1 Volumes

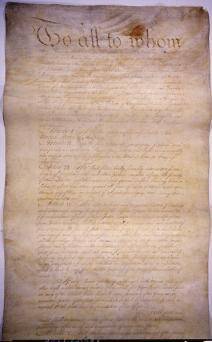

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Popular Passages

New topic 2013-02-05 15:24:06 description

A Time to Read Books

|

| Retirement Reading |

BEFORE we talk about retirees reading books in a retirement community, reflect for a moment about reading in your own home during the working years. Most suburban homes do not have many books in evidence. It's possible to stand in the center of most suburban living rooms unable to see a single book, while it's hard not to see a television set. Increasingly, a home computer is only a few steps from the front door, but the evolution from desktop to laptop to portable telephone to tablet is too rapid to make generalizations. Everyone says books are going to disappear soon, and newspapers maybe even sooner. But there are still said to be a million books constantly in transit on 18-wheeler trucks between print shops and wholesale depositories, night and day. Right now, the producers, publishers and merchandizers of printed material are in turmoil and decline, so they talk about it a lot. But ultimately it is the reading public which will decide what it wants and force the suppliers to give it to them.

|

| reading |

It seems to me that what the reading public wants most is to find time to read. The suburban home has so few books because the sort of person who lives in the suburbs to be near the school system, just doesn't have time to read after the day's work and commuting. Helicopter parents spend a lot of time hauling the kids to mandatory kid entertainments, as can easily be seen by driving past a high school in the afternoon and observing the lines of cars with waiting mothers. They make the best of it as a social occasion for mothers with shiny cars, but they really do it to be sure the kids don't get mixed up with recreational drugs. Anyway, they do it, and it all eats up their discretionary time for reading. Meanwhile, their's no local bookstore to buy books, even unread books. They may think they will catch up on their reading after they retire, but that's becoming increasingly unlikely in my observation. They are getting out of the habit of reading. By the time they retire, they will find it's almost like going back to school. You must find other readers, readers groups, conversations about books over the bridge table, books lying about. The first economy a struggling news paper makes is to cut down the size and number of book reviews, because there are no bookstores to take out advertising, and advertising is what pays for newspapers. There's one good feature about that; what book chatter there is, is not so confined to recent books. Some people are bookish and other people are golf-ish, and a growing number of people are simply TV-ish. It's a struggle to find time for work and the family, and books on top of that. No matter what level of reading the working people may be doing, it's declining in favor of deferred reading when they finally retire.

|

| Retirement Community |

Having visited quite a number of retirement communities, I find the community's library is a good place to assess the institution and its typical inhabitant. When it's newly built, a library area is set aside, usually without many books. The first few waves of residents quickly fill up the space with books they brought from home. During the first ten years it is possible to guess what sort of person lives there by the books they brought and deposited, or died and left to the library. The space, more or less empty at first, gets full and something must be discarded. Enlarging the library is an economic issue, so the size at which it halts will to considerable degree reflect the willingness equilibrium to pay for new construction, both by the book lovers, and by the book enemies, the golfers and the administrators. Ultimately book congestion gets to the point where someone simply must cull out some old books to make room for the new. In another essay I have described the use of volunteers to exchange books of no lasting interest for more books of real interest to real residents, through a used-book exchange. But someone must organize the process, often recruited by an administrator who has learned to be horrified of construction which cannot be rented, but must be cleaned and cared for. If passive resistance is a new term to you, this is the place to learn about it. The residents have short memories, lack drive and follow-through. So inertia tends to win, and lack of reading feeds on itself because there is nothing to read. What's apparently needed here is an organization of bookish people that extends to all retirement communities, probably with a paid staff, an annual meeting, Internet connections. And therefore an immortality which can outlive and outlast the passive resistance. Good ideas then have a means to spread and help support other good ideas; somehow the costs must be supported until a few True Believers in Books can write a bequest in their wills to sustain it. And activate their intention, so to speak.

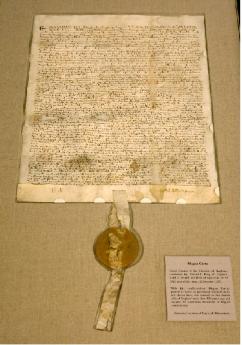

One of the largely unrecognized reasons for the success of the American Revolution was that the Colonies had a higher level of literacy than the Mother Countries. Thomas Paine, for example, printed 150,000 copies of Common Sense on the rickety old printing presses of the 18th century, when there were fewer than three million white inhabitants of the thirteen colonies. And who was mainly responsible for that? It was Benjamin Franklin with his invention and popularization of the lending library. If Ben could find time to start libraries in 1742, and Andrew Carnegie was later found willing to pay for dozens of them, surely the time and energy can be marshaled in the 21st century to establish a first-class library system throughout the retirement communities of the nation.

Germantown Nurses the Yellow Fever, 1793

|

| Yellow Fever, Phila |

The French Revolution continued from 1789 to 1799 and created the opportunity for a second revolution in the New World which a second overstretched European country would lose. The slaves of Haiti just about exterminated the white settlers, except for the few who escaped, taking Yellow Fever and Dengue with them. Both diseases are mosquito-borne, so they flare up in the summer and die down in the winter, although the Philadelphians who welcomed the exiles didn't know that. Yellow Fever in Philadelphia was bad in 1793, came back annually for three more years, and flared up once again in 1798. It could be easily observed to be more frequent in the lowlands, absent in the hills. Seasonal, it reached a peak in October, disappeared after the first frost. In the early fall, people died a horrible yellow death, jaundiced and bilious.

|

| Dr. Rush |

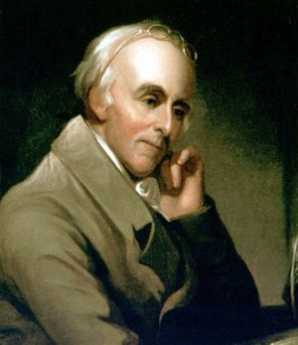

The Yellow Fever epidemic had a profound effect on many things. It was one of the major reasons the nation's capital did not remain in Philadelphia. It made the reputation of Dr. Benjamin Rush who announced a highly unfortunate treatment -- bleeding the victims -- thus provoking numerous anti-scientific medical doctrines based on the relative superiority of doing nothing at all. In Latin, Galen had capsulized the doctrine of Hippocrates in the "Epidemics" as premium non-nocere ("At least do no harm.") It took a full century for American scientific medicine to recover from this blow to its reputation. Whatever criticism Rush may deserve for his Yellow Fever blunder, it definitely is not true that he was a scientific lemon. Medical students are regularly surprised to learn that he is the physician who first identified and described the tropical disease of Dengue, or "break-bone fever", which was a somewhat less noticed feature among the Haiti exiles in Philadelphia. In still other scientific circles, Benjamin Rush is often referred to as the "Father of American Psychiatry". He was one of the founders of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, the oldest medical society in North America. Medical colleagues who today scoff at the yellow fever episode seem to forget that Rush stayed behind to tend the sick during a devastating epidemic, while many of his more cautious colleagues fled for their lives. An unhesitating signer of the Declaration of Independence, whatever Rush did, he did courageously. Non-academic physicians have sarcastically referred to this episode ever since, as proving that "some people" think it is "better to publish than to perish".

One very good non-medical thing the Yellow Fever epidemic accomplished was to put an abrupt end to the torch-light parades of window-breaking rioters agitating, with Jefferson's approval, for an American version of the guillotine and the terror. Federalists like John Adams and William Bingham never forgave Jefferson or his admirers for this, so the class warfare movement might likely have got much worse if everyone had not suddenly dropped tools, and headed for the hilly safety of Germantown.

The President of the new republic, George Washington, was in Mt. Vernon in the summer of 1793, wondering what to do about the Yellow Fever epidemic, and particularly uncertain what the Constitution empowered him to do. He finally decided to rent rooms in Germantown and called a cabinet meeting there. His first rooms were rented from Frederick Herman, a pastor of the Reformed Church and teacher at the Union School, although he later moved to 5442 Germantown Ave, the home of Col. Franks. Jefferson chose to room at the King of Prussia Tavern.

During this time, Germantown was the seat of the nation's government. As was fervently hoped for, the cases of yellow fever stopped appearing in late October, and eventually, it seemed safe to convene Congress in Philadelphia as originally scheduled, on December 2.

Although Germantown was badly shaken by the experience, it was a heady experience to be the nation's capital. Meanwhile, a great many rich, powerful and important people had come to see what a nice place it was. Germantown then entered the second period of growth and flourishing. Walking around Germantown today is like wandering through the ruins of the Roman forum, silently tolerant of visitors who would have never dared approach it in its heyday.

REFERENCES

| Benjamin Rush: A Discourse delivered before the College of Physicians of Philadelphia: Thomas A. Horrocks ASIN: B0006FCBXS | Amazon |

| Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague Of Yellow Fever In Philadelphia In 1793: J.H. Powell ISBN-13: 978-1436715881 | Amazon |

| Germantown and the Germans: An Exhibition from the Collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia: Edwin, II Wolf ISBN-13: 978-0914076728 | Amazon |

Two Friends Create the Articles of Confederation

|

JOHN Dickinson had been highly critical of England's treatment of its colonies. As early as 1768 he had written a book called Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer which is credited with strongly influencing the colonies in the direction of resistance to the British Ministry. When it came time to write the Articles of Confederation, Dickinson was the lawyer selected for the task. His good friend Robert Morris had been less outspoken in opposition to the Ministry's behavior, quite possibly because he was adept at finding workarounds for his own personal business problems. But possibly he was merely maintaining an ambiguous negotiating posture, since in a hotly contested election with this as the main issue, Morris was elected by both sides in the argument. When July 4, 1776, forced the issue both Dickinson and Morris had refused to sign the Declaration, but within a few months both of them were actively fighting for the Rebellion. The truest test of their evolving attitudes might have emerged when Lord North sent the Earl of Carlisle as an emissary after Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, offering peace with a sort of commonwealth status for the colonies. Not much is written about this curious episode, leaving it unclear whether the British were serious, and even if they were, whether the Americans understood the offer as serious. On the surface, the British offer conceded taxation with representation as the rebellion had been demanding. But it was rejected by Gouverneur Morris acting for -- who remains unclear. It seems possible the British were exploring the true feelings of people like Dickinson and Robert Morris but were disappointed. The earlier treatment of Ireland after it had agreed to a similar half-hearted autonomy did leave British sincerity in legitimate doubt.

|

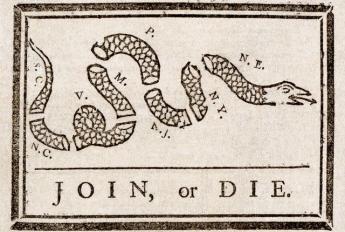

| Thirteen |

The thirteen colonies had united to fight the British King, but many of them were reluctant to unite for any other time or purpose. Rhode Island was perhaps the extreme example of this view of what Independence was supposed to mean, but the feeling existed to some degree in many colonies. Concern for the power of this feeling of tentativeness may have contributed an important reason the Articles placed heavy emphasis on declaring the document to represent a perpetual arrangement. Recognition of the weakness of this intent may have been an important reason why George Washington was later willing to sweep the issue aside, even though he of all people was most concerned to avoid the appearance of acting as an arbitrary king. For these and other reasons mainly revolving around state boundary disputes, the Articles remained unratified for years. Finally, in 1781 Robert Morris became convinced that failure to ratify was encouraging the states not to cooperate, and successfully pushed ratification through its steps. At that time, Morris was effectively running the country, even providing his own credit and funds to do it. People were reluctant to oppose his wishes, but they were also unwilling to provide the taxes, supplies, and troops that Morris imagined were being blocked by failure to ratify. Ratification of the Articles accomplished very little except to convince Morris: the Articles were flawed and must be replaced with something conferring more central power.

|

| The Goal: 1787 |

Little is known about the evolution of Constitutional thought in Morris' mind between 1781 and the Constitutional Convention in 1787, although a great deal is known about his other numerous activities. It is clear, however, that his experience with the recalcitrant Pennsylvania Legislature had been dismal, while he came to see the one insurmountable flaw in the current Federal government was its inability to levy taxes and consequently, to service national debt. The states were able to levy taxes under the Articles but erratic in doing so, resorting to paper money inflation at the first sign of tax resistance. In Morris' view, the key to the effective government was to reverse the situation; let the national government tax, let the states spend. The key to such rearrangement would be to permit the national government to spend on a very limited list of vital purposes, but bedazzle the states with a substantially unlimited shopping list if they thought they could afford it. As the accounts to pay for the Revolutionary War totaled up, it was apparent that the National Government had twice as much debt as the states. Therefore it would at most, need twice the state taxing power to service such a debt; presumably, wars would be infrequent and it would be less than that. Pay this one off, and potentially the need for future federal spending would be small. Indeed, under the presidency of James Monroe, the national debt was completely paid off, although briefly. It was almost as if Robert Morris and his pupil Alexander Hamilton had a crystal ball.

|

| Decline and Fall, Anyone? |

Robert Morris was brilliant and had six years to fashion his strategy, but he also had some help. For one thing, George Washington lived next door much of that time. By then, almost no one dared confront Washington. Adam Smith had written his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776, and Morris gave this extraordinary work as presents to his friends. Morris had corresponded with Necker, the genius financier of France, and through his good friend Benjamin Franklin, gathered insights from the rather advanced British national finance. And James Madison brought in scholarship about politics and statecraft accumulated by Witherspoon, Hume and the Scottish enlightenment. The year 1776 was a remarkable moment for new ideas. In that year, Edward Gibbon also published the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The warning behind that important book had an important impact on the minds of important thinkers of the era, too.

Once you grasped all the central ideas, in this environment the resulting strategy almost worked itself out.

Signers and Non-Signers of the Constitution

|

| Signers of The Constitution |

John Dickinson was active in designing both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, but he signed neither one. His position on the Declaration was that England had behaved in an offensive way; but the situation was getting better and it was still possible to patch things up, even with a British fleet in New York harbor displaying hostile intent. His later position on the Constitution is less clear. Dickinson asked George Read to sign his name because he was sick. Whether this was a real illness or a diplomatic illness is not readily known.

Three active delegates made no bones about their opposition to the final product: Edmond Randolph and George Mason of Virginia were not mollified by private assurances that a Bill of Rights was necessary but could be added later. They refused to sign a constitution that did not currently include this most passionate of their demands. There is little doubt of their sincerity, but any politician today would recognize they also needed to protect their flank from Patrick Henry who stayed at home denouncing the whole enterprise. Henry was a powerful speaker, representing the Scotch-Irish Virginia Piedmont area. In Scotland, Ireland, and America, that group had been abused by English kings three times and wanted iron-clad protection against backsliding to English rule or English government models. It's quite possible that Virginia's George Wythe and James McClurg left the convention early in order to avoid the local political consequences of signing the document, or the equally uncomfortable stance of opposing George Washington. The sentiments of Virginia can be surmised when of the seven delegates sent by Virginia, only John Blair joined the two instigators, George Washington and James Madison in announcing their approval. A majority of the Virginia delegation was thus held back on ratification until only one last vote was needed for enactment. Without George Washington, there can be little doubt the whole effort would have failed. Indeed, a case could be made that the location of the District of Columbia and the election of Virginians as four of the first five presidents also has the appearance of trying to persuade the six hundred pound Virginia gorilla to play nice.

Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts similarly refused to sign any constitution which did not include a Bill of Rights. However, Gerry undermined his stance on principle by inventing the technique of packing his opposition into one voting district (by shifting its borders) so his own party could win narrow majorities in several other districts. This sleazy manipulation of loopholes in the system has become known as Gerrymandering and raises a question perhaps unfairly, of where Gerry actually stood on every other issue in the Constitutional Convention. By contrast, it is impossible to imagine George Washington doing such a thing, and quite possible to imagine he would never again speak to someone who did.

In addition to the three delegates who stayed to the end but refused to sign, an additional four left early to demonstrate their protest: John Lansing and Robert Yates of New York; and Luther Martin and John Mercer of Maryland.

We are left less clear about the opinions of seven more who simply left the convention early (Oliver Ellsworth of Connecticut, William Houston and William Pierce of Georgia, Caleb Strong of Massachusetts, William Houston of New Jersey, and William Davie and Alexander Martin of North Carolina.) The same uncertainty extends to the eighteen delegates who were invited to attend but either refused or regretted their inability to attend: (Erastus Wolcott of Connecticut, Nathaniel Pendleton and George Walton of Georgia, Charles Carroll, Gabriel Duvall, Robert Hanson Harrison, Thomas Sim Lee, and Thomas Stone of Maryland, Francis Dana of Massachusetts, John Pickering and Benjamin West of New Hampshire, Abraham Clark and John Neilson of New Jersey, Richard Caswell and Willie Jones of North Carolina, Henry Laurens of South Carolina, and Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and Thomas Nelson of Virginia). These men were originally selected because of their local eminence, so some of them may have been unable to spend several months in a City that took days to reach on horseback. On the other hand, we certainly know where Patrick Henry stood, and a large number of other abstentions from certain states suggests more than personal inconvenience was involved. After all, Rhode Island refused even to nominate anyone to the Delegation. In this last case, a political issue was highlighted. The Articles of Confederation which were being replaced not only required unanimous consent to change them, but they affirmed the Articles to be permanent. Under ordinary contract law, that would be dispositive. But George Washington was hell-bent on replacing the Articles of Confederation, so what they said would then no longer matter.

There remains a need for someone, perhaps in a doctoral thesis, to examine the voluminous correspondence and recollections of the large group of non-signers to assess the true nature of their failure to attend or sign. There was plenty of room for honest disagreement, personal business back at home, illness, or feelings of inadequacy. On the other hand, plenty of other subsequent politicians have exhibited an unwillingness to offend anyone, a hope to seek advantage from both sides, or a habitual tendency of waiting to see who would win before stating an opinion. Politics would be better without such personal inadequacies, but politics would not be politics without them. In fairness to their quandaries, the voting on the Constitution was by states, requiring nine to adopt it. If the vote of their state was a foregone conclusion, some delegates probably had a right to go home and let it happen in their absence. In the case of Alexander Hamilton, here stood the sole New York delegate in attendance at the final signing. Since he had been agitating for this sort of reform for seven years before Madison and Washington convinced each other, it seems possible that others withdrew to let him have the limelight. There is little doubt the single remaining responsibility of the signers was to go home and "deliver" their state for ratification, and Hamilton went at that with a vengeance. Although the moment of final signing appears on portraits and in sculpture, it was only the beginning of the battle for adoption, not the final victory. Indeed the Constitution as we now perceive it did not take more or less final form until the early government shaped its operation in actual practice. Most of that shaping process also took place in Philadelphia, during the first ten years while the seat of government was still located there. In particular, many if not most of the elected members of the First Congress had been members of the Constitutional Convention, returning to Philadelphia to finish the job by writing the Bill of Rights.

|

|

|

| |||||

|

||||||||

| Daniel Carroll |

|

| Charles Pinckney |

|

| Abraham Baldwin |

|

| John Langdon |

|

| Nicholas Gilman |

|

| Nathaniel Gorham |

|

| Rufus King |

|

| Rodger Sherman |

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

|

| David Brearly |

|

| Jonathan Dayton |

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

|

| Thomas Mifflin |

|

| Robert Morris |

|

| George Clymer |

|

| Thomas Fitzsimons |

|

| Governor Morris |

|

| William Houston |

|

| Caleb Strong |

|

| William Davie |

|

| Alexander Martin |

|

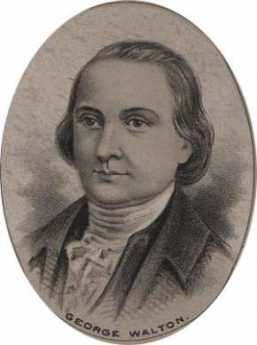

| George Walton |

|

| Charles Carroll |

|

| Gabriel Duvall |

|

| Thomas Stone |

|

| Francis Dana |

|

| Benjamin West |

|

| Abraham Clark |

|

| Richard Caswell |

|

| Willie Jones |

|

| Henry Laurens |

|

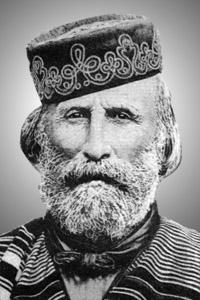

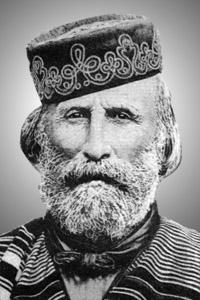

| Patrick Henry |

.jpg)

|

| Thomas Nelson |

The Schools of School House Lane

|

| Union School founded in 1759 |

The region of Philadelphia defined as Germantown is recorded by the last census as having about 50,000 inhabitants today, 40,000 of whom are of the black race. Germantown has always had an unusual concentration of schools of the highest quality, and here on one street alone there are four. School House Lane runs off to the West of Germantown Avenue, and was originally right at the center of town, the center of the action during the Revolutionary War. The most historic of the schools, the Union School founded in 1759, changed its name to Germantown Academy, and more recently picked up and moved to new quarters in Fort Washington. George Washington sent his nephew there, and its building served as a hospital for the wounded in the Battle of Germantown. When Germantown Academy moved out of Germantown, the Pennsylvania School for the Deaf moved into the vacated quarters. This school had been originally founded in 1820, and is one of nearly a hundred special schools for the deaf in the United States, operating as a quasi-public institution for about 170 students. A remarkable thing about all schools for the deaf is the high IQ of their students. Perhaps deaf underachievers are somehow filtered out by the struggle to adapt before they apply for admission, or perhaps there is something about being deaf that makes you smart. In any event, the average SAT scores of students from PSD, like all schools for the deaf, are always in the very highest ranks among secondary schools.

|

| Sklar School Entrance |

More or less next door to it, fronting on Coulter Street, is the Germantown Friends School(GFS), which enjoys and deserves the reputation of the most intellectually rigorous school in the Philadelphia region. There is little question about the Quakers of this school, founded in 1845, but relatively few of the students are now Quaker children. It's pretty expensive and quite uncompromising about its academic standards, but if you want to be accepted by a famous University, this is the place that can boast the most achievement of that variety. By no means all of its graduates become teachers, but alumni of this school do tend to gravitate to the top of academia. That could eventually put them on college admission committees, of course, and perhaps the admission process promotes itself. There can be little doubt that if most of a given college's admission committee happened to play the tuba, that university would soon fill up with tuba players.

|

| William Penn Charter School |

Further West on School House Lane, is the William Penn Charter School. It's also Quaker, and while it doesn't work quite so hard at it as GFS does, it has plenty of social mission, a great deal more discipline, and plenty of competitive athletics. A minority of its students, also, are Quakers; but as a guess, most of its graduates are headed for disproportionate affluence anyway. The middle school is named for, and was donated by, the former chairman of Morgan Stanley back before Morgan Stanley sold itself to Dean Witter. This school was founded in 1689, and for a long time was located at 12th and Market Streets in Philadelphia, right where the famous PSFS building was built, the one that later converted to Lowe's Hotel .

Finally, near the crossing of Henry Avenue with Schoolhouse Lane, is the Philadelphia University. Since it was founded in 1999 it is the youngest of the schools on School House Lane, specializing in architecture and design, and seems headed for even broader curriculum. The University was formed by the merger of Ravenhill Academy for Girls, and the Philadelphia Textile School. The Textile School was itself formed during the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, when local industrialists became concerned with how backward America seemed in its quality and design of textiles, compared with other nations which exhibited at that World's Fair. Next door, was once the home of William Weightman, a chemical manufacturer who was reputed to be the richest man in Pennsylvania. After his death, the rather grand estate became the site of the Ravenhill School for Girls, which was the school which could boast Grace Kelly for an alumna. That was natural enough since she lived just around the corner on Henry Avenue and could walk to school. The contrast between the two ends of School House Lane, Henry Avenue on one end, and Germantown Avenue on the other, is just astounding.

So there you have School House Lane. A few short blocks with three distinguished preparatory schools and a university. Plus, the site of three other famous schools which have either moved or merged. You might think Germantown was the home of myriads of school teachers, but that isn't exactly so. It's hard to say just what this complex anomalous situation proves, except to voice the opinion that it is somehow at the heart of what Philadelphia really is.

Note, kind readers have also sent me the names of six more schools on Schoolhouse Lane. Some of them may only be name changes, but the list includes Parkway Day School, Sklar School, Philadelphia Textile and Science, Germantown Stevens Academy, Germantown Lutheran Academy, Greene Street Friends School. (See Comments.)

For the Good of the Order

Although it has older origins, Roberts Rules of Order provide a place in every meeting for remarks "for the good of the order", suggesting there should always be an opportunity to deviate from strict germaneness to speak about something which is clearly worth talking about. Although meetings for business usually appoint a chairman, speaker or clerk to preserve order and germaneness, the truth is that most meetings which lose the opportunity to introduce something worthwhile which is a little off the subject, do so because of habit and tradition rather than devotion to focus. In recent years, remarks for the good of the Order have become so uncommon that speakers tend to rise on "a point of personal privilege", although provision for this had in mind birthday greetings and the like.

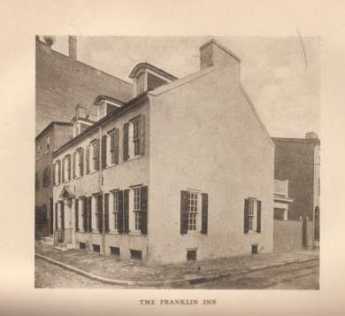

I suggest it might be a useful and entertaining thing to devote some meetings of the Franklin Inn to discussions of ways we could improve the club, and if the club has seemingly already reached perfection, to ways of improving Philadelphia and its Commonwealth.

|

| The Franklin Inn |

Such an effort will struggle at first, so it needs a core group to assure hesitating attendees that something worthwhile will be said. That core group may include officers and officials who are charged with running the club, the city or the state, but the opinions of the meeting should carry no enforcement powers other than their intrinsic validity. Admittedly, there is a natural restlessness of independent thinkers that their ideas should go somewhere, so the meetings should maintain minutes, perhaps on a website.

The attendees should pay for their lunches with meal tickets, but should also maintain a book of tickets for invited guests, and sell tickets to uninvited ones. If the present markup for tickets is maintained, an attendance of six regulars would sustain the invited speaker ticket book, and the attendance of six uninvited (no-club members) would make subsidy unnecessary. For the initial year, however, the club itself should subsidize speaker lunches. If there are conflicting meetings the Meetings for the Good of the Order should move to the second floor, and perhaps that is the best place for all of them.

These meetings should not fall into the trap of grieving that their innovative suggestions are not adopted, although they may be forgiven for celebrating the occasions where an idea does get implemented. The goal is to help an idea grow legs, and then watch it travel, ever mindful that much can be accomplished when we disregard who gets credit for it.

SEPTA's Long Term Planning

|

| Septa |

Byron S. Comati, the Director of Strategic Planning and Analysis for SEPTA (Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority), kindly gave the Right Angle Club an inside look at the hopes and plans of SEPTA for the near (five-year) future. Students of large organizations favor a five or six-year planning cycle as both short enough to be realistic, and long enough to expect to see tangible response. If plans continuously readjust to fit the five-year horizon, the concept is that the organization will move forward on these stepping stones, even accounting for setbacks, disappointments, and surprises. Furthermore, a serious level of continuous planning puts an organization in a position to react when funding opportunities arise, such as the sudden demand of the Obama Administration that economic stimulus proposals be "shovel ready."

|

| The Silverline V |

So, SEPTA is currently promoting five major expansions, based on the emerging success of an earlier plan, the Silverliner V. Silverline is a set of 120 shiny new cars, built in Korea on the model of electrical multiple units, which are expected in Spring 2011 to replace 73 cars or units which were built in 1963. Obviously, 120 are more expensive than 73, but they are more flexible as well. And less wasteful; most commuters are familiar with the model of three seats abreast which unfortunately conflict with the social preferences of the public, tending to make the car seem crowded even though it is a third empty. When a misjudgment like this is made, it takes fifty years to replace it with something better. For example, there's currently a movement toward "Green construction", which is acknowledged to be "a little bit more expensive". The actual costs and savings of green construction have yet to become firmly agreed on, so there's an advantage to being conservative about what's new and trendy in things that take fifty years to wear out.

|

| Septa Regional Map |

Four of SEPTA's five major proposed projects are in the Pennsylvania suburbs. New Jersey has its own transportation authority, and Philadelphia is thus left to struggle with the much higher costs of urban reconstruction assigned to its declining industrial population. And left unmentioned is the six hundred pound gorilla of the transportation costs of new casinos. A great many people are violently opposed to legalized gambling, and even more upset by the idea of crime emerging in the neighborhoods of gambling enterprises. Even the politicians who enacted this legislation are uncomfortable to see the rather large expenditures which will eat into the net revenue from this development. Nevertheless, if you are running a transportation system, you have an obligation to plan for every large shift in transportation patterns, no matter what you might think of the wisdom of the venture. The alternative is to face an inevitable storm of criticism if casinos come about, but without any preparation having been made for the transportation consequences. At present, the public transportation plan for the casinos is to organize a light rail line along the Delaware waterfront, connecting to the rest of the city through a spur line west up Market Street; it may go to 30th Street Station, or it may stop at City Hall. That sounds a lot like the present Market-Frankford line, so expect some resistance when the cost estimates are revealed. Because all merchants want to have the station stops near them, and almost no residents want a lot of casino foot-traffic near their homes and schools, expect an outcry from those directions, as well. It would be nice to integrate this activity with something which would revive the river wards, but it seems a long stretch to connect with Wilmington on the south, or Trenton on the north.

The planned expansions in the suburban Pennsylvania counties will probably encounter less controversy, although it is the sorry fate of all transportation officials to endure some hostility and criticism for any changes whatever. Generally speaking, the four extensions follow a similar pattern of building along old or abandoned rail lines, following rather than leading the population migrations of the past. When you are organizing mass transit, there is a need to foresee with some certainty that there will be a net increase in commuters in the region under consideration. The one and two passenger automobile is a much more flexible instrument for adjusting to the growth of new development, schools, retail, and industry. Once the region has become established, there is room for an argument that transportation in larger bulk is cheaper, cleaner or whatever.

The Norristown extension follows the existing but underused rail connections to Reading. Route US 422 opened up the region formerly serving the anthracite industry, but now the clamor is rising that US 422 is impossibly crowded and needs to be supplemented with mass transit.

The Quakertown extension follows the rail route abandoned in 1980 to Bethlehem and Allentown, although the extension is only planned as far as Shelly, PA.

The Norristown high-speed extension responds to the almost total lack of public transportation to the King of Prussia shopping center, and will possibly replace the light rail connection to downtown Philadelphia.

And the Paoli extension follows the mainline Amtrak rails as far as Coatesville.

All of these expansions can expect to be greeted with huzzahs by developers, land speculators, and newsmedia, but resistance will inevitably be as fierce as it always is. Local business always fears an expansion of its competitors; the feeling is stronger in the suburbs than the city, but local business always resists and local politicians always follow their lead. To some extent, the suburbs have a point, since radial extensions are usually much cheaper to build than lateral or circumferential transportation media; bus routes are the favored pioneers in connecting one suburb with another. Therefore, the tendency in these present plans remains typical by threatening the suburbs with a need to travel toward the center hub, then take a reverse branch back in the general direction of where they started, in order to go a short distance to a shopping center or school system. The two main river systems around Philadelphia interfere with the construction of big "X" routes from the far distance in one direction to the far distance in the opposite direction. Euclidian geometry makes the circumferential route elongate as the square of the radius. And jealousies between the politicians in three states create rally foci for the special local interests which feel injured. Since it seems to be an established fact that the proportional contribution to mass transportation by the surrounding suburbs of Philadelphia is traditionally (and considerably) lower than the national average, a political reconciliation might do more for the finances of SEPTA than any federal stimulus package could do. For such reconciliation, a few lateral connections in the net might pacify the suburbs enough to justify the extra cost. Unfortunately, the main source of unjustified cost in regional mass transit is the high wage and benefit levels of the employees, a situation inherited from the old days when commuter rail was part of the stockholder-owned regional railroads. Just as featherbedding was the main cause of the destruction of the mainline railroads, health and pension benefits threaten the life of mass transit. In the old days, local governments acted as a megaphone for union demands. So the railroads just gave the commuter system to the local governments, and let them wrestle with the unions themselves. Since the survival of the urban region depends on conquering this financial drain, the problem must be gradually worn down. But it has been remarkable how long the region has been willing to flirt with bankruptcy rather than bite this bullet.

If anything, this friction threatens to get worse. In 2009, for the first time, a majority of union members in America -- work for the government, the one industry which thinks it cannot be destroyed by losing money. True, SEPTA is not exactly a government function, but it has enough in common with a government department to arouse suburban voters, who regularly refer to it as an arm of the urban political machine. SEPTA isn't too big to fail, but there exists little doubt that government at some level would probably try to bail it out if it did.

Funny Toes: A Physician Viewpoint

|

| Webbed Toes |

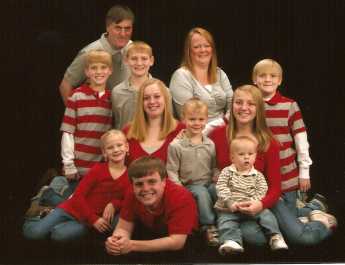

It probably took me twenty years to notice that, unlike most people, I had an incomplete separation of my second and third toes. I thought my toes were like everybody else's, but once you start peeking, you see that webbed toes are not normal, although they are not really rare, either. After another thirty years, it became apparent that most of my numerous descendants had the same kind of toe; it was obviously an inherited condition. When the family clan gathered at the beach, it was a source of mild amusement, possibly even a little pride. A few weeks ago, I happened to mention the matter at a party, whereupon another doctor promptly pulled off his shoes and socks, and revealed fused or webbed toes of a much more striking sort than mine; obviously, he was proud of it, too. He is of an old, old Philadelphia family that owns one of the oldest, if not the oldest, a house in Germantown. His family, too, is stigmatized in the same way only more so. In Philadelphia, when you are proud of your family, you are really, really, proud of it.

|

| Ainhum |

Which brings me back to my days as an intern in the accident room of the Pennsylvania Hospital. When there is a sudden crowd of emergencies in an emergency department, the nurses get all of them undressed, put in a hospital gown, and instructed to wait for the doctor behind a curtain that doesn't quite reach the floor. For some reason, as a medical student, I had been particularly struck by a photograph in a textbook of an inherited disorder said to have been first noted on a slave ship; the disease in the native language was named Ainhum. For reasons obscure, a tight little band appears at the base of the fifth, or little, too. It gets slowly tighter over a period of months, and eventually, the little toe falls off. That's all there is to Aihnum, and all that was known about it. So, imagine my surprise and delight to walk past a row of naked feet sticking out below curtains -- and there was my first and last case of Aihnum.

I summoned my colleagues, and the visiting medical students from both Jefferson and Penn who at that time shared training in our accident room. I raced off to my room to get a camera to record this momentous event. An elderly staff physician, either Tom McMillan or Charles Hatfield, wandered past and was invited to share the excitement. Well, he says, I saw one of those forty years ago, it looked just like that; old Doctor Norris showed it to me when I was an intern. Much murmuring ensued but abruptly stopped when the patient himself rose up and started putting on his clothes. He was going home, but why? "Well," he growled, "I came here because my back hurts, and all you people do is look at my toes!" He said he was going over to the Jefferson Hospital to get proper treatment, and I guess he did.

And finally, there is Morton's Toe. Or perhaps more properly, Mortons' Toes. There were in fact two Doctor Mortons, one of them at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons where I went to school, and the other at the Pennsylvania Hospital where I interned. In New York, Morton's Toe refers to a painful callous, or neuroma, that forms on the bottom of the victim's big toe. In Philadelphia, such an answer would get a failing grade, because the Philadelphia Morton had noticed that some people have a big toe that is shorter than the other toes, instead of being bigger as the term would suggest was proper. The tricky thing about this relatively harmless variant is that the big toe is actually not short at all. The foot bone, or metatarsal, is short, so the toe of normal length sits back farther on the foot and just looks shorter. The main significance is for shoe salesmen since the shoe needs to be long enough to avoid crushing the other toes.

So now, you readers who were not lucky enough to go to medical school can get a feeling for what it seems like to be a doctor. The other significant shared bond within the fraternity is a sense of outrage at the way health insurance companies drag their feet paying doctors, but that's not limited to feet..

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

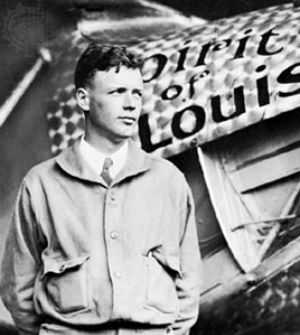

| Spirit of 76' |

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

Northwest Ordinance of July 13, 1787: Articles of Confederation at their Best

COMING across the term "Northwest Territory" for the first time, modern students can easily confuse it with the states of Washington and Oregon, more precisely called the Pacific Northwest, thousands of miles to the west. The United States acquired this more eastern Territory from the British -- bounded on the south by the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers below Canada, and West of the Appalachian Mountains -- at the second Treaty of Paris which ended the Revolutionary War in 1783. Before that, the British had acquired it from the French at the first Treaty of Paris, ending the French and Indian War in 1763. Until the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, this land really was the Northwestern tip of American possession, even though it is less than half-way between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It was occupied by Indian tribes who much preferred dealing with wandering British fur traders, to the new threat of permanent occupation by American settler families. In part, bloody warfare with the Shawnee Indians under Tecumseh did somewhat justify the reluctance of the British to give up their chain of forts in Indian Territory friendly to them, but rapid immigration to America from Europe after the end of the war soon generated great westward pressure for settlers to move there. In general, these new immigrants were neither military veterans nor experienced woodsmen and suffered several large massacres from Indians whose homelands were threatened. The Northwest Territory was a dangerous place for unseasoned settlers at the end of the Eighteenth century.

Consequently, it required four years for the new Republic to decide how to handle this sudden expansion of territory it must govern. The question of excluding slavery had already come up, along with the puzzle of managing the masses of raw European immigrants as they encountered and outraged the native Indians. Furthermore, a military alliance, which is what the Articles of Confederation amounted to, is an awkward vehicle for governing an expanding frontier wilderness, especially while it was experimenting with new forms of governance. For one thing, joint ownership by thirteen sovereignties seemed almost certain to tempt one or two of them to take it all over, provoking interstate war and possibly endless disputes between former friends. Most observers in retrospect regard the Northwest Ordinance of the Confederation Congress to be a sensible and workable product, which happened to be just about the last major act of that political body. The Constitutional Convention overlapped it.

|

| Before the French and Indian War. |

The Ordinance under the Articles of Confederation was ratified on July 13, 1787, whereas the Constitutional Convention was in session from May 14 to September 17, 1787. No doubt a smooth transition between the two was under discussion, although the Confederation Congress was an itinerant body, always struggling to produce a quorum and a place to meet. Judging from their behavior after the Constitution was ratified, some undefined proportion of the Confederation Congress may have continued to harbor States Rights resentments at being displaced by a new nationalist government. At the very least, it would only be natural for some of the Congress to be offended that Washington failed to endorse them for the Constitutional Convention. Following that, the advocates of Constitutional ratification were then fairly careless in denouncing the inadequacy of the Articles by citing the failures of the Confederation Congress as examples of it.

The Northwest Ordinance provided for a military government until a civilian one could establish itself. Conquering armies are quite accustomed to the rough uncertainties of keeping a hostile territory subdued while a declared enemy is relentlessly dealt with under a different set of rules. The Congress (soon amended to substitute the President) was to appoint temporary governors and panels of judges. A provisional civilian government was added as soon as five thousand male settlers (each owning fifty acres of land) were resident, and that provisional government was to help devise a state constitution and set of laws as soon as sixty thousand such settlers were resident. The Ordinance allowed the territory to be divided between three to five states, but the borders of five states were laid out from the start. At first, this discordance between laying out the inflexible boundaries for five states, and at the same time allowing for a variable number of states, seems careless to later generations. But the Congress had no idea how fast different states would fill with settlers but assumed it was likely it would fill from East to West. They thus laid out the ghost outlines of five states within the territory, detaching statehoods as the minimum population filled them up.

A carefully planned, three-step progression (from the military, to provisional, to statehood) turned out to be an excellent expedient for managing other new states created by an expanding frontier throughout the Nineteenth century. Those who today complain that the bicameral Legislative branch is implausible, are not merely disregarding the vital need at the Constitutional Convention for a compromise between the large and small states in a Union of three big with ten small. They must also recognize that the frontier would probably expand by acquiring lightly inhabited land and breaking it up into states, followed by immigration from the edges. Many states were destined to begin with small populations, and grow to have big ones. To maintain strict adherence to population limits for new states would probably result in peculiarly-shaped, but densely populated, states on the edges, possibly in large numbers, along with endless quarrels about suspected gerrymandering of the Senate. It may not be an accident that Elbridge Gerry, the namesake of Gerrymandering, was on the committee devising this Ordnance. The U.S. Senate has long been proud of its immunity to gerrymandering, contrasted with the evils the process regularly imposes on the House of Representatives. The Great Compromise of a bicameral legislature, giving equal Senate power to many small states, but House of Representative power to a few big ones, was only weeks from being struck; there may be some connection, here. Although the balance continually shifts, the generalization is still true that America is a Union of a few big states and many small ones. Seemingly, the election rules are not likely to change substantially. Eliminating the Electoral College, much grumbled by the big states is thus also, forever unlikely.

|

| The Varsity Comes Onto the Field |

It seems useful to point out the practical utility of defining citizens who "live" in a district, as being those who probably own land there. The Northwest Territory was a vast expanse of wilderness, much of which soon become the most valuable farmland in the world, with topsoil two feet thick. The rules of this land rush were that it was to be governed by Federal troops until there were five thousand male settlers, presumably the minimum sufficient to defend against hostile Indians. However, the assumption of political power, along with its ability to set the rules, offered a temptation to find ways of making the number unreasonably easy to reach or temporarily composed of a particular political group. Demanding that eligible citizens must each own a liveable plot of farmland probably seemed wise precaution against carpet-bag "voters" being temporarily imported for the voting. A similar provision was soon included in the Constitution, although that is often held up by partisan writers as proof of aristocratic leanings among the Constitutional Framers. With land selling for fifteen cents an acre, it seems more likely it was a practical test of genuine residence, the Eighteenth century equivalent of presenting a driver's license as identification at the polling booth. In both instances, those suspected of impersonating local voters pretend to the great offense at the voicing of any suspicion of it.

The Northwest Territory eventually became Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, and Wisconsin, plus a part of Minnesota. The dynamics of migration took unexpected turns. Although Ohio was the seventeenth state, admitted in 1803, Wisconsin was the thirtieth, waiting until 1848 for admission to statehood. For a while, a settlement was more rapidly toward the South, and near the region of the Louisiana Purchase. The Northwest Ordinance was in force without major amendment for almost fifty years.

Part of its durability can be traced to the prohibition of slavery in the Northwest Territory. The existing Southern states were remarkably peaceful about agreeing to slavery prohibition, a reaction said to arise from tobacco growing southern states indifferent to competition to their main crop, from areas with presumably higher labor costs. When the main crop soon turned from tobacco to cotton, the anti-competitive argument apparently had less force. One cannot contemplate the horrendous impending casualties of the Civil War without wondering if massaging of the competition argument might have been put to more imaginative use during the forty-year interval of free soil agitations. Unfortunately, since politicians did not appreciate the price they were about to pay for a policy of drift, they obstructed the (probably) much smaller costs of facing the issue sooner.

Political Parties, Absent and Unmentionable

|

| King George III |

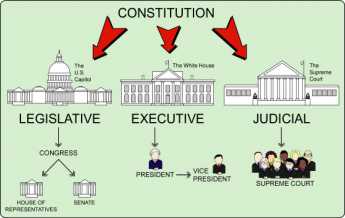

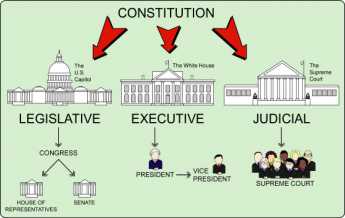

BECAUSE America had recently revolted to rid itself of King George III, the Constitutional framers of 1787 sought to construct a government forever free from one-man rule. Inefficiency could be accepted but central dictatorial power, never. It is unrealistic however to expect a wind-up toy to keep working forever, and our Constitution creates the same worry. After two centuries, some chinks have appeared.

|

| Founding Fathers |

Political parties existed in 18th Century England and Europe, but the American founding fathers seem not to have worried about them much. Within ten years of Constitutional ratification, however, Thomas Jefferson had created a really partisan party which naturally provoked the creation of its partisan opposite. James Madison was slowly won over to the idea this was inevitable, but George Washington never budged. Although they were once firm friends, when Madison's partisan position became clear to him, Washington essentially never spoke to him again. Andrew Jackson, with the guidance of Martin van Buren, carried the partisan idea much further toward its modern characteristics, but it was the two Roosevelts who most fully tested the U.S. Supreme Court's tolerance for concentrating new powers in the Presidency, and Obama who recognized that the quickest way to strengthen the Presidency was to weaken the Legislative branch.

Dramatic episodes of this history are not central to present concerns, which focuses more on the largely unnoticed accumulations of small changes which bring us to our present position. Wars and economic crises induced several presidents, nearly as many Republicans as Democrats, to encourage migrations of power advantage which never quite returned to baseline after each crisis. Primary among these migrations was the erosion of the original assumption of perfect equality among individual members of Congress. A new member of Congress today may tell his constituents he will represent them ably, but when he arrives for work he is figuratively given an office in the basement and allowed to sit on empty packing cases. This is not accidental; the slights are intentional warnings from the true masters of power to bumptious new egotists, they will get nothing in their new environment unless they earn it. Not a bad idea? This schoolyard bullying is a very bad idea. If your elected representative is less powerful, you are less powerful.

|

| Houses of Congress |

Partisan politics begins with vote-swapping, evolves into a system of concentrating the votes of the members into the hands of party leaders, and ultimately creates the potential for declaring betrayal if the member votes his own mind in defiance of the leader. The rules of the "body" are adopted within moments of the first opening gavel, but they took centuries to evolve and will only significantly change direction on those few occasions when newcomers overpower the old-timers, and only then if some rebel among the old timers takes the considerable trouble to help organize them. In the vast majority of cases, after adoption, the opportunity to change the rules is then effectively lost for two years. Even the Senate, with six-year staggered terms, has argued that it is a "continuing body" and need not reconsider its rules except in the face of a serious uprising on some particular point. Both houses of Congress place great weight on seniority, for the very good purpose of training unfamiliar newcomers in obscure topics, and for the very bad purpose of concentrating power in "safe" districts where party leaders are able to exercise iron control of the nominating process. Those invisible bosses back home in the district, able to control nominations in safe districts, are the real powers in Congress. They indirectly control the offices and chairmanships which accumulate seniority in Congress; anyone who desires to control Congress must control the local political bosses, few of whom ever stand for election to any office if they can avoid it. In most states, the number of safe districts is a function of controlling the gerrymandering process, which takes place every ten years after a census. Therefore, in most states, it is possible to predict the politics of the whole state for a decade, by merely knowing the outcome of the redistricting. The rules for selecting members of the redistricting committee in the state legislatures are quite arcane and almost unbelievably subtle. An inquiring newsman who tries to compile a fifty-state table of the redistricting rules would spend several months doing it, and miss the essential points in a significant number of cases. The newspapers who attempt to pry out the facts of gerrymandering are easily gulled into the misleading belief that a good district is one which is round and compact, leading to a front-page picture showing all districts to be the same physical size. In fact, a good district is one where both parties have a reasonable chance to win, depending for a change, on the quality of their nominee.

So that's how the "Will of Congress" is supposed to work, but the process recently has been far less commendable, and in fact, calls into dispute the whole idea of a balance of power between the three branches of government. We here concentrate on the Health Reform Bill ("Obamacare") and the Financial Reform Bill ("Dodd-Frank"), which send the same procedural message even though they differ widely in their central topic. At the moment, neither of these important pieces of legislation has been fully subject to judicial review, so the U.S. Supreme Court has not yet encumbered itself with stare decisis of its own creation.

|

| Three branches of government |

In both cases, bills of several thousand pages each were first written by persons who if not unknown, are largely unidentified. It is thus not yet possible to determine whether the authors were affiliated with the Executive Branch or the Legislative one; it is not even possible to be sure they were either elected or appointed to their positions. From all appearances, however, they met and organized their work fairly exclusively within the oversight of the Executive Branch. Some weighty members of the majority party in Congress must have had some involvement, but it seems a near certainty that no members of the minority party were included, and even comparatively few members of highly contested districts, the so-called "Blue Dogs" of the majority party. It seems safe to conjecture that a substantial number either represent special interest affiliates or else party faithful from safe districts with seniority. The construction of the massive legislation was conducted in such secrecy that even the sympathetic members of the press were excluded, and it would not be surprising to learn that no person alive had read the whole bill carefully before it was "sent" to Congress. It's fair to surmise that no member of Congress except a few limited members of the power elite of the majority party were allowed to read more than scattered fragments of the pending legislation in time to make meaningful changes.

The next step was probably more carefully managed. No matter who wrote it or what it said, a majority of the relevant committees of both houses of Congress had to sign their names as responsible for approving it. Because of the relatively new phenomenon of live national televising of committee procedure, the nation was treated to the sight of congressmen of both parties howling that they were only given a single day to read several thousand pages of previously secret material -- before being forced to sign approval of it by application of unmentioned pressures enabled by the rules of "the body". When party members in contested districts protested that they would be dis-elected for doing so, it does not take much imagination to surmise that they were offered various appointive offices within the bureaucracy as a consolation. As it turned out, the legislation was only passed narrowly on a straight-party vote, so there can be a considerable possibility of its likely failure if the corruptions of politics had been set aside, with members voting on the merits. Nevertheless, since this degree of political hammering did result in a straight-party vote, it leaves the minority party free to overturn the legislation when it can. The prospect of preventing an overturn in succeeding congresses seems to be premised on "fixing" flaws in the legislation through the issuance of regulations before elections can open the way to overturn of the underlying authorization. Legislative overturn, however, is very likely to encounter filibuster in the Senate, which presently requires 40 votes. Even that conventional pathway is booby-trapped in the case of the Dodd-Frank Law. The Economist magazine of London assigned a reporter to read the entire act, and relates that almost every page of it mandates that the Executive Branch ("The Secretary shall") must take rather vague instructions to write regulations five or ten times as long as the Congressional authorization, giving the specifics of the law. The prospect looms of vast numbers of regulations with the force of law but written by the executive branch, emerging long after the Supreme Court considers the central points, years after the authorizing congressmen have had a chance to read it, and well after the public has rendered final judgment with a presidential election. The underlying principle of this legislation is the hope that it will later seem too disruptive to change a law, even though most of it was never considered by the public or its representatives.

|

| Bill become a Law |

The "regulatory process" takes place entirely within the Executive branch. Congress passes what it terms "enabling" legislation, containing language to the effect that the Cabinet Secretary shall investigate as needed, decide as needed, and implement as needed, such regulations as shall be needed to carry out the "Will" of Congress. Since the regulations for two-thousand-page bills will almost certainly run to twenty thousand pages of regulations with the force of law, the enabling committee of Congress will be confronted with an impossible task of oversight, and thus will offer few objections. The Appropriations Committees of Congress, on the other hand, are charged with reviewing every government program every year and have the power to throttle what they disapprove of, by the simple mechanism of cutting off the program's funds. Members of the coveted Appropriations Committees are appointed by seniority, come from safe districts, and are attracted to the work by the associated ability to bestow plums on their home districts. By the nature of their appointment process, unworried by the folks back home but entirely beholden to the party bosses, they have the latitude to throttle anything the leadership of their party wants to throttle badly enough. The outcome of such take-no-prisoners warfare is not likely to improve the welfare of the nation, and therefore it is rare that partisan politics are allowed to go so far.

The three branches of government have become unbalanced. These bills were almost entirely written outside of the Legislative branch, and the ensuing regulations will be written in the Executive branch. The founding fathers certainly never envisioned that sweeping modification will be made in the medical industry and the financial industry, against the wishes of these industries, and in any event without convincing proof that the public is in favor. This is what is fundamentally wrong about taking such important decisions out of the hands of Congress; it threatens to put the public at odds with its government.

|

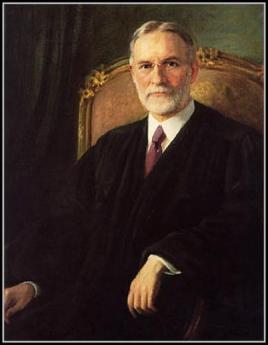

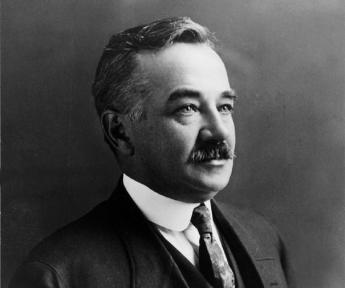

| Justice George Sutherland |

There is no need to go further than this, harsher words will only inflame the reaction further than necessary to justify a pull-back. And yet, the Supreme Court would do us mercy if it doused these flames; the Supreme Court needs a legal pretext. May we suggest that Justice George Sutherland, who sat on the court seventy years ago, may have sensed the direction of things, short of using a particular word. Justice Sutherland recognized that although it is impractical to waver from the principle that ignorance of the law is no excuse, it is entirely possible for a person of ordinary understanding to read law in its entirety and still be confused as to its intent. He thus created a legal principle that a law may be void if it is too vague to be understood. In particular, a common criminal may be even less able to make a serious analysis. Therefore, at least in criminal cases, a lawyer may well be void for vagueness. In this case, we are not speaking of criminals as defendants or civil cases of alleged damage of one party by a defendant. Here, it is the law itself which gives offense by its vagueness, and Congress which created the vagueness is the defendant. Since we have just gone to considerable length to describe the manner in which Congress is possibly the main victim, this situation may be one of the few remaining ones where a Court of Equity is needed. That is, an obvious wrong needs to be corrected, but no statute seems to cover the matter. The Supreme Court might give some thought to convening itself as a special Court of Equity, on the special point of whether this legislation is void for vagueness.

We indicated earlier that one word was missing in this bill of particulars. That would be needed, to expand the charge to void for intentional vagueness, an assessment which is unflinchingly direct. It suggests that somewhere in at least this year's contentious processes, either the Executive Branch or the officers of the congressional majority party, or both, intended to achieve the latitude of imprecision, that is, to do as it pleased. Anyone who supposes the general run of congressmen voluntarily surrendered such latitude in the Health and Finance legislation, has not been watching much television. Given the present vast quantity of annually proposed legislation, roughly 25,000 bills each session, the passage of a small amount of vague legislation might only justify voiding individual laws, whereas an undue amount of it might additionally justify a reprimand. However, engineering laws which are deliberately vague might rise to the level of impeachment.

Cost of Medical Care

|

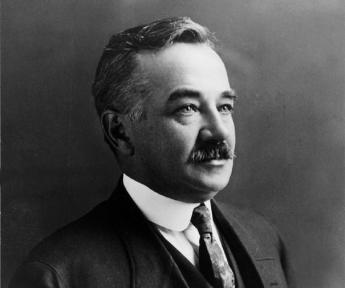

| Milton S. Hershey |

On several occasions, Richard A. Kern M.D. (1891-1982) told the story of his part in the founding of the Hershey School of Medicine. Dick Kern was a distinguished professor of Medicine at Temple University, well known for his contributions in the field of asthma and allergy, a past president of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia, and a former Grand Master of Pennsylvania Freemasonry. The Milton S. Hershey School was considering the creation of a medical school and needed advice.

Milton Hershey had been a strict Mennonite, which is closely related to Quakerism, and had accumulated a huge fortune making chocolate candy. He left generous trusts to endow a theater and various other public services in the town of Hershey, but his ownership shares in the chocolate company had been left to the Hershey School for orphans. The value of the shares had far outgrown the ability of the school to employ them usefully, and they were considering a medical school. In 1963, as at present, everybody else was wondering how to get out from under the crushing cost of running a medical school. The sudden inquiry from a donor both willing and able to start a whole new medical school from scratch was an opportunity not likely to appear again soon. Kern carefully considered the options, including the danger of scaring off the naive potential donors with too high a price. Finally, he screwed up his courage and suggested a price to the trustees, of fifty million. The prompt answer was, done, you've got your medical school.

In due course, Kern found himself on the platform at the inaugural ceremonies of the school, sitting next to the guest of honor, that man who had made such an instant decision. Chatting amiably, Kern mentioned that he had always wondered how high the Hershey Foundation would have been willing to go. The answer was just as prompt as the original one. "Hundred-twenty."

A Change of Era