6 Volumes

Constitutional Era

American history between the Revolution and the approach of the Civil War, was dominated by the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787. Background rumbling was from the French Revolution. The War of 1812 was merely an embarrassment.

Philadelphia Since the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution began about the time America declared Independence. The young nation faced a clean slate and boundless opportunities.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia: Decline and Fall (1900-2060)

The world's richest industrial city in 1900, was defeated and dejected by 1950. Why? Digby Baltzell blamed it on the Quakers. Others blame the Erie Canal, and Andrew Jackson, or maybe Martin van Buren. Some say the city-county consolidation of 1858. Others blame the unions. We rather favor the decline of family business and the rise of the modern corporation in its place.

Great 1929 Depression and World War Two

The Treaty of Versailles probably caused World War II, making WW II just a continuation of WW I.

What Made Philadelphia Decline?

In 1900, Philadelphia was said to be the richest city in the world. Then, what happened?

Railroad Town

It's generally agreed, railroads failed to adjust their fixed capacity to changing demands. It's less certain Philadelphia was pulled down by that collapsing rail system.

It's generally agreed, railroads failed to adjust their fixed capacity to changing demands. It's less certain Philadelphia was pulled down by that collapsing rail system.

Camden and Amboy Railroad, connecting the economies of New York City and Philadelphia, was the initial American attempt to exploit Isaac Watts' invention of the steam engine. In time diesel and then electric power disiplaced the steam locomotive; steam engines do not define a railroad. In time, it's possible magnetic levitation could prove that even rails are not the central defining element of railroads, either. Inquiring after the defining quality of railroads is to arrive eventually at the inflexible character of owning exclusive rights to a strip of land ten or twenty feet wide and many miles long. That creates a monopoly for the right of way, but cannot evade the reality that railroads are a real estate investment without much value except as a way to create a transportation monopoly. When the monopoly is broken, the capital is not easily extracted.

Looking over the long rise of the railroads to dominance and wealth, followed by slow decline to bankruptcy, many observers now speak with hindsight. Railroads, they say, were not in the railroad business but rather in the transportation business. Successive railroad presidents had grasped that idea twenty years before the bankruptcy, but were blocked from successful entry into the trucking and airline components of the transportation industry. And another broad concept, that any business is just a pool of capital to be managed, encountered the futility of extracting illiquid capital from investments in the specialized real estate of a rail empire.

There's one associated story here of the dead hand of regulation, and another of the irresponsible behavior of industrial unions. There is room to reflect on inept management. But instead draw a different moral: the rise and fall of railroads is a struggle between catching up with shortages and succeeding too well, then struggling to reduce subsequent overcapacity. Obviously America started with a shortage of railroads when there aren't any at all in 1820. But by the late 1880's America had about twice as much rail capacity as the nation could employ. The nation's other industries then grew enough to catch up with this particular episode of rail overcapacity, but not before 169 railroads went into receivership, including the Reading and the Baltimore and Ohio. The following century was one of world wars and depressions, with industry periodically catching up then falling behind, in a constant struggle to match capacity with utilization of it.

Eventually, overcapacity won out and the railroads were pretty well snuffed out, taking railroad towns like Philadelphia down the tube with them. Overcapacity had lots of help, however. And not everyone agrees that the collapse of railroads explains Philadelphia's industrial decline.

Riverline: Camden and Amboy Revival

The RiverLine, a sort of diesel-powered overgrown trolley car line, has just opened on the Conrail tracks from Camden to Trenton. It runs every 30 minutes in both directions but unfortunately stops at 10 PM to let Conrail run freight trains at night. That's almost a perfect fit for the two operations, although it can leave baseball fans stranded at a night game at Campbell Park, or concertgoers at the Tweeter Center. The trains are running fairly full, partly because of their novelty, and partly because of the initial decision not to collect the $1.10 fare on Sunday, but mostly because the Riverline proved to be a better idea than anyone realized it would be. It's considerably cheaper for Philadelphia commuters to Wall Street to take the Riverline and transfer to New Jersey Transit at Trenton, for one thing. Even Amtrak encourages that, because high gasoline prices have filled up the Amtrak trains.

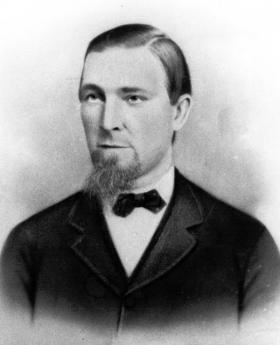

It's well worth a historical excursion on the RiverLine, which runs on the former right of way of the Camden and Amboy RR, the first railroad in New Jersey, chartered in 1830 by Robert L. Stevens. A genius of many talents, Stevens invented the iron rail which looks like an inverted "T," held in place by a system of plates and broad-headed spikes. The system is still in use today. Stevens also devised the use of wooden cross ties rather than granite ones, finding they resulted in a smoother ride. In 1834, he joined forces with another many-talented genius, Robert F. Stockton, who had earlier constructed a canal from New Brunswick to Trenton. Stevens then built a railroad beside the canal, subsequently extending it from Trenton to Camden. Stockton ran ferry boats from Perth Amboy to New York, and from Camden to Philadelphia. The full trip from New York to Philadelphia took nine hours, a remarkable improvement over the horse-drawn competition. The partnership also got the Legislature to confer monopoly rights, so the arrangement was highly profitable as well as an engineering marvel. Sixty years later, the Sherman Act would declare such monopolies to be crimes, but in 1830 they were considered a clever way for Legislatures to stimulate risky investment. The Pennsylvania Railroad bought the partnership and its monopoly in 1871, but preferred to bridge the Delaware River at Trenton, so the towns and track along the Jersey side of the river soon dwindled away. The RiverLine now provides a pleasant one-hour excursion along the riverbank, down the main streets of some cute little towns, past some remarkable woods and wilderness up near Trenton, and past Camden's urban revival at the other end.

Rail Station at Broad and Washington

Washington Avenue was called Prime Street before the Civil War and was an important trans-shipment center for the whole country. Rail traffic, coming down from New York and New England, came through New Jersey on the Camden and (Perth)Amboy RR, disembarked, and ferried over Delaware to the foot of Prime Street/Washington Avenue. Passengers then took horse-drawn cabs up Prime Street to Broad, or else they walked. At that point, travelers bound for further South would enter the imposing Rail terminus of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore RR, to re-embark. Philadelphia hotel operators hoped they would stay overnight; Philadelphia merchants hoped they would just transact their business locally, then go back home. Taking nine hours from New York, it was an inefficient transportation method by today's standards, but the Prime Street interruption served local economic purposes, which Chicago keeps in mind, even today.

Sketch map showing the area between Philadelphia and Baltimoreindicating drainage, cities and towns, roads, and railroads.

Consolidated February 5, 1838.

The interruption also worked the other way, inducing Southerners to go no further North with their business, thus strongly contributing to pro-Southern sympathies before the Civil War. Philadelphia was indeed the most northern of the Southern cities until the 1856 Republican convention (at Musical Fund Hall) started to remind other Philadelphians that the anti-slavery Quakers perhaps had a point. Even so, pro-Southern feeling in Philadelphia was wide-spread, even in the early months of the war.

|

| John Brown |

For example, in 1859 John Brown's body was brought forth on the PWB railroad, precipitating a pro-Southern riot at the Broad and Prime Station. There was a second riot the following year.

During the Civil War itself, the PWB railroad was a major military transport, carrying military supplies and troops to the battles, and bringing the many wounded troops back home for treatment. Quite a large military hospital was built across Broad Street from the rail station. All in all, the corner of Broad and Prime was a major center of the war, and may well have been one of General Lee's objectives when he launched the invasion that got stopped at Gettysburg.

|

| B& O Railroad |

After the Civil War was over, attention was finally paid to the need for better North-South rail transport along the Eastern Seaboard. Up to that time, European investment had pushed American railroading in an East-West direction. The Baltimore and Ohio were aimed at the Mid-West, while the New York railroads aimed at Chicago and beyond. Local politics in the seaboard cities tended to keep the competitors from linking and thus potentially capturing trade between the manufacturing North and agrarian South.

The Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore was the key link in the series of mergers which created the dominant Pennsylvania Railroad. Bringing northern traffic in through North Philadelphia to the new 30th Street Station,

|

| 30th Station |

and then linking it to the stub of the P, W, BRR, the way was being paved for Ascella Express trains to shoot from Boston to Washington, perhaps eventually to Florida. The side-track from West Philadelphia to Broad and Washington was allowed to wither, and of course, the whole Camden and Amboy RR became scarcely more than a trolley line All that was left as a challenge to the Pennsy was to get past B and O obstructionism in Baltimore. This last step was finally accomplished with the discovery of some legal loopholes related to an existing right of way for a local commuter line in Baltimore, where permission for a branch line was broadly interpreted, and a surprise tunnel dug to link it up to the other parts of the Pennsy. Amtrak passengers nowadays usually move through the Baltimore tunnel systems without noticing them, but occasionally a train breaks down inside the tunnels. Then, they prove to be rather dark and damp as the passengers with their laptops are transferred to another train.

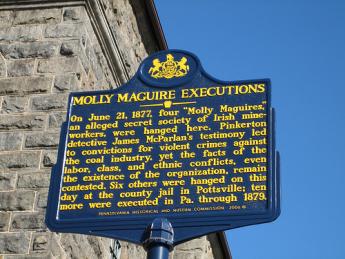

Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania (1)

|

|

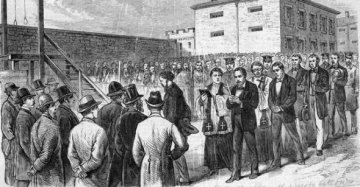

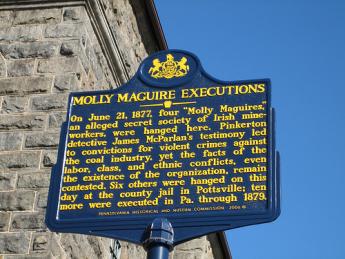

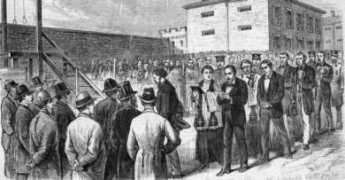

| Pottsville Hanging |

|

| Historical Marker |

However, resistance to conscription during the Civil War gave newcomer clannishness more serious consequences. This was particularly true when it inserted a surprising pro-slavery (or at least anti-emancipation) protest into the very center of the Northern Union, around Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Whatever the South was fighting for, the North was primarily fighting to preserve the economic benefits of greater trade in larger markets -- a concept loosely described as "preserving the union". A second twist to anti-Mollie repression was later added after the war was over, when the 19th Century Industrial Revolution created another untamable tribe, the Robber Barons, for whom uncooperative behavior was a tendency not to be trifled with.

Basic behavior of the Molly Maguires in action followed a simple pattern. Males dressed as females in blackface made extortion threats against members of the dominant society, protesting that their own subsequent violence was merely justice for heartlessness toward widows and orphans. Since the Mollies out of costume mingled cheerfully with those they secretly called oppressors, for actual assassinations they either called in the help of distant outsiders or drew lots to choose the assassin locally. The community would then unite to provide a vocal alibi and profess to be offended by the accusation. To increase intimidation, death threats were pinned to the door.

Molly Maguires of Pennsylvania (2)

|

| the Mollie threat in the coal regions |

IT was in their interest for both the Molly Maguires and their chief enemies to exaggerate the Mollie threat in the coal regions. Mollies hoped to achieve more pay for less work by intimidating employers, the more intimidation the better. The management of the mines and railroads more shrewdly hoped to mobilize public sympathy to their side, in the newspapers, courts, and legislature, by exaggerating the undoubtedly real menace of lawless, unpatriotic behavior. There have since been great strides in the art of slanted propaganda, and it takes more finesse to mobilize modern opinion. Having watched Hitler and Stalin in action, and noticing our political parties going in the same direction, we would now regard the behavior of 1870 to be crude, and therefore less effective. But there was one very public rebuttal to what the Mollies were claiming. Although they portrayed themselves as oppressed Irish in an English dominated world, their main enemy was himself a well known Irishman.

|

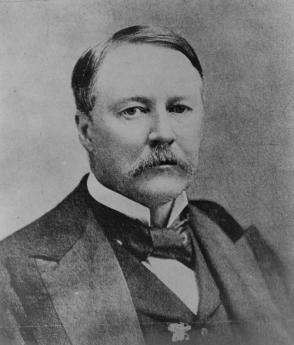

| Franklin Benjamin Gowen |

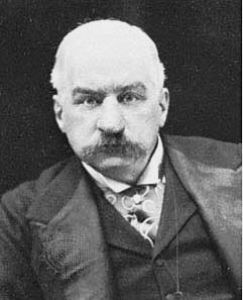

Franklin Benjamin Gowen, President of the Reading Railroad from 1870-1886, was both Irish and definitely larger than life. As one illustration of his extraordinary energy, he died at the age of 53 but had risen from moderate circumstances to control what would become the largest railroad in America by age 34, ultimately being forced from office by J.P. Morgan while still only 50. By some measures, in those sixteen years, he had made the Reading into the largest corporation in the world, even though he had comparatively little interest in and no training in railroading. Although born in Mt. Airy, he apprenticed himself to a lawyer in Pottsville, and at age 26 became District Attorney in the coal region during the first outbursts of Molly Maguire violence. Although he had never gone to law school, he seemed to love the courtroom and continued to work as an independent trial lawyer all during the time he was president of the railroad. One commentator remarked that to read his speeches in cold type was still enough to jeopardize one's judgment. During his later battles for corporate dominance, he twice filled the Academy of Music with stockholders, holding them spellbound for three-hour speeches. On this evidence alone, one. supposes he had a lifelong tendency to stretch facts.

|

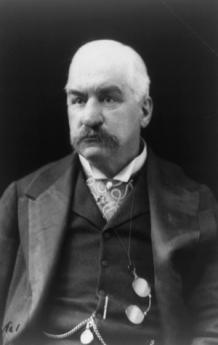

| J.P. Morgan |

Following the Civil War, labor relations in this rough coal region became temporarily peaceful. The prosperity of a post-war boom was probably mainly responsible, but it was also true that the labor movement was pretty well smashed by the response to patriotic feelings, slavery was no longer an issue, and huge casualties in the war had created labor shortages. However, these same factors made dominance of the coal and railroad industries more attractive. Franklin Gowen set about merging the small railroads in the coal region into an empire, and used his control of freight costs to force the coal distributors and the coal producers into subservience or forced sales. The charter of the Reading Railroad inconveniently prohibited the railroad from owing mines, but other competitors were legally permitted to do so. Using the fairness argument and probably both bribery and threats, he "persuaded" the legislature to permit a new corporation to own mines, and permitted railroads to own the new corporation. The Reading then promptly owned the mines in a two-step arrangement, couched in bewildering legal language. Gowen had no compunction about doubling freight rates and then doubling them again until he got what he wanted. Anthracite coal was the driving engine of America's Industrial Revolution, and Gowen controlled it. He was a wild and reckless spender, he thought big, and was ready to smash any opposition. His ambition set him to building a transcontinental trunk line which would compete with the Pennsylvania and New York Central lines, both under the control of J. P. Morgan or his allies. This venture failed and became the basis for the present Pennsylvania Turnpike . Ultimately, Gowen's ambitions were thwarted by his reckless spending putting him at the mercy of English bankers, allied to the Morgan interests. Underlying this was an economic fact: Henry Frick had found a way to make bituminous coal into coke, which was a cheaper fuel for steel making than anthracite. Financed by Morgan and organized by Andrew Carnegie, the steel industry moved to Pittsburgh.

|

| John Sidney, founder WBA |

Meanwhile, what happened to the Molly Maguires? The financial panic of 1873, started by the collapse of Jay Cooke's financial company, precipitated layoffs and cost-cutting and stimulated a new rise of labor unrest. The Mollies shot some mine managers, but most of the labor organized under a fairly moderate union called the Workingmen's Benevolent Association. More moderate or not, they still threatened strikes and demanded concessions, and Gowen set about to wipe them out. As headstrong and impulsive as he was it's even possible he believed the Molly Maguire movement was stronger than it really was. But it would not have mattered. The Pinkerton agency was hired, detailed studies were prepared of the nature and leadership of the Molly movement, evidence of wrong-doing was collected, and some of the right people were hanged. Once more, the labor movement was crushed, largely by characterizing all labor unions as lengthened shadows of the Molly Maguires. And labor has never forgotten or forgiven. Even a century later, any sort of labor ruthlessness especially in Congress, is proclaimed justified since any capitalist, or even any Republican, is a covert Franklin B. Gowen. And quite possibly either English or protestant, as well, even though Gowen happened to be as Irish as any of the Mollies.

It's a great pity that seemingly the last opportunity for national adoption of the Whig philosophy of upward social mobility was exiled from American political discourse. Everybody is better off with peace, law and order; given time, our political system does offer everyone at the bottom of the heap a fair opportunity to rise to the top. After a couple of centuries, it thus ought to be obvious that class warfare hurts everyone, helps no one. But at election time, both parties feel compelled to characterize each other as either a Franklin Gowen, or a Molly Maguire.

As a footnote, Frank Gowen died from a gunshot in Washington DC in 1889. An extensive investigation was conducted, and there is almost complete certainty that no Molly Maguire was responsible. But the bullet came from a strange angle, there was no suicide note, and it remains possible that someone else, not suicide, was responsible. Gowen had plenty of other enemies.

Look Out For That Ship!

Tales of the Sea abound, even a hundred miles from the ocean.

|

We are indebted to the President of the Maritime Law Association of the U.S., Richard W. Palmer, Esq. (who unfortunately died in March 2017 at the age of 97), for both a strange definition and an amusing story. An "allusion" is a collision between a ship and a stationary object, such as a bridge or a dock. As you might imagine, the ship is almost invariably at fault, mainly through errors of the pilot, although hurricanes and other severe weather conditions can make a difference. Moving ships have been running into stationary objects for many centuries, and almost every allision contingency has been explored. Ho hum for maritime law.

The Delair railroad drawbridge over the Delaware River at Frankford Junction is just a little different. It was built in 1896 when the Pennsylvania RR decided it needed to veer off from its North East Corridor to take people to Atlantic City. For reasons relating to the afterthought nature of the bridge, the tower for the drawbridge is located half a mile away, out of a direct vision of the ships going through. Also, a late development in the history of the river was the construction of U.S. Steel's Morristown plant, bringing unexpectedly huge ore boats from Labrador to the steel mill. The captains of the ships pretty much turned things over to the river pilots, for the last hundred miles of the trip.

|

| Delair Railroad Drawbridge |

Shortly after this iron ore service was begun, the inaugural ore boat Captain had a little party with some invited guests. So it happened that the Commandant of the Port, the Admiral in Charge of the Naval Yard, and other equally high ranking worthies like the head of the Coast Guard were on the bridge of the ore boat, taking careful notes of the procedure.

The ship tooted three times, the shore answered back with three toots. In real fact, they were connected by ship-to-shore telephone for most of the real business, but this grand occasion called for an authentic nautical ceremony. Three toots, we're approaching your bridge. Three toots back, come ahead, the coast is clear. The admirals scribbled it all down.

As the ship approached the point of no return, beyond which it could no longer stop or turn in time to avoid an "allusion", the people on the bridge were appalled to see a train crossing the bridge ahead. Several toots, loud profanity on the ship to shore phone.

No worry, answered the bridge, we'll lift the drawbridge in plenty of time. But half a minute later the bridge controller made the anguished cry that the drawbridge was apparently rusted and wouldn't open, to which the captain shouted, "This ship is going to take away your blankety-blank bridge and sail right through it".

At this point, the pilot took matters into his own hands, and violently threw the rudder hard left, swinging the ship sideways, soon nudging the bridge with some damage, but nothing like the damage of a head-on allision. The lawsuit, as one might imagine, was the outcome.

The attorneys for the railroad were pretty high-powered, too, and had piles of legal precedents to cite. But they were quite unprepared for Dick Palmer to put the Commandant of the Port on the witness stand, reading slowly and painfully from his very detailed notes about the conversations on the bridge, about the approaching drawbridge.

And so, Philadelphia can now claim to have experienced one of the very few instances where a ship ran into a bridge -- and the court found the bridge to be entirely at fault.

The Center of Town

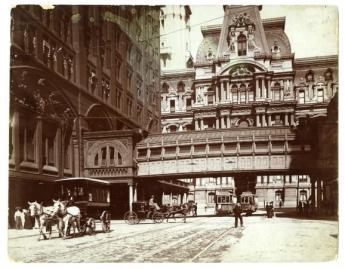

|

| city hall |

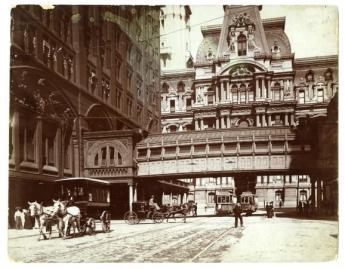

It took two hundred years for the inhabited part of the city to reach the square which William Penn had envisioned for the center of his green country town, and by the time it did, the area around City Hall had come to resemble the town planning concepts ordinarily associated with the Scotch-Irish immigrants.

It sort of goes like this: the Scotch-Irish had been kicked out of Scotland and they were soon kicked out of Ireland, so they were far less emotionally attached to their local soil than other European groups. So they were probably the first group to regard real estate as a commodity rather than a repository of wealth, or a religious shrine, as other groups often do. It soon became evident to them that the best real estate was usually found at the crossroads, and the more important the intersecting roads, the more valuable that real estate was going to be someday. Accordingly, early Scotch-Irish settlers roamed around their new country, looking for likely crossroads, and buying up the local property for speculation.

The pattern of the diamond appeared, with a town square placed at the crossroads, traffic diverted around the square, and commercial real estate established around the rim of the square which usually had a flagpole placed in the middle of the central park. New England had city centers and town commons, but the two were usually not the same thing. The diamond pattern is very characteristic of rural Pennsylvania, and up and down the Appalachian valleys where the Scotch Irish had spread. It is the pattern of Philadelphia City Hall Square, no matter whose idea it was originally. Let's face it. City Hall is at a crossroad of the two main traffic arteries, Broad and Market Streets, wide and straight, stretching for miles in each direction.

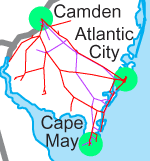

Railroading Haddonfield

|

| Haddonfield Map |

For a century or more, Haddonfield has had a railroad. Both the Reading and the Pennsylvania railroads ran through Haddonfield on their way from Philadelphia to Atlantic City, and later on, they were combined in the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Line. In 1950, the coal-fired steam locomotives still made a grade crossing on Kings Highway and tooted at the outskirts of town. A little awkward, dirty and dangerous, perhaps, but it had to be admitted that regular train service to the Shore was nice, as was regular commuting to Philadelphia. At least once a day, an elegant old train named the Nelly Bly made a round trip to New York, for those who occasionally wanted to take in a show, or do Christmas shopping in style. From the looks of some of the larger Victorian houses in town, there might even have been a few bankers going to Wall Street for important matters. Haddonfield was sleepy, but it had made things very convenient for itself.

And then, around 1970 the price of Haddonfield real estate tripled overnight. The Delaware Port Authority announced its plans for PATCO, a high-speed regular subway-surface line. Now that it is in existence, we have clean comfortable safe trains every seven minutes to the Center of Philadelphia. The express trains used to take eight minutes to Philadelphia, but now we only have locals who take twelve minutes. The main complaint is that there is not quite enough time to read the newspaper.

There's a personal story here. In the articles about the coming high-speed line, I noticed two things: there was to be an elevated overhead track through Haddonfield, and the director of the Port Authority had been a West Point classmate of my uncle. Having spent four years in New York City, my image of an elevated train was highly unfavorable. They were noisy, and the noise created slums all along their path. Not what was wanted in tree-lined Haddonfield, at all. And the General, who among other things was a neighbor up my street a few houses, created a means to change the plans. We held a mass meeting in my house, and among those present was a former regular-Army major, who had been the track engineer for the Illinois Central. He said that he had been through such arguments many times, had usually beaten down the opposition, but as a matter of fact, putting the rail line below grade was perfectly feasible. With that, one thing led to another, and General Casey finally one day was heard to say, "All right, I'll do it. But don't tell Collingswood." Collingswood is two stops closer to Philadelphia, and the main point was that a very popular religious radio station was located a hundred yards from the proposed line. One day, the minister of this station woke up to see an elevated -- an elevated -- being built outside his window. You can imagine all the rest, the radio broadcasts, the protests, the confrontation. But unfortunately, it was too late to make a change of plans.

As an epilogue, it can now be seen that there would have been advantages to the original design. The trains from Philadelphia to Atlantic City run immediately alongside the tracks of the high-speed line for a mile in Haddonfield. If they weren't all squeezed in a ditch, there might have been room for an interchange between the two at Haddonfield. But we don't care, we don't care. When we want to go to the shore, or to New York, we will drive.

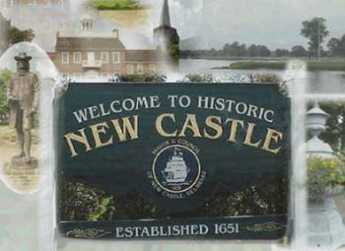

New Castle, Delaware

New Castle is easy to get to, but hard to find. It's right on Delaware Bay, at the start of the old National Road (Route 40), next to two huge bridges, a few miles from the main north-south turnpikes, a couple of miles from an airport -- and lost in a sea of suburban housing and highway slums. It's lost, so to speak, in plain sight.

|

| New Castle, Delaware |

And yet it is a perfect jewel of early American history and architecture. It's just as attractive and historically important as Williamsburg, Virginia, except these buildings are not reproductions, but the real thing. The town says it was founded in 1651 by Peter Stuyvesant, but Peter Minuit in 1638 could make a claim to be even earlier. Located at the narrow neck of the funnel that is Delaware Bay, it was a natural place to start a colony, eventually to be the capital of the state. The Delaware River makes a rightward turn at that point, and creates a river highway all the way to Trenton. But a few miles upriver at Tinicum, now Philadelphia International Airport, the river started to fill up with islands and snags; was it better to locate upriver or downriver from the narrows? New Castle was placed downriver.

|

|

New Castle's courthouse is the epicenter of the arc from Maryland to the Delaware River. |

But in 1777 the British fleet came to visit with hostile intent, and New Castle could look out the windows along the Strand right into the mouths of ships with twenty or thirty cannons pointing at them. Philadelphia, on the other hand, was protected upriver by a series of mud flats and barricades at Fort Mifflin that could quite effectively bar passage to enemy sailing ships. Delaware got the point, and shortly thereafter, the capital of Delaware was prudently moved to Dover, while even the county seat of New Castle County was moved to Wilmington. New Castle had a big fire in 1824; rebuilding afterward accounts for much of the present uniformly Federalist architecture. The final nail in the commercial coffin of the town was driven by the Pennsylvania Railroad, which just by-passed the town. For a century, this little architectural jewel just sat there in the fields, until the narrow neck of the Delmarva Peninsula became such a transportation crossroads that the fields filled up with construction more appropriate to Los Angeles. New Castle disappeared, without moving an inch.

|

|

100 Harmony St., New Castle, DE 19720 (302) 328-2413 |

For fifty years in Colonial days, the rector of Immanuel Episcopal Church in New Castle was one George Ross. His son, also named George Ross became a lawyer in Lancaster and signed the Declaration of Independence. His widowed daughter, Gertrude Ross Till married George Read, a lawyer in New Castle who also signed the Declaration. And, a third signer Thomas McKean, lived two houses away. George Read had studied law under John Moland, whose house served as Washington's headquarters in 1777.

The northern border of Delaware is a semicircle, with a twelve-mile radius based on the cupola of the New Castle courthouse. It was originally the border of New Castle County, and it proved to be slightly imperfect. In the first place, it extended across the Delaware River into New Jersey, but it was a nuisance to go there, so that segment of land was abandoned to New Jersey. However, the legal border of the State of Delaware, therefore, extends to the high-water bank of the river on the New Jersey side, rather than running down the middle of the river. The significance of this curiosity appeared when the Delaware Memorial Bridges were built, and all of the tolls go to Delaware, instead of being split between the states as is more customary. The other problem with the semi-circular arc was that three lines meet at the northwestern corner of Delaware, and each was defined in its own way. The Mason-Dixon line goes due east-west, the border with Maryland goes north-south, and the idea was that the semicircular arc would meet the other two lines at a point. However, the instructions could be read in two different ways, leaving a little "wedge" of territory that could be reasonably said to lie in either Pennsylvania or Delaware, depending on the sequence of describing them. This was certainly a circumstance where any decision was better than no decision, but it took until 1921 for the states to harrumph their way to a final pronouncement. In the meantime, the disputed wedge of land was a good place to have duels, cockfights and other matters of questionable legality.

REFERENCES

| Lewes, Delaware: Celebrating 375 Years of History Kevin N. Moore ASIN: B006DL8TC6 | Amazon |

Willow Grove Park

|

| Richard Karschner |

The Right Angle Club was recently highly entertained by a talk by Richard Karschner about the hay day of Willow Grove Park. Mr. Karschner appeared before the club in full uniform of the Marine Marching Band with medals and quickly demonstrated an immersion in this topic that must have taken a lifetime to perfect. He put on a virtuoso performance, a prepared speech perfectly timed to an automated slideshow, which was in turn in perfect synchrony with an automated musical background, exactly tailored to fit the momentary subjects. He concluded with a brilliant brief solo on the cornet (trumpet), using double and triple tongue-ing. To some of us who remember some futile struggling with the trumpet in our high school marching bands, the skill demonstrated was certainly impressive.

|

| Music Pavilion |

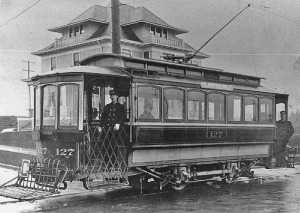

To go back a moment in time, the trolley car was the main method of public transportation in the last half of the 19th Century, blanketing the cities of America and their suburbs, and connecting to the trolley lines of other cities through an interurban network. Somewhere the idea developed of building Amusement Parks out at the far end of suburbs, to attract riders into using the trolleys for more than just commuting; there may have been as many as seventy or eighty such permanent circus grounds in America at one time, with more elaborate attractions that could be managed by traveling circuses. Philadelphia had several such trolley parks, notably Woodside Park in Fairmount Park, serviced by the "Park Trolley". But in 1896 Willow Grove was created on the edge of Abington, far more elaborate than any others, at the intersection of Old York Road and Easton Pike (Rte 611). Its terminal could hold as many as a hundred trolleys at once; the ride from Center City Philadelphia took 70 minutes and cost 15 cents. The area had mineral springs and had long been a favored vacation spot. Horace Trumbauer designed four or five of the buildings, and the Park eventually included a lake with rental boat rides, an arboretum, amusement rides, restaurants, a fun house, silent movie theaters, rodeos, roller coasters, a picnic park, and even an artificial mountain with a slow scenic ride up but a rip-roaring fast descent. By far the most central feature of Willow Grove was the 4000-seat music center, dominated by John Philip Sousa and his band giving four performances a day. Other musical performers were Victor Herbert, Walter Damrosch, Arthur Pryor ("The Whistler and His Dog"). Many of the ideas of Willow Grove are now to be found in the modernized form at Disneyland, but for twenty-five years music under the direction of John Philip Sousa was really the central unifying feature.

|

| John Philip Sousa |

It's generally held the arrival of radio broadcasting caused the decline of Willow Grove, although "The March King's" immense energy declined toward the end, as he began to enjoy being a multimillionaire. The composition of marches was in fact only a minor part of his musical output, which included among other things 16 full-length Broadway musicals. He was a national champion trap-shooter and a horseman of some note. One arm became nearly useless to him after a fall from his horse. Meyer Davis took over in the last few years, but a major fire pretty well finished the place off just in time to be buffeted by the 1929 crash. There was an attempted resurgence in 1933, but circumstances which made Willow Grove a successful "Virtuoso Solo" just couldn't withstand the competition of the automobile and television, and the land was finally broken up and sold for $3 million in 1976. Remnants of the gilded past are now scattered around the Willow Grove Shopping Mall, for those who wish to renew fond memories from their childhood. Or perhaps their grandparent's childhood.

Sayre / Athens

|

| General John Sullivan |

Running west from Oneonta and Binghamton, NY, the North branch of the Susquehanna runs due west for about fifty miles until it turns abruptly south at Sayre, PA. In the course of this westward run along the northernmost ridge of the Endless Mountains, it passes Apalachin NY, where the mobster chieftains got caught by the state police while holding a convention. At Sayre, named after an eastern railroad financier of the 19th Century, it joins the Chemung River at a large bowl-shaped refuge in the mountains which shelters it somewhat from the ferocious snows for which this part of Upper New York State is famous. Sayre usually gets a heavy snowfall or two in January, which lies on the ground until the Spring thaw in April. But that's pretty mild for this region, and the Iroquois made it a sort of headquarters, where Queen Esther of head-smashing fame made her home just before the Wyoming massacre in which she figured so prominently. Consequently, General Sullivan made his famous march to destroy the Iroquois by going northwestward up the Susquehanna to Athens, rather than following the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, as somehow seems more probable. Actually, Sayre was more of a 19th Century town, with the original settlement concentrated a few miles south at the region of Athens. Sayre is more modern, once was the location of a huge locomotive repair center, and has the Guthrie Medical Clinic at Robert Packer Hospital. Athens is older, quieter and has more stately charm, and is actually on the Chemung River with a two hundred yard portage to the Susquehanna.

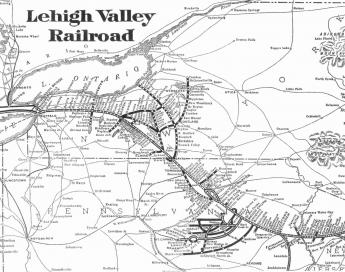

|

| Lehigh Valley RR Fame |

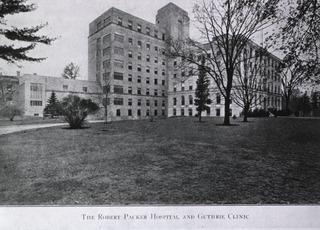

Robert Packer was considered to be the ne'er do well son of Asa Packer, that go-getting industrialist of Mauch Chunk/Jim Thorpe, and Lehigh Valley RR fame. The father is said to have sent his son up to Sayre to get him out of the way, but once freed of the old tyrant's grip, Robert built things up into the second-largest locomotive repair center in the world. Robert Packer never had children and eventually set about building up the Robert Packer Hospital. Much taken with the Mayo Clinic model, he called Charlie Mayo and asked if had someone to suggest for running the local institution. Indeed, Mayo had just the fellow, Guthrie, who like the Mayos was a surgeon with a specialty in removing enlarged thyroid glands. As long as the railroads flourished, the Guthrie Clinic was headed toward the status of a major medical center with private rail cars for the surgeons and the like. However, the advent of diesel locomotives put an end to the main source of local prosperity, and the Guthrie Clinic settled down to a more modest status of a regional medical center, mainly in competition with the Geisinger Clinic further south on another bend in the Susquehanna. At present, the Obama Administration seems much taken with the model of the Midwestern group practice, of which both Guthrie and Geisinger are models. Perhaps the politicians do not realize that all of these clinics were based economically on the principle that surgeons can make enormous incomes if they are fed enough cases. Consequently, they are willing to reduce their own income in order to make group practice more attractive to the "feeders"; the department of surgery subsidizes the department of general medicine. Their competitors have long grumbled that this arrangement was an elaborate evasion of the medical ethical prohibition of fee-splitting. Most of that feeling has subsided, but a more serious present criticism is that the Obama Administration mainly seems determined to reduce surgical fees, so the whole arrangement may collapse when they do.

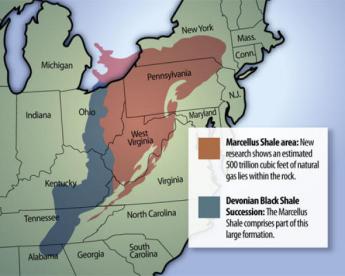

|

| Robert Packer Hospital |

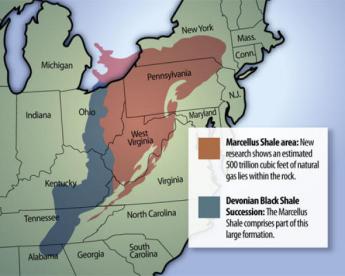

Curiously, prosperity looks as though it may be ready to return to the Endless Mountains, in the form of the fracking method of gas extraction from the Marcellus Shale which underlies this region. Coming as it does at a time when domestic oil production is growing inadequate, but alternative energy sources are not yet competitive, rail freight is returning to the region, and truckers by the thousand are migrating from economically depressed regions like Detroit. For reasons not immediately clear, the huge trucks which import water and chemicals for fracking are driven by non-residents. The smaller trucks which carry away (to Northern New York, they say) the brine effluent from the wells, are driven by locally recruited truck drivers. A certain number of bar room fights have been rumored to have grown out of this situation. Camp followers of the fair sex have occasionally drifted into town, but so far not in large numbers.

As the region has evolved, the third town of Waverly NY has joined the other two in what amounts to a seamless conurbation of about 30,000 people, nestled in the cozy valley.

South Amboy Explodes

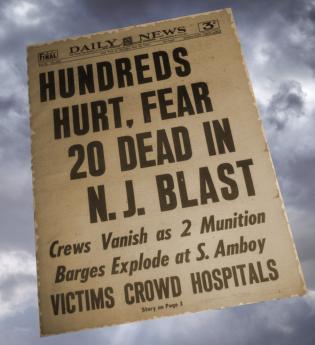

|

| Explosion |

South Amboy, New Jersey, is a waterfront industrial town on a remote promontory behind Staten Island, jutting into lower New York Bay. It's across the Raritan River from historically important Perth Amboy, but it's fair to say that few people ever heard of South Amboy until sunset on May 18, 1950, when they suddenly heard a lot. An entire freight train, five lighters, and a railroad pier suddenly exploded and disappeared. About twenty-five people were never seen again; the largest piece of metal from the explosion was only about a foot in length. A significant part of the town was leveled, steeples were knocked off churches, and windows were broken in five surrounding counties. Considering what caused it, it seems remarkable that so few people were killed. The explanation usually given is that the explosion blew straight up and straight down; the distant windows were smashed by pressure implosion.

When Pakistan split off from the rest of India, there were bloody migrations in which millions of people died. So Pakistan bought the rights to the design of certain land mines to protect its new borders and contracted with a firm in Newark, Ohio to manufacture the mines. Two trainloads of these explosives were shipped from Ohio to a railroad pier owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad in South Amboy, to be lightered out to a waiting cargo ship and sent to Pakistan. The first of these two shiploads sailed off uneventfully, and on May 1, 1950, the second shipment had already left Ohio and was underway, when the Coast Guard suddenly declared the South Amboy pier to be closed and forbidden. As the train chugged slowly eastward, frenzied negotiations took place with Admirals in Washington. There was plenty of time, because the train moved very, very slowly and it was detoured over six different railroads to Wilmington Delaware, where the Hercules Powder Company had packed two freight cars with dynamite, which were to be hooked onto the end of the train as it inched its convoluted way to South Amboy.

|

| South Amboy Explodes |

The method of packing the land mines was of some importance during the huge litigation which inevitably followed. Land mines were packed in cardboard boxes about six feet long, divided into six compartments. Our own Army regulations about such things state that never, never should fuse be packed in the same carton with the mines. However, this particular shipment had five mines to a carton, with the fuses in the sixth. It was later argued that this particular arrangement proved harmless in the first of the two Pakistan shipments, but there was the testimony that defective fuses were removed from those boxes and passed back up the line, where those deemed satisfactory were re-packed in the cartons which were in this, the second shipment. A fuse, by the way, does not quite describe these objects, which were screwed into a hole provided on the bomb part. They contained a spring and a steel ball in a tube; when the gadget was cocked it was held by a hare-trigger. The idea was that the pressure of stepping on the mine shot the steel ball into the ball of explosives, and boom.

The railroad ammunition pier, for some reason called The Artificial Island, consisted of two rail lines extending a quarter mile from land, but no structures. Stevedores transferred the boxes from the train to the lighters, and then five lighters took the partial shipments out to the anchorage where the ocean freighter was waiting. The deck of the lighters was lower than the train tracks, so a wooden ramp was laid from the freight car to the lighter, resting on several mattresses on deck. It all worked on the first shipment, didn't it?

Well, it didn't work this time, and we have no way of knowing who stumbled or dropped something; we only know it all went sky-high. For this, the ship-owners were delighted because it is a well-established principle of Admiralty law that unless the ship was in contact with the owners, their liability is limited to the value of the damaged vessel. Under conditions of total disintegration, that means the lighters had a liability of zero. But there were six railroads, the Pakistani government, the Coast Guard and the two manufacturers of the explosives available to sue. Everybody had insurance, so a dozen insurance companies were involved. All of the victims and hundreds of people with property damage, all had lawyers; everyone agrees that many lasting friendships were established among lawyers who were milling around. Finally, the judge declared this case just had to be settled, or else it would continue for the rest of everybody's lifetime. The total amount of the claims submitted came to $55 million. Obviously, the settlement would be for less than that, but settlements are kept secret and you are not supposed to know how it turned out.

So, the question that remained was this. If everybody was insured, why not let the insurance companies haggle about who owed what to whom. Why did all of those railroads have lawyers hanging around? Well, the answer is a lesson for all of us. You need a lawyer to watch your insurance company's lawyer, because once a claim action begins, you and your insurance company develop a conflict of interest.

www.Philadelphia-Reflections.com/blog/1482.htm

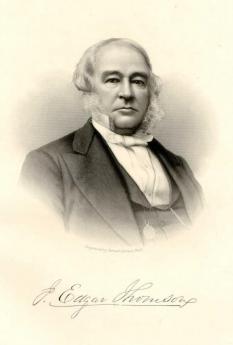

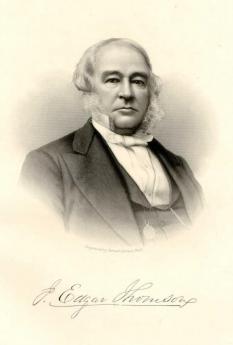

J. Edgar Thomson, Pres. PRR 1852-1874

|

| J Edgar Thomson |

The third president of the Pennsylvania RR converted a local Philadelphia line into a national railroad, the largest corporation in the world. Thomson, born in the Quaker country of Springfield, Delaware County, was the son of a chief engineer of the Delaware-Chesapeake Canal and had worked closely with his father. After an introduction to the rail business, he worked on four other railroads before joining the Pennsy at the age of 29. The State of Pennsylvania had by then constructed a series of unsuccessful canals along most of its important waterways during the Whig days of faith in government, but Thomson knew canals very well and recognized that their rights of way were best transformed into rail lines. By acquiring these unprofitable companies, he rapidly changed the PRR into a state-wide rail network, of which the famous Horseshoe Curve at Altoona was the most notable achievement. From there he moved to convert wood-burners into the coal-burning locomotives developed in Philadelphia and shifted from iron rails to steel ones. The probably unexpected effect was to convert all railroads in the nation into customers of steel and coal, Pennsylvania's main resources. Andrew Carnegie was so pleased he renamed his main steel company into the J. Edgar Thomson Works.

|

| Steam Engine on The Horseshoe Curve |

Thomson was quiet and conservative, never engaging in the high-jinks so characteristic of the rail barons of that day, leasing land rather than buying it whenever possible, expanding steadily but methodically, and never confusing revenue growth with profits. By 1870, Pennsylvania had expanded to a Jersey City terminus at New York harbor, and Chicago and St. Louis at the western ends. Within Pennsylvania, the line had expanded from 250 miles of track to over 6000. It was the largest corporation in the world. Underneath all this expansion was the Thomson system of decentralized management, essentially consisting of giving local control to division superintendents, but standardizing the corporation to superior approaches as they surfaced among the networked superintendents. His was a brilliant synthesis of the precision of an engineer combined with the cooperative sharing of a Quaker meeting. It was easy to describe but difficult to imitate, particularly by executives who boasted lifelong avoidance of the approaches of both the engineering profession and the cooperative diffident Quakers, in favor of swashbuckling, overborrowing, and muscle -- so popular at the time of the Gilded Age.

Thomson's fortune grew to seven or eight million dollars. While that was both comparatively modest by railroad standards and yet extremely affluent for the times, at his death, he had mostly given it to charity.

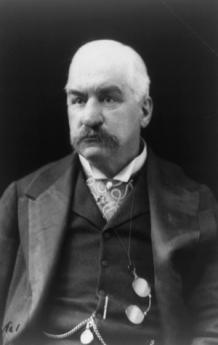

Drexel and Morgan, Investment Bankers

|

| J.P. Morgan |

In the 1840's it was America that was the developing nation, and Europe was the rich old developing country with risk capital looking for opportunities. The situation is reversed now, and we have developing country funds devised for the purpose of investing in risky foreign adventures without knowing much about them. Anthony Drexel, born in Austria but doing business at 3rd and Chestnut Streets, could see all the problems which now would face an American investor wishing to take a flier in, say, the African Central Republic. How are you supposed to tell a good one from a bad one; how do you keep from being fleeced? Today's investor in Private Equity becomes a limited partner of a general partner who may do his best but can look forward to your fees and commissions no matter what his performance turns out to be. If he sits in an office in America, he likely knows little of what is going on in Africa; if he works in Africa, he is beyond your reach in the event of shenanigans. Drexel's solution was to offer a job to young J.P. Morgan.

|

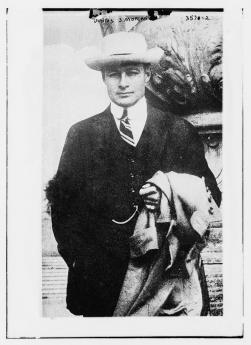

| Junius Morgan |

J.P. was to run the New York office of Drexel and Company. His father, Junius Morgan, was to work in London. Junius would gather up investment funds from Dukes, Earls and similar, and send them to America. Meanwhile, J.P. Morgan would have the job of discovering the best investments and overseeing the ventures, which at that time were mostly railroads. At this point, Drexel's approach began to differ from the current investment fund, which mainly tries to give good advice. J.P. was a leader in Wall Street and an informal enforcer of rectitude. As everyone sort of knows, Pierpont Morgan was one mean mama. He may seldom have actually done it, and he certainly never said it in so many words, but his manner radiated the news: if you mess around with one of my clients, I will promptly ruin you. That he was clearly able to do so was sufficient threat. The Wall Street air was filled with his maxims, such as "I shall never do business with a man I don't trust." and "Brains don't make you rich, a character does." He was a tough man, in a tough business. Underneath his pompous maxims, the threat they implied was real.

|

| George B. Roberts |

Morgan had a general approach to industries, developed well before the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1895, and best exemplified by his approach to transcontinental telephone systems. Instead of starting a telephone company on the East Coast and expanding it to the rest of the country, he took the approach of encouraging the creation of dozens of small local telephone companies. Watching their performance, he merged with the ones with the best track record and set about quashing those who refused to merge. From his point of view, it sorted out the good ones from the bad ones and created a nation-wide network in an undeveloped country much more rapidly than trying to establish a national champion by building it up. Variations of this simple approach were successful in the steel, coke, banking, and railroad industries. All of these were highly cyclic industries; when there was a general financial crash, it was time to buy up the survivors, and squeeze the hold-outs. Most people regarded a financial panic as something to be avoided at all costs. For the Morgan firm, they were buying opportunities which came along every few years if you saved your cash and waited for them. During the 1929 panic, another financier famously rubbed his hands and remarked that "It would squeeze all the rottenness out of the system."

|

| Corsair |

In the case of the railroad industry, J.P. Morgan set about consolidating small railroads into the New York Central about 1880. In 1885, he reached a famous accommodation with the Pennsylvania Railroad, called the "Corsair Accord" after his yacht on which it was signed. The two actual signatories were George B. Roberts, President of Pennsylvania RR, and Chauncey Depew, acting on behalf of William H. Vanderbilt, President of the New York Central RR, who was sick and eventually died in a few months. The agreement was relatively simple: the two railroad giants would stay out of each other's way. Ten years later, the Sherman Antitrust Act would be enacted, flying the flag of enshrined competition as the national goal in every industry. The Act was mainly directed against Morgan's ideas if not his person since Morgan would unashamedly point to duplication of rail systems as a perfect example of asinine behavior. Political correctness was not his style.

RR Monopoly Self-Destructs

|

| Train Robbery |

A strange part of capitalism is that no company seems to last forever; seventy-five years is a long life for corporations. For this puzzle, partial insight emerges from American railroad history. After overcoming their novelty and growth pains, railroads soon had to confront the accusation their great size was itself a problem, unbalancing the playing field. Too big? Management resists that argument. Getting bigger was always good, especially when dealing with foreign competitors. A vital public treasure? Needing railroads doesn't create ownership rights, building them does. Railroad founders discovered a public need and served it; but the public replied it was their need and so it was their railroad, only temporarily in the hands of managers. Nothing useful was going to come of this faux debate, which structured itself in the 19th Century to reach equilibrium, not agreement. There is some reason to hope the ending of the Cold War a century later may have established more permanent understandings, but even those remain hostage to future history. By 1970 history seemed to be making quite the opposite verdict; at least eight major Northeastern railroads collapsed into helpless bankruptcy. Management blamed the senseless labor union work rules. The unions blamed incompetent management. As is usually the case, there's one lesson here for investors and quite a different one for reformers. All of the debaters need to reflect that possibly the collapse of the railroads was caused by attempting to create institutions which were bigger than they would need to be, fifty years later. Unless a way is provided for them to shrink, some form of shark will eventually eat them alive.

I am greatly indebted to a senior partner of one of Philadelphia's great law firms for insight into the decline of the railroad industry in Philadelphia, which took place during thirteen years of his active law practice on behalf of one of the bankrupt railroads. The insights are his, the opinions are mine.

|

| Interstate Commerce Commission Act of 1887 |

A railroad is inherently a monopoly. At first, that isn't obvious, as the railroads snake around to service potential customers. But it soon becomes apparent that it is generally easier to move a factory to an established rail head than to move an established railroad to the factory. Customers who doubt this soon find themselves less competitive than the competitors who recognize facts and respond to them. The location of rivers and raw materials make a difference, quite often enough to move the railroad; but when the railroad moves, it is only a matter of time before the mighty factory has to consider doing the same. That process tends to force everybody to greater efficiency, but it inconveniences many people, who appeal to their unions, who appeal to their politicians. This is a short summary of the origins of the Interstate Commerce Commission Act of 1887, which set the pattern for most later regulation of interstate commerce. The ICC Act, regulating and constraining the activities of railroads, was made law only a decade or so after the transcontinental railroads came into being. Since this had previously been an era of notoriously brutal clashes between the Reading Railroad and the Mollie Maguires, the entire regulatory process has been conducted like a cartoon of that remorseless struggle between one particularly fabled Irish Railroad President and one equally fabled Irish Railroad Union of song and story. The ultimately tragic end of the railroads was declared official by the Railroad Reorganization Act of 1973, which consolidated the freight business into a government-owned company called Conrail. For thirty years before the final demise, just about every president of just about every railroad -- was a lawyer. Others could run the engineering and the finance; in this business, survival itself depended on relations with government.

This description, while accurate in a way, misses a central point: what happens to an industry which was regulated and unionized as a monopoly -- when it develops competition and is no longer a monopoly? It badly needs to downsize, to reduce the overhead which comes from overcapacity, but the unions resist. Unless a way to reduce costs can be found, the company has put its foot on the down-escalator. The stock-market price declines as the profits erode, so borrowing becomes more expensive; the bond markets will sit in judgment on the outcome. A desperate management turns to technology and automation to improve productivity enough to compensate for the bulging overhead; but when improved technology makes even more employees redundant, the union balks and the increasingly obsolete regulations assist them. Competition from the highways and airlines is not going to relent, the unions feel they cannot or need not compromise, and sometimes will not permit productivity improvements. To the extent a company in that situation cannot reduce costs without reducing employment, it is very likely doomed. As the laws are now structured, the only escape is through bankruptcy. A nation's inability to stop this sort of corrosive cycle is one of the main reasons that typical American corporations seldom survive longer than a century. In the opinion of the constructive destruction theorists, that is a good thing for the nation. But it is a painful way to progress, and one does have to hope that a better way can someday be found.

For railroads, the main destructive force of federal regulation grew out of the rather rapid discovery that congressmen would demand a railroad in every state. While it may be hard to imagine a state that could survive the Industrial Revolution without at least one railroad, that wasn't necessarily imperative when new states were created and the land was cheap. And then if the Senate could require at least one railroad, it could also require stops and stations for every hamlet regardless of rational economics. And, if someone got struck by a passing train, it was hard to resist the demand for bridges over the tracks or tunnels under them. if some local developer wanted a grain elevator, the Senator was glad to make one mandatory. In their first fifty years when rail traffic was booming, railroad management was happy to comply. Everybody wanted to see the business get bigger. After 1920, however, the highways were starting to gain on the railroads; it was time to start being cautious. There began to be signs that requiring such excesses as five trainmen for every freight train, limiting the distance they could travel without a replacement, demanding "decent" wages, however, that might be defined, and a whole host of other costly impositions on the railroad -- were soon going to be things the railroads could no longer afford. In one way of looking at it, there was not even a need to be clairvoyant. Railroads were a century old in 1930; it was time to invest in something else. And by the way, it was probably time to look for another line of work.

It is common to hear that railroaders failed to notice they were in the transportation business, not merely the railroad business. That seems too easy to say; they were already in three distinct industries, freight, commuter rail, and long-distance rail. All three divisions were once profitable. The automobile first threatened the commuter rail lines, but then the airlines threatened the long-distance passenger business. And then the freight business was parasitized by the rest of the railroad industries. When too many people climbed into the lifeboat of profitable bulk cargo, it too collapsed from overload and nothing would rescue the whole rail industry except bankruptcy. It now needed suspension of government regulation and union contracts in order to merge, split, reorganize and introduce fifty years of accumulated but stalled productivity enhancements. Only bankruptcy would provide a way to keep the railroads limping along while drastic things were being done to them. Meanwhile, it was business as usual on the rhetoric battlefield; class warfare was never far from the bargaining table.

At this point in the analysis, my lawyer friend paused. In his opinion, the demise of the rail industry was not the main cause of the industrial decline of Philadelphia. The most important labor union struggle, in his opinion, resulted from the far more destructive behavior of the longshoremen's union, because ocean ships can quite easily move to another city where they are better treated; union intransigence very quickly destroys an international port. And to be fair, it isn't just unions that are tempted to treat foreigners badly. Almost all sovereign states have a history of taking what they can from non-citizens in their harbors; in America's case, there was a time when piracy was quite a respectable trade, conducted under the name of privateering. In the long run, exploiting foreign traders is self-defeating, but the temptation to exploit is always there. When intransigence gets out of hand, particularly when it is amplified by religious or class warfare, local poverty becomes quickly evident in maritime trade. Railroads just take a little longer to reach the same point.

Cleaning Up The Railroad Mess 1974

|

| Amtrak, 1971 |

By 1971, it was pretty clear the railroads in the Northeastern quadrant of America were relentlessly losing money and would soon collapse. Bankruptcy provided the only legal method for breaking the burdensome union contracts and huge legal tangles of rationalizing eight Northeastern systems, themselves the product of dozens of earlier mergers. At least in that sense, bankruptcy was a godsend. Getting down to serious reconstruction in 1971, the first step in cleaning things up was to strip off passenger business from the basically profitable freight business. The urban commuter business, hampered by local politics and facing overwhelming automobile competition, was probably the worst burden to profitability, but the decision was made to leave that to regional negotiations. A national long distance passenger system, Amtrak, would service everybody in one nationally subsidized network, with efficiency actually enhanced by national seamlessness. In a few areas like the Northeast corridor and California, long-distance passenger travel was actually still profitable.

Commuter systems, however, had grown up as local creations, differing greatly in local design and importance, and subsidy from the local population. They connected urban regions with suburban ones, and these two regions were often in uncertain economic (hence political) conflict with each other. Such loss-producing operations urgently needed to be stripped off from freight service, but here it seemed expedient to let each region of the country negotiate particularities, with many variations related to local issues. In particular, spreading the source of subsidy was a delicate political problem. If Philadelphia's SEPTA (South Eastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority) is typical, these local arrangements needed to be more generous to the unions than national opinion would permit; the rest of the country, viewing them at a distance, effectively told the big eastern cities to subsidize unions if they wished, but rural regions would have no part of it. National division of opinion on this issue effectively matches the boundaries of the "Rust Belt". It is debatable how seriously commuter subsidy, net of intangible advantages, still represents an economic drag on each metropolitan economy today; but it is certainly some kind of a drag, with numbers that appear rather large. Meanwhile, public sympathy is steadily drifting away from the unions; the Rust Belt is slowly migrating from liberal-leaning toward undecided.

Long distance passenger traffic was another matter; by insisting on railroads to nowhere, rural America shared equal guilt. Amtrak loses money, lots of it, but with generous subsidies, it has steadily improved service and equipment, usually sufficient to get past annual Congressional complaint sessions. Because of political log-rolling, Amtrak's separation from freight business is not entirely clean. It's responsible for servicing the pensions of all railroad employees, not just passenger employees, for example. Since pension funding delays its true cost for many years, the public is only recently becoming upset about this; the matter may arise again.

Meanwhile, it soon became clear that even freight service was going to sink in spite of jettisoning passenger businesses; this alone was not enough. Even setting profitability aside, there is no economical substitute for rail transport of bulk cargo like coal, oil, wheat, and ore, so interruption of national freight service would be an unimaginable disaster. All eight northeastern railroads were facing certain bankruptcy, which at least had the advantage of permitting courts to break union contracts; but one-quarter of the network could not be closed without closing freight service everywhere. The unions protested their rules were only responsible for minor costs compared with management incompetence, but the blame game was now irrelevant, bankruptcy was inevitable. Strangely, the average American had little idea of the full seriousness of this impending calamity, but the necessary legislation to create Conrail, a nationalized and subsidized Northeastern freight railroad, was cobbled together in the Regional Rail Reorganization Act of 1973. The law mostly restated agreements which had been forged during years of acrimonious negotiation between the parties. Not everyone agreed with everything, however, and a Supreme Court appeal was certain to intervene before the decisions could be final. The trustees of the Penn Central were most resistant to the terms. Investors universally regarded the outlook for a successful outcome as dismal.

|

| Conrail, 1974 |

Essentially, the transaction was to trade Conrail stock for the debt represented by bondholders of the bankrupt railroads; a swap of equity for debt. Hidden in these bankruptcy proceedings was the elimination of many of the union rules that had been so burdensome. For consolation, the unions got a promise of jobs for at least some of their members, and the satisfaction of gloating that the bondholders ("speculators") had been stripped. The bondholders wanted the Tucker Act applied, which is to say the right to sue the U.S. Government later if the true value of the stock had been seriously misjudged. The situation was very bleak. Conrail probably couldn't survive, and its stock would probably prove to be worthless. The Penn Central trustees were particularly dismayed at the possibility that there would be continuing losses after the settlement ("erosion"), which Penn Central bondholders would be forced to cover by further reducing their share of the already miserable residuals. For Congress to force bondholders into such coerced backing of a venture they definitely felt was doomed, amounted to a government seizure of their property without just recompense. It would thus be a violation of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution which contains a clause prohibiting what are known as "private takings". Meanwhile, the country was approaching an economic train wreck.

The Supreme Court had sympathy for Penn Central's argument and did find that a Tucker appeal should be available, a second bite at the apple, so to speak. Largely unspoken was the recognition that some weakening of union power was essential for even a hope of survival of the freight industry; so some conflicting language in the 1973 Act about Tucker appeals was -- sort of ignored. But later events showed the union work rules really had been critical to getting the railroads into the mess, and so successful agreements were reached at this moment of despair which never would have been agreed to if the true facts had been predicted. Railroad management, of course, contended that the work rules had been crippling them. But that appeared to be self-serving and the stock market largely ignored it.

But some remarkable men were put in charge of Conrail. They moved with remarkable speed to cut the size of train crews and otherwise remove a century of make-work rules. The quantity of freight cargo in 2010 is the same as that moved in 1974, but the workforce is reduced by 75%. Conrail became profitable, further mergers of national freight lines were negotiated, and it turns out that if someone had forced you to accept some Conrail stock in return for near-worthless bonds, you would have been a very lucky person.

Warnings of Impending Trouble for the PRR

|

| Pennsylvania Railroad |

The success of an excellent book, The Wreck of the Penn Central, has stamped the decline of the railroad industry with the problems of the merger of the New York Central and Pennsylvania railroads. There definitely was mismanagement of that merger, which quite possibly should never have occurred, and unions surely did contribute to excessive costs of running the merged lines. Government regulation was definitely slanted toward maintaining uneconomic railroad capacity for political reasons and tangled the struggling corporations in mountains of red tape which prevented timely responses to problems. And the tax-subsidized highways and airlines tilted the balance against the fair competition with a railroad industry which had long been unaccustomed to the competition. All of these difficulties prevented the railroads from meeting new challenges, and like wolves around a wounded caribou brought it to the ground.

|

| Smoke Signals |

But there is a larger picture explaining the toppling of the railroads, particularly when the causes of Philadelphia's industrial decline are the focus of examination. The whole fabric of Philadelphia's economy was interwoven with the national dominance of the Pennsylvania Rail Road, which was in turn intertwined with the national importance of coal and steel production, a creation in the 19th Century of J. Edgar Thomson. It was not one heavy industry which disappeared, it was three of them. It was not just Philadelphia which faded, it was the whole "Rust Belt" from Philadelphia to St. Louis. Baltimore and Cleveland declined even more than Philadelphia, for example. At the end of World War II, this was the only region of heavy industry still standing in the whole world; for a while, its uncompetitive profits were astounding. Unionized labor made amazing gains in wages and power, management grew fat and slack; the government made sure it was so, but competitive industries had an easy time lobbying for that outcome. As late as 1968, PRR shares which were to fall to $15 within ten years were selling for $80, and an old joke was current. A mythically representative Philadelphia father was said to advise his daughters, "Sell your body if you must, but never, never, sell your Pennsy stock." All of this public pressure combined to encourage unions and government to force management to take the easy way out huge deferred maintenance during ten years of depression and five more years of war had built up. And meanwhile, the biggest deferred problem of all was allowed to build up. Every congressman for decades had demanded unprofitable rail service for his district, insisting the trains make too many unprofitable stops along the way, and at night, and on weekends. Every business must adjust capacity to changing customer demands, that's just business, but an inability to adjust capacity to changing circumstances is what's fatal.

Creating and Wrecking the Penn Central

|

| Penn Central |

In 1957 President James M. Symes of the Pennsylvania Railroad proposed a merger with the New York Central Railroad. If politics and unions prevented modern railroads from increasing productivity by eliminating internal waste, perhaps a merger would create the potential for pruning the consequent duplications of service. Unfortunately, the merger couldn't take place without governmental permissions, so the same combination of unions and government blocked a merger as blocked revisions of union work rules and political insistence on unprofitable services. That blockade worked and it didn't work. Internal deal-making in the government finally maneuvered it into happening, but only after eleven years. It was probably the eleven years of worsening delay which made the merger collapse after two years of existence. The Penn Central really needed twenty years of good luck to be certain of success, but with twelve years it might at least have had a chance.

It was hard enough to get the two boards of directors to agree on a merger; the New York Central was in such bad shape Pennsylvania would surely be the dominant internal survivor. The real battle, however, was the political one of securing government permission to merge. It was quickly apparent that Democrats were opposed, Republicans in favor. Democratic Governor Lawrence and Democratic Mayor James J. Tate of Philadelphia were both opposed, and it was easy to see the union influence on their minds. When Democratic President John Kennedy revealed his opposition, it was clear where the party stood, and negotiations were almost dropped after two years. The assassination of President Kennedy brought Lyndon B. Johnson into the matter, and the Pennsylvania RR soon appointed a close friend of his, Stuart Thomas Saunders as their CEO. Saunders was a real railroader, having worked for twelve years for the Norfolk and Southern, but he was mainly a politician in several ways. On arriving in Philadelphia, he was immediately welcomed into prestigious Philadelphia social circles and made rather a splash. In time, President LBJ appointed former Governor Lawrence to some advisory boards and he switched his position on the Penn Central merger. Soon, Mayor Tate relaxed his opposition, and it was all done. The Republicans were always in favor, Governor Scranton reversed the gubernatorial position, and now the Democrats were top to bottom in favor. Unfortunately, Milton J. Shapp was not in favor. Mr. Shapp had sold his Community Antenna Television system for $10 million and seemed anxious to get involved in politics. Apparently sensing an issue which might put him in charge of Pennsylvania Democratic politics, he launched a loud and bitter crusade against the merger. It is not publicly known whether the Johnson administration attempted to dissuade him, but it would be surprising if they hadn't. At this point, Walter Annenberg the owner of the Philadelphia Inquirer and the largest stockholder of the PRR launched a pro-merger and anti-Shapp campaign which grew increasingly bitter as Sharp stood for election as Governor and was elected in 1970. Under the circumstances, the PRR was bound to be pleased with Annenberg, and Saunders launched a campaign to make him socially acceptable in the circles where he was now a great lion. Annenberg's father had gone to prison, and the largest profit center in the news empire was the horse-racing form, although TV Guide eventually surpassed it, so his social rehabilitation was surely welcome. Eventually, he was appointed Ambassador to England. After eleven years of hard work and devious tactics, the Penn Central merger came into effect in 1968. It lasted only two-plus years.