5 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

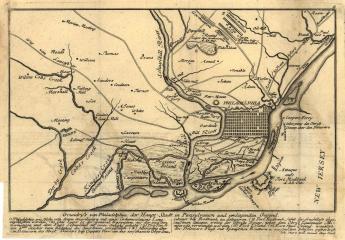

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Nineteenth Century Philadelphia 1801-1928 (III)

At the beginning of our country Philadelphia was the central city in America.

Colonial Philadelphia (Pre- 1776)

It's surprising to most Americans to learn the American Revolution was not the beginning, but almost half-way through the European settlement. And before the Revolution, there were thousands of years of settlement by non-European tribes. We know more about non-European settlers than we did fifty years ago, but records are still very poor or non-existent, and not likely to catch up very rapidly. History will begin in 1492 for a very long time. Long before that, it isn't history, it's anthropology.

It's surprising to most Americans to learn the American Revolution was not the beginning, but almost half-way through the European settlement. And before the Revolution, there were thousands of years of settlement by non-European tribes. We know more about non-European settlers than we did fifty years ago, but records are still very poor or non-existent, and not likely to catch up very rapidly. History will begin in 1492 for a very long time. Long before that, it isn't history, it's anthropology.

Unalienable Rights Before 1776

|

| Magna Carta |

In 1976, the bicentennial birthday celebration of the Declaration of Independence contained two major exhibits of its conceptual origins. Mr. H. Ross Perot of Texas loaned his copy of the 1215 Magna Carta, and the Proprietors of West Jersey loaned their 1677 original of William Penn's Concessions and Agreements to the colonists of New Jersey. The purpose of the exhibit was to emphasize the historical origins of the concepts within the Declaration, but even the language of the Concessions is remarkably similar, quite evidently lifted by Jefferson when he was writing. On one point, Penn had the better of Jefferson; he correctly wrote about inalienable rights, while somehow Jefferson gave us unalienable ones.

|

| William Penn |

The matter came up recently at a Socrates meeting of the Right Angle Club, where at least one member felt there was no such thing as a natural right, while others wavered. In discussing the rights which the Creator, William Penn and/or Thomas Jefferson may have given us, the various contexts must be held in mind. At the time of declaring our intention to sever relations with Britain's King, there was no Constitution to refer to as a source, and it was impolitic to assert the rights had been given by English kings, like King John. Therefore, the language cleverly short-cuts around the divine right of kings to make a direct connection between the Creator and the colonists. William Penn on the other hand, was a real estate promoter, offering enticements and assurances to prospective colonists who were naturally fearful of risking their lives in sailboats, only to face the possible tyranny of a vassal king who might be even worse than the anointed one. Not only did Penn renounce any suggestion of a Royal role for himself, but went to considerable length describing the legally binding concessions and agreements he was offering. The right of trial by jury, for example, became a right to be punished only by a jury of twelve of one's neighbors. He wasn't talking to lawyers, he was making important distinctions very clear to laymen. These were not rights given by a Divinity who could be trusted, nor something which grew out of Mother Nature. They were the personal promises of William Penn, in personal legal jeopardy of the English courts if he reneged on them. He even had a ready answer for those who discovered the religious language in legal documents -- the Quaker belief that, occasional appearances to the contrary notwithstanding, There is That of God, in every man.

|

| H. Ross Perot |

As a small sidelight of the Concessions document, it had long been housed in the little brick hut on Main Street in Burlington NJ, where the Proprietors of West Jersey keep their treasures. The obscurity of these papers was probably their best protection, but the risk of displaying them in Philadelphia at the centennial brought out the need to ensure them, hence to appraise their value. The figure of four million dollars was kicked around. Ross Perot might have felt comfortable with this sort of expense as the natural cost of being a rare book collector, but it seemed highly unnatural to Quakers. Sometime afterward, the Surveyor General, William Taylor, was awakened by a call from Burlington neighbors that someone was trying to break in the roof to steal contents of the Proprietorship building. The burglars were unaware that underneath the shingles, the roof was actually made of concrete a foot thick. So the perps were frustrated in their aims, but Bill Taylor was greatly troubled by the implications, actually unable to sleep at night worrying about what was in his custody. So, in time the State of New Jersey constructed a suitable archives building, and the valuable documents were transferred up to Trenton. Time will tell what the Soprano State does with such a valuable possession, but at least the Quakers can now sleep at night.

Houses of the Penn Family

|

| Jordan Meetinghouse |

The name Penn seems to be derived from the Welsh name for hill; hills are abundant in Wales. There is a reason to suppose the family was of royal descent. William's birthplace is now disputed, possibly in London near the Tower, possibly in Ireland at Sharry Estate, possibly the Church of All Hallows, Barking, England. Much better known and much-visited is Jordans, the place where he is buried in the simple buying ground of the Jordans Meeting House in Buckinghamshire, on a by-road running between Chalfont St. Peter and Beaconsfield. The present grave markers were added later since early Friends generally declined to have their names on tombstones. He lived most of his life and actually died in the family estate in Berkshire called Ruscombe where he had usually attended Friends Meeting in nearby Reading. At the time of his death, his fortunes were much reduced, having been betrayed by his steward Ford, and imprisoned for nine months.

|

| Slate Roof House |

When he lived in Philadelphia, William lived in the "Slate Roof House" on Second, between Chestnut and Walnut (a small park commemorates the building lot), and the Letitia Street House. His plans originally were to build a manor house where the Art Museum stands today, on Faire Mount, but somehow he changed his mind and moved to Pennsbury on the Delaware River near Trenton. This manor also did not survive, but its careful restoration is now well worth a visit.

|

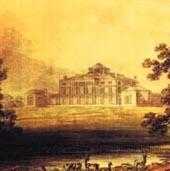

| Horticultural Hall |

William Penn had thirteen children, a circumstance adding much difficulty for genealogists. John Penn, the nephew of William's son Thomas, was the grandson who acted as Proprietary Agent and Governor prior to the American Revolution, although Thomas remained in London as a close friend of the King, and exercised firm control of the policies of the Proprietorship. John built a fine mansion on the Schuylkill called Lansdowne at the site of what was to become Horticultural Hall in the 1876 Centennial. About all that can now be visited is the glen on the estate, over which a bridge is still usable. It was here that he was apprehended by Revolutionaries, and taken to house arrest in New Jersey.

|

| Solitude House |

Lansdowne burned in the early 19th Century and pictures of it are hard to find. A smaller house of John Penn's, called Solitude, still stands near what is now the Zoo. John was arrested by rebel troops while living at Lansdowne and held prisoner at another house confusingly called Solitude, on the grounds of what became Union Forge, later the Union Forge Ironworks, subsequently the Taylor Iron and Steel Company. All of this is located in High Bridge, New Jersey, where subsequently five generations of the Taylor family lived until 1938. The Union Forge Heritage Association/Solitude House Museum welcomes visitors.

|

| Stoke Mansion |

A different John Penn, who called himself John Penn of Stoke, inherited a much larger portion of the final payment for the Proprietorship lands in Pennsylvania in 1789 because he was the son rather than the nephew of Thomas Penn. Thomas had purchased the historic Manor House in Stoke Poges in England. Although this splendid palace dated back to 1066 and Elizabeth I had visited it, it was by 1790 so dilapidated that John Penn demolished three-quarters of it. In its place, he built a proper palace, called Stoke Park. The family fortunes seem to have declined after that, perhaps because of the extravagance of an estate he could not afford.

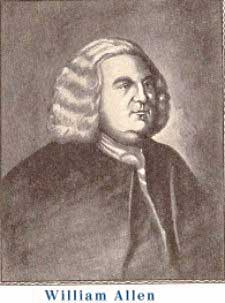

William Allen, Tory

|

| William Allen |

William Allen was once famous for his expensive carriage and a team of horses, at a time when there were only eighty carriages in the colony. He was born wealthy but personally made considerable sums in maritime trade, which in those days included a mild form of piracy called privateering. Taking his accumulated wealth, he invested heavily in colonial real estate. His urban ventures included the land under Independence Hall, and his lands in the hinterland included the present town of Easton. He was a tough businessman, providing "muscle" where needed in a colony dominated by pacifist Quakers. At one point, he imported a thousand muskets and ammunition for the use of settlers in the Lehigh Valley who had difficulties with the Indians and Connecticut invaders. Allentown is named after him.

|

| Philadelphia Lawyer |

It is difficult to apply present standards of judgment to Allen. William Penn had been given the colony on condition that he protect and maintain it. That was clearly a difficult challenge for a Quaker colony in the wilderness, surrounded by Indians, French and Spanish buccaneers, and neighboring colonies who were far from pacifist themselves. The system often amounted to giving land to subcontractors like Allen, on condition that they maintain law and order. Furthermore, Allen was quite obviously a person of parts. His credentials as Chief Justice were based on his attendance at the Inns of Court when almost all other lawyers were trained by local apprenticeships. His father in law was Andrew Hamilton, the famous "Philadelphia lawyer" who won the landmark case for Peter Zenger and later became the leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly and mentor to young Benjamin Franklin. His land-dispute services in the negotiations with Lord Baltimore were notable. In general, he was a continuing force for peace and stability, and no one held it against him that peace and stability suited his needs as a landlord and merchant. To him, the battle for independence was just another unsettling disturbance which prevented the colony from achieving its potential.

His daughter married John Penn, the grandson of William Penn, who was the local representative of the Proprietors and later the Governor. All in all, it is not surprising that he retreated to his home on Germantown Avenue, called Mt. Airy, when the revolution broke out. Unlike many other Tories who fled to Canada, he felt his past services would protect him if he remained quiet and secluded until the war was over. He didn't quite make it, dying in his mansion, in 1780.

Christ Church and Elfreths Alley

|

| Elthreths Alley |

The north side of Dock Creek (now, Dock Street) was lower than Society Hillside and somewhat swampy. The tendency to flood caused the north side to have smaller and less permanent buildings, and so it became the Colonial waterfront area remaining more commercial, and in parts, shabby, even during the 19th Century. Still further to the north, this was not the case, but the waterfront and food market patch more or less marooned Christ Church, now the single most graceful and elegant Colonial building still standing. This formerly commercial area is now called Old City, with many loft apartments mixed among surviving warehouse outlets, and of course the ethnic restaurants characteristic of such gentrified areas.

|

| Christ Church |

Elfreth's Alley, running for one block east and west between Second and Front (1st) Streets. Some of the histories of this street is obscure, so some of it is probably synthetic because nothing particularly historic happened there to create detailed records. Elfreth's Alley claims to be the oldest street in America, a claim that can be substantiated back to 1702. The street is filled with little "workers houses", presenting a solid front of buildings on both sides of the cobblestoned street. Most of the houses could vaguely be called "father, son and holy ghost houses", looking as though they consisted of three rooms on top of each other, although in fact most of them are larger. A moment's consideration shows that the street consists of many double houses, with three doorways in front. Each house had a door to the interior, and most of them have a third door opening to a shared tunnel between the two houses, leading to the back yards. These tunnels were called "easements", a term that has migrated from its earlier usage. Although William Penn envisioned large single estates in his "Greene Country Towne", he sold considerable land to people who remained in England as absentee landlords, who soon found that many small houses produced more rent than one or two big ones. One of the houses on Elfreth's Alley acts as a museum, with tours; there is an active civic association, and once a year in June there is a street fair.

Because the land was swampy and the neighborhood congested, Christ Church soon outgrew its backyard burial ground, and burying important people under slabs in the walkways and corridors. Visitors who do not come from that sort of religious background are typically uncomfortable walking over such graves, a quite common arrangement in European cathedrals. But eventually, it was necessary to go several blocks westward to create a "new" burial ground. Most of the famous names from the Revolutionary era, like Benjamin Franklin and four other signers of the Declaration of Independence are found on the tombstones at Fifth and Arch, just across the street from the Free Quaker meeting house, and opposite the Philadelphia Mint. On the remaining corner of Fifth and Arch is the Constitution Center which will open July 4, 2003. It can already be seen that its architecture clashes with the rest of the historic area, but it is fervently hoped that its programs will redeem it.

REFERENCES

| Society Hill and Old City, Image of America: Robert Morris Skaler | Amazon |

American Philosophical Society

|

|

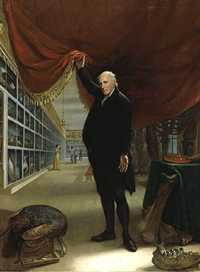

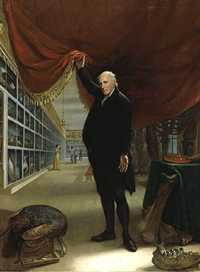

Charles Wilson Peale (1741-1827)

The Artist in His Museum 1822, Oil on canvas (The Joseph Harrison Jr. Collection) Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. |

all of the red brick buildings on Independence Square look as though they were part of Independence Hall, but there is one exception. The building facing Fifth Street is Philosophical Hall, one of the four buildings of the American Philosophical Society. Right now, Philosophical Hall is used as a museum. It could be called the first museum in America, but not the oldest, because it had interruptions and different proprietorships. Charles Wilson Peale started his museum of curiosities there and then moved it to the second floor of Independence Hall, where he painted the famous portrait of himself holding up the curtain. In recent years, Philosophical Hall has again become a museum, holding treasures and curiosities belonging to the Philosophical Society itself. The docent is pleased to alternate between calling it America's new oldest museum, and America's oldest new museum. And, yes, the newell post has an Amity Button.

|

|

American Philosophical Society |

Patents were established by the Constitution when it was a piece of parchment lying on a table fifty feet away from here, and the early patent office required the submission of a working model of every application for patent. After a while, that got to be a lot of working models lying around, and many of the more interesting ones are on display in the museum. Like the model of Fitch's first steamboat or the gadget Jefferson used, to make simultaneous copies of documents he was writing. That's right near the Gilbert Stuart copy of Washington's portrait, and von Neumann's first algorithm to be stored in his stored program machine, or computer, and Neil Armstrong's speech on the moon, concerning one step for mankind and all. It's a splendid museum, full of the real stuff, in a handsome Georgian building with sparkling immaculate marble staircases.

|

|

John Fitch received a US Patent for the Steamboat August 26, 1791 |

In the Eighteenth Century, Natural Philosophy was what we now call science. That's why PhDs get a degree of Doctor of Philosophy when they study chemistry and physics. The idea for forming a scientific society in America apparently originated with John Bartram. As so often happens, the originator couldn't quite get it established and had to call on Ben Franklin that impression of publicity, to get it off the ground. To be fair about it, Franklin was probably the more distinguished scientist of the two. To be even more fair about it, the organization struggled a bit until Thomas Jefferson (that's the one who was President of the United States) gave it a real publicity shove. During the depths of the 1930s depression, one of the members left it several million dollars with the stipulation that the investments should focus on common stock. Since buying stock in 1935 was widely regarded as about the stupidest thing an investor could do, this little episode reinforced a strong impression that membership in the APS is given to people who are very smart, not merely famous. The four buildings, the many fellowships, and the big endowment were largely made possible by this contraries investment decision.

There are eight hundred members, of whom 93 have won Nobel Prizes. Over the years, two hundred members have been awarded Nobel Prizes, but you must remember that the organization existed for 150 years before there was such a prize. Several U.S. Supreme Court justices are members and lots and lots of people who are famous. The docent comments that they look pretty much like everyone else. There's a rumor that Bill Gates turned down the offer of membership, so now we will just see. He's young enough to have several decades' opportunity to reconsider an offer, although the APS might just be old enough to lack interest in any second chances.

Philosophy Means Science in Philadelphia

|

| American Philosophical Society Seal |

In the age of the Enlightenment, science was called natural philosophy; that accounts for the present custom of awarding PhD. degrees in chemistry and botany. The sort of thing which interested Ralph Waldo Emerson was called moral philosophy, and you will have to visit some other place than the A.P.S. if that is what interests you. Roy E. Goodman is presently the Curator of Printed Material (some would say he was chief librarian) at the American Philosophical Society, founded in 1743 by Benjamin Franklin who was clearly the most eminent scientist of his day, having discovered and explained the nature of electricity.

|

| Roy E. Goodman |

Roy Goodman is descended from cowboys and rodeo stars, but in spite of that he gave an entertaining talk recently at the Right Angle Club about this society devoted to useful knowledge, this oldest publishing house and scholarly society in America, once the home of the U.S. Patent Office, and scientific library and museum. They have many rare items in their collection, but the unifying theme is not a rarity, but curiosity. You might say some of the items reflect the whimsy of Franklin, but it would be fairer to say it is an enduring monument to Franklin's universal curiosity about all things.

|

| Nobel Prize Medal |

There are about 900 members of APS, about 800 of them Americans, about 100 of them winners of a Nobel Prize. Let's just make a little list of a very few notables in the past and present membership. Start with the first four Presidents of the United States, add Alexander Hamilton and Lafayette, David Rittenhouse and Francis Hopkinson and you get the idea that Founding Fathers got in early. Robert Fulton, Lewis and Clark, Alexander Humboldt, John Marshall were early members, and more recent ones were Madame Curie,

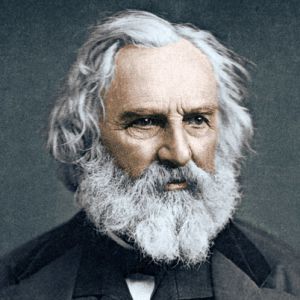

French Philadelphia

|

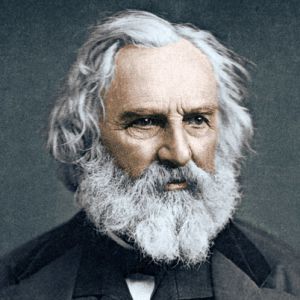

| Henry Wadsworth Longfellow |

Since American relations with France are a little strained at the moment, it may not be completely welcome to hear it said that Philadelphia food is Creole. The reference is not to the several downtown French restaurants of outstanding quality, but to the two episodes when Philadelphia experienced waves of French immigration. The first of these was during the French and Indian War, when the Acadian French ("Cajun") were driven out of Nova Scotia, largely went to Louisiana and then were allowed to return. A lot of them stopped off in Philadelphia both going and coming. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow depicted, in his poem Evangeline, the tearful reunion of Evangeline and Gabriel in the hospital. And since for sixty years the Pennsylvania Hospital was the only hospital in the country, Longfellow had to put them here.

The second wave of French immigration was provoked by the guillotine in Paris, and the black revolution in French Haiti. Most people today are unaware that Talleyrand lived here, and LaRochefoucauld. The Duke of Orleans, future king of France, lived at 4th and Locust Streets, proposed to a (rich) Philadelphia lady, and was rejected by her father ("Sir, if you do not become king of France, you will be no match for her, and if you do become king, she will be no match for you.") Napoleon's brother Joseph lived at 9th and Spruce, and one of his marshals lived at 6th and Spruce. Really. Talleyrand had a deformed foot, and this somehow made him pals with Governor Morris who had a wooden leg. This friendship was part of the reason the Louisiana Purchase was possible, because they shared the favors of the same French lady, and had frequent occasion to meet. Both Franklin and Jefferson were ambassadors to France, it may be remembered, and for a while, Jefferson was quite a fan of the French Revolution, although the treatment of LaFayette by the French Revolutionaries did not exactly encourage that. The French treated Franklin like a God, but then so did Mozart and the King of England, and Franklin harbored many bitter memories of the French and Indian War all the while he was romancing the French into bankruptcy to pay for our revolution. The French refugees from Haiti brought Yellow Fever with them, and Dengue too, thus definitively terminating Philadelphia's hope of remaining the permanent capital of the nation.

It was during this Francophone period that Philadelphia cuisine acquired some characteristics which allow some food historians to call it Creole. Philadelphia Pepper Pot soup, for example, substituted tripe for terrapin. Those who know about these things say that many dishes now thought to be distinctly Philadelphian in fact had a French origin.

The First and Oldest Hospital in America

|

| South East Prospect of Pennsylvania Hospital |

There is a painting of the region around 8th and Spruce Streets in the 1750s, depicting a pasture, with cows, and three or four buildings between 8th and 13th Streets. When the Pennsylvania Hospital moved there in 1755 from its temporary location in a house located a block from Independence Hall, there were complaints that it was now located so far out in the woods that it was difficult and dangerous to go there. Still another description of the area is evoked by the provision which the Penn family placed in the deed of gift of the land, strictly forbidding the use of the land as a tannery. Tanneries have always been notorious for giving off noxious odors, so most people wanted them to be somewhere else, anywhere else. In any event, the main activity of Penn's "green country town" at that time was concentrated closer to the Delaware River, and the nation's first hospital was definitely placed in the outskirts. Two blocks further West the almshouse was already in place, but not much else. We are told that Benjamin Franklin had flown his Famous Kite at 9th and Chestnut, using a barn there to store his materials. It might be recalled that the population of Philadelphia, although the second largest English-speaking city in the world, was only about twenty-five thousand inhabitants at the time of the Revolution, and in 1751 was even smaller.

In any event, the first and oldest hospital in America was built on 8th Street between Spruce and Pine, and the Eighteenth Century buildings on Pine Street still present a breathtaking view at any season, but particularly in May when the azaleas are in bloom, and fragrance from the flowering magnolias fills the evening atmosphere for blocks around. Although some people today mistake the Pennsylvania Hospital for a state hospital, it was founded in the reign of George II, decades before there was such a thing as the State of Pennsylvania. The Cornerstone was laid by Benjamin Franklin, with full Masonic rites. Most doctors regard a hospital as a mere workshop, but the affection with which many Pennsylvania physicians regarded their special hospital is indicated by the number who have requested that their ashes be buried in the garden.

For two hundred years, beginning with the first American resident physician Jacob Ehrenzeller, the interns and residents were paid no salary, so they had to live on the grounds. An Internet was just that, interned within the four walls for at least two years. Because the resident physicians had no money, they stayed in the hospital at night and on weekends, playing cards and swapping stories. The hospital was home for them, as it was for the student nurses, likewise unpaid but more strictly confined and supervised. This penury seemed acceptable because the patients were mostly charity ward patients, otherwise unable to pay for their own care. Ehrenzeller finished his medical apprenticeship and went to practice for many decades in the farm country of Chester County, but gradually upper-class Philadelphia moved from 4th Street westward to and beyond the hospital, and two of the richest men in American history, Morris and Biddle, had houses within a block of the hospital, although Morris never lived in his house, having more pressing matters in debtor's prison. Therefore, later resident physicians at the hospital had the potential of setting up a private practice in the area and becoming society doctors as well as academically prominent ones. Being a charity hospital in a rich neighborhood created the potential for volunteer work by the town aristocrats and large bequests for charity. The British housed their wounded in the hospital during the Revolutionary War and shot deserters against the red brick wall of the small cemetery to the north. A century later, there were a couple of dozen rooms for private patients in the hospital for the convenience of the doctors and the neighbors, but everyone else was a charity patient. And a century after that, the hospital still did not have an accounting department to collect bills and tended to regard people who asked for a bill as a nuisance. Benjamin Franklin is regarded as the Founder of the hospital, and his autobiography famously describes how he fast-talked the legislature into matching the donations of the public, not mentioning to them that he had already collected enough promises to see the project through. This seems in character; Franklin's biographer Edmond Morgan summed up that, "Franklin doesn't tell us everything, but what he does tell us, is straight." The idea for the hospital was that of Dr. Thomas Bond, whose house is now a bed and breakfast on Second Street, but it was characteristic of Franklin to be the secretary of the first board of managers of the hospital. In Quaker tradition, the clerk of a meeting is the person who really runs the show. It thus comes about that the minutes of the founding board were recorded in Franklin's own handwriting, among them the purpose of the institution, which is to care for the Sick Poor, and if there is room, for Those Who can pay. This tradition and this method of operation continued until the advent in 1965 of Medicare when charity care was displaced by concepts which the nation had decided were better. The Pennsylvania Hospital was not only the first hospital but for many decades it was the only hospital in America. Its traditions, sometimes quaint and sometimes glorious, cast a long shadow on American medicine.

REFERENCES

| America's First Hospital: The Pennsylvania Hospital 1751-1841 William Henry Williams Ph.D. ISBN-10: 0910702020 | Amazon |

Nation's First Hospital, 1751-2016

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

As commonly stated in medical history circles, the history of the Pennsylvania Hospital is the history of American medicine. The beautiful old original building, with additions attached, still stands where it did in 1755, a great credit to Samuel Rhoads the builder and designer of it. The colonial building on Pine Street stopped housing 150 patients around 1980, supposedly at the demand of the Fire Marshall, although its perpetual fire insurance policy still owes the hospital several thousand dollars a year as an unspent premium dividend. There may have been one small fire during two centuries of use, but its true fire hazard would be difficult to assert. It was just out of date. The original patient areas consisted of long open wards, with forty or so beds lined up behind fluted columns, in four sections on two floors. The pharmacy was on the first floor, the lunatics in the basement, and the operating rooms on the third floor under a domed skylight. It was entirely serviceable in 1948 when I arrived as an intern doctor. Individual privacy was limited to what a curtain between the beds would provide, but on the other hand, it was possible for one nurse to stand at the end of the award and recognize any distress among forty patients immediately. In this trade-off between delicacy and utility, the utility was certain to be preferred by the Quaker founders. Visitors were essentially excluded, and if a patient recovered enough to be unnaturally curious about neighboring patients, well, he had probably recovered enough to go home.

Located between two large rivers, South Philadelphia up to ten blocks away was essentially a swamp until the Civil War. So, there were seasonal epidemics of malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, and poliomyelitis at the hospital until the early twentieth century. Philadelphia was a port city, so sailors brought in cases of venereal disease, scurvy, even an occasional case of anthrax or leprosy. During the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, tuberculosis, rheumatic fever, and diphtheria were part of clinical practice. But underlying the ebb and flow of environmental effects, there was a steady population of illness which did not change a great deal from 1776 to 1948. These patients were all poor, because the rules in Benjamin Franklin's handwriting restricted service to the "sick poor, and only if there is room, for those who can pay." In 1948 there was a poor box for those who might feel grateful, but no credit manager or official payment office. The matter had been considered, but the cost of collection was considered greater than the likely revenue. When Mr. Daniel Gill was offered the position as the hospital's first credit manager, it was suggested that he be given a tenth of what he collected. To his lifelong regret, Dan Gill regretted that he refused an offer that he had felt he could not afford to accept.

So, the wards were filled with victims of the diseases of poverty, punctuated by occasional epidemics of whatever was prevalent. And a second constant feature of the patients was their medical condition forced them to be housed in bed. For centuries, physicians dreaded the news that a new patient was being admitted with "dead legs".

Keeping Lunaticks Off the Streets

|

| Carpenters Hall |

The birthplace of our nation is both smaller than you would expect and larger. The fire marshall now says no more than 83 people may rent it for a sit-down affair, or 103 for a stand-up gathering. However, the internal partitions have been removed from what was once a center-hall building with a meeting room on either side; it now is a large open room in the form of a Greek cross. At the time of the revolution, Benjamin Franklin's Library Company occupied the second floor, so the First Continental Congress had to find a way to do its work in the side rooms of the first floor, to the side of the center hall. There were 53 delegates, and presumably some staff and visitors.

That sounds rather crowded, but it was nevertheless the largest rentable public space in the city. John Adams arrived early for the convention, conniving with several other early arrivals at the City Tavern. Adams made the following notation in his diary: Monday. At ten the delegates all met at the City Tavern and walked to the Carpenters' Hall, where they took a view of the room, and of the chamber where is an excellent library; there is also a long entry where gentlemen may walk, and a convenient chamber opposite to the library. The general cry was, that this was a good room, and the question was put, whether we were satisfied with this room? and it passed in the affirmative." Alternative places to meet would have been in churches, which presented awkwardness, or in the State House (Independence Hall) which was then under the control of Tories.

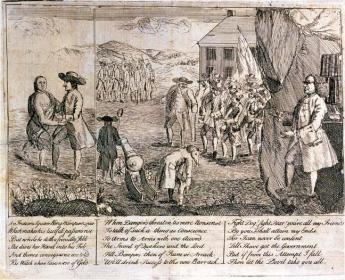

|

| Continental Congress |

France and the rebellious colonies was a complicated one, with intrigue and mistrust at every turn. One interesting episode had to do with Franklin's library on the second floor. The French ministry had sent over a spy, to size up the colonists before the French risked too much on them. So, the spy was led up to the library and allowed to overhear some bellicose conversations going on downstairs -- thoroughly stage-managed for the benefit of the "hidden" French visitor.

The Carpenters Company was a guild of what we would now call builders and architects, and architects continue to use it. The first floor usually displays a few Windsor chairs dating to the Continental Congress, covered with a rich black patina that really lets you know what a patina was. Upstairs, the staff quarters are now, well, a little on the elegant side so you can't visit. The guild was formed in 1724, and fifty years later had just completed its building, in time for its historic role in 1774.

|

| Elfreth's Alley |

With the whole continent available for building, it is still not entirely clear why Colonial Philadelphia crowded itself into half a square mile, with crowded little row houses on crowded little alleys. But that's the way it was, now visible in the location of Carpenters' Hall down a little cobbled alley, in the center of a block. Elfreth's Alley gives you the same feeling, and perhaps Camac, Mole, and Latimer Streets. Carpenters' is a lovely little place, with lots of interesting features, but the main interest lies in what took place there. For that, you have to read a few books.

Dr. Cadwalader's Hat

|

| Dr. Thomas Cadwalader |

The early Quakers disapproved of having their pictures painted, even refused to have their names on their tombstones. Consequently, relatively few portraits of early Quakers can be found, and it might, therefore, seem surprising to see a picture of Dr. Thomas Cadwalader hanging on the wall at the Pennsylvania Hospital. A plaque relates that it was donated by a descendant in 1895. Another descendant recently explained that the branch of the family which continued to be Quaker spells the name, Cadwallader. Dr. Cadwalader of the painting, famous for presiding over Philadelphia's uproar about the Tea Act, was then selected to hear out the tea rioters because of his reputation for fairness and remains famous even today for his unvarying courtesy.

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital |

In one of the editions of Some Account of the Pennsylvania Hospital, I believe the one by Morton, there is a story about him. It seems there was a sailor in a bar on Eighth Street, who announced to the assemblage that he was going to go out the swinging doors of the taproom and shoot the first man he met. So out he went, and the first man he met was Dr. Cadwalader. The kindly old gentleman smiled, took off his hat, and said, "Good Morning, Sir". And so, as the story goes, the sailor proceeded to shoot the second man he met. A more precise rendition of this story comes down in the Cadwalader family that the event in the story really took place in Center Square, where City Hall now stands, but which in colonial times was a favored place for hunting. A man named Brulumann was walking in the park with a gun, which Dr. Cadwalader took as a sign of a hunter. In fact, Brulumann was despondent and had decided to kill himself, but lacking the courage to do so, had decided to kill the next man he met and then be hanged for murder. Dr. Cadwalader's courteous greeting, doffing his hat and all, befuddled Brulumann who went into Center House Tavern and killed someone else; he was indeed hanged for the deed.

I was standing at the foot of the staircase of the Pennsylvania Hospital, chatting to a young woman who from her tailored suit was obviously an administrator. I pointed out the Amity Button, and told her its story, along with the story of Jack Gallagher, whom I knew well, bouncing an empty beer keg all the way down to the Great Court from the top floor in the 1930s, which was then being used as housing for the resident physicians. Since the young woman administrator was obviously beginning to regard me like the Ancient Mariner, I thought one last story about courtesy was in order. So I told her about Dr. Cadwalader and the shooting.

"Well," she said, "The moral of that story obviously is that you should always wear a hat." There then is no point to further conversation, I left.

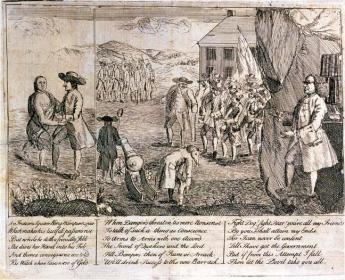

Pembertons

|

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

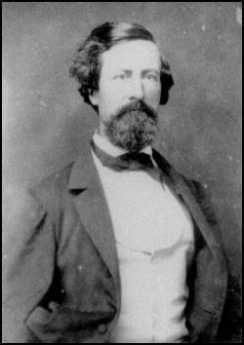

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

The Jews in Colonial Philadelphia

|

| Haym Salomon |

The word Sephardi is derived from the Hebrew word for Spain, where Jews were a prominent part of the Arab community for several hundred years. The Christian monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, regarding the Sephardim as pro-Arab, drove them out of Spain and Portugal in 1492. They scattered widely, and only a small portion eventually got to the Western hemisphere. It is also helpful to know that Askenazic is the Hebrew word for German since this other main branch of the religion did not emigrate to America until later in the Nineteenth century in response to the suppression following the 1848 Revolutions. There are some important differences in liturgy, and occasional episodes of bad feeling between the two Jewish groups, some of it kept alive by issues arising in Israel. Historically, the Sephardim have had a greater tendency to assimilate in local cultures, both generally and particularly in Philadelphia. However, the most prominent Jew in the American Revolutionary War was Haym Salomon, who was born in Poland.

On leaving Spain, many Sephardim had gone to Amsterdam, and from there to the Dutch colonies hat accounts for their presence in the Delaware Bay as part of the Dutch settlements which preceded William Penn's arrival. The British conquest of the Dutch accounts for their subsequent local disappearance. However, it paradoxically also accounts for an influx from Curacao and other Caribbean Dutch colonies conquered by the British, usually favoring New York as a place to settle. Presumably, Sephardic feelings about the English were cautious at best. When the British occupied New York in the early days of the American Revolution, many Sephardim fled to Philadelphia, but largely returned to New York after the end of the Revolution. There was thus a double process of filtering out those who were unsympathetic with the British, and those who were attracted by seeing what Philadelphia represented.

Records were poorly kept in those days, and in civil wars, there are often reasons to be vague about your sympathies and activities. We know that Haym Salomon came to Philadelphia in 1774, grew very rich in association with Robert Morris, but died in poverty after a few years, now lying in an unmarked grave. It is a little unclear how he became rich, although all merchants involved in shipping did a little privateering, often described as piracy by the victims. It is also unclear how he became suddenly poor, although speculators in currency and land often make serious misjudgments. Robert Morris is himself a prime example.

The matter becomes of greater interest when Haym Salomon is sometimes referred to as one of the main financiers of the Revolution. Partly because of the ease of counterfeiting with the primitive printing technology of the time, the British had forbidden the use of paper money in the colonies as part of the Townshend Acts. While understandable, it caused great pain to unbalanced trade partners, and metal coins quickly migrated back to England, almost paralyzing colonial economies for lack of cash to transact local business. It probably caused a different sort of a pain to Benjamin Franklin, who derived much of his income from printing the currency of New Jersey. In particular, it kept cargoes trapped in port for lack of payment, which the annoyed British merchants mistook as an implementation of John Dickinson's proposal for deliberate "non-importation". In any event, Jewish merchants and bankers were well situated to find ways around currency blockages, sometimes using precious gems as substitutes for specie, and utilizing informal family networks scattered around the world. In civil wars, guns have to be bought and paid for, legalities get swept aside. There is said to be evidence that our ambassador to France, Benjamin Franklin, utilized Salomon to translate the French loans he had negotiated into the munitions which colonials needed. There is incidentally reason to believe that the Rothschild family established its great wealth by similar commodity dealings at the time of the Battle of Waterloo.

Just what it was that went so drastically wrong for Haym Salomon at the conclusion of our war for independence has not yet been made clear, perhaps never will be. He may have been caught in the uproar over the worthless Continental currency, his ships may have been captured, or he may have been trapped by the land speculation which ruined Robert Morris. But those were rough, tough times. We have the word of those who should know, that Salomon's service was essential to our achievement of Independence.

America in 1767

|

| Johann de Kalb |

Baron Johann de Kalb was to die a hero of the American Revolution in 1780, but in 1767 he was a spy for France, scouting out potential French opportunities in America. He made the following report to the French minister of foreign affairs, duc de Choiseul:

"Everywhere there are children swarming like broods of ducks, large fertile farms, flourishing industries, and harborsbarely able to hold the and fishing and Merchant Fleets

"Whatever may be done in London," judged de Kalb, "this country is growing too powerful to be much longer governed at such a distance."

- as cited by Walter A. MacDougall, Freedom Just Around the Corner

REFERENCES

| Freedom Just Around the Corner: A New American History: 1585-1828: Walter A. McDougall ISBN-13: 978-0060197896 | Amazon |

Benjamin Franklin: Chronology

|

| Ben Franklin on the cover of Time magazine |

January 17, 1706 Born in Boston, the thirteenth child of a candle maker; only went through 2nd Grade, Apprenticed to his brother as a printer, ran away to Philadelphia age 17 .

1723 Arrived in Philadelphia penniless, readily found work as a printer.

1725-26 First trip to England. Researched printing equipment, but probably lived a riotous life.

1726-1748 Returned to Philadelphia to found his own print shop and bookstore. Wrote and printed Poor Richard's Almanack organized local tradesmen into the Junto, formed partnerships with sixty printers throughout the colonies, obtained the print business of local governments, became postmaster. Able to retire at the age of 42 by selling his business for 18 annual payments, which offered him comfort and ease for considerably longer than his life expectancy.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1751 Helped found Pennsylvania Hospital. Entered the legislature.

1751-1757 Active in legislature, rising to leadership during the French and Indian War, Pontiac's Rebellion and the uprising of the Paxtang Boys.

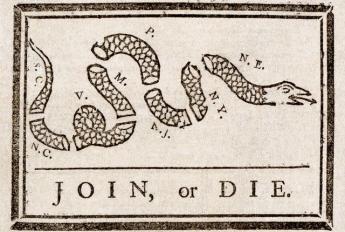

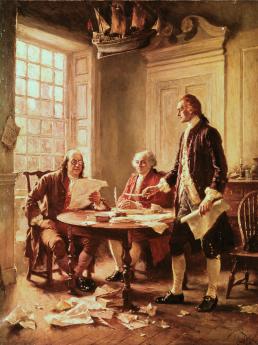

1754Took a noteworthy carriage trip to the Albany Conference, accompanied by fellow delegates Proprietor Penn and Isaac Norris at which he proposed unification of the thirteen colonies to fight against the French. Composed the first political cartoon "Join or Die" for that purpose. Notes for the trip on the blank pages of "Poor Richard's Almanac", now at Rosenbach Museum. The other delegates rejected the plan.

1757-1762 Second time in England. Acted as representative of both Pennsylvania and Massachusetts. After his electoral defeat, he returned to England for a total of eighteen years, suggesting hidden British sympathies may have been present. .

1762-1764 Returned to Pennsylvania Legislature, where his unpopular agitation for replacing the Penn Proprietors with direct Royal government led to his electoral defeat and the end of his elective career. The defeated but determined Quaker party sent him to England to lobby against the Penn family and for the rule of Pennsylvania by the King.

1764-1775 Third British visit. Although unsuccessful in his lobbying, his fame as a scientist made him welcome among the famous members of the Enlightenment, like Hume, Adam Smith, Mozart. Meanwhile, the colonies became considerably more rebellious than he was. His blunder with the publication of some letters gave the British Ministry an opportunity to humiliate and disgrace him in public, probably as a warning to the mutinous New England leaders. It irreconcilably alienated Franklin, who sulked, then packed up and joined the Continental Congress the day he arrived back home.

March, 1775-October, 1776 Brief but fateful return to America. Decisions were made in London to put down the colonists by as much force as necessary. Meanwhile, Franklin persuaded the Continental Congress they must declare independence from England if they expected help from the French.

July 4, 1776, Independence is declared within days after the arrival of a massive British fleet in New York harbor. Franklin dispatched to France to secure the assistance he was confident he could get.

1777-1785 France. Franklin served admirably as American ambassador, his wit and charm persuading the French to overextend themselves with ships, supplies, and money, and very likely contributing to the French Revolution by popularizing the American one.

1785-1790 Returning as a national hero for his final five years of life, Franklin loaned his personal influence to the constitutional convention, became President of Pennsylvania, worked for the abolition of slavery.

April 17, 1790 Died, probably of complications associated with kidney stones.

Sacred Places at Risk

|

| Old St. Joe's |

When William Penn invited all religions to enjoy the freedom of Pennsylvania, he created a home for the first churches in America of many existing religions, and furthermore the founding mother churches for many new religions. Regardless of the local congregation, there is obviously a strong wish to preserve the oldest churches of the Presbyterian, Methodist, United Brethren, African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist, Mennonite, and many other denominations. While the founding church of Roman Catholicism was obviously not in Philadelphia, St. Josephs at 3rd and Willing was for many decades the only place in the American colonies where the Catholic Mass could be openly performed. The towering genius of William Penn lay in the combination of an almost saintly wish to spread religious toleration, combined with what must have been a sure recognition that the motive of Charles II in giving him the land, was to get rid of all those dissenters from England.

Philadelphia now has a thousand church structures within the city limits, and more than a thousand in the suburbs. However, many church buildings find themselves stranded by the migration of local ethnic groups to other locations, and a decision must be made whether to demolish a relic or sell it to a new population who have moved into the old neighborhood with a new religion. There is still greater discomfort with selling an old church to a commercial enterprise, but even that happens. The resulting bewilderment and dissension among the surviving parishioners is easy to imagine as they face these choices, or fail to face them, and it is readily imagined that the establishment in 1989 of Partners for Sacred Places filled a very important need.

|

| First Presbyterian Church |

The Executive Director, Robert Jaeger, recently described to the Right Angle Club how the Partners operate. First of all, the Constitutional separation of church and state makes it difficult to seek funding or even advice from the Federal government. Pennsylvania has been less hesitant than most states in this regard, but even here the issue of fund-raising is a central issue. One only has to look at the Aztec and Mayan religious sites in Mexico to grasp that there are circumstances when the parishioners of a religion may have completely died out, but their monuments justify state assistance. Private, nondenominational philanthropy seems the easiest route for a society to take, in avoiding the obvious political and legal entanglements of seeming to assist one denomination more than others.

And then there are architectural issues;, can the building be saved at a reasonable cost, is it truly a unique or outstanding piece of art, can a reconstruction go ahead in an incremental way, are the necessary stone or other materials any longer obtainable, do the workman skills exist? In addition to these issues which are commonly presented to a congregation, there are issues they probably have never considered. As congregants move from center-city to the suburbs, they become commuters to church, largely out of touch with the local community and its activities. A survey conducted by the Partners suggests that 81% of the activity which takes place in church buildings on weekdays is conducted by and for non-members of the church; if the two groups lose touch with each other, opportunities are missed, and eventually there may be unnecessary friction. On the other hand, those non-religious activities probably escape the legal prohibitions against government assistance, and may suit themselves as vehicles for indirect government support. The approach has so much promise that Partners for Sacred Places has devised a computer program on their website which provides a way for congregations to assess their assets, and their problems. In fact, the organization conducts extensive training programs for church preservation, and has been forced by the size of the demand to exclude churches that are clearly failing beyond reasonable hope of recovery by their church membership.

The Partnership was originally founded by consolidation of the New York and Philadelphia organizations, to make a stronger national effort. But now things are going the other way. New chapters are springing up in Texas and California. Partners for Sacred Places is obviously proving to be a good idea, effectively managed.

WWW.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1269.htm

Powel House, Huzzah!

|

| Elizabeth Powel |

If George Washington were still alive he would no doubt be a Republican, but the term Republican Court actually has nothing to do with R's and D's. It was a scheme deliberately cooked up by Washington and Madison to enlist support by the new government's important ladies for a modified version of a European royal court, to make thirteen colonies into a cohesive nation. A most remarkable thing about it was its frank imitation of the royal courts, something only the Father of His Country could pull off in former colonies which had just fought an eight-year war to be rid of the monarchy. It is one more great testimony to the faith of Americans in George Washington; but it also testifies to the power of enthusiastic women, once they agree on a project. Chief among the leaders in this court was Elizabeth Powel, along with her niece living around the corner on Spruce Street, Anne Willing Bingham. Recently, the Peale Society of the Academy of Fine Arts held a candlelight dinner in Mrs. Powel's magnificent second-floor dining room, while scholars of the history of the Republican Court told assembled notables of Philadelphia what had once been what, during the first ten years of the Republic.

|

| Dining Room |

Members of the early Congress were largely the same men as the founding fathers of the Constitutional Convention, hand-picked by Washington and Madison to persuade the legislatures of their colonial states to give up state sovereignty, for a unified nation. There was the difference that now they brought their wives to live in Philadelphia during sessions of Congress. Those women wanted to know each other and wanted to have something exciting to do together in the largest city in the nation. Their husbands knew well how politically useful it was to be socially acquainted in this way, so everybody liked the idea of suddenly becoming nationally connected. The initial idea proved unworkable. Martha Washington was supposed to become Lady Washington, reigning over weekly receptions.

|

| In Our Cups |

But Martha, unfortunately, wasn't up to the task, and Anne Bingham whose rich husband had taken her on lengthy tours of European royal courts, moved right in and took charge of this project. Besides her cousin Elizabeth Powel, notable members of this social whirl were the two daughters of Chief Justice Benjamin Chew, Alexander Hamilton's wife, and various members of the Shippen and Willing families. Members of the family of Lord Sterling of New Jersey, Charles Carroll of Carrolton, Maryland, Cadwaladers of various sorts, and a number of other names famous from then until even today joined their affiliations with ladies from other states through parties and even some weddings. John Adams was particularly awestruck by the poise and beauty of Anne Bingham, although Abigail Adams may not have been quite so infatuated. It was a dizzy whirl, with dinner parties the central activity just as they are in Philadelphia even today. Country bumpkins had to learn how to dress, to talk and to eat with the right spoon and keep their elbows off the table; those who could tactfully show them what was what were friends for life. Centuries later, Emily Post made a fortune writing books about these rules.

|

| Republican Court |

In those days, they even had their war cry, which was to raise a glass and shout back "Huzzah" in response to the proposer of a toast, who had raised his glass starting the warcry. It wasn't "Skol" or "Cheers" or "Here, here" if you knew what was what; it was "Huzzah". Most fashionable dinners had at least twenty courses, but the ladies didn't eat them. It was a whispered instruction among the ladies that they should eat before the dinner, so they could gracefully decline to gobble up goodies, and spend their time in gay conversation or waiting to be asked to dance. Drinking and eating, especially drinking, was for the men at the party, although naturally the many courses of the banquet were put in front of the ladies to be airily ignored. When George Washington was present as he often was, or even La Rochfoucault himself, it was important to remember every spoken word.

And, you know, it worked. When these important people went back home, they took the customs of the Republican Court with them. The American diplomatic corps found the equivalent of minor-league training for their efforts on behalf of the country abroad. Politics was easier if you personally knew your adversaries as well as your allies. The persistence of the same family names in the Social Register, the lists of The Four Hundred and other compilations of high society show that Anne Bingham and Elizabeth Powel did indeed know what they were doing, and for that matter, so did George Washington. If anyone else had been at the top of this heap, Thomas Jefferson stood ready to attack with all his might.

|

| Amity Button |

But he and even Patrick Henry didn't dare attack Washington. The aristocrats of Old Europe probably did sneer at this amateur effort, and in some circles still, do. But the inability of absolutely any other group of nations, whether European, Asian or South American, to unite peacefully is a thumb in the eye of anyone who mocks George Washington's little Philadelphia creation. And to think it all began right here, right here in the Powel House, right here in the dining room on the second floor. For that, folks, one thunderous "Huzzah!"

REFERENCES

| A Portrait of Elizabeth Willing Powell: 1743-1830 David W. Maxey ISBN-13: 978-0871699640 | Amazon |

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

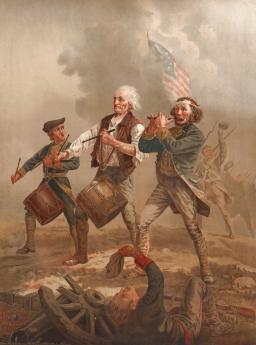

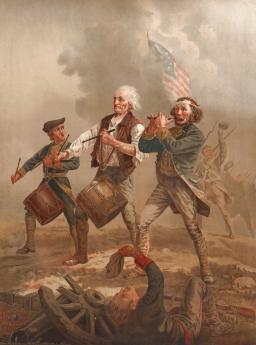

| Spirit of 76' |

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

Philadelphia in '76

|

| Spirit of '76 |

Although the origins of the American Revolution are subtle and complex, even historically controversial, we have more or less united in the idea that we "declared" our independence from Britain on July 4, 1776. We then spent eight years convincing the British we were serious and have been independent ever since. Reflect, however, on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add to that the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had quite a nerve implying the whole thing was his idea. What's more, New England subsequently had to live with a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging the others along with it. It was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine.

New England was in the position of having started hostilities, and about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What the New Englanders wanted was WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing the dependency on the British homeland, without any sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. Perhaps it was unfortunate that New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming, and without support, New England was likely to be subdued like Carthage.

And then, the last hope for flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, stepped off the boat. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He finally was saying what others had been thinking. It was now, or never.

July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

According to the records of the Pennsylvania Hospital, the following 48 persons were patients in the hospital on July 4, 1776:

| Richard Brinkinshire (Admitted 11/15/1775) | John Ridgeway (Admitted 12/26/1775) |

| James Chartier (Admitted 1/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/6/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) | patient (Admitted 1/20/1776) |

| Mary Yell (Admitted 2/7/1776l) | John Beckworth (Admitted 2/7/1776) |

| Bart. McCarty (Admitted 2/10/1776) | John King (Admitted 2/10/1776) |

| Robert Alden (Admitted 2/17/1776) | William Patterson (Admitted 3/6/1776) |

| Elizabeth Hanna (Admitted 3/9/1776) | John McMahon (Admitted 3/13/1776) |

| Mary Burgess (Admitted 3/23/1776) | Mary Anderson (Admitted 4/10/1776) |

| John Hatfield (Admitted 4/15/1776) | Eliza Haighn (Admitted 4/17/1776) |

| Charles Whitford (Admitted 4/24/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| Susanna Carrington (Admitted 5/8/1776) | patient (Admitted 5/8/1776) |

| William Johnson (Admitted 5/13/1776) | Lazarus Chesterfield (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| Mary Spieckel (Admitted 5/22/1776l) | William Edwards (Admitted 5/22/1776) |

| patient (Admitted 5/23/1776, Lunatic) | Jane White (Admitted 5/25/1776) |

| Charles McGillop (Admitted 5/29/1776) | ---Fitzgerald (Admitted 6/1/1776) |

| Michael Rowe (Admitted 6/6/1776) | patient (Admitted 6/6/1776) |

| John Hughes (Admitted 6/12/1776) | Joseph Smith (Admitted 6/15/1776) |

| Esther Munro Lunda (Admitted 6/15/1776) | Mathew Coope (Admitted 6/19/1776) |

| Anne Patterson (Admitted 6/19/1776) | Thomas Savoury (Admitted 6/20/1776) |

| Rebecca Winter (Admitted 6/26/1776) | Elizabeth Manning (Admitted 6/26/1776) |

| Negro (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Elex. Scanvay (Admitted 6/24/1776) |

| Fanny Stewart (Admitted 6/24/1776) | Peter Barber (Admitted 6/29/1776) |

| Catherine Campbell (Admitted 6/29/1776) | Ann McGlauklin (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

| Elizabeth Lindsay (Admitted 7/3/1776) | Ann Jones (Admitted 7/3/1776) |

The records indicate the following diseases were the reason for admission of those patients. Although in Colonial times there was no medical delicacy to avoid offending readers, present privacy standards require that we strip the diagnoses from the name of the patient and list them independently. There is some overlap, sometimes making it difficult to judge which disorder caused the admission.

- Sore, poisoned or ulcerated legs: 16 cases

- Lunacy, mind or head disorders: 10 cases

- Syphilis: 7 cases

- Fever and Rheumatic fever: 7 cases

- Dropsy: 5 cases

- Gunshot: 4 cases

- Diabetes: 1

- Blindness with clear pupil: 1

- Spitting blood: 1 case

- Dislocated arm: 1 case

- Inflammation of face: 1 case

- Scurvy: 1 case

- broken arm: 1 case

The following physicians were elected at the Managers Meeting dated 5/13/1776:

- Dr. Thomas Bond

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Dr. John Redman

- Dr. William Shippen

- Dr. Adam Kuhn

- Dr. John Morgan

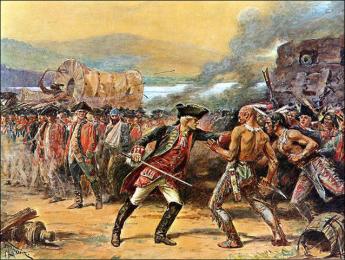

Politics of the French and Indian War

|

| Isaac Sharpless |

In the European view, the French and Indian War was a mere skirmish in the many-year conflict between France and England. But the Atlantic is a wide ocean. The local Pennsylvania politics of that war concern the land-hungry settlers striving for Indian lands, the Quaker Assembly doing its best to maintain William Penn's formula for peace ("No settlements without first buying the land from the Indians."), and William Penn's far-from-idealistic Anglican sons, focused on profit from a land rush. Western Pennsylvania belonged to the Delaware tribe, but the Delawares were subject to the Iroquois nation. The year is 1754. The following pro-Quaker description is given by Isaac Sharpless, president of the Quaker Haverford College between 1887 and 1917 (Political Leaders of Colonial Pennsylvania,

|

| Isaac Norris |

Isaac Norris was appointed to another Albany treaty with the Indians in 1754. The commission consisted of John Penn and Richard Peters representing the Proprietors, and Benjamin Franklin and himself, the Assembly. Indian relations were becoming difficult. The Five Nations still claimed the right to the ownership of Pennsylvania and insisted that no sale of land by the Delawares was permissible. In an evil hour, the government of Pennsylvania recognized this claim and this Albany meeting was for the purpose of effecting a purchase. By methods that were more or less unfair, taking advantage of the Indian ignorance of geography, they bought for 400 pounds all of southwestern Pennsylvania. When the Delawares found their land had been sold without their consent, they threw off the Iroquois yoke, joined the French, defeated Braddock's army a year later and for the first time in the history of the Colony the horrors of Indian warfare were known on the frontiers.

Although Sharpless goes directly to the unvarnished truth of the situation, he reveals the depth of his bitterness by openly discarding Franklin's cover story about being in Albany to propose political unity among the British colonies.