3 Volumes

Health Reform: A Century of Health Care Reform

Although Bismarck started a national health plan, American attempts to reform healthcare began with the Teddy Roosevelt and the Progressive era. Obamacare is just the latest episode.

Health Reform: Children Playing With Matches

Health Reform: Changing the Insurance Model

At 18% of GDP, health care is too big to be revised in one step. We advise collecting interest on the revenue, using modified Health Savings Accounts. After that, the obvious next steps would trigger as much reform as we could handle in a decade.

Reflections on Impending Obamacare

Reform was surely needed to remove distortions imposed on medical care by its financing. The next big questions are what the Affordable Care Act really reforms; and, whether the result will be affordable for the whole nation. Here are some proposals, just in case.

SECOND FOREWORD (Whole-life Health Insurance)

This second Foreword is a summary of a radically modified proposal. It cannot be implemented without further changes in the law or at least some clarifications of the Affordable Care Act. To state the issue, it is that increasingly larger proportions of American lifetimes are not employed, and therefore are not able to take full advantage of an employer-based system. It becomes increasingly doubtful that thirty years of employment can sustain sixty years without earned income if you include childhood. Further, there is every reason to expect further migration of illness out of the employable age group. And finally, while there are signs of reasonableness, the mandatory stance of Obamacare is not greatly different from a package of mandatory "benefits" imposed on all attempts at innovation before they can be tested. If changes in the law are required before implementation, liberalization might as well be in place before innovations are proposed. No private company could proceed at arm's length without advance assurances resembling cronyism. Everything else is negotiable, but the notion of mandatory pre-approval of any modification must be softened to something less sovereign.

Sickness itself has moved into the retiree age group and will continue to migrate there. The means of payment cannot move from the employee group, so a two-step process is resorted to, with the middle-man government controlling the flow of money between age groups. If we are ever to remove middle-man costs, this feature must be removed, as well. Meanwhile, the paraphernalia of medical care, the medical schools, hospitals, and doctors, remain largely in the urban areas where employment formerly centered. So the government once more becomes a middle-man, and the system begins to resemble a virtual system, based on computer systems which do the job without actually moving. Until everyone stops moving, such duplication increases costs degrade the quality and start riots. We must move people less, and move money more. At one careless first glance, that sounds like shifting money between demographic groups, but picking winner and loser demography has repeatedly been shown to be too divisive; almost a prescription for a second Civil War. In short, we have fallen in love with a computerized virtual model, based on the faulty assumption that it is without cost. Here and there it might be tried experimentally, but it is far too early to make it mandatory. Consequently, it proves much easier to re-design the payment system, shifting money between different stages within individual lives, than to make everyone find a new doctor, just because the insurance compartment changed. It is absurd to make everyone move to Florida on his 66th birthday. Even redesigning transaction systems is not easy, but it is by far the easiest choice. Nevertheless, there is still too much friction in the various systems to make such improvements mandatory.

The best model to adopt is that of the university president who ordered a new quadrangle to be built without sidewalks. Only after the students had worn paths in the lawn along their favored routes to class, did he cover the paths with concrete sidewalks.

The issue at the moment is that money originates with employers, supporting the whole system, but their employees no longer get very sick. To reduce complaints, they are given benefits to spend which they really don't need, raising the cost of transferring the money to retirees who do need the money but are covered by Medicare. We are in danger of repeating that whole cycle with Medicare, piously calling it a single payer system, when in fact it would be a single borrower system as long as the Chinese don't collapse. Expensive sickness now centers in the retirees, but within fifty years a dozen diseases will be conquered, and we will then need the Medicare money to pay for retirement living. Constructing massive systems without that vision will just make it harder to replace them. We are, in summary, in great need of a gigantic funds transfer system, since moving the people and institutions to match the funding is preposterous. But as long as the system has two champions (Medicare and the Employer-based system) in possession of all the money, we flirt with collapses in order to force rearrangements.

All of this is divisive, indeed. For years to come, the easiest thing to move around will be money. Eventually, institutions and clients can sort themselves out for geographical unity, and probably improved efficiency. But a financing system with the money for sickness in the hands of people who aren't sick, plus a governmental, system dedicated to an age group with almost all the coming sickness but unsustainable finances -- is a wonder to behold. Therefore, we offer the Health Savings Account as having the flexibility to collect money from the young and healthy, invest it for decades, and use it for the same people when they get old. It can cross age barriers and follow illnesses, or it can remain with survivors and pay for their protracted retirement. If Medicare is modularized, it can supply the money to buy pieces as they begin to appear less desirable. It can redistribute subsidies to the poor if an agency gives it money, and it can adjust to changes in geography and science, since all it works with, is money. And it avoids redistribution politics by giving the same people, their own money.

For all these reasons, Health Savings Accounts on a lifetime or whole-life model seem the logical place to fix the broken vehicle, while we somehow keep its motor running. If successful, it will grow too big, so it should remain modular from the start. It has feelers in the insurance, finance and investment worlds. It could easily arrange branch offices for retail marketing and service. It should have networks for research and lobbying. But as long as it retains the branch concept and avoids the imperial one, it should manage to keep the doctors, patients and institutions functioning as the whole universe rearranges itself -- at its own speed. The first major step in this process would be to clear up some regulations which did not anticipate it. With Classical HSA adjusted for the interim role, the design stage can be undertaken to link the pieces of a person's health financing. Variations of lifetime Health Savings Accounts can be tried in demonstration projects, perhaps staying out of the way of the Affordable Care Act by unifying parts other than age 21 to 66, as the New Health Savings Account. And then seeing which version of lifetime HSA survives the squabbling. That isn't all. The really big picture is to absorb the pieces of Medicare, one by one, as sickness retreats from being the central cost, and the cost of retirement becomes the real threat.

Foreigners Are Fed Up With Paying Our Bills.

|

| Obama Signs Health care Bill |

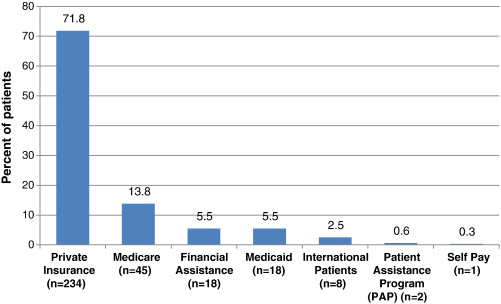

Implementation of the Affordable Care Act, often called Obamacare, is about to begin, but a majority of the public express fear of it to pollsters.

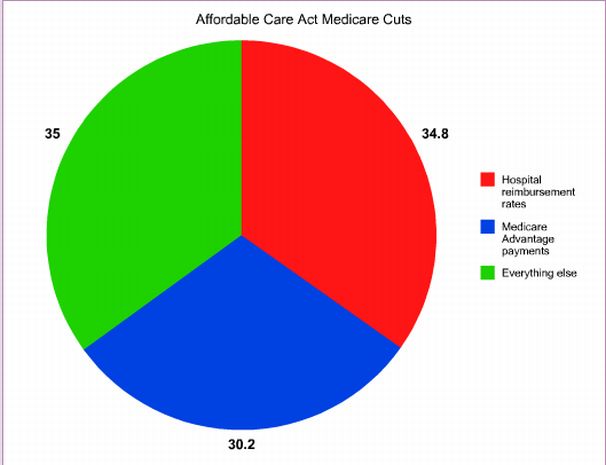

Obamacare is essentially a modified version of Medicare for the younger generation, so at first it's a little hard to see why that is so threatening. Presumably, Mr. Obama is also a little puzzled by the reaction, although he has an unfortunate way of attacking anyone who disagrees with him. Can it be that he fails to see the main thing the matter with Medicare itself is its cost overrun?

The first announced preference, and now the fall-back, was a "Single Payer" system, which would simply combine the two deficits into one bigger deficit. The Affordable Care Act does indeed follow fifty years of general satisfaction with Medicare for people over age 65, because everybody enjoys a dollar for fifty cents. The main source of public uneasiness arises from a vague recognition of Medicare's unsustainable mismatch between costs and revenue, which has been pretty effectively buried in a mass of information. You might say it is in plain sight, except it really isn't plain.

Medicare is 50% subsidized by debt, so everyone gets a 50% discount from real costs, and naturally loves it. But after fifty years of off-budget borrowing, the nation now wonders if we can even keep Medicare up, let alone add another program to it. The public surely does not understand how the deficit was "overlooked", maybe doesn't even want to know. But when the debt gets so large it begins to crowd out everything else the public wants, people are not stupid, and they see it plainly. In fact, they have realized it for some time, and the elderly in particular are fearful that giving the same generosity to everyone mught eventually mean taking some of it away from them.

The small businessmen who are the main strength of the Tea Party movement, see they have been excluded from the income tax subsidy enjoyed by employees of big business for the past seventy years. They are particularly enraged by the new cost barrier to going from 49 to 50 employees, and the implicit penalty for working more than 30 hours a week. It doesn't seem fair, it shows no sign of going away, and they fear to see it extended. On the other hand, the employees of big business, just like the Medicare recipients, know very well they have been given an undeserved free ride, and are fearful it will be taken away to pay for other people.

In short, the economy is hurting, leaving no room for sprinkling goodies to everybody. America's balance of trade went negative in 1965, and has stayed negative ever since. So the crunch of borrowing from foreigners was a long time coming, but it seems to be getting to an end. It can't continue without squashing someone. Omitting the youngest and poorest of our country, just about everyone recognizes that to be true, and is uneasy about where it might lead.

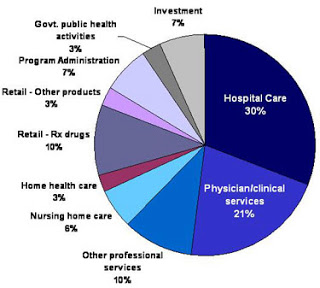

Since healthcare costs are "only" 17.6% of current Gross Domestic Product (GDP), extra financing might not be required for Obamacare as long as the rest of the economy remains steady. After all, we proved you could borrow 75% for short periods, by trying it for a while during a recession. Even if the nation -- at any age -- could afford 17.6% of GDP for health, some method is still needed to share out the medical debts of those who cannot support themselves. If the upper half of the population supports the bottom half, for example, and graduated income taxes take increasing proportions off the top, it's not clear even the rich could afford 17.6% medical costs plus 74% in taxes, as the French do and some economists advocate. Especially if you double it to 35% to account for the hidden subsidy, and arrive at a total of 124% of income. So the real breaking point depends on details, but a national mandate is getting clear: Don't make things worse.

From the point of view of the non-rich, it's probably worse, because it always is. Campaign rhetoric has encouraged most people to suppose their own needs will be met, but foresee minority interests suffering to protect the interests of the majority; "crowding out" is the familiar danger during a recession. Gradually raising the present 17% -- to 18%, 19% or even higher -- suggests the frog-boiling approach of heating up the pot before the frog senses what approaches. One possible limit to public tolerance can be imagined: It is plainly unacceptable for the top 49% to pay all the costs for the bottom 51%. If "fairness" means anything like that, fairness will be discarded, and that would make a fine mess. It is clear the designers of the Affordable Care Act are disconcerted by the amount of cost-shifting they discovered was already taking place, and it does not soothe the public for Nancy Pelosi to announce we had to pass the Act to find out what was in it. To act without investigation is pretty much what happened with Medicare in 1965, so it's less likely the public will tolerate a repeat of it.

At least, don't make things worse.

|

This book does not address redistribution by social class, but by age. The "pay as you go" system practically guarantees the last one in will get the worst of it. The proposal parade begins with only one suggestion for new revenue, emerging from modifying Pay/Go by compounding investment income within Health Savings Accounts. Because the sums are large, several following chapters explore pitfalls, safeguards, and accommodations. Following that, come a dozen proposals for cost reduction. Waste is unfortunately also abundant, and must be cut. However, it is generally less useful to hunt down villains because, after the struggle is over, we must live with each other.

Simple Gifts

So much for expecting foreigners to help us. They remain grateful to America for winning World War II, but that was seventy years ago. Forget about reserve currencies, a declining surplus of gold bars, the Marshall Plan, Truman Plan, and all that. After seventy years of thanking us, foreigners quite rightly expect us to pay for our own health care without monetary subsidies from them. Or protectionist trade policies, either.

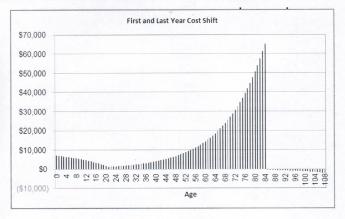

To begin with healthcare basics, lifetime medical costs over the past century have progressively migrated toward the end of life, and the end of life has itself moved later. Lifetime earnings remain concentrated near the middle of life, so a gap widens. Collectively, the population accumulates wealth during its working years, spending its savings for healthcare after it retires. If lifetime health costs could be pre-paid and funneled into savings, with the savings professionally invested, a large proportion of medical costs might be paid out of investment income. It could be called the difference between pre-payment, and insurance, except whole life insurance, employs the same principle. Considerably expanded, this insight could markedly reduce the cost of healthcare, making it more affordable without changing it. Because medical care is undisrupted, the hidden cost of disrupting it might vanish, too. It creates what the Japanese call a virtuous cycle. (It wouldn't hurt to read this last paragraph a second time.)

If lifetime health costs could be pre-paid and funneled into savings, with the savings professionally invested, a large proportion of medical costs might be paid out of investment income.

|

The average American healthcare costs we are discussing are in the neighborhood of $10,000 a year, surely somewhat less for younger peopleFootnote . They are about double that for the last year of life, somewhat less than that for the first year of life. Medicare is about 50% paid for by subscribers, 50% subsidized by additions to the national debt. Ignoring inflation and tax effects, the net average real lifetime health cost at such rates would be at most $800,000, of which $400,000 would be additions to the national debt. Remember, projecting healthcare costs seventy years in advance is a very hazy business. We certainly hope these projections prove to be a gross over-estimate, but to remain on the safe side the proposal here is to make a lifetime investment to cover only the first and last years of life because the heavy costs of birth and death affect 100% of the population. The projected cost of these two benefits would be $30,000, from which $15,000 could possibly be subtracted as the national debt, or else subtracted as double-counting the cost-shifted expenses of indigents. Meanwhile, removal of the first-and-last year costs would reduce annual costs by about 4%, or $30,000 lifetime. So it seems safe to start with a $ 15,000-lifetime goal, which could be achieved by investing $8 at birth at 7% tax-free return. That's right, eight bucks. Different assumptions produce different answers; the only purpose of the example is to demonstrate easy feasibility of the approach. Multiply the initial contribution by five or ten times, and you reach the same conclusion.

Scientific advances during the last century greatly changed the shape of two curves, of lifetime income and lifetime medical expenses; future advances will surely do the same. The life expectancy of Americans roughly lengthened by thirty years and continues to increase. The logic of compound interest demands that money at 7% will double in ten years; the longer you live, the more times it will double; that's pretty old stuff. What is new and unique is the way adding three extra doublings helps the virtuous cycle, maybe changes it significantly, because 2,4,8,16,32 keeps getting a lot bigger at the far end. Three more doublings make the difference between 32 and 256, and that's a drastic difference.

But, whoa, on the other hand, the longer you keep money in a bank, the more opportunity there is for financial crashes, inflation, "moral hazard", mismanagement, changes in political philosophy, wars and a thousand other things. Eighty years is a long time from now; who says the money will be there when you need it? And even if all the 19th Century nightmares are merely pipe dreams, an awful lot of Americans remain mistrustful of financial institutions. Presidents Jefferson, Jackson, Van Buren and an equal number of nearly-successful candidates for president were even in favor of abolishing banks. A large and possibly growing number of Americans distrust the Federal Reserve, and with some reason. After all, a dollar in 1913 when the Federal Reserve was founded, is now worth a penny. Pause for a moment, reader. You have now heard both sides of the argument, the opportunity and the risk. Everything from here on details. At some point in the next century, investing a few dollars at birth will generate enough income to pay for both being born and dying, the two medical conditions which are 100% certain. It might even generate enough to pay for lifetime medical care, and more, but that isn't the point. What matters is for us to have the wit, and the courage, to take advantage of something which sort of crept up on us.

Footnote The data used here are rounded-off and approximated 2011 data obtained from HHS reports. It is intended that a later edition of this book will contain an appendix of actual 2013 statistics, the last year before the Affordable Care Act became operational.

Grand Strategy: Semi-Insured Health Insurance

Employer-based health insurance. Although improved health care has added moderately to working years of life, a lot of people hate to work, whereas to other minds, thirty years of improved longevity mostly result in a thirty-year vacation after the end of productive careers. The famous American work ethic is not universally celebrated. Pensions and savings sometimes only partially anticipate the cost of enjoying this health windfall, which unfortunately competes with yet another unexpected cost, the steadily increasing expense of dying. These changes were both rapid and unexpected, so confusion is inevitable.

There is still another way of describing this readjustment to a wonderful scientific windfall: Most sick people are now either too old to work or else too young to work, even before they get sick. Health costs therefore relentlessly concentrate toward the first year of life and the last year of life. The strategy we developed of hiding the health costs of the young and the old within the health costs of the worker class confronts the new reality: middle-aged people have many fewer health costs, themselves. That leaves less room to hide the costs of the sickly young and the sickly old, which all along have been buried within the premiums of workers' health insurance. Let's face a fact: Those who are neither near the first year nor the last year, must somehow pay for those who are -- because there is nobody else.

Hiding the health costs of the young and the old within the health costs of the worker class confronts the new reality: middle-aged people have many fewer health costs, themselves.

|

So now we have the Affordable Health Care Act, commonly called Obamacare. It remains to be seen whether even Obamacare can be made to stretch, because thirty years is a long time between retirement and the last year of life, and fifty years a long time to wait to judge results. With wars, globalization of industry and depressions to contend with, the task is hard, perhaps too hard. Unfortunately, having passed a law containing the Affordable Care Act mandates, we must try to do it in 2014, and do it in a rather utopian way for everybody at once. For what amounts to a level "community" premium for everyone, we must make no allowance for differing costs and pre-existing conditions, economic or medical. Many of these wounds are self-inflicted, costing the program many sympathizers who might have endorsed the same goals at a slower pace.

We Had a Secret Plan. It might as well be mentioned that Americans once nursed a secret plan for all this. We consented to spend incredible amounts of money on medical research for eliminating the disease. In fact, we made a pretty good try, considering we never officially admitted it was our goal. If there is no disease, there will be no medical costs to worry about, right? Directly confronted, eliminating acute disease would unfortunately still leave those first and last years to be paid for. There was just no escaping it, everyone has to be born, everyone has to die. And while substantially eliminating disease among the young and middle-aged is an important economic stimulant, it also lengthened life expectancy by almost thirty years in a single century. Those who managed to prosper were indeed rewarded with a thirty-year vacation, but some of the windfalls had to be set aside for those whose luck was bad, destined to spend thirty years in the shadows. It was a big, bold gamble, and in an American sense, we won it. Never acknowledging it was a goal, no one could say we lost it.

Americans will help others if they can, but first, they must be convinced that others cannot pull them down.

|

We are now engaged in a great upheaval described as insurance reform, to test whether a great nation which secretly believes it can do anything, can satisfy both those who believe it has attempted too much, and those fearful it will fail by aiming too low. Arguments abound. One description of victory would be this: we must abandon the essentially European idea of rich and poor as permanent classes of society. In its place, we should reaffirm the traditional Whig position that rich and poor are largely two or three, or four, stages of every American's life. In Lincoln's view, we all arrived as poor immigrants, gradually worked our way upward in society, usually taking several generations to reach the top. No more than a handful of born aristocrats ever immigrated to America. In a revised version of the same epic poem, all infants are poor, adolescents are always confused, and gradually we become self-sufficient members of society; eventually, we all die. Whigism refuses to see us as members of tribes, some eternally rich, some eternally poor; Whigs mainly hope that Liberty and personal responsibility will be sufficient to preserve the more perfect union. In Lincoln's case, it was a close call, but we made it, even then.

Obviously, people with income must support the disabled, since there is no one else to do it; equally obviously, the nation has not evolved to the point where it can be done by having one angry tribe tax another. Instead, what is needed is to organize some sort of insurance pool in which younger people contribute for their own individual future, recognizing frankly that people will chiefly fear the system cannot keep its fingers off the money to give it back eighty years later. That's really all that is essential, since many models have tested the insurance market, and watched eyes glaze over with the details.

Young people must subsidize sick old people, all right, but the only old person you surely enjoy subsidizing is yourself. For the moment, forget about the difficult transitions, about which 2500 pages of the law were written and will prove to be too little. The challenge to the country is whether we collectively have the courage to stake our lifetime earnings on the proposition that the average person can save enough of average lifetime earnings to pay for average lifetime medical costs, and still have enough left for a comfortable life. If he can't, this scheme is not going to work, because even if he can, the scheme might still fail. A thousand folksy mottos teach us that Americans will help others if they can, but first, they must be convinced that others cannot pull them down.

The Law of Compounded Interest. There's a seldom mentioned advantage to individually owned and selected insurance-like pooling of lifetime health costs. If insurance premiums are pooled, stored, and invested by professionals, they will gather investment income, or compound interest in quantities which always surprise a newcomer. To wit: money at 10% will double in seven years. Or, stretched over long time periods, the owner can withdraw 4% a year, forever, and still have as much as he started with. Within ages, 25 to 75 exists an opportunity for five doublings at 7% or 3,200%. Hidden in this is another incentive: if you only spend half as much money on healthcare as average, you can eke out another doubling, making it 6,400%. Transforming medical insurance from term insurance to a "whole life" insurance model carries the potential for vastly diminishing the lifetime cost to the average subscriber, but that opportunity probably did not exist a century ago. We may say we sacrifice this new opportunity because we do not quite believe it, but in fact, we mostly do not trust any government to give it back, eighty years later.

"Whole life" insurance model carries a potential for vastly diminishing the lifetime cost to the average subscriber which did not exist a century ago.

|

This paper, therefore, urges a voluntary approach, individually owned and individually selected, primarily because it seems safer to go a little slower than we could if we just followed a command. Anything which includes the word "mandatory" also forbids the testing of alternatives. At least theoretically, alternative approaches are forbidden forever, with the implication that nothing better will ever be possible. At the barest minimum, the Affordable Care Act must be amended to encourage the testing of new ideas by Congress and by state governments. Another similarly hampering word to avoid, is "perpetual", but it seems more conciliatory to avoid the word "insurance" and to outline the nature of this proposal as a non-insurance savings mechanism limited to lifetime health expenditures. To a framework of five proposals, about a dozen other features are later described but held in reserve, waiting to be added slowly as the system can absorb them. This is neither an Executive Branch initiative nor an insurance company product. It is a national strategy, which starts with individual Health Savings Accounts and builds on that foundation. It adds a high-deductible health insurance policy, preferably without co-payments. It strips down the benefits offered by the HSA to the first and last years of life, to prove the concept safely, and to pay for transition costs. After that, it should expand like an accordion to cover as much as it can afford. Beyond that point, we can argue some more, but we are aiming for maximum elimination of complication and subsidy, not because they are necessarily bad, but because they should in time be unnecessary.

Pre-Paid Death Benefits

There's an old joke about a small town with an ordinance that "Fire hydrants must be painted before each fire." Similarly, it is at first a little confusing about how pre-paid health insurance could pay for the health care costs of someone's last year of life. Necessarily, such a proposal implies the existence of a second mechanism for paying for the costs as they arise, but getting paid back for them later.

Right now, that primary insurer is Medicare. The vast majority of people who die will be covered by Medicare when they do so. So, let Medicare pay the bills, and let the Health Savings Account pay Medicare back. And looking backward, when the Health Savings Account reaches a certain amount, reduce the premiums and payroll deductions for the individual. The overall payment cycle thus means the individual only pays for his care once, with compound investment income contributing the bulk of it. The final intention is to start with the goal of paying for the last year of life, and expanding the number of years like an accordion if you have been lucky and contributed a lot toward the fund, early in life, and not depleted the fund with illness. I'm no actuary, but as a physician, I can tell you that if you have a lot of major illnesses, you will probably have a foreshortened future.

The individual's Health Savings Account is a long-term investor in longevity, paying Medicare back when the last-year costs are known, and receiving a reduction in payroll taxes or Part B premiums in the meantime.

|

In this example, it is Medicare, universally available for at least Part A (hospital costs), which is imagined as the transfer agent. However, it also ought to work with patient self-insurance, paying for out-of-pocket costs like deductibles and copayments, or with coinsurance, or Major Medical, or any other verifiable source of health payment. Because of such contingencies, it is better to keep track of actual expenses which reimburse individual expenses outside the Health Savings Accounts. Payments through the HSA account should certainly count if they fell within the last year of life, but safeguards would have to be created to discourage gaming the tax deduction. However, we are envisaging transfer payments only at death, so this might not prove to be the problem it seems.

There is no doubt that transferring to Medicare the nationwide average last-year-of life costs as a lump sum (rather than true itemized individual costs), would greatly simplify the accounting, and perhaps Medicare could devise a way to reimburse self-insurance contributions and other participating payers. The trouble with passing it all through Medicare is that it gives the Medicare administration an opportunity to make the rules, which other payers would immediately complain about. Itemizing also has the advantage of putting pressure on the process of billing, which for mysterious reasons now takes six months or more.

In the meantime, the money has to be set aside in some sort of "lockbox" or escrow fund. Individual records must be maintained because it is anticipated the existence of this pre-funded last-year escrow fund provides continuing authorization for reducing payroll taxes and Part B/D premiums by 4%, the amount of the future reduction of Medicare beneficiary costs in our example. Because it is anticipated that the last-year escrow system might eventually accommodate accordion-like extensions of itself, it should be careful not to take early short-cuts which would hamper that evolution. Eventually, the annual Medicare deficit should be reduced by at least 4% fewer costs in our example. Going all the way to 100% of costs is imaginable, but unwise to implement quickly without some experience to act as a guide.

Post-Payment for The First Year of Life

Having observed the medical student adventure of assisting uninsured home deliveries, where the main tool employed was a pile of old newspapers, I am acutely sensitive to the wide variation in obstetrical costs. Wide-spread obstetrical insurance is almost certain to increase the cost of being born, and the intrusion of their disproportionate malpractice defense costs also seems uncomfortably open-ended. Just glancing at the inordinately high malpractice premiums for obstetricians will tell you who is doing the suing, and for what justification.

By including the post-natal checkups and immunizations (with their own malpractice component), it becomes difficult to extrapolate what first-year-of-life insurance costs might become, under pressure of the illusion of being cost-free. However, we seem to be in a demographic decline, where it becomes increasingly desirable to increase the birth rate by diminishing its cost obstacles. If abuses can be minimized, obstetrics is one area where public subsidy seems to encounter public approval, and self-insurance is not at all practical. In fact, almost the same could be said about all health expenses up until the age of eighteen, but it seems a pity to lose the opportunity for two doublings of investment income because of unsettled disputes about marriage, divorce, feminism and the responsibility for child support.

Although expediency in the direction of taxpayer support may prove to overwhelm this admittedly contentious area, the expenditures are comparatively small, so it still seems useful to explore what could be done with first-year pre-payment. Health costs which someone must pay do exist for children growing up, and the emotional appeal of insurance for this group is strong. Getting their health care finances organized before they reach the workplace would be a useful thing since the tendency of healthy young adults to duck the costs is part of what caused a present uproar about uninsured obstetrics. All of which is to say: social gains might justify public subsidy for the first year of life, at least in part.

The individual's Health Savings Account becomes the long-term banker for the first year of life, with the first conventional health insurer acting as short-term banker.

|

Someone is paying for the first year of life health costs, and that someone would appreciate getting reimbursed for it, fairly soon. Therefore, the addition of less than a hundred dollars to the costs of the first health insurance company to enroll an individual would not deter the enrollment very much or even stimulate much switching between insurers later to evade it. The intent is to open a Health Savings Account, borrow from the first insurer, and pay it back when enough money has accumulated in the HSA.

If no insurer steps forward in a reasonable time, a small and temporary government loan might be in order. In return, the insurance company could anticipate a profitable and "sticky" customer for many years, meanwhile exerting more downward pressure on obstetrical costs than the young parents ever could. That is, by retaining the right to reject a customer for bringing along excessive obstetrical prices, those prices would re-open to negotiation. And realistically, a disproportionate share of obstetrical deliveries are paid for by Medicaid, which would lead to some taxpayer subsidy. In the case of uninsured obstetrics, it would appear the individual Health Savings Account itself would have to be the banker. But since the purpose of the Affordable Care Act was to leave no one uninsured, this might conceivably pose little problem. To say much more about this approach would be foolhardy until the Affordable Care Act begins operations and stabilizes its rules. The essence of it all is to make the Health Savings Account the payer of last resort for obstetrics, in the far distant future when compound investment income should be ample. The first childhood health insurer would become a voluntary short-term banker until the HSA grows enough in size to buy it back. Because it is so vital to keep opening costs low, the pressure to maintain obstetrical provider costs within reason is essential.

The advantage of looking at the retrospective payment for the first year of life lies in its quality of affecting 100% of the population. Its disadvantages mainly grow out of the ambiguity of who is responsible for the costs, the child or the parents. For obvious reasons, Society has chosen to select the parents. However, this leads to hidden incentives for the employer and the insurer to discourage procreation. In turn, this brings culture and religion into the discussion to an unknowable extent. It is probably not a safe subject for a book on medical economics, and we will conclude by merely mentioning the matter.

The First Year of Life, Leading to the Rest

|

| Locked Savings |

We have already discussed how relatively easy it would be to anticipate the average medical costs of everyone's last year of life, put the money into a securely locked piggy bank, and gather interest to help pay for that dreadful last year in the same way whole life insurance pays for funeral costs. One hard part is to keep Congress from dipping into the lockbox, or the Federal Reserve from robbing its real value by allowing inflation. However, if protecting the Lifetime Escrow can be presented as financing everyone's health into old age, the public might well rally to it. Any agitation necessary to defend the piggy bank might by itself be a boon to reminding the public what is at stake for them. By comparison, generating the funds might actually be the easy part.

But what about the first year of life, whose expenses have already been spent? (The term is loosely applied here to include pregnancy and post-partuum, plus pediatrics). The concepts are introduced of pre-funding terminal care, paying off the debts of getting born, and current-funding the long healthy stretch through most of life. The proposal is to merge it all after transition steps taking decades, fully recognizing that some people will have to pay twice for having been born, and some will never pay for having to die. Indeed, in any insurance plan, there is some unfairness in order to remove risk. First, get the terminal care fund established and funded, showing benefits in the first year or two as proof of the concept. Then, start collecting additional contributions to the terminal care fund for the moral debt each citizen has for his early childhood costs, and do it for perhaps ten years. Add this money to the terminal care fund, but make its finances as visible as if they were separate. Meanwhile, keep chipping away at the maternity and childhood costs of litigation. The first chip is to recognize that malpractice costs are disproportionately concentrated in this group, so the fund would greatly benefit from tort reform. Vaccine costs are also strongly influenced by liability costs. One subordinate goal is to present the cost of childhood as partly a score-card on progress in tort reform, broadly defined, ultimately rallying the public to restrain itself in the jury box. The mechanism would be to dramatize the disproportionate concentration of these costs by local and national aggregation, letting the news media speculate on the variation.

Finally, it should be said the Health Savings Accounts are a vastly more flexible way of paying for health care than using the service benefits approach, at a time of great flux in the system. These accounts are described in greater detail in subsequent sections, but the main advantage at this point is to translate fund transfers into money without service benefit attachments, to make unification and substitution more plausible.

To some degree, service benefits are in conflict with indemnity benefits, in a manner resembling the conflict between debt and equity in the banking sphere. The best one can hope for is to shift the location of the interface between service benefits and indemnity, bringing the friction out into public view, and equalizing the power of contending sponsors. Therefore, the best place to present the issues is to regard DRG diagnosis groups as service benefit subsets, and outpatient costs as aggregated indemnity. But one of the main mistakes of the DRG system was to extend it to every hospitalized inpatient. This is particularly important in situations where the diagnosis has no relationship to a particular length of stay or average cost level. Inpatient psychiatry should be paid for as if it were an outpatient service, and chronic diseases such as Alzheimer's disease should be excluded from DRG as well. Emergency room visits should also be separated into two groups, depending on whether the patient is subsequently admitted to the hospital.

We started by saying these issues should be chipped away, during the period when more pressing issues are being addressed head-on. The first and last years of life are disproportionately expensive, so they need special attention to cost reductions. But the list of other small issues is a long one, providing ample opportunity for trade-offs within ambiguous opportunities. The main goal of these new proposals is to redirect cost-shifting perceptions from something to escape if possible, into a vision of advancing sensible provision for your own risks at a different age. The notion of generating investment income is not a small part of the notion of prudent behavior.

After this short treat, of a long-term vision, we now return to more practical short-term proposals. The heart of them is the Health Savings Account, but several preliminary features must be explained in advance.

Ideal Universal Health Insurance on the Accordion Model

Let's compress the basic idea to simple end-of-life funding, to show how much can be made of the two basics. And then using the accordion model, expand the basic ideas to five, in order to cover the health expenses of an entire average lifetime. And eventually, expand the patient contributions to match. If the parents or grandparents of a newborn child deposit $2000 in a Health Savings Account at the time of the child's birth, using 7% return as the projected lifetime average investment return for life in an index fund of the entire American stock market, and do not disturb the account for a life expectancy of 80 years, there should be $512,000 in the account at the baby's death. That is the extreme limit of optimism, generating far more income than is likely to be needed. Beyond this limit, overcoming initial obstacles of a zero-interest environment, the uncertainties of inflation and war, resistance by competitive insurance and political alternatives, and other risks and alternatives -- make the whole project unlikely to succeed. That sort of defines the general limits of the idea's initial feasibility as extending from a low investment of about $10 to an upper limit of $2000; more is possible, but this is enough. It uses two ideas (the Health Savings Account and the Last-Year of Life Escrow) to show that there is surely enough money generated to cover the cost of eliminating the last year of life cost of Medicare. With that sum in escrow, a calculation should also be possible to estimate how much Medicare premiums might be reduced for the owner of that escrow, acting as the ultimate goal of everyone involved. There are of course some people who would want a solid gold casket for their own funeral, so there probably must be some "service benefit" features to the program, but in general, it is envisioned as an indemnity, leaving the issue of price control undefined for the present. Taken all together, a package can be assembled within the rule of reason to show how much a lump-sum advance payment would reduce Medicare premiums as an incentive for the average person to enter into it. Naturally, if you wait to enter into the agreement late you will need to deposit more money, but that figure is easily derived from looking at the average net value of four or five index funds at the time you finally make up your mind to take a chance on the idea. No doubt, beginning contributions at the age of twenty is more realistic than having a grandparent donate at birth, but it becomes too complicated to establish detailed premiums right now. If you wait until you are twenty, you will need to deposit approximately $8000 to catch up; or only deposit $2000 and be satisfied with a final balance of $128,000. The longer you wait, the harder it gets, and no doubt the proponents of "pay as you go" will object to it. But that's exactly why individual options are preferable. You can start with one program and switch to the other, but it becomes more expensive if you wait. Those who recognized a bargain earlier are rewarded for their risk.

Now, $512,000 is probably more money than is necessary in the idealized, no-problem example. So, let's see what it would take to fund the projected lifetime healthcare costs in their entirety, no illnesses, no stock market crashes, no fees or taxes. The amount projected is surely enough to cover that and leaves some room for illnesses and administrative overhead, but it's getting closer to the bone. At the very least, you would have to subtract the premiums for a $5000-deductible catastrophic health insurance policy, guaranteed renewable, of course. That's needed to pay the retrospective cost of having been born, well-baby visits and all that, so it must have a premium somewhat higher than the quoted one. And there probably ought to be a surcharge for re-insurance, in case the deductible is invaded more than once. Remember, the assumption made is that you will remain in perfect health, which is definitely not the average experience. So, it probably must be conceded that you will also carry routine healthcare insurance for maintenance during your working years, or else pay for your working-life healthcare out of pocket. Out-of-pocket may actually be better, in order to support an active marketplace to set prices, because providers must always be suspected of exploiting a heavily insured environment. On the other hand, let's not be completely naive about the inner workings of life insurance. A lot of its profits are derived from subscribers who drop their policies and never file a claim. Let's go over this, once more:

Liberalization of the Health Savings Account.To start with, let's begin voluntarily, and let the success of the first-responders encourage the timid. There are surely several thousand new parents (or more likely, grandparents) each year who know a good deal when they see it and could afford to pre-fund health insurance for their newborn children for the rest of their lives. (Class warriors will snort to hear this, but it is a basic fact of risk-taking that well-to-do people are about the only ones who can afford to take the untried risks of trying something new.) Starting at birth adds a couple of doublings, and reduces the lifetime net cost remarkably; middle-class people have to hang back because a loss means more to them. Portrayed as an estate tax deduction, it would seem an attractive generation-skipping way to transfer income to the next generation and to grandchildren who would be thereby relieved of the obligation to support the middle generation. Ask your lawyer to explain it to you, it's a good deal.

Do not put a limit on contributions to a Health Savings Account for the children; what's the point of limiting contributions when withdrawals are going to be limited to actual health expenditures? Surplus funding would only be lost and is therefore self-policing. (Eventually, any surpluses in the account should flow into a reinsurance fund for those who exhaust their deductible more than once.) Your accountant can explain that one to you. After the first year, non-participating members of the child's age cohort can catch up by contributing, not the same amount, but the average amount to which the fund has grown in the meantime.

The contributions themselves should be invested in index funds for the whole U.S. stock market, so if stocks have gone down the latecomers have a chance at a bargain, if the index has risen, it shows what a good idea it has proven to be. Essentially, it is an investment in U.S. common stock, which in all but occasional years can easily prove itself. As explained later, the fund will have to maintain a certain investment in U.S. Treasury bonds in order to pay claims, but the extent of this will depend on what the benefits include.

From this basic investment must be subtracted the cost of a catastrophic health insurance policy for the child, with a deductible not less than $5000, net of inflation, to be purchased with the dividends of the fund (premiums for the catastrophic policy are waived until the dividend income will cover them). Essentially, this insurance policy is the source of advance funding for the last year of life escrow. By shifting catastrophic premiums to later years, it is also retrospective funding for the first year of life.

Last Year-of Life Escrow. The issue of trusting anyone, even our own government, with appreciable amounts of money for eighty years is solved in the following way: The funding has been described; it is placed in an index fund and remains there until the beneficiary dies, theoretically eighty years later. The investment performance is therefore widely available on a daily basis. Meanwhile, the average annual cost of the last year of life is available from Medicare. Meanwhile, the average life expectancy of the age cohort is available from the life insurance industry; the average yearly investment return is published by the index mutual fund industry. A year after the death of the beneficiary, the fund transfers the average cost of the last year of life to Medicare and publishes the investment results and theoretical results of alternatives to the cohort. What to do with any surpluses remaining in the fund need not be fully described at this point, but it is envisioned that surpluses remaining after the death benefit is paid to Medicare will go toward the first year of life, followed by other years if additional surpluses appear. On the other hand, reducing the cost of Medicare for the last year of life would enable a reduction of the premium costs for other years, so perhaps it would be better to pay off the existing debts of Medicare.

The immediate purpose of the steps described is to reduce the cost of Medicare. If it does not cover the complete cost of the last year of life, it at least reduces it significantly at little administrative cost. Since lifetime medical costs ordinarily reach a peak during the last year, there is a potential for virtuous cyclic increases to include more of Medicare costs than the last year alone, but this is not promised. If it reduces Medicare costs significantly, donors of the fund enjoy lower Medicare premiums than otherwise. Numerous alternative proposals are available, as described in later sections, and it is not useful to start unnecessary quarrels about such contingencies at this stage of the debate.

Commentary This proposal combines features of first-year and last-year insurance, resting on a framework of Health Savings Accounts, with the funding incentive of generation-skipping tax avoidance to provide seed capital. With adjustments based on revenue experience, it can be designed to remove about two-thirds of lifetime medical costs from future federal budgets, but it intends to leave undisturbed the comparatively routine health costs of the working population. Although it addresses the majority of costs, at present it affects only two years of the average lifetime and does so by indirect reimbursement.

Problems Needing Attention. Seventy years of health insurance have demonstrated that any provider system will readjust to any generous source of funds by attempting to make it even more generous. It is a theory of mandatory universal coverage that eliminating other funding sources will result in the elimination of cost-shifting, but unfortunately, it will not. State and federal governments compete to shift costs to any easy revenue source, and both the suppliers and the management of healthcare institutions will unceasingly seek to increase their share of the revenue from a compliant source of it. In retrospect, it is extraordinary that we ever thought otherwise. Therefore, this proposal seeks to provide easy income to the health system, but it will surely fail if it relaxes its vigilance. Therefore, the absolute minimum requirement is to lodge investigative power at both the federal and state levels, to be certain that only market-based prices (or relative values) are paid, and that indirect mark-ups are reasonable. It seems advisable to retain a small portion of healthcare costs with the consumer so that rebates and surcharges coming from the main fund will serve to remind the public of its need for vigilance.

Secondly, if cost controls do become efficient, incursions into the quality of care must soon be looked for. Professional self-regulation is one defense, consumer vigilance is another. Both approaches suffer when they are undermined by careerism, of which the plaintiff bar is an outstanding example. The whole matter needs re-examination, and probably would be improved by establishing greater direct tension between these three groups with the greatest conflicts of professional interest. At the moment, they all need more term limits if rotation within professional silos is not feasible. The Constitutional Convention of 1787 would be a good model for working out the proper balances between interested parties; they should be given six months to work it out, but not a day longer.

Concerns Provoked by "Whole life" Health Insurance

An entirely new concept like reconstructing health insurance on the "whole life" model can be expected to provoke concerns. Here are a few of what surely is not yet a complete list:

Inflation. It is true that rampant inflation would be injurious to the whole idea of permanent health insurance. However, it is the job of the Federal Reserve to maintain price stability, and many changes have taken place in the Federal Reserve's methods of operation since 1913. The most notable one was the abandonment of the gold standard by President Nixon in 1972 as a late consequence of flaws first introduced at the Breton Woods Conference in 1945. Observers may be of the opinion that the gold standard was stronger protection against inflation than the present inflation-targeting one, but the latter is nevertheless the system under which we operate. It should be recalled that in 1945, America had two-thirds of all the gold in the world, and international trade was being stifled by the unbalanced distribution of any common means of exchange. The correction of this gold maldistribution finally came to an end when a correction was no longer necessary, and indeed in 1972, it was possible to foresee an American gold shortage if trends continued. The American currency is no longer supported by a link to gold or any other commodity. In its place, the Federal Reserve issues or withdraws currency from circulation in response to inflation, attempting to maintain a steady inflation rate of 2% to match the growth of the economy. There are disputes about exactly which inflation rate would be ideal, but the ability of the Federal Reserve to maintain its stated targets has been reassuring. While there is room for argument among economists about the precisely optimum inflation target, the variation has been less than 1/2 %, even in times of economic disorder as severe at the present one. The projected finances of funded health insurance can safely sustain much greater miscalculation than this. If a threat is present, it comes from other directions.

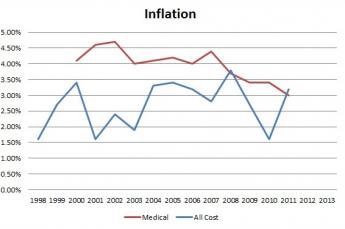

|

| Inflation |

The suggested choice of an index fund composed of the entire list of domestic American common stocks was intentional and may be vital. The Affordable Care Act's provision for mandatory universal coverage makes it official that the full faith and credit of the American taxpayer stands behind the funding, so the American stock market is a close surrogate of that pledge. Anything which could destroy the stock market would constitute a threat to America much greater than a collapse of its health insurance, and enormous efforts would surely be invoked to prevent such a disaster. The wisdom of ransoming the whole economy to a comparatively small component of itself can be questioned, but it is nonetheless difficult to imagine a default when such heavier consequences would follow it. The same can be said of a permanent stock market decline, a devaluation of the currency, or a bond market default. These things can happen, but injuring health financing would scarcely enter the discussion.

The Changing Mix of Disease. Most of the rest of the world still concentrates its medical attention on the treatment of contagious diseases. In America, contagious disease scarcely makes the top ten concerns. No one would have predicted this a century ago, and no one can predict the mix of diseases, or their cost, a century from now. We do know that people will continue to be born and invariably to die, but we do not know what will kill them or what it will cost. It is even possible that an epidemic will unexpectedly sweep the globe, or an asteroid will hit the earth, but in general, big changes occur over more than a decade and give some time for readjustment. We tend to feel confident that our longevity will continue to lengthen, although in Russia it has lately shortened. Generally, new treatments have patent and development costs at first, and then become cheaper. But even healthcare workers enjoy raising their own salaries. It is difficult to predict population costs for healthcare eighty years from now, or whether they will be distributed evenly throughout the population. Unfortunately, this uncertainty will bedevil any system of financing that can likely be devised, but that does not mean reimbursement systems cannot be designed to cope with it.

Therefore, it is essential that any long-term plan, not just this one, build an accordion system into its initial design, and assign the task of watching over this problem to a permanent oversight body, particularly one which is able to resist the general economic pressures bearing down on the Federal Reserve. Inevitably, there will be times when the two bodies are adversaries. The easiest approach is, to begin with, the first and last years of life as anchors, and extend the reimbursement to intervening years as needs can be projected. This is one of several reasons why it is advisable to anticipate two parallel systems, one paying the bills as they appear and raising premiums if need be, while the other reimburses the first one as its fund permit. If a cure for cancer or Alzheimer's disease should appear, there might be funds to reimburse the other system for eight, ten or more years, readjusting premiums as it goes. If those miracle cures prove to be astonishingly expensive, the accordion would contract the other way, or its premiums would readjust in the other direction. Let us be clear what we are attempting: to reduce the annual premium of health insurance for the working years of life as much as we can. We must resign ourselves to remaining uncertain how much the premium can be reduced in the far future. No one spends public money as carefully as he spends his own. Complexity is therefore useful in areas where moral hazard is an important issue. Otherwise, grown-ups will behave like children at someone else's picnic.

Fluctuating Interest Rates.

At the time of this writing, the Federal Reserve has forced American short-term interest rates almost to zero, and held them there for three years. Japan did the same thing two decades ago, and they have had the unprecedented experience of remaining near zero for nearly twenty years, held there against the will of the Ministry of Finance by what is known as a "liquidity trap". Meanwhile, by the Fed buying long-term bonds in what it calls QE3, long-term interest rates have been forced in the opposite direction to a higher level than normal by the Federal Reserve. It is not necessary to explain here how this was accomplished, or why.What it is important to see is that the value of bonds, both short and long-term, can be manipulated by the Federal Reserve at the will of the Chairman or at most a handful of committee members. Therefore, predicting future prices or rates is nearly futile for everyone else, and investing in bonds is much riskier than it seems. However, there are economic consequences to interfering with markets, so over long periods of time, there are limits to what the Federal Reserve can do without destroying the economy. In a sense, this is one of the prices we pay for controlling inflation by inflation-targeting. There are boundaries within which the Federal Reserve can operate, and eventually, interest rates will revert to their long-term averages. In the very long run things will average out, and in the present context, we are imagining investment horizons of eighty or more years. This is why insurance companies can buy bonds with serenity, and just wait long enough for interest rates to normalize. But there must be an organization with some feature of immortality to intervene if the counterparty (The Federal Open Market Committee) is immortal and has unlimited funds at its disposal.

However, the Federal Reserve is not independent, no matter how hard we try to make it so. We are here discussing money which belongs to individuals who can vote, and who will surely be concerned about the investment policies of 17% of the Gross Domestic Product. The Federal Reserve can thus be easily imagined to develop an occasional severe conflict of interest between what is good for healthcare financing and what is good for the economy as a whole. The pressures which the public might decide to exert are not predictable, except that they would be hard to resist. The public has long proven itself to be a poor investor, buying high and selling low, even when it knows better. It almost seems better to avoid bonds in the portfolio of investments entirely rather than take the political risks, until it is recognized that this fund would soon develop the need to pay its claims every year, even if the stock market is at a low or stock dividends are zero. Therefore, it becomes clear enough that when bonds start paying 4% or more, the fund ought to buy some of them and hold them to maturity, just as life insurance companies do. Perhaps it becomes clearer why insurance companies hold a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, but it is not exactly clear what to do when a fund of this size proposes to start when interest rates are at their present extreme. This sort of technical issue just has to be left to bond market professionals, since it involves short selling and other arcane issues that the public ought to know enough to stay away from.

The Investment Fund Becomes a Gorilla. Any insurance company must segregate a claims reserve fund, to assure it always has money available to pay its claims. In the system we envision here, the potential claims are too far in the future to be confident how much they will eventually become for a newborn baby, etc., but for the cohort just beginning that last year of life, the average cost of the previous year's Medicare claims will be abundantly clear in Baltimore, where they keep such records; it will probably be close to 20% of Medicare's budget. It certainly will be clear contributions to the pool of Health Savings Accounts cannot possibly match the claim cost of the first year in operation, and should try to do no more than reducing the initial end-of-life claims by whatever is available.

Adverse selection of beneficiary composition. Since the actual beneficiary would be the Medicare Trust Fund (and not the subscribers, who would then be dead) the impact of the news of this program would focus on the reduced Medicare premiums for younger subscribers. Medicare premiums would be reduced by no more than 20%, which would nevertheless probably be greeted as a windfall. The true beneficiaries would mainly be successor cohorts already in retirement, although paying off some of the Medicare debts dating back to 1965 would be a splendid idea. The fund will gradually level out, but it will likely take at least ten years to do so. Social Security and Medicare had the same problem at the time of their beginnings and elected merely to borrow the money, essentially never repaying it to the "pay as you go" system.

Eventually, Medicare will be put to the expense of developing premium billing systems of some complexity. At least, this new system has a source of revenue in the investment of its cash accumulations, with an estimated time of twenty years for it to catch up with itself. Much would depend on the medical costs of the twenty years prior to the individual last year of life; at the moment, they are might even be sufficiently lower to make this approach workable. But if some new treatments, for cancer let us say, are more expensive than the years they would add to longevity, this mixed blessing would have to be treated as an independent problem. Other solutions are available; the ability of the government to borrow at lower than prevailing rates are based on the assumption that it is a sovereign debtor. While this advantage is not guaranteed, it does exist and probably would be difficult to change. Furthermore, whether pre-funding would initially appeal more to younger or older people is hard to predict, calculating the potential source of revenue or losses from various mixtures would have to account for any difference in costs among various ages. Creating enrollment quotas for various ages in the early years of an accordion expansion might be workable.

And then, there are some macroeconomic perplexities. As mutual fund and index fund usage expand, fewer stockholders vote their proxies; the present proposal would make this problem worse so there would be even less resistance to lavish management salaries. The influence of family controlled stock within the portfolio, and of hedge-fund control would increase; possibly, foreign control would be easier. While true enough, these issues are not for this paper to deal with, only to mention.

The success of a pre-funded program would probably be judged by the extent of voluntary acceptance of it, and success would mean the endowment fund grows to be vast and well-distributed. Success would entail huge sums of money, potentially disruptive of the existing financial system. At peak capacity, the financial markets would have to absorb weekly inflows of about 1/4% of GNP, and eventually liquidations of double that size. Success might also entail a significant shrinkage of our oversized medical complex. Background churnings of that size would soon underlie every calculation in the markets, with uncertain consequences for what would probably be a steadily growing world financial marketplace, perhaps a disruptively international one. Not everything can be predicted so far in advance, but it is safe to say it would be tested for flaws until the markets conclude it is flawless, a very long time indeed. Such a Leviathan cannot be set on automatic pilot, but neither dare it relies on having the wisdom to make unblemished mid-course corrections. There are risks in attempting a middle approach, which must just be accepted as being less than the potential rewards of taking the risk.

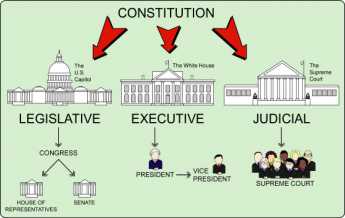

No Plan is Free of Risk; Long Range Planning is Political

In recent years, Congress has taken to producing laws of great complexity, sometimes thousands of pages long. This is particularly notable in the Obama administration but can be viewed as a non-partisan tendency throughout the Twentieth century, starting with Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. As part of the phenomenon, the workload of Congress has increased to the point where the Legislative branch is particularly weakened by its traditional procedures. The Executive branch has responded greatly enlarging itself, able to create most of the Law through regulation after the law is passed; and the Legislative branch reacts by creating excessive detail in later laws. This recipe for self-defeat has come to be called "micromanagement" by business theorists, who tend to view "command and control" as a solution. As long as the Constitution stands, that approach will not be allowed to work. It is not the purpose of this book to redesign government, or even to discuss it in detail. However, it is wise to remember that even good proposals are undermined by the change of circumstance. Unwisely freezing details when not truly necessary could defeat the main goal, which is to pay a large share of health costs with compound investment income.

The main goal is to pay a large share of health costs with compound investment income.

|

The main concern is this: our present or future systems of managing the currency may not permit compound interest to compound faster than inflation. That can't be blamed on the Health Care system, but it would certainly injure health care. At the present moment, long-term U.S. Treasury bonds pay 2%, but inflation reduces the value of the bond by more than that, perhaps 3%. Income tax reduces the value by perhaps 0.5%. The graduated income tax already makes it useless for the top quarter of the population to buy Treasury bonds, to say nothing of the top 1% of the population. Whatever the outlook for bonds, insurance companies must keep a large bond portfolio to pay claims. Whatever the outlook for stocks, a large stock portfolio is necessary to stay ahead of inflation. The public must not force its managers to ignore these rules in order to match the investment results of others.

Congress has responded to unrelated pressures by trying to collect the same taxes from a loophole-less tax code, primarily for the purpose of lowering the rates on the top bracket. Whatever the outcome of this struggle, it dramatizes that the usefulness of investing in bonds can readily be destroyed by modifying the tax code, by the stroke of a pen, as it were. You certainly would not want your lifetime health insurance to be risked by that sort of thing happening, sometime in the next eighty years, so you do not want the government to be too tightly in control of your investment portfolio. You may love your government, but its agenda is not necessarily in harmony with that of an insurance company.

Legislative extremes probably won't happen, because of the historic sensitivity of Americans to taxation. But inflation could be equally destructive, and control of that lies in the hands of an un-elected committee at the Federal Reserve. Much of this power was unintended, created by going off the gold standard, and then replacing it with the power of the Federal Reserve to issue (or, not issue) vast amounts of currency in response to "targeting" inflation at 2%. Since a casual observer has trouble seeing much of a match between 2% and the actual amount of currency issued, the Federal Reserve Chairman has been given wide latitude in adjusting interest rates for his own purposes. The outcome for present purposes is that a fifty-year history of this system would have allowed the following statement: "You could withdraw 4% a year from an investment fund, indefinitely, and still have the same amount remaining in the fund." In the past year, however, the following analysis emerged from David C. Patterson, the CEO of a very large investment fund: "A draw of 3% a year at any time since 1926 would only have resulted in a steady purchasing power 60% of the time." Whether this attack on a fundamental investing maxim was caused by inflation, going off the gold standard, or the actions of the Federal Reserve, it is a lesson that interest rates cannot be predicted eighty years in advance, within the boundaries of what experienced financiers considered safe enough to depend on.

The Bottom Line. The life insurance industry faces exactly the same problem, and if the life insurance industry has a solution, it hasn't made it public. What the life insurance industry surely has, is lobbyists. The solution they would devise doesn't necessarily address someone else's problem, but health insurance for the last year of life comes pretty close to what they do for funeral cost protection, so one could be confident they would be allies in any congressional manipulation of income tax upper brackets, to the disadvantage of investment funds. And the same thing could be said of the financial community. And the banking community, so one could be reasonably confident there would be plenty of allies against any overt congressional assault. That does leave the loopholes created in any plan by the unintended consequences of some other plan.

All in all, it seems the best strategy to begin with an investment fund which has already been authorized and given a tax exemption: the Health Savings Account. Put as much as you can in one and let it grow. Spend it for some health expenditure if you must, but anyone who puts in two thousand dollars at the birth of a grandchild is probably going to be glad he did, even though it might be left undeclared just how it would later be spent or disposed of. Walk a couple of blocks and open a debit card for the fund, and walk a few more blocks to a broker who can sell you a high-deductible health policy. Link these three features together when, and only when, some changed circumstances make it useful to link them in a single integrated system. If this direst of dire circumstances never comes about, you are no worse for leaving them independent. But if something bad does come about, you may possibly be motivated to change the basic arrangement, or even dissolve it and take your money out of it. Under really dire circumstances, your own ability to judge what is sensible is probably the best protection you can reserve for what is, at the best, a very dangerous world we live in. For far distant planning, it is necessary to rely on our form of government to produce leadership which can handle the problems.

REFERENCES

| The Game The Fed Plays With Your Investments | Wall Street Journal |

| The Federal Reserve And Financial Crisis | Amazon.com |

Comparatively Easy Financing for the Uninsured

|

| Paul Krugman |

Paul Krugman has been quoted as saying "Health Savings Accounts will increase the number of uninsured while benefitting only the wealthiest taxpayers." In fact, financing healthcare for the uninsured is pretty simple, if it would use Health Savings Accounts for pre-funded insurance. To do the very simple math (mind the zeroes, please), giving or loaning $5000 to 30 million uninsureds would cost a total of $150 billion dollars, or fifty billion a year for three years. By contrast, the annual deficit of Medicare alone is $250 billion. We'll get to the quibbles in a minute or two, but because most people aren't accustomed to dealing in numbers so large, let me introduce the jab that financing permanent health insurance for the uninsured would be quite a relief, compared with the unsustainable costs looming for the Affordable Care Act. The Federal Reserve currently spends $80 billion, every month, purchasing treasury bonds which perhaps few private investors should buy. The HSA subsidy cost would not be entitled to tax exemption, so it would actually be somewhat cheaper than $150 billion after-tax. This isn't a monthly cost we are describing or an annual one, it's a one-time expense, spread over three years.

To repeat the refrain, this one-time expense if invested would comfortably fund the average lifetime health costs of the uninsured population, except for one thing. The clients would have to buy a high-deductible health insurance policy (but only during the years the account is building itself up after being used), paying benefits in audited costs, not posted charges. People eligible for a subsidy would probably invade the fund for small expenses more than tax-sensitive people do so the statistics on existing use may be skewed. There would be startup administrative costs. State laws mandating small-cost items would have to be re-examined. Before all this cost shifting became popular with hospitals, the AMA offered its members a $25,000 deductible for $100 annual premium.

Yes, there would be an annual in-flow of new uninsured being born or imported, and so there would likely be a mechanism for recapturing the loan from those who move out of the subsidy category, structured so as not to act as an incentive to remain uninsured. No one can possibly predict future cures for disease or their cost/benefit, but that is true of any system. We hope the cures will increase and their costs will go down, but we certainly can't promise it. We can safely predict that reducing the cost of the uninsured would reduce everybody's liability for them, including the wealthiest. But also including minimum-wage earners, for whom a proportional reduction would be much more beneficial and welcome. And -- the 30 million recipients of this subsidy would undeniably be better off. It would, however, be entirely sensible to use part of any savings to reduce the national debt from earlier borrowings.

It would, however, be entirely sensible to use part of any savings to reduce the national debt from earlier borrowings. Furthermore, newspapers relate we have 7 million people in jail, and we steadily produce replacements when they are released. There is a constant inflow of new citizens mentally retarded enough they will never be self-supporting. The local school district where I live spends 8% of its budget on what it calls "special services for the mentally handicapped". The uninsured will always be with us. The American public is spending, and will always be spending, a great deal more on charitable healthcare than it gets credit for. We probably should be spending even more on these problems, but universal health insurance isn't going to do the job.

Without much doubt or dispute, the most serious problems with implementing this funding innovation would come from unanticipated effects, about which its opponents would be happy to expatiate without help from its proponents. In general, unanticipated effects begin to appear slowly, and if we remain alert, they may be minimized. But what about the unanticipated beneficial effects? If we really succeeded in wiping out the main causes of health cost, what then? Since an awful lot of people are employed within 17% of gross domestic product now spent, what in the world do we do with them if the expenditure is seriously reduced? Come to think about it, you really have me, there.

Increased Potential for Retirement Villages

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital, Nation's First Hospital, 1751 |