3 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

Four Constitutions

Multi-national unions of republics are uncommon, usually brief and seldom voluntary. America has had three of them, but we only got it right the second time. Uncertain why we succeeded when many others failed, we remain skeptical of changing the rules. The Europeans, on the other hand, are uncertain whether they want to follow the Confederate States of America toward extinction, or the United States of America toward world domination. When deeply considered, it is a hard choice.

..Tax and Fiscal Issues in the Constitution, Morris (1)

For some founding fathers, monetary issues were all that mattered.

THE Constitution was written after several severe inflations of paper money, with all its traditional components. Paper money and shortages of coinage contributed significantly to disruptions before the Revolution, but the public mostly did not grasp the connection. During the Revolution itself however, the home front learned the universal economic lessons in a bitter, practical way. In particular, it became a common cultural understanding that paying for essentials by issuing worthless paper money, invariably leads to rising prices. When prices rise, governments typically respond by suppressing them with price controls. But artificially suppressed prices provoke farmers and producers to hold their products off the market until shortages appear. Famines in cities, surrounded by surpluses in hide-aways, infuriate the mobs. Protest riots get out of hand, governments fall. Anarchy prevails.

|

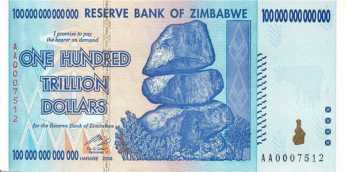

| Zimbabwe $100 Trillion Dollar Bill |

This four-step process has marched relentlessly from paper money to anarchy scores of times, in almost every nation, for thousands of years. A four-step process is just complicated enough to bewilder the mass of people, particularly when their attention is diverted to the symptoms and away from root causes. One unwelcome message is ignored or denied: paying with debt never pays for anything. It merely delays the time of payment.

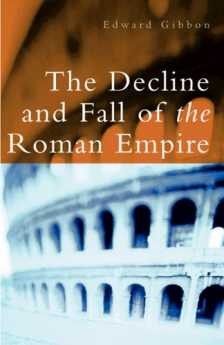

It made a significant difference that two books were published in 1776: Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations and Edward Gibbons' Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Between them, these books taught that economic freedom underlies other freedoms perhaps even underlies all of them, and fair dealing underlies successful economics. In short, honesty is the best policy. Someone took that motto from Aesop's Fable and gave it to George Washington, who gave it to the nation.

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 took place because a few well-placed leaders recognized the nature of the problem and devised some workable solutions. The rest of the nation eventually ratified the proposal because they had recently watched the four-step inflation problem unfold, had to acknowledge its seriousness, and lacking any alternative, agreed to try the remedy. A nation's populace will seldom accept severely painful solutions without such near-death experiences. In the eight or ten monetary crises America has endured since 1787, conditions have always proceeded to a dangerous state before the populace finally acknowledges the need to accept a painful cure. To a certain degree, this refusal to take action that has been merely proposed as a "conjecture" is an American national trait, which in the Law Profession is described as insisting that a plaintiff have "standing" in order to make a claim. Inevitably, this habit does occasionally result in waiting too long, or else the cure stops working. It did work in 1787.

There are two ways it may not work. The nation may learn the wrong lesson, and conclude that all debt is a bad thing -- "neither a borrower nor a lender be". Somewhere in his business life, Robert Morris had learned that even a rich man can starve if he lacks credit to borrow when he lacks ready cash, or his cash is worthless paper money. Morris looked out at a rich nation stretching to the Pacific, with an aggressive prosperous population. This nation is rich. What it lacks is a vaporous concept called credit, the ability of someone with collateral, to borrow. Just start passing worthless paper money, and you will soon lose your credit. A poor man has no credit, and deserves to have no credit. During the worst of the financial panic surrounding the Revolutionary War, the nation was as rich as it ever was, but it had lost its ability to borrow, it had lost its credit. During the Revolution, Morris had stepped forward and offered to pay the nation's debts if the government couldn't do it. During the War of 1812, Stephen Girard did the same thing, as did J.P. Morgan during the Spanish-American War. It didn't cost any of these rich men to do it, because the nation was rich, but temporarily needed credit. If the nation is poor, that won't work.

Robert Morris recognized that it would be hard to get rich men to extend their credit, unless there is some way to get enough cash flow to service the debt. It's sometimes hard for newcomers to understand why a history of paying your debts on time seems so vital; but learning from experience teaches lenders that it's the only way to know if a debtor can be trusted. The key to the whole system on a governmental level was to give the government clear authority to tax the citizens enough to service the war debts, but not enough to tempt some future profligate Congress to borrow more than can possibly be repaid. The modern shorthand for that situation is to restrain the national debt from exceeding the gross domestic product; it is the answer to the simple banker's question, "How do you expect to pay this loan back?" Therefore, the Constitutional Convention had pretty much served its purpose from Morris' point of view, when it agreed to a single sentence:

"The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence . . . "

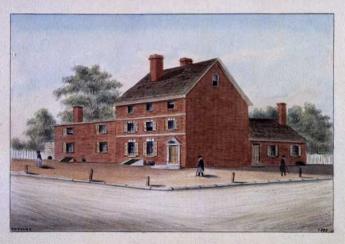

Fort Wilson: Philadelphia 1779

|

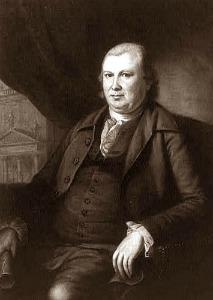

| James Wilson |

OCTOBER 4, 1779. The British had conquered then abandoned Philadelphia; an order was still only partially restored. Joseph Reed was President of the Continental Congress, inflation ("Not worth a Continental") was rampant, and food shortages were at near-famine levels because of self-defeating price controls. In a world turned upside down, Charles Willson Peale the painter was a leader of a radical group of admirers of Rousseau the French anarchist, called the Constitutionalist Party, leaning in the bloody direction actually followed by the French Revolution in 1789. Peale was quick to admit he had no clue what to do with his leadership position and soon resigned it in favor of painting portraits of the wealthy. Others had deserted the occupied city, and many had not yet returned. The Quakers of the city hunkered down, more or less adhering to earlier instruction from the London Yearly Meeting to stay away from any politics involving war taxes. About two hundred militia roamed the city streets making trouble for anyone they could plausibly blame for the breakdown of civil order. Philadelphia was as close to anarchy as it would ever become; the focus of anger was against the pacifist Quakers, the rich merchants, and James Wilson the lawyer.

|

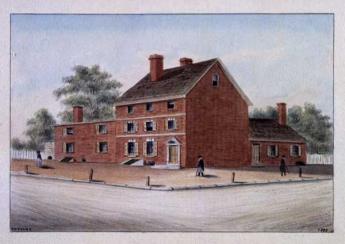

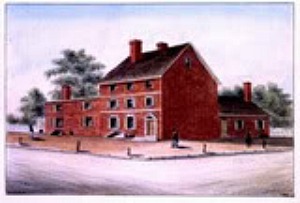

| Fort Wilson |

Wilson had enraged the radicals by defending Tories in court, much as John Adams got in trouble for defending British troops involved in the Boston Massacre; Ben Franklin advised Wilson to leave town. It is still possible to walk the full extent of the battle of Fort Wilson in a few minutes, and the tourist bureau has marked it out. Begin with the Quaker Meeting at Fourth and Arch. A few wandering militiamen caught Jonathan Drinker, Thomas Story, Buckridge Sims, and Matthew Johns emerging from the Quaker church, and rounded them up as prisoners. The Quakers were marched down the street for uncertain purposes when the militia encountered a group of prominent merchants emerging from the City Tavern. Unlike the meek Quakers, Robert Morris and John Cadwalader the leader of the City Troop ordered the militia to release the prisoners, behave themselves, and disperse; Timothy Matlack shouted orders. It was exactly the wrong stance to take, and about thirty prominent citizens were soon driven to retreat to the large brick house of James Wilson, at the corner of Third and Walnut, known forever afterward as Fort Wilson. Doors were barred, windows manned, and Fort Wilson was soon surrounded by an armed, shouting, mob. Lieutenant Robert Campbell leaned out a third story window and was soon dropped dead by a lucky bullet. It remains in dispute whether or not he fired first. Crowbars were sought, the back door forced open, but the angry attackers scattered after fusillades from inside.

|

| Joseph Reed |

Down the street came President Reed on horseback, ordering the militia to disperse, with Timothy Matlack at his side; both men were well-known radicals, here switching sides to maintain law and order. The City Troop arrived, an order was given the cavalry to Assault Every Armed Man. The radicals were finally dispersed by this makeshift cavalry charge, cutting and slashing its way through the dazed militia. When it was over, five defenders were dead and about twenty wounded. Among the militia, the casualties were heavier but inaccurately reported. Robert Morris took James Wilson in hand and retreated to his mansion at Lemon Hill; Wilson was the founder of America's first law school. Among other defenders huddled in Fort Wilson were some of the future framers of the Constitution from Pennsylvania: General Thomas Mifflin, Wilson, Morris, George Clymer. Equally important was the deep impression left on radical leaders like Reed and Matlack, and Henry Laurens, who could see how close the whole war effort was to dissolution, for lack of firm control. Inflation continued but the center-productive price control system was abandoned and never revived; the Patriots had a bad scare, and the heedless radicals forced to confront the potentially disastrous consequences of their own amateur performance when entrusted with the power and responsibility they had just been demanding. It was one of those rare moments in a nation's history when the way suddenly opens to previously unthinkable actions.

|

| Timothy Matlack |

The Battle of Fort Wilson was the only Revolutionary War battle fought within Philadelphia city limits; a revolution within a revolution, every participant was a Rebel patriot. Reed and Matlack were the two most visibly appalled by the whole uproar, forced by circumstances to attack the forces of their own political persuasion. But it seems very certain that Robert Morris and the other prosperous idealists were also left with an indelible conviction that even a confederation must maintain central command and discipline with an iron will, or all might be lost. A knowledgable French observer estimated that Robert Morris then owned assets worth eight million dollars, an almost unimaginable sum for the time. But he would lose every penny if effective political control could not be restored. A few days later in the October election, he and all the other Republican (conservative) officials lost their seats. It did not matter; Morris then knew what to do, and his opposition didn't.

Economics of the Oct. 4th, 1779 Attack on Fort Wilson

|

| Fort Wilson |

From time to time new essays appear, arguing the dynamics of the Fort Wilson episode of mortal gunfire between factions of the Revolutionary cause. The event is an important one, primarily because it involved several men who later were Delegates to the Constitutional Convention. It thus casts light on the economic attitudes of leaders in the effort to revise the constitutional rules for property which emerged eight years later, in 1787. It seems entirely fair to suppose that men whose lives were threatened by armed conflict with their comrades had retained a vivid memory of it.

In the first place, what became an armed conflict over inflation and food shortages was a dispute which lasted more than six months, and had the outlines of an organized conflict between two parties, the Republicans and the Constitutionalists, which also had the character of class warfare between the merchant class and the yeomanry of the city. And although the economic issues involved in this conflict have been recurrent over a period of two hundred years, they are not exactly settled in the minds of the two parties. It is not too much to suppose that a representative group of present-day Democrats and Republicans would divide into majorities who favor or oppose price controls, and who are made up of two social groups who style themselves Upper Class and Middle Class.

The most recent analysis of Fort Wilson was written by John K. Alexander in October 1974 in the William and Mary Quarterly and it is quite a detailed examination of the subject. Although the Pennsylvania militia did much of the fighting and introduced the extraneous issue of patriotic military service, they were escalating the anger of what probably started as reasoned economic debate. Food scarcities appeared on every side and were severe, prices were skyrocketing. It seemed entirely reasonable to this faction that merchants were raising their prices deliberately, taking advantage of food shortages, and that it was the responsibility of government to side with consumers to hold prices down with price controls. The merchant class calling themselves Republicans were led by Benjamin Rush, who grew concerned that the more numerous common people would use their majority power to injure the interests of the merchants. In the eyes of the consumer class, it is merchants who mainly set prices, and thus merchants must be restrained by government. Their viewpoint was augmented by the writings of John Locke, who had urged that the common people have a right to take arms when government fails them.

Almost any modern economist would reflexly assume that the problem underlying this agitation was inflation, generally styled "paper money" by the politicians of that time. If too much money is in circulation, prices will go up. If price controls are imposed in that situation, goods will disappear from merchants' shelves, black markets will appear, and with people starving, riots will break out. Academic economists should not jump to the conclusion that this is obvious, however. Prices are normally set by the sellers, held in check by consumers refusing to buy at unfairly high prices. When inflation takes place, it does so in hidden places away from public view. The treasury issues paper money, or reduces the gold content of coins, or the Federal Reserve issues bonds, more or less unseen by the public. Prices rise but for a while, the public assumes they are rising in the traditional way, by merchants raising their prices. The public is often slow to believe that a new dynamic is affecting prices because they want to believe they still have the power to reduce prices by verbal abuse of the merchants; it doesn't work. By the time the public realizes things are serious, things are mostly getting out of hand. Starvation is now a real thing, and the discovery of hoarding by merchants who will not sell at the old prices only heightens their conviction that sharp dealing is responsible for their pain. When they finally become convinced that their government is the enemy in this matter, it becomes time to distrust government officers, and maybe to burn a few buildings. The better-educated class is generally the more affluent class, with more reserves to protect them longer from the pain which the lower classes are experiencing.

On the other hand, if you are Robert Morris trapped in Wilson's red brick house, with bullets whistling past your ears, you also forget about economic theory and consider how you can save your own life, liberty, and pursuit of happiness. As the immediate danger subsides, you ask how situations like this can be avoided. And while it cannot be claimed that America has cured itself of inflation, much stronger controls are now in place, and many more of the public understand where the fault lies. If paper money inflation ever gets seriously out of hand as it did in Germany, Austria, China, and Zimbabwe -- the public will tolerate almost anything else to avoid it, for as long as a century afterward. But not indefinitely, as long cycles of history unfortunately demonstrate.

REFERENCES

| The William and Mary Quarterly Oct,1974 Vol. XXXI No. 4 Page 589 John K. Alexander | Amazon |

Paper Money

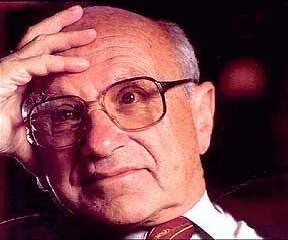

The Constitution does not prohibit paper money, as a glance inside almost any wallet will demonstrate. Although counterfeiting was a common problem in early America because of the primitive state of 18th-century printing, and the problems of inflation were commonly confused with the use of paper money, the Colonial merchant class mostly knew better. Paper money was a term of art for inflation, mostly evidenced by shortages and price controls, escalating prices and hoarding of goods. The Nobel economist Milton Friedman was succinct: "Always and everywhere, inflation is a monetary problem." Friedman was cute and brief, but he might have been slightly more clear. Governments control the money supply, mostly by borrowing to delay paying for their own spending. Inflation is not caused by paper money, or banks, or price controls. It is caused by governments spending borrowed money, thus increasing the money supply faster than the goods money can buy.

|

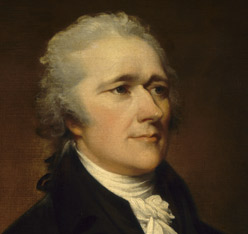

| Alexander Hamilton |

America may not have had any hard money, and many people were having a difficult financial time of it, but in Morris's view, America was rich. America had rivers and forests, farms and factories, immigrants pouring in, and a prosperous energetic people already here. Even today, it is impossible to estimate what all that is worth, especially during periodic bank panics when everything seems worth a great deal less. A creditor wants to get his money back, so he will only loan appreciably less than he thinks the collateral is worth; a nation's real worth is therefore considerably greater than creditors collectively will lend. The creditors, unfortunately, don't really know what the nation is worth, either, and they have learned not to believe a word of what a debtor tells them. A nation's credit is estimated by the creditor community, and the one thing they know for certain is whether the nation has a history of paying its bills. A debtor may walk around in rags, or his wife may wear diamonds. The lender ignores all that; the question is does he pay his bills, promptly and in full. If he does that, he will have credit, and if he doesn't, he hasn't a dime of credit. What's America worth, according to that standard? About twice what the creditor is willing to lend him, and even that is a guess. It's why shop owners drive Cadillacs and investment bankers marry movie stars; and recently, why everyone had an inflated mortgage. Finally, it's why Alexander Hamilton wanted to buy up the war debts of the state governments, and pay off the worthless Continental currency. William Bingham may well have got rich speculating on Continental currency, but who cares. It's a cost of doing business, ultimately designed to assure you of ample credit.

Under the circumstances, it is sometimes difficult to understand why Morris was so moderate in his demands for clauses in the Constitution. He certainly did insist on the federal unlimited taxing power, which did in effect pledge the entire credit of the United States in the repayment of its debts, right down to the last shoe-button. And he was thwarted in even his own ability to make the four (Pennsylvania, North America, First and Second) national banks permanent. In general, however, Morris and Hamilton relied on the private sector and on legislation, rather than seek the sovereign level of federal power in the Constitutional Convention. When you recall those bullets whizzing around at Fort Wilson and at Yorktown, this level of self-restraint is rather remarkable.

Sanctity of Contracts

|

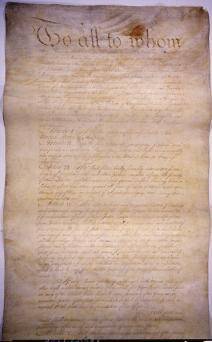

| Constitution |

THERE is little doubt many state legislatures behaved in a capricious and high-handed way in the twenty years prior to the 1787 Constitution. Outrage at this behavior was one of the important stimulants to writing the Constitution, as well as putting public pressure on state legislatures to ratify it in 1788. Section 10 of Article 1 is devoted to limitations on state behavior deemed to be generally offensive or otherwise contrary to the national interest. Among the comparatively short list of absolute prohibitions is found "No state shall......, pass any law.....impairing the obligation of contracts, or grant any title of nobility." This section condemns certain behavior as indefensible but does not specify the Federal government to be similarly limited, along with the states. However, the government which was established as one of the limited federal powers. Unless a power was specifically granted to the Federal government, the Tenth Amendment announces it belongs to the states, or, as the Ninth Amendment would have it, to the people. There seemed no need to limit the scope of a power which could not exist. The Tenth and final Amendment in the Bill of Rights ended the 1791 Constitution with the words:

X. The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

A modern capsulation might be: the Federal Government is no more empowered to impair the sanctity of contracts than it is to grant titles of nobility.

The Framers of the Constitution were inexperienced in the habits of a republic, or they might have anticipated the general tendency of those who are empowered to enforce the law, to flout it in their own behavior. Around the smallest courthouse in the nation, one need not be surprised to find the Sheriff or other local worthies, parking their cars in illegal spots without fear of punishment. It is not just state legislatures who are tempted to disobey the laws they pass, but a general tendency of all authority to do so. It requires a local citizenry with a very short fuse, displaying instant hostility to the first sign of this sort of swaggering, to keep their local newspapers from filling up with scandal stories in the weeks before an election. Many of these stories are politically motivated, of course, but it must be admitted that in a naughty world, they are necessary.

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility. No State shall, without the Consent of the Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing it's inspection Laws: and the net Produce of all Duties and Imposts, laid by any State on Imports or Exports, shall be for the Use of the Treasury of the United States; and all such Laws shall be subject to the Revision and Control of the Congress. No State shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any duty of Tonnage, keep Troops, or Ships of War in time of Peace, enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State, or with a foreign Power, or engage in War, unless actually invaded, or in such imminent Danger as will not admit of delay.

|

| Article One, Section 10 |

A 21st Century illustration is found in a letter sent to current beneficiaries of Social Security, reducing their monthly check by twenty or more percent in some cases, and in other cases just a few dollars. The notice says that this deduction is based on IRS reports of the individual's income, using material supplied by the Internal Revenue Service, thereby triggering an additional side question about the right of the government to use supposedly private information to impair the obligation of the Social Security contract. Setting the privacy issue aside, what is illustrated is an even more discouraging violation of the expectations for fair dealing. This is a privacy right which might have been enforced by an excruciating repetition of the time-consuming requirement of manual specification. Now that computers are more common, what formerly needed no specification, now perhaps begins to need it, since endless repetition is now so tediously conventional.

Governments casually violate the sanctity of contracts when it is self-serving to do so, and presumably, it can be shown that they neglect to violate, or even punish those who violate, whenever such violations are to the advantage of anyone else. It has been said that this matter has been adjudicated in favor of the government in the past, thus creating a precedent, stare decisis, so to speak. Whatever the logic of such precedents, growing Constitutional literacy among the public is going to demand that the matter be re-argued. That is to say, it is comparatively easy to imagine growing knowledge about the Constitution among the citizens, while it will never be easy to expect the public to puzzle through the steps in a judicial chain which explicates how the reverse is now a superior view. Therefore, the demand for re-argument should be a growing one.

Implicit Powers of the Federal Government

<The two highest achievements of James Madison, had been and still remain, the writing of the Bill of Rights, and acting as a close collaborator with George Washington in fleshing out the role of the President in the new government. The Ninth and Tenth Amendments made it clear that the federal government was to be constrained to a limited and enumerated set of powers, while all other activities belonged to the states. This was already clear enough in the main text of the Constitution, which Madison also dominated after close consultation with Washington before the Constitutional Convention. So he had battled and successfully negotiated one matter twice, before the most powerful and distinguished assemblies in the nation. As to the second matter, circumstances had promoted a shy young bookworm into the role of preceptor to the most famous man in America. In the earliest days of the new republic, certainly during the first year of it, Washington and Madison worked closely together in defining the role of the Presidency.

|

| George Washington |

During the first weeks of that exploratory period, Washington induced Congress to create a cabinet and the first four cabinet positions, even though the Constitution did not mention cabinets. It all was explained as an "implicit power", inherently necessary for the functioning of the Executive branch. Soon afterward, Alexander Hamilton as Secretary of the Treasury proposed the creation of a national bank. Madison and his lifelong friend Thomas Jefferson were bitterly opposed, using the argument that creating banks was not one of the enumerated powers granted by the Constitution. Hamilton's reply was that creating a bank was an "implicit power" since it was necessary for running the federal government. Of course, Hamilton and Jefferson both had other unspoken motives for their position: for and against promoting urban vs. rural power, for and against the industrialization of the national economy, and dominating the states in matters of currency and financial leadership. It empowered a national rather than a confederated economy.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

For Madison, the legalism probably carried considerably more weight than it did for Jefferson and Hamilton because it demonstrated the enduring consequences of being vague about the boundaries of any constitutional restriction. If this loophole got firmly established, it might reduce the whole federal system to a laughingstock. In order to promote the "general welfare", anything at all could be called an implicit power, and both separation of powers and enumerating federal powers would soon become quaint flourishes. The whole Constitution might fall apart in endless debates. On a personal level, Madison's highest achievements would have to be supplanted by something more practical. Besides which, Madison was a Virginian, a rich slave-holding farmer, and a young politician, seemingly on the verge of a promising career which might easily lead to the presidency for himself. Hamilton his most visible opponent, was already proposing a tax on whiskey which would almost surely antagonize farmers to the west, and assuming the Revolutionary debts of the states was equally divisive.

|

| Mt. Vernon |

As matters eventually worked out, the main disputants made ostensible constitutional arguments, while the real political dispute would be settled by a political deal struck at a dinner. It traded relocation of the national capital to Virginia, for the assumption of the debts of all states (when Virginia had already paid off its debt.) Location of the capitol opposite George Washington's home at Mt. Vernon also took care of difficulties coming from that direction. By the time the uproar about this arrangement subsided, the precedent for settling the inherent conflict between enforcing Constitutional limitations versus enlarging their boundaries had been set. The most opportune time for stricter interpretation was fading while the most likely advocates of it were restrained by their own example. The negotiation was a little unseemly, and probably encouraged similar decisions to migrate to a less conflicted body, which eventually John Marshall would define as the U.S. Supreme Court.

Morris at the Constitutional Convention

|

| Constitutional Convention 1787 |

TRUE, George Washington was the presiding officer of the Constitutional Convention. But Pennsylvania was the host delegation, so the role of presiding host should have fallen to Benjamin Franklin, the President of Pennsylvania. However, Franklin was getting elderly and turned the job over to Robert Morris, who among other things was rich enough to host some necessary parties. The rules of decorum at that time thus kept Washington and Morris out of the floor debates. The proceedings were, in any event, kept the secret, so occasional frowns or encouraging smiles are not recorded for history.

But Morris had been an active debater in the Assembly and other meetings, so he knew enough to line up a consensus in advance for the matters he thought were essential. Obviously, Morris was strongly in favor of giving the national government power to levy taxes for defense purposes, and Washington whose troops had suffered severely from the inability of the Continental Congress to pay them also regarded this taxing power as the central reason for changing the rules. By making it the central argument for holding the convention at all, Washington, Franklin, and Morris had made taxation power a foregone conclusion. And by giving them what they wanted from the outset, the rest of the convention was in a position to do almost anything else it wanted without open comment from the Titans. The sense of this trade-off was captured by Gouverneur Morris, the editor of the Constitution, in Article I, Section 8:

The Congress shall have Power To lay and collect Taxes, Duties, Imposts, and Excises, to pay the Debts and provide for the common Defence and general Welfare of the United States; but all Duties, Imposts, and Excises shall be uniform throughout the United States;This formulation had the effect of greatly empowering James Madison, the only participant who had studied the inside details intensively and cared about every comma. It also encourages the military to believe that federal taxation was mainly their entitlement, whereas those whose main goals are defined as "the general Welfare" tend to regard defense spending as an unnecessary deduction from their share.

|

| Pawn Broker Sign |

Most of the convention delegates had experience with state legislatures, and Franklin and Morris had spent decades struggling with the weaknesses of legislators. A wink or a quip in a tavern was as good as an hour's speech for reminding the delegates what they already knew about human nature. What was designed as a dual system of powers of taxation, with federal oversight of balanced state budgets combined with federal power to tax on its own in emergencies or unforeseen situations. Since the members of the first few congresses after 1789 were largely the same people as the members of the constitutional convention, many details of this balance were worked out over a few following years. State powers to tax and borrow were tightly constrained, only the federal government could tax and borrow without limit. Since government borrowing is merely the power to defer taxes until later, the borrower of last resort was the U.S. Congress, alone empowered to encumber the wealth of the whole nation in a federal pawn shop window called the funded National Debt. For almost two centuries, this pawn shop window seemed able to support any imaginable expense. Today, we monitor this as the ratio of national debt to Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and we now have a clearer idea what level of that ratio flirts with hopeless inability to pay the federal government's debt. The experts say it's close to a 60% ratio, and unfortunately, almost every nation on earth now exceeds that limit. The system continues to lack an unchallenged definition of its limit, but the system is nevertheless still Morris's system, wrapped in a mountain of descriptive detail by Alexander Hamilton. If a nation borrows more than that and clearly will never repay it, that nation is to some degree a slave to its creditors, with war its only hope if creditors are unrelenting. Perhaps another way to refine the thought is to say that if the nation wishes to mortgage everything it owns down to the last shoe button, the creditors will only accept additional debt if it is proposed by someone with the power to pawn the last shoe button. To foreigners, the proof of who has what power is much more certain if written down. Morris's protege Alexander Hamilton went even further: "credit" is established when creditors can see that somebody is in the habit of getting the nation's bills paid, and "credit" is injured whenever anyone in charge, welches.

Robert Morris, Financial Virtuoso

For reader convenience, we here divide Robert Morris' financial rescue of wartime America into two parts before and after 1780, because he had two episodes of being officially in charge. The first immediately followed the Battle of Fort Wilson when chaos and worthless paper money required a strong hand; it will be described next. The second episode followed the later near-revolt of the Continental Army but has already been outlined. Here, Morris was recalled to the office with chaos erupting at the end of the war came in sight and everyone was reluctant to fight battles for no military purpose. At the same time British, French and American politicians connived for victory in a war each had failed to win militarily. For simplicity, time sequences have been distorted a bit, concentrating the creation of modern banking into the second episode, where failure to coordinate banking with taxation ultimately led to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. Chronology has been sacrificed to enhance clarity. It is now time to return to the brilliant expedients Morris employed after he took charge following the Fort Wilson shocker, omitting some of the banking details already described.

What helped the first crisis most was the ready availability of a financial genius to turn around a crisis, when just about everyone else was at a total loss. Robert Morris had made his fortune, probably the richest man on the continent, and nursed the grievance of crowd abuse at the Battle of Fort Wilson. He had some novel concepts to test; it is not too much to say he showed them off, particularly since they displayed a man in charge with prodigious energy, applying a financial virtuosity of seemingly unlimited ideas. No one else came close to Morris in stature, and he must be forgiven for flaunting it a little.

|

| Robert Morris |

At the climactic moment, however, Morris played coy. He was not so sure he would accept the office of Financier, a term newly invented for the occasion. Accepting Ben Franklin's cynical assessment of the future, he wanted everyone to be clear: he was not going to give up his private partnerships. And he insisted on his right to hire and fire anyone at all within the government bureaucracy who was concerned with public money. He accepted responsibility for new debts of the government, but not for old debts incurred before he took office. He would furthermore delay taking the oath of office for a few months. These conditions naturally generated wild opposition in Congress; Morris was serene, and Congress finally had to agree. Most of these terms had some obvious purpose while making no secret of his distrust of Congressmen. In fact, the opposition might well have hardened its position if the purpose of delaying the oath had been fully expressed. Morris wanted to delay becoming a federal officer in order to delay resigning from the Pennsylvania Assembly. During the interval, he applied similar power tactics to the Legislature, ending up simultaneously in charge of both state finances and federal.

|

| Yorktown: Oct. 19, 1781 |

That purpose was soon to emerge, as just one instance of many tough tactics. Inflation tossed and turned the finances of everyone, so Morris would buy with one currency and sell with another, taking advantage of brief fluctuations, then quickly reverse the currency transaction when advantages shifted. He arranged with the French and Spanish ministers to keep their loans and foreign aid in separate accounts, applied the same techniques with state accounts, and even between near and distant counties within Pennsylvania. He thus had a choice between many currency values at any one moment. His far-flung commercial network supplied him with more precise information than his counterparties could get, and usually more quickly, so his trading activities were usually profitable. One rather extreme example was the arrangement with Benjamin Franklin in Paris; Morris would write checks to Franklin in one currency and Franklin would write identical deposits back to him on the same day but a different currency. He thus extended ancient practices among international merchants, carrying them over to government operations, which had the effect of creating a modern currency exchange. To outsiders, however, particularly his political enemies in Massachusetts and Virginia, it looked fishy. To modern observers, the astonishing thing was his ability to keep such complexity in his head. The political class which even today sees it as natural that governments might want to manipulate currency as they please might describe Morris strategies as dubious. Those who believe the market price is usually the true price however, must applaud this strategy for forcing manipulated prices back to market levels. Since here has rested the central dispute in American politics for two centuries, Morris must be credited with inventing even that dispute. One would normally suppose that doubling the silver price of American currency in two months would vindicate his trading strategy; but it has not always done so, suggesting the nature of the questioning has been more ideological than economic.

Within days of assuming office, the "legal tender" laws were repealed, stripping government of the ability to force its citizens to accept the worthless currency, impose rationing and price controls, and otherwise assume the mantel of "sovereignty". Like a miracle, food began to reappear in the Philadelphia marketplace at a lower price, and confidence in the competence of government began to return. To whatever degree the British ministry had been deliberately stalling the peace talks in the hope of American collapse, this incentive was dissipated.

The list of financial innovations which Morris produced in a remarkably short time, is seemingly endless. He next became central in the creation of the first American bank of the modern sort, the Bank of North America. And somewhere in that welter of activity appears to be the recognition of the so-called yield curve. Loans for a few weeks or months command a much lower interest rate than long-term loans; in the colonial period, almost all loans were for six months or less. Morris seems to have realized early that great profitability could be achieved by merging a sequence of several short loans into one long one. He thus devised a number of strategies which had the general effect of linking short loans together. Using the remittance for a transatlantic cargo in one direction as payment for the return cargo on the same ship was an early example. Once you grasped the idea and did it deliberately, long sequences of linked loans began to suggest themselves. Just to complete the thought, it might be noticed that present-day globalization reverses the process, with shorter-term loans for components substituting for longer-term loans for the entire assembled product. With lower interest rates, competitive prices can be reduced, unless a choice is made to increase profits.

There's one last issue in Robert Morris folklore: Did he finance the whole Revolution out of his own pocket? The answer is surely no because Beaumarchais ended up spending much more than any other individual, however involuntarily. The degree to which hard currency originated with the French, Spanish and American governments is a little unclear, and war damages are impossible to appraise. There were moments when Morris did personally finance major cash shortages, adding the considerable advantage of speeding up what could be a cumbersome process of budgeting, committee consideration, disputes, and hesitation. Where it was feasible, he sought restitution. Every bureaucrat has experienced delays and obstructions he dreams of eliminating by simply paying for it himself; Morris had the advantage that within reason, he could afford it.

As a very rich man, his more important personal contribution was his pledge to make good if the Treasury defaulted. Creditors generally preferred his credit to that of the government; his pledge was to pay if the government could not. His "Morris Notes" were not paying, but rather reinsuring government debts, in modern terms offering a Credit Default Swap. If we lost the war and our debts defaulted, Morris would have lost everything he had. But short of that, his pledge would result in much smaller losses. The public couldn't be expected to understand all that, so some simplified explanations were understandable. There were probably a number of similar examples, but near the end of the war, there was a particularly clear one. The Continental Army was very close to revolt when it looked as though Congress would disband the soldiers without paying them; there was no money but unpaid demobilization would likely send rioting soldiers through the countryside. Morris came forward with a million dollars of his own money and saved the day. Washington was forced to make emotional speeches appealing to the patriotism of the troops, but with most of the army barefoot, that was not certain to hold them back. Under those circumstances, to come forward later like Arthur Lee and remind everyone that Morris had once refused to sign the Declaration of Independence, was ingratitude of the meanest sort.

The accusation made after the war was that he profited from government losses, but there has never been evidence of that. His position was that he came out about even. Unspoken in these quarrels was the plain fact that until he got involved in the post-war real estate boom, he didn't need to cheat. Probably didn't even have time for it.

The Revolutionary War continued for two years after Morris took office for the second time, so war losses continued in spite of improved financial management. Both the French Government and the American one were at the edge of bankruptcy. Britain was also in political chaos, but it was only small consolation that Parliament had granted Independence to the Colonies when King George III remained adamant that it wasn't going to happen to his colonies. Strengthened by the British defeat of the French Caribbean fleet, the capitulation by the Spanish about Gibraltar, and great uncertainty about the Crimea and India -- almost anything was possible. Eventually, matters began deteriorating again. The British even then had the financial strength to hold out much longer, but obvious neglect of other opportunities eventually wore them down. Morris seemed to be winning, just by not losing.

In the midst of such anarchy, Morris had to admit his greatest failure as the Financier but was already formulating his plan for setting things on their feet. The Revolutionary War as seen by a financier had either been won by the British system of taxation or else lost by the American and French lack of such a system. It was irrelevant whether the War was described as a defeat for Britain or a victory for America; in Morris' view, the British had a good system and we had a poor one. No nation can finance a major war out of current receipts; you have to borrow. Your security for loans is the economy of your nation. Even if your illiquid assets are adequate for the war, the banking markets regard your ability to pay cash for the interest on the loan as their only reliable test of your solvency. That is, a nation at war must have the ability to keep the bankers happy with regular interest payments. For that, a nation had to have a proven system of reliable taxation. Britain had it, and the American/French alliance didn't. Franklin's masterful diplomacy was just lucky enough to achieve generous terms, but that wasn't good enough, we had to have a Federal tax system to survive and thrive. And to achieve that, we had to have a new Constitution. Never mind that resentment about British taxes got us into this mess. Never mind the chaos attending the Treaty of Paris. Never mind the war-weariness, bitterness, and destitution of the troops. Never mind that Morris was now about to embark on one of the most mind-boggling real estate ventures in history, was going to go to debtor's prison, was going to engage in millions and millions of dollars of borrowing and restitution. Never mind. We needed a new Constitution, and we were going to get it. Think big.

Morris Defends Banks From the Bank-Haters

|

| Robert Morris |

IN 1783 the Revolution was over, in 1787 the Constitution was written, but the new nation would not launch its new system of government until 1790. It was a fragile time and a chaotic one. Earlier, just after the British abandoned their wartime occupation of Philadelphia in 1778, Robert Morris had been given emergency economic powers in the national government, whereas the state legislatures were struggling to create their own models of governance, often in overlapping areas. While the Pennsylvania Legislature was still occupying the Pennsylvania State House (now called Independence Hall) in 1778, it -- the state legislature -- issued the charter for America's first true bank the Bank of North America, and in 1784 the charter came up for its first post-war renewal. Morris was a member of the Pennsylvania Assembly both times. Although he was not a notable orator, it was said of him that he seldom lost an argument he seriously wanted to win. Keeping that up for several years in a small closed room will, unfortunately, make you many enemies.

|

| Tavern and Bank |

Morris was deeply invested in the bank, in many senses. He had watched with dismay as the Legislature squandered and mismanaged the meager funds of the rebellion, issuing promissory notes with abandon and no clear sense of how to repay them, or how to match revenues with expenditures. There was rioting in the streets of Philadelphia, very nearly extinguishing the lives of Morris and other leaders, just a block from City Tavern. Inflation immediately followed, resulting in high prices and shortages as the farmers refused to accept the flimsy currency under terms of price controls. Every possible rule of careful management was ignored and promptly matched with a vivid example of what results to expect next. Acting only on his gut instincts, Robert Morris stepped forward and offered to create a private currency, backed by his personal guarantee that the Morris notes would be paid. The crisis abated somewhat, giving Morris time to devise The Pennsylvania Bank, and then after some revision the first modern bank, the Bank of North America. The BNA sold stock to some wealthy backers of which Marris himself was the largest investor, to act as last-resort capital. It then started taking deposits, making loans, and acting as a modern bank. Without making much of a point of it at the time, the Bank interjected a vital change in the rules. Instead of Congress issuing the loans and setting the interest rates as it pleased, a commercial bank of this sort confines its loans to a fraction or multiple of its deposits, and its interest rates are then set by the public through the operation of supply and demand. The difference between what the Legislatures had been doing and what a commercial bank does, lies in who sets the interest rates and who limits the loans. The Legislature had been acting as if it had the divine right of Kings; the new system treated the government like any other borrower. As it turned out, the government didn't like the new system and has never liked it since then. Today, the present system has evolved a complicated apparatus at its top called the Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, most of whose members are politically appointed. Several members of the House Banking Committee are even now quite vocal in their C-span denunciations of the seven members of the Open Market Committee who in rotation are elected by the commercial banks of their regions. Close your eyes and the scene becomes the same; agents of the government feel they have a right to control the rules for government borrowing, while agents of the marketplace remain certain governments will always cheat if you don't stop them. This situation has not changed in two hundred years and essentially explains why some people hate banks.

|

| Seigniorage |

That's the real essence of Morris's new idea of a bank; other advantages appeared as it operated. The law of large numbers smooths out the volatility of deposits and permits long-term loans based on short term deposits. Long-term deposits command higher loan prices than short-term ones can; higher profits result for the bank. And a highly counter-intuitive fact emerges, that making a loan effectively creates money; both the depositor and the borrower consider they own it at the same time. And finally, there is what is called seigniorage. Paper money (gold and silver "certificates") deteriorates and gets lost; the gold or silver backing it remains safe in the bank's vault, where it can be used a second time, or even many times.

For four days, Morris stood as a witness, hammering these truisms on the witless Western Pennsylvania legislators. At the end of it, scarcely one of them changed his vote, and the bank's charter was lost. But at the next election, the Federalists were swept back into the majority, defeating the opponents of the bank. Although, as we learn the way democracy works, still leaving them unconvinced of what they do not want to believe.

Two Friends Create the Articles of Confederation

|

JOHN Dickinson had been highly critical of England's treatment of its colonies. As early as 1768 he had written a book called Letters of a Pennsylvania Farmer which is credited with strongly influencing the colonies in the direction of resistance to the British Ministry. When it came time to write the Articles of Confederation, Dickinson was the lawyer selected for the task. His good friend Robert Morris had been less outspoken in opposition to the Ministry's behavior, quite possibly because he was adept at finding workarounds for his own personal business problems. But possibly he was merely maintaining an ambiguous negotiating posture, since in a hotly contested election with this as the main issue, Morris was elected by both sides in the argument. When July 4, 1776, forced the issue both Dickinson and Morris had refused to sign the Declaration, but within a few months both of them were actively fighting for the Rebellion. The truest test of their evolving attitudes might have emerged when Lord North sent the Earl of Carlisle as an emissary after Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, offering peace with a sort of commonwealth status for the colonies. Not much is written about this curious episode, leaving it unclear whether the British were serious, and even if they were, whether the Americans understood the offer as serious. On the surface, the British offer conceded taxation with representation as the rebellion had been demanding. But it was rejected by Gouverneur Morris acting for -- who remains unclear. It seems possible the British were exploring the true feelings of people like Dickinson and Robert Morris but were disappointed. The earlier treatment of Ireland after it had agreed to a similar half-hearted autonomy did leave British sincerity in legitimate doubt.

|

| Thirteen |

The thirteen colonies had united to fight the British King, but many of them were reluctant to unite for any other time or purpose. Rhode Island was perhaps the extreme example of this view of what Independence was supposed to mean, but the feeling existed to some degree in many colonies. Concern for the power of this feeling of tentativeness may have contributed an important reason the Articles placed heavy emphasis on declaring the document to represent a perpetual arrangement. Recognition of the weakness of this intent may have been an important reason why George Washington was later willing to sweep the issue aside, even though he of all people was most concerned to avoid the appearance of acting as an arbitrary king. For these and other reasons mainly revolving around state boundary disputes, the Articles remained unratified for years. Finally, in 1781 Robert Morris became convinced that failure to ratify was encouraging the states not to cooperate, and successfully pushed ratification through its steps. At that time, Morris was effectively running the country, even providing his own credit and funds to do it. People were reluctant to oppose his wishes, but they were also unwilling to provide the taxes, supplies, and troops that Morris imagined were being blocked by failure to ratify. Ratification of the Articles accomplished very little except to convince Morris: the Articles were flawed and must be replaced with something conferring more central power.

|

| The Goal: 1787 |

Little is known about the evolution of Constitutional thought in Morris' mind between 1781 and the Constitutional Convention in 1787, although a great deal is known about his other numerous activities. It is clear, however, that his experience with the recalcitrant Pennsylvania Legislature had been dismal, while he came to see the one insurmountable flaw in the current Federal government was its inability to levy taxes and consequently, to service national debt. The states were able to levy taxes under the Articles but erratic in doing so, resorting to paper money inflation at the first sign of tax resistance. In Morris' view, the key to the effective government was to reverse the situation; let the national government tax, let the states spend. The key to such rearrangement would be to permit the national government to spend on a very limited list of vital purposes, but bedazzle the states with a substantially unlimited shopping list if they thought they could afford it. As the accounts to pay for the Revolutionary War totaled up, it was apparent that the National Government had twice as much debt as the states. Therefore it would at most, need twice the state taxing power to service such a debt; presumably, wars would be infrequent and it would be less than that. Pay this one off, and potentially the need for future federal spending would be small. Indeed, under the presidency of James Monroe, the national debt was completely paid off, although briefly. It was almost as if Robert Morris and his pupil Alexander Hamilton had a crystal ball.

|

| Decline and Fall, Anyone? |

Robert Morris was brilliant and had six years to fashion his strategy, but he also had some help. For one thing, George Washington lived next door much of that time. By then, almost no one dared confront Washington. Adam Smith had written his book The Wealth of Nations in 1776, and Morris gave this extraordinary work as presents to his friends. Morris had corresponded with Necker, the genius financier of France, and through his good friend Benjamin Franklin, gathered insights from the rather advanced British national finance. And James Madison brought in scholarship about politics and statecraft accumulated by Witherspoon, Hume and the Scottish enlightenment. The year 1776 was a remarkable moment for new ideas. In that year, Edward Gibbon also published the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The warning behind that important book had an important impact on the minds of important thinkers of the era, too.

Once you grasped all the central ideas, in this environment the resulting strategy almost worked itself out.

Fighting About Taxes So Soon?

THE Constitutional Convention convened in secrecy, so the reasoning behind important provisions are sometimes unwritten. That is particularly true of taxation. Wars created the main reason for abrupt tax increases in the Eighteenth century, whereas present non-war expenditures are larger and steadier. For most people in any era, taxes have always been their main cash expense, but taxes are no longer synonymous with wars. An example of the way the problem has transformed over the centuries appears in Madison's notes, where Rufus King asks What is the meaning of a Direct Tax. The befuddled assembly answered with silence. No one present seemed to know, but since direct taxes were discouraged, perhaps it didn't matter.

Article 1, Section 8. Section 2: Section 9. Amendment 16 - Status of Income Tax Clarified (Ratified 2/3/1913) |

| The Constitution, on Direct Taxes |

It matters, of course, and leaving it unchanged suggests the Committee on Style either thought it sounded better than "taxing the states directly", or they didn't, and preferred a blurred wording. The purpose of neither changing the wording nor making further reference to direct taxes remains obscure. We are free to recognize that the two linked topics of Taxation and Congressional Representation (using a single verb and including a forceful "shall" for emphasis) announce a major trade-off was being explored, concerning a very sensitive point. The state legislatures were being asked to give up a power they had repeatedly abused, but they still had the power to refuse to ratify the proposed Constitution if the Convention started scolding them. In such a negotiation, all states immediately but privately calculate how much they are willing to pay for concessions, before being forced to take a vote. In the Eurozone negotiations currently being conducted today about a fairly similar issue, there is even deeper doubt about the actual ability of some nations to do what is being asked of them. There is thus the real reason for the Europeans to balance the financial books with something other than money. In the Eighteenth century American case, concessions on the slave trade were used as the surrogate bargaining chip. The Europeans have climate, religion, military position, language, and perhaps other things they could use, because it must be obvious to everyone that money bargaining could be conducted by accountants, with no need to involve chiefs of state. The early American experience seems to show that -- once a union is actually achieved -- income inequality between jealous states immediately began to seem less important, probably because after political union both money and people can pick up and move to a different part of the Union. Before the Union, it was all about money. Only two states fully paid their federal taxes during the Revolution, so problems collecting direct state taxes had been anticipated. To put it another way, New Yorkers do not greatly grumble about indirectly subsidizing Alabama citizens, but even today it would be politically dangerous to propose that New York State should pay a block grant outright (directly) to subsidize the state of Alabama. If enough latitude and diversity between the constituent states are allowed, however, individual persons and corporations can individually decide to move. Under those circumstances, the migration is effectively a plebiscite on the underlying governmental dispute.

An important diversion was created by trading away the tax issue in a compromise, seemingly having little to do with main concern about taxes. Madison's notes on the Convention record relatively little discussion of slavery, but there is every reason to suppose the matter was at the front of every Southern mind. Because George Mason of Virginia was known to be delaying matters for the seemingly specious reason of demanding a Bill of Rights, which even James Madison of Virginia could see no purpose to, Mason was the swing vote in the most powerful state delegation at the Convention. Mason almost jumped joyously at the potential resolution of the direct taxation problem in the form of: "Numbers of inhabitants, though not a precise standard of wealth, was sufficiently so for every substantial (i.e. Virginia) purpose." This was a considerable concession for the richest state of the thirteen to make, and it followed the ancient political advice about a trade-off that it seems to have nothing to do with the central issue in dispute. This is something the European debaters must learn: if you are at loggerheads about one issue, trade it off for something unrelated, and call it a compromise. Although Mason would undoubtedly have been gratified to escape a higher tax rate, he nevertheless rejoiced in the alternative of increased voting power by 3/5 of a vote for each slave. Since this was soon touted as the second great compromise of the Convention, he could detect the signals of a binding agreement which the South would exploit for fifty years.

|

| George Mason |

At this point in the proceedings, the Convention was still in a mindset of struggling to unify thirteen sovereign republics; naturally, each one also wanted to be sure the taxation was fairly distributed. Virginia not only wanted its own definition of fair shares, but it also wanted enough power in the House of Representatives to maintain that definition. It wanted to avoid any tampering with slavery, and both demands were now agreed to. Direct taxation of the states, with its inherent apportionment issue, was not explicitly linked, but it is hard to believe it went undiscussed. Except for the District of Columbia and the Territories, which are regulated by Congress in many unique ways, Congress now has no power to impose a direct tax upon a state, or otherwise to pick tax winners and losers. Everyone agreed that Congress needed to be able to levy a limited amount of taxes "for the common defense and the General Welfare", but many delegates were uneasy about the apportionment method used in the Articles of Confederation because short of military force there was no sure way to collect them. Going to war against one of the states for non-payment of taxes must have sounded very unattractive after a recent history of having eleven of the thirteen refuse to pay them. Anyway, we had a deal with regard to slavery. And seemingly for those reasons, Congress now has no real power to impose a direct tax upon a state. Rufus King might not have needed to embarrass everyone with his revealing question if the wording meant "impose a tax directly upon a state", because the Constitution says that of course you can, but as a practical matter, of course, you won't.

At present the issue of apportionment of taxes roils the European Community, although in a slightly different form, and they must find a way to solve it. Germany is unwilling to support Greece, the Netherlands unwilling to support the Belgians, and so on. The poor nations cry "fairness" while the rich nations proclaim "merit and hard work", and it was ever thus. Our founding fathers found the solution was to forbid the taxing of nations, except in proportion to the population. That is, to shift the tax from the national level to the individual taxpayer level. Doing so will not make national jealousies disappear, but here it proved to be sufficient. Texans would still rather lose their left leg than pay taxes to support Oklahoma, but when a dust storm or drought appears, Texans are immediately generous to their neighbors in distress. Within the past decade, a Texas law professor published a law review article denouncing the unfairness of a state with twice the population being forced to pay double the taxes. George Mason would have simply smiled and said, "Of course twice as many people pay twice as much tax. And get twice as many Congressmen, too." That's called square dealing, but square dealing is often not quite enough. Some land is not quite as fertile, some people are not as well educated, one state has more seaports than the other. To bring the scales into balance, something more must be added. In that case, it's best if what is offered has nothing to do with either taxes or congressional representation. That's called diplomacy.

And let's not forget one of the features of taxes. A major reason for national taxes has always been to pay for wars. Less of one usually means less of the other.

xxxMonetary issues in the Constitution

Click Here to Go On to Ratification, Bill of Rights and Other Amendments

Tax References in the 1787 Constitution

Article 1, Section. 8. Section 2: Section. 7. Section. 9. Section. 10.

|

| Tax References in the 1787 Constitution |

What Is the Purpose of a National Constitution?

|

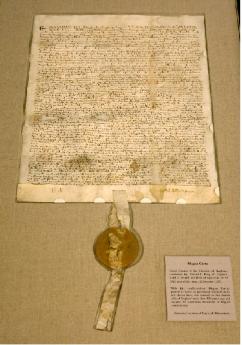

| 13th Century Magna Carta |

NATIONAL constitutions are mainly an outgrowth of the 18th Century Enlightenment, even though similar features are to be found among ancient legal codes. Those who trace the origins of the American constitution to the 13th Century Magna Carta will usually point to a central sentence of clause 39:

No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.

|

| American Constitution |

That's a pretty good beginning, a good example of a needed legal principle, but unrecognizable as what we would today call a Constitution. It states what a government may not do, but does not define the nature of a government which does the job best. Nor do even the many Enlightenment philosophers of government take that final step of outlining where their notions should take us until the American Constitution had been written and defended in the Federalist papers. Nowhere among the writings of Montesquieu (The Spirit of the Laws, 1748), Catherine the Great (Nakaz, Instructions to the All-Russian Legislative Commission, 1767), Diderot (Observations About Nakaz, 1774), James Madison (1787), John Dickinson(1763) or Gouverneur Morris(1787) can there be found much tightly described definition of a constitution. Certainly, there is no definition within the writings of Adam Smith if we look for rule-making among Enlightenment thinkers whose ideas were influential on the 1787 Philadelphia document. The American constitution was the product of many minds, before and after 1787. The outlines of its final form converged, and emerged, from the Constitutional Convention of the summer of 1787, with Gouverneur Morris as the penman of record. To him, we certainly owe its succinctness, which is the main source of affection for the document. That probably understates matters; in his diary of the secret meetings, James Madison records that Gouverneur Morris rose to speak about 170 times, more than any other delegate. Lots of thought and debate; ultimately, few words.

The Elizabethan Sir Francis Bacon has the greatest claim on devising a theory of law and law-making in the Anglosphere tradition. But his elegant modification of Galileo's scientific method, the English Common Law, is more a methodology for creating good laws than an outline of a nation's legal principles. Anyway, tracing the American Constitution back to an underlying British one tends to stumble when the British Constitution fails to meet a definition which would include our own. The British Constitution is said to be "unwritten" to the degree it is a consensus of revered documents. It can be amended by Parliament at will, has a variable history of defining just who is covered by it, and in order to define constitutional principles seems to rely on sentences extracted from difficult context. If the two constitutions had been written and compared at the same time, one would say the British had sacrificed coherence out of respect for tradition. In fairness, some features of the American constitution are also perhaps unnecessary for every constitution, but by surviving as the oldest constitution of the modern form, have become its model. That would be:

A set of principles governing the legitimacy of a nation's laws, and firmly standing above them. It defines its own domain, geographically and by the membership of a defined citizenry. Except as otherwise defined, it supersedes all other governance within its domain. It defines and defends its own origins. It includes a description of how to amend it, which is intentionally infrequent and difficult. It goes on to outline the structure of the laws it regulates, with subtle modifications made to channel the type of power structure which will govern.

In the American case, history and culture generated several other instabilities so central they justified heightening the difficulty to amend them to a Constitutional level, thus conferring undisputed dominance over competing principles of governance. That would be:

A separation of government powers weakened all potentially offending branches of government, and thus enhanced citizen liberty. Separation of church from state, for like purpose. A right of citizens to bear arms, to strengthen citizens' defense against internal or external attack, and perhaps also warning that revolt must be possible, even endorsed, as some final extremity of protection for citizen sovereignty.

|

| Russia's Catherine the Great |

It enhances our comprehension to contrast the outcomes of competing 18th Century implementations of the Constitution idea. Russia's Catherine the Great proposed a constitution steeped in the traditions of the Enlightenment but ultimately designed to define and strengthen the role of the monarch. Denis Diderot her French protege recoiled at this viewpoint, substituting other views resembling those of Jean Jacob Rousseau. He opened Observations About Nakaz his commentary to the Queen, with the following declaration:

There is no true sovereign except the nation; there can be no true legislator except the people. Whether looking back to the English Civil War or forward to future disputes between the Executive and Legislative branches, it makes clear the Legislative branch was dominant, with the Executive branch acting as its agent.

|

| Denis Diderot |

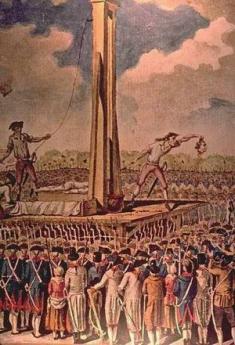

With this ringing warcry, the French model nevertheless ushered in the extremes of the Terror, the Guillotine, and the Napoleonic conquests. The consequences of the French constitution undermined world confidence in the benevolence of public opinion, at least deeply confounding those for whom the democratic rule was not totally discredited. Once more new life was breathed into allegiance for the monarchy, military rule, and dictatorship. Public opinion, it seemed, was not either invariably benign or comfortably far-seeing. The noble savage, mankind naked of tainted civilization, was not necessarily wise or worthy of trust. Edward Gibbons, the 1776 author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was pointing out where it all might lead if we completely believed in the collective goodness of the human condition. At the least, the failure of the French Revolution complimented the viewpoint of the Scottish philosopher, Adam Smith, who also in 1776 emphatically urged a switch in that reliance toward a sense of enlightened self-interest, as follows:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest.

|

| Terror, the Guillotine, |

It is not surprising that Diderot rejected the Leibniz view of things that "All is for the best, in this best of all possible worlds." And, in view of his dependence on Catherine, not surprising he did not publish his rejection of it until 1823. Thomas Jefferson was in France as ambassador during the time of the American Constitutional Convention, fearing to confront George Washington; and likewise keeping his conflicting views private for several years. Eventually, they surfaced in the creation of an anti-Federalist political party along with the conflicts which kept the new nation in a turmoil for the following forty years. It is surely a testimony to the strength of the Constitution's design that the country was able to shift between such extreme governing philosophies but still hold together without changing the governing statement of purpose. Indeed, it is plausible to contend that our two political parties still continuously debate the useful tension between these two differing opinions.

Penman of the Constitution

|

| Gouverneur Morris |

THE Constitution is the product of many minds, its ideas have many sources. But final phrasing of the unified document can largely be traced to a lawyer, Gouverneur Morris. The Constitutional Convention would announce a topic, argue for days about different resolutions of it, and then vote on or amend a composite resolution ( unless the matter was deferred to another day of earnest wrangling.) After months of deliberation, that jumble of resolutions made quite a pile. The Convention then turned it all over to Gouverneur Morris for smooth editing and uniformity. Although Morris had arrived a month late for the Convention, he still had time to rise and speak his views more than any other delegate, 173 times. But comparatively few of his ideas identifiably survived the voting; by Convention's end, the delegates were most likely listening for elegance and poise, increasingly expecting the final edit to be his. He finished the task in four days, and the full convention only changed a few words before accepting it. This assembly needed a lawyer who would sincerely follow the intent of his client, rather than yield to the slightest temptation to warp it with his own views. The convention had heard his opinion about almost everything, were thus alerted to uninvited slants. He gave them what they asked for, wording it for persuading the nation, as he himself had been persuaded by what the delegates wanted. The remarkable degree to which he had faithfully served his client's wishes, rather than his own, only emerged twenty years later. During the War of 1812, he disavowed the Constitution he had written.

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

|

| Preamble to the Constitution |

Morris mostly shortened what the delegates had said. A word here, a phrase there, sometimes whole sentences were removed. After that, rearrangement, and substitution of more precise verbs. This lion of the drawing room, this duelist of the salon, undoubtedly had an enjoyable time twitting his less accomplished clients with brisk capsules of what, of course, they had meant to say. To remember that he was outshining Benjamin Franklin and most of the other recognized wits of the continent, is to savor the fun of it all. Of all people in the Enlightenment, Franklin was certainly Gouverneur's equal in sparkling exchanges of debate. Here, he did not even try.

|

| John Peter Zenger |