5 Volumes

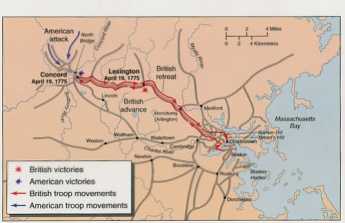

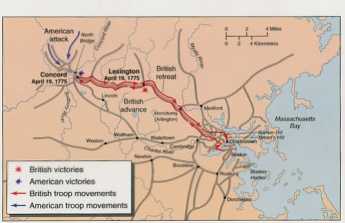

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Invaders of Pennsylvania

For a peaceful state, Pennsylvania has suffered many invasions. It's all been one-way; Pennsylvania has never invaded anyone else.

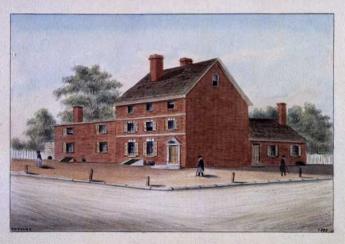

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

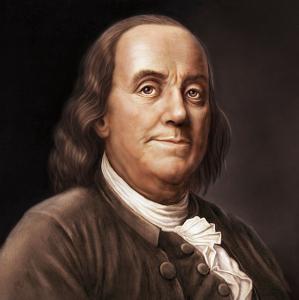

Revolutionary Philadelphia's Patriots

All kinds of people were patriots in 1776, and many of them were all mixed up about what was going on and how they stood. Hotheads in the London Coffee House stirred up about an inoffensive Tea Act, Scotch-Irish come here to escape the British Crown, the local artisan class and the local smuggler class, unexpectedly prospering under non-importation, and the local gentry -- offended to be denied seats in Parliament like other Englishmen. Pennsylvania wavered until Ben Franklin stepped forward with a plan.

The New Englanders had persuaded the South, but that wasn't enough. There had to be a unified rebellion over thirteen contiguous colonies to be successful. A neutral or even Loyalist Pennsylvania would give the British two American bases, one in Quebec and one in the Delaware Bay, splitting the rebellion into two islands; wouldn't work.

No one has satisfactorily explained why Franklin had fallen out with the Massachusetts Governor, Thomas Hutchinson, when years earlier the two men were avid collaborators on the Albany Plan of Union. And, although a North Carolina physician has been suggested, it remains uncertain who gave Franklin Hutchinson's inflammatory correspondence to publish. All we seem to know is that Franklin did publish the letters, enraging the British Ministry. And they nominated Alexander Wedderburn to excoriate him before he aristocracy of London for forty-five minutes of scathing oratorical torture borne in silence. By this time, Franklin had become one of the most famous and honored men of Europe; he was a celebrity. After the experience, Franklin retired to his home in what appears to have been an episode of depression, but soon packed up and sailed for America. On the day he stepped off the boat in Philadelphia, he became a member of the Continental Congress. Not only did he swing Pennsylvania opinion against King and Parliament, he brought a workable plan. He had reason to believe he could bring in France as an ally.

So, we declared our intention to be independent of England, and although it was a near thing, that's what we achieved. But two hundred years later looking back, is it disloyal to ask whether it would really make much difference if we were still part of Canada, and all of North America were still part of the British Commonwealth?

Free Quaker Meetinghouse

|

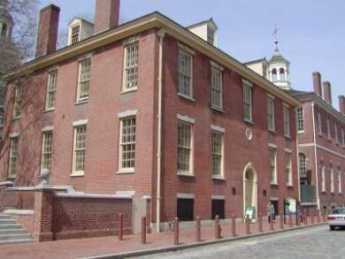

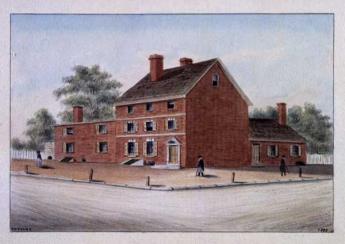

| Independence Hall |

Until this year, there was a Beautiful Mall stretching north from the State House (Independence Hall) to the approaches of the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. Concealing an enormous parking garage underneath it, the surface looked like a several-block lawn lined with flowering trees in the spring, framing the beautiful Eighteenth Century building (just as the mall in Washington leads up to the Washington Monument.)

Stretching from Independence Hall east to the Delaware River is another mall filled with historical buildings like Carpenters Hall , the First Bank(Girard's) and Second Bank (Biddle's), the Old and the New Custom houses, the American Philosophical Society, and others. The eastern mall was the property of the State of Pennsylvania when it was created, but it soon seemed more economical to the frugal rural legislature to turn it over to the federally funded National Park Service, joining the mall stretching northward. Well, somebody got another ton of federal money appropriated, and now we are filling the north mall with buildings which largely hide Independence Hall from the passersby. With just a few more Congressional earmarks, the imposing beauty of the mall will be submerged, but it hasn't quite reached that point yet. There is a perfectly enormous New Visitors Center, containing a couple of auditoriums and a big bookstore. Mostly the concept seems to be to provide a place to get out of the rain if you are an out of town visitor, provide public bathrooms, and a place to get a hot dog. At least the visitors center is red brick, and arched, with white woodwork. At the far northern end is an overwhelming stark granite block of a building, which will open July 4, 2003. It is a Constitution Center, claimed to be an interactive museum, and we shall see what we shall see. The looming monolith overwhelms and blocks the view to Independence Hall, and it better be good, when the insides get finished.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting |

If Independence Hall, which after all is a block long, is overwhelmed by the new constructions, the Free Quaker Meeting is totally hidden. This perfectly charming Eighteenths Century Quaker meetinghouse is just across Fifth Street from Benjamin Franklin's Grave, and just across Arch Street from the Constitution thing, completely in its shadow. Charles E. Peterson designed the restoration of the building, which had been added to and detracted from, over the years, but you can be sure its interior is now both beautiful and authentic. Before you go in, notice the inscription on the plaque under the northern eaves:

By General Subscription for the FREE QUAKERS. Erected in the Year of OUR LORD 1783 and of the EMPIRE 8.

The Quakers who built this building seem to have thought they were part of a new empire, but that implies an emperor, and of course, one was never created. Three years after the dedication of this building the Constitutional Convention met in the same Independence Hall, and our national form of government was somewhat strengthened from the Articles of Confederation also written here. Benjamin Franklin had a hand in both documents, but the first one was mainly composed by John Dickinson, and the second one by James Madison. If you go into the Free Quaker building, it seems to be a single large room with an interior balcony, and a couple of small staircases in the back leading down to what would presumably be restrooms. As a matter of fact, the Park Service extended the basement to include kitchen and dining room, and several offices for themselves which are a surprise if you are allowed to go down to see them.

|

| History of Free Quakers |

Charlie Peterson wrote a book about the restoration, but the main book about the spiritual history of this group was written by Charles Wetherill. Quakers, as everyone ought to know, are pacifists. The American Revolution put a number of them in a quandary because they agreed that Great Britain was injuring their rights by denying them a representative in the Parliament which ruled them but resorting to violence was another matter entirely. Eventually, a group did break away from the main Quaker church to fight for independence. They were prompt "readout of the meeting", the equivalent of being excommunicated, not allowed to worship in the regular meeting houses they had helped finance or to be buried in the church graveyards. Samuel Wetherill was one of the leaders of this group, just as his descendants are the most active today in the surviving historical society. Samuel created quite a furor, demanding to use the Orthodox meeting house and burial grounds. He was, in his own view, just as much a Quaker as the others since no doctrine is absolutely fixed in that religion, and was freely entitled to speak his mind to persuade others of the rightness of his sincere positions. The main body of Quakers would have none of it, and the Free Quakers were firmly expelled, forced to hold a public subscription and build their own meeting house. Wetherill of course personally knew every one of the members who expelled him, and there may be some truth to his loud, pointed and unchallenged contention that the true division was not between pacifists and fighters, but between Tories and advocates of Independence. Whatever the truth of these accusations, it does seem in retrospect that the split was fairly divided between wealthy established merchants, and small shopkeepers and artisans. Quite a few now-famous names appear on the rolls of the Free Quakers, like Timothy Matlack the actual Scribe of the Declaration of Independence document, Biddles, Lippincott, John Bartram,Crispins, Kembles, Trippes, and Wetherills. When the meeting had dwindled down in 1830 to two lone parishioners, one was a Wetherill, and the other was Betsy Ross, herself.

A comment is submitted by a reader:

I think your description of the Free Quakers oversimplifies their origins. It is true that Samuel Wetherill was disowned by Friends for his military activities. However, other Free Quaker leaders were bounced -- often years before the Revolution -- for other reasons. Timothy Matlack, for not paying his debts. Betsy Ross, for an improper marriage. Christopher Marshall, for counterfeiting. I haven't traced everyone listed as a member in the (1907?) Stackhouse history of the Free Quakers. But I did search in Quaker records for perhaps a dozen and found no records that people with those names had ever been Quakers. I think it would be more accurate to say of the Free Quakers that the Revolution drew together people of many different types and that when some of those people had things in common -- such as Quaker background -- they united around those things. (Posted by Mark E. Dixon )

The Jews in Colonial Philadelphia

|

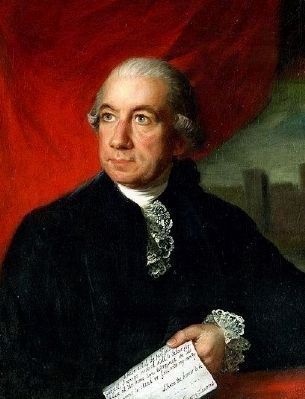

| Haym Salomon |

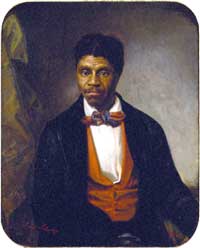

The word Sephardi is derived from the Hebrew word for Spain, where Jews were a prominent part of the Arab community for several hundred years. The Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, regarding the Sephardim as pro-Arab, drove them out of Spain and Portugal in 1492. They scattered widely, and only a small portion eventually got to the Western hemisphere. It is also helpful to know that Askenazic is the Hebrew word for German since this other main branch of the religion did not emigrate to America until later in the Nineteenth century in response to the suppression following the 1848 Revolutions. There are some important differences in liturgy, and occasional episodes of bad feeling between the two Jewish groups, some of it kept alive by issues arising in Israel. Historically, the Sephardim have had a greater tendency to assimilate in local cultures, both generally and particularly in Philadelphia. However, the most prominent Jew in the American Revolutionary War was Haym Salomon, who was born in Poland.

On leaving Spain, many Sephardim had gone to Amsterdam, and from there to the Dutch colonies hat accounts for their presence in the Delaware Bay as part of the Dutch settlements which preceded William Penn's arrival. The British conquest of the Dutch accounts for their subsequent local disappearance. However, it paradoxically also accounts for an influx from Curacao and other Caribbean Dutch colonies conquered by the British, usually favoring New York as a place to settle. Presumably, Sephardic feelings about the English were cautious at best. When the British occupied New York in the early days of the American Revolution, many Sephardim fled to Philadelphia, but largely returned to New York after the end of the Revolution. There was thus a double process of filtering out those who were unsympathetic with the British, and those who were attracted by seeing what Philadelphia represented.

Records were poorly kept in those days, and in civil wars, there are often reasons to be vague about your sympathies and activities. We know that Haym Salomon came to Philadelphia in 1774, grew very rich in association with Robert Morris, but died in poverty after a few years, now lying in an unmarked grave. It is a little unclear how he became rich, although all merchants involved in shipping did a little privateering, often described as piracy by the victims. It is also unclear how he became suddenly poor, although speculators in currency and land often make serious misjudgments. Robert Morris is himself a prime example.

The matter becomes of greater interest when Haym Salomon is sometimes referred to as one of the main financiers of the Revolution. Partly because of the ease of counterfeiting with the primitive printing technology of the time, the British had forbidden the use of paper money in the colonies as part of the Townshend Acts. While understandable, it caused great pain to unbalanced trade partners, and metal coins quickly migrated back to England, almost paralyzing colonial economies for lack of cash to transact local business. It probably caused a different sort of a pain to Benjamin Franklin, who derived much of his income from printing the currency of New Jersey. In particular, it kept cargoes trapped in port for lack of payment, which the annoyed British merchants mistook as an implementation of John Dickinson's proposal for deliberate "non-importation". In any event, Jewish merchants and bankers were well situated to find ways around currency blockages, sometimes using precious gems as substitutes for specie, and utilizing informal family networks scattered around the world. In civil wars, guns have to be bought and paid for, legalities get swept aside. There is said to be evidence that our ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, utilized Salomon to translate the French loans he had negotiated into the munitions which colonials needed. There is incidentally reason to believe that the Rothschild family established its great wealth by similar commodity dealings at the time of the Battle of Waterloo.

Just what it was that went so drastically wrong for Haym Salomon at the conclusion of our war for independence has not yet been made clear, perhaps never will be. He may have been caught in the uproar over the worthless Continental currency, his ships may have been captured, or he may have been trapped by the land speculation which ruined Robert Morris. But those were rough, tough times. We have the word of those who should know, that Salomon's service was essential to our achievement of Independence.

Carpenters Hall

|

| Carpenters Hall |

The birthplace of our nation is both smaller than you would expect and larger. The fire marshall now says no more than 83 people may rent it for a sit-down affair, or 103 for a stand-up gathering. However, the internal partitions have been removed from what was once a center-hall building with a meeting room on either side; it now is a large open room in the form of a Greek cross. At the time of the revolution, Benjamin Franklin's Library Company occupied the second floor, so the First Continental Congress had to find a way to do its work in the side rooms of the first floor, to the side of the center hall. There were 53 delegates, and presumably some staff and visitors.

That sounds rather crowded, but it was nevertheless the largest rentable public space in the city. John Adams arrived early for the convention, conniving with several other early arrivals at the City Tavern. Adams made the following notation in his diary: Monday. At ten the delegates all met at the City Tavern and walked to the Carpenters' Hall, where they took a view of the room, and of the chamber where is an excellent library; there is also a long entry where gentlemen may walk, and a convenient chamber opposite to the library. The general cry was, that this was a good room, and the question was put, whether we were satisfied with this room? and it passed in the affirmative." Alternative places to meet would have been in churches, which presented awkwardness, or in the State House (Independence Hall) which was then under the control of Tories.

|

| Continental Congress |

France and the rebellious colonies was a complicated one, with intrigue and mistrust at every turn. One interesting episode had to do with Franklin's library on the second floor. The French ministry had sent over a spy, to size up the colonists before the French risked too much on them. So, the spy was led up to the library and allowed to overhear some bellicose conversations going on downstairs -- thoroughly stage-managed for the benefit of the "hidden" French visitor.

The Carpenters Company was a guild of what we would now call builders and architects, and architects continue to use it. The first floor usually displays a few Windsor chairs dating to the Continental Congress, covered with a rich black patina that really lets you know what a patina was. Upstairs, the staff quarters are now, well, a little on the elegant side so you can't visit. The guild was formed in 1724, and fifty years later had just completed its building, in time for its historic role in 1774.

|

| Elfreth's Alley |

With the whole continent available for building, it is still not entirely clear why Colonial Philadelphia crowded itself into half a square mile, with crowded little row houses on crowded little alleys. But that's the way it was, now visible in the location of Carpenters' Hall down a little cobbled alley, in the center of a block. Elfreth's Alley gives you the same feeling, and perhaps Camac, Mole, and Latimer Streets. Carpenters' is a lovely little place, with lots of interesting features, but the main interest lies in what took place there. For that, you have to read a few books.

John Head, His Book of Account, 1718-1753

|

| American Philosophical Society |

Jay Robert Stiefel of of the Friends Advisory Board to the Library of the American Philosophical Society entertained the Right Angle Club at lunch recently, and among other things managed a brilliant demonstration of what real scholarship can accomplish. It's hard to imagine why the Vaux family, who lived on the grounds of what is now the Chestnut Hill Hospital and occasionally rode in Bentleys to the local train station, would keep a book of receipts of their cabinet maker ancestor for nearly three hundred years. But they did, and it's even harder to see why Jay Stiefel would devote long hours to puzzling over the receipts and payments for cabinets and clock cases of a 1720 joiner. Somehow he recognized that the shop activities of a wilderness village of 5000 residents encoded an important story of the Industrial Revolution, the economic difficulties of colonies, and the foundations of modern commerce. Just as the Rosetta stone told a story for thousands of years that no one troubled to read, John Head's account book told another one that sat unnoticed on that library shelf for six generations.

|

| Colonial Money |

The first story is an obvious one. Money in colonial days was mainly an entry in everybody's account book; today it is mainly an entry in computers. In the intervening three centuries, coins and currency made an appearance, flourished for a while as the tangible symbol of money, and then declined. Although Great Britain did not totally prohibit paper money in the colonies until 1775, in John Head's day, from 1718 to 1754, paper money was scarce and coins hard to come by. Because it was so easy to counterfeit paper money on the crude printing presses of the day, paper money was always questionable. Meanwhile, the balance of trade was so heavily in the direction of the colonies that the balance of payments was toward England. What few coins there were, quickly disappeared back to England, while local colonial commerce nearly strangled. The Quakers of Philadelphia all maintained careful books of account, and when it seemed a transaction was completed, the individual account books of buyer and seller were "squared". The credit default swap "crisis" of 2008 could be said to be a sharp reminder that we have returned to bookkeeping entries, but have badly neglected the Quaker process of squaring accounts. As the general public slowly acquires computer power of its own, it is slowly recognizing how far the banks, telephone companies, and department stores have wandered from routine mutual account reconciliation.

|

| John Head's Account Book |

From John Head's careful notations we learn it was routine for payment to be stretched out for months, but no interest was charged for late payment and no discounts were offered for ready money. It would be another century before it became routinely apparent that interest was the rent charged for money and the risk of intervening inflation, before final payment. In this way, artisans learned to be bankers.

And artisans learned to be merchants, too. In the little village of Philadelphia, chairs became part of the monetary system. In bartering cabinets for the money, John Head did not make chairs in his shop at 3rd and Mulberry (Arch Street) but would take them in partial payment for a cabinet, and then sell the chairs for the money. Many artisans made single components but nearly everyone was forced into bartering general furniture. Nobody was paid a salary. Indentured servants, apprenticeships trading labor for training, and even slavery benignly conducted, can be partially seen as efforts to construct an industrial society without payrolls. Everybody was in daily commerce with everybody else. Out of this constant trading came the efficiency step for which Quakers are famous: one price, no haggling.

One other thing jumps out at the modern reader from this book of account. No taxes. When taxes came, we had a revolution.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1517.htm

America in 1767

|

| Johann de Kalb |

Baron Johann de Kalb was to die a hero of the American Revolution in 1780, but in 1767 he was a spy for France, scouting out potential French opportunities in America. He made the following report to the French minister of foreign affairs, duc de Choiseul:

"Everywhere there are children swarming like broods of ducks, large fertile farms, flourishing industries, and harborsbarely able to hold the and fishing and Merchant Fleets

"Whatever may be done in London," judged de Kalb, "this country is growing too powerful to be much longer governed at such a distance."

- as cited by Walter A. MacDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner

REFERENCES

| Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History: 1585-1828: Walter A. McDougall ISBN-13: 978-0060197896 | Amazon |

Circular Letter: Boston Committee of Correspondance, May 1774

|

| Paul Revere |

"We have just received the copy of an Act of the British Parliament passed in the present session whereby the town of Boston is treated in a manner the most ignominious, cruel, and unjust. The Parliament has taken upon them, from the representations of our governor and other persons inimical to and deeply prejudiced against the inhabitants, to try, condemn, and by an Act to punish them, unheard; which would have been in violation of natural justice even if they had an acknowledged jurisdiction. They have ordered our port to be entirely shut up, leaving us barely so much of the means of subsistence as to keep us from perishing with cold and hunger; and it is said that [a] fleet of British ships of war is to block up our harbor until we shall make restitution to the East India Company for the loss of their tea, which was destroyed therein the winter past, obedience is paid to the laws and authority of Great Britain, and the revenue is duly collected. This Act fills the inhabitants with indignation. The more thinking part of those who have hitherto been in favor of the measures of the British government looks upon it as not to have been expected even from a barbarous state. This attack, though made immediately upon us, is doubtless designed for every other colony who will not surrender their sacred rights and liberties into the hands of an infamous ministry. Now, therefore, is the time when all should be united in opposition to this violation of the liberties of all. Their grand object is to divide the colonies. We are well informed that another bill is to be brought into Parliament to distinguish this from the other colonies by repealing some of the Acts which have been complained of and ease the American trade; but be assured, you will be called upon to surrender your rights if ever they should succeed in their attempts to suppress the spirit of liberty here. The single question then is, whether you consider Boston as now suffering in the common cause, and sensibly feel and resent the injury and affront offered to here. If you do (and we cannot believe otherwise), may we not from your approbation of our former conduct in defense of American liberty, rely on your suspending your trade with Great Britain at least, which it is acknowledged, will be a great but necessary sacrifice to the cause of liberty and will effectually defeat the design of this act of revenge. If this should be done, you will please to consider it will be, though voluntary suffering, greatly short of what we are called to endure under the immediate hand of tyranny.

"We desire your answer by the bearer; and after assuring you that, not in the least intimidated by this inhumane treatment, we are still determined to maintain to the utmost of our abilities the rights of America, we are, gentlemen,

"Your friends and fellow countrymen."

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

According to the records of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the following 48 persons were patients in the hospital on July 4, 1776:

| Richard Brinkinshire (Admitted 11/15/1775) | John Ridgeway (Admitted 12/26/1775) |

| James Chartier (Admitted 1/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/6/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) |

| Mary Yell (Admitted 2/7/1776l) | John Beckworth (Admitted 2/7/1776) |

| Bart. McCarty (Admitted 2/10/1776) | John King (Admitted 2/10/1776) |

| Robert Alden (Admitted 2/17/1776) | William Patterson (Admitted 3/6/1776) |

| Elizabeth Hanna (Admitted 3/9/1776) | John McMahon (Admitted 3/13/1776) |

| Mary Burgess (Admitted 3/23/1776) | Mary Anderson (Admitted 4/10/1776) |

| John Hatfield (Admitted 4/15/1776) | Eliza Haighn (Admitted 4/17/1776) |

| Charles Whitford (Admitted 4/24/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| Susanna Carrington (Admitted 5/8/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| William Johnson (Admitted 5/13/1776) | Lazarus Chesterfield (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| Mary Spieckel (Admitted 5/22/1776l) | William Edwards (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 5/23/1776, Lunatic) | Jane White (Admitted 5/25/1776) |

| Charles McGillop (Admitted 5/29/1776) | ---Fitzgerald (Admitted 6/1/1776) |

| Michael Rowe (Admitted 6/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 6/6/1776) |

| John Hughes (Admitted 6/12/1776) | Joseph Smith (Admitted 6/15/1776) |

| Esther Munro Lunda (Admitted 6/15/1776) | Mathew Coope (Admitted 6/19/1776) |

| Anne Patterson (Admitted 6/19/1776) | Thomas Savoury (Admitted 6/20/1776) |

| Rebecca Winter (Admitted 6/26/1776) | Elizabeth Manning (Admitted 6/26/1776) |

| Negro (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Elex. Scanvay (Admitted 6/24/1776) |

| Fanny Stewart (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Peter Barber (Admitted 6/29/1776) |

| Catherine Campbell (Admitted 6/29/1776) | Ann McGlauklin (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

| Elizabeth Lindsay (Admitted 7/3/1776) | Ann Jones (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

The records indicate the following diseases were the reason for admission of those patients. Although in Colonial times there was no medical delicacy to avoid offending readers, present privacy standards require that we strip the diagnoses from the name of the patient and list them independently. There is some overlap, sometimes making it difficult to judge which disorder caused the admission.

- Sore, poisoned or ulcerated legs: 16 cases

- Lunacy, mind or head disorders: 10 cases

- Syphilis: 7 cases

- Fever and Rheumatic fever: 7 cases

- Dropsy: 5 cases

- Gunshot: 4 cases

- Diabetes: 1

- Blindness with clear pupil: 1

- Spitting blood: 1 case

- Dislocated arm: 1 case

- Inflammation of face: 1 case

- Scurvy: 1 case

- broken arm: 1 case

The following physicians were elected at the Managers Meeting dated 5/13/1776:

- Dr. Thomas Bond

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Dr. John Redman

- Dr. William Shippen

- Dr. Adam Kuhn

- Dr. John Morgan

Fort Wilson: Philadelphia 1779

|

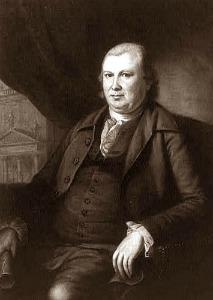

| James Wilson |

OCTOBER 4, 1779. The British had conquered then abandoned Philadelphia; an order was still only partially restored. Joseph Reed was President of the Continental Congress, inflation ("Not worth a Continental") was rampant, and food shortages were at near-famine levels because of self-defeating price controls. In a world turned upside down, Charles Willson Peale the painter was a leader of a radical group of admirers of Rousseau the French anarchist, called the Constitutionalist Party, leaning in the bloody direction actually followed by the French Revolution in 1789. Peale was quick to admit he had no clue what to do with his leadership position and soon resigned it in favor of painting portraits of the wealthy. Others had deserted the occupied city, and many had not yet returned. The Quakers of the city hunkered down, more or less adhering to earlier instruction from the London Yearly Meeting to stay away from any politics involving war taxes. About two hundred militia roamed the city streets making trouble for anyone they could plausibly blame for the breakdown of civil order. Philadelphia was as close to anarchy as it would ever become; the focus of anger was against the pacifist Quakers, the rich merchants, and James Wilson the lawyer.

|

| Fort Wilson |

Wilson had enraged the radicals by defending Tories in court, much as John Adams got in trouble for defending British troops involved in the Boston Massacre; Ben Franklin advised Wilson to leave town. It is still possible to walk the full extent of the battle of Fort Wilson in a few minutes, and the tourist bureau has marked it out. Begin with the Quaker Meeting at Fourth and Arch. A few wandering militiamen caught Jonathan Drinker, Thomas Story, Buckridge Sims, and Matthew Johns emerging from the Quaker church, and rounded them up as prisoners. The Quakers were marched down the street for uncertain purposes when the militia encountered a group of prominent merchants emerging from the City Tavern. Unlike the meek Quakers, Robert Morris and John Cadwalader the leader of the City Troop ordered the militia to release the prisoners, behave themselves, and disperse; Timothy Matlack shouted orders. It was exactly the wrong stance to take, and about thirty prominent citizens were soon driven to retreat to the large brick house of James Wilson, at the corner of Third and Walnut, known forever afterward as Fort Wilson. Doors were barred, windows manned, and Fort Wilson was soon surrounded by an armed, shouting, mob. Lieutenant Robert Campbell leaned out a third story window and was soon dropped dead by a lucky bullet. It remains in dispute whether or not he fired first. Crowbars were sought, the back door forced open, but the angry attackers scattered after fusillades from inside.

|

| Joseph Reed |

Down the street came President Reed on horseback, ordering the militia to disperse, with Timothy Matlack at his side; both men were well-known radicals, here switching sides to maintain law and order. The City Troop arrived, an order was given the cavalry to Assault Every Armed Man. The radicals were finally dispersed by this makeshift cavalry charge, cutting and slashing its way through the dazed militia. When it was over, five defenders were dead and about twenty wounded. Among the militia, the casualties were heavier but inaccurately reported. Robert Morris took James Wilson in hand and retreated to his mansion at Lemon Hill; Wilson was the founder of America's first law school. Among other defenders huddled in Fort Wilson were some of the future framers of the Constitution from Pennsylvania: General Thomas Mifflin, Wilson, Morris, George Clymer. Equally important was the deep impression left on radical leaders like Reed and Matlack, and Henry Laurens, who could see how close the whole war effort was to dissolution, for lack of firm control. Inflation continued but the center-productive price control system was abandoned and never revived; the Patriots had a bad scare, and the heedless radicals forced to confront the potentially disastrous consequences of their own amateur performance when entrusted with the power and responsibility they had just been demanding. It was one of those rare moments in a nation's history when the way suddenly opens to previously unthinkable actions.

|

| Timothy Matlack |

The Battle of Fort Wilson was the only Revolutionary War battle fought within Philadelphia city limits; a revolution within a revolution, every participant was a Rebel patriot. Reed and Matlack were the two most visibly appalled by the whole uproar, forced by circumstances to attack the forces of their own political persuasion. But it seems very certain that Robert Morris and the other prosperous idealists were also left with an indelible conviction that even a confederation must maintain central command and discipline with an iron will, or all might be lost. A knowledgable French observer estimated that Robert Morris then owned assets worth eight million dollars, an almost unimaginable sum for the time. But he would lose every penny if effective political control could not be restored. A few days later in the October election, he and all the other Republican (conservative) officials lost their seats. It did not matter; Morris then knew what to do, and his opposition didn't.

City Troop

|

| First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC) |

On 23rd Street, just South of Market, stands a gloomy Victorian castle with big doors opening to the street. It's the armory, housing the First Troop, Philadelphia City Cavalry (FTPCC). The organization is a real fighting unit of the Pennsylvania National Guard, participating with distinction in every war America has fought. Originally a horse cavalry, the unit now drives tanks, except for recreation and on ceremonial occasions. It lays claim to being the oldest military unit in America, although there have been several minor name changes since the days when the City Troop accompanied General Washington to take command of the troops in Boston. Their dress uniforms are pretty splashy, especially on horseback, and they have to pay for them, themselves.

Furthermore, they are required to donate all of their military pay toward the upkeep of the unit and its activities. Although the first step in membership is to become a real member of the National Guard, election to the Troop itself is truly an election, carefully screened after prospective members have been observed and evaluated at invited Troop functions. These soldiers are wealthy, athletic, mostly pretty handsome, and almost invariably well-connected socially. You could almost make up the rest from these essential ingredients. This is the innermost core of Philadelphia society, and it is intensely and sincerely patriotic.

Others have noticed that National Guard duty itself takes up many weekends and much of summer vacation. Add to that the many Troop dinners, the horsemanship activities, the debutante balls, the Chesapeake sailing cruises, the national and local ceremonies, the weddings and funerals for members -- and actually fighting wars overseas. The members of the Troop spend so much of their time on Troop-related activities, that they become both intensely loyal to each other, and necessarily somewhat withdrawn from other people. They gravitate to polo, the Racquet Club, the Savoy, the Orpheus, and the financial world.

There may be an important insight into the generation turmoils to be derived from this. There was once a time when most professions likewise absorbed the lives of their members, with professional clubs and entertainments confining the social life of the member by leaving little time for anything else. But in recent years most occupational and professional societies are experiencing a loss of membership and enthusiasm, leading to the bewildering question of "Where are the younger members, any more?" The pre-fabricated answer is that younger people now want to devote their quality time to their families, but if you believe that, you will believe anything. Let's face it; when one activity absorbs all of your time, it confines you. There have to be some important benefits to being so confined, and even so, it chafes a little. Those of us who are not baby boomers can see that being a slave to intra-generational consensus is only to be a slave in a different way. The remarkable thing is that the baby boomers fail to see it, themselves.

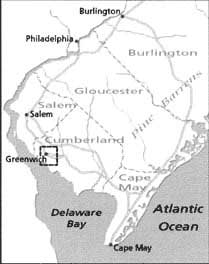

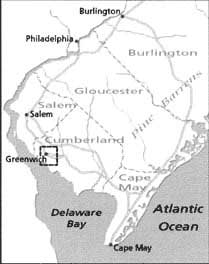

Greenwich, Where?

|

| Greenwich NJ |

If you sail north up the Delaware Bay, you would go past Rehoboth, Lewes, Dover, New Castle, Wilmington -- on the left, or Delaware side. On the right, or New Jersey side, it's a long way from Cape May to Salem, the first town of any consequence. That is, the Jersey side of the riverbank is still comparatively uninhabited. When the first settlers came along, with vast areas to choose among, it might have seemed attractive to settle on the Delaware side, because the peninsular nature of what is now called Delmarva (Del-Mar-Va) would provide land access to two large navigable bays, the Delaware, and the Chesapeake. To go all the way up the Delaware to what is now Pennsylvania would give trading access to a whole continent, so that eventually proved to be where immigration was headed. But as a matter of fact, the marshy Jersey shore seemed more attractive for settlement by the earlier settlers.

A settler has to think about starving the first year or two, because trees have to be cut down, and stumps pulled up before the land can even be plowed. After that, comes planting and growing, then finally harvesting. Trees, behind which Indians can hide, are a bad thing all around in the eyes of a settler. The flat swampy meadows of the Jersey bank were just exactly what the Dutch knew how to manage. Dam up the creeks and drain the ground, and you will soon have lots of lands ready for the plow, without any confounded trees. By the end of the seventeenth century, the English who had made the mistake of settling in rocky Connecticut finally saw what the Dutch were able to do, and came down to take it away from them.

|

| Greenwich scenery |

That's why there is a Salem, New Jersey, and also a Greenwich, New Jersey. Greenwich ( around here they pronounce it green-witch) had 870 residents at the last census. It is one of the cutest little colonial villages you are likely to encounter. The local historians refer to it as an unreconstructed Williamsburg, drawing prideful attention to the fact that these houses were really built in the colonial period, and are in no way imitation reconstructions. The isolated charm of this place is in large part due to being surrounded by a maze of wandering creeks, so visitors by land travel don't get there in time for lunch unless they take great care to follow a local road map. If you arrive by water, it's no problem; just navigate up the crooked and twisting Cohansey River.

Although pioneer settlement was much earlier, the oldest house still standing in that rather damp area was built in 1730. Things are pretty much the way they were before the American Revolution because the Calvinists who settled here were not prepared for the Jersey mosquito, which obviously is abundant in such a marshy area. With the mosquito comes relapsing (Vivax, malaria, black water (Falciparum) malaria, and Dengue Fever (graphically known locally as break-bone fever). As a matter of fact, encephalitis is also mosquito-borne. When you don't understand the insect carrier situation, survival in such an environment depends on local fables and lore, like going to the mountains for the summer after the planting season, and only returning at harvest time. That sounds to a New Englander newcomer like a superstitious cloak for lazy living, especially since masses of fish come up the river in teeming waves, looking for mosquitoes to eat. So, Greenwich is charming, but it never was thriving.

Working hard to find something to say about the town, it would appear that Paul Revere himself came riding into Greenwich in December 1774, urging the town to join their Boston relatives in the destruction of tea belonging to the British East India Company. Greenwich accordingly had a public tea burning on December 22. Since the more notorious Boston tea party took place on December 16, 1773, and the British Tea Act was passed in May, 1773, it is not exactly accurate to say the rebellion spread like wildfire. One has to suppose that the inflammatory tale told to the local farmers by Paul Revere was likely a little enhanced, since a careful recounting of the events in Boston suggests a number of ways the uproar might have been avoided if Samuel Adams and his friends had been less provocative. Or if Massachusetts Royal Governor Thomas Hutchinson had been less flighty. Or for that matter, if Benjamin Franklin had restrained himself when he got hold of Hutchinson's letters at a critical moment when he was in London. In retrospect, the best model for behavior was provided by the Royal Navy; the whole Boston Tea Party was surrounded by armed British naval vessels, who did not lift a finger throughout the demonstration.

Anyway, little Greenwich had its minute of fame with a tea burning. Otherwise, it has had a very quiet existence for three centuries.

REFERENCES

| Paul Revere & The World He Lived In | Amazon |

America's First Medical Interne, Jacob Ehrenzeller

This Indenture Witnesseth, That Jacob Ehrenzeller, son of Jacob Ehrenzeller of the City of Philadelphia hath put himself, and by these presents, with consent of his said father, doth voluntarily, and of his own free Will and Accord, put himself Apprentice to the Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital to learn the Art, Trade and Mystery, and after the Manner of an Apprentice to serve the said managers from the Day of the Date hereof, for and during, to the full End and Term of five years and three months next ensuing. During all of that Term, the said Apprentice his said Master faithfully shall serve, his Secrets keep, his lawful Commands every where readily obey. He shall do no Damage to his said Master, nor see it to be done by others, without letting or giving Notice thereof to his said Master. He shall not waste his said Master's Goods, nor lend them unlawfully to any. He shall not commit Fornication, nor contract Matrimony within the said Term.

He shall not play at Cards, Dice or any other unlawful Game, whereby his said Master may have Damage. With his own Goods, nor the Goods of others, without license from his said Master, he shall neither buy nor sell. He shall not absent himself Day nor Night from his said Master's Service without his leave: nor haunt Ale-houses, Taverns or Playhouses; but in all Things behave himself as a faithful Apprentice ought to do, during the said Term. And the said Master shall use the utmost of his Endeavor to teach or cause to be taught or instructed the said Apprentice in the Trade or Mystery of an Apothecary. And procure and provide for him sufficient Meat, Drink, washing Cloths and Lodging fitting for an Apprentice, during the said Term of five years and three months.

And for the true Performance of all and singular the Covenants and Agreements aforesaid, the said Parties bind themselves each unto the other, firmly by these Presents. IN WITNESS whereof, the said Parties have interchangeably set their Hands and Seals hereunto. Dated the first Day of June in the thirteenth year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George the third, King of Great-Britain, etc, Annoque Domini, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Seventy Three.

Signed and Delivered in the Presence of Jacob Ehrenzeller, Jacob Ehrenzeller Sr, Sam V. Coates

* * * *

|

| Jacob Ehrenzeller |

The Ex-residents Association of the Pennsylvania Hospital became active early in the Nineteenth century, and naturally concerned itself with just who was the first interne or resident of the hospital. It seemed probable that the first interne of the Pennsylvania Hospital would also be the first interne in America. When this indenture was discovered in the archives, Ehrenzeller became a likely candidate, although being apprenticed as an Apothecary did raise some questions. Nor did Ehrenzeller perform his indenture after the completion of medical school, as is now the custom; the first resident physician in that sense was Caspar Wister, in 1812. However, in colonial times most physicians did not go to medical school at all, qualifying as practitioners by working in the offices of practicing physicians, just as lawyers did for a much longer time. The argument is somewhat complicated by the existence of a medical school, the College of Philadelphia, created in 1765, and the fact that the upper crust of colonial medicine had gone to medical school in Edinburgh. That group of seven physicians with degrees gathered themselves together (in 1787) as the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, which still exists as the nation's oldest medical organization.

Dorothy I. Lansing MD, then the clerk of the Section on History of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, interested herself in these issues, and privately published a pamphlet about it. The argument for regarding Ehrenzeller as an interned physician revolves around the fact that his father had gone to medical school in Europe, and was regarded as a physician even though he made his living by operating a tavern after he came to Philadelphia. Furthermore, the 16 year-old Ehrenzeller found his apprenticeship disrupted by the Revolutionary War, particularly the occupation of Philadelphia in 1777 by British troops who used the hospital for their wounded. Nevertheless, young Ehrenzeller served as a surgeon at the battle of Monmouth (June 28, 1778). Among the minute books of the Board of Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital was discovered a minute of June 26, 1773 with the terms that Jacob Ehrenzeller, Jr. "shall have leave at his own or his Father's expense to attend the lectures of the Medical Professors out of the Hospital during the last two years of his apprenticeship; to attend the Surgical Operations and Lectures in the Hospital free of any expense; and that the Apothecary for the time being shall duly instruct him in Physic and Surgery." Dr. Lansing concluded that this was "a unique concurrent internship: apothecary apprentice cum medical student arrangement that no doubt suffered innumerable changes due to wartime problems; Jacob Ehrenzeller was awarded a certificate of medical competency. The College of Philadelphia medical school having ceased to exist because of the war, he obtained no degree in medicine."

Dr. Lansing found even stronger evidence of his physician rather than apothecary status in the fact that immediately after the war he established a practice in Goshen, Chester County. While it was customary for practicing physicians of the time to support themselves as schoolteachers, storekeepers or bankers, Ehrenzeller was able to live exclusively on his income as a physician. Indeed, after his death in July 18, 1838, his estate was one of wealth. It seems unlikely that an apothecary masquerading as a physician would have flourished in those competitive times, and on this basis it is concluded that he came as close as the times permitted to the description of an interned hospital physician. The Ex-residents Society of the Pennsylvania Hospital was satisfied enough to declare Ehrenzeller to have been its first interne. And invites the rest of the nation's medical community to examine whether anyone else might have been better qualified to have that title earlier.

The Richest Men in America

|

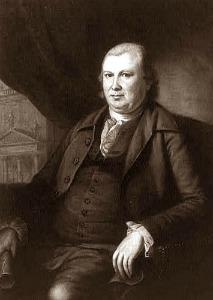

| Robert Morris |

Charles Peterson developed the idea but was unsuccessful in popularizing it, that Spruce Street in central Philadelphia could be regarded as an architectural museum. It stretches from river to river but has no bridge or ferry landing at either end, so traffic is less. The earliest house still standing near the Delaware River was built in 1702, with successive houses just a little younger, or at least less old, as you progress toward Broad (14th) Street whose houses were built around 1880. And then onward into the early Twentieth Century, crossing Broad Street and going westward toward the Schuylkill. For a century or more West Spruce Street was where eminent specialists had offices, much like Harley Street in London, which it somewhat resembles. The medical flowering of this area was promoted by the surgical advancements of the nearby Civil War, as well as the contributions of Andrew Carnegie to moving the College of Physicians from 13th street to 21st Street, attracted toward the 7000-bed Civil War hospital which turned into Philadelphia General Hospital in West Philadelphia. A number of these houses are just plain too big to be manageable as single family houses today, and Spruce Street West has lagged Society Hill and other Easterly sections in restoring its buildings. Perhaps in a few decades, that will happen, and perhaps in the meantime, the present relics will be preserved enough to revive someday the idea of a house design museum. Meanwhile, West Philadelphia around Spruce Street has obstructed progression by plonking the University of Pennsylvania, Drexel University and the Science Center as obstacles to residential housing development.

So let's take a simpler idea. For roughly a century, the then-richest men in America lived in one of several houses located within seven blocks of each other, easy walking distance for a tour. The first to attract notice as a self-made rich man was Robert Morris. Morris made his money in shipping, maybe even a little privateering, and then went into banking to keep his money at work. It is said that his personal fortune, adjusted for changes in the currency and economy, was once considerably larger than Bill Gates' would be today, adjusted for inflation. As most people know, Morris financed the American Revolution personally, went broke, ending up in debtor's prison. The first real mansion he lived in was opposite Independence Hall on Market Street, now celebrated as George Washington's while he was the first president. It was earlier the place where British Admiral Gates lived while he was in charge of the 1788 British occupation, and although it was also where Washington lived during most of his presidency, the house burned down in 1832. This house is not to be confused with either the house built for Washington at 9th and Market but never occupied by him or Morris's later mansions which he also never occupied because of financial difficulties. One house in the midst of Jeweler's Row was so ornate some think it contributed heavily to his later bankruptcy. A second Morris house still stands on Eighth Street at St. James Street, but it belonged to the Quaker Morris family, no relation. Other owners named Morris bought and occupied this place for a number of years, so its history is a little mixed up, presently as a fancy restaurant. A DuPont heiress once bought and fixed it up, but her husband commented no one could sleep in that house because a subway built underneath it badly rattled its timbers. Next door to the Quaker Morris house rises a fifty story apartment house, whereas a precaution against rattles, the first nine stories contain nothing but parking spaces. Since the apartment building is owned by Arabs, it is likely they are pretty rich but not necessarily richer than Bill Gates. Aside from the Market Street partial restoration, the main Robert Morris remnant is on Lemon Hill, northwardly opposite the Art Museum, whereas the main Quaker Morris house is in the Morris Arboretum in Chestnut Hill. There are sixty or so Morris's listed in the Social Directory, so keeping the two families distinct remains a difficulty in some circles.

|

| William Bingham |

On the Northeast corner of Third and Spruce Street, once lived William Bingham, a former partner of Morris and later himself the richest man in America. Although sadly the house burned down, it is displayed in one of the famous prints by William Birch in his notable Eighteenth Century collection , widely available in bookstores. The striking thing about Bingham was that he was only twenty-eight years old when he achieved richest-man status and built the house, patterned after one owned by a British Duke. He made his pile three times over. First, running a privateer operation in the Caribbean for his partner Robert Morris. On returning home, he bought up any worthless Continental currency he could stuff into barrels, and then either persuaded his friend Alexander Hamilton to redeem the currency at par or heard his plan to do so. And then, as if he didn't have enough money already, he invested enough gold bars to finance the Louisiana Purchase for Jefferson, since Napoleon wanted gold, please, no paper money. Among the various things he bought as an investment was the area in upstate New York, now called Binghamton. He lost a pile of money buying the land we now call the State of Maine since post-revolutionary Westward migration turned toward Ohio rather than into his Maine holdings once the British prohibition on colonizing past the Allegheny mountains was lifted. Bingham's sister-in-law wanted to become engaged to the heir of the Crown of France, who was living in temporary exile around the corner on Walnut Street. In a famous, possibly fictional, response, the Dauphin was told, No. If you do not become the King of France, you will be no match for her "The Golden Voyage". Quite a good read, and of particular interest to Philadelphia lawyers who learn Bingham died in 1804, but his estate was not settled until 1960. The lawyer who closed the case reported his partners were less than pleased to see it go.

|

| Stephen Girard |

Stephen Girard built several houses a few steps west of Bingham on Spruce Street, identifiable by having marble facing on their lower few feet; Charles Peterson lived in one of them as the first pioneer resident of the Society Hill revival. Girard made his money in the China trade, as a ship's factor. Like Morris, he recognized America's crying need for banking in a story too complicated to repeat here and moved the Girard Bank into the First Bank of America, now a museum (Peale portraits, architectural fragments) of the Park Service on Third Street. His wife was insane, and spent most of her life at the Pennsylvania Hospital at Eight and Spruce, and was eventually buried there. Girard left thirty million dollars to found the Girard College for "poor, white, orphan boys". His 1830 will withstood all legal attacks until the mid-Twentieth Century but was eventually broken. The school now has many black girls, is bankrupt, and the definition of orphan has expanded to include any child whose parents are separated. The definition of "poor" is several times greater than the national definition of the poverty level. In his will, Girard specified that the estate should purchase what is now Schuylkill County and hold it for a century. Shortly thereafter (or just possibly very shortly before that), coal was discovered in the region and Girard College became far richer. His correspondence includes many letters to Lafitte the Pirate, so more may be heard of them.

|

| Nichlos Biddle |

Nicholas Biddle had "old money", which he made in the traditional way of buying real estate, particularly in Ohio. He thus made a better guess than Bingham about the likely path of westward migration. But like Morris and Girard, he needed a bank to finance the real estate. Biddle also acted as the reserve bank for the myriads of currencies then issued by individual rural banks and charged a transaction fee to translate Kentucky money into something useful in Philadelphia or abroad. Martin Van Buren, who was the political manipulator behind Andrew Jackson and who became Andrew Jackson's eventual successor, stirred up trouble about this reserve role, and Jackson "broke" Biddle's bank by withdrawing federal deposits. Jackson's complaint was that holding federal "paper" eventually resulted in a government guarantee the bank could never fail, in an echo of the present accusation of some banks being "too big to fail". Ultimately, investment banking began to take its modern formwhen in 1838, the richest man, Anthony J. Drexel, moved over the Schuylkill River on Walnut Street, amidst what is now the University of Pennsylvania, but not far from Drexel University. He walked to work each day, however, at 4th and Chestnut Streets. Drexel was the first big banker to make his fortune in banking, and when he died it was said Philadelphia banking died with him. The earlier big bankers started out with money they had made in shipping or land speculation, but Drexel somehow saw that banking was a different way to get rich, deftly filling in the gap created by Andrew Jackson shuttering Nicholas Biddle's Second Bank. Part of the idea in Van Buren's mind was to shift the focus of American banking from Philadelphia's Chestnut Street to New York's Wall Street, and he was quickly quite successful. J.P. Morgan was invited by Drexel to start a Wall Street partnership with him in correspondence with his father, Junius Morgan, who ran an international bank in London. In the era just after the Civil War, there was a great deal of money in Europe anxious to be invested in the railroads and other booming American industries. The Morgans provided a vehicle for transferring such investment capital between continents, but the Morgans were viewed as having excessively sharp practices. As it happened, Junius Morgan had been trained in this transoceanic concept by George Peabody, a former Baltimore resident who had moved to London, then, the banking capital of the world.

George Peabody earlier had also been involved with Anthony J. Drexel, and Drexel was the more successful of the two international bankers. The whole issue with European investors was whether you could trust those wild and wooly Americans, and Drexel consistently demonstrated he was entitled to be called a straight arrow. As related by a good book by Dan Rottenberg Drexel decided he needed the vigor of the Morgans and invited them to join him in a New York-Philadelphia partnership. From that point forward, JP Morgan was the shining star of honesty and straight dealing, a lesson he evidently learned from Drexel. Indeed, he and his biographers repeatedly stress this feature of him -- "I will never do business with a man I don't trust". He didn't mention women, but his behavior seems to show he probably didn't include them in the concept. Drexel, on the other hand, led a quiet sober life in West Philadelphia, reading books, starting his university, and helping his niece, who was later made a Saint in the Catholic Church, start numerous charities. Although the Drexel children more or less drifted out of sight, Drexel's business successor Stotesbury led a wild and extravagant lifestyle that is the subject of many songs and stories. His wife, for example, never washed the sheets; she always had brand new ones put on the bed. Morgan, of course, spent lots of money in a conspicuous way. The term Metropolitan identifies most of his projects, The Metropolitan Art Museum, The Metropolitan Opera, The Metropolitan Club on Fifth Avenue, with membership originally limited to his partners. The name Corsair also was a trademark, the name of his yachts, and a firm statement about his approach to things. Another difference between the Morgans and the Drexels was similarly in the New York-Philadelphia character. When Jack Morgan, the son of JP, died in the 1930's he left an estate of "only" three million dollars. It would be hard to say what the Drexel fortune was worth at that time, but it is safe to say it would dwarf that, considerably. Most of the Drexel family moved to London, but among other things, financed the restoration of the Benjamin Franklin House on Craven Street, a hundred feet from Trafalgar Square. When the House of Drexel was much blamed for the 1987 stock market crash, legions of Drexel defenders rose to protect the family name. Cabrini College, Eastern University, Valley Forge Military College, St. David's golf course and much of Radnor are only pieces of the Drexel holdings, today.

The Scotch-Irish In the Revolution

|

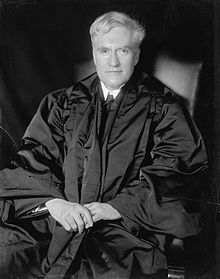

| Dr. Witherspoon |

The most eminent Scotsman in Colonial America was the Reverend Dr. Witherspoon, an eminent Presbyterian minister and President of the College of New Jersey, later Princeton University. Already at the top of the academic heap in Scotland, he was recruited for Princeton on the advice of Benjamin Franklin, who knew his political sentiments well. From England, Witherspoon made the following exhortation to his future compatriots at the critical moment of the Declaration of Independence:

|

| Scottish Pipers |

"To hesitate at this moment is to consent to our own slavery. The noble instrument on your table, which insures immortality to its author, should be subscribed this very morning by every pen in this house. He who will not respond to its accents and strain every nerve to carry into effect its provisions is unworthy the name of freeman. Whatever I may have of property or reputation is staked on the issue of this contest; and although these gray hairs must descend into the sepulcher, I would infinitely rather that they descend hither by the hand of the executioner than desert at this crisis the sacred cause of my country."

On the humbler level of popular doggerel, was the following:

"And when the days of trial came,

Of which we know the story,

No Erin son of Scotia's blood

Was ever found a Tory. "

It may not be quite true that the Scotch-Irish immigrants started the Revolution, or led it, or did most of the serious fighting. But in Pennsylvania their role was decisive. New England started most of the trouble, the aristocrats of Virginia quickly rose to the challenges of chivalry, but Pennsylvania was not so darned sure about this business. The back-country Germans were perfectly content to farm the richest topsoil they ever heard of, the Quakers were peaceful and prosperous just as they were. It was the Scotch-Irish of the frontier, needing no pretext of Tea Taxes or Stamp Acts to hate the English King, who were ready to take the musket off the wall at the slightest provocation.

It is indeed puzzling in retrospect to wonder what the English Kings were trying to achieve. Having driven the Scots out of their Scottish homeland into Ireland where they would be less bother, they subsequently drove them out of Ireland as well. The short explanation has been offered that James II who was to be driven off the throne for his Catholic leanings, had seen Ireland as a fall-back refuge in case of trouble and wanted it safely Catholic. So in anticipation of what did indeed happen under William and Mary, he wanted the Presbyterians out of there.

There is perhaps some logic to this, but try telling it to a Scot.

Tom Paine: Rabble-Rousing Quaker?

|

| Thomas Paine |

Thomas Paine (1737-1809) was born of Quaker parents, which makes him a "birthright" Quaker. Children born into Quaker families are accustomed to the subtleties of speech and behavior of that religious sect, ultimately growing up to be the main nucleus of tradition. Knowing what they are getting into, however, they are more likely to rebel against it than others who, coming to the religion by choice rather than by birthright, are commonly described as "Convinced Friends."

These stereotypes may or may not explain some of Tom Paine's paradoxes. He certainly was not a pacifist, a quietest, or a plain person. He was an important historical figure; Walter A. McDougall, the famous University of Pennsylvania historian, feels the American colonists might have sputtered and complained about Royal rule for decades, except for Paine. The American Revolution happened when it happened because Tom Paine stirred up a storm.

|

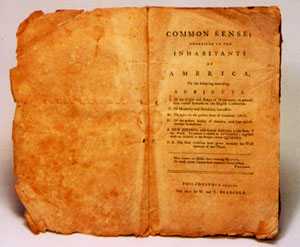

| Common Sense |

According to the traditional way of telling his story, Tom Paine was a ne'er do well failure in London. He ran into Benjamin Franklin, who advised him to emigrate to America in 1775, and within a year his pamphlet called ""Common Sense"" had sold 150,000 copies (some even claim 500,000), galvanizing the public and the Continental Congress into action on July 4, 1776. George Washington read Paine's writings to his troops on the eve of the Battle of Trenton. After that, Paine got mixed up with the French Revolution, and apparently became a severe alcoholic, proclaiming atheism all the way. Although Thomas Jefferson remained friendly to the end, Benjamin Franklin essentially told him to go leave him alone, and Washington would cross the street to avoid him. According to the usual line, Tom Paine was a big-mouthed rabble-rouser and a drunk, who traveled the world looking to stir up revolutions.

However, that cannot possibly be a fair recounting of the whole story. Thomas Alva Edison, whose opinion certainly counts for something, regarded Tom Paine as one of the greatest American inventors, creating the first steel bridge, the first hollow candle, and the principle of central drought in heating. Paine early became a close friend of the Hicks family, the central figures in modern Quakerism; it seems a little unclear how much Tom Paine was reflecting the views of Elias Hicks, and how much Hick site Quakerism can be said to have originated in the thinking of Thomas Paine. Paine was very far from being an atheist. In fact, both he and Hicks believed so fervently in the universality of God that both of them scorned the rituals, paraphernalia, and transparent superstitions of -- religion.

Furthermore, Paine was able to reach the rationalists of The Enlightenment with arguments which cut to the heart of Royalist loyalties. America was too big and too remote to be ruled by a king, particularly one who abused his privileges behind a claim of divine right. William the Conqueror, for example, never denied he was a usurper. One way or another, every king must earn his throne. So, as for feudalism and hereditary aristocracy, what was King George doing with all those German mercenaries? After two centuries of democracy, most Americans are too far from feudalism to appreciate the legitimacy of military meritocracy. Whatever King George was up to, he didn't stand for empowerment of the best and the brightest Englishmen, who in fact might well be opposed to him. If you wanted to get to Virginia aristocrats, Boston sea captains, and Kentucky backwoodsmen, that was exactly the line to take in Common Sense.

Unfortunately, Citizen Tom Paine was a freethinker and couldn't be quiet about it in his later books. He didn't like the way the Old Testament Hebrews hungered for a king. He didn't like the way the New Testament sprinkled miracles on top of unassailable moral principles, and he particularly didn't like the claim that God got an unmarried girl pregnant. He antagonized almost every established religion by proclaiming that no one should make a living from religion. He wrote a book called Age of Reason proclaiming all these freethinking ideas, which struck Ben Franklin as such a stupid thing to do that he would not discuss it, beyond saying that even if he should succeed in convincing people to abandon religion, just imagine how much worse they would probably behave without it. George Washington, who hadn't a trace of intellectualism about him, more accurately portrayed the typical American revulsion at anyone who was so unprincipled as to say such unorthodox things in public. Jefferson distanced himself for political reasons rather than intellectual ones. Franklin thought Paine was a fool. Washington and the rest of the country thought he was a viper.

It would have to be conceded -- by anyone -- that Tom Paine was self-destructive, even sassing Robespierre while in a French prison. How is it such a loose cannon could get the American public off dead center and make the Continental Congress grasp the nettle of revolution, in less than a year? Let's go back to how he came to America in the first place. Franklin sent him.

Then he promptly got a job as editor of the Pennsylvania Gazette, which Franklin had owned for thirty years. And then, in an era when the largest city in America had a population of twenty-five thousand, and the printing presses of the day were able to turn out three or four pages a minute, he sold 150,000 copies of the fifty-page "Common Sense." Who but Franklin, in private partnerships with sixty printers, could have possibly authorized, financed, and printed 150,000 copies of a colonial pamphlet? In order to find that much printing capacity in colonial America, a great deal of other printing had to lose its place in the queue.

Even today, a best-seller is defined as a book that sells 50,000 copies, and it generally takes three years to get it done. In the Eighteenth Century, for an unknown alcoholic to get off the boat and find a publisher for a best seller in a few weeks is hard even to imagine. Unless he had important help.

Poor Richard Plays Hardball

Several distinguished biographies of Benjamin Franklin have recently skirted his January 1774 confrontation with the British government in the "Cockpit" of Whitehall. Presumably, the exquisite details are too fancy and complicated for easy description, or possibly the cardinal significance of this intellectual duel is underestimated. It seems possible the American Revolution was declared by one man's making up his mind. A mind made up in one particular hour in one particular room, irrevocably, in front of the whole British Establishment.

The Archbishop of Canterbury was there, and so were Edmund Burke and Joseph Priestley. So were all the Privy Council, and most of British high society, giggling and hissing at his discomfort. Poor Richard stood there silent and impassive. The Enlightenment thought they were deciding his fate, but he was deciding theirs.

|

| Lord Alexander Wedderburn |

Franklin had published some letters he had promised not to publish, but they showed the British government in a very bad light. Alexander Wedderburn the Solicitor-General had deliberately orchestrated the meeting to shift the emphasis to Franklin's broken promise and away from British provocation of it. The room had been packed with highbrows promised a delicious treat, and Wedderburn's speech was meticulously planned as an entertainment for the intelligentsia. The man who discovered electricity was mocked as "conducting" the letters. And a famous man of letters was reminded that the ancient Athenians would brand three letters on the back of the hand of a thief: FUR, the name for a thief, an elaborate 18th Century pun making reference to fur hats and collars, which were the traditional symbol of printers. Wedderburn roused himself to the climactic announcement that the famous Roman, Plautus, had invented the famous derivative epithet, "Homo, triumph literarum," portentously meaning a three-letter man. The galleries of Whitehall tittered and applauded this thrilling attack. Franklin continued to stand, his face perfectly inscrutable to the end.

|

| Deplessis Portrait of Benjamin Franklin |

In his report back to the Massachusetts Legislature, Franklin used dismissive understatement to show he had not been asleep while he was impassive. He had been, he said, "the butt of his invective ribaldry for nearly an hour." After that, Poor Richard seemed to disappear from British society for nine months, seeing only close friends in his house, and then he sailed home to America, becoming a member of the Continental Congress the day he stepped off the boat. Meanwhile, he had arranged to have his portrait painted by Duplessis, the most distinguished painter in France, eventually to have it hang next to a painting by the same artist, of the King of France. To the original sketch for the portrait had been added a fur collar, the traditional emblem of the painter's guild. At the bottom, where a motto ordinarily would be found, was the single, three-letter Latin word, "VIR," or man, which would today be equivalent to he-man. And just so everyone would get the point, Franklin sent an otherwise anonymous letter to the newspapers, signed "Homo Triumph Literarum" in which he taunted that the friends of Mr. Franklin would have to agree he was a thief, as in the famous line of poetry that "He stole the lightning from the skies." But old Ben wasn't just bragging. Anticipating the baseball player Dizzy Dean by two hundred years, he was in effect saying "It ain't braggin' if you really have done it."

On Feb. 6, 1778 he and Silas Deane went over to the French palace to sign the Treaty of Alliance with the King of France. Instead of his usual brown suit, Franklin was wearing a faded blue one, and Deane questioned why he wore old clothes to such an important ceremony. "To give it a little revenge," was the answer. "I wore this suit on the day Wedderburn abused me at Whitehall." The true depth of Franklin's feelings would never have been known if Deane had not asked.

As a reminder, the Treaty they were signing said, "The essential and direct end of the present defensive alliance is to maintain effectually the liberty, sovereignty, and independence of the said United States. . . ." All in all, not a bad academic performance for a man who never went past the second grade in school.

REFERENCES

| The Invention of Air: A Story of Science, Faith, Revolution,and The Birth of America, Steven Johnson ISBN: 978-1-59448-852-8 | Amazon |

B. Franklin, Scientist

|

| Franklin Institute |

FROM time to time, the Franklin Institute has a display of its own and other museums' collections of the scientific instruments of Benjamin Franklin. It's well worth anybody's visit when it is available because the beauty and craftsmanship of these instruments alone make them remarkable works of art. Franklin was financially able to retire at the age of 42, and it tells you something of the 18th-century culture that Franklin took up scientific experiments in order to be like other independently wealthy gentlemen. Science, or natural philosophy, this seems to have been in a class with getting a coat of arms and having his portrait painted, all of which cheapens our view of Franklin as a scientist.

|

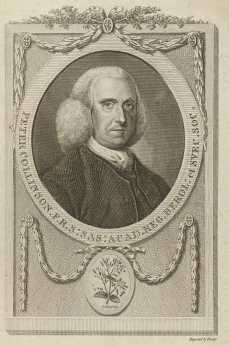

| Peter Collinson, F.R.S. |

In fact, Franklin was conducting an active correspondence with other scientists interested in electricity for many years, in particular, one Peter Collinson, F.R.S. in London. Collinson collected thirteen of Franklin's letters about his experiments, the earliest dated 1747, and printed them in 1751 as an 86-page book called Experiments and Observations about Electricity . By 1769, several more letters expanded the book to 150 pages, almost all of them describing reproducible experiments in great detail. The kite and key episode are described, but soberly and sparingly. Without making the point too graphically, an appendix was added describing how lightning had been used to kill some turkeys, so a somewhat increased power would probably be enough to kill a person. Franklin recognized that something was moving from here to there, that it had positive and negative charges, and that it was possible to store it up in a storage battery. He recognized the difference between substances that would conduct electricity and other substances that would act as insulators. Later on, he would discover that the torpedo fish stores and transmits electricity, suggesting that somehow animals made and used electricity as part of life. And of course, he put the discoveries to practical use as lightning rods, which he refused to patent.

|

| Madame Helvetius |

By the time he went to England and France as a negotiator, his wide acquaintanceship in the scientific world was happy to introduce him to other famous people, like kings, Voltaire, Mozart, and Madame Helvetius the wife of the Swiss philosopher, the only woman to whom he is known to have made a proposal of marriage. When someone mentioned standing before a king, he replied he had stood before five of them. King Louis XVI, for example, appointed Franklin to a four-man committee to investigate hypnotism, then being touted as "animal magnetism" by Franz Mesmer. The other three committee members were unfortunately also destined to become acquainted with the guillotine: Brother Joseph-Ignace Guillotin himself, and two future victims of the invention, Antoine Lavoisier the discoverer of oxygen, and Jean Sylvain Bailly who first calculated the course of Halley's Comet, not to mention Louis XVI himself. It is not easy to think of any other scientist who was able to mix his scientific fame with changing international history, acquiring in the process the sobriquet of the founder of the American diplomatic corps. But then, he was witty as well as smart, and his career is a warning to those who now hope to devote their whole lives to being admitted to a prestige college and then coasting on its reputation. Franklin, it should be remembered, dropped out of school after the second grade.

Franklin Declares Independence a Year Early

Joseph Priestly became a close friend of Benjamin Franklin almost as soon as they met. Priestly was an Anglican clergyman who broke loose and formed the Unitarian Church, and meanwhile, his scientific discoveries also entitle him to be called the Father of Chemistry. Franklin, of course, was the discoverer of electricity; it would be hard to be sure which of the two was more brilliant. In July, 1775, Franklin wrote the following letter to Priestly, which makes a trenchant case that the American colonies should, and would, break away from England. Since some legal authorities, following Lincoln's lead, maintain that Jefferson's manifesto "informs" the United States Constitution, it might be well to begin referring to this letter as an even clearer statement of the mindset of America's founding leaders.