4 Volumes

BANKS REDEFINED

American banking was invented in Philadelphia. The banking center of America has moved away and changed in extraordinary ways but the foundations remain.

Money

New volume 2012-07-04 13:46:41 description

Second Edition, Greater Savings.

The book, Health Savings Account: Planning for Prosperity is here revised, making N-HSA a completed intermediate step. Whether to go faster to Retired Life is left undecided until it becomes clearer what reception earlier steps receive. There is a difficult transition ahead of any of these proposals. On the other hand, transition must be accomplished, so Congress may prefer more speculation about destination.

A New Era in Politics: Clinton, Obama, and Trump

New forms of communication made the party system largely obsolete.

Financial Planning for a Long Retirement

How should individual investors ensure they have enough money for retirement?

Such a person is often a professional or entrepreneur who has worked to accumulate the wealth. Legions of "advisors"line up to take this money and manage it or else to sell "products" that promise to solve some problem or other. Without this background, extra savings will be needed, to buy advice. And advice is not invariably reliable.

A person who has created his/her career and its wealth from scratch, can likely manage investments themselves, or at least supervise the process from a position of strength from observation. Reliable advice is not always cheap.

This collection of articles explains to the individual investor how to take control of their wealth. They may eventually decide to look for help from an advisor but they will retain control of their assets and they will know what to do.

Financial Planning videos on YouTube

Retirement Planning

Insurance

Special Education, Special Problems

|

| School Bus |

President John Kennedy's sister was mentally retarded; he is given credit for immense transformation of American attitudes about the topic. Until his presidency, mental retardation was viewed as a shame to be hidden, kept in the closet. Institutions to house them were underfunded and located in far remote corners of a state. Out of mind. And while it goes too far to say there is no shame and no underfunding today, we have gone a long way, with new laws forcing states to treat these citizens with more official respect, and new social attitudes to treat them with more actual respect. We may not have reached perfection, but we have gone as fast as any nation could be reasonably expected to go.

However, any social revolution has unintended consequences; this one has big ones, surfacing unexpectedly in the public school system. For example, the king-hating founding fathers were very resistant to top-down government, so federal powers were strongly limited. So, although John Kennedy can be admired for leadership, the federal government which he controlled only contributes about 6% of the cost of what it has ordered the schools to do, and the rest of the cost is divided roughly equally between state and municipal governments. As the cost steadily grows, special education has become a poster child for "unfunded mandates", increasingly annoying to the governments who did not participate in the original decision. We seem to be waking up to this dilemma just at a time when the federal government is encountering strong resistance to further spending of any sort. The states and municipal governments have always been forced to live within their annual budgets, unable to print money, hence unable to borrow without limit. As Robert Rubin said to Bill Clinton when he proposed some massive spending, "The bond market won't let you."

The cost of bringing mentally handicapped individuals back into the community is steadily growing, in the face of a dawning recognition that we are talking about 8% of the population. Take a random twelve school children, and one of them will be mentally handicapped to the point where future employability is in question; that's what 8% means. Since they are handicapped, they consume 13% of the average school budget and growing. The degree of impairment varies, with the worst cases really representing medical problems rather than educational ones. Small wonder there is friction between the Departments of Education and the Medicaid Programs, multiplying by two the frictions between federal, state and municipal governments into six little civil wars, times fifty. An occasional case is so severe that its extreme costs are able to upset a small school budget entirely by itself, tending to convert the poor subject into a political hot potato, regularly described by everybody as someone else's responsibility. There are 9 million of these individuals in public schools, 90,000 in private schools. They consume as much as 20% of some public school district budgets.

All taxes, especially new ones, are bitterly resisted in a recession. Unfortunately, the school budgets are put under pressure everywhere by a growing recognition that our economic survival in a globalized economy depends on getting nearly everybody into college. Nearly everybody wants more education money to be devoted to the college-bound children at a time when there is less of it; devoting 13% of that strained budget to children with limited prospects of even supporting themselves, comes as a shock. Recognizing these facts, the parents of such handicapped children redouble their frenzy to do for them what they can, while the parents are still alive to do it. It's a tough situation because a simultaneous focus on specialized treatment for both the gifted and the handicapped is irreconcilably in conflict with the goal of integrating the two into a diverse and harmonious school community, with equal justice to all.

As school budgets thus get increasingly close scrutiny by anxious taxpayers, handicapped children come under pressure from a different direction. It seems to be a national fact that slightly more than half of the employees of almost any school system are non-teaching staff. Without any further detail, most parents anxious about college preparation are tempted to conclude that teaching is the only thing schools are meant to do. And a few parents who are trained in management will voice the adage that "when you cut, the first place to cut is ADMIN." Since educating mentally handicapped children requires more staff who are not exactly academic teachers, this is one place the two competing parent aspirations come to the surface.

Unfortunately, the larger problem is worse than that. When the valedictorian graduates, the hometown municipal government is rid of his costs. But when a handicapped person gets as far in the school system as abilities will permit, there is still a potential of state dependence for the rest of a very long life. The child inevitably outlives the parents, the full costs finally emerge. We have dismantled the state homes for the handicapped, integrating the handicapped into the community. But when the parents are gone, we see how little help the community is really prepared or able, to give.

Disappearing Stock Power

The Right Angle Club of Philadelphia recently heard two presentations on newer investment strategies, one by our member on hedge funds and private equity, and a week later by his guest from Black Rock, on ETF funds. For the purpose of this review, both presentations ultimately got around to the same issue.

In the case of private equity, the investor purchases a share of aggregated profits from a company in the business of buying a substantial or controlling interest in corporations, usually underpriced or underperforming ones. And then, the private equity fund attempts either to fix up the company and sell it or fix it up and hold it indefinitely. Whether or not he achieves a profit, the individual investor in the fund loses the opportunity to vote the shares, or has it offered in such an awkward way the opportunity is meaningless.

|

| Hedge Fund |

A hedge fund similarly buys and sells stock on its own account, employing the money of investors, and generally adding huge amounts of borrowed debt. In this case, the stock is often held for such short times that voting rights are lost in the registration requirements. Taken as a whole, however, the issue is substantial, since it is reported that 70% of recent transactions have been conducted by unattended computers operating by pre-arranged contingency instructions, often responding in fractions of a second. While the resulting immobilization of voting rights is substantial, the main problem with hedge funds has been the way very small profits have been magnified by staggering amounts of borrowing, potentially causing very large losses if the transaction system is slowed for whatever reason. While hedge funds did perform well during the 2007-2009 crash, it will be 2012 before the incredible volume of transactions can be analyzed to see how close we were to disaster. There is definitely a risk in doing nothing, but probably less than the risk of ill-informed legislation making matters worse in some way.

In the case of ETF, the operator or "manufacturer" of the fund attempts to buy blocks of stock in all or representative samples of the companies listed on some index, weighted in proportion to their weight in the index. The intent is never to sell that stock, merely evaluating the fund price and its dividends as a mathematical exercise, and repurchasing or reselling the calculated bundle to other investors, but never disturbing the contents of the bundle unless the index changes its composition.

In all third-party investing cases except hedge funds, the advantage is that reduced tax and transaction activity saves costs, and avoiding internal selling of stock means essentially no taxes are payable until the investor ultimately sells the fund. The managers of funds maintain that these tax and overhead savings completely compensate for losing whatever opportunities for profit would come along and be exploited by expensive "active" managing of the funds. (Some investment funds employ more Ph.D.'s than any American University does.) Even if the performance turns out to be somewhat lower, there is a safety factor of exactly matching the averages, and thus agreeing to surrender the opportunity to join half of the universe of investors in beating the average, in order to avoid joining the other half of investors in doing worse. Furthermore, distributing the investment over a large group of corporations confers diversification, and thus surrendering the chance of a windfall profit in return for avoiding the occasional disastrous loss. In a sense, the fund investor no longer hopes for a company to do well, he hopes for the whole nation to do well. Summarizing the details, these funds provide safety of diversification and reduction of turnover costs, in return for assured but marginal above-average performance. Since this outcome is so greatly superior to the actual experience of non-professional investors overall, it is highly attractive to many investors and should be attractive to more of them.

In addition to these common features, the hedge funds and private equity expose the investor to the risks and rewards of choosing a skillful manager, who may or may not choose the portfolio wisely, and who may or may not use leverage wisely. The choice of portfolio companies, on average, justify a greater degree of borrowing as their quality improves, and all investment borrowing involves a risk that interest rates may go up for reasons unrelated to the investment. In the recent debacle, hedge funds did comparatively well, but nevertheless, there are times when it is unwise to borrow against even the safest securities. And finally, because of the risk of stock market raids by outsiders, hedge funds are quite secretive about their portfolio contents and force the investor to "lock in" his illiquid investment for several years at a time.

There remains one characteristic of both funds, and for that matter mutual funds, annuities, life insurance and all other forms of aggregated investing through a third party. The third party retains the right to vote the shares, admittedly with some little-used and generally unworkable opportunities for investors to request their own proxies. Such third parties almost always vote the shares in their custody in favor of management. There are occasional exceptions, as when union-managed funds will vote their shares in a political manner, or as when some mutual funds attempt to obtain pension fund business in return for cooperation on selected proxies, or in one legendary story the custodian was instructed: "Always vote AGAINST any management proposal." But these are presently exceptional situations. In the vast majority of cases, the proxy votes effectively disappear, and control of the companies in the portfolio gradually gravitates into the hands of those few stockholders who retain direct ownership and take the trouble to vote it. In fact, it is increasingly the case that the most effective way to frustrate a management proposal is not to vote against it, but to abstain entirely, in the hope that a quorum cannot be assembled.

Another popular movement augments this unfortunate situation. Increasingly, it is urged that top management be paid substantial parts of its reimbursement by stock in the company or options on it. The argument is that it is important to align the motives of top management with the rest of the stockholders. Reflecting concern about some recent events, such stock is or should be forced to bear the covenant that it may not be voted in a stock take-over by an outside raider, to frustrate the commonly used inducement to the manager to sell out his stockholders in a merger. Even when this particular contingency has been foreseen and prevented, the effect of increasing the shares in the hand of management and decreasing the voting shares in the hand of the outside public by freezing them in third-party funds -- soon puts the idea in the heads of managers that they own the company. The recent public indignation about inordinately high salaries for top management, can in large part be traced to the plain fact that voting control of the companies is visibly shifting into the hands of the people who receive those salaries.

Force Justifying the Use of Force

Once a group of people reaches an agreement about governance (or, become convinced that certain specified varieties of force will put an end to unspecified force), the stage is set to impose conformity upon those who prefer persuasion. The justification is almost always the same: force is offered to justify making the use of force unnecessary. Except for the indoctrination of children, the prior use of force is just about the only justification for forcible responses. There's a Quaker sound to that because it introduces an unproven suggestion that all force might begin with the training of children.

Even an approximation of that suggestion seems to fit the facts of fierce tribes like the Vikings and the Romans permanently switching to notoriously pacifist ones and goes on to include others like the Tibetans and the Japanese, and Germans. Unfortunately, it must also mention the early Quakers themselves, who have a history of cavalry troops in the English Civil War, Confederate sympathies in the American Civil War, and conflicted allegiances in the "Good War", World War II. The history may not be an undiluted one, but contains numerous threads of many switches in nature from a revulsion against violence, or reversion to it, nevertheless too rapid to seem plausible as either mutation (on one hand) or pure switches of reasoning, on the other. Conversion by childhood observation and rebellion, at least, seem more plausible mass-change agents.

Basic Lifetime Health Care?

Lifetimes are divided into sequential episodes for various practical reasons, and in the past fifty years, a brand-new episode known as retirement has even been added to the end of the sequence. We started with two thirty-year periods, childhood, and adulthood. For its own purposes, the medical payment system stretched to three segments within a 90-year lifetime, and then for practical purposes, a five-segment one: childbirth, childhood, education, employment, and retirement. The employer community pioneered this American hybrid, but almost all other national systems are government-dominated, so the American system segmented slightly to accommodate the reality that two employers (the parents and the child) must be recognized. The new retirement era tends to unite retirement with the government as becoming the organization which pays the bills tending to dominate the choice of payment. It probably does not overstate matters to say that recent immigrants favor a unified lifetime government system, while employers are reluctant to give up control for fear government control will spread out through the opening. The fact that medical revenue at any age originates in the employment interval lends plausibility to this attitude. Comparison of the quality of the two existing approaches does not seem to disqualify either employer-based or single-payer (lifetime national governmental), although the Constitution seems to favor individual 50-state hybrids.

What is gradually shifting during the past century is the inclusiveness of the sponsor groups, retirees enlarging at the expense of the employed. These groups see themselves becoming potential beneficiaries but changing at different rates and with different costs. Shifting costs are befuddlement, but it seems safe to predict that costs will ultimately fall to slightly more than the first year of life and the last year of life. Before that point is reached, we will probably experience a rising period of development costs in the middle. Actuaries calculate an average present lifetime cost of $300,000, net of inflation, around which actual costs will fluctuate. Taking a wild guess that first and last year will eventually settle down to $100,000 per average lifetime, or perhaps $150,000 including terminal care, the elements of the first-and-last year of life insurance should be calculable, and the premium approximated and re-adjusted annually on a current-cost basis. In the meantime, healthcare costs can be monitored by big-data methods. No one would expect such data to be precise at first, but a ten-year probationary period should suffice to arrive at commercially workable net costs for all citizens for the two universal costs for everyone -- birth and death. There will be universal outcries that other costs will be neglected, underestimated or misjudged, but a workable and basic universal system can nevertheless be established, and the intervening other medical costs managed in the conventional political way.

.

Innate Longevity

Someone must have made a study of longevity because the externals give every sign of genetic control. Pets and domestic animals vary widely in their typical lifespans from a few hours to more than a century, but each species seems to have characteristic longevity, roughly in proportion to its typical overall size. Within a certain limit, each species of a pet seems to live about the same length of time, suggesting some variety of genetic control. The human species is of most concern to longevity in the life insurance industry, and it is commonly noticed that very few people live beyond the age of 110, except in Biblical accounts of doubtful accuracy. Until recently, the average human longevity was what it was, but if we are to base insurance on this topic, it will soon enough be important to know how difficult it would be to lengthen it artificially. Right now, it appears to be next to impossible, but the same question got a different answer a century ago, and the answer has approximately doubled.

Bear in mind that the purpose of tinkering with longevity is to affect the cost of the insurance, and there are two natural forces at work == inflation and compound interest. They work in opposite directions; inflation reduces the available funds over time while compounding increases it. Since inflation is under human control whereas compounding is purely mathematics, only inflation is likely to be changed, while compounding is likely to increase the size of the principal. There are limits, but at a duration of 90 or 100 years, the net of inflation and compounding is apt to improve the size of the reserves. In any event, only inflation needs to be monitored in order to make adjustments, and after fifty or so years, it would have required pretty drastic changes to put similar life insurance started by President Hoover at mathematical risk today.

Since there is thus no need to worry about the finances of this system back to some Roman Emperor, approximately half of the permanent healthcare cost can be predicted (one-off forever) and some clever actuary could thus calculate what it would amount to, per year.

Stretching Out Your Retirement Savings

|

| Benjamin Franklin |

Benjamin Franklin was able to retire from the printing business at the age of 42. His partners bought him out in eighteen yearly installments. In the Eighteenth century, it was unusual to live past the age of 60, so Ben felt pretty well fixed. Unfortunately for this planning, he lived to be 82, so when he did reach the age of 60 he was forced to look around for postmasterships and other ways to survive, for what proved to be 22 more years.

This is the other side of a coin; on one side is written, "Protect your family in case you die young". On the opposite side is written, "Be careful not to outlive your savings", relying on the old Quaker maxim that the best way to have enough--is to have a little too much. For centuries, life insurance was sold to people who mainly feared the first, commonest, possibility, but never completely addressed the opposite contingency, which was growing steadily commoner. Annuity insurance ordinarily is sold for a fixed number of years, so insurance commissioners ordinarily require what is most probable. Unfortunately, this response shifts the risk of guessing wrong onto the subscribers' shoulders. Since science has unexpectedly lengthened average life expectancy (by thirty years since 1900, or by five years in the last ten), experience rather like Ben Franklin's has become a commonplace, but rather poor business judgment. The business remains solvent only as long as the decision to drop the policy is later than the life expectancy.

|

| Retirement Saving Debt |

There may exist insurance policies to address this issue, but few companies offer it. We will briefly describe this sort of policy, in case it becomes more widely available, but it is primarily described here to illustrate the issues to consider. If you can get it for a reasonable price, or if you can get it at all, the outline of the policy would be to set a premium and promise to pay 6% for the rest of your life. Underneath the promise is the reality of paying 6% for eighteen years as a non-taxable return of principal. Following that, you don't need to get a postmastership, you are paid a taxable 6% until you die. Presumably, the insurance company has actuaries to help with the math, so the company makes money if you live less than your life expectancy, and loses money if you live longer. If life expectancy suddenly extends much longer (let's imagine a cure for cancer appears), the insurance company is going to go broke. That's why insurance commissioners are uncomfortable with the concept, even though it is obvious how desirable it might be. So that's why annuity insurance typically states a fixed number of guaranteed years and expects the subscriber to shoulder outlier risk.

Any insurance has an administrative cost, so everyone must consider some non-insurance solution to the whole problem. Therefore, we propose you re-examine the old saw about "never dip into principal". If you don't have enough money, you can't do very much except depending on the government, your family, or your fairy godmother to help you out, although it must be obvious that all Americans would be wise to consider retiring five or ten years later than they hoped. Very likely, the government is going to have a difficult time sustaining even the present tax exemption of retirement funds, medical insurance, and social security. Those are called entitlements, but if the government eventually can't afford them, it won't matter what you call them. If entitlements keep getting extended, we can expect our nation to resemble the ancient Chinese and Indian nations -- able to build palaces in their golden era, but eventually crumbling into a gigantic slum in centuries afterward. So please, if you are able to do it, try to keep gainfully employed for a few extra years. If you do it (and some people can't) you may be able to realize the American Dream.

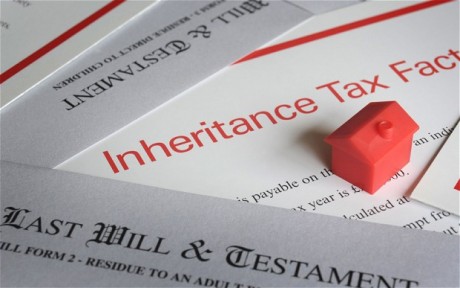

|

| Inheritance Tax |

The traditional American dream was to accumulate enough money to live off the income from it indefinitely, never touching principal, and then exposing the principal to destructive estate taxes after you finally die. Unless you are unusually wealthy, there isn't much left for the next generation after estate and inheritance taxes and expenses. It's a little inefficient to accumulate more than you actually need, but the government gravitates toward the least painful methods of collecting taxes. By confiscating this safety surplus, however, it declares that "Every ship (generation) must sail on its own bottom." And therefore it must acknowledge responsibility for what inheritances ordinarily pay for, like charity and good works. But there remains a quirk to this.

If Ben Franklin's partners had arranged to invest the money until he needed it, they could at least have afforded to finance two or three extra years. After inflation and expenses have eaten away at your retirement income, your principal may not generate enough income to last forever, but it is still big enough to pay for several years of retirement, which may in fact be longer than you are destined to live. Remember two things: 1) a principal sum, big enough to support you indefinitely, must be roughly eighteen times your yearly expenses. If it is only big enough to support you for fifteen years, it will seem too small until you realize you are probably actually going to live, say, five years. And 2) as far as leaving an inheritance to your children is concerned, there is a realistic probability that the government will consume most of the estate before it ever gets to the kids. These fundamental truths are presently obscured by the Federal Reserve artificially forcing interest rates to less than 1%. But if you can just hold out for a few years, it seems entirely likely that interest rates will return to 6% (meaning your principal will once again produce eighteen equal installments). But such a return of interest rates to normal levels will force the government to pay a comparable amount as interest on its bond debts (meaning it will get hungrier to escalate your estate taxes.) This isn't nearly as satisfactory a solution to the life expectancy quandary as retiring five years later than you once expected to, but you can't say we didn't warn you.

And as for what happened to Ben Franklin, you can read his will. He died a very rich man as a result of shrewd investments, later in his life. Ben left eight or nine houses, several thousand acres in several states, a gold-handled cane, and a portrait of the King of France surrounded by hundreds of diamonds. But it would not seem wise for the rest of us to count on accumulating that much new wealth, after attaining the age of sixty. The way things are going, once you attain your life expectancy, everyone should have some non-insurance plan for supporting himself for two or three extra years.

New York Times: Splendid Idea for Old Age

The New York Times devoted an entire issue of its Sunday News of the Week in Review on April 7, 2019, to variations of the theme that "Elderly People Have Surplus Spare Time." Although I have several personal connections with the editors of the Times by marriage, and other connections to the newspaper through Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons, I seldom agree with its New Yorkerish hunt for evil from greedy enemies. But this particular attack struck me as right on the mark. Sympathy with downtrodden unions has led to commercial forces preferring fragile cheap products needing to be replaced when broken, discouraging home repairing and the ultimately of the population's ability to repair. At the same time, a lot of old folks have time on their hands and limited opportunities to supplement their retirement income, even ultimately leading to the disappearance of the needed skills to make simple repairs. The Times doesn't suggest the two unfortunate curable ends of the Industrial Revolution could cancel each other out, but it seems to me they might fit if coaxed.

Apple seems to be the biggest offender, substituting unnecessary cheap electrical connectors for successive versions of expensive machinery. When you need to replace a thousand-dollar computer for its broken ten-cent plastic connector, the commercial motive is obvious to the consumer, and pretty annoying, too. A broken plastic connector isn't worth its twenty-dollar markup, but the expensive computer would justify its connector markup, which ultimately becomes a one-dollar markup for a Chinese imitator. The situation in the computer industry was explained to me in person by Michael Dell. When he had his nineteenth birthday, his mother gave him an expensive IBM portable computer. He took it to his bedroom with a screwdriver and found that not a single component was actually manufactured by IBM. He wrote each individual manufacturer for prices and discovered he could make an imitation (but identical) computer, selling it profitably and ultimately driving IBM out of the portable computer business. Substituting Chinese names for Michael Dell you get quite a different story, which paints quite a different description, about excessive markups by greedy Americans. Nevertheless, the moral I draw is the ultimately self-defeating nature of excessive markups, for commercial unfair motives. Smaaart when you reveal them to friends, but unwise, in the long run.

But buried in all this petty maneuvering is a solid truth. We once had a population which took woodshop in the seventh grade and metal shop in the eighth. for boys. And the girls were learning how to cook and sew in separate rooms. This system needs a little updating, but the point is that these abbreviated courses were adequate to teach the essentials of home repairing to whole generations of the population. You wouldn't need to buck the unions, who proved able to destroy the whole vocational school system of fresh competitors, in order to restore simple home repair to the whole population. The old retired folk could repair the broken plastic widgets in their simple lives. The ladies could cook a little instead of continuing plastic-wrapped dinners they now have more than enough time to play around with. Hardware stores would reappear to satisfy the need for widgets. And the retirees wouldn/t need to sit around for lack of simple things to do. It's a brilliant idea, even if it did come from the New York Times.

Increased Potential for Retirement Villages

|

| Pennsylvania Hospital, Nation's First Hospital, 1751 |

Healthcare institutions may well have mission statements, but the main force visibly shaping hospital mission is third-party reimbursement. One must be sympathetic with institutions which really prefer their own mission to the pressures from third parties, particularly when the "second party" -- the patient -- also likes the original mission better. Teaching hospitals surely would prefer to concentrate on streamlining tertiary care, retirement villages on enriching the lives of elderly residents, etc. And they could probably make a better case for what they prefer than third-parties can. When one-size-fits-all health insurance is imposed on institutions which must survive by internal cost shifting therefore, insurance mandates invisibly prevail. It is not always strictly a matter of "Who pays the piper calls the tune", as it is "Who pays the most can run the place."

Considering these invisible forces of control at work, it seems highly desirable to search for situations in which the incentives of the third-party do not run parallel to the incentives of the provider community. In the case of government third-parties, the goals of the agency may not even be parallel to the will of Congress. The public clearly prefers to pay for private rooms and private duty nurses if it can afford to, but those are mainly relics of the past. Doctors used to work out of offices in their homes, but you seldom see that, now. There once were twenty hospitals in Philadelphia which were owned, paid for and operated by churches, but now at most, the church name is a relic on the front door surviving from a former era. If these changes were a response to public preference it would be another thing, but they are usually not even traceable to a written mandate which might be appealed. So it becomes all the harder to defy a mandate which grew out of the hospital's surmise as to what the third party would probably prefer. Perhaps some examples of social pressures at work would be useful.

It happens my own first office experience was in the home of an older doctor on vacation. The location of that family residence was a careful triangulation of convenience, expense, distance to the hospital, and the preferences of the patients. It was a grand experience to put aside the breakfast coffee, walk into the next room, and see the first patient of the day. Or to interrupt office hours for an emergency in the neighborhood for less than an hour and to have your excuses readily accepted by the waiting patients upon return. My colleagues had explained the financial advantages of sharing a roof and heating system with a tax-deductible business. But my accountant explained that the Internal Revenue Service didn't like offices in the house, and would surely audit any doctor silly if he persisted. So I spent fifty years in an office across the street from the hospital, commuting and seeing patients who had to commute to see me; the extra expenses of parking and the rest of that arrangement are easy to imagine. True, it was easier to visit the hospital patients, and nice to eat lunch with other doctors in the hospital cafeteria. But all of these decisions were not my own first choice. I never got a letter from the IRS or heard a murmur from them, but I always believed I was responding to their mandate. When an IRS agent finally wandered into my office as a patient, he admitted the IRS prejudice but said he believed it grew out of fear the business expenses reported would really be the expenses of a hobby, not a business.

A second relevant experience occurred when I was a resident physician. A staff physician at the hospital had a heart attack, and the Chief of Medicine asked me to take a few days off to tend to the problems in the stricken doctor's practice. His home and office were in the midst of a row-house district of town. When I arrived, the office was empty of patients, but the nurse was waiting with an umbrella. "Before we see the office patients, we must make rounds to see the bedridden patients at home." To my amazement, within a three-block radius of his office, there were nearly twenty patients in hospital beds at home. Some of them had oxygen tents, several of them had intravenous fluids dripping into their arms. The nurse told me that she drew blood for pickup by a laboratory and that with a little argument a portable x-ray machine could be brought to the home. At the foot of each bed was a hospital chart, all up-to-date with notes and reports. It might not be possible to run such a show in many other neighborhoods, but the city row house neighborhood was ideal. Or, not ideal perhaps, because there must have been many problems. But it was clear why Blue Cross had slow progress making sales to the people accustomed to this arrangement. And it even made clear why patients were content with open twenty-bed wards in a hospital, for at least ten years after Medicare would have gladly paid for a semi-private room. No private duty nurses, however, it might set an unwise example.

Two things are at work, here. Things happen to medical care which is undesirable, so someone needs to complain about them, and complainers must be provided with a place to appeal. The reverse is also true; good things which ought to happen, don't happen. So in addition to providing an appeals system, we somehow have to provide a wise and unbiased ombudsman to suggest what new initiatives ought to be undertaken. And the two functions, negative and positive, need to commune with each other. Parenthetically, since everybody gets involved in health care to some degree, adversary roles must be filled in this process, containing representatives of patients and also providers (both institutional and individual), as well as guardians of the purse. Since the process quickly becomes unwieldy, it needs to be associated with a special committee of Congress and needs to be able to summon both witnesses and experts. An annual convention in some pleasant spot might enhance the concept.

Institutions are another matter since quite often the personal opinions of the spokesman are constrained by the incentives of the institution. It must be made clear to them which opinion is desired.

Institutions choose their location for other considerations, chief among which is cheap land, but the location near public transportation is another factor. Whatever the thought process underlying it, nursing homes and retirement villages are almost always in the far suburbs. A related problem is a vexing difficulty for a center-city hospital to find a nearby nursing home for convalescents. These annoyances are protracted by the licensing rules in a round-about way. When a corporation is formed, typically a lawyer with a yellow pad asks two questions: "What are you going to name this organization?", and then, "What is its purpose?". Presumably, he then completes some forms and files the necessary applications. The stated purpose may well have other uses, but it defines the sort of license needed, and eventually either match or does not match the rules some third-party reimbursement agency has laid down for what sort of institution is eligible for reimbursement. After that, the system becomes much more rigid than it needs to be. As long as the institution remains defined as a hospital it will be paid by the third-party, and without that designation, it won't. Effectively, the state licensing board acquires the power to shut off the revenue of some institution which displeases it. But what displeases it (let's say, mice in the kitchen) usually bears a scant relationship to whether or not the institution is capable of performing additional tasks. It does not take long for these issues to get blurred and forgotten; the retirement village can't receive hospital reimbursement because it doesn't have a hospital license. A hospital license would permit it to do a lot of things it doesn't want to do. While the general idea is sound enough, the rigidity it imposes is excessive, particularly when you consider the penumbra of reluctance it provokes from employees. Obviously, the interpretations vary greatly between jurisdictions. It leads to hospitals which may perform heart transplantations but may not run a day-care center for the children of their employees.There are many simple solutions to this simple problem, but because so much of it is buried in-laws, it would probably require a special court to be appointed to oversee it. How busy that court would be would depend on how vigorously competitors would resist it, which would probably vary with the region.

In any event, Society has a legitimate interest in preserving the quality of care, but it does not fulfill that duty by transferring it to reimbursement agencies. During wars, surgery is satisfactorily performed in tents, for an extreme example of how expendable much oversight can be. Another principle would be to ease impediments to overlaps of functions between institutions, particularly including the backward sharing of component services and records toward the lower-level institution. Since such sharing is often observed to occur without objection within vertically integrated institutions, there is every indication it is both desirable and feasible between competitors.

Going much farther back to the town meeting form of oversight, the most radical departure from present custom would be to encourage a shift of the center of care from inpatient hospitals toward retirement villages. The simplest definition of the center of care would be the location of primary physician offices, and the most important step would be to discourage mandatory links between referring physicians and particular acute care hospitals. Doctors left to themselves will locate where the patients are, and increasingly it is possible to see a shift of patients requiring chronic disease management and terminal care into the retirement village. The tendency of doctors and laboratories to cluster around hospitals impedes this natural shifting together. If doctors shift their offices and are allowed a choice, laboratories and x-rays will soon follow them. Before Medicare, the center of care was found near the high-rent districts of cities. In London it was Harley Street, in Philadelphia it was Spruce Street. As reimbursement changed, it shifted toward the hospital campus, where the parking problem is also solved. Nowadays, early discharge and reimbursement shifts have made it unattractive for a primary care physician to visit his patients in the hospital, so hospitalist and emergency room specialties are flourishing, with computerization feebly bridging interruptions to the continuity of care. The primary care physician would find the retirement village solves the parking problem; pharmacies and laboratory pick-up are often already in place, and non-surgical specialists would soon follow primary care physicians. Patient transportation, at present crippled by expensive municipal monopolies, would be greatly eased by such shifts of medical interaction. The ultimate shift of the center of care would be for the more mobile younger population of suburbs to shift allegiances toward the retirement village location, a change mostly affecting pediatricians. It would take some time, and it would always be a partial migration. However, the infirmaries of retirement villages offer convenience and comfort near home.

The most effective force maintaining standards for this level of care, have no doubt of it, is the ease with which friends within the community drop in for visits. They have time for it, especially to and from the dining room, and all of them keep a watchful eye on how they would likely be treated there themselves when their turn comes. In retirement communities, client consensus is a powerful force. What is lacking is a willing sharing of reimbursement with acute care hospitals. Therefore, the idea of brief hospitalization followed by longer recovery near home is now only realistically available to the affluent. But their choices show the way, as they always did before third-party insurance dominated the scene. For a while, little children may think it is funny to get their shots at the old folks home, but they will soon get over it.

Critical Number for Retirement Planning

|

| Retirement Plan |

There is scarcely any need to list the uncertainties of planning for retirement. To make a precise number, you would have to know how long you expect to live, how much you need to spend, how much cash flow is assured, how much your stock portfolio will be worth, what the rate of inflation will be, and so forth, and so forth. When you get done listing all the things you have to know, the general tendency is to assume the task is impossible. It's hard, but it isn't impossible if you know a single number: the average growth rate you need to achieve, if you are going to be in exactly the same financial position on your 100th birthday, as you are today. In my own case, the answer is 1.5%. I have arranged my own affairs in such a way that if my stock portfolio maintains a 1.5% growth rate until I reach my 100th birthday, it should be worth the same as it is today, on that happy occasion in the future. So, having the magic number of 1.5%, let's work with it. By the way, that's net, net -- net of inflation , net of taxes.

Inflation is supposed to be targeted by the Federal Reserve at 2% per year. It wouldn't be wise to count on that, but taken at face value, I can still break even if the nominal portfolio growth rate averages 3.5%, a conservative figure net of taxes. Remember however, you have to pay taxes on any taxable investment expenses. If you sell appreciated stock to have cash for portfolio re-balancing, you probably must pay capital gains taxes, if you take a lot of dividend income you will have to pay standard income taxes on it, if you get a new investment advisor who charges a lot you will probably have to pay him extra for his alleged expertise. In other words, if you get careless in your investment choices, you could find it will require an increased average growth rate, possibly one that is impossible to achieve. But that's your problem, which in my case is 1.5% plus actual inflation, plus investment carelessness about advisors and taxes. Or personal carelessness about housing costs, travel, fancy automobiles, or fancy friends. it means I could achieve a more likely growth rate of 4.5% a year, keep it up until I'm a hundred, and still be approximately where I am today. It seems achievable.

In fact, as you grow older it is less important to preserve every bit of your assets for the inheritance tax bite on the day you happen to die; particularly since inheritance taxes can go as high as 50%, and you can tell yourself you are spending fifty-cent dollars. Estate tax issues are not today's topic, however. For retirement planning, you could take the ancient advice to "spend your last dollar on the day you die." To entertain this illusion for a moment, you can see how much extra you could afford to spend, by dividing your assets by your life expectancy. You can consider that your safety net, but many people would have to consider it a reality, so this is the rough calculation. If you can't afford to retire on that amount, you probably can't afford to retire. This last calculation gets pretty inaccurate unless you are within five, or at most ten, years of retirement.

So all you need for scaring yourself, or sinking back into complacency, is to calculate that growth factor. Please remember the assumptions you made, in compiling it. Essentially, you total up a year's expenses and a year's income; and subtract to determine how much you are saving, or drawing down your reserves. It seems best to list all of the expenses and income on scratch paper, since at first you will want to go over the whole list to see if the year you picked was truly representative. The first step is to purify the list of one-time or odd-ball expenses and income. The second step is to pick out the expenses which are truly frivolous, which you would quickly eliminate in an emergency of some sort; what are the core expenses, what is truly frivolous, and what is desirable but expendable in a pinch. On the income side, there are pensions and annuities which assure you of cash flow, no matter what. There may be a job you plan to quit, or a pension which won't start for a few years. These are the tools you can use, but the main thing is to get that number, the amount could easily be saving, or the amount you must draw down your assets. Notice that we are essentially ignoring how much your assets happen to be, disregarding whether they happen to be a lucky high number, or an ominously small one. Your goal is to see how much you are either adding to them or subtracting from them; the purpose is to try to project where that will go in the future. In addition, you might also project the gain in your portfolio, but it would require several years to be certain about that, and for now we can get along without it.

Now, project that net gain (or loss) to your hundredth birthday. You may live longer than that, but it isn't likely; and you might live less than that, but you won't care if there is money left over for your estate. You might use a computer program to do it, but computers work by a process of "iteration", which means doing the same calculation, over and over again. For this simple purpose, it will suffice to do it with a pencil and paper, because the chances are good that you can project some future events which will interrupt the smooth flow of estimating one year's income from investment, and adding it to the running total. You soon get to 100, even using the crudest arithmetic, and you soon arrive at the net annual gain or loss in your portfolio at age 100, assuming the present rate of growth. If you do this for a few years, your projection will get more and more precise. You now take this number and re-calculate it with a differing growth rate of the portfolio. Start with 6%, and calculate up and down, 8%, then 4%, then 10%, then 2%, then 12%, etc. You vary the growth rate in a systematic way, and watch to see what growth rate of your portfolio will leave you at age 100, with exactly what you have, today. That's the magic number you want to get, the gross break-even growth rate. If it's a positive number, it tells you what growth you have to achieve in your portfolio, and if it's a negative number, it tells you how much you could afford to squander, you lucky person, over and above your present standard of living.

But now you have to see what could upset your applecart, like inflation. Our Federal Reserve has an announced target of 2% inflation, per year. If that happens, which I rather doubt, I need to add 2% to my 1.5%, getting a "real" target of 3.5% growth in my portfolio per year. That's an approximation of how much my portfolio has to grow, just to stay where it is. In my opinion it's achievable, but events may prove otherwise. Investments which promise less than 3.5% are for me not likely to seem safe, they are losers. Investments which pay more than 3.5% are likely to generate funds I cannot live to spend, so they will only generate inheritance costs approaching 50%. So in that happy case, I could consider giving some away, to my heirs, or charities, or whatnot. On the other hand, some young fellow who is projected to need a portfolio growth of 20%, had better consider getting an extra job, or cutting down his expenses--because the history of investments shows that 20% is either totally unachievable, or else involves so much risk that you better not gamble on it.

There's one other thing you can do if you are old, or sick. You can divide what you have by the number of years in your life expectancy, and spend it down. The goal is to spend the last dollar on the last day of your life. I hope everyone understands how unlikely you are to pull that stunt off, but sometimes it has to be considered. Somewhat more realistic is to adjust your life expectancy in this calculation, from 100 down to whatever age seems more likely. And maybe you have to reduce your lifestyle. Otherwise, your best salvation is not from an investment advisor, but from a social worker.

Try it out. Estimate your required net portfolio growth rate, and then add in "what if". What if the stock market collapses, what if inflation goes to 25%, what if social security gets reduced or increased, what if you suddenly acquire a new dependent. The older you are, and the longer you accumulate your own personal financial data, the more accurate the calculation will be. But at any age and in almost any financial circumstances, fixing your attention on that single number will be a North Star, to navigate by.

Friends Lifecare at Home

Over thirty Quaker retirement villages scatter through America, more than twenty in the suburbs of Philadelphia -- "under the care of the Yearly Meeting", as their expression has it. But for some people, community living seems unattractive. It does not speak to their condition.

For one thing, it may not be affordable.

|

| Friends Lifecare |

Or the style of may seem too fancy, or too plain, for some tastes regardless of cost. The increasing emotional rigidity of growing older is a factor; by the time people get to be seventy-five, they had better make this decision or forget it. Plenty of people are hale and hearty at ninety, but they establish pretty firm ideas about the sort of person they want for neighbors while they are still in the workforce. Quite often it's just a habit, people have lived in their home for several generations and cannot imagine another neighborhood, lifestyle, or environment. This is home, and they intend to die there.

So, to address this need, or market, a group of Quakers conceived of a retirement village without walls. Live in your own home and someone will come to oversee things, will know what to do if there is an emergency, and may eventually make the decision for you that you absolutely must go somewhere else. All of this is wrapped within an insurance vehicle, to recognize the fixed incomes of retired people, the inevitability of terminal illnesses, and the occasional risk of monumental medical expenses. At present, about 1600 people in Philadelphia are enrolled in the unique plan of Friends Lifecare at Home, making it one of the largest retirement communities in the country. The organization receives universal praise for its imaginative responses, as well as the dependability and high quality of the people it sends out to the homes of subscribers. Friends Lifecare is a pioneer, and it is gradually weeding out the ideas that didn't work and adding new features that were not originally contemplated. One of its greatest challenges is the need to adapt to unexpected and uncontrollable changes in the Medicare program. Slashes in the Medicare program could bankrupt Friends Lifecare, and even sudden windfalls like the Medicare Drug Benefit create management problems. There can be no doubt that one element of trust exists for which there is no substitute; Philadelphians know that the invisible support of the community and its Quaker core is behind them. If anyone can possibly preserve a moral commitment to the elderly, it will be the Quakers.

Ultimately, the commitment is not so much to 1600 subscribers as to the notion of finding out what works. Life expectancy has extended by three additional years, during the past ten; that's a joy, but it's a problem to finance. The optimum size of the organization is also an unsettled question. Although this program is relatively large by comparison with individual retirement villages, it may not be large enough to have spare capacity to cope with influenza epidemics or record-breaking spells of bad weather. Since it's the only one of its kind, it is vexed by the popularity in ever-widening geographic areas. It must grow to some reasonable size in one area before it can spread its resources to another. By the same reasoning, it must have a reasonable number of prosperous subscribers if it is to accept even a limited number of poor ones.

The idea of creating a seamless partnership with the residential-type retirement villages is certainly attractive, but Friends Lifecare must be careful to avoid becoming too much of a life raft for other people's problems. When the resale price of residential housing rises in a housing bubble, people wish to cling to a rising investment. During the same economic period, the entry and rental price of residential villages also rise. With a great many uncertainties that are specific to this pioneering effort, it is hard to know what policies to develop to insulate the lifecare environment from speculation in the mortgage and housing markets. Or, right now, high-rise apartment development. All of this creates a need for clear minds in the governance, determined to see and acknowledge difficult reality. If anyone can do it, Quakers can.

Designated Lifetime Funds

|

| Social Security |

Except for Social Security, most retirement funds are not required to be tax-sheltered ("Federally Qualified"), but one would be foolish not to take advantage of the option where possible. Ordinarily, just about every other form of saving must first net out federal taxes. The debts of state governments ("municipal bonds") are free of federal but not state taxes, but reflect that benefit by paying a lower interest rate; any overall advantage must be calculated individually, and quite often it is non-existent. Mandatory taxable income, more-or-less mandatory tax-exempt income, and optional; that's your choice, except for the decision to put them in a federally qualified pension fund. Most people just throw the ownership certificates into a safe-deposit box and forget them. This article suggests you create three funds, whether in a lock-box or brokerage account and mentally rename them by overall purpose. There's not much you can do about tax status, but you have a little latitude about how and when you spend the money. It can make a certain amount of difference because increasingly it is true that investment performance is affected by taxes and fees. Friends, neighbors, and classmates may tell dazzling stories about astonishing investment luck, but if you want to have the best performance in your social circle over the very long haul, you would be well advised to focus on taxes, transaction costs, and fees. Especially fees.

|

| Saving Bonds |

When Grandpa gives a brand-new grandchild a hundred dollars, it can be spent on a new rattle or it can be invested. Rattles usually win, but occasionally it gets invested; what it's worth when the newborn finally dies will mostly depend on two things: how old he is when he dies, and how young he was when he started the investment. To make it easy to calculate, let's assume a life expectancy of 85 years, and an interest rate of 7%; that seems to imply a value of $40,000 at the time of death. That seems to imply a value of zero if he dies without spending any of it, and value somewhere around $30,000 if he pays current income taxes. But if he pays $100 a year for the lock-box, he will only have $20,000 left after expenses. And if he pays fees for his checking account, or receives only nominal interest for a savings account, he may end up with nothing at all. Since that's the usual outcome of most cases of Grandfather gifts, perhaps the choice of a rattle isn't so reprehensible. The whole investment process is too expensive to bother with until the sum involved is several thousand dollars. At fifty times the hundred dollar gift we started with, the investment is $5000, and its final result is a retirement fund of two million dollars. Yes, the arithmetic can be argued with, and yes, lots of things can go wrong in 85 years. Maybe a one-million dollar benefit is more likely, but no one can dispute that it's a pretty easy way to die a millionaire instead of a paper.

All right, that's your Contingency Fund. It's taxable, but almost everyone can start it pretty young and forget about it for long periods of time.

|

| Tax Fund |

The Tax Exempt Fund gets created when you start to work, even for a few days as a teenager. Several percents of your earnings will be withheld for the Social Security program, which requires that you apply for a Social Security number. If you wish, you can start depositing up to a set limit of your earnings as a tax-exempt fund for retirement, currently called an IRA or a 401-k fund. Your income taxes for the current year will be tax-sheltered, up to the amount taxed on the amount you contribute. It's a good thing to get one of these funds started as soon as you are legally able to do it, so the mechanics are completed while the amounts are still small. The suggested funds are the ones with the smallest administrative costs, which will probably be no-load index funds; if the fund you choose has more than a trillion dollars under its control, you are probably reasonably safe. Try to keep depositing automatically, right up to the maximum amount allowed by the law, right up to the day you die if they will let you, and select the option of automatically re-investing any dividends. Until these vehicles were created, just about the only tax-exempt investments anyone could buy were tax-exempt municipal bonds and life insurance. Both of these vehicles have some major disadvantages; the IRA and 401-k mechanisms allow you to apply the tax exemption to just about any investment you choose, so they are just as good as anything you can buy, plus having the advantage of being tax sheltered. If anyone proposes investments other than IRA/401-k before you exhaust the limits of these, that person has some serious explaining to do; at the very least get a second opinion. It will be a rare person under the age of forty, perhaps an entertainer or professional athlete, who has money left to invest after fully exhausting the tax exemptions. That's because the typical young person takes on the burden of buying a house or paying for private education for children, and there just isn't enough money to go around.

|

| Life Insurance |

Life Insurance is a comparatively poor investment, and it is an even worse investment if it is purchased without investigation or comparison shopping. Some insurance companies, like Northwestern Mutual, have considerably better results than the average, and some other very large, very famous "leading" life insurance companies have pretty inferior results. Life insurance does provide some tax exemption, however, which varies a little between states as a result of the McCarran Fergusson Act of 1945. However, the legislation does produce tricky features, like tax-exempting either the owner or the beneficiary of the policy, but not both. The entire first-year premium is ordinarily paid to the salesman as a commission, and sometimes the commissions continue for life. But that is only part of the incentive which the life insurance salesman has for selling excess coverage. The other incentive is worth serious pondering: the main source of life insurance profits derives from a large number of clients who pay premiums for a while and then drop the policy without collecting on it. The deplorable national statistics on temporary job loss, personal bankruptcies, and divorce carry implications of considerable weight for the purchase of life insurance; investment is limited to what you happen to have, but life insurance is based on projections of what you hope to have, or what you fear.

Reflections on Immortality

|

| Notions of Immortality |

When we are children, we have childish notions of immortality. Perhaps we still nourish them for lack of replacement, busying our thoughts with premature death, instead. Most of us forget the dreams of robbing candy stores or marrying a princess, and never bother to replace them. After all, everyone has to die, don't they?

So put it this way: we now have semi-realistic plans to end our lives with a thirty-year paid vacation, but what can be said about a fifty-year paid vacation, or even a hundred? Life itself is degraded by seventy years of loafing, as those who could afford it will tell you. All notions of purpose to life eventually disappear. No longer defining ourselves as soldiers and housewives; we're just cats, dogs and lice. And all our yesteryears have lighted fools the way to welcome death. As that day approaches, it will be marked by waves of awesome but fruitless literature. The Calvinist worship of work gets the last laugh of the comedy.

Subsequent generations of would-be hedonists have certainly given Calvin a hard time. Harder, in a way, than dunkings and pillories. Perhaps harder even than burning at the stake, because Calvinists had the audacity to get rich and comfortable by their effrontery. Perhaps poor and comfortable is better, and comfortable is the real goal, as Quakers were executed for advising. Once you get over the ambition to be King, what else is there?

14 Blogs

Retirement Planning

A process to determine the amount of investment portfolio to accumulate for retirement.

Insurance

Insurance comes in many types, many mis-understood. There's Risk Management, which is very important; and there's Investment, which is often better done with products other than insurance.

Special Education, Special Problems

Until recently, mentally retarded children weren't even considered in school budgets. But in recent decades, they have become one of the biggest challenges.

Until recently, mentally retarded children weren't even considered in school budgets. But in recent decades, they have become one of the biggest challenges.

Disappearing Stock Power

The proxy voting power of corporate common stock is disappearing every day, by thousands of shares.

The proxy voting power of corporate common stock is disappearing every day, by thousands of shares.

Force Justifying the Use of Force

Basic Lifetime Health Care?

One of the main reasons healthcare payments are so fragmented, is that it is so difficult to imagine how to unify them.

Stretching Out Your Retirement Savings

"Don't spend principal" is pretty good advice, except as retirement income starts to run low.

"Don't spend principal" is pretty good advice, except as retirement income starts to run low.

New York Times: Splendid Idea for Old Age

New blog 2019-04-09 16:12:52 description

Increased Potential for Retirement Villages

Third-party insurance is blocking certain patient preferences, as demonstrated by what rich people prefer to do when they are sick.

Third-party insurance is blocking certain patient preferences, as demonstrated by what rich people prefer to do when they are sick.

Critical Number for Retirement Planning

There are a zillion factors involved in answering the common question: how much is enough to retire on. We propose that one number is central to any such analysis, for everybody. And it's reasonably easy to estimate.

There are a zillion factors involved in answering the common question: how much is enough to retire on. We propose that one number is central to any such analysis, for everybody. And it's reasonably easy to estimate.

Friends Lifecare at Home

Philadelphia Quakers run over twenty retirement communities for the elderly in their region. One of them is a virtual village, one without walls.

Philadelphia Quakers run over twenty retirement communities for the elderly in their region. One of them is a virtual village, one without walls.

Designated Lifetime Funds

Nowadays, the government incentivizes most investment funds to be taxable, but curiously certain funds are forced to be tax-sheltered, while personal latitude exists for others. Since most people are eventually forced into having three types of funds anyway, some thought might be given to which purposes are most suitable.

Nowadays, the government incentivizes most investment funds to be taxable, but curiously certain funds are forced to be tax-sheltered, while personal latitude exists for others. Since most people are eventually forced into having three types of funds anyway, some thought might be given to which purposes are most suitable.