guaranteed.

Medicare, possibly fundable, retirement income, probably not. To do the quick math in your head, it is useful to remember money at 7% doubles in 10 years. The Medicare deficit doubles every fourteen years. Since Medicare revenue is half of its expenses, its revenue invested at 7% would generate 3.5% of expenses, or just about enough to cancel out the annual rise in the deficit. Current interest rates do not achieve that, but current rates seldom do. During the eight years of the Obama administration, low-cost total market indices averaged 11% gain. Much of this never reached the average stockholder because the finance industry absorbed it, but things seem to be changing quickly. The pharmaceutical industry may possibly be over-represented in the index, but we are proposing to make the average patient become an average stockholder. Let's take the four components:

#1. The Contingency Fund. is designed to be overfunded for contingencies, so it is hard to say how much it should be. The most conservative investment period would terminate at death, but expand to whatever age is necessary, up to age 105. That means the $500 initial deposit never varies. Congress might, however, decide to vary the initial deposit to use a shorter time period. It makes no mathematical difference, but its political difference might be considerable.#2. Delay Liquidating the HRSA at death. Although things get a little threadbare beyond this point, there is no reason to hold back borrowing for a purpose. We are at the point in the compound interest curve were holding the funds for ten years after death would multiply the original subsidy by 128 instead of 64. We are paying the Chinese much less than that for the Treasury bonds, and they would probably be greatly relieved to see a way of recovering their investment. It may not sit very well with some people, but it would surely guarantee repayment. At the moment, repayment looks rather doubtful.

#3. Investing the Pay as You Go. The problems created for others in the payment process have to be reckoned with. We propose the individuals continue to pay/go temporarily for half of the withholding tax receipts, effectively unchanged because half the cost has been transferred but the withholding tax revenue remains constant. What is essentially involved is to balance the problems of the current budget staff against the problems of passing acceptable legislation. But once more, the mathematical "sweet spot" is comparatively easy to calculate, but the political effects are more intangible. It is probably impossible for an outsider to have a firm opinion.

Additional unknowns in this equation are how much nursing home costs from state Medicaid plans would eventually emerge as Medicare deficits. It is common knowledge that although custodial costs are not allowable costs, states have found ways to make them a federal responsibility. We also understand the HRSA owner may get less than 7% income on his deposits. Although the Chinese debt would stop rising, past indebtedness remains unpaid. Current Medicare bills would have to be paid for probably another decade, and may well rise in size. Ultimately, the way to balance the books is to raise the contributions. So, privatizing Medicare might or might not make it cost less, but would greatly relieve its present costs. Funding for past debts will have to come from other sources. However, contributions from the two contingency funds could easily be increased.

#4. The Last Four Years of Life Half of Medicare costs appear in the last four years of Life. By reimbursing Medicare for the last four years from other sources, Medicare's average cost is cut in half. but the withholding tax remains the same. Therefore, we come closer to breaking even in several decades, although we probably won't quite make it.

#5. Simplicity, Simplicity. To begin with the opposite of simplicity, two quite unacceptable new ways to manage the medical payment system suggest themselves. One alternative is to consolidate the whole industry, with one corporate administrative arm assuming the payment tasks for everybody, along with the whole delivery system. That scarcely seems appropriate management for a health complex which is already too big to manage. But it seems to generate many current proposals, especially those coming from the bureaucracy itself. Another idea, based on its resemblance to whole-life insurance, proposes a giant company or government department to concentrate on health finance, doing it for everybody. It might seem suitable for an insurance company, a medical school, a computer company, or a medical society. That seems to be what these organizations would like, but it immediately creates additional complexity, because computers only work if you specify some response to every contingency in advance. In a sense, this version of "Single Payer" would be a throw-back to the days when only a big company or a big government could afford to own a computer.

Is medical finance really so complicated most people couldn't handle it by themselves? Let's remember the anguished words of the Tzar: "I don't run Russia. Ten thousand clerks run Russia." What the Tsar was saying, was the problem isn't individual complexity, the problem is the huge volume of simple problems. For example, if we proposed to butter everybody's bread, it wouldn't be hard to do, it would be hard to manage.

Transfer Slips, and Monthly statements, Only. So, yes and no to computers, which what all this amounts to. Abundant cheap computers tempt us to use them for simple tasks, at the risk of making the simple task complex. (In another generation, a self-correcting code may correct this problem, at the same time it widens the opportunity for vandals.) The proposal made here instead is a confederation of otherwise free-standing organizations (The Pearls), hiring their own experts, feeding into a common channel of Health Savings Accounts owned by individual patients (The String). Individuals could hire consultants if they pleased but the decisions should be so simple the average high school graduate could cope with them.

Is medical finance really so complicated most people couldn't handle it by themselves?

There might be many networks, as long as their balances are uniformly transferable and they each link ultimately to a transferable retirement fund (The Goal) and a transferable investment fund (The Multiplier). Such networks might grow very large, but still, remain quite simple, and decisions which belong to the patient would remain within his control. The only outward purpose of such paperwork would be to transfer credits of the owner to debts of the same owner or vice versa, with the adjusted balance ultimately coming to rest in his retirement account, creating a common incentive to be medically frugal. They would maintain adequate records (which mostly no one ever reads), an information source, and a designated HSA representative, but their outward form and purpose would remain recording a transfer slip. If you want a simple system, give it to individuals who have an incentive to keep it simple. Don't give it to people who have an incentive to make it complicated.

This particular feature has a political element. The American public now imagines it gets a bargain with Medicare, somehow getting a dollar of healthcare for fifty cents, and therefore a treasure they are unwilling to surrender. In all probability, no organization except the government could function long with such a deficit, so taking the deficit away from the government necessarily places it in the hands of someone who must balance his books. Somehow, legal protections for the patients against the debts of organizations which participate in the confederation must be established, so they can occasionally provide benefits at a loss, but only within stated limits. Called a "loss leader", the situation is a common one. Two additional savings multipliers must be added, although they will be explained shortly, along with two important investment designs. There are four large sources of new revenue within Medicare:

If you want a simple system, give it to individuals who have an incentive to keep it simple.

Investment Mechanisms.We promised to discuss two investment mechanisms which might help matters. The first is the tendency of compound interest to rise with time. We have already shown above that adding another decade to the example will have an exaggerated effect on the outcome. This is an inherent quality of compound interest which crept up on us as science has conquered early death, and should have wide application in the future. As we learn how to avoid borrowing and learn how to be successful creditors, it should become a commonplace to rearrange financing to optimize it.