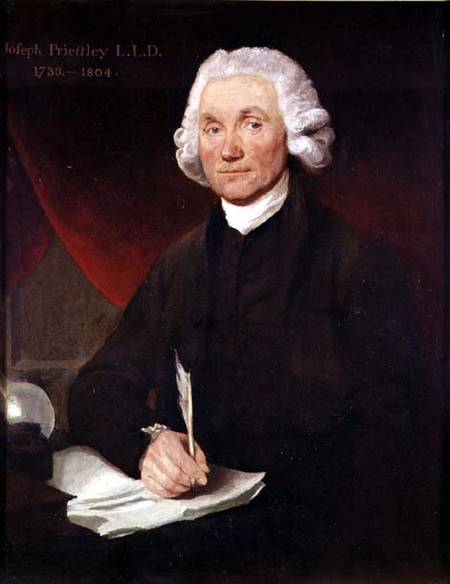

1 Volumes

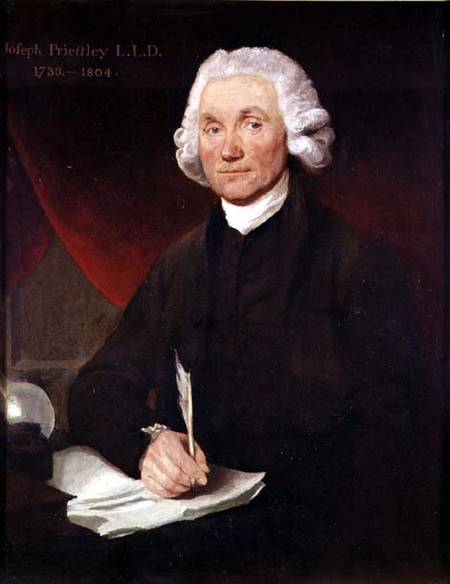

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Central Pennsylvania

"Alabama in-between," snickered James Carville, "Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Alabama in-between."

Appalachian Geography

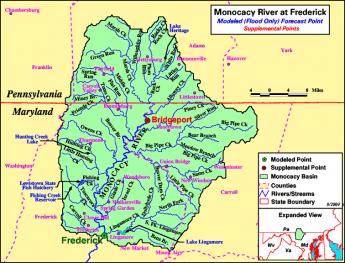

Let's sketch the geographical skeleton of eastern North America as a strip of land from the Arctic Ocean, down through Central Pennsylvania, to the Chesapeake Bay. The Bay is essentially a southern continuation of the Susquehanna River so this area might be described as the Susquehanna watershed, extended.

|

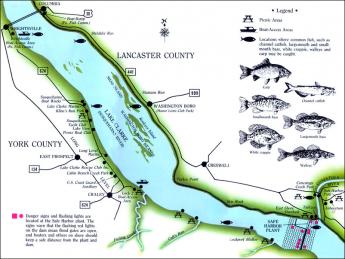

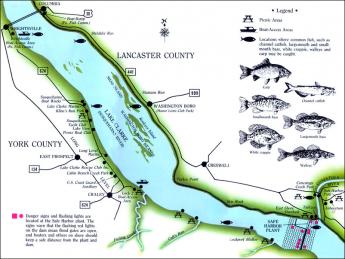

| Keystone State Water Ways |

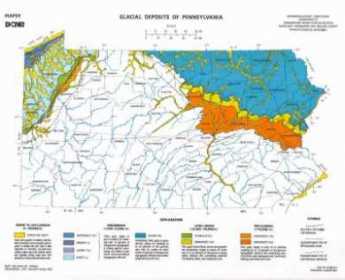

Cold air blows down from the Arctic to the Great Lakes where it picks up a lot of water, which then gets dumped on the snow belt of Upstate New York, as well as on the formerly glaciated mountain basins of the Appalachian mountains of Pennsylvania. Geologically, this once created a large inland sea, until the water broke through the mountains through four main water gaps. The most obvious ones are at Pittsburgh, West Point NY, and the Delaware Water Gap. The Susquehanna is so large it has several water gaps, notably above Harrisburg, at Northumberland, and Sayre. This huge drainage area percolates streams down the North-South mountain ranges, flowing into progressively larger river branches which finally drain into the Northern tip of Chesapeake Bay, and thence out to sea at Norfolk VA. The mountainous areas are several hundred miles wide, so the western collection area flows into the Allegheny River and down to the Mississippi, while the Eastern mountain area collects water that flows into the Delaware River and out the Delaware Bay. Since the mountain ranges bend to the East above Pennsylvania, there is even a Northern runoff draining into the Mohawk and Hudson River basins. This huge water-collecting system thus fills four major rivers along the Atlantic coast, and along with astonishingly deep winter snowfalls pumps major amounts of fresh water out to sea. The central river system in this whole area is the Susquehanna. As far as bird migration is concerned, it extends up to the Arctic Ocean, and a few bird species go on South to Patagonia. The birds are up where you don't see them much, but the quantity of bird life is huge. At one time, the fish migration was equally immense.

At the moment, there is a strip more than a hundred miles wide, covered with a forest of mixed hardwood and conifers; there are little towns and a few fairly big ones, but large stretches where ten persons per square mile would seem populous. Because of the recent boom of shale gas prosperity, most of the houses which were sort of tumble-down and in need of paint five years ago, now look brand new. Some of these houses are prefabricated, many were probably only reshingled with new siding in the past couple of years, but they look new to a passing tourist. The roads are mostly quite good, looking recently repaved and graded. There are hundreds, possibly thousands, of trucks hauling pipe and wastewater for the comparatively simple process of pumping in water, to drive out the pockets of gas, and then collecting the gas in pipelines.

Naturally the sudden gold rush, or shale gas rush, excites two varieties of comment: about the great good luck for the locals, and about the drastic threat to the environment. This is the forest primeval, but it won't be primeval for much longer, goes the lament. But there is a third sort of reaction, which only emerges slowly, after learning that vast areas of this pristine forest were burned to the ground in 1910, just one century ago. During most of the Nineteenth century, the main industry had been logging. Paul Bunyan lumberjack stories abounded at the time of the First World War, as the trees were cut, collected, and floated down various rivers in the spring log rafts. Railroad ties were a large destination for such wood and houses and barns for new settlers. The really tall and straight logs were floated down and around to Camden, where they became the masts of ships. It is said a major battleship of the Revolutionary period might consume 800 trees. But those big trees had been shading and protecting the smaller ones; once the big ones were gone, the region became vulnerable to forest fires. Major forest fires even destroyed the topsoil by erosion, after first burning off the protective understory. The long and the short of it is that this place was a virtual desert in 1910. It may have been a primeval forest before the lumberjacks arrived, but it was only a burned out desert within the memory of our grandparents. So even if the shale gas industry ruins the landscape a second time, turning scattered settlers into near-millionaires and all of those other exaggerated reactions, pro, and con, it may not be so bad. The forest spontaneously recovered from worse devastation than that, only fifty years ago. As a matter of fact, it has gone through three ice ages in the comparatively brief interval of 20,000 years, grinding those craggy ridges down to graceful bowls. That's no reason to be careless and profligate. But it's doubtful that environmental conditions will ever be as bad again as they were, only a century ago.

Headwaters of the Middle Atlantic Rivers

When Governor Keith suggested to some German wanderers that they might reach the Susquehanna River by walking eighty miles west from Kingston NY, he had probably never tried that route himself. Two mountain valleys converge toward Kingston on the west bank of the Hudson and were ideal routes for Indians to bring their furs to the Dutch trading post, later to become a whaling port. Taking the northern valley to arrive at what is now Cooperstown NY, the traveler discovers a beautiful mountain lake creates the Susquehanna River, much as Lake Geneva in Switzerland creates the Rhone, giving credence to the claim that Geneva is the most beautiful city in the world. Alternatively, taking the more southerly valley west from Kingston brings a traveler first to a mountain bowl from which several creeks run in different directions, before descending to what is now Oneonta on the Susquehanna. Just which valley the twenty-five German families actually followed in 1687 or so, is presently uncertain but either route would get you to the river after hiking about eighty miles. From either place, it is possible to float about four hundred miles downriver on a flatboat, to the famously rich topsoil of what we now call the Pennsylvania Dutch country. If you took it today it would be a terrifying ride, and in the 17th Century, it must have been much more so. First, you go south, then north, then west, then southeast, then southwest, then southeast again, as the North Branch of the Susquehanna finds openings in the mountain ranges, eventually emptying into the Chesapeake Bay four hundred miles to the south.

The reader may choose to follow that route (by automobile on roads closely paralleling the river), for which, clicking on the Philadelphia Reflections Topic called German Immigrants via New York are comments on the three hundred years of history that subsequently affected this first, founding, westward frontier. But it's still a mountainous wilderness for the most part, quite effectively dramatized in the movie How the West Was Won. The history of America was once regarded as the history of a moving frontier; the one which began here and ended up around 1900, in Arizona.

|

| Delaware River |

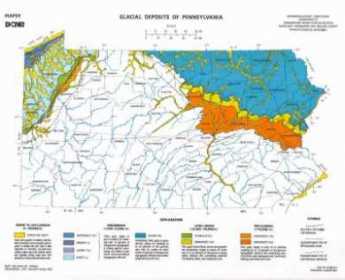

So focus first on the Mid-Atlantic tri-river watershed, the eighty-mile area west from Kingston NY. Some collision of ancient plate tectonics caused the North-South Appalachian mountain ridges to bend sharply at about the level of New York City, resembling a jumble of little mountains which subsequent glaciers ground down and smoothed out. The series of vertical ridges we call Appalachia more or less all bend sharply eastward at this level and the rivers consequently run in various directions, away from that center. The watershed of the Hudson runs along its banks for a few miles, the Susquehanna finds its way among the mountains eighty miles to the west, and Delaware gets snuffed out between them. When things sorted themselves, the streams had found their way into three main pathways, roughly parallel as they flowed south on their way to the sea. There's another way to look at the result. When the prevailing winds blow cold air from Canada across the Great Lakes, they pick up vast amounts of moisture which is dumped on upstate New York in huge winter snowbanks, or simply rain and fog the rest of the year. This massive rainfall system generates the water for three large river drainage systems. There's one more point of amateur geology: the advancing glaciers scraped the topsoil from the top of the land down to and over the mountain ranges and then dumped topsoil on the southern Pennsylvania counties as they receded. The German settlers of our story were seeking to get around the rocks and pebbles in order to live in eternal happiness in Lancaster County, PA. Governor Keith had somehow been told of this geography from Indian tales, and the scattered reports of white explorers confirmed it. You have to be pretty desperate to stake your family's survival on such reporting.

In any event, the settlers did give it a try, taking either the northerly or the southerly passage out of Kingston. Present hindsight suggests the southern route was shorter, but the northern route was more scenic. So scenic in fact that two prosperous residents of 18th Century Philadelphia bought up large tracts of land. Judge William Cooper of Camden (father of James Fennimore Cooper) bought 10,000 acres around Cooperstown, and William Bingham bought up a region he never visited, now called Binghamton, NY. The area is also noted for the much later construction of the main IBM calculator factory, and for the fact that I was married there, immediately spiriting the local girl back to Philadelphia where I belong.

Wellsboro: Grand Canyon

|

| Mary Wells |

Robert Morris bought a million acres of land in upstate New York and north-central Pennsylvania at the end of the Revolutionary War, and sold it at a considerable profit. Unfortunately, it gave him the wrong idea about real estate investment, which led him on to his bankruptcy and spell in debtor's prison. Benjamin Wister Morris managed the section around what is now called Wellsboro, named after his wife, Mary Wells. Because of the path of westward migration and the flourishing of the lumber industry, the area prospered, so the town grew to a population of 54,000 in 1890, although it looks to be about half that at the moment. However, it is the local cultural center, attracting hunters and fishermen to its nice hotel and numerous restaurants. Wellsboro has schools and stores, a movie house and annual festivals promoted by the Chamber of Commerce. There's an annual auto race, for example, and periodic art displays. With the coming of the Marcellus shale gas industry, Wellsboro is likely to become the local center of activity, but at the moment, the locals are too busy renting out their rooms to truckers to have expanded their cultural dreams much further. In another five years, this town might well blossom.

|

| Pine Creek Gorge |

A few miles away is the Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania, more officially known as Pine Creek Gorge. There are now several lookouts on the rim, with quite an exciting view from above of eagles, buzzards, ospreys and similar birds of prey, soaring over a thousand-foot canyon down below. Naturalists and environmentalists since Gifford Pinchot, Teddy Roosevelt and other more recent ones have been attracted to this mountain scene. It has its own local author of note, George Washington Sears. Pine Creek runs for sixty miles through this gorge, particularly attracting trout fishermen; easy access to the creek is found at Colton Point Park. Access to the outlooks on the rim, as well as the creek at the bottom, is fairly easy but is not particularly well marked. Right now, it's best to drop in on the Wellsboro Chamber of Commerce, or at least to the AAA, before you go there.

|

| Boal Mansion in Boalsburg |

There's an interesting short movie provided in the lookouts, telling the history of the place, and the abundant wildlife; well worth seeing. Like the Copper Canyon in Texas, this canyon tends to disappoint visitors expecting something like the Grand Canyon of Colorado, because it is covered with trees from top to bottom. In addition to the fish, game and birds the attraction of this canyon is to see the creek winding seventy crooked miles through the mountains. Unless you get up high enough to see over the tops of trees, the vista may be hard to make out, so do what you're told and go visit the places the park rangers have provided. Other places to visit "nearby" are the Cherry Valley Astronomy Center near Coudersport, the Asylum for Marie Antoinette near Towanda, and the Boal Mansion in Boalsburg near State College. It's a two-day trip, and whether you think it is worth it will depend on how interested you are in some grand views, your interest in seeing for yourself what the Shale Gas uproar is all about. And in the case of Boalsburg, some perfectly astounding history. Where else can you find history about Robert Morris, Marie Antoinette, Christopher Columbus, and the origin of Memorial Day? Have you seen the place where Joseph Smith wrote the Mormon Bible? Do you know what a Scotch-Irish diamond is? Stay at home and watch football on TV if you must, but a two-day trip around Central Pennsylvania is something you wouldn't soon forget.

Cornell, For the Birds

|

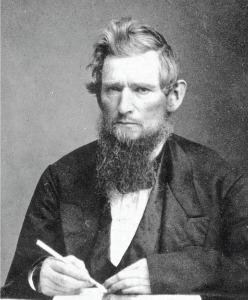

| Senator Ezra Cornell |

Cornell is in Ithaca, at the foot of Lake Cayuga. It's New York's land grant college, which at first seems a funny way of expressing it, until you learn that during the Civil War, Congress declared that at least one college in each state would receive a grant of federal land (which they could sell) for advancing the working class through agricultural and mechanical education. Cornell is thus New York's "A and M". The whole idea is central to the Whig philosophy that social classes were not a permanent status, but rather only stages in the evolution of penniless immigrants into managers, and thence into entrepreneurs and owners.

|

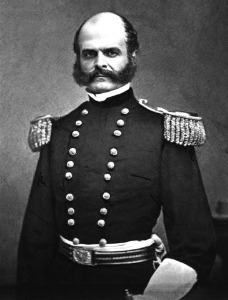

| Sen. Andrew White, President |

The Whigs didn't hate poor people, they just wanted to get rid of that class by showing them how to get rich. Although the Republican Party was largely the successor to the Whig party, Lincoln remained philosophically an ardent Whig; the emancipation of slaves was a bold and imaginative extension of the Whig ideal. The striking thing about the founding of Cornell University is that both of New York's U.S. senators were enthralled by the land grant college idea. Ezra Cornell drove the legislation through Congress, and Andrew White became Cornell's first president; both of them devoted their later lives to it. Cornell donated most of his substantial fortune to its establishment and applied his unusual financial talents to investing the proceeds of the land grant.

|

Devotion to self-improvement of the working classes helps explain why many of Cornell's departments sound a little out of place in the Ivy League, hotel management being the first to come to mind. However, it must have been the two senators who instilled in this project the idea of striving for excellence. If you manage a hotel, be the very best hotel manager in the world if you have it in you. Very likely that's the bug that bit the Johnson family, whose name is on the Johnson School of Management, the Johnson Museum. And the Imogene Powers Johnson Laboratory for Ornithology, which is our present topic.

|

| Cornell Laboratory for Ornithology |

They say it took the architects six years just to design the 80,000 square foot building overlooking the wetlands on 220 acres of the bird sanctuary, otherwise known as the Sapsucker Woods. The public doesn't often see most of the interior of the building, which is devoted to working scientists, and their extensive effort of computerizing the voluminous efforts of volunteer bird watchers up and down the Appalachian Flyway. The result has been a set of coherent conclusions about what is happening to ecology, as illustrated by ornithology. That's only one of many scientific projects underway. What the public does see are two things: the most elaborate bird-watching museum anywhere, and one of the most imaginative bird-hobbyist stores. Between them, these two features are designed to make a bird lover out of the meanest curmudgeon, show him how to arrange an indoor watching area, buy books and magazines about how to do it, and offer for sale the most advanced and clever devices and supply. If you hate birds, or even if you are merely indifferent to them -- this is the place to come to Jesus.

La Cosa Nostra Has an Apalachin Outing

|

| Joseph Barbara |

It's hard to convince people of something they don't want to believe; others are simply determined to deny they already know it. In any event, prior to 1957, it was vigorously denied by many Americans of Italian descent that there was any such thing as organized crime, The Mob, The Mafia, or La Cosa Nostra. One of the pieces of evidence for regarding organized crime as just an anti-Italian slander was the consistent denial by the head of the F.B.I. J. Edgar Hoover that a national crime syndicate existed. Just why Hoover took this strange position will have to be left to future historians. But even J. Edgar Hoover couldn't deny it after November 14, 1957, when New York State Police surrounded a hundred mob bigwigs, lieutenants, and bodyguards at Apalachin, NY.

|

| Sgt Edgar Croswell |

New York State troopers always kept a watchful eye on a fifty-acre estate belonging to Joseph Barbara the reputed boss of Central Pennsylvania crime, located just within New York state borders; it is not necessary to invent a feud with one trooper, or insist that some disgruntled criminal tipped him off. When all local motels were suddenly booked up, and dozens of expensive automobiles with out-of-state licenses could be seen parked in the estate, it was only prudent to check the license numbers. When the report came back that most of the cars belonged to persons suspected of leadership in organized crime, it was reasonable to establish roadblocks around the estate, just in case. And then, after a car sped in past the roadblocks, soon followed in reverse by dozens of adult males fleeing in suits into the surrounding woods, it was natural enough to pick them up for questioning. It's estimated that fifty of them got away, but 58 mob bosses, henchmen, and bodyguards were caught and indicted. Everybody, it seems, had heard that Joseph Barbara was feeling unwell, and they had come to inquire after his health. Local lore has it that for years, wallets filled with hundred dollar bills were to be found tossed into the nearby underbrush.

|

| J. Edgar Hoover |

A great deal has been said and written about what was really going on, although a lot of it is probably deliberate misinformation, and some of the rest is couched in "weasel words" intended as some sort of code. The present general opinion is that the old-style Sicilian Mafia had engaged in a war for several years with upstart "Liberals" and that this meeting was intended as a peace treaty of the "Crime Commission", for which some crime bigwigs from Italy had been imported as referees. Grander visions, including the extension of crime syndicates into Cuba, Las Vegas, and California were on the agenda but were not the primary agenda. It was rumored that Angelo Bruno of Philadelphia had been newly appointed to the Commission, and was leaning toward favoring the "Liberal" faction. Such a disruption of leadership as the Apalachin round-up naturally resulted in a large number of assassinations, imprisonments, novels, and movies. This was the final, undeniable, outing of organized crime. The mob was finally turning away from the giddy days of prohibition rum-running, toward more modern entertainments like recreational drugs, gambling, and loan sharking. The Sicilians were losing control to Italians and Jews. The public was going to movies and reading books; it was becoming inevitable that the "goddam innocent bystanders" and other do-gooders were going to demand that this sort of invisible empire simply had to be curbed

|

| Joseph Barbara's Place |

Just why Apalachin was selected is debatable. It's visible from the Interstate Highway, and state roads run by the estate. It's quite close to the Susquehanna River, for whatever value that might have to organized crime. It's, therefore, both private and remote, as well as within a couple of hours easy drive to most East coast cities. And its back road runs straight to Hazelton, which might seem a more natural place for the boss to live, except that Apalachin was just over the state line for legal purposes. The verbal history circulated within knowledgable circles is that the Mafia started in Sicily in response to resistance to Italian authorities, especially Garibaldi. When it got to be time to move, they first went to New Orleans. Unable to cope with the Ku Klux Klan, however, the pilgrims split into two main movements. One went to South Philadelphia, and the other went to Hazelton. After that, the links to New York, Chicago, and Las Vegas are obscure.

So, Apalchin is worth a drive-by. Those who are timid can get a fairly good idea from Google Earth.

Marcellus, Where Shale Gas Comes From

|

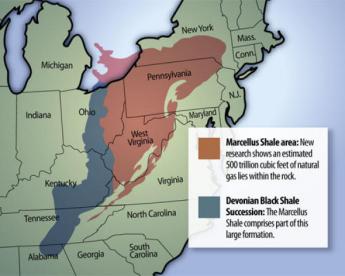

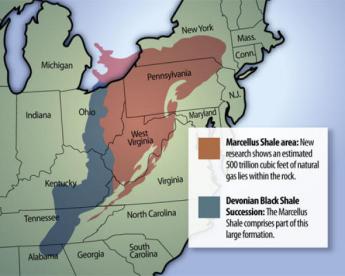

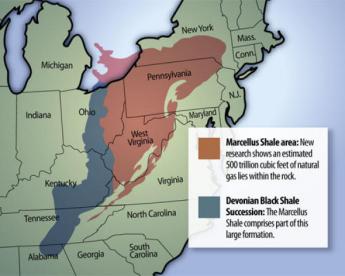

| Map of Marcellus |

The region of upstate New York called Marcellus stretches from the tourist jewel of Skaneateles to the Onondaga Indian Reservation, where you can buy untaxed cigarettes if you wish, and get on Interstate 81 to the Canadian border. Tucked within that region is the little town of Marcellus, which is neat and cute, but almost too small for tourists to notice. It's one of those remarkable things about scientists that someone in 1840 noticed a black shale outcropping in Marcellus, and recognized it as a distinct layer of sedimentary rock. Little did they know this tiny outcropping in Marcellus was part of a layer thousands of square miles in area, containing more dissolved natural gas than the peninsula of Arabia. Even if they had realized the extent of it in 1840, the technology for extraction had yet to be invented, and the price of gas had yet to rise to a level making extraction worth the effort. And also, worth enduring what has proved to be a hornet's nest of criticism by environmentalists. Patty Weisse, the most eminent local geologist, simply shrugs her shoulders and says, "It's going to happen." Since a number of prominent scientists are firm of an opinion that alternative forms of non-fossil energy will take at least fifteen years to become practical energy sources, public pressure to develop the "Marcellus" shale gas seems indeed pretty undeniable.

|

| Route 175/ Route 174 |

First, the tourist attraction. The original shale discovery has long since vanished, but there's a big hill outside the town, meaningfully identified as Shale Hill. Two state roads intersect at that point, Routes 174 and 175, so the highway engineers created some cuts in the shale hill. That's not exactly an outcropping, and something ten feet high is not exactly a cliff, but you can certainly find shovels-full of honest to goodness Marcellus shale within a few feet of the highway. No one objects if you take a piece of the stuff home with you, but in trying to do so, you will discover something important about Marcellus Shale. It easily breaks off in your hand, and if you drop it on the floor of the car, it will crumble into dust. You have now just observed why it is possible to extract gas from it with relative ease and expense. This formation is called Devonian because there is something like it in Devon, England.

|

| Marcellus Shale |

Mostly by volcanoes and glaciers, rocks get split into gravel, gravel gets ground into sand, and sand is ground into powder. Add heat and water to the powder and you get clay. Marcellus shale is a form of clay, with a difference that it was formed at the bottom of a huge lake by fine-grained rock particles slowly drifting down to the bottom, getting later squashed by vegetation, sand, gravel, and rocks. The vegetation ferments and permeates the clay, at the rate of twenty-five cubic feet of gas to a cubic foot of shale, and a cost to extract it off about a dollar a cubic foot. The economics of extracting it is quite attractive. The mechanism for extracting it is to inject lots of water through a drill-pipe, drain out the water, and let the gas flow. Getting rid of the dirty water is a problem we will return to in a moment. One surface well can be used to drain off the gas from many different underground directions, which reduces the surface spoilage considerably. If you have fiber-optic television cable, it was most likely installed underground by such "re-directional drilling", much like the operation of a colonoscopy to extract your colon cancers and polyps. Since gas has the smallest carbon emission of any energy source except those which have no carbon emissions at all, this seems like a godsend at a time of world-wide energy uncertainty. It can be stated without much challenge that no non-carbon energy source is or will be practical for another fifteen years, except nuclear energy. There is easily enough gas in the Marcellus shale to supply America's energy needs for fifteen years. If you don't like that, your choice must be nuclear, but the U.S. Government refuses to license any nuclear plants because of the dispute about radioactive waste disposal. And furthermore, while France uses a disposal method which is safe from that sort of contamination, their approach is easily transformed into nuclear weapons. It would thus emerge that our choice is between the French nuclear approach and allowing oil and coal to dominate. Atom bombs for everyone, or pollution for everyone. On the other hand, going ahead with Marcellus shale would give us relatively low carbon emission for fifteen years, on the prayer that wind and solar power can be made practical in the meantime. So, what's the matter with shale gas?

Three things. First, the heavy equipment used in drilling seriously tears up the landscape. The construction roads open up the wilderness to raccoons, snakes, and rodents of all sorts, which badly affect bird migrations. These aren't highways they are building; the soil erosion is fairly major. Secondly, "fracking" or injecting water into the shale formation uses up tremendous amounts of water, and could easily drain dry some lakes and streams, not to mention human water supplies. Since the aquifers are formed by flowing water boring holes along with the upside of an impermeable layer, the aquifers are right above the layer of Marcellus shale. If water runs dry, the chances are high that some driller will reach up into the aquifer for water, and claim it was accidental. Third and finally, the water which is washing around underground will inevitably encounter salt, minerals and radioactive materials. When the resulting brine reaches the surface, it won't be useful for inhabitants without extensive purification.

Patty Weisse, a geologist member of a whole geologist family and who runs the Baltimore Nature Center in Marcellus, tells us it is unnecessary to inject water into the upper half of the Marcellus formation in order to get the gas out, at least in the neighborhood of Marcellus itself. That leaves only landscape damage to contend with, and surely the damage from that can be minimized by thoughtful zoning. After that, it gets harder because, in the southern half of the formation, water must be injected. That means that anxiety is less around Marcellus itself than in Pennsylvania. But there is going to be some kind of environmental price to be paid, anywhere shale gas is extracted. If you can't stand any pollution at all, even nuclear, apparently your only practical alternative leads to just letting Iran and North Korea get their bombs. Or letting OPEC drain our economy.

Marcellus Shale Gas: Good Thing or Bad?

|

| Marcellus Shale |

Soon after discovering widespread hard and soft coal, Pennsylvania found in Bradford County it also had oil. Local oil was particularly "sweet", with a low sulfur content. Long after much cheaper oil (cheaper to extract, that is) was found in Texas and Arabia, Pennsylvania oil was prized for the special purpose of lubricating engines, which commanded a higher price. This discovery of oil in the western part of the state also provided a vital competitive advantage for local railroads. Other east-west railroads like the New York Central and the Baltimore and Ohio lacked a dependable return cargo like this, so the Pennsylvania Railroad lowered prices and became the main line to the west for a century. Refineries were built in Philadelphia, and continue to dominate Atlantic coast gasoline production, even though the source of crude oil is mostly from Africa. When oil and coal declined in use, Pennsylvania's industrial mightiness declined, too. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh lost much of their competitive advantage, while the center of the state just about went to sleep. When even Texas oil later ran low, America's industry turned to computer-improved productivity to keep its prices competitive, helping California at the expense of Pennsylvania. The bleakness for Pennsylvania may not last, however. Suddenly, we discover we have another enormous source of cheap energy, shale gas.

It's rather deep, however, even deeper than our supply of fresh water. The next layer below surface minerals is porous rock filled with fresh water, the so-called aquifer. Gas bearing shale is layered just under the aquifer. We'll return to the aquifer later.

There is and will be abundant oil in the world, well into the future; but cheap oil has been selectively depleted. When military and economically weak nations like the Persian Gulf had cheap oil, only transportation costs were irksome. But now Russia is emerging as an oil-rich state, previously impoverished states like Iran are asserting themselves, the existence of an international oil cartel becomes more threatening because it reinforces oil price with military threats. Raw material discoveries -- gold rushes -- are always destabilizing because they are tempting to the dictator mindset. That's known in the political literature as the source of the "Dutch Disease", not because Netherlanders are aggressive, but because North Sea oil discoveries destabilized the politics of even that little peaceful nation. America has now made a universal decision to establish energy independence. It once was credible to make predictions that in a decade or two, we would run out of competitively priced energy. To be both rich and weak invites aggression and we knew it.

|

| Gas Drilling |

There's little question America is profligate with its energy, so the need for energy conservation is undisputed. Actually, we are already five times more efficient with energy use than China is; furthermore, we have improved energy efficiency by 20% while China has defiantly worsened. We'll do better, but unfortunately, our immense investments in inefficient home heating and transportation are too costly to discard abruptly in both cases. There is also little question that American research and development of alternative energy sources has been neglected, while China is subsidizing R & D appreciably. In our frenzy, converting food into gasoline by subsidy is a bad joke, electric cars are subsidized and widely described as "Welfare buggies", wind power is twice as costly as carbon-sourced energy and needs better battery development to be able to store it, atomic energy has been encouraged by the French government, but totally held back by ours, in response to public anxieties. The long and the short of it is this: we face a fifteen-year period of doubtful energy sources, a vulnerability our international competitors and enemies might easily use against us.

And then along came shale gas, like a gleaming savior on a white horse. For seventy-five years, the world has known unlimited amounts of petrol carbons are locked into vast stores of shale. Unfortunately, it is buried deep, and located where it is expensive to transport to market. The techniques for extracting such carbons were unacceptably expensive in a world that shrugged off abundant oil. Politics and geology turned against us; we now need fifteen years of catch-up to make alternative energy sources more affordable. Cheap oil ran out before non-carbon sources became practical. But miraculously shale gas is now upon us, right here in Pennsylvania. It takes a long time to map out the existence of shale from Canada to Texas, when it is 8000 feet deep; it was first recognized in 1839 from a cliff outcrop around the little town of Marcellus, New York and vigorously explored in the disappointed hope it would lead to discoveries of bituminous coal, iron ore or other minerals. Land speculators have been roaming Pennsylvania for two centuries. Now, they are offering $5000 an acre plus royalties, just for the right to drill. In 2010, probably 5000 leases will be issued. Needless to say, the discovery is popular with local farmers, and "gas fever" has enormous political momentum. With techniques discovered around Fort Worth, Texas, about 10% of the existing gas can be extracted easily, serving America's energy needs for much of the 15 years required to make renewable, non-fossil, energy cheap and practical. This long history paradoxically accounts for the apparent suddenness of the current popularity; it's not a new mineral discovery, it is the development of practical extraction methodology at a critical political and marketing moment.

|

| Tree Hugger |

And equally needless to say, the environmental movement is being called to its barricades. Whatever is their objection to drilling for gas, 8000 feet below the surface of a wilderness? In the first place, just cutting roads through the forests is destructive to migrating and local bird populations. In a well-known process of "fragmentation", the cutting of roads allows an invasion of raccoons and similar bird predators. Forest fragmentation simply cannot be avoided if drilling rigs are to enter and leave the forests; some vulnerable bird species are bound to go extinct. This particular region is particularly prone to emissions of radon, which is a radioactive gas traveling along the stone layer and occasionally entering the basement of houses; will drilling through to the shale layer make radon seepage better or worse? Furthermore, since this sedimentary shale layer lies underneath the aquifer, drilling must go through the freshwater-bearing caverns before it gets to the shale; expensive sealing methods may be needed to keep the contaminants below from seeping up through and around the drill holes. The practice of fracturing the shale by high-pressure mixtures raises issues with water, sand, and chemicals. Water consumption is millions of gallons per year per well, seemingly enough to drain the rivers and creeks. Some operators will be tempted to use the aquifer as a surreptitious source of water, leading to consequences hard to anticipate. The sand is meant to support the walls of the rock fractures but may clog up other channels unintentionally. And the composition of the chemical drilling components is a trade secret which the extraction companies naturally wish to keep private; it's pretty hard to get public approval of a secret. So to sum it all up, there is a legitimate need to hurry the drilling, and there are legitimate environmental safety issues to be addressed, slowing it all down. New York State has passed laws prohibiting further drilling. Is that an opportunity for Pennsylvania, or a warning we should heed?

|

| Where's My Aquifer? |

This is a time for serious negotiation, and the spending of serious amounts of money on study and monitoring, not for shouting. Politicians sense you can't make omelets without breaking eggs. For them, it's a question whether to choose to be blamed for the inevitable problems of exploring new science, or whether to be blamed for lack of patriotism in a national emergency. The amount of heedless rhetoric is predictably extreme, and the money available to spin it is daunting. If there is anything resembling a middle road in this uproar, let's explore it. In the first place, some sensible discussion between scientists of both sides can be held immediately. Geologists are probably unaware of issues like forest fragmentation, while naturalists are probably unfamiliar with radon hazards and available drilling precautions. Some concerns are exaggerated, some are unsuspected; let's get the experts together quickly and establish most of the knowns and unknowns before popular media runs away with the issue. Let's get the responsible leaders of the gas extraction industry into continuous dialogue with the responsible leaders of environmental protection organizations, so wars they get dragged into are real and not hysterical. Let Congress consider the issue and appropriate funds immediately to study the issues everybody agrees need to be addressed. It seems very likely the huge corporations involved in this issue will rather easily agree among themselves on responsible positions unless they get rattled by overly vocal denunciations. Since this is a gold rush, however, it is also likely that underfunded small operators will start to employ short-cuts and rush heedlessly into dangerous territory; large operators will wish to have laws passed to restrain everybody, small operators will plead fairness. The more transparency this field has, the better. And the most immediately obvious area of resistance to transparency is the natural wish to protect trade secrets in the composition of drilling fluids. In time, the other continents of the world will develop satisfactory drilling fluids; the secret won't last long. The situation cries out for the large operators to negotiate among themselves so those who have an incentive to protect secrecy can tell us how to do it responsibly, while those with a political incentive to expose secrets can be offered time limits related to the how fast the rest of the world catches up. Politicians particularly need to be offered some mechanism for assuring the public about those secret injection ingredients.

Anyway, let's negotiate a way to take chances we have to take, but avoid the costly blunders of studying the issue to death. Hurry up, folks, it's a matter of time before problems have to be faced.

Great Bend: Joseph Smith Translates the Golden Plates

|

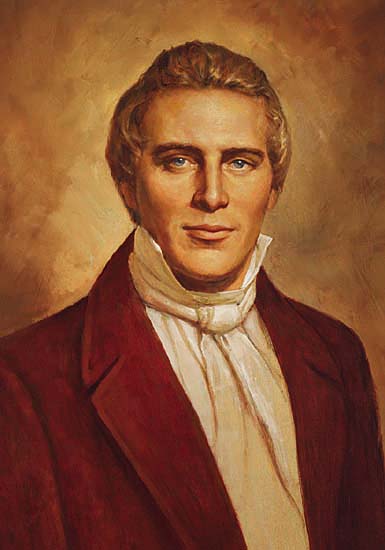

| Joseph Smith |

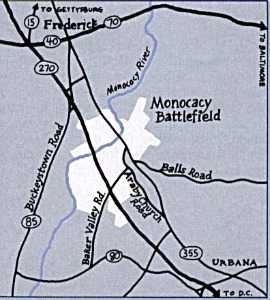

As the traveler up the Pennsylvania Turnpike Northeast Extension approaches the New York border, there's a chance for a fleeting glance at an exit sign pointing to Great Bend, without additional comment. The comment is definitely needed because a ten-mile detour at this point is rewarded by two interesting attractions. In the first place, the Susquehanna does indeed make a great bend there. Starting in Cooperstown, New York at a beautiful mountain lake which resembles Lake Geneva in Switzerland, the Susquehanna heads south for ninety-six miles and then turns around at Great Bend and goes back fifteen miles north to Binghamton. After that, it goes west for forty miles to Sayre and then goes south again as it picks up other branches. Greatly enlarged, it reappears to Turnpike travelers at Wilkes Barre. Thousands of travelers have sped up the wide valley without noticing that the same river which flows south from Wilkes Barre apparently starts flowing north at Great Bend. The traveler's eye is deceived by the apparently continuous long valley which the highway follows. At Binghamton, the Susquehanna starts flowing west, but that too is overlooked in whizzing past the cloverleaves and traffic directions. The Great Bend itself is a lovely water gap with a couple of small towns on its shores, but is otherwise pretty deserted.

For two and a half years, Joseph Smith the founder of the Mormon religion spent full time five miles away from the Turnpike exit, at the real bend in the river (not the town of Great Bend) writing the 275,000 words of the Book of Mormon. Although Smith was a native of Palmyra, New York, and Mormonism is most easily viewed as an outgrowth of wide-spread religious uproar in upper New York State during the 1820s, it undoubtedly provoked malicious gossip from those who resist all claims of miracles, as well as staunch defense from those who believe. It's comparatively safe to say the prophet was living at the Great Bend in his wife's tiny home while she wrote down his dictated translation. The source of his vision was said to be John the Baptist, which others have since taken literally to varying degrees. Those who believe in the pregnancy of virgins and reappearances after a death must be tolerant of the sometimes overstated beliefs of others. Smith never let anyone see the golden plates from which the writings were derived, however, and ultimately it must rest that he was relating what he believed he had seen. His father-in-law described him as a charlatan, an attitude not completely rare among other fathers in law. His wife, caught between conflicting family loyalties, declined for years to join the religion that flowed from her own pen.

|

| The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints |

However, with the publication of the Book of Mormon, Smith rapidly gained adherents numbering in the thousands. He moved the center of the religion westward in several steps and was shot to death by a mob, variously styled as militia and vigilantes, in Illinois at the age of 38. Just who killed him and what the motives were are matters we normally leave to courts rather than newspaper accounts. There is little doubt that many other religions of the time were outraged by the tolerance of polygamy, and so the account that he was assassinated by offended husbands of those to whom he proposed marriage, must be somewhat discounted. All religious disputes have a tendency to get out of hand, and the frontier religions of that time were particularly feverish, flaring up in an environment of the rule of the six-gun.

|

| Joseph Smith House |

The attraction of this religion seems to an outsider to have been based on its forgiveness for sinners, offering them tolerant heaven rather than the vindictive hellfire and brimstone which more puritanical protestant sects at that time envisioned for even well-behaved converts. There is a certain echo in Smith's Mormonism of the tolerant Quaker view that "There is that of God, in everyone." Similarly, although it is difficult to accept his idea that the American Indian tribes might be descendants of a lost tribe of Israel from the 7th Century B.C., the Mormon, and Quaker, teaching of tolerance to the Indians was in keeping with changing racial views in the early 19th Century, and softens somewhat the former Mormon distrust of the black race; although that, too, must be seen in the context of the then-approaching Civil War.

The best-known feature of this religion used to be polygamy, however, which is difficult to defend with theological, demographic or even romantic reasonings. With a few exceptions among Mormon extremists, the religion has moved away from any defense of polygamy. As the center of Mormonism moved to Utah, Congress outlawed polygamy, and the church officially condemned the practice and gave it up. Since it is still not rare to encounter a kindly decent gentleman on the streets of Salt Lake City whose grandmother or great-grandmother had been a polygamous wife, the whole subject has come to be treated there as an ancient embarrassment, best left unmentioned, but never quite forgotten. As a matter of fact, all religions have so much to account for in their past that they are most fairly judged by the sort of behavior they seem to inspire in their followers. By that standard, the earnest, decent, hard-working Mormons of today have earned their right not to be sneered at.

|

| Great Bend PA |

As for the simple little memorial along the river, it may seem a disappointment to some. It has not been made into a tourist attraction or a place of pilgrimage. It may even be a little unprotected from vandalism. But is surely worth the small trouble to visit, adding only half an hour to anyone's trip. One does not have to accept either the history or the theology in order to wish to see the place, which is a sweet little neglected clearing with a railroad running between it and the river. As a backdrop, the great bend in the Susquehanna is a remarkable sight in itself, because the river seems to be running in the wrong direction while no one notices. But one final double-take about polygamy simply cannot be resisted. One of the members of the Right Angle Club spent many years in the Middle East as a diplomat, where every Muslim man is permitted to have four wives. He reports that the younger Muslim men will often have nothing whatever to do with polygamy. Having watched the scheming, conniving jealousies of that custom from a front-row seat, the sort of Arab who always wears western clothes has firmly decided from personal observation that one woman, or at least one woman at a time, is quite enough.

The newspapers tell us a Mormon tabernacle or church may soon be constructed near the new Barnes Museum on the Parkway in Philadelphia. It could even resemble the one in Washington DC, with a statue of the Angel Moroni, blowing a gleaming gold trumpet. The Mormons seem to want Philadelphia to notice them and form an opinion, which indeed we probably will.

Harvard Men Suggest a Cold Place for Yale

THE Colonial disputes with Great Britain were settled in 1783, creating great opportunities for the Colonies to resume their disputes with each other. Because of the unfortunate earlier action of the Penn Proprietors in selling land already occupied by Connecticut settlers, the legislatures of Connecticut and Pennsylvania behaved in ways that do them no credit. The situation could easily have led to more armed conflict, and it could even have gone from local war to fragmentation of the nation. So, although New York was close enough to know better, they joined with Massachusetts in offering to consider carving a new state out of Pennsylvania's northeast corner. The proposal was rejected, but the geological idea remains.

The northeast corner was once covered by glacier, and the region remains separated from the rest of Pennsylvania by a "terminal moraine", which is the huge pile of rocks and stones left behind after a glacier recedes. There are thirteen counties of rather desolate woods in this corner, with five or six more counties of moraine. Even today, some upper counties have only five or six thousand residents scattered in little settlements. The whole idea of creating a new state died when people got a chance to walk around and actually look at the region. Although one county is named Wyoming, this was not Wyoming, Fair Wyoming, at all; this was a pile of rocks. Moraines were what the Connecticut settlers were trying to escape.

However, their grandchildren might be unsure. Tremendous deposits of anthracite were soon discovered in the region, and then oil in Bradford County. Present residents of New York City will apparently commute endlessly to escape taxes, so an interstate highway or two would probably quickly make the area into Little Brooklyn.

The central point in all this was beginning to emerge. Since the Constitution was ratified, it simply no longer matters what state you were living in, as long as you can trust the legislature and the courts to be reasonably fair. These two combative legislatures and affiliated courts were once quite obviously behaving in a manner too obscenely partisan to be tolerated. Everybody involved in this mess could see the advantage offered by the ability to appeal to a superior power dominated by the other eleven (now, forty-nine) states. Carving out a separate state was not a compromise, at all. It was a threat, just as unsatisfactory to one combatant as the other.

Although it was clearly time to put aside the grievances and vengeances of a land dispute which had got out of hand, currents of other wild and headstrong ideas continued to swirl into the northeastern corner of Pennsylvania. In April 1786 Ethan Allen himself showed up in this region, wearing full Regimental uniform. He declared he had formed one new state and that with one hundred of his Green Mountain Boys and two hundred riflemen, he could establish another one. There is some reason to suppose Allen was responding to an action of the Susquehanna Company of Connecticut, which had held a meeting the previous September where Oliver Wolcott drafted a constitution for a new state named Westmoreland. William Judd was to be governor, John Franklin lieutenant governor and Ethan Allen was to be in command of the militia. The Assemblies of both Connecticut and Pennsylvania immediately reacted with outrage to renounce the whole State of Westmoreland idea; when John Franklin persisted, he was dragged to Philadelphia and thrown into jail to calm his rebellious spirit. Nevertheless, the point was dramatized that -- even five years after the Decision of Trenton had supposedly settled the matter, and after all sensible neighbors urgently wanted this dispute terminated -- something else needed to be done to strengthen the Articles of Confederation, or preferably replace them entirely.

Sayre / Athens

|

| General John Sullivan |

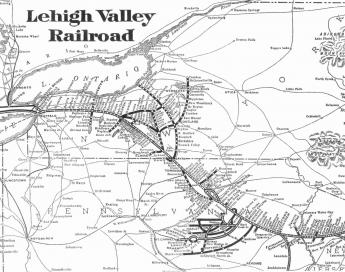

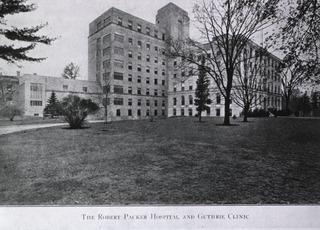

Running west from Oneonta and Binghamton, NY, the North branch of the Susquehanna runs due west for about fifty miles until it turns abruptly south at Sayre, PA. In the course of this westward run along the northernmost ridge of the Endless Mountains, it passes Apalachin NY, where the mobster chieftains got caught by the state police while holding a convention. At Sayre, named after an eastern railroad financier of the 19th Century, it joins the Chemung River at a large bowl-shaped refuge in the mountains which shelters it somewhat from the ferocious snows for which this part of Upper New York State is famous. Sayre usually gets a heavy snowfall or two in January, which lies on the ground until the Spring thaw in April. But that's pretty mild for this region, and the Iroquois made it a sort of headquarters, where Queen Esther of head-smashing fame made her home just before the Wyoming massacre in which she figured so prominently. Consequently, General Sullivan made his famous march to destroy the Iroquois by going northwestward up the Susquehanna to Athens, rather than following the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, as somehow seems more probable. Actually, Sayre was more of a 19th Century town, with the original settlement concentrated a few miles south at the region of Athens. Sayre is more modern, once was the location of a huge locomotive repair center, and has the Guthrie Medical Clinic at Robert Packer Hospital. Athens is older, quieter and has more stately charm, and is actually on the Chemung River with a two hundred yard portage to the Susquehanna.

|

| Lehigh Valley RR Fame |

Robert Packer was considered to be the ne'er do well son of Asa Packer, that go-getting industrialist of Mauch Chunk/Jim Thorpe, and Lehigh Valley RR fame. The father is said to have sent his son up to Sayre to get him out of the way, but once freed of the old tyrant's grip, Robert built things up into the second-largest locomotive repair center in the world. Robert Packer never had children and eventually set about building up the Robert Packer Hospital. Much taken with the Mayo Clinic model, he called Charlie Mayo and asked if had someone to suggest for running the local institution. Indeed, Mayo had just the fellow, Guthrie, who like the Mayos was a surgeon with a specialty in removing enlarged thyroid glands. As long as the railroads flourished, the Guthrie Clinic was headed toward the status of a major medical center with private rail cars for the surgeons and the like. However, the advent of diesel locomotives put an end to the main source of local prosperity, and the Guthrie Clinic settled down to a more modest status of a regional medical center, mainly in competition with the Geisinger Clinic further south on another bend in the Susquehanna. At present, the Obama Administration seems much taken with the model of the Midwestern group practice, of which both Guthrie and Geisinger are models. Perhaps the politicians do not realize that all of these clinics were based economically on the principle that surgeons can make enormous incomes if they are fed enough cases. Consequently, they are willing to reduce their own income in order to make group practice more attractive to the "feeders"; the department of surgery subsidizes the department of general medicine. Their competitors have long grumbled that this arrangement was an elaborate evasion of the medical ethical prohibition of fee-splitting. Most of that feeling has subsided, but a more serious present criticism is that the Obama Administration mainly seems determined to reduce surgical fees, so the whole arrangement may collapse when they do.

|

| Robert Packer Hospital |

Curiously, prosperity looks as though it may be ready to return to the Endless Mountains, in the form of the fracking method of gas extraction from the Marcellus Shale which underlies this region. Coming as it does at a time when domestic oil production is growing inadequate, but alternative energy sources are not yet competitive, rail freight is returning to the region, and truckers by the thousand are migrating from economically depressed regions like Detroit. For reasons not immediately clear, the huge trucks which import water and chemicals for fracking are driven by non-residents. The smaller trucks which carry away (to Northern New York, they say) the brine effluent from the wells, are driven by locally recruited truck drivers. A certain number of bar room fights have been rumored to have grown out of this situation. Camp followers of the fair sex have occasionally drifted into town, but so far not in large numbers.

As the region has evolved, the third town of Waverly NY has joined the other two in what amounts to a seamless conurbation of about 30,000 people, nestled in the cozy valley.

Star-Gazing in Cherry Valley

Somebody with a lot of imagination has taken the darkest, highest, a most remote place on the East coast -- and made it into a pleasant entertainment for the whole family. That unknown somebody apparently realized that streetlights and other signs of civilization make it almost impossible for most people to see the starlit heavens above them. The process has been named light pollution, which sort of crept up on most of us in the past fifty years. I can easily remember the days when you could walk out of your front door almost any night and see the Big Dipper and on clear nights the Milky Way. If you were a Boy Scout, you could earn merit badges for the number of constellations you could recognize. For thousands of years, everybody could share the night with the nomads of the Far East, but slowly light pollution made it go away. Maybe you can see the North star once in a while, but hardly ever see the same sky which mariners and camel drivers see. There's not much to do when you are a shepherd tending your flocks by night, so the nomads named stars for ancient myths, observed the difference between stars and "wandering stars", or planets. Nowadays that's a real experience for most city dwellers, impacting children with the novelty, and the old folks with a sudden recollection of How It Used To Be. You can go to a planetarium of course, but you have to go to Cherry Valley, Pennsylvania, for the real thing.

The site is an old abandoned country airport, situated on top of one of the highest local hills, located as far away from a town as possible. In this case, Coudersport. The perimeter is planted with trees, to add to the darkness of the horizon. The area is actually divided into two astronomy centers, one for the general drive-in public and the other restricted to overnight campers who pitch their tents and gather in the log-cabin sanctuary. A number of the tents of these pros and semi-pros are designed to be small planetariums or observatories; it's quite an unusual thing to see. Astronomers seem to know other astronomers, and guitars are soon produced to sing country music around the fireplaces. The fact is, of course, that if you aren't one of the repeaters you will be more welcome across the road in the public drive-in observation area.

The rangers and local volunteers start their programs at 7 PM, with more serious programs after 9:30 PM, when it gets seriously dark. Perhaps the idea was to have an early program for small children, but where a crowd gathers, there will be speakers, and the earlier program mostly features the use of telescopes of professional size, where you stand in line to see what is being talked about. When the sun goes down, however, everything stops for the enjoyment of the sky turning black, and the astonishing stars coming out of every corner, right down to the tops of the trees. Most spectacular and a little later than the brighter stars is our own galaxy, the Milky Way is seen on edge and stretching over the arch of the sky. It must be admitted that, at almost all times, at least two man-made stars are rapidly crossing the sky; they are either airplanes or satellites. That's something we didn't have in my childhood, but it adds to the interest. There are about a hundred wooden benches placed advantageously to form an outdoor amphitheater. There was a sudden spurt of crowd interest following an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer. If the crowds continue to grow, they will have to find more benches. A number of people brought their own lawn chairs, but at least so far that isn't needed.

As soon as the ranger starts talking, it becomes clear that another modern invention makes this outdoor planetarium possible. A speaker can hold a small flashlight and point a beam of laser light for several hundred feet. It doesn't reach to the stars of course, but it seems to and quite effectively allows the lecturer to point out individual stars and constellations as if it the pointer were touching them. The audience gets the idea immediately, and the effect is considerably more realistic than the artificial pointers of indoor planetaria. Now you can really get the idea of those constellations with Greek and Roman names. It turns out the American Indians had large star mythology, too, full of stories about bears chasing hunters and the like.

There are a couple of irreconcilable conflicts, here. It won't stay dark if a lot of light-polluting houses are built in the neighborhood, so the nearest gas station and the modern motel is about fifteen miles away. That's kind of tough on little kids who are well past bedtimes and even sort of a challenge for drivers doing night driving on winding country roads. The alternative is to camp out, preferably in the area designated for reg'lars. And don't forget the moon and weather. A new moon is best, full moon worst; rainstorms worst of all. There are a growing number of contests and gatherings of non-astronomical interest. In particular, there are annual lumberjack contests, cutting down big trees with hand axes, and the like. This was once a great lumbering region, and its traditions persist.

Stephen Foster, Susquehanna Schoolboy

|

| Stephen Foster |

Stephen Foster was born in Pittsburgh, spent much of his life there, and the University of Pittsburgh honors him with the most important collection of his letters and life history. It is, therefore, a surprise to encounter The Camptown racetrack near the upper Susquehanna River and to find that he was sent to boarding schools in Towanda and Athens by his Pittsburgh parents. This partly reflects the nature of pre-steel mill Pittsburgh, a transportation gateway for westward migrants in the early part of the 19th Century, for whom Athens and Towanda were cultural centers "back East". Whether this signifies some subsequent decline of the Central portion of Pennsylvania, or merely the relative growth of Pittsburgh, is a little less certain.

The Camptown Racetrack, five miles long, Do-Dah, Do-Dah is surely the place referred to in the song; its present obscurity is a surprise compared with its enduring fame in song. At the time Foster wrote it, Camptown probably was a bustling center on the frontier, seemingly more glamorous because of gambling and adventure of other sorts. Its fame endures because reality has by-passed it. By contrast, the Bowery where Foster died has declined to a noxious slum and the name summons up a different image.

Stephen Foster was an alcoholic, suffering in poverty all his later life and dragging his wife and child down with him. He struck his head and bled to death over a period of three weeks, in the Bowery. Since then, the simple little tunes he wrote have become a central part of the American myth, leading to the title of "America's first composer", or the "Father of American Music." The songs were in fact the product of considerable study and skill, with numerous revisions to achieve their apparent simplicity.

Since Pittsburgh continues to think of itself as a Union town, part of the emphasis in that environment is on the way he made a pitiful income from works which enriched sheet music publishers and performers, largely because of a lack of enforceable copyright protections, or even an organized methodology for monetizing a work of art. In a subsequent article, a happenstance encounter with the present leader of music monetization points a contrast between then and now.

(Notes: 1. His brother, Morrison Foster, is largely responsible for compiling his works and writing a short but pertinent biography of Stephen. His sister, Ann Eliza Foster Buchanan, married a brother of President James Buchanan. 2. Alexander Cassatt was born on December 8, 1839, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[3] His sister was the painter Mary Cassatt. He married Lois Buchanan, daughter of the Rev. Edward Y. Buchanan and Ann Eliza Foster. Lois Buchanan was a niece of James Buchanan, 15th President of the United States, and through her mother, a niece of songwriter Stephen Foster.[4] The couple had two sons and two daughters.)Wilkes-Barre, Site of the Wyoming Massacre

|

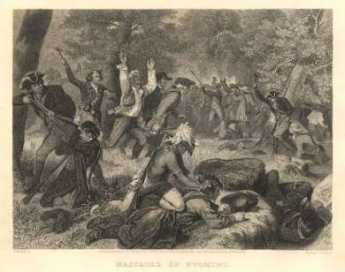

| Wyoming Massacre |

For eons of time, the site of Wilkes-Barre, PA was once a sort of finger-lake between two mountain ridges. As dammed-up rivers tend to do, this one gradually filled up with sludge until the water spilled over at Nanticoke, a few miles to the south. After the lake drained out leaving the original river in place, there was also left a flat and fertile valley on either side of it. Furthermore, the towering mountain ranges on either side protected the valley from the weather, so the Wyoming Valley became a verdant paradise in the middle of the mountains. Somehow, the Congregationalist settlers of Connecticut found out about it, dug up some old deeds from King Charles to the effect it belonged to Connecticut, and eventually set forth to resettle in this mountain valley. Pennsylvania took offense at this, and the result was three little wars which few people have heard of, called the Pennamite Wars. The local Indians were most offended of all and did the most massacring in a very thorough way. During the Third Pennamite War, George Washington was at Valley Forge with more urgent matters on his mind, and dispatched General Sullivan to "take care" of the Indian problem; Sullivan did so in a very thorough way, essentially destroying the Iroquois nation. The other eleven colonies were distraught to see Pennsylvania and Connecticut putting on a side-show, and part of the judicial settlement was to give Connecticut the "Western Reserve" in Ohio as compensation for restoring the peace. The American Constitution of 1787 essentially made state possession of land a moot point, and the Western Reserve is just a quaint term you hear in Cleveland. Wyoming is a term that most people associate with a Western State, although it is named for this valley, and Dallas is another term that has been largely transplanted from a small town near Wilkes-Barre to a big town in Texas. So, if you want to get the confusion of terms straight, about Wyoming, Dallas, Western Reserve, and Westmoreland, you will take a little time to learn about Wilkes-Barre. Westmoreland is the name of gentleman's club in Wilkes-Barre, but it is also the name of a county near Pittsburgh where Connecticut folks thought it would be useful to flee.

That's a lot of history for a little town, but there's more. Somehow, the joys and pleasures of living in the Wyoming Valley were carried back to people like Rousseau, who were looking for examples of the "noble savage", noble because he had not learned all of the evil things that French aristocrats invented, and therefore warranted effusive praise during the so-called Romantic Period, when France was being purified by the guillotine. The main drum-beater for this mania was a poet named Thomas Campbell, who composed a long poem in Spencerian rhyme called "Gertrude of Pennsylvania". Even those who find merit in Spencer will nowadays find it difficult to accept the notion of flamingos on Pennsylvania streams, or lying on the ocean beaches of Pennsylvania, reading Shakespeare. Even those who have less taste for Herbert Spenser will still find a reason to distrust the judgment of those who praise the beheading of, say, Lavoisier. The noble savages in this particular case were Iroquois, who exterminated 600 settlers by essentially torturing them to death.

|

| General John Sullivan |

There's a memorial in nearby Wyoming commemorating this massacre, which indeed is probably better left forgotten. There are plaques with the names of the fallen, and the names of the survivors. The idea of the Wyoming Valley as a paradise on earth was destroyed by another event. The ancient lake which once filled the Wyoming Valley was deeper and more ancient than anyone guessed. Underneath the rich topsoil was a vein of anthracite, and Wilkes-Barre became a boom town with strip mining, a fate no paradise can long withstand. There is nearby said to be a coal mine which caught fire underground and has been burning uncontrolled for several decades. Talk about pollution disasters; this one is a monster.

Reliable records of how the Connecticut Yankees got to the Wyoming Valley are hard to find. Offhand, it is puzzling to wonder how they got past New York or crossed the Hudson River. The best way to get between the two places today is probably pretty close to the route the colonists took, however, because travel in those days was much more constrained by geography. We know they started from Litchfield, CN, and in fact, for a while, Wilkes-Barre was part of the County of Litchfield. From Litchfield, they likely crossed the Hudson near Newburgh, went to the mountain gap at Port Jervis, and either came into the Wyoming Valley over the ridges or went a little north to the Susquehanna and came down from there. On a map at least, that's a relatively straight shot.

Boalsburg

|

| Boalsburg |

FIVE miles East of State College is Boalsburg, which is by far the most interesting place in Central Pennsylvania. First of all, the town itself is laid out around the most perfect surviving example of a Scotch-Irish diamond. The Scots in Northern Ireland were much resented by their Roman Catholic neighbors to the south of them, and gladly accepted James Logan's offer to come to William Penn's haven of religious freedom, in return for their settling near the Indians. This was Logan's solution to the problem of keeping the peace between the pacifist Quakers in Philadelphia, and the sensitivities of the Indians about settlers on their ancient lands. The Quakers wanted to avoid conflict with the Indians, wouldn't sell them either liquor or gunpowder, while Logan was under orders from Penn's descendants to sell the land. So, being Scotch-Irish himself, he felt confident his relatives would find ways of coping with the problem. Much of the turmoil of Pontiac's War and the French and Indian Wars, the marauding Paxtang Boys and King George's War, grew out of the resulting conflicts between the two notoriously combative groups. In any event, this decision explains why Scotch-Irish settled the frontier early, and surprisingly far west of the centers of Pennsylvania Dutch settlement. The Scotch Irish had a tradition of favoring the crossroads of two main highways. Their habit was to cut off the four corners of an intersection, leaving a diamond-shaped park in the middle. Traditionally, the enlarged intersection would have a flagpole in the middle.

|

| Boalsburg Diamond |

Naturally, the diamond was a good place to put a post office, a general store, or a tavern. A man named Boal put up an early tavern, and this diamond became Boalsburg. Boal is the name of a type of Madeira wine, which may have some relevance here, having to do with old stories of some Portuguese debts which were paid off in the land of Center County. In any event, there is a log cabin near the diamond, with a dozen Boal tombstones in front of it. Quite a large and elegant restaurant is now more directly on the square. This town is a photographer's dream and well worth anyone's drive around the main streets.

At some time, the Boal family moved out of the center of town to a mansion about half a mile away. From the looks of it, five or six additions were made to house family and servants, and it almost looks like five houses joined together. The carriage house has a couple of ancient carriages, one with and one without, leaf springs. The walls are hung with dozens of sabers and swords from many different wars, each with its story. There are muskets and rifles, dating back to the Revolutionary War.

The main house is modest for a mansion but immoderate for a farmhouse. It has definitely been lived in, and it's built for comfort. The walls are covered with trophies and mementos, with five signatures of US Presidents identifiable. Lots of Boals seem to have married lots of European nobility, perhaps in one of these rooms. One old rake is quoted as saying he inherited three fortunes -- and spent 'em all. Over and over again the theme emerges: the Boals was a military family, often raising their own regiments. Across the road in what seems sure to have once been Boal property, is the Military Museum, with real battleship cannons at the gate. Memorial Day was started here after the Civil War, and it is the headquarters of the local National Guard Division; it's by far the most popular tourist attraction in town.

|

| The Columbus Family Chapel |

But off in one corner of the side yard of the mansion is a little stone house, perhaps two stories high. It is a replica of the Columbus family chapel in Spain, copied stone for stone. The stories vary somewhat between guides, but apparently, two or more relatives were descended from Christopher Columbus, and while one Boal was Ambassador to Bolivia, he married a lady in waiting to the Queen who was also descended. Possibly the Spanish Civil War had something to do with it, but in any event, the personal belongings of the Columbus family were judged to be the property of the Boals, so they were moved here to the chapel replica. A decade or so ago, the chapel was broken into by thieves, and since that time security is considerably enhanced. Two pieces of wood are still shown as pieces of the True Cross of Jesus, with authentication going back to the 5th Century, and numerous handwritten journals are there. The Goya paintings and tapestries, and a solid gold crucifix are among the pieces which are now somewhere else. The matter is one of considerable embarrassment. Most of the many pieces which remain, are seeming of the nature of things which would be enormously valuable if you knew what they were, but just about worthless if you don't. In a sense, the best protection is the ignorance which surrounds them. The guide last month remembers one day when 27 visitors came to the Mansion and many days when no one came. As he spoke, you could see at least five hundred cars parked in the Military Museum across the road. There may have been five cars parked in the diamond in the center of Boalsburg. It's sort of a shame that this would be true, just as it makes you grit your teeth to imagine the indifference the whole place would receive if you moved it to Times Square. But, let's face it, the main protection for these invaluable pieces of history lies in that general lack of interest in them.

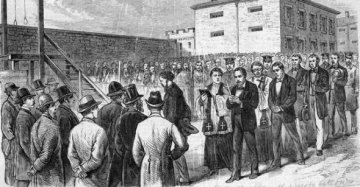

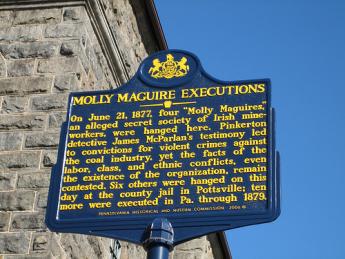

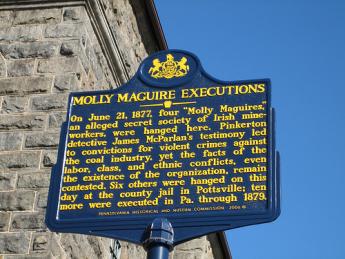

Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania (1)

|

|

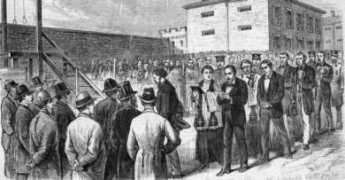

| Pottsville Hanging |

|

| Historical Marker |

However, resistance to conscription during the Civil War gave newcomer clannishness more serious consequences. This was particularly true when it inserted a surprising pro-slavery (or at least anti-emancipation) protest into the very center of the Northern Union, around Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Whatever the South was fighting for, the North was primarily fighting to preserve the economic benefits of greater trade in larger markets -- a concept loosely described as "preserving the union". A second twist to anti-Mollie repression was later added after the war was over, when the 19th Century Industrial Revolution created another untamable tribe, the Robber Barons, for whom uncooperative behavior was a tendency not to be trifled with.

Basic behavior of the Molly Maguires in action followed a simple pattern. Males dressed as females in blackface made extortion threats against members of the dominant society, protesting that their own subsequent violence was merely justice for heartlessness toward widows and orphans. Since the Mollies out of costume mingled cheerfully with those they secretly called oppressors, for actual assassinations they either called in the help of distant outsiders or drew lots to choose the assassin locally. The community would then unite to provide a vocal alibi and profess to be offended by the accusation. To increase intimidation, death threats were pinned to the door.

Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania (2)

|

| the Mollie threat in the coal regions |

IT was in their interest for both the Molly Maguires and their chief enemies to exaggerate the Mollie threat in the coal regions. Mollies hoped to achieve more pay for less work by intimidating employers, the more intimidation the better. The management of the mines and railroads more shrewdly hoped to mobilize public sympathy to their side, in the newspapers, courts, and legislature, by exaggerating the undoubtedly real menace of lawless, unpatriotic behavior. There have since been great strides in the art of slanted propaganda, and it takes more finesse to mobilize modern opinion. Having watched Hitler and Stalin in action, and noticing our political parties going in the same direction, we would now regard the behavior of 1870 to be crude, and therefore less effective. But there was one very public rebuttal to what the Mollies were claiming. Although they portrayed themselves as oppressed Irish in an English dominated world, their main enemy was himself a well known Irishman.

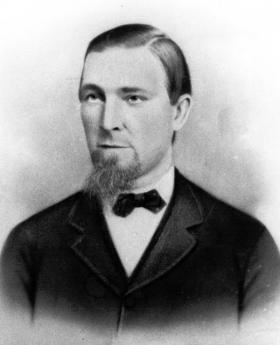

|

| Franklin Benjamin Gowen |

Franklin Benjamin Gowen, President of the Reading Railroad from 1870-1886, was both Irish and definitely larger than life. As one illustration of his extraordinary energy, he died at the age of 53 but had risen from moderate circumstances to control what would become the largest railroad in America by age 34, ultimately being forced from office by J.P. Morgan while still only 50. By some measures, in those sixteen years, he had made the Reading into the largest corporation in the world, even though he had comparatively little interest in and no training in railroading. Although born in Mt. Airy, he apprenticed himself to a lawyer in Pottsville, and at age 26 became District Attorney in the coal region during the first outbursts of Molly Maguire violence. Although he had never gone to law school, he seemed to love the courtroom and continued to work as an independent trial lawyer all during the time he was president of the railroad. One commentator remarked that to read his speeches in cold type was still enough to jeopardize one's judgment. During his later battles for corporate dominance, he twice filled the Academy of Music with stockholders, holding them spellbound for three-hour speeches. On this evidence alone, one. supposes he had a lifelong tendency to stretch facts.

|

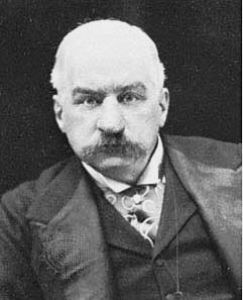

| J.P. Morgan |