3 Volumes

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

Surmounting Health Costs to Retire: Health (and Retirement) Savings Accounts

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

Healthcare Reform:Saving For a Rainy Day

Lifetime Health Savings Accounts

Front Stuff, Health Savings Accounts: Planning for Prosperity;SECTION ONE: HSA and its Competitor, in brief

...Also by the same author:

The Hospital That Ate Chicago, Saunders Press, 1980

Health Savings Accounts: A Handbook, Ross & Perry, Inc. 2015 (Forthcoming)

---------------------------------

Ross & Perry Book Publishers

3 South Haddon Avenue

Haddonfield, New Jersey 08033

856-427-6135

----------------------------------

Copyright: 1-2540412791

ISBN #: 978-1-931839-44-0

-----------------------------------

Acknowledgements

For advice and support about the thrust of this book, I owe spiritual debts to John McClaughry of Vermont, the late F. Michael Smith, Jr. of Louisiana, and the late Bill Niskanen of Minnesota and Washington, DC. It's heartening to remember strong support coming from wide corners of America, and from strata of society ranging from a country doctor to the former Chairman of the President's Council of Economic Advisors. All three of these men worked their way up to being either a candidate for Governor of his state, the President of his State Medical Society, or the Chairman of a famous Washington think-tank. All three brushed aside the problems they created for themselves by constantly thinking outside of the box. My fellow Philadelphian John Bogle, whom I have only fleetingly met twice, deserves a lot of credit for demonstrating in his books how to invent a complicated concept, and then simplify it for outsiders. I've adopted his investing strategy.

And for personal support and tolerance from my family editorial board, consisting of my two sons and two daughters. My son George took time out from climbing the tallest mountains in the world, to develop a computer algorithm that instantly created the answers to a multitude of math problems hidden in certain assertions I blithely make, but now have confidence in. Likewise, my CPA daughter, Miriam told me some things which may be commonplace among corporate Chief Financial Officers, but astonish the rest of us. And her siblings Stuart and Margaret, who understood my tendency to wise-crack, but having long practice with its consequences, talked me out of most of it. Especially Margaret, who persuaded me it was more important for the title to be accurate than to be witty.

CHAPTER ONE: Re-Examining the Revenue Premises of Medicare

Chapter One:

We propose a comprehensive reform of American healthcare finances, resulting in a drastic drop in costs. This is payment reform, not medical reform, although the practice of Medicine cannot escape upheavals in its finances. It must all withstand critical review, but some of the future is simply not knowable. Defense of future predictions relies on extrapolations of history, but brief explanation nevertheless forces some things out of chronological order. We must, however, begin somewhere, repeating ourselves a little when the loop is finally closed.

So, we begin with Medicare, which has worked well for fifty years. Its data are easily confirmed on the Internet. Costs are known, minor faults have had time to be been corrected. Medicare is not the central focus of this book, but it's familiar. Seeing where Medicare fits in, gets the reader a long way toward understanding the system and where it needs to be modified.

Begin understanding Medicare with how it gets paid for, in three parts. (1) About a quarter is pre-paid, originating as a payroll deduction from the paycheck of every working person and mostly matched by an equal amount from his employer. (2) A second 25% of Medicare expenditure is supplied by the retirees themselves, as various sorts of insurance premiums. (3) And the remaining half is contributed by the federal government, but it originates in everybody's graduated income tax. In recent years, national finances have been strained, so a considerable part of the subsidized half is "temporarily" borrowed from foreign countries. There is general approval of the Medicare program, but it has grown expensive, a crisis usually blamed on the approaching retirement of the baby boomer generation. In a sense, maybe Medicare is a little too popular. Everybody likes a dollar that seems to cost fifty cents.

Focus attention on the pre-paid quarter of the costs, the payroll deduction. It's to be found in a mass of other numbers on any paycheck stub, often mixed with pre-payment of Social Security, and consists of 1.45% of salary for most people, 3.8% for those who earn more than $200,000 a year. The average worker earns $42,000 per year, and thus contributes $630; half of the workers contribute less, half of them, more. Persons earning less than $200,000 are matched by equal contributions from their employer. This has been going on for so long, most people could not guess how much it costs, would overestimate the proportion of their contribution, and underestimate its full cost.

In our proposal, we ask that $360 (of this average of $609), a dollar a day per working person, be set aside in an untouchable "escrow" fund every year, $180 from the beneficiary, $180 from the employer. Essentially, that's a seventh (14%) of the matched average $1218 pre-payment already being made on behalf of the average worker, although it might constitute all of his personal pre-payment if that worker only earned $5,000 a year. (It's a flat tax, but it does not go to zero at zero income.) In forty years of working life, the escrow would total $14,400. (It currently becomes the government's money, so the transaction is a tax reduction as well as an increase in personal income. For the moment, let's skip over the people below the poverty line, who obviously have to be subsidized, and ask, "What do you propose to do with a seventh of a quarter (3.6%) of the average total cost of Medicare coverage?" We're asking for $14,400 spread over forty years, which is 7% of what a person costs for a lifetime of Medicare ($200,000), or 4.5% of what is generally guessed to be one person's health cost for an entire lifetime ($325,000). What are we proposing to do with the money?

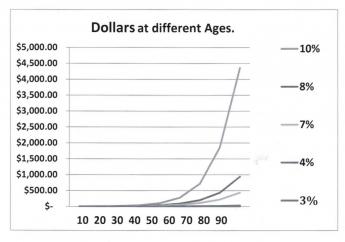

Answer: We propose to invest the $14,800 at 8%, and offer one choice about some of it on the individual's 65th birthday, as well as a second choice about it at any time thereafter, including his will. Because we plan to earn 8% interest on it, the $14,800 has turned into $93,260, and by the way, $7400 of the $14,800 was probably contributed by the employer, who got at least $3700 in a tax deduction for it. Furthermore, most economists agree employer contributions effectively reduce the paycheck by an equivalent amount, describing all fringe benefits as just part of employee costs. We will unravel this later, but the point right now is illustrating the largely unappreciated power of compound interest. This little exercise was conjured up to illustrate the power of compound interest, which it does quite nicely; but we aren't quite through. A dollar a day has resulted in 93,260 by age 65, but by age 83 (the present life expectancy) the 93,260 has turned into $360,000, just by sitting in Medicare unused, and $360,000 is the generally accepted figure for the total lifetime healthcare cost of an individual. One conjecture is 8% interest is too high, but we devote a whole later chapter to defending that number, which is merely the highest that can readily be defended.

Remember, however, this gain. equal to Medicare's total cost was achieved by investing only $360 of the $609 actually paid in salary withholding for Medicare. There is another $249 paid to the Medicare "trust fund". At 8%, this has reached $64,505 by the 65th birthday and grows by $6054 a year until age 70. Medicare averages $11,000 a year costs until age 83, the expected age at death. If the second fund makes up the $5946 difference. The two funds are in the position of earning 8% and shrinking at a total of $11,000 per year in combination. By the age of xx, the escrowed fund is growing at more than $11,000 a year, and the surplus fund is shrinking to make up the difference between $11,000 a year and the deficits of the escrow fund. Once the escrow fund is earning more than $11,000, there is a growing surplus which at present would transfer to an IRA.

Well, obviously no one is actually going to do what's suggested in the example, at least not more than once, but it does bring out some important points. The first is that apparently Medicare could be privatized for about one-quarter of what it is now costing, just by depositing and investing what is already collected in payroll deductions. Is it really possible we could also stop collecting Medicare premiums from the beneficiaries entirely, and stop accepting its 50% federal tax subsidy entirely, which we must now borrow from foreigners? Well, sort of. It would all depend on whether you could get 8% from Wall Street, as well as an income tax deduction from the IRS. Since the government doesn't pay itself taxes, the comparison boils down to whether you can get that 8%. A later chapter is devoted to the question.

Data has not been collected to test this idea directly, but some suggestions are intriguing. Medicare reports it spends about $11,000 per year per Medicare subscriber, whose average life expectancy is to age 83. That would imply Medicare is now costing about $200,000 per subscriber per lifetime. Future longevity is unknowable in advance, but it seems plausible it will level off at 93, sometime this century. One way of looking at this is to multiply $11,000 per year, times 27 years instead of 17, and get a future total lifetime Medicare average cost of $352,000. That's quite a wallop, but revenue from compound interest of 8% would be paid longer as well, taking it from $198,000 to $726,000. Old people getting cheaper is quite a surprise. Among the various things suggested is we have no idea how much 2035 technology would cost if it's good enough to extend longevity by ten years. Take a cure for cancer, for example. Would it be $100,000 per treatment, or would it be like aspirin, just lying around waiting to be discovered lowering heart attacks by 50%, at a nickel a pill? Or take another direction: perhaps living ten years longer would result in ten more years on the golf course or bridge table, followed then by the same terminal illness. An unchanged lifetime medical cost, in other words, just spread out over a longer time. Like a tulip on a longer stem. Since we obviously don't have the faintest idea about these projections, we will just have to strike an average, and hope for the best. But to return to a deeper question latent in the discussion: Do we have to worry that living on investment income will reach a point where it can't maintain a decent living in the face of improving technology? The encouraging answer seems to be: There's nothing on the horizon to suggest it.

Choices at age 65 have therefore become more complicated. If you had already reached your 66th birthday, and your choices included taking the $180,000 in cash, of course, you can just take the money and run. You might well be required to pay income tax on the lump sum, reducing its net amount by 15-30%, depending on your tax bracket. Perhaps a better choice has already been created, to roll it over into an IRA. In that case, the tax is deferred until you take minimum distributions for retirement purposes, which start paying a gross taxable amount (calculated by dividing it by your life expectancy, which at 66 is currently 17 years) of $10,500 per year. Considering this the return on an original $7400 cash investment, that's pretty substantial. And even recognizing your employer contributed half of it, it's still pretty good.

But consider another direction, entirely. Suppose by then the laws have been liberalized to allow "grandparents" to transfer a certain limited amount (see below) from their own Health Savings Account into a child's newly-created unique Health Savings Account if the recipient child is any age less than 35. At "grandpa's" death, again if the laws then permit it, the amount (specified below) may be transferred to other accounts. In the past, a child's account would have had more than three doubling opportunities in a 26-year span, but an infant baby has no money to double, and occasionally no way to create an account.

Whereas under our proposed new hypothetical rules, the baby's HSA might contain $8,000 at age 26, if grandpa transfers $1000 at birth and nothing else is spent out of the account until the child is 26, as a hypothetical illustration. The proposal is made that special Catastrophic insurance is also needed for this situation. Nevertheless, the potential should be exploited to create a bridge which connects an age group which is often overfunded with a generation that is usually underfunded, and always incapable of managing its own financial affairs. The extra $8000 at that particular moment in a 90-year cycle would have an immense effect on the cost of the entire scheme at all ages. So immense, in fact, that it undoubtedly would require safeguards against creating a nation of perpetuities in a few generations. My own suggestion is that a surplus from inherited sources should reach its conclusion at age 35, after which any surplus from "grandpa" sources should be transferred to the U.S. Treasury, subject to appeal to the local Orphan's Court. With such a rule in place, the system would readjust its arithmetic in the great majority of cases to accommodate special circumstances. The compound investment income alone will start this cycle all over again, if it throws off $325 a year for, say, the last ten years, including consuming its principal to do so. To repeat, an estimated $6000 of the eventual $8000 is consumed by the process of paying for the baby's birth and pediatric expense, with perhaps $2000 used to fund the child's own HSA up to $3250 at age 36, getting consumed in the process. Since this hypothetical began with only $1000, the starting amount could easily be tripled without disturbing the conclusion. With actual experience, these estimates can be fine-tuned. Tax-exempt funds like this should probably not be permitted to become perpetual, but allowing them to extend to a grandchild's 35th birthday would provide very desirable bridge funding for a period of life from birth to 36, which is both medically and financially quite vulnerable, and hence requires real-life insurance data (i.e. not hospital charges). He's going to have to go out and earn a living to sustain his own health insurance (see below), but his retirement Medicare costs are already a third paid up.

Just imagine: such a scheme might encourage more women to have children at an earlier age, which would be biologically very desirable, poorer people would be able to go to college without health financing concerns, and probably with reduction of the burden of disease from untreated medical conditions. At the same time, money would remain available for grandpa's health because he got to it first. Invisibly in the background, it assures generosity in the disability costs of the increasing volume of elderly indigents, which have been widely viewed with apprehension. And although all such benefits would entail some costs, at least they could not break the national fisc, within this financing design.

Other choices for the use of this "found" money are suggested in later chapters, and still, others are readily imagined, including perhaps some undesirable ones. At this point in the narrative, we will break off in order to heighten attention to the central feature of this health "reform", perhaps better described as reformulation. The central feature of this reformulation, is to exploit the sociological changes in healthcare created by advances in science: a much longer life expectancy, with an initial period of low health expenses, followed by a shift of burdensome illness toward its far end. Such change in lifestyle is ideal for gathering compound income early in life, augmenting it while it remains idle, and spending it toward the end. Since the reformulation pushes money toward an uncertain end, it inevitably creates some surpluses, which can best be recycled to assist the difficult costs of some relative's young life that, in the larger view, are quite modest.

So far, we have only looked at reformulation as a way to generate revenue. Another proposal to choose as an alternative is to drop Medicare, and simply pay medical bills out of the health savings account plus fail-safe catastrophic coverage. While at the moment few would have the courage to make such a switch, a credible threat to do so would at least perform the public service of discouraging mission creep, cannibalism by other agencies, and/or administrative bloat. It will always be impossible to determine how much of the present cost overrun was avoidable, but it's a fact, and a source of restlessness. Its best preventative is some viable competition.

Viable competition would include both luxury care for those willing to pay extra, and bare-bones care for those who cannot afford the standard variety. Both these desirable competitors would require some mechanism for extracting a fair financial equivalent from the standard product's expense account, and transferring it to the competitive systems. Needless to say, the existing system would resist, but a proposal might additionally be devised to resolve state/federal Constitutional problems in parallel with the money.

The Constitution's Tenth Amendment is decisively opposed to any centralized national healthcare system so this issue will continue to arise. To drive a not-so-subtle point home, it is only fair to conclude that many perhaps most citizens would prefer to impair employer-based health insurance -- if the only alternative offered, is to impair the Constitution. To state the matter in a conciliatory manner, there exists a widespread consensus not even to speak critically about the Constitution, unless a sincere bipartisan effort has first been conducted, trying to work around a problem. We tried the nullification alternative in 1860, and the results proved discouraging.

So, I propose we have at least two state-based healthcare systems, and eventually, a third national system exclusively limited to interstate issues, conflicts between jurisdictions, etc. That's what the Constitution wanted, and until we give it a chance, the state/federal uproar will be recurrent. It appeals to me to envision a hospital-based system and a retirement-village-based system, taking care to restrain medical schools, the federal government, or major employers from dominating either one. That gives state governments a chance to dominate locally, but the condition of state governments makes it unlikely that more than a handful would be up to the task. Governors, possibly, but legislatures, not so likely. A unique obstacle is to discover many sparsely settled states do not have the actuarial numbers necessary to support more than one health insurance company.

And so, since big changes are expensive, we need to find some extra money. As the reader will see, I believe Medicare could be paid for by reformulation at a fraction of its present cost, with a compound income of about 8%. The precise fraction and its compound income can be juggled around, but it looks achievable. If finances are tight, and 8% is unachievable, perhaps the Federal government could supply block grants which would support 8%, just as an example. However, any such expedient is a stunt that can probably only fail once, so we better study it hard. But if it can be done with Medicare, the pattern can be repeated with other age groups.

Finally, there really is a scientific end in sight, to a problem which science largely created. Just find an inexpensive cure for five or six diseases, and the main problem which will loom is spending too much money on non-serious complaints, cosmetic enhancements, and flummery. It may surely come to that in another fifty years.

Because of the extent and complexity of the problems, this first chapter only states the premises and gives a few examples; later chapters will explore more details needed to understand certain poorly understood features. But if there is doubt about the goal, let's make an explicit statement of it. We have been convulsed by health care reform since at least the time of President Theodore Roosevelt, but every ten years it keeps coming back. Let's stop thinking small and start thinking big. Let's fix it right and get on with it.

Children, 0-26

Everyone agrees there is a tangle about the rights and responsibilities which begin when childhood begins. We wish to avoid this issue as much as we can, but partitioning the costs of the average child requires stating some point or other, as its beginning.Keeping the practicalities of paying for it in mind, we hope no one will object if we say childhood begins, the day you are born.

We next consider the healthcare costs of children, from birth until age 25, linked with the costs of the elderly, for a reason. One of the points made in this book as an arguable alternative to the present employer-based system is to keep it within your family, rather than tax other people as a class. However, although the system now claims to begin with the first full-time employment, a newborn provokes about $18,000 of medical expense including obstetrics before that, right from the beginning, before the child can even feed him or her self. Age 26 might be a reasonable place to begin self-support, not because of tax deduction, but since that's typically the age group with the lowest health costs. Even that starting age has its problems because the parents are not much more accustomed to managing finances than the child is. The central question remains the same. Who is to supply the $18,000?

The Progressive movement started the idea of "family plans" about a century ago, but Henry J. Kaiser is credited with noticing an employer's gift of the insurance would supply two tax deductions, the employer's and the employee's, during World War II. That "reduced" the cost of health insurance by at least 50% (for the employer and employee), but it made a married employee seem more expensive than unmarried ones, made healthcare seem a free cost to the recipients and therefore boosted its cost, introduced a religious note by discouraging multiple pregnancies, and was unfair to unemployed or self-employed persons who were excluded from getting the gift. It is impossible to determine how much this new twist distorted employment and medical prices, but by suspicion the unfairness was major. It surely prompted a response, and this is one. If a big business can get tax deductions for giving away healthcare, why can't everyone else?

So it is proposed -- hold your breath -- HSAs give the equivalent of $18,000 at the death of an older relative, to a newborn's HSA at birth. The average childbearing mother has 2.1 children, which works out to one grandchild per grandparent, and helps smooth out the cost of multiple children. Because births and deaths cannot be forced to coincide, some sort of fund has to be created to make all this come out fairly, but the result should equal a zero balance between two generations. And because everyone who is alive has somehow already paid his birth cost, there is less urgency to begin this feature at the onset of the program--it becomes a feature of the transition. And, going back to the pros and cons of including Medicare premiums in the compounding, the more surplus is generated, the shorter the transition period should become. Ultimately, of course, the cost of health insurance for the mother is reduced; but the main beneficiary of the transfer is whoever is now paying for the mother's health insurance. That would sometimes be the father, sometimes the employer, and sometimes the Affordable Care insurance.

A few children are cursed with horrendous medical bills, which quite often predict lifetime disabilities. For the most part, however, childhood medical costs are pretty small. It would seem to produce an < b>ideal configuration for insurance, leading to mostly small premiums, affording a lot of protection against a fearful risk which is nevertheless relatively uncommon. However, a newborn is unable to walk, talk or feed him or her self, beyond even mentioning his or her lack of savings. Parents are now expected to pay such bills, and when they are very large it is common for grandparents to help out. So it sort of fits the common situation to group the two dependent periods of life (childhood and old age) together, as a continuous loop skirting the income-producing period of life entirely. The underlying purpose is to shift overfunded money to an underfunded time, compensating the childhood cohort for the fact that compound interest appreciates very little during childhood, but very greatly toward the end of life. This configuration fairly shouts "risk pool" but requires legislative action because it is more a metaphor than legal reality. It serves to explain to people why we have struggled to close the loop for twenty or more years because what is true for children is definitely not true for Medicare, where the main costs congregate. To meet the disparity, we chose to employ patchwork solutions for a single generation, counting on the enhanced generosity of the public for disabled children to meet the major expense. This appearance contrasts sharply with the deceptively low average cost of ordinary childhood healthcare. The only danger is for this temporary expedient to become a career.

Please note the fiscal dilemma. Even if subsidies or gifts provided a $100 nest egg to start health savings account at birth, 2.5 doublings at 7% would only create a fund of $525 by age 25. That's not nearly enough to fund healthcare for individuals at risk of auto accidents and HIV while trying to pay for college, home mortgages or the like. By contrast, $100 a year for forty years might well pay for all of Medicare while retaining leverage of eight dollars out, for one dollar in. Adding $1400 a year for 20 more years would be much better, at 80 to one. For lucky people, $8127 might work, but its safety margin is too narrow for launching a lifetime medical system. The actual plan proposed is a complicated variant of this approach. As the reader will see, there will be ample funds available for a lump sum donation, once the system has closed the loop, because just 8.5 extra doublings from the beginning of lifetimes to the end of other lifetimes, without supplementation, should silence any remaining doubts, at 256 to one leverage.

Once it gets underway, the two-generation process is very simple, requiring only a few amendments to existing legislation. Extend the age limits of catastrophic high-deductible insurance down to the date of birth, and allow the premiums to compound up to the date of death or 104, the length of a perpetuity. After that, allow surplus Health Savings Accounts of the parents or grandparents to flow over to the HSAs of the child, and allow surplus funds of grandparents and designated others to be transferred (from the date of death of one, to the date of birth of the other) via the HSAs of both. Gifts of this sort might even become a popular item in obituaries, in lieu of flowers.

Springing such a radically different proposal on an unprepared public is potentially to provoke ribald rejection, so it's gradually introduced here as a challenge to provoke alternative proposals. At the moment, I don't see what they would be. We are combining the advantages of two systems, for the young and for the old, which separately they cannot achieve, except through the socially threatened but biologically inescapable, concept of "family".

First Two, and Last Two, Years of Life

Before we get too deep into slicing average lives into average medical partitions, the reader should remember there is another way of viewing health care. Declaring we simply can't pay for everything because there are limited resources, we imply we agree on life's priorities when we really don't.

If this were a contest on TV, no two people might rank priorities the same way. But physicians would come closer. Reflecting common professional experience, most of them would give a special place to the first two years of life, and the last two. Health care costs concentrate there, and special reverence is paid to the patients. The rest of life has long quiet periods, but just about everyone is seeing or trying to see a doctor, during their first two and last two years. If we really must ration care, these are the years to be spared. These are the four years of maximum helplessness. We must keep it in mind. Special consideration is in order.

Fun With Numbers

The principles of compound interest are thought to have been a product of Aristotle's mind. The principles of passive investing are more recent, mainly attributed to John Bogle of Vanguard, although Burton Malkiel of Princeton has a strong claim. In the present section, we propose to merge the two methodologies, compound interest with passive investing, trying to give the reader some idea why the combination could supply Health Savings Accounts with seriously augmented revenue. Because there is so much political flux, it cannot be an actual plan until the politically-controlled numbers have some finality to them.

The proposal to accumulate funds, however, shifts responsibility to the customer to spend wisely, even resorting to employing some of the individual's taxable money to pay small medical costs, thus preserving the tax shelter. (Or to use escrow accounts, or over-deposit in some other way, such as reducing final goals.) HSA doesn't directly reduce health costs, it eliminates some unnecessary ones but provides lots of extra money to pay for essential ones. At the outset we want to state, schemes of this sort have a history of working effectively up to a certain level, and then begin to interfere with themselves as eager money rushes in. There's no sign of that so far, but it might appear. Therefore, we advise modest hedged experiments rather than attempts to pay for all of healthcare, reducing health costs perhaps by only a quarter or a half, since those smaller levels would still amount to large returns. Balancing the risks with investments outside the HSA -- is just another prudent way of hedging the bet.

Money earning seven percent will double in ten years.

|

In fact, we have a tragic example in the nation's pension funds. A few decades ago, pension managers were tempted to invest in stocks rather than bonds, and then the stock market crashed, stranding pensioners with low rates of return, rather than the high ones they had hoped for. I want readers to understand I am well aware of the cyclicity of markets, and make these suggestions, regardless. As long as we include a thirty-year "Black swan" contingency by limiting coverage to a quarter or a third, it should be reasonably safe, but savings would still be enormous. There are other, more traditional ways of protecting endowments from stock crashes. With people of every age to consider, the long transition period alone would almost automatically buffer out black swans.

Having issued a warning to be a conservative investor, let's now introduce some notes of reassurance. Younger people are always likely to be healthier. Those who save their money while young therefore need not use all of it for healthcare -- for several decades. Compound interest works to magnify savings, the longer its horizon the better. We'll describe passive investing later, but it too should increase the average rate of return. These investments after some successes increase the incentives to save. If no one buys Health Savings Accounts, the incentives were apparently not large enough. If everyone rushes to buy, perhaps the incentives were unwisely too attractive. Right now, the financial industry is observing a rush to passive investing; nearly fifty percent of mutual fund investors are switching to "index funds" in spite of capital gains taxes on selling other holdings. Since the marvel of compound interest has been accepted for thousands of years, a mixture of compound interest and passive investing isn't an especially radical idea.

What's radical is the idea that all those highly-paid advisors can't do better than random coin-flippers. What's radical is to discover that the main ingredient of poor performance is high middle-man fees. Low fees won't assure high returns, but high fees will assuredly lead to low returns. If that new idea gets replaced in turn, it will be replaced by something better, and everyone should switch to it. But if compound interest is here to stay, this proposal is safer than it sounds. The investment income rate or continued employment of your agent is what isn't guaranteed, which is why business relationships (between customers and managers of HSAs ought to remain portable and transparent by law. Your manager might move, or you might decide to move away, from him.

Start by looking at what happens if you jump your interest rate curve from 5% to 12%, or if you lengthen life expectancy from age 65 to age 93. That's what the graph is intended to show, and we stretch the limits to see what stress will do. Jumping to the highest rate (12%)the interest rate gets the balance to a couple of million dollars pretty quickly and lengthening the time period further enhances that gain. The combination of the two easily escalates the investment far above twenty million. The combination of extra time and extra interest rate thus holds the promise of quite easily paying for a lengthening lifetime of medical care, regardless of inflation. In fact, it gets the calculation to giddy amounts so quickly it creates suspicion.

Average lifetime health costs: $350,000 per lifetime

|

One person who does have practical control of the interest rate an investor receives is his own broker. The broker shares the income, but usually takes the first cut of it, himself. Covering a full century, Roger Ibbotson has published the returns on various investments, and they don't vary a great deal. Common stock produces a return of between 10% and 12.7% in spite of wars and depressions; if you stand back a few feet, the graph is pretty close to a straight line. You wouldn't guess it was that high, would you? If you don't analyze carefully, a number of brokerages offer Health Savings Accounts which produce no interest at all -- to the investor -- for the first ten years. Indeed, the income of 2% also amounts to nothing at all during a 2% inflation. In ten years, 2% approaches a haircut of nearly 20%, explained by the small size of the accounts, and by the fact that customers who know better will generally just politely look for another vendor. Since the number of accounts has quickly grown to be more than fifteen million, it might be time for some sort of consumer protection. The prospective future size of these accounts should command greater market power, quite soon. After all, passive investment should mainly involve the purchase of blocks of index funds, all with fees of less than a tenth of a percent . Much of this haircutting is explained by the uncertainties of introducing the Affordable Care Act during a recession and taking six years just to get to the point of a Supreme Court Test, to see if its regulations are legal and workable. It can be used to provide high-deductible coverage, but it's expensive.

That's the Theory. The rest of this section is devoted to rearranging healthcare payments in ways which could -- regardless of rough predictions -- easily outdistance guesses about future health costs. When the mind-boggling effects are verified, skeptics are invited to cut them in half, or three quarters, and yet achieve a worthwhile result. The purpose here is not to construct a formula, but to demonstrate the power of an idea. Like all such proposals, this one has the power to turn us into children, playing with matches. By the way, borrowing money to pay bills will conversely only make the burden worse, as we experience with the current "Pay as you go" method. By reversing the borrowing approach we double the improvement from investment, in the sense we stop doing it one way and also start doing the other. In the days when health insurance started, there was no other way possible. The reversal of this system has only recently become plausible, because life expectancy has recently increased so much, and passive investing has put that innovation within most people's reach. The environment has indeed changed, but don't take matters further than the new situation warrants.

Average life expectancy is now 83 years, was 47 in the year 1900; it would not be surprising if life expectancy reached 93 in another 93 years. The main uncertainty lies in our individual future attainment of average life expectancy, which we don't know, but probably could guess with a 10% error. When the future is thus so uncertain, we can display several examples at different levels, in order to keep reminding the reader that precision is neither possible nor necessary, in order to reach many safe conclusions about the average future. Except for one unusual thing: this particular trick is likely to get even better in the future. Even so, it is best to do only conservative things with a radical idea.

Reduced to essentials for this purpose, today's average newborn is going to have 9.3 opportunities to double his money at seven percent return and would have 13.3 doublings at ten percent. Notice the double-bump: as the interest rate increases, it doubles more often, as well as enjoying a higher rate. If you care, that's essentially why compound interest grows so unexpectedly fast. This widening will account for some very surprising results, and it largely creeps up on us, unawares. Because we don't know the precise longevity ahead, and we don't know the interest rate achievable, there is a widening variance between any two estimates. So wide, in fact, it is pointless to achieve precision. Whatever it is, it will be a lot.

|

| One Dollar: Lifetime Compound Interest |

Start with a newborn, and give him a dollar. At age 93, he should end up with between $200 (@7%) and $10,000 (@10%), entirely dependent on the interest rate. That's a big swing. What it suggests is we should work very hard to raise that interest rate, even just a little bit, no matter how we intend to use the money when we are 93, to pay off accumulated lifetime healthcare debts. Don't let anyone tell you it doesn't matter whether interest rates are 7% or 12.7%, because it matters a lot. And by the way, don't kid yourself that a credit card charge doesn't matter if it is 12% or 6%. Call it greed if that pleases you; these "small" differences are profoundly important.

If that lesson has been absorbed, here's another:

In the last fifty or so years, American life expectancy has increased by thirty years. That's enough extra time for three extra doublings at seven percent, right? So, 2,4,8. Whatever amount of money the average person would have had when he died in 1900, is now expected to be eight times as much when he now dies thirty years later in life. And even if he loses half of it in some stock market crash, he will still retain four times as much as he formerly would have had at the earlier death date. The reason increased longevity might rescue us from our own improvidence is the doubling rate starts soaring upward at about the time it gets extended by improved longevity. In particular, look at the family of curves. Its yield turns sharply upward for interest rates between 5% and 10%, and every extra tenth of a percent boosts it appreciably.

Now, hear this. In the past century, inflation has averaged 3%, and small-capitalization common stock averaged 12.7%, give or take 3%, or one standard deviation (One standard deviation includes 2/3 of all the variation in a year.) Some people advocate continuing with 3% inflation, many do not. The bottom line: many things have changed, in health, in longevity, and in stock market transaction costs. Those things may have seemed to change very little, but with the simple multipliers we have pointed out, conclusions become appreciably magnified. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve Chairman says she is targeting an annual inflation rate of 2% of the money in circulation; the actual increase in the past century was 3%. If you do nothing at 3%, your money will be all gone in thirty-three years. If you stay in cash at 2%, it will take fifty years to be all gone.

But if you work at things just a little, you can take advantage of the progressive widening of two curves: three percent for inflation stays pretty flat, but seven percent for investment income starts to soar. Up to 7%, there is a reasonable choice between stocks and bonds; but if you need more than 7% you must invest in stocks. Future inflation and future stock returns may remain at 3 and 7, forever, or they may get tinkered with. But the 3% and 7% curves are getting further apart with every year of increasing longevity. Some people will get lucky or take inordinate risks, and for them, the 10% investment curve might widen from a 3% inflation curve, a whole lot faster. But every single tenth of a percent net improvement will cast a long shadow.

But never, ever forget the reverse: a 7% investment rate will grow vastly faster than 4% will, but if people allow this windfall to be taxed or swindled, the proposal you are reading will fall far short of its promise. Our economy operates between a relatively flat 3% and a sharply rising 4-5%. In other words, it wouldn't have to rise much above 3% inflation rate to be starting to spiral out of control. Our Federal Reserve is well aware of this, the public less so. A sudden international economic tidal wave could easily push inflation out of control, in our country just as much as Greece or Portugal. On the other hand, as developing nations grow more prosperous, our Federal Reserve will control a progressively smaller proportion of international currency. Therefore, we would be able to do less to stem a crisis that we have done in the past.

To summarize, on the revenue side of the ledger, we note the arithmetic that a single deposit of about $55 in a Health Savings Account in 1923 might have grown to about $350,000 by today, in the year 2015, because the stock market did achieve more than 10% return. There is considerable attractiveness to the alternative of extending HSA limits down to the age of birth, and up to the date of death. It's really up to Congress to do it. If the past century's market had grown at merely 6.5% instead of 10%, the $55 would now only be $18,000, so we would already be past the tipping point on rates. In plain language, by using a 10% example, $55 could have reached the sum now presently thought by statisticians -- to be the total health expenditure for a lifetime. By achieving a 6.5% return, however, the same investment would have fallen short of enough money for the purpose. Like the municipalities that gambled on their pension fund returns, that sort of trap must be avoided. Things are not entirely hopeless, because 6.5% would remain adequate if our hypothetical newborn had started with $100, still within a conceivable range for subsidies. But the point to be made provides only a razor-thin margin between buying a Rolls Royce, and buying a motorbike. If you get it right on interest rates and longevity, the cost of the purchase is relatively insignificant. That's the central point of the first two graphs. For some people, it would inevitably lead to investing nothing at all, for personal reasons. Some of the poor will have to be subsidized, some of the timid will have to be prodded. This is more of a research problem than you would guess: a round-about approach is to eliminate the diseases which cost so much, choosing between different paths of research to do it, or rationing to do it. Right now we have a choice; if we delay, the only remaining choice would be rationing.

Commentary.This discussion is, again, mainly to show the reader the enormous power and complexity of compound interest, which most people under-appreciate, as well as the additional power added by extending life expectancy by thirty years this century, and the surprising boost of passive investment income toward 10% by financial transaction technology. Many conclusions can be drawn, including possibly the conclusion that this proposal leaves too narrow a margin of safety to pay for everything. The conclusion I prefer to reach is that this structure is almost good enough, but requires some additional innovation to be safe enough. That line of reasoning will be pursued in a later chapter.Escrow Accounts and Over-Depositing. The main unpredictable feature of these future projections is you can't predict when you will get sick and deplete the account. Money withdrawn early is much more damaging than money withdrawn late in the cycle. Catastrophic insurance will somewhat protect against this risk, but the safest approach is to use segregated, somewhat untouchable, escrow accounts for future heavy expenses. That, combined with deliberate over-depositing, is the safest approach. If Obamacare would settle down, it might serve that function, as well, but the political situation is pretty unsettled until a large-group design is made final, and that seems to mean November 2016 at the earliest.Revenue growing at 10% will rapidly grow faster than expenses at 3%. As experience has shown, it is next to impossible to switch health care to the public sector and still expect investment returns at private sector levels. Repayment of overseas debt does not affect actual domestic health expenditures, but it indirectly affects the value of the dollar, greatly. Without all its recognized weaknesses, a fairly safe description of present data would be that enormous savings in the healthcare system are possible, but only to the degree, we contain next century's medical cost inflation closer to 2% than to 10%. The simplest way to retain revenue at 10% growth, on the other hand, is by anchoring the price to leading healthcare costs within the private sector. The hardest way to do it would be to try to achieve private sector profits, inside the public sector. This chapter describes a middle way. It's better than alternatives, perhaps, but not miraculous.

Cost, One of Two Basic Numbers. Blue Cross of Michigan and two federal agencies put their own data through a formula which created a hypothetical average subscriber's cost for a lifetime at today's prices. The agencies produced a lifetime cost estimate of around $300,000. That's not what we actually spent because so much of medical care has changed, but at such a steady rate that it justifies the assumption, it will continue into the next century. So, although the calculation comes closer to approximating the next century (than what was seen in the last century) it really provides no miraculous method to anticipate future changes in diseases or longevity, either. Inflation and investment returns are assumed to be level, and longevity is assumed to level off. So be warned. This Classical HSA proposal, particularly with merely an annual horizon, proposes a method to pay for a lot of otherwise unfunded medical care. The proposal to pay for all of it began to arise when its full revenue potential began to emerge, rather than the other way around. If a more ambitious Lifetime HSA proposal ever works in full, it has a better chance, but must expect decades of transition before it can. Perhaps that's just as well, considering the recent examples we have of being in too big a hurry. Rather surprisingly, the remaining problem appears merely a matter of 10-15% of revenue, but all such projection is fraught with uncertainty.

Revenue, The Other Problem. The foregoing describes where we got our number for future lifetime medical costs; someone else did it. Our other number is $150,750, which is our figure for average lifetime deposit in an HSA. It's the current limit ($3350 per year of working life) which the Congress applied to deposits in Health Savings Accounts. No doubt, the number was envisioned as the absolute limit of what the average person could afford, and as such seems entirely plausible. You'd have to be rich to afford more than that, and if you weren't rich, you would certainly struggle to afford so much. To summarize the process, the number amounts to a guess at what we can afford. If it turns out we can't afford it, this proposal must be supplemented, and the easiest expedient is to raise the contribution limits. Other alternatives are pretty drastic: to jettison one or two major expenses, like the repayment of our foreign debts for past deficits in healthcare entitlements, or the privatization of Medicare. Not privatizing Medicare sounds fine to most folks, but they probably haven't projected its coming deficits. It would leave us considerably short of paying for lifetime health costs for quite a long transition period, but it might be more politically palatable, like Greece leaving the Euro, than paying more. Almost anything seems better than sacrificing medical care quality, which to me is an unthinkable alternative, just when we were coming within sight of eliminating the diseases which require so much of it.

CHAPTER TWO: Fitting Employer-Based Health Insurance Into an Individual-based Framework

Chapter Two:

No history of American healthcare finance is complete without acknowledging the deep debt of gratitude we all owe to Big Business. Negotiating stormy waters, they created a workable insurance system and held it together for decades. Their legal premise was good health care for employees was essential for modern business. Society has now decided good health care is essential for life. This extension of the mandate has been awkwardly arranged. The main function of this chapter is to ease the transitions between employer-based health care and the other half of life, before and after forty years of employment. In the process, we would like to see Health Savings Accounts become a voluntary alternative for working people, both of them changing enough to co-exist. As a start, I can see no reason to prohibit anybody from having an HSA, with or without employer insurance as well. Nor can I see the slightest justification for unequal income tax treatment. Yes, health insurance companies must make some major changes, but after all, we're talking about changing health insurance.

History. Theodore Roosevelt had proposed a system of national health insurance, probably based on the example of Bismarck's German system, and Teddy nearly pulled it off. The American Medical Association considered the reform idea quite favorably until some physician leader (legend relates it was Morris Fishbein) had a change of heart and denounced it. Legend also has it that Fishbein was influenced by the bad treatment the Mensheviks received at the hands of the Bolsheviks in Russia. Fishbein was related to many Mensheviks, and this is said to have influenced his thinking, although its connection to Bismarck and the Flexner Report is a trifle hard to understand at this distance. Word of mouth history also blames this episode for the alienation of academic medicine (medical schools) from organized medicine (the AMA), dating from this issue. Somehow or other, this has to do with the Flexner Report of 1914, favoring the affiliation of medical schools to research universities. Much of this is gossip, and much of it is possibly quite wrong. It is related here to help the reader understand why many present political alignments exist, even if they do not explain why they persist. The fact that hardly anyone alive can recount precise details, does not diminish the intensity with which some present partisans hold their (possibly mistaken) beliefs.

Big Business was obviously drawn into a dispute of this magnitude, but in view of Teddy Roosevelt's past activities as a trust-buster, business leadership was unable to unite its constituents into taking one side or the other, openly. That division continues to this day, although it is fair to say the leadership of Big Business leaned in the direction of "reform" of the healthcare system, even while many heavy hitters in their ranks still remain violently opposed. Businessmen lean heavily on their lawyers for advice about non-business issues, and there can be no doubt it makes Big Business uneasy to read the plain language of the Constitution, especially the Tenth Amendment, and the McCarran Ferguson Act of 1945. The Constitution firmly proclaims the Federal Government is to have only a limited role in most areas, so medical care is therefore regulated by state governments. As a reminder, the states license hospitals, universities, medical schools and physicians, and the entire structure of organized medicine revolves around state control. As well as upon the Constitution, for which all this stands. The President of every county medical society in the nation takes his inaugural oath, with the wording of great similarity to those of George Washington, to uphold the Constitution. Not the Governor, or the State, but the Constitution. Medical Schools, nursing societies, hospital administrators and all similar officers are expected to take much the same oath, although many feel free to disregard it. When they do so, they meet the glares of many physicians and many lawyers. A corporation is only a creature of the state legislature, and all lawyers know what danger lies in flouting the courts.

With all this background of stern rules and bitter recollections, it must have taken skill and courage for Big Business to act as negotiator and peace-maker in constructing the collection of compromises and invisible unity, now called employer-based health insurance. The edifice was negotiated in the 1920s and rescued the health system from near-dissolution after the crash of 1929. Much of its strength lay in family-controlled corporations with close associations to local hospitals and other members of civil society. As family-held businesses gave way to stockholder-controlled corporations, American business became much less local and more national, with hired managers much more congenial with government bureaucrats and university presidents, than self-made entrepreneurs ever felt. The stage was set for "reform", and for several decades things seemed to work very well. Its legal high point was probably Franklin Roosevelt's court-packing confrontation, which Harry Truman tried but was unable to exploit. In 1965 Lyndon Johnson succeeded in some patchwork, successful for old folks, a failure for poor people. Hillary Clinton tried again and failed, with rumors circulating that Big Business had ruined her plan. Then Barack Obama tried the same plan; whether he succeeded or failed is yet to be made clear. In all these efforts, the issue was the same: take control of healthcare away from the States, and give it to the Federal Government. The decisive argument for business to avoid total war was also the same: if you ignore the Constitution for medical care, you may find you have opened the door for federal conquest -- of all corporate independence.

That's a capsule history of healthcare reform, confessing it must contain many omissions about closed-door arrangements. And leaving to last mention, Henry Kaiser's tax-avoidance scheme during World War II. In an effort to move steelworkers from the East Coast to build ships in his West Coast shipyards, Kaiser found wartime wage controls prevented him from paying workers to move. So he persuaded the War Production Board to look the other way from his healthcare scheme, devised as a non-taxable inducement. After the war ended, Congress continued to include employer-donated healthcare as a necessary business expense for the employer, while excluding it from the taxable income of the employee who got the "gift". Furthermore, the same tax exclusion was denied for the same expense unless it was donated by an employer. For seventy subsequent years, the tax abatements have repeatedly defied Congressional repeal, in spite of the denial of the same tax abatements for competitors. In this case, competitors are foreigners without voting rights, uninsured persons, and self-insured. The critical legal issue was health insurance had to be donated by the employer to qualify. Management would have everyone believe they are powerless to persuade unions to be reasonable. In the next section, we explore other motives and suggest a different solution.

Corporation Tax Deductions Support Our Health System.

This is the last anecdote, I promise you. It has to do with Ireland, the Emerald Isle, in 2000. In an effort to attract corporations to move there, the Irish Republic lowered its corporate income tax to 12.5%, an unheard-of low rate. To Irish delight, corporations in Sweden, Scotland, Germany and many other nations, promptly moved to Ireland to enjoy the low taxes. Since Ireland is mostly rural, there was a migration of Irish workers from the country to the city, causing a housing shortage in Dublin. A taxi driver, in passing a little Dublin shack, was pleased to tell foreign visitors the shack had just sold for a million dollars. That, in turn, set off a building boom, bringing construction workers to Dublin, and causing a shortage of mortgages, leading to boom-time rates. Irish bankers were delighted that little banks could be so top-heavy with imported mortgage money. The little Irish banks became overextended, and promptly collapsed, taking the stock market with them.

The moral of this little Irish tale is clear: lowering corporate taxes will definitely attract businesses to relocate to your shores, but if you lower them too much, too fast, it can cause a disaster. Some people conclude from this you should never lower corporate taxes; other people conclude you should lower taxes, but do it carefully and slowly. In the American case at present, it is tempting to try it to stimulate the economy, but we owe a powerful moral debt to the Europeans, who are in bad economic condition. If only we could devise a way to punish our enemies but not our friends, it would seem perfect. Selecting certain manufacturers but skipping others would do the trick nicely. By the way, our federal corporate tax is 35%. That's the highest in the developed world, so our hands are tied -- we're sorry, but we just have to do it to keep our own corporations from moving to Ireland. Other nations, like Japan and Switzerland, would be sure to notice we have this power, even if we don't use it against them. Yet. We hold a powerful international weapon, providing we use it sparingly, but gracefully.

And our own corporations? Well, that's the whole point. We would like them to take the pressure off health insurance, either by allowing other health insurance to be tax-exempt or by telling their lobbyists to look the other way while we remove Henry Kaiser's little gimmick. There's even a compromise, for those who admire bi-partisanship. Lower the tax exemption for existing corporations, but extend them to other companies and people in general. We're not looking to lose or gain revenue, we are looking for equal treatment under the law. And finally, the best way of all would only require one sentence. Just amend the Health Savings Account Law to permit the premiums for mandatory Catastrophic high deductible to be paid out of the account. Since the Accounts are tax-exempt, the reinsurance premiums would be, too. The level playing field for health insurance is restored in an instant. Only after the inequality resistance is removed, can you consider lowering the exemption.

Well, fine, what about corporate taxes? Since I am a single-issue voter, it isn't in my interest to declare a position on unrelated issues. But I stay within my medical mandate if I point out one thing about the politics of this. You don't have to be a magician to guess some corporations would like to have a tax reduction, because a tax reduction is a money in the bank. Other corporations might persist in the party line that it serves our interest to leave things alone. So, the leadership might just have to stand by, while a newly elected hothead makes a name for himself by introducing a bill to eliminate corporate taxes, entirely. Just what would the consequences be?

A tax deduction of 35% is a tidy sum, all right, but many states have a 10% tax, so it's really 45%. But look at what happens when you give your employees health insurance. It's a business expense, so a $10,000 health insurance policy only costs the company $5500. And then, remember the first chapter of this book. Every employee gets a payroll deduction of 2.9%, up to $117,000 of salary. That's another $3000, per employee. Some companies have hundreds of thousands of employees. And if you've got high-priced employees over $200,000 in salary, it's another $3800, but notice this: there's no top limit to the taxable salary, so if you've got a $10 million president, he's generating a $380,000 deduction for the company. Many companies positively love expensive health insurance, which includes extremely dubious Flexible Savings Accounts with a use-it-or-lose-it feature, leading to prescription sunglasses toward the end of December if the employe hasn't used it. All of those other deductions on a pay stub except the income tax withholding are probably eligible for tax deductions, too. It isn't too hard to imagine a resourceful accountant who could make the whole donation of health insurance a free gift, when you remember all employees are getting a tax deduction of several thousand dollars, too. The higher the premium the better, which isn't at all a good thing for market prices for the rest of us. The only thing which limits more and more deductible items is the company runs out of taxes to deduct from. Who wants lower corporate taxes? Not us, think a lot of companies.

And then, there's Greece. We can't lower corporate taxes more than 10% at a time, for fear of bankrupting Greece and sending the financial world into a tailspin. So even the most rabid populist can be persuaded to limit the size and pace of the deductions. Therefore, we have some other things on our wish-list while we wait to watch how low corporate tax can safely go. That being the case, there are some other things on the wish-list while we watch what gradual corporate tax reduction can do. I would like to see every Flexible Spending Account roll over its end of year surplus into a Health Savings Account. That would immediately create several million new HSAs, meanwhile getting some good for the money. I'm really serious about Health Savings Accounts. Everybody ought to have one, so remove the prohibition on having more than one health policy. What we mean to prohibit is taking two tax deductions, so say so, and let people have as many accounts as they want. This is particularly important if you want to reap compound interest for newborns for an extra 26 years, but there are probably lots of retirees who are healthy and want to store up their benefits for later, but now have nowhere to put them. Of course, we should allow everyone to have both an Obamacare policy and a Health Savings Account, with the proviso you can't take a double tax deduction. Not everyone will do it, and of those who do, not everyone will use both. But as long as they don't game the system, why not? It's a lot easier to defend freedom of choice than prohibitions.

Good Ol' Health Savings Accounts

In 1981 at what was then called the Executive Office Building of the Reagan White House, John McClaughry and I conceived the Medical Savings Account, later known as the Health Savings Account. John was at that time Senior Policy Advisor for Food and Agriculture, but he had read my book The Hospital That Ate Chicago, and it inspired him to think about a better way of financing health care. He asked me to come down to Washington to discuss the issue. We met and fleshed out the idea. Little did we then suspect how many delightful features would pour out of the simple little invention with only two moving parts.

It was patterned after the tax-deductible IRA (Individual Retirement Account) which Senator Bill Roth of Delaware was bringing out the following year. But with two major variations: our account contained the unique feature of a second tax exemption, given on condition the withdrawal was spent on health care. Otherwise, a regular IRA subscriber pays the usual income tax on withdrawals and gets only one tax deduction, the one he gets when he deposits money into the account. Bill Roth later produced his second kind, the Roth IRA, which allowed a tax-exempt withdrawal but took away the tax-exempt deposit. Only the Health Savings Account gives you both. In Canada, by the way, they do allow both deductions in their IRA, but in America only the HSA offers it.

Garlands of Unexpected Good Features. So the first part of a Health Savings Account is just that, a tax-exempt savings account, obtainable in the same way you get an IRA or a Roth IRA, although a few eligible outlets were slow to take ours up. And the second combined feature was to require a high-deductible, "catastrophic", stop-loss health insurance policy -- the higher the deductible, the cheaper the premium gets.

Further, the more you deposit in the account, the higher is the deductible you can afford, so you save money going either way and get extra benefit in your account for having a tailor-made insurance program. The industry term for this kind of insurance is "excess major medical", which the two of us wanted to avoid because of its implication it was somehow frivolous or unnecessary, when in fact it is central to the whole idea. Linked together, the two parts enhanced each other and produced results beyond the power of either, alone. The savings account was first envisioned to cover the deductible, but nowadays it also commonly attaches a special debit card to purchase relatively inexpensive outpatient and prescription costs. That led to further administrative savings to the subscriber if he shopped frugally for optimum proportions of deductible insurance. Right now, it's a little uncertain what the current Administration will permit in the way of catastrophic health insurance, so, unfortunately, it is just about impossible to give concrete examples of what the ultimate cost will prove to be. But we do know that in the old days, a $25,000 deductible was available for $100 a year. Nowadays, a $1000 premium is more likely. When we get to explaining first year and last year of life insurance, it will become clear that this premium can be appreciably reduced.

But while the savings account allowed someone to keep personal savings for himself, the insurance spreads the risk of an occasional heavy medical expense at what ought to be a bargain price for bare-bones insurance. You needn't spread any risk for small expenses because you control them yourself, but no one can afford some of those occasional whopper expenses. There's no reason why you couldn't set the deductible level yourself, weighing your own ability to withstand bigger risks. In practice, the actual savings were reported to approach 30% (compared with "First-dollar" health insurance), quite a pleasant surprise. But because of the younger age group of the early adopters, much of this saving was achieved in the out-patient area.

(Let's start using the present tense to talk about it, although right now it's hard to know what politics will permit.) So, hidden in this bland dual package are lower premiums, less administrative red tape, less moral hazard, but complete coverage. Right now, that's somewhat subject to change. It provides complete coverage in the sense that the insurance deductible can be covered by the savings account, but contains the option to be saved, invested or used for small outpatient expenses. Furthermore, the account carries over from year to year and employer to employer. So it eliminates job-lock, use-it-or-lose annoyances, and allows a healthy young person to save for his sickly old age. Curiously, many of the subscribers have elected to pay small expenses out of pocket, in order to make the tax deduction stretch farther.

In one deceptively simple feature, many of the drawbacks of conventional health insurance have been removed. The bank statement from the debit card can even do the bookkeeping. The first part of the two-part package, the savings account, creates portability between employers, opens up the possibility of compound interest on unused premiums, eliminates pre-existing conditions even as a concept, and creates a vehicle for transferring the value of being a "young invincible" forward into age ranges when the money really is likely to be needed for healthcare. Maybe some other features can be added later, but introducing an unfamiliar product is always greatly assisted by having it all appear so simple. The HSA only has two features, but they solve a dozen pre-existing problems.

To return to its history, nearly 15 million accounts have been opened, containing $24 billion. John McClaughry and I (neither of us received a penny for any part of this) were seeking a way to provide a tax exemption to match the one which employees of big business get when the employer buys insurance for them. That is, Henry Kaiser inspired us to do it. Although we got the general tax-free savings idea from Bill Roth, we did him one better by giving a deduction at both ends, provided only -- you must spend the money on healthcare to get the second tax relief. An additional novelty at that time was a high deductible, which permits a "share the risk" feature unique to all insurance, but invisibly limits it too expensive items. It wasn't the original idea, but it turns out you get spread-the-risk and limits to out-of-pocket patient costs in the same package. Who could have guessed?

Volume control versus Price Control in Helpless Patients.We did know a third automatic advantage, not fully exploited so far: it seems possible the hateful DRG system (with its codes restructured) could become a useful tool for dealing with a major flaw in the Medicare system. Professional peer review has become pretty good at controlling the volume of services, but prices still escape effective control. No amount of volume control can, alone, address the price issue. Controlling vital services for helpless people is a delicate matter.Other than two variations (double tax deductions, and incentives if used for health care), a Roth IRA would be nearly the same as an HSA, with independently purchased Catastrophic backup. But the assured presence of low-cost, high-deductible insurance provides security for another needed feature: Using individual accounts with year-to-year rollover , we could introduce the notion of frugal young people pre-paying the healthcare costs of their own old age. For all we knew, there weren't any frugal young people, but we were certainly pleasantly surprised. And catastrophic insurance added the ability to share the opportunity of that feature -- subsidizing the poor at bearable prices. As we will shortly see, it also offers an incentive to save for retirement. Think of it: almost nobody can afford a million-dollar medical bill, but almost everybody welcomes low premiums. Catastrophic coverage offers the only chance I know, of approaching both goals at once. And it offers the fall-back, that if you are lucky and don't get sick, you can use it for your retirement.Quite a few of those services match (or contain) identical items in the outpatient area. The outpatient area faces outside competition from other hospitals, drugstores or vendors. Instead of letting helpless inpatients generate unlimited prices for the outpatients, why not let competition in the outpatient area define standards of prices for inpatient captives? Outpatients and inpatients overlap in the ingredient components, considerably more than most people suppose. Inpatients may have higher overhead because of the need to supply their needs at all hours, but a standard extra markup around 10% ought to take care of that. No doubt some services are unique to the inpatient area, but a relative value scale is then easily constructed, thereby linking unique costs to other services which are exposed to competition. Ultimately, provable relationships to market prices might even discipline big payers demanding unwarranted discounts. This last is a deal breaker, provoking suspicions of abused power by a fiduciary. The government in the form of Medicaid is often the worst offender, so we need not imagine laws will prevent discounts so long as law enforcement remains crippled. Every business school teaches that discounts below cost are a path to bankruptcy, but business schools have apparently not had enough experience with governments to suggest an effective remedy.

As the only physician in the room, I also pointed out another pretty gruesome fact: either people end their lives have a lot of sicknesses, or they end up paying for a protracted old age. Only infrequently, do real people encounter both problems. It can happen of course; breaking a hip after long confinement in bed would be an example.

People end their lives with sickness, or else they must pay for protracted old age.

|

A tax deduction is a tax deduction, but this one has two: An incentive to save, and a later option to spend the savings on either healthcare or retirement. That's nearly specific enough. Furthermore, it offers a choice between saving preferences -- you can have interest-bearing savings accounts, or you can invest in the stock market, or a mixture of both. The HSA automatically converts to a regular IRA (for retirement) at age 66 when Medicare appears; that should be optional for all health insurance, but isn't. The IRA up in Canada includes both front and back features, but in the United States the HSA is the only savings vehicle to have dual deductions, so it's more flexible. As the finances of Medicare become shaky, it may be time to provide additional alternatives. At least, we ought to consider extending age 66 to a lifetime coverage option.

This harnessing of two familiar approaches makes a deceptively simple package which ought to be considered in other environments, unconnected with medical care. In most public policy proposals, the deeper you dig, the more problems you turn up. In this one, we found the proposal already had hidden answers to most concerns we could discover. It's possible to fall in love with an idea that does that for you. It lets you sleep at night, secure in the knowledge you aren't mucking things up for people.

Another surprise. Overall, the Affordable Care Act has probably helped sales of HSAs, since all four "metal" plans of the ACA contain high deductibles, serving in a (rather over-priced) Catastrophic role. This may be a way of covering the bets in a confusing situation. The ACA is a needlessly expensive way to get high-deductible coverage because it pays for so many subsidies. Frankly, it baffles me why subsidies swamp the costs of Obamacare but are made unworkable for HSAs. Many of the details of the subsidies are obscure, including their constitutionality, so we have to set this aside for the moment.

One good motto is don't knock the competition, but we must comment on a few things. The Bronze plan is the cheapest, therefore the best choice for those who choose to go this way. But uncomplicated, plain, indemnity high-deductible, would be even cheaper if its status got clarified. The good part is, the current rapid spread of high deductibles suggests mandatory-coverage laws may, in time, slowly go away. At first, the ACA looked like a bundle of mandatory coverages, all made mandatory at once. But they may be learning a few basic lessons as they go. Mandatory benefits are an example of mixing fixed indemnity with service benefits, with the usual dangerous outcome. Like many dual-option systems, they create loopholes. The HSA seems to avoid this issue by effectively being two semi-independent plans, for two separate constituencies -- who are the same people at different ages. Once more, we didn't think of it, the features just emerged from the plan.

That's about as concise a summary of Health Savings Accounts as can be made without getting short of breath. But of course, there is more to it, particularly as it affects the poor. For example, there is an annual limit to deposits in the Health Savings Account of $3350 per person, and further deposits may not be added after age 65. They can be "rolled over" into regular HSAs when the individual gets Medicare coverage, and supposedly has no further financial needs. So plenty of people have health care, but can barely support their retirement. These plans are absolutely not exclusively attractive to rich people, but it must be admitted, poor people start with such small accounts that companies can't operate profitably unless the client sticks with them for a long time. If people possibly can, they should scrape together one $3300 maximum payment to get a running start.

The problems of poor people can nevertheless be eased, within the limits of the plan's design. Since people will be of different ages when they start an HSA, it might be better to set lifetime limits, or possibly five-year limits, to deposits, rather than yearly ones. Some occupations have great volatility in earnings, and sometimes a health problem is the cause of it. To reduce gaming the system, perhaps the individual should be permitted to choose between yearly and multi-year limits, but not use both simultaneously. As long as the self-employed are discriminated against in tax exemptions, that point could certainly be modified. There remains only one major flaw, which we propose should be fixed: