4 Volumes

Colonial Times

More than half of American history took place before 1776, but after 1492. For Philadelphia, Colonial history lasted about a century.

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Surviving Strands of Quakerism

Of the original thirteen, there were three Quaker colonies, all founded by William Penn: New Jersey first, Pennsylvania biggest, and Delaware so small Quakerism was overcome by indigenous Dutch and Swedes.

The Proprietorship of West Jersey

The southern half of New Jersey was William Penn's first venture in real estate. It undoubtedly gave him bigger ideas.

Defining and Naming New Jersey

|

| King Charles II |

On March 12, 1664, King Charles II of England granted his brother, James, Duke of York, all of the lands in the New World known as the Dutch Domain or New Netherland. The gift included land from the

... West side of the Connecticut River to the East side of Delaware Bay...

Three months later, James carved New Caesarea from that land for John, Lord Berkeley, and Sir George Carteret. This lease sealed the grant to

all that Tract of land adjacent to New England, lying and being to the Westward of Long Island and Maniatis Islands, and bounded on the East Part by the Main Sea and part by Hudson's River, and hath upon the West Delaware Bay or River extendeth Southward to the Maine Ocean as far as Cape May at the mouth of Delaware Bay. Which said Tract of land is hereafter to be called by the name or names of New Caesarea or New Jersey...

---From documents at the headquarters of the West Jersey Proprietors, Burlington, New Jersey.

Jersey

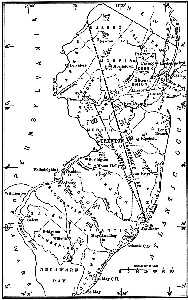

|

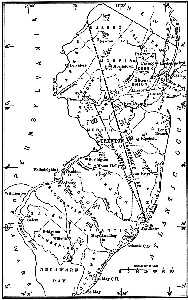

| Map of New Jersey |

Once you notice the oddity of salt water in the lower reaches of the Delaware and Hudson rivers, it gets easier to understand the current theory that southern New Jersey was once an island. Like Long Island, it was separated from the mainland by a sound, but in the Jersey case the sound silted up from Trenton to New Brunswick, creating a new peninsula of "West" Jersey by uniting the island with the mainland. The colony was named after the island of Jersey off the coast of England, a gesture for Sir George Carteret, who was given the American area out of gratitude for once sheltering the exiled royal brothers Charles II and James from Cromwell, in that other Jersey. Cape May was probably a second distinct island later joined to the larger one by the transformation of the silted ocean into the bogs of the Maurice River. Cape May started as a whaling community, populated by Quakers from New York and New England, who always maintained a social distance from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting. The long Atlantic beaches of New Jersey now repeat the main geological process, with successive generations of barrier islands first heaved up by the ocean and then packed against the mainland, filling up the brackish bay. The cycle of forming and packing successive barrier islands takes about three hundred years before a new one starts. In a larger sense, the process consists of the former mountains of Pennsylvania crumbling into the ocean and then responding to wave action.

It's no mystery, therefore, why southern New Jersey is flat, broken up by turgid meandering streams which casually empty in either direction. The head of Timber Creek, which flows into Delaware, is only eight miles from the head of the Mullica River, flowing toward the ocean. During the Revolutionary War, the British found it too dangerous to sail up these winding creeks, since at any moment they might make a sharp turn and be facing a battery of cannon on the shore. An arrangement quickly grew up that buccaneers would build ships in the center of heavy oak forests and sail them out to Barnegat Bay, thence out one of the inlets of the barrier islands into the blue water. The financiers of Philadelphia, many of them with names now in the Social Register, would come from the rear, sailing up the Delaware River creeks, and walking the last mile or two to privateer headquarters on the Atlantic-flowing creeks. Auctions were conducted, in which the ships were examined, the captain interviewed, and the crew observed in target practice. If you bought a small share you would be rich when the ship returned; and if it never returned, well, you had to invest in a different one. New Jersey is indignant of the opinion that these privateers were mainly responsible for winning the Revolution, but given little credit for it. Many more British sailors were lost to the privateers than soldiers were lost to Washington's troops and the economic loss to Great Britain of the ships and cargoes eventually became serious. Since much of the profit from privateering was recycled into the American war effort by Robert Morris, the British found themselves facing an enemy much more formidable than just the ragged frozen troops at Valley Forge on the Schuylkill. Meanwhile, William Bingham was conducting a similar privateering operation in partnership with Morris but based on the island of Martinique, but that's another story.

In later centuries, the traditions and geography of the Jersey Pine Barrens suited themselves to smuggling and bootlegging during the era of alcohol Prohibition, and even after Repeal, high taxes on liquor kept bootlegging profitable. As late as the 1950s, there were divisions of FBI men prowling the woods of South Jersey, on the lookout for trucks carrying bags of cane sugar, or coils of copper tubing. After housing developments started to invade the forests, the hardball politics of South Jersey reflected a Mafia culture thought more characteristic of South Philadelphia. Near Vineland and Atlantic City, it isn't just a culture, it has the accent, because it also has some of the ancestry.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey, A Historical Account of Place names in the United States: Richard P. McCormick: ISBN-13: 978-0813506623 | Amazon |

Lansdowne

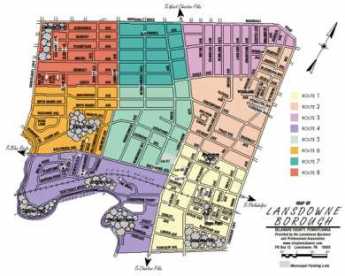

|

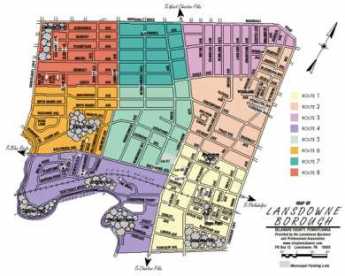

| Lansdowne Map |

The Granville, or Lansdowne, the family had so many members important in English history, that the Lansdowne name adorns countless schools, boroughs, colleges, museums and other monuments around the former British empire. It would require undue effort to sort out just why each memorial is named after just which member of the family. In the Philadelphia region, Lansdowne is the name of a small borough in Delaware County,

|

| Lansdale |

often annoyingly confused with Lansdale, a small borough in Montgomery County. However, it really seems more appropriate to focus reverence on the Lansdowne mansion, which from 1773 to 1795 was the home in now Fairmount Park of the last colonial Governor. That would have been John Penn, who was one of several Penns who still shared the Proprietorship until 1789, and who shared in the miserly payment which the Legislature of the new Commonwealth made as compensation for expropriating twenty-five million acres of their property. The French Revolution was going on at that time, so there were probably some patriots who would scoff that John Penn was lucky not to be guillotined.

The Penn family could see the Revolution coming, and like everyone else was uncertain who would win. Real decision-making for the Proprietorship rested with Thomas Penn in London, a close friend of the King and his ministers. The strategy employed in this difficult situation was to surrender the right to govern the colony conferred by its original charter and to become mere real estate owners with John their local representative pledging local allegiance. That might have worked for a while, until General Howe's troops captured Philadelphia. Soldiers were dispatched to Lansdowne to tell John Penn he was under detention, to reduce his potential utility to the occupying army.

|

| Horticultural Hall |

As matters eventually worked out, some of the Penn descendants remained fairly wealthy after the Revolution, especially those whose wives had inherited substantial assets from other sources. But some were severely impoverished. The stately Georgian mansion burned down in 1854, and the site was then occupied by the Horticultural Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Perhaps because of misplaced patriotic fervor, it is now difficult to find a picture of Lansdowne.

The elegance of the place, on 140 acres, is suggested by the fact that William Bingham the richest man in America at the time, apparently acquired it from James Greenleaf the partner of Robert Morris, and the nephew by marriage of John Penn, who acquired it from Penn's estate but probably had to give it up in the financial disasters of Morris and his firm. Lansdowne was still a grand manner when it was briefly acquired by Joseph Bonaparte, the former King of Spain. In view of the fact that Bingham had provided President Jefferson with the gold to finance the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte, and earlier had practically forced the Congress to call off an impending war with France, there was likely a connection here.

And to some extent, the ill-treatment which John Penn received from the Pennsylvania legislature (roughly fifteen cents an acre) in the Divestment Act of 1779 can possibly be traced to the unrelenting hatred by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania's icon. History does not tell us what made these two former friends fall out in 1754, sufficient to make Franklin willing to spend years in London trying to get the colony away from the Penns. The feeling was surely mutual. When John Penn was offered the patronship of the American Philosophical Society, he declined, just because Franklin was its president. In retrospect, that sounds unwise.

The Heirs of William Penn

|

| William Penn |

Freedom of religion includes the right to join some other religion than the one your father founded; William Penn's descendants had every right to become members of the Anglican church. It may even have been a wise move for them, in view of their need to maintain good relations with the British Monarch. But religious conversion cost the Penn family the automatic political allegiance of the Quakers dominating their colony. Not much has come down to us showing the Pennsylvania Quakers bitterly resenting their desertion, but it would be remarkable if at least some ardent Quakers did not feel that way. It certainly confuses history students, when they read that the Quakers of Pennsylvania were often rebellious about the rule of the Penn family.

|

| Delaware |

Such resentments probably accelerated but do not completely explain the growing restlessness between the tenants and the landlords. The terms of the Charter gave the Penns ownership of the land from the Delaware River to five degrees west of the river -- providing they could maintain order there. King Charles was happy to be freed of the expense of policing this wilderness, and to be paid for it, to be freed of obligation to Admiral Penn who greatly assisted his return to the throne, and to have a place to be rid of a large number of English Dissenters. The Penns were, in effect, vassal kings of a subkingdom larger than England itself. However, they behaved in what would now be considered an entirely businesslike arrangement. They bought their land, fair and square, purchased it a second or even third time from the local Indians, and refused to permit settlement until the Indians were satisfied. They skillfully negotiated border disputes with their neighbors without resorting to armed force, while employing great skill in the English Court on behalf of the settlers on their land. They provided benign oversight of the influx of huge numbers of settlers from various regions and nations, wisely and shrewdly managing a host of petty problems with the demonstration that peace led to prosperity, and that reasonableness could cope with ignorance and violence. When revolution changed the government and all the rules, they coped with the difficulties as well as anyone in history had done, and better than most. In retrospect, most of the violent criticism they engendered at the time, seems pretty unfair.

|

| John Penn |

They wanted to sell off their land as fast as they could at a fair price. They did not seek power, and in fact surrendered the right to govern the colony to the purchasers of the first five million acres, in return for being allowed to become private citizens selling off the remaining twenty-five million. Ultimately in 1789, they were forced to accept the sacrifice price of fifteen cents an acre. Aside from a few serious mistakes at the Council of Albany by a rather young John Penn, they treated the settlers honorably and did not deserve the treatment or the epithets they received in return. The main accusation made against them was that they were only interested in selling their land. Their main defense was they were only interested in selling their land.

As time has passed, their reputation has repaired itself, and they bask in the universal gratitude which is directed to their grandfather and father, William Penn. Statues and nameplates abound. Nobody who attacked them at the time appears to have been really serious about it, except one. Except for Benjamin Franklin, who turned from being their close friend to being their bitter enemy. Franklin tried to destroy the Penns, traveled to England to do it, and after twenty years seemed just as bitter as ever. Something really bad happened between them in 1754, and neither the Penns nor Franklin has been open about what it was.

Unexpected Benefits of a Lurid Past

|

| Map of Barnegat Bay |

Centuries came and centuries went, while a Quaker shipyard went on about its business along the shore of Barnegat Bay. Next door there was a notable roadhouse after the second World War, rumored to have formerly been a secret speakeasy during the days of Prohibition. In time, the only occupant of the roadhouse was a wealthy widow, who mostly minded her own business and grew to be an affable neighbor to the Quakers next door. As rowdy days of Prohibition faded into the background of decades past, the old lady felt free to recall some of the less tawdry features of her past, to the Quakers who in turn felt free to chuckle about them. Ancient history, perhaps a little varnished and polished up. It was, however, a little disquieting to hear her say that the liquor for the speakeasy was often supplied by sailors from the Coast Guard, who routinely diverted 20% of the cargo of rum Runners they had captured, into commercial channels. Exciting times, those were.

|

| The Coast Guard out looking for Rum Runners |

One day when the widow was ninety-six years old, the lights of her house stayed on, without other signs of activity. The neighbor eventually walked over to the back door and looked through the window, where it could be seen that the old lady was lying on the floor, rather motionless. He might have called the police, or broken into the house, but there was another option.

He went down to the basement, entering a rather dusty but quite elaborate barroom. Following old directions, he walked to a closet and climbed up a stepladder leading into another closet on the floor above. Stepping out, he found the lady was still breathing, called her relatives, and watched her be taken off to a nursing home to end her days. No one seemed to ask very many questions.

New Jersey: A Keg Tapped at Both Ends (2)

The New Jersey legislature first fought for Independence, then about debts, then railroads and corporations, and now -- about debt, again.

|

The New Jersey legislature ratified the Declaration of Independence in the Indian King Tavern of Haddonfield, then moved to Princeton and ever since has been in Trenton. The Statehouse in Trenton is the second oldest in the nation, after the one in Annapolis, although it has grown like a snail with the original building nestled inside many additions. In one sense it is totally unique; it's the only state capitol in the nation where you can look out a window and see another state. It's right on the water's edge of Delaware, a hundred yards from those Hessian barracks that Washington surprised in 1777.

|

| Rivals, North and South |

In its early years the legislature concerned itself with raising troops during the Revolution. After that, it spent a great deal of time settling debts to pay for the Revolution. From that arose the traditional rivalry, even hostility, between the northern and southern halves of the state. To some degree, this reflects the two original provinces of East Jersey (Scottish Quakers) and West Jersey (English Quakers), but the Quaker character persisted much longer in West Jersey. The northern half, with many Dutch settlers spilling over from New York and Congregationalists from Connecticut, evolved into mainly a population of debtors; debtors enjoy inflation because it cheapens the cost of their repayments. The southern half of New Jersey, persistently Quaker in the settlement, was where creditors lived; creditors want to recover the value of the money they risked, so they hate inflation. The Mason Dixon line, extended, would cross southern New Jersey. However, it was the northern half of the state which favored the Confederacy during the Civil War, whereas the Quakers in the south were strongly opposed to slavery. Later on, irritation over permitting Atlantic City gambling was one of the various issues which eventually prompted South Jersey to try to secede from the northern spendthrifts; the secession proposition was actually on the ballot in the late Twentieth Century. Up until 1966 the Republicans always dominated the Senate, but that was because each of the 21 counties had one senator, and you can't gerrymander county lines. Then, it was deviously proposed that the state should be re-divided into 40 numerically equal Senatorial districts (i.e. instead of counties); the Senate has had a Democratic senatorial majority more or less ever since, in spite of numerous Republican majorities in state-wide elections. The legislative districts in the Assembly are reapportioned every ten years to respond to the new census; it is close to the facts that the subsequent gerrymandering of that decennial reapportionment effectively forecloses the politics (and predicts the agenda outcome) within the Assembly for each subsequent decade. In recent years, state Congressional delegations have all become increasingly polarized as a result of partisan gerrymandering. New Jersey leads the way in this unfortunate process: the Assembly and the Congressional delegation are polarized in what has become a national pattern, but in addition, its state Senate is permanently gerrymandered by substituting "districts" for "counties", and redrawing the boundaries in the state constitution.

|

| The Amboy and Camden Railroad |

Over time, the early legislature devoted most of its time to chartering corporations, because there were no universal corporation laws and each new corporation required a separate legislative charter. During the early Industrial Revolution, a great many new businesses sought the authority to limit investor liability. Each corporation had its own enabling act and hence its own deal, its own set of rules and conditions open to limiting amendments by competitors or favorable restatement at the urging of lobbyists. Along came the first railway in America, Stevens's conception of the Amboy and Camden Railroad. The New Jersey legislature, no doubt persuaded by private inducements, not only gave the Amboy and Camden permission to use eminent domain to acquire its right of way, but also conferred a perpetual tax exemption, and perpetual railroad monopoly. For the next fifty years, the legislature then concerned itself with hardly anything except railroad matters. As Willie Sutton said about banks, that was where the money was.

Perpetual is a pretty unambiguous adjective, of course, and it might be an interesting topic in judicial gymnastics to observe how the state would get itself out of the impossible economic straight-jacket of conferring a perpetual monopoly on only one railroad. It proved achievable, however, when the proprietors of a new Stanhope Railroad slipped exemptions and enabling legislation for itself into one of the thousands of corporation bills which flooded through the legislature, unread by anyone except the authors. After the Governor who also hadn't read the bill, signed this sleeper into law, the uproar was predictably loud and accusatory. In a sense, the wrangle about New Jersey railroads was not finally settled by the legislature at all but by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which crossed Delaware at Trenton, and went south to Philadelphia along the Pennsylvania side of the river. New Jersey had not only lost the advantage of railroad competition, but it had also essentially lost all of the main North-South railroad traffic made possible by improved bridge construction methods. Almost all rail traffic was East-West, and the Pennsylvania RR soon captured national dominance. Among other things, railroads thus avoided the expensive hidden costs of going before the New Jersey Legislature. New Jersey preferred to seek a new constitution with a new organization of matters, but one thing about New Jersey never seems to change. Between eleven and twelve thousand bills are still introduced every year. Overloading the attention of the legislators creates the main opportunity for corrupt politics in all legislatures, and is the central strategy for its concealment. It's even worse than New Jersey actually passes about 300 laws a year by sitting for a hundred hours in plenary session: the legislature sits for 30 or 40 three-hour sessions in the afternoon each year, usually Monday and Thursday, from November to May. We try to be a nation of laws and not of men, but it would be hard to praise the application of that truism in New Jersey, where quite obviously the Governor does most of the governing, and deciding, and dispensing. Recent Governors have evidently preferred to borrow money rather than pay any attention to balancing a budget, since New Jersey has gone during fifty years from having no income or sales tax to having the highest of them both, and the highest property taxes, plus $50 billion in debt. Let's repeat the central point: the thing which will matter for a decade is how the legislature gerrymanders the voting districts after the 2010 census. The second source of corruption is the severe limitation of individual political contributions, combined with a lack of limits of donations to the County political machine; the machine totally dominates all New Jersey nominations, and by gerrymandering can ignore the general elections. The public has discovered that this process leads to the second-highest state tax rate in the nation, and wealthy people are fleeing to other states in noticeable numbers. Since wealthy people pay a disproportionate share of taxes, the disappearance of this tax source throws a major tax burden onto those with lower incomes. As this process spirals out of control, something about it must change.

Burlington County, NJ

|

| Burlington County Map |

Burlington County used to be called Bridlington. It contains Burlington City, formerly the capital of West Jersey, which is how they styled the southern half of the colony, the part controlled by William Penn. In colonial times, the developed part of New Jersey was a strip along the Raritan River extending from Perth Amboy, the capital of East Jersey, to Burlington. To the north of the fertile Raritan strip, extended the hills and wilderness mountains; to the south extended the Pine Barrens loamy wilderness. The Raritan strip was predominantly Tory in sentiment, while the remaining 90% of the colony consisted of backwoods Dutch farmers to the north, and hard-scrabble "Pineys" to the south, except for the developments farmed by Quakers. The Quakers had ambiguous sentiments during the Revolution, leaving conflicts between pacifism and self-defense to individual discretion. The real fighting mostly went on between the Episcopalian Tories and the Scottish-Presbyterian rebels, both of which were sort of newcomer nuisances in the minds of the Quakers. The warfare was bitter, with the Tories determined to hang the rebels, and the rebels determined to evict or inflict genocide on the loyalists. Standing aside from such blood-letting of course inevitably led to a loss of Quaker political leadership. When East and West Jersey were consolidated by Queen Anne into New Jersey in 1702, the main reason was ungovernability, with animosities which endure to the present time in the submerged form. Benjamin Franklin's son William was appointed Governor through his father's nepotism, but when he turned into a rebel-hanging Tory, his father extended his bitterness about it into a hatred of all Tories. The later effect of this was felt at the Treaty of Paris, where Ben Franklin would not hear of leniency for loyalists, striking out any hint of reparations for their property losses. In a peculiar way, the factionalism resurfaced at the time of the Civil War, where the slave-owning Dutch in the North came into conflict with the slave-hating Quakers in the South. The problem would have been much worse if the Jersey slaveholders had been contiguous with the Confederacy, but it was still bad enough to perpetuate local sectionalism. A few decades ago, it was actually on the ballot that Southern Jersey wanted permission to secede.

Under the circumstances, when James K. Wujcik wanted to work for progress in his native area, he avoided any ambition to enter State politics and concentrated his efforts on Burlington County. He is now a member of the Board of Chosen Freeholders of Burlington County, along with four other vigorous local citizens. Most notable among them is William Haines, the largest landholder by far in the area, whose family still controls the shares of the Quaker Proprietorship. Membership on the Burlington County Board of Freeholders is a part-time job, so Mr. Wujcik is also president of the Sovereign Bank. We are indebted to him for a fine talk to the Right Angle Club avoiding, with evident discomfort, many mentions of state politics or sociology.

|

| Congressman Saxton |

Burlington is the only New Jersey county which stretches from the Delaware River to the Atlantic Ocean, including the Pine Barrens occupying 80% of the land mass in the center; fishing and resorts dominate near the ocean and former industrial areas along the river. Much of the area has been converted to agriculture for the Garden State, but about 10% is included in a National Preserve. The population has doubled in the past fifty years, so urbanization is replacing agriculture, which had earlier displaced wilderness. The county includes Fort Dix and Maguire Air Force Base, strenuously promoted for decades by now-retired Congressman James Saxton.

Somewhere in the past few decades, Burlington became quite activist. Although many tend to think of real estate planning as urban planning, this largely rural county went in for planning in a big way, deciding what it was and what it wanted to be. Generally speaking, its decision was to replace urban sprawl with cluster promotion. The farmers didn't like an invasion by McMansions or industries, while the towns lost their vigor through tax avoidance behavior of the commuter residents. Overall, the decision was to push urban development along the river in clusters surrounding the declining river towns, while pushing exurban development closer to logical commuting centers, leaving the open spaces to farmers. Incentives were preferred to compulsion, with a determination never to use eminent domain except for matters of public safety. To implement these goals, two referenda were passed with 70% majorities to create special taxes for a development fund, which bought the development rights from the farmers and -- with political magic -- re-clustered them around the river towns. The farmers loved it, the environmentalists loved it, and the towns began to revive. The success of this effort rested on the realization that exurbanites and farmers didn't really want to live near each other, and only did so because developers were looking for cheap land. Many other rural counties near cities -- Chester and Bucks Counties in Pennsylvania, for example -- need to learn this lesson about how to stop local political warfare. Corporation executives don't want to live next to pig farms, but pig farmers are quite right that they were living there, first. When this friction seeps into the local school system, class warfare can get pretty ugly.

|

| Burlington Bristol Bridge |

In Burlington County, they thought big. The central project was to push through the legislature a billion-dollar project to restore the Riverline light rail to the river towns, along the tracks of the once pre-eminent Camden and Amboy Rail Road. It was an unexpected success. During the first six months of operation, ridership achieved a level twice as large as was projected as a ten-year goal. Along this strip of the Route 206 corridor, the old Roebling Steel Works are becoming the Roebling Superfund Site, now trying to attract industrial developers. The Haines Industrial Site originally envisioned as a food distribution center was sold to private developers who have created 5000 jobs in the area. Commerce Park beside the Burlington Bristol Bridge is coming along, as are the Shoppes of Riverton and Old York Village in Chesterfield Township. As Waste Management cleans up the site of the old Morrisville Steel plant across the Delaware River, a moderate-sized development project is becoming an interstate regional one.

No doubt there will be bumps in these roads; the decline of real estate prices nationally is a threat on the horizon, because it provokes a flight of mortgage credit. It works the other way, too, as banks decide to deleverage by reducing outstanding loans; this is the way downward spirals reinforce themselves. And anyone who knows anything about all state legislatures will be skeptical about political cooperation in a state as tumultuous as New Jersey. The Pennsylvania Railroad destroyed the promise of this state once; some other local interest could do it again. Nevertheless, right now Burlington County looks like a real winner, primarily because of effective leadership.

Line Dividing East from West Jersey

|

| William Penn |

At this point William Penn entered the picture as one of three Quaker trustees for Byllinge, who had gambling debts. A tenth of this share was given to John Fenwick, the 1675 settler of Salem, to settle his part of the disputes with Byllinge; the rest of it constituted what was to become the oldest American stockholder corporation, The Proprietors of West Jersey. The arrangement up to this point was firmly settled for the southern half of New Jersey by a Quintipartite Deed of July 12, 1676, , signed by the three Quaker trustees plus Byllinge and Fenwick. Aside from establishing the Proprietorship, the main point of this deed was the separation of West Jersey from East Jersey (the Carteret part) by a North-South line which still persists as the upper border of Burlington County. The right to govern this land was fully restored in 1680 by a Confirmatory Grant from James, probably after considerable lobbying in London by William Penn.

Presumably in pursuit of this final confirmation, Penn had negotiated a hundred-page agreement with prospective settlers which outlined his plans for governing, called the Concessions and Agreements of March 14, 1677, . Although its original purpose was mainly a real estate marketing tool, this landmark document seems not only to have persuaded the Duke of York but so shaped the thinking of the English colonies that many of its features are readily recognized in the American Constitution of 1787.

|

| The line dividing West and East NJ |

The land mass between the North and South Rivers (Hudson and Delaware) only came completely and legally into the hands of Quakers in 1681. At that time Carteret's widow, Lady Elizabeth, sold the northern half (East Jersey) to twelve Quaker proprietors, while the southern half (West Jersey) was already held by thirty-two other Quaker proprietors under the effective leadership of William Penn. It is somewhat uncertain who orchestrated this final consolidation, but there is a strong presumption that it was Penn. Since the main purpose of these business proprietorships was to sell land to immigrants, it was vital to minimize land disputes with accurate records and accurate surveying. With a history behind them of fifteen years of bickering, everybody concerned was surely ready for some peaceful organization. Both groups of proprietors, East and West, found it useful to delegate authority to a council of nine executive proprietors, whose main agent under the circumstances was logically the Surveyor General. For the next three hundred years, the surveyor generals were the men running things in New Jersey. The right of the Proprietors to govern was revoked by Queen Anne in 1702, but their land rights remain undisturbed to the present day, notwithstanding the intervening transfer of national power to the United States of America in 1776-83. Underneath all of this hustling and arranging, with exquisite attention to details, seems to be found the hand of William Penn. Almost immediately after New Jersey was packaged and delivered, King Charles paid off his family debt by turning over the far larger combined land mass of Pennsylvania and Delaware to William Penn, urging him to make himself a vassal king in the process. The Quaker instantly declined such a thing, but the power continues to reside in the final Royal Charter. It's only a conjecture, but it might help explain the strange acquaintance between a dissolute king and an abstemious Quaker to notice that the New Jersey tour de force astoundingly demonstrates how Penn was a man who really could be trusted to get complicated things done with dispatch.

Today, for practical purposes it all amounts to a company named Taylor, Wiseman, and Taylor; but we are getting a little ahead of ourselves. To go back to 1684 a surveyed line was clearly needed between the two proprietorships, as declared by the following resolution:

"Award we do hereby declare, that [the line] shall run from ye north side of ye mouth or Inlet of ye beach of little Egg Harbor north northwest and fifty minutes more westerly according to natural position and not according to ye magnet whose variation is nine degrees westward."

To clarify those quaint words, the survey was not to make the mistake made in the layout of Philadelphia, whose streets had intended to be true north and south but by using Magnetic North are actually twelve degrees off from that. Another important point is probably unclear to modern readers, who know the town of Egg Harbor on the mainland of Barnegat Bay but are largely unaware that the "beach of Egg Harbor" was what we now call Long Beach Island, on the east side of Barnegat Bay. The southern anchor of The Line was in what we now call Beach Haven, on the north side of the inlet, although beach erosion has put the southern anchor about two miles out to sea, locating a temporary marker in Beach Haven. Hardly anyone seems to be aware of it, but reread the sentence and observe the meaning is actually quite clear. The intent of the northern end of The Line (? the Delaware Water Gap ?) is buried in the obscurity of compass markings, but comes out slightly above Trenton on the Delaware River, extending beyond the river into Pennsylvania until it reached the river again in a crook on the far side of the Delaware Water Gap. Word of mouth has it that William Penn wanted to have both sides of the river although this triangle of Pennsylvania was eventually surrendered. It seems fair to say, the line was roughly intended to run from the Beach Haven ocean inlet to the Delaware Water Gap.

|

| John, Lord Berkeley |

For its time, the survey of The Line was also a significant engineering achievement. The general plan was to lay out the course of the line in the wilderness until it hit a big boulder or anything else that was large and heavy. This became a marker along a line of 150 markers which could be used for local surveys and boundaries. After several less accurate attempts, the West/East line was surveyed by John Lawrence in 1743 and stands as the Official Province Division Line. A few years ago, a group of volunteers tried to locate all of the original markers and found 55 of them. The historical project took ten years.

All of the deeds of property in the State of New Jersey still depend on the original survey and the meticulous notes kept by the Surveyors General of these two Quaker organizations, without whose private records every title to every property would be clouded. With the passage of time, and especially the warfare of the Revolution, other copies of the surveys have disappeared. So, without the need to get ugly about it, these soft-spoken courteous folks retain a form of power it would be hard to match with sticks and stones, guns, threats or legalisms -- the only surviving record of everyone's title to his land. There is little reason to inquire further why these Proprietorships durably survived the revolution which overthrew King George III, and why no one has seen fit to enter the serious challenge to their claim of owning the whole state except for what they had already specifically sold.

Let's go back to a point made earlier. In all the complexities of the English Royal Court and uncertainties of uncharted wilderness, how did a little band of Quakers find themselves with uncontested ownership of a whole American colony? Some of the chaos of the age probably helped. King Charles unleashed his brother's armies in 1664. Also in 1664, Parliament passed the Second Conventicle Act, which provided that not more than five persons were permitted to worship together otherwise than according to the established ritual of the Anglican Church of England. This act might be described as an improvement on the First Conventicle Act of Queen Elizabeth, which provided that no one at all could so worship. However, this prohibition was so extreme it was ignored, whereas the Second Conventicle probably had some popular support. It thus can be imagined why Quakers were suddenly interested in leaving England, and not hard to understand how young William Penn was propelled into leadership by successfully overturning that Act in the Haymarket Case. Penn was both the defendant in the case and the defense lawyer, inventing the common law principle of jury nullification that has so confounded tyranny ever since. To go on with events current at the time, the Great Plague took place in 1665, making London an undesirable place for anybody to live. And finally, George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, took a journey to the new world in 1672, noting that the place now called Burlington, New Jersey was "a bravest country". Taken altogether, it is not hard to suspect this group of fairly wealthy, fairly well-educated people developed a collective resolve to buy up the pieces, assemble the parcel, and go away to live on it. Their organization into monthly local meetings, quarterly regional meetings, and annual national meetings was surely great assistance. From what we know of the broader vision of William Penn, it is fair to speculate his enthusiasm for this communications network first suggested by George Fox, or at least he's having a pretty quick recognition how it would assist the emigration venture.

|

| George Carteret |

George Carteret's widow was the last to sell out her land parcel to the East Jersey Proprietors, presumably drawn from the 1400 immigrants who had arrived in Burlington on five or six ships between 1678 and 1681. In particular, the ship Kent sailed from the Thames in 1677, bearing 230 Quakers, half from Yorkshire, the other half from London settling further south in West Jersey. Before that, Lord Berkeley had sold his half for a thousand pounds to John Fenwick and Edward Billynge, who arrived in Salem on the ship Griffin in 1674. These two soon fell out, with Fenwick taking a tenth of the land and settling around Salem. Billynge got into unspecified difficulties, probably gambling, and turned his property over to his three main creditors, William Penn, Gawen Lawrie, and Nicholas Lucas, who assembled the Proprietorship of West Jersey. Penn's remarkable talent for leadership again emerged in his statement of "Concessions and Agreements" with the Indians and new inhabitants. In another place, we discuss the reasons for thinking this document created the effective basis of the U.S. Constitution. By infusing it with the unspoken word of compromise, Penn created the main model explaining why the ratification of the Constitution remains the only time in history when thirteen independent nations voluntarily gave up sovereignty for the purpose of creating a larger vision -- which then held together for two centuries. But the voluntary union of East and West Jersey certainly has a claim to being earlier, although its claim to sovereignty is weaker.

Perhaps so, but since their interest in power was weaker, their achievement in peaceful negotiation with a secretly Catholic King was surely much greater. If some small group of religious dissidents should today emerge as having quietly and systematically bought up an entire state, however legally, the word conspiracy would be on every tongue. In this case, however, the reaction was peaceful consensus.

New Jersey Ponders a Rising Sea Level

|

| Future House Styles? |

A certain gentleman in a professional position to dominate conversations about rising sea levels, is afraid of being sued and requests his name be withheld from the following. Let's just call it hearsay, suitable only for conversational banter.

If the icecap now sitting atop Greenland should melt, it can rather easily be calculated that sea level would rise to the point where the Delaware River would be 83 feet deep. The Army Corps of Engineers would then probably have more urgent matters to attend to, but at least they would no longer have to cope with deepening the channel to 40 feet. If the Antarctic ice cap should then melt on top of it, the sea level would rise an additional 220 feet, resulting in a Delaware River 300 feet deep. There might be some dry real estate on top of Blue Mountain, but not much else on the Atlantic seaboard would be dry, so there would likely be the additional problem of keeping other people from climbing up to sit in your perch. Perhaps the Hawks would bring you something to eat.

A more immediate issue relates to the barrier islands. It is thought the crumbling of mountains into the sea accounts for the sandy beaches of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts; the more recent mountains along the West coast have not progressed to the point of piling up enough sand to start the process. The cycle of barrier islands is as follows.

Barrier islands, if left undisturbed, will gradually migrate toward the land mass behind them, filling up the intervening bay, and eventually adding to the mainland. But that's not the end of the cycle, because the continuous wave and tidal action will generate a new barrier island further out to sea. When the new island reaches a critical equilibrium with the waves and storms, it begins the cycle of deterioration all over again. Presumably, the sandy lowlands of southern New Jersey, the Delmarva Peninsula, and most of Florida are the result of many cycles of barrier islands adding themselves to the mainland. Presumably, the process will run out of sand someday, but not soon enough to worry about.

When affluent people build showplaces on the barrier islands, a great deal of concrete is laid on the island surface for roadways and parking lots, as well as jetties and other desperate efforts to prevent erosion from destroying the beaches, beachfront property, and real estate values. This process is much more active and rapid than most sunbathers seem to imagine. There are channel markers and monuments of the 18th century that are a mile or more out to sea in the 21st century. Almost a mile of beachfront has disappeared at Cape May and Cape Henlopen in Delaware. Lots of other real estate has been swallowed, but records of historical markers at the mouth of the bay have been more diligently maintained. The residents demand that sand be dredged and dumped on their beaches to keep even with the destructive forces at work. All of this ultimately useless resistance to Nature costs a great deal of money. Those who observe the contest between the protests of King Canute and the resistance of other New Jersey taxpayers to rising taxes estimate that around 2040 the cost of interrupting the barrier island cycle will become so burdensome that taxpayers will successfully put a stop to resisting natural beach erosion. The political uproar will surely be horrendous, so there is a good reason for oceanographers to avoid going public with these inconvenient truths. And all of this doomsday talk, by the way, ignores the issue of global warming, which will surely make it all the worse.

East Jersey's Decline and Fall

The colony of New Caesaria (Jersey) had two provinces, East and West Jersey, because the Stuart kings of England had given the colony to two of their friends, Sir George Carteret and John, Lord Berkeley, to split between them. Both provinces soon fell under the control of William Penn but it took a little longer to acquire the Berkeley part, so the Proprietorship of East Jersey was the oldest corporation in America until it dissolved in 1998.

|

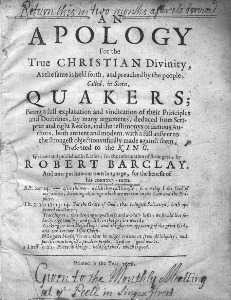

| Apology for the True Christian Divinity |

It would appear that Penn intended West Jersey to be a refuge for English Quakers and East Jersey was to be the home of Scots Quakers. Twenty of the original twenty-four proprietors were Quakers, at least half of them Scottish. Early governorship of East Jersey was assumed by Robert Barclay, Laird of Urie, who was certainly Scottish enough for the purpose, and also a famous Quaker theologian. Even today, his Apology for the True Christian Divinity is regarded as the best statement of the original Quaker principles. However, Barclay remained in England, and his deputies proved to be somewhat more Scottish than Quaker. Eighteenth-century Scots were notoriously combative and soon engaged in serious disputes with the local Puritans who had earlier migrated into East Jersey from Connecticut with the encouragement of Carteret. This enclave of aggressive Puritans probably provided the path of migration for the Connecticut settlers who invaded Pennsylvania in the Pennamite Wars, so the hostility between Puritans and Quakers was soon established. The Dutch settlers in the region were also combative, so the eastern province of Penn's peaceful experiment in religious tolerance started off early with considerable unrest. Of these groups, the Scots became dominant, even referring to the region as New Scotland. To look ahead to the time of the Revolution, most of the East Jersey leadership was in the hands of Proprietors of Scottish derivation, with at least the advantage that these were likely to have been very vigilant in seeing Proprietor rights originally conferred by the British King, continue to be honored by the new American republic.

East Jersey was probably already the most diverse place in the colonies when loyalists and revolutionaries took opposite sides in the bitter eight-year war over English rule, with hatred further inflamed when the victors in the Revolution divvied up the properties of loyalists who had fled. The earlier conflict was created by management blunders of the Proprietary leadership itself. Instead of surveying and mapping, before they sold off defined property, like every other real estate development corporation, the East Jersey Proprietors adopted the bizarre practice of selling plots of land first and then telling the purchaser to select its location. In the early years, it is true that good farmland was abundant, but inevitably two or more purchasers would occasionally choose overlapping plots of land. The Proprietors were astonishingly indifferent to the resulting uproar, telling the purchasers that this was their problem. The outcome of all this friction was that settlers petitioned London for relief, and in 1703 Queen Anne took governing powers away from both the East and West proprietorships and unified the two provinces into a single crown colony. The Queen obviously nursed the hope that South Jersey would impose a civilizing influence on the North, but immigration patterns determined a somewhat opposite outcome. Both proprietorships, however, were allowed to continue full ownership rights to any remaining undeeded property.

In later years, the East Jersey Proprietors created more unnecessary problems by attempting to confiscate and re-sell pieces of land whose surveys were faulty, sometimes of a property occupied with houses for as much as fifty years. This East Jersey proprietorship, in short, did not enjoy either a low profile or the same level of benevolent acceptance prevailing in the West Jersey province. A climate of skepticism developed that easily turned any management misjudgment into a confrontation.

|

| New Jersey Line |

The East Jersey proprietorship operated by taking title to unclaimed land, and then reselling it. In what seemed like a minor difference, the West Jersey group never took title itself, but merely charged a fee for surveying and managing the sale of unclaimed land. The upshot of this distinction was that the East Jersey group got into many lawsuits over disputed ownership, which the West Jersey Proprietorship largely escaped. The nature of unclaimed land in New Jersey is for ocean currents to throw up new islands in the bays between the barrier islands and the mainland, or pile up new swampland along the banks of the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Such marshy and mosquito-infested land may have little value to a farmer but lately has become highly prized by environmentalists, who supply class-action lawyers with that nebulous legal concept of "standing". The posture of the West Jersey Proprietors is to be happy to survey and convey clear title to a particular property for a fee, but a buyer must come to them with that request. The East Jersey method put its proprietors in repeated conflict over possession and title, with idealists enjoying free legal encouragement from contingent-fee lawyers. By 1998, the Proprietors of East Jersey had endured all they could stand. Selling their remaining rights to the State for a nominal sum, they turned over their historic documents to the state archives. The plaintiff lawyers could sue the state for the swamps if they chose to, but the East Jersey Proprietors had just had enough.

The only clear thing about all of this is that the Proprietors of West Jersey now stand unchallenged as the oldest stockholder corporation in America. It's not certain just what this title is worth, but at least it is awfully hard to improve on it.

Burlington, Capital of the Province of West Jersey

|

| Burlington County Map |

Perth Amboy sits on a high bluff overlooking New York harbor bordering the north side of the Raritan River, while Burlington sits on a high bluff overlooking Delaware Bay from the south. Each of them was originally the capital of a province. The eighty-mile strip of land between them is the wasp waist of New Jersey (Nova Caesaria) containing enough land to satisfy the needs of the handful of early settlers. This strip, as the shortest land distance between Delaware and the Hudson, seemed destined to be the commercial main line along the Atlantic seaboard. Ultimately, Scottish Quakers were comfortable moving into hilly East Jersey stretching to the northward on what used to be mainland; while the English Quakers were comfortable with the flat sandy loam stretching to the south into the piney woods that once were an oceanic barrier island. George Fox, the founder of Quakerism, had visited the area in 1671 and pronounced favorably on the fair prospect around Bridlington, now Burlington; the founding meeting of the two Quaker proprietorships was held there. Because of dissension within East Jersey, Queen Anne combined the two provinces into a single royal colony in 1701, with its colonial capital in Perth Amboy. The state capital moved to Trenton in 1790, following which the whole region prospered in response to the nation's first commercial railroad, the Camden and Perth Amboy RR. Ultimately, the flaw in this project was that the early railroad easily crossed the narrow Raritan but came to a dead halt in Camden, where it could not hope to cross the mile-wide Delaware at Philadelphia. When the Pennsylvania Railroad crossed Delaware at Trenton, the century-long prosperity of New Jersey from Trenton to Camden was doomed to slow decay.

One enduring symbol of the commercial decline of Burlington is in the second largest restaurant in town, located within an imposing bank building, whose remaining bank vault door towers over the dining area, and is only the first-floor vault. Another one like it is on the second floor. This bank turned restaurant is at the corner of two broad intersecting business avenues, one traveling north-south with a railroad track down the center, and the other leading to the fine esplanade on the bluff above the dock area. Sheltering the old docking area is Burlington Island, large enough to contain a hundred-acre lake.

Just south of the main street to the river is a handsome and well preserved colonial street, just waiting to become the center of a second Williamsburg revival, but curiously containing a house used by General Ulysses S. Grant, and -- not so curiously -- the family seat of the Haines family who have loomed large over West Jersey for many -- perhaps thirteen or fourteen -- generations.

If you go back to the other main street, the one with the railroad tracks, there is a little open-air station used by riders of the light rail Riverline which has flourished beyond all expectation as a less expensive way to commute to New York. In six months of operation, the Riverline has exceeded the ridership prediction for ten years ahead, so it's easy to predict more trains will be purchased to accommodate increased traffic, and home construction for commuters is probably not long in the future as well.

Just across the road from this little station stands a tiny one-story building, next to several imposing Federalist style red brick homes. You have to look up at the medallion over the door to identify this building as the present home of the Proprietors of West Jersey. This particular building was built in 1919, replacing an older one which used to be across the street. Inside the Proprietor building, behind the walls of small bank vaults, were the invaluable historical documents and maps of the Proprietorship, dating back to the signatures of William Penn and other notables taught about in the schools of the region. There was the Quintipartite Deed, signed by three Quakers (Penn, Gawen Lorie, Nicholas Lucas) and both George Carteret and Edward Billinge, establishing the boundaries of East and West Jersey; and there was the document of Concessions and Agreements, one of the major precursors of the United States Constitution; the Tripartite Indenture, and various early agreements of land sales. After a frustrating effort at break-in, these documents were copied and the originals sent to the State Archives. It seems a great pity to lose the testimony to the public trust that came along with having three-hundred-year-old relics easily and simply available for public view, just by walking up and asking to see them. But these are signs of the times; the greatest warning came from the rifling of the Christopher Columbus museum in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, where any passerby could honk his horn and ask to see the sea chest and crucifix that Columbus actually used on his voyages to the brave new world, that hath such creatures in it.

REFERENCES

| New Jersey, A Historical Account of Place names in the United States: Richard P. McCormick: ISBN-13: 978-0813506623 | Amazon |

Robert Barclay Justifies Quaker Meetings

|

| Robert Barclay |

As part of the dissidence and Civil War of 17th Century England, Robert Barclay the Scotsman emerged with a point of view which was structured and reasoned in detail. What was almost unique was his reduction of it to a handful of pithy "Sound Bites". Coupled with membership in a prominent family, these abilities made him a particular friend of James, Duke of York, later King. Barclay became a Quaker at an early age.

The whole point of the Reformation was revulsion against the corrupt Catholic clergy, shielded behind some impossibly convoluted legalisms of doctrine. But for the governing establishment, any reform was going too far if it led to anarchy and chaos; combating disorder was then in many ways the central mission of the Catholic faith. The establishment did recognize that public revolt against universal micromanagement led to the scaffold for Kings who insisted on it. But in their view, the need for law and order still demanded some legitimacy, if not organized law. The Rangers, who paraded about stark naked and lived in ways resembling the hippies of the 1960s, were beyond the pale. Quakers, who professed no formal doctrine except silent meditation, might be possible just as threatening. After all, silent meditation could lead you anywhere including regicide. But the Quakers at least were quiet about it.

George Fox the founder of Quakerism had already provided one basis for containing fears of anarchy, by organizing local monthly meetings for worship within regional quarterly meetings; quarterly meetings, in turn, were within an overall framework of a yearly meeting. Occasional monthly meetings might develop a consensus for wild and antisocial behavior, indeed often did so, but would have to persuade the quarterly meetings whose members naturally outnumbered them. In extreme cases, the whole religion assembled in a yearly meeting. The innate conservatism of the meek would usually silence the extremism of the rebellious few. Very few kings would deny they could go no further toward despotism themselves, without the public behind them. The Quaker problem was to demonstrate what their consensus really was.

|

| Free Quaker Meeting House |

Essentially, the answer emerged that any religion which renounced a priesthood, which even renounced having a written doctrine, still needed some sort of institutional memory. If every Quaker began with a clean slate, to develop his own organized set of moral principles, then most of them would never get very far. Even if they did, they would have no time left for milking cows and weaving cloth. Single silent meditation was inefficient, particularly if you had faith that everyone was eventually going to arrive at the same convictions as the Sermon on the Mount. The founders of Quakerism took a chance, here. To assume the same outcome, you have to assume everyone starts with the same instincts and talents; even 21st Century America has private doubts about that one. Feudal England would have rejected it contemptuously. Carried to an extreme, it was a claim that everyone was as good a philosopher as Jesus of Nazareth, as good a person, as much a Son of God. That seemed like an arrogant claim. A more humble claim was that collectively, listening respectfully to one another in a gathered meeting, the whole world would over time reach the same truths as the Creator. If not, that still was as about as close as you were going to get to an oral memory, slowly building on the insights of the past.

Like all the early Quakers, Robert Barclay spent some time in jail. He did visit America in 1681, but it is doubtful if he spent any time here while he was Governor of East Jersey, from 1682 to 1688. The King insisted on his appointment, because he seemed the most reasonable man among the most reasonable sect of dissenters, and therefore the rebel he chose to deal with.

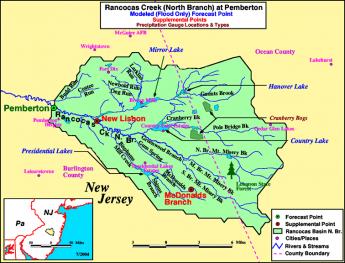

Rancocas Valley: Mt. Holly, Eayrestown, Medford

|

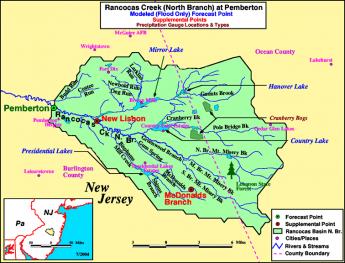

| Rancocas River |

The southern half of New Jersey, once called the Province of West Jersey, is sandy and flat, mostly not more than twenty feet above sea level. So, there is an extensive lacy network of slow-moving branches to the several creeks and rivers draining the area. Some of these rivers drain toward the Atlantic Ocean, some drain the other way to Delaware; it scarcely makes much difference. Almost as soon as the Quaker proprietors settled the area in the Seventeenth century, the broad Rancocas River (draining into Delaware) stood out as a wonderfully protected region to settle. The Rancocas wanders through the woods but is tidal all the way to Mt. Holly, which later even became a shipbuilding center. That's now the centrally located county seat of Burlington County, from which several branches extend in various directions. One southerly branch drains the water coming from Medford Lakes, once a summer cottage community miles deep in the Pines, now a place for fancy houses with lakes in the backyard. The cute little nearby town of Medford has a Braddock Tavern, reminding visitors that General Braddock stopped off here on his way to his own ambush at Fort Duquesne in the French and Indian War. The Medford-Mt. Holly Road follows the southern branch of Rancocas creek, running through somewhat broken ground greatly resembling Northern Virginia. And, that resemblance is enhanced by a number of horse farms with white-board fences, many of them looking quite historical, and very well manicured. Here's a drive worth taking, especially in late April when the trees are just budding out, the grass is green, and the azaleas are blooming. Starting in Mt. Holly, which is recognizably colonial but unfortunately somewhat under-maintained, you can recognize that the road once started at the Three Tun Tavern, of colonial fame. The confluence of creek branches made a natural place for a farmers market in the center of the road. A short distance down one of the branching streets of Mt. Holly is the red-brick home John Woolman built to keep his daughter from moving away with her Philadelphia husband. We talk more about John Woolman in another section of Philadelphia Reflections.

|

| Rancocas Map |

One of the interesting features of the "lost" colonial community along the Mt. Holly-Medford Road grows out of the Rancocas curving east toward the ocean and then branching south. That means that if you drive from Haddonfield or Camden to the ocean beaches you go through the pine woods and then come upon this ancient Medford community before you re-enter the pine barrens and go on toward the ocean. That gives the impression the Medford area was somehow a lost frontier, when in fact it was a part of one of the oldest settlements in the state. It's a strip community, running along the banks of the Rancocas from Medford to Mt. Holly; houses along the banks, farmland stretching behind the houses. Most people on the way to the shore just go through the traffic light and keep on going without realizing what they are missing. And, indeed, if all that traffic stopped to browse, it would quickly ruin the place.

Along the Medford-Mt. Holly Road is seen an occasional McMansion, with "Atlantic City" sort of written all over it, but in general, the houses are pretty upscale and restrained. There is a nursery farm which must stretch a full mile, full of flowering shrubs and trees, looking very manicured and attractive. To some extent, a nursery improves a neighborhood, since it supplies lots of flowering shrubbery ideal for the local soil conditions. But in a larger sense, a nursery is almost always bad news for a neighborhood. Every time a plant is dug up and sold, it takes away a bushel of topsoil. No farmer would normally consent to such treatment of his most valuable asset, so the sale of property for nurseries is a sign the farmers are selling out, urban development is looming. Unfortunately, this certainly also means the novel hidden river community in the pines is on the brink of being wiped out. Tourist visits are, well, now or never.

REFERENCES

| The Pine Barrens: John McPhee: ISBN-13: 978-0374514426 | Amazon |

William Penn, Excellent Lawyer, Terrible Businessman

Richard Dunn, who with his wife Mary Maples Dunn stand as the two core authorities on the life of William Penn, merely smiles when asked to describe what Penn was really all about. "What we need is to have one good biography emerge," said he, "but it isn't easy to guess what it will say". For the present, let's just sketch a few paradoxes which somehow need threading together.

|

| Richard Dunn |

In the first place, the wealth of William Penn can only be described as prodigious. His father had played a central role in restoring the Stuart monarchs, and in the course of it had conquered for the Crown the enormously valuable property of the Island of Jamaica. For these efforts, the father had been rewarded with extensive properties in Ireland and a highly influential position at Court. To all of this was overgenerously added as debt repayment, the American territories which have now become the states of Delaware, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Actual ownership of some of this was shared with others, but all of it was quite effectively controlled by young William. No one else stands even close as the largest private landholder in American history. But to appreciate the immensity of his wealth, it should be understood that he treated this property as a sort of hobby. Over the course of his lifetime, the colonies lost money, and Penn subsidized them rather seriously from his other assets.

At the same time, Penn lived vastly beyond his income in ordinary ways, becoming heavily indebted, eventually going to debtor's prison. It probably was not necessary; his sons renounced Quakerism and made a profit on the colonies after they inherited them. Although he could display remarkable organizational talent, particularly in the organization of New Jersey, his management was mostly slack, his judgment of agents often proved too trusting, and he permitted himself to be exploited by poorly-designed contracts to his eventual financial ruin. Even that might not have been serious; he displayed a towering legal mind in the devising of the doctrine of jury nullification and was the winner in a great many lawsuits. He even demonstrated he was capable of winning dubious lawsuits, soundly defeating Lord Baltimore in a border dispute over Maryland which others have said showed Baltimore had the stronger case. We know he had influence at Court, and such legal victories suggest he might on occasion have taken full advantage of it.

|

| Gulielma Maria Springett Penn |

From the sound of things, some have concluded Penn was so rich and powerful he grew careless about his own best interests, which essentially needed very little defense. In particular, he gave this impression to his fellow Quakers, who concluded he did not need nor likely would stoop to collecting what he was owed in taxes and property sales. This cavalier attitude encouraged the early Quaker merchants to follow their own advantage without shame, and as it happened with great vigor. The Constitutions he devised for the colonies are frequently cited as the brilliant cornerstones of fairness and stability, ultimately the models for much of our present Constitution. Penn really was sincere in wanting to provide a better life for the working people than they could have at home in England. But in the Seventeenth Century, the modest role he devised for the Proprietor commanded little respect and was not one his aggressive clients would have chosen for themselves in his position. Perhaps the most generous description of their passive aggression would be that he taught power and governance to be the collective possession of the whole Quaker meeting, so the leaders of the meeting simply took him at his word. For their part, there can be little doubt of their commercial talents; trade and industry immediately thrived in the colony. However, sharp, aggressive trade and commerce were not things a gentleman would himself want to associate with.

Unfortunately, the historical records of the early colonies are not good; for the most part, we have to surmise the struggles and frictions between a rich, financially careless, and sincerely earnest theologian in his contention with a group of poorly educated strivers who had been told he regarded each of them to be his equal. As the saying goes, he was rich beyond denying. And therefore, he was probably arrogant beyond his own ability to see it as a flaw.

Equal before the law, perhaps, and equal in the prayers of First-day Meeting. But everything about his upbringing, his social circle in London, and his staggering wealth suggested that even a saint would have trouble believing, deep in his heart, that these were truly his equals. And even if perchance he did believe it, they would not have believed it for a moment, had their positions been reversed. Penn certainly acted as though he believed in religious freedom, serene in the idea that if every person earnestly thought hard about ethical issues, everyone would eventually reach about the same conclusion. The elders of the meeting, however, behaved in ways which suggested they would personally prefer non-Quakers to settle somewhere else, and given half a chance would create Quakerism as an established church. There seemed to be those who felt that Friend William was perhaps a little too trusting. And anyway there were some obvious paradoxes. William Penn kept personal slaves.

|

| Hannah Callowhill Penn |

With two wives, William Penn had thirteen children. Among them was considerable diversity of opinion, along with the same tendency to rebellion found in any two generations. Early illnesses and chance led to the emergence of those children who renounced Quakerism and showed no shame at all about wanting to have money in order to spend it recklessly. One would have supposed that a man of Penn's intellectual stature would have been able to control his family better, but his own reckless youth had been so extreme that he had few arguments available when, as seems virtually certain, rebellious children defended themselves by reminding him of his own indiscretions. William Penn displayed absolutely no sense of humor; a touch of it would have been useful in mastering a family and friends who were undoubtedly having a little trouble knowing what to make of this apparition in their midst. Some equally pompous Pennsylvania merchants might have had difficulty denying that in their passive aggression, they occasionally resembled the spoiled brats with whom he found he had ample family association.

REFERENCES

| Remember William Penn, 1644-1944: A Tercentenary Memorial : Edward Martin: ISBN-13: 978-1258369934 | Amazon |

Dingman's Ferry, Below Port Jervis

|

| Dingman Ferry Bridge |

Because the area was once covered with a glacier, the northeast corner of Pennsylvania is fairly deserted. That's always been good for hunting and fishing, and more recently is good for skiing. Although the topsoil is poor, it's a beautiful area, practically guaranteed to provoke confrontation between the environmentalist movement and the Marcellus shale-gas extraction industry. The history of anthracite coal demonstrates locally that the mineral extraction industry always wins these arguments in the short run, but ultimately the land seems to heal itself without much help from people living in city apartments. The followers of Gifford Pinchot and Teddy Roosevelt are slowly learning to concentrate on minimizing the damage and forcing the extraction industries to pay for clean-up afterward. Right now, this semi-wilderness area is a remarkably beautiful but deserted forest within two hours drive of Philadelphia and New York City. It contains the headwaters of the three main rivers of Northeastern United States.

Crossing those three rivers was the main geographical problem for the Connecticut invaders of Pennsylvania. Today, the landscape is not a great deal different except for the absence of Indians, and crossing the three rivers is the main event. There's a Hudson River bridge at Newburgh, and crossing the Susquehanna at Wilkes-Barre is a placid bridge within a town park. From the point of view of the Interstate highway, crossing Delaware occurs very near the highest point in New Jersey, over a deep rocky gorge with boaters deep below. Since the traveler is at a peak point within a long wide mountain valley, the view is spectacular in several directions.

However, for centuries the builders of roads had to operate on a modest budget, and the only reasonable place to cross Delaware in that region is a few miles south of Port Jervis, at Dingman's Ferry. The Dingman family prospered at their trade for many generations before they modernized and constructed a toll bridge, which is now one of the few remaining toll bridges in private hands, and possibly the oldest one. You don't have to ask the two jolly old toll collectors whether they are part of the Dingman family because they certainly act like it, adding to the wad of dollar bills in their left hand as they greet the fellas, josh the girls, and wave directions with a free hand. A quarter-mile to the south of the bridge on the Pennsylvania side is the entrance to a trail leading to a National Park Service station. The Park Guards are a friendly sort, most of them freely admitting they are members of the Dingman clan, available to help tourists interested in a trail walk, including a visit to the local waterfall. In spite of all this family connection, and Park Service training, nobody at the station had ever heard of the march of the Connecticut invaders. Or of the Proprietorships of West and East Jersey, or of the line between them which allegedly ends at Dingman's Ferry. The best they could do was the point to the local cemetery, which has a big rock at the entrance that somehow has some particular significance, or other.

As it turns out, the cemetery is quite large, with surely a thousand or more gravestones, a great many of which fly American Legion flags for veterans of one war or another, and many more are decorated with fresh flowers. Only a corner of this graveyard touches the curving road to The Bridge, and just inside the entrance is a very large, unmarked stone. Trees have been planted nearby, and their roots have half-covered the rock. But the roads and the cemetery, in general, seem designed around it. There's no marker to explain it, any more than there is a plaque at Stonehenge. As the Park Ranger said, it has clear significance, but no one now seems to know what it is significant of.

Well, if no one is likely to contradict, let's make the timid suggestion that this may be the terminus of the line dividing East from West Jersey. Yes, it's in Pennsylvania. But there is nothing more likely on the New Jersey side of the crossing, and the current Surveyor-General of West Jersey, William Taylor, is firm in the belief the line terminated at Dingman's Ferry. William Penn had hoped to control land on both sides of the river, and when he acquired Pennsylvania in addition to New Jersey, the issue became moot. The style of the survey had been to start at Beach Haven ("Ye inlet of ye beach of Egg Harbor") and follow the compass until it hit something large and heavy. That rock was marked, and another survey went the next step. About fifty of these markers have been discovered by later explorers, and officially represent the underlying fixed line which serves as a survey basis for every property in the state of New Jersey. Since I own some property in New Jersey myself, it seems important to be sure I know where it is, or else some trial lawyer may try to take it away.

15 Blogs

Defining and Naming New Jersey

A lease from James, Duke of York to John, Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, on June 23, 1664, first gave New Jersey its name and defined its boundaries.

A lease from James, Duke of York to John, Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret, on June 23, 1664, first gave New Jersey its name and defined its boundaries.

Jersey

Understanding New Jersey means understanding its unusual geography, and its Quaker origin as one of the three colonies owned by William Penn.

Understanding New Jersey means understanding its unusual geography, and its Quaker origin as one of the three colonies owned by William Penn.

Lansdowne

John Penn, the last of the Penn Proprietors, lived in a mansion near what is now Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park.

John Penn, the last of the Penn Proprietors, lived in a mansion near what is now Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park.

The Heirs of William Penn

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

Unexpected Benefits of a Lurid Past

The legal prohibition of liquor caused corruption of society which was worse, and lasted longer, than the problems it might have solved. Here and there, some surprising advantages lasted a long time, too.

The legal prohibition of liquor caused corruption of society which was worse, and lasted longer, than the problems it might have solved. Here and there, some surprising advantages lasted a long time, too.

New Jersey: A Keg Tapped at Both Ends (2)

The New Jersey legislature began by ratifying the Declaration of Independence in Haddonfield, then moved to Trenton and concerned itself with debts, then with railroads, then corporations, and now -- with debts, again.

The New Jersey legislature began by ratifying the Declaration of Independence in Haddonfield, then moved to Trenton and concerned itself with debts, then with railroads, then corporations, and now -- with debts, again.

Burlington County, NJ

Line Dividing East from West Jersey

Although England had owned New Jersey for 17 years, it was unsettled until purchased by Quakers. By 1684 ownership was totally in the hands of two Proprietorships, or corporations, of Quakers. The boundary separating East from West Jersey was a line of 150 boulders from Beach Haven to Trenton. Every land title in the state is based on this survey.