2 Volumes

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

(3) Obamacare: Speeches

New topic 2015-09-25 21:48:47 description

Social Politics

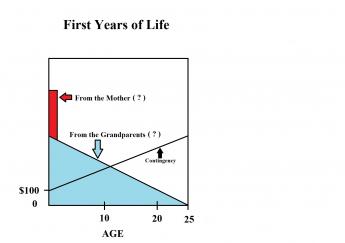

After the Second World War, the medical costs of children were small enough to be written off cheerfully. We entered an era of lavish gifts to children's hospitals, probably prompted in part by the memory of obstetrical write-offs. Many of these gifts paid for research costs, but part of them went for rather lavish hospital facilities, making it impractical to consider recovering the losses of the past. In all this uproar there was room to develop a credit system, but our mindset had been changed. Primarily, the child was not legally responsible for the debts. From the point of view of the indigent mother, her only recourse was to disappear from sight. If she had several children, it was beyond her imagination. As it still would be today, in many cases. If we had taken the legal position that half of those costs were the responsibility of the child, they at least would not have multiplied within a multi-child family, so the prospect of a hopeless situation might not appear so soon.

Equal Pay for Equal Work(?) The same problem now surfaces when the girl first applies for a job with health benefits. She is of an age group with trivial medical costs on average, except for pregnancy and all its associated costs. Her premium cost is high, a similar male would be quite low. Even with considerable cost-shifting, the male is a cheaper employee. In fact, males can easily take their chances of being uninsured, while females would be terrified of being uninsured. It is not going too far to suggest the whole configuration of employer-based health insurance is a result of trying to patch up this situation, working with what you have. I believe the whole system of employer-based health insurance would not have got so advanced and intractable, but for lack of an alternative to this patchwork. After all, a rationalization of this issue by male-female pooling would not affect the employer, the tax deduction would be the same for him in any case. For people in marginal finances, there is too little flexibility to provide room for gradual workarounds, and the employer generally has other things on his mind. It might take ten years to show an effect, but a system of re-assigning personal responsibility on a legal level is the first step in taking risks with a benefits program. Let's summarize it this way: health insurance up to age 40 is insuring obstetrics plus the risk of getting sick. After age 40, it becomes less a matter of risk, and more a matter of reimbursing actual health costs. Obstetrics needs to be taken out of this equation, and the cheapest way to do it is through a hundred dollars added to the contingency fund of an HSA at the time of birth, but that's a later step.

Mandates do get immediate attention, but the distraction often makes evasion of mandate seem a quicker route to savings than slow, steady efficiency improvement. We invite the reader to revisit the major advantages of incentives over rigid mandates. In particular, the concentration of medical care into the end of life permits idle income to be invested, creating wholly new revenue in the meantime, and making less borrowing cost necessary. Potentially, savings might be doubled by reversing some borrowers and lenders. Contrariwise, the limitation of government revenue to taxation and borrowing lowers interest rates, ultimately favoring inflation of medical costs. That's just supply and demand. It's not unusually true of healthcare financing, and we don't advocate changing it. It's just a fact we might as well use to general advantage in health insurance re-design.

Equity Investing Within IRAs. Workers tend to overvalue labor and undervalue risk-taking, so they use their voting power to force interest rates down by increasing government debt. As a consequence, interest rates are generally too low, and debt levels too high, even though demographics are now forcing nearly everybody to become an investor for his old age. Ruminations along these lines suggest a more efficient balance results from increased equity investing by everyone, regardless of how he earns his primary living. Medical care is just an example of consumer necessity, big enough (18 % of GDP) to bend the curve back to commodity levels without undue resistance. If the topic became hula hoops, these ideas probably wouldn't work, because people would simply eliminate hula hoops. And by the way, by "equity" investing we mean the use of total market index funds, not direct investments in companies themselves.

We previously calculated passive investment of healthcare payment float returning 7.5% might do the entire job, of reaching a lifetime individual health cost averaging $300,000 in the year 2000 dollars, without private supplements. It's another way of saying equity investing could reduce costs on average by $200,000 per lifetime. But that's on average, and people get sick in bad market years, too. If you want to do it all without supplements or subsidies, you must increase the interest return, engage in a risky investment, or reduce the lifetime medical cost with research. But the investing approach promises to make a substantial improvement without affecting medical care very much. That's the better approach when you have no precise way of estimating future costs. Experience is showing there are better investing years and worse ones too, but it gets pretty tough to average more than 5%, net. So if we could find 2.5% extra somewhere, a cost-free health system might be in sight. Successful corporations can probably expect to make 10% profits for their stockholders, so the addition of 50% worth of stock producing a 10% return, might result in an overall portfolio yielding 7.5%. It wouldn't be easy to get there, but it identifies the goal.

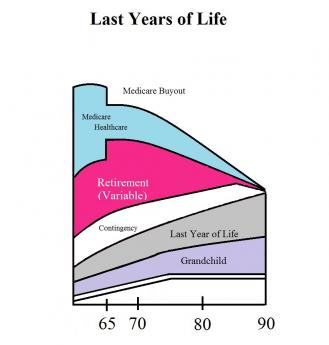

Protracted retirement is a hidden cost of improved medical care.

|

Retirement Costs Attributable to Medicare (?) However, we regard prolonged retirement as a hidden cost of improved medical care, currently unfunded except for Social Security. To cover this cost for the twenty-five years from age 65 to 90 would require an additional $876,000 at the 65th birthday, assuming we get the 7.5% return. What we have come to is the problem of making every inhabitant of the nation into a millionaire. But compare that with $2500 at birth and $29 a month (from age 25 to 65) to supplement Social Security by $1,000 a month. Although it may not sound it, this is really a bargain, incompletely certain of success. If a married couple both did this, they would enjoy a comparatively modest retirement of $4000 per month, including Social Security. It can thus be seen that although retirement is still a bargain, it is far more expensive to provide extra retirement than the healthcare which, in a certain sense, created the need for it. In that sense, the later protracted retirement living is the most expensive part of healthcare costs. It needs no apology, it is what it is.

However, the difficulty we have in proposing a system for reducing the cost impact is primarily explained by the rather ambitious size of the cost, which is likely to get even worse. It is not entirely to my taste to propose a Scandinavian cooperative system to pay for it, and no doubt some will propose short-cuts and expedients, but at least this approach has a chance of breaking even, whereas pay-as-you-go and inflation financing just kick the can down the road, for another generation to face the grim realities of still higher costs. The only remaining alternative which might work is to continue spending as much on research as we spend on Medicare. It seems likely science will eventually cure cancer. But unless it cures cancer cheaply, all is for nothing. Even in spite of being offered a bargain, a great many people will take their chances on a government bail-out, rather than accept the frugality being suggested. That's why membership has to remain voluntary, and why hard times are surely ahead of us.

Summary. We seem to wander from the subject, but it is intentional. Emphasizing the difficulty of solving the health financing problem by conventional means, makes it easier to consider unconventional ones. We ask for sober reflection on the advantages of the following:

1. Considering at least half of the cost of Obstetrics. to be a financial debt of the child.

2. Considering each grandparent to owe a replacement debt of one grandchild's medical costs, up to age.26.

3. Considering it a government obligation to subsidize those who cannot afford these obligations.

Conflicts of Interest. In order to avoid turning this idea into either a boondoggle for hedge funds or a gigantic tax dodge, it might be wise to limit the portfolio to health-related corporations. Over the past century, we have seen Medical Societies own malpractice insurance companies, medical journals, post-graduate educational tape recordings, health insurance companies, and probably a few hospitals. Even more enticing would be drug companies and medical device makers. In all of these areas, the danger of conflict of interest would arise, but somehow it has always been managed. In fact, medical ownership or control of ancillary services has probably declined, although it is likely the medical owners have usually been happy to be rid of the distraction. Medical malpractice insurance is probably an example of medical owners filling an unfilled need. When competition returned to the field, the owners have generally preferred being rid of the unpleasantness, rather than enjoying profits from conflicts of interest.

If to all these associated for-profit corporations, is added the educational loan system for healthcare providers, plus the myriad institutions to house the patients, it starts to become clear the danger of monopoly control is a small one. While there is no doubt local monopolies would arise, and some instances would occur of subscriber control of them, the industries now making up 18% of a gross national product would greatly dwarf the number of providers. Physicians were paid 20% of the healthcare dollar in 1980, but only 8% today, as an example of how great the field has become dominated by non-professionals. The scientific field has become so huge and so attractive in itself, that comparatively few professionals of eminence are interested in business careers. It is true professionals lacking eminence are sometimes more attracted to such activities, but the resulting peer pressures strongly favor the power of a few eminent professionals who allow themselves to get involved. In a power play, the rest of their colleagues will support them.

Paying for Healthcare

At my age, I reflect on inheritance tax once in a while. It's taxed at sixty percent, but there's some consolation. Every time I spend a dollar, I tell myself I'm really only spending forty cents. In spite of a lifetime of resisting such thoughts, it does affect my attitude about spending. And it must affect corporate decision-makers, at least somewhat, as a consequence of paying twice as much income tax as I do. Come to think of it, corporate tax is a double tax on the earnings of the shareholder. Since corporations flourished as outgrowths of the Industrial Revolution, they are probably an extremely efficient way to conduct business, or they couldn't withstand such tax treatment. No doubt, small businesses resent their disadvantage.

But the point to notice is how this tax treatment must affect willingness to spend company money. When companies give a dollar of health insurance to an employee, it really only costs them forty or fifty cents. It isn't even the employer's money, it's the government's tax money. And since the employee gets the insurance for something like seventy-five cents on the dollar counting his own tax reduction, the resistance to spending is even further reduced. As a matter of fact, a clever financial officer can improve on these numbers, but the point is sufficiently made without going into that complexity. Both the employee and the shareholder enjoy a greatly reduced reluctance to spend company money on health care. It just has to be true. And it also just has to be true that the half of us who don't get such a tax dodge, resent it.

It must additionally be true, avoiding this heavy taxation is a major factor in why we have had an employer-based system for a century, with progressive inflation in evidence. It probably contributes to our willingness to tolerate a loss of coverage when employment terminates, and steady price inflation when it doesn't. Rather than go on with a list of problems created by the loss of price resistance, let's get down to the root, in the very design of the system. We have had the wrong kind of insurance for a century. Now that corporate income tax has risen to the highest in the world, our corporations are seen to be fleeing to foreign countries to escape it. So, perhaps it is time to do something about it.

Health insurance is upside down. It pays for small items, and then it runs out of money for big ones. "First-dollar coverage" was once the favored style, but nowadays, for the most part, a token deductible is imposed, but the principle is the same. Even before the Great Depression, young people had comparatively little serious illness and demanded "something for their money." In a sense, it really doesn't matter what the motive was, we started with ensuring small illnesses and tended to run out of funds when expenses really got heavy. Whereas, if we had been concerned with getting the most insurance for the money, we would have begun with very expensive illnesses and then paid for cheap ones only if money was left over. Expensive illness is a threat to everyone, but medical catastrophes are fairly rare. The technical way to achieve this is well worked out, it's called high-deductible insurance, and its motto is "The higher the deductible, the cheaper the premium." Back in the 1960s, I was offered a $25,000 deductible policy for $100 a year. I forget, but I believe it had a top limit of a million dollars coverage. Almost everyone would be floored by a million dollars of expenses, but almost everyone (in spite of their protests) could afford $100. Although you probably couldn't get the same prices, that still seems like the kind of health insurance everyone ought to have. And, regardless of current discussions, it's the kind of insurance we are always going to have unless we wake up.

If you can afford the kind of coverage that includes paying for cough drops, go ahead buy it. But if you are talking about mandatory coverage for everyone, start with catastrophic coverage and then shrink the deductible to what you or the government can afford. And then stop, because you can't afford it. There's really nothing hard about this..

Two Exceptional Health Coverages

There are two exceptional situations which might also be considered for universal coverage, even mandatory coverage if you insist. They are the first year, and the last year, of life. Some people get Tuberculosis, some people get cancer, some people live to be a hundred. But absolutely everybody is born, and everybody dies. Those are the two most expensive years of most people's lives, they almost always occur in hospitals, and nobody can fake them. The hospitals and Medicare keep careful records, so we know what they cost, both individually and on average. If we reimbursed the average cost to whoever paid it, the administrative expense would be small. The reason for doing this maneuver would be to take these costs out of the catastrophic insurance cost, both smoothing it out, and reducing it by 15%. There would be a transitional cost, because of the differing number of years before death appears. On the other hand, it would take a number of years before the births came up to average. But two major health costs would be universally covered.

Paying for the Last Year of Life: Everybody an Investor

What is proposed in this section sounds a little funny the first time you hear it. Since so much of health cost is concentrated in the terminal illness of the last year of life, and since everybody has the last year, why not lump it with life insurance? That is if we pay for distressed widows and orphans, why not also pay for the terminal illness costs? Everyone who hears such a proposal asks why would you pay to cover what is already covered by Medicare? And although there is no mechanism in existence to do it, it still isn't clear why you would want to do things differently.

In the first place, when you are dead, someone knows exactly how much it cost. It would put an end to over-insurance and under-insurance, either one of which is efficient. Furthermore, someone would know how much everybody costs, so you could reimburse Medicare (mostly) in a lump sum for the average of what they spent, greatly simplifying the path overhead. Why would you want to do that? Well, Medicare is 50% subsidized by selling bonds to the Chinese, and neither Medicare nor China can afford to continue being so casual. Furthermore, Medicare costs are destined to be pretty volatile for a while, but eventually to be reduced to nothing but everybody's terminal care costs. If that's where we are eventually going, why not plan for it in advance, and gradually adjust for what it will cost, as the final costs emerge? Let's describe how it might work.

In the first place, we can predict that health costs will be comparatively small in childhood and early life, slowly growing to that final terminal illness. It's clearly suited for low premiums gradually growing by compound interest to pay a huge final debt, just like life insurance. When you look at how we are doing it at present, you see it almost has to save money. Because we are running a huge transfer system from working people to non-working ones, we only start the compound income after 25 years of childhood, followed by forty years of paycheck deductions, followed by thirty or so years of paying Medicare premiums. Its premises dictate you must do it somewhat like that, but there's the entirely too much-hidden cost for too long a period of time, subject to political and regional whims. If you only focus on the certain conclusion of the dance of death, you have a steadier goal and a more efficient mechanism. What's being proposed here is a second insurance company, steadily building up a reserve to pay a second insurance company (Medicare) which continues to run on term-insurance principles. When one insurance company pays the debts of a second insurance company, it's called re-insurance. Terminal care re-insurance. One year's risk should be sufficient to begin the process, but eventually, it could cover the last two or three years of life, just as well. As the money rolled in, it should be possible to direct the last few years premium to other generations, as will be described in subsequent sections of this book, and skipped over, here.

So, it might be replied, we are here proposing two insurance companies for the health of the elderly, instead of only one, which we already have trouble paying for. That's true enough, except the premiums don't have to remain the same. The steadily lengthening longevity of the population should easily take care of the problem, although the grim experiences of Fannie Mae and Freddy Mac might suggest more precautions would be wise. I plan to stay away from this dangerous topic since the politicians who would need to consider it is probably even more cynical than I am. Perhaps they can devise mixtures of public and private companies to protect us from ourselves.

========================================================================================================================================= But it could be possible if less than a dozen words of the law were changed. At present, a Heath Savings Account terminates at age 66, and the residual contents are transferred into an IRA. The original hope was your health worries were over as soon as you were eligible for Medicare.

If this termination were to become optional, or if it could be supplemented with the last year of life escrow, the following would become possible: Sufficient money could be deposited, sufficient to generate enough investment income to pay it off at death. The final amount required would be the average amount Medicare is now paying, times an inflation growth factor, also obtained from Medicare records. The investment growth factor would be somewhere between the average long term interest rate on Treasury bonds, at a minimum, and the average total American common stock index fund growth rate, over the past 50-100 years, as an upper bound. It will surprise many to discover that the latter has averaged about 11% for the past century because of compounding. Figuring backward from these two historical values will arrive at a required growth rate, for the average aged person, obtainable from census records. From this data can be calculated how much growth would be required. Having this, the amount of deposit necessary could be calculated.

My own estimate is the last year is 8% of the total of the $350,000 total life cost generally assented to, or $28,000. At 6.5% average return (my estimate), this would generate $28,000 after 84 years from a single deposit at the birth of $150. However rough these estimates may be, they suggest a project along the lines suggested, is entirely feasible. If safety technicalities are an issue, it should be possible to take delivery on an index fund, and put it in a bank lockbox until it is needed.

A second purpose of establishing an end of life transfer now emerges: It could generate a considerable portion of its costs by pre-funding itself at prevailing rates of return. The last year of life is the most suitable for this treatment. Whether to extend the concept to the entire of catastrophic health care, is riskier, and should probably be undertaken in steps.

Paying for Children

By far the hardest part of healthcare to find a way to pay for, is the newborn child. There is no opportunity for pre-funding, the cost is considerable, and the parents are in marginal financial shape, themselves. No one has proposed a satisfactory solution, except those who say the cost is negligible, which is not true at all. Accordingly, I have proposed we take advantage of another feature of increasing longevity.

The grandparents, who were little more than a theory in 1900, have aged to the point where they often overlap by a generation. I propose we overfund Medicare at birth so that it grows to the size of a considerable inheritance at death. We can then take advantage of the extra 21 years of longevity thus included in the family. Thus an extra $28,000 bequest can be generated from investment income and put in trust for a grandchild as a dwindling asset, sufficient to cover the first 21 years of life. This is the present limit of the statute of perpetuities, and need not disturb it.

Although the details are complex, they follow the pattern of the death benefit, and will not be repeated here, The estimated extra cost is $42 per child, which seems to bring it within the boundaries of what the average person can afford, and/or the government could subsidize, with a considerable margin for error.

Although it is possible to imagine many extensions of the ideas in this short paper, I would caution against going too far without some experience to support it. In fact, what is proposed here, should e tested in an incremental manner.

Health and Retirement Savings Accounts: to Privatize Medicare and Save Money, Too

As earlier sections outlined, Health Savings Accounts were developed by John McClaughry and me in 1981, as a bare-bones health insurance scheme for financially struggling people. The package consisted of the cheapest insurance we could imagine (a high-deductible catastrophic indemnity plan with no co-pay features), attached to what others have aptly described as a tax-sheltered Christmas Savings Fund. That's essentially what you get if you sign up, today. What was this linkage supposed to accomplish? The Account part was intended for folks who must accept a high deductible to lower the cost of health insurance, but who then struggle to assemble the deductible. A combination package thus became the cheapest healthcare coverage we knew how to devise -- the higher the deductible, the lower the premium.

As deposits build up in the account, the remaining deductible falls toward zero, but the premium of the insurance does not rise because the extra cost is excluded from the insurance part. At that point, you could easily describe it as "first-dollar coverage for a high-deductible premium." Stepping through the process should clarify for anyone, how expensive it had always been to include the deductible costs inside the insurance! It certainly compares well with so-called "Cadillac" plans, where the underlying motivation really was to include as many benefits as possible, money no object, with someone else paying for it and then writing off its cost against artificially high corporate tax rates -- which were then eliminated by the same healthcare deduction. If the government elected to subsidize our plan to provide it even more cheaply to poorer people, inter-plan subsidies could easily be arranged for seriously poor people, just as the Affordable Care Act does, by offering to transfer the same subsidy to it. Although HSA is itself absolutely the cheapest, neither it nor the Affordable Care Act is completely free of any cost, so additional features like charity must be supported by additional revenue from somewhere. Cheaper is simpler, simple is easier to understand. But cheaper doesn't mean free.

|

First-dollar coverage by any mechanism generates the danger of spending health money unwisely. That undesirable feature was neutralized by letting subscribers keep what is left over at age 65, thereby generating (and greatly increasing) retirement income. Retirement income is generally in short supply, and there may exist a future danger, that well-meaning attempts to supply generous retirements would destroy this incentive to be frugal. But right now it isn't a worry.

Other Incentives. One thing we didn't immediately verbalize was, making it a bargain entices people to save, even when they are sort of inclined to consume. We didn't think to include regular paycheck withdrawals, but that's another common savings incentive with proven effectiveness. Having loose cash does seem to create a vague itch to spend. But the Health Savings Account specifies an invitation to save for health care, using any surplus for retirement, a much more specific appeal. With that addition, it became a more attractive program, appealing to a larger segment of the population without reducing its appeal to the original ones. Our reaction was that everyone was complaining about high health costs, so the more people Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts appealed to, the better.

The real game-changer was this: When a subscriber later acquires Medicare coverage, anything left in the fund is automatically turned into a tax-exempt retirement fund, an IRA. As enrollments in HSAs began to boom, it was realized this provision creates an unmatchable retirement fund if someone puts extra money into the account. I wish I knew whose idea originated that. So you might as well say the basic package has three parts: high-deductible health insurance, a spill-over retirement fund, and a Christmas savings fund to multiply savings with compound interest -- useful for both purposes.

It's amazing how many people think HSA has only one feature. It is a double savings vehicle for two sequential stages of life, with the tax advantages of the first stage getting it on its feet. The separation of the account from its re-insuring catastrophic health insurance, also identified the incentive to save, distinguished from a natural desire to share the risk like a hot potato. Adding compound interest adds particular attractiveness for the later stages of life because compounding takes a long time before it means much. It connects two benefits end-to-end, lengthening the time for compound interest to become meaningful for the second one, as it would not if it waited for retirement to begin. We eventually realized the deductible-funding and overlapped retirement-funding package, was the most attractive investment vehicle most ordinary folks could find. Beating it as a retirement fund alone was therefore nearly impossible.

Hence the double-strong incentive to save, sadly missing from every other form of health insurance. We strongly suggest adding this feature to Medicare, which badly needs some such incentive, although retirement is parallel to Medicare, not sequential. Experience shows this unique set of double incentives to buy HSA was effective, so a 30% reduction in premiums for total health insurance began to emerge among pioneer clients, not merely claimed in theory. The recognition of all these advantages led millions of frugal people to sign up without an expensive marketing effort. Everything seemed to fall in place. Even though mandated coverage might have speeded up acceptance, slower adoption avoided the catastrophes of taking on more than could be handled.

So that's where HSA stands today -- the best little health insurance idea available anywhere, unless someone monkeys with it. Even the remote possibility of getting very sick very often was covered by adding the feature of a top-limit to out-of-pocket costs, paid for by dipping into a small portion of savings generated by other features. Anyone who thinks of a better health insurance plan than this one is welcome to offer it. Every addition added to its complexity, but every feature added to its cost-saving.

Let's whisper a reminder to resisters: the policy is owned by the individual rather than his employer, so it doesn't suddenly stop when you change employers or move between states. To a different audience we could whisper, it could bring a second bad feature closer to an end, the business of paying for Medicare with debts which have to be borrowed from foreigners. The Account gathers interest, instead of costing interest. The best part is: it induces the subscriber to hold back from using the account, saving it for more distant requirements, which inconveniently come without warning. Paying for your old age is wonderful, but starting to save while young is vital, and more likely to work. Most plans now maintain an upper limit to the subscriber's out-of-pocket costs, protecting against a second illness with its second deductible. When we say, "That's all there is to it," we really mean that's all the advantages which have so far emerged. It's ready to be renamed HRSA, the Health (and Retirement) Savings Account.

Technical Amendments, Needed at Present.

Now, let's pick the nits, noticing how hard it gets to improve on it. If Congress could pass a few amendments, the following flaws could be more or less immediately repaired:

1. Full Tax-Deductibility. Attractive as it is, HSA still isn't as fully tax-deductible as the health insurance many employed people are given at work. The savings and retirement portions are indeed tax-sheltered, but unlike some of its competitors, the high-deductible health insurance itself stands outside the funds (as what insurance experts might call re-insurance) and isn't covered. Employers get around this difficulty for their employees by buying the insurance themselves and "giving" it to the employees. Without monkeying around with this rather dubious maneuver to maintain tight control, we propose the premiums for the Catastrophic health portion of the HRSA might instantly become tax-exempt if the Savings Account paid the premium. That would appear cheaper for the Treasury, than proposing to make the whole package deductible. Because the other parts are already tax-exempted.As an aside, it's true the subscriber to a Health Savings Account is not fully covered in his first few years, until the account builds up to the deductible. That makes a very good argument for starting the accounts while you are quite young. At first, that was a concern, but it has proved largely unnecessary to provide for it, among young healthy subscribers. Apparently, by the age hospital-level illness becomes common, the ability to meet the deductible has mostly been achieved. Nor has it proved necessary to resort to sliding-scale deductibles hidden in the slogan, "the higher the deductible, the lower the premium" -- probably because lower premiums immediately transform into more money for saving. These features might be reviewed when self-selected frugal applicants taper off since HSA enrollment has so far attracted younger enrollees. For the moment, sales incentives seem adequate; everything else may be indirectly changed by HSAs, but very little is changed directly.To permit something like that would require a one-line amendment to the HSA enabling act, but would restore fairness to the system, and bring out how much cheaper the Health Savings Account really is. Making it cheaper means more people could afford it, thus relieving the Treasury of the need to subsidize those people under the Affordable Care Act. That would compensate for some of the loss of revenue to the IRS for making the Catastrophic Health Insurance tax-exempt. Regardless of how the CBO scores this complexity, it should be remembered that poverty is not a lifelong condition for most poor people; after a temporary period of poverty, many if not most of them rise toward becoming tax-payers. Equal treatment under the law is itself a valuable asset; it could paradoxically be provided by lowering the corporate income tax since many corporations already eliminate the corporate tax with the healthcare deduction. But that's not so self-evident, and politically hard to explain. If the Congressional Budget Office would extend its dynamic scoring to include retirement taxation on the HSA's eventual compound interest (instead of limiting its horizon to ten years), it would visibly be better to choose the compromise of letting the Accounts by the reinsurance.

2. A better Cost of Living Adjustment for HSA deposit limits. There is presently an annual limit of $3400 for deposits into Health Savings Accounts, whose limits have seldom been raised very much. This new COLA should be formalized into a continuing cost-of-living adjustment which is somehow related to the current rate of inflation in the medical economy, and perhaps takes account of a potential transition to HRSA by people over age 60. These late arrivals simply do not have sufficient time to catch up within the present deposit limits, even should they possess the savings to do so.

3. Age Limits for HSAs It is a quirk of compound interest (originally noticed by Aristotle) that interest rates rise with the duration of the investment. Consequently, much or most of the revenue appears after forty years, and consequently HSAs get more valuable with advancing age. To put it another way, young people contribute more time for interest to grow, old people must contribute more money to catch up. At present, HSA age limits are set to match employment, but the HSA will inevitably focus on funding retirement. Removing all age limits might go a little too far, but would substantially increase the amount of investment income generated, at almost no extra cost to the government. It might also supplement the platform for funding childhood health costs, a problem age group which stubbornly resists improvement. It might greatly enhance revenue for older subscribers as well (by reducing their health insurance cost), the surplus from which could be used at their death for the grandchildren generation.

Young people contribute more time for interest to grow, old people must contribute more money to catch up.

Extending the age limits would potentially also serve as a platform for re-adjusting dangerous imbalances in the healthcare financing system. We are fast approaching demography of thirty years of childhood and education, followed by thirty years of working life, followed by thirty years of retirement. Substantially all of the revenue comes from the middle third, while the remaining two-thirds of the population contains most of the health costs. To some extent this is unavoidable, but the whole health financing system becomes a dangerously unbalanced transfer system for well people to subsidize sick ones. It is possible to foresee the beginnings of class warfare, based on age alone. Consequently, society would be well served to create the more stable system of subsidy between yourself as the donor and yourself as the beneficiary. The alternative is to continue the process of having one demographic group collectively subsidize two other groups of strangers who generate most of the cost. Eventually, this could induce well people to dump the burdensome sick people. I hope I am unduly concerned, but to extend the age limits for individual self-financing seems a very cheap way to begin stepping out of that particular mud puddle.

Finally, there is a conflict with inheritance laws. By extending the age limits for the funds to the legal boundary of perpetuity (one lifetime, plus 21 years), the ability to transfer funds between generations is enhanced without the perplexities of inheritance. It would be particularly useful to permit the fund to remain active until a grandparent's death, or even extend to the birth of the designated grandchild's 25th birthday. Like a trust fund, it could gather interest after the death of the owner, leaving the selection of heir to the last possible moment.

To return to the subject narrowly at hand, it is easy to see so many projects are made possible, you end up with an aggregate of goodies which eventually sink the lifeboat. Something must be chosen, something must be deferred, and the choice should be a delayed one, left to individual choice as much as possible. It can be commented in advance that retirement costs potentially dwarf sickness costs, and small single payments held at interest for long stretches have the greatest efficiency. There seems little choice but to constrain retirements to what the individual can manage independently, rather than permit retirements to absorb all the benefit of a new windfall. The theme is and should be, one step at a time.

Future Expansions.

How far these three short amendments would extend retirement solvency, is hard to predict into the future, but it would be considerable. Aside from any improvement never seeming like enough, it is almost impossible to guess the future timing of health costs, even when you can see them coming. But while the amendments might assure a comfortable future for Health and Retirement Savings Accounts, they do seem unlikely to address the full over-expectations of retirement. So the problem for many, many afternoons' deliberations, would be to expand the potential of HSAs until they become objectionable to competitive concerns. For that, I have four additional proposals which might work but inevitably collide with professions who would be quick to suggest narrower limits. Let's describe them, meanwhile waiting to assess objections from those they would discomfit:

1. A re-insurance scheme (insurance company to insurance company), called First and Last Years-of-Life Re-Insurance.This has already been described.2. Medicare should be modularized but without other basic change, so recipients need only buy pieces they need, using the invested proceeds for retirement. Obstetrical coverage immediately comes to mind. Sometime during the next fifty years, it can be predicted at least one of the five most expensive diseases (Alzheimer's, diabetes, cancer, psychosis, and Parkinsonism) will be inexpensively cured, once the initial cost increase is absorbed. We need a way to fine-tune the transfer of such medical savings into retirement income, understanding many competitors will hope to divert a windfall to themselves. Redirecting the Medicare withholding tax makes an easy way to channel the funding, as would reductions of Medicare premiums. Scientifically, Medicare is eventually destined to shrink as we find cures, but funding the resulting longevity must be given the first call on the savings.

3. The investment component of Health Savings Accounts should be dis-intermediated, partially if not completely.Ibbotson reports the stock market has produced--for a century--10%-11% long-term returns on large-cap stocks and less steadily, 4-5% on bonds, minus 3% inflation. You might not expect that judging from the returns investors often receive; investors are definitely absorbing most of the risk. The volatility is much less than most people imagine, and there is every reason to suppose Index funds of these entities should perform better with less volatility at far less cost, perhaps 0.1-0.3%. The days fast fade, when the public will continue to surrender the present level of stockmarket transfer costs and fees, which now sometimes erode investor return to as low as 1%. The fast-growing and simpler system is "passive" investing with index funds, and its goal should be an average return to the retail customer of at least 6.5% after inflation and costs. The struggle will be a fierce one, but the retail finance industry must re-examine who is at risk, and who are rewarded for taking that risk.

4. The center of medical care should migrate from medical centers toward shopping centers attached to retirement villages. Architects report it will always be cheaper to build horizontally than vertically. Since we seem destined to spend thirty years in retirement, and the principal occupation of retired people is taking care of their own medical needs -- the wrong people are doing the medical commuting. Teaching hospitals were located close to the poor, in order to use them for teaching material. But now "meds and eds" are fast becoming the principal occupations of high-rise cities. If there is ever a good time to place medical care closer to the patients, this is it.

The wrong people are doing medical commuting.

And if ever there is a way to put the doctor back in charge of medical care, decentralization is the way to do it smoothly. We will always need tertiary care, but we don't need indirect overhead, skyscraper construction, or multiple layers of overcompensated administration. Even continuing-education is becoming a revenue center. No one can claim the present centralization made things cheaper, and the disadvantages of medical silos certainly call the quality issue into question. The Supreme Court failed us in the Maricopa Decision; so let's see what Congress can do with reconciling the Sherman Act with the Hippocratic Oath.

The Nature of Ownership Relationships

It does seem appropriate to limit the actively managed portfolio of an HSA to health-related corporations, but it raises suspicions about motives. You want to stick with what you know, but you don't want to raise anti-trust concerns. There is a rather long history of medical organizations starting hospitals, drug stores and the like when there was no one else to do it. Eventually, however, competition did present itself along with arguments of conflict of interest, and rather forcefully. Since the purpose of this enlarged and actively managed portfolio would be to manage the shares rather than the business, it probably could be done if care were taken.

Furthermore, the range of businesses which would qualify as health-related is extremely varied. Over the past century, we have seen Medical Societies own malpractice insurance companies, medical journals, post-graduate educational tape recordings, health insurance companies, and hospitals and rehabilitation centers. Even more enticing are drug companies and medical device makers. Among all this variety could probably be found choices which avoid legal criticisms, but still serve the essential purpose of choosing superior investment vehicles. This is a vital central point, and we will return to it in later chapters. After all, members of almost any professional field would be likely to predict winners and losers in related industries with more accuracy than the public would, and therefore experience better performance in its choices. That would be particularly true when companies remain relatively small, unattractive to professional portfolio managers. And it's entirely different from buyer collusion to suppress producer prices of companies they control, but that distinction must be kept clear from the outset. Small companies grow, merge, and assume new characteristics over time, so a track record of selling profitable portfolio members who wander from original purposes, provides additional protection from this sort of suspicion.

At this early point of discussion, it should be recalled there is nothing magic about the level of interest rates, which in a general sense determine the returns of the stock market. Interest rates reflect the relative scarcity or abundance of money in the economy and are sometimes spoken of as the rental cost of money. Since governments control the supply of money, central banks tend to modify interest rates in order to stimulate or restrain the economy, as well as to reduce the cost of government borrowing. The consequence is a rather permanent inclination for interest rates to be held lower than they would be without government control, and a latent hostility of government to activities, such as this one, to derive a source of income from investment. The situation is further complicated by the increasingly important role of foreign governments, who sometimes make it difficult for the central bank to raise rates, even when it wants to. This oversimplification leads to the need for HSA managers to be measured by total return, not dividends, and common stock rather than bonds. Splendid returns can sometimes be produced at the time of reversals by doing otherwise, but can safely be shunned by maintaining a many-year horizon of complacency.

In all this potential complexity of starting an untried idea, it seems likely some laws must be changed. Not only must a selection be made of the most congenial legal environment (state or federal), but in the huge welter of existing regulation, it may well be the case that some existing law conflicts inadvertently, and a political argument must be made to adjust the blockade, or at least to make it clear no attempt was intended to circumvent the unintended awkwardness. We start with whether the various pieces of this approach might be combined into an umbrella corporation. The closest approach to such a corporation might be a whole-life insurance company, although we do not claim the similarity is perfect. It will require two chapters to cover this approach, one to examine the similarities, the other to devise solutions for the dissimilarities.

Whole-Life Revenue Model

Just to clarify the jargon, life insurance companies are of two types: one-year term of risk ("term insurance"), and whole-life term of risk ("whole-life insurance"). In this chapter, we use whole-life insurance as a model for the idea we have for health insurance, but there are many significant differences.

The premium is lower for term insurance because you buy it one-year-at a time, it expires if you don't renew it, but the premium may go up in subsequent years, and the insurance company makes most of its profit when people don't renew it. Most health insurance is run on a one-year term basis, rather inappropriately, because it protects against risk rather than to reimburse claim losses. As a matter of fact, a well-run term insurance company might never pay a claim, although it does happen. So in the long run, term is more expensive for healthcare than whole-life. In a whole-life policy, by contrast, the premium is level each year until you die. Because the subscriber of whole-life has contracted to pay the premium for many years, the insurance company is comfortable with making long-term investments, which pay them more for the float than short-term. Furthermore, the insuring company can enjoy long-term compound interest, which is eventually what makes whole-life coverage cheaper than term, assuming you are even allowed to keep renewing it.

In whole-life coverage, a whole lot of wheels are invisibly turning as premiums are paid yearly, your lifetime gets shorter but your life expectancy increases, new investments replace old ones. To ensure a margin of safety, premiums are higher than actuaries say is actually necessary, and yearly discounts are often (but not promised to be) paid back, or reinvested at more compound interest. Underneath all of this turmoil, the risk of your dying is gradually increasing, and a few people actually do die and collect benefits, terminating the policy. Life insurance is generally a state-regulated activity, and state taxes vary. There are special taxes for certain types of insurance, and there is a distinction between estate tax and inheritance tax. All of this and more are all taken care of for you by the company and is particularly suitable for children and infirm elderly. Just sign on the dotted line, pay the premiums, and wait to die. Simple.

As a matter of fact, the whole-life approach is more suitable for paying the constant nibbles of health insurance than it is for the single lifetime benefit of paying for a coffin, but the two businesses took different paths, long ago. If you simply wanted to set aside enough money for a funeral, you could buy an index fund, put the certificate into a lock-box, and direct your heirs to use it when the time comes. Although passive index-fund investing has made it possible for an individual to manage it all by himself, it's a nuisance and management gets particularly awkward for children and old folks. But that's not primarily why we began looking at other models; we're looking for somewhat higher returns than are currently offered. And that, in turn, is spurred by the realization that protracted retirement costs are just part of the costs of not getting sick. If you treat prolonged retirement as an inherent cost of health insurance, it's almost five times larger than the direct healthcare costs. Social Security was supposed to take care of it, but it simply cannot cope with such rapid increases. Are you supposed to starve to death? You can't keep working forever, your insurance doesn't cover it, and our whole economy was once based on the idea of dying at "three score and ten." But now the average person lives to be 84, soon to be 90, and we haven't even cured cancer yet. Making retirement cost an entitlement without funding it put the whole economy into a predicament with no ready answer, as soon as we started curing diseases.

So the Health Savings (and Retirement) Account was devised to be a Christmas Savings Fund for this need, but even HSA can't produce money out of thin air. So we now turn to professional investors, professional accountants, and others with sharp pencils, for help. Life insurance makes payments year by year for the final moment when you have to pay for your funeral. It was expanded to help support your widow. It's big and well spoken, housed in impressive big buildings. Maybe it can help by adding investment experience, computers, actuaries, and business degrees. Just a little extra efficiency would pay for a lot of extra administrative help; even half a percent extra for 90 years would make a big difference. And the sums involved are significant. Lifetime healthcare costs are estimated to average $300,000 per person. To add a generous retirement, would make it well over a million dollars -- per client. And please hurry up. Inflation is constantly making things worse.

As a matter of fact, judged from the outside, life insurance doesn't seem to be as frugal as it might be. Its marketing costs are high, and its investments are certainly conservative. Its executives are certainly well compensated. There would appear to be room for efficiencies. If health insurance adopted a whole-life approach for its revenue, it is not claiming too much to conjecture it would add 1% extra return to pay for retirement claims losses.

Whole-Life Disbursement Model

Although we intimated retirement funding vastly exceeds the rest of health funding as a problem, everyone in America is also aware that paying for health costs is a tangled, expensive mess. Far from simplifying matters, computers have forced us to stop to justify every step of the process. For a simple example, it would be a great comfort to know someone has seriously studied the details and can assure us the cost of examining claims generates more savings than its cost of doing it. No one doubts more cheating would occur if we paid claims without looking at them, but are we really confident the savings justify such a cost?

After all, the cheating is encouraged by passing it through a third-party, which makes it appear to be cost-free. Meanwhile, the Health Savings Account essentially pays claims with a debit card, relying on the depositor to howl when the charge seems unwarranted. Most managers of HSA would rebel at imposing extra claims processing costs onto a system which keeps customers quiet with a 30% reduction in overall costs. The vast majority of personal expenditures are paid directly by a two-party transaction. Are we really so concerned about chiseling we wish to impose a third-party system on the whole retail economy? Put it another way. Is there something so especially evil about healthcare costs which forces us to single its transactions out for the undeniable costs of claims processing? The problem, dearest friends, is not whether claims processing costs so much. The real problem is why in the world do we use a third-party system to pay for them.

The Health Savings Account asked that question three decades ago and lets the customer be his own policeman with his own money, so long as the amount is less than the deductible. It really is necessary to have insurance to spread the risk of health catastrophes, and so catastrophic health insurance is the cheapest form of it. It happens a reasonably high deductible and the minimum cost of a hospital admission are pretty much the same, so third-party reimbursement is pretty much a hospital problem. There's not much difference in cost between one breakfast and another, so I would interject the comment the hospital problem boils down to the accounting fiction of indirect overhead. Every single hospital expenditure must be assigned to reimbursement, so by calling it indirect overhead it gets paid for by someone, no matter who, and "costs" go up, employees get raises, equipment gets purchased. Just call in ten CPAs drawn from the phone book, and ask them to establish a justification system for any item to be included as indirect overhead. If that doesn't solve your problem, you don't have a problem and might as well stop complaining about it.

So to return to the whole-life model, it seems reasonable to include the Health Savings Account as a model for expenditures. It might be reasonable to impose some standards for catastrophic high-deductible insurance compliance, with the indirect overhead approach as a default option in cases of dubious performance. Otherwise, cost overruns can be restrained by dropping insurance company participation where suspicions are warranted.

Design of the insurance approach is thus fairly simple, leaving energy left over for designing incentives and efficiencies, which we would hope would collectively generate another one percent investment return or its equivalent. Together with the one percent picked up with revenue efficiency, the additional 2% return on investment income might be going far enough. As I see it, we still haven't got to the crux of the matter, however. It's to generate sufficient profit and reserves to carry the system several decades through the transition to full implementation. Unfortunately, everybody wasn't born on the same day, and won't have the same personal reserves. Either we implement this system in stages, or we find some massive funding mechanism to carry it through the rough spots. It isn't adequate to dump the transition problem on the Congressional staff and go on to unrelated matters; this is the make or break issue. Even at the best, it will take several decades to be fully implemented, satisfactorily running, and solvent. So even if we do it this way, it will displease many people, unless--. Unless the scientists soon find an inexpensive cure for two or three major diseases.

So let's look at several pieces of the financing puzzle which might be included within the main structure, or they might remain independent. The choice must save money, however, or it won't serve the purpose.

REPLICATED COPY of Introduction to the Components of the Problem 07/13/16 11:44 pm

The book before you is not a list of dooms and glooms. It is a proposal to protect a functioning society by regarding child, parent, and grandparent as different stages of the same person's life, with a united interest in the same goal. Specifically, we build upon the idea of a Health Savings Account, one account per person throughout one lifetime, as a financial way to emphasize an underlying social point. If you spend too much too early, you won't have much left for later.

This unification proposal is voluntary, you don't have to do it, or even part of it, but in some ways, that's another advantage. Without the ability to refuse, the only remaining protection is the sympathy of more fortunate people. Sympathy lasts longer if everyone appears to have done his level best--for himself, and with plenty of warning if that wasn't sufficient. There is no escaping the use of insurance for unexpected catastrophes, but insurance is formalized dependence on strangers. Only an insurance salesman would argue for unlimited insurance for everyone, all the time. Only someone who knows very little about insurance would believe insurance is a way of printing money. Voluntary, by contrast, isn't a one-size-fits-all commitment and doesn't dump 340 million subscribers on untested systems, all at once. Voluntary respects your right to say No.

Either voluntary or mandatory, however, some things are just part of life. The working generation must always subsidize the dependent generations, but it could be the same individual at different ages instead of by classes of strangers. For a final twist, we unexpectedly propose to empower solution by adding a second problem we didn't even realize we had, until recently. It isn't a trick; everything looks in retrospect as though it might have been predicted.

The cost of third-party systems can be found by subtracting the difference between the costs of two approaches, first-dollar, and high-deductible.

|

Three Surprises. Curiously, the Health Savings Account had to be tested before it could be fully understood even by its originators. A bit of history may help explain it. The basic concept of Health Savings Accounts was developed in 1981 by John McClaury and me, while John was Senior Policy Advisor in the Reagan White House. Derived from the IRA concept developed by Senator Bill Roth of Delaware, it started as a Christmas Savings Account, to save up for the deductible of a (high-deductible) Catastrophic health insurance. So there were two linked features: high-deductible health insurance, and a medical version of an IRA. After testing, the realization dawned that the real deductible became the unpaid portion in the account, eventually becoming zero -- because now the (linked but separate) insurance premium no longer rose as the real deductible declined. Eventually, the HSA emerged looking like first-dollar coverage for the same price as insurance with a high-deductible. Saving the deductible was placed within your own hands without shifting the burden onto an insurance company. The undue cost of first-dollar coverage was reduced, again, by shifting its point of impact.For the purposes of this book, the strength of that last incentive was its most important feature. Almost anybody could tell at a glance that the cost of Medicare was what stopped "single payer" in its tracks, what paralyzed Congress on healthcare, and what defied solutions from any direction. Medicare was the "third rail" of politics -- touch it and you are dead. But with a new retirement entitlement looming which almost made Medicare costs laughable, it was a new ball game. In the new environment, third-party reimbursement was itself standing in the road of lowering everybody's costs through rearranging the payment stream. Medicare became a symbol of what the problem was, not just a lobbying benefit. Increased retirement cost was, in short, a central cost of health care, and anyone who stood in the way of fixing it was misguided. Because it is closest to retirement, Medicare is in fact the first thing you must change, but you better do it very carefully. And by the way, you better do it pretty soon.A different enlargement of that point emerged from the tendency of non-insurance HSA managers to use debit cards for medical payments, instead of claims forms. Although there may well be more temptation to chisel in the absence of strict scrutiny, the debit-card system essentially depends on the client to howl if he suspects his own money is being mis-spent. Otherwise, it will be lost. When you spend a third party's money, there's far less concern than when you spend your own. The relative disappearance of chiseling cost was tangibly high-lighting the true cost (and lack of effectiveness), of third-party policing. Since it was more costly to police than not to police, it exposed a second hidden cost of using third parties -- at all.

That was the first surprise, but a more gratifying development was an appreciable decline in medical costs, in spite of reducing cost-reduction efforts. At first, this saving was attributed to the ("adverse") selection of unusually frugal clients. In time, the real incentive emerged: the provisions of the HSA act permitted any surplus at age 65 to be turned into an IRA. That is, an incentive had been created to save health money for retirement, substituting personal responsibility for insurance company vigilance. And the hidden cost of using a third-party system was similarly approximated by the resulting difference between the two costs.

But a third zinger in the system took longer to emerge. What was mainly motivating subscribers to be stingy and vigilant was the provision in the enabling law that when the owner reached Medicare age, the Health Savings Account turned into an IRA, Bill Roth's Individual Retirement Account. The name itself suggested motivation. As improved health care spread among the elderly, they lived longer. Gradually and grudgingly, it was recognized that extended longevity was a hidden cost of Medicare. There was Social Security, of course, left in the dust of thirty extra years of longevity since 1900. It destroyed defined-benefit insurance. It might have satisfied Bismarck, but it was essentially negligible in the face of longevity -- which eventually proved to be five times as expensive as the rest of health care. What's worse, its cost is even harder to approximate than the future cost of health care, because everyone has his own definition of a "decent" retirement. Underfunded retirement is a stronger incentive to watch your pennies than a specified one because there is no one, not even that demonized one percent, who can be certain there will be enough left to last his lifetime. Wasn't that enough incentive to get anybody's attention?

------------------------------ This study of Health Savings (and Retirement) Accounts was begun thirty years ago, with intensity in the past five years. During most of that time, it was paying for health costs which were the central concern. Paying a big chunk of health costs would be an achievement, paying for it all would be an impossible dream. Therefore, paying for the whole healthcare system was the earlier goal of my proposals. If it fell short, well, it paid for a big part of it. Either way, we could afford to leave Medicare alone. But once Medicare came into focus as the main impediment to solving an even bigger problem for exactly the same age group, "saving" it becomes a relatively small issue. New revenue must be found, the quality of care must not be injured, and -- most of all -- public opinion must be re-directed. This is a specialist's game, but the public is now the real player.

Resource Assessment. Adding up all the other economies of Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts, but now also including the retirement costs, the conclusion is left that HRSAs might pay for health costs, and some but not all retirement costs. Much of the shortfall comes from difficulty stating a "decent" retirement payment which would satisfy most people. That's enough for a Trappist monk is not enough for a movie star, and what will be called decent in 60 years is pretty hard to say. So the most we should promise is healthcare plus some retirement; supplement more generous retirement as you are able. Even promising that much is a stretch, but is certainly superior to healthcare plans without the discipline of individual ownership. Unfortunately, it forces the individual to some choices he must make for himself, versus allowing some big anonymous corporation to do it all for him at a hefty markup. Let's specify the two big dangers he must navigate:

Imperfect Agents Theoretically, the best result anyone could provide would be to give a newborn baby a couple of hundred dollars at birth, let a big corporation do the investing, and pay a million dollars worth of bills over the next ninety years on his behalf, at no charge. The long investing period would provide some astonishing returns, and it would be entirely carefree for the customer.After Assessing Obstacles Comes Strategy. Most HSAs make payments with a debit card suitable for passive investing (utilizing total market index funds) for inexperienced investors and for otherwise undesignated accounts. However, there's a technical problem: the earning period is not the first stage of life; it's the second, following nearly a third of life in childhood and educational dependency or debt. Health expenses in the childhood third of lifespan may be comparatively small, but the earning capacity is essentially zero. This unconquerable fact leads to splitting investment considerations into three stages, the first and last thirds subsidized by the middle one. The result is, two systems feeding off the middle third in opposite ways, requiring opposite approaches. Somehow, it must all come out in balance at the end. And remember, it starts with a deficit in the obstetrical delivery room unless we re-arrange something else.Unfortunately, experience over thousands of years has demonstrated agents will eventually extract much of the profit for themselves. Countless kings have been known to shave the edges of gold coins, even more, have been found to have employed inflation of the currency to pay their own bills. Investment managers are almost invariably well compensated, usually for mediocre returns. William Penn, the largest private landholder in history, was put in debtors prison by his wayward agent, as was Robert Morris, the financier of the American Revolution. Whole-life insurance companies are the closest approximation of an agent for a Health Savings Account who might propose to get paid a level premium for decades before paying out a benefit for a dead client. They seem to survive by promising a single defined fixed-dollar benefit and counting on inflation to work for them as it does for dictators, overseen by an insurance commissioner. Unfortunately, they have the moral hazard of falling back on other surviving firms to bail out bankruptcy, and the political hazard of trying to force premiums downward for the taxpayer without any reliable benchmark. Just how much they have been rescued by lengthened longevity is something only an actuary knows. Long ago, the situation was summarized by the question, "And where are the customers' yachts?"

Inexperienced Solo Management. If Warren Buffett had an HSA, he would have no problem managing it, and neither would a great many other savvy folks. The problem is to make the management so simple and standard that expenses can be kept low without injuring investment returns, for the average citizen. This consideration almost drives the conclusion the lifetime would be best divided into at least three component parts, with benchmarks and averages published regularly, since the medical and beneficiary problems divide into the same three (childhood, working age, and retirement) components. It begins to look as though a new profession of fee-for-service advisors needs to become educated and distribute themselves widely, perhaps in local bank branches. As will be described in later sections, the need is for the income stream to be kept in balance with the probable expenditures, adjusted for inflation or deflation. It is not to achieve the maximum possible revenue return, regardless of risk. That is to say, the purpose of the HRSA is not to make as much money as possible, but to be sure as much medical need as possible can be satisfied by the revenue available. Let's put it all in a nutshell: There's a big difference between designing a system to cover a public need inexpensively -- and designing a business model to make a profit. But that's not nearly as big a problem, as doing both at the same time.

If you spend too much too early, you won't have anything left for later.

| ||||||||||

|

New blog 2016-07-13 17:16:09 contents

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The initial reaction was to treat workers and retirees as two different classes of people, relying on one to tax the other, ignoring any restlessness about the cost of paying for someone else. But retirees now move to different communities, even different states, almost sorting into two different nations. Furthermore, the gap gets wider, with good health leading to longer retirements. Government is forced to be the paymaster for an expanding free lunch for strangers. become entitled to tax their parents for health and education, for longer stretches of increasing alienation. Give things a little time, however, and it's possible to anticipate this additional third of the population feels entitled to tax the working third, deploying the enforcement powers of the government intermediary. Between them, the non-working two thirds will constitute a majority, so even politics may not forestall the problem. To earn more requires more education. To work more should entitle a peaceful retirement. Somewhere, we got on this wrong path for the right reasons. If the present system could be disentangled without destroying it, the potential exists to earn money before the funds are needed and spend them later. The PThe initial reaction was to treat workers and retirees as two different classes of people, relying on one to tax the other, ignoring any restlessness about the cost of paying for someone else. But retirees now move to different communities, even different states, almost sorting into two different nations. Furthermore, the gap gets wider, with good health leading to longer retirements. Government is forced to be the paymaster for an expanding free lunch for strangers. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- REPLICATED COPY of Prologue: New Incentives 07/13/16 11:35 pmOverview. To be brief about it, health spending now crowds toward the end of life, with most heavy spending after age 65, but most earning power comes before 65. Disregarding the complicated history of how we got there, we are borrowing to pay for Medicare, but not earning market interest on the idle money collected from younger people. Potentially, the two age groups could unify their finances and get more or less dual savings. That's the dream advanced by the single-payer advocates, but on examination, the cost, politics, and complexities prove too overwhelming for that approach. It would be a mess, and nothing else could be accomplished by the government for decades to come. It is our contention the use of Health Savings Accounts as a transfer vehicle would be much easier than unifying insurance programs, solving most of the problems, avoiding most of the obstacles. But that's only part of the health financing problem. At the opposite front end of life, children concentrate medical expenses toward their first day of life but have absolutely no way to pre-pay the expenses from their own income. They might add thirty years to the compound interest in Health Savings Accounts if they only had some money. Thus if you aspire to serve lifetime financing, you seemingly require two clashing systems, roughly the opposite of each other, at the beginning and end of life. Not to mention the working class in the middle, largely funded by employers who frequently change. Those people who largely support the whole system, have such constraints on their financing it is probably not feasible even to discuss unifying them for decades into the future. Connecting, yes; unifying, as little as possible, Therefore, this book passes over single payer and concentrates on lower-hanging fruit. Essentially, this book proposes the Health Savings Account as a unifying financial bridge between programs, one account per individual lifetime, serving many disparate programs. It is designed to be implemented in pieces and designed to be phased in. The reader will probably be surprised at how simple some things are likely to be, once it is conceded the patient ought to be in charge of what others are now deciding for him. Prepare yourself for one big rearrangement of thinking, however. Extended retirement costs are a direct consequence of superior healthcare. They are five times as expensive as healthcare itself, and can only conceivably be partly paid for, with money saved from the rest of the healthcare budget. But eventually, new revenues must be found. It's a devastating realization, but it contains the seed of solving the problem. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The initial reaction was to treat workers and retirees as two different classes of people, relying on one to tax the other, ignoring any restlessness about the cost of paying for someone else. But retirees now move to different communities, even different states, almost sorting into two different nations. Furthermore, the gap gets wider, with good health leading to longer retirements. Government is forced to be the paymaster for an expanding free lunch for strangers. become entitled to tax their parents for health and education, for longer stretches of increasing alienation. Give things a little time, however, and it's possible to anticipate this additional third of the population feels entitled to tax the working third, deploying the enforcement powers of the government intermediary. Between them, the non-working two thirds will constitute a majority, so even politics may not forestall the problem. To earn more requires more education. To work more should entitle a peaceful retirement. Somewhere, we got on this wrong path for the right reasons. If the present system could be disentangled without destroying it, the potential exists to earn money before the funds are needed and spend them later. The PThe initial reaction was to treat workers and retirees as two different classes of people, relying on one to tax the other, ignoring any restlessness about the cost of paying for someone else. But retirees now move to different communities, even different states, almost sorting into two different nations. Furthermore, the gap gets wider, with good health leading to longer retirements. Government is forced to be the paymaster for an expanding free lunch for strangers. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- The book before you is not a list of dooms and glooms. It is a proposal to protect a functioning society by regarding child, parent, and grandparent as different stages of the same person's life, all with a united interest in preserving the system. Specifically, we build upon the idea of a Health Savings Account, one account per person throughout one lifetime, as a financial way to illustrate a social point. If you spend too much too early, you won't have much left for later. This proposal is voluntary, you don't have to do it, but in some ways, that's another advantage. No matter what system is used, ultimate protection lies in the sympathy of more fortunate people. Sympathy will last longer if everyone appears to have done his level best--for himself, and with plenty of warning if it wasn't sufficient. Ultimately, there is no escaping the use of insurance for unexpected catastrophes, but that's the last resort. Only an insurance salesman would argue for unlimited insurance for everyone, all the time. And only someone who knows very little about insurance would believe insurance is a form of printing money. Voluntary isn't one-size fits all. Voluntary doesn't dump 340 million subscribers on an untested system, all at one time. Either voluntary or mandatory, the consequences of our present dangerous path eventually fall on the individual, leaving nothing but the unlimited (?) sympathy of others for protection. The working generation must always subsidize the two dependent generations, but it's the individual at different ages instead of as anonymous classes of strangers. For a final twist, we propose to address this problem by adding the incentive of a second problem we didn't even have until a few years ago. It isn't a trick; everything looks in retrospect as if it could have been predicted.