1 Volumes

Favorite Reflections

In no particular order, here are the author's own favorites.

In no particular order, here are the author's own favorites.

Sanctuaria Mariposa

When they leave us, all the shad go to the Bay of Fundy. When Monarch butterflies leave us, they head for a thousand-acre spot in the mountains of Mexico, every single one. The butterfly performance is more remarkable since a butterfly can't make it from Philadelphia to Mexico City in one lifetime. The caterpillar that hatches in Pennsylvania knows where to go and somehow tells his grandchildren how to get there. Coming back North is somewhat easier; successive generations of butterflies follow the scent of milkweed plants, which is all they will eat.

This remarkable information was provided to us by the lifetime efforts of Professor Fred Urquhart of Toronto, with the volunteer help of the Girl Scouts. They tagged the insects, and other Girl Scouts reported back to headquarters whenever they found a tag or a tagged butterfly computer did the rest, and you better remember to thank them when they next offer to sell you some cookies.

|

| Mexico |

Your reporter found this information irresistible, and while on a trip to Mexico hired a car and driver to go look for the Sanctuary of the Butterflies. The first tip was that drivers were remarkably reluctant to go. Although every single Monarch butterfly in Eastern North America heads for an inactive volcano that is only forty miles West of Mexico City the second largest city in the world, the trip was said to be too far to go. The roads, they are bad, the car is old, the way it is not well marked, and several other things as well. Mexico being what it is, this implausible resistance was first viewed as a way to extract a higher fee for going there, but in fact, there was a genuine worry about banditos. What is more, the roads they were in fact bad, and the car was definitely old. Admittedly, that did not match up with driving one-handed at break-neck speed.

|

| Cattle |

When we reached a place where even Roberto could not drive the car further, we transferred to the back of a cattle truck, driven by Pedro, who also waved a cigarette with his free hand while we lurched and rattled up the mountain. At least he had one hand on the steering wheel, while we in the back of the truck had to clutch the wooden railing. Roberto had climbed into the back of the truck; he had decided he wanted to see these butterflies, too. It was hot when we started, so we wore T-shirts. But by the time the truck lurched to its final stop next to the souvenir shop, it was plenty cold. Butterflies seem to like it cold. What now? Now, you walk.

At fifteen (?) thousand feet, your feet feel glued to the rocks you are climbing, but the trees of the sanctuary are within sight. And it is well worth the climb to come to the six hundred acres on top of a mountain, where every Monarch butterfly on the continent is either present or trying to get there. Butterflies from Texas, butterflies from Winnipeg, and somewhere in that mass were butterflies from Philadelphia. The butterflies were three feet deep on the ground, and hanging in huge balls from the limbs of trees. They don't make much noise, possibly being too busy looking for the ideal mate from the personals columns. The local guide said the really remarkable sight is on a certain day in the spring, when they all take off at once, heading for home.

The sad news, unfortunately, is that the local Mexicans are cutting down the trees in the Sanctuary for the wood. We may soon see whether the butterflies go to some other hilltop, or whether we have seen the last of them.

Abortion

The official position of the Pennsylvania Medical Society on the topic of abortion is, we have no position on abortion. I ought to know because I was the author of this position, proposed at a moment when the PA Medical House of Delegates was obviously going nowhere. After two hours of angry debate, we had to stop before we split into two warring medical societies. The Pennsylvania delegation to the AMA was then obliged to hold the same no-position on a national level. As I recall, our position was likewise greeted by the AMA House of Delegates with great relief, and word quickly circulated in the corridors that Pennsylvania had a position everyone could endorse for the good of the organization. For several years, this no-position position was widely referred to whenever the topic threatened to arise. It almost invariably stopped the discussion in its tracks, as it was intended to do. In going back over the minutes, it would appear the AMA never actually voted to adopt a no-position motion, a discovery that surprised but did not change the basic determination to let the rest of the nation settle this. We were going to stay out of it.

|

| Roe vs. Wade |

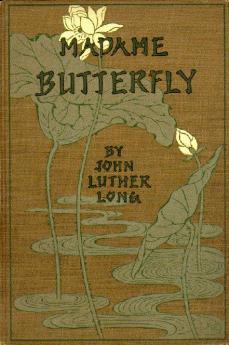

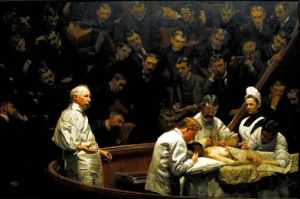

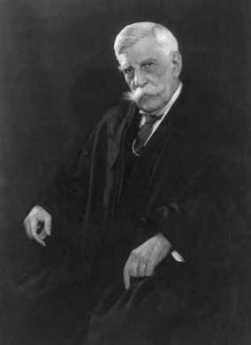

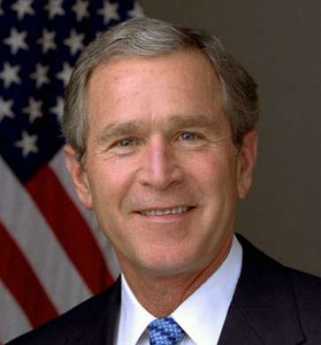

Because, one hundred forty years earlier, we started it. If you actually read Justice Blackmun's opinion for the majority in Roe v. Wade, as very few agitated proponents seem to have done, the original medical origin is clearly laid out. Blackmun had been a lawyer for the Mayo Clinic before his appointment to the Supreme Court, acquiring unusual medical resources and experiences for a lawyer. Now prepare for a logical leap, to the The Gross Clinic, Thomas Eakins masterpiece painting of Philadelphia's pre-eminent surgeon in a black frock coat, holding a dripping crimson scalpel in his bare hand, encapsulates the original situation. Note carefully that anesthesia is being given to the patient, but the surgeon is not wearing a cap, mask, gown, or rubber gloves.

|

| Gross Clinic |

In 1850 medical science had progressed into a forty-year time window when anesthesia made abortions painless, but Pasteur had still not identified bacteria, and Lister had not devised a way to cope with them. Abortions, common in ancient Greece but forbidden by Hippocrates, suddenly were widely demanded by 19th Century women in a situation when their judgment was vulnerable. Abortions were easy to do, all right, but women died like flies from the resulting infections, and the American Medical Association was distraught about it. The Oath of Hippocrates was brought forward to emphasize its prohibition of abortion, and the performance was made unethical for a member of the Association, sufficient cause to warrant expulsion. When that proved inadequate, the delegates agreed to go to their local state legislatures and seek legislation prohibiting the performance of abortion by anyone, member or non-member of the Association. These laws were quickly passed, and it was the Texas version which was overturned by Roe v. Wade as an unconstitutional denial of privacy. Roe was a pseudonym for the patient, and Wade was then Attorney General of Texas, the officer charged with enforcing Texas law. By 1900 abortions became both easy and safe for the mother, and by 1911 the AMA had reversed its position. The scientific surgical situation is well illustrated by a later famous painting about Philadelphia surgery by Thomas Eakins, the Agnew Clinic, in which the surgical team is portrayed in its modern costume of sterile gowns and rubber gloves. But it didn't matter since by that time various churches had hardened their doctrines. Religious leaders and their constituent politicians simply no longer cared what the medical profession thought about it. For at least the following century, ideological combatants were plainly only interested in whether physician opinion might advance one side or the other of their argument with useful official statements. Our real position, if anyone cares, is that we started out seeking protection for the safety of the mother, but the issue got twisted by others into disputes about the welfare of the unborn fetus.

|

| Agnew Clinic |

Since this is the case, there plainly may be a reason for state legislatures to reconsider the state laws they passed in the 19th Century, during that forty-year window of time when the scientific facts were in transition. But when a leap is made by the appointed referees of the federal government to overturn state laws, even about a basically medical issue, there has to be some legal reason to intervene; a medical reason somehow doesn't count. Justice Blackmun's discovery of an unnoticed right to "privacy" in the Constitution, where the word does not appear, is just too hard for us non-lawyers to deal with. Suppose we leave the fine points of the Bill of Rights to those constitutional lawyers. What's at stake here, among other things, of course, is whether the Federal Courts are justified in overturning well-intentioned state laws which had served well for at least fifty years -- simply out of impatience with the sluggishness and political timidness of state legislatures to revise obsolete laws. That's unbalancing the Constitution for a comparatively minor cause. Even major cause is something we have agreed to adjust in other ways, by amendment, not judicial opinion. And that's my opinion, having comparatively little to do with abortion.

AFSC: American Friends Service Committee

Two things uniquely characterize the work of the Friends Service Committee (AFSC): it's often both dangerous and unpopular. That's not required for relief following Indonesian tidal waves perhaps, but the work that really needs someone to do is often both dangerous and controversial.

The Service Committee was founded in 1917, mostly by Rufus Jones and Henry Cadbury, as a way of helping conscientious objectors to World War I. The Mennonites, the Brethren, and the Quakers were opposed to all wars, not just that particular one, but two of those religions are of German ancestry, and lacked the same credibility of the English-origin Quakers in a war with English allies against the Huns, Boche, and Kaiser enemies. The early focus of the Committee was on the Field Service, or Ambulance Corps; which was plenty close to the action, and plenty dangerous. After the War, the defeated German population was starving, and the Quaker Herbert Hoover directed the relief effort with great credit to the Quaker name, and immense European gratitude.

After that, when German Jews were suffering persecution by the Hitler administration, the Quakers initially responded in a uniquely Quaker way. Rufus Jones and two other Quakers went to see Reinhard Heydrich, to tell him the world disapproved of his behavior. They fully realized they represented a pool of important world opinion, particularly within Germany, and it was time to speak truth to Power. The Germans left the room to confer, and the three Quakers bowed their heads in silent prayer. Apparently, the room was tape recorded, and when the German officials returned, they did promise some efforts to improve matters. As the situation for the Jews soon got much worse, many Quakers risked a great deal to shelter and rescue the persecuted exiles. Relief to the defeated German populace had to be repeated after that war, as well. Each effort built up more credibility to be able to switch sides for the next effort, and the sincerity has seldom been seriously questioned.

The Japanese were also our hated enemies in World War II, and once more a long history helped the relief effort. Nearly 100,000 American citizens of Japanese origin were interned on the West Coast as potential traitors in 1941, often under deplorable conditions. Clarence Pickett was a director of AFSC at the time, and his sister had spent years in Japan as a missionary, so his remonstrations with the American government were prompt and credible. One of the more active workers was Esther Rhoads, sister of the famous surgeon, who had spent time in Japan earlier. One of the ingenious efforts with the Nisei was to assist 4,000 of them to get into college and find them hostels and jobs while they were away at school. Many of these college students later became prominent in various ways, greatly assisting the post-war reconciliation between the two countries.

|

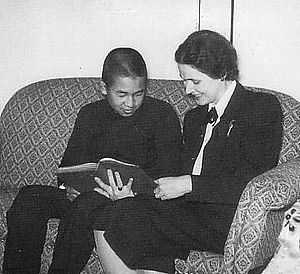

| Prince Akihito and Elizabeth Gray Vining |

Two Quaker ladies at the AFSC made a totally unique contribution when a request was received to provide a suitable tutor for the Crown Prince, now Emperor. He didn't convert to Christianity, but he later married a Christian, and you can be sure he got a plenty good dose of Quaker style and belief from Elizabeth Gray Vining. This tall, strikingly handsome Philadelphia woman had Bryn Mawr written all over her and turned heads whenever she entered a room. When she went back home, she was followed as a tutor for seven years by, guess who, Esther Rhoads who by then was the director of the Tokyo girls school. It remains to be seen, of course, what the final outcome of this deeply emotional situation will prove to have been. At the moment, the main sufferer seems to be the immensely talented American-educated woman who married the Emperor. But we will see; these are all powerful women in a very quiet way, unaccustomed to losing. One wishes the royal family all the best in their sometimes difficult position.

And then the Service Committee did its work in Vietnam, in Iraq, in Zimbabwe, and Somalia on the unpopular side, in every case. There are stories of venturing into war zones with hundred-dollar bills scotch-taped to their torso, where every fifty feet there was someone who would cut your throat for a dime. One worker in Laos entertained a group of us tourists with tales of living for weeks with nothing to eat but grasshoppers and cockroaches. Dangerous, unpopular, and uncomfortable. It sounds like a wonderful outlet for someone who is a perpetual rebel without a cause, but if you can find one of those at the Service Committee, you must have done a lot of looking.

The Service Committee, like the Quaker school system, is mostly run by non-Quaker staff. That means that neither of them exactly speaks for the religion itself. This little religious group of 12,000 members is stretched thin to provide a vastly greater world influence than its numbers imply. Hidden in the secrets of the group is an enduring ability to attract sincere non-member adherents to their work. And a quiet watchfulness to avoid losing control to any wandering rebels without a cause.

REFERENCES

| Window for the Crown Prince: Akihito of Japan, Elizabeth Gray Vining ISBN-13: 978-0804816045 | Amazon |

Battleship New Jersey: Home is the Sailor

|

Home is the sailor, wrote A. E. Housman, Home from the sea. In this case, the sailor is the Battleship New Jersey. The U.S.S. New Jersey rides at permanent anchor in the Delaware River, tied to the Camden side. You can visit the ship almost any afternoon, and with reservations can even throw a nice cocktail party on the fantail. It's an entertaining thing to do under almost any circumstances, but the trip is more enjoyable if you spend a little time learning about the ship's history. The volunteer guides, many of them still grizzled veterans of the ship's voyages, will be happy to fill in the details.

In the first place, the ship's final bloody battle was whether to moor the ship in the Philadelphia harbor, or New York harbor, when the U.S. Navy had got through using it. You can accomplish that and remain in the state of New Jersey either way, but there's a big social difference between North Jersey and South Jersey, so the negotiations did get a little ugly. Because of the way politics go in Jersey, it wouldn't be surprising if a few bridges and dams had to be built north of Trenton to reconcile the grievance, or possibly a couple of dozen patronage jobs with big salaries but no work requirement. The struggle surely isn't over. Battleships are expensive to maintain, even at parade rest; if you don't paint them, they rust. Current revenues from tourists and souvenirs do not cover the costs, so the matter keeps coming up in corridors of the capitol in Trenton.

Home is the sailor, home from sea:

Home is the hunter from the hill:

'Tis evening on the moorland free,

|

|

A. E. Housman

R.L.S. |

Battleship design gradually specialized into a transport vehicle for big cannon, ones that can shoot accurately for twenty miles while the platform bounces around on the ocean surface. Situated in turrets in the center of the vessel, they can shoot to both sides. That's also true of armored tanks in the cavalry, of course, with the history in the tank's case of the big guns migrating from the artillery to the cavalry, causing no end of a jurisdictional squabble between officers trained to be aggressive for their teams. Originally, the sort of battleship which John Paul Jones sailed was expected to attack and capture other vessels, shoot rifles down from the rigging, send boarders into the enemy ships with cutlasses in their teeth, and perform numerous other tasks. In time, the battleship got bigger and bigger so in order to blow up other battleships had to sacrifice everything else to sailing speed and size of cannon. Protection of the vessel was important, of course, but in the long run, if something had to be sacrificed for speed and gunpowder, it was self-protection. There's a strange principle at work, here. The longer the ship, the faster it can go. Almost all ocean speed records have been held by the gigantic ocean liners for that reason. If you apply the same idea to a battleship, the heavy armored protection gets necessarily bigger, and heavier as the ship gets longer, and ultimately slows the ship down. As a matter of fact, bigger and bigger engines also make the ship faster, until their weight begins to slow them down. Bigger engines require more fuel and carrying too much of that slows you down, too. Out of all this comes a need for a world empire, to provide fueling stations. Since the Germans didn't have an empire, they had to sacrifice armor for more fuel space and more speed, to compensate for which they had to build bigger guns but fewer of them. Although the British had more ships sunk, they won the battle of Jutland because more German ships were incapacitated. When you are a sailor on one of these ships, it's easy to see how you get interested in design issues which may affect your own future. An underlying principle was that you had to be faster than anything more powerful, and more powerful than anything faster.

The point here is that the New Jersey, as a member of the Iowa class of battleship, was arguably the absolutely best battleship in world history. At 33 knots, it wasn't quite the fastest, its guns weren't quite the biggest, its armor wasn't quite the thickest, but by multiplying the weight of the ship by the length of its guns and dividing by something else you get an index number for the biggest worst ship ever. The Yamamoto and the Bismarck were perhaps a little bigger, but the New Jersey was at least the fastest meanest un-sunk battleship. Air power and nuclear submarines put the battleship out of business so the New Jersey will hold the world battleship title for all time. Strange, when you see it from the Ben Franklin Bridge, it looks comparatively small, even though it could blow up Valley Forge without moving from anchor.

One story is told by Chuck Okamoto, a member of the Green Berets who was sent with a group of eight comrades into a Vietnamese army compound to "extract" an enemy officer for interrogation. When enemy flares lit up the area, it was clear they were facing thousands of agitated enemy soldiers, and Okamoto called for air support. He was told it would take thirty minutes; he replied he only had three minutes, and to his relief was told something could be arranged. Almost immediately the whole area just blew up, turned into a desert in sixty seconds. The guns of the New Jersey, twenty miles away, had picked off the target. The story got more than average attention because Okamoto's father was Lyndon Johnson's personal photographer, and Lyndon called up to congratulate.

A number of similar stories led to the idea that naval gunfire might have destroyed some bridges in Vietnam which cost the Air Force many lost planes vainly trying to bomb, but, as the stories go, the Air Force just wouldn't permit a naval infringement of its turf. This sort of second-guessing is sometimes put down to inter-service rivalry, but it seems more likely to be just another technology story of air power gradually supplanting naval artillery. Plenty of battleships were sunk by bombs and torpedo planes before the battleship just went away. If you sail the biggest, worst battleship in world history, naturally you regret its passing.

Tourists will forever be intrigued by the "all or nothing" construction of the New Jersey. Not only are the big guns surrounded by steel armor three feet thick, but the whole turret for five stories down into the hold is also similarly encased in a steel fortress. This design traces back to the battle of Jutland, where a number of battlecruisers were blown up because the ammunition was stored in areas of the hold not nearly so protected as the gun itself. Putting it all within a steel cocoon lessened that risk, and had the side benefit that when ammunition accidentally exploded, the damage was confined within the cocoon. It must have been pretty noisy inside the turret when it was hit, sort of like being inside the Liberty Bell when it clangs. But not so; stories have been told of turrets hit by 500-pound bombs which the occupants didn't even notice. The term "all or nothing" refers to the fact that the gun turrets are sort of passengers inside relatively unprotected steering and transportation balloon. In order to save weight, most of the armor protection is for the gun. That's a 16/50, by the way. Sixteen inches in diameter, and fifty times as long. With the weight distributed in this odd manner, the Iowa class of dreadnought was more likely to capsize than to sink. Accordingly, the interior of the hull is broken up into watertight compartments, serviced by an elaborate pumping system. Water could be pumped around to re-balance a flooded hull perforation, certainly a tricky problem under battle conditions.

Barbarians At the Gates of the Magical Kingdom

|

| Mickey Mouse |

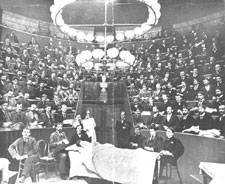

The Walt Disney Corporation held its annual stockholder meeting on March 3, 2004, in Philadelphia's Convention Center. There were only five items of business: the re-election of directors (no names on the ballot in opposition), re-appointment of the auditors ( reappointed every year for twenty-eight previous years), and three stockholder proposals ( overwhelmingly defeated several times in the past). Typical stockholder meetings leisurely dispose of such an agenda in about twenty minutes. This one took seven hours.

There could well have been two unstated reasons for the protracted meeting. The first would be self-inflicted: direct advertising to thousands of small stockholders at an entertainment, including costumed cartoon characters, movie excerpts promoting coming attractions, and a chance at the microphone to tell the world who you are and what you think. Such promotion is even more effective if the meeting city shifts each year.

This year it was Philadelphia's turn to see the sights, including top executives in new suits and Ronald-Reagan shirt collars. Several thousand true believers in the American Dream did show up, many of them bringing little children, taking almost three hours to get through an airport-like electronic frisking by four harried security guards. The guards seemed particularly concerned to prevent live cell phones from entering the meeting.

Secondly, the meeting gave all the signs of a covert filibuster. It even had a professional: Senator George Mitchell, the former Democratic majority leader of the U.S. Senate, was on hand to advise. After all, a frivolously protracted meeting is collapsible if discussions get out of hand, because the audience has already become impatient. Comcast, with corporate headquarters only three blocks from this Convention Center, had an active offer to acquire Disney, instantly rejected by the Disney board. As soon as the offer was announced, the price of Disney stock jumped four dollars a share, enriching every shareholder in the room a collective $8 billion. Why not accept it? The new price now made the offer seem too low, by some perplexing reasoning. Allowing a succession of irrelevant speeches positions the chairman of the meeting to smother, in the interest of fairness to all, and gathering momentum for Comcast. In the event, it did actually delay this meeting's announcement of voting outcome, which was called for 8 AM, until past the close of the New York Stock Exchange in the late afternoon. Meanwhile, the message was encouraged that love of cartoons, wholesome television, and family vacations was more appealing to true stakeholders of Disney than vertical integration and short-term (read, short-sighted) profits.

|

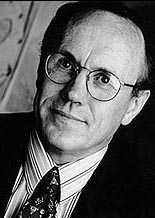

| Michael Eisner |

It didn't go that way; hardly a word was said about Comcast. Instead, the true believers, led by the nephew of Walt Disney, made it clear that they were turned off by speeches filled with business school lingo, like enhancing the brand, protecting the franchise, and growing the business. They didn't understand all that, but they did understand that the American heartland was being asked to pay eight and nine-figure incomes, year after year, to people who obviously worshiped in the financial cultures of the East and West coasts. The most telling remark was that the company had good years and bad years, but Michael Eisner the CEO -- never seemed to have a bad year. Stockholders were urged to withhold their votes from him.

To some extent, any management engaged in a proxy battle has some justification for limiting the attendance at a stockholders meeting, because arbitragers will almost always try to support a hostile proposal. Stockholders who bought their shares a few days before the vote have interests which conflict with the long-term stockholders since a short term jump in stock price will probably evaporate if the proposal is defeated. Many of the people in the audience are only there to assess whether the proposal is likely to be successful, so as to buy more shares or sell what they have; some of the people at the microphone are potentially interested only in misleading these observers. The wise guys in the audience were agreed that Comcast had made a mistake announcing its offer after the date had passed when newly-purchased shares were eligible to vote.

In the end, over a thousand people stuck it out to hear the ballot results. After seven hours, someone moved for adjournment, the chairman heard a second, a scattering of eyes followed, and he never called for the nays. He was half-way to the door when a thousand howls were raised, demanding the results of the vote. Oops, sorry. An accountant was summoned to drone out interminable numbers, one by one. It seems that seven hundred million shares had withheld approval from the CEO, 43% of the votes cast. Mr. Eisner, to his credit, didn't show a flicker of emotion on his televised face, and duly announced that all directors had been re-elected, the auditors re-appointed, and the stockholder resolutions defeated. Maybe so, but at the board reorganization meeting which followed, Eisner was removed from the Chairmanship although retained as CEO. The more logical person to defend the Magic Kingdom against predator Comcast was Roy Disney, of course, but to appoint management's public enemy would have been a bit much. Almost all of the board had themselves experienced at least 200 million votes withheld.

|

| Ned Johnson |

The real governance crisis which this carnival dramatizes was not mentioned. With nearly two billion shares outstanding, at $26 a share this company is valued at $52 billion. There were people at the microphone who owned 200,000 shares, but even their economic power is negligible in a corporation so large. It is the managers of mutual funds and pension funds who now control big-corporation voting, and have the real power to decide on mergers and take-overs. Mutual funds and pension funds, like Ned Johnson at Fidelity who controls a trillion dollars of various stocks, are the ones with the votes. In the past, such managers have found it a bore to address five hundred or more proxy statements each spring. They find it hard enough to hire analysts who can pick a good company, let alone picking executives to make a bad company into a good one. As fund ownership has spread, however, there is uncomfortably little left to buy if a diversified fund does much selling. Diversification is almost a sure winner; picking executives is too much like picking racehorses.

So, in the end, the restless stockholders were guided by only one perception: Eisner controlled his own pay and took too much for himself. Too much diversification of stock ownership has led to the dispersion of control. And dispersed control has led to control by outcry. Those friends of capitalism who dread government regulation had better rapidly devised some alternatives.

Bertrand Russell Disturbs the Barnes Foundation Neighbors

|

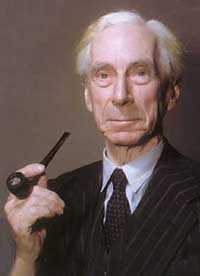

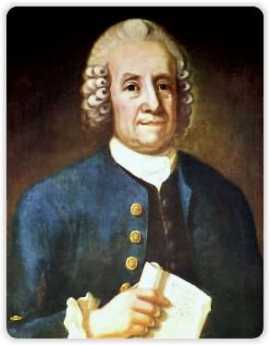

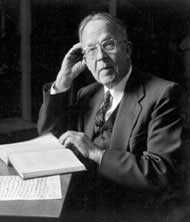

| Russell |

In 1940, the Barnes Foundation disturbed its Philadelphia's Main Line neighborhood in a way that had nothing to do with art. Dr. Barnes was still alive and running the place at that time so there can be no question about the testamentary intentions of the donor. He hired Bertrand Russell for a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Foundation, under highly lurid circumstances. By doing so, he put his thumb in the eye of religions generally but especially the Roman Catholic Church, into the eye of the Main Line neighborhood that prized its privacy, and into the eye of the judiciary, although the judiciary found a way to get back at him.

Do not fear to be eccentric in opinion, for every opinion now accepted was once eccentric.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

Under the circumstances, hiring anyone at all would have been socially defiant, but Barnes went out of his way to offer a position to a man who was already internationally famous for sticking his own thumb in everybody's eye.

Lord Bertrand Russell was the third Earl, the son of a Viscount and the grandson of a British prime minister. He had such a brilliant mathematical mind that no less an observer than Alfred North Whitehead regarded him as the smartest man he ever met. He burned up the academic track at Trinity College, Cambridge, and was made a Fellow of the Royal Society at an early age. There was absolutely no one in the academic world who could look down on him, particularly no one in any American community college. His association with Haverford Quakers was established by marrying Alys Pearsall Smith, a rich thee-and-thou Quakeress then living in England, whose brother was the famous author Logan Pearsall Smith. Many early letters of Bertrand Russell contain instances of what the Quakers call "plain" speech.

If a man is offered a fact which goes against his instincts, he will scrutinize it closely, and unless the evidence is overwhelming, he will refuse to believe it. If, on the other hand, he is offered something which affords a reason for acting in accordance to his instincts, he will accept it even on the slightest evidence.

|

| Bertrand Russell |

By the time of World War I, this odd mixture of Quaker pacifism and English aristocratic arrogance seems to have unhinged Russell from social moorings, and he began a lifelong career of defiance mixed with a rapier wit that made just about everybody his enemy. He went to jail for pacifism, got divorced three or four times, openly slept with the wives of famous people like T.S. Eliot, and proclaimed that monogamy was not a natural state for anybody. He wrote ninety books, and his denunciation of religion was sweeping. All religious ideas were, in his view, not only false but harmful. Accordingly, everybody in polite society kicked him out, and although he was entitled to a seat in the House of Lords, by 1939 he was nearly impoverished. In desperation, he went to (ugh) America to seek his fortune. He didn't last at the University of Chicago, and even California eased him out. Finally, he was reduced, if you can imagine, to accepting an offer to teach Philosophy at the City College of New York. That proved to be totally unacceptable to Bishop Manning, who led a public outcry against using public funds to support such a radical, known to have held long conversations with Lenin. When a CCNY student was induced to file suit along those lines, an especially hard-nosed judge overturned the College appointment, with the rather gratuitous declaration that Russell's appointment would establish a Chair of Indecency. At that point, Albert Barnes stepped in and offered Russell a five-year contract to teach philosophy at the Barnes Foundation on Philadelphia's main line.

|

| Bertrand Russell in 1960s regalia. |

Bertrand Russell the bomb-thrower accepted the offer and came down to that quiet little lane where the neighbors object to the traffic coming to look at pictures. The five-year contract only lasted three years, when even Barnes got fed up, and summarily dismissed him. The circumstances have not been extensively documented, but they were sufficient to enable Russell to win a lawsuit for a redress of grievances. During that three year period on the Main Line, he had produced a book called History of Western Philosophy, which became a best seller and permanently relieved his financial difficulties, and was the basis for his winning the Nobel Prize in Literature. He spent the rest of his ninety-odd years leading demonstrations against the atom bomb, the Vietnam War, monogamy, religion and so on. There are those who regard Bertrand Russell as the role model for the whole Sixties generation, and, unfairly, the 2004 Democrat candidate for President. However, all that may be, his activity at the Barnes Foundation undoubtedly was a factor in the firm but the unspoken tradition of the Merion Township neighbors that they wanted to get that Art Gallery out of here.

Cecilia Beaux, Portraitist of the Grand Manner

|

| Cecilia Beaux |

Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942) was certainly the most famous woman portraitist of her time. She had the misfortune of being a contemporary of Mary Cassatt, who enjoyed the reputation of the finest woman Impressionist at a time when the Art world disdained traditional painting techniques in an Impressionist stampede. So, although these two temperamental artists might never have been chums, much of their famous rivalry was probably invented for them by art world politicians.

In time, the assessment will emerge that these two well-born Philadelphia ladies were each the world's female leaders of two competing schools of art. Comparisons of the two will also have to be filtered through the fact that Cassatt was a rebel who spent most of her life in Paris, while Beaux was a prominent faculty member of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts for twenty years. Strikingly beautiful herself, she was gifted, elegant and fiercely ambitious. Meow.

|

Once Beaux had established a reputation as a portrait painter, she shrewdly began to select her subjects. She wanted famous men (Henry James, for example) and beautiful women subjects. She made the mistake of turning down her niece, Catherine Drinker Bowen, because she didn't have the right kind of cheekbones. She learned, of course, that it's unwise to tell a famous author she is ugly.

|

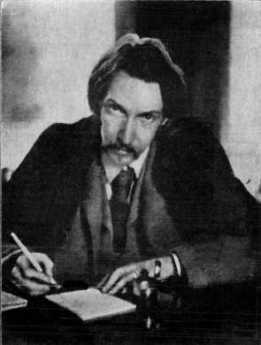

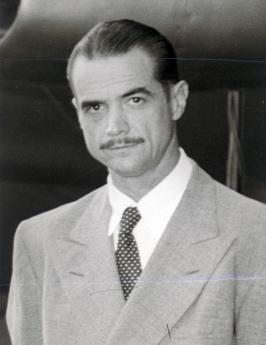

| Robert Louis Stevenson |

Cecilia Beaux's main competitor in the portrait game was John Singer Sargent, who was if anything a better painter but a stammering social dud. Sargent remained a life long bachelor, Beaux a spinster. Her mother had died in childbirth, and it seems likely that terror of pregnancy was an important part of her personality, during the pre-antibiotic era when such fear was fairly justified. As a young woman, she turned down proposals by the dozen, and in maturity, she had a succession of apparently platonic but intense relationships with handsome men twenty years her junior. During the late Victorian era, this sort of thing was not rare, although medical advances have apparently largely eliminated it. To return to her competition with Sargent, the personality differences probably account for his haunting portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson, while Beaux is notable for arresting portraits of rich, famous and beautiful women, and an equal number of well-dressed, handsome men.

Charles Peterson and Amity Buttons

|

| Charles Peterson |

Charles Peterson, the famous architectural historian and preservationist, died just before his 98th birthday on August 19, 2004. It is to him we largely owe the redevelopment of Society Hill, and the design of the Independence National Park, as well as a host of restorations from the Adams Mansion of Quincy, Massachusetts, to the early French settlements along the Mississippi. He conceived of many national historic preservation projects, the most notable of which is the Historic American Buildings Survey (HASB) of the Department of the Interior.

|

| The Adams Mansion |

While he was most notable for large visions and huge projects, he also had a keen appreciation for fastidious accuracy in small matters, of which the Amity Button would be a vivid example. In the surviving Colonial buildings of Philadelphia, it is common to find a plain ivory coat button nailed to the top of the newel post of the main staircase. There's one in Independence Hall, another in the grand staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, and there is one in Charlie Peterson's own home, the one where he was the first Society Hill gentrification pioneer, a house originally built by Stephen Girard around 3rd and Spruce.

|

|

The Free Quaker Meeting House |

There is a strong tradition in Philadelphia that these strange buttons are Amity Buttons, nailed there by the Quaker builder at the moment when the new owner had fully settled his construction debt, symbolizing the amity between a willing buyer and a willing seller. Countless visitors to Society Hill have been shown these curious buttons, and it always seems to produce a warm glow of appreciation for the discovery. If you have one of these in your own house, you can be very proud.

Unfortunately, Charlie Peterson couldn't find any evidence for the truth of this fable, and you can be sure he subjected the matter to a totally dedicated search. You might think there would be some notations in the deeds, or in the correspondence of the day, or in the literature of the times. You would think that someone who repeats this tale would be able to relate where he got it, and that would lead to some letters in an attic, and that if you work hard enough, you will find it. But when the button matter came up, Mr. Peterson would suddenly become grim-lipped and sad, and repeat the mantra that there is no evidence to support the story. He even awarded prizes to architectural students for essays on newel posts, banisters, and stair rails, but no student essay ever turned up any authentication of the Amity Button story. Absence of evidence is of course not the same as evidence of absence, so it is remotely possible that the story will someday be vindicated.

Indeed, you have to believe there was something or other to start the story. Victor Failmetzger and his wife, who have a notable reputation for authenticating old house parts, relate that in Colonial Virginia it was common to have hollow newel posts on the stairway, and occasionally to find the deed to the house secreted in one of them. So the search goes on.

In fact, it always seemed likely that Charles Peterson very much wanted to believe the fable was true. But until some evidence turned up, he was going to go to his grave with the declaration that there existed no evidence for it.

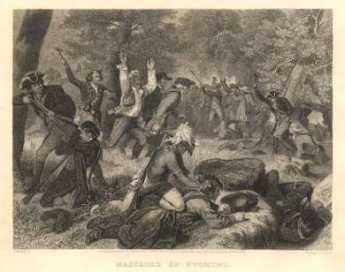

Washington Lurks in Bucks County, Waiting for Howe to Make a Move

|

| Moland House |

Although Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is staunchly Republican, it has been home to Broadway playwrights for decades; this handful of Democrats have long been referred to as lions in a den of Daniels. One of them really ought to make a comic play out of the two weeks in August 1777, when John Moland's house in Warwick Township was the headquarters of the Continental Army.

John Moland died in 1762, but his personality hovered over his house for many years. He was a lawyer, trained at the Inner Temple and thus one of the few lawyers in American who had gone to law school. He is best known today as the mentor for John Dickinson, the author of the Articles of Confederation. Our playwright might note that Dickinson played a strong role in the Declaration of Independence, but then refused to sign it. Moland, for his part, stipulated in his will that his wife would be the life tenant of his house, provided -- that she never speak to his eldest son.

Enter George Washington on horseback, dithering about the plans of the Howe brothers, accompanied by seven generals of fame, and twenty-six mounted bodyguards. Mrs. Moland made him sleep on the floor with the rest.

Enter a messenger; Lord Howe's fleet had been sighted off Patuxent, Maryland. Washington declared it was a feint, and Howe would soon turn around and join Burgoyne on the Hudson River. Washington had his usual bottle of Madeira with supper.

A court-martial was held for "Light Horse Harry" Lee, for cowardice. Lee was exonerated.

Kasimir Pulaski made himself known to the General, offering a letter of introduction from Benjamin Franklin, which letters Franklin noted had been requested by Pulaski himself. As it turned out, Pulaski subsequently distinguished himself as the father of the American cavalry and was killed at the Battle of Savannah.

|

| Lafayette |

And then a 19 year-old French aristocrat, the Marquis de Lafayette, made an appearance. Unable to speak a word of English, he nevertheless made it clear that he expected to be made a Major General in spite of having zero battlefield experience. He presented a letter from Silas Deane, in spite of Washington having complained he was tired of Ambassadors in Paris sending a stream of unqualified fortune hunters to pester the fighting army. Deane did, however, manage to make it clear that the Marquis had two unusually strong military credentials. He was immensely rich, and he was a dancing partner, ahem, of Marie Antoinette.

In Mrs. Moland's parlor, Washington sat down with Lafayette to tap-dance around his new diplomatic problem. It was clear America needed France as an ally, and particularly needed money to buy supplies. But it was also clearly impossible to take a regiment away from some American general, a veteran of real fighting, and give that regiment to a Frenchman who could not speak English and who admitted he had no military experience. Fumbling around, Washington offered him the title of Major General, but without any soldiers under his command, at least until later when his English improved. To sweeten it a little, Washington seems to have said something to the effect that Lafayette should think of Washington as talking to him as if he were his father. There, that should do it.

It seems just barely possible that Lafayette misunderstood the words. At any rate, he promptly wrote everybody he knew -- and he knew lots of important people -- that he was the adopted son of George Washington.

Well, Broadway, you take it from there. At about that moment, another messenger arrived, announcing Lord Howe at this moment was unloading troops at Elkton, Maryland. General Howe might have been able to present his credentials to Moland House in person, except that his horses were nearly crippled from spending three weeks in the hold of a ship and needed time to recover. Heavy rains were coming.

(Exunt Omnes).

Suggested Stage Manager: Warren Williams

Contemporary Germantown

The Strittmatter Award is the most prestigious honor given by the Philadelphia County Medical Society and is named after a famous and revered physician who was President of the society in the 1920s. There is usually a dinner given before the award ceremony, where all of the prior recipients of the award show up to welcome to this year's new honoree.

|

| Bockus |

This is the reason that Henry Bockus and Jonathan Rhoads were sitting at the same table, some time around 1975. Bockus had written a famous multi-volume textbook of gastroenterology which had an unusually long run because it was published before World War II and had no competition during the War or for several years afterward; to a generation of physicians, his name was almost synonymous with gastroenterology. In addition, he was a gifted speaker, quite capable of keeping an audience on the edge of their chairs, even though after the speech it might be difficult to recall just what he had said. On this particular evening, the silver-haired oracle might have been just a wee bit tipsy.

Jonathan Rhoads had likewise written a textbook, about Surgery, and had similarly been president of dozens of national and international surgical societies. He devised a technique of feeding patients intravenously which has been the standard for many decades, and in his spare time had been a member of the Philadelphia School Board, a dominant trustee of Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges, and the provost of the University of Pennsylvania. Not the medical school, the whole university, and is said to have been one of the best provosts of the University of Pennsylvania ever had. When he was President of the American Philosophical Society, he engineered its endowment from three million to ten times that amount. For all these accomplishments, he was a man of few words, unusual courtesy -- and a huge appetite in keeping with his rather huge farmboy physical stature. On the evening in question, he was busy shoveling food.

"Hey, Rhoads, wherrseriland?". Jonathan's eyes rose to the questioner, but he kept his head bowed over his plate.

"HeyRhoads, Westland?" The surgeon put down his fork and asked, "What are you talking about?"

"Well," said Bockus, "Every famous surgeon I know, has a house on an island, somewhere. Where's your island?

"Germantown," replied Rhoads, and returned attention to his dinner.

Working Girls Get the Faints

|

| Curtis Building |

Curtis Publishing Company once covered a full city block of Philadelphia, from Sixth to Seventh Streets, Walnut to Chestnut. The northern half of this complex was the Public Ledger Building, once housing a failed diversification move into newspaper publishing and later rented out as commercial office space after the newspaper died. On the top floor of the Ledger Building was the Down Town Club, quite a palatial meeting place for the whole publishing industry which stretched for blocks around. Both Curtis-owned buildings have the same architectural design and together make a massive looming presence next to Independence Hall on one street and Washington Square on the other. To build from Walnut to Chestnut means shutting off Sansom Street in the middle, and that permits the jewelry trade to nestle in a cul de sac on the West side of the publishing complex.

So Curtis was once a little city within a city, and most of the rest of the town only saw its facade and the crowds of people coming and going through the entrances. To a neighborhood doctor on an emergency call, however, it was almost exclusively inhabited by young women. Kitty Foyles, you might say. I certainly formed that impression after having a medical office two blocks away, getting occasional calls.

|

| Christopher Morely |

So far as I can remember, Curtis had only one medical problem, repeated over and over. An anguished call would come that someone at Curtis was unconscious, come immediately, take the elevator to the third or fourth or fifth floor. At the elevator, the doctor would be met by a somewhat older woman, obviously the den mother of the working girls. Into the ladies room, we would go, where a young woman was usually sitting on a couch looking sheepish, although occasionally she was still passed out. The key finding was a very slow pulse. She had fainted, she was better, and now what. It was Curtis policy to send the fainters home after the faint, and I never could see any particular objection to that.

For me, there were never any men to be seen, at Curtis. Surely there must have been dozens of writers and editors and advertising people, but somehow they would vanish when one of these fainting things happened. Curtis was nothing but women when I was there, mostly watching me like a beach full of seagulls, watching a fisherman.

Delaware's Court of Chancery

Georgetown, Delaware is a pretty small town, but it's the county seat so it has a courthouse on the town square, with little roads running off in several directions. The courthouse is surprisingly large and imposing, even more, surprising when you wander through cornfields for miles before you suddenly come upon it. The county seat of most counties has a few stores and amenities, but on one occasion I hunted for a barbershop and couldn't find one in Georgetown. This little town square is just about the last place you would expect to run into Sidney Pottier and all the top executives of Walt Disney. But they were there, all right, because this was where the Delaware Court of Chancery meets; the high and mighty of Hollywood's most exalted firm were having a public squabble. Only a few states still have a court of Chancery, but little Delaware still has a lot of features resembling the original thirteen colonies in colonial times. The state abolished the whipping post only a few decades ago, but they still have a chancellor. The Chancellor is the state's highest legal officer, and four other judges now need to share his workload, which was almost completely within his sole discretion seventy-five years ago. In fact, the Chancellor usually heard arguments in his own chambers, later writing out his decisions in longhand. The Court of Chancery does not use juries. Going back to Roman times, the Chancellor was the highest office under the Emperor, and in England, the Lord Chancellor is still the head of the bar in a meaningful way. Sir Francis Bacon was the most distinguished British Chancellor and gave the present shape to a great deal of the present legal system. A court of Chancery is concerned with the legal concept of equity, which is a sense of fairness concerning undeniable problems which do not exactly fit any particular law. The Chancellor is the "Keeper of the King's conscience" concerning obvious wrongs that have no readily obvious remedy. You better be pretty careful who gets appointed to a position like that, with no rules to follow, no supervisor, no jury, dealing with mysterious issues that have no acknowledged solution.

Delaware's Court of Chancery evolved in steps, with several changes of the state Constitution over a span of two hundred years. As you might guess, a few powerful chancellors shaped the evolution of the job. Going way back to 1792, Delaware changed its Supreme Court from the design of its Constitution, and George Read was the new Chief Justice. However, it was all a little embarrassing for William Killen, who had been the Chief Justice, getting a little old. Read refused to have Killen dumped, and in this he was joined by John Dickinson, who had been Killen's law clerk. So Killen was made Chancellor, and a court of Chancery was invented to keep him busy. Under a new 1831 Constitution, the formation of corporations required individual enabling acts by the Legislature and limited their existence to twenty years. However, the 1897 Constitution relaxed those requirements and permitted entities to incorporate under a general corporation law and allowed them to be perpetual. By this time, other states were distributing equity cases to the county level, but Delaware was too small to justify more than a single state-wide Court. That court was attractive to corporations because it could become specialized in corporate matters, but retained a pleasing number of equity cases among common citizens, thus retaining a folksy point of view. In unique situations or those without a significant history of public debate, it was thought especially desirable to strive for unchallenged acceptance of the court's decision. But other states thought they could see what Delaware was up to. In 1899 the American Law Review contained the view that states were having a race to the bottom, and Delaware was "a little community of truck farmers and clam-diggers . . . determined to get her little, tiny, sweet, round baby hand into the grab-bag of sweet things before it is too late." However, that may be, corporations stampeded to incorporate in the State of Delaware, and the equity of their affairs was decided by the Chancellor of that state. In one seventeen year period of time, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the decision of the Chancellor only once.

Some legal scholar will have to tell us if it is so, but the direction and moral tone of America's largest industries has apparently been shaped by a small fraternity or perhaps priesthood of tightly related legal families, grimly devoted to their lonely task in rural isolation. The great mover and shaker of the Chancery was Josiah O. Wolcott (1921-1938), the son and father of a three-generation family domination of the court. Most of the other members of the court have very familiar Delaware names, although that is admittedly a common situation in Delaware, especially south of the canal. The peninsula has always been fairly isolated; there are people still alive who can remember when the first highway was built, opening up the region to outsiders. Read the following Chancelleries quotation for a sense of the underlying attitude: "The majority thus have the power in their hands to impose their will upon the minority in a matter of very vital concern to them. That the source of this power is found in a statute, supplies no reason for clothing it with a superior sanctity, or vesting it with the attributes of tyranny. When the power is sought to be used, therefore, it is competent for anyone who conceives himself aggrieved thereby to invoke the processes of a court of equity for protection against its oppressive exercise. When examined by such a court, if it should appear that the power is used in such a way that it violates any of those fundamental principles which it is the special province of equity to assert and protect, its restraining processes will unhesitatingly issue." That is a very reassuring viewpoint only when it issues from a person of totally unquestioned integrity, a member of a family that has lived and died in the service of the highest principles of equity and fairness. But to recent graduates of business administration courses in far-off urban centers of greed and striving, it surely sounds quaint and sappy. And many of that sort have found themselves pleading in Georgetown. Just let one of them a bribe, muscle, or sneak into the Chancellor's chair someday, and the country is in peril. Dinner With Hoffa

Although she lived for twenty more years, in 1975 my mother was eighty years old. Nevertheless, she did not display the slightest surprise, or hesitation in answering, "Sure", when asked if she would like to have dinner with Jimmy Hoffa. One of her constant pleasures was to be doing things that other women couldn't match. The Philadelphia County Medical Society's Center City branch was having dinner, and the program chairman had the main goal in life of attracting speakers who would bring an overflow audience. Jimmy Hoffa, the former president of the Teamsters Union, recently released from prison, certainly filled that description; one of the members of the branch had a patient who was a teamster official who happened to know that Jimmy would love to speak to the doctors about medical care in prisons. Not only was he willing, but he also paid his own expenses to fly up from Florida to give the speech. As by far the oldest lady present, my mother was not to be denied when she demanded to be seated at the head table. Hoffa was indeed a charming person and an able proponent of his cause. He had experienced medical care in a prison, he felt mistreated, and the doctors in the audience were sympathetic to what they suspected was quite true. They generally began that evening with conflicting opinions, because it is generally known that doctors in the prison environment are often threatened, and occasionally harmed. We know quite well how reluctant the Legislature is to spend one cent on a group of people they dislike, and how they all wish the problem would just go away. By the end of the evening, Hoffa held his audience in his hand. No wonder he rose to the top of his organization. Well, the impact of the evening was certainly heightened, even in my mother's view, by the fact that two weeks later Hoffa just disappeared, and there have been hundreds of books and articles written about his probable grisly murder by the Mafia. The latest is called I Heard You Paint Houses, in which one Frank Sheeran is quoted as claiming, or even boasting, that he had been the hit man. I wouldn't know. The title, however, is reliably known to refer to all the blood which is found splattered about, following a mob rub-out. Calling them wise guys is quite apt. The reawakening of this topic by the book does raise some other old questions of the highest rank. Reviewing the evidence, it is possible to believe Hoffa was not guilty of precisely what Bobby Kennedy was accusing him of. At least, the prosecution failed to convince one jury of it. The FBI records do seem to indicate that J. Edgar Hoover offered him evidence of the questionable Kennedy private lives, which Hoffa refused to use in his defense in the trial. And there seems to be little doubt that he worked hard to elect Richard Nixon, or that Nixon later commuted his sentence. Generally speaking, he was on the side of the angels concerning Mafia influence in the Teamsters Union. But his strange relationship to Nixon and the Kennedy family is quite another matter, although equally obscure. Eakins and Doctors

A Christmas visitor from New York announced he read in the New York newspapers that Philadelphia's mayor had just rescued a painting called The Gross Clinic, for the city of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia physicians who heard this version of events from an outsider reacted frostily, grumpily, and in stone silence. To them, the mayor was just grandstanding again, and whatever the New York newspaper reporters may have thought they were saying was anybody's conjecture. Thomas Eakins is known to have painted the portraits of eighteen Philadelphia physicians. Several of these portraits have been highly praised and richly appraised, seen in the art world as part of a larger depiction of Philadelphia itself in the days of its Nineteenth-century eminence. That's quite different from its colonial eminence, with George Washington, Ben Franklin, the Declaration and all that. And of course entirely different from its present overshadowed status, compared with that overpriced Disneyland eighty miles to the North. Eakins depicted the rowers on the Schuylkill, and the respectable folks of the professions, every scene reeking with Victorian reminders. It's a little hard to imagine any big-city mayor of the present century in that environment. Indeed, it is hard to imagine most contemporary Americans in a Victorian environment -- except in Philadelphia, Boston, and perhaps Baltimore. So, Mayor Street can be forgiven for not knowing exactly what stance to take, and was not alone in that condition. S. Weir Mitchell, for example, became known as the father of neurology as a result of his studies and descriptions of wartime nerve injuries. But the repair of injuries is a surgical art, and many novel procedures were invented and even perfected, many textbooks were written. Amphitheaters were constructed around the operating tables, for students and medical visitors to watch the famous masters at work. In The Gross Clinic, we see the flamboyant surgeon in the pit of his amphitheater at Jefferson Hospital, in the background we see anesthesia being administered. Up until the invention of anesthesia, the most prized quality in a surgeon was speed. With whiskey for the patient and several attendants to hold him down, the surgeon had one or two minutes to do his job; no patient could stand much more than that. After the introduction of anesthesia, it might overwhelm newcomers to observe leisurely nonchalance, but in truth, the patient felt nothing, so the surgeon could safely pause and lecture to his nauseated admirers.

What made an operation dangerous was not its duration, but the subsequent complications of wound infection. By 1876, Eakins could have had no idea that Pasteur and Lister were going to address that issue in four or five years, making operations safe as well as painless. But his depiction of a surgeon with bloody bare hands, standing in Victorian formal street clothes, gives the most dramatic possible emphasis in the painting to the two most important scientific advances of the century. Modern medical students spend days or weeks learning the ceremonial of the five-minute scrubbing of hands with a stiff and somewhat painful brush, the elaborate robing of the high priest in a sterile gown by a nurse attendant, hands held high. The rubber gloves, the mystery of a face mask and cap. In some schools, the drill is to cover the hands of a neophyte with charcoal dust, blindfold him, and insist that he scrub off every speck of dirt that he cannot see before he is admitted to the operating theater for the first time. If he brushes some object in passing, he is banished to the scrub room to start over. So the Gross Clinic has an impact on everyone who sees the surgeon in street clothes, but it is trivial compared with the impact that painting has on every medical student who has been forced to learn the stern modern ritual. For at least fifty years, that painting hung on the wall facing the main entrance to the medical school, where every student had to pass it every day. To every graduate, the lack of clean surgical technique by the famous man was a wrenching sermon on every doctor's risk of trying his utmost to do his best, but doing the wrong thing. That painting, hanging quite high, was rather cleverly displayed to the public through a large window above the door. With clever lighting, every layman who walked along busy Walnut Street could see it, too, and it became a part of Philadelphia. That was a feature the medical community barely noticed, but it was probably the main reason for public uproar when a billionaire heiress offered the school $68 million to take the painting to Arkansas. The painting was not just an icon for the medical profession, it had become a central part of Philadelphia. Philadelphia wanted to keep that painting for a variety of reasons, and one of the main ones was probably a sense of shame that we were so poor we had to sell our family heirlooms to hill-billies. The doctors didn't pay much attention to that. They were mad, plenty mad, that a Philadelphia board of trustees would appoint a president from elsewhere who would give any consideration at all to such an impertinent offer. Fanny Kemble

Frances Anne Kemble, universally known as Fanny, was just about the most magnificent Philadelphia woman of the Nineteenth Century. She spent much of her time abroad and others claimed her, but she was ours. Coming from a famous English theater family, the niece of Mrs. Siddons and the daughter of the founder of Covent Gardens, she quickly rescued the failing family fortunes by becoming the most striking Shakespearean ingenue of the time. It took very little time for her to know Lord Byron, Thackeray, and various other luminaries of the literary and artistic world of Europe, along with Queen Victoria. One might as well say she knew everybody unless one made the point that everyone knew her.

On a theatrical grand tour of America she met and married the Philadelphian Pierce Butler, one of the richest bachelors in the nation, heir to huge estates in Georgia. She had plenty of other choices, including the most dashing and romantic devil of the century, Trelawny. That glamorous friend of Byron's had been the one to drag Percy Shelley's body from the ocean, and was surely the greatest heartthrob of the century. Toward the end of her life, Fanny demonstrated the range of her appeal by totally subjugating the intellectual novelist Henry James, who was 34 years younger than she was. Her portraits by Sully now hang in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and in the Rosenbach Museum. Although Sully was said to have glamorized her a bit, her movie star qualities are evident. But appearance alone could not have mesmerized Henry James, known in literary circles as The Master. She was evidently one of those powerfully self-assured personalities encountered from time to time, who dominates every conversation, fills every room she enters, inspiring admiration rather than jealousy. As a youth, she was enchanting, as a mature woman, magnificent. Henry James described her as having "an incomparable abundance of being." But this was not just another Cleopatra. Fanny Kemble had two personal achievements of enduring note. Because of health limitations, she went beyond being a Shakespearean actress to inventing a style of a public reading of Shakespeare, taking all the parts herself. She and Dr. Samuel Johnson were the two successive forces transforming Shakespeare's reputation from the quaint playwright of the past into the permanent towering figure of the English language. Her other achievement destroyed her private life. As the wife of the owner of a thousand slaves, she led the attack on slavery before the Civil War. During the War, her passionate defense of emancipation was the main factor in persuading the British Government to refuse badly needed loans to the Confederacy. However, the publication of her journals was the last straw in a tumultuous marriage, and Pierce Butler divorced her, taking custody of their daughters, exiling her to England. Southern plantation owners were always short of cash, and realistically one has to acknowledge the strain of demanding to emancipate a thousand slaves, each one worth a thousand dollars. In one of the supreme ironies of a tragic situation, the forced sale of the slaves compelled the Butlers to liquidate an asset just before it was going to be destroyed by wartime events. Butler died in 1863, but she had done him a financial favor. Fanny's daughter married Dr. Caspar Wistar, of Grumblethorpe and the grounds of present LaSalle College. Her grandson was Owen Wister, the college roommate of Teddy Roosevelt, later the author of The Virginian. Famous for the phrase "If you say that to me, smile", Owen Wister and his roommate created the fable of the romantic cowboy which still dominates movies and fiction, and, from time to time, the Presidency of the United States. Georgetown Oyster Eat: Separate but Equal

It's a source of some regret never to have attended the Georgetown Oyster Eat. It occurs in the middle of February when the days are dark and short, and the weather is uncertain for driving. Local citizens of Sussex County, Delaware, report no one alive remembers when or how the custom began. In the nature of such things, a certain amount of historical inaccuracy is thus to be expected. It certainly did start out as an all-male event, taking place in the firehouse. One inflexible requirement is that a participant must bring his own oyster knife, which is a very heavy chunk of iron with a short blade attached, sort of like a screwdriver. The ones I have seen are all one piece of iron, suggesting they have been hammered out in a blacksmith shop. The flattened-out blade serves as an eating utensil, as well as a wedge to pry open the oyster shell. The oysters are eaten raw and whole, often with some sort of condiment, like horseradish sauce. Some eaters favor a whole lot of ground pepper, and various other ancient remedies are said to make an appearance. The main beverage is beer, lots of beer. Beyond that, not much is known or divulged to the public, although a party attended by nearly a thousand tipsy people can't keep very many secrets. Before the party, the windows of the firehouse are covered with brown wrapping paper, sealed with tape. Kegs of oysters and kegs of beer are rolled into the firehouse before other things get rolling, and a lot of loud noises and laughter emerge almost all night. The sponsors claim to bring a thousand bushels of oysters to each party, although it is hard to imagine very many people eating their quota of a bushel apiece. The per-person beer consumption is a statistic kept confidential. The ladies of the neighborhood report numerous husbands eventually returning home, with their glasses broken, and suspicious red bruises on their faces. Aside from that, nobody knows nothing'. About ten or fifteen years ago, feminism reached the Delmarva Peninsula, and the ladies started their own brawl. Renting the Grange Hall and brown-papering the windows, they make a lot of noise come out all night. Because of some sort of oyster virus, oysters are not nearly so plentiful any more. There's a more elaborate accusation that excessive fertilizer on the farm fields runs off and stimulates a bloom of algae, which depletes the oxygen of the river and kills a lot more than oysters. Anyway, the oysters are in short supply. If the local firehouse custom dies out, it won't be from lack of enthusiasm, however. Getaway

Occasionally prisoners must be taken to the hospital, and that's a problem for the authorities. Philadelphia General Hospital had a special prison unit on its grounds, so the problem for the guards was merely to transport the prisoner to the locked hospital ward and bring him "home" after his medical problems were fixed. The State of Delaware doesn't have a prison unit in any hospital, so the security risk must be addressed by sending at least two guards, night and day, to some hospital, and securely manacle the prisoner to the bedstead. Nobody likes this situation, particularly the head nurses, but no one has a better solution to offer. When prisoners have to make an outpatient trip for an x-ray or similar, there is usually an iron rule: no one is to know about it in advance. In one particular case, however, a convicted Delaware murderer had to have an x-ray of his gallbladder, which in those days required swallowing some large pills the night before. That was the tip-off. On the specified morning, he was bundled into a patrol car with manacles and guards, and whisked off to the Delaware Hospital, now the Delaware Division of the Wilmington Medical Center. The x-ray department was at the end of a long corridor, with the diabetic clinic on the right and the bathrooms on the left side of that corridor. The entrance was on the side of this corridor, right next to the office for visiting consultants. Things were busy but peaceful that morning when a commotion arose. Three prison guards came marching through the door, surrounding their manacled prisoner. They turned left, and down the long hall to the x-ray department. As they passed the men's room, the prisoner begged his guards to let him relieve himself, so they took him into the bathroom, removing the handcuffs. He washed his hands, dried them with a paper towel, pushed it into the waste container. Then quick as a flash he thrust his hand deeper into the crumpled waste paper, got the loaded revolver his accomplices had put there, and emerged from the wastebasket -- shooting. The guards got down on the floor, a bullet went into the Diabetic Clinic were a very prominent society lady was working in a pink volunteer's uniform, and another bullet went into the consultants' office, which on other days I might have been using. The escapee was running hard, fired one final bullet into the ceiling at the door, and was out in a second to the waiting getaway car where his buddies were ready. He got away clean, as they say. There's nothing like an episode of that sort to bring people together. We were survivors of an exhilarating experience, having something in common that no one could take away. For a couple of years afterward, the bullet hole remained unobtrusively in the ceiling by the entrance. The nurses told me that workmen had arrived several times to patch it up, and the society lady, who was a trustee of the hospital, wouldn't let them fix it. That was our bullet hole. Greenwich, Where?

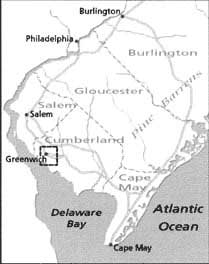

If you sail north up the Delaware Bay, you would go past Rehoboth, Lewes, Dover, New Castle, Wilmington -- on the left, or Delaware side. On the right, or New Jersey side, it's a long way from Cape May to Salem, the first town of any consequence. That is, the Jersey side of the riverbank is still comparatively uninhabited. When the first settlers came along, with vast areas to choose among, it might have seemed attractive to settle on the Delaware side, because the peninsular nature of what is now called Delmarva (Del-Mar-Va) would provide land access to two large navigable bays, the Delaware, and the Chesapeake. To go all the way up the Delaware to what is now Pennsylvania would give trading access to a whole continent, so that eventually proved to be where immigration was headed. But as a matter of fact, the marshy Jersey shore seemed more attractive for settlement by the earlier settlers. A settler has to think about starving the first year or two, because trees have to be cut down, and stumps pulled up before the land can even be plowed. After that, comes planting and growing, then finally harvesting. Trees, behind which Indians can hide, are a bad thing all around in the eyes of a settler. The flat swampy meadows of the Jersey bank were just exactly what the Dutch knew how to manage. Dam up the creeks and drain the ground, and you will soon have lots of lands ready for the plow, without any confounded trees. By the end of the seventeenth century, the English who had made the mistake of settling in rocky Connecticut finally saw what the Dutch were able to do, and came down to take it away from them.

That's why there is a Salem, New Jersey, and also a Greenwich, New Jersey. Greenwich ( around here they pronounce it green-witch) had 870 residents at the last census. It is one of the cutest little colonial villages you are likely to encounter. The local historians refer to it as an unreconstructed Williamsburg, drawing prideful attention to the fact that these houses were really built in the colonial period, and are in no way imitation reconstructions. The isolated charm of this place is in large part due to being surrounded by a maze of wandering creeks, so visitors by land travel don't get there in time for lunch unless they take great care to follow a local road map. If you arrive by water, it's no problem; just navigate up the crooked and twisting Cohansey River. Although pioneer settlement was much earlier, the oldest house still standing in that rather damp area was built in 1730. Things are pretty much the way they were before the American Revolution because the Calvinists who settled here were not prepared for the Jersey mosquito, which obviously is abundant in such a marshy area. With the mosquito comes relapsing (Vivax, malaria, black water (Falciparum) malaria, and Dengue Fever (graphically known locally as break-bone fever). As a matter of fact, encephalitis is also mosquito-borne. When you don't understand the insect carrier situation, survival in such an environment depends on local fables and lore, like going to the mountains for the summer after the planting season, and only returning at harvest time. That sounds to a New Englander newcomer like a superstitious cloak for lazy living, especially since masses of fish come up the river in teeming waves, looking for mosquitoes to eat. So, Greenwich is charming, but it never was thriving. Working hard to find something to say about the town, it would appear that Paul Revere himself came riding into Greenwich in December 1774, urging the town to join their Boston relatives in the destruction of tea belonging to the British East India Company. Greenwich accordingly had a public tea burning on December 22. Since the more notorious Boston tea party took place on December 16, 1773, and the British Tea Act was passed in May, 1773, it is not exactly accurate to say the rebellion spread like wildfire. One has to suppose that the inflammatory tale told to the local farmers by Paul Revere was likely a little enhanced, since a careful recounting of the events in Boston suggests a number of ways the uproar might have been avoided if Samuel Adams and his friends had been less provocative. Or if Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been less flighty. Or for that matter, if Benjamin Franklin had restrained himself when he got hold of Hutchinson's letters at a critical moment when he was in London. In retrospect, the best model for behavior was provided by the Royal Navy; the whole Boston Tea Party was surrounded by armed British naval vessels, who did not lift a finger throughout the demonstration. Anyway, little Greenwich had its minute of fame with a tea burning. Otherwise, it has had a very quiet existence for three centuries. REFERENCES

Health Savings AccountsThe legislation removes the hampering restrictions of the 1995 Law. What follows is a brief outline of the main features of the HSA/MSA clause in the 2003 law,