4 Volumes

Revolutionary War Era

The shot heard 'round the world.

Invaders of Pennsylvania

For a peaceful state, Pennsylvania has suffered many invasions. It's all been one-way; Pennsylvania has never invaded anyone else.

Philadephia: America's Capital, 1774-1800

The Continental Congress met in Philadelphia from 1774 to 1788. Next, the new republic had its capital here from 1790 to 1800. Thoroughly Quaker Philadelphia was in the center of the founding twenty-five years when, and where, the enduring political institutions of America emerged.

History: Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Philadelphia and the Quaker Colonies

Revolutionary Philadelphia's Loyalists

History is written by the victors, so the Tory Loyalists of Revolutionary Philadelphia have mostly fallen from view.

But two hundred years later looking back, is it unrealistic to point out that India and a whole flock of other members of the British Empire, wanted, fought for, and achieved their independence? Two world wars had something to do with it, but isn't it possible that such a world empire is difficult if not impossible to sustain. And that American independence was bound to come about, somehow, at some time perhaps without a war?

Pembertons

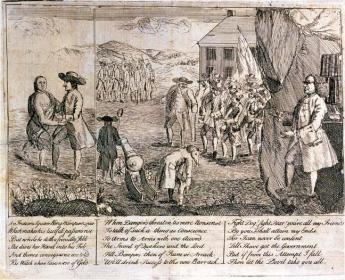

|

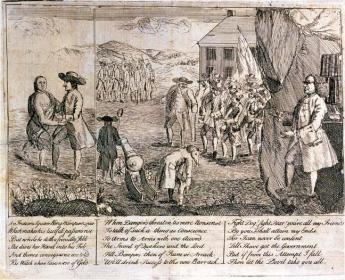

| Israel Pemberton, Ben Franklin satire l |

Ralph Pemberton was an English Quaker well before 1650; he may have been a Quaker before William Penn was one. As an old man, he accompanied his son Phineas to Pennsylvania in 1682. They established a farm on the banks of Delaware in Bucks County called Grove Place, and Phineas soon became one of the chief men in the colony. In the next generation, Israel Pemberton became one of the best educated, richest merchants in the colony. But it was Israel's son also called Israel, who earned the title of King of the Quakers. He was one of the founding Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital along with Benjamin Franklin and one of his brothers, James Pemberton, and was a generous philanthropist and leader of a number of other civic organizations. Just exactly what provoked his famous political disputes with Franklin is not clear, but he was a leading friend of the Indians, whom Franklin never much liked. Israel Pemberton strongly and effectively argued William Penn's policy of friendship with the Indians, particularly insisting that sales of land to colonists should be prevented until there was a clear agreement with the Indians about the ownership. Unfortunately, pressures built up as Europeans immigrated faster than this policy could accommodate smoothly, and Franklin mostly sided with the impatient immigrants -- and squatters. This disagreement came to a head in 1756 when Pemberton negotiated a treaty of peace with the Indians at a conference at Easton. Although this treaty seemed to settle matters, it came against a background of the descendants of William Penn abandoning Quakerism. They, however, remained the proprietary owners of the Province with a more narrow focus on speeding up land sales to maximize their investment. Much of the internal dynamics of these quarrels before the Revolutionary War remain unclear and possibly somewhat misrepresented.

|

| Shenandoah Valley |

When the Revolution came, Pemberton viewed it with disfavor, mostly for pacifist rather than purely Tory reasons. Feelings ran high since the Pembertons were influential citizens with the potential to dissuade wavering neighbors, which made it difficult to tolerate them as invisible bystanders. However that may be, the three Pemberton brothers and twenty other wealthy and influential Quakers were arrested and, without hearing or trial, thrown in the back of an oxcart and sent into exile in Virginia for eight months. Their journey was a curious one, along a trail up the Schuylkill to the ford at Pottstown, and then down the Shenandoah Valley, an area in which they were well known and highly respected, greeted with great sympathy as they traveled. Isaac's brother John, who had spent several years as a missionary, died during this exile.

|

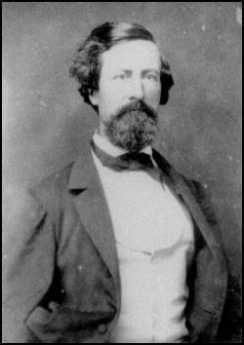

| John Clifford Pemberton |

In some ways, the most curiously notable Pemberton was John Clifford Pemberton, who applied to West Point on his own initiative and was appointed by Andrew Jackson who had been a friend of his father. In itself, it is curious that so combative a person and so vigorous an enemy of the Indians -- as Jackson certainly was -- would have Quaker friendships. But he did not misjudge John Clifford, who became a diligent professional warrior for his country in a number of military incidents with the Indians, the Mexicans, and the Canadians, rising to the rank of captain in the regular Army at the opening of the Civil War. In spite of personal efforts by General Winfield Scott to dissuade him, he resigned his commission and volunteered in the Confederate army. He was quickly promoted to major, then a brigadier general and eventually to Lieutenant General. As such, he was the commanding Confederate officer at the fifty-day siege of Vicksburg where he was finally forced to surrender to Grant's army. In a prisoner exchange, he was returned to the Confederate side, which they had no openings for Lieutenant Generals. He resigned and re-enlisted as a common soldier, but was quickly promoted to the rank of Colonel, in charge of the artillery at the final siege of Richmond. After the war, he became a farmer in Warrenton, Virginia, but was visiting at the family home in Penllyn when he died in 1881. John Clifford Pemberton, the highest-ranking general on the grounds, lies buried in Laurel Hill cemetery right next to Israel Pemberton. In some sort of triumph of the South, he here out-ranks George Gordon Meade, the hero of Gettysburg. Just how his pacifist family reconciled itself to his heroism can only be imagined.

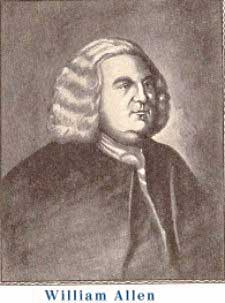

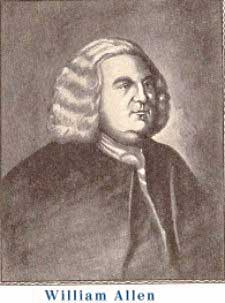

William Allen, Tory

|

| William Allen |

William Allen was once famous for his expensive carriage and a team of horses, at a time when there were only eighty carriages in the colony. He was born wealthy but personally made considerable sums in maritime trade, which in those days included a mild form of piracy called privateering. Taking his accumulated wealth, he invested heavily in colonial real estate. His urban ventures included the land under Independence Hall, and his lands in the hinterland included the present town of Easton. He was a tough businessman, providing "muscle" where needed in a colony dominated by pacifist Quakers. At one point, he imported a thousand muskets and ammunition for the use of settlers in the Lehigh Valley who had difficulties with the Indians and Connecticut invaders. Allentown is named after him.

|

| Philadelphia Lawyer |

It is difficult to apply present standards of judgment to Allen. William Penn had been given the colony on condition that he protect and maintain it. That was clearly a difficult challenge for a Quaker colony in the wilderness, surrounded by Indians, French and Spanish buccaneers, and neighboring colonies who were far from pacifist themselves. The system often amounted to giving land to subcontractors like Allen, on condition that they maintain law and order. Furthermore, Allen was quite obviously a person of parts. His credentials as Chief Justice were based on his attendance at the Inns of Court when almost all other lawyers were trained by local apprenticeships. His father in law was Andrew Hamilton, the famous "Philadelphia lawyer" who won the landmark case for Peter Zenger and later became the leader of the Pennsylvania Assembly and mentor to young Benjamin Franklin. His land-dispute services in the negotiations with Lord Baltimore were notable. In general, he was a continuing force for peace and stability, and no one held it against him that peace and stability suited his needs as a landlord and merchant. To him, the battle for independence was just another unsettling disturbance which prevented the colony from achieving its potential.

His daughter married John Penn, the grandson of William Penn, who was the local representative of the Proprietors and later the Governor. All in all, it is not surprising that he retreated to his home on Germantown Avenue, called Mt. Airy, when the revolution broke out. Unlike many other Tories who fled to Canada, he felt his past services would protect him if he remained quiet and secluded until the war was over. He didn't quite make it, dying in his mansion, in 1780.

Meschianza

|

| General Howe |

The British under General Howe occupied Philadelphia for a little more than six months, withdrawing at the end of May 1778. Washington and his starving troops were shivering in the miserable encampment at Valley Forge that winter, and it is easy to imagine the British encircling, besieging or storming the encampment to put an end to the war then and there. Instead, Howe settled down in the enemy capital and had a merry time of it. Historians differ about the reasons for this puzzling behavior. On the one hand, Howe never did any campaigning in the winter if he could help it, somehow feeling that gentlemen soldiers had a right to revel, just as school children now feel they have a right to loaf in the summer. Perhaps there were practical military reasons to avoid winter campaigns, as well. However, it is also true that Howe had shown whig sympathies in the past, and very likely did feel that conciliation with the colonists was not only a possible but the best possible outcome of the dispute. If that was his idea, he was listening too much to the rich Tories in Philadelphia and not enough to the scowling artisan class, or to the solemn-faced Quakers. All winter long, the British soldiers revealed in theatricals and parties, apparently oblivious to the starvation nearby, or the appalled reactions of the sober Quakers to music, dancing, and ornamental dress. If Howe had any purpose to bedazzle the populace, he could not have put a better man in charge than his Lieutenant-General Major John Andre, whose thumb-in-your-eye attitude was defiantly underlined by his taking up Benjamin Franklin's own house as his pied a Terre.

Andre certainly cut a fine figure. It would be hard to say whether John Burgoyne or John Andre was the most dashing man in England, but it was surely one or the other. They both wrote plays and poetry of professional quality, designed costumes and scenery, and organized one extravaganza after another. They were both handsome in the eyes of ladies, and fearless soldiers in the eyes of men. Anything you can do, I can do better.

About the time Howe was replaced by General Henry Clinton and recalled to England, the position in Philadelphia began to look dangerous for the British. The French signed an alliance with the American Revolutionists earlier that spring, and the concern became a real one that the French fleet might blockade the mouth of Delaware and trap the British Army, stranded a hundred miles upriver from its own Navy. When Andre learned they were leaving, he saw they needed to have a celebration that would be remembered.

|

| Benedict Arnold |

Even today, the day-and-night revelry is indeed remembered. Andre wrote a detailed description for his local girlfriend Peggy Chew (the daughter of Pennsylvania's Chief Justice) that is really something to read. Made all the more pointed with our present hindsight that Peggy Chew was the best friend of the Peggy Shippen who married Benedict Arnold, the letter gives the celebration a made-up name, Meschianza. Sometimes spelled Mischianza, the derivation is loosely connected to the Italian word for Medley. It began with a regatta of costumed soldiers and local ladies on barges sailing slowly down the river accompanied by cannon fire, singing, and music. The main events of the week took place on the South Philadelphia plantation of Joseph Wharton, now called 5th and Wharton Streets. Horsemen of the British Army put on a Medieval tournament with jousting and whatever, dressed in white and pink satin, and hats of pink silk with white feathers on the brim. There were fireworks at night and banquets. Good wine, toasts, and laughter to witty remarks. The final high point was a fancy dress ball. Wow.

And then, the British moved across the river to New Jersey, and were gone.

REFERENCES

| Treacherous Beauty: Peggy Shippen, the Woman behind Benedict Arnold's Plot to Betray America: Mark Jacob:978-0762773886 | Amazon |

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

|

| The Wyoming Massacre |

The six nations of Iroquois dominated Northeastern America by the same means the Incas dominated Peru -- commanding the headwaters of several rivers, the Hudson, the Delaware, and the Susquehanna, as well as the long finger lakes of New York, leading like rivers toward Lakes Ontario and Erie. They were thus able to strike quickly by canoe over a large territory. Iroquois were quite loyal to the British because of the efforts of Sir William Johnson, who settled among them and helped them advance to quite a sophisticated civilization. It even seems likely that another fifty years of peace would have brought them to an approximately western level of culture. Aside from Johnson, who was treated as almost a God, their leader was a Dartmouth graduate named Brant.

Brant, The Noble Savage

The mixed nature of the Iroquois is illustrated by the fact, on the one hand, that Sachem Brant translated the Bible into Mohawk and traveled in England raising money for his church. On the other hand, his biographers trouble to praise him for never killing women and children with his own hands. British loyalty to these fierce but promising pupils was one of the main reasons for the 1768 proclamation forbidding colonist settlement to the West of what we now call the Appalachian Trail, which on the other hand was itself one of the main grievances of the rebellious land-speculating colonists. The Indians, for their part, saw the proclamation line as their last hope for survival. After Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the Indian allies were free to, and probably urged to, attack Wyoming Valley.

It is now politically incorrect to dwell on Indian massacres, but this one was both exceptionally savage, and very close to home. The Iroquois set about systematically exterminating the rather large Connecticut sub-colony and came pretty close to doing so. Children were thrown into bonfires, women were systematically scalped and butchered. The common soldiers who survived were forced to lie on a flat rock while Queen Esther, "a squaw of political prominence, passed around the circle singing a war-song and dashing out their brains." That was for common soldiers. The officers were singled out and shot in the thigh bone so they would be available to be tortured to death after the battle. The Wyoming Massacre was a hideous event, by any standard, and it went on for days afterward, as fugitives were hunted down and outlying settlements burned to the ground.

It's pretty hard to defend a massacre of this degree of savagery, but the Indians did have a point. They quite rightly saw that white settler penetration of the Proclamation Line would inevitably lead to more penetration, and eventually to the total loss of their homeland. The defeat of a whole British Army under Burgoyne showed them that they were all alone. It was do or die, now or never. Countless other civilizations have been extinguished by provoking a remorseless revenge in preference to a meek surrender.

Perth Amboy Revisited

|

| Perth Amboy |

It's now moderately complicated to find Perth Amboy, New Jersey, even after you locate it on a map. Like New Castle DE it flourished early because it was on a narrow strip of strategic land, and like New Castle, eventually found itself cut off by a dozen lanes of highways crowded together by geography. It's an easy drive in both cases only if you make the correct turns at a couple of crowded intersections. Both towns were important destinations in the Eighteenth century, but by the Twentieth century, both were pushed aside by traffic rushing to bigger destinations. Industrialization hit the region around Perth Amboy somewhat harder than New Castle, destroying more landmarks, and bringing to an end its brief flurry as a metropolitan beach resort. If you aspire to preserve your Eighteenth-century glory, it's easier if you don't have too much progress in the Nineteenth. In Perth Amboy's defense, it must be noted that Jamestown and Williamsburg, Virginia had just about totally disappeared when noticed by Charles Peterson and John Rockefeller, but neither of those towns was run over by Nineteenth century industrialization. So, while New Castle has treasures to preserve and display, Perth Amboy seems to have only the Governor's mansion like the one notable building to work with. William Franklin, the illegitimate son of Benjamin, was the royal governor installed in this palace shortly before 1776.

|

| Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy |

While it is true that some wealthy local inhabitants did a lot to restore and maintain New Castle (and Williamsburg), the Governor's mansion in Perth Amboy was bought and made the home of Mathias Bruen, who is 1820 was thought to be the richest man in America. If Bruen had only had the necessary imagination and generosity, this was probably the best moment for Perth Amboy to have had a historical restoration. Instead, he added some unfortunate features to the mansion; it later became a hotel, and later on, an office building. Public-spirited local citizens are now trying to set things right, but the costs are pretty daunting. Someone has to find an inspired Wall Street billionaire like Ned Johnson to make over an entire town. Occasionally, a state government will do it, as has been done with Pennsbury. Or a national organization might become inspired, as happened with Mt. Vernon and Arlington. Its present state of peeling paint and makeshift repairs suggests uninterest in Perth Amboy's Governor Mansion by the State, and the absence of whatever it is that occasionally inspires fierce and determined local leadership. Perth Amboy needs some help and needs to forget about its handicaps. Sure, it's hard to commute anywhere, it's even hard to drive across the highways to the countryside. The bluff on the promontory was once quite arresting, now a rusting steel mill occupies that spot. Other than that, it doesn't look ominous or dangerous at all. It's just forgotten.

|

| Pennsbury Mansion |

Aside from the Royal Governor's former mansion, it is hard to find a historical marker or monument in this scene of former prosperity and glory, but there is one. Down on the beach is a bronze plaque, commemorating the 150th anniversary of the founding of -- Argentina. So there's a clue, which is not difficult to associate with all of the Hispanic names on the stores, and the Hispanics in evidence on all sides. They all seemed to know that this was once the capital of New Jersey, seemed pleased with it, and could point out the famous building. They are pleasant and friendly enough. Perhaps even a little too comfortable. Because, as William Franklin's famous father once said, all progress begins with discontent.

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

|

| General Burgoyne |

After defeating Washington's troops at the battle of Germantown, the British then occupied Philadelphia for the better part of a year. The town was a mess, with food shortages typical of the squalor of any occupying army equalling the existing population. Washington was forced to fall back to the natural fortress of Valley Forge. The city of Philadelphia was not exactly under siege, but it was as difficult a place for British troops to live as a besieged city. For his part, Washington was forced to shiver and starve in the nearby mountain valley, at least consoled by distant news of American achievements. General Burgoyne and his army were soon captured at Saratoga by General Gates under humiliating circumstances. Clearly, the dashing hero of this event had been Benedict Arnold on a white horse leading the charge, getting wounded in the leg in the process.

|

| Benjamin Franklin in Paris |

Benjamin Franklin in Paris trumpeted the news of this victory, reminding the French of Washington's earlier victory at Trenton, and maneuvering it all into a treaty of alliance. With the French fleet in the nearby Caribbean, Philadelphia was no longer a safe place for the British to stay a hundred miles upriver, and the idea of abandoning occupied Philadelphia began to grow. Having gambled on British victory in defiance of London's orders, the Howe brothers were not in a position to argue with new orders. The British soldiers inside the city were more comfortably housed than the American troops outside it, but nobody was exactly comfortable. The American Congress had, of course, fled to the hinterlands. All in all, it suddenly became uncertain who was going to win this war.

|

| Peggy Shippen |

The American population at this time has been described as a one-third rebel, one-third Tory, and one-third trying to hunker down to see who would win. Many of the seriously committed Tories had fled from Philadelphia when the rebels took charge, while pacifist Quakers were a little hard to classify. Generally speaking, the prosperous merchant class had never been persuaded King George was all that bad, while the less prosperous artisans were the fervent patriots. Under such conditions, many people who privately leaned in either direction found it was best to seem non-committal. The British were billeted in private homes; the Officers in the best houses of the merchant class, the common soldiers generally housed in the homes of the artisans. Although the soldiers and the artisans did not mix very well, circumstances permitted the aristocratic officers getting on pretty well with the merchants whose houses they occupied. The girls in the colonial families seemed immediately attractive to the British officers, who were far from home, while the officers also seemed pretty glamorous to the girls. So, it is not exactly surprising that the most beautiful colonial belles like Peggy Shippen and Peggy Chew found themselves frequently in company with dashing officers like Major John Andre. Andre would likely have been a heartthrob in any circumstance since he had risen to the rank of adjutant-general at a young age, wrote poetry and plays, reputedly was rich, and was regularly the life of any party. Nor is it surprising that generations of Peggy's descendants have treasured a lock of his hair.

|

| Margaret Oswald Chew Howard |

When the decision was finally made to abandon Philadelphia, six of the British officers personally contributed twenty-five thousand dollars to throwing Philadelphia's most famous, most splendiferous party, called The Machianza. It went on for days, had real jousting matches between officers dressed like knights in armor, banquets and all that sort of thing. It was Andre's idea, and he was enthusiastically in charge. Surviving records of the event do not show that Peggy Shippen was present, but in view of what happened later, much of her correspondence has been destroyed. It's pretty hard to imagine she wasn't there.

|

| Major General Benedict Arnold |

The British then marched away, and Washington's troops cautiously followed, assuming control of the city. Major General Benedict Arnold had been sent from Saratoga to Valley Forge to recover from his leg wound, and probably also to raise morale among the troops celebrating the now-famous hero. Washington more or less immediately decided to pursue the British across New Jersey, thus leading to the battle of Monmouth as the two armies raced for the Naval vessels in lower New York harbor. Since General Arnold had not fully recovered from his wounds, he was installed as the military governor of a somewhat bedraggled Philadelphia. Naturally, he was the center of the social scene, and soon was pursuing Peggy Shippen in every way he knew, which included some pretty gloppy letters in Romantic style. Peggy's father was uneasy about his intentions but was eventually mollified by Arnold's purchase of the house called Mount Pleasant, now a tourist attraction in Fairmount Park. With this evidence that his prospective son in law was at least likely to stay in Philadelphia, Edward Shippen finally repented of his opposition to the marriage of his daughter. But the new couple were soon off to West Point, where Arnold had kept up a persuasion campaign with George Washington, to get himself appointed the commandant of the main northern defense of the Hudson River. A point for Philadelphian tour guides to remember is that Peggy and Benedict never got a chance to live in Mount Pleasant.

Arnold originally lived in New Haven, Connecticut, where he had established quite a sea-faring reputation as a merchant, some would say privateer, others would say buccaneer. There is no doubt he was aggressive, and combative, and considered himself a little bit above the law. These qualities made him outstanding at Fort Ticonderoga and Saratoga, and are always more highly valued in young men in a war. Unfortunately, he made a bitter enemy of Joseph Read who was briefly his neighbor, and later was President of the Continental Congress. Read accused Arnold of smuggling and trading with the enemy, and was so determined about it that Arnold was scheduled for court-martial, but postponed. Arnold was loudly defensive about the whole matter, and public sympathy was on his side. In view of what soon happened, he might well have been cleared by the court, but likely there was some truth to the accusations. Using Peggy as a go-between, he entered into a correspondence with Andre (then the adjutant-general in New York) offering to deliver the surrender of West Point, three thousand prisoners, and possibly George Washington himself in return for what might today be half a million dollars. As a note of realism, he was willing to accept half that in the event of failure. The British were particularly anxious to acquire American prisoners to exchange for their own troops captured at Saratoga. Unless Arnold was a total sociopath, he must have thought he had quite a grievance.

|

| Lord Cornwallis |

Things went along surprisingly well at first, with negotiations for price back and forth, plans for attacking West Point moving along with the Navy, and Andre disguising himself for a visit to Arnold in his house to the south of the Fort on West Point. Much of the success was due to the movie-star reputation of Benedict Arnold; few could imagine such a hero doing such an unheard-of thing. However, the plot was discovered while Washington was away visiting the Fort, and Arnold hastily abandoned his family and fled to a waiting British warship. Andre decided to make his way south to the ship through rebel territory, but local soldiers and farmers were much more suspicious than others had been, and after penetrating his disguise, found incriminating papers concealed in his boots. Since he was out of uniform behind enemy lines, Andre was by definition a spy, which required hanging. He made a plea to be shot like a gentleman, but Washington with tears allegedly in his eyes refused. With much bravado, Andre jumped atop his own casket and placed the noose around his own neck, a behavior much admired by his compatriots when they heard of it

Meanwhile, Peggy had put on a crazy-woman act which apparently convinced Washington to be lenient, and allow her to rejoin her husband. The couple stayed in New York for a few months, toying with commands of loyalist troops in the south, but eventually taking ship for England. Lord Cornwallis was on the same ship and they became pals as shipmates, pleasing Arnold quite a lot. Unfortunately, British society was only stiffly polite to them, and many did not trouble to conceal their disdain for traitors to any cause, and thus life in England was not smooth. By that time, it is possible that many had begun to suspect the whole idea of treason was Peggy's idea from the start, as is today the conventional view of it. As an American aristocrat, she was uncomfortable with the rebels in Philadelphia, and as the impetuous wife of an accused smuggler, it was difficult to fit in with either the Quakers or the merchants with loyalist leanings. No doubt she heard some catty whisperings among her friends and relatives about her other romantic associations. The British paid them their promised pensions, but a career in the British Army was out of the question for her husband. But the real shock would come, from discovering the British as a whole didn't much care for their behavior, either.

Canada's Southern Seaport

|

| Global Warming, soon? |

When American railroading fell apart in 1970, the remnants were gathered into a financially failing passenger network, Amtrak, and in 1974 a prospering freight division, Conrail. Although prosperous enough, Conrail has remained largely invisible to the urban public, often moving trains only at night so the tracks could be used for passengers during the day. When Conrail got efficient enough, it was sold off in pieces, then largely disappeared from public attention. But Philadelphia had ended up with two freight railroads owned by Canadians displaying a great deal of imagination and vigor, investing huge amounts of money in the transportation revolution which includes container cargo and automated handling methods. And which does its best to avoid featherbedding unions, longshore pilferage, damage suits, inflated Workman's Compensation costs, and crooked politicians. All of these man-made obstacles to the efficiency of course hotly deny they were responsible for the wreck of the railroads, but now that they have been tamed, the recent recovery in the transportation industry suggests these factors really must have had a lot to do with creating the problems. Of course, the fundamental difficulty was railroad overbuilding during their long period of a transportation monopoly. A measured description would be that union intransigence did not exactly cause the bankruptcies, but resisted correcting it until bankruptcy was the only way out. The underlying disruption was the massive oversupply of rail transport created by highway and airline competition. There might have been other less destructive ways for the railroads to downsize gradually, but bankruptcy courts could at least set aside union work rules without paralyzing the rest of the country. In retrospect, the depression of the 1930s, World War II and the Korean War also contributed considerably to wasting time needed to reorganize railroad oversupply gracefully. And finally, it is very difficult to convince people of something they don't want to believe. The union leadership exaggerated but probably did believe much of their own rhetoric about fairness and management incompetence and greed. The bankruptcy did not settle those assertions at all. What it did settle was that excessive labor costs had indeed been ruinous, and that relief from them did indeed permit a remarkable rebound of profitability and efficiency under largely the same managers who had previously seemed so woebegone.

During all the strife and turmoil, no one thought very much about Canada, but now Canada seems a big part of our transportation future. Philadelphia discovered it had ended up with, not one but two Canadian rail systems. Freight trains now run almost exclusively at night so most Philadelphians would deny it if asked. Philadelphia's local labor and political problems have seemed to improve enough to persuade Canadian shippers to send what is currently 25% of the port's cargo through our system. So nowadays when Canadians come to town with big plans, a chastened city government is eager to appear helpful. The situation is greatly helped by the Canadian dollar currently trading at 88 American cents, and by having almost twenty non-stop flights to Canadian destinations originating daily at Philadelphia International Airport.

The first thing to notice is that the Canadians are eager to promote the deepening of the river, and have apparently been able to apply some useful pressure to the main opponents of Delaware port deepening, in the New Jersey legislature. The Canadians seem to be toying with two major ideas. They have considered making Philadelphia into Canada's Atlantic port, as the eastern terminus of a freight link from Philadelphia to Vancouver on the Pacific Ocean. It would seem that container ships are getting longer and fatter, making it more attractive to deepen the Delaware than widen the Panama Canal. And quicker, possibly even cheaper, to ship from Rotterdam to Yokohama by way of Marcus Hook, with portage service from Philadelphia to Vancouver.

Well, that's one idea, maybe not a likely one. A more modest idea is to make Philadelphia into Canada's southern port, with cargo going from Philadelphia to Kingston, Ontario. That's at the western end of the St. Lawrence River, and the eastern end of the Great Lakes. In all planning about cargo transportation, the vital issue is to have some cargo for the return voyage to keep trains and ships busy in both directions of a round trip. A busy freight-forwarding operation between Philadelphia and Kingston could gather cargo coming in along the St. Lawrence, plus the other, Midwest, direction, exchanging it for cargo going to South America and Africa -- by way of Philadelphia. Bigger visions of huge container ships coming up Delaware from India, sending cargo to Hong Kong by way of Ontario, could possibly be considered in the future if basic infrastructure is created for shorter traffic runs.

The whole thing brings back some history of the American Revolution. Times have changed, but geography is the same. If you extend Broad Street due north for four hundred miles, you come pretty close to Kingston, Ontario. That's at the western end of the Thousand Islands, a peculiar collection of channels and islands at the junction of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. Right now, Kingston thrives on charming summer vacationers, particularly those who like boating, fishing and sailing.

|

| General John Sullivan |

But at least half of the families in Kingston are said to have Philadelphia connections. If you go back to 1775 when war clouds were gathering, a lot of Philadelphians were royalists, and many more were pacifist Quakers. When revolutionary rioting and intimidation started to get serious, a great many British sympathizers packed up their goods and traveled out Ridge Avenue to Plymouth Meeting. From there they either went along the upper Delaware River or else followed what is essentially the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Up to the East Branch of the Susquehanna River to Binghamton, and across New York State to Kingston. That was Iroquois territory, with hostile French-speaking Indians to the west and friendly English-speaking Indians to the east (the Revolutionaries perceived the friendliness reversed), and the trip for the exiles must not have been completely care-free. Later on, this area was to be the scene of many "Indian" massacres, egged on by both sides of the revolution, and was on the edge of the eventually decisive battle of Saratoga. In 1777, George Washington dispatched General John Sullivan from Valley Forge to conquer the Iroquois, which Sullivan eventually did by burning crops and villages, essentially starving the Iroquois into near-extinction. When the Philadelphia Tories settled down at Kingston they intended just to hide out for the duration of the war, but events made it unsafe to return for many years, and the War of 1812 (largely fought in this area) finally made them realize they were Canadians permanently. Indeed, it was the Philadelphia-Kingston settlers who prompted the creation of the Canadian nation.

These families retained many relatives in Philadelphia, however, and a good many contested property claims. Vacationing created another reason to maintain connections between the two areas, and the affinities have remained strong. Meanwhile, immigration from non-Caucasian countries of the British Commonwealth has made Canada far less British than it once seemed, while anti-British sentiment in Philadelphia is now hard to find. With these strange connections and even stranger historical quirks, the sentiment in Canada to rejoin America is clearly growing. It's only a fireside chat, at the moment, but it's a movement worthy of a little noticing.

If you would like to review this backwoods trail of tears, fire up Google Earth and put Philadelphia as the origin and Kingston Ontario as the destination under the Directions tab. Then push the triangular button called Play Tour (under Places), and sit back for a fifteen-minute travelogue of the journey, as presently viewable at a virtual height of a mile. The trip over the Lehigh tunnel is particularly exciting.

A curious footnote to the curious friction between Philadelphia and Boston, old towns so alike in many other ways, seems somehow related to this episode. Pennsylvanians had trouble understanding why the New Englanders were so upset at the British; what was the problem at Lexington and Concord, anyway? The story of the Continental Congress was largely one of New England trying to get the rest of the colonies to help them fight the British. But only twenty-odd years later, New England was seriously considering secession from America rather than fight the British in the War of 1812. Several generations still later, the descendants of Philadelphia loyalists in Kingston have trouble explaining all this, but suspicion remains that the ancient affinity between Philadelphia and Kingston has something to do with it.

Lansdowne

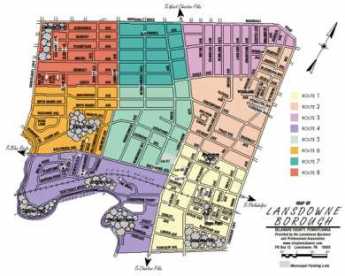

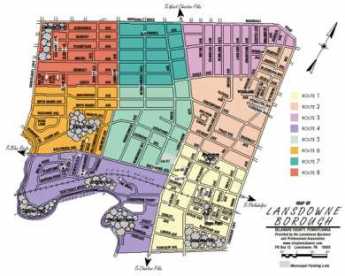

|

| Lansdowne Map |

The Granville, or Lansdowne, the family had so many members important in English history, that the Lansdowne name adorns countless schools, boroughs, colleges, museums and other monuments around the former British empire. It would require undue effort to sort out just why each memorial is named after just which member of the family. In the Philadelphia region, Lansdowne is the name of a small borough in Delaware County,

|

| Lansdale |

often annoyingly confused with Lansdale, a small borough in Montgomery County. However, it really seems more appropriate to focus reverence on the Lansdowne mansion, which from 1773 to 1795 was the home in now Fairmount Park of the last colonial Governor. That would have been John Penn, who was one of several Penns who still shared the Proprietorship until 1789, and who shared in the miserly payment which the Legislature of the new Commonwealth made as compensation for expropriating twenty-five million acres of their property. The French Revolution was going on at that time, so there were probably some patriots who would scoff that John Penn was lucky not to be guillotined.

The Penn family could see the Revolution coming, and like everyone else was uncertain who would win. Real decision-making for the Proprietorship rested with Thomas Penn in London, a close friend of the King and his ministers. The strategy employed in this difficult situation was to surrender the right to govern the colony conferred by its original charter and to become mere real estate owners with John their local representative pledging local allegiance. That might have worked for a while, until General Howe's troops captured Philadelphia. Soldiers were dispatched to Lansdowne to tell John Penn he was under detention, to reduce his potential utility to the occupying army.

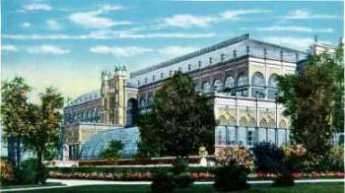

|

| Horticultural Hall |

As matters eventually worked out, some of the Penn descendants remained fairly wealthy after the Revolution, especially those whose wives had inherited substantial assets from other sources. But some were severely impoverished. The stately Georgian mansion burned down in 1854, and the site was then occupied by the Horticultural Hall of the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Perhaps because of misplaced patriotic fervor, it is now difficult to find a picture of Lansdowne.

The elegance of the place, on 140 acres, is suggested by the fact that William Bingham the richest man in America at the time, apparently acquired it from James Greenleaf the partner of Robert Morris, and the nephew by marriage of John Penn, who acquired it from Penn's estate but probably had to give it up in the financial disasters of Morris and his firm. Lansdowne was still a grand manner when it was briefly acquired by Joseph Bonaparte, the former King of Spain. In view of the fact that Bingham had provided President Jefferson with the gold to finance the Louisiana Purchase from Napoleon Bonaparte, and earlier had practically forced the Congress to call off an impending war with France, there was likely a connection here.

And to some extent, the ill-treatment which John Penn received from the Pennsylvania legislature (roughly fifteen cents an acre) in the Divestment Act of 1779 can possibly be traced to the unrelenting hatred by Benjamin Franklin, Pennsylvania's icon. History does not tell us what made these two former friends fall out in 1754, sufficient to make Franklin willing to spend years in London trying to get the colony away from the Penns. The feeling was surely mutual. When John Penn was offered the patronship of the American Philosophical Society, he declined, just because Franklin was its president. In retrospect, that sounds unwise.

Kingston: Birthplace of Canada

John A. Macdonald was a sweet, hard-working lawyer in Kingston, whose wife died young of tuberculosis. After she was gone, he devoted his life to achieving the modern Canadian government, which finally came about in 1867. He was the first Prime Minister, sort of the George Washington of Canada.

His home for several decades was a small farm near the center of town, because he wanted peace and quiet with his wife, raising his own vegetables, eating fruit from his own orchard. At least to the extent, Canadians go in for that sort of thing, his home has the beginnings of a national shrine for Canada, but he was said to be whimsical about the somewhat incongruous Italianate architecture which must nevertheless be admired for its comfortable design. The charming ladies of the city serve high tea in the afternoon to well-mannered visitors, in rather startling contrast to the tomb-like atmosphere which surrounds most such national shrines. They are anxious to please but respond to questions about the Tories of 1776 Philadelphia with the blankest of stares. Unless they are uncharacteristically evasive, they know absolutely nothing about any Kingston history before 1867. Their parents may well believe this is a sensitive topic best avoided in polite company, but at least the present generation appears to have been taught nothing, as a safeguard against rude encounters. Although half of the town is descended from Philadelphia Tories, they do not know what a Quaker meeting is, and do not believe Kingston has one. Touring around town, there is a short row of low brick houses which may have been built in Georgian style, but are now unoccupied, and that's about all there is left to suggest that episode. We're not Tories, but we aren't Americans, either.

|

| John A. MacDonald House |

Riding around town, a striking number of buildings are built of granite-looking (but actually limestone) blocks. There's probably a quarry nearby, but the effect is pretty somber. In the governmental center of town, building after building is built in the same heavy style of the same grey stone. In fact, the most prominent building in the center of town is the penitentiary at Riverside, looking as though it was meant to demonstrate what heavy stone blocks were really supposed to be used for. Perhaps it evokes the image of a fortress since memories of U.S. invasions in 1775, 1812, and 1838 are surely still alive somewhere. But unspoken, please don't speak of it.

The ride on the wide highway back to the International Bridge seems to take a long time because there is so little to notice. But things immediately get pepper on the other side. That seems to be the way both sides like it.

The Heirs of William Penn

|

| William Penn |

Freedom of religion includes the right to join some other religion than the one your father founded; William Penn's descendants had every right to become members of the Anglican church. It may even have been a wise move for them, in view of their need to maintain good relations with the British Monarch. But religious conversion cost the Penn family the automatic political allegiance of the Quakers dominating their colony. Not much has come down to us showing the Pennsylvania Quakers bitterly resenting their desertion, but it would be remarkable if at least some ardent Quakers did not feel that way. It certainly confuses history students, when they read that the Quakers of Pennsylvania were often rebellious about the rule of the Penn family.

|

| Delaware |

Such resentments probably accelerated but do not completely explain the growing restlessness between the tenants and the landlords. The terms of the Charter gave the Penns ownership of the land from the Delaware River to five degrees west of the river -- providing they could maintain order there. King Charles was happy to be freed of the expense of policing this wilderness, and to be paid for it, to be freed of obligation to Admiral Penn who greatly assisted his return to the throne, and to have a place to be rid of a large number of English Dissenters. The Penns were, in effect, vassal kings of a subkingdom larger than England itself. However, they behaved in what would now be considered an entirely businesslike arrangement. They bought their land, fair and square, purchased it a second or even third time from the local Indians, and refused to permit settlement until the Indians were satisfied. They skillfully negotiated border disputes with their neighbors without resorting to armed force, while employing great skill in the English Court on behalf of the settlers on their land. They provided benign oversight of the influx of huge numbers of settlers from various regions and nations, wisely and shrewdly managing a host of petty problems with the demonstration that peace led to prosperity, and that reasonableness could cope with ignorance and violence. When revolution changed the government and all the rules, they coped with the difficulties as well as anyone in history had done, and better than most. In retrospect, most of the violent criticism they engendered at the time, seems pretty unfair.

|

| John Penn |

They wanted to sell off their land as fast as they could at a fair price. They did not seek power, and in fact surrendered the right to govern the colony to the purchasers of the first five million acres, in return for being allowed to become private citizens selling off the remaining twenty-five million. Ultimately in 1789, they were forced to accept the sacrifice price of fifteen cents an acre. Aside from a few serious mistakes at the Council of Albany by a rather young John Penn, they treated the settlers honorably and did not deserve the treatment or the epithets they received in return. The main accusation made against them was that they were only interested in selling their land. Their main defense was they were only interested in selling their land.

As time has passed, their reputation has repaired itself, and they bask in the universal gratitude which is directed to their grandfather and father, William Penn. Statues and nameplates abound. Nobody who attacked them at the time appears to have been really serious about it, except one. Except for Benjamin Franklin, who turned from being their close friend to being their bitter enemy. Franklin tried to destroy the Penns, traveled to England to do it, and after twenty years seemed just as bitter as ever. Something really bad happened between them in 1754, and neither the Penns nor Franklin has been open about what it was.

Addressing The Proprietors' Dilemma

|

| William Penn |

DURING the century which elapsed after Charles II gave away Pennsylvania to William Penn, several hundred thousand people moved in and changed the place. Transformation of the wilderness explains why the terms of the grant seemed logical at one time, but proved almost impossible to manage at the time of the Revolution. The Penns with thirty million acres was the largest landholders in America but, in fact, by 1776 only five million acres had been sold in a century. The land they held was simply too much for one family to handle without an army, and although the original settlers were pacifists, the later ones were combative.

Charles II had written in the Charter that the Penns could have the land if they could maintain order there, retaining the legal right for the King to recover the land if they didn't. This fall-back provision certainly reflects some doubt about the ability of pacifists to shoot the necessary number of Indians, Frenchmen, and Spaniards. On the other hand, the motive for a King delegating away his authority in the first place became clearer when the Penns experienced severe financial strain defending the Northeast corner of the state against the Connecticut invaders. It furthermore helps us understand why Benjamin Franklin received such a cold reception when he was sent to London by the colonists to request the crown to reassert civil authority over the state. That did not necessarily imply stripping the Penns of their land; by this time, it was clear that the Penn Proprietors were mainly interested in selling it to someone. The charter of the King's grant included the offer to make William Penn a King; and although the offer was declined, the Penn Proprietors retained some degree of legal power to govern the territory. Franklin for all his persuasive power was, unfortunately, the one man Thomas Penn didn't want to see, because of the threat he had posed by raising a militia in King George's War, and later his expansiveness at the Albany Conference. And Thomas was a good friend of the King. The King didn't want these problems and particularly didn't want the expense. Ambiguities were, of course, shared all around. William Penn had quite shrewdly seen it was more sensible to treat the Indians decently than to fight with them, and cheaper too; the lesson was not lost on the British crown. But the French Kings posed a much larger world-wide threat to the British colony, finding for their part, it was rather economical to supply munitions to the Indians on the frontier and stir them up emotionally. The French and Indian War was a small component of the Seven Years War, which proved to be a costly adventure for both sides. Its local cost certainly overwhelmed the ability of one family to underwrite local governance in a large wartime colony, and it jeopardized the finances of the British Monarch to carry the rest. The resulting need to tax the colonies for their defense sent things downhill, eventually to the Stamp Act, the Townshend duties, and the Tea Tax. Everyone made lots of mistakes as the whole structure underwent revision, just as pacifists are certain will happen in any war. But when a pacifist utopian colony was prospering while successfully dealing with the Indians, it's all sort of a big pity.

|

| Thomas Penn |

With much to lose, the Penn family did pretty well with the resources at hand. By the time of the Revolution, three generations of Penns had divided up ownership shares of the Proprietorship. When French and Spanish ships were marauding the Delaware River, Benjamin Franklin the local printer took it on himself to organize a militia which persists today as the Pennsylvania National Guard, the Twenty-eighth Division. Franklin was suddenly a local hero to everyone, except to one man, Thomas Penn. Thomas was the dominant figure in the Penn family for many years and worried deeply about Franklin, a man who could stir up ten thousand armed volunteers with a poster proclamation. Such a man could mean trouble, as indeed events later proved to be the case.

John Penn was the Governor of the state, residing in his mansion on the Schuylkill called Lansdowne, doing his best to ingratiate the locals. He struggled to be diplomatic when arguing for the decisions actually made by his Uncle Thomas in London. Thomas Penn, on the other hand, was an important friend of the British Ministry, and a notable person in aristocratic England. As the Revolutionary War approached, the problem transformed into how to hold on to 25 million unsold acres, while remaining unsure who was going to win the impending war.

|

| John Penn |

The strategy the Penns adopted was to get out of the business of running a local government, as Franklin had proposed but in a different way. John Penn the Governor became a private citizen, just a local real estate agent. He took an oath of allegiance to the Revolutionary government, which in the chaos of the time was equivalent to becoming an American citizen. Meanwhile, other members of the family remained in England, ready to revise the arrangement if the British won the war. It was all fairly transparent straddling of the issues, which was only even remotely likely to be effective because of the enormous store of Penn goodwill built up over a century. In 1789 revolutionary France, for example, such sentimentality would not have delayed the tumbrels to the guillotine for five minutes.

Meanwhile, an unexpected difficulty was created. By withdrawing from control of the local government, the Penn family also withdrew from the defense of state borders against neighboring colonies. Under the circumstances, the Penns were afraid to appeal to the King, while the new government of Pennsylvania found the Articles of Confederation were merely a wartime tribal compact. The Articles stabilized boundaries mainly for the purpose of conducting a united war, and did not seriously contemplate a continuing judicial role for disputes between colonies. When the Revolution was finally over, the Penn Proprietors were not left with much of a bargaining position. The new State of Pennsylvania offered, and they accepted, about fifteen cents an acre to surrender their claims. In Delaware, they got essentially nothing for those three counties. Only in New Jersey did the Proprietors' claims remain durable after the new nation was established. The Proprietorship of East Jersey survived into the late 20th century, and the Proprietorship of West Jersey continues to return a small profit even today. The New Jersey curiosity is treated in a separate essay.

Grand Union

|

| Grand Union Flag |

THERE are a number of supermarkets in Philadelphia called Grand Union Stores, but the grocery conglomerate was founded in 1872. That Union was the Northern side in The American Civil War, and it is reported that life-sized replicas of Abraham Lincoln were once a common feature in the stores. Much earlier than that, the Grand Union was a term that meant the first American national flag, adopted in 1775, and created by a Philadelphia milliner, Margaret Manny. It was, however, quite similar to the flag of the British East India Company, and the Grand Union they were both talking about was the Union of England and Scotland of 1707. The jack of the Grand Union flag, soon to be replaced with a ring of thirteen stars, represented the crosses of England and Scotland, superimposed. When Northern Ireland joined the United Kingdom, the cross of Ireland was superimposed, to give the present form of the Union Jack. In 1775, the considerable colonial sentiment still hoped that hostilities would achieve a status for America along the lines of the other members of the United Kingdom.

|

| "Betsy Ross" Flag |

Although the number of stripes in the national flag briefly increased to fifteen at the time of admission of Kentucky and Vermont, stripes soon reverted to thirteen to symbolize the original thirteen states. After that single exception, only the stars in the jack increased to match the number of current states.

The early use of the Grand Union Flag is in some dispute, but it may possibly have been used by George Washington in the various battles around Boston and Charlestown. It was most certainly flown by John Paul Jones on his ship the Alfred . Because of its resemblance to the flag of the nation we were fighting to overthrow, it is understandable that there would soon be a desire to change it. That is what happened in 1777, although just who first had the idea is still open to dispute and myth-making.

America has had three flag acts:

The Flag Act of June 14, 1777 was passed by the Second Continental Congress (under the Articles of Confederation, of course. June 14 is now called Flag Day.) "Resolved, That the flag of the United States be made of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new Constellation."

The Flag Act of January 13, 1794 (1 Stat. 341) An Act making an alteration in the Flag of the United States. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress Assembled, That from and after the first day of May, Anno Domini, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-five, the flag of the United States, be fifteen stripes alternate red and white. That the Union be fifteen stars, white in a blue field.

The Flag Act of April 4, 1818 (3 Stat. 415) An Act to establish the flag of the United States. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America, in Congress Assembled, That from and after the fourth day of July next, the flag of the United States be thirteen horizontal stripes, alternate red and white: that the union be twenty stars, white in a blue field. And be it further enacted, That on the admission of every new state into the Union, one star be added to the union of the flag; and that such addition shall take effect of the fourth day of July then next succeeding such admission.

Thousand Islands: U.S. Side

|

| Thousand Islands International Bridge |

Not counting summer tourists, the New York State lake towns of Sackets Harbor, Clayton, and Alexandria Bay have each about a thousand permanent residents, and all got started by the events surrounding the War of 1812. But Sackets Harbor attracts tourists interested in Upper New York State, Alexandria Bay attracts tourists to the Thousand Islands and soldiers on leave from Fort Drum, while Clayton is mostly content to be the commercial center of this little region. Yes, Clayton has a small obscure sign saying a battle of the War of 1812 was fought there, but mostly it tends to the town needs of the permanent residents of the region. It seems to have a fair number of summer homes of non-residents, but comparatively few tourists. Sackets Harbor we have described elsewhere, mostly servicing a group of people who drive there repeatedly for a sailing vacation. Alexandria Bay, on the other hand, is crowded with throngs of day-trippers and souvenir buyers, serviced by merchants who look as though they spend their own winters in Florida. As an almost inevitable consequence, Alexandria Bay alone has a section of dilapidation next to the center of town, which somewhat resembles Atlantic City in 1940. Just what caused these two originally identical towns to veer in such different directions, must be left to sociologists. The International Bridge certainly changed things, but it is equidistant between Clayton and Alexandria Bay. Things certainly could have taken a different direction; a ferry ride to Boldt Castle of 120 rooms is one of the main tourist attractions. Boldt Castle was built by a Philadelphian for his wife but never finished after her premature death. George C. Boldt was a Prussian who achieved early fame as the manager of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, inventing the Thousand Island dressing for the Waldorf salad. He then built the Bellevue Hotel on Broad Street. Other castles in the Islands were planned, smaller castles were even built on the Thousand Islands (actually, about 1,700 islands by some style of counting). The grave robbers of Skull and Bones are rumored to have a summer place in the region. The St. Lawrence Seaway is open, but mostly benefits Toronto and points West. It snows a lot in the winter.

|

| The War 1812 |

One turns to history to explain anomalies in this border region and gets the idea that both countries would rather you didn't go too deeply into that. A strong tip come comes from the yearly celebration in early August, of the exploits of "Pirate Bill" Johnston. Now, everyone understands that there is a very fluid distinction between a pirate, a smuggler, and a privateer. Behind that is the history that Loyalists from Philadelphia flocked here during the Revolutionary War, and mostly their families continue to live in Kingston. The War of 1812 started out being neglected by England because of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe but contained a very real element of American exceptionalism which was emboldened to aspire to annex Canada. In 1838 an uprising in Canada led by the former mayor of Toronto Mackenzie attempted to revolt against the Crown, American-style, waving the flag of republicanism as contrasted with Church of England feudalism. Mackenzie lost, but not without significant help and sanctuary from the American side of the border, in the universal style of all guerilla uprisings. The American government came to its senses and joined with its Canadian neighbor government in suppressing the revolt, and the Canadians came to their senses and formed a new republic under MacDonald, starting in 1848 and finally achieving it in 1867. Essentially, some Tories from Philadelphia wanted to live in a monarchy in Canada, while some Whigs or republicans in Ontario wanted to live in a republic like the U.S., Yes, there had been the talk of secession or annexation, but mostly the argument was over the style of government rather than its headquarters. Since that time, anyone who brings up the subject is treated as though he had burped at the dinner table.

|

| Thousand Island Park |

In this context, facts are probably somewhat suppressed. Pirate Bill Johnston was descended from Loyalists who had fled to Kingston during our Revolution, but apparently developed republican leanings in the War of 1812 and moved to the U.S. side of the border, either after or as part of a smuggling career among the islands. When M.H. Mackenzie began a Canadian revolt in 1837 against what he saw as the feudal English rule, Pirate Bill came out of retirement and fought with him, mainly employing a skiff rowed by six oarsmen that could slip between islands, and in a pinch could be carried across the land to another river channel. In his most notorious exploit, Pirate Bill attempted to capture a riverboat called the John Peel but was forced to sink it. As part of a broader effort by the American government to quiet this whole uproar down, Johnston was fully pardoned by President William Henry Harrison. The August celebration in Alexandria Bay is apparently run by non-historians, who add a number of anecdotes to the story, of dubious authenticity. The aphorism which the Pirate Bill story brings to mind is that "Where you stand, has a lot to do with where you sit."

| Posted by: htowngenie | Oct 8, 2015 3:06 PM |

| Posted by: Joseph Stalnaker | Oct 24, 2013 8:26 PM |

| Posted by: amberr | Oct 4, 2011 8:19 PM |

| Posted by: Caiya | Jul 30, 2011 10:55 AM |

| Posted by: Stretch | Jul 29, 2011 1:43 AM |

| Posted by: brook | May 27, 2008 8:09 PM |

| Posted by: broooks | May 15, 2008 8:27 PM |

13 Blogs

Pembertons

One of the oldest, most prominent Quaker families contained a multitude of famous, rich, distinguished leaders. Many suffered imprisonment or exile for their pacifism, but one Pemberton is the highest-ranking wartime general buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. He was a Confederate.

One of the oldest, most prominent Quaker families contained a multitude of famous, rich, distinguished leaders. Many suffered imprisonment or exile for their pacifism, but one Pemberton is the highest-ranking wartime general buried in Laurel Hill Cemetery. He was a Confederate.

William Allen, Tory

History is written by the victors, so the rich Tory William Allen is largely forgotten. But he was Chief Justice, probably the richest man in the colony, the son in law of Andrew Hamilton and the father in law of John Penn, the Proprietor, and Governor.

History is written by the victors, so the rich Tory William Allen is largely forgotten. But he was Chief Justice, probably the richest man in the colony, the son in law of Andrew Hamilton and the father in law of John Penn, the Proprietor, and Governor.

Meschianza

The Wyoming Massacre of July 3, 1778

As the dominant Indian Tribe in Eastern America, the Iroquois were ruthless in war. Whether egged on by the British or for their own reasons, in 1778 they remorselessly wiped out the Connecticut settlers around Wilkes-Barre.

As the dominant Indian Tribe in Eastern America, the Iroquois were ruthless in war. Whether egged on by the British or for their own reasons, in 1778 they remorselessly wiped out the Connecticut settlers around Wilkes-Barre.

Perth Amboy Revisited

Perth Amboy was once the capital of New Jersey and the entry point of General Howe's invasion of the rebellious colonies. Except for one old building, you might never guess.

Perth Amboy was once the capital of New Jersey and the entry point of General Howe's invasion of the rebellious colonies. Except for one old building, you might never guess.

Peggy Shippen and Benedict Arnold: Fallen Idols

The hero of the Battle of Saratoga married the Queen of Philadelphia society, but then betrayed the country.

The hero of the Battle of Saratoga married the Queen of Philadelphia society, but then betrayed the country.

Canada's Southern Seaport

Railroading was once the heart of the Philadelphia industrial empire, and it's a little disheartening to see that Canada is taking us over. But historic ties to Canada are particularly strong here.

Railroading was once the heart of the Philadelphia industrial empire, and it's a little disheartening to see that Canada is taking us over. But historic ties to Canada are particularly strong here.

Lansdowne

John Penn, the last of the Penn Proprietors, lived in a mansion near what is now Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park.

John Penn, the last of the Penn Proprietors, lived in a mansion near what is now Horticultural Hall in Fairmount Park.

Kingston: Birthplace of Canada

Kingston is where modern Canada began. Sadly, the capital has moved upstream to Ottawa, and commerce has migrated downstream to Toronto. It has the air of genteel poverty while looking prosperous.

Kingston is where modern Canada began. Sadly, the capital has moved upstream to Ottawa, and commerce has migrated downstream to Toronto. It has the air of genteel poverty while looking prosperous.

The Heirs of William Penn

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

The death of William Penn left his heirs the largest land holdings in America. Although they managed it fairly well, it proved to be more than a single family could cope with.

Addressing The Proprietors' Dilemma

King Charles II gave Pennsylvania to William Penn on condition he defends the place and fuss with neighboring states about its boundaries. A century later, it proved more than a private citizen could handle.

King Charles II gave Pennsylvania to William Penn on condition he defends the place and fuss with neighboring states about its boundaries. A century later, it proved more than a private citizen could handle.

Grand Union

Thirteen stars and stripes became the National Flag in 1777, but a rather similar flag was the National flag from 1775-1777. It was also designed by a Philadelphia milliner, Margaret Manny.

Thirteen stars and stripes became the National Flag in 1777, but a rather similar flag was the National flag from 1775-1777. It was also designed by a Philadelphia milliner, Margaret Manny.

Thousand Islands: U.S. Side

The Lake Ontario towns of Sackets Harbor, Clayton, and Alexandria Bay is about the same size, had much the same early history, but are demonstrating quite a different present and future direction.

The Lake Ontario towns of Sackets Harbor, Clayton, and Alexandria Bay is about the same size, had much the same early history, but are demonstrating quite a different present and future direction.