0 Volumes

No volumes are associated with this topic

Philadelphia Economics (3)

.

Locating Corporate Headquarters

|

| Troy Adams |

The Right Angle Club was recently entertained by a director of the Greater Philadelphia movement, Troy Adams. One of their main purposes of spending several millions of dollars annually is to try to attract new businesses to Philadelphia. The money, interestingly enough, is contributed by other businesses, many of whom would be competitors of the newly attracted ones. What's the value of this? How do you go about doing it, even if it is a splendid idea?

From the viewpoint of the city government, attracting new businesses means attracting new sources of taxation. It is not surprising therefore that the Chamber of Commerce tends to believe the main obstacle to attracting new business relocations is the tax structure of the locality. That's what the officers of companies under investigation ask about. By and large, the unattractiveness of Philadelphia to such inquiry is not the size of taxes, but their complexity. New businesses are turned off by learning of new types of taxes they had never heard of. It raises suspicion, and existing local businesses are quick to confirm that some of these strange-sounding taxes are objectionable mainly because you forget about them, and then get fined for not submitting a form to pay a small amount. If you get summoned to a hearing, it is even worse than paying the bloody thing. We have, say a lot of companies, branches in dozens of different cities, and we never heard of a tax like that. Of course, a famous sage once remarked that when someone complains it isn't the cost, it's the principle of the thing, well, it's the cost.

|

| Chamber of Commerce |

Regulations, requirements, prohibitions, deadlines, reporting requirements and all of that drive you crazy when you are trying to run a business. The cost of the taxes to a businessman is a simple question: do my competitors have to pay the same amount? If it's a level playing field, businesses ordinarily don't care about the money, since they can just raise the prices to the customer to cover it. Businesses, dear friends, don't look at costs the way the rest of us do. For that reason extended a little, businesses are strongly repelled by the existence of corruption, because corruption may or may not be applied equally, on a level playing field.

All of this sounded quite plausible to the Right Anglers until Buck Scott spoke up. " I beg to disagree, " he said. He remarked that in his experience the decision to move corporate headquarters to a city is determined by one person, or at most four. Whether the decision-maker is the CEO, a big stockholder, or a flunky assigned the task, the decision is usually not made on sensible economic grounds. It is based on the fact that the wife of the decision-maker grew up in Radnor or Chestnut Hill, and likes it here. If you are looking for access to ocean ports, railheads, Interstate Highways, airports, or proximity to big-city labor pools, Philadelphia has everybody beat. That sort of stuff is a given, and so what matters is that the decision maker wants to live here. To a certain extent, our proximity to New York and the District of Columbia is a handicap, since the lady of the family can live here while the corporate headquarters is not too far away, although too far away to be taxed. Buck Scott brought the discussion to a halt because it was obvious to everyone that he had a strong point.

.jpg)

|

| Philadelphia Ports |

On another level, however, there is still debate. The question is whether Philadelphia gains a great deal by having the corporate headquarters located here. The CEO may have invisible value by his socializing frequently with the CEOs of other corporations, but no one was able to defend that as having serious advantages. Since the competitive corporations are paying for this effort to attract new corporate headquarters to the region, there may well be advantages to them which are not immediately evident. What's clearly of value is locating large numbers of employees to the region, since they do generate business activity and hence taxes. Upscale companies have employees who are anxious to find good local schools, crime-free areas in which to live, and an improved environment; getting more of them into our voting pool will result in a better city, without question. Maybe, just maybe, locating the corporate headquarters in the region is a first step in enticing the rest of the company to come here. But it has not yet been demonstrated. Quite possibly, enticing the wives of decision makers to join the social whirl is the first step, and locating the factory here is only a secondary one which follows. Somehow, it begins to seem likely that the people who can influence one step, aren't talking to the people who determine the other.

Competitive Institutions: Paying for Assisted Living

Around the turn of the 20th Century, it was the fashion to build specialty hospitals, devoted to a single disease like tuberculosis or polio, or one specialty like obstetrics or bones and joints. Eventually, it was realized that almost any disease is handled better if a full range of services is readily available to it. Around 1925, some inspired philanthropists made it possible to combine specialties within a medical center, and it is now generally agreed this is a better way when population density permits it. On the other hand, it is likely a source of price escalation. Time marches on, and the problems of excessive bigness are also beginning to predominate. The idea immediately occurs, to winnow out the routine cases which do not need so much technology, so that we can concentrate and devote high technology (and costs) to patients who will really benefit. And, immediately the perplexing outcry is heard that such rationalization is "cherry picking", which will soon bankrupt the finest institutions we can devise. The validity of such assertions needs to be examined impartially.At the same time, the horse and buggy era has been left behind, causing new separations along class lines, the flight to the suburbs, and the migration of philanthropy toward the exurban sprawl, as well as into urban centers. In all this commotion it was overlooked for a long time that medical care was not merely following the patients to new locations, it was becoming more of an outpatient occupation. Inpatient care was shrinking, and somehow expensive hospitals were swallowing their smaller (and less expensive) competitors. It wasn't a necessary development; Switzerland still favors small luxury "clinics" of ten or twenty beds, usually containing wealthy patients of a celebrity doctor. Local customs like this will change slowly. What America appears to need is more hospital competition and more ambulance competition; the two may actually be somewhat connected issues. For amusement, I once studied the patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on July 4, 1776, when historical notables were congregating three blocks away. The diseases were remarkably similar to what is seen in hospitals today; problems with the legs, mental incapacity, major injuries, and terminal care. People are treated in hospitals because they can't care for themselves at home.

A BLUE-RIBBON COMMITTEE NEEDS TO STUDY INSTITUTIONAL COMPETITION IN HEALTHCARE.

This is a complicated issue and may take several years, or even several studies to sort out. What is useful for urban settings may be inappropriate in exurban ones; local preferences must be separated from special pleading, and that is not always easy. However, the continuing care center seems to be a permanent direction which is growing in popularity, as is also true of rehabilitation centers and retirement communities. Many of these institutions might incorporate doctors offices for their surrounding community, using the same parking facilities and many of the same medical specialties for both the neighborhood and the core facility. There seems no reason to oppose either rentals or private condominium-style ownership nor any reason to resist group clinics. Exclusive arrangements, however, are more questionable. All of these arrangements should be studied, and unexpected problems flushed out. No doubt the preliminary studies would lead to pilot and demonstration programs. And some practices which initially seem harmless, should in fact be prohibited. We have a lot to learn before we start overturning the existing order. But nevertheless, some arrangements will prove to be superior to others, almost all of them are regulated in some fashion, and the regulations should be examined, too. It should accelerate needed changes to know in advance which ones are ready to be tested, and tested before they are demanded.

*******

.jpg)

|

| CCRCs |

Everyone knows Americans are living thirty years longer because of improvements in health care, and some grumpy people are waiting with glee to see if Obamacare will put a stop to that sort of thing. It must be left to actuaries to tell us whether the nation saves money or not by delaying the inevitable costs of a terminal illness. But one consequence has already made its appearance: people are entering retirement villages in their eighties rather than their seventies. Presumably, people in their seventies are feeling too well to consider a CCRC, although other explanations are possible.

Accordingly, a great many CCRCs are seen to be building new wings dedicated to "assisted living". A cynic might surmise there must be some hidden insurance reimbursement advantages to doing so, but the CCRCs are surely responding to some kind of increased demand when they make multi-million dollar capital expenditures. Assisted living is a polite term for people with strokes or Alzheimers Disease, or some other condition making it hard to walk, or, as the grisly saying goes, perform the activities of daily living. One really elegant place in Delaware has suites with servants quarters, but for most people, the only affordable option is to be in a room designed around the idea of assisting an invalid. It's generally smaller and more austere but fitted out with railings and bars and special knobs. Meals generally have to be supplied by room service.

Not everyone is destined to have a protracted period of decline, but it's fairly frequent and universally feared, so it's a comfort to know your present residence is attached to a wing which provides for it. The question is how to pay for it. There are two main approaches currently in use, adapted to the limited financial resources of the aged and the particularities of CCRC arrangements.

In the first arrangement, there is no increased charge for moving to assisted living, which helps overcome resistance to going there. However, the monthly maintenance charge for others who remain behind in "ambulatory living" is increased, usually about 20%, to provide funding for those who eventually need special assistance. That's a financial pooling arrangement, sort of an insurance plan, and like all insurance, it has a tendency to increase usage unnecessarily. It also increases the cost to those who enter the CCRC at an earlier age, because they make more monthly payments before they use them. Although the monthly premium probably goes up as the costs rise with inflation, there may be some savings hidden in applying an earlier payment stream at a lower rate. That's called "present value" accounting, but like just about all accounting, its unspoken advantages and disadvantages contain a gamble on unknown future inflation.

In the other common financial arrangement, you pay as you go, when and only if you actually use the assisted living quarters. Because of the likely limit to resources, there is usually an attached agreement to garnishee the initial entrance deposit if available funds prove insufficient. The one thing which won't happen is being thrown out in the snow for non-payment; there's a law prohibiting that. Bigger apartments with large initial returnable deposits are of course better off paying list prices. Those with smaller apartments may have smaller deposits, and favor payment by a percent withdrawal. Some places haven't thought this through and offer no choice. In that case, more attention should be paid to those list prices and the percentage markup from audited cost. Better still is to have a free choice of both options, with cost transparency.

The remaining choice is between two CCRCs with differing options, made at the time you enter. The Obamacare fuss has made a lot of people acquainted with "adverse risk selection", which is largely based on the idea that an individual has a better idea of his health future than an institution does since that includes family history as well as earlier health experiences. But in general, a young healthy person is going to live longer without needing assisted living than an old geezer who going to need it pretty soon. A hidden adverse incentive is created for younger healthier people to set the choice aside, and come back in ten years, providing they remain alert to the underlying reason the monthly fee is then somewhat higher than in some competitive CCRC. At the far end of the age spectrum, an incentive is created to go into assisted living quarters a little earlier in life, generally regarded as an undesirable choice.

All this financial balancing act can seem pretty overwhelming to an elderly person who isn't entirely comfortable with the CCRC idea in the first place. Rest assured that everything has to be paid for somehow, and after you die you won't care what choice has been made. If you trust the institution to have your best interests in mind, the only consideration of real importance is whether your money will last you out. The institution cares about that even more than you do, so while they aren't likely to offer unrealistically bargain choices, they may offer a few which are too costly.

America has had a ninety-year romance with insurance because it is so comforting to be secure and oblivious to finances. This is just another example of the struggle between the search for a security, and the struggle to devise ways to pay for it. While no one can be positive about it, we're all in this together.

Foreground: Parliament Irks the Colonial Merchants

|

| Charles Townshend |

Charles Townshend, Chancellor of the Exchequer under King George III in 1766-67, had a reputation for abrasively witty behavior, in addition to which he did carry a grudge against American colonial legislatures for circumventing his directives when earlier he had been in charge of Colonial Affairs. His most despised action against the Colonies, the Stamp Act, seems to have been only a small part of a political maneuver to frustrate an opposition vote of no confidence. The vote had taken the form of lowering the homeland land tax from four to three shillings (an action understood to be a vote of no confidence because it unbalanced the budget, which he then re-balanced by raising the money in the colonies.) The novelist Tobias Smollett subsequently produced a scathing depiction of Townshend's heedless arrogance in Humphry Clinker, but at least in the case of the Stamp Act, its sting was more in its heedlessness of the colonies than vengeance against them. One can easily imagine the loathing this rich dandy would inspire in sobersides like George Washington and John Adams. After Townshend was elevated in the British cabinet, almost anything became a possibility, but it was a fair guess he might continue to satisfy old scores with the colonies. When King George's mother began urging the young monarch to act like a real king, Townshend was available to help. On the other hand, the Whig party in Parliament had significant sympathy with the colonial position, as a spill-over from their main uproar about John Wilkes which need not concern us here. Vengefulness against the colonies was not widespread in the British government at the time, but colonists could easily believe any Ministry which appointed the likes of Townshend might well abuse power in other ways before such time as the King or a more civilized Ministry could arrive on the scene to set things right. It was vexing that a man so heedless as Townshend could also carry so many grudges. Things did ease when Townshend suddenly died of an "untended fever", in 1767.

Whatever the intent of those Townshend Acts, one clear message did stand out: paper money was forbidden in the colonies. Virginia Cavaliers might be more upset by the 1763 restraints on moving into the Ohio territories, and New England shippers might be most irritated by limits on manufactures in the colonies. But prohibiting paper money seriously damaged all colonial trade. Some merchants protested vigorously, some resorted to smuggling, and others, chiefly Robert Morris, devised clever workarounds for the problems which had been created. Paper currency might be vexingly easy to counterfeit, but it was safer to ship than gold coins. In dangerous ocean voyages, the underlying gold (which the paper money represents) remains in the vaults of the issuer even if the paper representing it is lost at sea. Theft becomes more complicated when money is transported by remittances or promissory notes, so a merchant like Morris would quickly recognize debt paper (essentially, remittance contracts acknowledging the existence of debt) as a way to circumvent such inconveniences. In a few months, we would be at war with England, where adversaries blocking each other's currency would be routine. By that time, Morris had perfected other systems of coping with the money problem. In simplified form, a shipload of flour would be sent abroad and sold, the proceeds of which were then used to buy gunpowder for a return voyage; as long as the two transactions were combined, actual paper money was not needed. Another feature is more sophisticated; by keeping this trade going, short-term loans for one leg of the trip could be transformed into long-term loans for many voyages. Long-term loans pay higher rates of interest than short-term loans; it would nowadays be referred to as "riding the yield curve." This system is currently in wide use for globalized trade, and Lehman Brothers were the main banker for it in 2008. And as a final strategy, having half the round-trip voyage transport innocent cargoes, the merchant could increase personal profits legitimately, while cloaking the existence of the underlying gun running on the opposite leg of the voyage. If the ship is sunk, it can then be difficult to say whether the loss of such a ship was military or commercial, insurable or uninsurable. In the case of a tobacco cargo, the value at the time of departure might well be different from the value later. Robert Morris became known as a genius in this sort of trade manipulation, and later his enemies were never able to prove it was illegal. Ultimately, a ship captain always has the option of moving his cargo to a different port.

Other colonists surely responded to a shortage of currency in similar resourceful ways, including barter and the Quaker system of maintaining individual account books on both sides of the transaction, and "squaring up" the balances later but eliminating many transaction steps. Wooden chairs were also a common substitute as a medium of exchange. But "Old Square-toes," Thomas Willing, experienced in currency difficulties, and his bold, reckless younger partner Morris displayed the greatest readiness to respond to opportunity. Credit and short-term paper were fundamental promises to repay at a certain time, commonly with a front-end discount taking the place of interest payment. The amount of discount varied with the risk, both of disruption by the authorities, and the risk of default by the debtor. This discount system was rough and approximate, but it served. Quite accustomed to borrowing through an intermediary, who would then be directed to repay some foreign creditor, Morris, and Willing added the innovation of issuing promissory notes and selling the contract itself to the public at a profit. Thus, written contracts would effectively serve as money. A cargo of flour or tobacco represented value, but that value need only be transformed into cash when it was safe and convenient to do so.

The Morris-Willing team had already displayed its inventiveness by starting a maritime insurance company, thereby adding to their reputation for meeting extensive obligations; they established an outstanding credit rating. Although primarily in the shipping trade, the firm was also involved in trade with the Indians. There, they invented the entirely novel idea of selling their notes to the public, essentially becoming underwriters for the risk of the notes, quite like the way insurance underwriters assumed the risk of a ship sinking. Their reputation for ingenuity in working around obstacles was growing, as well as their credibility for prompt and reliable repayment. In modern parlance, they established an enviable "track record." A creditor is only interested in whether he will be repaid; satisfied with that, he doesn't care how rich or how poor you are. The profits from complex trading were regularly plowed back into the business; one observer estimated Robert Morris's cash assets at the start of the Revolution were no greater than those of a prosperous blacksmith. It didn't matter; he had credit.

In the event, this prohibition of colonial paper money did not last very long, so profits from it were not immense. But ideas had been tested which seemed to work. Today, transactions devised at Willing and Morris are variously known as commercial credit, financial underwriting, and casualty insurance. In 1776, Robert Morris would be 42 years old.

Black Swans (Financial Variety)

|

| Nicolas Baudin |

The mouth of the Delaware River once teemed with white swans, but black swans were unknown until the French explorer Nicolas Baudin brought home a few from Australia, where they are now celebrated as the state animal of Western Australia. Empress Josephine Bonaparte was delighted with them, made them known as her birds, and thus made the term "Black Swan" more or less synonymous with rare chance occurrences. The implied inference that every white swan contains a remote potential for breeding a black one is doubtful biology, however. More likely, black swans are a distinct species -- Cygnus atratus-- confined to Australia and New Zealand, and just about extinct in New Zealand. In that view of things, the rarity of black swans is equivalent to the prevalence of black ones, mixed within the population of generally white ones. Nevertheless, for this article, it is convenient to continue the unlikely conjecture that most, or perhaps every, white swan contain a small potential to hatch a black one.

|

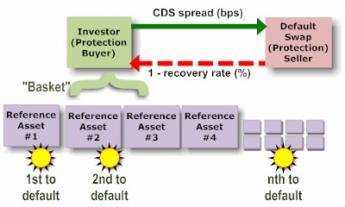

| Credit Default Swaps |

Many theories exist for the discovery that financial crises are commoner than chance alone would seem to predict; if they follow a Gaussian normal distribution curve, it must be somehow different from the distribution curve of smaller fluctuations. Observing this discordance is more or less how the phenomenon was discovered. The normal volatility of economic activity is calculated from the fluctuations observed in, say, twenty years. When that derived curve is extrapolated to include cataclysmic events which by a theory of the unmeasured "long tail" occur every hundred years, speculators have later discovered by actual measurement that, alas, such disasters actually occur much more frequently. Calculated risks derived from such extrapolations have upended many insurance companies and insurance-like vehicles like Credit Default Swaps, who set their premium charges to match the mathematics. Since CDS approached a hundred trillion dollars in the last crisis, it is important to understand the mechanics of this kind of Black Swan if we possibly can.

|

| Black Swan |

One way to do that is to question the conventional equivalence of risk and volatility ; that is, that the more markets bounce around, the riskier they become. Why should that be true, we might ask. And if it is somewhat true, why does that make it is converse true, those calm seas are safe ones? Those of us who sit and watch the ocean shore soon adopt the habit of speech that high waves at the shore mean a storm is approaching, not that it will ever arrive. After all, the center of the storm may be traveling parallel to the coastline, not directly toward it. And calm seas are particularly undependable predictors; no matter how calm it may be, the next storm might arrive in a few hours, or it may not come for months. Many other analogies spring up, once one puts aside the basic assumption that world economies can be depicted as a linear electrocardiogram. At the very least, they are two-dimensional, possibly three. Possibly four, if you regard time as a dimension.

|

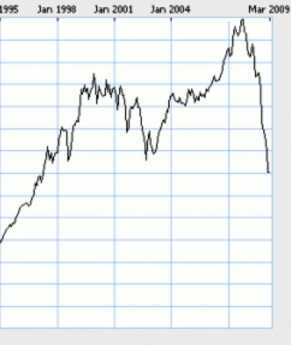

| Dow Jones |

It must be noticed that market volatility is universally viewed as linked to bad things, and many efforts have been made by central banks to reduce risk by constraining volatility. Alan Greenspan is famous for having controlled the economy for seventeen years without major depression. Is that necessarily a good thing? Is it equally possible that kinetic energy was constrained within the inflating balloon until the bursting of it was a far more damaging explosion than small planned deflations would have been?

Experimental testing of these ideas has itself been constrained by an inability to predict the explosion point of expanding financial balloons. Planned deflations have been particularly feared, because of lack of assured ways to get them to stop deflating. But practical warnings such as these are not the same as claiming that lack of volatility is always the ideal state.

Politics of Employer Hiring Preferences

|

| Interview |

To a remarkable degree, employees tend to remain in either the nonprofit or for-profit sectors of the economy for a lifetime. A prospective new employer naturally wants to know about previous work experience so it is natural enough to poke around for clues. An interviewer may just be jumping around when most questions are fired at a prospective new hire, but this one is hard to dodge.

Whether it is a reasonable position or not, almost everyone on both sides of the interview desk has the impression that for-profit employers prefer to hire people with experience in the for-profit sector, and the reverse is true for non-profits. So far, so good; experience in related fields is an attractive feature. But going considerably beyond favoring prospective employees with related experience, there is a general impression that experience in the other sector has a curse attached, reducing the chances of being hired. When an impression is this widespread, it no longer matters whether it is sensible. Make the wrong answer, and you don't get the job; that's reason enough. And it's equally true in both sectors, so the workforce segregates pretty quickly.

It's plainly true that the for-profit sector votes Republican, the non-profit sector registers, votes and talks pro-Democrat. Since young people usually vote for Democratic candidates, it seems to follow that party-switching is mainly in the direction of young Democrats becoming Republican after a few years of employment, although the reverse is seen when young residents of farm communities move to the city, with college sandwiched in-between.

Going to college may not be exactly like being employed by a college, but it's close enough. The faculty are in a similar power relationship to students as a boss is to employees, in command, but also portraying a role model and parent-figure; it is axiomatic that students emerge from college more liberal-leaning than they entered. It's beyond challenge that college faculties are the most liberal-leaning group in America; their institutional employers are all in the non-profit sector to some degree. As long as government research grants, scholarship grants, construction subsidies (and indirect overhead allowances) continue to dominate the finances of higher education, the allegiance of all colleges and universities will belong to the party so proudly representative of non-profit principles. Professor Gordon S. Wood of Brown University has propounded the theory that the 18th Century concept of a gentleman had three distinctive features: he didn't need to work, he deplored aggressive money-making, and he went to college. Americans dislike the concept of the aristocracy, but they strongly favor playing the role of a gentleman. It's as good an explanation as any.

Future trends are of course hard to predict, but since the proportion of the population going to college is steadily increasing, there is a strong force in the direction of continuing to strengthen the Democratic party. But since taxes derived from the for-profit sector are the ultimate source of all non-profit revenue, some strong push-back from present trends also seems inevitable.

Relocation

|

| Moving Truck |

For many decades, at least since the Second World War, the Northeastern part of the country has been losing population. And business, and wealth. In recent years, New Jersey has been the state with the greatest net loss, and the Governor who is making the greatest fuss about it. Statisticians have raised this observation to the level of proven fact, although lots of people are even moving into New Jersey at the same time. This is a net figure, and it remains debatable what sort of person you would want to gain, hate to lose; so it's hard for politicians to be certain whether New Jersey's demographic shifts are currently a good thing or a bad thing.

Take the prison population, for example. Most people in New Jersey would think it was a good thing if the felons all moved to some other state because it would imply less crime and law enforcement costs. But one of the major recent causes of a decline in violent crime seems to be the universal presence of a portable telephone in everyone's pocket. Just let someone yell, "Stick 'em up!" loud enough, and thirty cell phones are apt to emerge, all dialing 911. On the other hand, cell phones are the universal communication vehicle for sales of illicit drugs and other illegal recreations, and the increase in automobile accidents is a serious business for inattentive drivers. Add to this confusion the data that capital punishment is more expensive for the State than incarceration is, and you start to see the near futility of knowing what is best to have more, or less, of.

What the Governor and his Department of Treasury mostly want to know is whether certain taxes end up producing a good net revenue for the State. That is, whether more revenue is produced by raising certain taxes more than others, or whether some taxes are a big component of the Laffer Curve, causing revenue to be lost by driving business, or business owners, out of state, in spite of the immediate revenue gain. The studies which have been done are fairly conclusive that executives tend to be most outraged by property taxes, since they have a hidden effect on the sale price of the house, and the amount of money available for school improvements. At least at present levels, a Governor is better off taking abuse for raising income or sales taxes, even though the apparent tax revenue might be the same as a rise in property taxes. Since property taxes are mostly set by a local municipal government, while sales and income taxes are usually set by state governments, a decision to raise one sort of tax or another can have unexpected consequences, or require obscure manipulations to accomplish.

Some politicians who believe their voting strength does not lie in the middle class, would normally want to hold up property values, not taxes because the data show that higher home prices drive away from the middle class and in certain circumstances are positively attractive to wealthy ones. Higher prices appeal to home sellers, at least up to a point. Wealthier people who are buying houses are likely to have an old one to sell; that's less true of first-time home buyers or people presently renting. Certain issues can even be reduced to rough formulas: a 1% increase in income tax would cause a 1% loss of population, but a 5% loss of people earning more than $125,000. A $10,000 increase in average home prices, on the other hand, causes a net loss of population, but mostly those with lower income. One important feature of tinkering with average home prices and property taxes is that these effects are "durable" -- they do not fade away over time.

|

| Laffer Curve |

New Jersey is financially a bad state to die in, but the decision to move to Delaware, Florida or Texas is often made over a long period of years in advance of actually doing it. It has been hard to compile statistics relating changes in inheritance tax law to net migration of retirees and to present such dry data in an effective manner to counteract the grumblings that rich people are undeserving of tax relief, or dead people are unable to complain. But rich old folks are very likely to own or control businesses, and if you drive them out of state, you may drive away a considerably larger amount of taxation relating to the business in other ways. This is the underlying complaint of Unions about Jobs, Jobs, Jobs; but state revenue also relates to sales taxes of the business, business taxes, employee taxes, real estate taxes on the business property, etc, etc. Sometimes these effects are more noticeable in the region they affect; the huge population growth of the Lehigh Valley in recent years is mainly composed of former New Jersey suburbanites, who formerly earned their income in New York. The taxes of three different states interact, in places like that.

The audience of a group I recently attended contained a great many people who make a living trying to persuade businesses to move into one of the three Quaker states of the Delaware Valley. The side-bar badinage of these people tended to agree that many of the decisions to relocate a business are based on seemingly capricious thinking. The decision to consider relocation to the Delaware Valley is often prompted by such things as the wife of an executive having gone to school on the Main Line. Following that, the professional persuaders move in with data about tax rates, average home prices, and the ranking of local school quality by analysts. Having compiled a short list of places to consider by this process, it all seemingly comes back to the same capriciousness. The wife of the C.E.O. had a roommate at college who still lives in the area. And she says the Philadelphia Flower Show is the best there is. So, fourteen thousand employees soon get a letter, telling them we are going to move.

And, the poor Governor is left out of the real decision-making entirely, except to the degree he recognizes that home property taxes have the largest provable effect on personal relocation. And lowering the corporate income tax has the biggest demonstrable effect on moving businesses. But the largest un-provable effect is dependent on the comparative level of the state's inheritance tax.

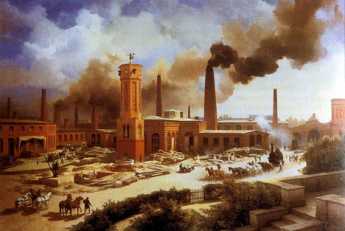

Who Killed Philadelphia Industry?

|

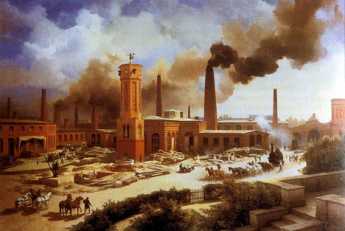

| The Industrial Revolution |

The term "Rust Belt" makes clear that Philadelphia is only one city in a whole region which lost its industrial core. The Industrial Revolution surely isn't over, it has moved. When we had too much of it, we deplored the smoke and fog of industry, its acid rain, its grimy desolation. But now that industry has obliged us by departing, we miss it, if for no better reason than it imposed structure on the city. It was the organizing principle, which we now need to replace with something more than the dreams and sketches of architects and planners. Figure out what we want the city to be, or at least try to figure out where it is going. And then, the city will shape itself. Philadelphia is far from the worst afflicted city in the region; compared with Detroit, it was hardly affected. What determines relative success within regional decline is whether a city has other assets, sufficient to create substitute routes to success. In Philadelphia's case, non-profit activity provided survival, but the avoidance of profits soon became altogether too praiseworthy.

My friend the railroad lawyer gives an unexpected answer to the question why we no longer have much industry in Philadelphia. The cause, in his wry phrase, is air conditioning. Not even Congressional logrolling would have been able to push industry into Huntsville, Alabama or even Atlanta, without air conditioning to make those places inhabitable. He jests. The South has developed the infrastructure to take its place in the industrial world and has a lower wage scale at all levels of society. The Second World War stirred them out of their provincialism, the GI Bill educated them. And let's face it, the migration of their black people from the rural south to the urban north reduced the strain on southern education and welfare, at the same time it imposed much of that burden on the haughty Civil War victors. There had been a massive migration westward of the white South, fleeing the devastation of the Civil War; but the blacks didn't much participate in that. Their migration from the former slave states came by the busload after the end of World War II.

We focus on the newly industrialized South as a competitor because it is more personal; we know the cities of the South and Southwest are growing rapidly, and we have a fair idea of who is moving there. Meanwhile, the rest of the underdeveloped world is flowering, economically developing, at a far faster rate. Over a billion Chinese and Indians have been lifted out of unspeakable poverty and transformed into serious economic competitors. Air conditioning sort of gets the idea across. But the word we are searching for is -- globalization. Philadelphia is a perfectly wonderful place to live, particularly if you are able to retire here. What we lack is a sustainable way to earn a living.

It took the destruction of eight railroads to break the back of the industrial unions. The union movement has shifted to the public sector by exploiting a highly dubious partnership with urban political machines. This sort of thing must not be permitted to continue unresisted, if only to avoid the example of New Jersey with the apparent invasion of politics by the Mafia entering by way of union politics, maybe by way of the legalized gambling industry. It requires no advanced degree in economics to see that aggregation of non-productive sectors into a political force is incompatible with success in a globalized world. Foreign competitors will destroy businesses which yield, and the bond market will teach the public sector a bitter lesson.

Globalization did not destroy the Rust Belt, it simply gave a shove to a tottering structure. By the 1920s, our industries had enjoyed their expected seventy-five-year life span; the 1929 crash was a belated recognition of the facts. The ensuing Depression and World War II protected our obsolete industrial plant from foreign competition, but by 1960 our monopoly was under attack by modern new factories abroad, enjoying cheap labor, copying our methods. In what has proved to be the most astute investment judgment of a century, the DuPont family perceived the facts and sold General Motors, just as they had earlier given up the gunpowder business to make nylon stockings. It would be exaggerated to say that political subsidies kept the auto business alive for another forty years after the duPonts got rid of it, but that would appear to be approximately true. The seller of any business is in position to foretell its future better than most buyers and is looking for top dollar to dress it up and cash out.

We thus arrive at the conclusion that no one in particular killed Philadelphia industry, at least to the extent it is unproductive to search for villains. My friend the lawyer feels maritime unions were more guilty than other unions, and he has no reason to love railroad unions. But if it can be accepted that Philadelphia's main problem was to fail to replace aging industries with new ones, the more productive search lies among correctible obstacles for new businesses. Since globalization has apparently resulted in Philadelphia's impaired competitiveness for untrained and uneducated workers, it would seem most productive to educate more of them up and out of that class. Our clearly dysfunctional public school system must either be improved or radically revised; the teachers' unions seem to be a serious problem to address. For some reason, the most serious problems appear in the fourth grade.

|

| Father Time Baby New year |

Our criminal justice system seems to be in a circular pattern which must be broken. We spend too much on police, prisons, and courts, to the point where convicted criminals exceed the prison capacity, and courtroom procedures seem designed to avoid convictions. Our local judges are a national joke, with an excessive tendency to settle cases out of an inexperienced judge's fear of his own inability to conduct a trial. In fact, the chief justice of our state supreme court is presently accused of corruption in the location of the family courts. Apparently much could be accomplished simply; the number of liability filings is down over 50% in a few years, simply by a few changes in civil procedures. Increasingly, lawyers are turning to alternative dispute resolution under private auspices. Apparently, litigants on both sides find it preferable to pay for private judging than to utilize the free judging provided by the Commonwealth. Surely, both the law schools and the bar associations are derelict in their implicit duty to guide the public through this arcane labyrinth. Perhaps the solution, and maybe the source of the problem, is to be found in the State Legislature.

The Legislature, now there's a piece of work. Between the gerrymandering they create and the single party urban machines which command their nominating primaries, it is hard to believe a reform movement can have more than transient effect, or that a tea party could unite around an effective solution. Proposition Fourteen in California (open, non-party primaries) is a promising idea, but probably it will not be possible to amend the state legislative process with a single stroke, and then everybody could go home. This project seems more likely to require large private contributions to multiple in-depth studies of the history and intricacies of the local governance problem, together with a series of tentative steps and revisions over at least a decade. Perhaps a portion of the money now being spent purchasing and trading professional sports teams could be diverted to generating the ideas and research, maybe the publicity, required to accomplish such an ambitious project. But for a beginning, Proposition Fourteen has the right idea; politics keeps its stranglehold on reform through iron control of the nominating process.

In addition to cleaning up the governance mess, we need to look at the industries we have driven away, to see how to mend our ways.

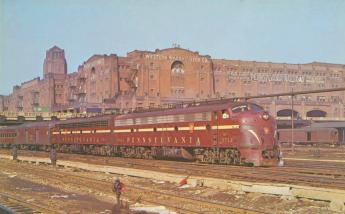

Africa Comes to the Schuylkill

A journalist, John Ghazvinian, recently toured the many countries of Africa, wrote a book about it and carried his message to the Right Angle Club of Philadelphia. Philadelphia does not think of itself as particularly involved in oil matters, or African ones. But the fact is the refineries on the Schuylkill down by the airport generate two-thirds of the gasoline now used on the East Coast, and right now it mostly comes from Nigeria. There was a time when the crude oil coming to Philadelphia came from Venezuela, but politics are a little unpleasant there at present, and anyway Venezuelan oil is heavy and full of acids. The refineries which specialize in that kind of heavy oil are on the Gulf Coast. Long before the Venezuelan era, the Philadelphia refineries were constructed to refine crude oil from upstate Pennsylvania. They were once the main source of the dominance of the Pennsylvania Railroad, because oil refining from Bradford County gave the Pennsy a return freight, whereas the competitive railroads running out of New York and Baltimore had to return from the West without cargo.

|

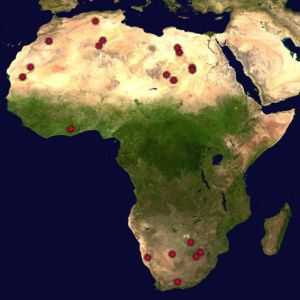

| African Map |

There are 54 countries on the continent of Africa, quite different from each other in character. One dominant characteristic of Africa is its lack of natural ports, and even the Mediterranean ports are cut off from the rest of the continent by the huge transcontinental stripe of Sahara desert. Major wars and famines, monstrous genocides, unspeakable cruelty, and poverty go on there without much notice by the rest of the world.

The largest country in Africa is Nigeria. Anyone with even minor dealings with Nigeria soon sees that corruption and dishonesty pass all Western imagination, and they have serious tribal warfare as well. The discovery of large deposits of oil in the region faced the international oil companies with a rather serious difficulty. For instance, Shell Oil has had over 200 employees kidnapped for ransom and is seriously contemplating abandoning its whole venture. At the moment, corruption is coped with by constructing oil wells a hundred miles out in the ocean.It's almost true that the huge tanker ships make from Philadelphia and return, without the crew talking to any natives of Africa.

We hear that genocide is in full bloom in the Sudan, and that poverty in that country similarly passes belief.

|

| Chad Poverty |

They have oil in the South of Sudan so we may hear more of it. Chad has poverty and oil, and civil war. They have a big Exxon facility, but there isn't a single gasoline station in Chad. At the moment, Angola has paused in its enormous civil war, which killed millions, and Chevron will surely encounter unrest before it is done. Gabon appears to be extremely prosperous, from oil money of course, but they are being ravaged by the Dutch Disease, of which more later.

Apparently, Equatorial New Guinea sets some sort of record for wild behavior. It has lots of oil, and a strong Chinese influence. The current

|

| Mbasogo and Jintao |

President of Equatorial New Guinea got his job by shooting his uncle. But don't feel too sorry for the uncle, who used to have an annual Christmas morning celebration, consisting of herding his enemies into a football stadium, and shooting them for the edification and entertainment of the populace. After listening to Mr. Ghazvinian, it seems small wonder that so few American tourists, or journalists, or even missionaries, manage to complete extensive African excursions. As everyone notices, if you don't have journalists, there is never any news.

Let's turn to the Dutch disease,

|

| David Ricardo |

of which Africa currently displays many examples likely to torment economics students for decades after Africa eventually rivals Houston. Let's start with David Ricardo, who electified the Nineteenth Century world of economics with his principle of comparative advantage. Ricardo pointed to the obvious truth that always and everywhere a nation does best for itself by identifying its best economic feature and then sticking to it. If every country wakes up and does that, every country must then trade with its neighbors for other things it isn't so suited to make. Consequently, tariffs and trade barriers are a hindrance for everyone, in time impoverishing all nations in the cycle, whatever short-run advantages of tariffs may seem enticing.

|

| North Sea Gas |

So far as I know, Ricardo was quite right, but someone had better hurry up and reconcile his underlying premise of comparative advantage with the Dutch Disease. The Dutch disease was identified and named by an anonymous writer for the London Economist about thirty years ago. Noticing that the Netherlands experienced a marked worsening of its general economy after the discovery of North Sea gas deposits, the observer for the magazine concluded that sudden accumulation of wealth in the gas industry led to a rise in the value of the Dutch currency, soon making it impossible for non-gas industries to export, unable to compete at home with now-cheaper foreign imports. Naturally, investors rushed to invest in gas, sold their holdings in other industries, and Holland was propelled in the direction of a one-industry economy, quite at the mercy of fluctuating prices of gas. This was the Dutch Disease born, and Ricardo's principle of comparative advantage exposed to quite a severe challenge from which it has not completely recovered. This is important, so how about a simpler description: When gold is discovered, people drop tools to have a gold rush. Wealth lost from dropping tools is greater than wealth gained from the gold.

Fear of the Dutch disorder seems to be the reason why the Chinese are buying our Treasury Bonds, the Japanese engaging in the astonishing "carry trade," and the Arabs buying American private equity funds. The common strand through all these schemes is this: By sending their bonanza savings abroad, they "sterilize" them from their tendency to force their currency upwards. They are exporting inflation, but also endangering their own struggling non-bonanza industries, which are the main hope for diversifying their economies and getting rid of the Dutch effect. Somewhere during this balancing act, politicians get involved and make things worse. So they call in their generals and admirals, to explore solutions we prefer they were not in a position to explore. Simpler description: When you discover oil, inflation soon follows. And all too often, revolution follows that.

The 1787 the American Constitution unknowingly cured thirteen cases of the Dutch Disease, by imposing absolute freedom of interstate commerce. After eighty years, the benefits of this national union would persuade the North to bleed and die for it. Although the Confederacy thought they were fighting for their way of life, meaning slavery, even the Southerners today recognize they are better off in a Union. Unfortunately today, the European nations are still having a hard time believing the benefits of union could possibly outweigh their allegiances to language, religion, and the wartime sacrifices of their ancestors. They are very wrong, but we are wrong to sneer at them. Except for maybe Switzerland, it is difficult to name another instance in all of history where several independent states gave up local sovereignty for the benefits of a diversified economy with local pockets of comparative advantage. Let's restate it again: the Dutch disease is a result of sudden single-industry prosperity in a country too small to control it.

By the way, what eventually happened to the Dutch? It seems likely that absorption of little Holland into the European Common Market helped dilute the corrupting effect of gas prosperity. It suggests the possibility that Dutch can be reconciled with Ricardo through the common denominator of reduced national barriers to trade and currency-- reduced sovereignty in a milder form. But it's a hard slog. Maybe we could envision annexing Alberta to soften the commotion of oil tar, but it takes a lot of imagination to see the amalgamation of China and India, any time soon. There may thus be nations too big to merge, but nevertheless, it would probably be less destabilizing to merge with all of Canada than just with Alberta if you overlook the obvious fact that it is easier to persuade a small country than a big one. Just kidding for the sake of example, of course, since Canada shows no interest in the idea.

Meanwhile, take a look backward from the highway overpass the next time you travel to the Philadelphia Airport. There's a lot more going on in those refineries than just black liquid flowing into steel pipes.

Breaking the Buck

|

| Walt Bettinger |

WHEN mysteriously crashing financial markets caused transactions to freeze in terror in 2008, no one was brave enough to explain what had happened, because no one was sure. It had happened before and in many nations, but no comprehensive theory was acknowledged to exist for all such crises, and certainly no coherent explanation existed for this one. That is an assessment some people might dispute, of course. But during the worst of the crisis, chairmen of major financial houses, professors of economics, and assorted other notables were asked by the news media to explain the situation, and most of them confessed they really didn't know. As the crisis continued, tentative partial explanations were offered, and eventually, political partisans or competitors were emboldened to assign blame to indignant participants in various financial trades, apparently using the logic that if no one really knew the answer, then everybody was permitted to offer one. Gradually, however, some serious theories have been announced, along with reasonably credible evidence, but no more than that. After the dust had settled somewhat in November 2012, Walt Bettinger published an article in the Opinion pages of the Wall Street Journal which plausibly helps explain a piece of it.

Mr. Bettinger is the CEO of Charles Schwab Corp., which owns several large money market funds, and he credibly offers a theory about the money market part of it. Briefly, it is that large institutions with both sizeable investments in money market funds, as well as strong computer and mathematical resources, were in a position to withdraw their investments during the days of chaos, whereas smaller public investors have to wait until the end of the trading day to learn that a fund had abruptly developed too few assets to justify paying out a dollar for every dollar's worth of obligation. That is, in a "mark to market" situation there weren't enough reserves to cover the liabilities. If the public became aware of this situation, it might suddenly withdraw its deposits and throw the fund into bankruptcy; that is, it might start a run on the bank. In the past, this sort of thing has happened to money market funds from time to time, and the institution which owns or sponsors the money market fund has -- so far -- supplied its own money to prevent potential disaster from a bank run. However, in a serious crash with uncertain causes, someday that might not be their choice or their assets might not be sufficient to stop the run. The consequences are uncertain, but the dangerous potential is clear.

|

| Chuck Schwab |

The remedies for this situation might well be numerous, but the simplest one would be to isolate large investors from small ones by setting a top limit for large accounts, perhaps even automatically transferring large accounts to a large-account fund at the instant the account exceeds some limit. Apparently, similar proposals have been made privately, and there is opposition whose validity must be addressed. However, in the confines of an Op-ed article, a fully exhaustive discussion of a technical proposal is not possible. Ideally, this sort of proposal could be adopted privately, using the advance consent of the two involved parties, the bank, and the big customer. No doubt there is some legitimate concern that widespread publicity might trigger unfortunate legislative over-reaction. After all, most members of the public are unaware that "breaking the buck" is even a possibility. If the possibility of a run can be eliminated by skipping the alarming discussion of whether it potentially exists, or how serious it might or might not become, it would be a mercy. It only seems to be required that the parties agree it is a risk worth avoiding.

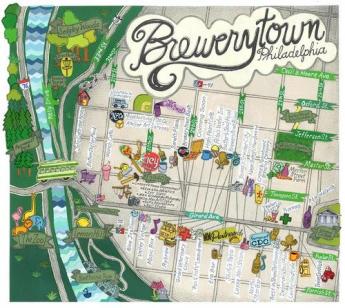

One Big Brewerytown

|

| Rich Wagner |

RICH Wagner, the author of Philadelphia Beer, recently visited the Right Angle Club. It's hard to imagine that Philadelphia was once the American center of beer production, with hundreds of breweries and their associated bottlers, beer gardens, brewing equipment, and horse-drawn beer delivery systems, dominating the city scene. Equally hard to imagine that the last Philadelphia brewery closed in 1987, and the biggest American brewer, Budweiser, was sold to the Belgians in the past year. What's this all about?

|

| Francis Perot |

In the early wilderness days, water supplies were tainted and unsafe, so most prosperous Quakers had their own little brewery just to avoid typhoid fever. The first American brewery was started by Anthony Morris (the second Philadelphia Mayor) in 1687, in a little brewery on Dock Creek, which became the early Brewerytown of the city, with several dozen brewpubs for sailors and the like. In 1797 there were over a hundred breweries in Philadelphia, and in 1840 there were over three hundred of them. Perot's brewery was prominent for a long time since an early Perot married a daughter of Anthony Morris. Since Philadelphia developed the first and famous city water supply in 1800, beer drinking lost its position as a safe beverage in an unsafe city, and gradually water-drinking became the dominant beverage for the strict and upright. At one time in the early Eighteenth century, gin was cheaper than beer, so even the intemperate multitudes deserted beer for a while, although the effect of the higher alcohol content of gin was apparently fairly dramatic.

|

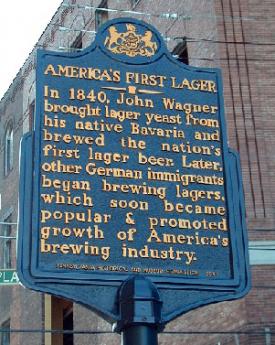

| John Wagner Marker |

In 1840 John Wagner imported the yeast for lager beer from Bavaria, at considerable personal risk if he had been caught at it. Prior to 1840, Philadelphia beer was either stout or Porter, a very dark and bitter dose, or else ale, which had the advantage of storing fairly well and thus was popular for sailing vessels and among sailors. The yeast for ale floats to the top and ferments, whereas lager yeast sinks to the bottom of the barrel and requires some refrigeration to slow it down. In all forms of beer, the suds are created by later adding some unfermented beer to the barrel for the purpose of generating carbon dioxide. That's what is going on when you see the bartender in a British pub pulling on a lever to pump it up from the basement. Lager tastes much less beery than other beer and is by far the dominant form of beer in consumption -- a considerable improvement, in the view of most people. But it has to be cooled, and Philadelphia had a system. Brewerytown moved to Kensington, dominating the local scene. It was produced in barrels which were trucked to the east bank of the Schuylkill where ice formed on the surface of the river, stilled by impoundment above the Fairmount Dam. Caves were dug in the banks of the Schuylkill where the barrels full of fermenting beer were hauled to be cooled by the ice for the rest of the process. From there, it was trucked again to bottlers in a general ratio of one brewer for thirty bottlers. More directly, it was trucked to the beer gardens of Spring Garden to Girard Avenue, which gave that area a different sort of reputation as a brewery town. By this time, most of the breweries had moved to the region between 30th and 33rd Streets, near Girard, and most of them still survive, made into condominiums by rehabilitation money. One by one, many sections of downtown Philadelphia acquired a beer environment. A dramatic moment in this process was the advent of the 1876 exposition, which caused many of the Schuylkill fermenting vaults to be acquired by eminent domain. A second momentous change was introduced by the invention of refrigeration, apparently invented in Germany near Berlin, but imported and refined by York and Carrier. Philadelphia was particularly suitable for the importation of coal to fuel the heating of the brew, and the chilling of the fermentation. All of this required large numbers of brewers, bottlers, makers of bottles and inventors of brewing equipment. It took many horses to haul all this material around town, and many teamsters to drive the horses. This was a beer town, until Prohibition.

During the long period of beer ascendency, the advantages of big breweries over small ones were gradually making this a major industry, rather than a local craft. Prohibition completed the destruction of the small craft brewers and brew-pubs. Only 17 of the major brewers survived Prohibition, and then even the big ones went out of business, ending with Schmidt's in 1987, almost exactly three hundred years after the first little one started by that famously convivial Anthony Morris on Dock Street. Evidently, the same competitive disadvantages continue as even Budweiser moves to Brussels, where you would ordinarily expect the wine to be the popular drink. Changing tastes have been cited as the reason for this shift, but differential taxes seem more probable as an explanation. In most industries, you are apt to find that most of the competition takes place in Washington and Harrisburg, rather than the saloons of Main Street or the salons of Madison Avenue. But perhaps not. We hear that little Belgium is about to have a civil war because the Flemish can't get along with the Walloons. And somebody in Portland, Oregon got the idea that beer was trendy, and started up the growing phenomenon of craft brewers, usually flourishing in brewpubs. We are apparently going back where we started in 1687.

REFERENCES

| Philadelphia Beer: A Heady History of Brewing in the Cradle of Liberty: Rich A. Wagner: ISBN: 978-1609494544 | Amazon |

Wistar Institute, Spelled With an "A"

|

| Dr. Russel Kaufman |

The Right Angle Club was recently honored by hosting a speech by Dr. Russel Kaufman, the CEO of the Wistar Institute. Dr. Russel is a charming person, accustomed to talking on Public Broadcasting. But Russel with one "L"? How come? Well, sez Dr. Kaufman, that was my idea. "When I was a child, I asked my parents whether the word was pronounced any differently with one or two "Ls", and the answer was, No. So if I lived to a ripe old age, just think how much time and effort would be wasted by using that second "L". In eighty years, I might spend a whole week putting useless "Ls" on the end of Russel. I pestered my parents about it to the point where they just gave up and let me change my name". That's the kind of guy he is.

|

| The Wistar Institute |

The Wistar Institute is surrounded by the University of Pennsylvania, but officially has nothing to do with it. It owns its own land and buildings, has its own trustees and endowment, and goes its own academic way. That isn't the way you hear it from numerous Penn people, but since it was so stated publicly by its CEO, that has to be taken as the last word. It's going to be an important fact pretty soon since the Wistar Institute is soon going to embark on a major fund-raising campaign, designed to increase the number of laboratories from thirty to fifty. The Wistar performs basic research in the scientific underpinnings of medical advances, often making discoveries which lead to medical advances, but usually not engaging in direct clinical research itself. This is a very appealing approach for the many drug manufacturers in the Philadelphia region, since there can be many squabbles and changes about patents and copyrights when the commercial applications make an appearance. All of that can be minimized when fundamental research and applied research are undertaken sequentially. Philadelphia ought to remember better than it does, that it once lost the whole computer industry when the computer inventors and the institutions which supported them got into a hopeless tangle over who had the rights to what. The results in that historic case visibly annoyed the judge about the way the patent infringement industry seemingly interfered with the manufacture of the greatest invention of the Twentieth century.

Patents are a tricky issue, particularly since the medical profession has traditionally been violently opposed to allowing physicians to patent their discoveries, and for that matter, Dr. Benjamin Franklin never patented any of his many famous inventions. But the University of Wisconsin set things in a new direction with the patenting of Vitamin D, leading to a major funding stream for additional University of Wisconsin research. Ways can indeed be devised to serve the various ethical issues involved since "grub-staking" is an ancient and honorable American tradition, one which has rescued other far rougher industries from debilitating quarrels over intellectual property. You can easily see why the Wistar Institute badly needs a charming leader like Russel, to mediate the forward progress of our most important local activity. From these efforts in the past have emerged the Rabies and Measles vaccines, and the fundamental progress which made the polio vaccine possible.

It was a great relief to have it explained that there is essentially no difference at all between Wisters with an "E" and Wistars with an "A". There were two brothers who got tired of the constant confusion between them, see and agreed to spell their names differently. When the Wistar Institute gathered a couple of hundred members of the family for a dinner, the grand dame of the family declared in a menacing way that there is no difference in how they are pronounced, either. It's Wister, folks, no matter how it is spelled. Since not a soul at the dinner dared to challenge her, that's the way it's always going to be.

"They Don't Make That, Anymore"

They Don't Make That, Anymore These words from the nice young lady in the drug store, left me astonished, baffled, bewildered, and angry.

Although I am retired from the practice of medicine, my limited license permits me to prescribe ethical drugs for myself. I had not realized, until that very moment, that to some extent it also isolated me from the experiences of my fellow patients. Let me explain.

The drug involved was tetracycline, which I had surely prescribed a thousand times, and to which I had a sort of loyalty growing out of the fact that I took it myself. In the days when I was a college student, I came down with a form of pneumonia that involved a lot of coughing, like whooping cough. It was then called virus pneumonia because it was somewhat different from ordinary pneumonia, even though it was called Primary Atypical Pneumonia in polite academic circles. Eventually, we learned that its cause was neither a virus nor a bacterium, but rather something in between in size, called Mycoplasma. All of this is important to know, because it tends to appear as a question on a certification examination, but the fact of the matter is, it was a disease for which there was no effective treatment. We could cheer up a little to know that of four hundred recruits at an Alabama training center who came down with it, only one died. On the other hand, Legionnaire's Disease is also caused by a Clamydia and lots of them died, probably because most of them were older. But no matter, in 1944 there was no treatment, and I can tell you it is very unpleasant for a very long time, no matter how young you are.

|

| CAT Scan |

In 1950 I got it again, but this time I was a doctor and knew there was a good treatment. It sounds strange to say so, but I was sort of happy to be able to try out the new medicine, which was then called Aureomycin because the powder was golden yellow. Aureomycin was a trading name, with a patent, and when the patent expired the generic form was called Tetracycline. It worked just fine, and in three or four days I was out of the hospital, perhaps a little weak and shaken, but cured. Incidentally, I discovered an interesting feature of the disease which I believe has not been previously reported. It had long been observed that the chest x-ray showed pneumonia while the stethoscope perceived very little abnormality, a feature which disconcerted those of us who were concerned with the cost of medical care, particularly members of a generation who felt sniffy about the dependence younger physicians displayed for x-rays, and nowadays for CAT scans and MRIs. Unfortunately, in this particular instance, x-rays are clearly superior to stethoscopes.

My third time around for "viral" pneumonia was a few years later; I was sitting on a park bench near the hospital when I recognized the old symptoms were coming back again, so I went straight to the x-ray department and had a chest x-ray less than an hour after the symptoms appeared. I planned to have an x-ray to prove it, go get some tetracycline and be all better over the weekend, with a rollicking anecdote to tell doctor friends about. Unfortunately, the x-ray was normal, so I was admitted into the hospital to see what was wrong. The next morning the x-ray showed a densely consolidated lung, so it had been viral pneumonia all along. And so my old prejudices were vindicated; it was possible to be too quick to order x-rays after all. Unfortunately, the extra twelve hours without treatment allowed me to get a lot sicker than I had to be. I think I know this because, doggone it, I developed the same disease several decades later, took no shortcuts to the drug store, and was fine in a couple of days after I immediately started taking tetracycline. You could say this strange recurrence of Mycoplasma pneumonia over one-lifetime sort of illustrates how medical care of the disease has become progressively cheaper. Instead of a month in the hospital with no treatment, it was now a matter of skipping the stethoscope, skipping the x-ray, skipping the hospital, and just swallowing some cheap tetracycline capsules. You have to have the nerve to do it, of course, and ethically you probably only have a right to do it to yourself, knowing the risks and being willing to accept them. There is, however, one flaw in this story.

When Aureomycin first emerged from the clutches of the FDA (and well before that accursed Kefauver Amendment), it seemed astonishingly expensive. Because I knew what it weighed (250 milligrams per capsule), and I knew what gold cost ($35 an ounce), it was easy for an idle mind to calculate that Aureomycin cost more than gold. Gold now sells for $1700 per troy ounce, so you could take this story in the direction of inflation. I rather prefer to take it in the direction of nominal dollar amounts, because Aureomycin retailed for $5 a capsule the third time I had the disease, and $1 per capsule when it lost its patent and became tetracycline. The fourth time I had the disease, I bought a container of fifty capsules for 76 cents. But as you have already heard, by the fifth time I couldn't buy it for any price, because everybody had stopped making it. Since my view of the economics of useful commodities is that low prices will only cause shortages if there is artificial market interference, the usual cause of shortages is rationing. Somebody who understands the 2500 pages of Obamacare better than I do will have to tease out the way rationing has caused shortages of tetracycline. And when they are done confusing the public, let them explain why you also can't buy KMnO4 crystals (potassium permanganate), which has cured more cases of athlete's foot for twenty cents, than all those cans of stuff in spray canisters.

Bernanke's QE3: A New Titanic, or A New Bretton Woods?

|

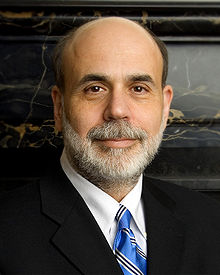

| Ben Bernanke |

Nobody likes to execute a guilty prisoner, but in finance, it is surely true that allowing bad debts to remain unresolved harms the whole economy. It makes little difference whether a bank fails to mark its debts to market, whether debts are "extended", or insolvent institutions are subsidized. Andrew Mellon once advised Herbert Hoover that he should "wring the rottenness out of the system", but that is such poor politics that even Hoover rejected it. In time, the process of "good bank, bad bank" was devised to isolate bad debts into a single institution so the rest of the economy could begin to recover. QE3 is a version of a good bank, bad bank. Unfortunately, the public is easily misled in these matters, so although all three Q's involve the Federal Reserve buying long bonds, QE1 unfroze a frozen financial marketplace (successfully), QE2 meant to stimulate the economy (unsuccessfully), but QE3 seems to have much grander ambitions. So it is unfortunate that three different activities share the same name, and still more unfortunate that name is made so mysterious. Let's forget about the first two, and concentrate on QE3.

The Federal Reserve is well along in a program of buying huge quantities of questionable long bonds and has announced it is going to keep buying huge quantities until either inflation exceeds 2.5% or unemployment falls below 6.5%. That's not exactly the same as buying every bad bond in existence, but it could come to that. Instead of letting the holders of those bonds go bankrupt, the Fed is buying the bonds out of circulation, which could rescue a great many investors. Small businesses do not ordinarily issue bonds, so there is some bias in favor of large businesses and banks, but surely not an intentional bias. The effect is to make the Federal Reserve both a good bank and a bad bank at the same time. The main difference between this and wringing the rottenness out is that bankrupt institutions cannot come back to haunt you, while in the more benign purchase of bonds, you have assumed an obligation to pay them back. When you sell them back you drive the price down and the money disappears. Furthermore, when the price of bonds declines, interest rates will rise and the national debt will increase more rapidly. If the economy cannot withstand higher interest rates, a recession will deepen. You have to get the timing right, and the world is in such a delicate state that it is impossible to get the timing entirely right for everybody. Because interest rates are now essentially zero, they cannot go lower, so investment advisors are increasingly advising clients to sell some bonds while they still can. If that gets out of hand, it could start a panic.

|

| United States Federal Reserve |

However, the United States Federal Reserve is not an investor, it controls the currency and can print unlimited amounts of it. There is nothing which can force it to sell its bond holdings, ever. Without going into the details of the Bretton Woods Treaty, the tie to gold was eliminated nearly fifty years ago. Meanwhile, its bonds are paying interest, which at the moment it is returning to the U.S. Treasury to reduce the national debt. It can reduce this outflow more or less at will, and it can increase it by raising interest rates (ie by selling bonds, as described). With a few extra steps, this enormous pot of debt could become the basis for an international currency reserve. At the least, it could bring a halt to an international currency war. If it chooses, it can decide to wait as long as fifteen or twenty years for economic demand to recover from a century of overleveraging, and then pay it back by letting the bonds reach maturity. But there is at least one big flaw in this dream.

At some point, the bond market may decide to take the bull by the horns and raise rates before the Federal Reserve wishes to. Political appointees come and go, and the bond market could easily decide that a misjudgment has been made by somebody. It could easily happen that public apprehension could grow that something doesn't smell right. In that climate, a few heavy sales could trigger a panic. And then everyone will try to get out the door at the same time.

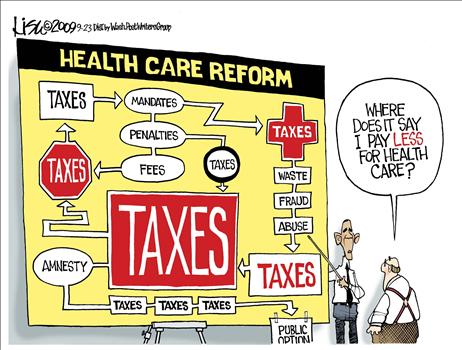

Looming Early Issues in Obamacare

|

| Obama Care |

The Attitude of Big Business. In order to preserve maximum flexibility as long as possible, many important features of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) remain unrevealed, and some are perhaps still unsettled. Furthermore, attitudes change with experience. At the formation of the Obamacare idea, the leaders of big business (at the time) were more concerned about foreign competitors than about employee attitudes. The traditional goal of a "level playing field" led them to favor an employer mandate to provide employee healthcare. It probably was presented to them that they could only have their desires by agreeing to a universal individual mandate for everybody. Although it was uncertain whether the employees would agree, universal was the price to be paid, and they paid it. Whether new leadership supports this compromise or not, it is generally assumed that big business feels obliged to support Pete Stark's universal mandate until it is tested. Only time will tell whether businesses will withdraw their support in the face of events, but fragile beginnings certainly do not assure permanent support. Since it was the withdrawal of this group's support which destroyed the Clinton plan in 1994, a significant issue hangs in the balance. Therefore, when conflicts were discovered with the ERISA laws under which big business works, the inclusion of big businesses in the framework of the Affordable Care Act was postponed for a year. How it will emerge next year or whether the ACA can survive for a year without major business inclusion, both remain to be seen.

The Rising Voice of the Uninsured. A financial recession usually increases the number of health uninsured, but at present unemployment is slowly falling. However, decades of scientific medical advances are not only extending longevity but reducing non-fatal illness among the young and uninsured. Although it is unclear whether youthful perceptions match the actual changes in their morbidity, young healthy people who rebel at paying health insurance premiums may actually increase in number substantially during the coming decade. Although overall inflation has been moderate, discomfort from competing costs of college debts and items such as gasoline have escalated. When the Affordable Care Act is fully implemented, youthful perception may make the first serious test of its usefulness. Those among them who actually get sick may get an opportunity to sample Medicaid and report their experiences to their friends. To some extent, this will be a race between efforts to improve Medicaid in order to forestall complaints, and the tendency of young people to try to get their way by pounding the table with their shoe. If successfully managed, it could promote some badly needed improvements in Medicaid. Handled poorly, however, it could bring the program down.