1 Volumes

Regional Overview: The Sights of the City, Loosely Defined

Philadelphia,defined here as the Quaker region of three formerly Quaker states, contains an astonishing number of interesting places to visit. Three centuries of history leave their marks everywhere. Begin by understanding that William Penn was the largest private landholder in history, and he owned all of it.

Conventions and Convention Centers

When you have a big convention center, some circus is always coming to town. Philadelphia has always been a convention town, has had and still has lots of convention sites, and hopes to have more of the kind of famous convention we have had in the past.

Barbarians At the Gates of the Magical Kingdom

|

| Mickey Mouse |

The Walt Disney Corporation held its annual stockholder meeting on March 3, 2004, in Philadelphia's Convention Center. There were only five items of business: the re-election of directors (no names on the ballot in opposition), re-appointment of the auditors ( reappointed every year for twenty-eight previous years), and three stockholder proposals ( overwhelmingly defeated several times in the past). Typical stockholder meetings leisurely dispose of such an agenda in about twenty minutes. This one took seven hours.

There could well have been two unstated reasons for the protracted meeting. The first would be self-inflicted: direct advertising to thousands of small stockholders at an entertainment, including costumed cartoon characters, movie excerpts promoting coming attractions, and a chance at the microphone to tell the world who you are and what you think. Such promotion is even more effective if the meeting city shifts each year.

This year it was Philadelphia's turn to see the sights, including top executives in new suits and Ronald-Reagan shirt collars. Several thousand true believers in the American Dream did show up, many of them bringing little children, taking almost three hours to get through an airport-like electronic frisking by four harried security guards. The guards seemed particularly concerned to prevent live cell phones from entering the meeting.

Secondly, the meeting gave all the signs of a covert filibuster. It even had a professional: Senator George Mitchell, the former Democratic majority leader of the U.S. Senate, was on hand to advise. After all, a frivolously protracted meeting is collapsible if discussions get out of hand, because the audience has already become impatient. Comcast, with corporate headquarters only three blocks from this Convention Center, had an active offer to acquire Disney, instantly rejected by the Disney board. As soon as the offer was announced, the price of Disney stock jumped four dollars a share, enriching every shareholder in the room a collective $8 billion. Why not accept it? The new price now made the offer seem too low, by some perplexing reasoning. Allowing a succession of irrelevant speeches positions the chairman of the meeting to smother, in the interest of fairness to all, and gathering momentum for Comcast. In the event, it did actually delay this meeting's announcement of voting outcome, which was called for 8 AM, until past the close of the New York Stock Exchange in the late afternoon. Meanwhile, the message was encouraged that love of cartoons, wholesome television, and family vacations was more appealing to true stakeholders of Disney than vertical integration and short-term (read, short-sighted) profits.

|

| Michael Eisner |

It didn't go that way; hardly a word was said about Comcast. Instead, the true believers, led by the nephew of Walt Disney, made it clear that they were turned off by speeches filled with business school lingo, like enhancing the brand, protecting the franchise, and growing the business. They didn't understand all that, but they did understand that the American heartland was being asked to pay eight and nine-figure incomes, year after year, to people who obviously worshiped in the financial cultures of the East and West coasts. The most telling remark was that the company had good years and bad years, but Michael Eisner the CEO -- never seemed to have a bad year. Stockholders were urged to withhold their votes from him.

To some extent, any management engaged in a proxy battle has some justification for limiting the attendance at a stockholders meeting, because arbitragers will almost always try to support a hostile proposal. Stockholders who bought their shares a few days before the vote have interests which conflict with the long-term stockholders since a short term jump in stock price will probably evaporate if the proposal is defeated. Many of the people in the audience are only there to assess whether the proposal is likely to be successful, so as to buy more shares or sell what they have; some of the people at the microphone are potentially interested only in misleading these observers. The wise guys in the audience were agreed that Comcast had made a mistake announcing its offer after the date had passed when newly-purchased shares were eligible to vote.

In the end, over a thousand people stuck it out to hear the ballot results. After seven hours, someone moved for adjournment, the chairman heard a second, a scattering of eyes followed, and he never called for the nays. He was half-way to the door when a thousand howls were raised, demanding the results of the vote. Oops, sorry. An accountant was summoned to drone out interminable numbers, one by one. It seems that seven hundred million shares had withheld approval from the CEO, 43% of the votes cast. Mr. Eisner, to his credit, didn't show a flicker of emotion on his televised face, and duly announced that all directors had been re-elected, the auditors re-appointed, and the stockholder resolutions defeated. Maybe so, but at the board reorganization meeting which followed, Eisner was removed from the Chairmanship although retained as CEO. The more logical person to defend the Magic Kingdom against predator Comcast was Roy Disney, of course, but to appoint management's public enemy would have been a bit much. Almost all of the board had themselves experienced at least 200 million votes withheld.

|

| Ned Johnson |

The real governance crisis which this carnival dramatizes was not mentioned. With nearly two billion shares outstanding, at $26 a share this company is valued at $52 billion. There were people at the microphone who owned 200,000 shares, but even their economic power is negligible in a corporation so large. It is the managers of mutual funds and pension funds who now control big-corporation voting, and have the real power to decide on mergers and take-overs. Mutual funds and pension funds, like Ned Johnson at Fidelity who controls a trillion dollars of various stocks, are the ones with the votes. In the past, such managers have found it a bore to address five hundred or more proxy statements each spring. They find it hard enough to hire analysts who can pick a good company, let alone picking executives to make a bad company into a good one. As fund ownership has spread, however, there is uncomfortably little left to buy if a diversified fund does much selling. Diversification is almost a sure winner; picking executives is too much like picking racehorses.

So, in the end, the restless stockholders were guided by only one perception: Eisner controlled his own pay and took too much for himself. Too much diversification of stock ownership has led to the dispersion of control. And dispersed control has led to control by outcry. Those friends of capitalism who dread government regulation had better rapidly devised some alternatives.

International Visitors Council

|

| Nancy Gilboy |

The President of IVC, Nancy Gilboy, tells us it stands for International Visitors Council, now approaching its 50th anniversary. As you might suppose, it is located at 1515 Arch Street, near the old visitors center. Philadelphia has a new visitors center on 5th Street, of course, and perhaps it takes time to move or maybe moving isn't in the cards. We had another Visitors center on 3rd Street that came and went, so proximity between Center and Council perhaps isn't as important as rental costs, or leases, or other issues.

|

| Philadelphia Art Museum |

The Council has a modest budget, but a great idea. Anyone who has traveled much knows that you tend to follow the travel agent's set agenda for a town, you see a lot of churches and museums, but you can almost never get tickets for the local entertainment events, and you almost never meet any local people except taxi drivers and bellhops. That's even more true of young travelers, who don't have either the money or the experience to anticipate the issue, or enough local friends to guide them around the obstacles (This exhibit closed on Mondays, that event is all sold out, this event was spectacular, you should have been there yesterday, sorry we didn't know you were coming we have a wedding to go to, etc.). On guided tours, it is remarkable how few things seem to happen after 4 PM.

So, fifty years ago, some imaginative Philadelphia leaders got the idea that a lot of Philadelphia residents would enjoy taking some foreign tourists under their wing, maybe have somebody to know when they, in turn, make a reciprocal visit, maybe boast about our town a little. Furthermore, by getting involved with the US State Department, young visitors can be identified as potential future leaders in their country. If the guess is a good one, and the experience favorable, Philadelphia might prosper from the publicity and from the later return visits, now in the triumph of success. That was the founding spirit of the Philadelphia International Visitors Council.

So that's how it came about that Margaret Thatcher, < Tony Blair, the current President of Poland, and the head of the Russian Space Program were once visitors in Philadelphia homes. People who like to do this sort of thing tend to like each other, so the monthly receptions (First Wednesday at the Warwick) are interesting Philadelphia social occasions in their own right. Success begets success, and the CCP (originally Business for Russia) has affiliated itself, along with the Philadelphia Sister Cities Program, the Consular Corps Association, The Philadelphia Trade Association, and probably others.

Look at it from the visitors' viewpoint. New York has larger colonies of foreign nationals than Philadelphia does, but New York is an expensive place to visit. Washington has dozens and dozens of embassies, but a visitor soon learns the last thing an embassy staff wants to see, is a citizen from home. So those places aren't really a typically American place to visit. Indiana is plenty American, but there isn't much to see there. So Philadelphia has many attractions, lots of history, it's as thoroughly American as a city can be, and all it needs is someone to open up and show it to you. Cleverly organized, the IVC has undoubtedly put the Philadelphia stamp on many foreign visitors, without their exactly recognizing they are being told This is America. If the State Department is shrewd in its assessment process, Philadelphia will in time be held in high esteem by the leaders of a lot of foreign nations.

In the spirit of announcing that Philadelphia is where you can find America, my own little daughter astonished me at a dinner party by telling the assembly the following story:" William Penn was nice to the Indians, so it was safe to land in Philadelphia. Pretty soon, so many people landed here they had to move West to settle down. And, folks, that's why the people to the North of us talk funny, and the people to the South of us talk funny -- but everybody else in America talks like Philadelphia!"

Airport Economics

|

| US Airlines |

The Philadelphia Airport is flourishing at the moment. It seems a little noisy as a result of being only seven miles from the center of the city, but it's clean, not terribly expensive, and there are almost enough places to park. A short-term worry is an impending bankruptcy of US Airlines, its biggest tenant, although bankruptcy is recognized as about the only way keen managers can legally correct over-generous union contracts. Perhaps a longer-term worry is that we have no flights to Asia and South America so we will lag other American cities in business relationships with those prospering regions. To more than any other factor, the prosperity of airports can be attributed to their belated awakening to the scarcity value of landing slots. Philadelphia has added forty slots in the past year.

The decline is largely a reflection of the decline of a popular airline concept called Hub and Spokes, in which the airline deliberately breaks a long flight into two pieces, with a change-of-planes at the hub. The approach allows them to use smaller planes, reduces vacant seats, but doubles the number of landings per passenger trip. Passengers don't like to change planes, don't like the baggage mix-ups, don't like the longer flight times, don't like to miss their"connections". Well, as Commodore Vanderbilt said, the public is damned. But airlines better be careful about the airports, because they don't like Hub-and-spokes, either. In an effort to reduce the delays related to more frequent plane switching, the airlines' scheduled arrivals and departures in waves, usually around meal times with the advantage they also don't have to feed you. In their frenzied rush to catch the connecting flight, most passengers are unaware that the airport is dead empty for an hour or two between these waves of landings. Mathematical formulas even suggest it's inevitable, since a plane may not take off until the destination airport clears it, and therefore these waves at the hub are even mysteriously transmitted to less-busy "spoke" airports. The hub system thus provoked inefficient use of the commodity in shortest supply, namely the landing slots. One even suspects that the ripples extend out to state politics, since inland cities like Pittsburgh prosper as hubs, while seacoast "cities of passenger origination" like Philadelphia, suffer. To whatever degree this matter can be affected by regulation, it inevitably has a Harrisburg component, too.

Maybe we ought to get economists interested in devising a general economic principle at work here because a similar phenomenon is visible in at least one other industry. The next time someone tells you a relative has just been released from the hospital, surprise them with this question, "Did he go home on Saturday morning, I suppose?"

Carpenters Hall

|

| Carpenters Hall |

The birthplace of our nation is both smaller than you would expect and larger. The fire marshall now says no more than 83 people may rent it for a sit-down affair, or 103 for a stand-up gathering. However, the internal partitions have been removed from what was once a center-hall building with a meeting room on either side; it now is a large open room in the form of a Greek cross. At the time of the revolution, Benjamin Franklin's Library Company occupied the second floor, so the First Continental Congress had to find a way to do its work in the side rooms of the first floor, to the side of the center hall. There were 53 delegates, and presumably some staff and visitors.

That sounds rather crowded, but it was nevertheless the largest rentable public space in the city. John Adams arrived early for the convention, conniving with several other early arrivals at the City Tavern. Adams made the following notation in his diary: Monday. At ten the delegates all met at the City Tavern and walked to the Carpenters' Hall, where they took a view of the room, and of the chamber where is an excellent library; there is also a long entry where gentlemen may walk, and a convenient chamber opposite to the library. The general cry was, that this was a good room, and the question was put, whether we were satisfied with this room? and it passed in the affirmative." Alternative places to meet would have been in churches, which presented awkwardness, or in the State House (Independence Hall) which was then under the control of Tories.

|

| Continental Congress |

France and the rebellious colonies was a complicated one, with intrigue and mistrust at every turn. One interesting episode had to do with Franklin's library on the second floor. The French ministry had sent over a spy, to size up the colonists before the French risked too much on them. So, the spy was led up to the library and allowed to overhear some bellicose conversations going on downstairs -- thoroughly stage-managed for the benefit of the "hidden" French visitor.

The Carpenters Company was a guild of what we would now call builders and architects, and architects continue to use it. The first floor usually displays a few Windsor chairs dating to the Continental Congress, covered with a rich black patina that really lets you know what a patina was. Upstairs, the staff quarters are now, well, a little on the elegant side so you can't visit. The guild was formed in 1724, and fifty years later had just completed its building, in time for its historic role in 1774.

|

| Elfreth's Alley |

With the whole continent available for building, it is still not entirely clear why Colonial Philadelphia crowded itself into half a square mile, with crowded little row houses on crowded little alleys. But that's the way it was, now visible in the location of Carpenters' Hall down a little cobbled alley, in the center of a block. Elfreth's Alley gives you the same feeling, and perhaps Camac, Mole, and Latimer Streets. Carpenters' is a lovely little place, with lots of interesting features, but the main interest lies in what took place there. For that, you have to read a few books.

Republican Convention in the Wigwam (1860)

There were no Republican National Conventions in Philadelphia between 1856 and 1872, but during this period the town became solidly Republican, and federal political patronage had its biggest impact on the region's economy. Pennsylvania threw the nomination to Lincoln in 1860, and Lincoln paid us back.

The 1860 Convention was held on Wacker Street in Chicago, in a building called the Wigwam. Abraham Lincoln was the favorite son on Illinois, and so his cronies had considerable influence on the convention arrangements. They used this influence, for instance, to counterfeit several hundred tickets of admission to the galleries. The strong favorite to win the nomination was Mr. Seward of New York, and it is fair to say he confidently expected to win. The galleries roared with applause and shouts of approval of any mention of New York, or Seward. On balloting day, the Seward supporters went out into the streets with a joyous noisy parade, which greatly stirred their fervor. However, when they returned to the Wigwam, they found their seats taken by the Illinois supporters of Abraham Lincoln. From that point forward, all mentions of Lincoln, Illinois, or the Great City of Chicago were greeted with thunderous applause and acclamations by the audience.

On the first ballot, as expected, Seward was in the lead,173 votes to Lincoln's 102, followed by about fifty votes each for Simon Cameron (of Pennsylvania), Salmon Chase of Ohio, and Edward Bates of Missouri. Since everyone knows that Lincoln eventually won, we can now look forward to Lincoln's cabinet, which was to contain William Seward as Secretary of State, Bates as Attorney General, Chase as Secretary of the Treasury, and -- Simon Cameron of Pennsylvania as Secretary of War.

The Pennsylvania delegates from Bucks and Chester Counties were than the rest of the state, and privately regarded their favorite son Cameron, as a crook. Having dutifully voted for their favorite son on the first ballot, the Pennsylvania delegation was then free to make deals. As the roll call of the second ballot moved down the line, there was not much changing of votes. The people in the galleries were shouting away as usual, but the delegates were carefully marking their lists with stubby pencils. When the vote came to Pennsylvania, the insiders were electrified with the realization it was all over. Pennsylvania threw essentially all its votes to Lincoln. Ohio and Missouri immediately got the message and stumbled along to climb on the bandwagon. Lincoln was in.

Historians have frequently noted the unexpected upset had a disproportionate effect on Southern opinion -- after all, scarcely any Southern candidates made it even to the first ballot, and no Southern boss was anywhere near the smoke-filled rooms where the leadership settled things while the ordinary delegates were out at parties. Furthermore, it was an anti-slavery sentiment that made Pennsylvania switch.

But somewhat less noted is that the highly political new President soon got a hard-minded new Secretary of War. Cameron wanted, and got, lots of factories to make boots and uniforms, guns and gunpowder, Army depots, Naval Bases -- and so on, and so forth. The Pennsylvania Republican machine was in business for decades to come.

Priceless Art as Mass Entertainment

The Philadelphia Museum of Art recently had a special exhibition of paintings by Edouard Manet, with a heavy dose of Claude Monet plus a few others. A moment's reflection demonstrates the enormous undertaking it must be to assemble a hundred valuable paintings from 60 different museums and owners, arrange for permissions, negotiate insurance and shipping costs, debate the best display, lighting and arrangement, instruct the guides, print the brochures, hype the announcement hype, and probably a thousand other details of making this all come out right. Although a lot cheaper to assemble this show and move it around to various cities, than it would be to have thousands of Americans travel to Europe to see the paintings there, nevertheless it looks expensive. Half a dozen major foundations donated money for this effort, and the ticket price is not insignificant. When you are all done, however, you have seen a display that no one could possibly see privately, all in one afternoon, with an elegant lunch on the premises in air-conditioned splendor, accompanied by a small orchestral group in the background. The show is resident for three months, less two weeks for setup and travel, so four cities can collaborate on four traveling exhibits each year. Somewhere, there must be a very large staff devoting full time to keeping these exhibits in constant movement; probably several cycles are going at once. This is big business, and filling that big museum every day for three months implies that many of the visitors are from outside Philadelphia. After you go, at least you can tell Manet from Monet, you've had a taste of the huge Museum that makes you want to come back some day, and you have seen Philadelphia's best view, right where Rocky ran up the steps.

Our guide was well trained and entertaining, and knew all about horizons, prompting some deep, deep thought about horizons. The Dutch school of painters usually put the horizon down near the bottom of the painting, showing off the billowing grey clouds so characteristic of the European coast near the North Sea. By contrast, the French impressionists went down to the sunny Mediterranean coast, where the bright sunlight forces you to look down at the ground. So the horizon of painting, the line where the sky meets the ground, is low in northern paintings, but high in scenes of the Riviera, representing in both cases the typical viewer?s image of the scene. No doubt, some painters deliberately reversed the normal location of the horizon, in order to create the unconscious effect on the viewer that something was somehow wrong.

This little lesson has practical utility for those of us who take amateur snapshots. The rule for photographers is to throw the horizon into either the top third or the bottom third of the viewfinder. Avoid putting the dumb horizon right in the center of the photo. Since most cameras nowadays have an automatic exposure meter, if you get it wrong the meter will concentrate on the sky, underexpose the subject below the sky, and give you a puzzling black silhouette instead of a picture of your girlfriend.

Returning to the reality of the Art Museum, it sits on top of a little mountain --Fairer Mount-- that William Penn once considered as a place to put his home. It was later the site of a reservoir, with the famous pumping station and water works down the hill on the edge of the Schuylkill. Now, this Parthenon is an easy place to reach and to park, while the world's art is placed before you. The Russian Tsar in his Hermitage, and the Archduke in his Viennese palace never had it as easy as this.

Caesar Rodney Rides Through the Rain

|

| Caesar Rodney |

If you have a quarter minted in 1999, you can see a depiction of Caesar Rodney riding through the rain, mud and heat, all night, to cast his July 2 vote for independence at the 1776 Continental Congress. There are no known painted portraits of Rodney, probably because his face was badly mutilated by cancer which ultimately killed him.

On July 1, Thomas McKean and George Read had split Delaware's votes in a tie, and McKean had urgently sent word to Rodney, the absent third vote, that he must come to Philadelphia quickly. Rodney was suffering from cancer. It may thus have been Thomas McKean's idea to invoke the concepts of the Treaty of Westphalia to escape hanging for armed rebellion, but Ben Franklin seems more likely. Once an idea like that gets started in a gathering, it quickly becomes everyone's idea. But Franklin was the only one to stampede a group and take no credit for doing so.

|

| Rodney |

Schoolchildren in Delaware can be forgiven for asking why Rodney wasn't in Philadelphia for the vote without being sent for. And we don't really know. Rodney certainly had plenty of other things competing for his attention, like being a Supreme Court Justice, the Speaker of the Delaware Assembly and the de facto Governor of the State, as well as being a Brigadier General in the Militia (he later was made Major General in charge of the garrison at Trenton). One has to suspect, however, that he had not expected George Read to vote against independence. Read, after all, had married the widowed sister of George Ross, who did sign the Declaration.

Asthma, a notoriously intermittent condition, may have been a worse impediment to Caesar Rodney's ride than his cancer. Although he was badly disfigured, cancer did not kill him until 1784. The prospect of riding eighty miles in the rain with asthma may well have been the reason Rodney held off until he was absolutely certain his vote was needed. The esteem and affection that Delaware holds for this farmer from Dover can be gauged by the fact that he remained the elected speaker until the day he died, and during his last three months, the legislature held its meetings in his house so he could be present.

What Happened in Philadelphia on July 4, 1776?

|

| Spirit of 76' |

The American colonies were growing too big, too fast, and the British Empire had too many international distractions, to have smooth relationships across three thousand miles of ocean, using uncertain communications available in the late Eighteenth century. Friction and misunderstanding were inevitable without far more statesmanship than either side thought was necessary. So, when the Continental Congress dispatched George Washington to Boston with troops to defend rebellious Massachusetts at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, it was hard for the British to believe the colonists were merely helping out one of their distressed neighbors. It seemed in London that the thirteen colonies had united, formed not only an army but a government, and gone to war. In December 1775 England passed the Prohibitory Act, essentially declaring war, and organized a huge invasion fleet to put down the rebellion. It now seems hard to understand the first notice the Americans had of this huge over-reaction was a private letter to Robert Morris from one of his agents in March 1776; no warnings, no negotiations, no attempt to investigate problems and correct them. The British just sent a fleet to settle this problem, whatever it was. It's all very well to say the Americans should have known they were playing with fire. They didn't see it that way; they were being self-reliant, responding to attack. In June 1776 British patrol frigates were skirmishing in the Delaware River; late in the month, British troops landed on Staten Island. The American reaction to all this was a muddle of confusion. A few were delighted, most of the rest were amazed or appalled.

Although the deeper strategic origins of the American Revolution are subtle, complex, and controversial, there is far less muddle about what happened on July 2, 1776, publicly proclaimed two days later. Adopting a resolution written by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, the Thirteen Colonies stated they had now clarified their goals in the controversy with the British monarchy. For a year before that, the Continental Congress had been corresponding with each other and meeting in Carpenters Hall with the goal of achieving representation in the British parliament -- "No taxation without representation". The model for most of them was based on the Whig agitation for Ireland -- for a local parliament within a larger commonwealth. But the passing of the British Navy in Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then the actual appearance of seven hundred British warships in American waters showed that not only was Parliamentary representation out of the question, but King George III was going to play rough with upstarts. The new goal was no longer just representation, it was independence. If we were going to resist a military occupation at the risk of being hanged as traitors, we might as well do it for something substantial. The meeting had a number of Scotch-Irish Princeton graduates, whose basic loyalty to England had long been divided. Pacifist Pennsylvania, chief among the wavering hold-outs, was mostly won over by its own Benjamin Franklin, who was optimistic the French would help us. Even so, both Robert Morris and John Dickinson refused to sign the Declaration; Franklin persuaded both to abstain by absence, which created a majority of the Pennsylvania delegation in favor. That's a pretty slim majority for a crucial decision. Franklin was soon dispatched back to Paris to make an alliance; Washington was dispatched to hold off that British army in the meantime. Jefferson was designated to write a proclamation, which even after editing is still pretty unreadable beyond the first couple of sentences. Meeting adjourned. This brief account may not qualify as a serious examination of the causes of the American Revolution, but it comes close to the way it seemed to the colonist in the street.

|

| Colonist's Complaint |

The rebels then spent eight years convincing the British they were serious and have been independent ever since. But, just a minute, here. Reflect on the fact that fighting had been going on for a year in Massachusetts, and that Lord Howe's fleet had set sail a month before the Declaration, actually landing on Staten Island at just about the same time as the Fourth of July. Add the fact that only John Hancock actually signed the document on July 4th, and some of the signers even waited until September. You can sort of see why John Adams never got over the idea that Thomas Jefferson had a big nerve implying the whole Revolution was his idea. What's more, there's a viewpoint that New England subsequently had to endure a President from Virginia for thirty-two of the first thirty-six years of the new nation because loud talk from New England still made the rest of the country nervous. Philadelphia may have been the cradle of Independence, but that was not because it was a colony hot for war, dragging others along with it. Rather, it was the largest city in the colonies, centrally located. It had a strong pacifist tradition, and it had the most to lose from a pillaging enemy war machine. When Independence was finally declared the goal, many of Philadelphia's leading citizens moved to Canada.

New England had started hostilities and was about to be subdued by overwhelming force. The Canadians were not going to come to their aid, because they were French, and Catholic, and enough said. What New England and the Scotch-Irish needed were WASP allies, stretching for two thousand miles to the South. By far the largest colony was Virginia, which included what is now Kentucky and West Virginia; it even had some legal claims for vastly larger territory. Virginia was incensed about its powerlessness against British mercantilism, especially the tobacco trade. The rest of the English colonies had plenty of assorted grievances against George III, and almost all of them could see that America was rapidly outgrowing dependency on the British homeland, without a sign that Parliament was ever going to surrender home rule to them. It was perhaps unfortunate New Englanders were so impulsive, but it looked as though a military confrontation with the Crown was inevitably coming. Without support, New England was likely to be torched, as Rome once subdued Carthage.

And the last hope for an alternative of flattery and diplomacy, for guile and subtlety, had stepped off the boat a year earlier. Benjamin Franklin, our fabulous man in London, arrived with the news he had finally had it "up to here" with the British ministry. He was a man who quietly made things happen, carefully selecting his arguments from amongst many he had in mind. In retrospect, we can see that he held the idea of Anglo-Saxon world domination as far back as the Albany Conference of 1745, and could even look forward to America outgrowing England in the 19th Century. His behavior at the Constitutional Convention of 1787 strongly suggests he never completely gave up that long-term dream. Just as Edmund Burke never gave up the idea of Reconciliation with the Colonies, Benjamin Franklin never quite gave up the idea of Reconciliation with England. While John Dickinson and Robert Morris resisted the idea of Independence down to the last moment, Franklin took a much longer view. For the time being, it was necessary to defeat the British, and for that, we needed the help of the French. In 1750, America joined with the British to toss out the French. And then in 1776, we joined the French to toss out the British. Franklin didn't always get his way. But Franklin was always steering the ship.

The Barnes Foundation: Comments on the Economics of Art (2)

In 1951, Albert C. Barnes' legacy included Jerome's Epistle to Paulinus from the Gutenberg Bible education centered on a notable collection of illustrative artworks, housed in a museum of his own general design for the purpose. He left a multi-million dollar endowment to support his rather detailed and, in the opinion of many, somewhat eccentric intentions. It was his money, however, so his word was final. The institution was fairly mature, having previously been in operation under his direct control for twenty-five years.

Since the Foundation trustees are now before the Orphans Court pleading for permission to modify Dr. Barnes' instructions in order to avoid financial collapse, skepticism is inevitable. Obviously, the successor trustees must explain their expenses. But quite a plausible case can be made that the true cause of this disaster is inherent in the huge windfall growth in value of the paintings. In short, growth in value of the fine art may have outstripped the growth of the resources set aside for maintenance.

|

| Johann Gutenberg, creator of mass produced books, died in poverty |

Let's make a benchmark of the Gutenberg Bible, where incomplete copies are currently selling for $100,000 a page and complete copies are estimated to be worth $100 million apiece. Dealers maintain the Gutenberg is increasing in value at 20% a year, but growth seems closer to 9% a year if you go back to 1951. What's really relevant here is the growth in cost to ensure, protect, dehumidify, display and make it available to scholars, if not the public. It seems safe to guess these maintenance costs have grown more rapidly than the investment growth of the endowment, which is surely closer to 4% than 20%. The imbalance is even greater if you remember that some investment income is spent every year, while the worth of the fine art just grows and grows. Regardless of the true numbers, if the cost of maintaining the art does grow even slightly faster than the endowment, the dilemma the Barnes is now facing will eventually face any museum. New sources of revenue, either from the government or from public admissions, eventually becomes necessary if the priceless art remains on display. It is displaying these things that cost money; burying them under an Aztec mound or a German salt mine shelters them from the problem. In the case of Alfred Barnes, it is not completely certain that he wanted them displayed.

There is also the issue of quirky fluctuations in the market for fine art. The 22 known perfect copies of Gutenberg, Bibles have been around for almost five hundred years, and it is safe to say their value is enduring. The 180 paintings by Renoir now owned by the Barnes may prove to be Gutenberg Bibles or they may prove to be a passing fad, but it is pretty hard to believe that one of them will always be worth two Gutenbergs. Since there is a pretty fair chance that we are currently seeing a value bubble in French Impressionist painting, it is questionably prudent to shipwreck the whole Barnes Foundation, the School, or Albert C. Barnes basic intent, by resisting the sale of even one of the more overpriced examples in the collection at the top of the market.

That's one side of it. Another consideration is that Barnes himself did considerable merger negotiation with other museums, and may have been unexpectedly killed in an auto accident before he turned over all his cards in that particular poker game. It's asking a lot of the poor judge to overturn the clear and largely unmistakable language of Barnes will in favor of theories about what Barnes was really really thinking when he wrote it. If the judge is feeling adventurous, it's probably more satisfying to all parties if he sets forth a new legal doctrine, reflecting the inevitable disparity between the cost of displaying fine art to the public, and providing a perpetual endowment to do so.

Philadelphia in 1976: Legionaire's Disease

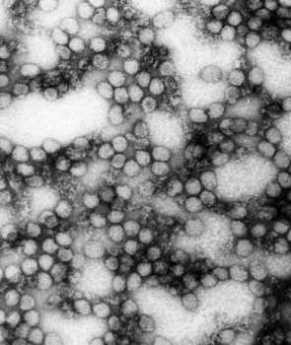

|

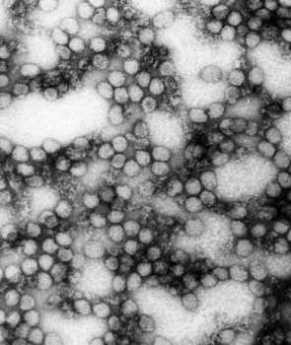

| The Yellow Fever |

No other city in America is remembered for an epidemic; Philadelphia is remembered for two of them. The Yellow Fever epidemic, for one, that finished any Philadelphia's hopes for a re-run as the nation's capital. And Legionnaire's Disease, that ruined the 1976 bicentennial celebration. One is a virus disease spread by mosquitoes, the other a bacterial disease spread by water-cooled air conditioners. Neither epidemic was the worst in the world of its kind, neither disease is particularly characteristic of Philadelphia. Both of them particularly affected groups of people who were guests of the city at the time; French refugees from Haiti and attendees at an American Legion convention.

In 1976, dozens of conventions and national celebrations were scheduled to take place in Philadelphia as part of a hoped-for repeat of the hugely successful centennial of a century earlier. Suddenly, an epidemic of respiratory disease of unknown cause struck 231 people within a short time, and 34 of them died. Every known antibiotic was tried, mostly unsuccessfully, although erythromycin seemed to help somewhat. The victims were predominantly male, members of the American Legion of a certain age, somewhat inclined to drink excessively, and staying in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, one of the last of the grand hotels. Within weeks, it was identified that a new bacterium was evidently the source of the disease, and it was named Legionella pneumophila. Pneumophila means "love of the lungs" just as Philadelphia means "city of brotherly love", but still that foreign name seemed to imply that someone was trying to hang it on us. Eventually, the epidemic went away, but so did all of those out-of-town visitors. The bicentennial was an entertainment flop and a financial disaster.

Since that time, we have learned a little. A blood test was devised, which detected signs of previous Legionella infection. One-third of the residents of Australia who were systematically tested were found to have evidence of previous Legionella infection. A far worse epidemic apparently occurred in the Netherlands, at the flower exhibition. Lots of smaller outbreaks in other cities were eventually recognized and reported. It becomes clear that Legionnaire's disease has been around for a very long time, but because the bacteria are "fastidious", growing poorly on the usual culture media, had been unrecognized. And, although the bacteria were fastidious, they were found in great abundance in the water-cooled air conditioning pipes of the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. Even though the air conditioning was promptly replaced, everybody avoided the hotel and it went bankrupt. When it reopened, 560 rooms had shrunk to 170, and it still struggled. Although there is little question that lots of other water-cooled air conditioning systems were quietly ripped out and replaced, all over the world, the image remains that it was the Bellevue, not its type of plumbing, that was a haunted house. There is even a website devoted to its hauntedness.

War Dance

History Footnote: Before the white man came, the Iroquois "nation"devised rules still characteristic of our modern political parties. At various times, there were five, six, or seven tribes in the Iroquois confederacy headquartered in upstate New York, allied to each other with fluctuating loyalty. Philadelphia's tribe were Delawares or Leni Lenape, but the most warlike and dominant tribe were the Mohawks. Confederations work best when allied against a common foe. The rest of the time, member tribes mostly beat and cheat each other.

The Philadelphia Democratic Party appeals to a number of minority groups and recent immigrants, but it is more meaningful to think in terms of players. For example, university professors are mostly Democrats, but the teachers union is an active political player. Minorities generally vote Democratic, but the Black Ministers are players. Lawyers are rather evenly divided between Republicans and Democrats, but Plaintiff Trial Lawyers, the ones who sue people for a share of the award, are players.

Some people are players but keep it quiet. Certain rich donors are players but don't want to be known as such. The chiropractors and optometrists claim to be players but would rather not have the truth known. The news media and utility companies come close to denying they are players in spite of abundant evidence otherwise.

Well, the local players had a war dance just before the November 2005 elections; the timing was no accident, and it was publicly described as a SEPTA contract negotiation. The issues had mostly been settled in advance, but the real deal-breaker was health benefits, Blue Cross health insurance paid by the employer to escape income tax and to make the pay packet appear smaller to the taxpayers. Step by step for twenty-five years, employers in the form of the Republican politicians had been keeping up a steady drumbeat, trying to reduce the incentive to overspend health insurance because it seemed free, with resulting increase in employer costs. Slowly, business management convinced a majority of the public that "first-dollar coverage" was a villain, since the person covered by the insurance has no skin in the game. Even party loyalists had to admit that it looked as though the tax exemption of health insurance was injuring the image of labor. That concept carried the slogan of "sending jobs to China", or killing the goose that lays golden eggs in the Rust Belt. Five million Health Savings Accounts were sold in 2005 in spite of state laws hampering this form of health insurance, and from experience it seemed certain that five times that many would be sold if early-adopters reported satisfaction. The surrogate was deductibles and employee contribution to health insurance; just about everybody recognizes the need to make some token contribution to health insurance in order to have skin in the game and keep costs down. But not the SEPTA workers. In 2005, the brotherhood of Septa workers would go on strike for fifty days rather than pay one penny of "give-back" for health insurance. Their energy level was high, they were waving their arms, they were ready to overturn ashcans.

|

| Bellevue |

When union contract negotiations go on for days, all day, the public gets an idea the negotiating table is a shouting match the whole time, with "negotiators" carrying on with tom-toms and tomahawks in an even more physical and extreme model for their supporters on the street corners. For about ten minutes a day, that's true. But then the television people can turn off their lights and the war hawks fan out to talk with their supporters outside the room, which in this case happened to be in the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. Perhaps you didn't know the Pennsylvania Governor has quite a nice set of offices there. Perhaps you haven't noticed that all the parking spaces on the side alleys near the Bellevue "belong" to various politicians. Just try parking there yourself to learn a few facts of Philadelphia life.

In negotiating classes, they teach you never to make the first concession. By that reasoning, no negotiation would ever end. The more practical advice is to forget about any serious bargains until the last day of the contract, or even a couple of days after that. The hard reality is that no one will make a concession while there is time for some invisible player to back out; no one wants to give his constituents time to realize he has sold out their trust or violated their loud, insistent, wholly unrealistic demands. And so in 2005, after the shouting had gone on for some time, and even a real strike began, the Governor finally sauntered into his nice Philadelphia office. Time to get to work.

|

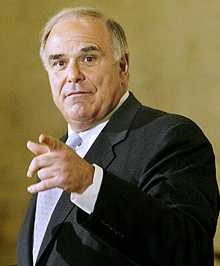

| Ed Rendell |

Those who didn't know him made the comment they could almost believe he was a victim of Attention Deficit Disorder. He talked all the time, moved all the time, and apparently showered all the time. That is, he was in and out of sight all night, but invariably reappeared with fresh shirts, clean shaves, and sharp creases. His aides confided he wasn't very good at "detail work", which is to say he conducted the whole affair on a primeval level of dominance, bluster, charm and implied threat. Don't bother me with facts. Mayor Street, on the other hand, would come in and mumble something incoherent, and then had to leave for an important engagement. Word came in that the school teachers felt they really had to pay a small health insurance deductible, and it wasn't so bad. Foo, no guts.

Somewhere along the line, the newspapers started to echo that deductibles had their merits. Foo, bunch of Communists. The black ministers were reported to feel that if their people all had to pay deductibles, why couldn't the transit workers. Bah, bunch of muddleheads. In the hubbub, someone asked what Andy Stern thought. The trial lawyers didn't have as much to say as they once did; SEPTA had reduced liability costs by $87 million through adamantly refusing to settle any case without going to court. Paper tigers. What about chiropractic benefits, we demand the inclusion of chiropractic benefits. No, said SEPTA, we aren't going to agree to any of that sort of thing. Well, what about twenty visits a year to chiropractors?

One by one, the other players deserted the SEPTA workers. The message from the other tribes in the confederation seemed to be, get what you can for SEPTA, but stop the strike by election day. The Governor produced the razzle-dazzle, a loan to the city to pre-pay the Blue Cross premium, in return for which Blue Cross would reduce the premium. The effect of that was to produce enough cash to appear to add ten cents an hour to the pay packet. We'll have to wait a year to see how this money gets restored to Blue Cross, but that's the general idea.

The strike was over, hurray. The next day, the Democrat party elected Democratic governors in New Jersey and Virginia, defeated some California amendments which would have hurt the trial lawyers and teachers unions. Surely, someone in the Democrat party nationally was telling himself that caving on the Philadelphia transit strike was a small price to pay for that.

Philadelphia in 1876: The Centennial

|

| The Centennial Exhibition |

The Centennial Exhibition could easily claim to be the most transforming event that ever happened to our town. It represented the hundredth year of our independence, although 1887 would be the hundredth anniversary of our nation, and anyway, the Declaration of Independence was just sort of a hook to hang the exhibition on. Opened in the spring with a speech by the Civil War victor, Ulysses S. Grant, it was also closed in the fall with another speech by him. The planning, design, and atmosphere of the whole thing was triumphalism -- the world will never be the same because this country has arrived. The exhibition introduced to an awe-struck world, the electric light bulb, the typewriter, and the telephone. We've won the Civil War, and this is how we won it. It's too bad of course that we had to tousle up the South that way, but look at how great it is going to be to participate in the Colossus of Tomorrow.

|

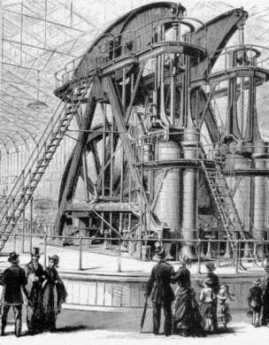

| Corliss Steam Engine. |

The civilized world competed with each other to display their things of pride in national pavilions. And next to them was even bigger pavilions by the States, with even more matters of pride to display. The main exhibition hall covered twenty-one acres. The future was here, and it was machinery. Machinery Hall was filled with thousands of machines of one sort or another, and wonder of wonders, they were all driven by one operator controlling a single huge engine, the Corliss Steam Engine. The Age of Artisans and Craftsmen was over. We had entered the world of Industrialism.

It was intended that the rest of the world should take notice of America, and of course of America's bumper City. Less noticed was that Philadelphia woke up to the rest of the world. Over eight million people attended the exhibition, most of them Americans. A great many Philadelphians spent a whole week poring over the exhibits, and some even spent a whole month doing it. Just as Japan got the jolt of its life when Commodore Peary showed them just how far-out-of-it-all they were, Philadelphia got the same jolt from the European exhibitors at the Centennial. We were showing off, but we were learning.

Sugarloaf

|

| Germantown Map |

Germantown Avenue goes continuously uphill from its start at the Philadelphia waterfront until it reaches Sugarloaf in Chestnut Hill. It follows an old Indian Trail, and that's where the Indians apparently wanted to go. From Sugarloaf northward, it's all downhill.

The name derives from the shape of the hill at that point and is a fanciful description of the sudden shift from Wissahickon gorge to the Whitemarsh Valley, which occurs at that point. The underlying rock changes from hard "gneiss" to limestone. In early times, this was the location of the farm of William D.Stroud, whose son was Teddy Roosevelt's doctor and the first one to introduce the electrocardiogram to this country. Around 1928, James Page built an imposing mansion with a wrap-around porch at the top of the 40-acre estate, naming it Wycliffe. Around twenty years later, the real estate magnate Albert M. Greenfield acquired the property, which eventually was given to Temple University as a conference center, although a fire destroyed the wrap-around building. That's Sugarloaf, and you can visit it.

Two stories about Greenfield, himself, still circulate around town. The first concerns a banker who met Greenfield at the corner of 15th and Walnut Streets.

|

| Albert Greenfield |

The real estate man was looking up at the massive old Drexel building, where Anthony Drexel and J.P.Morgan were partners, and where Edward T. Stotesbury made lots of waves during the 1920s. Stotesbury acquired a personal wealth of about $100 million as "the richest Morgan partner" and was determined to spend every penny of it before he died in 1938. The stories of the extravagance of this birthright Quaker, and particularly his wife, are legendary. Anyway, Stotesbury held court at a big desk, just inside the door at 15th and Walnut. Greenfield was standing outside that door, chatting with his banker friend.

"Do you remember that big desk where Stotesbury used to sit?" Yes. "Well, I used to sell newspapers at the corner here and watched Stotesbury go in and out. I want you to know I just bought that building, myself, and I'm going to put my desk right where Stotesbury used to sit."

Unfortunately, he never did. Within two months, he was dead of pancreatic cancer.

The other story was told of Greenfield's integrity, the sort of thing that was central to the long-standing success of Philadelphia businessmen in commerce and banking. When bargains are stuck in a conversation, the deal is sealed with a handshake, and you better be as good as your word.

Hubert Horan, the Chairman of the Broad Street Trust, was interested in a piece of property, and over lunch agreed to pay Greenfield three million dollars for it. Before any papers were signed, another man came rushing into Greenfield's office and excitedly announced he wanted to buy the property. "I'm sorry," said Greenfield, "I just sold it to Hubert Horan". How much? "He agreed to pay three million for it." Did you sign anything? "No." Fine, I'm willing to pay you FOUR million for it."

"Well," said Greenfield, "I suggest you go see Hubert Horan. He owns it."

Musical Fund Hall

|

| William Strickland |

At the corner of 808 Locust stands a condominium building with a colorful history. It was originally the First Presbyterian Church, and then in 1820 the famous architect William Strickland converted it into the largest musical auditorium in the City. For several years, a group of music lovers had been meeting to discuss the problem of aging and retired musicians, most of them impoverished. The idea arose of giving several benefit performances each year to raise money for retired musicians, and the idea was enlarged to create a Musical Fund Society to put on regular concert series. Since it was by far the largest public auditorium, it also served for graduations, speeches, conventions.

|

| John C. Fremont |

It thus came about that in 1856 the Republican Party held its first national convention there, nominating for President John C. Fremont, the famous explorer of the West. The Republicans had two main components, the advocates of the abolition of slavery, and the residual of the Whig Party, which had come apart. The Whigs were mainly concerned with using government effort to promote the economy, building canals and roads, and similar ideas for public benefit. Abraham Lincoln had been a fervent Whig.

|

| Musical Fund Hall |

As a musical society, the Musical Fund was quite instrumental in persuading this Quaker City that music could be used for purposes other than religious incantations and frivolous entertainments. And it was useful in bringing the new instruments and musical concepts from Europe to the New World. Louis Madeira has written an interesting history of the early musical significance of the Musical Fund. When the Academy of Music opened in 1856, the old hall on Locust Street became a relic of the past. It had assets, however, and the organization continues to function as a granting agency for musical production and development in the Philadelphia area, even though it is itself no longer in the business of musical production.

And then the third strain of history in this old place is the development of Musical Unions. This is natural enough, in view of the original purpose of helping indigent musicians. But unfortunately, several competing unions appeared, most of them on Locust Street and the dissention was bitter and continuing. In 1871 Philadelphia was the scene of the creation of the National Musical Association, and although the local 77 became a part of the national movement, it was stormy. Competitive musical unions had a history of calling the police to shut down speakeasies run as private clubs by their competitors. During the Depression of the 1930's there were many accusations of Communist infiltration, and counter accusations that Joseph Petrillo, the national president, was a Nazi. An underlying theme among musicians was that foreign immigrants were willing to work for less than the standard wage, and hence many of the coercive features of the union were aimed at forcing immigrant musicians to become members and to refuse to work for substandard pay.

Some idea of the bitterness in the situation can be gained from the strike against the Philadelphia Orchestra in 1956. Ten years later, only one member of the union in ten was employed.

REFERENCES

| Music in Philadelphia: and the Musical Fund Society, Louis C. Madeira ISBN: 1-932109-44-7 | Ross and Perry Inc. |

| Musical Notes of a Physican: F. William Sunderman Sr. ISBN 0963292706 | Alibris |

Mummer's Strut

|

| Mummers |

For over a century, and maybe for two centuries, the Mummers Parade has strutted around Philadelphia on New Year's day. The Mummers have lots of tradition and oral history, but the authenticity of records going back to the early days of the parade do not meet very strict standards. There are those who say that the earliest mummers were "shooters" who coursed through town on the Fourth of July, shooting pistols in the air with one hand and carrying a bottle of booze in the other. Booze, by the way, was the name of a bottle manufacturer which became associated in common parlance around 1840 with the product most commonly found in the bottle. The name booze bottle was attached to a bottle in the shape of a log cabin, suggesting a possible link to the 1840 Presidential election of William Henry Harrison, Old Tippecanoe. The other historical origin was thought to be the annual parade of the guilds, the butchers, carpenters and similar. Somehow, these two traditions came together in the annual parade on New Year's day, with various ethnic clubs spending all year getting ready to compete with each other for attention. Many of the floats are reminiscent of the New Orleans Mardi Gras parade, some cubs specialize as "comics" in the style of the old shooters dressed up as clowns. The increasingly dominant part of the parade is found in the ten or twelve String Bands.

|

| Marilyn Monroe Effect |

The main instruments of the String band are the banjo, with the tune carried by some saxophones and a peculiar instrument that looks like a xylophone held up on a pole. emitting an octave of piercing chimes.The old favorites are "Dem Golden Slippers" "Wait 'till the Sun Shines Nellie" and similar fast marches. The costumes tend toward ostrich feathers and gaudy colors, and in recent years the string bands all put on a little show or dance in front of the judging stands. Since it takes place in January, it is usually quite cold at a Mummer's parade, and since the parade goes along streets lined with tall buildings, the wind builds up quite a"Marilyn Monroe Effect". Until recent years, the mummers have always been male.

The mandatory traditional food at a mummers parade is a Philadelphia soft pretzel, smeared with mustard, sold by street vendors. Hot dogs, American flags, and soft drinks are for sale, as well, and other beverages are provided by the onlookers themselves. The parade itself is only an annual public display for the mummer's clubs that have traditionally met weekly in the ethnic neighborhoods, arguing hotly about next year's costume (a deep secret until the day itself), drinking, dancing and sewing the costumes, rehearsing the tunes and the dance steps. There is a traditional "Mummer's Strut, in which the participants and many onlookers participate spontaneously. In its fullest expression, the mummer will hold an umbrella in one hand while holding forward the lapels of his jacket with the other hand, bending forward at the waist, throwing back the head, and more or less keeping time with the music., and shaking the umbrella at the cheering crowd. There's a museum devoted to this sport, located on Second Street, otherwise known as "Two Street". It's all lots of fun, but it is usually too blamed cold to stay there long, and most people eventually retreat to a nearby television to watch the rest of it In the days when the parade went up Broad Street, it passed the Union League where another New Year's tradition was in progress, with the Republican members eating terrapin and drinking Fish House punch, quite comfortable in their warm quarters looking out of bay windows. Democratic Mayor Rizzo used to march in the parade, and when he passed the League, would ostentatiously turn his head away from it. Subsequent Democratic mayors have been even more polarized; the parade now goes up Market Street.

Philadelphia Gardens

|

| Ernesta Drinker Ballard |

There are many show gardens, mainly on former large estates, scattered around the United States, and the ones on Southern plantations are quite famous.

However, the fact of gardening is that the climate has a lot to do with success. The really premier gardens of America are found in an East Coast strip from northern Virginia to southern Connecticut, with Philadelphia in the center of things. There is also a good-gardening area from Oregon to British Columbia, with a particularly notable garden in Vancouver, named after a sort of Philadelphian named Inazo Nitobe whose story is related in another blog. To have a really notable variation of exotic display plants, you need a lot of rain, a long cool spring, and a tradition of cultural association with the British Isles. Alkaline soils, generated by limestone, will produce a fine lilac display. Denmark would be a good place to go see that, but most of the show gardens in America are based on acid soils, with dogwood and azalea the predominant background coloration in May and June. A visitor from Michigan was once heard to ask what all the pink bushes were around Philadelphia, so it's likely the soil is not acid in Michigan. On the other hand, Korea is where wild azaleas originally came from, making the acid-soil hills crimson in the spring there. It should be noted in passing that Japan, Korea, and the Delaware Bay are on the same 40-degree latitude, but Japan escaped the loss of species caused by glaciers of the ice age.

Many of the Philadelphia suburbs have thousands of azalea bushes in each town, and hundreds if not thousands of pink and white dogwood, or purple Empress Trees, or magnolias. When you have a lot of those as background to start with, you are ready to begin planting a show garden. For that, we can largely thank John Bartram the botanist, one of the earliest Philadelphia settlers. The grounds of Friends Hospital are particularly notable for azalea display, and the Pennsylvania Hospital is pretty good, too. Although they are closer to Wilmington, the two most famous show gardens in the Philadelphia area are on DuPont properties, Winterthur, and

|

| Longwood Gardens |

Longwood Gardens, They feed you pretty well in the associated restaurants there, and the bookstores and gift shops are truly outstanding. But what in many ways is the best show garden in Philadelphia is Chanticleer, the former estate of a family that founded what is now Merck Pharmaceuticals, located in the suburb of Wayne, across the street from where Tracy Lord, the heroine of The Philadelphia Story, lived on two square miles of the Main Line.

|

| Philadelphia Flower Show |

It's not clear why Chanticleer is such a well-kept secret, but it's sure worth the trip to see it at almost any season, May preferred. Interest in gardening is not limited to just a few big estates, it's a Philadelphia sport. Therefore it's not surprising to learn that the largest flower show in America is held in Philadelphia at Convention Hall in the Spring. If your feet aren't flat when you go in, they will surely be flat when you come out because a complete tour would be miles long, threading among the aisles. It's not easy to guess how much money each exhibitor spends on a display, but it's surely not a cheap hobby when you get to this level. If you notice the landscaping on public grounds in the city, it's always a fair guess that it was paid for by the profits generated by The Flower Show. Almost everybody has heard of the Burpee Seed Company, and Mr. Burpee summed up the prevailing attitude of Philadelphia gardeners: "If you want to be happy for a day -- get drunk. If you want to be happy for a week -- get married. But if you want to be happy for a lifetime -- get a garden."

REFERENCES

| Gardens of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley William Klein Jr. ISBN-10: 1566393132 | Amazon |

No Laborer Left Behind

|

| Ivy League |

The top thirty American colleges have ten times the applicants they have room for. Demand vastly exceeds supply, prices are essentially fixed; shortages result. Can-do is the American way, so our first reaction is to build a lot more colleges and beat them over the head if they aren't first-rate. To bring this down to a local scale, implications are that Philadelphia has a moral duty to build eighteen more Ivy-League universities.

|

| Cosa Ricians Roofers |

Let's think about that, in a back-of-the envelope way. Since the rest of the country is going to be similarly driven, we can't attract Americans to run those universities. Philadelphians who are doing other things must staff those universities; people inclined to become professionals of a different sort are going to have to be trained to be university professors. Students now being rejected will be admitted, since that's the purpose of the thing. Unless we somehow increase academic productivity, every man, woman and child from Trenton to Wilmington is going to be in a college classroom in some capacity or other. We here confront the extrapolation fallacy; a new problem must be addressed in more productive ways than just more of the same.

Curiously, the readjustments to this overall shift from an industrial to a service economy are first making their appearance in things like roof repairs and ironing shirts. When my house needed a new roof, I found I had a choice of workgangs composed of Costa Rican, Puerto Rican, or Polish roofers. The Costa Ricans made the best bid and went to work immediately. They started pounding on my roof at 6 AM, and we're still pounding after I went to bed at night; I have grave doubts that American roofers would approach that work standard. I am told that the entire building industry, on which our current prosperity rests, would collapse if we banned illegal immigration. In a different industry, Philadelphia's convention hall cannot attract visitors unless we build more hotels. But the hotel industry cannot find nearly enough people who speak English to make the beds. For one purpose or another, we have imported 12 million illegal immigrants who mostly remain invisible because they are so hard at work.

We are going too recklessly fast with what is fundamentally a useful transformation of our society. Americans want to go to college because statistics show that will make them prosper. But that's only half of their transformation. The other half is a resulting shortage of labor in the jobs which do not require college. Normally, you would expect wages to rise, but they are suppressed -- deflated -- by substituting immigrant labor, legal and illegal. Impose an effective barrier to immigrants, and you would quickly see inflation like you wouldn't believe. Combat inflation by raising interest rates and the housing market would quickly collapse. That would prove to be a painful way to make the immigrants decide to go back home, although it would be effective. And so on, and so on, and so on.

Slow down, America. You're going in the right direction, but exceeding the speed limit.

National Business Coalition on Health

|

| NCOH |

In 1992 the National Business Coalition for Health was just forming at a convention in Chicago. Before I really understood what it was all about, I agreed to their flattering invitation to be the keynote speaker at the kick-off luncheon. Who suggested my name was and is a mystery to me, and I arrived in Chicago with very little idea what they wanted to hear. However, it followed the familiar pattern of inviting the speakers to stay overnight at the hotel on the evening before the meeting began and to meet for drinks at the bar with the organizing leaders. I had enough experience with public speaking to know I could learn the general slant of the thing at such an informal party and adjust the speech to the audience to whatever degree seemed needed. Among the people scattered around at tables was Harry Schwartz, who was also there to give them a speech. Harry had been on the editorial board of the New York Times for many years and was known to be generally quite favorable to physicians. We had both written books about medical care, The Hospital That Ate Chicago in my case, and The Case for American Medicine, in his. We liked each other immediately and fell into an animated cocktail conversation that would eventually be renewed every six months at the American Medical Association House of Delegates meetings, where I was a delegate and he covered the topic for various news media. As we chuckled together about one anecdote or another of medical politics, the bar gradually emptied out. It soon became clear that all the other cronies had wandered off to dinner together, so we ordered dinner on the house, neither one of us have learned just what we were there to talk about. It really didn't bother either one of us very much, since from long experience we could tell some jokes and make it up as we went along. I knew what I wanted to tell businessmen, so it was just a matter of finding a way to lead into it.

The speech seemed to go well. There were several hundred, perhaps even a thousand in attendance, quite convivial and prosperous. As executives usually do, they looked younger than you might expect from the titles on their name tags; they laughed at the appropriate points and applauded at the end. In other words, I went home from Chicago with no more idea what this organization was up to than I had before I came. At the very least, it is clear they were forming a national organization of businesses, with constituent representatives largely drawn from Departments of Human Resources. They wanted to speak for American Business with a more or less unified voice, and the topic seemed to be health care. Although fate had put me into the debate at the very earliest moment at Wills Eye Hospital, this convocation of extroverted Republicans seemed to know a lot more than I did about what was secretly afoot among the Democrats in Washington.

This Chicago tea party did one other thing for me. Many months later, when the editors of USAToday were in search of an editorial page writer who was both a physician and opposed to the Clinton Health Proposal, they called Harry Schwartz. And he suggested to me. They ultimately ended up with a Medical Editorial Advisory Board of five members, at least three of whom were far to the left of me. At the New York Times, of course, Harry Schwartz was considerably more outnumbered than I was. After it was over, Harry and I used to joke that both sides were fairly evenly matched.

Trapped in a Casino

Everyone who reads a detective novel or sees a James Bond movie is familiar with secret passages and hidden protection devices that suddenly trap the unwary. You aren't supposed to know about these things, but in real life, lots of people have had to know the secret, because it takes builders, architects and workmen to create it. Ancient Chinese and Egyptian emperors may have buried workmen alive to preserve the secret of secret passages, but nowadays that sort of thing is discouraged.

|

| Gambling |

Since nowadays gambling casinos are bought and sold like a bottle of milk, some of the people who just have to be told the secrets of casinos are real estate appraisers; from one of them, the following tidbit derives. Casinos try not to have any windows, so the serious slot machine players won't notice the passage of time, and maybe gamble all night when so inclined. It is, therefore, no surprise the ceilings and walls are usually mirrored, to make these windowless caverns seem gay and cheerful. The casino operator doesn't want anyone to go home for any reason other than running out of money, and depends heavily on the wisdom of Adam Smith, who once said, "The more you gamble, the more certain you are to lose."

|

| Adam Smith |

Unfortunately, these palaces of pleasure attract a fair number of cheaters, who attempt to win by memorizing the cards that have been played and changing their bets with the changing odds of what remains unplayed in the deck ("card counters"). Others are more mechanically talented and drill holes into the works of slot machines with battery-driven portable drills, for later accomplices to insert metal rods into vital wheels and whatnot on the inside. And so on. So, the mirrors on the ceiling are one-way mirrors, with people observing what goes on below, and cameras recording every action of everybody. In this modern age, some casinos can bring up videos of what happened on a particular machine at a given time, several years ago. This elaborate recorded surveillance can be used to unravel the activities of visiting crooks, who quite often do their work over a period of some time, coming back to the same machine for another step in their fiendish schemes. Now, there's another consideration at play here. The casino operator does not want a commotion on the gambling floor when some crook is accosted, because that tends to divert dozens of gambling addicts from their incessant gambling in order to watch the excitement. This would definitely be a violation of Adam Smith's law of gambling, and hence would subtract from the value of stopping the crook who was caught. No good.

|

| Casino Video Surveillance |

So, the merry men up above on the other side of the mirrored ceiling will merely watch and record the activity of the miscreant below, apparently letting him get away with it. But sooner or later the crook has stolen enough or has to go the bathroom, or for some other reason leaves the casino floor. Bang, the door behind him closes and locks, and the door on the other side of the trap is also locked. Thus, without any fuss or muss (maybe) the crook is observed by witnesses, recorded on camera, and tucked away in a security chamber until such time as the security guards can arrive to advise him of the management's disapproval of his behavior. Just exactly what does happen when one of these people is caught is not something they need to tell a real estate appraiser, so, unfortunately, I have to leave it to your imagination.

New Museum of Chemical Heritage

|

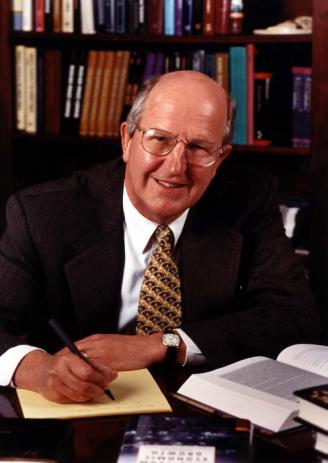

| Arnold Thackray |

Eighty percent of the ethical drug industry is located within a hundred miles of Philadelphia, and the whole chemical industry has had its center here for two centuries. The chemical industry is the region's largest manufacturer, now that locomotives and beer brewing have come and gone, but its profile remains low. In fact, chemists personally have a low profile too and harbor a smoldering annoyance about it. No one has been more determined to change that nerdy image than Arnold Thackray, the recently retired President of the Chemical Heritage Foundation. He's not only a big idea man but bubbles with energy and persuasiveness. That largely accounts for the fact that CHF has the second largest endowment among public institutions in Philadelphia, the best library of chemical history in the world, and a growing reputation for fine art concentrated in the field. That's not enough for him, so it came about that a new museum was envisioned, funded and created. But not built; building it was assigned to Miriam Schaefer, a famous go-getter who had the unusual qualification of being squeamish about chemistry. It was her assigned task to find a way to make chemistry exciting to people who were not instinctively excited by it, just exactly because she was the world's authority on that point of view. What was vital was that she was the sort of person who can't resist a challenge, and was capable of thinking, well, big.

With the unlimited backing of Arnold and his board and their almost unlimited financial support, Miriam set about soliciting big ideas from uninhibited people all over the world, and some of their suggestions were even a little too wild to be acceptable. But since the whole idea was to awaken the enthusiasm of anybody, however sullen, who happens to shuffle through the museum, many outlandish suggestions were forced through the filter of a skeptical, conservative, Philadelphia establishment. The result is a series of pleasant surprises, ranging from fine art with a focus on alchemists trying to make gold out of lead, to astonishing computerized graphic displays of the elements of the periodic table fifty feet high, to depictions of Joseph Priestly known as the father of chemistry, a personal friend of Benjamin Franklin, the founder of the Unitarian Church, and a resident of Philadelphia. There's Arnold Beckman's original Beckman spectrophotometer which made hundreds of millions of dollars, was a major factor in the Twentieth century blossoming of biochemistry, and is here shown to be a clever elaboration of a simple idea. Meanwhile, the museum is housed in a massive old bank building, with it is interior reamed out and replaced with as much transparent glass as could support the weight. Inga Saffron the architectural critic, more than foamed over with praise in her review of just the structure itself. Don't neglect to notice the stunning portrait of Gay-Lussac, the man who discovered that water is H2O. The pigments of his portrait were mixed with beeswax, and with clever lighting have an astonishing luminosity.