4 Volumes

HEALTH SAVINGS ACCOUNT: New Visions for Prosperity

If you read it fast, this is a one-page, five-minute, summary of Health Savings Accounts.

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Handbook for Health Savings Accounts

New volume 2015-07-07 23:31:01 description

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

SECTION FIVE: Multi-Year, the Future of HSA

Lifetime Health Savings Accounts are only a dream, to be worked on for months or years, because they invade so many turfs, and will require extensive legislation to become a reality.

It seems remarkable in retrospect it took me so long to think of extending "term" health insurance into lifetime multi-year health insurance. As the reader will notice, it rapidly expands to suggesting to some (probably astonished) life insurance companies that they take a look at the idea of doing the whole job, from investing to paying hospitals. Spreading in quite a different direction, it could expand to becoming a money machine which needs prudential restraint, even supervision by the Federal Reserve. Some of it may sound cockeyed, like putting a man on the moon, or a drone over the planet Pluto. But the reason it hasn't been tried has little to do with innovation. It relates to connecting health insurance to the place where you work. It's the employer who is reluctant to extend his involvement more than one year, because employees can be so mobile.

The required extra ingredients are pretty simple, since the central one of pouring left-over funds from one year into the succeeding year is already part of the classical Health Savings Account. The genie is out of the bottle, so to speak. It is highlighted that one-year term insurance primarily protects the insurance company, limiting its exposure to a single year. The investments are already pooled, and the many years of a lifetime can be covered by successive one-year catastrophic insurances, although lifetime catastrophic health insurance would be preferable, because it eases the "guaranteed renewable" issue. Tax exemption is already part of life insurance, but this tax exemption is sort of special. If the catastrophe to be covered is really a catastrophe, few people will experience more than one in a lifetime. But if you define a catastrophe as anything more than a thousand dollars, I'm afraid it is increasingly common.

About all the product needs is the willingness of the insurer to do it, and the willingness of government to permit it. When you do the numbers, however, you find that what then blocks it on a technical level is closing the loop, connecting the end of one life, back to the beginning of another.

This in turn is inhibited by the heavily borrowed healthcare costs of a child from birth to age 21, before he can earn a living. It's just about impossible to design a self-funded plan which begins with a $28,000 deficit.The rising costs from age 21 to 66 are quite suitable, but there just aren't enough years of compound interest to make the package viable. From where I sit, you can't have lifetime insurance unless you agree to pour funds from a different generation which has the money (and is willing to give it up or loan it) to cover that initial cost of being born. But if you concede that one point, oh, my, what a product you will have. I'm afraid that is unfortunate for poor people without a sponsor, although you will see how I do my best to work around that difficulty.

We started out with the difficulty of assembling enough money to do the job. With the notion of multi-generation involvement, we run into the reverse problem. There's if anything an excess of money-generation, mandating the addition of a limitation, which I would suggest is bringing the balance to zero after one grandchild has been funded. There should be no need for entanglement in the laws of perpetuities if the protection is built-in. I'm afraid I see no other feasible way to prefund any appreciable number of newborns, and getting over that particular hurdle is the main obstacle to lifetime health insurance. Otherwise, prolonged life expectancy would probably need to add another fifteen years to manage it.

SECTION FIVE: Multi-Year, the Future of Health Savings Accounts

.Paying for the Healthcare of Children

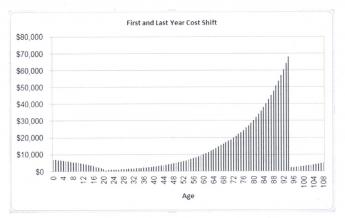

It has been said by others that eventually healthcare will shrink down to paying for the first year of life, and the last one. Right up to that final moment, medical payments must somehow evolve in two opposite directions. We might just as well imagine two complimentary payment systems immediately because the two persisting methodologies could eventually conflict unless planned for. Paying in advance is fundamentally cheaper than paying after the service is rendered because there is no potential for default in payment.

The two methods even result in different aggregate prices; in one case you pay to borrow, while in the other you get paid to loan the money. Dual systems are a fair amount of trouble; remember how long it took gasoline filling stations to adjust to credit cards versus cash. When gas prices eventually got high enough, they just charged everybody a single price, again. This isn't just lower middle-class stubbornness. Dual payment systems slow you down, and profit is generated from repeated rapid transactions. The buyer wants the goods and the seller wants the money. The profit comes from doing exchanges as fast and often as you can manage them.

In a well designed lifetime scheme, with balances successively transferred from one pidgeon-hole to another, it becomes possible to maintain a positive balance for years at a time (thereby reducing final prices, because the income from compound interest keeps rising toward its far end). That was a discovery of the ancient Greeks, but sometimes Benjamin Franklin seems like the only person to have noticed.

The last year of life is more expensive, But the first year of life may cause more financial pain.

|

However, In real-life health costs, there is one intractable exception. Because obstetrics can be costly, particularly the high costs of prematurity and congenital abnormalities, the first year of life averages $10,500, or 3% of present total health costs. It, therefore, results in pricing which many young parents cannot afford, in spite of insurance overcharges to catch up later. And thereby a multi-year stretch of interest income is jumbled up, often lost entirely. It gets worse: childhood costs from birth to age 21 average 8% of lifetime healthcare. Please notice: Single-year term insurance premiums always rise to a much higher level than a lifetime, or whole-life, premium costs, because of internal float compounds in whole-life. Modern medicine has also resulted in rising lifetime costs, with only this obstetrical exception. Someone surely would have figured this out, except excessive taxation of corporations created a motive not to notice the effect on tax exempted expenditures.

This problem obviously could be approached by borrowing or subsidizing. Someone might even envision a complicated process of transferring obstetrical costs to the grandparents for thirty-five years, then transferring the costs back to the parent generation. Since we are describing a cradle-to-grave scheme, it seems much better to imagine a single person's costs eventually becoming unified. Grandparents do in fact share continuous protoplasm with grandchildren, but before that was recognized, the courts had decided a new life begins when a baby's ears reach the sunlight. Stare decisis beats biology, almost every time. A society which already has a high divorce rate and plenty of other family upheavals probably feel better suited to the principle of "Every ship on its own bottom." -- except for this financing issue. For childless couples and parentless children, some kind of pooling is possibly more appealing, and the complexities of modern life may eventually lead that way.

|

In the meantime, lawyers, who see a great deal of human weakness, are probably better suited to suggest a methodology for transferring average birth costs between generations, and back, although a voluntary process seems more flexible. It would seem grandparents are often most likely to be in a position to leave a few thousand dollars to grandchildren in their wills, and age thirty-five to forty seems the time when competing costs are at a lifetime low, making that the best time to pay it back.

Some grandparents are destitute, however, and some parents are basketball stars. There are surely generalizations with many exceptions. The process is happily simplified by a birth rate of 2.1 children per couple, which is also 1:1 at the grandparent/grandchild level and our Society has an unspoken wish to increase the birth rate if it could afford it. For legal default purposes, matrilineal rather than patrilineal descent may be more workable. But -- if every grandparent willed an appropriate amount to some grandchild's account, it would work out (with a small balancing pool), creating a small incentive for the intermediate generation to have more children.

The answer to this dilemma probably lies in revising the estate-resolution process, making HSA-to-HSA transfers largely automatic within families, devising a common law of special exceptions and adjustments, and creating a pooling system for special cases which defy simple-minded equity. A large proportion of grandparents have an indisputable defined obligation, and a large proportion of grandchildren have an indisputable entitlement. The difficult problems reside in the exceptions and require a Court of Equity to decide them. We leave it to others to fill in the details because there could be many ways to accomplish this, and some people have strong preferences. The basics of this situation are the grandparents with surplus funds are likely to die later, but they are still likely to die, close to the age when newborns are appearing on the scene.

When you get down to it, the problem isn't hard if you want to solve it. By arranging lifetime deposits in advance, a large number of grandparents could die with an HSA surplus of appropriate size. A large number of children will be born without a standard-issue family and need the money. After the standard-issue cases have been automatically settled, these outliers can be referred to a Court of Equity charged with doing their best. After a few years of this, the results can be referred back to a Committee of Congress to revise the rules.

A basic fact stands out: most newborn children create a healthcare deficit averaging 8% of $350,000, or $29,000, by the time they reach age 21. Most young parents have difficulty funding so much, and so all lifetime schemes face failure unless something unconventional is done to help it. A dozen more or less legitimate objections can be imagined, but seem worth sacrificing to make lifetime healthcare supportable. The main alternative is to pour enormous sums into the government pool, and then redistribute them. I am uneasy about letting the government get deeply mixed into something so personal. So, speaking as a great-grandfather myself, about all that leaves as a potential source of funds, is grandpa, and even grandpas sometimes have an aversion to long hair and rock music.

SECOND FOREWORD (Whole-life Health Insurance)

This second Foreword is a summary of a radically modified proposal. It cannot be implemented without further changes in the law or at least some clarifications of the Affordable Care Act. To state the issue, it is that increasingly larger proportions of American lifetimes are not employed, and therefore are not able to take full advantage of an employer-based system. It becomes increasingly doubtful that thirty years of employment can sustain sixty years without earned income if you include childhood. Further, there is every reason to expect further migration of illness out of the employable age group. And finally, while there are signs of reasonableness, the mandatory stance of Obamacare is not greatly different from a package of mandatory "benefits" imposed on all attempts at innovation before they can be tested. If changes in the law are required before implementation, liberalization might as well be in place before innovations are proposed. No private company could proceed at arm's length without advance assurances resembling cronyism. Everything else is negotiable, but the notion of mandatory pre-approval of any modification must be softened to something less sovereign.

Sickness itself has moved into the retiree age group and will continue to migrate there. The means of payment cannot move from the employee group, so a two-step process is resorted to, with the middle-man government controlling the flow of money between age groups. If we are ever to remove middle-man costs, this feature must be removed, as well. Meanwhile, the paraphernalia of medical care, the medical schools, hospitals, and doctors, remain largely in the urban areas where employment formerly centered. So the government once more becomes a middle-man, and the system begins to resemble a virtual system, based on computer systems which do the job without actually moving. Until everyone stops moving, such duplication increases costs degrade the quality and start riots. We must move people less, and move money more. At one careless first glance, that sounds like shifting money between demographic groups, but picking winner and loser demography has repeatedly been shown to be too divisive; almost a prescription for a second Civil War. In short, we have fallen in love with a computerized virtual model, based on the faulty assumption that it is without cost. Here and there it might be tried experimentally, but it is far too early to make it mandatory. Consequently, it proves much easier to re-design the payment system, shifting money between different stages within individual lives, than to make everyone find a new doctor, just because the insurance compartment changed. It is absurd to make everyone move to Florida on his 66th birthday. Even redesigning transaction systems is not easy, but it is by far the easiest choice. Nevertheless, there is still too much friction in the various systems to make such improvements mandatory.

The best model to adopt is that of the university president who ordered a new quadrangle to be built without sidewalks. Only after the students had worn paths in the lawn along their favored routes to class, did he cover the paths with concrete sidewalks.

The issue at the moment is that money originates with employers, supporting the whole system, but their employees no longer get very sick. To reduce complaints, they are given benefits to spend which they really don't need, raising the cost of transferring the money to retirees who do need the money but are covered by Medicare. We are in danger of repeating that whole cycle with Medicare, piously calling it a single payer system, when in fact it would be a single borrower system as long as the Chinese don't collapse. Expensive sickness now centers in the retirees, but within fifty years a dozen diseases will be conquered, and we will then need the Medicare money to pay for retirement living. Constructing massive systems without that vision will just make it harder to replace them. We are, in summary, in great need of a gigantic funds transfer system, since moving the people and institutions to match the funding is preposterous. But as long as the system has two champions (Medicare and the Employer-based system) in possession of all the money, we flirt with collapses in order to force rearrangements.

All of this is divisive, indeed. For years to come, the easiest thing to move around will be money. Eventually, institutions and clients can sort themselves out for geographical unity, and probably improved efficiency. But a financing system with the money for sickness in the hands of people who aren't sick, plus a governmental, system dedicated to an age group with almost all the coming sickness but unsustainable finances -- is a wonder to behold. Therefore, we offer the Health Savings Account as having the flexibility to collect money from the young and healthy, invest it for decades, and use it for the same people when they get old. It can cross age barriers and follow illnesses, or it can remain with survivors and pay for their protracted retirement. If Medicare is modularized, it can supply the money to buy pieces as they begin to appear less desirable. It can redistribute subsidies to the poor if an agency gives it money, and it can adjust to changes in geography and science, since all it works with, is money. And it avoids redistribution politics by giving the same people, their own money.

For all these reasons, Health Savings Accounts on a lifetime or whole-life model seem the logical place to fix the broken vehicle, while we somehow keep its motor running. If successful, it will grow too big, so it should remain modular from the start. It has feelers in the insurance, finance and investment worlds. It could easily arrange branch offices for retail marketing and service. It should have networks for research and lobbying. But as long as it retains the branch concept and avoids the imperial one, it should manage to keep the doctors, patients and institutions functioning as the whole universe rearranges itself -- at its own speed. The first major step in this process would be to clear up some regulations which did not anticipate it. With Classical HSA adjusted for the interim role, the design stage can be undertaken to link the pieces of a person's health financing. Variations of lifetime Health Savings Accounts can be tried in demonstration projects, perhaps staying out of the way of the Affordable Care Act by unifying parts other than age 21 to 66, as the New Health Savings Account. And then seeing which version of lifetime HSA survives the squabbling. That isn't all. The really big picture is to absorb the pieces of Medicare, one by one, as sickness retreats from being the central cost, and the cost of retirement becomes the real threat.

Details of Lifetime Health Savings Accounts (L-HSA)

If we propose to adopt the whole-life model for Health Savings Accounts, then why don't we just add it as a new product for the companies who are already in the whole-life business? It's a good question, and most of the answer is I don't happen to own an insurance company. Somebody has to invest a pile of money to own one. You almost never hear of corporate pirates attempting a take-over, and many insurance companies make their profits on subscribers who drop their policies, although that's mostly term insurance. Come to think of it, these are mostly 19th Century organizations who sort of had the good luck to encounter windfall profits when subscribers lived longer than was necessary to break even, and then even kept living on some more. It isn't exactly the background of people who start new businesses with new ideas. Nevertheless, they do sell their products to young people, invest the premiums for many years, and eventually pay their bills to old folks, on time and cheerfully. And there would seem to be plenty of incentive. Aggregate retirement income fifty years from now will probably be many times as large as the present face value of insurance, and probably include a larger proportion of the population. They already have actuaries on their payroll who could do the math, and who yearn for the day a new product would give them a shot at being CEO. Like me, they have already had a look at the C-suite offices, and like me, compare them favorably with the Temple of Karmac.

Who will run L-HSA, once it is legal?

|

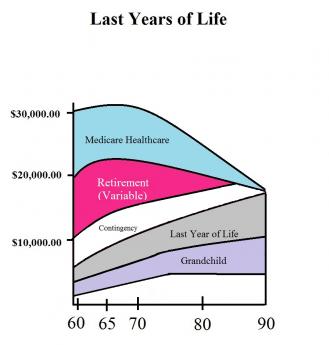

As a final feature, Catastrophic high-deductible is here added, providing stop-loss protection. Call it re-insurance if you prefer. It's single-purpose coverage, based on the idea that the higher the deductible, the lower the premium. So it follows that the longer you are a customer, the more catastrophic insurance you can afford. Cost saving runs through all multi-year ideas, but lifetime coverage is a cost-saving whopper, because of the way Aristotle discovered compound interest turns up at the far end. (By the way, that's why I suspect we have rules against perpetuities of inheritance.) It transforms Health Savings Accounts into a transfer vehicle for funds, from one end of life to the other, and must add debit-card health insurance for current expenses. Forward from the surplus of the present. And backward from the compound interest of the future. The last-year-of life could be chosen as an example because the last year comes to 100% of us, and is usually the most expensive year in healthcare, not greatly different from the face value of life insurance. But needs differ, and a ton of money sounds pretty good at any age. A Health Savings Account can also be used as a substitute for day to day health insurance. Another synonym might be Whole-life Health Insurance, although multi-year health insurance is probably more precise. The idea behind presenting this concept piecemeal is to provide flexibility for both overfunding and underfunding, since the time periods for coverage can be so long (and the transitions so variable) that both eventualities would occur simultaneously to different individuals.

The simple idea is to generate compound investment income -- not presently being collected -- on currently unconsumed health insurance premiums. And eventually, to apply the profit to reducing the same individual's future premiums. Even I was then startled, to realize how much money it could save. It's a scaled-up version of what whole-life life insurance does for death benefits. Since lessened premiums generate greater investment income, the math is complicated even when the theory is simple, but every whole-life insurer has experience with smoothing it out. For example, if someone had deposited $20 in an HSA total market Index fund ninety years ago, it would now be worth $10,000, roughly the average present healthcare cost of the last year of life. Neither HSAs nor Index funds existed ninety years ago, and of course, we cannot predict medical costs ninety years from now. This is only an example of the power of the concept, which we can be pretty certain would save a great deal of money, but skirts the guarantees about just how much.

There's one other advantage to using HSAs within the whole-life insurance model. It has always bothered me that life insurance tends to gravitate toward bond investments, matching fixed-income revenue with fixed-outgo expenses. But insurance companies largely support the bond market, which is many times as large as the stock market. In effect, their situation encourages them to increase the amount of leverage in the economic system, thereby increasing its volatility, and its tendency to experience black swans.

Furthermore, the insurance industry has accumulated a great many special tax preferences, based on the notion its social value is a good one. Placing life insurance in competition with non-insurance providers of the same services would justify extending the tax preferences to the others as well. The resulting competition would invigorate what has become a pretty stolid plodding citizen, with somewhat unique power over state legislatures. State legislatures, in turn, would benefit from increased competitive points of view among their lobbyists.

People would be expected to join at different ages, so the ones who join at birth in a given year have accumulated funds which would be matched by late-comers. In our example, if a person waited until age twenty (and most people would wait at least that long), he would need to deposit $78 -- not $20 -- to reach $10,000 at age 90. It's still within the means of almost anyone, but the train is pulling out of the station. Participation is voluntary, but no one saves any money by delaying and learns a bitter lesson when he tries. Notice, however, no one pays extra for a pre-existing condition, either; it costs more to wait, but it does not cost more to get sick while you wait. If the government wants to pay a subsidy to someone, let the government do it. But nothing about the whole-life retirement system compels increased premiums for bad health or justifies lower premiums for good health.

Whole-life health insurance takes advantage of the quirk that the biggest medical costs arise as people get older, and similarly, health insurance premiums are collected early in life when there is considerably less spending on health. The essence of this system is to reform the "pay as you go" flaw present in almost all health insurance. Like most Ponzi schemes, the new joiners do not pay for themselves, they pay for the costs of still-earlier subscribers, a system that will only work if the population grows steadily and/or prices rise. When the baby boomers bulge a generation, they bankrupt the system, but only when they themselves start to collect. Everybody knows that. What is less generally known is that "pay as you go" systems fail to collect interest on idle premium money; the HSA system does that, and it turns out to be a huge saving unless the Industrial Revolution stops. Medicare and similar systems don't collect interest during the many-year time gap between earlier premiums and later rendered service; potential compound interest is therefore lost because payroll deductions are used for other purposes. "Pay as you go" is only half of a cycle; adding a Health Savings Account converts it into a full cycle like whole life insurance, and furthermore returns the savings to the individual, rather than using them for insurance company purposes. Whole-life life insurance is more than a century old, but health insurance somehow got started without half of it, the half which could lower the premiums. Nobody stole those savings, they just weren't part of the gift.

All this creates an incentive to overfund the Health Savings Account. The surplus which remains after death is a contingency fund, probably useful for estate taxes or other purposes; but on the other hand, the uncertainty of estate taxes creates an incentive not to overfund by much. Most people would watch this pretty carefully, and soon recognize the most advantageous approach of all would be to pay a lump sum at the beginning, at birth if possible. Before someone roars in outrage about the uninsured, let me say this would work for poor people with a subsidy, and it begins to look as though the Affordable Care Act won't work unless it is subsidized. In that case, a downward adjustment doesn't reduce premiums, it reduces the subsidy.

Investment It seems best to confine the investments of a nation-wide scheme to index funds of a weighted average of the stocks of all U.S. companies above a certain size, and thus offering to pool for those who are (rightly) afraid of investing. This will disappoint the brokerage industry and the financial advisors, but it certainly is diversified, fluctuates with the United States economy, and has low management costs. In a sense, the individual gets a share in nation-wide whole-life health insurance which substitutes long-run equities for conventional fixed income securities. It removes the temptation to speculate on what is certain to occur, but on dates which are uncertain. Treasury bonds might be added to the mix, but almost anything else is too politically vulnerable to political temptations. Even so, it will have downs as well as ups, and therefore participation must be voluntary to protect the index manager from political uproar when stocks go down, as from time to time they certainly will.

One danger seems almost certainly predictable. This book has chosen 6.5 percent assumed return, mostly because it happens to make examples easy to calculate. The actually required return is probably closer to 4% plus inflation. Supposing for example that 7 % is the right number, there is little doubt a steady investment return is only achieved on an average of constant volatility, sometimes returning 20% in some years, and sometimes declining as much or more in other years. Judging from past experience, there will be a temptation for some people to make withdrawals in years of bull markets, which could reduce average returns to 3 or 4 percent in bear market years, and fall short of the 7% average at the moment it is needed. In addition, the officers of Medicare are likely to be tempted to pay Medicare more than a 7% average in windfall years, leaving the running annual average to decline below 7%, just as the trust officers of pension funds once deluded themselves by temporary runs of bull markets. Ultimately this issue reduces itself to a question whether a temporary surplus is really temporary, and if not, whether the subscribers should benefit, or the insurance company. After that is decided, extending or contracting the accordion would get consideration. It seems much better to negotiate these philosophical questions of equity in advance, and establish firm rules before sharp temporary fluctuations are upon us.

Ensuring the Uninsured. Because universal coverage has great appeal, I have gone through the exercise of calculating whether the impoverished uninsured might be included by using subsidy money to provide a lump sum advance premium on their behalf. It would work, in the sense, it would be less costly, but I do not recommend beginning by including it. Reliable government sources have calculated that even after full implementation, the Affordable Care Act will leave 31 million people uninsured. That is, there are 11 million undocumented aliens, 7 million people in jail, and about 8 million people so mentally retarded or impaired, that it is unrealistic ever to expect them to be self-supporting. In my opinion, it is better to design four or five targeted special programs for these people and keep their vicissitudes out of conventional insurance. Better, that is, than to include them in any universal scheme which the mind of man can devise. But to repeat, the mathematics are adequate to justify the opinion that it would save money to include them in this plan with a front-end subsidy of about five thousand dollars, adjusted backward for fund growth since birth. I refuse to quibble about investment size since no one can be certain what either investments or medical science will do in the future. It seems much better to make annual recalculations for inflation and medical discoveries, and then make adjustments through an accordion approach for coverage. There seems to be no need to make precise predictions since any benefit at all is an improvement over relying on taxpayer subsidies, which now run 50% for Medicare itself. This plan will help somewhat, no matter what the future brings, and as far as I can see, it would make the presently unmanageable financial difficulties, more manageable.

George Ross Fisher, M.D.

Converting Term Health Insurance Into Lifetime Health Insurance

We start with the lucky circumstance that everyone has belonged to Medicare for half a century, and before that, large populations had Blue Cross and Blue Shield. The cost of healthcare at various ages is pretty well known for large populations. Since lifetime life insurance is cheaper than term life insurance, it is safe to assume lifetime health design is cheaper than year-to-year health insurance. The present inflexibility is one of the relics of an insurance system based on employer gifts to employees who are no longer as sickly as they once were. To go further, it also seems pretty safe to convert from a more expensive system to a cheaper one, and expect profits, except for the quirks of the tax laws. At the least, marketing costs should be reduced, the provision would no longer be needed for gallbladder and cataract removals in people who have already had the surgery, and interest could be earned on unused premiums over long periods -- if we could unify around patient insurance rather than yearly renewals based on place of employment. The system would become vastly more efficient, and interstate transfers would be facilitated. The methods employed by ERISA would be a good model for a start, and its experience would be useful.

Accounting theory has it, every cost must be attached to a charge. So charges inflate to accommodate them.

|

| What Costs So Much? |

This book's present proposal is to do roughly the same thing, converting term health insurance into lifetime health insurance, year by year. After all, that would start from a 15-million subscriber base. That's just the basic revenue source, however. Health insurance has a number of jumbled issues during a long transition period. The purpose of stressing the life insurance model first is to overcome a natural suspicion that we intend to claim magical powers of predicting the future. That risk is assumed to be stipulated, and we will not bore you with constantly repeating it.

Let's start at the far end, with the final answer to the test. In the year 2000 dollars, the average American spends an average of $325,000 on health care in a lifetime. Women spend about 10% more than men. The main problem is to take a lump of money at the end and restore it to different young people as they get sick. When they remain well, the problem of balance transfers is fairly simple. To ensure the entire lives of 340 million Americans, the cost would be trillions of dollars. That's 110,500 trillion, in fact, give or take a few trillion. Or 110 of whatever is one thousand times bigger than a trillion. The original mind-boggling figures were developed by Michigan Blue Cross from its own data and confirmed by several federal agencies; the future projections are my own. By the end of this book, we will have suggested it should be possible -- to cut that figure in half, without changing the medical part of it very much.

It is legitimate to be skeptical since a ninety-year lifetime history involves a great many diseases we don't see any more. They afflicted many people who would have been readily cured with present medications except the drugs weren't invented. As if that weren't complex enough, it also involves predictions about the health costs of people who are still alive, destined to be treated with drugs nobody has seen, yet. To hammer this last point home, it is roughly estimated that fifty percent of drugs now in use, was not available only seven years ago. Since we must go back ninety years to get data about the childhood illnesses of our presently oldest citizens, the unreliability of also looking ninety years forward from 2015 must be clear. And to do that for a population constantly in the transition from very young to very old is daunting, indeed. But the facts of life, that people are born, go to school, get jobs, get sick, and then die -- never change. What's new, is it takes longer to run the course, and thus opens up gaps between steps. If we gather the gaps and meanwhile charge premiums on the longer time intervals, we produce a brand new source of revenue. While the intricacies sound complicated, in the end, we rely on going from a more expensive process to a cheaper one, assuming the transition costs can be supported.

The value of attempting it is considerable. We already have a technique which the statistical community agrees is reasonable, which tells us lifetime insurance would require something over $350,000 per person. Future trends can be estimated well enough, to show whether costs-after-inflation are going up or down, and roughly by how much. A penny in 1913 money is called a dollar today, just for illustration. Naturally, we then assume a dollar today will be called 100 dollars, a century from now. Regardless of numbers games with the value of a dollar, we have a tool to estimate the general magnitude of health costs, and by how much they will likely change. It's useful, even when its answers are surprising.

Theoretically, there is room for a change in expectations. Some people may decide living eighty years is long enough, and then decline to pay for more. However, I've tried it, and I don't feel eighty is enough. So, for my own benefit if for no better reason, I decided to see what could be done with the cost problem. One solution is to work longer than retiring at age 65. If future medical care changes direction drastically, its payment system might also be forced to change. But if health care doesn't change much, the payment system won't need to predict the future. That reasoning reflects the insurance industry's own history, where the marketing department eventually asserts dominance over the actuaries, by declaring it is more important to predict generally, than with precision.

The approach has its limits. Health insurance did historically underestimate how much the payment system could warp the medical one over long periods, primarily because it initially misapprehended who its customers were. Payment methodology is now relentless in persuading its true customers, who are businessmen in the Human Relations departments of large corporations. They don't like to hear it phrased that way, but we now have a four-party system, not just a third party insurance, and its fourth-party directors, big employers. As corporate taxes rose, the system invented by Henry Kaiser in 1944 used corporate tax deductions to fund the third-party system with 60-cent dollars. In fairness to Mr. Kaiser, much of the system has migrated to take advantage of the tax deduction, and the tax rates themselves are higher.

Looking back over an expedient system designed for short-term goals, a shocking realization now begins to dawn: most current "reform" thinking is about how to twist the medical system to fit some unrelated budget. Even more shocking is the business customers discovered how modified tax laws could let them buy health insurance with a discounted business dollar. When donated to employees, another 15 or 20 cents could be clipped off. Obviously, if health insurance is subsidized by business tax deductions, and Medicare is 50% subsidized directly by tax infusion, health reform can't claim to be a reform until finance is fixed. Essentially, the employer-based system amounts to this: by giving health insurance instead of salary, the employer skips paying for extraneous things which have been linked to the salary level. Union domination of state legislatures has assisted this goal. Just, for example, the Philadelphia wage tax is based on 4% of wages, the New Jersey income tax is based on wages, and so on. If you can find a way to pay the same, but claim the pay packet is smaller, you've got the idea.

Gradually we reach the point of rebellion; if it is legitimate for insurance executives to tell physicians how to practice medicine, it must, of course, be equally legitimate for physicians to re-design the payment system. So let's have a go at it.

Footnote: In the thirty years since I wrote The Hospital That Ate Chicago about medical costs, the newspapers report physician reimbursement has progressively diminished from 19%, to 7% of total "healthcare" costs, so perhaps now it's legitimate for some related professions to answer a few cost questions, too.As patient readers will gradually see, considerable extra money is already in the financial system, leaving difficult problems of how to get it out and spread it around. This isn't snake oil or a mirage. The beneficiaries would scarcely see any difference in medical care if Health Savings Accounts fulfilled their promise. But frankly, the insurance providers would have to make some wrenching changes. Since millions make their living from sticking with the present, it is undoubtedly harder to design a new system which would please them. We're not going to mention it further in this book, but the easiest way to remove a big business from the equation would be to eliminate the corporate income tax and shift the tax to individual stockholders. It is not corporate revenue which finances the medical system, it is corporate tax deduction, largely because we have imposed a system of double taxation of corporate profits. Eliminate one of the taxes, and business might complain less about losing the tax deduction. Meanwhile, health insurers would have a new line of work offered to them. Corporate officers should, and often do, regard themselves as custodians of the capital in use, which in fact belongs to the shareholders.

What about the public? Well, medical care now costs 18% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 18% is pretty surely crowding out other things the public might prefer to buy. In a sense, the political beauty of the premium-investment proposal we are about to unfold lies in its primary aim of cutting net costs by only adding new revenue. Critics will say we pretend to lower costs by raising them. But essentially the money is spent to eliminate hidden subsidies and red tape which are off the books, and by other means which have been overlooked in the past. The accounting theory is that every cost must be attached to a charge, so charges have been inflated to accommodate that notion.

Some Underlying Principles

Casualty insurance formerly contained a clause making it noncancellable and guaranteed renewable. Except for disability insurance, most insurance no longer has those contractual promises, but the better ones will still "stand by their product". Prices were too unstable to permit a continuation at the same price as a legally enforceable right. In 1945, the Henry Kaiser caper changed the whole nature of the relationship, at the end of which the employees walked away with no individual renewal right at all, but got really great benefits while they had them. That was not a good bargain. Without a right of renewal, there is no good way to make internal transfers from young healthy employees to aging sick ones. Apparently, labor and management felt it was more important to get something out of the situation than to come away empty-handed. Most of these negotiations were private, and there may have been unrevealed considerations.

No individual renewal right, but really great benefits while they lasted.

|

| Bad Bargain. |

But the one sure outcome of this turmoil was a young employee had no assurance of health insurance if he changed jobs, and no sure way of transferring surplus benefits to his later years, even after remaining within the same employer group for decades. Older employees were plainly getting more value for their health benefit, but young ones could not be sure they would stay around long enough to enjoy it. In retrospect, this may have been a driving force in the enactment of Medicare in 1965. Employees experienced "job lock", which definitely meant they could not take stored-up benefits to a new employer, or into retirement. Furthermore, casualty health insurance was gradually changed by employers donating the policy to the purchaser, so ownership of the policy migrated into the employer's hands. The employer had to change insurance companies for the whole employee group, or not at all, so slavery begat more slavery. The negotiated group rates naturally reflected this change. The business plan of health insurance does not differ greatly from automobile insurance: Premiums are paid to an insurer at the beginning of the year; and at some time during that or subsequent years, the insurer uses the pooled money to pay the claims. In practice, there does exist one important difference between the two types of casualty insurance. Many auto insurance companies imply they hope to renew a policy if the premiums remain paid, but hardly any health insurance is "guaranteed renewable" in any sense. You can pay individual health insurance premiums for many years to the same insurer, but the insurer still reserves the right to drop you.

This largely unanticipated disadvantage grows out of the sponsorship of health insurance by employers since applicant employees are in no position to put strings on a gift. Its hidden unpleasantness was emphasized when millions of people were recently dropped from long-standing policies which did not conform to the Affordable Care Act's regulations. Original motives and understandings became unprovable after the passage of time. One could, however, easily imagine employers felt they might acquire new duties by law, and were reluctant to stand behind unmeasurable ones. One could imagine the insurers were uncomfortable with the risk an employee might move to a new state, and because of the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution, be facing insurers with no duty to continue coverage. This ACA dilemma came about in an environment with so little competition, neither the employers nor the health insurer felt compelled to wander into unforeseeable conjectures.

In this single subsequent event during the Obamacare confusion, a serious disadvantage of employer-based insurance discarded its tradition as harmless boiler-plate, revealing the enforceable facts of the matter. A health insurance company can unexpectedly walk away from an employer-based contract, even when it is needed most. The patient gets it as a gift and doesn't own it. This dispute over fairness and the original intent was surely involved in the government's decision to delay implementation of Obamacare for large employer groups.By contrast, we must point out the Health Savings Account leaves unspent money with the individual as permanently as he can restrain himself from spending it. For this, he loses the ability to pool with others and must buy high-deductible insurance to provide the pooling feature for large costs. Interest gathered on his idle money remains his alone. By retaining ownership in the hands of the employee, HSA gains protections against much broader health-finance risks, than the Affordable Care Act's pre-existing condition-exclusion does, for its population segment.

In fact, this sweeping violation of a gentleman's agreement may make such arrangements unacceptable in the future. If the employer community finds it impossible to live with guaranteed renewability, they may feel forced to drop the fringe benefit. Not everyone wants to exchange the freedom of choice for freedom from the expense of it, but some do. Consequently, opening this can of worms could lead to the dissolution of the present system, which depends heavily on the tax-deductibility of the gift for employers. There is essentially no difference between an individual income tax, and a corporate income tax, except the corporate tax, is higher. The world's highest corporate tax necessarily creates the world's highest tax deductions for employers. Reduce their wage costs, and you will reduce their income tax. But reduce your own tax, and you reduce what it has been paying for. That's the bargain, and no stalling will change it.

We must, however, introduce an observation which applies to all defined-contribution plans. The advantage has switched from the older "new hire" rather markedly toward the younger "new hire", because of the addition of investment income for the younger one. This is an advantage for one, not a disadvantage for the other, but negotiators seldom recognize such arguments. The terms of the agreement should probably be adjusted for this new development, which is illustrated in the first section of this book. But since the change is due to the mathematics rather than the judgment of the donor, experts will have to see what they can do about it, before it becomes a punching bag, desired by no one, but forced on everyone.

Some rude things it would not hurt to know.

|

As long as the (term insurance) risk of losing the premium flow remained, it was not prudent to invest the money in higher-paying assets, so the insurance intermediary was in no position to maximize float. Curiously, the famous Warren Buffett became one of the richest men on earth by buying entire auto insurance companies to transform the one-year "premium float" into a virtually permanent source of cash flow. Substituting health insurance for auto policies, essentially the same strategy is proposed by this book, for employees to consider. Except for Jimmy Hoffa, few unions have considered such a role, and in view of colorful union history, perhaps employers resist it.

Is there enough money in this approach? Some of the limitations to be encountered in paying for healthcare are specific and final; longevity would be one of them. At present, the average longevity at birth is 83. It would take some dramatic research discovery to extend it much beyond 93, but it is reasonably safe to project it will slowly rise from 83 to 93 during the next century. The medical costs of achieving such a goal are almost impossible to know in advance, but attempts are regularly made, and the best available estimate is $350,000 on average per lifetime, using the year 2000 dollars. Women cost about 10% more than men, partly because of increased longevity, partly because of the statistical convention of attributing all obstetrical costs to the mother. There is a reason to believe all late-developing diseases originate in the dozen genes residual in the mitochondria of the mother's cells, so the conquest of diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and arteriosclerosis -- during the next century -- is a reasonable prediction. Furthermore, new cures while generally expensive at first, eventually become cheap. Mix it all together, and while the costs of the next century may at times be towering, it seems entirely conceivable healthcare costs will become comfortably sustainable, a century from now. If we can generate the means to get to that point, give some of the credit to Warren Buffett, and John Bogle.

John Bogle may not have invented the idea you can't beat the index, but he certainly evangelized the news that 80% of mutual funds managed by experts, somehow don't beat the index. Let's explain. When you finally get over the idea of getting rich by out-performing the stock market, the idea reverses itself. The whole stock market is a proxy for the economy, and so although some people do get rich faster than the stock market grows, hardly anybody gets richer in the stock market without using some form of leverage, a genuinely risky approach. Professor Roger Ibbotson of Yale has compiled extensive data for the previous century, and convincingly demonstrated how relentlessly the American equity stock market has grown quite linearly, depending on the asset class, but largely disregarding stock market crashes, and numerous wars, large or small. While small stocks have grown at a rate of 12.7%, blue-chip stocks have consistently grown at about 11%. With big cheap computers, we can see investors in stocks have received a return of 8%, paying a penalty for the small investor's inability to ride out really long-term volatility in any way but buy and hold. Perhaps, over time, we can find ways to narrow the overhead and return more than 8%. But for the time being one must be satisfied with 8% net, although 11% might become some ultimate goal. To go on, the 8% we get is made up of 3% inflation, so we better not count on more than 5% actual return. What will that achieve toward paying an average lifetime cost of $350,000?

The table plots how $400 will grow, starting at birth and ending at 83 and 93 years, with 5% compound interest. We've already described why 83, 93, and 5% were chosen, but why $400? It's a personal guess. It represents the amount I think would be achievable as a subsidy to "prime the pump". It might someday be a government subsidy for handicapped people who could never support themselves. And since it would be at birth, it would have to seem bearable to young parents. Many readers would react that $400 is too stingy, but politics is politics, and what people can afford is not the same as what they will vote to afford. In any event, we here are testing the math as a preliminary to announcing we can save a bundle of money by changing the system we are used to. Choose your own number, remembering we are attempting to reduce what is now reliably estimated as 18% of the Gross Domestic Product, and competing with a presidential proposal to give it to everyone. Further, the only thing you need to know about dynamic scoring is that making it free will assuredly escalate its eventual true cost.

Compound interest always surprises people with its power, and in this example, 5% just about makes the goal. There's not much room for error or contingencies. All of the known factors are conservatively estimated, and it passes the test. What isn't covered is the unknown factor, atom wars, a stock market collapse, an invasion from Mars. To be on the safe side, we had better not count on this approach to pay for all of the health care. Just a big chunk, like 25%, seems entirely feasible. In the immediately following section, we examine the first "technical" problem. The first year of life is effective as unaffordable as the last year of life, and newborns generally can't dip into savings.

First Year-of Life and Last Year, Combined

The most casual reader must have noticed compound interest curves make these lines crawl along the bottom for young people, but widen greatly for older ones. The consequence is the money is to be found in the old ones, who incidentally have less time left to spend it. Therefore, strategies must be devised to transfer money or credit from grandparents to their newborn grandchild. It is violently in conflict with our economic structure to suggest the government become a competitor in the private sector, so why not go along with our culture, and make the transfers by inheritance? It's an ancient problem, and the Society has finally decided the limit of perpetual transfer is one lifetime, plus 21 years. That's plenty of leeways to solve this healthcare issue, without either creating new rules for an aristocracy or allowing the umpire to play in the game.

|

Each woman now has 2.1 children in America, so it works out that each grandparent has one. Each grandparent also has four grandchildren, because of marriages, and with his wife, they have eight grandchildren to favor. Beyond that, the courts can figure out what to do with outsiders. The grandparent has just been shown to have money to burn if we recirculate it among generations, always stopping at one lifetime plus 21 years. It's easy to see that some grandparents and grandchildren cannot stand the sight of each other, but that is not for this book to worry about. The essence of this scheme is to transfer less than a thousand dollars between generations, somehow staying within existing laws and conventions. One transfer would be about $400, as a contingency fund to generate ample excess to smooth out faulty planning, especially the first time around.

Eventually, the plan is to transfer $25,000, to pay for the first 25 years of the grandchild's healthcare. That comes from the surplus generated at the death of the grandparent, which in turn is generated by compound interest gathered from invested withholding taxes of the grandparent, which the grandparent supplied by being employed. The extra money in circulation is gathered by his Health Savings Account, invested in the whole national economy by way of total market index funds. In a sense, the whole nation becomes an investor in the whole economy. Just as the idea of affordable housing had unexpected consequences, this also would need to be carefully studied, even pilot studied, before final implementation. The function of this book is to point out this source of revenue exists and has not been fully exploited.

Escrow Accounts for Future Needs.

One of the important advantages of Health Savings Accounts over historical health insurance lies in the contrasting sacrifices you must make if you can't afford everything. Traditional health insurance ("first dollar coverage") paid for the small things, but if you ran out of money, you had to sacrifice some big things. The Health Savings approach is to provide money for the big things first and sacrifice little things if you must. That's the essential philosophy, and it has become exaggerated by increased longevity. We need to add a simple way to by-pass small expenses and save money for later. That's the reasoning behind adding escrow accounts to high-deductible insurance.

Think about it: when a subscriber faces a medical expense costing more than his account balance, he has three choices. He could forego the medical service, he could pay cash out of pocket, or he could borrow the money. Sometimes he will have enough money in the account, but saves it for some later purpose; in that case, he might be both a borrower and an investor at the same time. When it comes time to pay off his loans, that obligation should have a higher priority than investing new money, since otherwise, the subscriber is investing on margin. Margin investing is generally a bad idea, but it can be made less risky through using an escrow account. That's a designated-purpose account, which is more difficult to invade. So, he may divide his account into three escrow accounts, and the managers may decide they need even more. It becomes inflexible if it can never be invaded, but it shouldn't be easy and paying cash or tax-unsheltered money is always better if you can.

Borrowing Escrow. It's wise to pay off debts early, so the program should require its permission to do anything else with a new deposit. Not all managers of HSA will advance overdrafts, but some will, probably at rather high-interest rates. More commonly other subscribers will have surplus money they would like to lend like a credit union, because deposits up to their annual limit are tax deductible, and they would be reluctant to pay the taxes to redeem them.

If you will need it later, Set it Aside, Now.

|

| Escrow Subaccounts |

It's possible to imagine gaming such arrangements of differing tax liability, so Congress must decide what circumstances permit it. With insurance, considerable pooling of resources happens without tax consequences, but when bank accounts are individually owned, pooling is not allowed without legal provision. Depositing unencumbered money in the escrow account is the same as investing it, except its presence indicates availability for loans in certain circumstances. Nevertheless, it is inevitable that gaps between the two curves, revenue, and expense, will develop, even though the hills eventually exceed the valleys.

My suggestion is to limit structural borrowing at low-interest rates to smoothing out the valleys characteristic of entire age levels, rather than provide individual banking arrangements between subscribers. Over time, these variations will standardize. And since the accounts will collectively grow, the quirks will eventually stabilize the investment accounts, possibly even augmenting income. However, if a surplus or deficit is exhausted, it should not be perpetuated with outside financing. The accounts operate under the principle that they come out right at the end. It, therefore, ought to be possible to adjust age-determined structural imbalances in bulk, while attempts by subscribers to game such variations should be countered by modifying interest rates.Wholesale buyouts have their advantages, but piecemeal buy-outs are better.

Proposal 5: Congress is urged to permit pooling (at low interest) between the accounts of an age group inconsistent surplus, -- and other age groups in consistently deficit status,-- occasioned by persistent divergences between revenue and medical withdrawals at differing ages. If there are other imbalances created by differential depositing, they should be corrected by adjusting internal interest rates. (2735)Medicare Escrow. There are a number of reasons why some people would want to buy their way out of Medicare, whereas others would become terrified at any mention of changes in their Medicare plan. The incentive for the government to permit Medicare buy-outs would lie in ridding itself of its deficit financing, with secondary borrowing from foreign nations. And the advantage for the plan itself is providing a cushion for a transition to lifetime accounts, ultimately a better cushion for revenue misjudgments.

By noting the average annual cost of Medicare, the number of Medicare beneficiaries, and the average longevity of subscribers, the average lifetime Medicare costs of Medicare can be calculated. Assuming inflation to affect both revenue and healthcare expenses equally, inflation is ignored. Then, with various compound investment assumptions, a range of future income can be estimated. All of this can be estimated as requiring a lump-sum payment of $60,000 at the 65th birthday in order to make a fair exchange for the Medicare entitlement and guessed at $80,000 if accrued debts are serviced. However, the individual would have paid about half of that with previous payroll deductions during his working life (a quarter of the total), and by buying out of it at age 65, would be relieved of Medicare premiums which amount to another half of what is left, or a quarter of the total cost. However, that complexity of description eventually leaves half of the total to be made up by Federal subsidy from the taxpayers because loans must be repaid. It's complicated because every revenue source available has been tapped.

The biggest issue is a foreign debt to be paid back for financing Medicare deficits in past years. Consequently, in order to put a stop to further borrowing, the buyout price must be raised. Obviously, if a past debt is serviced, more contribution is needed. Unfortunately, information about prior indebtedness is not readily available, so the entirety is here guessed to require a single-payment premium of $80,000 at the 65th birthday, for a full Medicare buyout. If the entire Medicare program, past and present, is to be paid off, they're very likely will have to be a tradeoff between increased revenue from HSA deposits and diminished service of foreign debts. As a guess, the elasticity of HSA revenue of $3350 per year, from age 26 to 66, has already more than reached its limit. For the moment, we have accepted the present Congressional limit, which was presumably rather arbitrary. While it is possible to imagine this arbitrary limit could be made to stretch to cover lifetime health costs, more likely it will only cover a portion. But to cover the Medicare unfunded debts of half the past century in addition to current costs, will require some new concept, as yet undevised, and a good deal more information than is presently public.

"All-other" Escrow. It is difficult to foresee which escrows will prove so popular they will require limits, and which others will be so unattractive they will require minimums. Moreover, it can be anticipated some people will wish to use account surplus as an estate-planning tool, while others will have no estate. A provision in law directing the uses of account surplus at death may thus appeal to the majority of subscribers, but actually may be highly unsuitable for the majority. Therefore, while it seems harmless to provide a vehicle for such individualization, too much should not be expected of it.

To most readers, these sums will seem prodigious, and indeed they are. Few people at present are in a position to consider them. We can pray for some relief from scientists, from the economy, and from demographics, because downsizing Medicare is a growing requirement, provoking even more drastic remedies if we sweep it under the rug. We need, first, to make Medicare more modular so it can be downsized in pieces, instead of all-or-none. In time, we need to downsize it and use the pieces to fund protracted retirement costs. The long-term goal, for the scientists, the politicians, and the patients, is to make it unnecessary to spend so much money on health. Beyond that, the funding of retirement has no logical limit. This long-term vision of our future must first become commonplace in our culture so we will seize every chance opportunity to advance it in fact.

Transitions To Donated HSAs, for Children

Let's proceed on the assumption Congress will authorize intergenerational transfers between HSA accounts, to the extent it becomes possible to create single payment accounts of the kind we have described. Presumably, most of these will be authorized in wills, but some donors may prefer to be alive when a transfer happens. It may happen at the birth of the child, or in anticipation of it; but accidents happen, so contingency plans should be allowed, with a default of some sort if this point has been neglected. If Congress authorizes these transactions, Congress should retain some control of them.

On the other hand, the child's parents retain fall-back responsibility too and have a right to be represented in any changes. Congress should authorize a system of transition oversight, which includes state representation, and representation of parents, as well as experts with experience in related fields, like single-deposit annuities. The transition oversight committee (or court) should have a right to suggest technical and substantive amendments to the enabling legislation, have a right to hear appeals, and the right to obtain expert advice, and such other relevant duties as the enabling body may delegate.

Someone must be placed in charge of oversight over the amount of a single payment to start these accounts, adjust necessary supplements, and to adjust for any surplus. There must be an accounting system and a public report of it. Experts in single-deposit annuities should be consulted, and future projections should be kept current. Since each year of life from birth to 21 years will eventually establish a "normal" budget, records should be maintained for the purpose of increasing or decreasing each year's average revenue assignment out of an overall children's budget. The purpose is estimating whether the overall budget needs adjustment, or whether only individual years do.

The presumption should be, the actual experience will be a near-zero balance at the 21st birthday. The possibility of surplus or deficit must be envisioned, however, and supplementation of the fund is preferred. However, if supplementation is not forthcoming, all payouts should be proportionally reduced to maintain a balanced budget. Supplements should then be sought from the parents of covered children, assuming such deficits cannot be maintained by transfers from funds intended for later ages of the recipients. It is not intended for fund sources for children born earlier or later to supplement deficits of other programs, although enough surplus should be generated to make lifetime funding possible. It should be recognized this is a sensitive point in the cycle, sometimes necessary as a break, sometimes useful as a reserve. To use the surplus to fund food stamps or agricultural subsidies is the beginning of the end.

The general principle should apply that a reimbursement agency should not be responsible for costs which were unknown before the revenue became fixed. In fairness, a new drug, instrument or procedure should not be reimbursed unless the next annual budget anticipated its existence. However, this accommodation should be reasonable, devoting more attention to the date of the annual opportunity to readjust the budget, than to political issues.

Here's the Deal

So that's what I have to offer on Lifetime Health Savings Accounts. It's about as far as a physician ought to go in meddling in related professions. It looks to me as though creating lifetime accounts on a model of whole-life life insurance would be a great improvement over our present term insurance model. But I am quite uncertain whether a project this large should be monolithic or have competition between an organization with experience, like an existing life insurance company, an evolved version of one of our health insurance companies, or an entirely new organization formed for the purpose. This topic alone is worth debate and a white paper. Several existing professions are involved and may have special legal obstacles, just as they would have special qualifications. Perhaps several demonstration projects should be launched to find out some answers before we get into a century-long, horrendously expensive, failure.

On the other hand, it would appear the financial savings would be too big to ignore. Because it would take ninety years to conduct a full experiment, it would appear fairly clear we ought to test this in component pieces and then figure out how to unify them. If we must make mistakes, let them be fairly early, drop them, and re-direct our efforts. By all means, ask the life insurance companies what their experiences were. How did they overcome the long testing period? What are the problems which term-insurance companies uncovered in their efforts?

In sum, we ought to spend a year debating the issue, several years testing likely solutions, and another year debating what we have learned. Only by following some such path, is there a chance we will end up with something we are proud of.

10 Blogs

SECTION FIVE: Multi-Year, the Future of Health Savings Accounts

Paying for the Healthcare of Children

New blog 2015-02-18 20:16:10 description

SECOND FOREWORD (Whole-life Health Insurance)

A short summary of the proposal to fund health insurance, so far. The proposal supplements and funds almost any health insurance, and does not replace it.

Details of Lifetime Health Savings Accounts (L-HSA)

New blog 2015-08-13 20:22:30 description

Converting Term Health Insurance Into Lifetime Health Insurance

Instead of estimating future health care costs individually, we calculate what is now spent on health care and extrapolate its future trajectory. Working backward from an overestimate, we could come closer than traditional approaches. Health Savings Accounts invest and return the unused surplus to the beneficiary, consequently with less resistance to aiming a little too high. Extracting extra revenue from invested premiums provides a layer of safety to estimates. We suggest peeling back Medicare from last-year-of-life, one year at a time, as revenue justifies. (www.philadelphia-reflections.com/blog/2682.htm)

Some Underlying Principles

New blog 2015-03-03 19:33:22 description

First Year-of Life and Last Year, Combined

New blog 2016-05-25 22:26:26 description

Escrow Accounts for Future Needs.

Within a Health Savings Account, it is necessary to have some nest eggs that the subscriber can touch, but he would rather not. And other accounts which are borrowed, which ought to be paid off, first. That's just the way life is, of course, but it's better to keep escrow accounts, to indicate different designated purposes.

Transitions To Donated HSAs, for Children

New blog 2015-06-11 15:21:09 description