Related Topics

Right Angle Club: 2016

In progress.

Right Angle Club 2017

Dick Palmer and Bill Dorsey died this year. We will miss them.

H.I.V., AIDS, and the Law

|

| AIDS |

We had a meeting in March at our new quarters in the Pyramid Club, conventional in all respects except members were urged to bring a female guest. It was extremely well attended, which probably improved the food somewhat. Come to think of it, the jokes were cleaned up a little bit, too. But because the central subject was also doubly controversial, covering both the subject of AIDS and the trial bar, I omit all names from this report, in an effort to maintain neutrality on the specific case matter, while discussing the general subject of conflict between the bar and the medical profession.

|

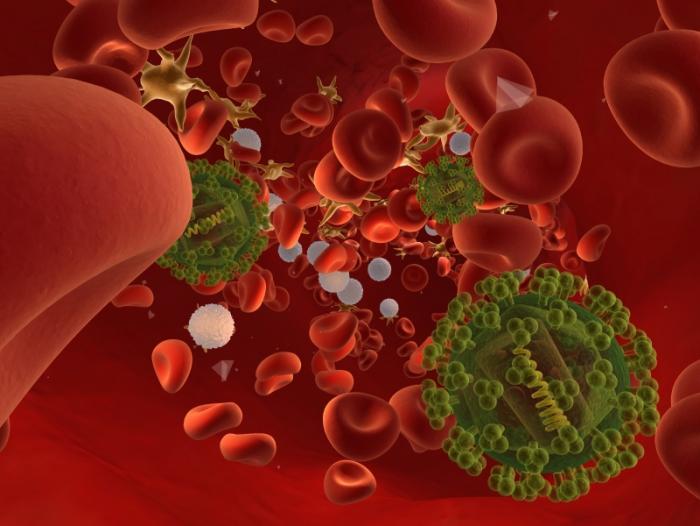

| AIDS knowledge |

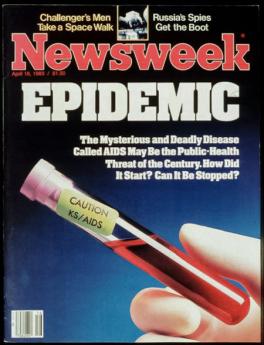

The case under discussion took place in 1987, so it is important to remember the state of knowledge about A.I.D.S at that moment. Nobody knew for certain what caused the disease, or how to treat it. It was universally fatal and seemed to be contagious in some way. At least, it seemed to originate in Africa among primates, and when brought to America through Haiti, seemed to concentrate on male homosexuals, although not exclusively. It had a peculiar concentration of brain tumors and a strange proclivity for yeast infections of the lung. At first, there was no test for this condition, but over the course of fifteen years went from a totally mysterious and ominous condition to a curable disease. Indeed a largely preventable one, caused by a virus of the retro-virus variety, for which a highly reliable blood test was devised, and quite effective treatment. Comparatively few Americans now die of AIDS, now called H.I.V. infection, although the disease continues to spread devastation in countries with more primitive medical systems. I hope I have given a fair summary of one of the most rapid investigations into a new complex disease in all of medical history. Enormous amounts of money were poured into research in this condition, probably greatly stimulated by public pressure generated by the gay community, and others.

|

| "Philadelphia" |

The lawyer who presented the case to us was called into the matter by a client who had been fired because he had the condition. How much the client, defendant law firm, or plaintiff lawyer knew about the condition at the time was not elaborated. But it surely was incomplete, quite possibly quite rudimentary. Expert witnesses were consulted, although it is not clear how much they could have known at the time, either. In any event, it was determined the patient was still able to work at the time he was fired. The state of the law on the subject was equally fuzzy in 1987, and the basis of the claim was an infringement of disability fairness or some legal variation of this language. He wasn't disabled, was the basis for the court's decision, and in a sense that was true.

However, a question was raised from the audience as to whether the issue of contagiousness in the workplace was raised, and the plaintiff lawyer replied it was not; perhaps his impromptu response was somehow inaccurate. However, taking matters at face value, it is possible to imagine the executive of the firm was alarmed by the possibility that other members of the firm would resign rather than subject themselves to the hazard of contracting the disease themselves, thereby destroying the firm. Even so, dismissing the employee seems excessive; he might have been given a medical leave of absence, or some other means of preventing the spread of the disease might have been devised. But the point is the firm had a legitimate concern, and probably could not be sure of reassuring the other employees in a scientific way; an unwarranted panic could not be prevented by legitimate scientific arguments available at the time. That the firm chose a cumbersome unfair way of protecting themselves is not completely surprising, any more than a guaranteed way to escape a fire in a theater is even now available, except by not going to the theater.

|

| Louis Pasteur |

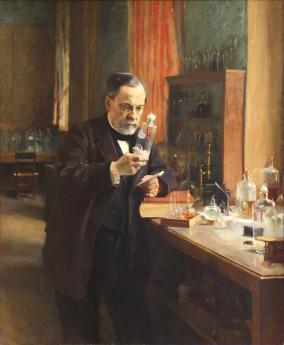

Until Louis Pasteur discovered the germ theory of disease around 1880, epidemics of contagious disease devastated whole communities for thousands of years. Thucydides described an epidemic in ancient Athens hundreds of years B.C., and even today we are not entirely certain what that disease really was. Since that time, society has developed legal and management techniques of mild utility, since the courts have had to devise some sort of order out of this panic situation. But whether the best scientific approach takes fifteen years to emerge, or centuries, the court decision has to be made on principles which may seem wrong-headed in retrospect. Once the scientific facts are firmly established, the process of undoing unfortunate precedents has to be commenced during which, further blunderings may take place. Finally, the courts and the medical profession may come to agree on the best approach, but it can take a long time. Since presumably there will be future outbreaks of future unknown diseases, I have a suggestion.

Discussions between the two professions ought to be held, to devise a mechanism of appeal to a special scientific court devoted to the problem which arises. The appeals court should refrain from issuing legal opinions until the scientific matter seems to have settled down, but a scientific opinion about the current state of scientific understanding might be quite welcome. At least the provisional court would know its decision would have to be provisional, anticipating later revisions of the law which undo judicial precedents set in a time when only expediency was possible. The situation already exists of the Courts of Equity, designed to meet situations where injustice obviously exists, but no law can adequately address it.

Originally published: Saturday, March 05, 2016; most-recently modified: Tuesday, May 21, 2019