6 Volumes

Philadelphia Medicine

Several hundred essays on the history and peculiarities of Medicine in Philadelphia, where most of it started.

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Health Reform: A Century of Health Care Reform

Although Bismarck started a national health plan, American attempts to reform healthcare began with the Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive era. Obamacare is just the latest episode.

Health Reform: Children Playing With Matches

Health Reform: Changing the Insurance Model

At 18% of GDP, health care is too big to be revised in one step. We advise collecting interest on the revenue, using modified Health Savings Accounts. After that, the obvious next steps would trigger as much reform as we could handle in a decade.

Clinton Health Plan of 1993 - Part Two

Fifteen years after the Clinton Plan, public dissatisfaction with the health financing system is no better, probably worse.

What Good Did Medicare Do?

|

| Amy Finklestein |

An article in the Wall Street Journal Amy Finkelstein of MIT describes evidence that Medicare seemingly produced no provable increase in longevity during the period she studied, which was 1965 to 1975. Thinking back to that time in the practice of Medicine, the conclusion while surprising seems entirely plausible after a little reflection. Our system of charity care was good enough so I really doubt if very many people were allowed to die prematurely because of poverty in 1965, at least in Philadelphia. Charity took care of them. Elective repairs were an entirely different matter, however. Working in charity clinics at the time, I well remember that almost every patient seemed to have bad teeth, an unrepaired hernia, untreated varicose veins, or a positive Wasserman and similar threatening but non-fatal conditions. There existed a vast backlog of untreated non-fatal conditions, almost to the point where it seemed we would never catch up, but of course, we did eventually catch up. Whatever the costs of the government health programs during that decade, they mainly reflect that huge backlog project of correcting health impairments which were nevertheless not an immediate threat to life, in addition to lifting the former financial burden from our charity institutions of treating conditions which were undeniably life-threatening.

From this historical experience it can be deduced that any new proposals for modifying or reforming the medical system should start with the medical situation as we happen to find it. If a great many people are dying of treatable conditions as they are in Asia and Africa today, then it is likely that extra finance will promptly reflect itself as improved population longevity. If that's not the case and other institutions are providing emergency care, you must then look among the backlogs of untreated conditions -- in that locality -- for a justification of new costs and disruption. Since even the non-urgent backlog in America has now been almost totally eliminated, something else must be proposed as a goal for legitimate improvement. Otherwise, you would have to be so far-sighted that you make a decision to spend an extra 10% or so of the Gross Domestic Product for benefits, every year for ten years until some unpredictable long-term benefits appear. It's difficult to imagine our political process launching forth on such an adventure.

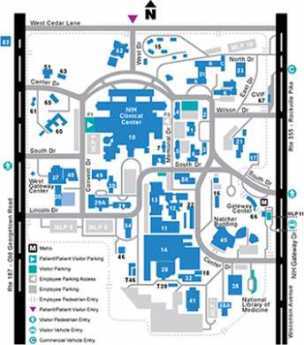

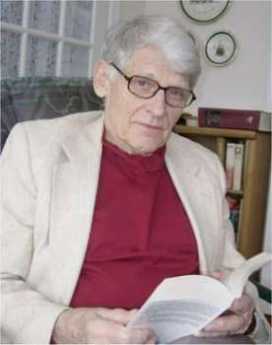

|

| NIH Map |

However, let's continue to look at what did happen, to see what arguments we might have been imaginative enough to adopt. First of all, we can see that the quality of life of the elderly generation, the one I now belong to, has been enormously enhanced by joint replacement and cataract repair --significantly reducing wheelchair crippling and blindness. Neither of these benefactions can be said to result from a brilliant insight by a genius, but rather a slow, incremental process of adding small enhancements until the desirable result becomes standard practice. This sort of development, as in research and development, is very likely a response to a general increase in the funding of the provider community, as contrasted with targetted extra appropriations to the NIH for example. A plausible case can be made for asserting that the undesignated increased funding of the early Medicare program gave tens of thousands of elderly people -- in the next generation -- a comfortable life rather than a miserable one, several decades sooner than a more frugal medical system would have done.

Secondly, life expectancy did finally increase substantially, perhaps extending an average of ten or more years of life in the period subsequent to the enactment of the Medicare Act. But it did so only after a fifteen or twenty-year lag. It's uncertain how much we may credit Medicare with this benefit, however; the increased basic research funding of the National Institutes of Health seems plausibly responsible. However, at least half of the longevity benefit must be credited to research efforts in the private pharmaceutical industry, which was funded in large measure by Medicare dollars, recirculated through drug purchases. But there's restrained exuberance about even these miracles, which were surely the greatest medical advances in human history.

We have greatly extended the comfortable, useful life of our population, but now must grudgingly admit we directed these benefits to a group of people who are no longer engaged in economic activity. Unemployable people have been transformed into employable ones, but sadly we have mainly given a twenty-year vacation to people who are capable of doing productive work, but don't. Instead, we import millions of foreigners to do the work or outsource it, which accomplishes much the same result without the demographic disruptions. Worse still, we may find these people will often outlive their savings, so the extra longevity could result in years of economic misery and despair, not necessarily an improvement on the physical and medical varieties. In other words, if we had possessed the foresight to see that ultimately improved longevity and life quality was a worthwhile goal, we should then have simultaneously taken the steps to improve economic circumstances which make that medical miracle seem worthwhile.

As we now consider further steps to over fund medical care, or reform it, or make it universal or whatever, perhaps there will be time to consider whether other improvements in American life are needed before there is a net beneficial effect. Either undertaken simultaneously with the health care financing initiatives or even possibly, instead of them.

Unequal Health in an Unequal World

|

| Sir Michael Marmont |

In 2007, the Sonia Isard Lecture was delivered at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia by Professor Sir Michael Marmot on the topic of Health in an Unequal World . Sir Michael is the Director of the International Institute for Science and Health, and MRC Research Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health, at University College, London.

His starting point is the commonly accepted view that the richer you are, the better your health. The life expectancy of the poorest level of society is almost everywhere seen to be shorter than the local average. In less developed countries and in children, the excess mortality is concentrated in infectious diseases. However, in more affluent nations, it is obesity, diabetes, hypertension which seems to account for it. Regardless of the cause, the common denominator everywhere is poverty, which leads to a general opinion that the alleviation of poverty contains the solution to the health gradient. There is even another logical presumption, that improved health care will directly remedy the problem, without necessarily addressing a more daunting obstacle, the elimination of poverty. Although the provision of equal access to quality health care may be almost more than we can accomplish, in this analysis of causes, it is a short-cut.

Sir Michael is not so sure. Great Britain has had a national health service for fifty years, but it is still clear to British physicians that the class distinction persists in health if not in health care. Mortality statistics confirm the professional opinion. The conclusion is general that the British health system must be flawed, or underfunded, or poorly run. Not necessarily correct, not necessarily correct. Buried in a mountain of data from the Whitehall Studies of British civil servants, Dr. Marmot teased out the fact that a striking inverse gradient of mortality and morbidity existed in a highly educated group that had essentially equal health care and, while not rich were certainly not poor. The gradient persisted at all levels; the higher you rose in the bureaucracy, the longer you were destined to live after retirement.

Evidently a huge amount of statistical work followed this insight, confirming its thesis in a wide variety of situations. The caste system in India provided a confirming example that was unrelated to education or occupational strivings. Marmot's observation is a gradual gradient, not a two-part, either/or. Not rich versus poor, but richer versus less-rich, less-rich versus even-less rich. Every occupational, social or financial step up makes you live a little longer.

I wish he had stopped there. But the pressure to explain has generated the hypothesis that what we are looking at maybe progressive degrees of empowerment. Others who have contemplated Professor Marmot's observations suggest it is due to progressive degrees of happiness. Sorry, but that's a little too touchy-feely for me. I don't know what empowerment is, or how to measure happiness. The monk in his cell may have achieved serenity, not necessarily happiness, certainly not empowerment. The prisoner in his cell has no serenity, happiness or empowerment. I prefer to believe it is premature to speculate publicly about the mechanisms which produce these observations.

Meanwhile, it seems to be true that if you aspire to be rich you may not become happy, but you will probably live longer. If you want to rise in the hierarchy and still live longer, you need not be afraid to strive. For at least a little while longer, that's going to have to suffice as a definition of wisdom.

Healthcare Reform: Looking Ahead (1)

|

| baby boomers |

By this point, a patient reader of these reminiscences has probably learned quite enough about the Clinton Health Plan and its immediate aftermath. There is, of course, more to say, but except for political junkies, the topic doesn't warrant protracted dissection. It might be worth knowing the motivations of the insurance industry when they launched that bombardment of "Harry and Louise" television advertisements. Opinion within the insurance industry must certainly have been divided, however, and the main decision makers are probably all now retired. The Harry/Louise ad campaign is often given credit for the political assassination of the Clinton Plan, but that seems unlikely. The decisions about medical care were made without heeding the opinions of providers of medical care, so it would not be surprising to learn that decisions about insurance were made without completely candid discussion with insurance professionals.

In fact, grieving too much for the past may have led to looking too little at the future, which clearly contains a whole new set of facts. When the largest generation in history, the baby boomers, start to retire in 2012, those boomers own children will then be at peak earning power but will be a very small generation, too small to support their more numerous parents. Consequently, the 12.5% tax the current teenagers pay for retirement benefits will be too small to pay for their parents' health costs. It will be uncomfortable to increase that 12.5% by much. Thus, the Ponzi scheme we have run for eighty years will then be unable to conceal its facts with talk of trust funds and lock boxes. For nearly a century, Congress has spent the Social Security and Medicare tax surplus for non-medical purposes. They will have to stop doing that in less than ten years. Consequently, we can confidently expect the boomers to protest loudly: they contributed 12.5% of income during their whole working lives to support medical care, and now learn that nothing was saved for their own health care. Even more exasperating is that the second Bush administration did attempt to introduce legislation in 2006 to set aside some current surplus to reduce the impact of the coming crunch -- and Bush was howled down. It would thus appear to be the nature of current politics that this boomer health cost shortfall will not be seriously addressed until the crisis is actually upon us. Democrats will apparently stonewall the matter to avoid blame for designing and ballyhooing a welfare expedient of the 1930s that was swept under the rug during decades of affluence. Republicans will be determined not to be paymasters for a welfare scheme they had opposed from the beginning. So what will happen?

Government only has two options in funding programs where the money has already been spent; they can raise taxes or they can borrow money. By raising taxes, they risk precipitating an economic depression. By borrowing, they flirt with hyper-inflation of the sort that destroyed Germany and Austria in the 1920s. By adopting a little of both remedies, we wander into "stagflation", a term invented in the 1970s to describe a very unpleasant episode. Whatever the description, there seems a very strong likelihood of economic pain and political uproar. It sounds pretty unlikely the public will be in a mood for expensive additions to health insurance coverage.

All this is a preamble to impending cuts in the health budget. We must anticipate the only approach government ever uses for program reduction, the only arrow in the government quiver. It goes like this: first you cut a program budget by, say, ten percent and watch to see if anything bad happens. If nothing bad happens, cut it again. If something bad does happen during a series of cuts, deny that it did happen, and scramble around to patch up the damage. If possible governments restore some of the cuts when they go too far, but in Medicare whose unfunded deficit is in the trillions of dollars, that may not be possible. Try to get re-elected after you pull off one of these capers, and you begin to sense how dictators get into office. It really isn't comfortable to talk apocalypse this way, and one would certainly hope there is some flaw in the prediction. There could be other unexpected events in the meantime, deus ex machina, but a stock market crash, a thermonuclear war, or violent changes in the environmental temperature are all going to weaken the world economy, not make things better. This doomsday scenario seems almost certain to include some serious cost-cutting in the health financing system. Therefore, it is only common sense to examine what advance changes might be made in the health delivery system to minimize the damage to it.

My proposal amounts to suggesting that we put the doctors in charge of the cost-cutting. In accident rooms, battlefield medical stations, and even television war serials, the person in charge of sorting out the influx of unexpected casualties is said to be in triage. In triage there is one basic rule: put your best man in triage. If the security guard, the admissions clerk, or the night watchman directs the emergency down the wrong corridor, the ensuing blunders will cascade as the system struggles to get things back on track. We can expect objections to what I have to propose which will take the form of warnings about letting foxes watch the henhouse, but in general, the public already supposes the non-physicians will step aside for the doctors in an emergency. So the more open the discussion about command and control, the better, with ultimate faith that the public will support the common-sense approach of putting your best-trained person in charge.

For present purposes, the general proposal is that when drastic cuts in budget get imposed, it should be the physicians of the local community, not the administrators or the insurance executives or the local business leaders -- who should make the painful choices between what is essential and what can be sacrificed. This is most readily achieved by setting aside the Maricopa decision and clarifying the HMO enabling acts to the effect that it is not an antitrust violation for physicians professionally practicing in nominal competition to participate in the shared governance of health maintenance organizations. In other words, that HMOs such as the Maricopa Foundation need not fear antitrust action, using the experience of a dozen other Foundations for Medical Care as proof of the harmlessness of the approach. It should not be necessary for these organizations to prove positive value, only to demonstrate lack of harmfulness. If they can be established and allowed to compete with insurance-dominated or employer-dominated HMOs, their worth can be established by success in the marketplace. Ultimately, the choice of governance form will thus be made by the patients, and the proposal should be a popular one.

It should also be popular with hospital administrators. They chafed at physician control thirty years ago, but that was before they encountered the far more brutal price negotiations of HMOs dominated by business and insurance. The consequent costly and disruptive wave of hospital mergers is defended by very few, although it would be interesting to examine dispassionate analysis. Probably no one adequately appreciated the threat that employer domination of these practice groups represented to hospital administrations. When hospitals confronted employer groups in serious hard price negotiations, hospitals came to the shocking realization that these people actually had the power to move large groups of people to a competitive hospital, and they certainly talked as though they were capable of doing it. The resulting panic of hospital mergers, consolidation into chains, and the emergence of for-profit competition by hospitals that had no thought of a charitable mission, has created a degree of cost and disorder that was not in the original plan. Hospitals in rural California who told their colleagues of the burdensome power of their staff doctors under doctor-run Foundations would now have to admit that a return to that environment would be a distinct relief.

And there might even be a reconsideration by business leaders. What physicians would bring to the table, what is now new and different, is the undeniable experience that dominating captive HMOs has not proved as useful to employers as they hoped it would be. The cost savings have been disappointing, the exploitation by insurance intermediaries, and the undeniable employee restlessness was not exactly anticipated. Running employee health projects is a large distracting time waster for C.E.O.s who have other goals and mandates to pursue. If employers keep a focus on their reason for involvement in employee health, hardly any of them could defend a posture of resisting the emergence of new choices which make a reasonable claim to reducing employee contentiousness, at a competitively lower cost.

And the government? Among the various unpleasant alternatives that Congress must consider, is the possibility to be discussed next that employers may want to pull out of employee health care entirely. Allowing competitive forms of ownership of existing arrangements might not seem too risky a step, compared with that prospect.

Flexner Report, Revisited

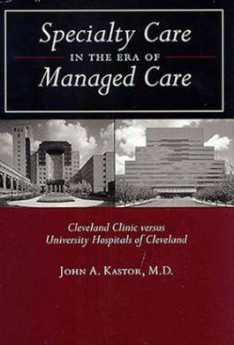

|

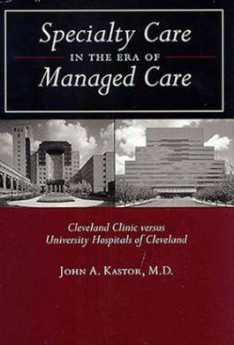

| Specialty Care In The Era Of Managed Care |

Book Review

Specialty Care In The Era Of Managed Care

Cleveland Clinic

versus

University Hospitals of Cleveland

John A. Kastor, M.D.

0-8018-8174-9

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Abraham Flexner's 1910 Report practically canonized the notion that medical schools must be owned by universities. Forty years later, Dwight Eisenhower firmly disagreed. Asked why ever would he give up the pleasant life of Columbia University president to get into the nastiness of national politics, he replied, "The White House doesn't run a medical school." During the same era, Secretary of State Dean Acheson and Senator Robert Taft, political enemies but personal friends, were riding to New Haven together to a Yale trustee meeting. The two agreed it was unfair for 40% of university budget to be spent on 1% of the student body, and decided Yale should get rid of its medical school. Their subsequent motion failed by only one vote at the meeting. And as a final Flexner footnote, Princeton University which shrewdly never owned a medical school, is now nonetheless in the news over the central underlying discordance -- managing huge sums which, either by contract or donor restriction, are inflexibly assigned to a single department, thus substituting the donor's priorities for those of the University president. Medical school ownership of teaching hospitals raises the same issue except in reverse. It is politically impossible to treat an affiliate as a cash cow without learning the harsh reality of the Golden Rule: the affiliate with the gold will promptly remake the rules.

Understanding these issues but seldom emphasizing them, John A. Kastor has done us all a great favor by studying and publishing the unseemly disorders which result, in many cities and institutions. His particular focus in this book is on Cleveland, where all that matters medically is the prospering Cleveland Clinic and its struggling rival, Case Western Reserve. The book is mainly focused on a particular question: under managed care, should teaching hospitals adopt the Cleveland Clinic's style and organization, in order to prosper as they do? In the end, he cannot quite bring himself to recommend it. Essentially, the Clinic is run by doctors, for doctors. The clinic pays salaries, but (so far) bills fee-for-service. The over-reimbursed procedural specialties such as surgery subsidize the under-reimbursed cognitive specialties (prompting East Coast colleagues to sneer at "organized fee-splitting".) Cleveland's Clinic, like all group practices, must devise strategies to a)induce acquiescence to the subsidy of internists by surgeons, b)discourage physicians from starting competitive practices in the neighborhood or c)turning their salaried incentive into an instant 40-hour week. Not everyone will submit to what is between the lines, most notably at the Clinic's Florida satellite. But since the alternative is to hire non-physicians with concealed animosities to doctors to run hospitals and medical schools, all physicians who actually treat patients must give the physician-run group practice model some thought based on experience with its alternative.

We all have an unfortunate tendency to assume that weakness of character is the main cause of the executive misbehavior so widely observable in all corporate environments. In the medical world, a much more powerful force is generated by shifting quirks of reimbursement. Once the pecking order is established between hospital and school, medical school and university, it gets violently upended by the underdog suddenly getting riches from the Senate Finance Committee, then upended again by Ways and Means a few years later. Or bureaucrats in Rockville, in Baltimore, or the Executive Office Building. Eisenhower was wrong, the White House does run medical schools and hospitals when they would very likely be better run by physicians. In fact, Flexner's offhand interposition of the University into this dogfight seems a little quaint. Just to mention the indirect residency reimbursement program, the institutional research overhead allowance, the old cost-plus reimbursement of hospitals, the institutional patent revisions, is to start a list which can get to be quite long. In most of these cases, an institutional component which needed to be subsidized in the past has now become prosperous and is asked to return the subsidy. The chief executive is then caught between duty to his institution, the threat of investigation if funds shifting is suspected, and his own sense of fairness. That these upheavals are so frequently pacified without serious harm to the patients, is a credit too seldom given.

Dr. Kastor's writing is somewhat hampered by a need to footnote, document and defend everything he says. Nevertheless, the book will be read by physicians like a novel with a great many villains. It's encouraged reading. One hopes that the next book in the Kastor series will examine the Florida satellite clinics of the Cleveland Clinic and of the Mayo Clinic, one making money and the other losing money. Maybe some basic issues of an effective medical organization can be resolved by making different comparisons.

But don't expect permanent axioms to emerge; Medicare Risk contracts are coming. Under capitated systems, administrative incentives are slanted to discourage expense, especially expensive surgical procedures. Perhaps group practices will soon face a need to have their internists subsidize their surgeons, reversing the traditional arrangement. The threat to collegiality, so evident in this book, is destined to continue.

Healthcare Reform: Looking Ahead (2)

|

| health care |

The Industrial Revolution crowded people together into smoky, draughty unhealthy places to live and work, and thus created ideal conditions for the spread of smallpox, tuberculosis, plague, poliomyelitis and many other infectious diseases. With better sanitation and hygiene, those diseases declined steadily for two centuries. Meanwhile, medical science developed a steady stream of expensive enhancements to health like removing an inflamed appendix, inserting pins into broken bones, utilizing CAT scans and artificial kidneys. These things each made life more comfortable and extended it a little longer, but steadily increased the cost of care. Here and there major leaps forward occurred, like the discovery of antibiotics and the prevention of arteriosclerosis, but it seldom seemed that medical care was stamping out disease, it was just making it more complicated and expensive. But if you stopping plodding forward for a moment and looked backward, the aggregate progress was astounding. Dozens of diseases either disappeared entirely or are well on the way to disappearing, like polio, smallpox, tuberculosis, syphilis, rheumatic fever, and what have you. Life expectancy for Americans at birth, which had been 47 years in 1900, was approaching 80 years in 2000. When I started as an attending physician in 1955, I was in charge of a 40-bed ward continuously full of diabetic amputees; during the last fifteen years of my practice, however, I did not attend a single diabetic amputation. At some point in this amazing medical pilgrimage I can remember realizing that for really important purposes, there were only two diseases left. Arteriosclerosis and cancer; and now arteriosclerosis mortality has declined fifty percent in ten years.

So now it is possible to have the luxury of asking: what will happen when we finally cure cancer? Oh sure, there is Alzheimers Disease, HIV/AIDS, schizophrenia and childbirth, plus an apparently endless variety of ways to produce self-inflicted conditions. Everyone will eventually die of something, so doctors will keep busy. It is not necessary to predict the end of medical care to see that some important social transformations are likely. For example, if we cure cancer around the time of financial chaos caused by the retirement of baby boomers, it is going to be hard to resist the demand that we reduce spending on medical research. Every tedious word of the impending debate on the topic could be written right now to save time because it is a very strong probability that spending on medical research will decline, once an effective cure for cancer is behind us.

Let's, however, continue our march into the future of healthcare reform. When employers became self-insured for employee health costs, they came into possession of data about what they were buying. It didn't look adequate to them to explain the sums of money they were spending, so they concluded they were being hoodwinked by hospital cost shifting, with consequences summed up as the Clinton Health Plan. Now put yourself in their shoes when the Wall Street Journal tells you cancer has been conquered. Michael De Bakey once pressured Lyndon Johnson to start a crusade against Heart Disease, Stroke, and Cancer, and now even cancer is gone. A significant number of C.E.O.s are likely at that point to decide that since Far Eastern competitors don't have this cost to contend with, perhaps it is time to declare that you have been fleeced long enough. Give the employees some money, and tell them to buy their own health insurance.

There are even some more legitimate arguments for doing so. Individually owned and selected health insurance would be portable, putting an end to "job lock", the fear of changing jobs for fear of losing health coverage in the process. Employee divorces create a different twist to job lock, and inequities jump out at you from the tangle of arguments about dual coverage for working couples. Add same-sex marriages to this issue and employers are driven to despair. Individual policies would simplify all of these issues, and open the door to life-long coverages, which we will discuss in a later section.

If medical progress makes just the right progress in the impending time interval before doomsday, it is even possible to start talking about eliminating health insurance in a practical way. If there is no threat of medical expense, why buy insurance against it? Since everybody will die of something, it is hard to envision a time without insurance. But maybe Medicare is enough. Senator Edward Kennedy (D, Massachusetts) will finally have his universal single-payer system -- by default.

What we have here are the daydreams of a corporate C.E.O., struggling to make his numbers for the next quarter, and they are pretty strong stuff. But who can doubt the power of these concepts to move the system away from an employer-based formulation?

The American Health Non-system

|

| Dr. Jock Murray |

Dr. Jock Murray has recently been Chairman of the American College of Physicians. He is also a Canadian. Recently, he was invited to address the College of Physicians of Philadelphia on an evaluation of the lessons to be learned from comparing the health systems of the two neighboring nations. It was an excellent, fair, and well-balanced address. The man who introduced him referred jokingly to the American non-system and Dr. Murray emphasized two epigrams about national systems in general. No nation on earth can afford to fill all of the health demands of all its people. So, all nations confront the three main demands, to deliver everything, to deliver it to everyone, and to do so immediately (ie without waiting lists). Fulfilling any two of these three demands is possible, but to deliver all three is impossible. Comparison of health systems in various countries amounts to identifying which two of the three they have chosen to have, which one they choose to surrender. I hope and believe Dr. Murray would mostly agree to this caricature of his remarks.

As a member of his audience, it does seem to be fair to acknowledge we have a non-system, and probably even fair to go further and observe we fundamentally resist those irksome constraints implicit in having a planned system. No organized system, and proud of it. But we do have something else. Let's call it a vision.

Without formally stating it, or even widely acknowledging it, Americans seem to have embraced a dream that we can indeed have everything for everybody right away. Yes, we can. The method available is to gamble that research can eliminate the disease. We hope, although we know it is not certain, that cancer, schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease will reduce the cost of care. Our model exists in Rheumatic Fever and poliomyelitis, for which there are essentially no remaining treatment costs. We know that everyone ultimately dies of something; we assume we are already paying everybody's terminal costs. Eliminating diseases postpones terminal costs, but surely does not add to them.

We have knowingly and recklessly embarked on a program of pouring huge amounts of money into medical research. I believe the public mostly suspects that much of our present high cost of health insurance eventually finds its way into supporting research, and the public mostly acquiesces in whatever cost-shifting is involved. The people who devote their lives to research in turn vaguely recognize that we might reach a point where the country cannot afford this gamble any longer, and they could have half-wasted a career. We all vaguely understand it's a gamble; major elimination of disease might not be just over the horizon and might lead us on to indefinite postponement of a foolish dream.

But those are the chances you take; we seem resolved to take them. We are going to give it a go. If we can, we are going to spend whatever it takes to give everything to everybody, right away. We are going to eliminate diseases, on the unproven but plausible assumption that doing so will eventually bring costs down.

Healthcare Reform: Looking Ahead (3)

|

For fifty years, turmoil in the health insurance industry has originated in the steel and auto industries. It seems strange that no heroes have come to general public attention, although there may be heroes who are known to insiders; somebody may yet write a book about it. This may be of only passing importance, but the present distress in the American Big Three automakers suggests that unexpected legislative proposals concerning health financing could emerge from that direction. The turmoil in Detroit once centered on the auto industry enjoying windfall profits which labor wanted to share. More recent discord comes from the opposite direction: the automakers now cannot afford to honor those contracts they signed with labor having to do with health benefits.

The contract for the United Auto Workers was certainly generous. Printed up in a little red book for wide distribution, the contract states emphatically that an employee for six months or more will be completely covered for medical expenses for the rest of his life. If Medicare pays some of the cost, that is fine, but if Medicare reduces its benefits, the employer is liable. Some features of this contract may have been changed since it was printed, but it is difficult to imagine what incentives the UAW would have to agree to modifications. Except, of course, the self-interest which emerges when it looks as though the employer might go out of business unless there is some form of relief from wage costs.

To judge what is going to come of this is to judge the likelihood of the various arguments, predictions, and recriminations that are so common in heated disputes. Two things are pretty clear to auto industry outsiders: the UAW contract provides more generous health benefits than almost any other employee group enjoys, while the auto industry has worse earnings than many or most other industries. Consequently, both the employees and the stockholders have an incentive to make adjustments in the auto industry, a situation shared by the steel industry and other major auto suppliers. The form this has seemed to take is to favor some form of national health insurance, in which the taxpayers would take over the obligations of the auto manufacturers. So, look out for proposals from Senators and Congressmen from Michigan, and watch which nominees for U.S. President are favored by the rust-belt political delegations.

Workers in other industries are not certain to go along with such proposals. After all, most people resent it when someone else makes out better than everyone else for decades, and then comes asking for a hand-out.

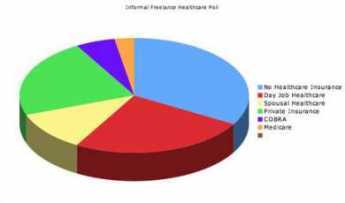

Segmented Health Insurance

|

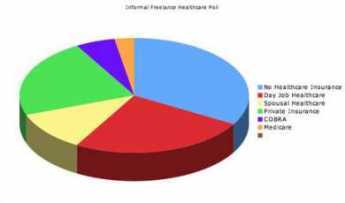

| Pie Graph |

Everybody knows the old insurance saw, that the big print gives but the small print takes away. If health insurance pays for one sort of thing but not another, there is anxiety that a bewildered patient can be deprived of coverage he thinks he paid for. A patient knows he was sick, that he saw a doctor, or that he went to a hospital; beyond that, it's better not to leave room for arguments. To a certain degree, this is what has made HMOs seem so threatening; complicated assurances can lead to disappointing loopholes. So, for a century it has almost been an article of religious faith that health insurance should cover everything that costs money when you are sick. However, that headlong faith is exactly why the matter needs to be subject to critical review. Not only does monolithic insurance conceal a vast system of cross-subsidies. It has existed for too long when everything else in Medicine has changed for the original premise to be immune to change.

There are health insurance considerations which go beyond mere convenience of administration. Transparency and flexibility, for instance, suffer when everything is under a single blanket. Women pay a share of prostate surgeries they will never have themselves, people who hate abortions have to pay a share of them anyway. The ability to buy what you think you need is taken away, so some people who could afford what they need are unable to afford the whole package because it includes what they feel they would never need. And then there is moral hazard. Some people reach for what they don't need just because it costs nothing extra. Well, this isn't 1930; we don't need to debate the whole issue top to bottom. But there may nevertheless be a few features of global health insurance which could be advantageously teased out separately.

For a first example, look at terminal care. Everybody is going to die, and mostly the cost is picked up by Medicare because most people who die are elderly. Some insight into the issue and a reasonably workable definition of terminal care is provided by the statistic that a third of the expenditures of Medicare is paid for someone in the last year of life. Statistics on the average age at death are known with great precision, so it would be easy to calculate the yearly premium cost at any age or the size of a single-premium policy needed at any age to cover the average cost of the last-year-of-life. If we are ever to fund the unfunded Medicare program, this is the place to start. And if you are wondering how you know in advance when you are going to die, you don't need to know. Just establish an independent "endowment" fund, which reimburses the current Medicare program for any expense incurred during what proves in retrospect to have been the last year. Presumably, the cost of running the unfunded portion of Medicare would then drop by a third, while the cost of the funded third would be diminished by the investment strategy of its manager. The relatively few people who die without Medicare eligibility might be treated in the same way, reimbursing whoever paid the costs, but the risk calculation would be more difficult, and a life insurance policy might be preferable. Once the younger individual with such a designated life insurance policy attained Medicare eligibility, some sort of coordination would be desirable.

Everyone dies once, and no one escapes death. But terminal care benefits are not so terribly different from some other health issues. Nowadays, just about everybody can expect to have two cataract operations, and most people can expect a hernia repair, a gallbladder removal, and if male a prostate removal. Everybody ought to have a pneumonia immunization, and a colonoscopy, by age 66. It would be easy to compile lifetime risks and update them yearly, for the typical male with 1 death, 1 pneumonia vaccination, one colonoscopy, 0.76 prostatectomies, 0.59 cholecystectomies, 0.37 hernia repairs and so on. The cost of this sort of routine care is not really insurance, it is pre-payment. It is not subject to abuse, and need not be challenged or reviewed unless statistical monitoring shows that the incidence of some component was rising in a particular zip code area. In that case, what would be called for would not claim review, it would be provider review.

Perhaps the reader can see where this is going. Having stripped out routine pre-payment as much as is practical, you are left with the unknowable "all other". Insurance which covers this sort of risk becomes true insurance, in an umbrella form. As medical care continues to advance, more things can be moved from "all other" to "routine". Ultimately, and probably sooner than most people would guess, you can achieve a true insurance system, defined as having a trivial insurance premium for a remote risk. From that point forward, you can direct your cost-cutting attention to reducing the cost of routine care. That would include the devising of strategies to pay for luxury versions of routine care, as desired.

David F. Bradford, 1939-2005

|

| David Bradford |

We should take the word of his friend and colleague, Daniel Schaviro, that the core of David Bradford's professional career as an economist was his conviction that a very deep wrong existed when two people could earn exactly the same income over their lifetimes but the one who spent every cent immediately would pay less in taxes than the other who carefully saved for his retirement and heirs. Bradford was offended by this message our society was broadcasting.

Working for a time in the U.S. Treasury Department and later as a member of the President's Council of Economic Advisor's, he was able to explore the mechanical workings of tax law well enough to translate moral conviction into a workable proposal for political reform. In 1977 he published "Blueprints for Tax Reform", introducing these practical ideas at the highest level of academic rigor. The impact of his ideas in this paper extended through three presidencies, particularly the present one.

Bradford saw the tax injustice which penalized the Protestant ethic could be corrected in two ways. Either the tax code could shelter individual savings from taxes until they are spent (the IRA), or else convert the income tax into a consumption tax (like VAT). In either case, taxation would take place at the same time as consumption, rather than at the time of earning. Notice the person who saves money to spend later will suffer from both inflation and taxes on taxes on the inflation "gains". The political choice between the two proposed solutions was made by Senator William Roth (R, DE) who sponsored the Individual Retirement Account (IRA) and shepherded it through an intensely political Congress. His was a wise decision, since its voluntary nature made it attractive to politicians, while the French experience with a mandatory Value Added Tax (VAT) created political opportunities to favor certain industries, which politicians were quick to understand.

After twenty-five initially slow years, the eventual popularity of the IRA has now encouraged its extension to Social Security. That's what agitates domestic policy debate at the time of David Bradford's unfortunate death. The IRA model is also the basic concept underlying Health Savings Accounts (HRA), which struggled for many years but have reached their own period of growing acceptance. The Blueprints idea has thus dominated domestic politics for nearly three decades, while its originator remained largely unknown. Far from being a sign of weakness of the idea, it is a proof of the revolutionary nature of this simple concept that it initially provokes public resistance, but also inspires relentless tenacity among those who have taken up its challenge.

David Bradford returned to Princeton from his Washington experience, resting for decades at the quiet center of an Economics department that is not known for its quietude. After a most unfortunate fire at his home, he died of the burns in nearby Philadelphia, which hardly knew him.

The Hospital That Ate Chicago (1)

|

| George Ross Fisher M.D III |

One evening in 1979 my visiting son, puzzled by health financing, asked me to explain. A decade of asking myself the same question led to the prompt reply that there seemed to be two central problems, both of them man-made. It's axiomatic in our family that man-made problems can have man-made solutions.

I believed you adequately understood health care financing if you understood the price reduction which hospitals give to subscribers of Blue Cross but not to subscribers of their competitors, and if you also understood the income tax dodge which the Federal government gives to salaried, but not to self-employed people who buy health insurance.

He asked how in the world these two subsidies were defended, and I told him. He then asked how these monopoly-inducing subsidies related to other weird quirks of health finance, and I told him that, too. He listened quietly for thirty minutes, and then exclaimed, "Wow. That's really the Hospital that Ate Chicago!"

So he went to bed, while I stayed up and wrote a short fancy for the New England Journal of Medicine, called, "The Hospital That Ate Chicago". Next morning I polished it a little and sent it off to the editor. Within a few days, it was accepted. Six weeks later it was in print.

Further Acknowledgments (2)

|

| Knocking on the door |

There were some flurries of interest in the article, letters to the editor, passing comments from colleagues in the corridors of my hospitals, and even a challenge, readily squelched, from a hospital administrator who wrote in that it wasn't true. Perhaps the most flattering response was to meet the magazine's editor for the first time at a cocktail party twenty years later and have him exclaim a little about the stir it made.

Then, on July 3, there was a knock on my office door. Howard Sandum, the new publisher of Saunders Press, two blocks away, had read the article, proposed we have lunch. The substance of his visit was that, if I could write a book between the Fourth of July and Labor Day, he would publish it. I wasn't sure I was capable of writing a book in 90 days, had planned a vacation at the Jersey shore with my family, didn't know what to do. But I also didn't know that Howard was planning on moving in on us at the shore, and as fast as manuscript appeared, it was edited, at all hours, night and day. The marathon effort was greatly assisted by using my new computer, a Radio Shack TSR-80, with a processor speed of 2 GHz. Howard could type a hundred words a minute, but when I predicted that in a few years every book would be written with a computer, even he uneasily granted that maybe I had some kind of the point. My present computer is approximately a thousand times as fast on the processor level, although not noticeably faster on the author level. Today, a publisher won't even look at a manuscript unless it is on a computer disc.

My next hero was Thomas Donlon, at that time Washington correspondent for Barron's, now Editor-in-Chief of the Editorial Page. Donlon didn't remember me at first when I sat next to him lately at a luncheon, but in 1969 he did me the honor of writing a two-page book review, including the mind-exploding remark that I was a Renaissance Man. There is absolutely nothing in the whole world I would rather be called than A Renaissance Man, however inaccurate that description may be.

Well, a book can go through doors that the author wouldn't be allowed to go through. A week or so after Barron's book review, I was sitting quietly in my easy chair, deciding whether to shave and get dressed, when the phone rang. A voice said, "This is the White House calling."

IRA ... Individual Retirement Accounts (3)

|

| TSR-80100 |

It wasn't Ronald Reagan on the phone, it was John McClaughry, Senior Policy Adviser. I'm not sure how important you are when you are a Senior Policy Adviser, but it rates you an office in the Executive Office Building that has fireplaces and sofas, conference tables, and -- off in one corner-- a desk. I knew at a glance that we were going to be friends, because his desk had a Radio Shack TRS-80 computer on it, too. Seeing that, emboldened me to stuff my temporary White House identification badge in my pocket, because a guy with a computer in 1980 was certainly a member of the brotherhood, and would get me out of trouble if the guards caught me taking souvenirs. I still have the badge.

John was and is a master networker; maybe that's the job description of a senior policy adviser, I wouldn't know. He knew everybody who had anything to do with health financing, in all the branches of government, including one I hadn't known about, the neighborhood Think Tanks. Everybody is forever passing out business cards to new acquaintances and sweeping them into the left-hand breast pocket in one continuous motion. In Japan, everybody passes out cards but makes a big bowing ceremony of receiving them; what then happens to them in Japan I don't know, but in Washington, they go into Rolodexes and everybody invites everybody to some gathering or other. One evening, I was the entertainment at such a gathering, and have usefully kept up with quite a few people who attended. It's a different atmosphere from some other functions, particularly in the State Department with the other party, where everyone pretends to be meeting you for the very first time when they really aren't.

A few days after our first meeting, John wrote me a short note. Senator Roth of Delaware was pushing something called IRA, or Individual Savings Accounts. Did I think the idea could be applied to health care financing? I suddenly felt as though someone had shoved a stick into my skull and was stirring it around. Of course, just perfect! Add that to a high-deductible or so-called catastrophic health care policy, and out would emerge individually owned health insurance policies, with the same tax shelter as Blue Cross gets, and the added kicker of earning compound interest while you are well, in anticipation of high costs when you are older. It gets rid of pay-as-you-go, it puts an end to "job-lock" and all sorts of other bad things. Perfect.

Because of the difference in our previous backgrounds, I was in a little better position than John was to see how many medical pieces would fall in place if you made this simple provision, which after all was only giving to self-employed people what salaried people had been getting for decades. Yes, it had a small cost, but no more than the amount self-employed people (like doctors) were being cheated out of. We were only asking for a level playing field.

John and I had our project, the Medical Savings Account, and although we kept in touch, we went our separate ways to sell it. John's field was the Republican Party, and mine was the medical profession. It might take a year or two, but the arguments were unassailable.

Health Savings Accounts

The legislation removes the hampering restrictions of the 1995 Law. What follows is a brief outline of the main features of the HSA/MSA clause in the 2003 law,

|

| U.S. Capital |

as published by the main authorizing committee, the House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means. From this point forward, more specifics of the program will probably be written by the Executive Branch and published in the Federal Register. The Ways and Means Committee will continue to exercise oversight authority, however, in conjunction with the Senate Finance Committee. As a consequence, statutory modifications of the program are likely to appear in future annual budget reconciliation acts, or else in any new Medicare amendments. The legislative route map becomes more understandable when it is recalled that Medicare itself is considered to be an amendment (Title XVIII) of the Social Security Act.

Committee on Ways and Means

Medicare Prescription Drugs, Improvement And Modernization Act of 2003

Health Savings Accounts (HSA's)

Lifetime savings for Health Care

Working under the age of 65 can accumulate tax-free savings for lifetime health can needs if they have qualified health plans.

A qualified health plan has a minimum deductible of $1,000 with $5,000 cap on out-of-pocket expenses for self-only policies. These amounts are doubled for family policies.

Preventive care services are not subject to the deductible.

Individuals can make pre-tax contributions of up to 100% of the health plan deductibles. The maximum annual contributions are $2,600 for individuals with self-only policies and $5,150 for families (indexed annually for inflation).

Pre-tax contributions can be made by individuals, their employers, and family members.

Individuals age 55-65 can make additional pre-tax "catch up" contributions of up to $1,000 annually (phased in).

Tax-free distributions are allowed for health care needs covered by the insurance policy. Tax-free distributions can also be made for the continuation coverage required by Federal law (i.e., COBRA), health insurance for the unemployed, and long-term care insurance.

The individual owns the account. The savings follow the individual from job to job and into retirement.

HSA savings can be drawn down to pay for retiree health care once an individuals reach Medicare eligibility age.

Catch-up contributions during peak savings years allow individuals to build a nest egg to pay for retiree health needs. Catch-up contributions allow a married couple to save an additional $2,000 annually (once fully phased in if both spouses are at least 55.

Tax-free distributions can be used to pay for retiree health insurance (with no minimum deductible requirements), Medicare expenses, prescriptions drugs, and long-term care services, among other retiree health care expenses.

Upon death, HSA ownership may be transferred to the spouse on a tax-free basis.

Contain rising medical costs- HSA's will encourage individuals to buy health plans that better suit their needs so that insurance kicks in only when it is truly needed. Moreover, individuals will make cost-conscious decisions if they are spending their own money rather than someone else's.

Tax-free asset accumulation- Contributions are pre-tax, earnings are tax-free, and distributions are tax-free if used to pay for qualified, medical expenses.

Portability- Assets belong to the individual; they can be carried from job to job and into retirement.

Benefits for Medicare beneficiaries- HSA's can be used during retirement to pay for retiree health care, Medicare expenses, and prescription drugs. HSA's will provide the most benefits to seniors who are unlikely to have employer-provided health care during retirement. During their peak saving years, individuals can make pre-tax catch-up contributions.

Chairman Bill Thomas Committee on Ways and Means 11/19/2003 12:56 PM

Immigration and Universal Health Insurance

Among the many articles about the economic wonder of Dubai,

|

| Immigrants |

along the Persian Gulf, is the comment that only 20% of Dubai's residents are citizens of that country. The other 80% seem to be immigrant workers, flocking there to make $2 an hour because at home they can only make $1. America only has 12 million illegal immigrants at the moment, but comparing our problems with such extreme cases sharpens the discussion.

No matter what position you take on the question of universal American health care or universal anything else for that matter, you eventually have to re-examine your beliefs about our national borders. It is plainly absurd to propose that America should provide health care for the whole world, but if we allow essentially unlimited immigration it comes close to the same thing if you provide health care for everyone who is here.

The reason Dubai is a useful example is that we, too, are working our way into the fix of basing our prosperity on immigration we cannot handle. In recently seeking bids for a new roof, the choices I received were from Costa Ricans, Poles, and Puerto Ricans. True, one American citizen did inquire, but he was merely a contractor for some others, who were almost surely illegal migrant workers. Following the advice of a friend, I chose the Costa Ricans because they were rather small in size; my friend said they were less likely to get hurt falling off the roof. Although the situation in Dubai is more advanced, we seem to share the same difficulty that our economy would become pretty unworkable without immigrant labor. That problem for us does introduce an element of fairness into providing health care for people we really do depend on, or you could adopt the line that issues of practicality urge us to find a solution. Either way, you confront a dilemma, a problem offering two solutions or possibilities, of which neither is acceptable. Perhaps at least we could invent a new term, a multi lemma, defined as a problem with lots of solutions, none of which would work.

Making Money (8): Virtual Money

When money was tangible you had to guard it, now that it's mostly virtual you have to verify it. Hardly anybody can, and that's a problem.

|

When money and wealth were wampums, precious metals, and paper currency, these physical objects required physical protection. It was all a big nuisance, with six-guns on the belt, bank vaults, and appraisers of one sort or another. But now that wealth is merely a bookkeeping entry on someone's computer, things may be even more nuisance because verification is almost beyond us. Counterfeiting of the computer variety must be left to institutions to detect or deflect, causing them to introduce firewalls of various sorts that also block legitimate inspection by customers. "Trust but verify" doesn't work so well in this environment. Let's use a personal example, slightly fictionalized to protect the innocent.

Several software products now exist to download transaction information automatically from various institutional sources to a customer's home computer; they are either free or cost a nominal amount, and are quite "user-friendly". In my case, however, the reports they generated were quite significantly at variance from the monthly reports which were issued directly by my counterparties. Dear Sirs, Please explain.

What I soon discovered was that everyone blamed someone else, and everyone blamed me for bothering them. Quite obviously, I had little understanding of these specialized accounting niceties, and quite obviously I had too much spare time on my hands. Telephone help desks, often located in India, will not give out telephone numbers for incoming calls and are programmed to check the size of your account before placing you in a call-back queue. The first call is usually taken by a trainee whose job it is to screen out the silliest sort of help request, and then to refer to a supervisor if things rise in complexity. Supervisors have supervisors. That's if you are lucky. More commonly, the tedious software business has been farmed out to a vendor, and the contracting agency has neither the necessary understanding of the issue nor any ability to fix it. From the sound of it, the vendor often gives the contracting agency the same sort of isolation treatment that they would give a customer if he could find their telephone number. And guess what. At the end of the day, one of those high-handed defensive linemen -- turns out to have been at fault.

Let's explain one problem. On the surface, we were talking about a $40,000 difference in account balances; one may have been correct, but a second one must have been wrong. That rises to lawsuit level, so the matter got intensive study. It turns out the stockbroker had misinterpreted instructions for a "sweep-account" system. When a stock in your portfolio pays a dividend, the amount of the dividend is subtracted from that stock's line item and added to the line item of your money-market fund. That's fine, but there is one exception. When the money market fund itself pays a dividend, subtracting that dividend cancels out the addition, and the dividend essentially disappears from your net worth. Was this intentional? Certainly not; no one could stay in business doing that. It's not even a highly stupid error, since you can easily see yourself making the same oversight of the one implicit exception to the rule of sweep accounting. Because of this "bug" in the program involved one institution making a mistake and transmitting it to a second institution, the systematic error did not unbalance any books, until it reached mine. But since I did not detect the error for five months, there must be dozens, hundreds, maybe thousands of customers who did not detect it. Ouch. Do the math yourself to judge whether this was a serious error.

This illustration, only one of several on my personal report, leads to at least two larger principles. The first is that the transformation of money from tangible to virtual has occurred so rapidly that bullet-proof safeguards have not had time to emerge. After a century of use, most people cannot balance their checkbooks, but enough people can balance them so that systematic errors are not likely to slip past. When enough people with home computers repeatedly test the internal complexities of their virtual money accounts, confidence will develop that the system is probably working. Confidence is an important matter; it is possible to imagine quite a bank panic if the public suddenly got the idea that virtual money is maybe a mere vapor. In fact, the securitized credit panic of 2007 is a little like that. With a few new regulations and a lot of computer programming it surely will be possible to know who owns how many bum mortgages. That innovative mortgage system got ahead of its tracking verification, and we now just have to hope nothing serious happens before that gets fixed.

The second important lesson is that our health insurance system has a similar problem of far greater size and complexity. We are here talking about at least ten percent of Gross Domestic Product, in which one daily unit of measurement is in truckloads of insurance claims forms. Stocks and bonds are admittedly complicated but compared with thousands of different diagnoses, drugs, procedures, and hospitals -- verifying financial transactions is trivial compared with measuring medical ones. With a twenty billion dollar budget and ten years of lead time, we might have a shot at it. Except for the fact that during the ten-year interval, medical care will have changed so much, you will have to start over on the project.

Cost Shifting: Indigent Care Out, Outpatient Revenue, In

The CEO of Safeway Stores recently offered his company's preventive approaches as an example of what the nation can do to reduce health costs. He's undoubtedly sincere, but quite wrong; Safeway just shifted costs to Medicare. This is only one of several ways, major ways, cost-shifting is misleading us. Let's explain.

Average life expectancy is increasing at more than two years per decade, but of course, people eventually die. Since health care costs are heaviest in the last year or two of life, extending life will soon push nearly all those heavy terminal costs from employer-based insurance -- into Medicare. To die at age 64 costs Blue Cross a lot; but to die at 65 gets Medicare to pay for it. Either way, the cost is exactly the same, it doesn't save Society as a whole any money at all. Let's put it another way: dying at age 64 costs the employer and the employees, but dying at 65 costs the taxpayers. This means Medicare costs will surely rise, but in this case, it's a reason to rejoice.

Increasing longevity is constantly pushing more costs from employers to Medicare, and not just in Safeway; the prospect is that soon substantially all major sickness costs will shift into Medicare. (To explain the failure of most employer insurance premiums to fall comparably in response to this shift, one must look elsewhere). But just a minute. Medicare is 50% subsidized by the government, and the employer writes off half of the cost as a business expense. That ought to mean it doesn't make much difference to anyone involved, except for one thing. Some employers have two employees and some have two hundred thousand employees. The amount of tax write-off is multiplied by the number of employees, so some employers can only write off a little, while an occasional employer might even make a profit on using health insurance for calisthenics. Economists agree that fringe benefits eventually and proportionately come out of the pay packet, so ultimately the employed patient benefits from the reduced bill, his employer pays less, and the Medicare costs the taxpayers more.

<But instead of going down that trail, let's look at the second form of cost-shifting. Government payers and a few other monopolists are able to pay hospitals less than actual costs and get away with it. The worst offenders are state governors administering Medicaid, where the underpayment is roughly 30%, in spite of federal reimbursement to the states for most of it, at full price. The resulting profit is used for various state purposes, mainly nursing home reimbursement. For the most part, such diverted funds are used for purposes not easily eliminated, so it is unlikely there will be much cost reduction for the government if the scam is acknowledged and merely shifted to a different line in the ledger. To avoid bankruptcy, hospitals raise the rates for other health insurance plans -- and the uninsured. Employers are paying for most of it, so they stand to gain from reform, only to face higher state taxes as matters readjust. We have yet to learn where these costs will shift if the federal government takes over the costs of the uninsured; the current Obamacare plan is to shift 15 million uninsured persons to Medicaid. To a major degree, the federal government and its taxpayers are already paying for a lot of this uninsured cost, through the Medicaid shift. So its present dilemma is whether to continue to pay for it twice.

There's still a third cost-shift. In 1983, Medicare stopped reimbursing hospitals fee-for-service (itemized inpatient bills are still prepared but are meaningless fictions) and for thirty years has paid by the diagnosis, not the service, for inpatients. Consequently, per beneficiary inpatient costs have only risen 18% in five years, while outpatient costs have risen 47%. Costs are not the same as prices, which are even worse distorted. To a large extent, changes in costs are really changes in accounting practices, driving changes in actual practices. Skilled nursing and home care costs are rising even faster. When you hear fee-for-service payments attacked, it is this apparent overpayment of outpatient costs which is the source of the complaint. But to pay out-patient medical costs in any way other than fee-for-service would imply an almost unimaginable restructuring of the medical system, without any proof it would save money. It will be very interesting to learn what contorted proposal is about to emerge.

Medicare +6% Medicaid -30% Private Insured +32%

|

| 58% of Hospitals Lose Money |

Not only do these shifts provoke inpatient nursing shortages, but they also start a war for patients between hospitals and office-based physicians. Hospitals are winning this war for business, but are losing money doing so. If the public ever demands a stop to loss-leaders, net insurance premiums will probably rise. The difference between a hospital which makes money and one which loses money is based on whether there is enough extra out-patient revenue to compensate for the hidden tax which the state effectively imposes on hospitals in order to pay for nursing homes. The obscurity of the present payment system is quite expensive, and the present beneficiaries of it are the Medicaid nursing homes. Obamacare essentially provides health insurance to 15 million uninsureds by the process of placing them on Medicaid, so the consequences are going to be an interesting juggling act to watch.

5-year Change: Inpatient +18% Outpatient +47%

|

| 5-Year Hospital Costs |

Just notice, for example, that neither Medicare nor private health insurance pays below costs if you look at total national balances. Private insurers are paying hospitals 32% more than actual inpatient costs, while Medicare is paying 6% more than national cost. And yet 58% of hospitals are losing money. The magic in this formula lies in the losses incurred by state Medicaid but shifted to other payers. It could fairly be said we are just looking at a maldistribution of the uninsured, as a cost, and a maldistribution of non-inpatient revenues, as a profit, among the nation's hospitals. To what extent such maldistribution reflects uneven patient quality, as the loser hospitals claim, or provider inefficiency, as the winner hospitals would say, -- merely starts a distraction of attention which could last twenty years while we examine it.

And disruptions enough to take decades to fix.

Rejecting Preventive Health Care for Good Reason

WHILE we debated in 2010 whether to disregard what could be afforded, and provide sickness care to all, the idea subtly changed to providing "health care" for all. That is, the proposal was not merely to expand sickness care to everyone, it included an indefinite expansion of what everyone would get, and who would provide it. Medical care is provided by physicians, sickness care is provided by doctors, nurses, and hospitals, and healthcare is provided by a much larger undefined group of "providers". No wonder it costs more, and therefore a surprising number of people are unsure they do want all of it. It's almost a certainty that most people do not want to lose control of this definition, at least if it is to apply to them, personally. The issue centers on "healthcare" versus sickness care". How's that, again?

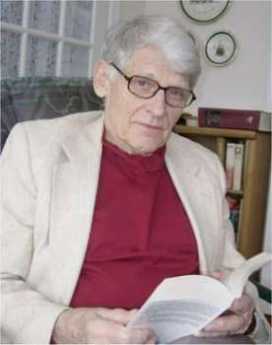

Preventive Health Care poses unique issues for seniors.

|

| Dr. Fisher |

For example, the notion that preventing disease is superior to treating disease, goes back at least to Benjamin Franklin. Arguing that the Pennsylvania Legislature ought to help build the nation's first hospital, Franklin offered the truism that it saves money in the long run to treat people early and get them back to work. Franklin could hardly have foreseen that it isn't always true. Preventive medicine implies it is cheaper to spend small amounts, possibly every year, for many people, than to spend large amounts for a few. It's a matter of arithmetic, of course, and doesn't always have the same answer. When the math works against a preventive approach, it's usually argued the gain in health is worth it; but that's not invariably the case, either. Once a person ceases to be an infant, the equation rebalances. And as an individual approaches end of life, his renunciation of what it takes to prolong life gathers more respect. It's a conflicted opinion, of course. Older people are outraged by any suggestion their lives do not deserve to be prolonged, but still, outspokenly prefer to die rather than wear a colostomy bag, or a respirator, or be fed with a spoon. If they are Jehovah's Witnesses and refuse transfusions, that too, commands more respect when they are elderly. This is a familiar problem, not a new one. What's new is more subtle and pervasive.

The public probably does not fully appreciate the disappearance of what might be called capricious diseases, caused by the operation of chance, or God's will. These are fatal illnesses like heart attacks, strokes, epidemics, and other things not anyone's fault. Except for cancer and Alzheimer's Disease, most really common serious illnesses which remain, are to some extent self-inflicted. Smoking causes lung cancer, alcoholism causes accidents and homicides as well as cirrhosis of the liver, taking recreational drugs damages lives, unprotected sex causes HIV. Obesity causes hypertension and diabetes, neglecting your medicine undermines treatment. If this keeps up, we are going to see the day when every obituary will seem too shameful to print. Poor Jud is dead; it's his own fault.

It's maybe even worse than that.The 2000-page Obama care plan was too complicated for even the Congressional committees to understand. But the public was not hostile for technical reasons, the public was irked at the idea. All the President's celebration of saving money through mandatory preventive care provoked the public to tell him, Get off my back. Almost every smoker has tried at least once to quit, absolutely every obese person has repeatedly tried to lose weight unsuccessfully. It's hard, let's see you try it. And now it goes beyond nagging, we are going to take the position that every person with a self-inflicted disease is costing the nation money we can't afford. The country has a right to punish people who drive us to bankruptcy. Let's have some Wellness police, and fair but firm punishments. Is that really what Obama has in mind? Well, sir, you just get off my back.

Even so compliant and dutiful a person as my late wife declared that when she got to be seventy, she was going to try marijuana. The fact that she actually lived thirteen years longer without doing it, did not change her basic attitude. When you get to a certain age, many of the old rules don't apply to you, doggone it.

Time To Care

|

| Dr. Norman Makous |

It sometimes seems as though Medicare has been a standard part of the scene for so long it now needs major reform, but when a doctor has practiced Medicine for sixty years he has seen a lot of contrasts between the old way and the new way, not all of them favorable to the new -- which we are now tired of, and trying to repair. That's particularly true if the doctor practiced at America's first and oldest hospital, because it sustained many traditions from two centuries before, and was among the last to yield to the imperatives of newcomers for the last forty years, their hands grasping for the purse strings. Dr. Norman Makous must either have a remarkable memory or a thick, detailed diary. He tells three hundred pages of fast-reading anecdotes about sixty years of his own medical practice, before summing up in fifty pages of reflection. One by one, he describes the innovations in his field of cardiology and how they affected him and his patients. Thiomerin, one of the first of many easy ways to pump out excess body fluid accumulation, transformed the treatment of congestive heart failure. Synthetic digitalis claimed to but probably did not much improve things over dried digitalis leaves; it certainly raised the cost. Cardiac catheterization, electro-shock resuscitation, ultra sound diagnostics, MRI and CAT scans, cardiac surgery using the heart-lung machine, and finally cardiac transplants -- all started out as headline-news spectaculars, evolved into cutting-edge advances, and then settled down into the Standard of Care that you obtained a plaintiff lawyer to sue about. All in one medical lifetime, supposedly prepared for by one Medical School course, followed by one residency apprenticeship, the specialty of Cardiology was completely transformed at least six times.

Meanwhile, the leadership of the medical profession was tenaciously resisted by those who supposedly followed its direction. Hospital administration.

Only Three Things Wrong With American Healthcare

|

| American Healthcare |

Although Congress is offering several thousand pages of proposals for healthcare "reform", none of them even mentions the three main difficulties, to say nothing of fixing them. Let's be terse about this:

1. Health insurance is fine, but if you make it universal, there is no impartial way to determine fair prices. Somebody must haggle with the vendor in order to introduce the issue of what is the service worth? The customer doesn't care what it costs to make, or whether the vendors are being paid fairly. If everyone is insured, no one cares what it costs. Not only do all costs rise, but they rise without coordination, without a sense of what each component is worth, relative to alternatives.

2. Employer-based insurance is fine, but it ends when employment ends. You just can't stretch employment-based insurance because you can't stretch employment.

3. State Medicaid programs are fine, but just about all fifty states are going broke trying to pay for it. Extending it to more people by raising the income limits just makes things worse. Items 2. and 3. are related. Trying to do both -- expand Medicaid as employment shrinks -- during a recession is incomprehensible. Item 1. (price confusion) gets drawn into this because the States try to pay less than it costs, hoping to shift the deficiency through hospital cost-shifting, utterly confounding the information which prices provide. The doctors have no way to tell which is the cheapest approach to a problem, so they don't try. Without control over prices, we can only control volume.

That's really all there is to this mess. Not one word of the current legislation even mentions these problems, so of course the legislation blunders. Even a child can see that compulsory expansion of benefits to universal coverage will fail if you can't pay for what you already have. No one will make sacrifices for a new system if the sacrifices seem futile. They are futile, so leave me alone.

The current administration has been compared with bank robbers who see they are trapped and decide to shoot their way out. Let's see them try to shoot their way past the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November.

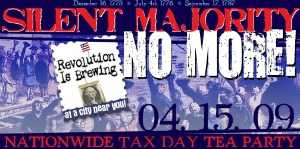

Adrift With The Living Constitution

.jpg)

|

| Senator Joe Sestak |

Former Congressman Joe Sestak visited the Franklin Inn Club recently, describing his experiences with the Tea Party movement. Since Senator Patrick Toomey, the man who defeated him in the 2010 election, is mostly a Libertarian, and Senator Arlen Specter who also lost has switched parties twice, all three candidates in the Pennsylvania senatorial election displayed major independence from party dominance, although in different ways. Ordinarily, gerrymandering and political machine politics result in a great many "safe" seats, where a representative or a Senator has more to fear from rivals in his own party than from his opposition in the other party; this year, things seem to be changing in our area. Pennsylvania is somehow in the vanguard of a major national shift in party politics, although it is unclear whether a third party is about to emerge, or whether the nature of the two party system is about to change in some other way.