4 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Health Reform: Children Playing With Matches

Health Reform: Changing the Insurance Model

At 18% of GDP, health care is too big to be revised in one step. We advise collecting interest on the revenue, using modified Health Savings Accounts. After that, the obvious next steps would trigger as much reform as we could handle in a decade.

Consolidated Health Reform Volume

To unjumble topics

Obamacare: Examination and Response

An appraisal of the Affordable Care Act and-- with some guesswork-- its tricky politics. Then, a way to capture major new revenue, even paying down existing Medicare debt, without raising premiums or harming quality care. Then, an offering of reforms even more basic, but more incremental. Finally, the briefest of statements about the basic premise.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

foo

bar

sna

Annotated Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE: Where Are We, And How Did We Get There?

--- Teddy Roosevelt started it, but politicians have shorter memories than historians. For practical purposes, Obamacare 2012 is an extension of the Clinton health proposal of 1991, with HMOs deleted, and computers added. It is useful to conjecture Bill Clinton's strategy, which would explain much of the present muddle. If Hillary runs, we could even see it tried for the third time.

2589 Clintoncare and Obamacare: Historical Foreword

1729 Picking Out the Raisins From the Pudding

2670 Welcome to Welfare

1714 Reforming Health Reform, New Jersey Style

2622 Children, Playing With Matches

2602 Text of AFFORDABLE CARE ACT, PL 111-148, March 23, 2010, Renamed HR 3590 https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr3590enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr3590enr.pdf

2594 The Real Obamacare, Unveiled

2672 Text of Section 1501, renamed Section 5000A: MINIMUM COVERAGE

2639 Text of Section 1251 (H.R. 3590):PRESERVATION OF RIGHT

TO MAINTAIN EXISTING COVERAGE 2673 Proposal: Coordinate Sections 1501 and 1251

2676 Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010

CHAPTER TWO: The Supreme Court Has Its Say

--- The U.S. Supreme Court had nursed certain Constitutional issues since Franklin Roosevelt's court-packing days, but it was state Attorney Generals who propelled States' Rights into the central Constitutional issue of the first few days of Obamacare. Liberal academics have long flirted with remaking the whole Constitution, and President Obama once taught Constitutional Law. While extreme Liberals nurse Constitutional revision, most Liberal politicians would prefer to split Republican voters with a third party. It is too early to predict which party would suffer.

2624 State and Federal Powers: Historical Review 2250 Obamacare's Constitutionality

2289 Roberts the Second

2592 More Work for the U.S. Supreme Court: Revisit Maricopa

2625 What Can Supreme Court(s) Do About Tort Reform?

2613 ERISA Is Thrust Into the Battle

CHAPTER THREE: Sudden Fiasco Of Electronic Insurance

----At first, it seemed a minor programming problem had temporarily inconvenienced the Electronic Insurance Exchanges. The realization soon emerged that the whole program was sloppy and untested, requiring months of repair, if not the abandonment of Obamacare. If direct marketing gets discredited, it would be a pity. The underlying idea was good and achievable. But this implementation was a disaster.

1288 Money Bags

2603 Electronic Insurance Exchanges

2626 Streamline Health Insurance?

2604 Redesigning Electronic Insurance Exchanges

2611 Phasing In A Direct Premium Payment

2615 Creative Destruction for Health Insurance Companies

CHAPTER FOUR: Small, Quick Proposals to Extend Health Savings Accounts

----Here's our alternative proposal, first devised by John McClaughry and George Ross Fisher in 1980, enacted into Law in 19xx by Bill Archer, and now numbers more clients than Obamacare. It requires publicity more than legislation, but six small technical amendments could rapidly turn an experiment into a national program. It seems to save as much as 30% of premiums, without much disturbance of the healthcare delivery system.

2637 FIRST PROPOSAL, Amending HSAs To Include Tax Sheltering

2573 SECOND PROPOSAL:Spending Accounts into Savings Accounts

2611 THIRD : Phasing In Direct Premium Payments

2584 FOURTH: Investments Pay the Bill: Obstetrics Lengthens Duration, Deductible Reserve is the Kernel.

2607 FIFTH: Having Invested, How Do You Reimburse the Providers of Care?

2630 SIXTH: Indemnity and Service Benefits

2585 Foreword: Children Playing With Matches: Investigating and Debating the Healthcare System 09 2636 2606

CHAPTER FIVE: HSAs, Backwards and Forwards

----The above describes the HSA and how it might be more useful if tweaked a little. This next chapter is a much more grandiose version, expanding the simple idea into a proposal for lifetime health insurance and describing the enormous unsuspected potential. Ninety-year projections are never accurate and require many mid-course corrections. We propose a new institution to monitor and steer it and attempt to describe what might be encountered. The power of compound interest could well pay for most of healthcare, but it is unnecessary to over-reach. Paying for a third of our costs would be accomplishment enough.

2590 Health Insurance Design.

2638 Pay As You Go

2587 Predictions of Future Healthcare Costs: Quis Custodiat Ipsos Custodes?

2628 Average Lifetime Medicare Balance Sheet

2627 Shifting Money Backward in Time: Managing the Transition

2593 Economics of Chronic Disease and Catastrophic Illness

2634 Comments on Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG)

2635 Admonitions: Using the Transition to Lifetime Health Insurance as an Inflation Restraint

2473 An Unending Capacity to Generate New Problems

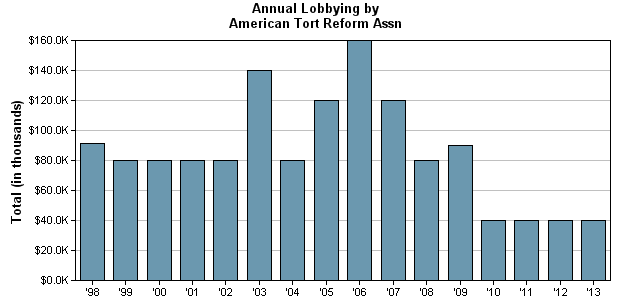

1734 Healthcare Reform for Lobbyists

2485 Cost Shifting, Reconsidered

2571 Proposed: A Republican and/or Conservative Healthcare Solution

2610

CHAPTER SIX; Reforms More Basic Than Obamacare

----Obamacare is just coverage extension by subsidies. The biggest flaws in our payment system are fifty years old and are the cause of most of the delivery system flaws. Meanwhile, Science is reducing disease costs by reducing disease, for all income brackets. By switching "medical" care into "health" care we keep authorizing new carpetbaggers to bill the insurance. Physicians received 20% of payments in 1980; now it is 7%, half of which is spent on overhead. Nevertheless, compound interest income could reduce costs greatly without changing healthcare. Lifetime insurance (above) could pay for about a third of future costs; direct cost efficiencies could probably save another third, leaving a third to be paid in cash. But don't make it entirely free, unless you want to make it entirely ruined.

2633 Stepping out of the Obamacare Frame

1730 What Obamacare Should Say But Doesn't

2616 The Coonskin Hat

2404 "They Don't Make That, Anymore"

2564 Last Cow in Philadelphia

2112 Paying for Assisted Living

1431 July 4, 1776: Patients in the Pennsylvania Hospital on Independence Day

1733 Obamacare And Its Repair, Executive Summary

2453 What's The Matter With a Conservative Answer?

Clintoncare and Obamacare: Historical Foreword

Twenty years after their Health Proposal was withdrawn from Congress in 1994, the Clintons can thank their lucky stars they withdrew it. One thing is clear; the Obama health insurance mandate followed a surprisingly similar early trajectory, beginning with a protracted flurry of publicity and astonishing promises that never materialized. But the Clinton plan was quietly sabotaged without much explanation before it got this far, nowadays almost pretending the subject had never been mentioned. In both cases, a President had proposed an adventure which the American public didn't want to undertake, but only one of them backed off.

As of this writing, the Affordable Care Act is a law actually in force, even though the party in opposition is determined to eliminate it as soon as it regains control, whereas the other party acts determined to conceal its real content for as long as it can. From its behavior, the Obama administration seems willing to provoke a Supreme Court contest, rather than conciliate a retreat. It seems unlikely the public will abandon its Constitution in order to preserve a health insurance plan, particularly when the President is running out of time to make it successful. Even if he could rescue a failing program, both foreign affairs and the financial crisis seem more urgently in need of his time and attention. We like to see signs of competitiveness in our President, but accomplishing what the Clintons, Harry Truman, and Theodore Roosevelt could not accomplish, does not strike most people as sufficiently useful. Some cynics feel his real strategy amounts to what they call in football, "playing for the breaks". Wait until your opponent makes a mistake. This book is written in the hope that both parties are as confused as they seem, remaining open to new ideas rather than rigidly following a playbook. Somewhere along a newer path, we might reset our compass to eliminating the disease as the route to reducing disease costs, instead of tinkering with insurance while we watch costs go up. For thousands of years, the elimination of disease has been an impossible dream. Not any more.

Let's begin with brief mentions of the Clinton Plan because it apparently set the original pattern. At its center was a national blueprint for Managed Care, called HMO (Health Management Organizations.) Leaders of large business, already intrigued by the notion of constraining national healthcare costs by clever management of the health insurance they provided their employees, had originally played along with the Clinton administration. As did their reluctant agents, the large-group health insurance companies. Together, Big Business and Big Insurance had previously taken a step away from state-regulated Blue Cross systems toward a nationally regulated ERISA system, in order to cross state lines more comfortably. Insurers were also having problems with their turf: the hospitals and the unions. Originally, hospitals had once, ninety years ago, joined with business to form locally based health insurance, often with small business and charitable foundations in the lead. However, insurance and the federal government eventually dominated (but underfunded) the health payment scene, with everybody unrealistically expecting business to pick up escalating costs that business could no longer control. And while business had to get along with its unions, it was disquieting to business leaders to find so much union influence infiltrating nonprofit insurance leadership. Hence they were uneasy to find so much interest in unionizing hospitals, so much involvement in partisan politics. Furthermore, the old actors were uneasy with the new actors looking for control, hence the subtle change of "medical care" into "health care", as a way of wig-wagging new allegiances. Finding a hospital-centered model increasingly worrisome, leaders of business had been briefly intrigued by the concept of shifting the control center to HMOs, which seemed to act more like businesses, and thus might be a better buffer with the feds. One of the main problems with dragging out major reforms over decades is that old alliances grow stale, old promises become invalid when new combatants join the battle. Gradually a number of disillusioned businesses quietly withdrew their support from the original Clinton proposal as they learned more of its new realities. In the view of the business and insurance world, national politics of some sort would soon cripple a complex HMO idea that needs good management, most of all. If the rest of the "health" world didn't feel it retained any debts to the pioneers of pre-paid health insurance, well, big business had other things to do.

Congressmen understood the general direction of this mixed message and, at least as defined by "HMO", the floor leaders of the Clinton Plan found they no longer had the votes to pass the health bill. The Clinton Administration yielded and let Big Business go it's a way. Businesses then undertook the HMO project themselves, only to get burnt fingers when they discovered the HMO concept, without a physician or patient enthusiasm, was doomed to failure no matter who co-sponsored it. The public, even their own employees, resented the regimentation of HMO systems, except perhaps for union political machines on the Atlantic and Pacific coasts. To the interior of the country, the enduring California image of HMOs was not an asset.

Unfortunately, Democrats also escaped learning from Clinton cares flaws by failing to pass it. Most importantly, liberal leaders never quite grasped the message the public was sending back to them: The public's healthcare and its governance belong to us -- not to our employers, nor to our elected politicians. If some group wants to pay our bills for us, Americans would pocket the money. But ownership, transferring real ownership of healthcare to the public sector, had never been considered a serious option by a very large segment of the population. Local control was the main reason healthcare had lagged behind the rest of the economy in the shift from state to federal regulation. The debate was still about healthcare, but it might easily switch to a debate about the Constitution, which the Constitution was not likely to lose.

Powers not granted to the federal government...., are reserved to the States or the people.

|

| Tenth Amendment: What Part Don't You Understand? |

The Tenth Amendment could suddenly be recited by people more characteristically excited by professional football. If there was to be the talk of amending the Constitution, perhaps it was the part about Congress making its own rules, which needed changing. State governments, ordinarily regarded as the weakest part of our political system, became a White Hope. Congress itself had become more polarized than at any time in the preceding fifty years. Not to mention the fragile condition of foreign affairs or the bewildering tangles of international monetary policy, it looked to be high time to ditch this health thing of Obama's.

Accordingly, this book roused itself into print. Because, no matter what the final fate of Obamacare, it isn't really healthcare reform, it isn't even serious health insurance reform. One main reason it deserves to raise so much concern is the way polarization is spreading into other basic institutions. A real danger is we may spend so much money, and devote so much of our limited attention span to Obamacare, that we never will get around to some basic reform of health care. No matter how else it may be described, this book is about real reform of health care, including absolutely indisputable reform of the insurance part. But because of the political timetable, I came to feel that there was only half the time I needed to be complete. I cut off the bibliography, had to be satisfied with a mechanical index, and then with great regret, cut out at least half of the "inside baseball" describing the details of healthcare reforms -- as distinguished from Health Reform. Unless this book provokes less controversy than I anticipate, there won't be time to do much but answer it.

George Ross Fisher, MD

PhiladelphiaPicking Out the Raisins From the Pudding

There appears no better blueprint for the 1993 healthcare reform legislation (commonly called "Clintoncare") than Jacob Hacker's 1999 book The Road to Nowhere. If President Obama did not use this same roadmap for the "Obamacare" health program, it still remains quite a good description of what he did do. His following this earlier playbook would plausibly explain much that is otherwise mysterious.

The Hacker book was originally an academic thesis written several years after the (Hillary) Clinton Health Plan experienced ignominious disappearance in the halls of Congress. By then, the Clinton episode of 1993-94 was quiet and forgotten, so participants probably felt it was safe to describe big-shot politics to a college kid writing a thesis. The resulting book was easy to follow, had a ring of authenticity, and advanced the author's career. Advanced it so much the same Jacob Hacker later became visible near Democratic policy circles, even seemingly advising political deals, even though strangely quiet, lately. The similarities between the Obama initiative and Clinton's earlier strategy in Hacker's book, are striking. However, a judgment must be suspended whether to frame it as a cautionary tale, or a guidebook. In fact, the possibility that Mrs. Clinton plans to use the blueprint a third time produces a strange fascination among even her enemies.

1. Pad anything into Senate and House bills. 2. Send the padded bills to a conference committee. 3. Delete all but your own ideas. 4. Ram it through.

|

| The Clinton Strategy |

Boiling it down, the (Bill) Clinton strategy was to confront a House-Senate conference committee with a vast pile of often conflicting proposals, sent to a conference committee for a proposal to reconcile inconsistencies. In fact, a coherent proposal could not emerge from a Clinton bill, until the President sent his list of proposed deletions to that conference committee. After trimming to its essentials, the conference committee reconciliation would then return for House and Senate approval, probably against some holiday deadline to quash objections. The process would resemble picking out the raisins from a pudding, combined with the nuisance of buying off a few soreheads, except for one thing. The Executive Branch deftly acquires more power over legislation than the Founding Fathers ever contemplated. Michelangelo's remark, that carving statues is just a matter of throwing away what you don't want, is bitterly appropriate here, especially from the viewpoint of those who thought they were elected to write laws, not follow orders. On the other hand, this approach favors a party with safe seats from concentrated urban districts, tending to be more compliant to party bosses .

In a technical sense, this process is more equivalent to a line-item veto. (A line-item veto, by the way, is something Congress repeatedly refuses to grant). It's hard to oppose an omnibus bill until its outline appears, and this Michelangelo process tends to obscure the tone and central theme of legislation until the last possible moment. From the point of Conference Committee forward, passing it back for ratification becomes a matter of rushing it ahead of criticism, and indirectly lessens the power of public opinion. Nor would be the first time a few little extra zingers, never discussed by either the House or the Senate, got slipped into a conference bill, which is typically several hundred pages in length. And the timing for the release of the omnibus legislation could be selected, quite likely the day before Thanksgiving or Christmas when newsmedia was away from work. Or else after a long series of preparatory news events, building public expectations before a spectacular revelation day. But it is a mistake to focus on the press as being hoodwinked. It is the other Congressmen, the ones who ultimately don't get what they were promised.

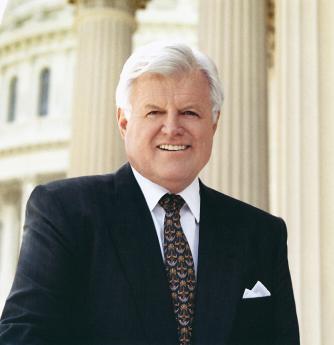

And finally, unexpected events can intervene, as Scott Brown's Senatorial election did in this Obamacare instance. A clever scheme got suspended in mid-air by the death of Senator Edward Kennedy. The bill had been passed by the Senate, but not the House. The House bill was so different it would require reconciliation with what by then would be a different composition of the Senate, and therefore could not pass the Senate a second time. So, a bill identical to the Senate version was jammed through the Democrat-dominated House, no amendments permitted, no conference committee needed to reconcile two differing bills. Unfortunately, the original plan was to include some provisions purely for the purpose of obtaining a Senate vote or two. The original plan was to be that "deficiencies" would be remedied by some raisins tucked in the House bill, which of course never came up for a vote. Thus the resulting legislation is the pure Senate version (with all its undesirable features remaining) and we may never know what was in the unpassed House bill that might have repaired unspecified Senate flaws. After all, this trickiness, does anyone wonder why so many Congressmen are dissatisfied with the result?

Looking back, it is hard to prove how much of the Clintons' original strategy was adopted by Obama, or how much influence Hacker and Hacker's book had, until someone on the inside writes another book and tells us about it. But the congressional strategy of the Obama Health Plan proposals does sound very similar to what we should probably give the name of "The Arkansas Strategy". That strategy would certainly explain a great deal of what happened; it scarcely matters how much the similarities were accidental and how much they were following the same playbook. Except, of course, if some of the participants decide to run for office in the near future, and try to do it all, a third time.

|

| Senator Edward Kennedy |

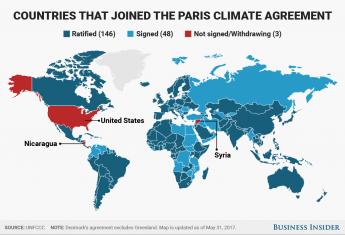

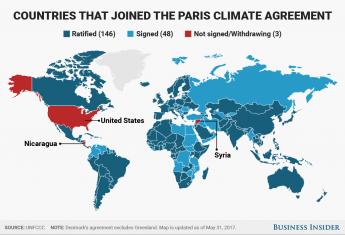

Senator Edward Kennedy's impending death, Senator Byrd's incapacity, and the contentiousness of the health reform topic always made it uncertain a 59-vote Democratic Senate leadership could assemble 60 filibuster-proof votes in favor of any healthcare proposal; one betrayal and you've lost. The Democratic Massachusetts legislature took away the right for Republican Governor Romney to fill a vacant Senate seat and restored it for a subsequent Democrat governor. In circumstances like this, every single Democratic senator can hold a proposal for ransom, while every single Republican senator will unite in opposition. When the majority shifts Republican, which could be rather soon, the roles will be reversed in an almost certain effort to repeal whatever passed. The public was left wondering whether healthcare legislation was worth hampering our interests in Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Syria, immigration reform and the national debt. The Democratic Congress had to worry it was not worth the political damage from hammering it through. They might also worry that the Supreme Court might be drawn in, expressing some unwelcome Constitutional viewpoints. It's really hard to know what to wish for.

|

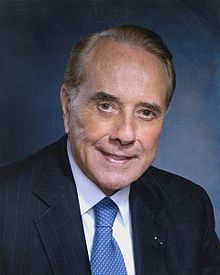

| Bob Dole |

Along the way, former Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole appeared on television and revealed a different insight about Senate behavior. Senator Baucus told the press that something called a Public Option could not pass the Senate, so he was not including it in his proposal. Extreme left-wing members of the Democratic party said they would "take a walk" if the Public Option was dropped. But although it was dropped, it was included in the House version and might thus have been restored in the conference committee. This "Montana" maneuver removed Public Option from Senate debate, still hoping to preserve those 60 votes. Under the circumstances, it isn't even necessary to remember what the Public Option was, but essentially, Public Option was a proposal for the Government to go into the health insurance business itself, in order to put overwhelming pressure on the insurance industry. In 1965 this was impossible, in 1992 it was unprepared for, in 2009 it was merely chaotic.

It is widely rumored the Public Option was a punishment for the reluctance of the health insurance industry to cooperate more fully with the President, or at least a threat of what could happen if they didn't soon cooperate. Indeed, you have to question what the attitude of the Insurance Industry really was, in a proposal which would greatly diminish their control of insurance. Karin Ingaglio, the chief lobbyist for private health insurance companies, admitted to the National Journal that her group had contributed millions of dollars to the Tea Party, leaving it unclear whether she was playing both sides of the street, or else hoping to defeat the Republicans with a third-party, Tea Party, distraction. Bob Dole was a gracious, gentle old man, musing about what might be going on. You don't suppose, he mused, the Public Option might be nothing more than a red flag in front of a bull, to be surrendered with a great show of disappointment. But actually, just a feint creating an uproar, to divert attention from the real zingers in the rest of the bill, which can then pass through unnoticed. But, no, Bob Dole didn't really imagine such a thing. It was just a wild thought he happened to have.

Political observers agree that presently rancorous Congressional partisanship is the worst in a century, and it is not shared by the public. Just about everyone in the political class sees gerrymandering as the main cause. Changes in the ways voter redistricting is conducted, some say the use of computers, has made gerrymandering much more effective. When numerous safe seats arise in this way, it is only a matter of time before the Legislative seats are filled with heedless, reckless partisans, beholden to no one. But it is just as bad, if the seats are filled with party hacks, forever obedient to the unelected rulers of urban political machines (leaders of party machines seldom run for office.) The seniority system takes over, and safe-seat partisans get control over Congressional committees and party discipline. This happens to both parties because incumbents from both sides unite to achieve it. But urban districts are harder to split into party lines, so states containing large cities tend to present a permanent disadvantage in numbers for Democrats, although uniform composition makes for much greater partisanship. Contestants for the dwindling number of uncertain districts are thus forced to act more cautiously, thus tending to seem more competent by the press and the public. But even if elected, they are powerless in the face of the more unrestrained partisans who control internal power plays, and who also tend to be long-term incumbents from safe seats. As a consequence, moderates are more likely to be singled out for sacrifice in the following election.

Scientific gerrymandering has certainly coarsened and hardened the political atmosphere, considerably reducing public control of its representatives. It should also be noted that Senate seats cannot be gerrymandered, but state legislative seats definitely can be, leading to a coalition between state legislators who are almost always party hacks, and U.S. Representatives, who are increasingly so. It is said that in New Jersey and Florida, it is possible to predict the next ten years of politics with precision if you only know how the gerrymandering was arranged. The Senate could probably devise a Constitutional amendment to fix this problem, with no chance of passing the House or getting ratified by the States. Therefore, the present main hope for representative government lies in the national party leadership of some party, intervening into the party nominations for safe seats. Even that, would take extraordinary luck and agility. It remains to be pointed out that 2020 is the upcoming year for a census, 2022 for redistricting.

Welcome to Welfare

Percent of Their Hospital Cost Reimbursed: Medicaid 70%, Medicare 106%, Private Insurance 150%, Uninsured 400% (?)

|

| Hospital Cost Shifting |

There's lots more; in politics there always is. The Pew Foundation, which now includes public opinion polling in its tasks, has pointed out 80% of the public does not share the polarization now so blatantly agitating the political class. Hence, some commentators have questioned the prevailing opinion of gerrymandering as the main source of it. These observers point to a worldwide decline in party affiliation; "independence" of party affiliation is claimed by nearly half of American voters when asked. Perhaps we have things backward, and gerrymandering is merely one effort, along with growing dependence on financial contributions by wealthy donors, to rescue party power. Television (and especially the Internet) prompts the voter to hang back before making decisions, hoping to decide something without pressure from party leaders. The growing tendency to vote straight party ballots is not taken by a few commentators as evidence of true voter wishes, but rather as evidence of the futility of resisting a two-party system. Some sophisticated observers feel straight ballots result from plurality ("first past the post") counting of votes, but this (unfortunate) trend seems more likely to be stimulated by (too) early voting by mail.

Since a two-party system favors moderate candidates over extremist ones, it may not be a bad system, but rather a good system adjusting to circumstances. A hidden cause of the present crisis in health care financing comes from the Medicaid programs, run by the states, but mostly (and inadequately) financed by federal taxes. A two-party system disciplines the nominating process by raising doubts about the ability of extremists to win the general election. Consequently, the final two candidates are often so similar the chance of a loser bolting the process, becomes small. In a proportional voting process, splinter parties cannot be silenced in the primaries, because political deals take place after the election when the public has become irrelevant to the voting outcome. Threats of public disaffection are therefore disregarded. This hidden feature went unrecognized at the Constitutional Convention, as indeed was the whole party apparatus. But it has to be counted as one of our greatest strengths, placing a much higher value on unity than dogma. If you follow this reasoning, you would have to conclude the present level of divisiveness will not persist. Because each generation has to learn its own lessons, it may recur, but it will not persist.

Nursing homes were not originally included in the 1965 legislation, but most states receive strong pressure to pay for elderly indigents in nursing homes, stranded by running out of savings. Perhaps it would be a good thing to include nursing home coverage in a reform bill, but nursing homes bear too much resemblance to work-houses to generate much demand to be in one. In variable degree, the circumvention has grown up of paying for nursing homes with money intended for hospitals but necessarily underpaying the hospitals. The hospitals make up the deficit by overcharging for outpatient services, as everybody will recognize who has been charged for the same service, both as an inpatient and an outpatient. By prevailing estimates, the Medicaid programs only pay hospitals about 70% of their actual costs. Hospitals escape insolvency to a minor degree by raising reimbursement demands on Medicare (to about 106% of costs) and more appreciably through private insurance (to something approaching 150% of costs). Teaching hospitals have some opportunity to raid funds intended for indirect research overhead, for resident stipends, and for disproportionate shares of an indigent, "self-pay" patients. Various accounting tricks account for the rest. For example, the transfer of schools of nursing from hospitals to universities has emboldened universities to seek the equivalent of traditional hospital reimbursement schemes, merely and mostly triggering new arenas for dispute, because the hospitals had hoped to profit from the transfer. Since Medicare somewhat overpays hospitals for its own patients, in recognition of the underpayment by states for indigents, current jargon blames the "government programs" for underfunding hospitals. A better summary of the situation is: Medicaid under-reimbursement is the largest source of hospital financing problems, but other problems are less resistant to change. That's pretty significant, in view of the Obamacare plan to put millions of uninsured into Medicaid, some of whom never asked to be insured at all, and most of whom have no previous experience with "welfare", so they need to start reading some books by Charles Dickens.

|

| Governor Christie of New Jersey |

The outcome of all this is nursing homes are in effect supported by Blue Cross and other private insurers of younger people, raising premiums to employer groups and individuals by something estimated like $900-1500 a year per subscriber. That's because Medicare is busy subsidizing Medicaid's hospital patients, the main source of hospital deficits. Because this juggling lacks straight-forwardness, results are inefficient; only about 42% of hospitals actually break even. As might be expected, knowledgeable employer Human Resources departments and hospital administrations know about and object to this system. They are cooperating with Obamacare more than might be otherwise expected, probably in the hope this cost-shifting can be adjusted more in their favor when it is less in the public eye. Mandating all employers to participate would, of course, increase the base of people sharing this exaction, but would ultimately link corporation treasuries to government deficits. The dream of the service unions would be to use this excuse to mandate the unionization of hospital employees. Governor Christie of New Jersey quickly saw a way to split the Union movement into public and private compartments through this. "Every time they get a raise, you get a tax increase," he told the unions of the private sector.

The participation of physicians in the Obamacare effort is riven by their own politics. For surgeons, the premiums for Malpractice insurance can sometimes run to $200,000 a year. An appalling proportion of obstetricians have been sued by their patients, to the point where women have no doctor to deliver their babies in certain parts of the country. For doctors in this high-risk category, relief from the plaintiff lawyers is the most pressing of all problems. On the other hand, many physician specialties have almost no malpractice risk and are much more exercised about the SGR reimbursement freeze, which has been in effect since the administration of Lyndon Johnson and has been severely undermined by inflation ever since then. With physician ranks divided by two different priorities, the way is open to promise both and reward neither.

The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.

|

| Tenth Amendment |

Urban-rural differences remain important in health care. Senators Baucus, Grassley and Snowe come from sparsely settled states. Former Senator Daschle is from South Dakota; there are perhaps twenty states potentially in this category. With a sparse population, it is difficult to develop sufficient insurance business for the law of large numbers to establish actuarial safety; these states need to combine into regional areas to reduce the competitive size of their loss reserves. On the other hand, populous states like New York, California, etc. are often adamantly opposed to regional groupings, for opposite reasons. These population disparities create differing attitudes about modifying the 1945 McCarran Ferguson Act, which limits federal insurance regulation and enables state regulation, thereby making it difficult for small states to agree to interstate health insurance sales and portability. The fact that large employers have already achieved this freedom through ERISA also makes them unwilling to see the problem or waste political capital achieving it for others. And thereby diminishes the power of low-population states to resist national healthcare insurance, which is their natural position.

And finally, Obamacare raises some questions about judicial remedies. Certain Op-Ed commentators have raised a question of the constitutionality of federal mandates or pre-emptions of state laws, depending on how they are phrased. The U.S. Constitution was only narrowly ratified in 1789, in large part because the states were fearful of the federal government getting bigger and more powerful than necessary. In response to this strong feeling, the Tenth Amendment reinforces in no ambiguous words, that anything not specifically assigned to the national government is to be in the province of the state or local governments. If ever there was original intent, it was that one.

REFERENCES

| Never Enough: America's Limitless Welfare State | amazon |

Reforming Health Reform, New Jersey Style

|

| Congressman Robert Andrews |

A single e-mail to constituents, and no other communication visible to the general public, announced a town hall meeting with our Congressman, Bob Andrews, on the campus of Rowan University, from 6 to 8 PM, August 24, 2009. The subject was to be Health Care Reform Legislation. On arrival, it was hard to find the auditorium in the square mile of new college campus, and only a small sign entitled "Event" indicated the place to park. Lots of cars.

By counting seats in a row and multiplying by the number of rows, the University Auditorium held 3000 people, but at 6 PM it was difficult to find a vacant seat. The doors were almost blocked by two lines of people standing to speak at microphones in the center of the hall, snaking all the way out past the television cameras and then out the door. These people were strangely silent, preoccupied but not rude, apparently rehearsing their speeches. In the lobby outside the doors, several workers were distributing posters showing "Thank You!", checking people off on lists of some sort. Many of those who got posters were wearing red T-shirts emblazoned with something or other.

|

| Rowan University |

When I finally got a seat inside, it was behind a whole row of such T-shirted poster-holders, mostly but not entirely of the black race. The Congressman was giving a little speech to the effect that he was one of the committee members who wrote the bill, so of course, he had to support it. Strange, that as a member of Commerce and Labor he was working on a bill which traditionally is the province of the Subcommittee on Health, of the Ways and Means Committee. In any event, that gave him the ability to explain some of the languages which were a little too hard to understand. Several in the audience shouted out something unintelligible at that point, but mostly the audience sat in silence, waiting for the questions. He soon opened it up for questions, because he wanted to know what his constituents were thinking.

Although a few inevitably wandered off the point, questioners were confident, moderately deferential, remarkably effective. No matter how it was stated, and no matter how it began ("I have always voted for you, Congressman"), they were at the microphone to run a sword into him. To some extent, posting the entire bill on the Internet had changed politics. One old man, reading from his papers, said that page 343 says, etc; to which the harassed Congressmen blurted out, "That isn't true!" But the old man held his ground, "Oh, yes, and what else isn't true, that's written in the bill?"

Our congressman represents a working-class district, as clearly illustrated by his previously running for Congress without opposition. In searching for the reason this solidly Democrat audience was so antagonized, one gathers they generally have Unionized health benefits and feel threatened that ensuring the "illegals" will be paid for by impairing their own insurance. Somehow they feel that anyone who denies it is lying to them. ("It isn't what's in the bill, it's what will be in the bill ten years from now.") Except for college professors, Union members have the most luxurious health insurance coverage in America and are accustomed to boasting of it. Somehow, this privileged position drowns out their envy of rich people. When told that only the top x% of the country would have its taxes raised, one man bore right in on the Congressman. "You never heard anyone asking a poor man to give him a job". (Yeah, right, right on, Yeah.)

Although the people in red shirts holding posters put up a fight for fifteen minutes or so, they soon subsided out of recognition of who "owned" the room, and the remaining three hours of "questions" were almost uniformly negative. After an hour, the television cameras left the room, and at that signal, the people in front of me wearing red shirts also left. After a succession of speakers praised physicians somewhat excessively, a couple of physicians got up and made a poor showing at the microphone. One of them, a fat woman, had the poor judgment to tell these folks that many diseases like diabetes were self-inflicted, but was to hear back that it would help if our President would himself stop smoking and leave the rest of us to mind our own business. Two women who proclaimed themselves single mothers were no better treated..

At 9:30, a meeting scheduled to end at 8 PM still had a thousand people in the audience, and fifty at the microphones. But I had enough. They made their point. All that remains is to see how fairly the television editors extract significant clips and to find out how the rest of the nation feels.

LATER FOOTNOTE: As matters turned out a few months later, this national legislation had more of a local New Jersey effect than the audience could have guessed. Mandating health insurance for 30 million uninsureds, Obamacare accomplished it for 15 million of them by forcing them into the state Medicaid program, which is widely acknowledged to be the worst program in American medicine, because it usually is the most under-funded. New Jersey residents are firmly opposed to anything which raised their already high local taxes and will focus intently on the attempt in the coming lame-duck session of Congress (November 2010) which intends to transfer federal money to states to pay for Medicaid, and which is given only the narrowest chance of success. Republican Governor Christie deftly split the industrial unions from the public sector unions with the remark, "Every time they get a raise, you get a tax increase." It was hard to answer.

Children, Playing With Matches

|

And now, after the President has signed a bill into law to be effective January 1, 2014, we have mandatory health insurance. Really? The word 'mandatory' is not easily found in a search engine search of the 450 sections of the Affordable Care Act, except for mandatory coding and reporting requirements, and perhaps some oblique references to what might possibly be required of newly mandated insurance enrollees, in case anyone is mandated. The operative term used in the statute to imply universal coverage is "Required minimum coverage", mostly deferred employer group plans for at least a year, particularly for those with more than 100 (formerly 50) full-time employees.

It is unclear what the Supreme Court decision limiting penalties to a small tax will do to this group, who temporarily (?) make up the largest proportion of people affected. They are also affected by more severe penalties for noncompliance, a dubious application of equal justice. What is mandated right now is that everyone who does not belong to a group plan, and who is not specifically excluded, must pay a tax if not insured. Shortly after the law was enacted, the U.S. Supreme Court specified the tax must be small, otherwise, it would be coercive. Two opposite suppositions are possible: by the time the large-employer deferment expires, either the burdensome penalties will be reduced, or else the present uproar will seem trivial by comparison with what will come next year. Seen from a distance, this law looks as though it was written with large employer groups in mind, and everything else was patchwork. If we discover later the patchwork is the whole system, the Affordable Care Act then assumes quite a different character from universal coverage, and probably should be remanded.

Let us accept the premise that this law was mostly intended to provide for those who have unusual difficulty obtaining or paying for health insurance. There were thought to be 30 million of them, probably more during an economic recession. What is the most cost-effective way to pay for ensuring this group? For practical purposes, most of the uninsured fall into three groups: criminals, mentally disordered, and illegal immigrants. Instead of disrupting the entire medical payment system, let us design three new programs, specifically aimed at the special problems of these three groups. They might not cover quite so many affected people, but tailor-made programs would probably do so more appropriately, get the job done more quickly (remember how long this process has already dragged on), and plausibly less expensively. By using block grants to the states, we might in time have the advantage of finding the best of several variations emerge.

Block grants may not be feasible in some of these areas, mostly because of politics, but for other reasons, too. In some ways, the prison population might prove to be the most difficult to make uniform, and while uniformity is not the highest priority, it has some value. Some regions tend to regard criminals as sick people who need treatment, while other regions regard criminals as outlaws who need punishment. Either way, costs may vary considerably, and frugal states do not enjoy subsidizing extravagant ones. In all states, criminal costs are unwelcome, so some states treat incarceration as a profit center, and first-class health care for convicted criminals is definitely not a goal. A wise Congressman avoids issues like this one, and block grants are probably the best solution. Obamacare excludes these people, entirely, even though there are 7 million of them.

A better case can be made for a health program for the 11 million illegal immigrants, but it comes down to much the same issue of local social attitudes affecting the politics, plus the fear that generous treatment will attract more immigration. A much better case can, therefore, be made for uniformity of federal subsidy, and by paying the subsidy directly to the healthcare provider, avoiding much of the political problems. Policing the borders is a national problem, and therefore the illegal immigrant health costs are a problem the federal government should absorb.

Mentally disordered people fall into several subgroups, but here the Federal Government is more fairly accused of making the problem worse, through closing the mental inpatient hospitals faster than drug therapy made it really feasible. Experience has shown that local treatment of mental disorder tends to be more generous and humane than remotely controlled reimbursement systems. When Congress became incensed at what seemed like exploitation of the DRG system, an overreaction was too harsh and business-like for a population that is by definition not completely responsible. The situation seems to call for a block grant program with a few incentives for state compliance with a limited set of standards.

In summary, if we look at the three main sources of clients among the uninsured, none of them seems suited for a national revision of care for the rest of the population. In fact, the generalization seems appropriate that they are highly unsuitable for a uniform national insurance program, pointing to higher costs and worse care if you approach them that way.

In fact, the political downside is worse. If you set about to do things without explaining why they aren't bizarre, people will assume you have some other motive than the one you offer.

Some regions of the country People in jail (there are about 7 million of them) are specifically excluded, and illegal aliens (at least 11 million) are indirectly excluded. Added to these two groups are those who will never be self-supporting because of developmental or acquired mental disorders. These three groups alone almost total of the forty million uninsured persons who were originally slated to be the main problem to be solved. It seems likely the specific and unique health financing problems of these three groups could have been better and less expensively addressed by devising three special programs for their specific problems (incarceration, non-citizenship, and mental defectiveness). In addition, 2 million members of (sic) Indian tribes are also excluded, and there are estimated to be 5 million persons potentially eligible for tribal membership. To stretch general health insurance to fit the unique difficulties of these admittedly difficult problem cases is far less likely to be satisfactory than directly aiming at them. And thus the trillion dollars extra cost estimate for the Affordable Care Act could likely have been better spent.

Just to take one of the three hard nuts, let's look at medical care for prisoners in custody. I have physician friends who are involved in prison medicine, and they are proud of the way they have suppressed medical costs to prisoners. Much of the problem revolves around the tendency to locate prisons in remote rural areas, where the quality of medical care is marginal, to begin with. But central to the issue is the determination of states to keep prison medicine inexpensive, no matter how anxious the rest of the nation is to upgrade the care. So state governments are not about to surrender control of the system to agencies which want to spend money. This isn't rocket science; the solution to this problem is more money, and not the kind of money that resembles Lucy holding the football until the last moment, then pulling it away. Prisons are tough places, with tough people in charge, and lots and lots of drug smuggling going on. Please let me know if you think there is anything in the Affordable Care Act which addresses these issues.

In fact, the briefest discussion of the three largest groups alone calls into question the wisdom of devising any program, insurance or otherwise, to apply to 100% of the population. Your author does not hate insurance, for healthcare or any other purpose. But few approaches will solve any problem for three hundred million people, for every day of their lives. We should thank the insurance industry for doing a good job for 90% of the public, and move on to other solutions for the last 10%. But in thanking them, they will pardon us for asking whether many of us would pay someone 10% to pay our bills for us, not counting the additional $10 billion income tax deduction we offer every year, to induce people and their employers to pay their bills. Why would anyone think insurance is cheap?

The most depressing feature of this issue is that it is likely to be repeated. If you believe as I do that the clever parliamentary tactics employed in its hybrid passage must have resulted in omitting some important features from the House Bill, and must have included many unwanted features in the Senate Bill which survived, then much more is to be uncovered, later. Unfortunately, a reading of the 450 surviving sections leaves the reader baffled as to which sections are central to the proposal, and which ones were included merely for window-dressing. At one time, the Administration may have thought this gave them a free hand to trade off superfluous baggage, but with the full text easily accessible to everyone, everyone can read it and continue to be annoyed by how it got there.

To aid in this process, we next print the table of contents, with section numbers. When the section number has been located, the full text of the statute can be displayed on any home computer, by entering the section number into the otherwise overwhelming text of the full Act. When risk corridors and other mysteries come up for discussion, it will generally be found that the matter reduces itself to a few sentences.

Text of AFFORDABLE CARE ACT, PL 111-148, March 23, 2010, Renamed HR 3590

The Real Obamacare, Unveiled

|

| Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi |

Even loyal Congressional Democrats demanded more explanation for passing Obamacare than they received. Democratic Speaker Nancy Pelosi implausibly explained, "We have to pass the bill in order to see what's in it." That didn't help very much.

An unexpected bungle of computerized insurance exchanges that didn't work, would soon confront Obamacare supporters with explaining things to a hostile public, instead of to a merely curious one. Instead of providing better insurance to thirty million people, many of whom did not have insurance, the Administration had to cope with the possibility of uselessly depriving several hundred million people of insurance that did satisfy them. And to do so past the deadline for renewal of their old programs, made several million suddenly anxious that newer products must somehow be worse, not better.

It was expedient politics to add new but more expensive mandatory features. But since many people could already choose a more expensive policy if they craved more features, the practical effect was usually to make insurance more expensive without providing anything new. Here, it also had the unwelcome appearance of extra cost paying for somebody else's subsidy. In any event, health insurance was certainly not cheaper.

Employees of big business were evidently particularly dissatisfied, so their arrangement will be announced later, probably after the elections. Two years after passage, the Affordable Care Act was still a work in progress, but it was hard to call it a victory.

|

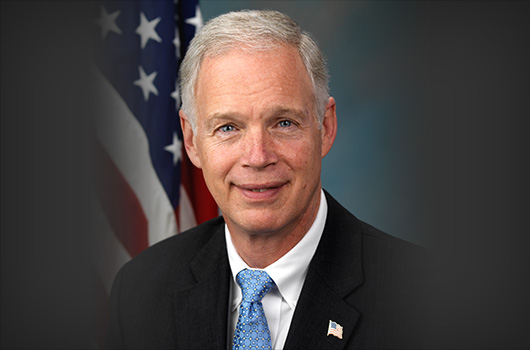

| Senator Ron Johnson |

Worse to come wasn't just an idle possibility. Millions of complacent people then received letters of cancellation (from their old, private insurance companies) in spite of specific provision in the law (section 1251) and repeated assurances from the President that this would never happen. Retired people on Medicare had mostly ignored Obamacare, which didn't apply to them. But any cancellation of existing benefits quickly revived anxiety that the real intention might be to pay for poor people (Obama's "base") with cuts in Medicare, which everyone over 65 had grown accustomed to receiving. A large new group was suddenly asking awkward questions.

Government workers and Congressmen definitely had to accept the new plans, probably to demonstrate shared sacrifice. That led Senator Johnson from Wisconsin to sue for damages because his constituency might think he really wanted to have it, in spite of nominal opposition. Big business received more extensions to its one-year postponement, which increasingly looked like a repeat of the 1994 Clintoncare experience where they had walked out, in a somewhat more obvious way. Small business was immediately refused similar relief, introducing concern about political favoritism, and conspiracies yet to be revealed. One of them surfaced a few months later, when "postponements" for employers with 50-100 employees were announced, effectively adding them to the definition of big business. Once more, there had been no such proposal in the enabling legislation. A majority of state governments refused to establish insurance exchanges, and an appreciable number of governors even refused to expand their Medicaid programs with Federal money. It could be argued that bribes that weren't permanent were essentially no different than direct coercion of states by the Federal Government, but were just a different method of revoking states rights under the Constitution.

Since it might be many years before deaths and retirements made it possible for insider biographies to explain everybody's true motive, the public applied the ancient Roman test of Cui bono? ("Who comes away from it, better off?") Everyone half expected the Obama base to be rewarded, and the Republican base to pay for it; but rewarding five percent at the expense of ninety-five percent, went beyond any election mandate, or even any tradition of the spoils system. Better medical care at cheaper prices always sounded over-optimistic. But worse care at a higher price now began to seem like the real outcome. Who comes away from that, better off?

|

| Republican Senator Scott Brown |

If a copy can be found, it certainly might be tempting to review the final original House bill and compare what was in it with the ultimate product (which was really just the Senate bill). But at that particular moment, there had been a Democratic majority, and that majority declared its preference for the Senate version. That is what the President signed. He then apparently hoped to solve its deficiencies by Executive Branch regulation, which might well lead to Constitutional lawsuit based on the "Vesting Clause" in Article 1 of the Constitution that, All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives. . When he subsequently did issue several dozen unauthorized regulations, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner, announced his intention of filing a Constitutional suit in the Supreme Court. In a sense, that took matters back to Franklin Roosevelt's "Court Packing" uproar in the 1930s, with more or less the same issue of a President illegally delegating legislative power to an executive agency. This once proved to be a convulsive national issue. So this book deals with it in a later chapter, because the state legislatures got to the Supreme Court first in a related Constitutional matter.

|

| Democratic U.S. Sen. Edward Kennedy |

This uncertainty must be quickly resolved. The final law has over 450 sections, so some can be suppressed for a long time before an absence is noticed. The President's public restatement of section 1251 after the policies had already been canceled, remains particularly baffling. There are times when it almost seems the President was daring the Legislative branch to sue him. Although it is possible this maneuvering is more aimed at the Tea Party than the Democrats, it would certainly be the most dramatic Constitutional crisis since the Court-packing attempt in the 1930s. It deserves consideration in detail, but first, we must review the other Supreme Court action in the early days after passage of the Act, which may or may not have been the start of an elaborate collision of historic proportions. Preliminary conclusions must be reserved. Speaker Boehner may call off his suit after the outcomes of the 2014 Senate elections are known. International events may take a sudden turn. And the financial markets may still contain some surprises. More directly, there may be actions by the central actors in what Senators refer to as "this train wreck". In view of its potential destructiveness, the only consolation is it might at least inhibit Congress and the President from this particular maneuver a third time in the future.

Soon combined with a disastrously failed computer program for Insurance Exchanges making it impossible for the program even to get started, 2014 appears to be a bad year for tranquil discussion. It dramatized that trying to bully through was a bad choice. Millions of letters notified clients their old insurance was terminated as "inadequate" while the President continued to appear on television programs assuring such a thing would never happen, -- all of this projected a pretty poor image.Text of Section 1501, renamed Section 5000A: MINIMUM COVERAGE