2 Volumes

Tourist Trips: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

The states of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New Jersey all belonged to William Penn the Quaker in one way or another. New Jersey was first, Delaware the last. Penn was the largest private landholder in American history.

Quaker Philadelphia 1683-1776

New volume 2012-11-21 17:33:18 description

Litchfield to Wilkes Barre, Today

The journey of Connecticut's invasion path into Pennsylvania has changed little in two centuries. But some pretty important history has since taken place along that route.

Litchfield's Past

|

| King Charles II |

The state of Connecticut absolutely loathes the idea that it is influenced by neighboring New York City. But Greenwich is full of hedge funds escaping high taxes, unfortunately not by very much. New Canaan is what Greenwich used to be, a snooty New York suburb. And Litchfield seems destined to be next in line, but still able to deny it. It's charming, neatly manicured, but still affordable. Young investment bankers think of buying a weekend home there, which will become New Canaan or Greenwich by the time they retire, which on Wall Street is often sooner than they guess. Meanwhile, the restaurants struggle to present an upscale appearance. The local law school claims to be the first in America. In spite of civil appearances, however, this is the town that decided to invade Pennsylvania on three different occasions, provoking massacres of several hundred people. Litchfield derives from Lichtfeld, a place where heretics are burned. When those dreadful Baptists from Rhode Island made an appearance, the local Congregationalists were ready to take a stand. The borders of Litchfield once extended west to Wilkes Barre, but it is still puzzling to ask how these invaders crossed the Hudson and Delaware Rivers. Or how settler families marched through what is still pretty much a barren wilderness. All the while, telling themselves their destination was a paradise when even neighboring Scranton today looks down its nose at Wilkes Barre. What is this invasion trip like today, and why in the world would the Connecticut Yankees have changed it, three times?

|

| King Henry IV |

Those Yankees were almost certainly indifferent to the magnificent scenery offered the traveler of this path, especially when the fall foliage is awe-inspiring. George Washington's headquarters was to be located later at Newburgh for longer than at any other place, and thus it became the first national park monument in the country, lying across the path of the largely forgotten invaders. Unfortunately, hardly anyone even today in Connecticut knows what was notable back then, or cares to learn. Connecticut may make its living on Wall Street, but in a spiritual sense, it faces Boston. Curators at the National Park at Newburgh likewise know nothing of the Pennamite Wars. Restaurants have difficulty summoning up a hamburger; the motorist must pump his own gas. But there are clues; at least six different towns along the invasion route call themselves Milford, or New Milford, or similar. The postal service frowns on using the same name twice in a single state, else surely there would be more Milford. There are other clues. Near the end of the trip to the Wyoming Valley, can be found the "Promised Land Park". It's just past a place called "The Lord's Valley". Not far away can be found in the town of Dallas. Just why did Wilkes Barre name so many things after other places far away?

|

| White Flower Farm |

Perhaps the law school has something to do with it. Charles II of England had given Connecticut all the land to the Pacific Ocean when it was all wilderness that just about nobody wanted to own. Eighteen years later, the same king gave the same land to William Penn. Any modern lawyer, and maybe those backwoods lawyers three centuries ago, would tell you that if the King gave it away, it was no longer his. But Penn went to court with the complaint that the present king had just given it to him, and the court agreed that Penn could call the Sheriff to throw the Connecticut people out. Modern citizens would suspect bribery or other foul play, and perhaps the Yankees did, too. After all, ancestors of that King had badly mistreated some of their ancestors, so perhaps he held a grudge. Unfortunately, that's not how the law saw things at the time, and it's not entirely likely the Connecticut Yankees were being calm and straight about it. The fact was that Connecticut farmland never had much topsoil, and by this time it was worn out. Population growth pushed, and some fanciful tales of Wyoming (now Wilkes Barre) Valley's abandoned richness, pulled. They needed it, they wanted it, no one else was using it, the owner was already rich enough, and -- King Charles, that rascal, had given it to them.

The Connecticut Yankees liked to read books, so let them read Shakespeare. The so-called Henriad, those four plays concerning Henry IV and V in the 15th century, describes accurately how the King of England owned the whole island, by inheritance and by force of arms. Those nobles who followed him and brought along enough troops to win battles were each given a piece of the kingdom. But if, as quite regularly happened, one of the nobles betrayed or displeased the King, he lost his head, and his land was given to someone else. That's what it meant to be the King, and that's still largely the way it was in the Seventeenth, even early Eighteenth, century. It's true the Barons forced a king at Runnymede to obey the laws himself, Parliament asserted itself in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth centuries, the open country began to be enclosed for private ownership in the Eighteenth century -- and the fellow colonists in America would ultimately break loose from England to extend these property rights further, until in 1787 the Constitution made it final. But that's a long way from saying King Charles II couldn't do what he pleased at the time he did it, and how many girlfriends he happened to have was irrelevant to the case. William Penn was a better lawyer than anyone in Litchfield and won the case every time it came up.

And furthermore, the Connecticut folks were out of step with their friends. Eleven of the colonies were fighting for independence, and George Washington was not alone in despairing that the other two colonies were fighting, not the British, but each other. Litchfield may now have the most beautiful flower farm market in America, but at the other end of the same street, the professional forebears of the Litchfield Law School were once giving poor advice.

Newburgh NY: Washington Slept Here

|

| Newburgh, NY |

A silhouette map of the Hudson River from top to bottom shows several stretches of narrow river between several other wide stretches, almost like lakes. The narrows reflect the places where mountain ranges broke apart to let the river through, and the lakes are places where the water backed up until it got high enough to flow through the gorges. There's not much water pressure since the Hudson at the mouth of the river at New York Bay is only a few feet deeper than it is at Albany. Ben Franklin was the first to observe that the Hudson and Delaware are not exactly rivers; they are more like fjords, tidal up to Poughkeepsie and Marcus Hook, respectively. The Dutch had a settlement at New Amsterdam, of course, but there was another settlement around the Tappan Zee, and another cluster above West Point. Kingston was the dominant town of this upper settlement, but the British had burned it to the ground after their defeat at Saratoga in 1777. In 1782, Washington chose Newburgh to be his headquarters, where he remained for 16 months, the longest headquarters interval during the eight-year guerilla war.

|

| Storm King Mountain |

As always, Washington made excellent use of geography. The Storm King Mountain and West Point to its south narrowed the water route to New York down to a defensible defile. On the east side of the Hudson, the towering ridge not only protected the encampment from surprise but provided a lookout point at Beacon, where television towers now stand. The land is broken and semi-mountainous on the east side of the Hudson, all the way into Connecticut; an extension of difficult terrain which on the south crosses the Hudson and extends west into New Jersey. Reduced to its essentials, the British in New York and Washington in Newburgh were separated by a mountain range with a Hudson River water gap running through it. Immediately to the west beyond Newburgh however, the land is fairly flat until it rises to the watershed of Delaware. Washington could defend the Hudson against the British Navy at the narrows, eventually blocking the channel with a chain which was sufficient barrier to sailing vessels if they were vulnerable to cannon fire from the shore. If there was a land attack sweeping around behind Newburgh, Washington could escape by sailing up the Hudson; in that case, he would have boats and the pursuing British Army wouldn't. Such a daunting natural fortress was adequate for his situation since the British were equally reluctant to sustain casualties in frontal assaults so late in the war unless victory was fairly quick and easy. This was the general issue underlying the Benedict Arnold affair: blocking the British Navy from making a landing north of the watergap.

|

| Battle of Yorktown |

After the battle of Yorktown, the British could see there was no hope of subjugating large colonies using armies mostly supplied by sea. The Revolution settled down to attrition at sea, but the American privateers were winning that, too. Eventually, more British were lost to privateering than to warfare on land. The colonies were learning how to supply themselves with manufacturers, while the British were losing substantial amounts of trade with other parts of the Empire. Franklin in Paris was counting on Washington to maintain a credible threat; Washington was counting on Franklin to drive a hard bargain, but hurry up, please, our troops haven't been paid and are restless. The privateers were both suffering and inflicting appalling losses at sea, but their owners were getting rich. Most of the early great fortunes of Federalist America trace their origin to privateering. All of these emerging realities presented a bleak future to the British, and Franklin was masterful in rubbing it in. But if Washington lost control of his little army, a great deal more would be lost at the treaty negotiations.

Washington's Circular Letters

ONCE Cornwallis surrendered to Washington at Yorktown in 1781, there emerged the usual reluctance of troops on both sides to get killed for a dispute that was already settled. The British monarchy had ample experience with wars and fully expected to exploit this trait of exhausted soldiers at the end of one. It was clear to the British the colonies could neither be reconciled nor forcibly subdued. What was not clear was how much national advantage might still be extracted from a peace conference. Bluffs and intransigence might still achieve what bayonets could not. Seasoned diplomats are accustomed to such manipulation, but the new American nation only had Benjamin Franklin grown equal to it, representing Pennsylvania and Massachusetts with the British Ministry for several years. Beyond that, however, a particularly American trait was emerging to quit the game before the last card is played. During the Nineteenth century, anticipating and resisting that irresolute temptation came to be called, Character.

The American Revolutionary Army was seldom well-fed, never well armed. Hardly anyone expected a war lasting eight years, or the British regulars to be so mean and effective. Major General Benedict Arnold had seemed like our perfect soldier but turned traitor while in charge of a major defense position at West Point, New York. Conditions for wives and children at home were bad. And the Congress in Philadelphia was willing to inflate the currency, hold back soldiers' pay, pinch pennies on supplies. Other colonies frequently promised to send more soldiers than they actually supplied. Not that they were proud of themselves; they skulked. Surely, some state legislatures and representatives were better than others, but they are almost impossible to identify, now. They all must have been somewhat complicit, or we would have heard more of them denouncing each other. It must have been supremely painful for Washington to receive promises of troops and supplies that he privately doubted, and then to be obliged to assure his troop's help was forthcoming. Inevitable disillusionment discredited him more than the Governors who put him in that position. The British troops surely shared their enemy's reluctance to get killed for a war that was over. They partied and roistered in New York, but who knows what general in London might suddenly order an attack on Washington at Newburgh, just to make overall British defeat seem less humiliating.

|

| Headquarters, Newburgh NY |

During sixteen months of this agony, Washington wrote many letters to state Governors, keeping them informed while asking for their help. The custodians of the Headquarters museum proudly show the various tables and chairs for his aides to translate French and Spanish, to make thirteen copies of just about everything, and careful files of all correspondence. Washington was an organized person, they say, or else his chief of staff was organized. Someone like Alexander Hamilton, perhaps. Out of all this headquarters communication system gradually emerged the system of Circulars. The General was in a position to see huge deficiencies in the government system for which he dedicated his life, and apparently grew haunted by the idea that all this suffering would be for nothing if the government which emerged was anything like what he was now seeing. His Circulars to the governors began to take on the style of outlining what kind of government the United States ought to have. It must, for example, acquire federal power; the states must turn over more of their own power to the decisions of a single executive. It must pay its debts; a mighty nation does not chisel its creditors. It must suppress the inclination to squabble and think the worst of one another. It must, in his phrase, be virtuous.

Two emphatic views of the new country emerged from Washington's time in Newburgh. The inability of the government to pay its soldiers, suffering or no suffering, was particularly agonizing. And the close call he had with threatened mutiny made it much worse. Robert Morris had run out of tricks and instructed him the central issue was for the Federal government to be able to levy taxes for servicing the debt, which would make it possible to borrow still more through leverage. Washington never forgot this episode, and at several points, during his later presidency, it guided him well. The other episode which made a lasting impression was to some degree his own fault. He was so impassioned in his hatred of monarchy that his closest friends, Hamilton and the two Morrises -- who had never seen much to criticize in a monarchy -- essentially gave up on trying to persuade him, and took the side of General Gates the hero of Saratoga in a planned mutiny. Washington put it down with nothing but the power of his personality and a little play-acting with his bifocals, but he almost lost the confrontation in an instant. Washington had many close calls with death on the battlefield, but these two near-defeats pretty much shaped the rest of his life as our first President. Indeed these two hatreds, of debt and monarchy, continue to characterize many Americans to a degree that others would describe as unreasonable.

And then he made a mistake. As a way of proving his lack of personal motive, he announced in advance he would be leaving public service forever. Today, every lame duck knows that's a bad idea, even when you mean it. And while he may have sincerely thought he meant it at the time, events show he really didn't. Although he probably didn't want to be indispensable, circumstances made him so. He discovered how little he knew of the technical details of government, and thus how much he needed James Madison's help. Washington lacked skill in managing finance; having depended on Robert Morris throughout the war, he needed Alexander Hamilton at least to handle a peaceful economy. But there was no running away from the central issue; he would be forced to recognize how much he overshadowed anyone else in demeanor, and so, how unlikely it was that anyone else could bully others into cooperating. He was a great-souled person, in Aristotle's phrase. Franklin alone perhaps understood and privately doubted that even Washington could pull it off. Washington's Circulars were driving him straight toward seeking the Presidency he widely proclaimed he did not want and would not accept. And thereby he threatened the one thing in life he prized more than any other: his word of honor to keep his promises.

Dingman's Ferry, Below Port Jervis

|

| Dingman Ferry Bridge |

Because the area was once covered with a glacier, the northeast corner of Pennsylvania is fairly deserted. That's always been good for hunting and fishing, and more recently is good for skiing. Although the topsoil is poor, it's a beautiful area, practically guaranteed to provoke confrontation between the environmentalist movement and the Marcellus shale-gas extraction industry. The history of anthracite coal demonstrates locally that the mineral extraction industry always wins these arguments in the short run, but ultimately the land seems to heal itself without much help from people living in city apartments. The followers of Gifford Pinchot and Teddy Roosevelt are slowly learning to concentrate on minimizing the damage and forcing the extraction industries to pay for clean-up afterward. Right now, this semi-wilderness area is a remarkably beautiful but deserted forest within two hours drive of Philadelphia and New York City. It contains the headwaters of the three main rivers of Northeastern United States.

Crossing those three rivers was the main geographical problem for the Connecticut invaders of Pennsylvania. Today, the landscape is not a great deal different except for the absence of Indians, and crossing the three rivers is the main event. There's a Hudson River bridge at Newburgh, and crossing the Susquehanna at Wilkes-Barre is a placid bridge within a town park. From the point of view of the Interstate highway, crossing Delaware occurs very near the highest point in New Jersey, over a deep rocky gorge with boaters deep below. Since the traveler is at a peak point within a long wide mountain valley, the view is spectacular in several directions.

However, for centuries the builders of roads had to operate on a modest budget, and the only reasonable place to cross Delaware in that region is a few miles south of Port Jervis, at Dingman's Ferry. The Dingman family prospered at their trade for many generations before they modernized and constructed a toll bridge, which is now one of the few remaining toll bridges in private hands, and possibly the oldest one. You don't have to ask the two jolly old toll collectors whether they are part of the Dingman family because they certainly act like it, adding to the wad of dollar bills in their left hand as they greet the fellas, josh the girls, and wave directions with a free hand. A quarter-mile to the south of the bridge on the Pennsylvania side is the entrance to a trail leading to a National Park Service station. The Park Guards are a friendly sort, most of them freely admitting they are members of the Dingman clan, available to help tourists interested in a trail walk, including a visit to the local waterfall. In spite of all this family connection, and Park Service training, nobody at the station had ever heard of the march of the Connecticut invaders. Or of the Proprietorships of West and East Jersey, or of the line between them which allegedly ends at Dingman's Ferry. The best they could do was the point to the local cemetery, which has a big rock at the entrance that somehow has some particular significance, or other.

As it turns out, the cemetery is quite large, with surely a thousand or more gravestones, a great many of which fly American Legion flags for veterans of one war or another, and many more are decorated with fresh flowers. Only a corner of this graveyard touches the curving road to The Bridge, and just inside the entrance is a very large, unmarked stone. Trees have been planted nearby, and their roots have half-covered the rock. But the roads and the cemetery, in general, seem designed around it. There's no marker to explain it, any more than there is a plaque at Stonehenge. As the Park Ranger said, it has clear significance, but no one now seems to know what it is significant of.

Well, if no one is likely to contradict, let's make the timid suggestion that this may be the terminus of the line dividing East from West Jersey. Yes, it's in Pennsylvania. But there is nothing more likely on the New Jersey side of the crossing, and the current Surveyor-General of West Jersey, William Taylor, is firm in the belief the line terminated at Dingman's Ferry. William Penn had hoped to control land on both sides of the river, and when he acquired Pennsylvania in addition to New Jersey, the issue became moot. The style of the survey had been to start at Beach Haven ("Ye inlet of ye beach of Egg Harbor") and follow the compass until it hit something large and heavy. That rock was marked, and another survey went the next step. About fifty of these markers have been discovered by later explorers, and officially represent the underlying fixed line which serves as a survey basis for every property in the state of New Jersey. Since I own some property in New Jersey myself, it seems important to be sure I know where it is, or else some trial lawyer may try to take it away.

Wyoming, Fair Wilkes Barre

|

| Wyoming Valley |

There are a dozen or so places on the planet where a natural bowl formation famously moderates the climate. Cuernavaca in Mexico, the Canary Islands, and Chungking in Western China all claim to have temperatures which range from 70 to 75 degrees Fahrenheit, year-round. In Cuernavaca at least, they claim it only rains at night. These three places have a high plateau in the center of a mountain bowl, like an angel food cake pan, which may (or may not) contribute to the unusually mild climate effect. Several other places within inner China compete for the title of Shangri La, famous in song and story, never precisely located by tourists. The Wyoming Valley of the Susquehanna River once enjoyed a similar luster during the Romantic Period at the very beginning of the Nineteenth century, although unfortunately, its temperature is plainly not so balmy. Wyoming of song and poem was imagined to be the home of the Noble Savage, unstained by the wayward influences of civilization, and thus a model for the democratic ideal expected to emerge in Old Europe once the aristocrats were exterminated by nature's noblemen, European version. That seems to have been Robespierre in France, as disappointing to idealists as the Iroquois along the Susquehanna.

|

| Massacre Monument |

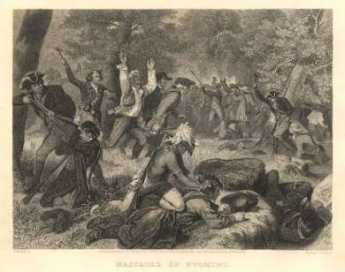

But one must not scoff. The Wyoming Valley was created long ago by a lake between two mountain ridges, which gradually dried up leaving flat topsoil deep at the bottom of the valley when the river finally broke through at Nanticoke and drained it. Its appearance is enhanced by surroundings in all directions of at least fifty miles of bleakness. Nowadays, the best way to appreciate the natural beauty of the place is to arrive from the south, gaining the summit of the ridge by one of the secondary roads. Housing development down below stops at the edge of the level plain, so as one ascends to the southern rim it is possible to see the inside of the bowl without seeing much of the town, and thus appreciate how it must have looked to frontiersmen searching for likely places to settle. It's quite beautiful. Descending into the bowl, the potholes in the road and roadhouses along the way to begin to make an impression. In full sight, it looks as though a city suburb has filled the place to its edge, with a rather decaying Nineteenth-century town center, but towering wooded mountainsides. There's a quiet park in the very center, through which the quiet river runs. In a little subdivision named Wyoming, there is a monument to The Massacre, now described as a hopeless defense by untrained Revolutionaries against the fearsome Indians and British Loyalists. The names of the fallen and the names of those who escaped are carved on this monument near Forty Fort. One presumes the wounded and some bystanders were massacred, the officers and trained infantry were more likely to escape the hopeless odds by fleeing into the woods. It is claimed that common soldiers were finished off by Indian Queen Esther smashing their heads between two flat rocks. Wounded officers were tortured to death.

|

| Delaware Water Gap at Stroudsburg |

Just where the Connecticut immigrants, or invaders, first arrived in the Wyoming Valley is not known. Their most likely entrance was at the top of the northern end of the valley, where ski lodges now cluster, after coming up the mountains from the east. The hills rising from the Delaware watershed are wooded but too rocky for farming. It's therefore inexpensive to set aside parks named "Promised Land" and "The Lord's Valley" and such, with some Milford, scattered here and there in the woods. A section of the upper Delaware River fifty miles long, from Port Jervis down to the Delaware Water Gap at Stroudsburg is enclosed in a National Wildlife and Recreation Area of about a mile's width on either side of the river. It's surprising how little is said of this rather large national park close to two large metropolitan areas. No doubt the visitors are torn between wishing it was more appreciated, and hoping to keep it secret and unspoiled.

|

| Wyoming Massacre |

The Decision of Trenton(1782) simply gave the disputed land back to Pennsylvania. There is a strong presumption the Connecticut migrants were privately promised land in the Western Reserve, in Ohio, whenever Ohio became a state. In spite of the implicit guarantees, the Pennsylvanians nevertheless treated the usurpers pretty roughly, and traces of Connecticut trail westward toward the Ohio line. There's a Westmoreland County near Pittsburgh, where many stranded families in the bituminous coal regions can thus trace their ancestry back to the Mayflower. It is truly extraordinary that such bitterness could leave so little trace of itself later. History may not be bunk, but persistent grievances are surely a menace to a peaceful existence. The events of the Pennamite Wars are widely believed to have led to the slanting of the 1787 Constitution toward the protection of individual property rights, but the wording to that effect within the Constitution is hard to locate. Somehow, like the implicit promises of the Western Reserve, ways were found to provide credible promises that it soon wouldn't matter which state you lived in. Somehow the word got to John Marshall that in actual practice, what would matter was whether an identified person could demonstrate clear title to specific land back to, or a little beyond, 1787, no matter what state the land was in. And the obscurity of the complex connection between this revolution in the law of property, and the very sad events in the Wyoming Valley suited everybody concerned. Stare decisis.

5 Blogs

Litchfield's Past

Litchfield, Connecticut is a charming little country town, a good place for successful New Yorkers to retire. But the name of the town means "a place where heretics are burned".

Litchfield, Connecticut is a charming little country town, a good place for successful New Yorkers to retire. But the name of the town means "a place where heretics are burned".

Newburgh NY: Washington Slept Here

After the battle of Yorktown the British knew they were beaten, but still stationed a menacing army in New York. Upriver at Newburgh, Washington struggled to keep his own army from deserting.

After the battle of Yorktown the British knew they were beaten, but still stationed a menacing army in New York. Upriver at Newburgh, Washington struggled to keep his own army from deserting.

Washington's Circular Letters

During the dismal days of 1782-3, Washington was confronted with the first of many examples of the American tendency to quit a war before it is completely won.

During the dismal days of 1782-3, Washington was confronted with the first of many examples of the American tendency to quit a war before it is completely won.

Dingman's Ferry, Below Port Jervis

The northeastern corner of Pennsylvania has a deep gorge for the Delaware River. Just south of it, the river narrows to a crossing at Dingman's Ferry, now occupied by Dingman's Bridge.

The northeastern corner of Pennsylvania has a deep gorge for the Delaware River. Just south of it, the river narrows to a crossing at Dingman's Ferry, now occupied by Dingman's Bridge.

Wyoming, Fair Wilkes Barre

The city of Wilkes Barre pretty well fills up the Wyoming Valley, transforming a once famous agricultural paradise into a crowded suburb.

The city of Wilkes Barre pretty well fills up the Wyoming Valley, transforming a once famous agricultural paradise into a crowded suburb.