5 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

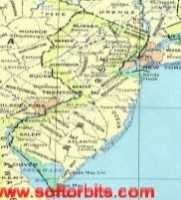

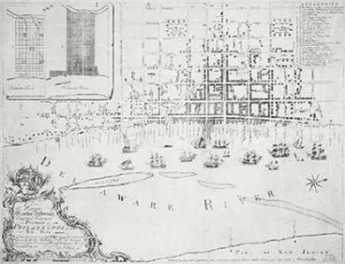

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Medicine

New volume 2012-07-04 13:34:26 description

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

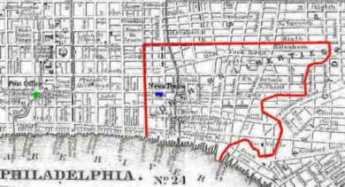

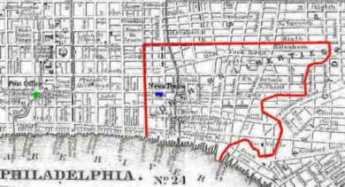

North of Market

The term once referred to the Quaker district along Arch Street, and then to a larger district that had its heyday after the Civil War, industrialized, declined, and is now our worst urban problem area.

North of Market

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

In their 1956 book "Philadelphia Scapple", Harold Donaldson Eberlein and Mrs. Henry Cadwalader give an interesting description of the evolution of the term "North of Market". In the early days of the city, almost all of the town was South of Market Street. In fact, an early 18th Century visitor once wrote that he always brought a fowling piece when he visited Philadelphia because the duck hunting was so good at the pond located at what is now 5th and Market.

When the Quaker meeting house was built at 4th and Arch Streets, many of the more important Quaker families thought it was important to build their houses nearby. In that way, Arch Street developed the reputation of being a Quaker Street. So the original meaning of the North of Market term was the Quaker ghetto. Quaker families continued to spread West along Arch Street or nearby, and this accounts for the location of the Friends Center at 15th and Cherry and related local activities. When the Free Quaker were evicted from the meeting at 4th and Arch because of their activities during the Revolution, they built their own meeting at -- 5th and Arch.

|

| Chinese wall |

During the Civil War, a number of people made fortunes that socially upscale people over in the Rittenhouse Square area considered disreputable, so elaborate but ostracized mansions marched due North up Broad Street, where they can still be observed as stranded whales in the slums, leaders without followers. The show houses of manufacturers of shoddy war goods soon gave the meaning of parvenu to the term North of Market.

And then, the Pennsylvania Railroad ran an elevated brick structure from 30th Street to City Hall Plaza, the so-called Chinese Wall. For nearly a century this ugly looming structure on Pennsylvania Boulevard, now John Kennedy Boulevard, with its smoky engines above, and dark dripping tunnels at street level, sliced the town in half and made it very unattractive to build or to live, North of Market. The Spring Garden area had some pretty large and expensive houses, but it was cut off by the railroad trestle and has only recently started to revive. It helped a lot to tear down the Chinese Wall, but that was fifty years ago, and the area has taken a long time to recover from the earlier diversion of social flow to the South of it. And, psychologically, North of Market will take even longer to recover from the implication of -- industrial slum.

|

| center |

Meanwhile, of course, Oriental immigration settled along Arch Street at 9th to 12th Streets, and we now have our Chinatown there, complete with street signs in oriental lettering. In effect, we have a real Chinese Wall, a social one. Just what will happen to this group is unclear, since it is readily observable that they like to cluster together, unlike the East Indian immigrants, who head for the suburbs as fast as they can. Since the Chinese colony is physically blocked on all sides by the Vine Street Expressway, the Convention Center, and the Ben Franklin Bridge, it is hard to know where they will flow if the group gets much larger. The depressed Vine Street crosstown expressway makes a definitive border for downtown, and the contrast between the two sides of this expressway is striking. On one side is Camelot, and on the other side, almost nothing is being built. The future of North of Market, at the moment, is a little unclear.

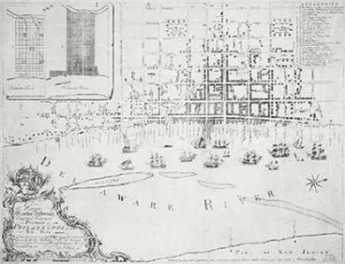

Broad Street North and South

Following the instructions of William Penn, all of Philadelphia's original numbered streets are laid out by the compass, due North and South. Without getting into a history of how the street names then got modified somewhat, Broad Street by the present system would be 14th Street. Center Square of the original five parks is placed at the intersection of Broad and Market Streets. After a period functioning as the city water-works, the intersection has been occupied by City Hall for over a century. Originally intended to be the tallest building in the world, the tower of City Hall still dominates the landscape in all four directions for a considerable distance. It also stands at the foot of the diagonal Benjamin Franklin Parkway, so City Hall stands like a Parisian intersection rather than the Scotch Irish Diamond it once was. Nevertheless, when you look down the long canyon of each intersecting street, the tower in the middle of the street dominates the view. Let's begin a tour of the whole extent of the longest street in Philadelphia, at the southernmost end of Broad Street, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard.

|

| Gene Tunney vs Jack Dempsey |

Although the guard will be happy to tell you it's a dumb regulation, you aren't allowed to take pictures of the Navy Yard, or visit without a pass, in spite of the fact the area of the yard is fast being converted into business properties. A great many of the warships that won our wars were built in this yard, and many rests in a sort of floating Navy graveyard, or mothball fleet, which is best seen from the elevated highway nearby, Interstate 95. The shipyards rest on the filled-in area around Hog Island, home of the hoagie sandwich. Just north of the Navy Yard are several sports stadiums and a great deal of parking space to service them. Much muttering is heard about the tax cost of this stadium farm, whose many-million-dollar facilities are only used for between eight and eighty home games apiece each year. The stadium-sprouting process began with Municipal Stadium which was built for the Dempsey Tunney prize fight, and held 110,000 spectators. In the time it housed the annual Army-Navy football game, but not much else, and has since been demolished. It certainly seemed to be the windiest, coldest place on earth, but that's just a child's recollection. At that time and for many years the area around the stadium was one huge garbage dump, and before that it was a huge swamp, the source of mosquitoes, malaria, typhoid and yellow fever. Fish like to eat mosquitoes, so filling in the South Philadelphia swamp badly injured the seafood industry of Delaware Bay, while admittedly ridding us of Yellow Fever epidemics. The swamp once extended as far as Gray's Ferry where the University of Pennsylvania now looms, with patches of quite rich farmland scattered in the swamp. Stephen Girard had a large farm just to the West of what is now South Broad Street where he cultivated vegetables necessary for the French cooking he favored.

|

| Mayor Richardson Dilworth |

As you drive north on Broad you begin to notice the quaint Philadelphia custom of parking your car in the center of the wide street. Mayor Dilworth once announced this had to stop, but the uproar from local residents forced even this ex-Marine officer to retreat. Down the side-streets a variation is seen; when the local resident drives off, he leaves trash cans in the street, indicating it is private property. Rumor has it that people who ignore the warning can get their windshields smashed with a brick. This area is as urbanized as you can get, but the spirit of the wild, wild West nevertheless prevails.

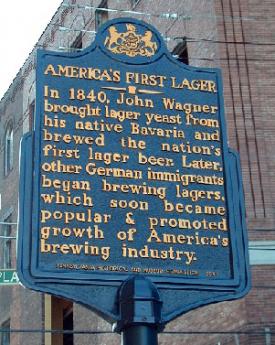

Brewerytown

|

| Beer Wagon |

After the Civil War over a hundred breweries serviced by a large German population, concentrated around the Schuylkill River between Spring Garden and Girard Avenues. Lager beer requires ice, and Brewerytown by 1880 reversed the usual Philadelphia population growth pattern by spreading East from the Schuylkill caves and ice vaults toward the Delaware River wards as electric refrigeration made that practical. There were more breweries along the Schuylkill than could be accommodated anyway. Prohibition in 1919 then abruptly killed the beer industry, Brewerytown became a slum. A large real estate developer is now trying to gentrify that area, laying down rather arbitrary borders to a brewery area after all breweries have disappeared. Some heated but pointless arguments are heard about which block is, or is not part of Brewerytown; the fact is, it's hard to say.

After World War II the area was filled with deserted houses, Skid Rows, and questionable characters. The worst Skid Row was at the base of the Ben Franklin Bridge along the edge of Franklin Square, probably not within any reasonable definition of Brewerytown but certainly affected by the brewery upheaval. After this blight had been brutally cleared away, a strip between Vine Street and Fishtown/Kensington became mostly a no-mans land of vacant lots, awaiting a developer. Or an expanded Chinatown, or whatever else will eventually be drawn into large parcels of land quite near the center of the city. The vacancy rate is unusually high because of the barrier of the cross-town Vine Street Expressway, but it can't last; whatever fills this vacuum is going to make a big impact on the future of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, it's patchy, sort of like London after the blitz.

But what's behind the rise and fall of the breweries?

Beer was known to the ancient Egyptians, and mentioned by Aristotle, Herodotus, Pliny, and Tacitus as the "wine made out of barley". Grain grows better in rainy Germany, while grapes grow better in dry Mediterranean regions, so beer has long been more popular among Central European people than Latin ones. The beer itself changed very little until the time of the American Civil War when Lager beer was introduced. Ale, porter and brown stout are brewed at room temperature, but lager beer must be kept very cold from start to finish. And that's the underlying fact driving the massive expansion of beer consumption. People like cold lager beer much better than the warm stuff. In 1863, Americans consumed 3 million barrels of warm stuff, but in 1883, they consumed 18 million barrels of cold lager. Enter, Philadelphia.

At first, cold lager was brewed in caves, and only in the winter. If you wanted to go for big volume, you had to haul in tremendous amounts of ice and build massive fortresses to hold all the weight. Pictures of 19th Century Philadelphia are astonishing for the huge size of the breweries, the associated stables, and beer gardens. These things needed railroads and harbors nearby to ship out the product, and to ship in the grain, ice, glass bottles. And coal.

The underlying principle was that breweries had to generate their own electricity in order to run the refrigeration units, and the refrigeration industry itself was stimulated to develop nearby. It's probably no accident that the science of electrical engineering was largely developed in Germany during this time. Another factor required was good water, supplied by Artesian wells going down to the Raritan aquifer. And finally steam was a big ingredient, used to sterilize the bottles, brew kettles, and floors of the brewery. Cleanliness was not just a necessity, it was a fetish. Even the horses were cleaned by steam, a mass production effort requiring two minutes per horse. Lots of horses and lots of Teamsters. So many in fact the dairymen were the main audience for the local professional baseball teams.

Three things killed the breweries.

Philadelphia water became notoriously bad, and conservation movements began to protect the aquifers from excessive penetration. The cheapest refrigerant was ammonia, and its use was prohibited by local ordinances, concerned by gas warfare in World War I. But the biggest killer was prohibition. Distilled spirits were easier to smuggle in from Canada (to Boston), ounce for ounce of alcohol content. Little copper stills could be hidden in the Jersey Pine Barrens, or the hills of Appalachia, but lager breweries were here in the first place because they were so enormous and industrial. Prohibition lasted long enough to change American tastes from beer gardens to speakeasies, from beer to booze. During that period, the huge industry sort of collapsed and never revived. It's certainly true that fickle American tastes, guided by the tax laws, have once more turned from distilled spirits to fermented ones. But now it's grape wine, not barley wine that has engaged the excitement of young things on both coasts. What beer industry it is left has migrated to the center of the country, the so-called red states, and grape versus barley has become a social-political issue to be decided every four years, on the first Tuesday in November. Trace out the local liquor taxation rates if you doubt it.

Northern Liberties Starts to Revive

|

| The Northern Liberties |

In 1999, the American Friends Service Committee was repaid $50,000 by a Quaker volunteer group who had been working to rehabilitate the Northern Liberties area of the city. The debt was fifty years old. Not a word of reminder had ever been sent to the debtor group, and in truth, the Service Committee had pretty well forgotten about the matter. But the Quakers who borrowed the money hadn't forgotten and would have been appalled at any sly suggestion that they just wait and see if someone pursued them for it. The other thing this quaint little story illustrates is the discouragingly long time the slums of Philadelphia have remained slums, and what a long disheartening process it may be to reverse the decline of a neighborhood.

The Northern Liberties section of town is best described as Ole City, extended, on the North side of the traffic lanes feeding the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. The North-South streets go under the bridge, but it's sort of dark and forbidding under there. The riverfront area, which once looked like something out of Charles Dickens, has been cleared away. Girard Avenue gives the Liberties a northern boundary, and the tracks of the former Reading Railroad establish a Western limit. At least half of the buildings in this area have been torn down, a few blocks of low-cost housing have been put up, and the rest is a little island of modest housing of the vintage of 1840-50. The people in this area look at you as though you were potentially a scout for the Iroquois Indians, but if you have a greeting to them, they are immediately very friendly.

This area was just outside the boundaries of Penn's original city, and got its name, Northern Liberties, from the fact that sailors from the harbor were directed over the line if they were looking for strong beverages and lively companionship. Taxes and tariffs were probably an issue as well, and Second Street is an ultra-wide boulevard with slanted parking because it was a market street, with stalls running down the center of the street. Second Street is where the bars and restaurants, shops and art galleries, are starting to reappear. It's gratifying to feel the enthusiasm of these young kids, risking their time and savings in a great shared adventure. Some may get rich and some will surely fail, but the sense of adventure is palpable.

Like all kids, nowadays, they talk about real estate prices constantly. Anyone who lived through the 1930s has to shudder at what they call a marvelous bargain price for real estate. Anyone who lived through the 1960s listens to their description of "normal" real estate prices in Boston, coming away re-convinced that people who live in Boston must be stark raving mad. But these entrepreneurial kids are the life-blood of America, and may God Bless their undertakings.

The main steadying, adult influence in the area seems to come from the little bank. It's a branch of a bank headquartered in Newtown Pennsylvania, with eighteen branches in the rural counties and the developing areas of Philadelphia. These are real, old-time bankers, doing old-time banking. The branch manager knows the young people in the neighborhood, knows who pays his bills, watches who keeps his roof fixed. By learning to tell a good one from a bad one, the bank manager is able to stretch the credit limits for some and tighten them for others. The bank holds everybody's money; the whole region will fail if the bank is unwise with it. In an era when a successful bank must be either global or local, re-developing regions need banks of the style of 1840, likely now to be found in Newtown, West Chester, and Georgetown. As if to emphasize the point, you will find a horse farm on Third Street, within easy walking distance of the Ben Franklin Bridge. The horses come over to the chain fence looking for handouts of candy and canter away if it is not forthcoming. They are gentle, their business is pulling carriages around Independence Hall. In their trade, they must have acquired a great deal of misinformation about the Revolutionary War, as indeed have the rest of us.

It was 90 degrees the other day, and something had to be done to ward off heat stroke. The bar mistress was asked if she knew how to make Fish House Punch. Never heard of it, but eager to learn. The bar had a computer, "Philadelphia Reflections" supplied the recipe, and the local congregation enjoyed a round of what must have been the first Fish House Punch -- in Fishtown -- in two hundred years. The flavor seemed to live up to the novelty, and the idea might just catch on.

One enthusiastic young redeveloper relates that the City has a tax abatement plan. No taxes for ten years if the lot had been vacant or the building unoccupied. No taxes on the improvement, that is, but regular taxes on the underlying land. Why that's the Henry George system. The young redeveloper didn't know about all that, but it seemed like a good system. Imagine the later surprise to see that the horses are grazing on George Street! There's a story there, and a story about Saint John Neumann Lane, a block away.

Photos were taken of the scabrous buildings and the weed-filled vacant lots. Those are the "before" of the before and after.

Chinese Canyons

|

| Chinese Wall |

Until well after the Second World War, the entire western side of city hall was facing the Pennsylvania RailRoad . An enormous rambling smoke-stained Broad Street Station squatted right across the street, and westward behind it to 30th Station stretched -- the Chinese Wall. The railroad tracks were elevated forty feet above street level, resting on top of a very wide brick wall with openings at each cross street allowing traffic to go under the tracks. It was dark, dirty, gloomy and hard to ignore, and the tunnels at each cross street were even darker. They had a tendency to drip water on the sidewalks. Whether these tunnels were a place for crime to take place is not certain, but it looked as though that would be true since an army of panhandlers and stumble-bums reinforced the impression by keeping out of the rain under there.

|

| JFK BLVD |

Consequently, the two streets which paralleled the Chinese Wall (Market Street, West, and Pennsylvania Avenue) were lined with dubious structures housing questionable businesses. After the War, Broad Street Station was torn down, the Chinese Wall of train tracks was removed, and it suddenly became clear that City Hall was now approached by two wide boulevards stretching west, with the handsome classical 30th Street Station framed in the center of one of them, renamed JFK BLVD. High rise buildings were built in large numbers along both sides of the two boulevards in what now are four parallel rows, twelve blocks long. Because these buildings were put up under the gentleman's agreement that City Hall would be the height limit, Philadelphia avoided the dark canyon effect so depressingly present in the Wall Street financial district of New York City. However, the two boulevards do not escape the Marilyn Monroe effect.

|

| Marilyn Monroe skirts |

Named after a famous movie scene in which that actress had her skirts blown upward in public, the phenomenon usually has to be explained to newcomers. Winds blowing against the tall face of the buildings are blocked and scoot down to the sidewalk along the side of the buildings. When they reach the ground they have no direction to go but up again. Billowing skirts are in reality not particularly noticeable, but these two stretches of the street usually are windy, and in mid-winter, it is bitterly uncomfortable to walk there. Because rentals are high, these new high-rise buildings are too expensive for the small stores and merchants to set up their shops on the first floor, so almost no one is on the street except those in a hurry to get somewhere else. After five o'clock, these commercial centers are totally deserted and quite forbidding.

One response has been to go underground. The Market Street subway goes underground the whole length of Market West, paralleled by a "subway-surface line", which is to say, trolley cars. So it has seemed natural to tunnel pedestrian walkways along with the basement level of Market Street, and little shops have tended to find a place there, although when commuter traffic declines, they turn out the lights and pull down the steel shutters. It's a nice place to duck out of the rain (and wind), but Philadelphia isn't Montreal or Minneapolis, with tons of snow to drive people underground. Long before the 9/11 tragedy, Wall Street's financial district was deserted at night, too, so this is a generic problem of skyscraper districts, waiting for somebody to suggest a solution. In a way, New York's Park Avenue suggests that when you are moving railroads underground in a city, apartment houses may make for a better new neighborhood than office buildings do.

But such reflections are part of what is called Philadelphia's inferiority complex. Let's face it, the renovation of the Market Street West project is a vast, vast improvement over the mess that was there for a century. It's a success, right?

Chinese North

Mary Scott was recently introduced to the Right Angle Club by Buck Scott her father (and last year's program chairman.) Mary is fluent in Mandarin, lives in Beijing, and has a PhD. from Princeton. Although her luncheon talk had some of the features of a very polished travel talk with slides, it was considerably deeper than that.

|

| Forbidden City |

We learned the exiting news, easily confirmed by Google Earth, that the streets of both Beijing and Philadelphia are laid out in north-south, east-west squares. As we have noticed, Philadelphia was laid out with a magnetic compass, so Broad Street is 6 degrees off true North. Beijing, on the other hand, is almost exactly true North and South. While it is unclear how this was done two thousand years ago, it seems a likely conjecture that the Chinese architects probably used the North Star as a guide. This would have been in keeping with their notion of the Forbidden City as the center of the universe. Everything revolves around the Emperor, just as all other stars revolve around the Polestar.

|

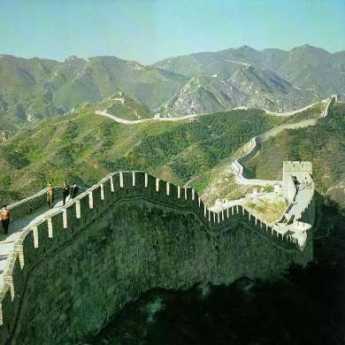

| Great Wall |

With primitive communication, and possibly even with the modern electronic variety, it is difficult to maintain control of a large empire without decentralizing. The ancient Chinese method was to put the many sons of the Emperor in charge of local districts, which got them out of Beijing where they were only making trouble, and assigned them the job of fighting with the neighboring Mongol tribes which would keep them busy. For this reason, the Great Wall is really many great walls, as the frontier advanced and retreated. When the Emperors died, there was always a major problem of succession, but at least each son had a military and administrative track record which reduced the number of aspirants to a handful of the biggest baddest ones.

|

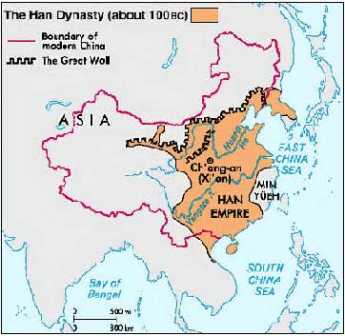

| Han Dynasty |

The Great Wall resembled a dragon, the symbol of the Emperor. It thus projected the image of his power out to the edges of the Empire. It had a road running on its top, greatly facilitating the shifting of defensive troops. As a defensive barrier it was only fair, having been breached many times, and on one occasion the Mongols even took the Emperor prisoner for ransom. However, the Wall's underlying purpose was to inhibit immigration, where it was probably reasonably effective. While at first the Han dynasty was mostly concentrated around the capital city, the Han Chinese gradually drove out, starved out or frightened out the others throughout the entire Empire. It is possible to see this relentless process in the recent treatment of Tibet. The underlying thought has been that if you don't exterminate them, eventually they will exterminate you.

|

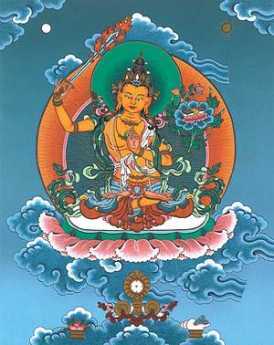

| Tibetan Buddhism |

The Chinese prescription for domination has always been cultural as well as military. The Emperor was divine, far above other men. The symbolism of the dragon, of the golden color, and even the imposition of coherent architectural design on the city suggested his presence everywhere. Conversely, Tibetan Buddhism was a cultural threat from abroad, to be stamped out whenever it was safe to do so. And the recent policy of one child per mother leads to depopulation, which in turn will surely make the fecundity of neighbors a threat to China.

For thousands of years, the Chinese have worked out a system for just about everything except for peaceful succession of its rulers. That continues to be the case today, and we all better hope they eventually figure something out.

Block Captains

|

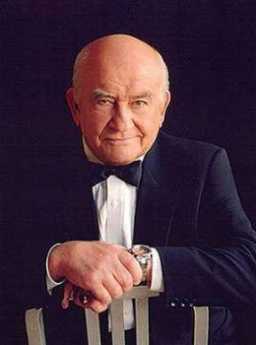

| Ed Asner |

A block captain is not a ward leader, at least not most of the time. The block leaders of Philadelphia are mostly self-appointed, de facto captains, and yes, they are mostly middle-aged black ladies. Their attitude is that politicians are there to serve the community, not the other way around. At a recent meeting, the leader of the Block Captain's Association called out to the nodding, approving group, "Call your councilman. We elect those people, put 'em to work!"

This enthusiastic group of several hundred grass-roots leaders meets several times a year in, of all places, the hallowed auditorium of the Philadelphia County Medical Society, but doctors are not running this show. Nor is the City Health Department, nor the Department of Streets, nor the various mental health and social service agencies that send representatives. The federal government expressed considerable gratitude in being able to address this group because their new Medicare prescription card was so terribly hard to explain (i.e. it was terribly hard to understand). The genius of the block captain movement is that it appoints leaders to understand what the establishment is trying to say, and then figures out a way to say it. You can make free flu shots available, even take them to the home or workplace, but most people won't accept them unless it is explained by someone they trust. Dead birds don't spread disease, mosquitoes do, but that really sounds a little unlikely. To believe that, you first need the word of a respected local leader. The U.S. Army is built around its sergeants, in the same way. That's in fact how things work at every social level, but in Philadelphia's black communities, it is finally becoming organized. For example, they like pamphlets. Pamphlets are what give sergeants credibility back in the neighborhood.

Success has a thousand fathers, failure is an orphan, so it's now hard to know who started this. Eve Asner, the sister of Ed Asner the movie star, can claim credit for starting a group called Philadelphia More Beautiful, dedicated to cleaning up the messes of the slums, and applying social pressures of a loud and effective sort to irresponsible neighbors. And then, along came the Deputy Health Commissioner Larry Robinson with HEAT. During a hot summer, it was possible for a hundred children and old folks to die of heat prostration because they were confused by dehydration and did things which made matters worse for themselves. The block captains were ideally situated to know who was in danger, who hadn't appeared outside in a day or two, and thus who might need to be forced to drink water or go to an air-conditioned movie. Training the block captains to recognize the signs of trouble fit nicely into the Health Department's ability to measure results with computers. Last year, only seven people died of heat prostration, and everybody knows whose block they lived in.

The Medical Society pays for everybody's lunch at the block captain's meeting, and it is a calculated policy. Every doctor knows how useless it is to talk in terms of calories, carbohydrates, high unsaturated fat content, and water-soluble vitamins. Pamphlets help, but what really works is to serve the block captains a lunch and tell them, now this is what we're talking about. Heaven only knows how that gets translated back in the neighborhood, but surely the first step is to give the block captain an unmistakable message. The Medicare bureaucrat looked visibly relieved when her painfully convoluted explanation of the Medicare prescription card was reduced to about two sentences by questioners in the audience: If you have Medicaid coverage, forget it. If you don't, that card's worth about $600. And this here pamphlet proves I know what I'm talking about.

There did not seem to be a scrap of ideology or power hunger or self-serving -- the usual hallmarks of politics as we commonly observe it. The over-riding principle on which these highly disparate groups are operating together is, pick a problem, and solve it.

Charles Dickens Doesn't Like Our Nice Penitentiary

In 1842, Philadelphia's Eastern Penitentiary was innovative and unique. It was an important tourist stop, especially for foreign visitors, and Charles Dickens naturally had to pay it a visit when he toured America in 1842. He didn't like it, and he said so, as follows :

In the outskirts, stands a great prison, called the Eastern Penitentiary: conducted on a plan peculiar to the state of Pennsylvania. The system here is rigid, strict, and hopeless solitary confinement. I believe it, in its effects, to be cruel and wrong.

In its intention, I am well convinced that it is kind, humane, and meant for reformation; but I am persuaded that those who devised this system of Prison Discipline, and those benevolent gentlemen who carry it into execution, do not know what it is that they are doing. I believe that very few men are capable of estimating the immense amount of torture and agony which this dreadful punishment, prolonged for years, inflicts upon the sufferers; and in guessing at it myself, and in reasoning from what I have seen written upon their faces, and what to my certain knowledge they feel within, I am only the more convinced that there is a depth of terrible endurance in it which none but the sufferers themselves can fathom, and which no man has a right to inflict upon his fellow-creature. I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain, to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body: and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye and sense of touch as scars upon the flesh; because its wounds are not upon the surface, and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay. I hesitated once, debating with myself, whether, if I had the power of saying 'Yes' or 'No,' I would allow it to be tried in certain cases, where the terms of imprisonment were short; but now, I solemnly declare, that with no rewards or honours could I walk a happy man beneath the open sky by day, or lie me down upon my bed at night, with the consciousness that one human creature, for any length of time, no matter what, lay suffering this unknown punishment in his silent cell, and I the cause, or I consenting to it in the least degree.

I was accompanied to this prison by two gentlemen officially connected with its management, and passed the day in going from cell to cell, and talking with the inmates. Every facility was afforded me, that the utmost courtesy could suggest. Nothing was concealed or hidden from my view, and every piece of information that I sought, was openly and frankly given. The perfect order of the building cannot be praised too highly, and of the excellent motives of all who are immediately concerned in the administration of the system, there can be no kind of question.

Between the body of the prison and the outer wall, there is a spacious garden. Entering it, by a wicket in the massive gate, we pursued the path before us to its other termination and passed into a large chamber, from which seven long passages radiate. On either side of each, is a long, long row of low cell doors, with a certain number over every one. Above, a gallery of cells like those below, except that they have no narrow yard attached (as those in the ground tier have), and are somewhat smaller. The possession of two of these, is supposed to compensate for the absence of so much air and exercise as can be had in the dull strip attached to each of the others, in an hour's time every day; and therefore every prisoner in this upper story has two cells, adjoining and communicating with, each other.

Standing at the central point, and looking down these dreary passages, the dull repose, and quiet that prevails is awful. Occasionally, there is a drowsy sound from some lone weaver's shuttle, or shoemaker's last, but it is stifled by the thick walls and heavy dungeon-door, and only serves to make the general stillness more profound. Over the head and face of every prisoner who comes into this melancholy house, a black hood is drawn; and in this dark shroud, an emblem of the curtain dropped between him and the living world, he is led to the cell from which he never again comes forth, until his whole term of imprisonment has expired. He never hears of wife and children; home or friends; the life or death of any single creature. He sees the prison-officers, but with that exception, he never looks upon a human countenance or hears a human voice. He is a man buried alive; to be dug out in the slow round of years, and in the meantime dead to everything but torturing anxieties and horrible despair.

His name, and crime, and term of suffering are unknown, even to the officer who delivers him his daily food. There is a number over his cell-door, and in a book of which the governor of the prison has one copy, and the moral instructor another: this is the index of his history. Beyond these pages the prison has no record of his existence: and though he lives to be in the same cell ten weary years, he has no means of knowing, down to the very last hour, in which part of the building it is situated; what kind of men there are about him; whether in the long winter nights there are living people near, or he is in some lonely corner of the great jail, with walls, and passages, and iron doors between him and the nearest sharer in its solitary horrors.

Every cell has double doors: the outer one of sturdy oak, the other of grated iron, wherein there is a trap through which his food is handed. He has a Bible, and a slate and pencil, and, under certain restrictions, has sometimes other books, provided for the purpose, and pen and ink and paper. His razor, plate, and can, and basin, hang upon the wall or shine upon the little shelf. Freshwater is laid on in every cell, and he can draw it at his pleasure. During the day, his bedstead turns up against the wall and leaves more space for him to work in. His loom, or bench, or wheel, is there; and there he labors, sleeps and wakes, and counts the seasons as they change, and grows old.

The first man I saw, was seated at his loom, at work. He had been there six years and was to remain, I think, three more. He had been convicted as a receiver of stolen goods, but even after his long imprisonment, denied his guilt, and said he had been hardly dealt by. It was his second offense.

He stopped his work when we went in, took off his spectacles, and answered freely to everything that was said to him, but always with a strange kind of pause first, and in a low, thoughtful voice. He wore a paper hat of his own making and was pleased to have it noticed and commanded. He had very ingeniously manufactured a sort of Dutch clock from some disregarded odds and ends, and his vinegar-bottle served for the pendulum. Seeing me interested in this contrivance, he looked up at it with a great deal of pride, and said that he had been thinking of improving it and that he hoped the hammer and a little piece of broken glass beside it 'would play music before long.' He had extracted some colors from the yarn with which he worked, and painted a few poor figures on the wall. One, of a female, over the door, he called 'The Lady of the Lake.'

He smiled as I looked at these contrivances to while away the time; but when I looked from them to him, I saw that his lip trembled, and could have counted the beating of his heart. I forget how it came about, but some allusion was made to his having a wife. He shook his head at the word, turned aside, and covered his face with his hands.

' But you are resigned now!' said one of the gentlemen after a short pause, during which he had resumed his former manner. He answered with a sigh that seemed quite reckless in its hopelessness, 'Oh yes, oh yes! I am resigned to it.' 'And are a better man, you think?' 'Well, I hope so: I'm sure I hope I may be.' 'And time goes pretty quickly?' 'Time is very long gentlemen, within these four walls!'

He gazed about him - Heaven only knows how wearily! - as he said these words; and in the act of doing so, fell into a strange stare as if he had forgotten something. A moment afterward he sighed heavily, put on his spectacles, and went about his work again.

In another cell, there was a German, sentenced to five years' imprisonment for larceny, two of which had just expired. With colors procured in the same manner, he had painted every inch of the walls and ceiling quite beautifully. He had laid out the few feet of ground, behind, with exquisite neatness, and had made a little bed in the center, that looked, by-the-bye, like a grave. The taste and ingenuity he had displayed in everything were most extraordinary; and yet a more dejected, heart-broken, wretched creature, it would be difficult to imagine. I never saw such a picture of forlorn affliction and distress of mind. My heart bled for him; and when the tears ran down his cheeks, and he took one of the visitors aside, to ask, with his trembling hands nervously clutching at his coat to detain him, whether there was no hope of his dismal sentence being commuted, the spectacle was really too painful to witness. I never saw or heard of any kind of misery that impressed me more than the wretchedness of this man.

In a third cell, was a tall, strong black, a burglar, working at his proper trade of making screws and the like. His time was nearly out. He was not only a very dexterous thief, but was notorious for his boldness and hardihood, and for the number of his previous convictions. He entertained us with a long account of his achievements, which he narrated with such infinite relish, that he actually seemed to lick his lips as he told us racy anecdotes of stolen plate, and of old ladies whom he had watched as they sat at windows in silver spectacles (he had plainly had an eye to their metal even from the other side of the street) and had afterward robbed. This fellow, upon the slightest encouragement, would have mingled with his professional recollections the most detestable cant; but I am very much mistaken if he could have surpassed the unmitigated hypocrisy with which he declared that he blessed the day on which he came into that prison and that he never would commit another robbery as long as he lived.

There was one man who was allowed, as an indulgence, to keep rabbits. His room having rather a close smell in consequence, they called to him at the door to come out into the passage. He complied of course and stood to shake his haggard face in the unwonted sunlight of the great window, looking as wan and unearthly as if he had been summoned from the grave. He had a white rabbit in his breast; and when the little creature, getting down upon the ground, stole back into the cell, and he, being dismissed, crept timidly after it, I thought it would have been very hard to say in what respect the man was the nobler animal of the two.

There was an English thief, who had been there but a few days out of seven years: a villainous, low-browed, thin-lipped fellow, with a white face; who had as yet no relish for visitors, and who, but for the additional penalty, would have gladly stabbed me with his shoemaker's knife. There was another German who had entered the jail but yesterday, and who started from his bed when we looked in, and pleaded, in his broken English, very hard for work. There was a poet, who after doing two days' work in every four-and-twenty hours, one for himself and one for the prison, wrote verses about ships (he was by trade a mariner), and 'the maddening wine-cup,' and his friends at home. There were very many of them. Some reddened at the sight of visitors, and some turned very pale. Some two or three had prisoner nurses with them, for they were very sick; and one, a fat old negro whose leg had been taken off within the jail, had for his attendant a classical scholar and an accomplished surgeon, himself a prisoner likewise. Sitting upon the stairs, engaged in some slight work, was a pretty colored boy. 'Is there no refuge for young criminals in Philadelphia, then?' said I. 'Yes, but only for white children.' Noble aristocracy in crime.

There was a sailor who had been there upwards of eleven years, and who in a few months' time would be free. Eleven years of solitary confinement!

' I am very glad to hear your time is nearly out.' What does he say? Nothing. Why does he stare at his hands, and pick the flesh upon his fingers, and raise his eyes for an instant, every now and then, to those bare walls which have seen his head turn grey? It is a way he has sometimes.

Does he never look men in the face, and does he always pluck at those hands of his, as though he were bent on parting skin and bone? It is his humor: nothing more.

It is his humor too, to say that he does not look forward to going out; that he is not glad the time is drawing near; that he did look forward to it once, but that was very long ago; that he has lost all care for everything. It is his humor to be a helpless, crushed, and broken man. And, Heaven be his witness that he has his humor thoroughly gratified!

There were three young women in adjoining cells, all convicted at the same time of a conspiracy to rob their prosecutor. In the silence and solitude of their lives, they had grown to be quite beautiful. Their looks were very sad and might have moved the sternest visitor to tears, but not to that kind of sorrow which the contemplation of the men awakens. One was a young girl; not twenty, as I recollect; whose snow-white room was hung with the work of some former prisoner, and upon whose downcast face the sun in all its splendor shone down through the high chink in the wall, where one narrow strip of bright blue sky was visible. She was very penitent and quiet; had come to be resigned, she said (and I believe her); and had a mind at peace. 'In a word, you are happy here?' said one of my companions. She struggled - she did struggle very hard - to answer, Yes; but raising her eyes, and meeting that glimpse of freedom overhead, she burst into tears, and said, 'She tried to be; she uttered no complaint, but it was natural that she should sometimes long to go out of that one cell: she could not help THAT,' she sobbed, poor thing!

I went from cell to cell that day; and every face I saw, or word I heard, or incident I noted, is present to my mind in all its painfulness. But let me pass them by, for one, more pleasant, a glance of a prison on the same plan which I afterward saw at Pittsburgh.

When I had gone over that, in the same manner, I asked the governor if he had any person in his charge who was shortly going out. He had one, he said, whose time was up the next day; but he had only been a prisoner two years.

Two years! I looked back through two years of my own life - out of jail, prosperous, happy, surrounded by blessings, comforts, good fortune - and thought how wide a gap it was, and how long those two years passed in solitary captivity would have been. I have the face of this man, who was going to be released the next day, before me now. It is almost more memorable in its happiness than the other faces in their misery. How easy and how natural it was for him to say that the system was a good one; and that the time went 'pretty quick - considering;' and that when a man once felt that he had offended the law, and must satisfy it, 'he got along, somehow:' and so forth!

'What did he call you back to say to you, in that strange flutter?' I asked of my conductor when he had locked the door and joined me in the passage.

'Oh! That he was afraid the soles of his boots were not fit for walking, as they were a good deal worn when he came in; and that he would thank me very much to have them mended, ready.'

Those boots had been taken off his feet, and put away with the rest of his clothes, two years before!

I took that opportunity of inquiring how they conducted themselves immediately before going out; adding that I presumed they trembled very much.

'Well, it's not so much a trembling,' was the answer - 'though they do quiver - as a complete derangement of the nervous system. They can't sign their names to the book; sometimes can't even hold the pen; look about 'em without appearing to know why, or where they are; and sometimes get up and sit down again, twenty times in a minute. This is when they're in the office, where they are taken with the hood on, as they were brought in. When they get outside the gate, they stop, and look first one way and then the other; not knowing which to take. Sometimes they stagger as if they were drunk, and sometimes are forced to lean against the fence, they're so bad:- but they clear off in course of time.'

As I walked among these solitary cells, and looked at the faces of the men within them, I tried to picture to myself the thoughts and feelings natural to their condition. I imagined the hood just taken off, and the scene of their captivity disclosed to them in all its dismal monotony.

At first, the man is stunned. His confinement is a hideous vision, and his old life a reality. He throws himself upon his bed and lies there abandoned to despair. By degrees, the insupportable solitude and barrenness of the place rouse him from this stupor, and when the trap in his grated door is opened, he humbly begs and prays for work. 'Give me some work to do, or I shall go raving mad!'

He has it; and by fits and starts applies himself to labour; but every now and then there comes upon him a burning sense of the years that must be wasted in that stone coffin, and an agony so piercing in the recollection of those who are hidden from his view and knowledge, that he starts from his seat and striding up and down the narrow room with both hands clasped on his uplifted head, hears spirits tempting him to beat his brains out on the wall.

Again he falls upon his bed, and lies there, moaning. Suddenly he starts up, wondering whether any other man is near; whether there is another cell like that on either side of him: and listens keenly.

There is no sound, but other prisoners may be near for all that. He remembers to have heard once, when he little thought of coming here himself, that the cells were so constructed that the prisoners could not hear each other, though the officers could hear them.

Where is the nearest man - upon the right, or on the left? or is there one in both directions? Where is he sitting now - with his face to the light? or is he walking to and fro? How is he dressed? Has he been here long? Is he much worn away? Is he very white and specter-like? Does HE think of his neighbor too?

Scarcely venturing to breathe, and listening while he thinks, he conjures up a figure with his back towards him and imagines it moving about in this next cell. He has no idea of the face, but he is certain of the dark form of a stooping man. In the cell upon the other side, he puts another figure, whose face is hidden from him also. Day after day, and often when he wakes up in the middle of the night, he thinks of these two men until he is almost distracted. He never changes them. There they are always as he first imagined them - an old man on the right; a younger man upon the left - whose hidden features torture him to death, and have a mystery that makes him tremble.

The weary days pass on with solemn pace, like mourners at a funeral; and slowly he begins to feel that the white walls of the cell have something dreadful in them: that their color is horrible: that their smooth surface chills his blood: that there is one hateful corner which torments him. Every morning when he wakes, he hides his head beneath the coverlet and shudders to see the ghastly ceiling looking down upon him. The blessed light of day itself peeps in, an ugly phantom face, through the unchangeable crevice which is his prison window.

By slow but sure degrees, the terrors of that hateful corner swell until they beset him at all times; invade his rest, make his dreams hideous, and his nights dreadful. At first, he took a strange dislike to it; feeling as though it gave birth in his brain to something of corresponding shape, which ought not to be there, and racked his head with pains. Then he began to fear it, then to dream of it, and of men whispering its name and pointing to it. Then he could not bear to look at it, nor yet to turn his back upon it. Now, it is every night the lurking-place of a ghost: a shadow:- a silent something, horrible to see, but whether bird, or beast, or muffled human shape, he cannot tell.

When he is in his cell by day, he fears the little yard without. When he is in the yard, he dreads to re-enter the cell. When night comes, there stands the phantom in the corner. If he has the courage to stand in its place, and drive it out (he had once: being desperate), it broods upon his bed. In the twilight, and always at the same hour, a voice calls to him by name; as the darkness thickens, his Loom begins to live; and even that, his comfort, is a hideous figure, watching him till daybreak.

Again, by slow degrees, these horrible fancies depart from him one by one: returning sometimes, unexpectedly, but at longer intervals, and in less alarming shapes. He has talked upon religious matters with the gentleman who visits him, and has read his Bible, and has written a prayer upon his slate, and hung it up as a kind of protection, and an assurance of Heavenly companionship. He dreams now, sometimes, of his children or his wife, but is sure that they are dead, or have deserted him. He is easily moved to tears; is gentle, submissive, and broken-spirited. Occasionally, the old agony comes back: a very little thing will revive it; even a familiar sound, or the scent of summer flowers in the air; but it does not last long, now: for the world without, has come to be the vision, and this solitary life, the sad reality.

If his term of imprisonment be short - I mean comparatively, for short it cannot be - the last half year is almost worse than all; for then he thinks the prison will take fire and he be burnt in the ruins, or that he is doomed to die within the walls, or that he will be detained on some false charge and sentenced for another term: or that something, no matter what, must happen to prevent his going at large. And this is natural and impossible to be reasoned against, because, after his long separation from human life, and his great suffering, any event will appear to him more probable in the contemplation, than the being restored to liberty and his fellow-creatures.

If his period of confinement has been very long, the prospect of release bewilders and confuses him. His broken heart may flutter for a moment, when he thinks of the world outside, and what it might have been to him in all those lonely years, but that is all. The cell-door has been closed too long on all its hopes and cares. Better to have hanged him in the beginning than bring him to this pass, and send him forth to mingle with his kind, who are his kind no more.

On the haggard face of every man among these prisoners, the same expression sat. I know not what to liken it to. It had something of that strained attention which we see upon the faces of the blind and deaf, mingled with a kind of horror, as though they had all been secretly terrified. In every little chamber that I entered, and at every grate through which I looked, I seemed to see the same appalling countenance. It lives in my memory, with the fascination of a remarkable picture. Parade before my eyes, a hundred men, with one among the newly released from this solitary suffering, and I would point him out.

The faces of the women, as I have said, it humanizes and refines. Whether this is because of their better nature, which is elicited in solitude, or because of their being gentler creatures, of greater patience and longer suffering, I do not know; but so it is. That the punishment is nevertheless, to my thinking, fully as cruel and as wrong in their case, as in that of the men, I need scarcely add.

My firm conviction is that, independent of the mental anguish it occasions - an anguish so acute and so tremendous, that all images of it must fall far short of the reality - it wears the mind into a morbid state, which renders it unfit for the rough contact and busy action of the world. It is my fixed opinion that those who have undergone this punishment MUST pass into society again morally unhealthy and diseased. There are many instances on record, of men who have chosen, or have been condemned, to lives of perfect solitude, but I scarcely remember one, even among sages of strong and vigorous intellect, where its effect has not become apparent, in some disordered train of thought, or some gloomy hallucination. What monstrous phantoms, bred of despondency and doubt, and born and reared in solitude, have stalked upon the earth, making creation ugly, and darkening the face of Heaven!

Suicides are rare among these prisoners: are almost, indeed, unknown. But no argument in favor of the system can reasonably be deduced from this circumstance, although it is very often urged. All men who have made diseases of the mind their study, know perfectly well that such extreme depression and despair as will change the whole character, and beat down all its powers of elasticity and self-resistance, may be at work within a man, and yet stop short of self-destruction. This is a common case.

That it makes the senses dull, and by degrees impairs the bodily faculties, I am quite sure. I remarked to those who were with me in this very establishment at Philadelphia, that the criminals who had been there long, were deaf. They, who were in the habit of seeing these men constantly, were perfectly amazed at the idea, which they regarded as groundless and fanciful. And yet the very first prisoner to whom they appealed - one of their own selection confirmed my impression (which was unknown to him) instantly, and said, with a genuine air it was impossible to doubt, that he couldn't think how it happened, but he WAS growing very dull of hearing.

That it is a singularly unequal punishment, and affects the worst man least, there is no doubt. In its superior efficiency as a means of reformation, compared with that other code of regulations which allows the prisoners to work in a company without communicating together, I have not the smallest faith. All the instances of reformation that were mentioned to me were of a kind that might have been - and I have no doubt whatever, in my own mind, would have been - equally well brought about by the Silent System. With regard to such men as the negro burglar and the English thief, even the most enthusiastic have scarcely any hope of their conversion.

It seems to me that the objection that nothing wholesome or good has ever had its growth in such unnatural solitude, and that even a dog or any of the more intelligent among beasts, would pine, and mope, and rust away, beneath its influence, would be in itself a sufficient argument against this system. But when we recollect, in addition, how very cruel and severe it is, and that a solitary life is always liable to peculiar and distinct objections of a most deplorable nature, which have arisen here, and call to mind, moreover, that the choice is not between this system and a bad or ill-considered one, but between it and another which has worked well, and is, in its whole design and practice, excellent; there is surely more than sufficient reason for abandoning a mode of punishment attended by so little hope or promise, and fraught, beyond dispute, with such a host of evils.

As a relief to its contemplation, I will close this chapter with a curious story arising out of the same theme, which was related to me, on the occasion of this visit, by some of the gentlemen concerned.

At one of the periodical meetings of the inspectors of this prison, a working man of Philadelphia presented himself before the Board, and earnestly requested to be placed in solitary confinement. On being asked what motive could possibly prompt him to make this strange demand, he answered that he had an irresistible propensity to get drunk; that he was constantly indulging it, to his great misery and ruin; that he had no power of resistance; that he wished to be put beyond the reach of temptation; and that he could think of no better way than this. It was pointed out to him, in reply, that the prison was for criminals who had been tried and sentenced by the law, and could not be made available for any such fanciful purposes; he was exhorted to abstain from intoxicating drinks, as he surely might if he would; and received other very good advice, with which he retired, exceedingly dissatisfied with the result of his application.

He came again, and again, and again, and was so very earnest and importunate, that at last they took counsel together, and said, 'He will certainly qualify himself for admission if we reject him any more. Let us shut him up. He will soon be glad to go away, and then we shall get rid of him.' So they made him sign a statement which would prevent his ever sustaining an action for false imprisonment, to the effect that his incarceration was voluntary, and of his own seeking; they requested him to take notice that the officer in attendance had orders to release him at any hour of the day or night, when he might knock upon his door for that purpose; but desired him to understand, that once going out, he would not be admitted any more. These conditions agreed upon, and he still remaining in the same mind, he was conducted to the prison, and shut up in one of the cells.

In this cell, the man, who had not the firmness to leave a glass of liquor standing untasted on a table before him - in this cell, in solitary confinement, and working every day at his trade of shoemaking, this man remained nearly two years. His health beginning to fail at the expiration of that time, the surgeon recommended that he should work occasionally in the garden; and as he liked the notion very much, he went about this new occupation with great cheerfulness.

He was digging here, one summer day, very industriously, when the wicket in the outer gate chanced to be left open: showing, beyond, the well-remembered dusty road and sunburnt fields. The way was as free to him as to any man living, but he no sooner raised his head and caught sight of it, all shining in the light, than, with the involuntary instinct of a prisoner, he cast away his spade, scampered off as fast as his legs would carry him, and never once looked back.

American Notes for General Circulation

by Charles Dickens, 1842

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (1)

|

| B. Franklin Parkway |

Philadelphia has straight streets and square blocks in all directions, by the hundreds. Just a few streets slant off at an oblique angle, and most of those, like Germantown Avenue, is following old Indian Trails. The one, cold-blooded, deliberate slant street is the Benjamin Franklin Parkway which essentially runs from City Hall to the acropolis holding the Art Museum aloft. Just whose idea it was is unclear, although the architect Horace Trumbauer gets most credit. The actual design was given to a Frenchman, Jacques Greber, presumably because it imitates the effect of the Champs d' Elysee in Paris -- a broad sweeping boulevard with lanes of trees along the side and in the medians. As things turned out, a simple idea was pretty hard to put into practice. First of all, plenty of people in Philadelphia don't like anything if it's French, and an even larger number don't like the idea of messing around with our nice traditional system of squares at taxpayer expense. The people who lived in the area were naturally upset to see the ends of blocks chopped off, destroying the corner property entirely and exposing the backyards of the neighbors to public view. At the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the Pennsylvania Railroad's Chinese Wall cut off the center of town from "North of Market" , and the Parkway thus created a triangle of desolation that could only recover when the Swan Fountain appeared, named

|

| Swan fountain |

after the President of the Philadelphia Fountain Society. The sculpturing was done by Alexander Stirling Calder, the son of the sculptor (Alexander Milne Calder) of William Penn atop City Hall. The original design made the mistake of planting all the trees as red oaks, and so most of them died of the same disease at the same time, requiring replacement with mixed varieties of trees that would not be so susceptible to epidemics. People were reluctant to live in the isolated triangle of land to the South of the Parkway, and also in the strip of land North of the Parkway up the steep hill to Eastern State Penitentiary on Fairmount Avenue. Accordingly, the land was filled with public buildings, including the semi-prison for adolescents, the Central Detective Bureau, and so on. The deep cut for the railroad spur connecting the Baltimore and Ohio (along the Schuylkill) with the Reading Railroad running out of 12th and Market, didn't help encourage people to raise their children in the area, either. And that wasn't all. The Swan Fountain was designed in such a way that you couldn't get underneath it to change a light bulb, so a set of tunnels had to be dug underneath the fountain plaza as an afterthought. Planting the plaza with Paulownia trees was a stroke of genius. Although the blue blossoms are only spectacular for one week out of fifty-two, the massive limbs are always striking, even in the dead of winter.The Rodin Museum

came along, and although it is a little isolated, is a grand display in the same spirit as the boulevard itself, including the modernist sculpture of Alexander Calder. There is talk of creating a museum on the Parkway for the three generations of Calder's, and even agitation to bring the Barnes Museum in from Merion. With the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Franklin Institute and the Art Museum itself, the boulevard is still growing and evolving.

When traffic is heavy, people just want to get home as fast as possible, but most of the time the Parkway uplifts the soul, just as it was intended to. It's an outdoor thing, not an interior one, and there is something symbolic about the famous movie run of Rocky, pounding up the stairs to turn, holding up his victorious arms, to a breathtaking view of the city. But remember, although now closely associated with the Art Museum, he never went inside.

Benjamin Franklin Parkway (2)

|

| Art Museum |

There are a number of residential relics along the Parkway, but in general the idea seems to have been to put governmental buildings there, in a sort of French-like celebration of governmental glory. There is the Youth Study Center, the Department of Education administration building, the Boy Scouts of America, the Cathedral of St. Peter and St. Paul, and of course the tower of City Hall at one end and the Parthenon-like Art Museum at the other. But this is Philadelphia, and certain small touches of the town are tucked among the European grandee design.

For example, WFLN (now WWFM) the original FM classical music station, had its studio tucked in a little building just behind the Cathedral. Ralph Collier would interview authors and city visitors there during the lunch hour, in a studio that was little more than a closet, while someone else changed records in a room downstairs. Somebody from New York once said that Ralph didn't seem to know how good he really was, which is a way New Yorkers like to talk. Ralph was, the just about the only interviewer who had actually read your book before the interview. In 1997, WFLN was sold for forty million dollars, which ought to impress even a New Yorker.

Logan Circle is bigger than it looks, primarily because the windows are set 100 feet high. This came about after the anti-catholic riots of the Civil War era, which made it advisable to put stained glass higher than most people can throw rocks. There is usually a cardinal in residence at this cathedral, and Cardinal Bevilacqua the much-respected lawyer-cardinal is now just retiring in favor of an incoming occupant from St. Louis. Cardinal Krol was famous in the past for his opposition to Pope John's Vatican Constitution, which he refused to allow to be translated into English. Before that, was Cardinal Dougherty, who is remembered for being considerably overweight. Cardinals are addressed as Your Eminence, and Cardinal Dougherty was (very privately) referred to as You're Immense. He was perhaps most famous for the Legion of Decency , an effort to make motion pictures more socially acceptable. The story is told of a 12-year-old girl who stood up and told the Cardinal that she didn't agree with him, she liked movies. The next day, her father, the most powerful Catholic banker in Philadelphia, had to go to the Cardinal and humble himself to make amends.

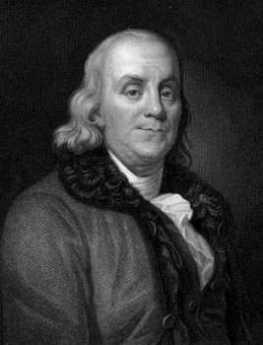

|

| Amelia Earhart |

Franklin Institute was originally on 7th Street, where the Atwater Kent Museum of Philadelphia History is now located. Much of the money to build it came from a $5000 bequest from Franklin himself, which was intended to demonstrate the power of compound interest over a period of time. It is part science museum, part memorial to Philadelphia's most famous citizen. It has a Planetarium, locomotive, a passenger airplane, Amelia Earhart's plane, a huge replica of a human heart, and thousands of working demonstrations of electrical phenomena. Ben Franklin's huge statue sits in a grand marble rotunda, where socialites occasionally hold receptions and weddings. But between the two extremes is the most interesting combination of museum and memorial -- a series of demonstrations of Franklin's most important scientific discoveries, utilizing the same instruments he used. Just a little effort at understanding these exhibits will convince any educated adult that Franklin was truly a genius.

Almost next door to the Franklin Institute is its more venerable neighbor, the Academy of Natural Sciences. The Academy is an offshoot of the American Philosophical Society, itself (originally founded by Franklin) and has a distinguished history of discovery and research of its own making, not merely a display of the work of others. Most school children will recognize the famous display of dinosaurs, including the First Dinosaur ever unearthed intact (in Haddonfield).

|

| Art Museum |

The Art Museum was intended to inspire awe, and it does. The builders ran out of money before the decorative friezes could be completed, but that even enhances its resemblance to the Parthenon, where the friezes were blown off in various wars. It's a little hard to know how to respond to the criticism that the building overwhelms its contents. Perhaps it is true that the creaking floorboards in Madrid's Prado Museum show off the treasures on its walls, but there is also little doubt that Spain (or Boston) would replace the floors if it could afford to. Although the City of Philadelphia has a little trouble finding the money to maintain and guard the Museum, the masonry is ultra-solid, it's very big, and will endure for ages to come. The collections slowly grow, benefaction by benefaction. The traveling exhibits are clearly the center of Philadelphia culture. And there, at the top of the stairs without any clothes on, is Diana of fame and fable. Her perfectly straight back is the true essence of the famously beautiful Philadelphia woman, like Fannie Kemble, Rebecca Gratz, Evelyn Nesbitt,Cornelia Otis Skinner, Grace Kelly, and Katherine Hepburn.

Spreading the City Out to Its Edges

The early city of Philadelphia was too tightly compressed and thus generated slums. By contrast, areas today become slums by being abandoned. Is there a middle way between these extremes that doesn't produce slums?

Almost up to the time the national capital moved away to the District of Columbia, the town of Philadelphia was compressed into an area of about a half square mile. Although there was a whole empty continent stretching to the Pacific Ocean on which to build houses, early Philadelphia built row houses and dark little alleys and packed people into them. These airless unsanitary conditions were excellent places to breed tuberculosis and typhoid fever, streptococcal epidemics, rheumatic fever and a host of other diseases of crowded city conditions. In a word, slums.

That was absolutely not what William Penn wanted to happen. His vision, as every Pennsylvania schoolchild is taught to recite, was that of a "Greene country Townie", with an acre of trees and grass for every house, and that's indeed the way it started. However, economics soon took over. Penn's proprietorship sold land right and left, and was particularly effective in selling land to people who stayed in England. They might someday come to America, perhaps. But the sea voyage was notoriously hard on the stomach, so in general speculators' idea was to rent the property to immigrants. Somehow the terms of trade then got slanted in favor of landlords and subdivides, and for a long time, it was cheaper to buy or rent developed land from the early owners than raw undeveloped land from the Proprietors. Every landlord feels this tension; even today, whether selling a new condominium tower or a whole state of raw land, every successful developer finds a way of managing this conflict between today's buyers and tomorrow's. Since history shows that Penn was not a particularly successful developer, he apparently did not manage many of the mundane issues very well; this was probably an example.

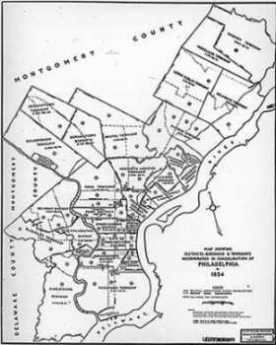

s district has to move away to find employment. New immigrants are then attracted to the cheap housing which becomes available, and the whole cycle of social commotion begins. If you take an Olympian view of the matter, Philadelphia now has 1.6 million inhabitants stretched out over an urban area adequate to house 5 million people. From time to time, you hear someone lament that the city boundaries should spread still further and enclose those prosperous suburbanites in the city tax system. That isn't going to happen, of course, because in a sense the city-county consolidation of 1850 was such an attempt. It seemed to work for a while, but over a long stretch of time, it was counter-productive. Los Angeles went even further, and there is now considerable talk of the suburban areas seceding. To impose political boundaries in ways that flout the underlying economics is what England and France attempted after the breakup of the Ottoman Empire, or what Europe generally did in the establishment of colonial boundaries in Africa. It seldom works out very well.

Our problem is one of attracting people from the far exurbs, which would like to get rid of urban sprawl, and bringing them into the abandoned wasteland of Northern Liberties, West and North Philadelphia. That's not a simple solution, since it amounts to asking someone to prefer North Philadelphia to Richboro in Bucks County, or Medford Lakes, or Odessa. But it isn't a hopeless problem, either. In both alternatives, the school systems and shopping districts start from scratch, the neighbors are what you make them. And transportation, particularly commuting, favors living near the city center.

But let's not get lost in details. The big picture is that it is now cheaper, an amenity for amenity, to live in the suburbs than downtown. And one of the main reasons is that it is cheaper to crowd houses together than to spread them out. It was particularly cheaper in colonial days, so we jammed houses together. It's cheaper in Arden, Delaware, the only local example of the effect of the Henry George single-tax system carried to extremes and never modified, and the vacation homes of Arden are absolutely packed together, as they are in most beachfront communities.

We packed ' em too tight together for three hundred years, and we don't need more row houses. We need five or six square miles of Greene country Townie.

The Walking Purchase

|

| William Penn and the Indians |

Any fair discussion of Quaker relations with the Indians must emphasize that almost all other colonists of the time regarded Indians as subhuman components of the local wilderness. Only William Penn was careful to treat the Indians as fellow human beings, entitled to fair play, dignity, and respect. Like a good politician, he entered into their games with enthusiasm and definitely earned their respect by outdoing them all in the broad jump contests. Even though he had bought the land from King Charles II, he took care to buy it a second time from the Indians, and for many decades was able to enforce the wise rule of never permitting settlers on the land before the Indians agreed to its purchase. After Penn's death, however, and particularly from 1726 to 1736, a major wave of German and Scotch-Irish immigration created an overwhelming population pressure on the seaboard areas, resulting in much unauthorized pioneering and settlement. Since William Penn spent only a few years in the colonies his agents chiefly James Logan, had long set the tone.

|

| Walking Purchase |

Logan had been equally famous for his many efforts to treat the Indians fairly, and the grounds of Stenton, his manor house, were often filled with Indians come to pay their respects. Against all this evidence of the benign attitudes of both Penn and Logan, there stands the episode of the Walking Purchase of 1737. No doubt about it, the Indians were treated badly.

In the triangle between the Neshaminy Creek and the Delaware River, the Delaware Indians agreed to a sale with the third side of the triangle established at a distance from Wrightstown, as far as a man could walk northward toward the Wind Gap in a day and a half. That was a common form of boundary for Indian land sales, and its distance was fairly well understood. In anticipation of pacing out the distance, the colonists sent out explorers to find the easiest path, then sent out woodsmen to clear a path in the forest, and selected three of the fastest runners in the colony to do the running. The pace was so fast that two of the runners had to drop out, and the third one nearly did so. The resulting boundary was nearly twice as far into the wilderness as was commonly accepted for the measurement, taking advantage of the sharp bend in the river which widened the land in question by a great deal. The Indians were so disgusted they refused to leave the territory. Logan had already made an agreement with the Iroquois nation, to whom the Delawares were subject, and the Delawares only surrendered the land when the Iroquois began to look as though they really would act as enforcers for the bargain. Although serious Indian warfare did not break out for another twenty years, the Walking Purchase went a long way toward convincing the Delaware tribe that the Quakers were no more trustworthy than the settlers in other colonies, and is said to have been on their minds when twenty years later they helped the French decimate General Braddock's army.

There will probably never be a clear resolution of the paradox of Quakers, particularly Logan, behaving in this reprehensible manner within a very long history of the unusually honorable treatment of the Indians. With William Penn now dead and gone, no doubt Logan was caught in a squeeze between the two rather dissolute sons of William Penn, neither of them Quaker, who had over-indebted themselves with high living and were pressing their agent to make land sales to pay for it. Then there was the pressure of the new German and Scotch-Irish immigrants, brought to the New World by real estate promises, and stranded in the seaport unable to complete their land purchases. Under this pressure, Logan may have been unduly persuaded that the 1684 treaties with the Indians, along with many other treaties and understandings, were all the legal justification he needed. Whatever the specifics of the situation at the time, it is now clear the Walking Purchase was a blot on the Quaker record that can never be entirely justified within the Quakers' own standards of fairness. Within the Society of Friends, whatever other English colonists might have done in their position, let alone what French and Spanish regularly did to the Indians, doesn't matter in the slightest.

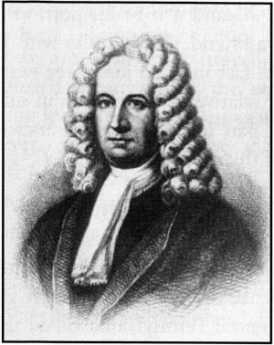

Logan, Franklin, Library

|

| The Library Company of Philadelphia |